CAT FUNERALS IN THE NINETEENTH AND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES

We tend to think of pet funerals, cremations, pet cemeteries and animal caskets as a modern trend. We bury our cats in the garden if we have one, and if local bye-laws permit, or we can opt for a pet cemetery or for cremation. Caskets - ranging from simple to ornate to “eco-friendly” - are available for the body or ashes and there are almost as many options for "animal family members" as for humans. Some owners have the ashes of a departed pet placed in their own coffin, or have their ashes scattered together. Nineteenth 19th century pet owners were often equally sentimental and, if their means allowed, buried and memorialised their cats.

Proper disposal of pets' bodies - like human bodies - was a case of hygiene as well as sentiment. If you lived in a tenements or a back-to-backs, there weren’t many options for disposing of deceased pets except to leave them on the ash heap to be collected by dustmen, or to secretly inter them at the edge of a park or field. The less-loved dead dogs, and dead cats, were often dumped outside the town walls in the “Houndsditch” where “dead dogges were there laid or cast”. Later on, Batterseas Dogs' (and Cats') home would cremate your pet for a small fee. If you had a garden or vegetable plot, pets could be buried there, preferably under a bush or tree where the grave wasn't likely to be disturbed. Where possible, beloved 19th Century pets were buried at the end of the family garden. Funerals were informal, household affairs and puss's body was wrapped in cloth or placed in a box for burial.

Any visitor to 19th century pet cemeteries in Britain will notice that most grave-markers are for dog, often commemorating the deceased as a “loyal companion” or “loyal friend.” Until the public's opinion began to change, thanks to cat shows, cats were considered second class pets or utilitarian animals kept only to control rodents, or as the pets of spinsters. Monarchs and Presidents alike are associated with dogs, rather than cats. In Britain, Queen Victoria loved pets and in 1840, she gave her official patronage to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Her pets included two blue Persian cats and her daughter, Princess Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, became a patron of The National Cat Club. This helped change the image of cats as pets as people copied the royal family.

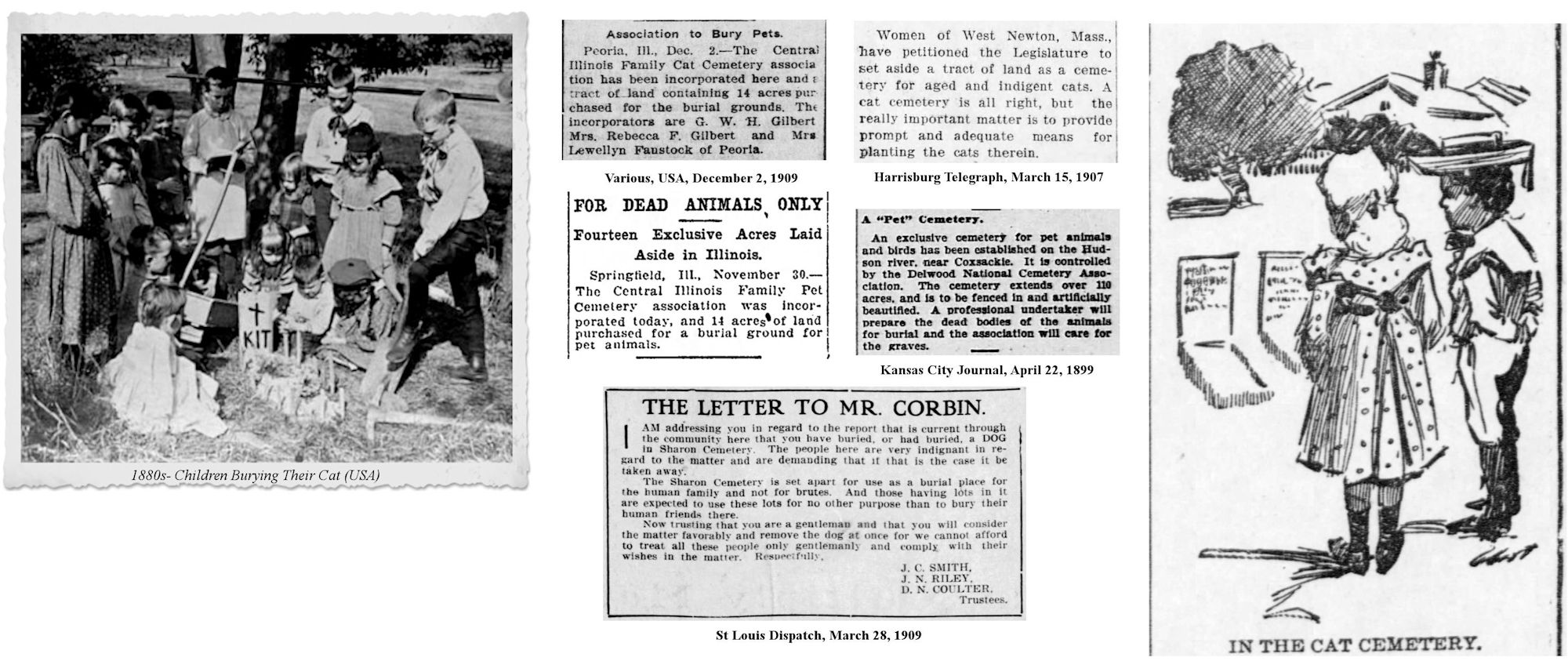

“FOR THE CHILDREN”

Many “pet funerals" were held so that children had closure; many were arranged by the children to whom the cat had been a playmate and companion. They often copied the all-too-common human funerals they had witnessed, using a wheelbarrow or toy wagon as a hearse and holding a Christian-style service at the graveside.

This excerpt from a "Juno - Not She of Olympus, But One of Much Lower Degree," a short story by "Dallas" printed in The Times (Philadelphia, USA), May 19, 1895 gives an idea of a small family funeral conducted by children: "Juno was about a year older. I think, when there was a death in her family. The one little kitten that she loved with all her mother heart, died and left her desolate. It was a very sad occasion, I remember, but we had a great funeral. We dug the grave at the end of the garden. Johnny's express wagon was the hearse, and Johnny drew it and was very serious indeed. We borrowed Mrs. Martin's baby carriage and that was the mourning coach. Juno rode in it with Ned and Gimps walking one on each side and holding her in. I pushed the coach while a long procession of the neighbors’ children came behind, crying with all their might. We sung a hymn at the grave and did everything we could to soothe Juno's grief."

The Evening Express, 27 July, 1898 also gives an account of a funeral held by children for a cat:

’CATS IN CABS. MOURNERS AT A FUNERAL. Little Dottie Gatehouse's cat is dead - dead and buried. "Flossie" was the poor tabby's name, and she was a Maltese of high degree. Her fur was soft and almost blue, her eyes large and sympathetic, and as for her claws - why, she might as well have had none, for all Dottie and her playmates knew. Dottie is seven now, and she knows a whole lot of things, Sunday School songs, fairy tales, and a heap about the brave soldiers who are fighting the proud and deluded Spanish. Dottie, with her soft-eyed Flossie, lived at 2,335, Seventh-avenue, the Bedford Flats, and Dottie lives there yet, but no one knows where Flossie is now. Her body is under the ground at Watt's Hill, on the Seventh-avenue drive, between One Hundred and Thirty-eighth and One Hundred and Thirty-ninth streets, with a pile of buttercups and daisies over the tiny mound. The funeral was a sad and solemn thing for all the children in the Bedford Flats, who are in Dottie's set. All the girls had loved Flossie, and every one of them used to sigh when her little mistress took her away to put her to sleep in her little bed in a rosy-lined box, next to Dottie's own crib, with the shining brass rails and knobs. So when Flossie died her bereaved owner went first to one and then to the other of her dearest friends, until seven pretty little girls and two nicely-behaved boys said they would go to the funeral and help bury the poor kittie. Everyone brought a bouquet of buttercups or a bunch of daisies at three o'clock in the afternoon, when school was over, and placed them on the bier, made of a gingersnap box, in the bottom of which rested the mortal remains of Flossie. The body was dressed in a brand new white gown and tucker that Dottie had made for her newest doll, and with tears Dottie told all the mourners how sad it was to have to disappoint the doll.

"Oh, but she won't know, Dottie," said little Ethel White, "and, then, there's nothing too good for Flossie."

All the girls brought their doll carriages, and the two boys had their tricycles.

"We ought to have some other real live cats to go in the carriages," whispered Madge Madden, who lives around the corner, to Ethel.

"Yes, indeed," said Ethel, and then they all went out and borrowed the cats from the top floor to the basement of the numerous Bed- ford flats. They were well-fed cats and of kind dispositions, and when the cortege left the stoop of 2335 there were seven solemn-looking tabbies with black ribbons about their necks strapped in the seven doll carriages. Dottie's carriage was the hearse, and it was draped all in white like Flossie's body, which was lying in it. The two boys on their tricycles carried the flowers and were the last in the sad procession that slowly moved up to Watts's Hill. There a grave was found, already dug by the Savage twins, a couple of three-year-olds in kilts, who make Watts's Hill their Klondyke. Reverently the body of the lost playmate was lowered into the grave, and each little boy and girl threw clods of dirt upon the ginger-snap coffin. - American Paper.’

This little piece from the Daily News Democrat, October 8, 1904, tells us just how important it was for the children to have a focal point for remembering their lost pet: “Two little misses on Webster street are great lovers of kittens and each was the possessor of a fine specimen until a few days ago. For some unknown reason both took sick and died within a few hours of each other. The back lot was converted into a cat cemetery and two graves were dug-one for Bedelia and one for Dot. The only consolation Corinne and Mabel now have is to spend a short time each evening at the flower-covered graves and burn colored candles as they discuss the frailty of life and the advisability of caring for a couple of other stray cats.”

