MAJOR SOURCES:

Cats Protection League (various leaflets from 1960s & 1970s)

Mery, Fernand; "The Life, History and Magic of the Cat" (1966) (originally published in French)

Pedigree Petfoods/Peter Way Ltd; "Your Guide to Cats & Kittens" (1973)

INTRODUCTION

Earlier parts in this series focussed mainly on the 1940s and 1950s, touching upon later decades to show how attitudes were evolving. This article focuses on the 1960s and 1970s onwards; there was more information available although some misconceptions remained. Feline health and diet were being scientifically studied and new breeds were appearing. For me, the 1970s are not "history"; I grew up during this time. Major sources for this period were the English translation of Mery's "The Life, History and Magic of the Cat", pedigree Petfood's "Your Guide to Cats & Kittens" and literature produced by the then Slough-based Cats Protection League (CPL). Concerned with welfare, rehoming and population control rather than breeds, breeding or exhibiting, the CPL produced and distributed leaflets such as "Some Facts About Cats". Additional information is sourced from CPL member magazines of the time.

Annotated excerpts from “PUREBRED OR HYBRID?” by Ann Manley, Cats Magazine, April 1960. This looked at the thorny issue of registering by phenotype (appearance) or genotype (pure ancestry).

The question of purebreeding is a difficult one. We do know that in Longhairs and in Siamese in [the USA] there are strains that have been registered for ten, twenty, and more generations. In the same breeds, we do find FR (Foundation Record) registrations, although they are more common in Siamese than in Longhairs [the term for Persian, the only recognised longhaired breed at that time]. Some associations do not clearly label the kind of registration awarded by a particular numbering system but they do differentiate between cats with a clearly traceable back-ground and those without.

Until a few years ago, all breeds were naturally occurring and there was not much question of recognition of hybrids [meaning cross-breeds, not wild-domestic hybrids] by the cat fancy. It was known that LH cats with Siamese coloring could be produced but there was no great demand for recognition. Red pointed Shorthairs have been known for about eight years and they finally broke the ice with recognition in several associations. Now, although the associations claim to maintain their registers and stud books for cats of purebreeding, they do register hybrids.

Still, in this country, we differentiate between purebred colors and breeds and those that are acknowledged hybrids. To many of us, the differentiation is of extreme importance. The difficulty of which most of us are not aware is that in England the GCCF (Governing Council of the Cat Fancy) does not differentiate between purebreds and hybrids [cross-breeds]. They register each cat by outward appearance [phenotype] and assign it a "breed number” to indicate what it appears to be. In the long run, this extreme honesty means that the background of each cat is clearly indicated for all to see. Now most people who have imported Siamese from England understand that 24 is the Siamese breed number. 24 alone is for Seal Points, 24a is for Blue Points, 24b is for Chocolate Points, and 24c must indicate Frost Points. The Longhairs have numbers 1 through 13a. Shorthair cats have 14 through 29. Note that the Longhair numbers include 13a, Any Other Color. The Shorthairs have 26 for Any Other Variety. Burmese were held in this classification until they were given their own number, 27. Chestnut Browns or Havanas were known as breed 26 before being assigned 29. Domestics have numbers 13 through 22 plus 28 but Russian Blues are 16a while 16 is British Blue (or Domestic). It is also interesting to note that there is no provision for a solid Red Domestic Shorthair [this is because all self/solid red cats manifest a degree of tabby pattern even if genotypically solid colour].

For anyone buying imported stock or importing a cat from England, a full under-standing of these numbers is vital. There are cases of hybrids sent to this country as purebred cats. One case shows the inclusion in an otherwise pure Siamese pedigree of cats with the breed number of 15—Black Domestic Shorthairs. These cats, Laurentide Ephone Jet and Laurentide Ephone Ebony, were the offspring of a Russian Blue male and a Seal Point Siamese queen. Jet, one of these black cats, appears in the pedigrees of some of the new brown cats—the Havanas or Chestnut Browns. In the Brown pedigrees, the black cat is the dam of a female with the breed number of 16a or Russian Blue. The sire of the 16a cat is a 24b Chocolate Point Siamese. In fact, that son of crossing is the basis for the very lovely and very different Havanas which are a man-made breed. This breed combines a solid color factor from the Russian Blue with the rich warm brown tone of the best Chocolate Point Siamese.

In many of the best Abyssinian pedigrees, if one cares to trace back far enough, one finds "Mr. Brooke’s Self Red”. A solid red cat is called "self red” in England. The son of "Mr. Brooke’s Self Red”, "Tim The Harvester”, is behind some of the Woodrooffe Abys, also some of the Croham and Raby Abys, namely Raby Ashanto and Raby Ramphis; hence most of the current Abys in this country and probably most of those in England, too. The difference, of course, is that the self red was introduced into the Abyssinians in England when the breed was young and new, probably with a specific purpose or even a strong need to perpetuate the breed. [Even more interesting is the fact that an African Wildcat seemed to end up in the breed, as did “Indian Cats.”]

It is interesting to note that the first Frosts [lilac/lavender point] in England came from the line with the Russian Blue cross. Most of the breeders were so strongly opposed to mating Blue Points with Chocolate Points that they couldn’t or wouldn’t advance another step to mate cats with both the chocolate and blue genes to produce Frosts. It took a person actively experimenting to come up with Frosts from a less likely source.

From the foregoing, it is easy to see that the point of view of some of the English fanciers differs greatly from that of the Americans. Of course, there are many breeders in England who insist on keeping their strains purebred.

I hope breeders everywhere will understand that there is no criticism of the breeding implied in this article. I personally would prefer to have the Siamese strain kept free of hybrid influences but I can see no objection to using Siamese to produce new breeds by hybridization with other breeds. I have recently enjoyed seeing and handling several of the new Brown cats as part of a committee assigned the task of investigating them thoroughly for presentation of a report to the September 1959 Annual Meeting of the United Cat Federation. I found them to be a very attractive breed entirely different from Burmese, Domestics, Siamese or any other breed. The important point is that every breeder, even every exhibitor, should be thoroughly familiar with the background and pedigree of his or her own stock and with that of any strain he or she might contemplate using. It seems a matter of public service to call attention to the GCCF breed numbers and their use in registration of purebreds and hybrids in England. The source of my information is the Stud Book, List of Cats at Stud and various other publications of the GCCF.

Excerpts from “NEW BREEDING POSSIBILITIES” by Blanche W. Smith in CATS Magazine, September 1961

In every profession there are always the explorers who are seeking new worlds to conquer, and fortunately (for they add much interest to the Fancy) we in the cat world have them too. I’m speaking of those who are not satisfied just to breed a regular kind of cat whose type and other characteristics are all laid out in the rule book. No, these people want to invent new breeds of cats, new colors of cats, and new sizes of cats. All, so they say, in the name of progress. They study the few and woefully inadequate and confusing books on cat genetics; their libraries of stud books and pedigrees are larger than their catteries; all the country round is filled with half-breed cats which they’ve given away to friends and neighbors — but still they go on mixing, blending, purifying, adding a bit of this and taking away a bit of that until, if Bast smiles on them, up comes a true breeding cat of color and kind never seen before.

This latter-day alchemist is fortunate in that the cat world climate today encourages his activities. During the years prior to 1950, few indeed were the breeds and colors added to the standards as imported from England at the turn of the century. The Persian-Siamese originated by Virginia Cobb and others in the 1920’s could not secure recognition. Yet its close relative, the Himalayan developed by Marguerita Goforth, gained prompt acceptance after its appearance in 1958. More recently the Blue Tabby as bred by Jane Martinke and the Cameo of Dr. Rachel Salisbury have joined the Longhair colors, and early in the decade a group of White breeders succeeded in gaining complete recognition for the Odd-Eyed White. In Shorthairs the story is similar. Prior to 1953 only the so-called "natural” breeds and colors — the Blue Point and Seal Point Siamese, the Russian Blue, the Abyssinian, the Manx, the Domestic, and (after a hard battle) the Burmese — had been recognized. Then Alyce DeFillipo produced her Red Point Siamese at just about the time the Chocolates and Lilacs (or Frosts) were being distinguished as separate Siamese colors. The Rex appeared in England, and from a series of involved breedings out came the Havana Brown.

