CATS AND CAT CARE RETROSPECTIVE: 1900s - 1930s: BREEDS AND VARIETIES: SIAMESE, BURMESE, AABYSSINIAN, HAIRLESS AND JAPANESE

This article is part of a series looking about cats and cat care in Britain from the late 1800s through to the 1970s. It is interesting to note how attitudes have changed, as well as how our knowledge has increased.

Siamese

This article about “The Siamese Cat” was printed in The York Daily, 1st October, 1909 and came from “The Cat Review” of that year.: “The Siamese comes from the kingdom of Siam, where I first met him, and is of two classes; the common and the temple cat. The common or garden variety differs from the temple in the same manner as a thoroughbred differs from the mongrel, whether cat, horse, or dog. The temple cat is the outcome of long years of careful breeding and anxious care. He is jealously guarded by the bouzes (priests) of the temple, and enters in some way which I have never been able to discover into their religious rites and sacrificial offerings. His exportations has been prohibited for many years as he has always been in great demand among cat fanciers, and so many were carried off that the prices became fabulous, and the priests objected, as there was fear that the royal line might become extinct. Oh, yes, there la a royal line of cats, of which there were two in this country. The pure Siamese temple cat is born pure white and at the age of two or three months shows markings of blue gray on tail, legs, and ears. As time passes these turn brown and at six months the face, tail, ears and feet show a beautiful brown color, like young seal, while the body is as yet white with just enough color to warm it. The greater the age of the cat the deeper will be the color of the fur. The eyes are of a beautiful azure; blue in daylight, they flow like live coals at night. I have had thirty at a time. I sent a pair to the exhibition at Liege, which were sold for six thousand francs. Five hundred dollars is not an excessive price for a pure specimen."

This article discussed the emerging “blue-pointed Siamese”. It appeared in “Cat Gossip,” 12th December 1928. “Mrs. Allen-Maturin writes: I have been asked to say a few words on the blue-pointed Siamese. These are very rare, but I was fortunate enough to breed three lovely ones this summer. Two of them, a male and female, were sired by my stud, Southampton Darboy, and they took, respectively, 1st and 2nd prizes in the Siamese Club Show, and some kind friend said they were the best specimens ever benched. Most people regard them as freaks, and this knotty point has not yet been solved.

But freaks or not, they are very lovely animals, with the palest of cream coats and lavender blue points, viz., mask, paws, and tail, and the eye is usually a very bright blue. I use the word ‘lavender,’ as I think that is the best description of the colour that the points should be. Sometimes the points are of a stone grey colour, which detracts from their beauty. They always remind me of a bit of delicate china. Blue Siamese can be bred to colour if an unrelated male and female are mated, the litter should prove to be all pale blue Siamese; if a blue male is mated to an ordinary seal-pointed queen the offspring will probably all be seal pointed.

It has been suggested that the blues are a throw-back to the Korat Cat, which is found in the hill districts of Siam. The latter are a small animal with a pale blue short-haired coat (the colour of a pale blue Persian); they have no decided points, and I am not sure as to the colour of their eyes; they are extremely delicate, and so far none have been imported into England. I have been trying to get a pair for a long time, but so far have not succeeded. I have seen photos of them which belonged to a gentleman who had just returned from Bangkok. He had a couple as pets, and said they were most engaging and entertaining, and used to walk about on their hind legs! He gave me a description of their colouring, etc. I still hope that some day I may be the proud possessor of one. "

A mention of the Korat (alluded to above) could be found in “Cat Gossip,” of September 28, 1927: From Mrs. Croucher, who lived for some time in the Far East came the following interesting notes: The Korat cat, to which reference was recently made in Cat Gossip, is blue with orange eyes, and frightfully rare; all the time I was in Bangkok I only knew of two, one belonging to my neighbour and the other to Mr. B.O. Cartwright, B.A. I went on purpose to obtain some notes on these cats for you. He told me he was offered £100 for his cat.

Another mention of Blue Siamese comes from “Cat Gossip,” 12 December, 1928: From Highcliffe, Shelford Road, Radcliffe-on-Trent, Mrs. Stokes writes anent some blue “Siamese” she owns: “I think I told you that they are a pretty French bluey grey, shot in gradation from light to dark - like shot plush - and, when the light is on them, show a distinct dark tiger marking, quite regular, right to the rings down to the tip of the tail. They certainly have orange eyes, although at certain times and in varying lights they show a tendency to green. Their heads are wedge-shaped really, with a squarish nose, especially the females, and the males are inclined to fill a little, both in the jowls and in the flanks. The limbs of the female especially are dainty and delicate, being small in the bone, and they are all exceptionally affectionate, being most sensitive to either reprimand or affection. Their parents (of pair that I have) belonged to a Mrs. Campbell, of Nottingham, who owned both the sire, Ray, and the dam, Trixy, and she always insisted that they were a very rare blue variety of Siamese. She has now left the town, but if I can get in touch with her any time I will go into the matter further with her.”

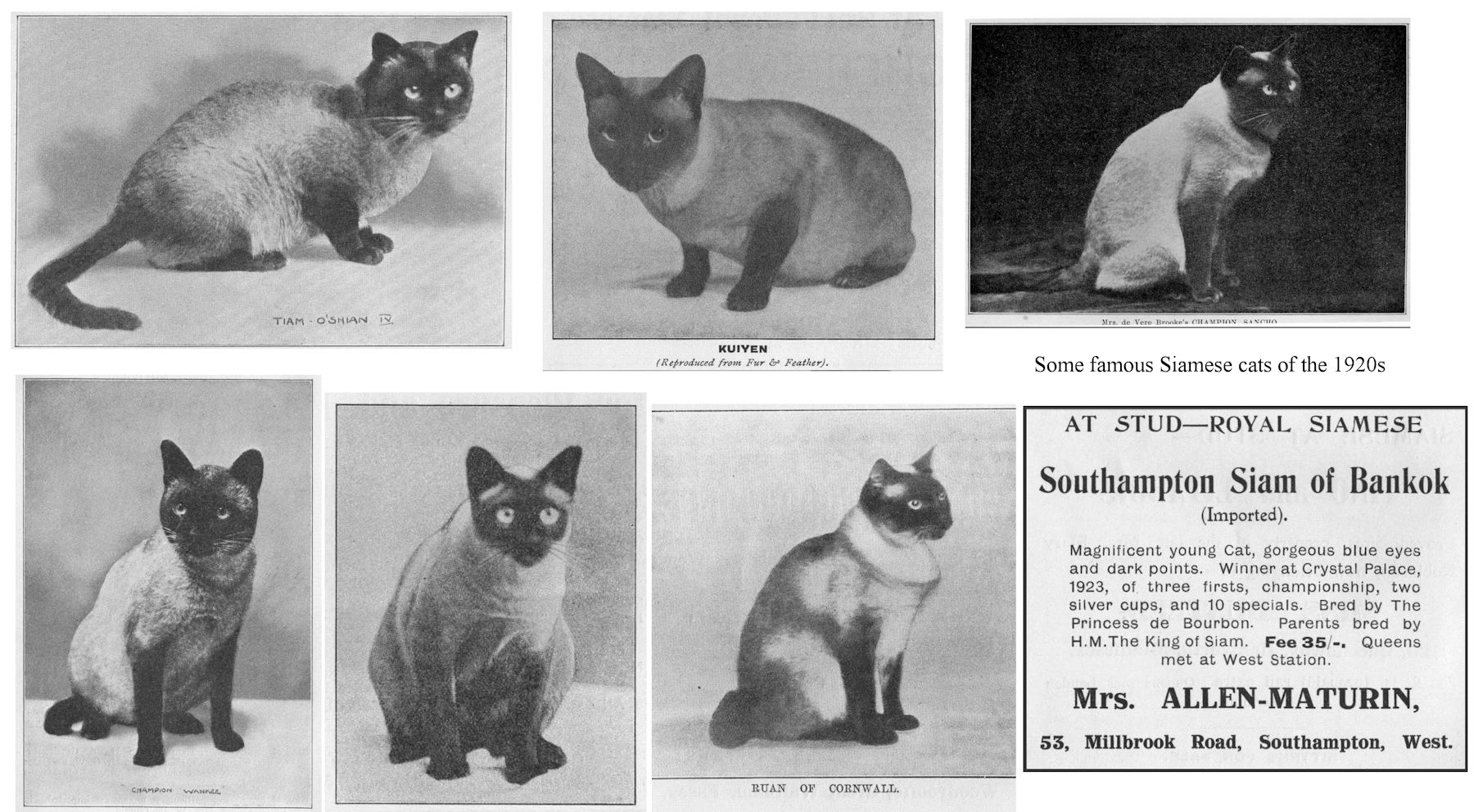

In "The Book of Knowledge" (circa 1935) edited by Harold FB WHeeler, it says "A Costly Royalty of Siam": Among the different types of domestic cats a few are deserving of special mention. The Siamese royal cat is the rarest and commands the highest price. Its face, legs and tail are brown; its body is cream-coloured, and its eyes are light blue. The Angora, or Persian cat is distinguished by its large size, its long silky hair, and its flesh coloured lips and soles. The tortoise-shell cat is very popular in Spain, and is especially noted for its intelligence. The Manx cat is the most ungainly-looking representative of the cat family. Cats are very useful in destroying rats, mice, and other harmful rodents, but they have also won a bad reputation for killing birds. Felis is the scientific name for cat. Domestic cat, Felis domesticus; Angora cat, Felis domesticus angorensis; Manx cat, Felis domesticus ecaudatus.