Sometimes the simplicity of children should teach adults a lesson. In 1902, three youngsters of Norwich, Conn., set up a little burying ground called “Cat Dale Cemetery” for neighbourhood cats. The conducted cat funerals, something that became quite an attraction in the town. The cat was placed in a lined wooden box and buried, after which the children wrote epitaphs for the deceased, for example “Tom Goodwin. Died 8th of August, 1902. Tom died about the middle of the morning, August 8th. Emily Goodwin’s cat. It was a good cat in its life. It was treated good and had a good home and had plenty to eat. This little girl felt very sorry to have her little pet die. It was the only one she had. But she was good to every dumb creature. She took care of it very well. Tom is dead now and happy.” While astray cat had this epitaph: “Died on August 6, 1902. Good and noble in his life. A stray cat Dide on Whittaker’s lorn on August 6, 19 and two. Some naughty boys threw it into a barel and threw some sand in its eyes. Suffered by some disease. Fed it and it would not eat. We named it Freddie. But now it is dead. Dide at 3:30 this afternoon. It is out of its muserary. Poor little thing, It is dead now.”

NOT ONLY FOR THE CHILDREN …

By the mid 1800s, owners with sufficient means held quite formal cat funerals. Those with country estates or large town gardens, had their own private pet cemetery, complete with gravestones. Some of these can still be seen at listed (preserved) buildings, while others are lost in the undergrowth where the garden met surrounding fields or woods. In cities, subscription pet cemeteries were set up, though the clientele were primarily the doggy set. Those wealthy enough, had long memorialized their favourite pets in portraits. A few chose taxidermy, which sounds gruesome, but let them keep their pet close, even after death.

The Cimarron News (Kenton, Oklahoma), of May 5, 1899 gives us a description of a cat funeral, including the owner’s reason for holding it: “A Cat Funeral. In Elkton, Md., they held a queer funeral last week. A cat belonging to a wealthy man died, and he had made a beautiful black coffin, covered with cloth, studded with gold-headed nails and finished with four silver handles. Then he dressed poor kitty in a black shroud and put her in the coffin, where she ay for two days for all her friends to see and meow over. Then he had four boys act as pallbearers, and they had a regular cat funeral, and planted flowers over pussy’s grave. When the cat was young, which was 13 years ago, it was a great friend of its master’s little daughter, who died, and that is why he thought so much of pussy and gave it such an expensive funeral.”

In England, high society were allowed their eccentricities, including publicly admitting their grief for an animal. The New York Times, August 6, 1899 reported "Just at present Lady Marcus Beresford is, according to English prints, plunged in great grief over the loss of two Siamese cats named Tachin and Cambodia. This would seem odd to Americans at first glance, but Lady Marcus is the President of the Cat Show in England, and has made thousands of pounds with her remarkable cattery, which is famous all over the world, and which possibly appeals to the British mind as a fad and as equal a social distinction as that of driving an automobile into a stone walk or up the steps of a piazza."

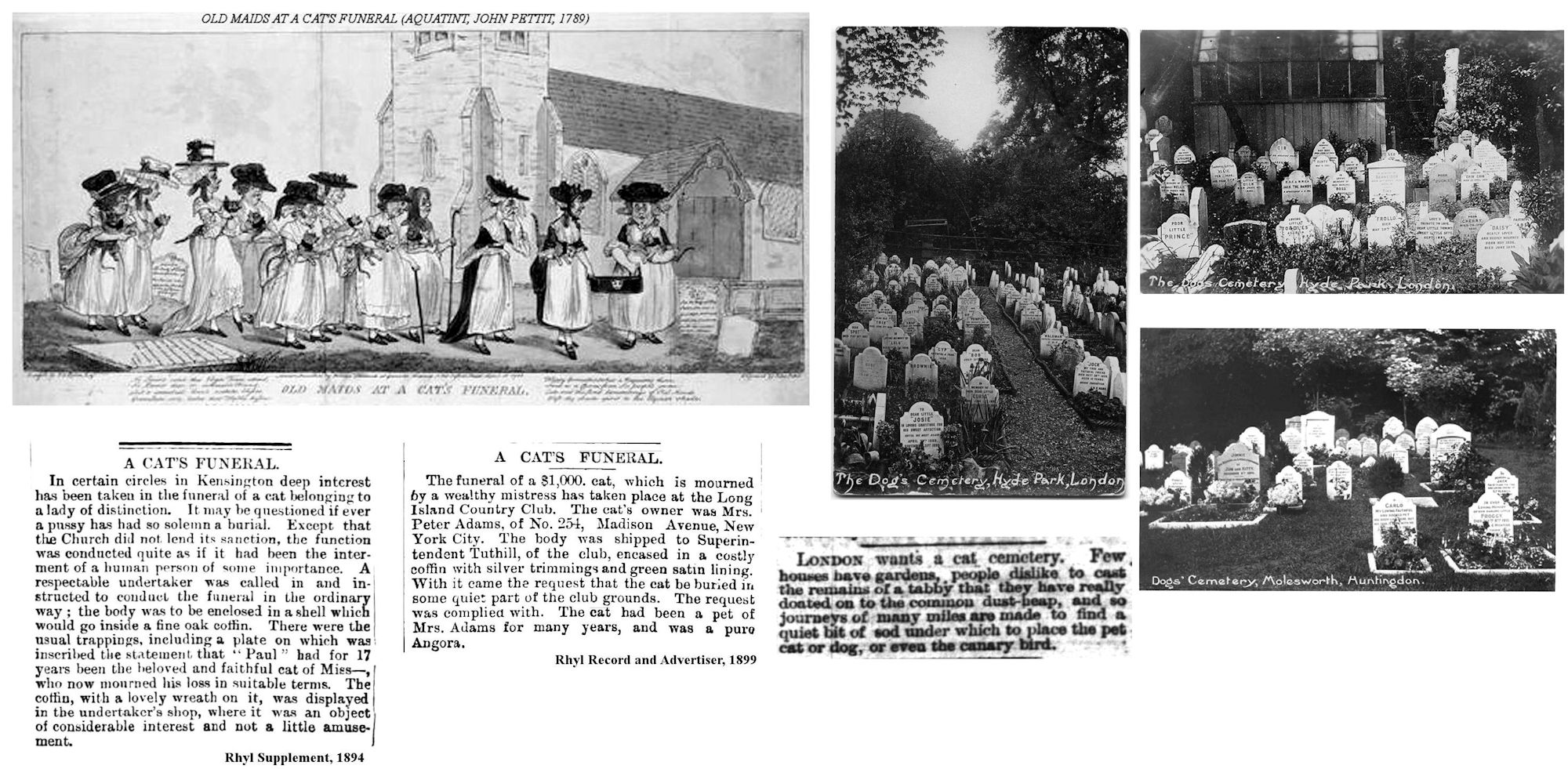

In the early days of the cat fancy, newspapers reported that cats were once again being revered, just as they had been in ancient Egypt. This extended to death rituals and while mummification was no longer the main choice, cats could be given a dignified send off. Seeing a new opportunity, professions involved in human funerals provided the necessary trappings for a pet's funeral. Printers supplied black-edged funeral cards. Undertakers built simple or elaborate cat caskets. Stone masons carved and chiselled cat names and epitaphs on headstones. Clergymen (for a donation to church funds) performed cat burial services, albeit not on consecrated church graveyards. The rest of society viewed these ceremonies as eccentricities of the wealthy or aberrations of elderly spinsters. Some, on both sides of the Atlantic, were deeply offended that a mere dumb beast should be given a Christian burial. Others were fine with the idea that Christian treatment of animals (no cruelty etc) extended to a Christian send-off, after all, wasn’t God the God of all creation? In psychological terms, a funeral provided solace and closure for the owners.

The English Victorians elevated mourning rituals to a fine art, with rules about the duration of, and clothing for, "full mourning" and "half mourning." Their elaborate monumental masonry can be seen in many graveyards ... as can paupers' sections and everything inbetween. One might think they were obsessed with death rituals and to be fair, there were an awful lot of ways to die back then. The stereotype of the bereaved pet owner being an elderly spinster was prevalent in the press even then. According to The Portsmouth Evening News of August 17, 1880, a bereaved dog owner sent out black-edged funeral cards (part of the Victorian funeral ritual and almost as collectible as calling cards) and reported “It is superfluous to affirm that the owner of that lamented Fido is a maiden lady.”

In Vol XI of The Strand Magazine (January - June 1896), William G. Fitzgerald's article “Dandy Dogs’’ showed that mourning deceased pets had become acceptable. Funeral services, cemeteries, headstones, sculpted memorials, coffins and cremation urns were available, as were funeral cards. Pet cemeteries also became tourist attractions.