If I were a bit younger and had a little more room and fewer duties in the car world, I’d be tempted myself to try to develop a Gold- Eyed Brown Persian. The blueprint for such a cat was published in the May and June 1956 article by James D. McCrae. More recently a Brown Longhair kitten appeared in a litter bred by Mae Fleming, and others occur from time to time. There is no question but that the Brown Longhair will be a worthwhile addition to the Persian breed, but because of the work yet involved, I feel that it will probably be two or three years before it is ready for recognition.

I’ve noticed, too, that there is increasing agitation for recognition of Peke-Faced classes in all colors of cats instead of just the Reds and Red Tabbies. Here I am not so confident that this is a good thing, nor that it will win out. The true Peke-Face characteristic seems to be tied to the Red gene, and it may be impossible to fix it in other colors beyond one or two gene-rations of the cross to the Red Peke. Another possibility which has not yet been worked out even in theory, but which I find quite absorbing is the thought of a true curly-haired Persian. Some breeders have already reported the "Rex” mutation in their Longhairs—but as something to be bred out. Perhaps the next time it appears the fancier will be inspired to breed for this feature with the result: a charming White or Blue with a poodle-type hairdo.

The Siamese colors, of course, are now running the full scale from Black Point to Tortie Point, but I wonder if it would not be possible to fix as a breed the beautiful anomoly which sometimes occurs from a Siamese-Domestic cross: a Blue-Eyed Black Shorthair with the type and coat texture of the Siamese. I have seen these animals only rarely—once in the Household Pet class at a show—and I am always haunted by their beauty. The newest Siamese color is the Albino — recently given tentative approval by UCF. In theory, at least, albinos should appear in all breeds, and technically there is no reason why they should not be recognized if true-breeding strains are isolated, although my own position would be one of some hesitation. Non-pigmentation sometimes carries with it other deficiencies, and it may not always be in the interest of the Fancy to perpetuate such abnormalities.

Occasionally one hears of experiments involving the Manx and the Siamese or Persians. Here, I think we are treading on dangerous ground both esthetically and physically. As we know, there is always the lethal factor present in any Manx line. I do not think it wise to extend this to other breeds, nor can I picture an artistically satisfying tailless cat other than the Manx as it now exists.

I see no reason, however, why the Maine Coon cat which seems to have elements of the Angora and Domestic, plus possibly the bobcat, should not be admitted into the society of purebred cats if its sponsors can prove the existence of a pure strain. And perhaps there are unexplored possibilities in a Domestic-Bobcat cross. N.P. Kenoyer in Cats for April I960 reported the proof that such crosses can occur, and perhaps some brave soul will wish to follow through on what new brands of pussy cats such continued crosses could bring out [Kenoyer was mistaken, the cats were bobtailed domestic cats as demonstrated by their recessive classic tabby pattern and the fertility of the male offspring].

In England crossing between breeds does not seem to carry the stigma that most of us place upon it here. Russian Blues and Siamese are apparently crossed over there and their offspring registered without objection, solely in accordance with their appearance. Perhaps that is why the Havana Brown and the most recent Colourpoint (our Himalayan) first appeared there, and it may have been their acceptance in England which paved the way for them here.

We have many new projects of our own going, however, and to me the most promising of all is miniaturization. I recently judged a show in which there were full- grown Siamese small enough to hold in the pocket of my smock. Other breeders have reported simiarly small full- grown Persians. The miniature gene seems to exist in almost all mammals, even humans, and it is not unnatural for it to make its appearance in cats from time to time. By inbreeding, a true strain of half size or smaller midget cats can result. Much the same thing has already taken place in the dog world, and I can think of nothing which would add more to the interest of a show as far as spectators are concerned than to find tiny, but perfect, Persians and other breeds caged next to their full-sized brothers. My own vision, right now is of a tiny Blue-Eyed White Persian in exact miniature duplication of those of such fine type which are winning today. Can you think of anything which would be more beautiful and more lovable?

The climate of the cat world has changed greatly in the past decade. New breeds are welcomed, and the adventurer is encouraged to explore ever further into the unknown. The next ten years will see all the developments I’ve mentioned, but the most exciting thing is the knowledge that there’ll be many more which we can not even picture today. It’s fun to try to anticipate what will happen, but all we can be sure of is that those of us who are breeding ten years from now will find a world as different from today as ours is from 1950.

MERY ON THE VARIOUS CAT BREEDS OF THE 1960s

"The Life, History and Magic of the Cat" describes the limited number of breeds available in Europe at that time. Mery clearly disapproved of some British breeding practices and he omitted the newer American breeds altogether! Newcomers of the 1960s omitted by Mery were the Scottish Fold, Cymric, Somali, Korat, Tonkinese ("Golden Siamese"), Bombay, Egyptian Mau, Ocicat and Ragdoll and the Oriental White/White Siamese (which was much publicised in 1965). The Turkish Van (recognised 1955) and Norwegian Forest Cat (bred in a minor way since the 1930s).

MERY ON THE LONGHAIR CAT BREEDS OF THE 1960s

Mery disapproved of the evolution of the silky-coated, longer-faced Angora (which he regarded as being largely French) into the thick-set, wide-skulled, short-nosed Persian, considering this a reflection of the English love of fat chunky creatures! He also blamed the change on a high-protein diet and the British cold, damp climate. He described the Longhair (Persian) as having an "almost non-existent nose" and added: "In the United States a shortening of the face even more than is normal for the long-haired face, giving a really Pekinese-like look, has resulted in a special group being formed within this breed for show purposes [...] It is the striving after sensational effects in breeding that produces those Persians that are just flabby balls of fur, with cheeks invading their eyes, colour that is washed out and legs that are bandy or too furry."

Mery felt Smoke Longhairs and Tabby Longhairs to be on the wane and deteriorating in type and was dismissive of the Chinchilla, noting that the United States and the Commonwealth countries recognised two breeds (Chinchilla and Shaded Silver) where Britain recognised only the more lightly tipped Chinchilla. Chinchillas and Long-haired Tabbies were less ultra-typed than the self Persians and Mery considered they would "more correctly be called Angoras".

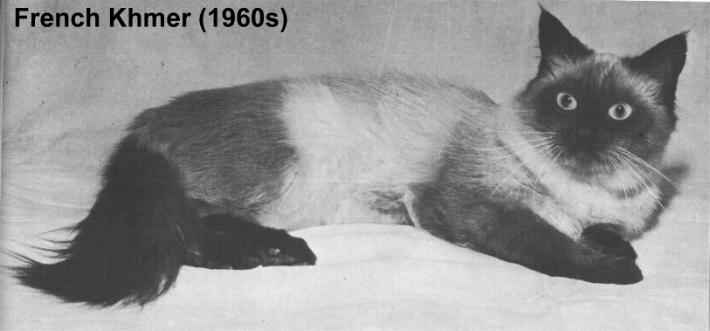

Mery considered the "Colourpoint" Longhair to be remarkably like the French Khmer breed, which had a breed standard in France, but was not recognised by FIFe. The term "Khmer" had officially been dropped in 1955 - eleven years before his book - and the French Khmer more closely resembled a semi-longhaired Colourpoint British Shorthair rather than a colourpointed Persians (Himalayans).

Mery considered the "Colourpoint" Longhair to be remarkably like the French Khmer breed, which had a breed standard in France, but was not recognised by FIFe. The term "Khmer" had officially been dropped in 1955 - eleven years before his book - and the French Khmer more closely resembled a semi-longhaired Colourpoint British Shorthair rather than a colourpointed Persians (Himalayans).

He disapproved of tortoiseshell Longhairs because they did not breed true and there were no tortoiseshell males, necessitating in cross-breeding the females with other colours, making the breed "unstable": "its coat is merely a mixture of two colours rather than showing a genetically pure colouring." However, his views on genetically impure breeds (tortoiseshells) came a little unstuck with the Longhaired Red Self (Red Persian): "Although there are official standards for it in England it may almost be said that no true Red Selfs have been achieved by English breeders. ... However it is certainly possible to hope that ... there will be success in producing and fixing this pure red breed of cat, whose red colouring must certainly have existed originally as a self-coloured coat (in the same way as whites, blacks and blues), but has not persisted."

Red cannot exist as a "pure" colour since the non-agouti gene (which turns a tabby cat into a self cat) does not work on orange pigment. Breeders can dissipate the tabby pattern by selective breeding, but cannot eradicate. Mery suggested that the introduction of genes from Abyssinian cats might go further towards producing red self longhairs - an interesting point which has never been taken up by breeders.

