CATS AND CAT CARE - A RETROSPECTIVE: CAT PHOTOGRAPHY AND CAT ARTISTS

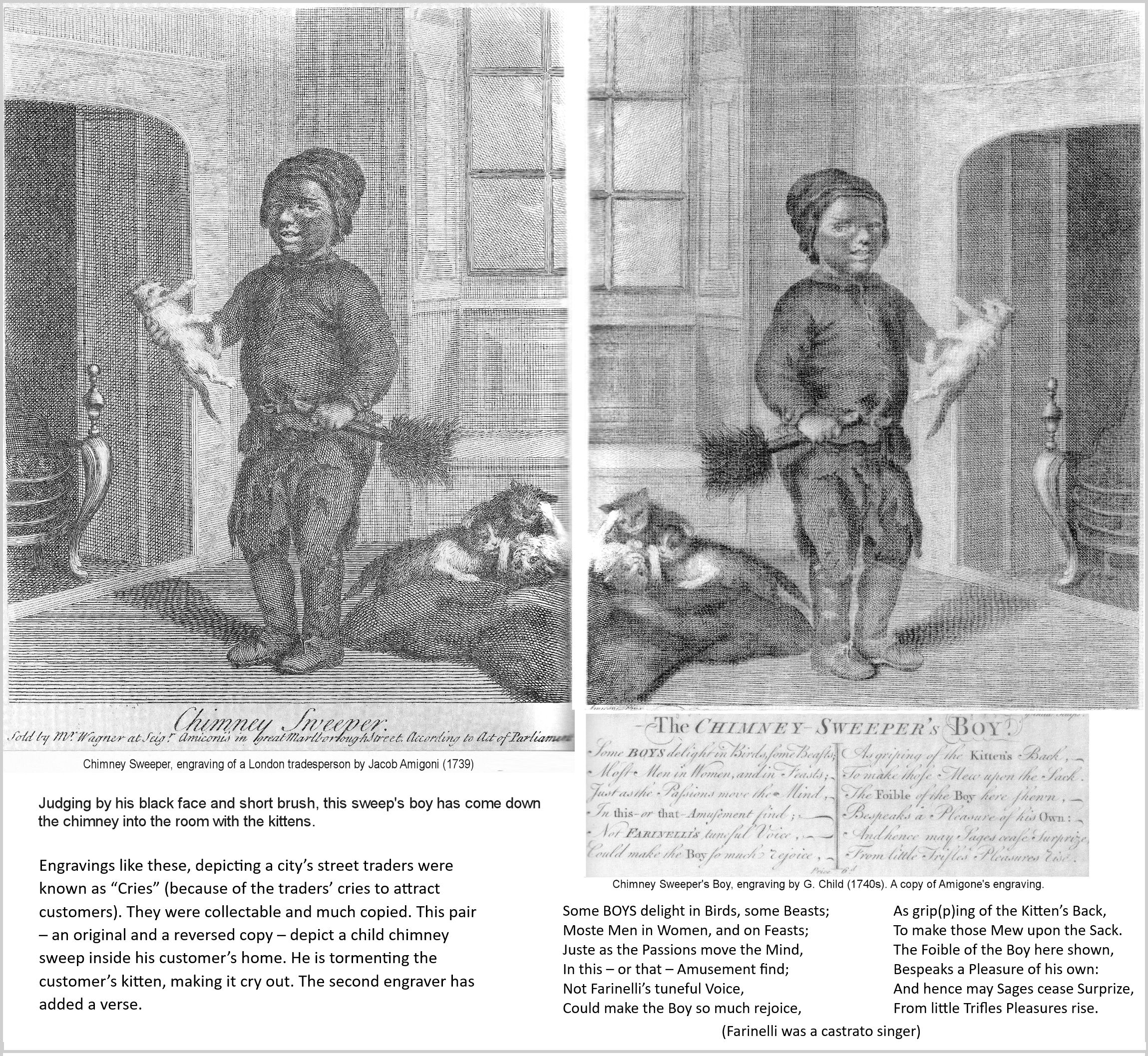

A CAT AND DOG LIFE

Pearson's Magazine (USA) September 1900

How an Animal Photographer Obtains his Pictures of Valuable Pets.

By D. T. Timins.

A love for animals is one of the distinguishing characteristics of the English people, and is beginning to be so of our own countrymen. No Englishman is quite happy when taking his walks abroad unless he is accompanied by a dog of some description, which may be anything from a thoroughbred terrier to a whole-souled mongrel, that is part mastiff, part greyhound, and part bull-dog. Similarly, no English woman considers her house to be properly furnished unless the harmless, necessary cat forms part of the appurtenances thereof. Indeed, many people are so fond of cats that they devote their entire time to breeding and exhibiting them. Cat Clubs and Cat Shows have raised up strong class distinctions among the feline race, whilst cat breeding has been studied to such an extent that a very wide gulf now yawns between the common or garden pussy of the domestic hearth and the pampered winner of a hundred prizes. Dog shows are, of course, equally numerous and even more popular.

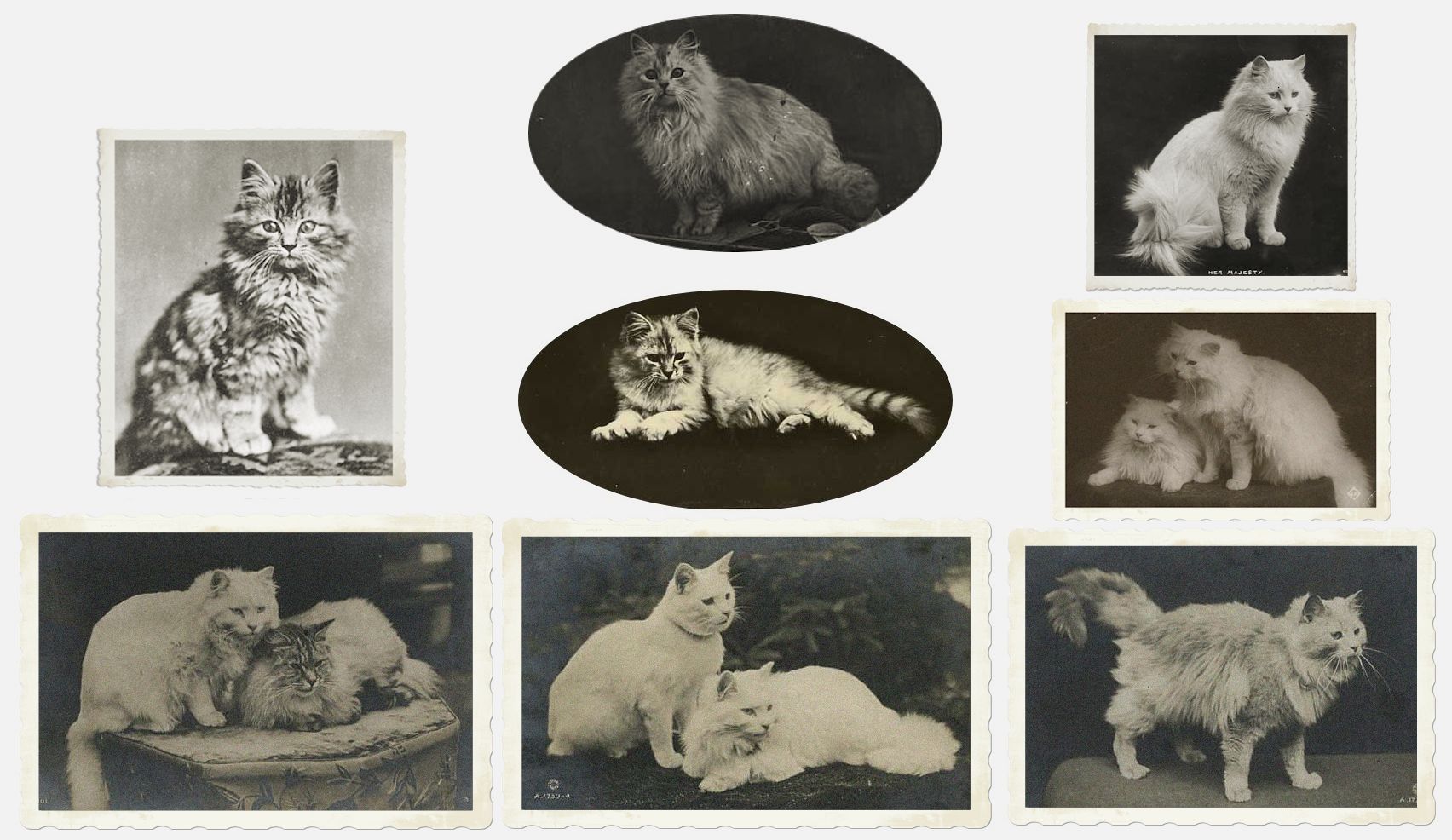

These highly-bred animals are very beautiful creatures, and it is only natural that others besides their fortunate owners should greatly admire them. If you cannot get the substance, you must be content with the shadow, and the next best things to pussy and Ponto in proprid persona' are their photographs. Hence it follows that a very great number of people who cannot keep pets collect photographs of celebrated cats and dogs. Moreover, the actual owners thereof delight in having them photographed, so that a really skilful animal photographer is very much sought after.

Cats are notoriously the most difficult of all living creatures to photograph satisfactorily, but Mr. Landor, an Englishman, after devoting many years to the study of the subject, has brought the art to a degree of perfection which we venture to think no one has previously attained. He has latterly turned his attention to the photographing of dogs with equally satisfactory results. The main difficulty in obtaining a good picture of a cat lies in the fact that its movements are more rapid than those of any other animal, consequently, the best lenses, the fastest plates, and the most brilliant light are necessary if the picture is to be a success. As the result of many experiments, the following method of photographing both cats and dogs was adopted.

In an angle of the studio, which has a large window on one side of it, is placed a settee for the animal's reception whilst being "shot." Behind the settee, if the subject be a cat, is draped a perfectly plain grey background, experience having shown that the fur stands out better from this than from any other. For dogs, a drab cloth is the best, and, if possible, no accessories are used, as they tend to make the good points of the animal less noticeable. The usual studio "top-light," is supplemented by a circle of forty electric lamps set under the rim of a most brilliant reflector, the whole being fixed to a travelling beam overhead. Working at high-pressure, these lamps yield jointly a light of 10,000 candle-power, but any smaller amount required can be obtained by means of a switch-board. Though this light is exceedingly powerful, it is barely strong enough for the very rapid exposures which must be made, consequently, as a cat can look straight into the sun without blinking, Mr. Landor prefers brilliant sun-light when it can be obtained to any form of artificial illumination.

The camera employed is simply a twin-lens hand camera, with two shutters, the one for use under ordinary conditions working in front of the lens, and the other, intended for exceptionally rapid exposures only, at the back of it. Be it here explained for the benefit of the uninitiated, that a "twin-lens" camera is, as its name implies, an instrument provided with two exactly similar lenses one above the other. The lower one takes the photograph, whilst the upper one is only used for focussing purposes. The great superiority of such an arrangement over all others lies in the fact that it is possible to focus the object to be photographed up to the very second of making the exposure. This is an enormous advantage in the case of restless animals, for they can, within reason, move as much as they like "without affecting the sharpness of the resulting picture.

But when all necessary preparations have been made, the cat is still more or less master-or mistress-of the situation, as the case may be. Valuable animals, which have been much spoilt and pampered, of course, give most trouble. They are usually brought to the studio in a basket, and upon being liberated often bolt straight for the chimney - in fact, this has taken place so many times that the fireplace is now specially protected.

If, however, the cat condescends to allow itself to be placed on the settee, it immediately settles down into as awkward and ugly an attitude as it is possible for such a graceful animal to assume. There it remains a sulky and inert lump of fur, whilst Mr. Landor consumes the next twenty minutes or more in making use of every conceivable blandishment which a true lover of cats can think of to induce it to sit up, as that is the best possible position for showing off its good points to advantage. With almost human perversity the cat often absolutely declines to move, until in despair of coaxing it to do so a number of plates are expended on it whilst still recumbent. The operation being then completely finished, the cat will of course immediately sit up as good as gold.