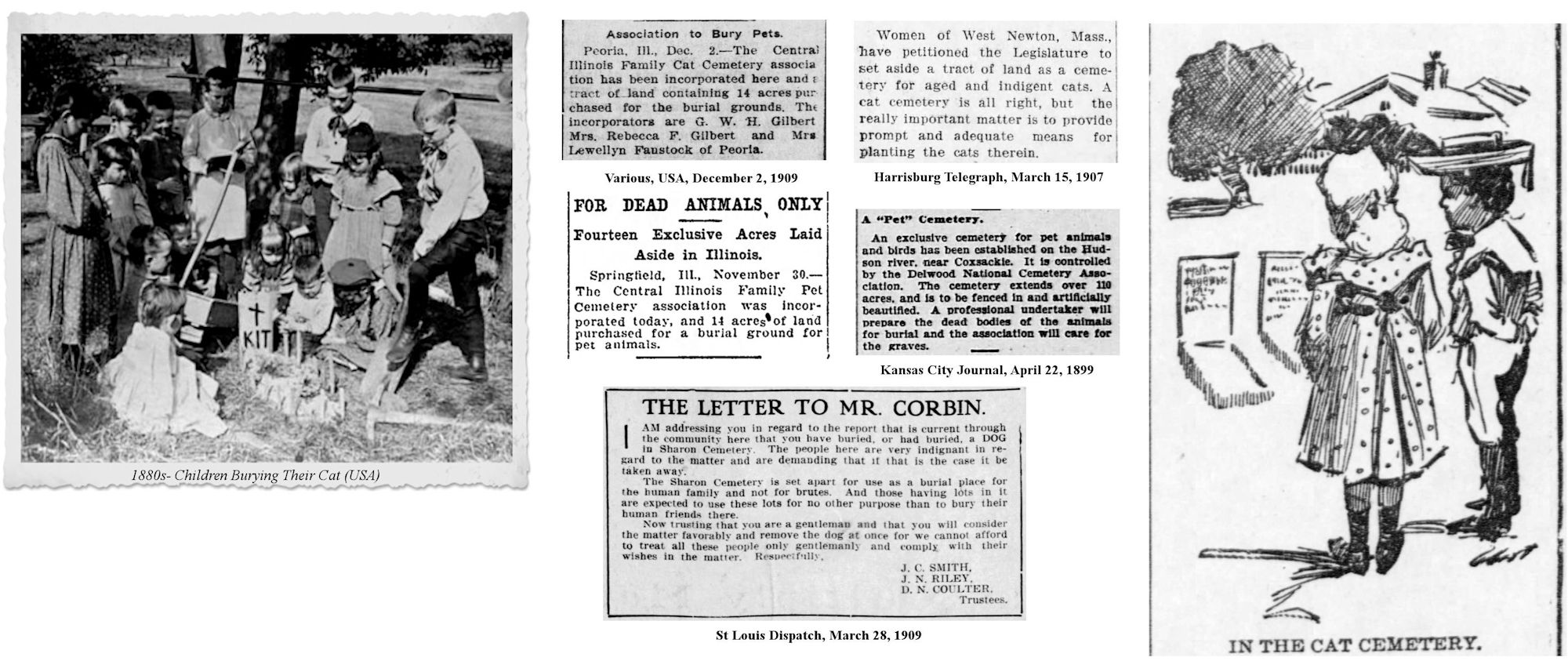

The Supplement to the Rhyl Advertiser, March 10, 1894 reported the story of a Kensington lady “of distinction” who held a funeral for her cat, Paul: "A CAT'S FUNERAL. In certain circles in Kensington deep interest has been taken in the funeral of a cat belonging to a lady of distinction. It may be questioned if ever a pussy has had so solemn a burial. Except that the Church did not lend its sanction, the function was conducted quite as if it had been the interment of a human person of some importance. A respectable undertaker was called in, and instructed to conduct the funeral in the ordinary way; the body was to be enclosed in a shell which would go inside a fine oak coffin. There were the usual trappings, including a plate on which was inscribed the statement that ‘Paul’ had for seventeen years been the beloved and faithful cat of Miss —, who now mourned his loss in suitable terms. The coffin, with a lovely wreath on it, was displayed in the undertaker’s shop, where it was an object of intense interest and not a little amusement."

Similar funerals took place in America. According to the Rhyl Record and Advertiser of February 25, 1899: " The funeral of a $1,000 cat, which is mourned by a wealthy mistress has taken place at the Long Island Country Club. The cat's owner was Mrs. Peter Adams, of No. 254, Madison Avenue, New York City. The body was shipped to Superintendent Tuthill, of the club, encased in a costly coffin with silver trimmings and green satin lining. With it came the request that the cat be buried in some quiet part of the club grounds. The request was complied with. The cat had been a pet of Mrs. Adams for many years, and was a pure Angora."

Some cat funerals adopted a more religious tone. For example, there's an account of a clergyman who held a funeral for his large black and white female cat who had been known to go for walks with him. When she died, the whole household were “thrown into mourning.”

According to “A Cat’s Funeral” in The Hull Daily Mail of April 1, 1897, “The inhabitants of a Border town are greatly exercised about a funeral that has recently taken place. It seems that one of the clergymen of the town had a large black-and-white cat, of which he was exceedingly fond. Pussy reciprocated the affection, and though troubled to an incompatible extent with obesity, would go out for a walk with her master when the weather was suitable. Lately the process of fatty degeneration went too far, and the favourite died, with the result that the household was' thrown into mourning. For three days pussy, whose remains were placed with loving care in a beautiful brass-bound oaken coffin, with inner linings of silk and wool, lay in state in the drawing-room. At the termination of this period the rev. gentleman hired a cab, drove to the station and took train for the North, bearing with him the oak coffin and the precious remains. Where the funeral took place seems to be somewhat of a mystery - at least there are conflicting accounts - but of one thing the people seem to be certain. The ceremonial respect which had been accorded to the deceased was maintained to the last, and the burial service, or part thereof, was recited at pussy's grave.”

This tale, related in The Lancashire Evening Post, August 1st, 1906, describes how two friends fell out over the death and funeral of a cat. It also shows the depts. Of attachment the owner felt for her cat. It ended with a court case as their antipathy grew, so here’s the relevant part regarding the cat: “Cat's Funeral. Baroness’s Remarkable Claim For Damages. Well-Known Pianist Involved. Mr. Justice Ridley and a special jury, to-day, heard the case brought by the Baroness von Perglass against Miss Tanner, organiser of the Animal Lover’s Society bazaar, for damages for false imprisonment and malicious prosecution. The Plaintiff, an Austrian lady had come to England in 1890 and formed a close friendship with Miss Janotha, a distinguished pianist. “But for the serious nature of this case, [it] might be described as humorous. Miss Janotha, who was apparently of a nervous and excitable temperament, was possessed of a cat to which she was devotedly attached. The cat got very ill and Miss Janotha got into a state of mind and body which was really pitiful. She would not eat of sleep and occupied most of her time in praying for the cat. Although it was being looked after in the most assiduous way by a veterinary surgeon, the poor cat died, and Miss Janotha was seized with a serious illness as a result of it, and the only thing that would comfort her was that the poor cat’s body should be taken to the Isle of Wight to be buried. It was taken down by the plaintiff as an act of friendship. “ The plaintiff tried to console Miss Janotha, but Miss Janotha became convinced that her cat had been poisoned in a conspiracy between the Baroness and the veterinary surgeon, at which point Miss Janotha became malicious towards her former friend.”

Not all cats were willing participants at their own funerals. According to the Dundee Evening Telegraph, 23 September 1912 “CAT AT A FUNERAL. Berlin, Monday. A pet cat was carried in the funeral procession of Frau Lonenz at Neukoln, the animal being subsequently interred in the same grave with the dead woman. This was done in accordance with the last wishes of Frau Lonenz, who in her will referred to the cat as the truest friend she had during the last fifteen years. At the cemetery the animal was killed by a gunshot in the head, and the carcase, enveloped in laurel leaves, dropped into her mistress' grave.”

The Lancashire Evening Post, 25th August 1924 gives an account of another feline funeral: A CAT’S FUNERAL. The funeral of “Nichalou,” an Angora cat was held in Eden Township, Michigan. The cortege included only his owner, Mrs. Fred S. Noyes. The owner s(says the “Daily Courier”) purchased a dainty white brocaded casket, line with finest silk, from a local undertaker. There were flowers – roses and carnations. Nichalou had lived for 17 years.

The Democrat and Chronicle , of February 17, 1901, suggested that a personal cat cemetery was the result of a “Strange Mania” of a reclusive elderly woman abandoned by her husband: “In Piermount, in Rockland county, there Is a cat cemetery, established by Mrs. Annie Adamson, 80 years old, whose funeral took place yesterday. The woman had a singular mania, for cats. She always kept dozens of them. Some years ago she set apart a plot of ground for a cat cemetery. As her cats died, from old age or good living, they wore buried with ceremony - the eccentric old lady shedding tears for them. Favorites were put in satin-lined coffins and got small marble headstones. Hundreds of cats have been buried in the Adamson cat cemetery. When Mrs. Adamson was taken sick and felt the end approaching, she gave instructions that all of her felines should be chloroformed and buried in her cat cemetery. Many years ago Mrs. Adamson’s husband went to Cuba and disappeared. Grief over his disappearance, it is thought, unsettled her mind.”

People in Piermont had a habit of dropping bags of unwanted kittens over Mrs. Adamson’s fence, knowing that she would look after them. She had feared that her remaining 16 cats would have a hard time after her death and that the kindest thing would be to chloroform them rather than turn them out into the world.

In 1911, when William Gray Brooks, a Philadelphia millionaire, lost his Angora cat “Tiger” he had the cat buried in a silk-lined mahogany coffin with its head on an embroidered satin pillow and taken for burial in the cat cemetery at Radnor. The attaches at the Morris refuge for cats sent out funeral invitations to Mr. Brooks’ neighbours and so many of them responded that the cat cemetery was overcrowded. How many of them went to pay respects to Tiger, and how many of them went because Tiger’s owner was a millionaire, was not reported.

