CARING FOR CATS DURING THE TWO WORLD WARS

It's fairly well known that several cats "served" during the World Wars. On ships, they protected the valuable food stores from rodents as well as being ship's mascots and welcome companions to the crewmen. Many shore-based establishments also adopted stray cats. One of the Women's Royal Naval Service depots had a black-and-white tuxedo pattern cat named WREN Figaro who was reportedly an excellent mouser, and who conveniently preferred dried milk to the real thing. WREN Figaro was good for morale at the depot. Cats could also be found at airbases and other army establishments where they were welcome ratters and improved moral among servicemen and women.

Rather than look at the cats that "served," this article is primarily concerned with "civilian cats" during the World Wars.

THE FIRST WORLD WAR

I can find relatively little about the fate of pets during the First World War. For many Britons, this war seemed a faraway thing fought in mainland Europe. A major concern to cat owners would have been the feeding of their pets at a time when the usual supplies could not be obtained.

In the early 1900s, cat care books advised breeders and owner to trap sparrows on limed sticks as a tonic for their cats or to make a change from mutton and horse. The horse hadn't yet been supplanted by motorcars. Although the better horses had been commandeered for cavalry mounts; horsemeat from knackers' yards was still to be had. Apart from that, most pet cats were expected to eat scraps and prey they caught for themselves. Breeders of pedigree cats formulated special diets for their cats, but they did not properly understand that cats were obligate carnivores, and fed their cats on meals such as bread soaked in meat gravy. Even before the Great War, breeders were looking for cheap ways to feed their cats due to the cost of meat; for example lentils in meat gravy was one suggestion. All but the most pampered or high-bred cats went into the Great War with few expectations.

Excerpts from the Weekly Dispatch (1917 editions are digitised and available online) and many other newspapers speak of cats during the Great War. Some of the correspondence, although it relates to pet dogs, illustrates the general sentiment that feeding scraps to household pets was equivalent to taking food from children.

Northern Whig, 18th January 1917: SOLDIERS' PETS

Perhaps no soldier in the whole wide world is fonder of pets than the British Tommy. The Frenchman is devoted to his dog, but that dog must be of some material use and justify his keep. The Cossack and the Arab are passionately attached to their own horses, but their lives frequently depend upon the sagacity and swiftness of their steeds, therefore the horse is absolutely essential to their existence. With the British soldier, however, the utility of his pet is the last thing to be considered. The more hopelessly useless the creature seems from an outsider s point view the more valuable it appears in his eyes. He has always soft corner his heart for the halt, the blind, and the maimed, and for this reason his taste in pets is extremely wide; anything and everything that is capable of being petted becomes a valued companion. . . . Cats are also numerous and have either been rescued from a ruined house or else sought shelter with the soldier in the trenches. The kittens born in the trenches lead a pampered existence and have a princely time. All the cats show a fine disregard of danger. They sit and clean themselves on the parapet or sun themselves on a sandbag, utterly unheeding the splutter and noise of shells. If, however, a bullet or piece of shrapnel ploughs the mud or sand near at hand and pussy gets her share of dust and dirt she will retreat in a fine rage into the trench. But at all time she hunts contentedly enough in that dread place, No Man s Land, intent on capturing mice and birds. At other times she will visit the cat next door, and two Toms will have a battle royal, with much swearing and fur-pulling, in full view of both lines. Even Tim, the terrier pet the E---s, has been known to be routed in a stand-up fight with Jenny, the cat belonging to the D- - - s, the said fight taking place on a sandy patch not a thousand yards from the German lines.Weekly Dispatch, April 15th, 1917: Should we Destroy Useless Pets and Derelicts?

"We are asked to eat less meat, less bread, less potatoes [...] I am glad the Government are taking steps to stop the amount of food consumed by dogs. This ought to have been done months ago. I have been astonished to see the absolute maste of food given to dogs - odd potatoes (when they were plentiful), greens, pieces of bread, bones, fat, etc - quite enough to keep a child." PRO BONO PUBLICO

"In London alone there are no fewer than a million of useless and pampered dogs, whose removal would be a public blessing." OBSERVER

However, other pet owners believed if a person wanted to share their own ration with a pet, it was no business of the Government as they were depriving no-one but themselves.

Weekly Dispatch, May 13th, 1917. Helen Mathers was writing about dogs (reported by Marian Ryan), but the sentiment was true for many cat owners.

"The suggestion that we should kill these friends and companions instead of sharing our food with them till the last gasp [...] why, anyone who has a dog friend would share the last piece of meat, the last biscuit with him. Not depriving anyone else, you know, just giving up half of one's own rations. [...] I am only surprised that more people have not protested violently against the idea that they should give up their dogs when they could sacrifice a little of their own food instead. [...] We are an animal-loving race ... we are not going to kill our friends."

Weekly Dispatch, May 6th 1917: Questions Every Woman is Asking, Answered by Lady Quill.

Lady Quill answered home economics questions, such as how to cope without household items that were previous considered essential. This affected pampered cats whose owners normally provided meals made with boiled fish heads, meat scraps or milk.

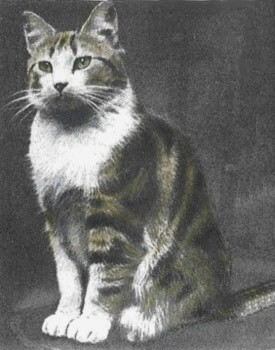

"New food trials press upon us. The bread tickets will be issued shortly, the afternoon tea necessities may be banned by law if we do not voluntarily resign the, and, worst of all, oour faithful dog and cat companions must be sacrificed to the common good. This is the saddest news to many of us. I know some women who are literally sharing their own food with their dogs or cats. 'We have no scraps in our household,' said a Frenchwoam yesterday, 'so Fidele and Mimi really share our rations, and we shall continue doing this rather than part with them.' It is the pampered pets who may have to go. The dogs for whom choice tit-bits are bought; the cat, like a sleek tabby I saw recently, who must have three cods' heads a week and cat's meat and milk as well!"

The Cats Protection League's magazine "The Cat" carried meal suggestions to keep pet cats going during the war years. One member recommended bread soaked in milk with a gravy of yeast extract. The excess milk was poured off and then mixed a small quantity of yeast extract (e.g. Marmite) in water, and sprinkled a teaspoon or two of this "gravy" over the milk-soaked bread. The magazine's editor recommended making a good solid pudding as a substitute for meat. The pudding should comprise table scraps such as bread, potatoes, vegetables and cheese, all moistened with Marmite gravy, mashed together and baked in a pie-dish for about an hour. When cold, this set into a firm slab and could be sliced and cubed to provide several days' food.

Some of breeders of pedigree varieties had emigrated to the United States with their cats and set up a cat fancy there. Cats were exchanged between Britain and the USA, but then the World War put an end to this. A number of influential (and affluent i.e. army officer class) male cat fanciers, including breeders, show organisers and judges, were lost due to the war. Several regional clubs or breed clubs had to re-establish themselves after the death or incapacitation of stalwart supporters. Breeding stock also might have to be dispersed to other breeders. At that time there were relatively few recognised breeds in Britain; the main breeds were (British) Shorthairs, (Persian) Longhairs, Manx, Russian Blue, Siamese, Abyssinian, all in a limited range of colours. Many good breeding cats had been exported to the USA at the turn of the century so British lines could be restored by importing the descendent of those exports.

Weekly Dispatch; Date: Jun 24, 1917: Terrible Times for Dogs and Cats; Effects of Air Raids and Thunderstorms.

"The combined effect of the recent air raids and thunderstorms has had a demoralising effect on dogs and cats" writes a dog fancier, "The animals are much more 'nervy' even than human beings. ... I have noticed that during an air raid dogs howl piteously, while cats seek the darkest corner they can ... I believe these animals 'sense' the coming danger."

Weekly Dispatch, September 9th, 1917: Cats "lie Doggo" (The "Specials" and the Raid; How London was Bombed and What the Unpaid Policemen Did, by A Superintendent.)

Strange noises met the ear. The guns boomed at fitful intervals and in side street dogs were shrilly barking, apprehensive of a danger that, though hidden from view, could be felt. Cats somehow are different. They vanish as if by magic, and never once on duty in an air raid have I heard a cat meowing or seen a cat straying in the streets. Whoever the Chief Commissioner of Felines is, his orders are to take cover when the warning guns are heard are faithfully obeyed by the cat community.

Weekly Dispatch, October 21st, 1917: London's Starving Cats; Hundreds Abandoned by Thoughtless Air-Raid Refugees

"Among the greatest sufferers from air raids have been London's cats. Since the last series of raids, cats' homes have become uncomfortably over-crowded. Many families in their flight from the danger zone have had little though for anyone but themselves, and hundreds of pets have in consequence been left to fend for themselves - a difficult matter in cities in these times of food shortage. Many of the animals are half-starved, and many suffering from diseases due to that and exposure. The attendant of one home told a Weekly Dispatch representative that during the last six weeks more diseased stray cats have been admitted than at any other time since the war. These animals, being a danger to the community, are destroyed at once to prevent contagion."

The British government drafted five hundred cats and sent them to the trenches to be used as barometers to give warning of the approach of gas. Such is the sensibility of cats to all poisonous odours that gas overcame them before human noses detected it. It was not a pleasant job for the five hundred, and it seems that some of them should have returned to receive decorations or some special honour; but perhaps the poor things all perished or strayed. The army records do not reveal their fate.

On November 20, 1919, The [London] Times reported that Lady Decies (once a renowned cat breeder) was fined for giving rice to her dogs. As part of the war effort, food fit for human consumption wasn t allowed to be fed to animals. At Ascot Police Court yesterday, Gertrude Lady Decies was charge under the Cereals Order with using rice as food for dogs. She was ordered to pay a fine of 2 and costs. Police-inspector Simmonds said that on October 8 he went to Scotswood, Sunningdale, and he saw two dogs in a kennel eating rice pudding from a plate. A person standing near was holding a tray on which there were seven other plates of rice pudding. He did not see Gertrude Lady Decies at that time, but a few days later, when he called again, her ladyship told him that as soon as she knew it was wrong she stopped feeding the dogs with rice. She also said that a mistake had been made, as she had ordered chicken rice for the dogs, but best rice had been forwarded instead. It was also stated that Gertrude Lady Decies kept 14 dogs. In defence it was submitted that the defendant was ignorant of the Order. Lady Decies was, at the time, an impoverished widow who had served in war hospitals overseas, been wounded by shrapnel, and may indeed have been ignorant of the order.

After the end of the Great War, the Rhineland was occupied by Allied forces until 1930. Reports in the Londonderry Sentinel (19th September 1929) among other British papers described the provisions being made for the pets being brought back from the Rhineland by soldiers.

SIX MONTHS' QUARANTINE. Great preparations are being made at the Dogs and Cats' Home at Hackbridge,, Surrey, run by the R.S.P.C.A., for the reception of 300 of the pets which the Rhineland Army is expected to bring home with it. All the animals will have to remain in quarantine for six months as a precaution against rabies and other infectious diseases. They are to be maintained at the expense of the army, with a nominal charge to their owners of 2 a head. Head-Keeper Brown showed me proudly over what is really a wonderful establishment, occupying nearly fourteen acres of ground, approached by a drive that might belong to a country gentleman's estate. He has been here twenty years. "The dogs will soon settle down and be happy," he prophesied. Cats are more difficult to manage, and many of the soldiers will be bringing cats. Cats do not seem to miss their human friends, but are apt to worry and brood when shut up in a strange place, even when the place is what Mr. Brown calls "the best cattery the world." The kennels, or rather cubicles, measuring 8ft 6in by 4ft 6in., are being specially enclosed in one-inch wire mesh, so that no animal can come in contact with another. Each cat's kennel has an open-air section attached, and there are fifty separate exercise grounds for the dogs. There is also a bathroom, with hot and cold water laid on. It will take fifteen stones of meat principally beef per week to make the soup in which the Rhineland Army's dogs will have their broken biscuit soaked. Stewed meat and soaked biscuit will be mixed together in the proportion of one part meat to three of biscuit. The cats will get milk and fish. The first batch of pets is expected at Hackbridge next Monday. Officers of the R.S.P.C.A. will meet them at Dover, and see that they are placed in crates of suitable size from "Pom" to Alsatian. They will then travel by road. Transport and board and lodgings for six months will cost on an average £12 for each dog or cat."