MERY ON THE SHORTHAIR CAT BREEDS OF THE 1960s

Mery wrote of the French Chartreux breed with obvious pride, stating that it was not to be confused with the British Blue, being stockier with woollier fur. "The Chartreux is a cat of rural France. [...] It has a very powerful jaw, temptingly reminiscent of that of the European wild cat. [...] Its colour can be any shade of greyish blue, though the preference is for the paler colours." Even today the Chartreux is not recognised in the UK, being considered too similar to the British Blue Shorthair.

Meanwhile, the British Shorthairs of the 1960s had been developed from ordinary domestic shorthairs into chunky cats, almost shorthaired equivalent of the Persian. The Exotic Shorthair, the true shorthaired Persian and a newcomer in the 1960s, was not mentioned by Mery. Conceived as a breed to "make saints out of sinners," the Exotic Shorthair was quietly envisioned as a dumping ground for the hybridized Silver American Shorthair which was becoming too cobby in conformation. Some breeders believed that the Exotic Shorthair breed would be shortlived and would ultimately be discarded, taking with it the re-registered hybrid American Shorthairs. Contrary to official Cat Fancier Association minutes, it was Lee Carnahan who rescued the new breed from demise and, much to everyone's surprise, the Exotic Shorthair attracted interest in its own right and took off. Among the general public, it appealed to those who liked the Persian shape and temperament, but did not want to groom a lognhaired cat every day.

In discussing the Manx, its origins and the variation in tail type from no tail through to partial tails, he confuses it with the bobtailed cats of Asia such as the Siamese with truncated or atrophied tails, the tailless cats of the Malay Archipelago and Japan (as seen in paintings). The Japanese Bobtail, which Mery only seemed to know from Japanese art, is a separate mutation and was "discovered" (by Americans) in 1963, but not developed as a breed until 1968.

Mery describes the Zibeline (Burmese) as a newcomer and " [...] Burmese, in whose artificial creation the Siamese played a part." What Mery didn't realise was that the Burmese is, in fact, the far end of a continuum of cat breeds with the Tonkinese in the middle and the Siamese at the other extreme. European Burmese are more foreign in type than their American equivalents, giving a better impression of their relationship to the older type Siamese. The Siamese was not then so ultra-typed, retaining the traditional appleheaded look and heavier build; this look was revived in France in the 1990s under the name Thai Siamese.

He lamented that the scarcity of Abyssinians in Britain had led to cross-breeding which had introduced tabby markings "such as bars on the legs or even ringing of the tail" into the breed. "They are unfortunately the most susceptible of all breeds to disease." Not noted by Mery is that the Abyssinian's susceptibility to disease was probably linked to inbreeding in the 1940s/1950s when the "British Ticked" (a variety of British Shorthair) was selectively bred into the smaller, more delicate Abyssinian type, though the residual markings were difficult to eradicate. Once again, in modern times there are so-called traditional type Abyssinians, plus the Singaporean "Wild Abyssinian", all are bred to exhibit those features which Mery found lamentable!

MERY ON EXTRAVAGENT EXPERIMENTS IN THE 1960s

Pedigree cat breeding for exhibition has been going on since the end of the 19th Century. Mery called this "the scientific breeding of cats" which had been brought about by human curiosity leading to original natural breeds being crossed to create new breeds. Though aware of wild/domestic hybrids, he considered these fragile, delicate, short-lived and generally infertile. In his opinion, the domestic cat could not successfully interbreed with the European wild cat (F silvestris). As it turns out, the Scottish Wildcat (F silvestris grampia) is being gradually supplanted by more vigourous, faster breeding Wildcat/Domestic hybrids whose fertility and vigour had been documented as far back as 1896 (Edward Hamilton) and again in 1939 (Frances Pitt)

He seemed unaware of the Asian Leopard Cat/Domestic hybrids bred in the 1960s by Jean Sugden, and wrote instead about Dutch breeder Mme Falken-Rohrle who crossed Abyssinian cats with both Margays (F wiedi) and Little Spotted Cats (F tigrina, oncilla). By all accounts Falken-Rohrle's experiments had limited success while the Asian Leopard Cat experiments eventually resulted in the Bengal breed. Mery was also unaware that Maria Falken-Rohrle was using a "Sudanesian Desert Cat" (F silvestris rubida i.e. F lybica) as a foundation queen for her Oriental breed (van Mariendaal cattery). The alert character of the wild cat was inherited by the descendants.

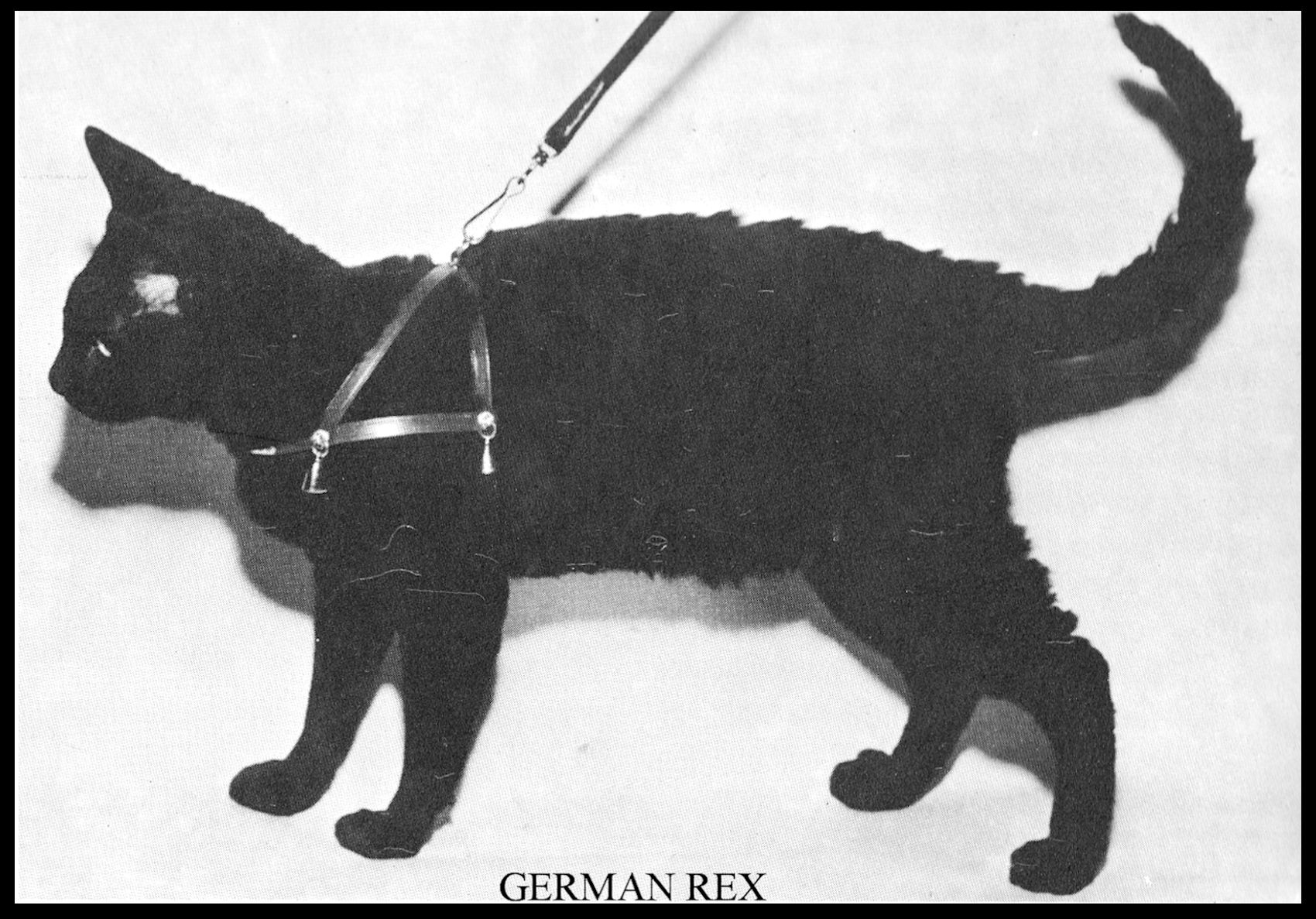

In the 1960s, hairless and Rex breeds were novelties. Mery writes, "Two extravagant experiments in breeding have produced the bald cat on the one hand, and the curly-haired Rex on the other." The bald cats of France were described as "Sensitive to cold, thin, unaesthetic and not much admired by cat-lovers, these bald cats have only a technical interest. They are a flirtation for the specialist. The mutations has been fixed, but the breeding of bald cats hardly seems to have a great future." The hairless cats born in Ontario, Canada in the 1960s did not survive as a breed, but when the mutation reappeared in the 1980s, they were crossed with Devon Rexes, to produce the Sphynx.