One of the most detailed accounts of an American feline funeral comes from The Piqua Daily Call, April 30th, 1904, under the headline “The Famous Cat Of W. P. Buchanan.” This detailed the last illness and the funeral of a cat that had become its owner’s business mascot. “Friends of the Buchanan family will be interested in this story of the pet cat of W. P. Buchanan that recently died in Philadelphia: The many friends of W. P. Buchanan, of Philadelphia, will remember that Will's cat, “Grover B." was used by him as a mascot on all his office stationery. With the cat came fame and fortune, and the genial Will is now a rich man, and his fame as a dealer in photographic supplies worldwide. The following from the Philadelphia Press, as given by the Covington Gazette, will read with interest:

Mourned by a large circle of admirers, Grover B. died on Wednesday after a two weeks illness. He was attacked with pneumonia and despite the efforts of two skilled physicians to relieve him, he failed to rally and the household in which he had made his home for nineteen years now mourns his loss. Grover B. was only a cat, but he was a cat with a reputation and was known all over the civilized globe. He first achieved prominence in when he took the gold medal, the only one of the kind offered, at the cat show in Madison Square Garden, in New York, it was the prize given to the handsomest cat in the show and he well merited the honor. Grover B. was a white Maltese. He was imported by his owner, W. P. Buchanan, when only five weeks old. Mr. Buchanan brought the kitten from the Island of Malta and carried him ashore in his overcoat pocket. When he was exhibited at the cat show he weighed nearly thirty pounds and also took a second prize on account of weight, only one cat exceeding him in avoirdupois.

From Wednesday until Saturday morning Grover B. lay in state in the parlor of his master's home, 3514 North Twenty-second street. He was extended on a satin pillow and placed on top of the white enameled cage in which he was exhibited in New York. A silk shroud trimmed with lace covered the pillow and the body was surrounded with flowers sent in by his admirers. Hundreds of persons called to take a look at the body. Nearly all brought flowers. Many of the visitors were school children. The last set of callers were twenty-seven school children, who came in a body to take a last look at him. Yesterday morning the body was placed in a handsome mahogany casket, with a silver plate on the lid, on which was inscribed “Grover B. aged 19.” A grave had been prepared under a tree on the front lawn, in the shade of which he was wont, in pleasant weather, to take his station and watch for the return of his master. Here he was laid to rest. Mrs. Cleveland is the owner of a fine life-sized picture of the celebrated cat named after her husband. Grover B. was the first animal to be photographed by the flash light. This was in 1887.”

COMMEMORATING FELINE COLLEAGUES

Working cats, as well as pets, were buried in a dignified manner by their human colleagues. Here’s an account of the funeral of American store cat Thomas from The Lancaster Daily Intelligencer, April 17, 1882:

“People who passed the large store of Howland & Co., at 1203 Market Street last evening, were surprised to see it closed much earlier than usual and a badge of deep mourning hanging from the knob of the front door. Those who were acquainted with the firm knew that none of the members had been sick and were therefore amazed to see the crepe at the door. It was learned, however, upon inquiry, that the deceased was not a member of the firm, nor a clerk, nor an errand boy, but was a large Thomas cat. The cat had been a great favorite not only with those in the store but with the customers who daily frequent the place. It had been taught to do almost everything but talk, and it is even claimed that it could talk, not in the usual way, but with its eyes, making known its wants very easily by the intelligent expressions in them. All the neighboring merchants knew "Tom", for although six months old, he was of immense size and had a coat of fur as soft, smooth and beautiful as sealskin.

Of late, however, "Tom" had become enamored of a comely Mariah cat living in the neighborhood and took frequent strolls with her over back sheds and roofs whenever he could get out at night. On Thursday evening, evading the eyes of those in the store, "Tom" started out to spend the evening with his enamorata and to take what proved to be a fatal walk. Instead of perambulating the roofs, as usual, the two decided to see the sights along Market Street. Side by side, with an occasional affectionate me-ow, they walked up and down Market Street until nearly morning, "Tom" valiantly keeping off the many intruders who were desirous of winning a favorable glance from his love. During a slight difficulty which arose during a discussion with a brother feline, Tom was run over by a passing wagon and was found dead in the morning by some of the store hands.

There was great mourning in the store over the death of "Tom". His body was taken to an icehouse, where it found a temporary resting place. A handsome coffin was made, covered with black cloth and adorned with four heavy nickel-plated handles on each side. The remains were placed in this and laid out in state in the back of the store. The body was viewed by a large number of persons. It rested naturally, with its head on a pillow of flowers and floral tributes surrounding it on all sides. The front paws were crossed over his breast and the back ones bent up to his side.

The funeral in the evening was all pomp and ceremony. The little coffin was borne down the cellar steps to the Dead March, whistled by a quartet of mourners. Fully twenty-five people watched the earth fall on the flowers on the coffin lid, which was inscribed on a nickel plate, "Sacred to the memory of Tom; died April 14, 1882, aged 6 months." A stone with a suitable inscription will be placed over the grave.”

The Dorking and Leatherhead Advertiser, 5th July 1894, reported the death of a much-loved railway cat, and its funeral, in ‘RAILWAY ACCIDENT AT DORKING – LOSS OF LIFE - As one of five excursion trains conveying some 2,000 passengers, being about half of the employes of Messrs. Huntley and Palmer's biscuit factory, from Reading to Margate, was passing through Dorking, it ran over that notable prize winner, the Station cat. About , three years ago Tom strayed as a kitten to the station. He was asked, “how d’you fancy Hawkins for your other name?’’ and Mr Hawkins, one of the staff, henceforth took principal charge of the visitor, though other station employes considered they also had a kind of common property in him. In due time the I cat rid the various buildings of rats and mice, which had infested them, and so far profited by the exercise and the refreshment thus afforded as to develop a splendid size and appearance. He took first prize at a recent Cat Show at Reigate. At a Guildford show he was highly commended. Tom was quite at home among the trains and would follow Hawkins up the signal post ladders, or anywhere else. A railway man saw Tom almost directly after he was run over and put him out of his pain at once. The funeral took place in a spot near the signal post endeared to the deceased by many associations of captures effected close by.’

The Evening Express, September 27, 1898 gives us a comparison of a hoarder’s unmourned cats taken by the London dustman and a much loved railway cat in Shadwell :

'TALES OF TWO CATS. Sad tales were those published in the "Evening News" recently of 200 dead cats, whose interment was left to the dustman. Skinned and unmourned they went down to their common grave. Far different was the fate awaiting the remains of the run-over cat of the London, Tilbury, and Southend Railway Company. As the train going out of Fenchurch-street passes Shadwell Station an object near the wall catches the passenger's eye. It is "Timmy's" grave. Now "Timmy" was a beautiful tabby torn, the pet of the station, who received his daily share of meat from the signal-box boys at Shadwell. For months he had kept the signalman company at night, but on one fatal morning, before dawn, pussy left the cosy signal-box, whether on pleasure or on business bent will never now be known. His mangled remains were found in the morning, where he had evidently been caught by a passing goods train, and opposite the signal-box, the scene of his former happy life, poor puss was buried. There used to be a headstone to the grave and on it was the inscription, "In memory of Timmy; died July 1, 1897." The station-master, however, who did not believe, with the Rev. Forbes Phillips of Gorleston, in a future existence for animals, contended that the headstone was a mockery, and ordered it to be removed. Four little green posts, picked out with white, bearing a chain border, now mark the spot. The grave is concreted over. and it is alleged by a local humorist that this is due to the extraordinary behaviour of another cat, who once tried to dig up the body, maintaining that it was that of a lordly Persian, and not an ordinary tabby as generally supposed. Mrs. Tortoiseshell, it is understood, is now endeavouring to obtain a faculty. Further down the line, at Limehouse Station, is yet another railway cat's grave, but the passing of years has obliterated the inscription. According to the popular legend this also was a tabby, the property of the station-master. She met her death whilst watching a rat-hole near the metals. So intent was she upon her prey that the engine was on her before escape was possible. For fifteen years the little plot has been kept trim and neat by the station officials.'

“A Cat’s Funeral. Minnie, a cat which had been the pet of the firemen in the engine house, at Sixty-first Street and Haverford Avenue, Philadelphia, for eighteen years, ever since she was taken there as a kitten, died recently, and was buried in a silk-lined coffin, 200 firemen being present at the interment. The cat had ridden to every fire in that district ever since she became a member of the fire company.” (Belfast Weekly News, 12 September 1912)

NOT IN OUR CHURCH YARD!

The Philadelphia Times, June 19, 1882, having read the reports of the Zoological Necropolis Company (about which, more later), wondered if pet cemeteries were needed in American towns. “The question of decent burial for dogs and cats is assuming an importance which attracts the interested attention of friendless spinsters and married women without offspring. As the case now stands, defunct pets must either be handed over to the scavenger, planted in the back yard, ‘interment private,’ (hidden] with subsequent harrowing suspicion of bad air in the second-story back bed room, or carted away to some quiet suburb, with a following of mourners which suggests a quiet family picnic. Mrs. Kelley, of Washington, has boldly solved the difficulty by having her pet dog’s carcass interred in the public cemetery, with all the formalities of hearse and undertaker, burial permit and funeral procession of mourners fully as inconsolable as they would have been at the taking off of a rich and generous relative. In fact, there seems to have been nothing wanting to make Mrs. Kelley's dog’s obsequies complete in all the requirements of a first-class funeral, save the presence and professional services of a clergyman or of some sympathetic priest of pantheism with eloquent remarks about the trees, the flowers and the stars, and the doubtful possibility of good dogs finding a happy hunting ground beyond the grave. But the lot-owners in the Washington Cemetery took a dismally practical view of Mrs. Kelley’s dog funeral. They didn’t wish the bones of Mrs. Kelley’s lost dog to be mistaken for the contents of their own family vaults. They held an indignation meeting and protested against the desecration of their cemetery and they demand the removal of the dog, and the dog will have to go, in spite of the fact that in all the qualities which compel affectionate regard and remembrance be may have been superior to a large proportion of the human beings whose final resting-place he is supposed to pollute. We must either organize dog and cat cemeteries on the plan of the London “Zoological Necropolis Company,” or someone must start a crematory for animal pets, so that inconsolable masters and mistresses may find their grief assuaged by contemplating the ashes of their departed darlings.