In some cases it has been found necessary to stroke and caress an animal for as much as an hour and a half before producing any effect, but, finis coronal opus, at the end of that time the cat, in a moment of friendliness, sits up, and, hey, presto! the shutter is released and the picture secured. On the other hand, some pussies seem to delight in being photographed, and wear a look of mingled affectation and conceit on their countenances which could scarcely be equalled. In any case, at least half-a-dozen plates and sometimes a great many more are exposed on each subject, with a view to securing the best results.

Old female cats, soured by contact with the world, and rendered cynical by a long contemplation of the universal faithlessness of Toms, are the worst subjects of all. They remain deaf to the voice of the charmer, and delight in arranging themselves in such away as to render it a matter of extreme difficulty to distinguish their heads from their tails. Young cats are easier to deal with, but kittens, which reach their prettiest stage of growth when two months old, are very difficult subjects to manage, though it is fairly easy to secure a favorable expression, as they take an intense interest in the small toys which are always used to attract their attention.

White cats are very hard to pose properly. As most people know, they are stone deaf, and for some reason or other this infirmity seems to be responsible for the fact that when brought before the camera they refuse to betray even the most languid interest in the proceedings. However, Mr. Landor being a keen student of cat nature, and well versed in the practice of every possible wile for obtaining his end, usually succeeds in overcoming their lethargy. But the difficulty of photographing single cats is as nothing compared to that of dealing with groups. The central idea of the scene is, of course, determined beforehand, but it is much modified by what the cats and kittens will or will not do when they are being placed in position. Sometimes they actually improve on the original design of the picture by their antics.

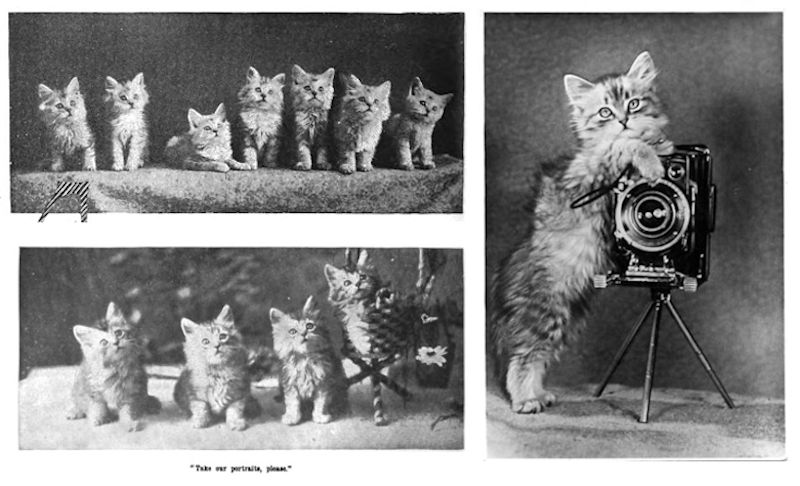

Mr. Landor considers that he achieved his greatest triumph when he succeeded in photographing no fewer than seven kittens in a row. The labor involved in arranging "the group was immense, for he wished to make the kittens stand up rather close together. But the attraction which the waving tail of each one possessed for the remaining six seemed to present a well-nigh insuperable obstacle. At last, however, he managed to induce them to remain reasonably quiet for a second or two, and also to all stand up simultaneously, a piece of good fortune for which he had scarcely dared to hope. But almost at the very moment of exposure one ball of fur decided that its four stumpy little legs were unequal to supporting their burden any longer, and sat down incontinently. The artistic beauty of the picture is, however, greatly enhanced by this seeming misfortune, for the break in the line made by this rebellious kitten's attitude is most effective. Mr. Landor has tried similarly to photograph nine kittens, but so far he has not succeeded. Let anyone try to make even two playful Persian kittens stay in any given position for more than twenty consecutive seconds, and he will have some idea of the task which that gentleman has set himself to accomplish.

Dogs are, on the whole, much better behaved. They are much easier to make friends with, and can be commanded to keep still, whereas a cat must invariably be coaxed into submission. Nevertheless, some dogs quite unintentionally give a tremendous amount of trouble. For instance, the tails of retrievers seem to be endowed with the power of perpetual motion, no matter how docile the dogs themselves may be. Moreover, a dog has more points which must be brought into prominence than a cat, and its attitude is of correspondingly greater importance. Toy Pomeranians are particularly difficult subjects. A sharp noise is the best means of attracting a dog's attention when an exposure is about to be made, as it usually causes him to shut his mouth, for, even when not thirsty, dogs are much given to panting whilst being posed and focussed and, of course, cannot be successfully photographed with their tongues hanging out. Groups of dogs are easier to pose than groups of cats, and naturally big dogs are better subjects than small ones, for they are not so restless.

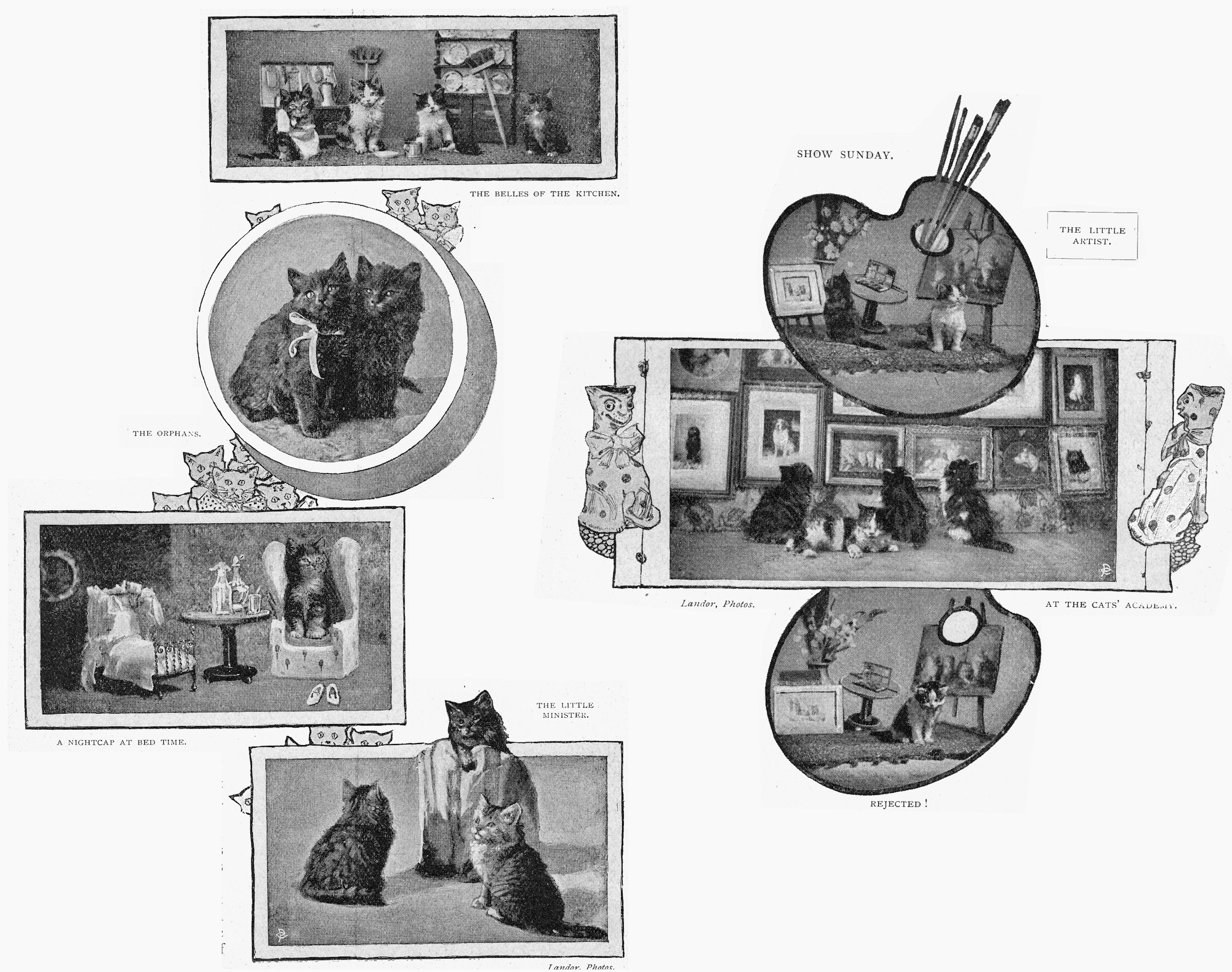

The titles of the photographs, of which, by the way, there are already over 200 series of cats alone, have had something to do with the popularity of the pictures, for they are very aptly chosen. As an instance we may mention the photo of the black and white kitten reproduced on the preceding page, which has enjoyed a great popularity, not only because it is an exceedingly clever study, but also because its title, "A Study in Black and White," is so peculiarly appropriate. Mr. Landor by no means confines his attention exclusively to domestic animals, but has recently made a number of studies of birds, wild beasts, etc., etc. Not only has he laid the English Zoo under contribution, but also those at Rotterdam, Amsterdam, etc., and has obtained some most successful photos.

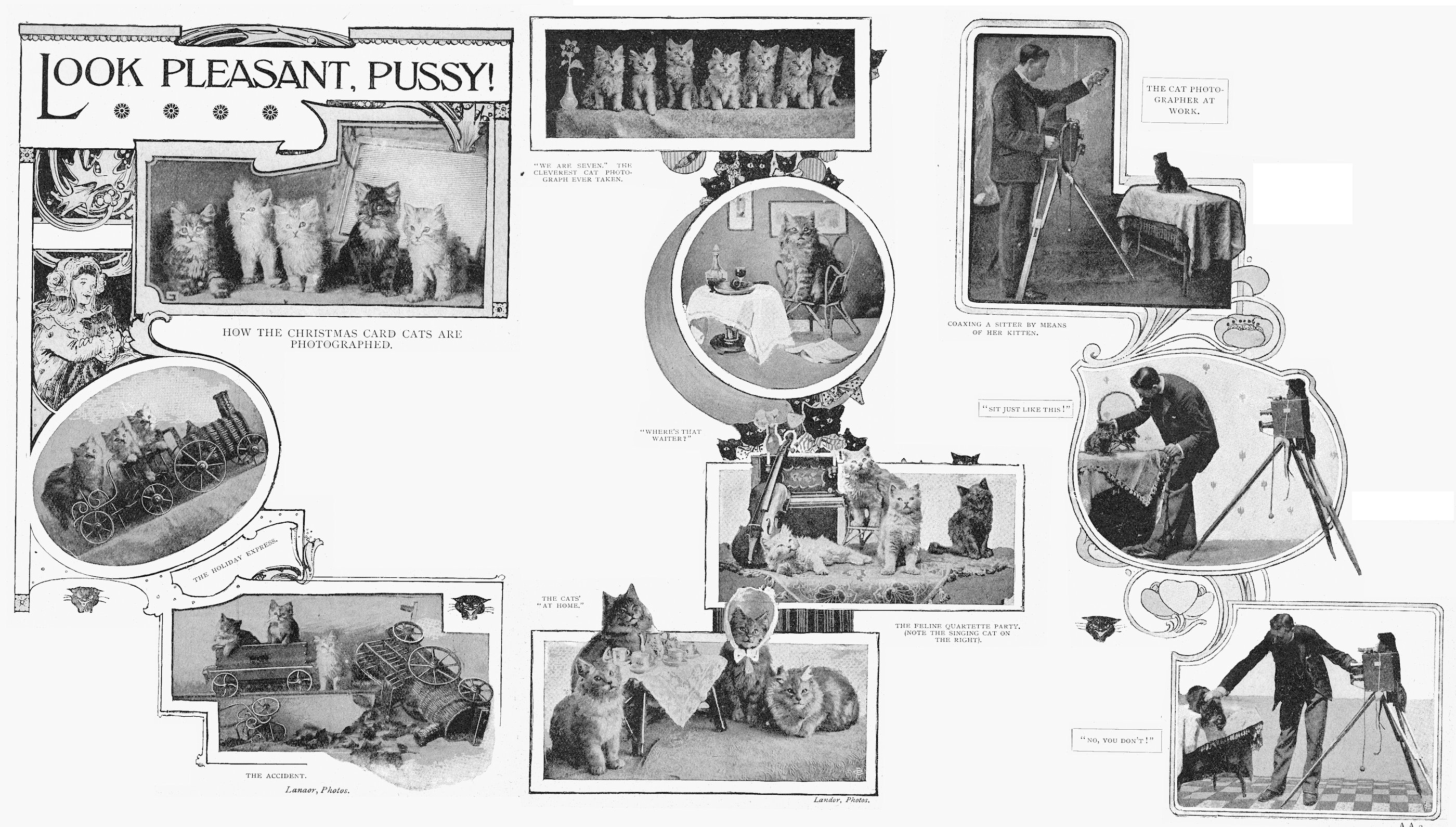

LOOK PLEASANT PUSSY. HOW THE CHRISTMAS CARD CATS ARE PHOTOGRAPHED.