AMERICAN ALLEY CATS WANTED IN TRENCHES. "Salvation Nell" Is First Rat Catcher to Sail for Europe. The Daily Ardmoreite, Ardmore, Oklahoma, 30th Jan 30, 1918, pg 6

Kansas City, Mo., Jan. 30. – "Salvation Nell," a black, short-haired cat and the best rat catcher in the vicinity of Mt. Washington, a suburb, was the first member of the feline "legion of death" being enlisted for service with the American army in France, at the annual cat show here. Female cats are more in demand for this work than males, as, according to experts, females are the best mousers because nature compels them to care for many and quickens their energy in search of food. Therefore, the fact that tabby has many dependents is all the more reason why she should be drafted. The rat menace on the western front is said to be serious and the allied governments are after all the cats they can get to combat the pests. Accustomed to flying projectiles, mud and water, the low "alley" type of cat is said to be much preferable to their more fashionable cousins, the Persian, or long-haired type. Shell shock has no horrors for the alley cat and night hours are its regular habit.

CATS THAT COST A FORTUNE. WHILE FIGHTING CATS ARE BEING CALLED TO THE WAR FRONT, PAMPERED CHAMPIONS ARE WINNING RIBBONS AND LIVING IN LUXURY BY Ethel Thurston, The Daily Ardmoreite, Oklahoma, 16th June 1918, pg 14.

You may not like cats. You may openly dislike them. But it is interesting to know that the cat is still a very popular animal, and that the fact of your dislike, should you happen to have it, does not prevent certain cats from being prized so highly that their value is translated into terms of little fortunes. In fact, there are cats and cats. For instance, thousands of cats are helping to win the war for the allies. A British official recently in this country was looking for "samples" of aggressive waterfront cats such as might be enlisted for the cat army that is working in Europe for the extermination of trench rats. There is a big job for the cat at the fighting front and thousands of them are needed. Every once in a while the cat shares honors with the dog in performing some act of supreme indifference to danger.

"All kinds of methods of exterminating the trench rats have been tried in vain," says a recent writer. "Poison seems to be as inefficacious as dogs. Moreover, the latter, if good ratters, which is not always the case, will kill their prey, but not always eat them, and require to be fed, which means additional trouble and expense for the commissariat and quartermaster’s department." French cats, it seems, have failed in this work. Having heard stories of the size and ferocity of the wharf cats of Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, Galveston and New Orleans, the British and French authorities are seeking these American recruits. Only those who have been in the trenches know how important a matter the trench rat problem is, but every well wisher of the allied cause will hope that the American cat may meet the test and may have a real chance to do his bit.

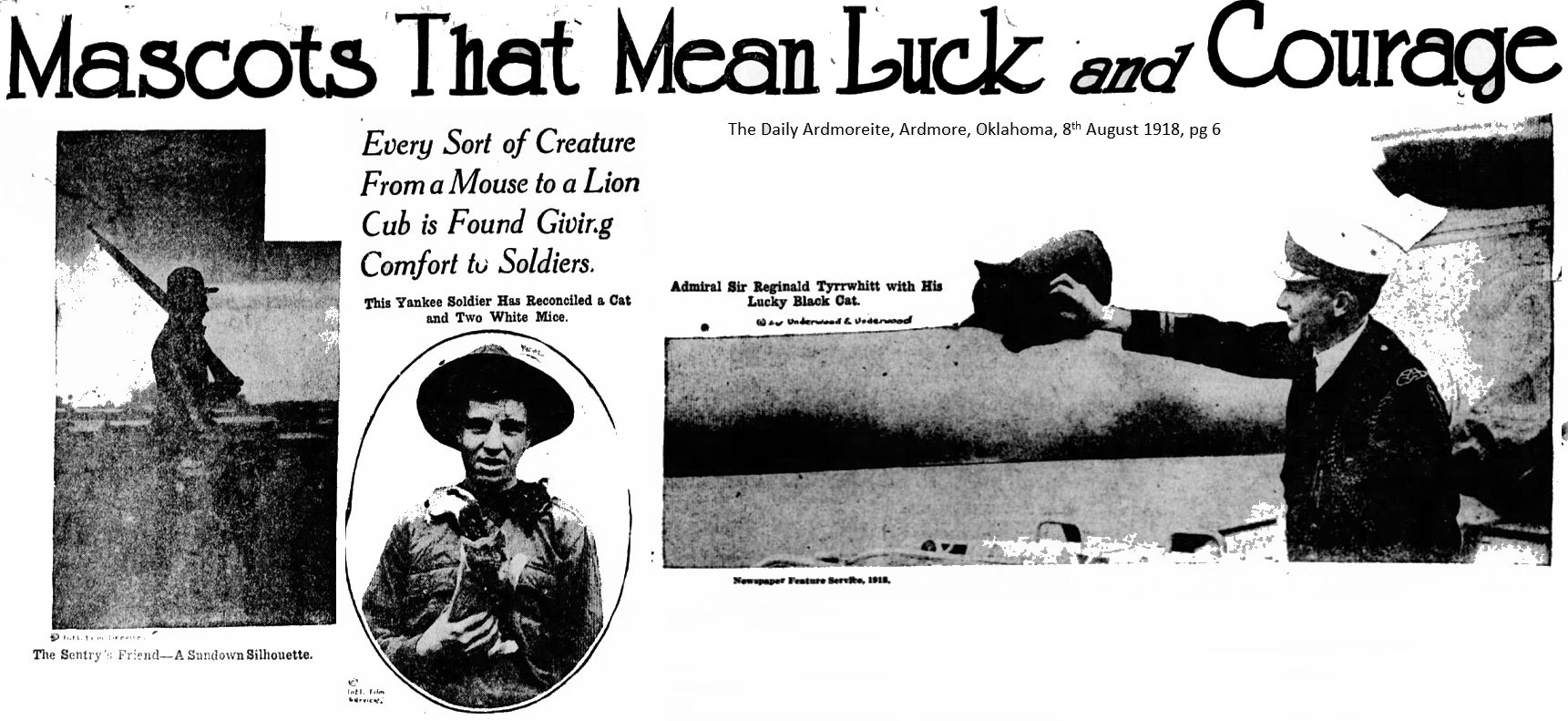

MASCOTS THAT MEAN LUCK AND COURAGE. EVERY SORT OF CREATURE FROM A MOUSE TO A LION CUB IS FOUND GIVING COMFORT TO SOLDIERS by Clive Marshall. The Daily Ardmoreite, Ardmore, Oklahoma, 8th August 1918, pg 6

An American officer remarked the other day that men who did not believe in the influence of mascots didn’t believe in anything. This may be stating the case strongly, but it certainly is true that sentiment in war, as in other affairs of life, finds a very strong expression in the widely prevalent habits among American soldiers of cherishing mascots . . . when it comes to living mascots, the fighters have a collection big enough to stock a zoo . . . a number of the [aviators] have dog mascots also, and one Parsons, had a black cat.

It would not be long before war again broke out across the world. The Second World War can be considered "unfinished business" resulting from the First World War.

SECOND WORLD WAR

The life of cats is better documented for the Second World War and I've found much information in old cat books by Sydney France, Grace Cox-Ife and P.M. Soderberg as well as in newspapers of the time and issues of "The Cat" (Cats Protection) and "Our Cats" and "Cats and Kittens" (cat fancier magazines of the time). Information about pets during the war can also be found in Bonzo's War by Clare and Christy Campbell, in an illustrated lecture "The Great British Cat and Dog Massacre of World War Two" by historian Dr Hilda Kean, Dean of Ruskin College, Oxford at the University of Greenwich (05/05/2010); The State Library of Victoria (they hold many non-copyright photos by Sport & General Press, Topical Press) and there are many online archives of information about this period. Many people were worried about the threat of bombing and food shortages, and felt it inappropriate to have the luxury of a pet during wartime.

Feeding

In the years before rationing, the cats' meat man was a familiar sight in towns. He sold skewers of meat unfit for human consumption to pet owners. This was generally horsemeat and trimmings of other meats. It was often rotten or fly-blown and owners first had to clean it, but in the war years, the "War on Waste" saw even this vanish from the streets. There were strict rules governing the disposal of livestock killed or injured during air raids. All usable meat from those casualties - horses included - was supposed to go for human consumption. Older cat owners could still remember the early 1900s when books advised them to trap sparrows on limed sticks as a tonic for their cats; for them, this source of food became important in wartime and catching sparrows became a kind of sport for some children.

It was the shortage of food, not the threat of bombs that posed the biggest threat to wartime pets. There was no food ration for pets. A 1939, a Kit-E-Kat advert advised owners to keep their rations for themselves and give the cat Kit-e-Kat, but this advert vanished soon afterwards and Kit-E-Kat did not reappear until the late 1940s. The "Chappies" pet-food factory in Slough, Berkshire, was shut down. Many owners managed to feed their pets, buying horsemeat and sharing their own rations. Town cats often supplemented their diet by hunting the rodents that set up home in bombed buildings.

Rural cats managed better. One rural cat took home a grown rabbit every day, which the family shared until the grim day when the cat was found killed and the daily rabbit stolen. It evidently had been on its way home. A similar case was reported of a cat (called "Cat") belonging to a widow and her 10 year old son. When the family could not afford to feed Cat, they decided to have her "put to sleep." Cat seemed understand the family's predicament and turned up on the morning of the fateful day with a dead wild rabbit for the pot. Throughout the war, Cat provided several rabbits each week - often rabbits bigger than herself - and waited patiently for her share.

During wartime, many households in more rural areas continued the habit of keeping a stockpot warming on the back of the range. It contained plenty of water, bones from meat joints (for the gravy) and any leftover meat along with grains and pulses. A rabbit could be added if available. The stock was boiled for a few minutes daily and a little of this stock was poured over well-toasted bread crusts or served as mush to the family cat. As for cats in town, another source of food, that my mother recalls, was fish. Unfamiliar types of oily fish were imported to feed the populace, but many people fed the unfamiliar stuff to the pets instead of eating it themselves.

During wartime, there were changes to livestock farming and butchery. Many farmers disposed of their sheep because these needed large grazing areas, but did not quickly lay down meat. Many got rid of their sheep to make room for thriftier livestock; stock that needed less grazing land, or could forage, and that quickly laid down meat. This reduced the amount of mutton available. The Ministry of Food controlled the distribution of food and butchers were set targets to produce a high percentage of useable meat from each carcase; less bone and fat were trimmed away and discarded. In the "waste not, want not" climate, housewives contrived meals from the less appetising cuts and offal, and from scraps that would once have been given to pets. The parts that were genuinely inedible to humans could have industrial uses or be returned into agriculture. There were no longer any scraps for the cat's meat man to buy from abattoirs and sell to cat owners, or to go into commercial cat food production. Such measures hit urban cats hardest as they were more dependent on their owners for food and wartime meatless rissoles lacked both appeal and nutritional value.

Fresh eggs, once considered a tonic food, and milk, considered a staple food, also vanished from the feline diet. Eggs were supplied in powdered form rather than fresh (for better shelf life, plus misshapen or cracked eggs were also used). Milk too was powdered. In the privacy of their own homes, many owners did manage to set aside a little of these for their pets, but woe betide if a nosey neighbour reported this frivolous use of food! Suburban households that raised chickens and rabbits might give the heads and entrails to the cat.

As the war continued, the question of what to feed pets became more critical. Farmers were encouraged to switch from livestock (with the exception of dairy cattle) to food crops. This further reduced the availability of meat.Animal welfare societies once again provided suggestions, but in August 1940 the "Waste Of Food Order" was passed by Government. At first the Ministry of Food declared it to be an offence to waste any food by giving it to pets, but they later clarified this to mean the wastage of food fit for human consumption. This was punishable by two years' imprisonment and only applied to "non-essential" animals that didn't contribute to the war effort. "Essential" animals included factory cats that hunted the rats and mice that ate grease from machinery and the cats employed as rodent controllers in places where food was stored. Milk was rationed in 1941, but cats employed in controlling rodents were allocated an allowance of milk powder. This allowance came out of powder damaged or otherwise unfit for human consumption. Behind closed doors, owners continued to share their own rations with their pets.