Some reports describe outright public outrage at a pet being buried in consecrated ground. Should a cat - once the familiar of witches - be interred in the local burying ground? "A Cat’s Funeral” in The Edinburgh Evening News of September 17, 1885 gave an account of an elderly woman in Abercromby Street who wanted to give her cat, Tom, a “decent burial.” The local undertaker built a suitable coffin and Jamie, the local gravedigger, dug a grave for Tom in the local burying ground. It resulted in a riot and the desecration of the coffin would have been distressing for an elderly, bereaved cat owner:

“A CAT'S FUNERAL. A somewhat unusual scene was witnessed in Street and Clyde Street, Calton, Glasgow, Tuesday afternoon, caused, it would appear, by the interment of a Tom cat belonging to an old old woman residing in the first named street. Tom, who it appears was a special favourite with his owner, died a couple of days ago, and the good woman resolved that he should get a decent burial. She accordingly applied to a funeral undertaker in the neighbourhood for a coffin, but the undertaker, not having one suitable for the canine species, caused one to be made specially for the occasion. During the past two days the house has been visited by large number curious youngsters, for the purpose getting a glimpse of the body of the cat before it was consigned to its last resting-place. As the good lady had a lair [plot] in Clyde Street burying ground, she employed "Jamie " to make a grave for Tom, and the funeral, which took place in the afternoon yesterday, was largely attended. Miss --carried the coffin, and on the way to the graveyard the crowd of youngsters who followed became exceedingly noisy, and being apprehensive that the affair would end in a row, "Jamie" closed the iron gate with the view of preventing any but a select few from entering. The crowd, however, became even more excited, scaled the wall, hooting and yeiling vociferously, crying that it was shame and disgrace bury cat like a Christian. The coffin was afterwards smashed, and the body of the cat taken out, and ultimately the uproar became so great that the police had to be called to protect the gravedigger and the old lady. The latter managed to get hold of the dead body of Tom, and with the assistance of Constables Johnston and Smith escaped into a house in the neighbourhood, where she remained for some time. In Abercromby Street, where she resides, a number of policemen had to kept on duty till a late hour order to protect her from the violence of the crowd.”

Less violent, but just as upsetting for the owner, was this refusal from a cemetery in the USA. In Atlantic City, according to the Pittsburgh Daily Post of December 22, 1912, “Mrs. Katharine Carter of New York, a guest of a South Carolina avenue hotel, is incensed over the refusal of trustees of the Atlantic City cemetery, in Pleasantville, to permit Tiger, a pet cat she valued beyond price, to be interred in the burial ground. Tiger died Tuesday, and its owner purchased a casket of rosewood, trimmed with German silver, and arranged for an ostentatious funeral. These plans were halted by the attitude of the cemetery officials, who said that cats and dogs equally were barred.”

Why would vicars, priests and pastors conduct animal funerals if religious doctrine said animals had no souls? Not all believed that doctrine and even those who did may have conducted a service to give solace to the owner. Nowadays there are special church services for blessing (living) pets, but an old joke suggests financial motives when it came to religious funerals for pets. An elderly lady (naturally) wanted a religious funeral for her pet cat. The Catholic priest refused to conduct an animal funeral so she tried the Anglican vicar and then the non-conformist pastor. Having been turned down by all three, she mentioned to the priest that she had planned to give the church a handsome donation. The priest said “My dear lady, why didn’t you tell me that your dear animal companion was a Catholic? Of course I’ll conduct a service for him.” Nowadays there are written services for pets in accordance with Christian, Jewish and Muslim traditions.

In Drexel, Mo., a cemetery that refused to bury a small dog at the foot of a human grave lost a considerable sum of money. The St Louis Post Dispatch, March 28, 1909 ran a lavishly illustrated three-quarter page spread on the debacle. While the cemetery trustees stuck to its guns, they also lost out on a very large sum of money and the patronage of a wealthy family.

“Because of a little six-and-a-half-pound dog the Cemetery Association of Drexel. Mo., is to lose $10,000. Not only will it lose the money, but it will lose the good will of William D. Corbin, a wealthy oil man of Kansas City, and the bodies of his 10 relatives who are buried there. The dog was buried in Sharon Cemetery in Drexel and the people objected. They didn’t know Mr. Corbin intended to leave the cemetery enough money when he died to support it for many years to come, and so they made their objections very public. Now, Mr. Corbin has retaliated by taking away the body of the dog and the gift which he intended leaving the cemetery. He is also building a handsome mausoleum in one of the finest cemeteries of Kansas City, and will there bury the bodies of his relatives now at Drexel.”

This dog took the place of the couple’s only child, who had died in infancy. For 17 years it had gone everywhere with Mrs. Corbin and the childless couple wanted their canine child to remain part of the family after it died.

“An undertaker was called, the best in the city, and Fritzi was prepared for burial. There was a shroud and Mr. Corbin picked out a metallic casket for the dead pet. Then, the body was taken to a train and carried to Drexel. The solemnity of burial didn't end there. There were ceremonies of a kind at the grave and the little dog was buried at the feet of the grave of Mrs. Corbin’s only child. They saw nothing wrong in that. It was their lot. Besides, Mrs. Corbin had buried several canary birds of which she was very fond in the lot and no one had objected. In fact, they never thought that such a thing as an objection would ever be raised.”

The couple returned to Kansas City, and a few days later Mr. Corbin received a letter from the trustees of the cemetery at Drexel ordering him to remove the dog or it would be removed for him. In response, he notified the trustees that Mrs. Corbin had buried two canaries in the cemetery, so that they could know it and order their removal also. Then he told them that he was very glad to hear their views in regard to the matter, because he had had something in mind about the cemetery in case he died and he was happy to know he had found out what he did before he died. Then he told them that he would remove the dog.

"I don't see how any objection could be raised to the burial of the dog, he wrote. It was placed in a metallic casket and was buried at the foot of my little son. It was buried in the family lot and near 10 of my relatives.” He said that he had more relatives buried in the Sharon Cemetery than anyone else and that he would remove them to a private mausoleum. Then he dropped the bombshell: “I also wish to state in this letter that I had set aside $10,000 which I intended to bequeath Sharon Cemetery when I died. Nothing pleased me better than to find out about the community before it was too late. I naturally withdraw my bequest.”

The trouble had apparently been stirred up by a preacher. Although Corbin’s relatives were welcome to stay in the cemetery, the trustees insisted upon the removal of the dog (no-one mentioned the canaries) and Fritzi was temporarily interred on a farm until the Corbin mausoleum was built.

As a footnote, in January 2010, West Lindsey District Council gave permission for a site in the village of Stainton by Langworth (Lincolnshire) where animals can be interred alongside humans as part of a "green burial" site. This is the first place in England where pets can be officially buried alongside their owners.

A LAVISH CEREMONY

In April 1913, The Brooklyn Eagle (overlooking the eccentricities of its own country) commented on the eccentricities of British pet owners thus: “British society women are getting more and more eccentric in the attention that they bestow upon their dead pets. One titled lady keeps in a prominent position two dead dog pets embalmed in glass coffins in her drawing room. Certain London undertakers reap a considerable part of their income by making coffins for pets. These are often satin lined, the animal's head rests on a satin cushion, and maybe its ‘face’ is covered with a lace handkerchief. Wreaths and flowers are used, and where burial takes place in a cemetery a hearse is sometimes engaged, with mourning carriages following. The monumental masons also benefit. Many people prefer cremation for their pets, and there are any number of veterinary surgeons who have a crematorium fitted up. In some cases the ashes, canine or feline, as the case may be, are inclosed in a beautiful jeweled urn. A favorite bird is sometimes buried in a bed of cotton wool. The well-known pets' cemetery in Hyde Park is now full, but there are plenty of similar cemeteries throughout the country. There is one, for instance at Huntingdon, and another at Haverhill, in Suffolk. In addition to this, there are hundreds of gardens in London where headstones marking the last resting place of some departed pet can be seen.”

Here's a description of a lavish funeral in Chicago, USA in 1903, excerpted from "Mr Toots Is Dying" in The Inter Ocean, December 23, 1900 [Newspapers.com]. The cat in question was the pet of a temperance and women's suffrage campaigner and symbolic to her followers.

"When the late Frances Willard’s old pet cat shuffles off this mortal coil no touching epitaph, will mark his grave and perpetuate his memory to future generations. Mr. Toots is not to have the old-fashioned, orthodox burial, but is to be cremated, according to the most approved and up-to-date methods. When he dies ha will be accorded every honor that so venerable and highly respected cat deserves. When Toots is stretched upon his bier a small real-lace handkerchief will cover his face. On the day of the funeral, his body will be wrapped in a winding sheet of white silk and placed upon a slab, which will be solemnly shoved into the big furnace that supplies heat to the Norton mansion. When Tootsey’s friends view his remains each one will sprinkle a little myrrh or frankincense over the body – a much more beautiful rite than the one of dropping cold clods of earth upon a casket, in a deep, dark grave – and, while Tootsey’s flesh and bones are being consumed by the fiery furnace, the spicy incense will counteract the disagreeable odor of singed hair which might be emitted through the furnace chimney and which might prove objectionable to Mrs. Norton’s neighbors.