Harmsworth Magazine, No 40, Vol 7, 1901, pp321

Many of our readers have received at one time or another Christmas cards bearing charming pictures of kittens. Most of the originals of these artistic productions are the work of one clever photographic artist, Mr. E. Landor, of Ealing, whose method of work is described in this article. Mr. Landor is a bright young man, who, after a few years' experience as a general photographer, saw that the real road to success lies in striking out a new path for oneself. It happened that a near relative of his was an enthusiastic cat fancier, and, naturally enough, wished to possess some permanent memorial of her successive pets. So Mr. Landor undertook to photograph them, and after many attempts, succeeded in obtaining some very charming studies. These were not only greatly admired by friends, but were readily accepted by the editors of various illustrated magazines, and he found that he had hit upon just the new line he was seeking. So rapidly did the demand for cat studies grow, that for some time past he has given up ordinary studio work, and now devotes himself exclusively to animal photography.

When we called at Mr. Landor's establishment at Ealing, we were fortunate enough to catch him at a happy moment, for he was busily engaged with a couple of cat sitters if the term may be applied to animals who were determined, whatever else they did, that they would NOT "sit." They were a couple of half-bred Persians, and were obviously in an aggravated state of offended dignity. Our well meant blandishments and-soothing remarks of "Poor pussy" and the like were rejected with scorn and contempt. One was a black cat of mature age, who sat on an ottoman in an attitude of blank despair, and simply sulked. The other had a young kitten with her, and was chiefly occupied in a persistent search for a suitable hiding place. Two more unpromising sitters would have been hard to find, but Mr. Landor assured us that it was the difficulty that lent zest to the task.

At one end of the studio, in front of the usual background screen, stood the small table on which the feline sitters, had to pose. Facing this, on a tripod stand, was a camera altogether unlike that which is usually seen in the photographic studio. It was what is known as a twin-lens camera, being, in fact, two cameras, one above the other, and so adjusted that the cats could be watched on the ground glass screen of the upper one, white the sensitised plate in the lower one was ready to receive the impression when the moment came for taking the photograph. This camera, which owes certain special features to Mr. Landor's inventive genius, is admirably adapted for its purpose, for it enables the photographer to see exactly the image that is thrown on the plate at the very moment of the exposure. It is thus possible to focus accurately without having to disturb the camera.

The chief business is, of course, to pose the sitter. Sometimes, especially in the case of young kittens, the trouble is to keep the animal from moving, but in the majority of cases the cat, after a few abortive efforts to escape, begins to sulk and settle down, into an attitude of pathetic misery. Now a glance at the illustrations appearing in the present article will shew that their charm is due in a great measure the bright and intelligent expression of the animals. In order to secure this, it is necessary to arrest the cat's attention, and to arouse her curiosity. This can seldom be done by talking to her, for the more one tries to coax, the more she sulks. The best plan is to arrange some slight noise or stealthy movement, suggestive of a mouse or small bird. Unless the cat is very old or exceptionally sulky, this rarely fails to put her at once on the alert. Her ears go up, her eyes open wide, and she is all attention in a moment. For two or three seconds she will probably remain quite motionless, watching and listening attentively. During that short time the photograph has been taken.

Mr. Landor's favourite instrument for arousing the interest of his sitters is simply a short stick with a bunch of long waving dried grass tied to its extremity. When this is stealthily but jerkily drawn across a screen so as to produce a subdued rustling, all pussy's faculties are at once on the alert. A child's rattle, a squeaker, and a small bell are also occasionally used, but none, of them is equal to the rusting grass. When we were at the studio, Mr. Landor tried to arrest the wandering eyes of the younger cat by holding up its kitten. This proved a complete failure, for the; mother promptly sprang off the table and rushed to the rescue of its offspring.

It needs to be remembered that the photographer has not only to get the cat into the desired position, but to keep it there sufficiently long for the photograph to be taken. It is rarely possible to take an instantaneous snapshot photograph in a studio, as the light is not sufficiently powerful. Usually, an exposure of about a second is needed to give a good result. Needless to say, it is seldom possible to take cat photographs out of doors - the opportunities for escape are too numerous. We tried the experiment, but the time was mostly occupied in circumventing spasmodic dashes for liberty on the part of our subjects.

When a group of cats is to be posed and photographed the difficulty is immensely greater. Putting the thing in scientific form, one may perhaps say that the chance of success varies inversely with the square of the number of cats. If it is hard to get one cat to sit properly, it is infinitely harder to pose several. You get one of them into a good position, and then discover, to your horror, that the other has quietly slipped off the table. A group of young kittens is, perhaps, the most perplexing subject of all. The natural skittishness of feline youth is never so thoroughly realised and so heartily denounced as by the harassed photographer.

Mr. Landor regards as his greatest triumph the charming photograph of seven little, kittens sitting in a row and gazing intently upwards. (See page 322). It was only after an almost endless series of attempts that the entire seven kittens were caught looking up at the same moment. The artist breathed a sigh as he thought of the great heap of wasted dry-plates that this one particular photograph had cost him. In fact, the work of a cat photographer is continual series of disappointments and vexations. Tails are a perfect nightmare to him, for when all else is right and what is apparently a good photograph has been secured, the development of the negative reveals the fatal fact that one of the cats twitched her tail at the psychological moment and completely spoilt the picture!

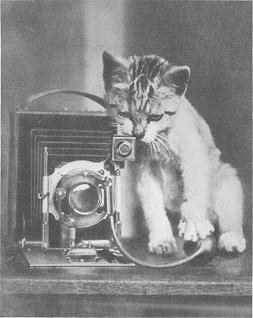

The particulars given in this article will lend an added interest to the photographs of delightful little kittens that Mr. Landor's courtesy permits us to reproduce. What could be happier than the studies of the little artist that we give, on this page! The look of expectant triumph on the kitten's face in the first photograph contrasts admirably with its dejected air in the third. This was accomplished by first shaking the bunch of dried grass high overhead and then drawing it gently along the floor. The feline quartette party is another of Mr. Landor's most successful studies. This is probably the only photograph in existence that shews a cat singing! It certainly looks wonderfully natural, but perhaps we shall not be letting out any State secret if we hint that a lucky yawn at the right moment was responsible for the effect!

Of course, in the majority of cases the cats were carefully posed by the photographer with a view to a preconceived arrangement that he had in mind, but in many instances the mottoes which fit so appropriately were added subsequently to groups which were in a great measure the result of chance movements on the part of the kittens themselves. But whether they are the results of careful posing on the part of the artist or otherwise, it will be pretty generally admitted that the groups of kittens possess a distinct charm of their own, and form most desirable Christmas cards.

CAT PHOTOGRAPHY FOR AMATEURS (1903)

All lovers of the cat who are also amateur photographers must have seen the lovely cat pictures by Madame Ronner [a noted Dutch artist of the time], the more racy [in 1903 this meant "lively"] and amusing sketches by Louis Wain, and the many photographs which so greatly enhance the instructive and pictorial value of this "Book of the Cat". To the amateur wishing to take up this fascinating, though somewhat difficult, branch of photographic art, I venture to offer a few suggestions.

The subject naturally divides itself into two branches - the commercial and the artistic. By the "commercial" I mean all photographs taken with the special aim of showing the shape and points of the cat from the fancier's, owner's, or purchaser's point of view. In the "artistic," I include all those pictures where the cat is used as a model only.

In either kind of work almost any sort of camera and lens will do, providing it will yield a fair definition and admit of rapid exposures. If one possesses a portrait lens all the better. At all events use a lens which will give you good definition at a large aperture. A good make of roller-blind shutter is an important accessory, with a sufficient length of tubing to the pneumatic release to enable one to move about freely while holding the ball and to get close to the cats while making either time or instantaneous exposures. The camera stand should be very firm and rigid.

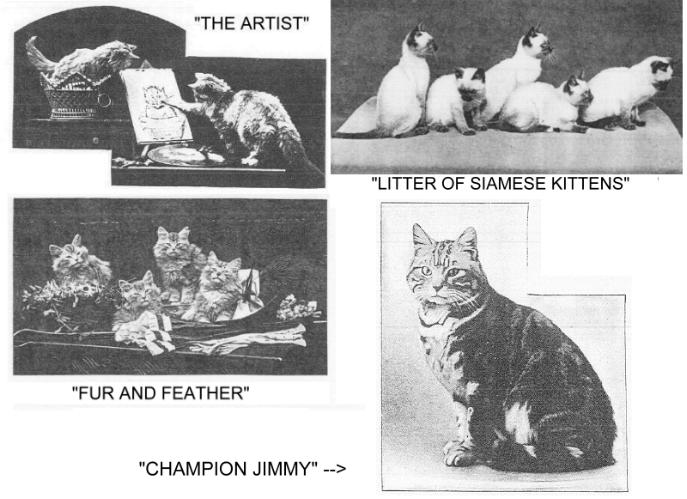

I like best to work in the open air, my studio being the small open run of my cattery. If the light is too direct or strong I diffuse it by stretching light blue art muslin curtains above the table or stand upon which the cats are arranged. These curtains run with rings upon cords stretched from the boundary walls on each side so that they may be moved in any way the lighting may require. For background a dark plush curtain will be found useful. Avoid figured backgrounds, as they detract from the value and crispness of the cats and accessories [props]. An example of what I mean will be seen in my picture on page 158 of the present work ["Fur and Feather" photo], where the feathers in the hat, one of the motives of the composition, are almost lost in the scrolls of curtain used for background.

Three things are absolutely necessary to successful photography of cats for either commercial or artistic purpose - time, patience, and an unlimited number of good quick plates. Of all animals the cat is possibly the most unsatisfactory sitter should we attempt by force to secure the pose we desire. By coaxing we can generally get what we wish. Patience is the keynote of success. Before commencing, make up your mind as to what points you wish to show; then pose your cat gently and wait patiently until the pose becomes easy. She may jump down or take a wrong pose or go to sleep a dozen times or more, but never mind, give plenty of time. It is here where patience tells. Wait and coax until you see just what you desire, then release the shutter and make the exposure. At this point never hesitate or think twice - especially with kittens - or the desired pose may be gone, and will possibly cost you hours of waiting again to secure it.