Of the Siamese, another of the earliest cat breeds, Ida M. Mellen, American authority on cats and author of the "Practical Cat Book" (1939) wrote "Although this cat generally is referred to as the Royal, and even as the Sacred Siamese, it is the common cat of Siam, just as the Manx, equally an aristocrat, is the common cat of the Isle of Man." Dr. Hugh M. Smith, Adviser in Fisheries to His Siamese Majesty's Government between 1923 and 1934 had written to Mellen: "There are no "palace" cats in Siam. There are no "royal" cats, although the strikingly marked creatures would be the natural ones to be kept in palaces. Any person can have a Siamese cat, and as a matter of fact there are many people outside the palaces and many foreigners who keep such cats as household pets. There are no "temple" cats. The Buddhist priests, who do not live in the temples but in special buildings in the temple grounds, may keep cats, as they do dogs. A Siamese prince whom I know very well was visiting in London and was interviewed by one of the thousands of Siamese cat fanciers there. He told her there were more Siamese cats in London than in all Siam."

There was also the curious experiments of crossing of Siamese cats with Persians and even with tabbies as detailed in "Siamese-Persian Cats" by Clyde E. Keeler and Virginia Cobb, "Journal of Heredity" v. 27. No. 9. Sept. 1936, and "Crosses with Siamese Cats" by K. Tjebbes, Journal of Genetics, V. 14. p. 335, 1924. He noted that in 1939 when Ida M. Mellen reported these facts in her "Practical Cat Book" the experiments were still proceeding.

Albino Siamese, and Self-Red Shorthair

CAT RESEARCH. Coffee-Coloured & Pink-Eyed Strains. White cats with pink eyes, and Cats the colour of ground coffee are the latest ambition of the zoological department of the University of Liverpool. One cat of each of these new types in the possession of the University, and elaborate breeding experiments are being undertaken in an endeavour to establish permanent strains. The white cat appeared in a strain of Siamese, and first attracted attention at the Paris show of last year. Its distinguishing feature is the pink colour of the eyes, for although albino rabbits are exceedingly common, albino cats have been hitherto unknown. The second cat was shown by the late Mr. H. C. Brooke as a “self-red” at the Crystal Palace. But it is pointed out by the workers at Liverpool that its colour is entirely different from anything found on a normal “red” cat; in fact, that is a true dark brown without markings. Nothing is known of the origin of this cat, nor of how its colour can have been transmitted. (Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, 10th April 1931)

Abyssinian

Capt W H Powell, cat fancier and experienced judge, wrote of the Abyssinian in 1938: "There is no other breed of cat against which nothing can be laid in the way of disparagement. The coat of the Persian requires constant attention and the shortness of his nose renders him liable to sniffles. The Siamese is immune from the coat trouble, but even its most ardent admirers must sometimes wish her vocal powers were less well developed. The quiet, unassuming Abyssinian combines all the good points and none of the failings of his more widely advertised relations." Of the controversial "Silver Abyssinian" (or Chinchilla Abyssinian as it was also known) he wrote "I hope it will never again be allowed in the show pen."

A Mrs H W Basnett's contribution to "Fur, Feather, Rabbits and Rabbit Keeping" (1938) read "The typical Abyssinian has a long, lithe body, showing well-developed muscular strength, and the beauty of the long, fine head is accentuated by luminous, almond-shaped eyes. The whole head is set off by large ears, broad at the base, which, while matching the feet and legs in colour, are tipped with a darker shade. The coat is short and close-lying, of a rich, tawny brown colour, and instead of being striped or barred, each hair is 'ticked' with black or brown, i.e., two or three bands of colour on each hair being preferable to a single ticking'. The feet and legs must be clean colour, free of barring and toning with the body colour, whilst the under parts of the body should preferably be an orange-brown to harmonise with the main colour."

ABYSSINIAN CATS IN THE LATE 1920S (1929, HC Brooke)

H C Brooke, foremost breeder of Abyssinian cats for many years, was Vice-President of the Abyssinian Cat Club when he wrote this description of the breed and its history. At the same time, he condemned cat fanciers for their lack of interest in breed histories and their excessive interest in exhibiting.

It is with genuine regret that I have to state that it has been impossible, even though some years ago I appealed for the help of some of the oldest members of the Fancy, to discover any really satisfactory facts regarding the history of this beautiful and interesting breed in this country. The fact is deplorable, and I cannot but regard it as typical of the want of deep interest in matters apart from mere breeding and exhibiting, which is so noticeable in the Cat Fancy. I could give other instances, which, however, would rather be out of place here.

In my opinion, and in that of certain eminent Continental Zoologists, the Abyssinian Cat may be regarded as the nearest approach to the Sacred Cat of Ancient Egypt now existing. (Sad to say [...] I am not aware that any English naturalists have turned their attention to this eminently interesting breed.) From the various mural and other paintings which have been preserved to us from the days of the Pharaohs, we see that the most common coloration of the domestic cat in Egypt some three thousand years ago, was much that of the African Wild Cat of to-day: that is to say, rather lightly striped in the manner of the tiger, not with the heavier longitudinal markings we usually call "Tabby." When and where and how the true tabby markings originated I cannot say, and I doubt if anyone knows.

A foreign scientist of some eminence wrote a few years ago that he considered the tabby [stripy] pattern to be latent in all domestic cats but the Siamese, and with this opinion I quite concur, though I am sure not only breeders of Abyssinians, but also of [shorthair] Blues, would be very thankful were it not the case. I have examined several dozen skins of the African Wild Cat, which has received so many names in every language. (Fettered, Egyptian and Caffre Cat, it has been called in English; in Latin it has borne yet more synonyms), and whilst the large majority have been the common grey lightly striped form, there have been others which in gradation lead up to the Abyssinian as we know it.

As far as I have been able to ascertain, the first specimen of the Egyptian or African Cat to be described was the female mentioned by Rueppel, under the name of "Smallfooted Cat" (F maniculata) in his "Atlas zu der Reise in Noerdlichen Afrika". It appears to show some of the characteristics we demand in the Abyssinian: small size: "Its size is that of a middle-sized domestic cat, and smaller than the European Wild Cat by one third: all the proportions of its limbs are on a smaller scale"; colour: "Ochreous, darker on the back" (c.f. the "eel-stripe"). The illustration shows an ochreous coloured cat, with slight markings on tail, limbs, and face - just, as we find in inferior Abyssinians. This cat was found in Nubia.

At the present day, in the Natural History Museum, is to be found a small Surdanese Wild Cat (F ocreata), of a rusty-red colour, slight in build, with slender limbs, and lightly marked on tail and legs. It reminds one at once of a certain Abyssinian Champion, whose colour is admirable but who fails in "ticking". In the specimens I have studied, I have been able to observe how the striping in some individuals degenerates into indistinct spotting, the spotting in its turn degenerates in certain specimens into a sort of mottling - an impression also given by some inferior Abyssinians - and then we get the plain unmarked specimens, with more or less ticking. I failed to find any well-ticked skins at the British Museum, but at the great Wembley Exhibition I saw a number of African Wild Cat skins exhibited by a firm of furriers, almost identical with our Abyssinians. The "foreign" type we prefer in this breed is apt to appear and become more or less fixed in any variety in which we selectively breed with small, slender, and elegant specimens, in preference to those of a cobby or massive build.