Of the Rex, or "poodle cat", he wrote "These have been artificially bred and are still rare. There seem to be two types of coats according to the body type of the cat. Those with a foreign type have thinner but more curly coats. Where the type is like that of the British Shorthaired cat the coat is thicker and wavy. But Rex hair can be introduced into any breed including Persians. The kittens are born with curly hair from the start." (Perhaps there had been some crossings of Rex with Persians, this might account for some of the curly-haired Persians which have cropped up mfrom time to time)

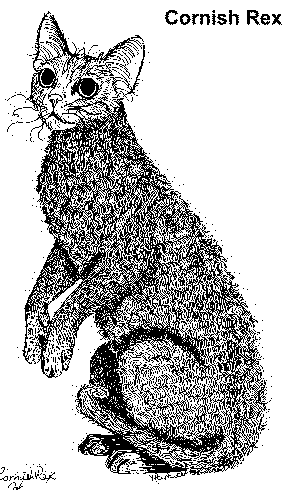

The difference between the two Rex types (Cornish/German and Devon) was poorly understood. The German Rex (European Shorthair conformation, thicker wavy coats) appeared in 1946 but was not bred until 1951, the Cornish Rex (same mutation) appeared round 1950 and the Devon Rex (Mery's "foreign" type with thinner curlier coats) appeared around 1960. The American Wirehair appeared on the scene in 1966, too late for inclusion.

PEDIGREE PETFOODS ON THE DIFFERENT CAT BREEDS OF THE 1970s

According to "Your Guide to Cats & Kittens", by 1973 there were over 70 different breeds (elsewhere it states 50 breeds) though this number was artificially inflated by the rather peculiar 19th century British system of classifying each colour variety as an individual breed.

"The word ‘pedigree’ is often used to describe pure members of the various cat breeds, and it is the cause of much confusion. A pedigree cat, whatever its breed, is simply one that has a known ancestry which can be traced and which has been recorded over several generations." Hence any cat can have a pedigree - meaning that its family tree is known - but it might not be a purebred or be a recognised breed. This was especially true with experimental varieties where the parents were from different breeds, had full pedigrees but the offspring could not be called purebreds until several generations had been bred.

The book divided the breeds into Longhairs and Shorthairs and included notes on breeds only recognised in the USA (much as Mery had devoted a section to extravagant breeding experiments). Most of the breeds and their descriptions are familiar today, so only snippets are included here to illustrate changes since the 1950s and 1960s and to provide a contrast to Mery's opinions. The Longhairs of the day were the traditional style of Persian i.e. not the present day pug-faced look. American breeds were also reaching British shores and breeds Mery which had considered extravagant were becoming established on the show-bench. Intriguingly, the temperament of a particular colour variety is described, often in fanciful terms.

PEDIGREE PETFOODS ON LONGHAIR CAT BREEDS OF THE 1970s

Originally, White Persians had blue eyes inherited from Angora ancestors. To improve the conformation, they were bred to Blues and Blacks and this had the side-effect of introducing orange eyes into White Persian breed. White longhairs were now recognised and exhibited in blue-eyed and orange-eyed varieties; odd-eyed whites were recognised but were not eligible for competition. "The Blue-eyed [White] Persian has dignity. It is solemn, and is playful only after serious thought. Afterwards, it will retire to contemplate its frivolity [...]. Whilst a Blue-eyed male may be an ardent lover, its affections towards humans are restrained. The Orange-eyed cats, however, have cheerful, out-going personalities."

In temperament, Red Tabbies [Persians] were said to be intelligent and active. "They make very amusing companions, but need affection to bring out their best qualities. [...] Contrary to a commonly held belief, they are not spiteful. The males can look forbidding, but this is due more often to apprehension rather than anger." (the look is due to facial markings rather than temperament!) The Cream Longhair was said to have a most affectionate sweet-tempered nature and to make a delightful pet. "The cats usually tend to avoid trouble but are quite capable of standing up for themselves if they have to" while the Red Self was described as a Longhair of tremendous character, and which very soon became ‘top cat’ in any cattery. "Females are rare, while the males are often great fighters. Yet, when it suits them, Red Selfs can be most affectionate. They are usually self-possessed and interested in everything going on around them."

The [Black] Smoke Longhair, one of the earliest recognised breeds, was described as "an unusual cat with striking contrasts of silver and black. A jet black face is framed with a silver ruff. The black top body coat is laid over a pure silver undercoat; and the cat has black legs like stockings". Blue Smokes were also known and Smokes were said to have "even temperaments and are gentle and affectionate. They will fight, but they are rarely aggressive and are generally glad to call the battle off if honour can be preserved." The Chinchilla had long been recognised and was noted for its habit of changing colour in the summer when its black ticking would be bleached to brown. Several breeders were producing Blue Chinchillas, but these were not then recognised.

Outside of a cat show, the most likely place to see a Tortoiseshell-and-White Longhair was apparently on a farm since it was "from farm stock that the first pedigree cats of this breed came into being". They were one of the oldest established breeds and known in the USA as calicos. As with the Tortoiseshell Longhair, the tortie-and-white was an all-female breed. They were described as very clean cats and full of character. The Blue-Tortoiseshell-and-White was not then recognised by the Governing Council of the Cat Fancy and could only compete as ‘Any Other Variety’. The Tortoiseshell Longhair was described as having a pansy-shaped face! The Blue-Cream Longhair - known in the US as the Blue Tortoiseshell - were originally unpopular and regarded as inferior to either pure Blues or pure Creams. They had improved over the years and were achieving the brindled look favoured in the UK, so that they were rapidly gaining favour. Blue-Creams were described as very feminine characters, being good if somewhat detached mothers, and being more interested in birds or, particularly, in tomcats! This was the popular image of the flirtatious "tortie tart"!

In 1972, Silver Tabby Longhairs were considered one of the rarities of the cat world, and always drew a crown when exhibited. They were said to make good pets and had "the calm tranquillity common to British breeds of cats, and when on show display an aristocratic dignity which makes it quite plain that acclaim is an essential part of their lives." Like all Tabby Longhairs, the Brown Tabby was uncommon. Their popularity was increasing. They were one of the oldest recognised varieties and were considered quiet, courteous, docile and faithful, but at the same time were hardy and courageous! The recognised Bicolour Longhairs were red-and-white, black-and-white, blue-and-white and cream-and-white. Black-and-whites only got official recognition in 1966. Bicolours were apparently excellent ratters and mousers!

The Colourpoint Longhair, considered an awful experiment by writers of earlier decades, was recognised in 1956. They were bred in seal-, blue-, chocolate- and lilac-point. 1970 saw the first magnificent red- and tortie-points. "Colourpoints have friendly dispositions, are very affectionate and easy to train and, unlike the Siamese, with whom they share no genetic relation, have very quiet voices." They were said to be very hardy and could be outside all the year round with no ill effects. It was interesting that the authors considered them to be unrelated to Siamese cats; the section went on to say, "Some people still refer to the Colourpoint as a ‘Long-haired Siamese’, but this description is quite wrong. Colourpoints are Persian cats, and they resemble the Siamese only in coat pattern. [...] In America, a cat arose which was similar to the Colourpoint but called a Himalayan. Worldwide, however, the British breeds are thought of as superior, and there is a continuous demand for them from the United States and other countries."

There is no mention of Mery's Khmer, but another colourpointed longhair was the Birman: "The Birman breed has been recognised in France (where it is spelled Burman) since 1925, but it did not reach Britain until 1966. For a prospective pet owner attracted by Longhaired breeds but unable to cope with the extra long hair of a Persian, the Birman would be an excellent choice." Another relative newcomer was the famous swimming Turkish (Van) Cat which arrived in England in 1955 and officially recognised in1969.