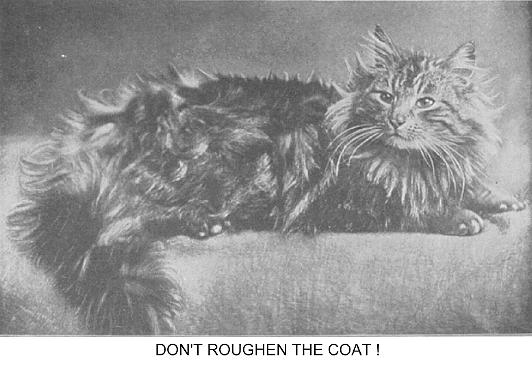

Before photographing a cat for its general appearance or for any special points, it is essential to have it thoroughly groomed and got up as carefully as for show. Speaking generally, the coat of a long-haired cat should never be roughened; it altogether spoils the shape of the animal, and does not in any way improve the appearance of length, quality, or texture of the coat. In all cats where their markings are one of the chief points - such as tabbies and tortoiseshells, etc - this roughening should be specially avoided. There is, possibly, one exception to this advice, and that is in the case of smokes, where it may be, and sometimes is, desirable to turn back a small patch of the fur to show the quality and purity of the silver under-coat. In such cases, the turning back must be done only for this purpose, and in such a natural way as not to interfere with the general flow of the fur of the shape of the cat. In posing a cat, it is well to remember its faults as well as its good points, so that the former may be hidden as much as possible and the latter displayed to the best advantage.

Let us take this somewhat extreme example: A friend has a domestic pet - a so-called Persian, but with weasel head, long back legs and tail, large ears, small eyes, short coat, but some slight pretence to a frill. What can we do? To take him in profile will result in a very sorry caricature of the noble Persian; so we coax pussy to bend her back by sitting on her hind legs, and so partly hiding them as well as apparently shortening her back, inducing her also to curl her long and scanty tail round her feet. We brush out the ear tufts, if she has any, and press up the fur at the base of the ears, for this will tend to make them look smaller. Having placed the camera well in front of and nearly on a level with the cat, so as to foreshorten the nose and head, while showing what frill there is, a sharp squeaking sound will make pussy open her eyes to their full extent; we press the ball, the exposure is made, and we have secured a fairly presentable photograph of our friend's perchance charming pet, yet most indifferent Persian cat.

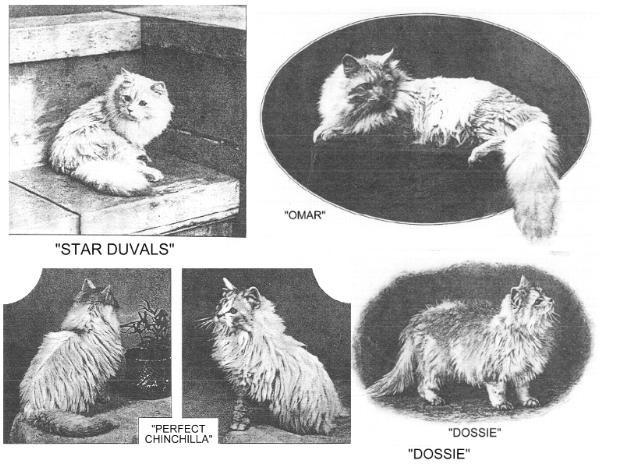

A few good examples of cats taken for the purpose of showing points should prove useful, and many such examples can be found in this present work on the cat - for instance: p. 29, "Litter of Siamese Kittens"; p. 100, "Champion Jimmy"; p. 138, "Star Duvals"; p. 139, "Omar"; p. 145, "A Perfect Chinchilla"; and p. 150, "Dossie." With these examples and the many others that are to be found scattered through the pages of "The Book of the Cat," the would-be photographer of the cat for show points should have little difficulty in setting up a standard to work to, and by patience and perseverance succeed in attaining it.

Turning now to the more artistic side of cat photography, we find our real difficulties begin, for in photographing for the showing of points we seldom have to deal with more than one cat at a time. It is when we attempt deliberately to pose two or more cats or kittens, to carry out a preconceived idea, that our real troubles begin, and also that the patient skill of the amateur wins its best reward. Looking through the plates of "The Book of the Cat," we find many examples of how the cat should be used in picture making. The reproductions of Madame Ronner's charming pictures show how they may be handled with palette and brush; but, alas! here we photographers labour under an immense disadvantage. However artistic our taste, however good and pretty our intended composition may be, we cannot, as the artist with pencils and brushes can, make individual sketches of pussies in the different positions needed and bring them together in the finished picture. Whether we use two or more cats, they must each be kind enough to take the pose we desire simultaneously; hence our greater difficulty. However, the illustrations on pages 1, 37, 49, 88, 128, 199, and many others indicate the wide field open to the photographer with a little taste and vast patience. In this class of photography it is of no use to go to work in a haphazard fashion, snap-shotting our cats in all kinds of positions, trusting to mere luck to yield something worth keeping; then to give sounding title to it, and so hope to make a picture. Accident does occasionally present us with something worth having, but far more often it offers us results only fit for the waste-paper basket.

Before commencing, be sure you have an idea to work out in your picture, and of the lines you hope to follow in giving expression. If possible, make a rough sketch - no matter how rough - of this idea, showing the position not only of the cats, but also of the accessories needed. Be careful to keep the composition simple and not to overcrowd it. This sketch will greatly assist you in arranging your picture and posing your cats. Before you attempt to pose the cats it is absolutely necessary that all accessories should be fixed so that they cannot be knocked over, or the cats will get frightened and be useless as sitters for a long time to come. That cats are nervous should never be forgotten, and any chance of startling them strictly guarded against. When your background, table, and accessories are all in their place, put your camera in position, arrange the picture on the ground-glass, and see that you get all well within the size of the plate; it is safer to have the picture on the ground-glass a little smaller than the plate will allow, as if one tries to get it to its utmost size, one may find in developing that one of the models has moved back on the table an inch more, perhaps, than calculated upon, and as a result have half a cat on one side instead of a whole one. The background, however, should be large enough to fully cover the ground-glass. Focus the foreground and nearer accessories, stop down to F8, set the shutter to about one-thirtieth to one fiftieth of a second (according to light and nature of subject), insert the slide containing the rapid plate, draw the flap under the dark cloth, and if at all windy tie this last to the camera. Now you are ready for the cats and a suitable moment of light.

As I have already remarked, I do my photographing out of doors. I therefore choose a bright warm day, when there are plenty of fleecy clouds about; so that by taking advantage of their position in front of the sun, and by the help afforded by my muslin curtains, I am able to modify the harsh contrasts incidental to working in broad daylight.

"The Artist" (page 128) was, perhaps, one of the most difficult subjects I have attempted. Without apparent life and go such a subject would be worthless. The rough sketch of the cat in the basket was first prepared, and the brush attached to it in such a manner that it would move freely up and down for about an inch or so; then it and the rest of the accessories were firmly arranged upon the table. The cat in the basket was then made to take her place, but keep in she would not; as soon as the brush moved to attract the artist paw, out she would jump; so for the time she was allowed to run until the artist was posed and an endeavour made to infuse life into him by moving the brush. But it was "no go"; sit down he would until the introduction of a feather woke him up. His companion was then slipped into the basket; but alas! success was not yet. For about two hours we had to begin over and over again, when at last the pose of both kittens was obtained simultaneously and the picture taken in one fiftieth of a second. Such a subject with the kitten tamely sitting at the handle of the brush would not in any way have realised my intention.

I must again point out the great convenience, especially in this class of work, of the extra length of tubing, which allows you, while holding the release in one hand, to pose your models with the other, and then expose without the fatal loss of time that would be entailed by having to step back to the camera or by giving the word to an assistant.

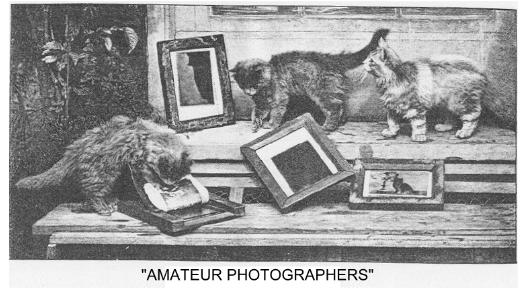

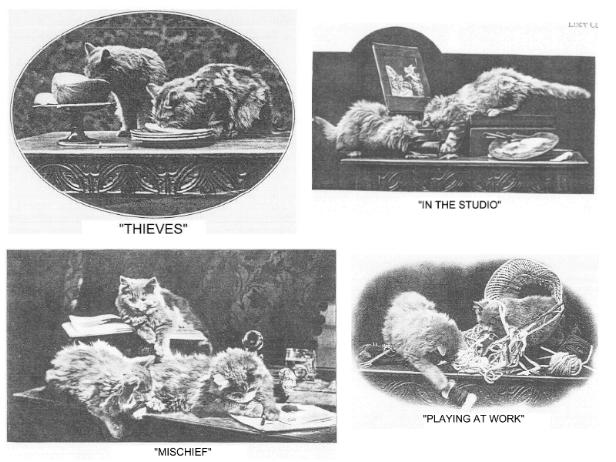

A subject suggestive of a picture will often turn up when least expected and, at the time, impossible to take. I always make a note of these and they come as a basis for future use and to be worked out at leisure. "Thieves" (page 70) was suggested by noting the fondness of two of my kittens for melon, "Amateur Photographers" by a group of kittens playing round some photo frames put out to print, and "Mischief" (page 88) by a frolicsome kitten overturning a small bottle of ink and playing with the little black pool.

Isochromatic plates should be used in all cases where there are mixed colours in the cats' furs, as in tortoiseshells, brown tabbies, etc; mixtures of red, black, and yellow cannot be truly rendered with ordinary plates. The only extra precaution necessary in their use is absolute freedom from actinic light in the dark room. Double ruby glass in the window, or if artificial light is used, an extra thickness of red tissue paper round the developing lamp, will answer this purpose and make everything safe. With this little extra care, nice crisp negatives are obtained, while the relative value of the red, yellow, and black seen in our furry friends are well defined in the resulting picture.

Cats used as models should, if possible, be in the pink of condition - the prettier the model the more pleasant the picture. The best time to photograph a cat is about one hour after a light meal. Immediately after a meal most cats want to wash and sleep. A hungry cat or kittens makes the worst of sitters; its thoughts are too much turned towards the inner man. Never overtax your cats, give them plenty of rest during a sitting, and never lose your temper and attempt to force to secure a pose; it only frightens the cats, and can never result in satisfactory work. Time and patience should always in the end achieve what you desire.

Artistic photography having been for some years a pleasant and recreative hobby with me, I can assure my friends who keep cats for pleasure, and those who find pleasure in the camera, that by uniting the two hobbies they will discover a field of enjoyment and artistic possibilities which neither pursuit alone can afford. To all such the preceding notes are offered as humble finger-posts, indicating rather than assuring the road to success.

FASHIONABLE PETS BEFORE THE CAMERA (The Washington Times, 26th April, 1903)

The photographer of society's pets has appeared in Washington. This specialist doesn't pretend to be able to make a good photograph of a baby. In fact he shrugs his shoulders and rolls up his eyes when you speak of an infant's photograph and says something about their being all alike. But he is wildly enthusiastic on the subject of dogs and says that it is a delight to photograph a Persian kitten, for these little animals are natural models, it seems, and every new attitude is more charming than the last.

There was a time not so very long ago when the photograph of a dog might be that of a door mat and a cat looked like a muff. But all that is changed now and the quick methods of photography make it possible to secure wonderfully good pictures while the pets themselves seem to have acquired a liking for the camera.

"I have taken hundreds of photographs of pet dogs and cats in the last, year or two." said the photographer of society pets. "After the dog show there is always a boom and a cat show also results in a great rush for pictures. It used to be the thing for a lady to pose with her pet, but of late we find that we can secure excellent pictures of the animals alone. Some of them take naturally to posting and seem to understand it, for they don't move an eyelash, many of them, until I tell them they may. The dogs are the best holders of any particular post and will sit as still as a human being and much more quietly than a child.