In the accompanying illustrations I show the gradations in the African Wild Cat of to-day from the faintly spotted form to the faintly mottled, well-ticked, modern Abyssinian type; and in the papyrus painting, over 2.000 years old, of an Ancient Egyptian Cat, we find the brown body with barred legs and tail of the third rate Abyssinian of today, the belly being of an ochreous yellow, such as we look for in a brown Abyssinian.

As I remarked above, it has been impossible to obtain details as to the early history of the breed in this country, though surely it should have been possible to ascertain when the breed first received official recognition, when it was first catered for at Shows, who were the first exhibitors, and so forth. Some details as to the early exhibits would also have been of great interest. The earliest reference I have seen is that made in one of the late Dr. Gordon Stables' books, "Cats, their points, etc." (1882). The cat therein portrayed is described as being the property of Mrs. Barrett Lennard, and as having been brought from Abyssinia at the conclusion of the Abyssinian War. The portrait, however, is not instructive, as it resembles no Abyssinian Cat that I have ever seen, but I judge this to be due to poor colour printing. In the quaint "Book of Cats" (CH Ross, 1867) no description is given, but we find this statement: "In Abyssinia cats are so valuable that a marriageable girl who is likely to come in for a cat is looked upon as quite an heiress".

When The Cat Club was doing its best to ruin The National Cat Club, nearly thirty years ago, it dropped the title of Abyssinian from its Register, and inserted instead "Ticks". At that time what we must call "British Ticks", often also known as "Bunny Cats", were far more common in various parts of the country than they are now; these cats were usually as well ticked as any Abyssinian, though some had a "mottled" appearance. Mr Louis Wain was very fond of them, and obtained for me two or three nice specimens from various parts of the country. Their ground colour was usually a dark grey or blackish grey; they had heads of a pronounced "British" type, and heavily barred legs and tails. At that time the Abyssinian seemed to stand in danger of becoming extinct; of the few that existed many were shy breeders, kittens were difficult to rear, and these British Ticks made a useful outcross. It is remarkable how they crop up in different parts from time to time from ordinary "garden cat" parents; this, I think, is undoubtedly a reversion to ancient type. About five years ago I saw a fine male in the possession of the caretaker of a Public Hall in North London; there is a charming little queen in a cottage near here which appeared in an ordinary mixed litter of kittens belonging to a Taunton draper.

A few years ago an extraordinary and beautiful form appeared amongst those owned by Sir William Cooke; in these the ground colour was creamy white, but the ears and dorsal stripe showed the rabbit-coloured fur so characteristic of the breed. Unhappily this lovely mutation was allowed to die out, and at present I only know of one existing specimen. The eyes of these cats were blue. To me it is very saddening to think that apathy has been responsible for the loss of several charming varieties of cats, and when we consider how any interesting or pretty mutation appearing in Rabbits, Mice, or Rats is eagerly fostered, I feel the Cat Fancy has little cause for pride. The fact that this Albinism appeared progressively shows that it was not, as has been suggested, due to a chance Siamese cross.

Probably the best Abyssinians ever seen in this country were Sedgemere Bottle and Sedgemere Peaty, the property of Mr. Sam Woodiwiss. They were, as far as I know, not related, and if this be the case it is really remarkable how two such specimens were obtained. They were very much the colour of a hare. Peaty ended her days in my possession, and I have always regretted not having preserved her skin, to at least retain her glorious colour, though her beautiful sinuous form and delicate limbs can hardly be imagined by those who have not seen her.

About thirty years ago some very good Abyssinians were shown by the late Mr. Heslop, of Darlington; Mrs. Alice Pitkin also exhibited some fair specimens, many of hers, however, being too dark and "British Ticks" in type. Later Mrs. Clark, of Bath, possessed many excellent specimens. I bred quite a number at that period, perhaps the best being Chelsworth Peaty, who greatly interested Queen Alexandra, then Princess of Wales, when I exhibited her, suckling a ferret, at a Botanic Gardens Show. I sent quite a number to Continental menageries and fanciers; early in the century, however, I gave up all dog and cat breeding, and left London for the West Country to devote myself entirely to hunting. Had not Mrs Carew-Cox about this time devoted herself to the breed I very much fear it would, ere now, have become extinct. Neglected [...] by the Fancy at large in an inconceivable manner, this beautiful and interesting breed certainly owes its existence today mainly to the devoted care and affection bestowed upon it by Mrs Carew-Cox, who for a quarter-of-a-century has fostered it in the face of discouragements which I verily believe would have "choked off" any other person in the Fancy. Not for her the "big business" in stud fees, the "queued-up" queens, the cups and specials galore, which fall to the lot of many [Longhair] breeders; no, in the face of rotten judging, lack of recognition, poor prizes, lack of market, and a heartbreaking mortality in kittens, this plucky lady has carried the Abyssinian flag triumphantly through. She cannot (or modestly will not?) tell me how many champions she has bred since some thirty odd years ago she fell in love with the first specimen she saw at an hotel at Winscombe, Somerset, where they were said to have been left by one who had been a traveller in "furrin parts". Incidentally, I may mention that a good many years back Mrs Carew-Cox published a couple of letters from a gentleman who had been shooting in Abyssinia, and who stated that he had there shot a pair of wild cats, whose skins he brought to England, and which seemed from the description to correspond in every way with our present-day exhibition specimens.

To conclude, I will now give a description of the characteristics of this lovely breed.

The general appearance of the Abyssinian is that of a rather small and very elegantly built cat, with graceful slender limbs, elegant head, with rather large ears and lustrous eyes. What is commonly called in the Fancy the "British type" is here out of place; we do not want round short head, small ears, cobby build, powerful limbs. Of course, to those who can see no beauty in a cat which has not a head like a Pekinese the Abyssinian will not appeal, and I have read descriptions by such people referring to the Abyssinian as "gaunt" and "half -starved looking". As a matter of fact, any person capable of appreciating truly graceful lines and sinuous and elegant shape in the Cat, will admit that in this respect the Abyssinian has but one rival, to wit, the Siamese. The most usual colour of the Abyssinian very strikingly resembles that of a wild rabbit, in fact I have known many whose fur could not be distinguished from that of the rabbit, when placed side by side, until carefully examined, when it is seen that the fur of the rabbit is grey near the skin (under colour), whilst that of the cat is, or should be, rufous. The "ticking" is a most essential property in the Abyssinian, and is caused by blackish, or dark brown, tips to the hair. Some - the best ticked - have about threequarters of the length of each hair rufous, then two, or three, bands of brown or orange shades, the darkest being at the tip. Others have merely the rufous base and the dark tip. The under-colour should always be as bright and clear as possible, not a dull lifeless brown, which much detracts from the beauty of the cat.

Some years ago there were a number of so-called "Silver-Abyssinians" in existence. I regard silver as an absolutely alien colour to the breed, and though there would have been no harm done if these silvers had been kept to themselves, I cannot but think that they did an infinity of harm to the breed, by introducing a grey tinge into the coat, with the result that the beautiful ruddy tinge which we used to see in the cats of long ago, is now apparently lost to us. How they originated, or whether any cross was made use of to obtain them, I do not know. I am not aware if any Silvers exist now; personally I hope not, though some may not agree with me in this matter. Brown of a warm tint is evidently recognised by the older writers as the real Abyssinian colour, and I think Harrison Weir, writing in 1882, is the first to mention "Silvers", which he does as a sort of afterthought, referring to them as a new variety. For a while, some judges seemed to go crazy about them. Some Abyssinians are far more grey in general appearance, and in others the predominating tint is rufous. We find the same difference in the Wild Rabbit, whose coat so closely resembles that of these cats. Some greyish looking cats have yet a lovely ruddy undercoat. But to give a general impression of the colour we should strive for in these cats - though it seems non-existent nowadays - it is hard to improve upon the comparison with the Hare or Belgian Hare, dear to the older writers.

Absence of markings, i.e., bars on head, tail, face, and chest, is a very important property in this breed. Those places are just where, if a cat or other feline animal shows markings at all, they will hold their ground to the last with remarkable pertinacity. The less marking visible the better; at the same time, the judge must not attach such undue importance to this property, that he fails to give due importance to others. For instance, it does not follow that an absolutely unmarked cat, but of "cobby" build, failing in ticking and colour, is, on account of absence of marking, better than a cat of slender build, well-ticked, and of nice colour, but handicapped by a certain amount of "barring" on legs or tail. The belly fur is not ticked as on the rest of the body, and should be free from spots or stripes; the colour should be a light brown, matching the other parts.