Two new and unrecognised self Longhairs were the Chocolate Longhair and the Lilac Longhair and arose as the self-coloured forms of the then new Chocolate and Lilac Colourpoint Longhairs. "Temperamentally, these self are fearless and will jump on strangers’ laps without waiting to be introduced. Displaying dog-like devotion to their owners, the male cats are probably a better choice as pets than the females. Unquarrelsome, two Selfs - even of the same sex - will be prepared to share feeding dishes and sleeping places without falling out."

PEDIGREE PETFOODS ON SHORTHAIR CAT BREEDS OF THE 1970s

White Shorthairs were uncommon and unpopular because their coats were thought to be difficult to keep clean and also because they were thought to be unlucky Rarest of these were the Blue-Eyed Whites which was considered to be in danger of extinction. Most common was the Orange-Eyed White, and there were also Odd-Eyed Whites. The Blue-Eyed White and some of the Odd-Eyed cats were frequently deaf: "Often, these deaf cats lie with their heads over the edge of a table or lie on the floor with their chins tucked in and their foreheads resting flat on the ground"

Black Shorthairs looked awesome in the show pen, but at home were said to display a clown-like delight in "entertaining its owner with gymnastic tricks and enthusiastic affection". "In Europe, the British Black is called the Black European Shorthair [...] In America, however, it is classed as ‘domestic’ and interbreeding with pedigree cats is discouraged. United States’ breeders are, however, striving for recognition for the Black and are trying to improve their stock by importing from the best in Britain."

Russian Blues were not numerically common in Britain, though the British Blue was. "In France, a variety similar to the British Blue has been bred and is called the Chartreux. These cats arc thought to have originated from animals brought to France by the Chartreux monks of South Africa." The Cream Shorthair was an old-established breed, but was rare in the 1970s. During the 1930s and 1940s, it was only the efforts of dedicated breeders that had saved the Cream Shorthairs from extinction. The term "black-and-white kitchen cat" was used to describe non-pedigree bicolour cats, the sort known in the USA as "tuxedo cats". Though various colours of Bicolour Shorthair, had appeared in cat shows at the end of the 19th century, it was not until 1966 that they were officially recognised.

The Brown Tabby Shorthair was described as the traditional British hearthside cat. The Red Tabby Shorthair was also common: "‘Ginger’ or, more correctly, Red Tabby cats are not all toms. Nor are ginger females prized varieties" Red Tabbies were described as quiet, docile and affectionate; but unlike its kitchen cousins, an exhibition Red Tabby Shorthair had dense, dark red markings. Red Tabbies in general were among the most popular pets and apparently favoured by men, perhaps because these cats were such excellent ratters and mousers. "Many of the sand-coloured cats kept to catch rodents are not, however, true Red Tabbies." A relative of the tabbies, the Spotted British Shorthairs were apparently good travellers and took well to a collar and lead. Though not officially recognised as a breed, Short-haired Smokes were exhibited at cat shows. Black Smokes and Blue Smokes were both seen. Mated to Silver Tabbies, they produced Silver Tabbies and Spotteds.

The Silver Tabby Shorthair was said to be shy but extremely affectionate, and very dependent upon human contact. Though hardy pets, the females apparently did not thrive in cattery conditions and the kittens need to be house-reared. During the years following the Second World War, the Shorthaired Silver Tabbies had been in danger of dying out. In 1953, the last of a famous French strain - a cat named Calchas d’Acheux was imported to Britain and the breed was enthusiastically revived.

The Tortoiseshell was one of the oldest British Shorthairs and were originally the products of farmyard cats. They were considered affectionate, loyal and excellent mousers. Tortoiseshell-and-White Shorthairs (calicos in the USA) were also derived from farmyard cats and had a distinguished history as rat catchers. Blue-Cream Shorthairs were, worldwide, a comparatively rare breed. They first appeared on the show bench in the early 1950s, and gained official recognition in 1958; considered affectionate, some apparently had the interesting and endearing habit of scooping up food with their paws! The Blue Tortie-and-White was not officially recognised competed as ‘Any Other Variety’.

"Although the Isle of Man is usually credited as the homeland of the Manx cat [...] tailless cuts can be found in other parts of the world, including Russia and China." Once more confused the Manx mutation with the Bobtailed mutation. "Manx matings conducted over a long period tend to cause still-birth or early death of the kittens." (though not stated, this is because inbreeding meant that cats with two copies of the gene had severe defects). Manxes were described as puppy-like in their devotion to owners and having fast, "Manx hopping, rabbit-like gaits". They were considered excellent hunters and climbing (and descending backwards) was one of their strong points and they found 6 ft wire fences no obstacle.

The Scottish Fold had appeared in 1961. The book reassured readers that the folded ear did not affect the cat's hearing (the problems with hind-legs and tail were not then known). They could be shown as "Any Other Variety", but had not gained breed recognition.

The Cornish and Devon Rexes were, by then, familiar. The Cornish Rex had a deeply waved "corrugated" coat while the Devon Rex had a shorter, crisper one. Of the Cornish Rex, we are told "Their predictable natures, intelligence and easy training - combined with a very individual character - make them ideal but ‘different’ pets." Meanwhile, Devon Rexes were said to have a definite sense of humour and were natural clowns, appearing to play to amuse their owners as much as to amuse themselves. "Some of the very early Devons (different from those of today) were bred with very scanty coats. As kittens, with wrinkled faces annd enormous, hair-covered ears on near-naked necks, and with furry, chubby legs supporting tiny, hare bodies, these animals had sonic appeal. But when they grew tip into unhappy grotesque creatures perpetually huddled by radiators or crouched on hot-water bottles. they lost their attraction. For man, one of the beauties of the eat is the sensual pleasure of stroking its fur: but stroking these almost hairless Devons was more like touching a warm suet pudding." Luckily, breeders eliminated that feature.

The Siamese cats were well known. Children were familiar with "Jason" the seal-point Siamese who featured on TV's Blue Peter show twice each week. As well as the traditional Seal-point, Siamese were now accepted in other colours. Chocolate-pointed Siamese had arrived in Britain in the 1880s, along with the Seal-points, but were originally thought of as low-quality Seal-points. Blue-pointed Siamese first appeared in Britain in 1894 and were considered less independent than Seal-points. Lilac-pointed Siamese struggled for recognition, achieving it in 1960. The original Siamese Tabby-points were the result of a mis-mating between a Tabby male cat and a Seal-pointed Siamese female. The Tabby-points were officially recognised and given a breed number in 1966.

Tortie-points were also seen along with Red-points (the same gene governs red and tortie). Red-points arose from an accidental mating, in the 1940s, of a Seal-point female with a Red male. This produced a Tortoiseshell female which was mated to a Seal-point male, producing the first Red-point. In 1966 Red-points gained official recognition. In the early 1970s there were classes for "Any Other Dilution" Siamese. These included Chocolate Tortie-points, Blue Tortie-points, Lilac Tortie-points, Blue-Cream-points, Cream-pointed Siamese and rare Tabby-Tortie-points. Some Cream-points had arisen which had almost no colour in the tail and little in the legs and feet: several experts considered them to be a separate breed. Tabby markings were still seen on the red-points and many cat breeders believed (correctly as it turn edout) that it would be genetically impossible to get rid of them.

The Brown Burmese recognised in America in 1936, arrived in Britain in the late 1940s and officially recognised in 1952. The first Blue Burmese was discovered in 1955. Other colours soon followed: the Chocolate or Champagne Burmese had been recently imported from the USA. Platinum Burmese followed. While the USA preferred to stick with only four Burmese colours, British breeders introduced the red gene into the Burmese, producing Cream Burmese, Red Burmese, Blue-Cream Burmese and Tortie Burmese. Apart from Britain, the only other country to produce these was Holland. Elsewhere they were almost unknown. Cream and Blue-Cream Burmese were recognised in 1971, Red and Tortie being recognised in 1973, just as the book was being published.

"The Abyssinian is the subject of much controversy in the cat world. In 1868, at the end of the Abyssinian War, a cat named Zula was taken to Britain. While some breeders maintain that this cat was a descendant of the ancient sacred cats of Egypt, it now seems more likely that Zula did not have the long, lithe figure typical of modern Abyssinians and that these eats were artificially bred by British fanciers." The Abyssinian was first recognised as a breed as early as 1882 when it was nicknamed the ‘bunny cat’ for its agouti coat.