Disposition of the remains of Tootsey Willard was obtained from Mrs. Leland Norton in answer to a question concerning the location of the Chicago cat cemetery. The Inter Ocean had it upon excellent authority that Pussywoods was the name of the burying ground where all the aristocratic, blue-blooded cats in the neighborhood of the city find their final resting place. Mrs. Leland T. Norton said she was not interested in Pussywoods. “No; I cannot tell you anything about the cat cemetery,” she said. “I know nothing about it for the reason that I put all my dead pussies right into the furnace and cremate them. I think it is much the best and most sanitary plan.” Mrs. Norton is obliged to perform this grewsome office every little while, for, besides her cattery, where every variety of the blue-blooded puss is raised, she conducts a cat refuge."

According to The Pacific Outlook (January – June 1907), “Pussywoods” cat cemetery was the invention of a young reporter who needed some sort of story about the ailing Mr. Toots. “It was set forth [in the report] that [Toots] would be buried in beautiful Pussywoods, the cat cemetery, where in time a fitting monument would be erected to his memory. The city editor praised the young reporter for what he called a ‘stickful of human interest,’ but he had reason to regret his appreciation of the first page, double leaded ‘feature’. The day of its publication in the morning edition the telephone rang every few moments and all sorts of voices belonging to bereaved cat owners inquired the location of Pussywoods. Letters poured into the newspaper office and enterprising dealers in tombstones sent in designs for cat monuments. Of course, there never was a Pussywoods, but an enterprising real estate man immediately offered a tract of land for a dog burying ground which he named Fidoland.”

PET CEMETERIES

Because most graveyards did not allow pets to be buried in consecrated ground, pet cemeteries were established, the best known being the Hyde Park Dog Cemetery, opened in 1881. It began by accident as a favor by the lodge-keeper, Mr. Winbridge, but his private garden was unable to take further burials by 1903, by which time it had over 300 graves. The pets were sewn up in canvas bags and Mr. Winbridge interred them. Although the clientele were primarily canine, it also contains two cats and three small monkeys.

In “A Cat and Dog London” written by Frances Simpson for “Living London” (1902), the authoress writes “Comparatively few Londoners know of the Dogs' Cemetery hidden away in a quiet corner of Hyde Park, near the Victoria Gate entrance. This burying ground is not a public one, and does not belong to anybody in particular. Dwellers in the neighbourhood of Bayswater have been allowed from time to time to bury their dead pets here; but the space is now completely filled up, and the custodian has to refuse further applications for interments. The graves in this canine necropolis number about three hundred. The headstones are mostly of uniform pattern. There is one Ionic cross and a broken column. Fresh gathered blossoms mark the spot of the more recently buried pets, all the graves are nicely planted with flowers, and many have short but very touching inscriptions telling of a lost one mourned.” In “The Book of the Cat (1903), Simpson noted “There is a secluded corner in Hyde Park known as the Dog's Cemetery, and amongst the many headstones I noticed two or three erected in memory of lost pussies who have been privileged to rest in this quiet burying ground.”

One feline headstone reads “In memory of our pet cat ‘Nigger’ Dec. 18 1897. Also Bogie May 30 1889, E.L.W.” Another headstone has what appears to be a scholarly inscription, but it is apparently a curse upon the boy who had killed the cat. The lady owner had ordered an inscription which consigned the assassin to everlasting torture, but the authorities wouldn’t permit the monument to be set up over Tabby’s grave. She thereupon consulted a Chaldean student and had the intended inscription translated in that dead language. Since few could read Chaldean, even in London (a seat of learning), the monument was duly inscribed with her curse upon the killer.

When the Hyde Park Pet Cemetery was full, and no further burials were possible at Victoria Gate, the applications for graves was still so frequent that E. Grey of Hyde Park Gate, London, the brother of the lodgekeeper set out a shady piece of grassland adjoining his garden at Molesworth, near Huntington, as a cemetery for pet animals. This cemetery is hard to distinguish from a human cemetery in that the headstones were often equally large and elaborate. The Hon. Mrs. McLaren Morrison, collector and breeder of unusual cats and dogs, buried at least dogs, cats and birds there, and Tommy’s grave ran to 100 inscribed letters, beginning “Tommy, a pet cat from India.” Molesworth received animals for burial from all parts of the kingdom. Some were received in ordinary boxes or packing cases, but many were sealed in polished wood coffins with brass mountings and were delivered from London by the sorrowing – and wealthy - mourner in a motor car, and the bereaved owner would shed many tears over the open grave of the pet she (again, they were usually ladies) is leaving behind. Today, about 75 out of the original 250 graves remain.

Other pet cemeteries, both public and private, were set up in 19th Century Britain. They were primarily for dogs, who were seen as loyal companions, whereas cats were considered fickle friends. Off the main path at Edinburgh Castle is a small garden used as a dogs’ cemetery; it contains regimental mascots and the pets of officers. It dates back to 1840. In fact, it seems that most castles and country houses had a burying ground for favourite domestic animals.

In Bath, England, the Parade Gardens were set out in the Georgian era as a place for the society of Bath to promenade. The Gardens also contain a 19th Century Pets Cemetery. Preston Manor in Brighton, England has a pet cemetery, believed to be the only one in a historic house in Sussex. Four cats and 16 dogs are buried in the plot in the southwest corner of the walled garden.

In order to maintain Elmdon Hall and Elmdon church (Solihull, Birmingham), furniture was made from the estate’s trees. One area of trees was not cut down because the trees protected a of a cat's graveyard cared for by the housekeeper. The graveyard is apparently still there, although Elmdon Hall was demolished in the 1950s. I can’t find much about the cat’s graveyard, but Elmdon Church contains two animal-related headstones from the 1920s, one of which is for a cat (“Josephine. The faithful friend and constant companion of the late W.C. Alston at Elmdon Hall, September 28 1920 much missed by his owner Mrs. Kent.”)

There is a private pet cemetery at seat of Sir Thomas Barrett-Lennard, 2nd Baronet, of Belhus, near Aveley, Essex, dating back to the 1850s (he succeeded to the title in 1857). Sir Thomas kept numerous dogs, cats and other animals. When one of his pets died, it was placed in a coffin and Sir Thomas held a solemn Anglican funeral. The vicar from nearby Aveley officiated and Sir Thomas read prayers. The animal was then buried in the grounds of Belhus. Sir Thomas demanded the presence of his own footmen – in full livery – as pall-bearers. His horses were also laid to rest there. Sir Thomas was definitely a great English eccentric – he fed the rats and rooks on the estate rather than killing them as pests, did not kill the deer on his estate and refused to go foxhunting. He opened his own front door, to save his servants the bother (so being pall-bearer at a pet’s funeral was probably not an onerous task), and his shabby attire led him being mistaken for his own gatekeeper ... and he was once mistaken for an escapee from the local asylum!

The author Thomas Hardy also had a private pet cemetery at his home at Max Gate in Dorchester, Dorset where he lived from 1885 to 1828. He laid the cemetery out himself and even carved some of the headstones. Many of his cats met a nasty end on the nearby railway line.

This brings us back to Timmy the railway cat. The station-master, unlike the Rev. Forbes Phillips of Gorleston , did not believe in an afterlife for animals and called Timmy’s inscribed headstone a mockery, and ordered it to be removed. The station-master overlooked the fact that an inscribed headstone serves as a focal point for the bereaved rather than indicating a belief in a feline hereafter.

THE ZOOLOGICAL NECROPOLIS ASSOCIATION, LIMITED

St. James Gazette in 1882, tells us of the Zoological Necropolis Association, which was intended to be an animal equivalent of the Necropolis Association that carried human bodies to large cemeteries outside of 1880s London:

“ ‘The burial-place for pet animals, dogs, cats, and little birds,’ is emerging from the region of dreams. The prospects for the ‘Zoological Necropolis association (limited),’ which, lies before us with its imposing array of patrons, directors, bankers, solicitors and secretaries, shows that the scheme is being pushed In the orthodox commercial fashion, and anyone who wishes to subscribe can purchase as many of five thousand £2 shares as his inclination leads him and his finances permit. The burial ground is to be established ‘within a few miles of London,’ and, ‘if wished for a tribute to their memory can be erected by those who love them.’ In due time we shall have a cats’ undertaker setting up In business, but for the present it is sufficient to say that the offices of the Cats' Cemetery company are at No. 27 Henrietta street, Cavendish square, W., where all necessary information can be obtained by intending shareholders. “The New York Times of March 23, 1882, gives us much more detail on the intended venture, and suggests it is a juvenile to bury pets with any sort of service. “It has long been the custom of children of pious - and possibly theatrical - instincts to give a juvenile variety of Christian burial to their dead pets. In the latter category dolls are not included, for the doll never dies. It may be, and in course of time invariably is, maimed. It loses its legs and arms, bursts bran-vessels [stuffing], and their yellow flood ebbs away until the doll is reduced to a limp body of useless rag, or its wax head and shoulders are melted by accidental proximity to the fire, and the doll, as a doll, ceases to exist. When its career is ended there is not enough of it left to be buried, and no girl, however deep may have been her maternal affection for the doll of her hypothetical bosom, regards a mass of melted wax or a lot of shapeless rags as having ever had any real relation to her loved and vanished doll.