Much has been said for and against the "eel-stripe" - the darkish line which in some specimens runs down the centre of the back. Personally I am indifferent; but, if allowable, it is certainly not to be regarded as a racial characteristic. (For the simple reason that all breeds tend to have a darker line down the back, which in some is an absolute defect; in the case of the Abyssinian it is not objectionable, and is approved by some people.) A little black tail tip seems to me to give a nice finish; the heels are also black. Ears large and open, and a blackish or dark brown tip to the ear is desirable. The head looks slender and pointed, but not of the wedge-shape or "marten-face" sought for in the Siamese. The heads of old males naturally tend to be more massive and round than we wish to see in the case of females and young males. Eyes: These should be large and lustrous, of a kind expression; more oval than in the "British" cat. As regards colour, I prefer a bright green, personally, but a nice amber eye is certainly preferable to a "greenery-yallery", washed-out looking eye. White marks of any kind, such as on chest, throat, or toes, taboo in show specimens. The colour of the paws should be of a very delicate yellowish brown tinge, harmonising with the general colour scheme.

The character of the Abyssinian is usually very gentle, rather shy, not taking readily to strangers, but very affectionate. In short, it is one of the most charming and interesting varieties we have, and it has time and again been shown that a really good Abyssinian can usually be relied upon to do pretty well when it comes to judging the "mixed special prizes" at Shows.

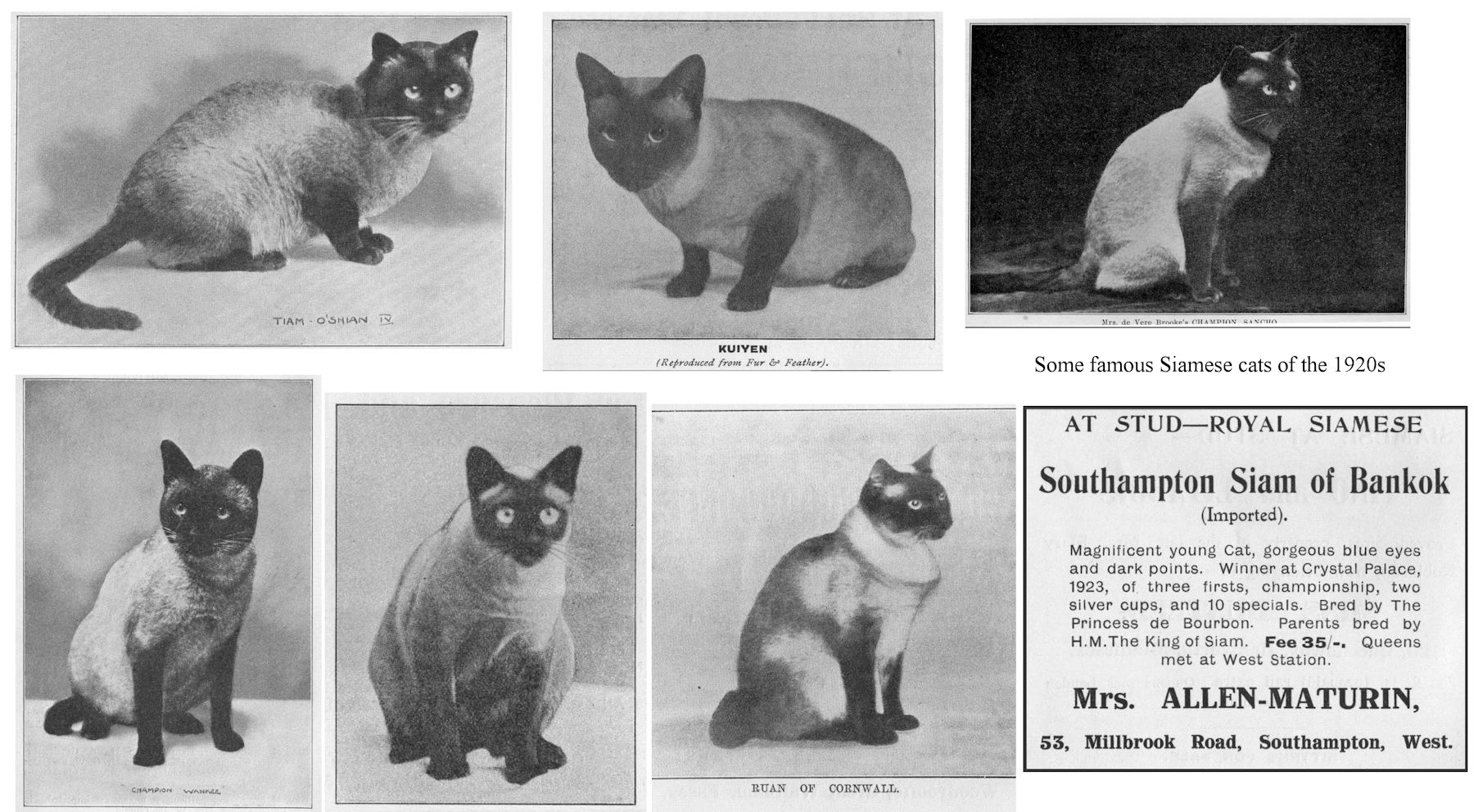

SIAMESE(LATE 1920s)

Mrs. Cran, an authority on Siamese cats, wrote in “Cat Gossip” of the “Temple Mark,” though she admitted her information was scanty. According to her account, two distinct markings may be found on the backs of some highly bred Siamese which were said to be the distinguishing feature of the True Temple cats. The priests considered such cats to be especially sacred, but Mrs. Cran did not know the full story, or the name of the god who “once picked one up and left the shadow of his hands for ever on its descendants.” The shadowy marks do not form a saddle, but suggest that someone “with sooty hands had lifted a pale-coated cat, gripping his neck rather low down. They are not often seen.” But, she adds: “They are certainly a distinctive mark, and not an accidental marking.”

SIAMESE CATS (G. Gleeson) in The Scotsman, 15th January 1932

It is generally considered that Siamese cats are very delicate creatures, requiring all sorts of fussing and cossetting if they are to remain in good health. Yet at Cleish Castle, in Kinross-shire, a hardier type of Siamese cat is born and reared without difficulty. Scottish air and Scottish pasture seem to brace these cats and keep them in first-rate condition. If you are only used to a majestic Siamese who lolls on a cushion half the day and is constantly groomed by human hands, the Siamese cats of Cieish Castle come as rather a shock. The kittens are born out of doors. Cats and kittens are outdoors at night and forage for themselves. They enjoy rain and appear to revel in snow.

So far as looks go, they are absolutely true to type. They have the long, pointed head, long body, and slender legs you expect in Siamese cats. Theirs the blue eyes and the unmistakable cry of the real Siamese . Their close, glossy coats are of cream or pink, with face, ears, feet, tails, and underneaths of chocolate colour or seal brown. Their lovely coats are never groomed by human agency, even when they are due to appear before judges at a show. So long as they are in good condition, which is most of the time at Cleish, they show themselves able and willing to see to their own beauty culture. Against more pampered cats they stand as rivals at cat shows, and more often than not carry off the prize.

Rabbits they hunt with avidity, and rabbit is, indeed, their staple food. Rats they kill when they have leisure. All Siamese cats, of course, are wonderful ratters. Sailors say that if there is a Siamese cat aboard not a rat is seen during the whole voyage. Other Scottish women might advantageously breed Siamese cats, seeing that the Scottish climate, contrary to what one would have supposed, is congenial to the race. Siamese cats are not so expensive now as they were a short while ago, but a female cat still costs about 30s., while a cat of a really good strain costs anything from £10 upwards. The sale of Siamese cats is, therefore, a particularly profitable business once you have established a connection and made some name for breeding these cats well. Regular visits to shows keep the woman cat breeder in touch with the latest fashion in Siamese cats, and she generally finds that cats with very irregular colourings are not easy to sell. The rare kind of Siamese cat, with chocolate coat and yellow eyes, are not a suitable variety for the woman who breeds Siamese eats for profit.

