THE DOMESTIC CAT - ITS HISTORY AND VARIETIES.

Serialised in "The Queen" 1872 – 1873, illustrated by Harrison Weir.

(This also includes some of the correspondence provoked by the articles)

THE DOMESTIC CAT - ITS HISTORY AND VARIETIES. [GENERAL INTRODUCTION]

If we wish to trace the history of the domestic cat from the very beginning, we must of necessity go back to a very early period. According to the time-honoured formula, we may state that the domestic cat "was known to the ancients." The cat-headed deities of the Egyptian room in the British Museum are familiar to most of us. Pasht, the strange weird goddess, sits there with cat-like face, as sleek, as polished, and impassive as when the Egyptian sculptor left her, long ere Moses was found floating in the rushes. The cat was to the Egyptians a sacred animal, constantly delineated on their monumental drawings, and even preserved after death by being mummied. At the present time unrolled specimens of the mummies of cats of the time of the Pharaohs are to be seen in the Egyptian galleries in the British Museum, and this not of one species, but several, some of which were wild, others domesticated. It is nevertheless strange that the Jews, who must have been acquainted with this animal during their residence in bondage, have never once mentioned the cat in their sacred writings, unless we regard an allusion to the wild animal in Baruch to stand as an exception.

Although the wild cat, with its short truncated tail and coarse fur, is undoubtedly a native of our own country, the domesticated animal, which must in the first instance have been imported, was in the earlier ages comparatively rare. It is stated that in the time of Hoel the Good - one of the Welsh princes, who died in the year 948 - laws were made to regulate the prices of animals, and that the cat was included on account of its scarceness and great utility. The price of a kitten before it could see was fixed at one penny; till proof could be given of its having caught a mouse, twopence; after which it was rated at fourpence, which was a great sum in those days, when the value of specie was extremely high. It was likewise required that it should be perfect in its senses of hearing and seeing, should be a good mouser, have its claws whole, and, if a female, be a careful nurse. If it failed in any of those good qualities, the seller was to forfeit to the buyer the third part of its value. If anyone should steal or kill the cat that guarded the prince’s granary, he was either to forfeit a milch ewe, her fleece and lamb, or as much wheat as, when poured on the cat suspended b its tail (its head touching the floor), would form a heap high enough to cover the tip of the former.

It may be remarked that those naturalists who have studied the subject believe that our domestic cat is descended not from one, but from several species. Thus, in the north of Scotland the cats partake of the character of the native wild cat (F. sylvestris); in South Africa the domestic cat crosses freely with the wild cat (F. caffra) of that country; in Algeria with the F. lybica. In India, according to Mr Blyth, who has especially worked at this subject, four species have crossed with the domestic race, whi1st the markings of F. chaus, utterly distinct from the coloration of European cats, are common in Bengal. In fact, every country seems to possess a marked breed. The cat of Ceylon is small, with a "low-caste" head, retreating forehead, and large ears; that of Paraguay (where it has been introduced some 300 years) has short hair and a lanky body; at Mombas, on the east coast of Africa, the cats are covered with short stiff hair instead of fur; in the Malayan Archipelago they have truncated tails; in China there is a breed with drooping ears; and in Asia is the well-known Persian breed or Angora breed. Mr Darwin, in his work on the "Variation of Animals," states that he has seen some very singular cases. He mentions that a cat was born toothless, and remained so all its life; another, belonging to Mr Tegetmeier, with fangs an inch in length, that protruded beyond the lips. He also mentions a family of six-toed cats; and states the singular fact, related by Daubenton, that in domestic cats the intestines are wider, and a third longer, than in wild cats of the same size - a, change effected by their feeding for generation after generation on less carnivorous diet. –

The different varieties of the domestic cat are now exciting much interest, and the annual cat show is one of the greatest attractions of the Crystal Palace. We purpose therefore to illustrate all the more important varieties, by the aid of the facile pencil of Mr Harrison Weir, and we commence with a remarkably long-limbed variety from the Azores, which was successfully exhibited at the last Palace show.

THE SIAMESE CAT

Our illustration represents the singular variety known as the Royal Cat of Siam - a breed regarded as exclusively the property of the reigning family of the country, and which is found nowhere but in the immediate precincts of the royal residences. The variety was specially imported by Lady Dorothy Nevill, and has remained in her ladyship’s possession during the entire period of its residence in England. The characteristics of the variety are peculiar. The hair is very short and close in texture. The ground colour of the fur is a rich cinnamon brown, shaded with black on the back. The ears, the nose, the feet and the tail are black, whi1st the under parts are bright cinnamon. The size of the animal is of the ordinary dimensions. This species is very domesticated in its habits. When imported into this country the Siamese cats are not given to poaching or straying far from home, and for their singularity and beauty they may be regarded as a valuable addition to our limited stock of small feline animals. The cat portrayed took the prize in the class for foreign variety at the last Palace show, and, from its singularity and beauty of colour, well deserved its position.

THE AZOREAN CAT

The Azorean cat, figured in our number for Nov. 23, took a first prize at the last Crystal Palace show. It was imported from the Island of Terceira in the Azores. In the form of the body it was very remarkable, every part being elongated - even the head was long, as were the limbs and tail; and its short close fur added considerably to the slender appearance of the lengthy limbs. The colour was a nearly uniform purplish slate.

THE ANGORA OR PERSIAN CAT

The Angora or Persian Cat is one of the most beautiful, if not indeed the most beautiful, of all the domesticated varieties of the genus Felis, and, at the same time, is one of the most distinct of all the reclaimed breeds. Its wild origin is not very definitely ascertained, although the eminent naturalist Pallas, without any good evidence, regarded it as descended from a wild species inhabiting middle Asia, and known as Felis manul. Be that as it may, the domesticated Angora crosses readily with our common cats, and half-bred specimens are well known.