In addition to the "conventional" Abyssinian, the Red Abyssinian achieved recognition in 1963. New colours were appearing in the "Any Other variety" classes: Blue, Cream and Lilac all arose spontaneously in litters of "otherwise normal Abyssinians", as did occasional Longhaired Abyssinians. Other colours were developed through outcrossing to other breeds. "According to available records, many cats exhibited as Abyssinians at the turn of the century were of very mixed ancestry. Several were called ‘silver’, which explains why the appearance of odd Blue, Cream or Lilac Abyssinian may well occur without special planning." However much work and selective breeding would be necessary to turn these into true-breeding varieties and they were rare.

The Havana was among the rarest of recognised breeds worldwide and had been recognised in Britain in 1958. Until 1970 it was known as the Chestnut Brown Foreign and had only been seriously pursued since 1953. "Initial matings were made between Chocolate-pointed Siamese, Russian Blues and black ‘alley’ cats, and in 1956 the first pair of Havana cats crossed the Atlantic to establish the breed there." These days, British Havana is closer to the American Oriental Self Brown than to the breed known in the USA as the Havana Brown.

Other Foreign Selfs were bred, though had not achieved official recognition. The Foreign Lilac (Lavender in the USA) was the self version of the Lilac-point Siamese, arising from crossing the Lilac-point Siamese with the Havana. In 1973 they were on the verge of official recognition. The Foreign White would be eligible for recognition in 1975. The Foreign Black Shorthair had been bred for several years, but had not achieved breed status. Apparently many good specimen appeared spontaneously in litters from Seal-point queens that were presumed to have made their own breeding arrangements with unknown toms! Foreign Blues were bred all over the world, often appearing in litters of Ebonies (the European name for the Foreign Black Shorthair). It was considered unlikely to achieve recognition in the near future as there were already other blue breeds of Foreign type: the Russian Blue and the Korat.

The Egyptian Mau in Britain was not the same as the American cat. In the USA, Egyptian Maus had been imported from North Africa in 1953 and now existed in Silver and Bronze forms. Because of the stringent quarantine restrictions in Britain, British breeders recreated the Egyptian Mau "by scientific means" and the English standard differed from the American one in that it required a clearly defined scarab beetle mark between the ears, and breeding stock is selected for the clarity of this mark. Later on, this breed was to be renamed the Oriental Spotted to avoid confusion with the American breed it had tried to recreate scientifically.

A breed group known in the 1970s, but not today (at least not by the same name) were the Oriental Pastels. These were being developed in the UK and were an entirely new series of Foreign Shorthairs which were being bred from existing Foreign Selfs and Foreign Spotteds. The pastel effect was produced by the introduction of silver genes to give the coat a shot-silk effect. By 1973, a lot of work had gone into the Oriental Pastels, but they had yet to appear at exhibition. The shades produced were called Oriental Silver, Dapple Silver, Oriental Blue, Dapple Blue, Oriental Lavender, Dapple Lavender, Oriental Apricot and Oriental Ivory. These seem to have become Oriental Tabbies/Spotteds which include the silver series.

BURMESE - Fur and Feather, Rabbits and Rabbit Keeping, September 17, 1970

(continued from page 864 [missing]) great work for the breed, but it is right that the early pioneers should be saluted.

The story of the cat in its native Burma follows the well worn lines of other oriental breeds – adoration in the homes of the wealthy, worship in the temples. The best part, though, is that much of it does seem to be true! No such high social welcome however greeted it on its introduction to Britain. The adult cat was clearly not lacking in stamina but the kittens, precocious in their very early lives, were easy victims to colds. The Governing Council, with understandable caution, was rather slow to give it official recognition. Gradually however the obvious charm of the breed became irresistible. The cat itself saw to that. The paw of friendship was extended wherever it went. Now as Mr Watson put it: “Burmese are very active cats, great climbers and jumpers. But in spite of this, they are extremely docile and must surely be most friendly of all cats. They accept strangers as though they had known them all their lives and are remarkably placid and free from temperamental behaviour. Their friendliness is often com¬mented on by judges at shows. They are very hardy and trouble Is far more likely to result from over-coddling than other¬wise.”

The cats brought from America to Britain were Brown Burmese but signs of a ‘silver’ [dilute] mutation soon became evident in 1955 Mrs Watson bred a blue kitten (seal coat Blue Surprise) and there were others. The results can be seen in our lovely Blue Burmese of today where the solid rich dark seal of the Brown Burmese is replaced with a body colour predominantly bluish-grey, darker on back and with the overall effect of a warm colour with a silver sheen to the coat. >The eyes in both colours should be almond in shape and slanting towards the nose in true oriental fashion and should be yellow in the Brown and yellowish-green in the Blue. There must be no white or Tabby markings in either colour. British breeders of both colours have done good work. New colours, even, may be on the way.

The Burmese of today is strong and healthy: it is ideal for the enthusiastic beginner who will receive from it untold joy Exhibition quality is generally high and British stock is valued greatly not only at home but abroad.

THE COLOURPOINT [LONGHAIR] - Fur and Feather, Rabbits and Rabbit Keeping, September 17, 1970

(continued from page 865 [missing]) tail should not have a kink. The eyes, in shape, should be those large round moons of all good longhairs, not the oriental slants of the Siamese but–like the Siamese – they must be blue, deep blue, clear and brilliant. (‘Clear, bright and decidedly blue, the deeper the better’ says the standard.)

We are back to the Persian, however, when we come to the quality of the coat, for the fur of the Colourpoint must be long and thick and soft to the touch. The frill should give a real Elizabethan framing to a full cheeked face in a broad, round head. It is important that there should be width between the small, well tufted, ears. The nose should be wide and, though short, should be at a decided angle to the forehead. The Siamese comes back into the story when we arrive at colour. Today there are four colours to the points, namely Seal Point, Blue Point, Lilac Point and Chocolate Point, each with an appropriate body colour as for the Siamese – cream for the seals, glacier white for the blues, frosty white for the lilacs and ivory for the chocolates. The Seals and the Blues were the first [LH] Colourpoints to be produced. The breed is comparatively new. It received recognition by the Governing Council only fifteen years ago. It is an ‘easy’ variety, but its fascination is undoubted. The first experimental work was done by Miss ’Kala’ Collins in 1949 and that work has been carried on with enor¬mous devotion by Mr Brian Stirling-Webb and others.

Is it a breed for the beginner? Yes. it is, with a proviso which applies to many other varieties of cat. The initial breeding stock must be. good and must have proved itself to be good, end the advice and assistance of the breeder must be sought and followed closely, especially in the early years. The cat has to be seen to be believed, but once seen its ‘intriguing’ charm can never be forgotten.

MAINE CATS – The Lowell Sun, 2nd January, 1973

These wild cats, or wild house cats, are interesting evolvements form Maine’s long history of involvement with cats. The sea captains of Maine are credited with introducing outland varieties to America. From their voyages and world around they would fetch home new and interesting cats as gifts to the wives and young-ones, and after a few decades of this, the cats of the world were sitting on Maine doorsteps. I don’t know if biologists have ever agreed about what a “Maine coon cat” was in the beginning, but for a long time it was considered a native oddity, and by non-Mainers a fine thing to have. There are hundreds of stories about tourists who admired a coon cat in passing, and stopped to offer a great price to a bewildered Mainer who had ten more in the barn and considered them a nuisance. About as good an explanation as any is that the Maine coon cat is a descendant of a Persian cat brought home around 1800.

“WILD” FEATURES MARK ABYSSINIANS APPEARANCE – Abilene Reporter, 13th August, 1973

The tri-color bands of ticking gives them the appearance of a rabbit, while the markings on their faces resemble those of a mountain lion. They are Abyssinians, thought to be the domestic cat of the ancient Egyptians, rare exotic-looking cats that are being bred in the U.S. on a limited basis. Candy Lewanski and her husband Jan, Air Force captain at Dyess, AFB, for two years, raise Abyssinians. The cat population at the Lewansky house currently rests at six – the father, mother and four kittens. “If you let them loose, the destruction is unbelievable,” Candy said.