THE ROYAL SIAMESE (1936)

A cat may look at a king, but not many cats have the opportunity. Siamese cats for more than two hundred years have dwelt in the royal palaces at Bangkok and had kings, queens, princes, and princesses to look at. Those who did not live at court lived in temples and had priests to serve them. So they are not only royal but sacred, the modern prototype of the sacred cat of Egypt. Of course there have always been street cats in Siam, but they have kinks in their tails and do not count. The first Siamese cats to leave that country were two fine specimens that were given to some titled Englishwomen by the uncle of Prajadhipok, the recently abdicated king. They were much admired in England, and founded the line which soon became popular there, and, later, in America. The origin of the Siamese cats is obscure. They may have come from crosses between the sacred cats of Burma and the Annamite cats when the Siamese and the Annamese conquered the Burmese empire of the Khmers about three centuries ago.

The Burmese sacred cats were an ancient race of which little is known. It is said that they were like the Siamese in colour, but had splendid bushy tails and long hair [note: possibly the Birman, not the Burmese]. The Burmese, like the people of Siam, believed that the spirits of the dead dwelt within the sacred cats. I have seen in shows cats that were called Burmese, but I doubt if they were authentic. However, our best Siamese are genuine. King Prajadhipok must have had cats in his entourage when he last visited America, for he gave two to a New York woman during his stay. Siamese cats are like Prajadhipok. Though born to palaces they are very democratic and alertly interested in everything they see. A Siamese cat is more energetic and can be in more places at once than any other member of the Felis domesticus. I took my collie-setter Luddy to call on Frederick B. Eddy's Siamese in Red Bank, New Jersey, and he retired under a sofa with his tail to the world, disconcerted by a liveliness with which no mere dog could cope.

The number of Siamese cats in the United States is not large compared with the number of longhairs, but they are getting a good hold, and there is a flourishing Siamese Cat Society of America, which conducts its shows under the Cat Fanciers' Association of America. Its standard of points conforms to that of the Siamese-cat societies in England. True Siamese are medium in size, with a wellmuscled body, not fat, and very lithe and graceful in action. The head is wedge-shaped, long and narrow, the ears broad at the base and small at the apex and very neat and well-defined. The legs are rather thin and not long; the hind legs are slightly longer than the forelegs. The feet are somewhat smaller than those of the domestic short-haired cat. The tail is thin and tapering and not very long.

A good many people think that Siamese cats have kinked tails. So learned a commentator as M. Oldfield Howey asserts in his fascinating book, The Cat in the Mysteries of Religion and Magic, that the kinked tail has been a Siamese characteristic for two hundred years. There is a Siamese legend which says that somebody once tied a knot in a cat's tail to remind it of something (perhaps to leave the throne room backward) and the knot stayed. Another form of the story is that a princess strung her rings on her cat's tail while she bathed, and tied a knot to keep them from falling off. But the royal Siamese have no kinks. Any kinky-tailed Siamese in America were brought here by sailors who picked them up in the streets over there. Richard Lydekker in his Library of Natural History, after describing the "breed of cats in Siam reserved for royalty," adds, "Siam, together with Burmah, also possesses a breed known as the Malay cat, in which the tail is but half the usual length, and is often, through deformity in its bones, curled up tightly into a knot."

The coat of the Siamese is soft and short and glossy. The body is coloured a clear, pale fawn, the face is deep chocolate brown shading to fawn between the ears, and the ears, tail, legs, and feet are brown. Siamese kittens are born snow white, but the distinctive markings soon appear, and at one year of age these cats attain their loveliest contrast between the fawn and brown. After this they slowly darken. There is a blue-point Siamese in which the body is pale blue and the face, legs, and tail dark blue. Blue points are rare, a sort of "sport," but the Cat Fanciers' Association includes a class for them in its show rules. The pigmentation of the blue point is what is called recessive, and those who are curious about scientific breeding might be interested to know that if a seal point were bred to a blue point the darker colouring of the former would probably prevail in the kittens. The eyes of the royal Siamese are blue, and the better the cat, the darker are the eyes. In shape they are almost round, but with a slight Oriental slant toward the nose.

Devotees of the Siamese insist that they are the smartest cats in the world. But every cat-lover knows that his or her cat, be it Siamese or Persian or Manx or plain alley, is the smartest cat in the world.

HAIRLESS CATS IN THE 1930s

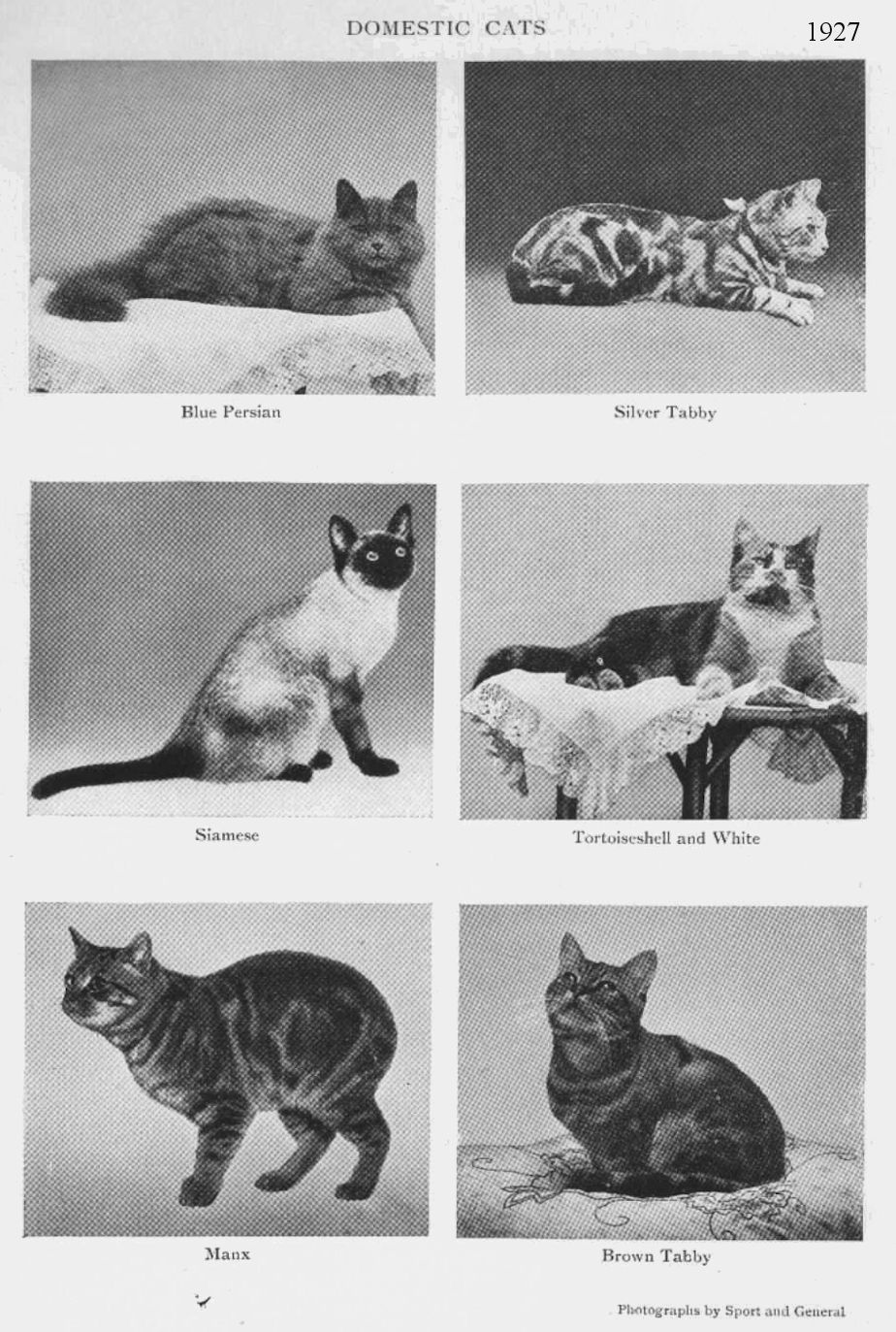

Letter From Henry Sternberceh of Wilmington, N. C. to The Journal of Heredity in 1936 titled 'A "Cat-Dog" From North Carolina Hairless Gene or "Maternal Impression"?'