"The cats on the contrary play around and we have to catch them in special poses. A Persian kitten is a natural model and will assume fifty graceful attitudes in as many minutes. The most effective pictures I have secured are those of the Persian cats. Of course there has been a cat fad within the past year or two, and every woman has her pet Angora or her Persian kitten nowadays. The craze came from London, where the women have been taking cats about with them in cabs and omnibuses for a year or more. The craze has never reached that state here as yet, although once in a while you may see a girl driving with a cat or even in the street cars. But cats are very popular as pets, more so than dogs, with women and we are kept busy taking their pictures. The pretty idea with a cat is to get six or eight different pictures and then frame them in a long panel passe partout. This makes a delightful picture for a nursery or a sitting room. Children are very fond of having their pets pictured by the camera and they usually wish to be photographed with them.

"We have had any number of children brought here with pet rabbits, and one brought a turtle the other day and wished to be taken with it in a group. It was difficult to make him understand that a turtle could hardly be induced to pose for a camera with any effectiveness. Monkeys we have taken, but monkeys are not popular as pets in America, although in the southern countries every household has its pet monkey, just as we have our cats and dogs. But it is difficult to get a good picture of a monkey, for it is not still long enough as a rule, and its face is always in motion.

"The French bulldogs are admirable posers for the camera. They are alert and intelligent. Their faces are full of expression and sharpness and their lines come out well. A thoroughbred animal never shows its good points so well as in a photograph, if a good pose is secured. But photographers, for some reason or other, have never given this branch of their business much attention.

"It was the amateur photographer who first discovered how admirably pets could be made to sit for a picture, and the best photographs of this sort were taken by amateurs until we began to give the matter our study and attention. But at fashionable studios there used to be a dislike for photographing pets for the reason that the results were not apt to be good. They frightened a cat or a dog into a nervous state that made it wish to escape the moment it entered a studio. We get our sitter to feel at home the first thing by giving it a saucer of milk or a chicken bone, and after a little play it becomes as tractable as a child. It is stage fright that makes had pictures with babies and grown persons, just as it does with animals, if they are pushed at once into a chair and the picture taken before the mood of repose has asserted itself.

"I know of photographers who, in their endeavors to make a patron assume some posture that may be entirely unnatural, bring on a fit of nervousness that is almost hysteria. They keep turning the head this way or that, bending the neck or the elbow in a certain direction until the sitter is in torture. A human being will stand this sort of thing, but an animal will not, and we have to use gentle and subtle methods in order to get the best results.

"We make up the animal pictures by the dozen and some of them are very handsomely mounted. The studies of expression in the different faces are wonderful. There are serious dogs and coquettish kittens, vain Angoras and splendid kingly St. Bernards. Of course, our sitters as a rule are the thoroughbreds of their class and this is the reason, perhaps, why they are so well behaved. We rarely have any obstreperous models and no quarrel has as yet interfered with the harmony of our studio."

FELINE PHOTOGRAPHY.

By F. J. E.

The Queen, 13th August, 1904

IT IS PROBABLE that few animals are so utterly impossible to take as cats, especially the fashionable smoke-grey Persian variety. A dog may look depressed and give the idea that he is a sort of martyr, but in his case there is some intelligence to go on. A dog will do as he is told in most instances, which a cat will not. The annoying part is that cats are the most perfect studies for the camera by reason of the graceful attitudes they assume. The great difficulty is to be quite quick enough to catch the changing positions successfully. There is one point in the photographer's favour; cats do not seem to get "camera shy" as dogs do. The activity of a cat is sheer mischief, not fright, as in the case of the nervous canine. The orthodox way to get cat photographs is to place the victim on a table and then attract attention by the agency of a bit of fish or meat. A likeness results; it cannot strictly be called a picture, except in those cases when the natural beauty of the subject saves the situation. But to get cats in a really natural attitude the same procedure has to be followed as in the case of dogs - that is to say, they must be very carefully snapped. One of the "Naturalistic" or a twin-lens camera is best to use, for the reason that a cat is a very small object, and if taken at the infinity range of the lens the picture will be so microscopic as to render considerable enlargement absolutely necessary. For this work also a light tripod is essential, as the rapid movements, if followed by the camera held in the hand, are apt to cause a nervous shakiness which spoils the sharpness of the picture. As far as my experience goes, cats mind a tripod quite as little as a camera. In this work fast plates are an essential. Not only the form and expression of the cat have to be studied, but also the texture of the coat. There, again, "blue Persians" are tiresome, as the grey coats are apt to come out a rather featureless white. It is a case of a rapid shutter; either a T.P. Special or a focal plane, and a large stop in the lens, then careful after-treatment. The best plan is to get the range of the cats as they play about, and then wait patiently for a shot. It is a mistake to let anyone fuss about or try to coerce them Into position, this only flurries and upsets the subjects, rendering good pictures hopeless. As in the case of dogs, personal sympathy goes a long way towards success. Once on friendly terms with the animals, almost anything can be done. Amateurs have a great advantage over professionals where animals are concerned, as they are able to give more time to getting a really natural and pretty picture. The question of a suitable background needs to be carefully thought out. For grey cats a dark setting shows up the colour and texture of the fur better than anything else. - F. J. E.

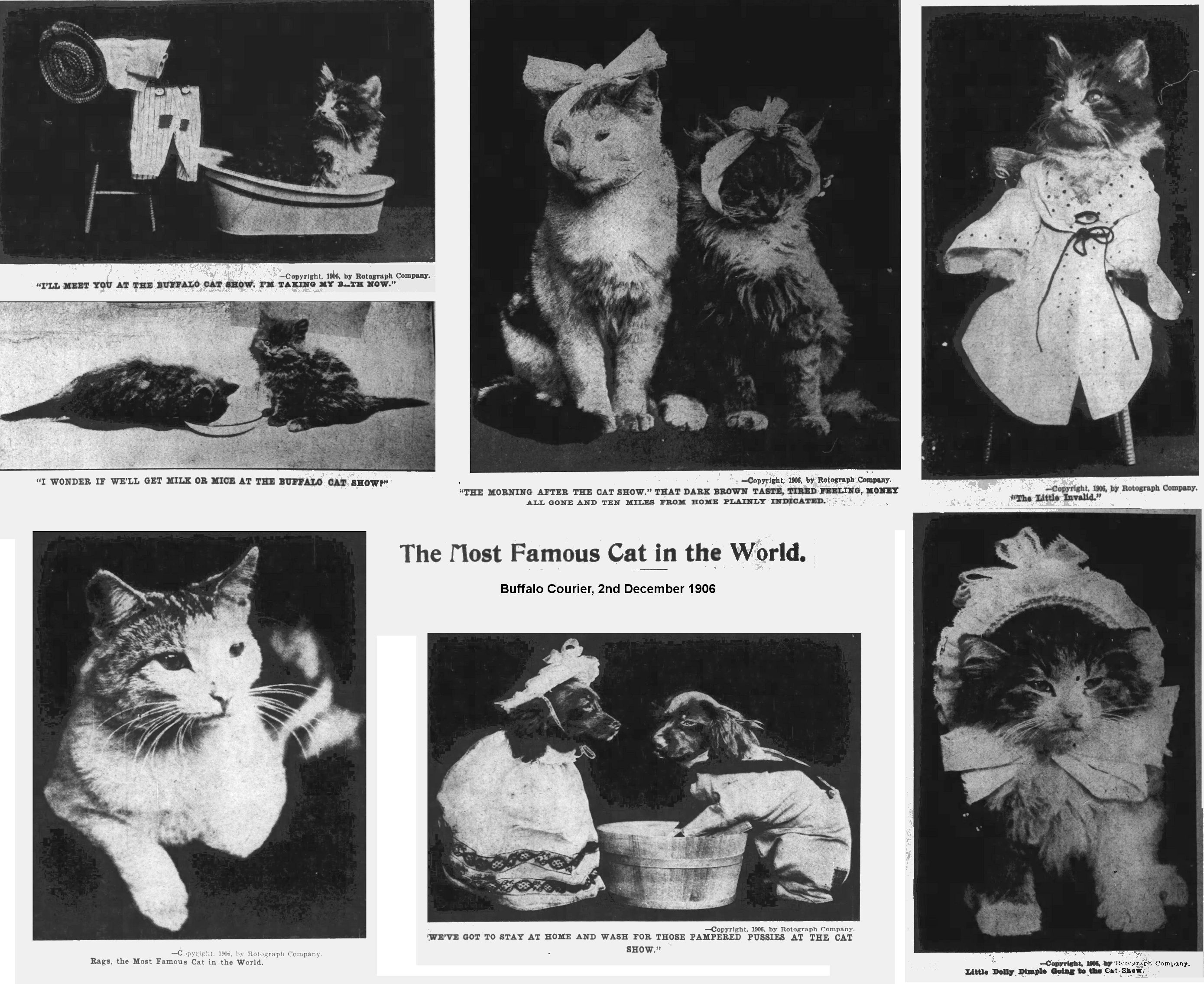

THE MOST FAMOUS CAT IN THE WORLD

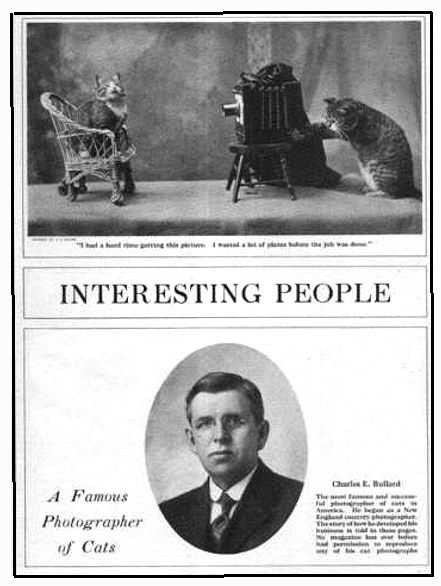

Buffalo Courier, 2nd December 1906

There are probably very few people who have not sent or received a number of pictorial postcards during the past few years following their introduction into this country from Europe. The postcard craze as it exists today claims a greater number of devotees than any other similar expression of popular fancy in the past. The best criterion of its remarkable growth is found in the fact that stores devoted exclusively to the sale of postcards are being successfully conducted in the larger cities. The distribution of this class of mail matter has already become one of the serious problems of the Postal Department. The New York office alone handles as high as two hundred thousand cards a week.

It is perhaps unnecessary to state that there is great competition existing between the different companies producing these cards to bring out a popular line of original subjects. Among the many millions of cards issued annually, representing tens of thousands of subjects, none have met with the same measure of success as that accorded the animal pictures photographed by Harry W. Frees, a young man of Reading, Pa., who recently made a contract with the largest postcard firm in this country for the exclusive control of his output for a term of years.

The hundred or more pictures comprising this series have been pronounced by competent critics as the most wonderful collection of animal pictures ever taken. They are not only charming studies of cute and original poses, but in many instances a humorous touch has been added that have rendered them doubly irresistible. Only one who has had personal experience in the art of photography is in a position to estimate what tremendous difficulties are associated with the production of good animal negatives. In order to obtain animal studies of any value it is necessary to develop considerable perseverance and great skill.

The interesting pictures illustrated here, and which were taken especially for this article, show us the spoiled darlings of the animal kingdom - charming little kittens, cute and amusing puppies, and a bold little chick in warrior guise. To obtain these perfectly natural pictures, extraordinary patience combined with rare dexterity, artistic sense and love of the occupation are essential on the part of the photographer. The story of Mr. Frees' methods in handling the little animals with such captivating results will no doubt prove of interest. His taking up of this branch of photography was purely accidental. A miniature sailor hat furnished the inspiration. One day, in a spirit of fun, he tried it on the family cat, and the result was so inexpressibly funny that he decided to have others made and photograph puss in the different poses.