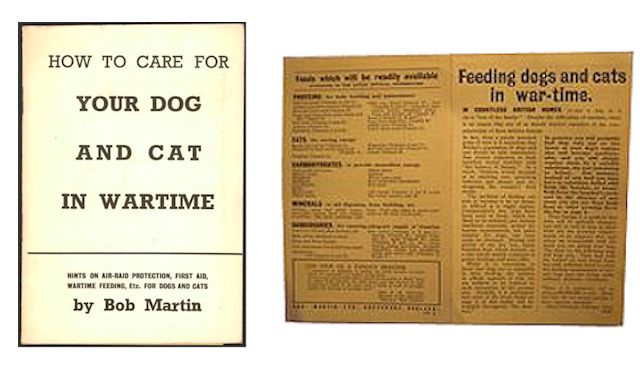

The Sherleys Cat Book had been published regularly since 1925. The preface to the 8th Edition had an additional remark on feeding and on the availability of Lactol (which I've highlighted in red).

A Government anti-cat briefing was leaked to journalists: "Too many of this country's 7 million cats are overfed, given portions of meat and fish which, to a man, would be the equivalent of a 3lb joint every lunchtime." It was widely reported that cats consumed 40 million gallons of milk a year. The Chancellor even considered a cat tax. Nothing could deter the most devoted cat rescuers and the Animal Defence Society reported the example of "a poor old woman who lived in a tiny room [ . . .] swarming with cats who she had rescued and befriended. Most of these people would give their last crust to their cat or dog."

In "Your Cat" (published 1951), P.M. Soderberg wrote: "Since 1939 a very serious situation has developed for cat breeders, for from that time many articles which had formed part of the customary diet were not available. There was also an Order issued by the Ministry of Food, which forbade the use for animal feeding of all foodstuffs that were suitable for human consumption. Many breeders were compelled by these circumstances to cut down their stock. Few indeed gave up the unequal struggle and disposed of all their cats, for the majority, at the expense of considerable time and no little ingenuity, managed not only to keep their cats alive but also to keep them in good health and sound condition. For those who could obtain it, horsemeat was a great help, but where no source of supply was available, fish offal, when added to the ordinary scraps from the table, had to suffice. Continuous feeding of this type, however, is not satisfactory, for it is too wasteful of effort and demands considerable care if the animal is to be well nourished and at the same time regard its food with enthusiasm. Lack of variety is not appreciated by cats any more than by humans, and even the most attractive foods pall after a time. This chapter deals with the feeding of cats which was possible before the war, and which it is hoped will again be possible in the not too distant future."

After the Second World War, meat remained in short supply and could not be wasted on pets. Whale-meat and horsemeat, and more of those unfamiliar fish of course, entered the human diet and were also fed to cats. One recipe for cats was cooked horsemeat or whale-meat with brown bread and either broth, green vegetables or raw grated carrots. The evening meal was bread with gravy, or fried bread cubes or baked crusts. Once a week white fish was added if any was to be had.

Cats fattened on scraps or on rats and mice (which risked plague proportions in bombed out areas) risked becoming "roof rabbit" in some family's stew or pie in times of hardship.

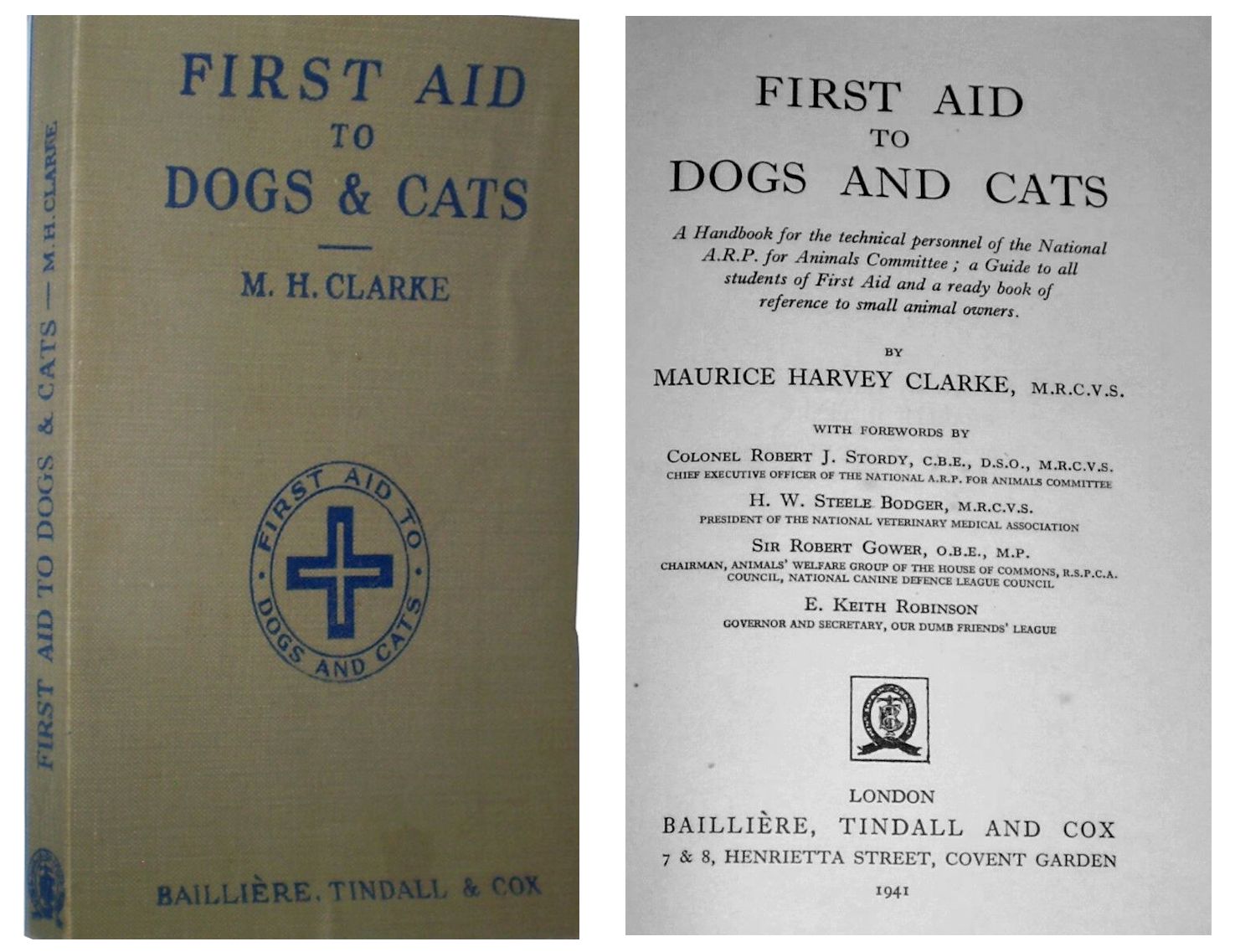

Wartime First Aid

Compared to modern cat owners, the owners of that era were still accustomed to making home remedies. First aid for cats in wartime included ointment for gas burns: 2 parts bleach powder and one part petroleum jelly (Vaseline). Sedatives were recommended for cats during air raids, but these were not without their problems as bromide caused depression if used frequently, while luminal and chloretone had to be given as tablets, but were too large to put down the cat's throat intact. Aspirin was also used as a sedative and no doubt many cats died as a result.

Other treatments were common household remedies. Minor burns or scalds were treated with cold strong tea, tannic acid, or a solution of bicarbonate of soda and water made of half a teaspoonful to a quarter of a pint. Earwax could be cleaned out using a homemade cotton bud dipped in diluted methylated spirit. Aspirin was used for colds and snuffles, while turpentine vapour was used to treat for bronchitis. When obtainable, a raw beaten egg made a wonderful conditioner, though this wasn't feasible in wartime when there were no spare eggs to be had. Before the war, sweetened yoghurt, available from the larger dairies, was also recommended.

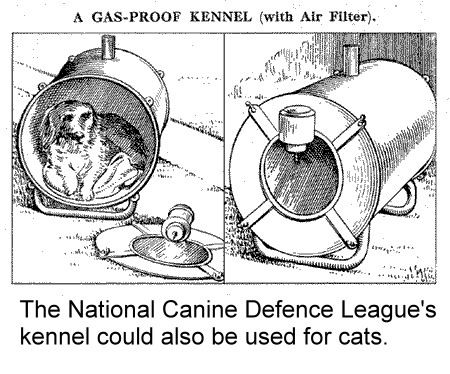

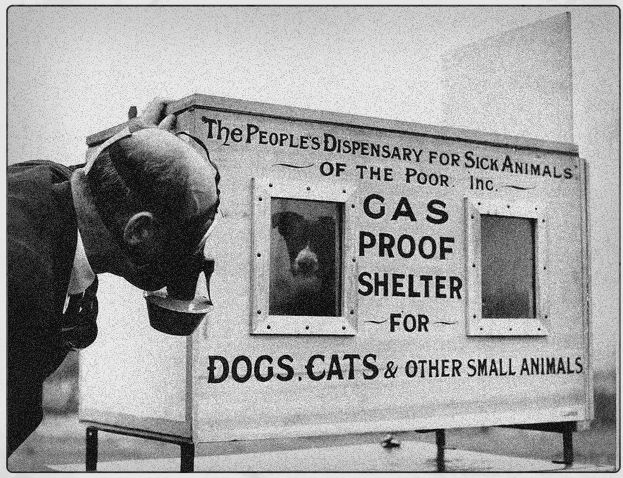

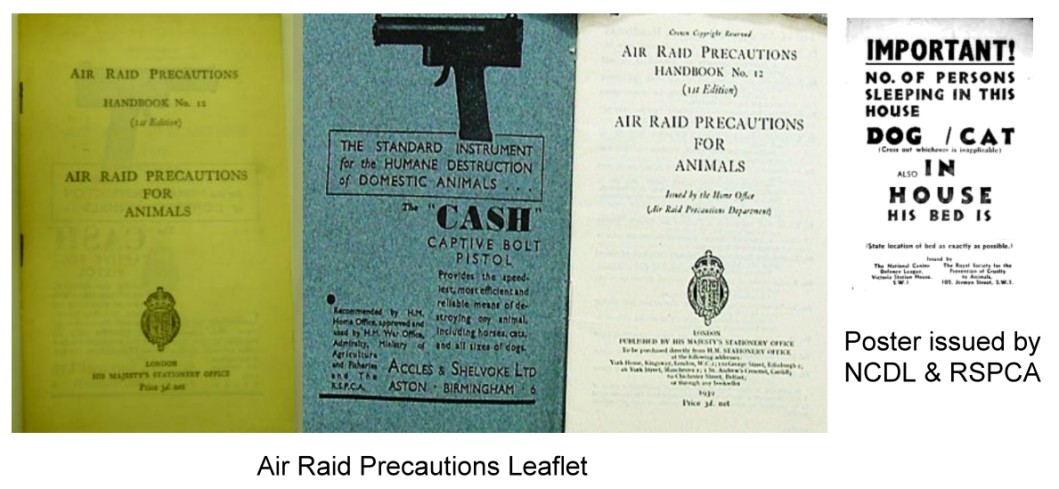

Special tranquilliser mixtures to calm distressed pets were advertised, as were doggy earmuffs and even animal gas-masks (more suitable for dogs than cats). Cat owners might make do by hanging wax-cloth over the cat basket and hoping for the best. In 1939, a French scientist invented a gas mask for pets. NARPAC issued the following advice on building a gas-proof kennel: A large wooden box, e.g. a tea chest, was to have the cracks stopped up by pasting paper or a waterproof fabric over the them. The lid was a wooden frame with a mesh centre. In the event of a gas attack, the lid and sides were to be covered with a thin blanket wrung out in cold water. Luckily mustard gas, or other blister gases, was not used, the Germans preferring to use incendiary bombs.