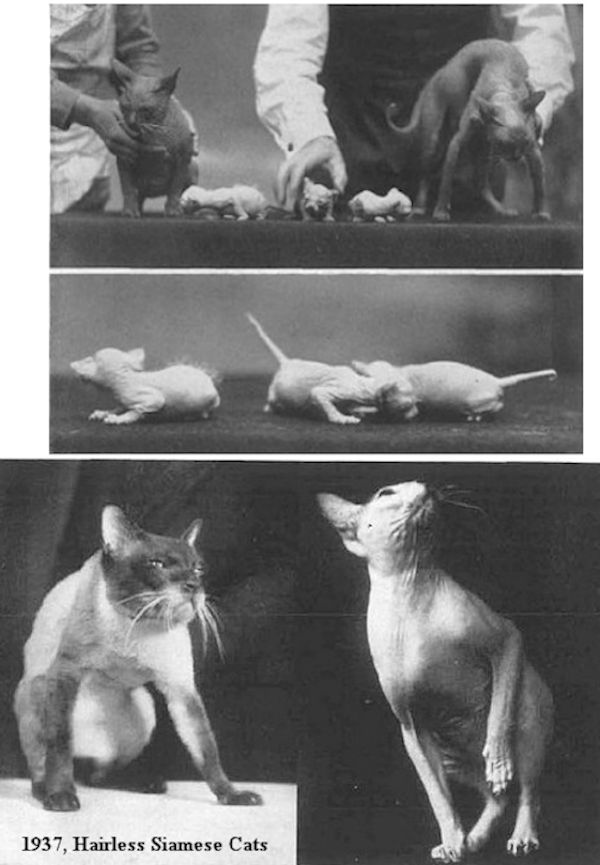

Hairless Cat Or Cat-Dog: Three views of an abnormal kitten which appeared in a litter of four, only one of which was normal,—two of the others being short tailed. The genetic nature of this variation is unknown, but it has a striking resemblance to some of the genetic hairless forms in rabbits and mice.

Around the middle of August, 1936, a curious litter of kittens was born to a perfectly ordinary appearing pet cat, belonging to Mrs. Annie Mae Gannon, of Wilmington, N. C. Of the entire litter, only one of the kittens is perfectly normal in appearance - the other three being freaks. One of the cats has no tail at all; another has only a stub of a tail. But the extraordinary member of this feline family is the fourth—well, we can hardly call it a cat - so for want of a better name, we'll call it a "Nonesuch."

It is said that before the kittens were born, the mother cat was often engaged in fights by a mixed-breed dog in the neighbourhood, and on several occasions was badly frightened by the dog. This is about the only plausible explanation as to why the "nonesuch" is so unusual in appearance. In fact, this little animal - now about two months old – is about the queerest looking creature one could hope to set eyes upon. Its face is that of a black, white, and yellow spotted dog. Its ears are quite long and sharp pointed. It has the short whiskers of a puppy. The hind legs are amusingly bowed. It has a stub tail. What makes the nonesuch even more unusual appearing is the short smooth dog hair all over its cat-like body.

From the very moment of its birth, which was about twelve hours after the rest of the litter, the nonesuch was surprisingly independent in its actions. It was born with its eyes open, and was able to crawl a little - two characteristics quite unknown to new-born kittens. The nonesuch acts both like a cat and a dog. While it makes a noise like a cat, it sniffs its food like a dog. Nothing delights the nonesuch more than gnawing a bone in a very dog-like manner. When resting, little nonesuch places its paws straight out in front just as a dog would do. The little creature doesn't relish playing with the rest of its family, being entirely contented in stretching out and watching the others frolic about.

The Editor replied:

Geneticists would be more inclined to ascribe the appearance of the unusual animal described above to the action of a recessive mutation than to the ancient doctrine of maternal impressions. If the curious kitten does represent a mutation, it is one of no little genetic interest, as offering a further parallel between mutations in the cat and the rabbit. (See Keeler and Cobb, Journal of heredity 24 :181-184. May 1933). To judge from Mr. Sternberger's pictures and the description, "Nonesuch" must rather closely resemble the Rex rabbit. It was hoped that it might be possible to obtain "None-such" and test the matter genetically. Unfortunately his owner is reported to feel that this unusual creature should be so valuable for museum or sideshow purposes as rather to put it out of range of genetic experimentation. In a later letter from Mr. Sternberger we learn that all the other members of the litter have died, so that there seems little hope of being able to do more than record the occurrence of this odd form.

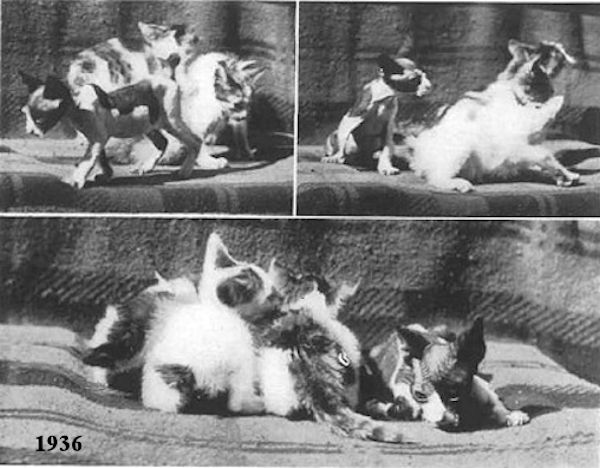

Professor Etienne Letard (Professor at the National Veterinary School of Alfort (Seine) France) replied in a 1938 issue of the Journal of Heredity in a letter titled 'Hairless Siamese Cats'

Hairless Siamese Kittens And Their Parents: Two views of hairless Siamese kittens twelve hours old, and their parents. All of them are hairless though one has a thin coat of short hairs. Note the fur distinctly visible on one of the kittens. This is especially thick on the ears and in the axes of the limbs. It disappears in a few days, being followed a short time later by another transitory coat.

The two accounts of "Nonesuch", the alleged cat-dog hybrid in the Journal (March and September, 1937), have greatly interested the writer because he has had an opportunity to study a startingly similar variation in Siamese cats. The accompanying photographs show the appearance of the hairless cats, whose resemblance to "Nonesuch" is obvious. The origin and description of this hairless strain follows. A pair of Siamese cats, perfect in type with normal hair and coloring, produced from time to time one or two hairless kittens in a litter consisting otherwise of normal kittens. From these periodically appearing hairless individuals we have been able to create a strain of hairless cats, which we believe to be entirely pure.

"Carrier" And Naked Siamese Cats: On the left is a normally haired Siamese cat, which mated to a normal-haired male produced hairless offspring. She thus carries the recessive hairless gene. At right a mature hairless Siamese cat, the type of this recessive mutation. Note that the vibrissae ("whiskers") are normal. The whiskers of some hairless mammals are also affected.

If one mates one of the two individuals who have produced this mutation, with other normal Siamese cats, a hairless kitten has never been produced. Only the mating of the two individuals in question produces the mutation. The crossing of a hairless animal with other normal individuals has never produced a hairless cat. We have mated two hairless cats, brother and sister; three hairless kittens were the result. With the exception of unforeseen circumstances which would have to be studied, the "hairless" can therefore be considered a type governed by the Mendelian law with hairlessness recessive to normal coat. Thus we find ourselves in possession of a strain, apparently already stable, which might be the origin of a distinct race, resuscitating the ancient race of so-called Mexican hairless cats, which is believed to be extinct.

It is imperative to mention that, though certain specimens are completely hairless, others have a slight down on their bodies. This down is subject to periodical changes, apparently closely connected with seasonal variations in temperature. Strange as k may seem, the young ones which grow into hairless cats are not so at birth, but have a growth of hair, less dense, however, than normal. A transitory pelage in young hairless rats has also been reported [Wilder, W., Et Al. A Hairless Mutation in the Rat. Journal of Heredity 23 :481- 484. 1932] The fact that the typical pattern of the Siamese cat is controlled in its development by temperature [1. Iljin, N. A. and V. N. Temperature Effects on the Color of the Siamese Cat Journal of Heredity 21 :309-318. 1930] may have a significance in this connection. This growth is most marked on the ventral surface and in the axils of the limbs. Between the tenth and fourteenth day after birth this juvenile hair has disappeared, and the "hairless skin" has become reality. The skin remains bald for several days and this is followed by another growth of hair. When the kitten has reached the age anywhere from eight to ten weeks it is covered with an abundant growth of hair which gradually disappears, until at the age of six months the final stage of adult nakedness has been reached; either the skin is completely hairless, or covered with a slight down, subject to seasonal changes.

The fact that this mutation was observed in animals which have always lived in Paris, proves again that it is not always in special environments that one has to search for visible variations, and emphasizes again the random nature of spontaneous changes in inherited characters which appear to be one of the basic mechanisms of organic evolution.