The father is Niguel Gordon of Khartoum, the mother Morningside Abigail – Gordon and Abby for short. The oldest kitten, the last of Abby’s first litter, is named Purramount Theodorus, or Theo. The three smaller kittens, from Abby’s latest litter, have equally unusual names. The lengthy, exotic names are usually for registration purposes only, however, Candy explained. This helps confusion when several owners choose similar names to register these cats with the American Cat Association (ACA).

It wasn’t until the mid-60’s, she said, that the ACA recognized the Abyssinian as an acceptable breed. At that time the breed experienced “a sudden burst of popularity,” but breeding has been limited so they would not become too common, as happened with the Siamese, she said. Candy and Jan raise cats for show. “It’s a challenge to show a cat and when it wins, to know it’s one you have bred yourself,” she said. The couple also raise horses for show. Abyssinians are very people-oriented, said “Candy. “They’ll even come when called – most of the time.”

The Abyssinian is the result of mating between a breed of wild cat and a domestic cat, she said [note: not correct]. They were first introduced in the West in the 19th Century by the British, who got them in Abyssinia (Ethiopia), although there is some doubt that the cat is a native of the country. There are two kinds of Abyssinians, Candy explained. One has predominantly ruddy markings, as do her cats, and the other, red coloring.

A large obstacle to raising cats in Abilene, she said, is the considerable distance one must travel to attend cat shows. She and Jan returned recently from a showing in Wichita, Kan. Candy and Jan hope to mate Abby with the prize-winning Pharoah Citation of Swingale which has been judged best of all cats in 92 shows. Abby will be flown to Oregon for the mating.

PEDIGREE PETFOODS ON THE AMERICAN CAT BREEDS OF THE 1970s

Just as Mery had earlier mentioned the extravagant cat breeds of the mid 1960s, "Your Guide to Cats & Kittens" described several breeds not then known in Britain. One of those American breeds was naturally the Maine Coon Cat. The state of Maine in the USA, had made cat history by holding a cat show in the 1960s. The common eat of the area, with its bushy, striped tail, was thought to be the result of a cross between eat and racoon and was named the Maine Coon Cat. In the 1970s, experts believed it had probably originated from crosses between early Persians taken there by seafarers and a small lynx-like wild cat that became extinct around 1820. It was described as resembling the early Persians very closely in conformation, but lacked the undercoat of the Persian.

The Peke-faced Persian acquired its name from its resemblance to the Pekinese dog. Recognised only in the USA it was said to have been developed by selecting for and accentuating the heavy-jowled look of the Red Self and Red Tabby Persians. The most distinctive feature of that rare breed was its prominent, huge, round eyes and the extremely short nose which was "depressed and sharply indented between the eyes: in profile it is almost concealed by the fullness of the cheeks and the wrinkled folds of skin which cascade down under the eyes." In recent times, American Persians have diverged into the "normal" Persian regarded as ultra-typed and the traditional style Persian. The Peke-faced, now vanished, seems to have been a genetic oddity which caused skull deformities.

The Shaded Silver Persian was another variety found in America, but not recognised or bred in Britain (genetically similar, Chinchilla and Shaded cats are different only in the heaviness of the tipping, but in Britain only the Chinchilla was recognised, while in the USA both heavily and lightly tipped cats were recognised).

The Cameo was described as genetically identical to the Chinchilla, but with red ticking replacing the black ticking (nowadays the term tipping is used, ticking being reserved for the Abyssinian pattern). In the United States they were known by different names according to the degree of ticking present. Palest of the Cameos was the Shell. Next was the more heavily marked Shaded Cameo and deepest of all was the Cameo Smoke. A Tabby Cameo was also being bred with "a pale cream base coat and well-defined Red Tabby markings."

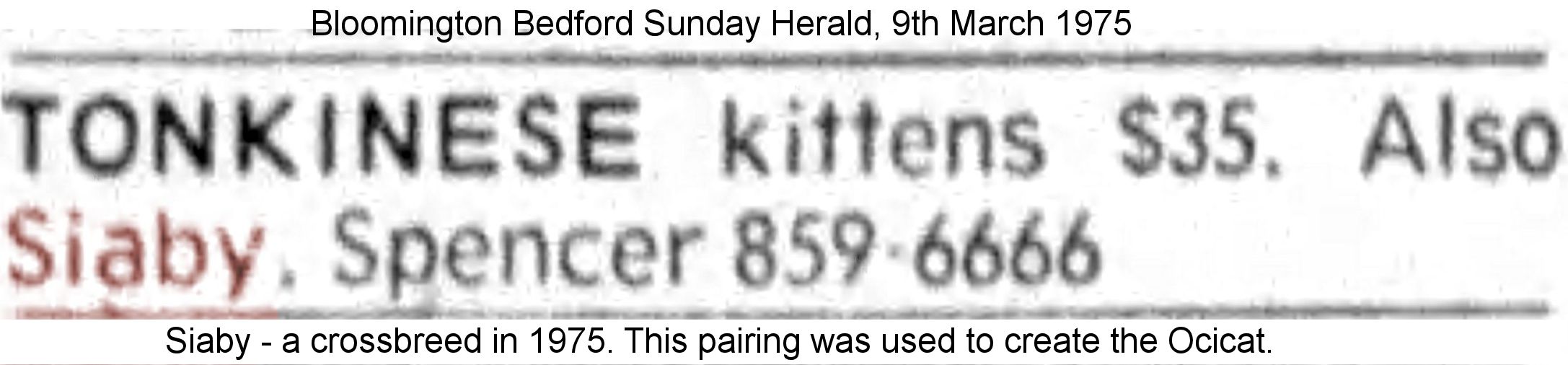

One of the rarest varieties of pedigree cats in the USA in the early 1970s was the Ocicat which had been developed in the 1960s. It was described as a large, exotic Spotted Tabby of Foreign type. Other breeds which had not yet reached Britain from the USA were the Cymric and the Japanese Bobtail. The Korat was being bred in the USA at the time, but "Your Guide to Cats & Kittens" noted that one had previously been exhibited at the London Cat Show of 1896. The existence of the Korat was given as a reason that the Foreign Blue Shorthair might not achieve recognition.

The Balinese, was a naturally occurring longhaired Siamese which had appeared spontaneously in the USA. Its coat was soft, silky, flowing and, ideally, at least two inches in length - a far cry from many of the modern Balinese which have been so extensively crossed to the Siamese (to get the conformation right) that they can barely be called longhairs at all! Modern Balinese are more an more turning into shorthaired cats with fluffy tails.

Finally one of the extravagant breeds which Mery had thought to be a passing curiosity: the bald Sphynx. Not only had it been recognised in the USA, the myth of the Sphynx breed ideal for cat lovers allergic to normal cats’ fur was spreading. Elsewhere in "Your Guide to Cats & Kittens" the Sphynx met with clear disapproval. In a section on deformities in fact, the authors wrote: "Hairlessness has appeared from time to time in cats and, despite criticism, some American breeders have decided to develop such wrinkled creatures into a separate breed known as the Sphynx. Despite this, it remains the responsibility of the dedicated breeder to ruthlessly exclude any deformed individuals from his breeding programme however heartless this may seem."

PHYLLIS LAUDER ON INTERMEDIATES (SEMI-LONGHAIRS) IN 1981

Between the longhairs and shorthairs existed cats with intermediate length fur. These were generally only found in the household pet classes of the 1980s. According to Phyllis Lauder, writing in "The British, European and American Shorthair Cat" (1981), longhaired cats had existed among the non-pedigree population in the West for a very long time, though their fur was fluffy rather than having the tremendous length of the carefully bred pedigree cats derived from imports from Persia and Turkey. Much prized by ordinary cat-lovers, the "fluffy cat" found in the native population was referred to by fanciers as an "intermediate" (now known as "semi-longhairs").

Many breeders considered that exhibition longhairs were descended from those "intermediates" by crossing them with the imported longer-haired Persians, Angoras and Russian Longhairs between the 1880s and early 1900s. Australian geneticist Mary Batten held the view that the fluffy moggies might have inherited their longer fur from the Scottish Wildcat or from cats brought from the Middle East by the Romans. Certainly fluffy cats had been present in the west for far too long to owe their existence to relatively recent imports. In addition, Mrs Batten had noted that some crosses of shorthairs and longhairs produced intermediates, for example, in 1967, a Tabby-point male bred by her was mated to a Chinchilla Longhair, and produced kittens whose fur was of intermediate length, rather than the expected shorthairs.