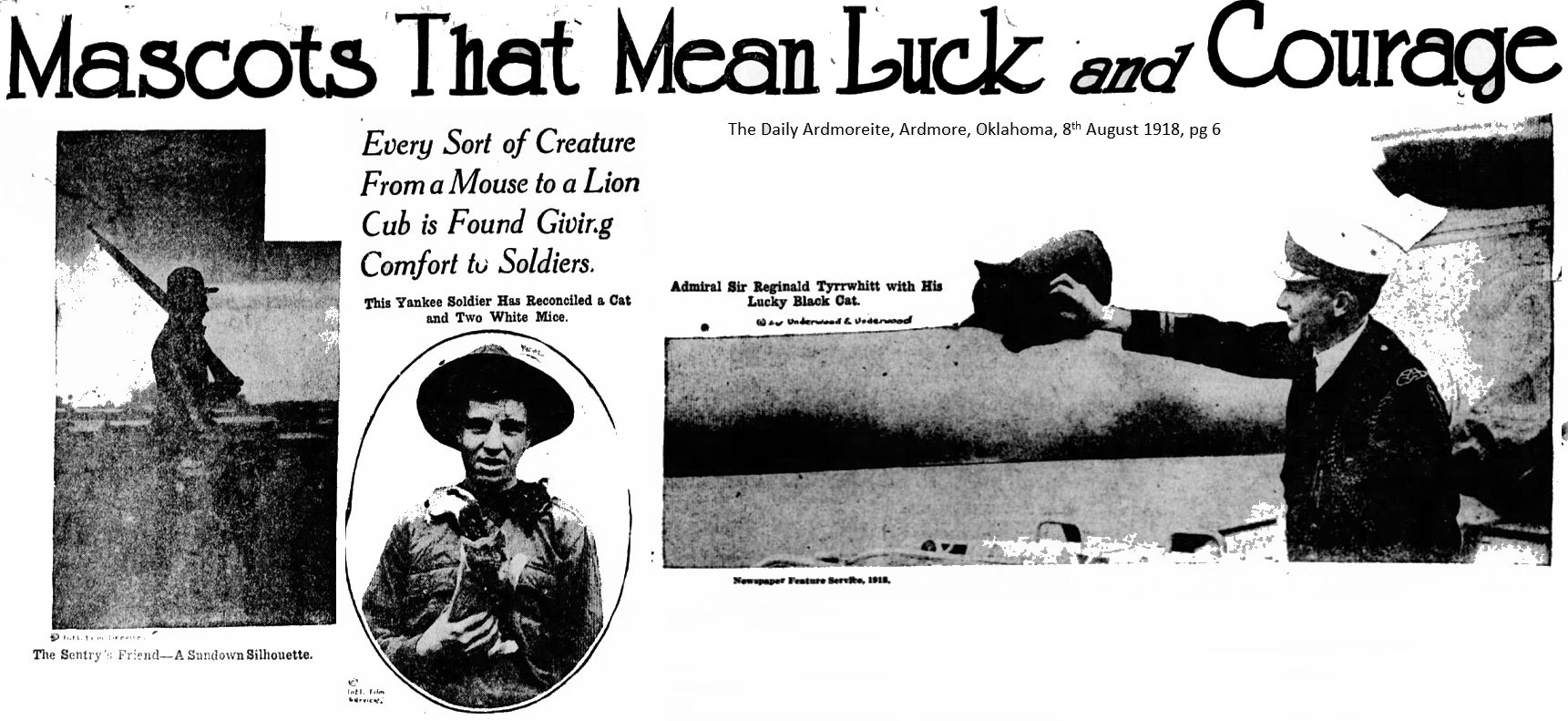

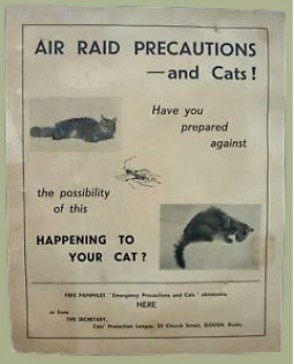

In 1939, Bob Martin (the maker of conditioning powders) published a booklet called "How to Care For Your Dog and Cat in Wartime". The kennel should be placed in a trench in the ground to protect it from the blast and from flying splinters or debris. The Edinburgh Evening News of 28th August 1939 told its readers: The problem What shall we do with our pets? was referred to on the Radio the other evening, when Air Raid Precautions for Animals Handbook No. 12 (obtainable from H.M. Stationery Office, George Street, price 3d) was brought to the notice of listeners. Animal owners will also be interested in the Emergency publication No. 2 (Equipment) issued by The Cat, the journal on cat welfare issued by The Protection League, 29 Church Street, Slough, Bucks. Gasproof kennels, travelling boxes and baskets, gloves, sheeting, tinned and packed foods and milk powder, and first-aid requisites are all mentioned in the publication, with the names and addresses of suppliers. Fortunately, most chemists and stores keep stocks of the various articles and foodstuffs likely to be required if the worst should happen. This list is contained in the August issue of "The Cat" (2d monthly).

ANIMALS & A.R.P. SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS

This is from te Cleveland Standard, 2nd September 1939, and was printed in most regional papers around the same time.

The R.S.P.C.A., Our Dumb Friends' League and the National Canine Defence League are acting in complete co-operation with the National Veterinary Medical Association and the P.D.S.A. on the question of dealing with animals in the event of emergency. All individuality has been set aside to undertake this national service. Transport, personnel and equipment have been pooled. The Societies are collaborating under the Air Raid Precautions Department of the Home Office which has caused the formation of the National A.R.P. , Animals Committee. Arrangements have been made for the full co-operation of the Veterinary Profession and these Societies in order to undertake the service that the Government have asked them to render in the event of national emergency. All personnel will be under the direction of Colonel R. J. Stordy, C.B.E., D. S.O., M.R.C.V.S., who has been appointed the Chief Administrator for the Committee. To meet any immediate emergency arrangements are being rapidly completed. The attention of the public is drawn to the following general recommendations for dealing with their household animals:

(1) Send or take them into the country in advance of an emergency;

(2) Provide dogs with muzzles and leads and cats with baskets if travelling by public conveyance;

(3) Should you decide to keep your animal with you, find out at once the nearest Veterinary Surgeon or local Centre of an Animal Welfare Society in case their help is needed. If you do not know already, any local police officer will tell you;

(4) Remember that animals will not be permitted to enter public shelters. Of course, if you have a suitable private shelter you should take them with you, but muzzle your dog and put your cat in a basket, for frenzied animals are dangerous and difficult to handle;

(5) If you and your family have to leave your home at very short notice and cannot take your animals with you, in no circumstances leave them in the house or turn them into the streets. Remember your animals cannot accompany you under the Government Evacuation Scheme. It is needless to destroy your animals if you can find neighbours to take care of them, but should dire necessity demand ensure their painless destruction by taking them to the nearest Veterinary Surgeon or local Centre of an Animal Welfare Society. Do not take them to the police station as the police will not be able to deal with them

Those without private shelters faced a huge dilemma. Some chose to stay at home with their pets rather than go to a public shelter without them. The Mass Observation project, which recorded the responses of ordinary people to the war, recorded the account of a man from Poplar, East London: "I know the missus and kids are safe, but if I went to the shelter, too, I'd be thinking about how the animals were getting on." One cat owner in London even telephoned the Lord Mayor of St Pancras demanding an air raid shelter for her cat. Another handed her gas mask back to the ARP saying her cat got frantic whenever she put it on: "The gas will just have to poison me because I won't have Tibby upset."

The Government failed to take into account that many cats and dogs were no longer utilitarian animals; they were part of the family. One woman in the south-west of England had been forbidden to return to her home because of an unexploded bomb. When a War Reserve Constable refused permission for her to go inside to feed her cat, she sneaked through the barrier to do it. She was fined 1. It also turned out the Constable had been sympathetic to her plight and had fed the cat himself.

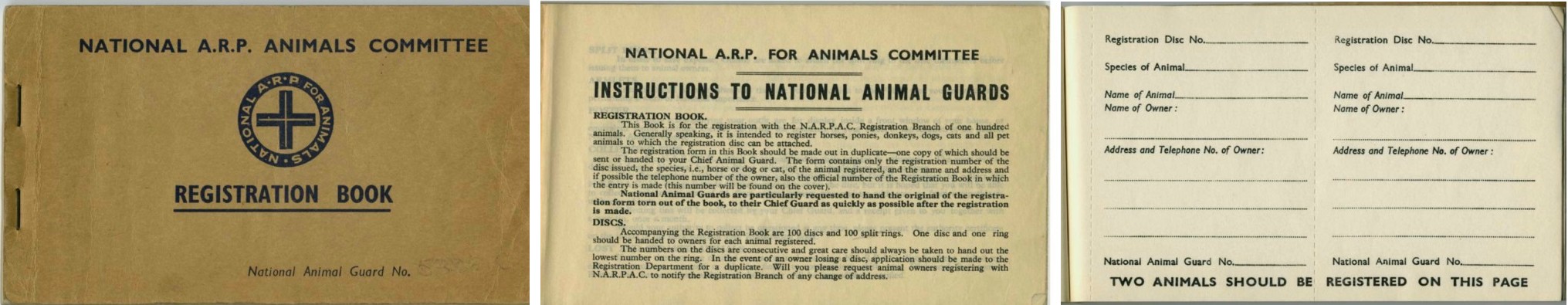

NARPAC

Just before the outbreak of the World War, the Home Office's National Air Raid Precautions Animals Committee (NARPAC) with a retired vet as chairman. NARPAC (described as a sort of "Dad's Army for Pets") drafted its "Advice to Animal Owners" pamphlet: "If at all possible, send or take your household animals into the country in advance of an emergency [ . . . ] If you cannot place them in the care of neighbours, it really is kindest to have them destroyed." This advice was printed in almost every newspaper and announced on the BBC. NARPAC would also act swiftly in a crisis, offering refuge to lost or frightened animals, treating injuries or painlessly putting them out of their suffering. A Home Office pamphlet dictated that pets would not be allowed in public air-raid shelters. The pamphlet featured a do-it-yourself guide to putting animals down and on page two there was an advert for a captive bolt pistol.

On the other hand, pet cats could be issued with a NARPAC collar and registration disc that ensured their return if they were found straying during, or after, a blitz or blackout. The disc read: "Finder Please Report This Number To Nearest National Animal Guard". The National Air Raid Precautions Animals Committee was established to ensure the well-being of domestic and working animal under war conditions, a national register was set up and registered animals were issued with a NARPAC numbered disc attached to a collar as identification. The NARPAC Animal Service were responsible for working animals (e.g. horses) while the NARPAC Animal Guard were predominantly women who were responsible for the welfare and registration of domestic pets covering a few streets in their local area.

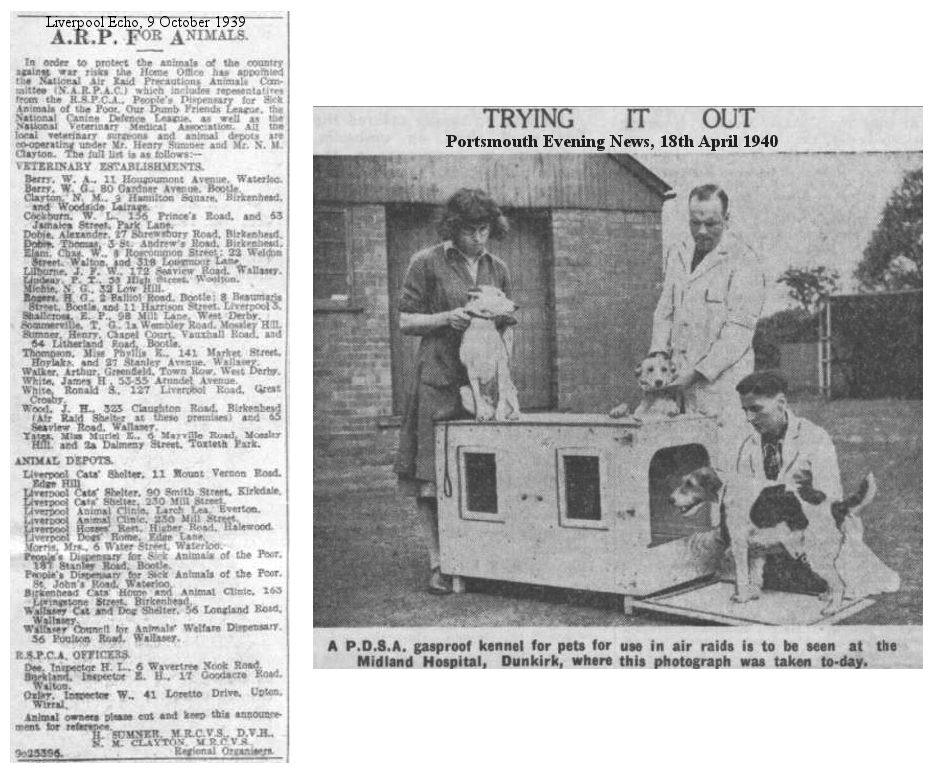

A typical notice published in regional newspapers in October 1939 read:

Air Raid Precautions for Animals 1939

In order to protect the animals of the country against war risks the Home Office has appointed the National Air Raid Precautions Animals Committee [N.A.R.P.A.C.] which includes representatives of the R.S.P.C.A., Our Dumb Friends League, as well as the National Veterinary Medical Association. All are co-operating under Mr Henry SUMNER and Mr N. M. CLAYTON

Full list:-

Veterinary Establishments

[a list of local veterinarians]

Animal Depots

[a list of local animal shelters]

Letters that appeared in local newspapers make it clear that many families considered their animals as important as themselves and societies such the the R.S.P.C.A. and Our Dumb Friends League offered advice and help, including appeals to finders of bombed out animals to offer temporary shelter until it could be collected by one of these organisations. Elastic collars with ID discs were recommended so that stray pets could be returned to their families.