From the day that these pictures were placed on the market they have steadily grown in popular favor and have scored a distinct hit wherever introduced. Since his first attempt in this line Mr. Frees has taken pictures of puppies, kittens. rabbits, chicks, ducklings, guinea-pigs, etc. His kitten pictures, however, are undoubtedly the most popular. There is something about a cute little kitten that appeals more strongly to the average feminine heart than the young of any other animal. As women are the largest purchasers of post-cards, this is probably why this class of subjects has had the largest sale.

Quite a number of people have asked Mr. Frees in all seriousness whether he does not mesmerize the animals or cast them under some hypnotic spell before taking their pictures. They are utterly unable to understand how some of his subjects can be produced without resource to some stupefying influence of this nature. It is simply a matter of gentleness and kindness, and Mr. Frees takes especial pains to cultivate the confidence of his little friends from the moment he receives them. In a few days after receiving little chicks they will jump on his hand, climb up his arm to his shoulder, and nestle against his cheek, chirping meantime in the most contented manner.

It is really remarkable how tame little chicks will become after they become thoroughly acquainted with their master. Among one of Mr. Frees' broods was a little black and white youngster who was more than ordinarily tractable in this respect. After the downy little fellow had outgrown his usefulness for pictures, he was transported to the greater freedom of a suburban home. But here he was not so fortunate as his brothers and sisters, who were all a pure white in color. No doubt his foster-mother, a staid old hen who had raised numerous families, decided him as an alien who was not to be tolerated. So when nightfall came little Pete was promptly excluded from cuddling under motherly wings. There was only one thing to be done, and the little outcast soon found himself snug and warm in a basket under the kitchen stove. From that time forth Little Pete would not deign to notice the remainder of the flock. No doubt he thought that he had graduated to a higher and more desirable station in life. He wandered joyfully over the lawn all by his tiny self. Frequently during the day he would come walking unbidden into the kitchen searching for his master. He knew his name perfectly well, and would come running like a little dog whenever he was called. One day his master started on a visit to a nearby neighbor, and while walking down the road heard a decided chirp in his rear. He turned about, and there was Little Pete following sturdily behind. The venturesome little fellow continued his journey in his master's coat pocket.

The above is cited merely as an illustration of what can be accomplished with the very young if they are given a great deal of attention. Mr, Frees spends a large part of his time with his little models and is constantly talking to them. Of course they do not interpret his meaning, but the sound of a voice soon inspires confidence, and little chicks only two weeks old will turn their heads to one side and listen attentively. Consequently when he takes their picture he is able to hold their attention simply by talking to them. If he seats himself for a few minutes where his kittens are playing, he will have a half dozen or more of them climbing all over him in an instant. He never frightens them in any way, and for this reason is able to handle them as he desires.

Mr. Frees has quite a fund of amusing experiences in connection with his animals. One day he received a quartette of young rabbits from a dealer in pets. He had some idea of the voracious appetite of these animals and fed them liberally with greens before leaving them for the night. Incidentally he inadvertently left a large head of cabbage lie on the floor, thinking to use it for fodder the next day. But his knowledge of bunnies was considerably broadened the next morning, when he found the head of cabbage completely consumed, together with several armfuls of hay that was to be used for bedding. That they left the box intact in which they had been shipped might be considered in the light of a miracle.

The majority of Mr. Frees' pictures are given a full second exposure. While this is a very short interval of time, relatively considered, yet its unusual duration can pe better appreciated by the fact that most animal pictures taken are snapshots timed from one fifth to one two hundred and fiftieth of a second. During the second of exposure any movement of the animal in the slightest degree will mar the picture. In a snapshot it is different. The lens registers the likeness so rapidly that any ordinary movement is too slow to be caught.

Quite a number of these pictures have been what is commonly known as double exposures - that is, the photographing of an object twice on the same plate. These are extremely difficult to take successfully, and require a quick eye and extraordinary nicety of precision in order that the one object does not overlap the other. This is illustrated in the picture printed herewith, entitled "Everybody Works but Mother." Very few people would realize that this is one and the same dog. First the dog at the tub was taken, after which he was withdrawn, together with the tub, dressed up in the feminine finery, and photographed again in the position seen. Great care had to be exercised that the edge of the dress did not overlap the spot where the tub stood.

Mr. Frees' star performer is a cat named Rags, whose photographic likeness has had the largest circulation of any animal in the world. He displays the most remarkable intellect for a cat, and seems to enter into the spirit of a pose. If a rag is tied around his head he will take on the most distressed air, just as though he were experiencing in all reality "the cold, gray dawn of the morning after." No matter how difficult the pose, Rags will never rebel. He has been kept before the camera as long as two hours at a stretch without any attempt to jump from the stand. When the very limit of his patience has been reached he will give a protesting little murmur. A choice bit of meat and a few minutes on the ground will at once restore him to his former amiability.

Rags' boon companion is an Angora kitten called Fluff. They sleep together, eat together and go visiting together, for, while these cats may be perfect paragons of sobriety when it comes to posing, they still possess the one dominant weakness of their kind - an inordinate passion for a nightly frolic on the back fence. While Fluff's voice is rather weak as yet, owing to his youth, Rags can run the scale in a most nerve-racking manner.

For a time Fluff's master experienced great difficulty in getting him to pose. He seemed fidgety and nervous as soon as he was placed before the camera, and as soon as released would scamper away to find his friend Rags. So one day, as an experiment, Rags was put in a basket and placed on the extreme edge of the stand outside of the camera's focus. From that time on Fluff was perfectly content to have his picture taken as long as his beloved Rags was in close proximity.

Mr. Frees has often worked a half day in trying to get a single picture. His success has been a result of perseverance and close application to his work. But the knowledge that his pictures have been the means of entertaining thousands has made it eminently worth while.

PHOTOGRAPHING CATS DRESSED UP

By CARINE CADRY

The Queen, 28th December, 1907

BEING ASKED the other day, "However do you photograph cats dressed up?" and being shown at the same time an example of a very pitiable puss sitting on a sofa dressed as a granny, also finding it somewhat of a puzzle to find out which was granny and which the sofa cushion, it struck me that perhaps some notes on the subject might be useful to amateurs. One would think the ability of photographing cats at all would carry with it the capacity doing them dressed up, but as this is not the first time I have been questioned about it one must recognise it as a separate art.

To begin with, we must try and not disturb the becoming equanimity of puss, for we do not want her to look pitiable, and we must also see that we have a plain background, so that she does not get mixed up with a sofa cushion or any other unimportant accessory. The same as in ordinary cat photography, there is nothing that makes one's work easier than having a cat, or rather training a cat, to like being photographed. This may sound rather far fetched, but, as a matter of fact, some choice pieces of meat or fish will make puss very willing to pose purringly in front of her plain background. If she is petted and the plate of dainties kept near she will not be in the least hurry to get down, and seeing such a happy and contented cat needs only a tiny stretch of the imagination to convince one she thoroughly enjoys the actual photography.

There is one thing, however, that she distinctly does not enjoy, that is having her clothes put on. In this respect she is like a naughty baby, and wants no end of humouring and petting, and succulent morsels popped into her mouth. The hat is a special difficulty, for she seems to regard having to wear it as a terrible indignity. Consequently, some tempting rewards must be in readiness for her if she has sat still enough to keep it on, and grave, shocked scolding and no bit of meat if she has been inconsiderate enough to let it roll off. The punishment should never go beyond a scolding, as the chief thing is to keep her in a good temper, for, as with a human portrait, we are terribly at the mercy of expression.

For animal photographs one is naturally very dependent on a good light, for short exposures are all one can hope to get. There is probably now too much wind for out-of-door work, and even if it were still it would probably be too cold, for wind and cold are both very trying conditions to a cat's temper. It is however, quite possible, if we choose the brightest part of the day, to do quite satisfactory indoor cat studies. The accompanying illustrations [note: too poor to reproduce] were done at twelve o'clock on a November day from 3 to 4 feet from a window. The background - a plain piece of white cardboard, propped against an ease - was placed sideways and a little inclined to face the light. The room was unfortunately small, so that the camera was not really able to get far enough away from the subject. One should, if possible, allow more room, as having to get up so close means having to give a longer exposure, which increases so rapidly the nearer one gets to the subject.

November was daringly late in the year to attempt cat photographs at all. It was only the order for a set of dressed-up cat photographs for picture postcards before. Christmas that was answerable for the experiment. However, with the help of the best light of the day, nearness to window, and the clothes, it is not even difficult. The clothes are, in this case, more a help than a hindrance, for puss is much more inclined to sit still when dressed up. She would like to go for good, perhaps, and may be watching covertly for a good opportunity, but she feels too cramped with these strange, unaccustomed garments to fidget, and often sits absolutely motionless. A bulb is more to be recommended than a shutter, for one can thus get the chance sometimes of giving quite a full exposure. One never has any pleasure in an under-exposed cat photograph; one wants a certain amount of detail, but an under-exposed photograph of a dressed-up cat becomes almost comic in a way not intended, for clothes and cat look so hopelessly mixed up together. It is also well to remember that lighting plays a big part in the photograph itself, apart from exposure, and a dully lighted subject makes a dull photograph. Sun is, of course, not needed, but we must remember puss should have bright enough light on her to show the sparkle in her eyes, the shine on her little nose, and the silvery sheen of her coat.

The lighter the garments the better. The little cap in "Good night" is made of Japanese tissue paper, and the "nightie" the same, so that the rather touchy model hardly realised she was dressed up at all. A little coloured paper or bits of stuff and few pins soon made a costume, and if some rather large doll's clothes can be got one can do all sorts of things.

It is amusing what character sketches one can get with a dressed-up cat. If the clothes are a little extreme they will tell the tale and seem to give puss the expression required. For instance, a rakish hat makes a rakish-looking cat, and the face under the new toque seems asking for admiration. If possible, we must keep grave over the performance, for animals are very sensitive to ridicule, and puss hates being laughed at as much as she enjoys admiration, and it s our business to make her pleased with herself and her uncomfortable clothes.

Though some may be inclined to look down on this work as a waste of time and plates, yet it has its practical side, for just now dressed-up cat photographs are very popular as picture postcards, so that ones work, as well as affording interest and amusement, can also be made to pay.

PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARDS

One way in which early photographers subsidised their photography was to turn their photos into picture postcards. The newly invented Kodak process captured the images on celluloid (making life much easier for photographers such as Lucy Clarke). It was now possible to take snapshots as well as carefully staged images. Edwardian photographic studios not only produced picture postcards, they could profit from the new process by copying amateur snapshots into postcards, calling cards and business cards. These cards were not only functional, they were highly collectable.

Calling cards were highly popular in a day and age when people had "at home" mornings or afternoons where they received guests. Exchanging calling cars was an essential part of the social event. Picture postcards were also popular in a day and age when you couldn't simply phone a friend. Many cards were released in sets or series to appeal to collectors.

The new process meant that it had become astonishingly cheap to produce photographic cards. Around 1905, the early mail-order firm Barker's of Kensington, an early mail-order firm, would 144 photographic postcards from the same negative for 11 shillings (less than one old penny per card). According to the Barker's advertising, this rate "afforded a splendid advertising proposition for business men and for boarding house proprietors."

Professional cat breeders also used the photographic cards to publicise their stock. They no longer had to rely on wordy descriptions, they could afford to give away photos in the hope of recouping the cost when the photographic subject was sold. It was easy to give out cards to prospective purchasers. One such card was sent to a Mrs Challis of Clatterford Hall, Ongar, Essex (many fanciers were well off and had impressive addresses). The picture is "Black Knight", a winner of six championships and the message was "Are you still considering black kitten to breed from? I may part with my last one. It is a good one, but not very cheap, having lately gained a Reserve.".

Owners could send cards of their prize-winning, or simply pretty, cats to their friends. A picture postcard posted from Haywards Heath, West Sussex, in 1910, bore the photographic subject's proud owner's message "My 'White Coral' 1st Prize." Another was sent in 1906 from Birmingham to a friend in Malvern, Worcestershire. The card was a photo of her Persian cat, Miss Marcooli, and the sender offered to send further prints for the friend to sell on at a profit. "If you have six they will be 3/6 [three shillings and sixpence], and you can have twelve for 4/6. Can you do with that many? We can get them thro' by the 26th."