But with dead cats, dogs, and birds the case is very different. These are living beings, and when the life has gone out of them there is no difficulty in recognizing their bodies as the relics of the dear departed ones. To the childish imagination it seems heartless to cast the dead body of the canary to the cats of the field or to expose the corpse of the lamented pug to the unfeeling cart-wheels of the highway. Hence the solemn burial of dead pets is a frequent incident. There is a devout joy in marching in procession with the body of the mother-cat to her last resting-place under the apple tree and a combination of religion and amusement in singing a hymn at the grave and in committing the body to the earth which gives to many children a sweet, strange vision of a possible church where the service should be almost as nice as play and the sermon as interesting as a story of bears and Indians. In the cities there is, alas, little, if any, room for the burial of pets. The back yard is either closely paved or the cook refuses to allow the little grass plot to be dug up for ‘burying them nasty animals. ‘ It is, therefore, with the purpose of meeting a great juvenile want that certain London philanthropists have organized the “Zoological Necropolis Company,” a society which purposes to provide a beautiful cemetery for the pet cats, dogs, and birds of the metropolis.

It is a question whether, under Mr. Gladstone’s Burial act, cats and dogs cannot be interred in the parish churchyards as well as dissenters, and certainly where a dead positivist can be buried with the ceremonies of his alleged Church, a really pious dog ought to be permitted to be laid at rest with the simple and beautiful burial service which children improvise for such occasions. Nevertheless, it is perhaps well to avoid any further agitation as to the churchyards, and the new cemetery to be provided by the Zoological Necropolis Company will doubtless be all that the most devoted and heartbroken child could desire.

The cemetery is to be in all respects an attractive and commodious city of the dead. Families of children greatly addicted to animals will be able to purchase plots of ground neatly inclosed with railings, in which they can bury a long succession of pet animals; while single graves, either in the cat, the dog, or the bird department can be had at a moderate price. Receiving vaults will be provided, in which bodies can be temporarily deposited, and by special arrangement the larger animals, such as goats, and even horses, can be buried in the cemetery. It has not yet been announced whether the company will supply juvenile chaplains and surpliced juvenile choirs for funerals, but it will encourage the erection of beautiful monuments, and will provide wreaths of immortelles to be laid on the graves of beloved cats.”

Having dismissed the need to bury pets in a dignified manner, The report then takes on a more facetious tone and suggests that pets are given better treatment than the poor and hungry people of the city: “The company will not, however, confine its benevolent interests to the dead. It proposes to provide for the living by establishing a Home for Aged and Infirm Pets. In this Home widowed and friendless cats will be able to end their days in peace, and dogs who have become reduced to poverty and birds who have lost either their friends or their feathers will be comfortably cared for. Everything will be done to the Home attractive to its inmates. For the cats there will be provided back fences where amateur concerts can be held and cellars where exercise and recreation in connection with mice can be had. Dogs will be strictly prohibited from entering the apartments reserved for cats, but they will be allowed at certain hours of the day to worry tramps, provided for the purpose, and terriers will receive semi-weekly rations of live rats. The birds will find their pathway to the grave soothed with sugar and sprinkled with rape-seed, and care will be taken to reclaim profane parrots and to teach them to substitute hymns for oaths. In the interests of morality the doors of the Home will be closed to all applications from tom-cats. The ineradicable tendency to noctural dissipation and the habitual profanity and pugnacity of the tom-cat are so well known that it will be seen that the introduction of two or three of these depraved beasts into a well-regulated Home for Aged and Infirm Pets would soon convert it into a moral pest-house.

It is pleasant to think that amid the distress and poverty which prevail among the inhabitants of Loudon there are men so nobly unselfish as wholly to forget their own race and to lavish money in providing homes and cemeteries for animals. It is to be hoped that the line will not be drawn at pet animals, but that the large intelligence and charity of the Zoological Necropolis Company will include the vivacious flea and the erratic earwig among its future beneficiaries.

The Pall Mall Gazette in April 1882 also reported on the planned Necropolis: “The Zoological Necropolis Company (Limited) is the title of an association the object of which is to provide a “burial-place for pet animals, dogs, pussy-cats and little birds. From the office of the new company, No. 27 Henrietta Street, Cavendish Square, there came to us the other day a circular from which the following is an extract:

“We are anxious to meet and provide for a want which, in this great metropolis of 4,000,000 souls, has been pressed upon us by many people. We propose to establish a burial-ground within a few miles of London, where pet animals, faithful dogs, cats and birds can be placed after death; and, if wished for, a tribute to their memory erected by those who love them. Having heard of your kindly feelings to the animal world, we ask you to permit us to place your name among our patrons. There is no liability, but any assistance will be gratefully received.”

The circular also proposes to establish a home for aged and infirm animals, which would also serve as a depository for pets when their owners are abroad. The honourable Secretaries of the Zoological Necropolis Company (limited) are Dr. J. Harvey and Mr. R. Howard Hutton.

The idea seems grotesque at first, but after all, in spite of its somewhat high-sounding title, the new Necropolis Company undoubtedly seeks to supply an existing want. Those who live in the country have no idea of the difficulty of disposing of the bodies of dead pets in this great stony wilderness of London. There is no receptacle for them but the dustbin, and a person need not be excessively sensitive to shrink from summarily consigning the remains of an animal that may have been almost a livelong companion to the clutch of the scavenger [meaning those people who earned their living selling animal corpses to be rendered for soap]. Everyone has read Byron's inscription to the memory of his dog; but, if Byron had lived as the majority of Londoners live, he would have had to see the remains of his friend carried oft’ in the dung-cart along with all the garbage of the streets. On the whole, therefore, a pussy-cats’ cemetery is not quite so superfluous an adjunct of London life as some may be disposed to imagine.”

The same news reports ran in 1883, seeking investors, but nothing seems to have come of the idea.

PET CEMETERIES IN FRANCE AND AMERICA

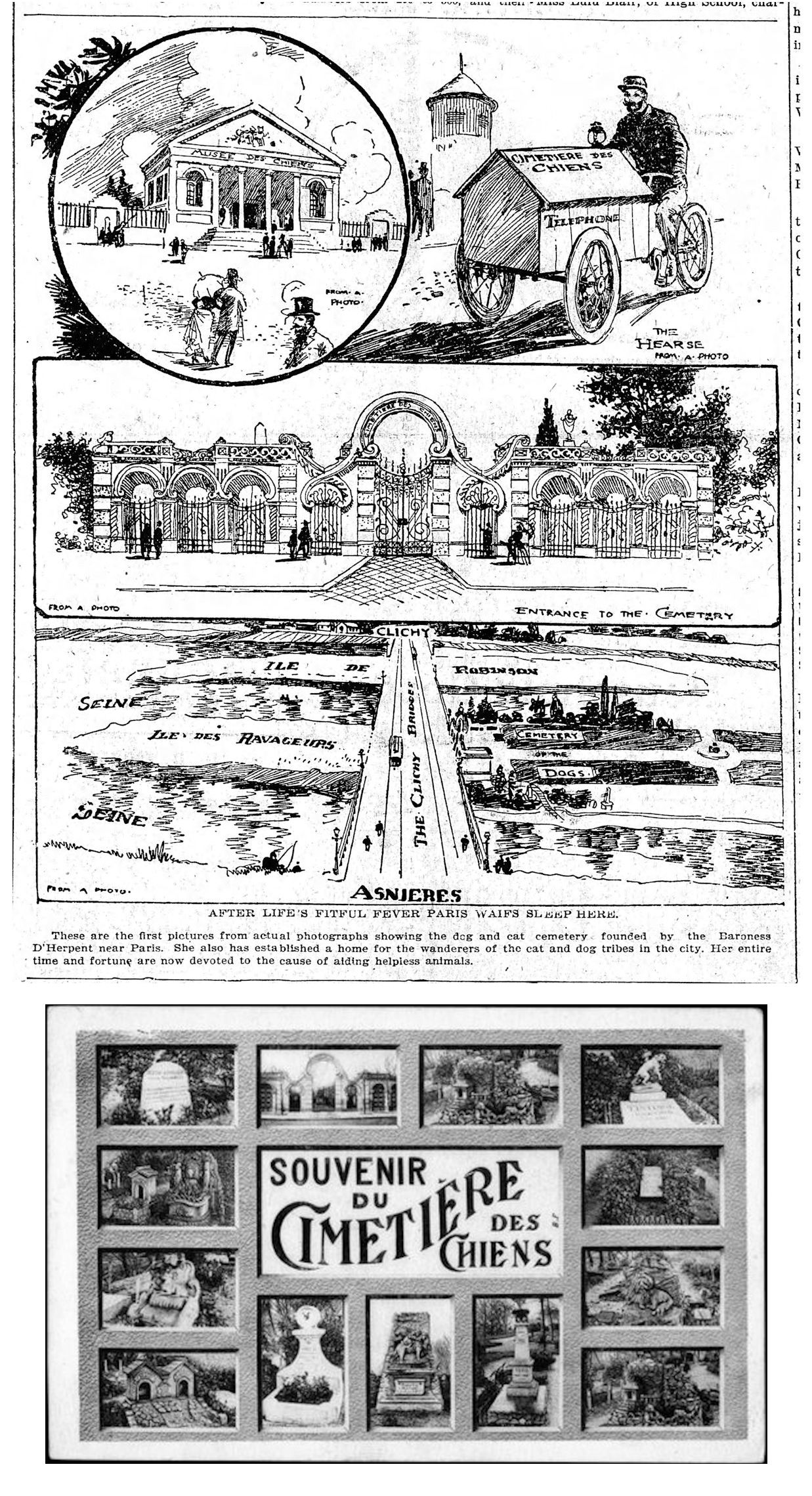

The western world’s oldest public pet cemetery seems to be Paris’s Cimetiere du Chiens, which dates from 1899. A French law passed in 1898 required dead pets to be hygienically buried at least 100 metres from the nearest home. Georges Harmois and Marguerite Durand conceived the idea of a "cemetery for dogs and other domestic animals" on the outskirts of Paris. This started up in June, 1899 on land bordering the river in Asnières-sur-Seine and accommodated not just dogs and cats, but every type of pet, from the exotic to the familiar.