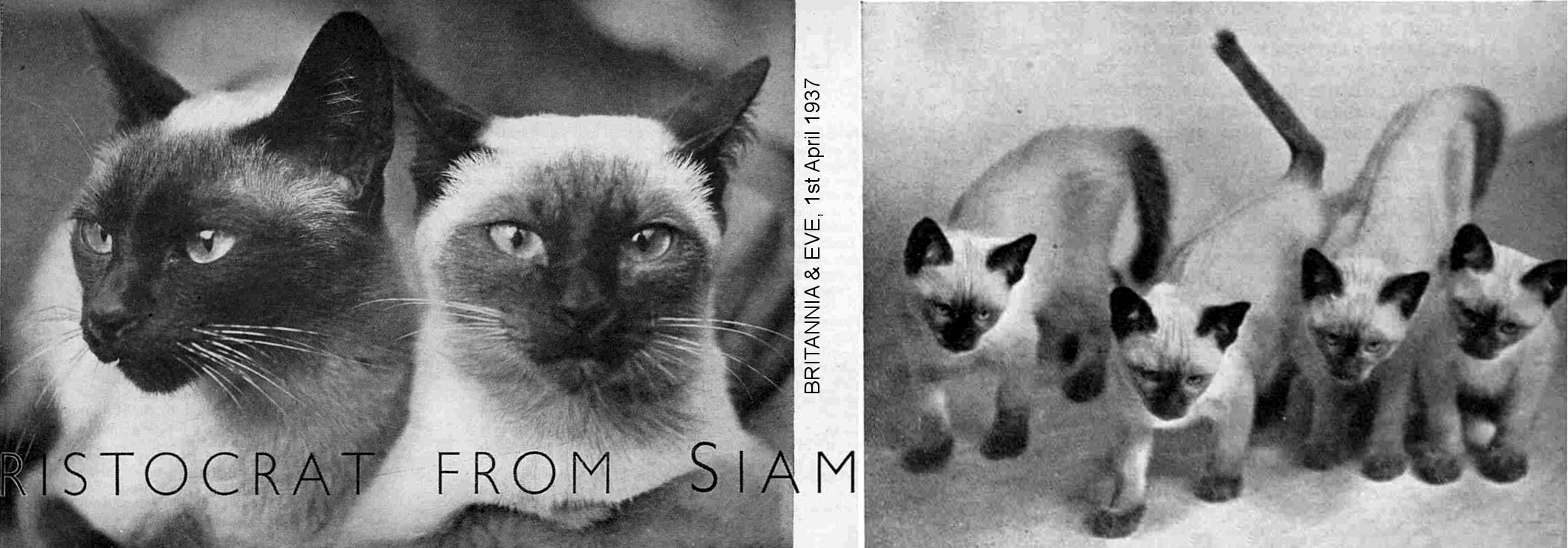

ARISTOCRAT FROM SIAM - Britannia & Eve for April, 1937

Most people are agreed that Egypt was the first country to have domesticated cats; indeed, the Egyptians appreciated the qualities of these animals so much that they worshipped them, and had their bodies embalmed after death. This probably explains the attitude of most cats of to-day. Human beings were made to wait upon them and administer to their material needs. All they have to do is to look ornamental. Egypt in the past had a flourishing trade with the East, and it is believed that cats were sent out in ships to protect the grain from rats, and so arrived in the Malay Archipelago, the home of the Siamese cat of to-day. In Malay there was the Sacred Cat of Burmah and the Annamite cat (the Annamite cat had a kink in its tail, a marked characteristic of some Siamese), and somehow from these the Siamese cat evolved, the skull and body having the shape of the cats of Egypt.

So highly were these cats regarded in Siam that for two centuries they were allowed to be owned only by the king, and so were exclusively found in the royal city of Bangkok. Thus their full name “Royal Siamese.” Occasionally a grateful monarch would present to a foreign friend a specimen of these much-prized pets, and so gradually they found their way abroad, though not until the beginning of this century were they a breeder’s proposition in England.

The Siamese Cat Club was founded in 1901, and though the war for a time held up importations, the present day shows one upward curve of increasing popularity. The reason for this vogue is undoubtedly the character of the Siamese cat itself. Attracted to it first by its beauty, the new owner’s affections are quickly enchained by its quaintness and originality, by its quick intelligence and lively interest in all its owner's doings, by its vitality and grace of movement. The Siamese cat is often called “A cat-and dog-in-one.” It can be taken out for walks on a collar and lead, if trained from a kitten. It adores going out in a motor-car. One cat I know always accompanies his master, a busy doctor, on his rounds. It can be taught tricks like dogs, too. It develops little tricks of its own. No Siamese ever repeats another Siamese trick. They are much too individual.

The Siamese with a kink (a sort of knot in the tail) is thought to be more amusing and original as a pet than the straight-tailed type, though the judges frown on the kink in the show-pen these daYS. I think this is a pity, as it is certainly one of the most striking features of the breed and, as it is inherent, will be difficult anyway to eradicate. How the Siamese cat possesses those brilliant blue eyes, which are a great part of its beauty, is something of a mystery. Some think it due to their being part albino. Certainly the eyes turn ruby-red in the dark, lighting up like lamps at night, or when they are angry or excited. Some cats that are described in the show-pen as having bad eye colour have a definite pink tinge in a pale-blue eye, instead of the admired bright blue.

The Siamese cat is spotlessly clean and, of course, is much less trouble to brush and keep tidy than the former favourite, the Persian. Original in all things, he generally scorns milk as being the mainstay of the ordinary tile-walker. Water he loves (again like a dog), and raw meat to tear his teeth on and remind him of his wild ancestry. Bones for his jaws to grind, cooked rabbit and fish, are his staple diet, with brown bread to provide the vitamin B necessary to his princely development. This makes him sound a wild creature. But in reality, though he is fey, self-willed and perverse at times, he can be as gentle and pussyish as the mildest little English tabby- cat. He is, indeed, devoted to human beings; attaching himself, as n. Airedale dog is supposed to do, to his owner with an almost embarrassing devotion. Even more than for his own kind, he craves human companionship and affection. - A. B.

ABYSSINIAN CATS IN THE 1930s

TO EXHIBIT RARE CAT – The Plain Speaker, 17th October, 1938

Philadelphia, Oct. 17. - A rare Abyssinian cat, member of a breed that once stalked the palace of Ethiopian emperors before the Italian conquest, will be exhibited at a cat show to be staged by the Quaker City Persian Society October 28-29.

THE BURMESE (AND EARLY TONKINESE)

BURMESE FELINE BEAUTIES - The Honolulu Advertiser, 5th July 1936

First photos to reach Hawaii of the new breed of short-hair cats recently accepted as standard and entered for championship classes by the Cat Fanciers’ association. They are from the Mau Tien (Cat Heaven) cattery of Dr. J. C. Thompson, of San Francisco, who is remembered here as a psychoanalyst and former medical officer at Pearl Harbor. The photos were sent to Mrs. Nella Wright. Above, Mrs. Wong Mau of Man Tien, yellow-eyed, sable Burmese queen with dark seal points, first of her breed to be imported to the Coast. Mated to a Siamese she is shown here with her litter of four kittens, two light brown Burmese and two typical Siamese kits. Below, left, Mrs. Wong Mau of Mau Tien in a dignified pose. Note the large, level eyes, the rounded ears and the delicate, pointed oval of the face. Below, right, Tai Mau of Mau Tien, imported Burmese of excellent type. Profile shows sinuous, graceful shape of body, tapering legs and leopard-like head.

CATTY CORNER BY NELLA S. WRIGHT - Honolulu Advertiser, 28th June1936

Many of our local friends will remember Dr. Joseph C. Thompson, at one time medical officer at Pearl Harbor, who retired several years ago to take up private practice as a psycho-analyst in San Francisco. The doctor always had a house full of cats which he regarded with almost religious affection, treating them as though they were real persons - which is probably closer to the truth than most of us ever get! A caller recently on his way home from a trip to China, a Dr. Dwight Goddard,. who has been engaged in a translation of certain Buddhist scriptures or “sutras,” spoke of his acquaintance with Dr. Thompson and of his devotion to his cats, of which he has a fine collection at his home in San Francisco, specializing in Siamese and Burmese.