FIRST AID FOR ANIMALS. Animal lovers will be interested to learn that the Portsmouth Shelter of Our Dumb Friends League at 449 Commercial Road, has been specially equipped to deal with dogs and cats which receive injury from air raids. Once the all clear signal has been given, a trained staff will be on duty at the shelter to give expert attention to animal casualties. This organization for the treatment of animal air raid victims has been arranged by the National A.R.P. for Animals Committee of which Our Dumb Friends League is, of course, a prominent member. (Portsmouth Evening News - Thursday 18 April 1940)

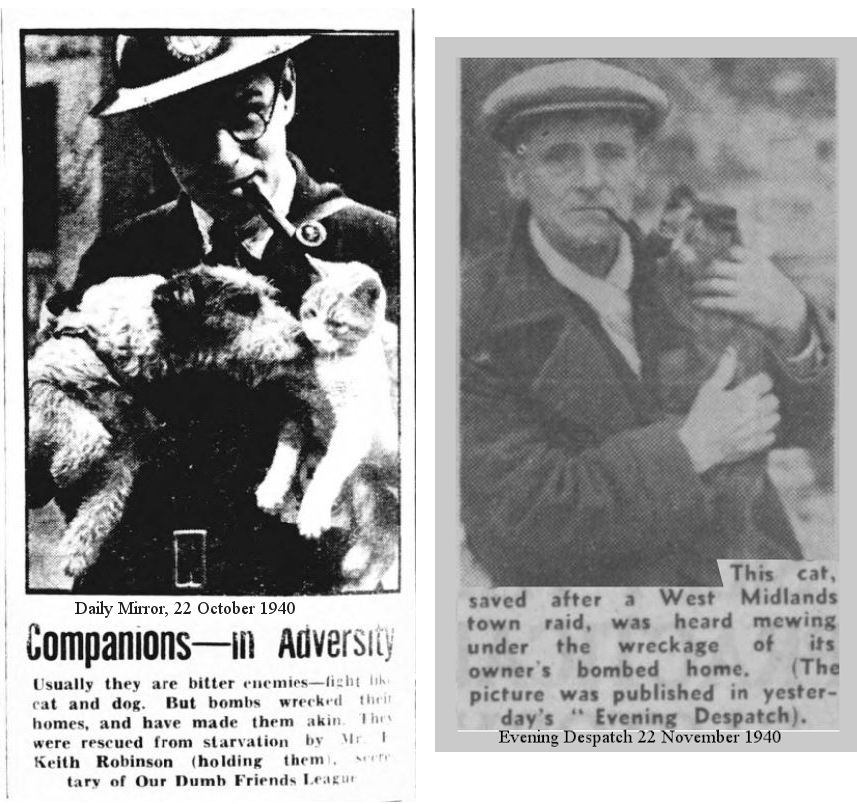

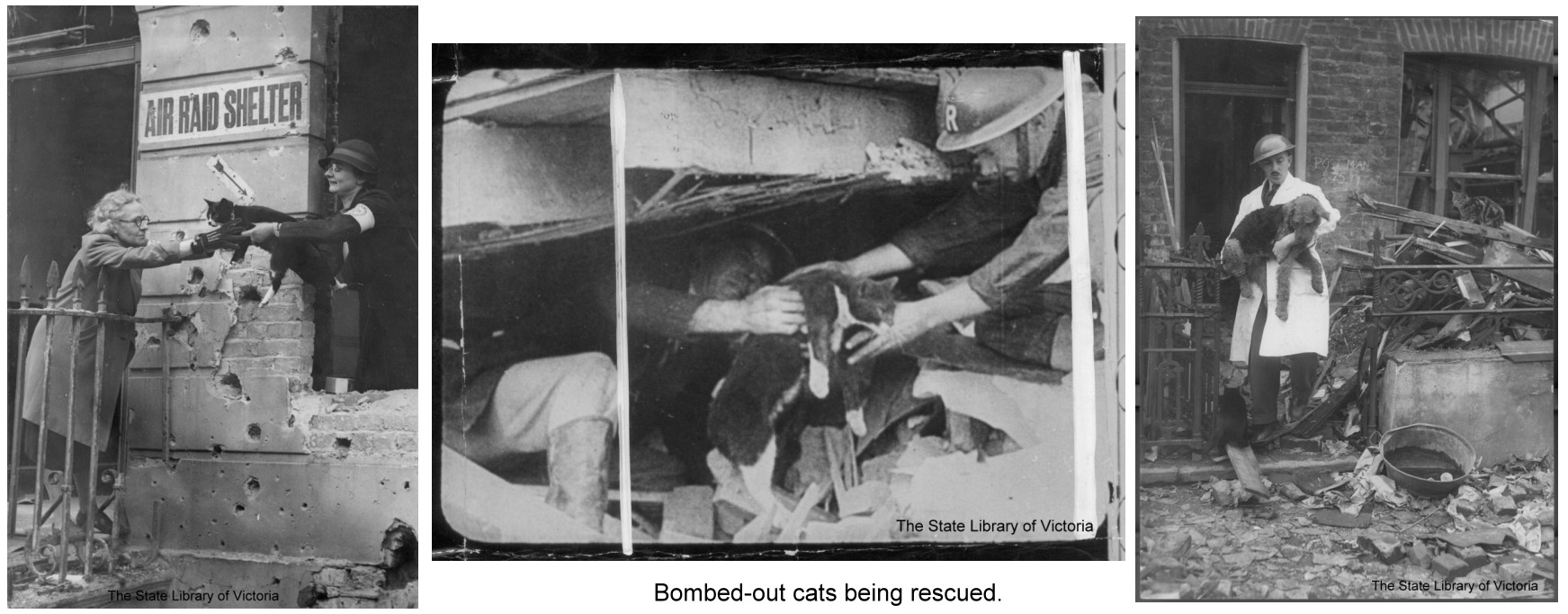

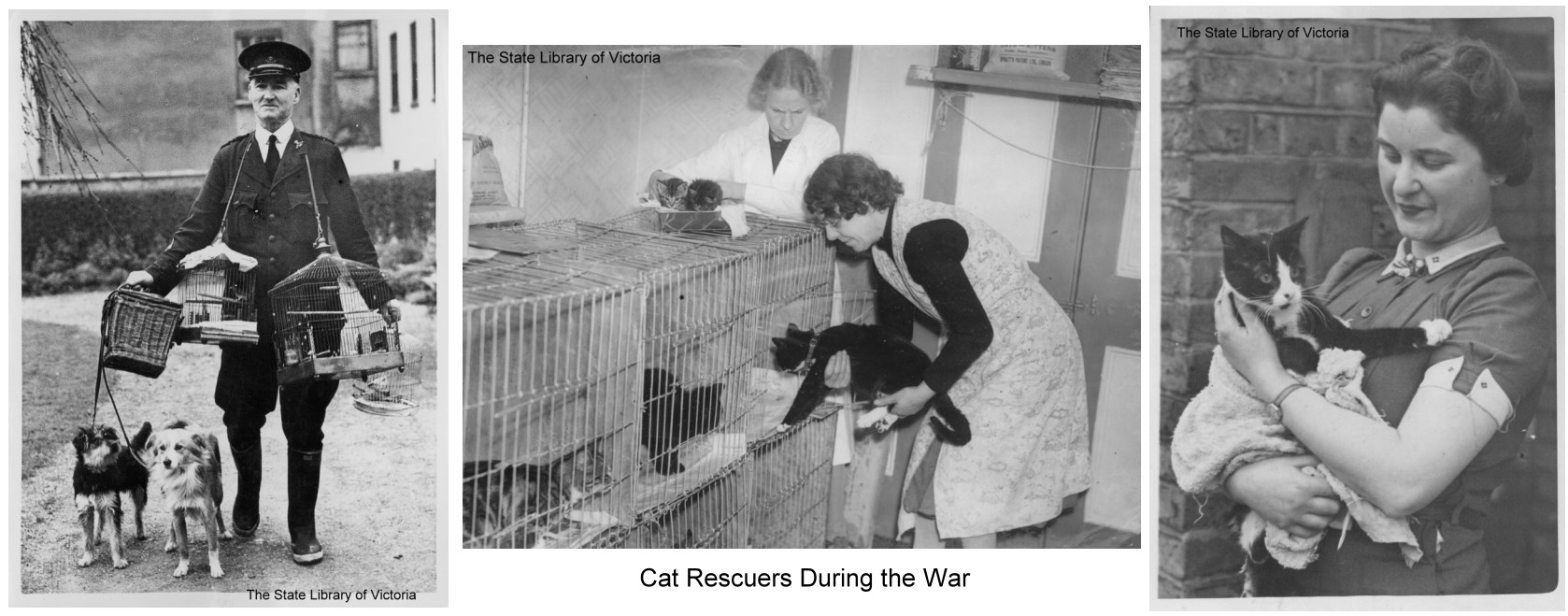

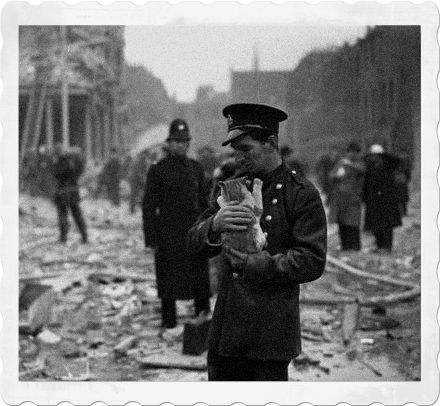

PETS LOST IN RAIDS. CAT LOVERS TO THE RESCUE. PROBLEM of collecting and caring for the large number of half-starved cats left homeless by air-raid damage and forgotten by their owners is now being solved. Cat lovers all over the country are being asked by Our Dumb Friends League to form themselves into voluntary corps of rescuers to save all pets found among the debris of bombed houses. Many families have had leave their homes hurriedly for various reasons, and in the rush their pets often have been left behind. The league has made arrangements to look after the animals. . It is a pitiful sight to see these half-starved strays wandering about the ruins of their homes " an official of the League told a reporter, and we are determined to do everything we can to save their lives. We are asking them to keep a look-out for these strays and when they find one, take it in, give it temporary shelter, and then notify the League. As soon as possible we will send for the animal, but until we can do so arrangements will made for food for the cat to be supplied to the rescuer. We shall be very grateful for any help that is offered, and cat-lovers ready to give assistance should send their names and addresses to the League. At the same time we earnestly ask owners of cats not to go away and abandon them. If the League is given reasonable notice they will come and take the pets away. (Lincolnshire Echo - Wednesday 13 November 1940)