Lauder noted that while pet classes were dominated by shorthaired cats, the majority of the "longhairs" in pet classes were "intermediates" - they had "Persian-type" fur as opposed to short, but the fur bore no resemblance to the tremendous pelage of the exhibition quality longhair. Lauder also voiced the unsolved question of whether the show longhairs were originally bred from cats imported from Ankara or Iran (Persia), or whether they were the result of selective breeding from the native "intermediates" that exhibited a mutation for fur longer than that of the predominant shorthairs. Lauder wrote "probably simply a variation - with a coat of different length occurring in a predominantly short-haired population. These 'intermediates' were much prized by their owners in the early days of the century; people would say with pride 'He's got a fluffy coat!" Hence fluffy cats were bred to each other to perpetuate and exaggerate the trait.

The Australian geneticist Mary Batten wrote: "It is known that there are polygenes which influence shorthair coat-length. These may also be present in longhair lines [...] It is arguable as to whether the 'fluffy' cat received its coat-length from the Persian or Iranian aristocrats or from the blending of cats brought from these areas by Romans, and the indigenous Scottish wild cat. However, almost certainly the factor which has produced the 'fluffy' coat is common to both sources. It is not an allele of either longhair or shorthair, but is a separate gene or polygenic series".

From a modern perspective, it should be noted that longhairs are not descended from Scottish Wildcats (nor from Pallas's Cat) and though the Romans may well have brought longhaired cats with them from the Middle East, the genes for longer fur could equally well have come from Scandinavian settlers who brought with them the variety now known as the Norwegian Forest Cat. Longhaired cats are found throughout Scandinavia and Viking longhairs could have contributed the longhair gene into the gene pool of British cats.

PHYLLIS LAUDER ON HYBRID AND NATURAL BREEDS IN 1981

In 1981, Phyllis Lauder wrote of an article about the hybrid Safari cat that had been published in Cats Magazine in March, 1980: "An article and lovely picture describing a cat called a Safari, a cross between a domestic shorthair and a South American feral [note: wrong use of feral - the author meant "wild species"] cat known as Geoffroy's cat, and belonging to the genus Leopardus. To judge from the pictures, one of them in full colour, and the descriptions given by the writer, Patricia Hall Warren, the Safari strongly resembles the Spotted cat who is one of the domestic shorthair Tabbies. This cross-bred cat has a great deal of patterning which includes many clear, distinct spots, and Mrs Warren describes the Safaris as '... Shorthairs. They wear a rich and specialised Spotted Tabby pattern of bars, dots, rosettes, face streaks, wavy stripes, leg bracelets and tail rings'. In her description of the type of these cats Mrs Warren tells us that they have long bodies, but she also says that they are robust and that they have small ears. It appears that the Safaris have been crossed successfully with Siamese and also with North American shorthairs. It seems likely that the cross with a Spotted Tabby shorthair could produce beautiful kittens. And it is interesting to note that the progeny are fertile. The writer says that people believe that a hybrid must be infertile, but that this is not the case with feline hybrids."

Lauder also noted "In France the Blue shorthairs are known as Chartreux. There has, now and then, been put forward the idea that the British Blues and the Chartreux were different varieties of shorthair cats; but well-known judges in France and Britain have always been aware that the two terms are simply different names for the same cats. The Blue shorthair doubtless existed in France and England in the Middle Ages; it is quite reasonable, indeed, to suppose that he voyaged as ship's cat from Calais to Dover and back and if the fancy took him, went ashore and settled in either country." (In Britain, the Chartreux is not recognised as a different breed, however in the USA it is recognised in its own right and has different conformation to British Blue Shorthairs.)

"The varieties newly recognised as show cats by governing bodies are often spoken of as man-made, and this is a misnomer, since man can achieve nothing in the cats that nature unaided could not have produced. However, what man can do is to select this or that feature as desirable and, by careful breeding programmes, encourage the appearance and continuance of the character of his choice. 'We speed up evolution ... it isn't that man creates, but just that he operates with the variations that occur' (the late A C Jude). This places a heavy responsibility on man, for it sometimes gives rise to an exaggeration not conducive to health. An example is the narrowing of the face in Siamese: because the suggestion of length in the heads of these cats was pleasing to the people who fostered them, the standard drawn up for them asked for a long head; and this feature has, by selective breeding, been so much exaggerated that some of the cats have narrow, snipey faces, with very small lower jaws; it is even said that some breeders in the USA have had teeth extracted from Siamese cats in order to make their heads appear narrower. The longhair too, with his width of head and tiny nose, has often occluded nasal ducts and an overshot jaw. Thus man, exaggerating natural features, sometimes fails to put good health first [...] had their lower jaws weakened as has happened in Siamese, sometimes bred for extreme length of head so that they are, as described in France, 'Surtypés'."

Of the original conformation of shorthaired cats Lauder wrote ""We may hazard an informed guess that he was a short-haired animal of more-or-less rounded type, and with colouring of a wild-type pattern approximating to agouti or to some sort of tabby, or possibly tending towards the 'speckled' fur which the Cat Fancy of today knows as Abyssinian. It has been claimed that the first recorded cats were long-headed, but this is not always borne out by the facts. The claim is based upon mummies in tombs and upon ancient Egyptian representations in stone: the cats were etched in a sort of bas-relief, and represented in profile, and these carvings show some length of head [...] more recent cats of eastern provenance have not shown long heads: in the 1930s and 40s there was, at the Natural History Museum in London, a stuffed Siamese cat, and this animal's head was 'as round as an apple' to quote one of England's prominent experimental breeders, the late B. A. Stirling-Webb. The taxidermist's work showed a large cat of strictly 'domestic' type."

THE CPL ON THE CARE OF MOTHER CATS IN THE 1960s

The CPL did not recommend people to keep female cats, unless they were prepared to look after them and their kittens in the way they should. The problem of kittens and the rarity of spaying meant keeping females was seen as the pursuit of the serious breeder rather than the everyday cat lover. However they gave a few hints on the general treatment of female cats. The first was that they are technically termed "queens" (queans) as opposed to the male cat being called a "tom"! The language used was rather coy. The young queen could "begin to have a family" any time after 6 months and could have three or four families each year. Great restlessness, crying and rolling about, etc., "will begin to draw the owner’s attention to the fact that the cat is now an adult".

This was the coy allusion to oestrus. No details were given of mating. However, nine weeks later "the family will arrive". The prospective mother needed plenty of wholesome food in many small meals and should not be given "lumpy food". Much handling should be avoided, and she should never be lifted up carelessly or pulled about by children. "Mother cats require extra food, both before and after the kittens arrive, and the food should be as nourishing as it is possible to give. Avoid constipation by giving a teaspoonful of Medicinal Paraffin twice or three times a week, a fortnight before the kittens are due to arrive."

Shortly before the family arrived she would look for a comfortable nursery. This should be provided in a quiet corner out of draughts. A suitable nursery would be "a large lidless wooden box turned on its side with a narrow board fastened across the front near the floor to prevent the kittens falling out". The bedding should be soft and clean. If newspaper were used unless, they should be well covered by soft white paper, flannel, etc. This was because the newspaper print was poisonous and the cat would be injured by it if she licked kittens whose coats had been in direct contact with it.

The mother-cat should be kept absolutely quiet and undisturbed when the family arrived. As long as she had been well nourished in pregnancy and while nursing, the kittens would generally thrive. If she died or could not feed the kittens, instructions on hand-rearing were provided (these are mentioned elsewhere in these web articles), but more often than not most or all of the kittens were destroyed by the vet and the mother encouraged to forget about them.

PEDIGREE PETFOODS ON SHOWING AND BREEDING (1970s)

Showing and breeding of cats had come a long way since the advice given by France, Cox-Ife and Soderbergh in the 1940s and 1950s and discussed in

Part 1 Of Cats And Cat Care Retrospective. A Very Brief History of Breeding describes cat showing and from 1871 to almost the present day. According to "Your Guide to Cats & Kittens", in the 1970s there were now over 50 recognised breeds in Britain. In truth there were very few actual "breeds"; the British registry classified each colour division of a breed as being a separate breed. This system was described as daunting for the 1970s newcomer.