A GREAT PAINTER OF CATS (The Sydney Morning Herald, Jan 2nd, 1891)

"Vivent les chats!" wrote Mme. de Custine in one of her delightful letters to Buffon, wherein, with no little scorn, she stigmatises the dog as a mere "fidelity machine." "Civilisation has not yet become a second nature for them. They are more primitive than the dog, and more graceful; more independent, freer, and more natural. When by chance they love their tyrant, man, it is not as a degraded slave, like your craven dogs, which lick the hand that smites them for the reason that they have not the spirit to be inconstant! In cats attachment is the result of selection, but in dogs of stupidity. Your canine idiots are the product of society, and are appreciated by man just as double flowers, which are the result of cultivation, are appreciated - because they are to a certain extent his own work. I fear my sentiment may annoy you; if they do, hate me, but tell me so often. None, I take it, but a Frenchwoman of originality and esprit, of the temper and fibre of Mme. de Sevigne, would venture to give frank utterance to such sentiments as these.

To love a cat, it has been truly said one be in complete harmony with its nature and in a manner partake of it; and to admire it just for its lack of affection is assuredly a palpable, a most palpable, confession. The Portuguese have a saying: Buen amigo es el gato, sino que rascuna (" The cat is certainly friendly, but it scratches "): and it may, I think, be taken that the fair writer was more completely in sympathy with the animal of her predilection than she herself suspected. In the face of this eighteenth-century instance, are we not reminded that in his "Satire on Women" - the earliest satire extant, by the way - Simonides set it down that forward women were made from cats, just as the most virtuous and the best were developed from bees?

To most people the cat has recommended, if not exactly endeared, herself by the implacable guerrilla warfare she - why always "she"? - prosecutes against the common or garden rodent; that is her claim upon the suffrages of society. But to consider her from the artistic point of view, and to be content to see in her not only a sitter of certain possibilities, but the reflection of much that is most delightful and most admirable in nature, requires a temperament of a rare kind, and makes an enormous demand upon the aesthetic gifts of the painter.

Truth to tell, there are few things animate or inanimate so difficult to paint in the whole range of art as a cat or a kitten; and the reason is not far to seek. The proverbial chameleon is more stable in point of colour than the cat in respect to its contour, its expression, and its markings which vary with every movement, with every thought, of the fickle- minded beast. But as it is the worst of models for the easy-going artist, so is it the most fascinating ; the one, probably, that has defied more deft and famous pencils than all the other domestic fauna of Europe put together. To the horse, the cow, the stag, the sheep, the dog, eminent artists have devoted their attention and their talents times out of number ; but how many have ventured on Shylock's "harmless necessary cat," and succeeded in portraying her form and feature true in life and spirit ? Mme. Rosa Bonheur shrinks from the contest. Nay, she has painted the face of man oftener than the cat's, as you may count on the fingers of your one hand ; while the principal animal-painters of all times have elected to avoid a particular branch of art which exacts such exceptional keenness and sensitiveness of observation, such swiftness and decision of touch, and such an inexhaustible stock of patience.

From the days of Nicias, who was the first to paint a dog, three centuries and more before the Christian era, down to those of Mr. Briton Riviere, it has ever been the same [note: the writer overlooks the cats in Egyptian art]. Troyon and Mr. Peter Graham, Herring and Mme. Rosa Bonheur, George Morland and M. Van Marks, James Ward and Mr. Sidney Cooper, Fyt Snyders, Potter, masters ancient and modern - all who come uppermost to the mind - have almost without exception kept to their cattle and pigs, their horses, boars, dogs, and sheep. Breughel and Teniers, it is true, painted their famous grotesque "Cat Concerts," the former more successfully than the latter; but neither very happily from the point of view of either accuracy of form or insight into character - nay, they are not to be compared with the admirable print of the ill-fated Cornelius Visscher. Landseer is perhaps the only English animal-painter of eminence who has not left Grimalkin eeverely alone, but the couple of cat-pictures he painted - "The Cat Disturbed," in 1819, and "The Cat's Paw," in 1824 - were not satisfactory In his eyes, so that he henceforward eschewed all dealings with the Beloved of Pasht. This is indeed the more extraordinary when we reflect that she has been held sacred in the eyes of many people, and has always occupied a position of honourable trust and admitted importance on the hearth of civilized man.

It may be that the superstitions that have ever dogged the unfortunate tribe of the cat, and made of her for centuries a persistently persecuted beast, tended to decrease her popularity with the painters and their patrons of a more credulous age. The symbol of liberty in Rome-blazoned courant or passant on the shields of doughty warriors - by reason of her independence and dogged refusal to be taught, or to conform to rules; and the personification of the moon in Egypt, by the contraction of her pupils by day and their dilatation by night, she became an object of suspicion, dread, and hatred to later generations. How had the mighty fallen ! A deity in the land of the Pharaohs from the time she was imported from Persia, she was worshipped while she lived in Egyptian clover, and when she died her mummy was reverently placed in the Temple of Bast or Bubastis, as Diana was elsewhere less euphoniously termed.

Thence she travelled, via Cyprus, to our shores of Cornwall, but it must be confessed with no slight loss of dignity by the way. True, she arrived with the reputation of a doughty huntress of vermin and a deft chaser of snakes ; true, too, that the fabulists had painted morals out of her, and the most imaginative of the romancists had set her a worthy place in the immortal pages of the "Arabian Nights." But her honour had been tarnished ; she was no longer the Aelurus of earlier days. Satan had chosen her form for his favourite Protean change. Hecate, too, as a matter of precaution, unhappily struck on the same idea, as Ovid tells us, Fele soror, Phoebe latuit ; so that she fell into disrepute.

She lost character and caste slowly and surely, and step by step, till at length, the last resource of the metamorphic Djinns, she was reckoned the familiar of the witch and the companion of the unholy. It availed her nothing that by the Laws of Howel -the great legislator of the Kymry - her price was maintained at a respectable figure, and the torment of her body was enacted a felony. The sailors had found in her a Mother Carey's chicken of disreputable and evil import, which by the mere playing with on apron or toying with a gown could so foment a storm that would rend sail and snap mast, that she must of a surety be in league with Davy Jones himeelf !

Personal feeling had probably not a little to do with this unfortunate degree of unpopularity, for in many people a deep- seated dislike of the feline race, root and branch, is a matter of temperament and constitution. We have all heard how Henri III would swoon at the sight of a cat, and how Napoleon was little less affected ; to such a degree, indeed, was it the case with the petit caporal that Mme. Junot is said to have gained an important advantage over him by the exercise of a little diplomatic tact in merely mentioning a cat at a critical moment in a certain discussion. But this aversion can hardly be urged in these later days as a reason for the banishment of the cat from the studio except for utilitarian purposes.

The truth of the matter is, that for painting cat- life and character, peculiar qualities are necessary in the artist to bring him into line with the oddities of his model's temperament. As the late M. Champfleury - the cat's Macaulay -has said of it and its habits "The lines are so delicate, the eyes are distinguished by such remarkable qualities, the movements are due to such sadden impulses, that to succeed in the portrayal of such a subject as this, one must be feline oneself." That, doubtless, is the secret ; and unless you are as "feline" as Rouviere, the actor, you cannot hope to raise the felis domesticus into the realm of art by brush, by pencil, or by chisel. Nor is this all. You must love them as Mahommed and Chesterfield loved them; be as fond of their company as Wolsey and Richtlieu, who retained them even during the most inpressive audiences; as Petrarch and Dr. Johnson and Canon Liddon, who wrote with them at their elbow ; and Tasso and Gray, who celebrated them in verse; think of their worldly weal like the Sultan El Dahar Beybars, who fed all feline comers, or "La Belle Stewart," Duchess of Richmond, who, in the words of the poet, "endowed a college" for her little friend; you must be as approbative of their independence of character, their unamenableness to education, their inconstancy, not to say indifference and their general lack of principle, as the aforesaid Mme. de Custine; and as appreciative of their daintiness and grace as Alfred de Musset. Then, and not till then, can you consider yourself equipped for studying the art of cat-painting. As Mr. Ruskin has it, you must know "kitten-nature down to the most appalling depths thereof," and be sensitive to the "finest gradations of kittenly meditation and motion.

The representation of cats in art is, of course, not rare; but good representation is. Since the archaic bronzes and statues of Egypt, and the mural paintings of Thebes, cats have now and again been seen in prints and upon canvas. The visitor to the recent Tudor Exhibition will remember the pictures, so touching from the association, of the cat which is said to have fed Sir Henry Wyat with pigeons while he was imprisoned in the tower. Was Joanna Baillie, thinking of this incident when, in her ode to "The Kitten," she wrote these ending lines?

Even he, whose mind of gloomy bent,

In lonely tower or prison pent

Reviews the coil of former days,

And loathes the world and all its ways,

Feels, as thou gambol'st round his seat,

His heart with pride less fiercely beat,

And smiles, a link in thee to find,

That joins him still to living kind.

Yet, as I have said, many artists have tried, and most have failed. G ricault, Barge and Delacroix all made the experiment, and they far oftener succeeded in producing diminutive tigers than cats; thus reminding of the saying of Mery, Louis XIV's surgeon: "God created the cat that man might caress a tiger." Although great artists have tried, and been only partially successful in this line, specialists of note have arrived at perfection, or very near it, by the exercise of those qualities to which reference has here been made. Combining with technical skill and ability the power of piercing the strange unscrutableness of the cat is her calmer moods, of differentiating individual characteristics, and classing with well-nigh scientific accuracy the thousand and one humours, and motions, and expressions of cat-mind and body, as wall in irresponsible and thoughtless youth as in sober age - in short, the capacity to appreciate "felineness" in all its many aspects - a handful of artists have arisen to eminence and secured for themselves a niche in the Temple of Diana. But whole-hearted devotion to the subject is the price which has been paid for the distinction. Who that has seen it will readily forget the cat carved in wood over the gate leading from the Mausoleum at Nikko - the Nemuri no neko, or "Sleeping Cat (or Rat-klller)" ? That by itself will sustain the reputation of the artist Hidari Jia-go-ro. Japanese artists in black and white have done much in this direction, especially Hokusai ; and Caldecott, basing his method upon theirs, produced some sketches of cats quite marvellous in their truth to nature.

But these are comparatively insignificant beside the brilliant work done by Gottfried Mind, the Swiss, celebrated as the "Cat Raphael" on the initiative of Mme. Vigee Lebrun, of the end of the last century and the beginning of this ; whose gentle nature never recovered the horror of a massacre of cats ordered at Basle, where he lived, in consequence of an outbreak of madness among them in 1807. His works are very Japanese in their style of execution, but the facility with which character and expression alike have been seized, and the correctness of the drawing, are far beyond anything produced in this direction in the Land of the Rising Sun.

But better than all these, for general truth to nature, are the wonders of Desportes, of Menginot, the pencil drawings of Grandville and even of the unknown Burbank, and, more important still, the pictures of Eugine Lambert and of Mme. Ronner. For them cats' life has no mysteries ; and the kitten, which, for the majority of us, is merely "an animal that is generally hurrying somewhere else, and stopping before it got there," is to them as comprehensible and logical a little creature as any that walked out of the ark.