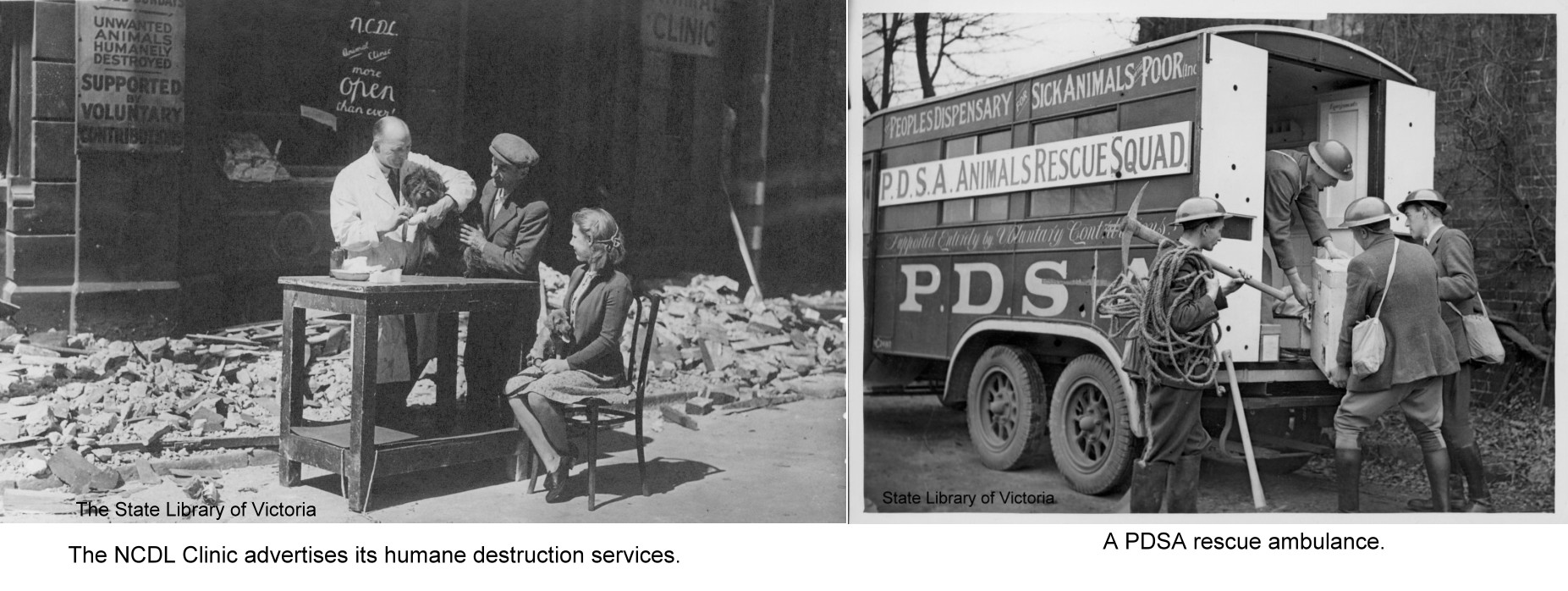

CATS KEEP NINE LIVES TRADITION MIDLAND TOWN S RESCUERS SAVE 400 ANIMALS. More than 400 animals have been rescued during the past week by the R.S.P.C.A. branch of one Midlands town and by A.R.P. workers from the wreckage of bombed houses. The R.S P.C.A. took them to a veterinary surgeon, doctored them and housed them until they were claimed. Cats seem to know instinctively when enemy bombers are about and when danger is near. They immediately dive under a table, and wriggle their way to safety afterwards. The Secretary of the Midlands R.S.P.C.A. branch referred to, has explained that hundreds of animals have been among the victims of the Nazi air raids in the last few days. He said it was amazing the way so many cats had wriggled to safety out of demolished houses. Dogs were not so fortunate, because they were bigger, and much more easily frightened. (Evening Despatch - Friday 22 November 1940)RAID INJURED ANIMALS Mr. E. Bridges Webb, councillor mid general secretary, The People's Dispensary for Sick Animals, writes: I believe your many animal-owning readers will be glad to learn that one of our specially equipped rescue squads, with motor caravan dispensary, is stationed at 7, Broad-Street, Pendleton, Salford, ready to hurry out night or day to any place within a 40 mile radius that may be attacked in an air raid. The motor caravan dispensary equipped with all the medicines, drugs, instruments, etc., for treating injured animals on the spot, or for destroying them humanely if there is there is no reasonable chance of their recovery. The members of the squads are picked volunteers who have already saved thousands of animals since the raids began. (Burnley Express - Saturday 14 June 1941)

ANIMALS IN AIR RAIDS. Sir, The Prime Minister s recent announcement that further and heavier air raids may be expected must lead us all to consider the preparations we can make to ward off the worst effects of these raids. Thus I would ask the courtesy of your columns to advise animal owners in Coventry. The League s experience of animals and bombing is enormous. Since the raids began we have saved 62,070 dogs, 170,912 cats, 892 horses, 953 birds, and 602 other animals. Prom this mass of experience three points stand out; animals should be left free so that they can make their escape before a building is hit; they must have some form of identity, of which the best is the disc issued by the National A.R.P. for Animals Committee; and owners should immediately make themselves aware of the name and address of the nearest veterinary surgeon or animal rescue party. Yours, etc.. E. KEITH ROBINSON. Governor and Secretary, Our Dumb Friends League London. SW.1. (Coventry Evening Telegraph - Wednesday 30 July 1941)

DON'T FORGET THE PET Sir, -May I appeal through your columns to your readers, to soldiers in camps and billets who may be moving camp, evacuees from big cities returning to their own homes, and more particularly the children who may be going back to their parents and who have acquired a dog or cat or other pet animal, not to leave them behind. I would urge them to get touch with animal dispensary or shelter, or local organizer for N.A R P.A.C and arrange for these animals to be dealt with it they are unable to take them to the new address when they remove. Much animal suffering will saved in this way. Yours etc., E. Keith Robinson. Secretary. Our Dumb Friends' League. Grosvenor Gardens House, Victoria, London, S.W.I. (Portsmouth Evening News , 25th May 1942)

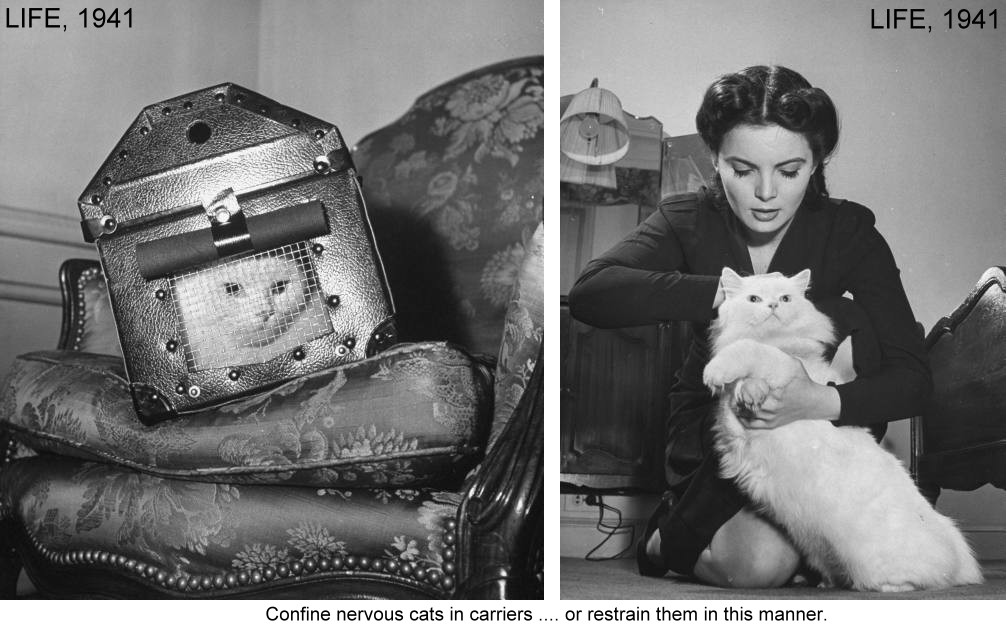

Meanwhile, in the USA, LIFE magazine published photographs showing how to care for pets in the event of an air raid: cats should either be confined in their carriers to prevent them from panicking (and to speed evacuation if it became necessary) or restrained in the manner shown (though I doubt this would be effective with a truly panicked cat). No doubt many British cat owners were doing exactly the same things if their cats hadn't already retreated into some safe bolt-hole such as under the stairs or the Anderson Shelter in the garden.

The Great Cull

It is a mistake to destroy your pets. The wholesale destruction of cats and dogs might well result in a plague of rats and mice. (S. Evelyn Thomas, "Handy War-Time Guide for the Woman at Home and the Man in the Street").

In one of the overlooked tragedies of the time, wartime panic drove Britain to slaughter 750,000 family pets in the first week of the war in 1939. Dr Hilda Kean gives a figure of "more than 400,000" in September 1939. The mass cull was based on government advice and the false assumption that putting down pets (a "luxury") was the patriotic thing to do. Some animals were drafted into service during the war, many civilian animals, particularly those in cities were massacred or abandoned when war was declared. Yet there was to be no bombing until April 1940, nor any rationing of food for animals until later. According to Dr Kean, the government hadn't issued any orders for pets to be destroyed and the National Air Raid Precautions Animals Committee (NARPAC) appealed to owners NOT to arrange needlessly for the immediate destruction of dogs and cats.

During the Munich Crisis of 1938, when Germany had occupied parts of Czechoslovakia, animal charities had been besieged by pet-owners fearful that the inevitable war would result in poison gas being dropped on British cities. Owners feared that pets would become hysterical at the sound of sirens and explosions, and run wild through streets contaminated by mustard gas. On the day that Hitler invaded Poland, a BBC broadcast confirmed it was official policy that pets would not be given shelter.

The June 1938 issue of "The Cat" advised readers "It would be necessary to put [cats] to sleep if air raids began, to save them from mutilation and pain; we suggest that cat owners should make up their minds now, while there is no danger, so that there would be no hesitation or loss of time if the danger were to materialize." It would be 15 months before the first air raid on Britain and some cat owners evacuated their cats to the countryside. Inevitably there were boarding catteries that took advantage of the situation and some city cats spent their time moping or pining in overcrowded catteries, shut in darkness for most of the time.

The Government set MI5 agents to watch animal rights activists. It considered the mass euthanasia of all "non-essential animals" and even sponsored a clandestine anti-dog hate campaign ("Tell the public they eat 280,000 tons of meat per year!"). Cat owners could be prosecuted for giving their cats saucers of milk. Except possibly for the rabbits and chickens raised for food in back gardens, pet animals consumed resources such as milk, meat and grain.

Signs were posted "Animals humanely destroyed" directing owners where to go. The Royal Army Veterinary Corps and the RSPCA advertised that dogs were needed for the war effort - an alternative to killing the family pet. "Putting your pets to sleep is a very tragic decision. Do not take it before it is absolutely necessary," urged the Daily Mirror.

After war was declared on 3 September 1939, pet owners thronged to vets' surgeries and animal homes. Animal charities, the PDSA, the RSPCA and vets were all opposed to the killing of pets and very concerned about people just dumping animals on their doorsteps at the start of the war. Many people contacted Battersea Dogs and Cats Home after the outbreak of war to ask for their pets to be destroyed, either because they were going off to war, they were bombed, or they could no longer afford to keep them during rationing. Battersea advised against taking such drastic measures and wrote to people asking them not to be too hasty. The RSPCA gloomily pronounced that the primary task for them all would be the destruction of animals.

The result of the Government's advice resulted in panic. When air-raid sirens sounded for the first time, not only did families pull the blackout curtains, many turned out their cats and dogs into the street to fend for themselves. Thousands of once-loved pets were tied up in sacks to be thrown into canals or simply dumped in back streets and alleyways. A council vet in East London recorded the events of that first day: "The sirens sounded [. . .] almost immediately West Ham Town Hall became besieged by panic-stricken people bringing their animals for destruction [ . . .] In spite of trying to reason with the hysterical mob, we were soon inundated with dogs and cats whose owners had abandoned them in offices and corridors." That night, distressed animals cast out by their owners roamed the blacked-out streets. Five days of mass destruction followed. A local rendering firm was stacked several feet deep with dog and cat carcasses.