Close on the heels of Dr. Goddard’s' visit came a letter from Dr. Thompson, enclosing a series of interesting photos of the newly recognized breed of Burmese. Though only recently admitted as standard and accredited a Championship classification the CFA, the Burmese is really a very ancient cat, antedating the Siamese. “This cat,” writes the doctor, “is the ancestor of the Siamese, which as you know, are partial albinos, like the Himalayan rabbit.” Now it happens that Dr. Thompson has collaborated with the Harvard Medical school in research work and the study of genetics in which the development of the Siamese is regarded with special significance as establishing some sort of a principle under the Mendelean laws, and he not only ought to be but really is a recognized authority on the subject.

Dr. Thompson calls his cattery Mau Tien, Chinese for Cat Heaven, and his pets all have Chinese names ending in “mau,” which the doctor translates as “meow.” Thus a snap of a girl holding five lovely Siamese babies bears the notation on the back – “Children of Tai Mau (big meow) and She Shan Mau (snake hips meow), of Mau Tien (cat heaven).” Incidentally it may be noted that Dr. Thompson has traveled extensively in the Orient and can speak and read both Chinese and Japanese. For this reason we will not quarrel with his translations any more than we would with his interpretation of Mendel’s laws, to which we have made previous reference in this column.

To return to the photos of Br Thompson’s Burmese cats, of which there are four interesting poses. Of Mrs. Wong Mau of Mau Tien, “yellow-eyed meow,” he writes: “Wong was the first Burmese to come to the coast. She is half Siamese and half Burmese, but as Burmese is dominant to Siamese she is thus all Burmese outside; that is, in appearance. Bred to a pure Siamese, Tai Mau, the kittens are half of them pure Siamese and half are Burmese crosses like the mother, Wong.” This is an interesting statement and will come as a surprise to many who do not understand the peculiar operation of the laws of genetics, which govern the transmission of the dominant characteristics in the first cross between different breeds. This was a point that aroused considerable discussion at a recent meeting the Honolulu Cat club, some of the members being unable to understand how Mendel’s law operated to preserve all the characteristics of the dominant strain or breed in the first generation of an outcross.

Mrs. Wong Mau, though half Siamese, is all Burmese in every respect as to standard, transmitting her breed true to half her offspring. She is described as “very beautiful sable brown with dark seal points.” The eyes are a “golden turquoise” and have no tendency to squint. The fur is very short and very fine and glossy. When the kittens are born they are a light brown.

KITTEN MAY BE FIRST OF NEW BREED, SAYS CAT AUTHORITY

By Mrs. May H. Rothwell, Honolulu Star Bulletin, 5th August 1936

An unusual kitten at Miss Lelia Volk's home, 1041 17th Ave., which has caused considerable comment among cat fanciers, has attracted the attention of a national authority on cats. Shortly after arriving in Honolulu aboard the Asama Maru, Prof. Clyde Keeler of the DeBussy Institute of Harvard university visited Miss Volk and was immediately interested in the kitten, which he said might be the first of an entirely new breed.

“I am of the opinion that it is neither a true Siamese nor is it a true Burmese,” said Prof. Keeler. “Too dark in color for one, it has not the right eye color for the other. Possibly it is a completely new breed. Possibly a new gene than that which produces the Siamese, or it may be due to the Siamese gene plus a new modifying factor or third allelomorph form. If this should prove to be the case the cat is really a hybrid and as such extremely interesting. Its type may be fixed in time and a new breed, unknown at the present time in the states, be created. I shall want to hear of this little princess and shall watch her career with keen interest, as I believe you have something new and different in feline development.”

NEWS OF ISLAND CATS

By Mrs. May H. Rothwell, Honolulu Star Bulletin, 1st May 1937

Princess Thebaw, the lovely Siamese anomaly about which so much speculation has been rife since she appeared about a year and a half ago in a litter of purebred Siamese kittens, has again surprised all interested in her. Recently she gave birth to three kittens, sired by Prince Projadapok, that were all dark like herself. Prof. Clyde Keeler, when visiting in Honolulu last year, saw Thebaw and pronounced her as the possible forerunner of a new breed of oriental cats, a sport that might prove to possess the ability to create a distinct variation of the Siamese type. He predicted that she might, when mated to her sire, produce one in a litter that would resemble herself.

To the surprise of her owner, Miss Lelia Volk, the kittens were all dark skinned, having even more pigment than their mother. It is quite certain that the interest shown in the past in this cat will gain new impetus by this new development. It seems more than ever certain that a new breed of cats will be developed from this remarkable cat. And it all happened right here in Hawaii, too.

It was first thought that Thebaw was a throwback to some far away ancestor of the allied race known as Burmese, but she bears no real resemblance to that breed at present. Her eyes, at first yellow, turned green and now are blue, as in the Siamese. In other ways Thebaw shows a difference from the Siamese, especially in the coat, which is softer and finer than that of both the Siamese and Burmese breed.

JAPANESE CATS IN THE 1930s

This was printed under the title "The Japanese Kimono Cat" 1936 and describes a particular type of black-and-white cat valued in Japan. One was taken to Britain, but was not bred. It would be many years before the Japanese Bobtail was recognised as a breed.

Humanity has used cats in many ways to express and to personify forces of good and evil that it did not understand. The Egyptian worship of cats had its germ in the feeling that they were one manifestation of the divine, and the Celtic tribes of early Europe believed that the demoniac powers which, they thought, surrounded them and threatened them appeared oftenest in the form of cats-large black tomcats. The belief that cats enshrine the spirits of the dead has cropped up in various primitive peoples, but it remained for Japan to give it its quaintest turn. East is East and West is West, and it is hard for the Occidental mind to comprehend why a cat that is born with a black mark on its back resembling a woman in a kimono is thought to contain the spirit of the owner's honourable grandfather or great-aunt and is sent to a temple to be kept from contamination by the vulgar. Nevertheless, there have been quite recent examples of this faith in some sects or portions of the Japanese public.

These kimono cats were never given away, or knowingly sent out of the country, but early in this century one was stolen and carried to England. A Chinese servant committed the theft, and he smuggled the cat, a female, aboard an English ship. The captain wanted to return her to the priests of the temple from which she was taken, but so great was popular indignation over the theft that he was afraid to reveal that he had her. And even a British officer might have itching fingers where such a curiosity was concerned. So the little Kimona sailed for England, and went to live with a family in Putney, who, according to an account Dr. Lilian Veley wrote for Cat Gossip, respected her traditions and gave her a happy home. Kimona was uncannily human in her ways, and decided in her likes and dislikes. She would eat no fish or vegetables or milk, nothing but raw meat. She was not snooty about her past except in one respect. British tomcats she simply could not abide, and she lived and died a spinster. Dr. Veley took some photographs of Kimona, and they were printed in "Cat Gossip" shortly before the cat's death in 1911. The black saddle on her white body might with some stretch of the imagination be thought to resemble a fat woman in a kimono. She had a black mark on her head, coming down over the cheeks, like a cap with lappets. Her tail was black and very short, broad at the base, almost triangular in shape.

There is a statue in Japan that is dedicated to cats, not the sacred kimono cats but the little commoners that are sacrificed to make catgut for the samisen, the Japanese banjo. It stands in front of the great Buddhist temple to Nichiren in the Yamanashi Prefecture, and one of the figures, that of a nun, has a cat's head. Samisen manufacturers placed it there, not so much from remorse as that they feared that the spirits of the slain animals might return to haunt them and injure the samisen business. Incense is burned there, and prayers are said to appease and propitiate the cats and to assure them that the manufacturers regretted the necessity of making them into samisens. Even the geishas of Tokio contributed their hard-earned yens to have religious services for the dead cats before the big bronze statue. And I suppose it did the geishas good, if not the cats.

Cats play a more sinister part in some of the remote districts of Japan, where apparently the belief in vampires still survives. In the London Sunday Express for July 14, 1929 there was printed a report that the dread vampire cat of Nabeshima was once more, after a long absence, abroad in the land, seeking to bewitch the wives of the descendants of the old fighting Samurai. F. Hadland Davis in his Myths and Legends of Japan tells the story of this feline vampire that once upon a time harried the noble Nabeshima family. It slew O Toyo, the sweetheart of the Prince of Hizen, an honoured member of the Nabeshima race, and assumed her form, and in that guise sought to destroy the prince. But he was saved by the vigilance of Ito Soda, a faithful soldier, and the vampire, changing into a cat again, escaped to the mountains, where it was slain by hunters sent by the prince. That is the legend, but if we credit the item in the Sunday Express some of the Japanese believe that the creature had a life in reserve. It is to be hoped that it has not the fabled nine lives of our own harmless cats.