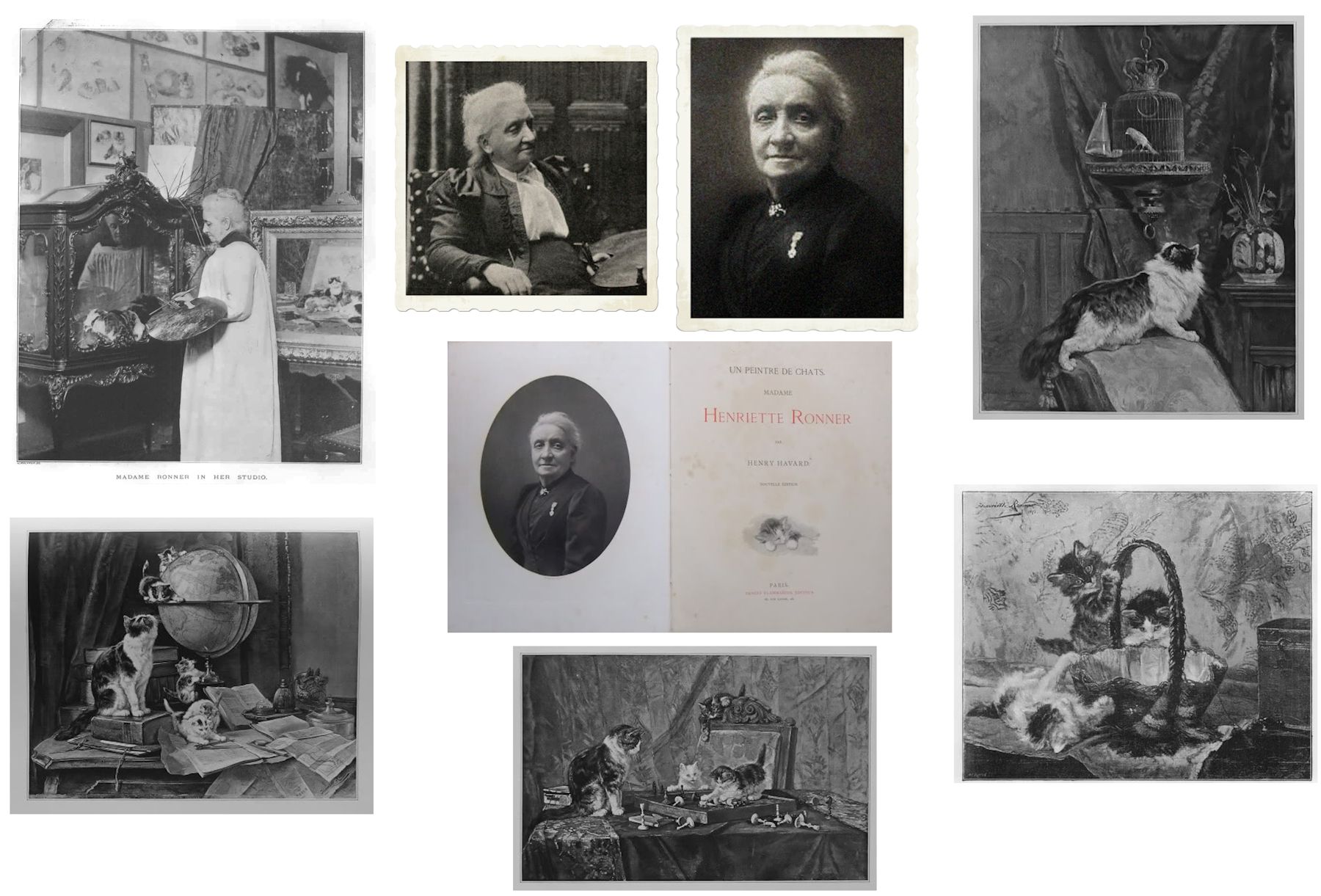

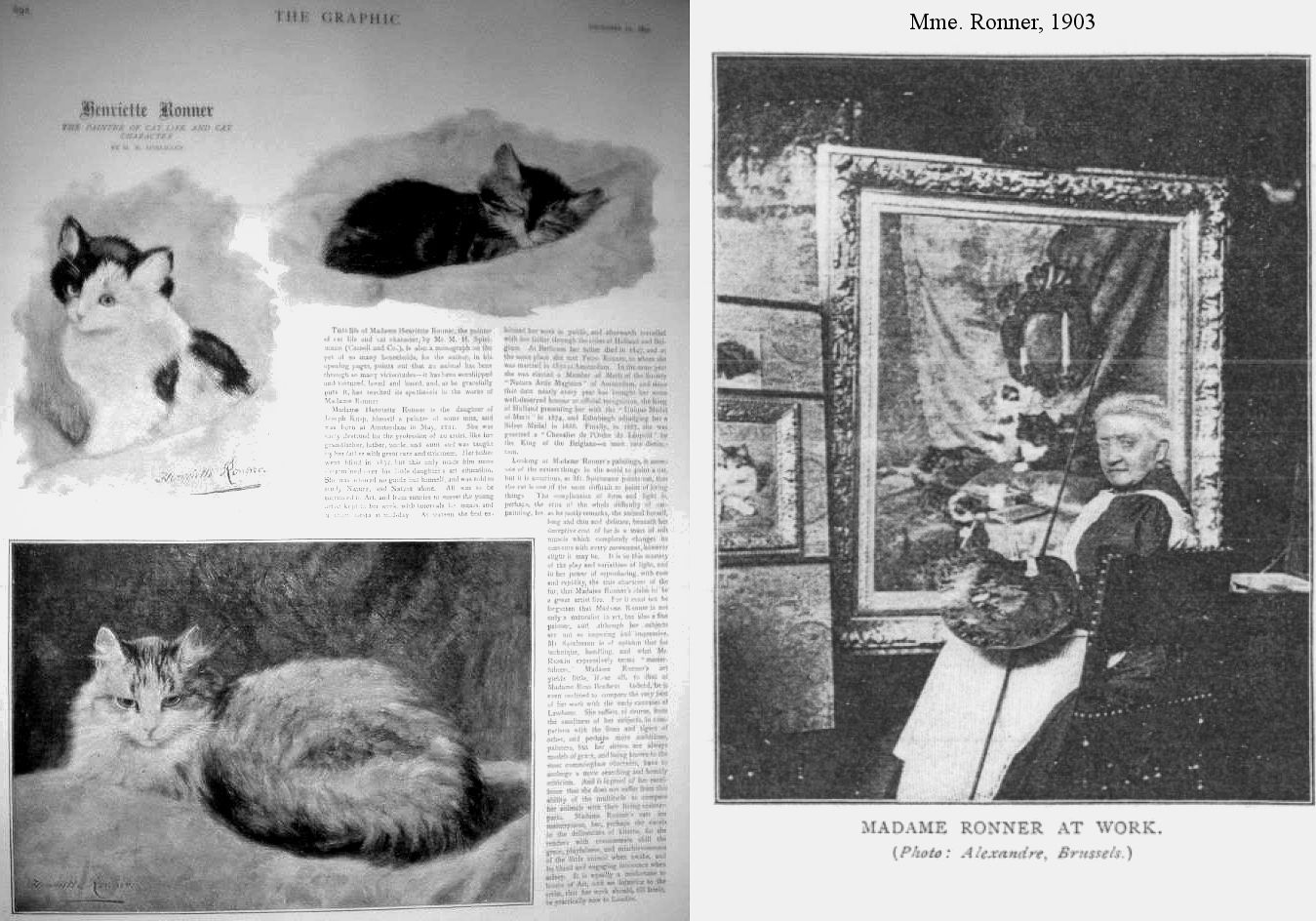

Mme. Henriette Ronner was born in Amsterdam in 1821, and displaying much taste and talent for drawing, while still of tender years, she was destined for the artistic profession by her father Heer Knip, who superintended her education himself, and enforced his principals with quite unusual severity. Undeterred by the misfortune of his blindness, which overtook him when his child was but 11 years of age, he steadily continued in his purpose, and, keeping her at the easel from sunrise to sunset, chiefly in the open air, he insisted on a couple of the midday hours being passed in total darkness, that she, too, might suffer the most terrible of all afflictions for an artist. The day's work was cheerfully undertaken by the girl. Gifted with qualities that would have made her eminent in the broader path of promiscuous subject-painting, she devoted her attention to cat, dog, and still-life, till at last she had achieved the position of acknowledged rival of M. Lambert. But the way was long and hard.

In turn she gained awards at all the principal exhibitions to which she contributed, in Holland, Belgium, France, Portugal, and America, until her claim was universally admitted. This position she still retains, and many a continental corporation museum has deemed it well - nay, due to itself - to possess itself of works by so skilled and eminent a band. Since her marriage 40 years ago Mme Ronner has lived and practised in Brussels, selling her works there, as well as in Paris and in Scotland, as fast as she can paint them ; and painting in such a way as to win many medals and kindred honour , while building up the fabric of fortune and solid reputation.

But Mme. Ronner is not only a naturalist in art ; she is really a fine painter. Although somewhat limited according to English notions of what constitutes a colourist, her technique is at least as fine as Rosa Bonbeur's - virile, vigorous, decisive, unfailing in its truth, and admirable in result. As might have been seen at the excellent exhibition of her pictures of dogs, cats, and poultry, which was recently held at the galleries of the Fine Art Society in Bond-street, Mme. Ronner is as accomplished an artist as she is a keen observer, and as successful in the rendering of the most transient of feline emotion and expression as she is dexterous in the suggestion of texture, however difficult, of form and movement, however complicated. Her little model lives, and, like Princess Ida's, "Her gay-furr'd cat's a painted fantasy."

She paints it in every phase and humour of all its nine lives, and, as George Withers would say, with care enough to kill it. But her cats are all well-to-do, plump, silky, and lovingly cared-for; the lean and the mangy do not appeal to her as they presumably would have done to Courbet. "The Longing Look" - a cat watching a canary - like her prototype in "Pericles," "with eyes of burning coal" - is a revelation of cat- character ; the raised head, the drooping tail, the half- unsheathed claws, the quivering body, are so absolutely life-like that it seems a wonder the bird does not struggle to fly right out of the picture.

Then, how true is maternal care in the etching which Mr. Mendoza published a year or two ago, and how comically pathetic the love-sick "Djouma," with tall as "monstrous" as Carey's in "The Dragon of Wantley!" And what could be more lazily inert than that heavy old black tom-cat lying luxuriously by the hearth? - reminding one, as it does, of Mra. Pipchin's old cat, little Paul Dombey's friend, which, coiling itaelf upon the fender, used to purr egotistically, "while the contracting pupils of his eyes looked like two notes of admiration."

Had Mme. Ronner lived when the poet Gray suffered his celebrated bereavement by the tragic loss of Selima - who perished miserably in a gold-fish bowl - surely she might have helped to console him and comfort him for his loss. Pretty and graceful, yet terribly in earnest, for those who are in sympathy with it, the kitten constitutes the most charming of models for artist and poet alike. And perhaps it is, after all, in the delineation of it that we shall find Mms. Ronner to excel if we carefully analyse her work, the incomparable grace and playfulness of the little animal when awake, its engaging innocence when asleep, and the unconscious conviction betrayed in its every movement that the whole world was made for its amusement alone, are all consummately rendered.

Many are the subjects such as these that Mme. Ronner has painted for us with unrivalled charm and unerring excellence of execution, and a few are here reproduced. Although a septuagenarian, she betrays in her canvases none of the failings of age; and that, after all this lapse of time, her work should this year be new to our metropolis is equally a misfortune to art-lovers and an injustice to the artist. Not that we have no cat-painters in England ; in Mr Couldery, Mr. Walter Hunt, and Mr. Louis Wain we have men who understand and appreciate feline beauty and feline character, although they are not of the calibre of Mme. Ronner. But the quality of her work has greatly been lost sight of in the subject. Yet, surely, the dignified and graceful beast whose praises have been sung by Petrarch and Tasso, by Gray and De Musset, by Chateaubriand and Baudelaire, by Moncrif, Paul de Kock, and Dumas fils, is worthy of the artist's brush and of the exercise of his most precious talent.

CATS POSED FOR HER. HOW ONE WOMAN WON FAME PAINTING HOUSEHOLD PETS. (Chicago Daily Tribune, 12th March, 1892)