In the first few days of war, PDSA (Our Dumb Friends League) hospitals and dispensaries were overwhelmed by owners bringing their pets for destruction. Their technical officers would never forget the tragedy. In Memoriam notices appeared in newspapers and magazines with words to the effect of "given sleep to be saved suffering during the war." Many children were told that their pet cat or dog had "run away."

After the first few days, the rate of killing slowed and shock set in. Some animal lovers were appalled by the way the Government had created such a sense of panic. Nina Mary Benita Douglas-Hamilton (the Duchess of Hamilton), 1878-1951, was a notable animal rights campaigner at this time. She established an animal sanctuary in a heated aerodrome on her Wiltshire estate, Ferne, during the war. Being both wealthy and a cat lover, she rushed from Scotland to London with her own statement to be broadcast on the BBC. "Homes in the country urgently required for those dogs and cats which must otherwise be left behind to starve to death or be shot." She sent her staff out to rescue pets from the East End of London and hundreds of animals were taken to her home in St John's Wood before going to the Ferne sanctuary. One Swedish aristocrat opened her Mayfair mansion as a sort of urban ark.

While some families abandoned their cats to fend for themselves, some cat lovers took on large numbers of those abandoned cats and did their best to care for them during the war years. Some of those cat lovers later had to be helped by the Dumb Friends League and other organisations, while others somehow managed to house and feed the cats themselves and regularly risked being fined for giving meat or fish to them. Their argument was did it matter if they gave their own rations to the cats? - they weren't depriving anyone but themselves (the counter argument was, of course, that they should have given their evidently unwanted ration to a needy person). There are newspaper reports of people being fined for picking up "scraps" of fish or meat from the ground to give to their pets when those scraps could have been washed and sold for human consumption.

Kindly old ladies set up their own refuges. Some pets were evacuated to more rural areas. The Canine Defence League dug its own air-raid shelters for dogs in Kensington Gardens. Sadly many thousands of cats were simply turned out to join feral colonies, such as that on Clapham Common in South London, which became home to a huge number of wartime strays. Even into the early 1970s the descendents of those cats inhabited areas damaged by bombing when those areas were redeveloped; notably a curly-haired kitten (named Tuoh) was trapped around Victoria and documented in cat books as the Victoria Rex. I remember a pair of black kittens being shown on Blue Peter in the early 1970s; they had been trapped and removed from a London bomb-site and were considered unusual because the guard hairs in their coats were white.

Where compulsory immediate evacuation took place, pets were not allowed on the transport provided by the authorities. Fleeing owners were advised to leave food and water for their pets and inform the police or animal welfare organisations that the animal was in the house. Sadly many of the pets were put to sleep, there being nowhere for them to go.

When major Nazi bombing began in the autumn of 1940, there was a renewed rush to abandon pets by the thousand. A West Ham veterinarian recalled blitzed streets "inundated with cats". Municipal parties went out on slaughtering campaigns using a mixture of electric shocks, cyanide and chloroform, sometimes killing 100 animals at a time. With so many animals to deal with, mass culling became the only option. That West Ham veterinarian refused to give up his own cat, Ginger, who proved staunch even in the midst of an air raid, "welcoming me home each night amid the injustice of man's mad warfare". Many owners refused to part with their pets. When my father's family moved from their bombed out home in Oxfordshire they took the family cat with them.

By the end of 1940, Our Dumb Friends League (Blue Cross) had destroyed 106,392 cats. Many animal welfare societies were now working together and according to A Blue Cross history, many members of "The League" carried NARPAC ID cards, enabling them to enter bombed out areas where the general public were not allowed. They, and the PDSA, contributed several thousand pounds towards NARPAC (the RSPCA stumped up only 500). They were convinced that animal societies would cease to exist if the Nazis conquered Britain. The other animal welfare societties largely abandoned NARPAC.

It is not only on humane grounds that we should protect animals from the dangers and horrors of an air raid; it is also in the general interest of the community for, apart from their value to us, there is the danger that if we do not give them protection, frenzied and terror-stricken animals may well add to the confusion and perils of a raid. Although animals are immune from the effects of tear gases, and almost immune from the effects of nose gases, they are affected in the same way as human beings by the more deadly lung and blister gases. Moreover, animals contaminated by liquid blister gases, besides suffering themselves, would be a source of danger to persons coming into contact with them. (S Evelyn Thomas's "Handy War-Time Guide" )

On a slightly lighter note, at least for the animal concerned, Our Dumb Friends League took in the ship's cat of a captured German boat.

WAR TAKES HEAVY TOLL OF PORTSMOUTH DOGS [AND CATS] (Portsmouth Evening News, 20th January 1942) Rescue Work after Raids. For many years, by the courtesy of the Editor, I have been permitted in these columns to make an annual appeal on behalf of the local branch of Our Dumb Friends League. My personal knowledge of the splendid work done at the Shelter at Mile End covers a period of nearly 28 years, and I have never had reason to alter my opinion. A lot has happened since my last appeal; our City has been one of the worst victims of Nazi bestiality, and in this article it is appropriate that I should describe the work done for our dumb friends during those unforgettable visitations." The heroic work of Mr. W. A. S. Stevens (Veterinary Surgeon) and Mr. P. Cosway (R.S.P.C.A. Inspector) in regard to the rescue horses is well-known, and has been rightly recognized. My appeal, however, is in respect of the work done for the smaller animals, under the auspices of Our Dumb Friends League.

The Head-quarters at Mile End have indeed been a shelter for thousands of the little creatures: homeless, terrified, wounded, they have shared in the City s hours of trial. [. . .] On that memorable night of January 10 Mr. Jones [in charge of the shelter] had an anxious and strenuous time: with the Shelter full of cats and dogs, and with incendiaries and high explosives falling all around, one can imagine the task with which, single-handed, he had to cope. A high explosive dropped in the yard at the back of the Shelter and the building rocked ominously: considerable damage was done, but Mr. Jones contrived to block the window frames and to jam the doors. No sooner had he done this than a high explosive fell in an adjacent yard and undid all his work. He then had to begin the task of rescuing 17 dogs that had been buried In the strays quarters; 16 were retrieved safely, but one had to be destroyed because it was so badly injured. All the cats came through the ordeal unharmed, though few fled in panic, and It took day or two to recover them. [. . .] Owing to the damage to the Shelter it is no longer possible to take boarders, but otherwise the work is proceeding normally. [. . .] After the January raid thousands of homeless cats and dogs were dealt with. [. . .] By instructions of the Home Office the Shelter is not allowed to keep strays for more than three days, though the Nelson eye [turning a blind eye] is allowed where an animal is, from its appearance, likely to be claimed.

In addition to the strays there are hundreds of animals brought to the Shelter after a raid by people who have wither lost their nerve, or who feel that this world is no longer a place fit for decent animals to live in: most of them are painlessly put to sleep, but where good homes are still available they are given a chance. The Shelter, however, is willing to take care of the pets of people who have been rendered homeless until such time as they can find accommodation: no charge is made -in this connexion, and already nearly 300 dogs and cats have been cared for in this way. An indication of the effect of the war on the question of animal welfare can be gained from the fact that in September 1939 there were 8,000 cats and dogs brought to the Shelter for destruction in a fortnight.

Cats To Go to the Front?

On Sunday 28th January 1940, "The People" newspaper printed a page large devoted to the role of dogs in the war. Among the articles it printed this one: AND CATS TOO. Thousands of cats may be shipped to France to fight side by side with the B.E.F. at the Front. But they won t fight Nazis; they will help rid the trenches of rats! The plan is sponsored by Mr. A. A. Steward, organising secretary of the Cats Protection League, who is conducting an official inquiry into the uses of cats in war-time. Cats were successfully employed to rid the trenches of rats in the last war, he told me. We should offer to arrange the purchase of the cats; and not only would our vets see that they were shipped to France in a humane manner, but that they were properly fed and looked after.Did the Cats Protection League really support the idea of sending cats to the trenches where they would most likely perish? Apparently not, because the "The People" of Sunday 4th February, 1940 carried this retraction: CATS IN THE TRENCHES. In last Sunday s issue of The People a story was published suggesting that thousands of cats might be shipped to France to fight the rat pest in the trenches, and it was stated that a plan on these lines was being sponsored by Mr. A. A. Steward, organising secretary of the Cats Protection League. Mr. Steward now informs us that he did not, in fact, make the statements attributed to him in the story, and that, far from being in favour of such a scheme, he and his organisation would be definitely opposed to it. We regret the trouble caused to Mr. Steward by the publication of the story referred to.

Cat Theft

During the food shortages of 1942, Britons were turning increasingly towards wildlife as a food source. There was also an increase in cat theft. According the the PDSA's history of that time: Cats - in particular those with fine coats - were the main target, and it was suspected from advertisements which appeared from time to time that these animals were being stolen for their fur. But a further disturbing trend was the disappearance of small cats and kittens, which it believed were destined for the pot! As The (Our Dumb Friends) League pointed out, in a pie or stew cat can taste very much like rabbit. An extensive dossier was compiled and given to the MP Commander Richard Tufnell, a cousin of The League's chairman, Mrs Blanche Beauchamp Tufnell, who originall raised the matter in the house; but he was unable to get far because animal welfare was taking a back-bench position as the government pursued the war with a more implacable enemy.

FUR TRAPPERS OF THE BLACKOUT ARE AFTER CATS. (Birmingham Daily Gazette, 27th October 1939) An epidemic of cat stealing is going on during the black-out. Most likely explanation says Our Dumb Friends League, is that the cats are killed so that their skins may be made up into cheap furs. Animal shelters of the League have received very large numbers of enquiries during the past months from owners whose cats have disappeared.

CALL TO STOP CAT THIEVES SKIN GAME. Evening Despatch, 7th March 1942. An appeal to make the sale of cat skins illegal is to be made to the Home Secretary very shortly. High prices are being offered for cat skins; in Birmingham 2s. 6d. to 3s 6d. is a usual price per skin. The attention of the authorities is being drawn to this business," and also questions are to be asked in Parliament. Thieves are taking only cats in good condition, chiefly Persians and semi - Persians," said the Secretary of Our Dumb Friends League, Mr. E. Keith Robinson. The thieves appear to be well organised, and have a ready means of disposing of the skins.

KEEP AN EYE ON YOUR CAT (Coventry Evening Telegraph, 25th June 1943) From all parts of the country records come to Our Dumb Friends League of an epidemic of cat stealing. In the blackout hundreds of unfortunate animals are being caught and then destroyed for the sake of their fur. Apart from the theft and cruelty involved, cat stealing is a serious matter, because of the vital importance of cats in protecting the country s stocks of food from rats and mice.

UTILITY FUR COATS (Evening Despatch, 15th December 1944) It will be remembered that the disappearance of domestic cats with fine coats has been the cause of sorrow to many owners, and was thought that cat skins were used in the manufacture of cheap fur coats and other fur articles. This was admitted by the chairman of the Fur Trade Export Group. Our Dumb Friends League therefore approached the Board of Trade, requesting that the use of domestic cat skins should not be permitted, either in manufacture or export of utility fur coats. The Board of Trade concludes its reply by saying: It does not appear to the Board that this decision calls for any special action on the lines that you suggest. In other words, the Board of Trace declines to protect the animal-owning public from the possible loss of their pets. E. KEITH ROBINSON. Secretary.

If the idea of cats being eaten during food shortages seems beyond belief, I've come across books that had recipes for whale, seal, gull, badger and blackbird alongside recipes for the more commonly eaten game animals. The supposedly conservative British diet can become surprisingly diverse in times of hardship, but to disguise the meat's true nature (especially from children) it was often called "roof rabbit". In the countryside, roaming cats had always been at risk from rabbit snares.

In January 1943, The League made itself unpopular with the Fur Trade Export Group which had admitted using cat skins in cheap fur coat, but claimed the skins were obtained legitimately. The League produced evidence it had collected regarding the theft of cats for their fur and challenged the Fur Export Group to prove that they had not used any skins from stolen cats. If the Group could prove this, The League said it would issue a public apology. By the end of 1943, the Group still could not prove that no stolen cats were used in cheap fur coats. While cat fur was used as a substitute for more luxurious furs that were no longer to be had, dog skin was once again turned into leather as a substitute for soft calf leather (dog skin had been used for ladies' gloves in the less sentimental 19th Century).