America's largest and oldest pet cemetery is in Hartsdale, New York, dating from 1896 when a Manhattan veterinarian Dr Samuel Johnson allowed a grieving pet owner to bury her dog in his hillside apple orchard. Although known as the Hartsdale Canine Cemetery, cats and other pets are also buried there. Prior to that, animals’ bodies were buried at home or, in the cities, disposed of as waste.

When it was founded in 1898, the Hartsdale dog graveyard was said to be the only one in the USA. Within a few months there had been more than a dozen interments. The credit of the scheme was due to three persons. First, to the Superintendent of the SPCA who had urged the plan; second, to the head of the New York Veterinary hospital, who adopted the idea, and, lastly to a wealthy Hartsdale woman who set aside three acres of land for the purpose and placed the veterinary hospital in control. At first it was simply known as the canine cemetery, but cats were just as eligible for graves as dogs, and three cats of very high degree were buried there within months. The authorities stressed it was not simply a “potter’s field” where an animal could be given a pauper’s grave. It cost $5 to bury a cat or small dog, $8 for a large dog, $10 for a small multi-pet grave and $15 for a large multi-pet grave. Bereaved owners seemed happy to pay that amount to prevent a much-loved pet from being dumped with the city refuse on Barren Island; previously the only option for anyone without a plot of land or sufficient funds to send the deceased to relatives in the country for burial.

The cemetery received the body at the veterinary hospital who embalmed it for burial and shipped it by express to Hartsdale where the sexton of the dog graveyard buried it in a numbered grave. The vet hospital could furnish a plain wooden box at the rate of $1 for a small animal or $3 for a large one, but some owners spent up to $50 on polished wooden caskets with finely upholstered interiors. The New York Sun in November 1898 described a beautiful white Angora cat laid to rest in a box lined with white. It also mentioned owners covering the body with the most expensive flowers to be had. The owners often attended the funeral. All bodies were sent from the vet hospital, not from the house, because the hospital was obliged to know the contents of a box before it was shipped to cemetery. Some owners wanted to see the body before it was finally interred, either to say a final goodbye or to reassure themselves that it really was their pet in the casket.

In Iowa, in April 1900, the city council contested some of the expenses in the clerks’ books. One of the bills was 50 cents, charged by Charles Heyek, for a cat burial. Another was for $1, charged by John McQuiston, for a dog funeral, including killing the dog.

The Kansas City Journal, in July 1900, tells us of a pet cemetery, Dell Wood, located on the east bank of the Hudson river, near the town of Stockport in Columbia count, new York. It comprised around 110 acres of land and received pet animals from all over the country. The article mentioned a sum of $150 to pay the burial expenses of a dog. It claimed to be the only cemetery of its kind in the country.

In 1907, Boston had the “Newton Pet Cemetery” which was for the use of the poor flat dweller who had nowhere to bury a beloved pet. Without such a burying ground, the deceased would have to be thrown in an ash barrel or back yard midden. In November 1908, a 19 acre cemetery for “aristocratic dogs and cats of Chicago” was planned, although its proposed location was not initially revealed in case of objections in the neighbourhood. John J. Millar had an option on a site and Mayor Busse instructed his assistant to draw up an ordinance making the burial ground possible.

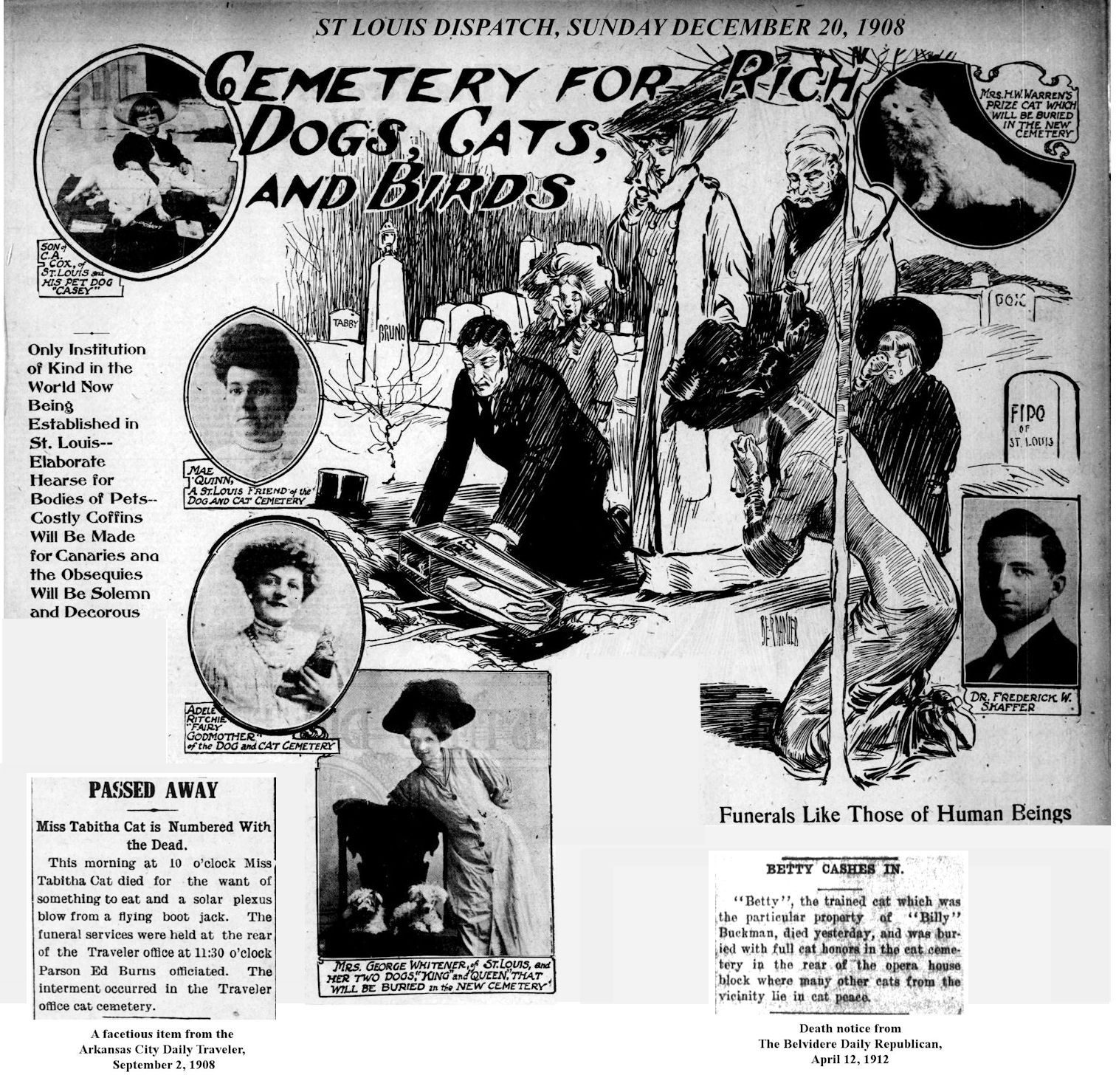

The St Louis Post Dispatch, December 20, 1908, tells its readers that a cemetery for the burial of pet animals would be ready in St. Louis in January 1909. It claimed it was the only cemetery in the world for the interment of birds and animals, basing this claim on the fact that the Hyde Park cemetery was only for dogs, and a cemetery in Paris, France was a small plot owned by an aged spinster rather than a public cemetery. The St. Louis Dog, Cat, and Pet Cemetery was the idea of Dr. Frederick Shaffer who was already receiving applications from around the United States and one from Europe. Dr Shaffer had bought a funeral car (which would be drawn by two white horses) and promised funerals exactly like those of humans except “there will be no service of any kind.”

In July 1915, The New York Times carried an account of a cat and dog cemetery opened for pets of those who worked at the Bide-a-Wee Home, 41, East Thirty-eighth street, New York. The 15 acres of land was to be the shelter’s Summer home, and 5 acres of this were set over to the cemetery. A permanent plot could be purchased for $25. The article then listed several of the society set who had already bought plots there. And in 1916, according to the Indianapolis Star (April 9th, 1916) seven acres of land on a gentle slope adjacent to the Upper Gulph road were being used as a burial place for around 100 pet dogs and 3 pet cats.

TAIL END

As a slightly irreverent footnote, this comes from New Zealand’s Wanganui Herald of 20 April 1904. ‘Who should pay for a cat's funeral? This was a question that cropped up at the Borough Council meeting last evening." It transpired that a burgess had sent word to the rubbish contractor to remove a dead cat from opposite his dwelling, and that official yoked his horse to his cart and - driving to the place - did as requested. Now the contractor has a grievance, as the burgess refused to pay for the cost of removal - or, as one councillor facetiously put it, he "declines to pay for the funeral of the cat." ‘