The most distinguishing character of this lovely variety is the long silky nature of the fur, which is of the softest and most exquisite texture. The expression of the face corresponds, being soft, placid, and almost fairy-like. In habits the Persian cats are very domesticated; indeed, from their extreme beauty and pecuniary value they are more generally kept as pets than as useful animals. In colour they vary very considerably, but those that have their fur of an immaculate whiteness are certainly the most lovely. Many of these white Angoras have the eyes perfectly blue, in which case the animals are almost invariably quite deaf. This fact has long been known. In 1829 the Rev. W.T. Bree, of Allerby, writing in the ‘Magazine of Natural History,’ stated that –

Some years ago a white cat, of the Persian kind (probably not a thoroughbred one), procured from Lord Dudley’s at Hindley was kept in my family as a favourite. The animal was a female, quite white, and perfectly deaf. She produced at various times many litters of kittens, of which, generally, some were quite white, others more or less mottled, tabby, &c. But the extraordinary circumstance is, that of the offspring produced at one and the same birth, such as, like the mother, were entirely white, were, like her, invariably deaf; while those that had the least speck of colour on their fur, as invariably possessed the usual faculty of hearing.

Since then many other observers have recorded the same circumstance; but it is remarkable that when only one eye is blue the cat hears perfectly. It has also been remarked that in cases where the eyes of white kittens have continued blue, as they sometimes do from four or five months after birth, and then changed to a dark colour, they also remained deaf until the period of the change. The explanation of this singular fact respecting the connection of blue eyes and deafness in cats is due to Mr Darwin. He has remarked kittens during the first nine days of their lives, when their eyes are completely closed, and are not only blind but perfectly deaf. Mr. Darwin states that he has made a great clanging noise with a poker and shovel close to their heads, both when they were asleep and awake, without their evincing the slightest sign of their hearing the sound, care being taken not to strike the ground, &c., on which they are resting, so that they should be roused by any vibration. Before the eyes of a kitten are naturally opened they are always blue, and consequently it may be imagined that when the eyes remain blue they are arrested in their development, and see more or less imperfectly; and it with Mr Darwin we imagine the nerves of the ears to be in same immature condition as those of the eyes in these blue-eyed beauties, we have at once an explanation of the deafness. From our own personal knowledge we can testify to the fact that white Angoras not blue-eyed are not deaf, nor are white cats with unmatched eyes, viz., one blue and one of some other colour, as orange-brown, &c.

Angora cats require rather delicate feeding – a little meat, sopped bread or soft biscuit and milk, a little crumbled potato and milk or gravy, &c. They should not be too freely supplied with meat, or the skin is apt to become irritable.

THE PERSIAN CAT.

The Queen of Dec. 21 contained an article on Persian cats, which was particularly interesting to me, as I have grown very fond of an exceedingly beautiful specimen of this breed of cats. The animal I refer to has been for some years domesticated in our family, and its beauty, gentleness, and caresssing ways have rendered it a great favourite. It is a very handsome animal, of a larger size than the common cat, and its fur, of a dark tawny colour, beautifully striped with black, is extremely long, soft, and silky. The tail is magnificent, quite different from that of the ordinary breed of cats, being almost as long as the body, very thick, and covered with long fur. The throat is covered with very soft fur, of a much lighter shade than that on the body, and this throat fur forms a regular ruff, and is one of the striking beauties of the creature. The countenance is really lovely, the expression being at once intelligent and gentle. The large, soft, liquid eyes seem to speak, and are full of sweetness; their colour is green hazel, changing somewhat in tint, according to the light. The movements of this cat are peculiarly graceful; he is akin to the leopard in the litheness and beauty of his form, and all his attitudes are elegant. He is very fond of warmth, and delights to stretch himself at full length on the hearth-rug before the fire, and then to roll over and over, which is a movement that he always expects will attract attention and caresses. He would be very much hurt and disappointed if he did not receive such. Indeed, he is so accustomed to be petted and made much of, that I believe the want of such attentions would seriously affect his health. He is a very sensitive cat, and attaches himself strongly to some people; he is very susceptible to kindness, and equally resents harshness or cruelty. I had rather doubted the capability for attachment in cats; but on becoming well acquainted with this one, I decided that at least one cat could feel affection for those who were kind to it. Our Persian pussy came to the house at about the age of two months. Soon after its arrival it fell seriously ill of bronchitis, and there appeared little chance of its life being saved. It was taken in charge at this crisis by my mother, who had a great reputation as a nurse, and she certainly justified her reputation in the case of pussy. She kept it entirely in her own room and tended it like a baby, putting a few drops of warm milk down its throat when it could at all swallow, and doctoring it very judiciously. By degrees the poor little animal began to recover, and its affection for its preserver was quite touching. She petted it and it responded to her caresses like a child, and was evidently very happy with her. If separated from her for a while it never failed to recognise her on her return, and to testify its joy at seeing her again. One of its manifestations of devotion was really curious. We were living in a country place which swarmed with rabbits, and soon after arriving at this new abode the Persian cat caught and killed a rabbit. It was so proud of the exploit, that it dragged the dead body of the rabbit up two flights of stairs to the door of its mistress’s room, scratched and mewed until the door was opened, and then triumphantly deposited its prey at her feet. It always manifested a certain jealousy of other animals. A pet dog was brought on a visit to the house, and the Persian evidently was annoyed at a rival near its throne, and manifested determined enmity to the dog, spitting and hissing at it. As for other cats, it would never endure them. If it saw one about the place, it flew at the intruder, and did its best to demolish it. The sudden change in its aspect when it perceived another cat was very curious. Its eyes glared, its whole countenance became fierce, and it was hard to recognise the gentle, dreamy-looking creature that had been quietly purring in the drawing room.

My mother happened to be away from home for nearly a year, and when she was gone I took charge of pussy, and he soon grew exceedingly fond of me. Being much alone, I made a great pet of him, and he became quite a companion to me, and afforded me great amusement and pleasure by his many pretty and winning ways. He would jump on my lap, put up his face to be kissed, nestle against me, stroke me with his paws, and all but say "I am very fond of you." When I would talk to him and pet him he would purr with the greatest delight, and he evidently quite understood when told that he was "a good cat, a pretty cat, a dear pussy." If he was spoken to angrily he would look ashamed and hide himself; but if he thought he was neglected, he would be offended and hurt, and required great petting to make him forget the slight. If I left the house for a day or so, he would rush to welcome me on my return, purring loudly, and he then always expected to be taken up and talked to, and I seldom omitted to take due notice of him. But one evening, returning from Dublin after a long drive, I perceived on entering my room a parcel of letters on my table, and being anxious to open and read them I forgot to take up pussy, who had come forward, purring to welcome me. Suddenly I perceived him endeavouring to open the door of a wardrobe which was not quite closed, and watching him, I saw him succeed in getting the door open, and he then got into the wardrobe, and would not come out when I called him. I went and lifted him out and spoke to him, but it was too late; his feelings were hurt at not having been noticed at once, and he would not respond to my caresses. He maintained an air of cold dignity, and the moment I put him down he got again into the wardrobe, and there he stayed all night instead of sleeping on my bed, as he usually did. In the morning he mewed to be let out, and walked out of the room, still with a hurt and stately air. He recovered however the same day, and was soon as affectionate as ever. Some time afterwards I left home for a couple of months, and on my return I was told that the Persian cat was seriously ill and could not be persuaded to take food. When the poor animal was brought to me I saw at once the change in it. It was quite emaciated and as light as a feather, and seemed sad and stupid; but it almost immediately began to recover, and before I had been back a week it was a different animal. It had been breaking its heart for want of its friends. It was accustomed to sleep on my bed, and would settle itself at my feet at night. The evening I arrived it so settled itself; but scarcely had the first dawn of light commenced in the morning when I was awaked by feeling something close to my face, and opening my eyes, I saw the Persian examining me carefully to ascertain was I really there. When I began to speak to him and pet him, his joy was unbounded; he settled himself triumphantly on my chest and purred a positive "Io pean." There is something very touching in the affection of a pet animal, and I was much gratified by the devotion of my favourite.

I used to be much amused at watching his ways. He was very observant, and took great pleasure in watching all that was going on. He would settle himself at the top of the large staircase, and with his head between the balusters would sit there for hours, observing what went on in the hall beneath. He would walk round and round a room, making an examination of the various objects, opening the doors of wardrobes and presses, and clambering on to the shelves. He was very fond of finding cozy nooks to settle in, and displayed a strong propensity to red ?annel. The colour appeared to attract him, and he never saw a red dressing gown lying about without making it his couch. Noticing this, I knitted a red woollen blanket, which used to be spread on a chair or sofa for him, and he at once understood that this blanket was his own private property, and took possession of it with a highly gratified air. He used to look a real picture as he lay purring on the blanket, the scarlet colour forming a fine background to the rich tawny and black of his fur. He might have adorned some oriental sultana’s boudoir. '

The great pleasure and amusement which this beautiful creature has given to our household has made the Persian puss quite a proverb with us and I sincerely hope that the nine lives which are said to be a cat’s by right may endure beyond the ordinary length of feline existence. The animal is now about six years old, and except its decaying teeth shows no sign of age. It has led a healthy life, being much in the open air, and having had "ample room and verge enough" for exercise. We lived for some time in a country place, where the Persian had the run of the grounds in which the house stood. This freedom it fully appreciated, and was exceedingly happy, rambling about and occasionally catching a rabbit. On summer evenings it was very hard to get the cat to come indoors; it would elude pursuit, and sometimes it was called for an hour together before it would appear. On moonlight evenings especially it was very reluctant to come home, and sometimes we were obliged to give up the attempt to find it, and leave a small window open for its entrance. It was usually found in the house of a morning, and we could generally trust it to take care of itself. On moving to town, however, we had a great deal of trouble with it. It could not bear to be circumscribed in its movements, and would wander off, and once the town crier had to be employed to proclaim its loss. Fortunately it was brought back in safety, and so much is it prized, that I trust its wanderings will never lead it irrecoverably from its home. IRENE.

PERSIAN CATS

I read with much interest an article on Persian cats in ‘The Queen,’ and can testify to their wonderful sagacity and affection, having bred them for ten years. Many anecdotes could be related which would interest lovers of the feline tribe; but, not to make too long a story, I will give you some instances of affection shown by my present favourite, a fine tortoiseshell, with long silky hair and bushy tail like a fox’s brush. I had her from kittenhood, and in a short time she attached herself to me with such unusual devotion as is seldom evinced by the ordinary common cat, and is peculiar, I am inclined to think, to this breed. She follows me every moment of the day up and down stairs, walking with me in the garden, and will not leave me even in the most inclement weather when I am gardening, though her inclinations would lead her to the warm rug. She has attempted to follow me when I have been going beyond the house in the street, and I have had to turn back some 400 yards to escort her home safely; and on my return from a walk I generally find her patiently waiting for me, and she will run along our own wall and our neighbour’s to meet me. One of her many accomplishments is to play at hide and seek by the half-hour and more. I hide behind a door, pussy comes cautiously to look for me, and the moment she catches a sight of me off she scampers with her tail erect, giving a cry of satisfaction, and hides behind another door, then up the stairs to peep over the balusters, and so on, much to my own and other people’s amusement. For some time she slept on my bed, nestled at my feet, and in the small hours of the morning I used to awake, feeling a very curious tickling over my face like spiders crawling. This was pussy feeling me with her whiskers in the darkness, not rubbing her nose up to me as she would in the daylight.

She is very wise in her little ways, and contrived cleverly to have her first family reared in the baby’s berceaunette. Another of her families I discovered in a drawer of my wardrobe after a few hours’ absence from home. But now that she has a room for her many families, if we dare leave the door ajar a moment, up she drags her four and five kittens to a snug corner of the sitting room, or a shelf in my wardrobe, or behind the piano, off the top of which she jumps to stow away a kitty out of reach. But what most astonishes us is her unselfishness; for she will carry up tit bits to her companion pussy from her room - not such scraps as she has no wish for, but, after offering the morsel to him, should he seem indifferent to it she will eat it up with great gusto. Once she had an unusual delicacy, part of a stewed pigeon, which she carried into the room where I was sitting, and placed it upon my dress; and when I took it to make-believe eat it, she jumped upon the table by me, rubbed up to me in the greatest delight as if she were asking me if I did not enjoy it very much; then when I put it down she made short work of it, plainly showing us it was no want of appetite that induced her to offer it to me. She will allow her master and mistress to handle her as they please; but if one of the younger members of the family ventures to take the liberty of putting her in an uncomfortable position - to turn her on her back with her paws in the air, for instance - she resents the insult by playfully biting, and then licking the spot to atone for her seeming unkindness, As pussy is now six years old, and has had so many families to rear (these families having caused her great anxiety), she is getting somewhat passee; but many of her children inherit their mother’s beauty, and even surpass her. F. C.

PERSIAN CATS.

I have been much interested in reading "Irene’s" letter last week about her Persian cat, who must be a great beauty. Is it known that most Persian cats are great hunters after birds of all kinds, rabbits, &c.? One Persian kitten I gave away used to bring me two or three rabbits a day, and at last, as he took to catching young pheasants, my friends had to get rid of him. I have three Persians, the white one I wrote about two weeks since, as having blue eyes and perfect hearing. One cat, a yellow Tom, I have had weighed this morning; he weighs 10ilb.; he is immense, and has fur 3 inches to 4 inches Iong. - FELIS.

During the last fifty out of my nearly seventy years I have given especial attention to the subject of white Persian cats, and have come to the conclusion that though all kinds of white cats, whether Persian or other, are not deaf, whether having a pair of blue or other coloured eyes, a white cat whose two eyes are not a pair in colour is always deaf. A lady to whom I related F. Dawson’s remarks at once told me where to find a cat and kitten both milk-white; the old lady, owning a pair of eyes, has perfect hearing; the kitten, with two not a pair, is deaf as a post." - C.A. W.

[We had recently in our possession a cat with one blue eye that had a perfect sense of hearing. - ED.]

THE DOMESTIC CAT. THE TORTOISESHELL VARIETIES.

The singular though well-known coloration of the domestic cat termed tortoiseshell is a variation derived from some of the numerous ancestors of the Felis domesticus. The coloration of the wild felines is very erratic, varying from the nearly uniform tint of the lion and puma to the banded stripes of the tiger, the spots of the leopard, the black of some varieties of the panther, the uncertain markings of the clouded tiger, &c. Nearly the whole of these variations may be observed in our domestic cats, but the spots of the leopard have not yet been obtained. There is no doubt but that if cats were as carefully reared as most other domesticated animals, this and other singular and new varieties would reward the care of their owners. The tortoiseshell, consisting of black and yellow, is a colour analogous to, but not exactly identical with, the markings of the clouded tiger; in our present example, these colours are combined with white.

At the Crystal Palace Cat Show, classes for tortoiseshell and white cats of both sexes are established, and are all always well filled with very beautiful specimens. Our engraving on page 7 represents one of the prize animals at the last show. In this variety the colours contrast together very satisfactorily, and we know of no cat which is more pleasing in effect than a well-marked tortoiseshell and white. No rule can be laid down as to the distribution of colour; in fact, the markings are so irregular in form, size, and general distribution over the surface of the animal, that the establishment of any such regulation would be difficult. Nay, we would almost be inclined to maintain that the charm of the variety, like that of a piece of majolica ware, depends in great part on the very eccentricity of the arrangement pattern, combined with brightness and distinctness of colours.

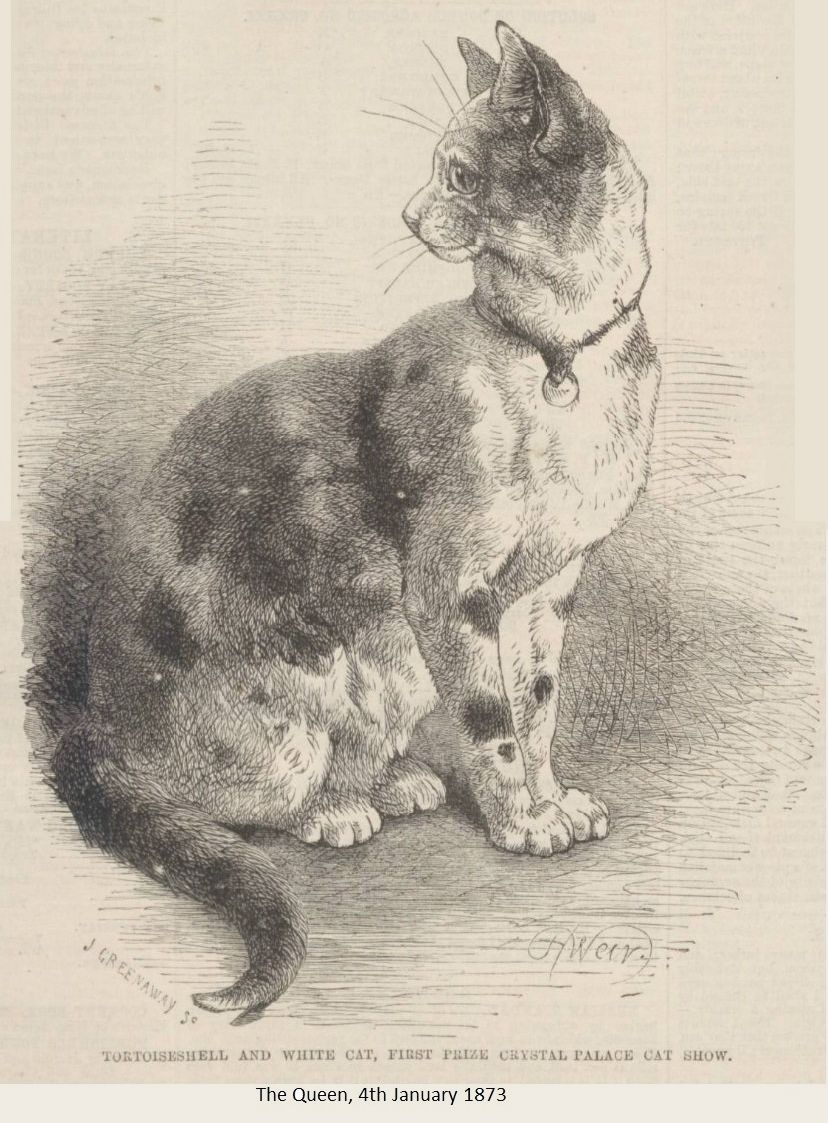

VARIETIES OF DOMESTIC CAT. THE SMYRNA CAT

Our Illustration represents a very well-marked variety of the domestic cat, imported from the East under the title of the Smyrna cat. The coloration of this specimen is very peculiar. The general colour of the body is like that of a wild rabbit. But the legs and chest are more rufous, and striped with black; a peculiar black stripe may be observed running backwards across the cheek from the outer angle of each eye. The markings more closely resemble those of a wild Asiatic cat known to zoologists as Felis chaus, than any other wild species; and the domesticated cats of India partake of the same characters, being like the wild Felis chaus, but smaller in size, and having a somewhat longer tail. As we have already stated, the domestic cat is not derived from any one particular wild species, but is a mixed and mongrel race. Taken to any part of the globe where small wild felines exist, it without scruple allies itself with them, and consequently in every country the domestic cat partakes of the nature, form, coloration, &c., of the wild cat of the district. Thus in India the tame cat breeds with the wild Felis chaus; with a second species known as Felis rubiginosa; with a third, F. ornata; and in Ceylon with the Felis viverrine; while in South Africa it allied itself readily with the common Caffer cat, a totally distinct animal from our domestic variety.

Nay, even the different wild cats are so closely allied, and in many cases intermingled, that naturalists are not determined as to their number, and squabble in the most unscientific manner over the distinctions between the various kinds. In fact our zoological works contain the enumeration of above 150 feline animals, at least one-third of the names being merely synonyms, or, as they would say at the Old Bailey, "aliases," given by naturalists in their anxiety to have the honour of naming a new animal.

The cat, though now known so familiarly in the East, was alike unknown to the nomadic Jews, and, still more strange, was not even mentioned by the classical authors on Greece or Rome. Writing on the subject, the Rev, Canon Tristram states: "The cat is not mentioned in either Old or New Testaments, but occurs in Baruch, where it is named among the animals that defile the idols of Babylon: ‘Upon their bodies and heads sit bats, swallows, and birds, and the cats also.’ We know both from Herodotus and from the mummies in Egyptian tombs, that the ancient Egyptians tamed and employed cats. The species was probably the same as our own (Felis domestica), and derived from the wild cat of Nubia and Abyssinia (Felis maniculata). The Jews, from their intimate connection with Egypt, must have been acquainted with the cat; but we have no indication of their having employed it, and in the passage in Baruch it seems probable that wild cats are intended. It is curious also that, excepting in connection with Egypt, we have no allusion to the cat, now as worldwide in its distribution as the dog, in any classical authors either of Greece or Rome. The tame cat is now as common in Palestine as elsewhere; and there are also more than one species of wild cat, the most common of which is the booted cat (Felis chaus). Which is rather a lynx, with short, bushy tail, black feet, and tufts of hair at the extremity of its ears. It is nearly double the size of our cat. Another wild, long-tailed species, the Syrian cat (Felis syriaca), more nearly resembles the wild cat of Europe."

The cat figured in our illustration was one of the prize animals at the last Crystal Palace Show. It is the property of Mr P.H. Jones, of Fulham.

VARIETIES OF THE DOMESTIC CAT. BLACK AND WHITE CATS.

In all races of domesticated animals no variety of colour is more frequent than black, unless, indeed, it be the absence of all colouring matter which produces white. Those who have studied the production and perpetuation of various colours in domesticated, and even in wild animals, know full well that black and white are more readily interchangeable than any other colours. For example, birds whose plumage is black are very often seen to produce white varieties called albinos. Thus white blackbirds are much more frequent than white thrushes; and black Spanish fowls not unfrequently moult into a perfectly white plumage, a change which, so far as we know, happens to no other breed of poultry. In our common domesticated cat various admixtures of black and white are exceedingly common, and in those cases in which the colours are symmetrically arranged a very pretty effect is produced. Most artists of natural scenery know the striking effect of a sheeted cow in a landscape - that is a cow that is black in the head and fore and hind quarters and limbs, but with the body white, as though a white sheet or cloth had been put over the loins or centre of the back. In a park or open pasture such a cow is most effective from a pictorial point of view; and we know of long prices having been offered, and refused, for animals having this coveted marking, and that quite irrespective of their particular breed or value as dairy animals.

To be effective and handsome, a black and white cat should have the black colour in the greatest abundance, and the white regularly disposed. In the example which has been portrayed by the facile pencil of Mr Harrison Weir, the white embraces the face, jaws, throat, and under parts, and also the fore feet markings, as regular as those of our example, are not common, and when present add greatly to the beauty and value of the specimen. From the contrast of the colours, as compared with the less striking tints of surrounding objects, black and black and white cats are much more conspicuous than their sober-coloured tabby relatives, and have hence been more frequently selected as subjects for poetical or pictorial work.

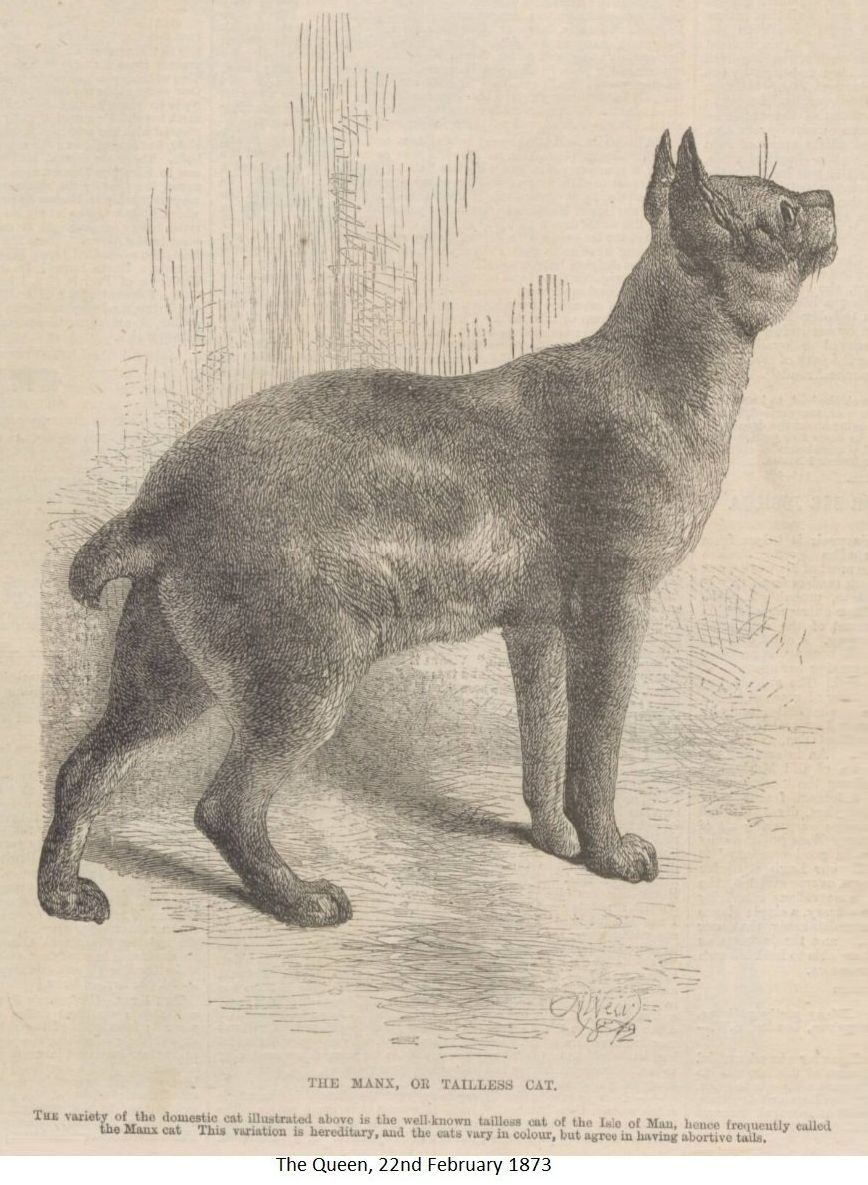

THE MANX CAT

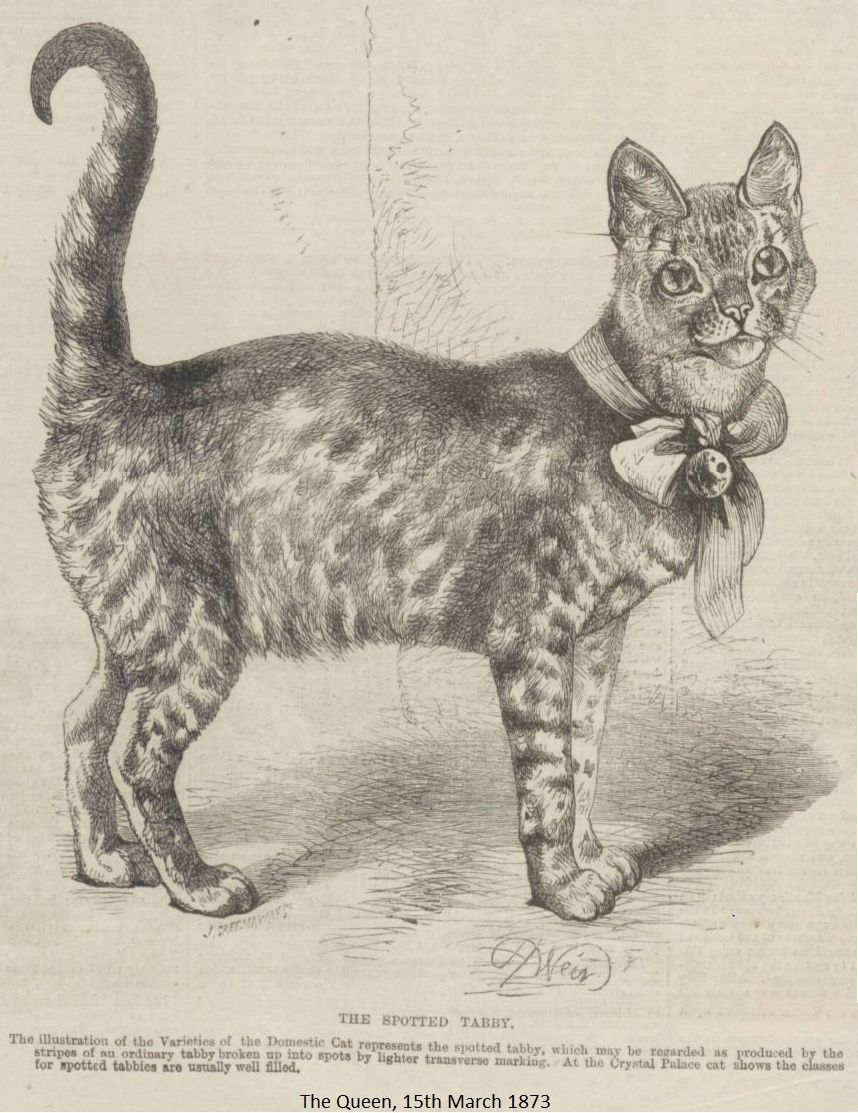

THE SPOTTED TABBY

VARIETIES OF THE DOMESTIC CAT. THE BANDED TABBIES.

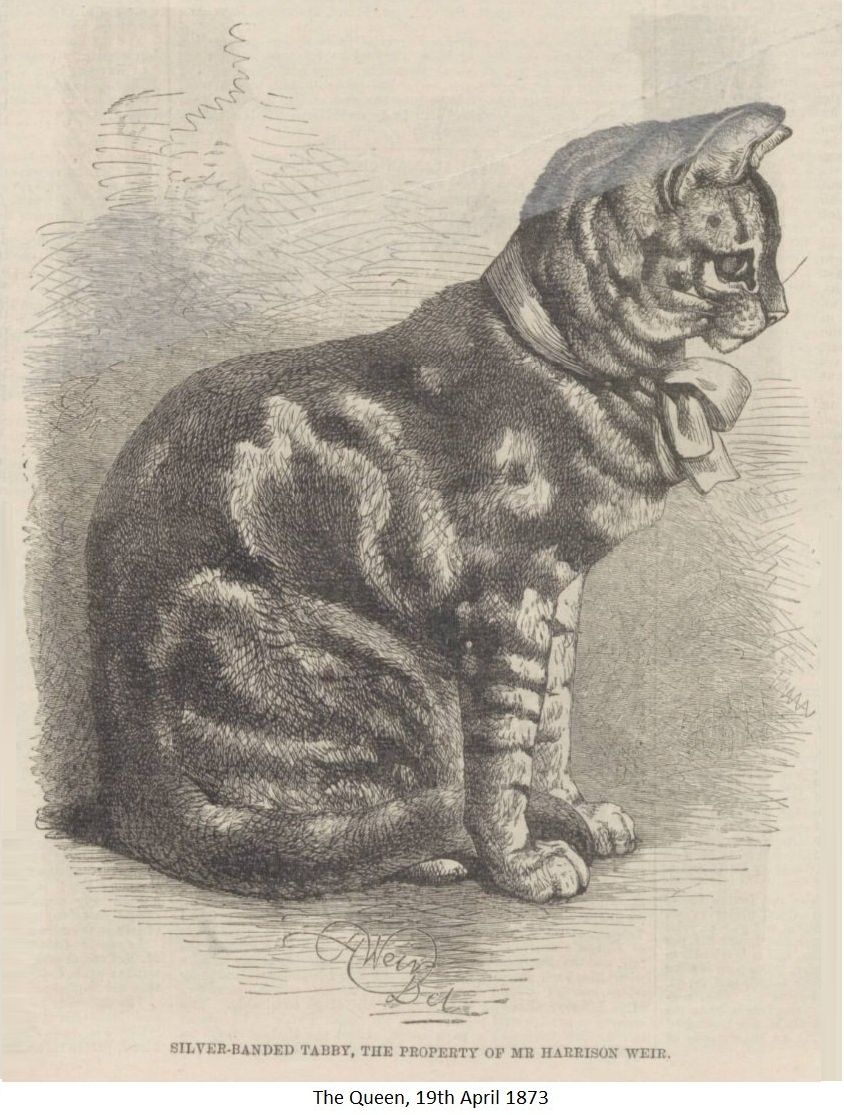

The banded or Striped are distinguished from the spotted tabbies by the dark markings not being broken up or divided transversely. Regarded as fancy or show animals, the properties of the banded tabbies are the breadth, regularity, and depth of colour of the markings. In a brown tabby there should be black on a brown ground of as rich a colour as possible; in a silver tabby black on a very light blue-grey fur; in a red tabby the stripes should be deep red on bright deep yellow ground. The engraving represents a silver tabby, 14 years old, "The Old Lady," the property of Mr Harrison Weir. She has been exhibited several times, and been very much admired; and when younger, was of first rate colour and markings. Yet, old as she is, she has not as yet been beaten in her class. Being the property of the judge, she has not been shown for competition at the recent Crystal Palace shows.

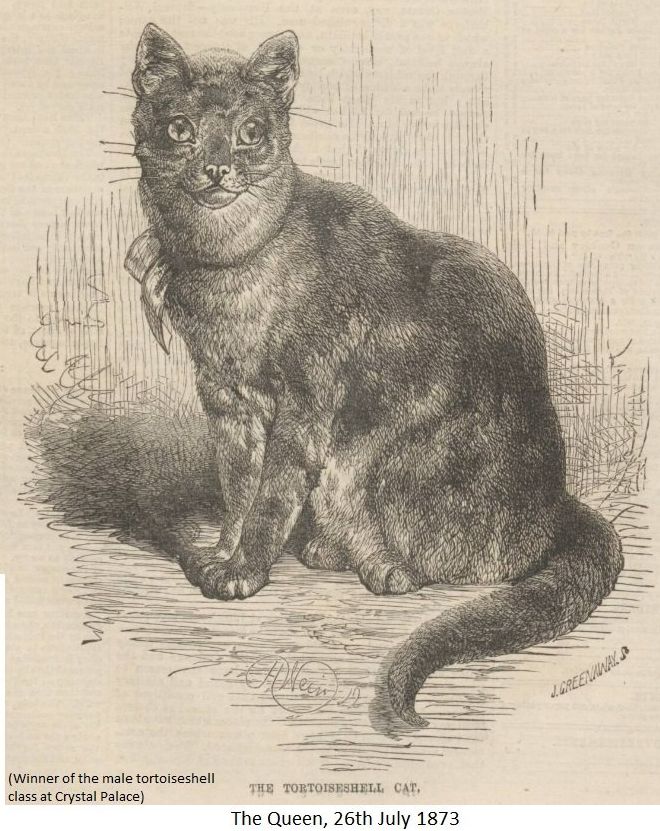

THE TORTOISESHELL CAT

If Cat Shows have had no other beneficial effect, they have at least destroyed one vulgar error, which, although it escaped the denunciation of the learned Thomas Browne, who makes no mention whatever of cats in his "Pseudodoxia Epidemica, or Enquiries into Vulgar and Common Errors," nevertheless was generally received by the British public – we mean the belief in the non-existence of the tortoiseshell tom cat. It is quite true that male cats of this colour are extremely rare, but of the fact that they do exist our illustration may be taken as a proof, inasmuch as it represents a tortoiseshell tom cat that carried off the prize for that variety of colour at the last Crystal Palace Show held in October last, being the sole claimant for the honour, whereas nine tortoiseshell females competed for the prizes in the class especially devoted to them. The same disparity of numbers holds good in the classes for tortoiseshell and white, in which three males and fifteen females were respectively entered.

Setting aside the rarity of true tortoiseshell, we hardly think that the arrangements of colour are as effective as in the tortoiseshell and white. In the latter the colours red, yellow and black are distributed in large masses, and are very bright and distinct, whereas when no white is present, they are, in most of the specimens, mixed up and clouded so as to lose the striking effect produced by their being more distinctly arranged.

At present the cat shows have, as far as we are aware, only succeeded in calling into light one specimen of a true tortoiseshell male, belonging to Mr M.L. Smith. Whether the succeeding shows will elicit a greater number remains to be proved; but as three prizes are offered by the liberality of the Crystal Palace directors, we should hop to see more specimens put in an appearance.

In fact, there is no reason why they should not be more abundant, as the tortoiseshell is obviously the variety that is analogous in its markings to the clouded tiger, and might be increased infinitely by careful selection and management. The relative scarcity of the males and females in the true tortoiseshell is singularly enough reversed in the case of red tabbies. In this peculiar coloration males are abundant, but females are comparatively scarce. What would result from the alliance between this aristocratic feline families has not yet been determined by experiment.

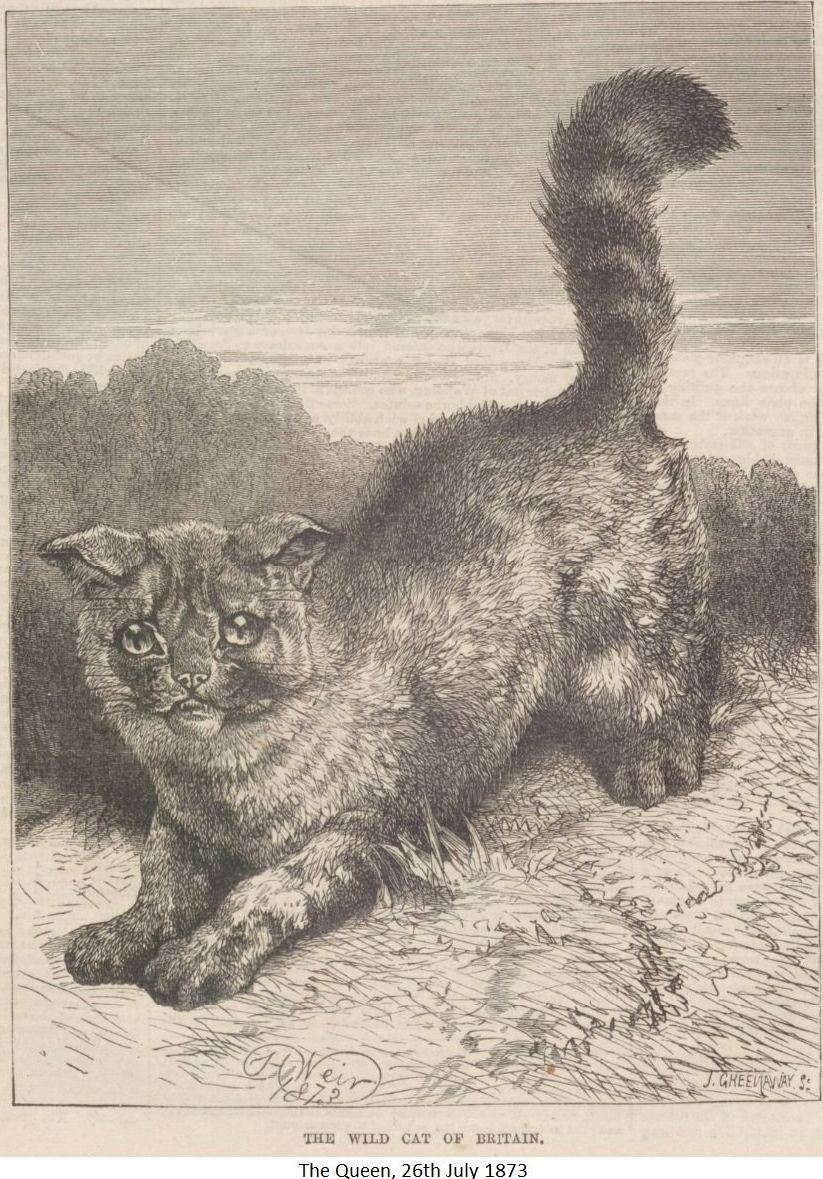

THE WILD CAT OF BRITAIN

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS ON CAT OWNERSHIP