There are also tales of stray cats (and probably pet cats going about their business outdoors) in some areas being used for target practice.

Early Warning Cats

Like the West Ham vet's cat, many pets became adept at coping when the sirens sounded. With their superior hearing, some even anticipated the warning. Many pets joined their family in garden air raid shelters, though others panicked and became dangerous or a nuisance. Owners faced the choice of sedating their pet or having it put to sleep for everyone's safety. A pair of Siamese cats, named Suli and Meru, became so accustomed to the air raids that they waited by their collar and leads whenever the siren sounded and were quite happy to camp out in their gas-proof boxes in the garden.

In 1944, the V1 flying bomb (Doodlebug) began to be used in air raids. Some cats learned to identify the distinctive sound of the engine and to associate it with the need to take cover. A blue-grey cat called Billy in Surrey learned to distinguish between a V1 and an ordinary aeroplane. If Billy heard a V1, he hid behind the fireplace. His family learned that Billy's actions occurred four minutes before the V1 flew over the house. The most famous feline early warning must have been the spontaneous mass exodus of cats out of Exeter, Devon in May 1942. That night the city was devastated by a bombing raid.

Working Cats

Animal lovers were appalled by the way the Government had created such a sense of panic and made it seem patriotic to kill much-loved pets. The Government relented in part, with its allowances for cat owners who relied on working cats to keep down mice and rats. They were considered to be cats engaged on "work of national importance" and entitled to a ration of powdered milk.

With so many cats culled or evacuated from cities, the number of rats and mice reached plague proportions. Some towns offered a reward to the owner whose cat killed the most rats.

CATS AND RATS (The Sketch, 1944) Even the lower animals cannot remain unaffected by the war, and strange things have been happening among them lately. Rats have been getting so far above themselves that we now have in Whitehall a Directorate of Infestation Control, and I should not be surprised if we soon had a Ministry of Pestology. On the other hand, cats are suffering grave hardships. It is partly their own fault, because, to judge by my own cat, nothing will reconcile them to war diet, and no class of the community is less co-operative in the war effort. But it is a little hard on cats that they should be kidnapped and turned into furs from plutocratic munition-workers. It is said that they go in peril of their lives, and I am glad to see that Our Dumb Friends League has taken up the cudgels for animals which deserve a better fate.

FEED THE MOUSERS (Birmingham Daily Gazette, 25th April 1944) Sir - One still sees a large number of hungry and sometimes homeless cats. We ought to realise how very important cats are to the war effort in keeping vermin in check. The damage done to food stocks by rats and mice is enormous, and would be far greater were it not for our cats. I do appeal to people to look after them properly; not only to save them the misery of the life of strays, but because it is also in the national interest. Incidentally, it is well to remember that a hungry cat is seldom a good mouser. Yours etc.. E. KEITH ROBINSON. Sec., Our Dumb Friends League Grosvenor Gardens House, Victoria, London, S.W.I.

CATS DO THEIR BIT (Britannia and Eve, 1st September 1942)

Cats do their bit principally as mousers and never were they more wanted owing to the large numbers of buildings and houses left untenanted through the blitz and because of backyard poultry and rabbit keeping. There is a great shortage of cats, and animal societies have a list of good hoes on their books. The progeny of plain howlers on the tiles is to be seen for sale in an exclusive West End pet shop austerity note! Casualties are from divers causes. Panicky owners left their cats to starve. As an example, London s stray cat population has increased to over 300,000. Our Dumb Friends League have dealt with 83,000. Many cats were from bombed areas, but they often stray because their owners do not feed them, it is a mistaken idea that cats find their own food. From where? One might well ask in these days. Casualties of another kind are due to cat thieves, who are rampant. Many a well-cared-for cat disappears, whose glossy coat attracts loiterers in touch with the bogus fur market. The thieves will be active again when the cats have grown their winter coats. The cat further does his (and her) bit as mascot, notably for sailors. Cats seldom miss their ships though Sallies may be enticed to spend a night on the quayside with a landlubbing Thomas. One airman took his cat on a 1,000-bomber raid Blackie has many hours flying to his credit. But the most famous cat of the war must be Oscar, erstwhile black and white pet of the Bismarck. Oscar was picked up by the destroyer Cossack, and later transferred to the Ark Royal. Again rescued from the sea when the aircraft carrier was sunk, he is now safely interned at a sailors rest home in Ulster.

An alternative to the slaughter was to give the pet, most often a dog, to the war effort e.g. to be trained as guard dogs or search dogs. Some cats were relocated to factories and warehouses to be ratters. The Ministry of Supply organised a special call-up for cats, recruiting them for a war on the rats and mice attracted to Britain's secret food warehouses. Patriotic Britons could now give up their cats to serve the war effort (which also meant less strain on the household budget). Pet shops became central collecting points and some shopkeepers in London reported cats arriving at the rate of a hundred each day. On pet shop owner in Camden Town reporting buying the cats for 2 - 5 shillings each and selling them to the Ministry of Supply at a profit.

Wartime Humour with a Feline Twist

Wartime often brings out a dark sense of humour in people, and this is a satirical piece about wartime reconstruction. It comes from the Daily Record, 7th April 1944:

At the request of the Home Office, the Ministry of Housing, the Inspectorate of Weights and Measures, the Institute of Architects, the Department of Reconstruction, Our Dumb Friends League, the Royal Academy of Taxidermy and the Ginger Group of the National Liberal Party, Professor (What a Man!) Dognose has invented a mechanical cat-swinger for checking living-space in small apartments. The device, of which simplicity is the keynote, consists of a stand or pedestal with metal rod, of statutory length, connected to the top by a swivel. The cat is attached to the free end of the rod and rotates round the pedestal when violently pushed. The cat is, of course, stuffed.

And this requisition for a working cat to protect an army clothing department supposedly fell foul of bureaucracy, when all that was needed was someone to go and acquire an abandoned cat. It appeared in The Tatler, 26th July 1939

'Anyone who has ever had anything to do with [Government] Departments doubtless recall what a long way round people have to go to get a straight answer to a simple question: the forms that have to be filled up and the references to divers precedents and suchlike that have got to be quoted in support or otherwise [. . .] A classic example of the Hampton Court maze method of Departments was an indent once submitted for Cat one. The circumstances were these. Mice were eating up soldiers trousers in an Army Clothing Department and were declining to succumb to the allurement of even the best cheese in the most p-to-date traps. So the O.C.-in.C. Soldiers Trousers thought of this cat.

He bussed in his indent to the appropriate authority in Q. and after some few months got a notification that his application had been duly receive, noted and passed to the D.D.Q.M.Q. (Supplies: Livestock). At the end of a few more moths the applicant sent in a gentle reminder (D.O.) which said: Dear Bill, what about that blasted cat? At the end of another month, the O.C. Soldiers Trousers got something almost exactly like this:

With reference to your O/22 B.N. and your D.O. (undated) I have the honour to request that you will state for information of U/S (a) colour; (b) age; (c ) sex of cat required; and at the same time submit estimates of (1) present numbers of mice engaged in attack upon raiment; and (2) number of mice cat is likely to kill and eat per diem. The U/S would direct particular attention to importance of (2), since it is gathered suggestion is that cat should be brought upon ration strength of unit concerned. '

Fancy Cats

Cat breeders preserved breeds by crossing them to locally available pedigree studs of other breeds. Siamese and Russian Blues were crossed, which changed the voice and the Russian Blue and introduced the colour-pointing gene; for years, some lines of Russian Blue had a tendency to produce blue-point, lilac-points and self lilac cats due to recessive genes (these may have been the source of "Peach Russians" that cropped up in the USA in the early 21st Century). Breeders hoped that any "damage" done to the breeds could be undone in later years. The alternative of course, was that both breeds would die. On the one hand, the outcrossing may have improved some gene pools, but on the other hand the loss of some breeding lines would have diminished gene pools. Breeders recorded the pedigrees of their cats on scraps of paper, ready to submit them to the GCCF once the war was over (I found one such pedigree scribbled in the fly-leaf of an old book). As had happened in the Great War, a number of influential cat fanciers, once active in running breed societies, would not return. Others gave up their breeding lines in the face of overwhelming adversity.

"At the present time, in spite of losses through war and the lack of shows, the interest in cats is greater than ever before in this country." - Grace Cox-Ife, Grace; "Questions Answered About Cats" (1947)

It was during this time that a strain of short-legged cats died out in England. In 1944, a dynasty of 4 generations of short-legged cats was documented in the Veterinary Record by Dr. H.E. Williams-Jones. Unfortunately, they were one of many established bloodlines that disappeared during World War II. The few that survived had been neutered. Reports of these short-legged cats being eaten by starving Britons are an exaggeration.

Hero Cats

Stories of feline heroes helped raise morale and inspire the civilian population. Some saved their owners and other survived bombings against the odds.

During 1942 in Malden an elderly cat called Jim alerted his owners, Mr & Mrs Coffey, when their house caught fire during the night. Jim was awarded the Blue Cross Medal. Jim was one of several cats that saved their owners in similar circumstances.

A 14 year old tomcat called Blackie, the pet of Miss L Darlisle, was warming himself on the sitting room hearth of his home in Surbiton when a German bomb came down the chimney. Half of the house was reduced to rubble, but three days later Blackie emerged from the rubble - minus one of his ears and hungry.

One London family were unable to find their cat when the air raid siren sounded. They left their shelter after the "All Clear" signal and discovered its tail in their garden. They were distraught at the loss of their pet during the air raid, but next day it turned up for breakfast, healthy except for the loss of its tail.

A tabby cat called Tommy, who lived at the home of a London solicitor, leapt out of a shattered window when the house opposite was hit by a bomb. The windows of his home were boarded up until 1948. Three days after the boards were removed, Tommy returned home. Snowy in Ashford, Kent, lived in the rubble of his old home for four years after it was bombed and his mistress killed. He refused to be taken in by neighbours, so they built him a kennel and fed him in the remains of his old home.

A tabby-and-white cat called Andrew became the mascot of the Allied Forces Mascot Club formed by the PDSA in 1943. The club commemorated all the animals and birds that served with the Allied Forces or Civil Defence services during the Second World War. Andrew's contribution to the war was to know in advance when a flying bomb was going to fall nearby; when Andrew took cover, everyone around heeded the cat's warning. Cats have superior high-frequency hearing to humans and other family cats also detected the sound of those flying bombs, warning their owners well in advance by taking cover.

MOTHER LOVE. In the London area women officials of Our Dumb Friends League have rescued 1,482 animals. These women enter dangerous buildings at their own risk to reach dogs or cats imprisoned under debris. In one bombed site a cat was dug out still protecting her kittens and in another place a dog had carried her puppies under a table and in this safe shelter they were found in the midst of the ruins. ( Portsmouth Evening News, 27th July 1944)

The best known civilian cat hero is church cat Faith.

In 1936, a friendly stray made her home at St Augustine's Church in London's Watling Street. Father Henry Ross named her "Faith" and she became the church cat, keeping the mice under control. Most of the time she lived upstairs in the vicarage. In August 1940, Faith gave birth to a black-and-white male kitten named Panda. On September 6th, while Ross was at his desk, Faith made it clear that she wanted to go down to the basement so he opened the door for her and later spotted her moving Panda downstairs. Thinking the new den to be too cold, Ross moved Panda back upstairs - only for Faith to move the kitten back downstairs. This happened twice more so Ross moved Faith's basket into the basement. Unusually, Faith did not join him as usual at the church services that day.

The following night, September 7th, saw the start of devastating air raids on the city. On September 9th, Ross was returning to St Augustine's from Westminster when the air-raid sirens sounded. He spent the night in an air-raid shelter and when he emerged, he learnt that St Augustine's Church had been destroyed. Ross wanted to search for Faith and Panda, but a fireman told him the cats could not possibly have survived and warned him to stay out of the unstable remains. Ross continued to call Faith's name and was rewarded by a faint answering miaow from beneath the smoking timbers. When he reached the basement, he found the cats dirty, but unharmed, with Faith nursing her kitten and "singing such a song of praise and thanksgiving as I had never heard." Faith and Panda were temporarily relocated to the verger's house until they could safely return to the church tower. Faith resumed her place at Ross's feet during services. Ross had a photo of Faith placed on the chapel wall with the accompanying text: