CATS AND CAT CARE - A RETROSPECTIVE: THE EARLY 1900s - FEEDING, HEALTH AND GENERAL CARE (PAGE 2)

This article is part of a series looking about cats and cat care in Britain from the late 1800s through to the 1970s. It has grown since originally written in 1996 (web version 1999) and was split into separate web documents in 2003 (to speed loading time) with some overlap between the parts. Each part is split into topics and the contents of each topics are ordered chronologically as far as possible with added "then and now" commentary. In this way I hope to keep it an ongoing work! It is interesting to note how attitudes have changed, as well as how our knowledge has increased.

INTRODUCTION

Although there is inevitable overlap in the series of retrospective articles, this article is primarily concerned with the period from 1900 to the end of the 1930s. There are separate articles giving brief histories of cat shows and showing and cat rescue respectively.

BRIEF HISTORY OF GENERAL HEALTH CARE

From the 1880s to the 1920s and 1930s, it was generally believed that cats were becoming weaker than their predecessors. In the early 1940s this was blamed on poor diet, inbreeding, delicate pedigree cats and kittens being given away too young. One thing which almost certainly contributed to early death was poor understanding of feline health and the use of remedies which were actually toxic to cats.

Early remedies included eating a whole kipper (including bones) to remedy constipation. To cure diarrhoea, the cat was dosed with crushed clay pipes. A regular dose of fish oil not only kept cats regular, it supposedly protected them against worms. In 1901, the only documented feline ailments were colds, pleurisy, distemper, mange, worms, fits, diarrhoea and constipation.

In 1901, "How to Keep Your Cat in Health" was written by "Two Friends of the Race" and contained such advice as "If your cat should be taken ill, have as little as possible to do with drugs, unless it be in the homeopathic form". Cats with colds could be given a tonic of tincture of arsenicum in a spoonful of milk. The same treatment was advised for other ailments such as distemper, along with a mixture of eggs, cream and brandy. Tincture of arsenicum could also be given for mange. The symptoms of mange were to be treated with sulphur ointment, carbolic acid ointment, green iodide of mercury ointment and acid sulphurous lotion. Arsenic was used as both a tonic and an antiseptic. Prussic acid was used as an anti-spasmodic and also for pain relief. Lead was used as an astringent and also a sedative. All are poisonous as is mercury and carbolic. Little wonder that cats life-spans were shorter than those of their ancestors.

Pedigree cats were believed prone to dyspepsia (indigestion). "Two Friends of the Race" wrote "[Dyspepsia] is more often met with in highly-bred and notably show specimens, when a too-fixed and stimulating system of feeding is adopted". At the time, pedigree cats were not usually fed horse meat (fed to household cats) but lean chopped mutton.

To set a broken bone, a papier mache cast was made. Brown paper was soaked in boiling water, the excess water was squeezed out and the papier mache was moulded onto the broken limb. Strips of calico fabric or linen were laid over this to hold the cast in place. Fractures could also be splinted using wood, pasteboard or leather. Bandages soaked in gum, starch or plaster of paris might also be used. Warm pitch was used to prevent the splint from slipping. Quite complicated fractures could be treated and many cats made an excellent recovery though a few complicated or infected cases required amputation. This treatment (immobilisation using a cast) is familiar, even if the materials are not.

In the days of hearth fires, burns were common due to embers spitting from the fire. Large cinders could ignite the cat's fur and cause deep burns and great panic: "A cat aflame is a dangerous creature, for it may rush to any part of the house, and set fire to other materials. This disaster is treated by the application of equal parts of linseed oil and lime water, covered over with cotton wool... poulticed and warm emollient fomentations may be required." If a large amount of skin was lost to a burn or scald, the damaged area could be removed entirely and the skin drawn together: "When... a considerable blemish follows the healing process. that portion of the skin creating the eyesore... may by careful surgery be removed, and the union of the edges of the surrounding skin so neatly affected as to disguise the fact that puss is so much integument short."

The most serious feline disease was distemper. Some of the early descriptions make it hard to determine whether this was cat flu (calicivirus etc) or feline infectious enteritis (panleucopaenia). It is often identified as enteritis however, descriptions of distemper from the 1940s and 1950s suggest cat flu, especially as the authors describe enteritis separately. It was believed to be caused by high temperatures or drought and that outbreaks diminished in cooler weather. Cats with symptoms of distemper were treated with a mixture of castor oil and liquid paraffin which supposedly cleared bile. The owner was instructed to dose the cat every three hours with a dessertspoon of egg white mixed with ten drops of brandy to settle the stomach.

In 1893, an anonymous author calling himself "A Veterinary Surgeon" produced a book called "The Diseases of Dogs and Cats" in which he blamed longhaired cats of spreading distemper (they were considered weak and carriers of various diseases). He wrote, "To develop coat, colour or other points, unsuitable animals are mated... [diseases] are frequently traceable to cousin or even closer marriages. Cats did not formerly suffer from distemper when wild in back gardens the noble tabby ran, but since the long-haired varieties have been largely bred, and the meanest-looking cat may give birth to a long-haired kitten through some casual acquaintance, distemper has become quite common, and many lovely kittens succumb to it despite the most careful nursing and attention. A good old English Tabby is so hardy an animal as to have acquired for his tribe the reputation of having nine lives. Anyone who has visited a cat show with his eyes open must have seen how many weak and diseased animals are shown, only to go home and die in a few days. The Manx cat really can be classed as a monstrosity, having been developed probably by inbreeding or some freak of nature in the form of a cat which inhabited the Island of Man at an early period."" In fact distemper has apparently been with us since the 15th Century, with major outbreaks in Britain and Europe in 1796 and another in the USA in 1803.

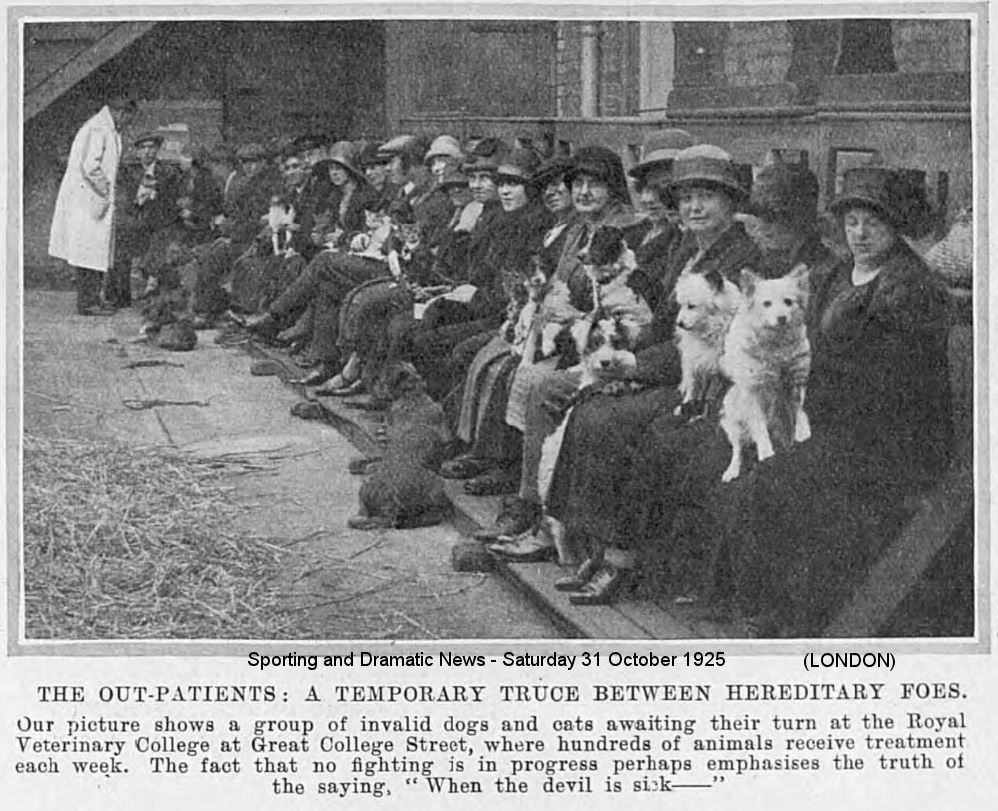

"Show fever" was an ailment of cats which had returned from cat shows in the early part of the 20th century and was sometimes blamed on a jealous competitor poisoning cats. Many cats were packed off to shows unaccompanied in baskets, or even in sacks (some cats were lost or escaped in transit) and would very likely come into contact with cats carrying distemper or enteritis. If the show cat made it home safely, it might bring these then deadly diseases back with it. Up until the 1930s, cats were believed to carry the deadly diphtheria; a cat with a sore throat was often euthanized.

In 1900, diarrhoea was treated by dissolving I oz of fresh mutton suet in a quarter pint of warm milk. A teaspoon of the mixture was given every two hours. For the braver owner, feline constipation could be treated with an enema of water and glycerine. The other cure for constipation through the ages was a tablespoon of olive oil. Olive oil and cod liver oil (or halibut oil) were cure-alls and preventatives for many years and are still given as supplements today. A suitable treatment for an out-of-condition cat was a mixture of olive oil, milk, cream and salad oil beaten together. Alternatively the cat could be given oil from a can of sardines. A pregnant cat was given a teaspoon of olive oil at least twice a week for the last three weeks. If cod liver oil was not to be had, fried bacon and bacon fat could be given instead.

Cats were believed to become off-colour in the spring, losing their appetites, developing foul breath and unkempt coats. A daily dose of cascara tablets (a laxative) would prevent the symptoms from worsening. Failure to treat these symptoms would result in constipation, diarrhoea, runny eyes, running nose and suppurating ears! If untreated, the cat would die from nervous exhaustion, heart failure, enteritis, pneumonia or pleurisy. In all likelihood, the cats were going through a combination of spring moult, hair balls hormonal changes and were picking up external parasites such as fleas and mites. Tomcats were believed particularly prone to summertime skin troubles which could be remedied by a twice weekly dose of olive oil. Female cat sometimes developed skin problems after having kittens (probably hormonal) and this was blamed on her mating with an out-of-condition tomcat! For very many years, an epithet for an ill-kempt person was "mangy tomcat".

It is likely that increased fighting and mating in spring and summer led to cross-infection and spread of parasites between cat. An early treatment for external parasites such as lice, was treated by combing the cat with a mixture of vinegar and water. A lotion could be made of one part sulphur mixed with ten parts train oil and applied all over the fur. Alternatively, a wash of equal quantities of hydrogen peroxide and water could be used (but would bleach the fur).

Fleas were associated with dirty households. To flea powder a cat, the powder was tipped into a drawstring bag and the cat placed in the bag with only its head sticking out. It stayed this way for 15 or 20 minutes, with the powder being patted onto it. Flea powders included flowers of sulphur, powdered tobacco or Persian insect powder. If Persian insect powder was used, the cat was placed on a sheet of newspaper, the powder sprinkled over it and then brushed out. The paper - and the temporarily stunned fleas - must immediately be burned.

Early wormers were toxic to cats and would have killed a good many. In the mid to late 1800s, cats with worms were dosed with turpentine. Turpentine also causes the urine to develop a floral smell. However, it also caused cystitis (inflamed bladder) and no doubt kidney damage. The cystitis could be treated with hot hip baths, linseed poultices between the cat's thighs, warm gruel enemas and opiates. It was far safer to prevent worms in the first place and in the early 1900s, a pinch of salt with every meal was supposed to prevent worms. In 1901, regular doses of cod liver oil were considered an excellent antidote to worms. Although safer treatments were available in the 1950s, it was still considered unwise to worm cats as the it would cause more trouble than good!

Obese cats might suffer from apoplexy which could be treated by applying leeches to areas from which fur had been clipped or shaved. Dropsy (accumulation of fluid) could be treated by "tapping" i.e. removing the fluid, bandaging the affected area and then dosing the cat with brandy in warm milk as a stimulant. Little was known of dental or oral problems. Mouth or tongue ulcers indicated "internal derangement" and were treated with Milk of Magnesia.

Cats in the early 20th century were apparently prone to fits, in which case smelling salts were waved under their noses. Fits were believed due to a variety of causes such as eating raw meat, or a female cat having all her kittens taken away (i.e. destroyed) at once. Female cats would supposedly never have fits if they had at least one litter of kittens. Other early treatments for fits were a warm bath and an enema (in the case of female cats whose kittens were removed), or slitting the cat's ears and expelling a few drops of blood. A good many fits were probably caused by the many toxic medications then given to cats.

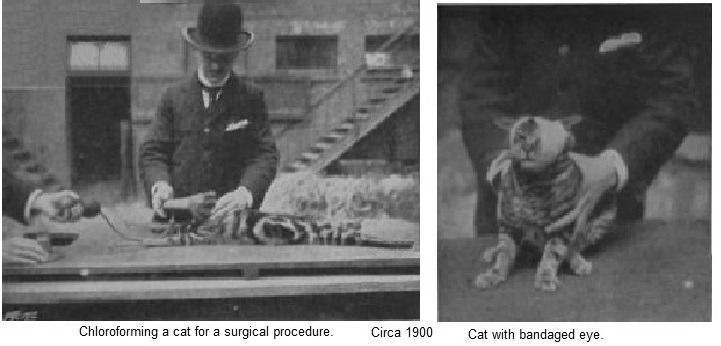

In 1901, J Woodroffe Hill, FRCVS, brought out "The Diseases of the Cat" illustrated with photos of cats being treated. He described ailments in great detail; with none of the investigative methods we now take for granted, diagnosis was based entirely on observation. Equally, none of the familiar modern drugs were then available and the treatments described now seem primitive and hit-or-miss.

Before the advent of vaccination, "Nasal Catarrh" or "Cold in the Head" was common. "The cat becomes languid, is less inclined to play or hunt, and may show a varying degree of inappetance. A thin mucous discharge issues from the nostrils, which the cat endeavours the quicker to expel by constant sneezing. There is also a watery discharge from the eyes, a warm, dry nose, and usually attended with a normal or slightly elevated temperature." The disease (upper respiratory tract infection) was variously considered to be due to damp, cold or contagion or to a sedentary or confined life.

Suggested treatment for mild cases included keeping the cat warm and treating it with camphor water and spirits of ether nitrate. More severe cases required steaming of the cat's head with an infusion of poppy heads or 2% Jeyes fluid. "For the purpose of administering vapours, it is suggested that it may be expedient to place the cat on an old chair with perforated seat, beneath which is placed the steam kettle, the whole being surrounded by a rug." Eucalyptus oil was used as an antiseptic, but was to be applied to the cat's forehead, because if it was dropped into his bed, he would probably refuse to sleep in it. Some early vets recommended a liberal, stimulating diet, but others advised a diet of warm milk.

Far more severe was Feline Distemper: frequent shivering fits, with sneezing, coughing, retching and vomiting, watery discharge from the eyes and nose, laboured breathing and snuffles. It might be followed by any of the diseases of the respiratory system. Treatment was the same as for nasal catarrh, with the addition of twenty or thirty drops of whisky or brandy. Distemper was known to be very contagious, so isolation of infected cats was advised. There were crude canine distemper vaccines available (these being as dangerous as the disease itself!) and one early vet suggested that his inoculation system for dogs should also be used for cats.

A disease recognisable as Feline Infectious Enteritis was described: "A special form of inflammation of the stomach and bowel combined frequently attacks cats, and has lately been somewhat prevalent, assuming the appearance of an epidemic and being undoubtedly infectious... Symptoms in many respects simulate typhoid. The disease is accompanied with great prostration, offensive diarrhoea, often of a dirty green colour, or resembling pea soup. There is increased pulse, injection of the mucus membranes, furred tongue - especially dark at the edges - high temperature, abdominal enlargement and tenderness, disinclination to move and in advanced cases the animal lies stretched out on the side. In some cases there is frequent vomiting and intense thirst. Before death the animal may become comatose or delirious."

Treatment consisted of ½ grain of napthol in salad, hot fomentations or poultices to the abdomen, doses of sulphate of copper and opium (then easily available), starch enemas, fluid, mucilaginous food and iced milk. Strict cleanliness and disinfection was to be rigidly observed. Should the cat survive, it could expect to convalesce on "a diet of Eastons syrup and cod-liver-oil, with the yolk of an egg and cream beaten up, and by degrees a little shredded or scraped raw meat can be introduced; but the greatest caution should be exercised in giving solid food, as the gastric and intestinal membrane remains in an extremely sensitive condition for a considerable period."

Early anaesthetics were unsophisticated and risky, being either chloroform or chloral hydrate, and were therefore largely reserved for euthanasia. Feline surgery was mostly restricted to neutering (spaying was available, although not common), repairing wounds and fractures and alleviating obstructions of the bowel.

Obstructions of the gullet, stomach or intestine were apparently common. Cats frequently seemed to swallow needles, buttons, bones, hairballs etc and dire consequences were predicted. Treatment involved a probang (a sponge tied onto a cleft stick, flexible cane or piece of whalebone) being used to force the obstruction down into the stomach, with the cat restrained, but not anaesthetised. If the gullet was damaged (either by the original obstruction or, more likely, by the treatment) the animal was to be starved for a week or two and given nutritious enemas. If the obstruction was in the stomach or intestines, a dietary lubricant such as coarse oatmeal and sardine oil was administered to help it pass through. Some books of the period mentioned the possibility of surgery and the considerable danger of peritonitis (antiseptics were poor and antibiotics non-existent) though surgery should only be risked by an expert abdominal surgeon.

The following were common home treatments for ailments most often diagnosed by the owner rather than by a vet:

The giving of medication was a vexatious matter and owners were advised to use persuasion and subterfuge rather than force. Sometimes force or restraint were necessary and in the absence of sedatives, this meant physical restraint: "Take the cat by the loose skin of the neck with one hand and by the skin of the pelvis with the other and place it on a table pressing down until the breast-bone in front and under surface of the pelvis behind are held firmly against the table." A cat might be restrained for a longer period by wrapping it in a sack of cloth, leather or indiarubber or in a towel or piece of sheet.

First aid for cats in wartime included ointment for gas burns – 2 parts bleach powder and one part petroleum jelly (Vaseline). Sedatives were recommended for cats during air raids, but these were not without their problems. Bromide caused depression if used frequently. Luminal and chloretone had to be given as tablets. Aspirin was used as a sedative and no doubt many cats died as a result.

AT THE HOSPITAL FOR THE AFFLICTED DOGS [AND CATS] OF THE RICH.

BY HAROLD E. WOLF.

The Inter Ocean, 8th October, 1905

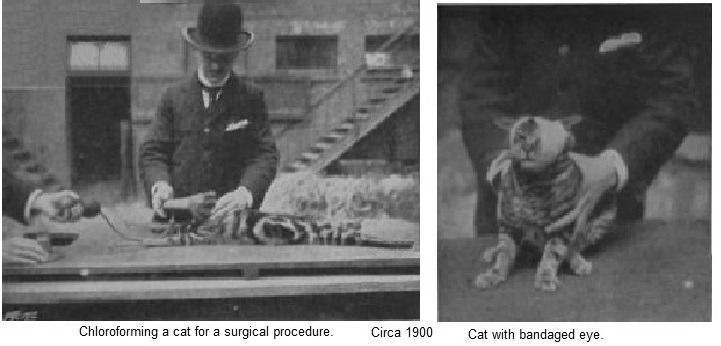

Chicago has the only dog and cat hospital in the country. Here it is that blue ribboned canine and feline aristocrats are sent by their millionaire owners to be mended by trained nurses and skilled physicians and surgeons. It was at this hospital, 78 Twenty-Sixth street, that "Granny,” a Boston terrier, owned by Herbert L Swift, the packer, had its eye taken out last Wednesday and will have a glass eye put in.

Lord Gwynne, the most famous white cat in the world, had its last tooth pulled out by Dr. White following the operation on “Granny,” Wednesday. His lordship's molars have been ruined by rich food and high living. His teeth decayed and he was sent to the hospital by his mistress, Mrs. Clinton Locke, 2825 Indiana avenue. He is to have a false set of teeth. Lord Gwynne is the father of over 2,300 kittens. His lordship is one of the few white cats in the country with blue eyes. He was brought from England by Mrs. Clinton Locke ten years ago and added to her household of cats, which is the best known and most valuable in the city. He gathered all the blue ribbons in sight. Lord Gwynne has won thirty first prizes for beauty, but is through with competition now. However, he always exhibits himself at the cat shows and looks with scorn on the young bloods who aspire to the position which he has held in polite feline society.

Lord Gwynne was not put under the influence of chloroform to have his teeth pulled. He submitted to the operation without a whimper, and it was even unnecessary to tie him down to the operating table, as it is with most of the patients [note: the tooth must have been extremely rotten]. When Lord Gwynne returned to the cat ward, toothless, from the “meowing” set up by his four white coated mates it was evident they knew what bad occurred to their liege lord. The four cats are Babette from Marion, Wis.; Lassie, from Ypsilanti, Mich., owned by Miss Alice Barnes of that city; Wendella, and Senior.

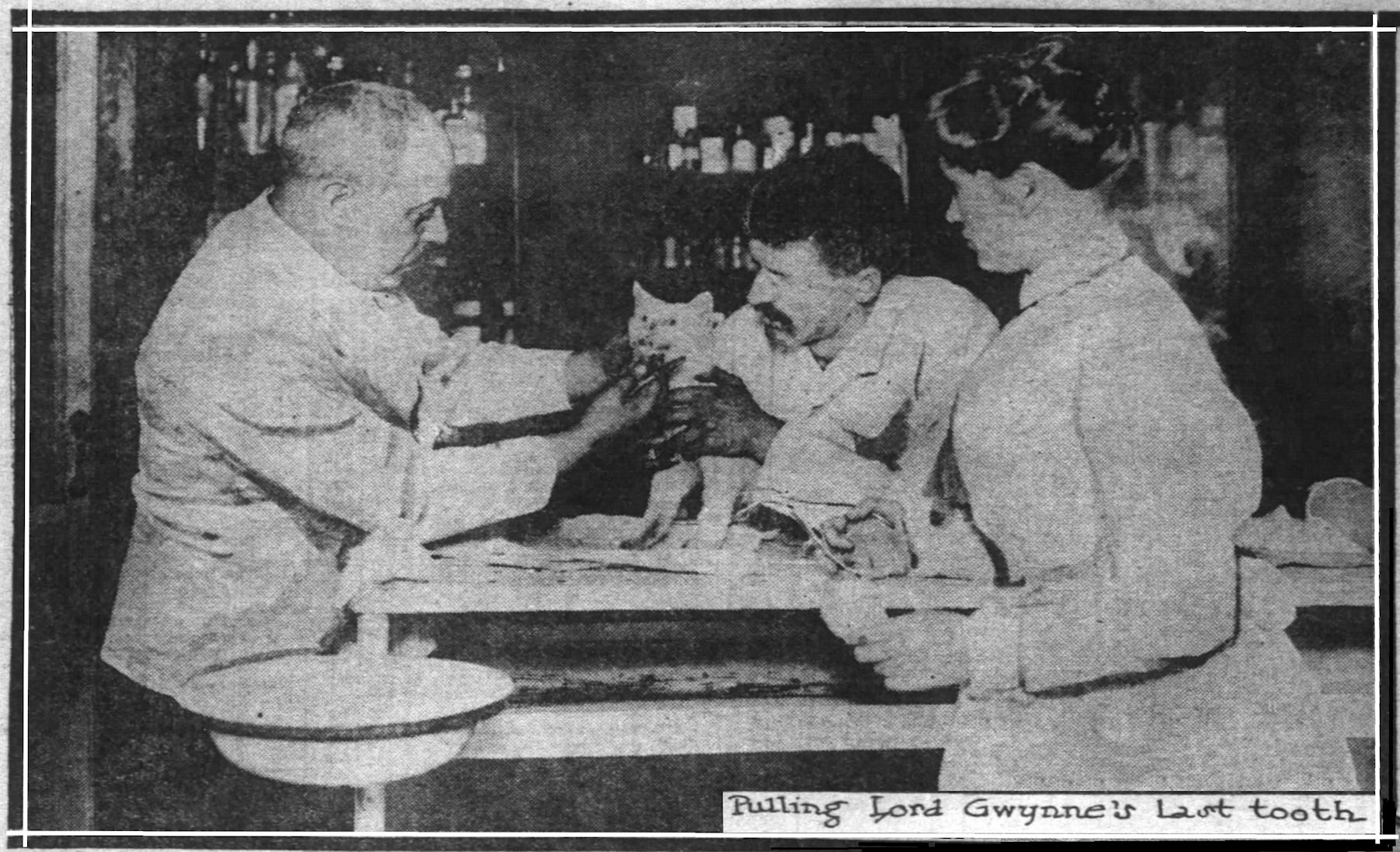

The patients at the cat and dog hospital are cared for the same as patients at an institution for the treatment of human ills. Some animals are on "soft” diet and some on "full” diet. The principal dog foods consist of cooked and raw beef, fish, dog crackers, boiled bread, and bread with meat gravies. The cats eat sardines, salmon, raw meats, and predigested foods. At 6 o'clock in the morning the attendants at the hospital give the animals fresh water and their medicines. The wards are swept and disinfected. Especial care is taken in the contagious ward, which is on the main floor and as far removed as possible from the rooms where the noncontagious diseases are treated.

From 10 o'clock until noon the operations are performed. Dr. White makes about twenty major operations a week and half a dozen minor operations in a day. In the afternoon he visits his "patients” at their homes. Like some persons, there are dogs and cats who have an aversion for hospitals — at least their mistresses (generally they are mistresses) — have this aversion.

Fifty per cent of the animals, he said, are brought to the hospital because they have been overfed with rich foods. Almost daily dogs and cats which have been injured by automobiles are hurried to the operating room in the ambulance. In tfie picture is shown Thora D., a Great Dane dog, being removed from the ambulance by Dr. Stevens. Thora D. was run down by an automobile at Twenty-Ninth street and Michigan avenue on Wednesday. [. . .] The automobilist who ran down the dog pulled his speed lever and was soon lost to sight.

The great society event of the year in exclusive canine circles, of course, is the dog show. The swells of catdom look forward all the year to the cat show. The cat show takes place the end of December. Long before that time all good looking felines are preparing for the event. The cat and dog hospital is turned into a beauty parlor, where the blue ribbon aspirants are trimmed and primped and pulled Into shapeliness.

Dr. White is the only veterinary in the country, and perhaps in the world, who devotes his time exclusively to the treatment of dogs and cats. He said that pure love of these animals drew him to the work. It pained him to see household pets killed instead of cured. Since his creation of a new field in his profession, the Chicago Veterinary college has established a department of canine and feline pathology. Dr. White is the Instructor in this department.

FELINE HEALTH CARE IN THE 1930s

The following is largely drawn from a American sources published 1938.

[You can] re-word the old saying to read "Lack of care killed a cat," and you have a reasonably accurate explanation for most cat ailments. The larger part of cat illnesses can be avoided by proper care and diet. In a sense, there is no need for your cat to be ill unless an accident occurs, or the cat gets a chill, or visits the wrong playmates, or you bring home the germs of some cat disease on your clothes. Yes, barring accidental sources of infection, your cat will live a long, healthy, and pleasant life if you care for it properly and feed it correctly.

Ailing cats differ from ailing dogs. Cats do not contract infection so often, but when a cat becomes ill the nursing problem is more difficult, because the cat has an active distaste for medicine, and usually misunderstands your intentions when you attempt treatments. Sick cats do not like to be handled, and usually prefer to go into a corner and mope. Cats are very sensitive to a change of scenery during illness, and a cat has a better chance of recovery if kept at home in familiar surroundings. This fact must not stop you from taking your pet to a cat hospital immediately if its ailment is serious, or if it has been gravely injured.

Cats have ailments similar to those from which people suffer, such as diseases of the throat, lungs, stomach, and liver. But in general, most cat illnesses yield to simple medication and diet. The cat is careful to avoid disease. It eats carefully and shuns getting wet. Danger signals of approaching illness in a cat are: lack of enthusiasm at play, a loss of appetite, and a decreasing interest in caring for its coat. Loss of appetite alone may not be serious, because the cat stops eating under an emotional strain, such as moving to a new house. If a cat persists in not eating, it is probably ill:

1. Feed properly. Meat is the chief food, winter and summer. Be certain the meat is fresh.

2. Brush and comb the cat often. Daily is best.

3. Allow plenty of fresh drinking water.

4. Have green grass available at all seasons.

5. If you have played with another cat, wash your hands thoroughly before playing with your own pet.

6. See that the cat has daily elimination. Constipation should be tended to immediately.

7. Fresh air and sunshine, and exercise are necessary.

8. Be certain that your windows are screened, so the cat will not fall from a window ledge and injure itself.

COLD: This is the source of many cat illnesses. Colds are contracted from a wetting, from sleeping in a draft, from a sudden winter exposure to which the cat is not conditioned, etc. Through the doorways of the nose and throat the cold germs enter, and while they may not be serious themselves, they may result in pneumonia, bronchitis, and other pulmonary diseases, or even distemper. No cat cold should be taken lightly. Treat your pet immediately, and continue until it is fully recovered.

SYMPTOMS; Sneezing, a warm dry nose, occasionally a discharge from the nose, watering of the eyes, lethargy, lack of interest in food. If the attack is mild, the cat may not have a loss of appetite.

TREATMENT: If you have other cats, isolate the one with the cold immediately. Keep the ailing cat in a warm room, and make its bed comfortable with a hot water bottle, or an electric pad (low heat). Give it half an aspirin once a day (no more than three doses). Vapour inhalations several times a day help (see note following). Vaseline will help relieve any soreness around the nostrils, and will make any discharge of mucus easier. Reduce the amount of food somewhat. If the cat will not eat meat, try searing a piece of beef, then cut the meat into strips and press out the juice with a potato masher. Cats will usually take this nourishment even when very ill. If there are evidences of constipation, a teaspoonful of mineral oil should be given twice the first day, and once the following day. Continue to treat the cat for a week after the last sign of cold is gone.

Cats in general do not approve of medical treatment. It is wise to train your cat in kitten-hood to be handled, to take liquid from a spoon, and to allow its mouth to be opened while you insert a small particle of food. Later this trained cat will take medicine without trouble, and will allow you to open its mouth and administer a pill.

Giving medicine to sick, untrained, grown cats is usually a strong-arm operation. To give liquid medicine or tablets, first wrap the cat's legs, body, and neck securely in a heavy towel. If you are working alone, it is best to pin the towel with safety pins. With your left hand on top of the jaw, grasp the thumb and forefinger back at the rear of the cat's mouth. Put pressure on the cat's cheeks, pushing them inward against the teeth. This has a double purpose: it causes the cat to open up, and it keeps you from getting nipped. If your pet has confidence in you, you can put the tablet far back in its mouth by hand-otherwise, it is safest to give the tablet with a spoon. There is a fair chance that you will not have difficulty in giving the cat liquid medicine. Some cats will lap the liquid readily.

Some medicines may be mixed in a cat's food. Bismuth mixes well with meat, mineral oil may be combined with some tuna, etc. Since meat is often the best food in time of illness, the cat should be urged to eat it. Ball up a little meat in dabs and try hand-feeding. Liquid medicines sometimes may be fed, through a medicine-dropper. If the cat is jumpy, an orange spoon is safer, because the cat may break the dropper and be cut by splintered glass.

WARNING: There is danger of the cat contracting mechanical pneumonia if medicine goes down its windpipe. So dose with care. Do it slowly.

INHALATION TREATMENT: Inhalations are valuable in fighting colds, but you will have a hard time convincing the average cat that inhalations are necessary. Place the cat in a box of screen wire. Prop the box on chairs so that you have a clear space below. Drape the top and sides of the box with a sheet, then place a pan of boiling water and inhalant below the cage so that the rising medicated steam will be breathed by the cat for ten or fifteen minutes, whether kitty approves or not. Oil of eucalyptus, or a similar inhalant, will be satisfactory: If the cold is severe repeat the treatment several times a day. Be sure the cat is kept warm after the treatment.

These diseases sometimes follow a difficult cold. If your cat does not respond to the cold treatment in two days, you have reason to suspect other complications. A cough is a usual accompaniment of bronchial or lung trouble, and continued high fever is another sign. While nursing and treatment at home may bring your cat to recovery, a trip to the veterinarian is the safest solution. Treatment of respiratory diseases at home requires the continuation of the cold treatment. Heat must be kept up, and if the cat has pneumonia it is well to put it in a warm jacket. The jacket should cover the neck and chest completely, and may be supplemented with poultices or hot applications.

Remember, a sick cat must eat; tempt it with its favourite foods. Don't hurry convalescence. Give the cat time to recover, or you may have the nursing job to do over.

DISTEMPER: This is the cat's most dangerous germ disease. It may attack a cat in several ways, and it is possible that each separate form may be an individual type of germ infection by itself.

Distemper that attacks the air passages may be lethal not entirely because of its own effects, but because it induces severe pneumonia. Intestinal distemper strikes speedily and is usually violent enough to kill the cat without the aid of other infections. One thing is known for certain about distemper; the germ that causes it has an exceptional amount of vigour. Highly contagious, this cat-slayer is easily contracted, hard to dispose of, and harder still to eradicate from a cat's living quarters after a recovery. To keep distemper localized you must follow these sanitary precautions:

1. Place the cat's box in a warm, well-ventilated place that can be cleaned easily.

2. Make the bed from crumpled newspapers, with an overlay of blanket, or ticking. Remove and burn the papers daily-wash and sterilize the blanket daily (better have two blankets).

3. Keep all water or food pans, spoons, cups, etc., used during the cat's illness sterile by scalding.

4. Burn immediately all swabs or cotton used to remove mucus.

5. Empty, scald, and refill the cat's toilet pan several times daily. Be sure to use paper filler, because it can be put in the furnace and burned.

6. Following the illness, the cat's box should be disinfected and repainted, or burned. Thoroughly fumigate the room used by the cat. The course of the disease will probably immunize your pet, but no other cat should be allowed to come into the sickroom for at least four or five months afterward. If your cat dies from distemper, allow perhaps half a year to pass before you try to bring up another cat :n the same apartment.

If these sanitation rules sound rigorous enough for a plague, remember that distemper is a plague. Like a well-trained gangster, distemper doesn't fool around when it starts into action.

AIR PASSAGE DISTEMPER: This type is most subject to cure. At the start, this type of distemper may look very much like a common cold, so all colds should be watched. There is always fever, watery eyes, and discharge from the nose that is first thin, but later turns thick. Watch the cat's coat. Under the pall of distemper the cat neglects grooming, and the coat will form into noticeable spikes or wads of hair. There may be some diarrhea. Most cat owners will find it advisable to take the pet to a veterinarian for treatment. If kept at home and treated, aspirin may be given to adult cats-half tablet doses once a day. Warmth, isolation, and fresh air (no draughts) are part of the cure. Beef juice, egg and milk, chopped or scraped beef, or liver extract should be fed. Swab discharge from eyes and nose frequently, using a dilute solution of boric acid on the swabs. Inhalations are often beneficial.

Unless this distemper is very deep seated, recovery will take place in about four weeks. However, the cat should be kept under supervision for at least a month and a half longer. Keep it away from other cats for at least four months.

NOTE: A virulent form of distemper settles in the throat, where in time it may so ulcerate the throat tissue that recovery is next to impossible. A usual symptom is a pro fuse flow of saliva and a heavily inflamed throat. In advanced stages the cat is unable to swallow, and it is the humanitarian act to end the cat's suffering. Treatment should be left to a veterinarian. If arrested in time, this type of distemper can be beaten. Your cat stands a fourto-one chance of recovery.

ABDOMINAL DISTEMPER AND INFECTIOUS ENTERITIS: These diseases are so parallel in the way they attack a cat that many authorities believe them to be one disease. If you can imagine yourself beset with a violent case of intestinal flu, coupled with a vomiting attack, you have an idea how enteritis acts on a cat. Whether they are two diseases or not, cat mortality, without adequate treatment, is unusually high. The development of vaccines and serums for enteritis has made encouraging headway during recent years, and any competent veterinarian can give this preventive treatment. Serums are usually administered in the early stages of the disease, and even though the diagnosis is not positive it is better to let the cat have the serum shots than to make the mistake of fooling yourself with a latent case of enteritis.

SYMPTOMS: Loss of appetite, complete lack of play interest, a tendency to sleep too much. The cat vomits a yellowish liquid at frequent intervals, and the bowels produce a mucus-like discharge; sometimes blood appears in these watery stools. The cat weakens rapidly. It develops a very high fever. In severe cases, death usually occurs in 48 hours.

TREATMENT: The attack of this disease is so rapid that it is foolish to try to combat it at home. However, while preparing the cat for a visit to the doctor keep it warm, and make it as comfortable as possible. During the recovery period, remember the precautions that apply in any case of distemper-sterilize and fumigate; and keep your cat away from other cats.

WORMS: The two chief types of worms that infest cats are round worms and tape worms. But dangerous as worms are to cats, their treatment by unskilled owners is often more dangerous. The constitution of your cat will not stand the kind of worm medicine that would be good for your dog, so suggestions for treatment had better be left to your veterinarian. It is extremely dangerous to give any kind of worm medicine to young kittens, and full-grown cats too do not have much resistance against a violent vermifuge. Worms are fairly common, since the eggs come to a cat through things it eats, but there is no reason for supposing that all cats have worms and are in need of worming treatment.

SYMPTOMS: If the cat has round worms, evidences of the worms themselves may be vomited, or the eggs passed with the cat's bowel movement. A wormy kitten is usually rather obvious because of its pot-belly, while cats and kittens alike show their condition by a coat that lacks gloss and smoothness. With worms the appetite loses its governor, and the cat has a tendency to eat in fits and starts sometimes being very greedy, and the next meal not interested in food at all. The cat will usually be disinterested in play or exercise. Tape worms are less easy to detect, but a cat may pass part of a tape worm in its stool. If you suspect tape worm, take a bit of the stool on a card, place the card in an envelope and take it to the veterinarian. His microscope will decide whether medicine is needed.

TREATMENT: Keep all food and water from your cat for 24 hours before you give the worm medicine prescribed by the veterinarian. Generally, you will not have to wait long for the medicine to act. Wait for about an hour after the worms have passed before feeding your pet, then make the feeding light. Following the worming, the cat's trousers should be carefully swabbed off to prevent any worm eggs from remaining. Keep your cat under observation for at least a day after the worming.

HAIR BALL: Hair balls are apt to trouble any cat, but long-haired pets Hair have the greatest hazard from this source. As I have said balls before, in licking its pelt your pet easily picks up quite a few hairs on its tongue, which it transfers to its stomach, forming catdom's most perilous triple play. Ordinarily, a cat will not get enough hair to trouble it, and what does get to the stomach passes out in a bowel movement. A cat that has plenty of grass provides its own remedy by eating grass and then bringing up both grass and hair. There are no positive symptoms of hair balls, although this condition if left untreated leads to digestive disturbances that are positive enough. Sometimes the cat will have a series of upsets and vomit forth a light froth-or the hair ball itself. The cat with a hair ball usually has little appetite.

TREATMENT: Mineral oil or olive oil will usually free the cat of small hair balls. One teaspoonful a day for two days, or possibly three, is usually sufficient. In stubborn cases a cat should be taken to a veterinarian for an enema or an emetic, depending upon the pet expert's diagnosis.

VACCINATION: You can practically vaccinate a cat against hair balls if you'll only be a good Samaritan and use the brush and comb on your pet daily.

SKIN TROUBLES: There are usually three different orders of skin troubles- those caused by digestive upsets (dry or moist eczema); troubles brought on by animal parasites (mange); troubles which are the result of fungus infection (ring worm). Of the three, mange is the most contagious to other cats; ring worm is contagious to other cats-and to people as well so guard yourself against infection when you handle a cat that has ring worm. All three of these skin ailments have their own identifying marks, but it is easy for an untrained person to make a mistake in diagnosis. If you are not positive about what troubles your cat's skin, ask an experienced cat owner, or your veterinarian. In general; here are the signals of these skin diseases:

1. ECZEMA: Two varieties exist. Dry eczema usually starts around the ears and face and its chief symptom is the cat's distress-Puss will tear at ears, nose, and eyes until the hair falls out. You can see the scales of dry eczema in the bare patches.

MOIST ECZEMA: This outbreak is more easily identified. Inflamed red patches, somewhat moist in appearance, are characteristic. The eczema may appear all over the body, but will concentrate in the less hairy spots. The cat's skin will be hot and sensitive.

2. MANGE: (Sarcoptic mange) is characterized by tiny red pimples on the cat's skin. As the attack advances, these pimples burst and form matted scabs. The cat's skin becomes so irritated by scratching that blood will appear.

3. RINGWORM: Watch for ring-shaped, scabby patches raised on the cat's skin.

Before being specific about cause and cure, I want to point out that many ointments that would be suitable for your own skin are absolutely taboo for your cat. Before you apply treatment, be certain the remedy is mild enough to prevent injury. Now for the troubles themselves:

1. ECZEMA is a manifestation of error in the cat's diet. Revise its food supply immediately to eliminate all starches, fish, pork, and other foods you suspect to be disturbing elements. Concentrate on feeding raw beef, whole wheat toast, and add two drops of haliver oil to the cat's food once a day. Keep the cat's bowels regular. Give it a dose of mineral oil, or a milk of magnesia tablet.

2. MANGE: As with dog mange, this skin ailment in cats is caused by a minute boring pest. The parasites have strong constitutions and may lie dormant for a long time. A cat kept in the house is in little danger of contracting mange, but owners of house cats should always consider the possibility of mange. This disease is intensely irritating to a cat, so there is constant danger that a cat will re-infect itself from the spots where it has drawn blood. A skin that is scratched too much will be permanently damaged. Do not wash mangy spots with soap. Ask your veterinarian to recommend a mild antiseptic and ointment. Bathe the spots, then apply the ointment. Keep the cat's bed fresh. Burn the paper filler after each change. Hair around the mangy spots may be carefully clipped, but avoid depriving the cat of too much fur.

3. RINGWORM: House cats are not protected from ringworm. Your cat may catch it from the mouse it captured yesterday, and unless you use caution, your cat may give it to you. Apply tincture of iodine (carefully) to the infected places. It is safer to use rubber gloves while applying this treatment. Remove and burn scabs that form on the cat. Clip the hair around the infection. Better ask a cat expert or a veterinarian to advise an ointment to relieve this fungus infection.

NOTES ON SKIN AILMENTS: Try to devise a method to keep your cat from scratching or licking itself while it has a skin disease. Some fanciers use a three-inch card-board collar which is slid over the cat's head through a hole in the centre. Make the collar comfortable by winding it with gauze, or cotton tape. This is something like the equipment used to keep a cow from jumping fences. In general, a cat will not tolerate grease on its skin. Turpentine is definitely bad for a cat, and so are coal tar preparations.

FLEAS: Outdoor cats have most of the fleas, but indoor cats may have them. If your cat wakes from slumber to make a hasty stab at itself, followed by a frantic, biting chase for the hopper-it has some fleas. Aside from the discomfort, the cat is in some danger of infecting itself while it has fleas-either by damaging the skin or by taking in the germs or eggs of some cat disease lying in wait on the body of the flea. Tape worm may be contracted this way. While bathing with antiseptic is sometimes recommended to kill fleas, the danger of catching cold is too great to make this anything but a last resort in the hands of an experienced pet-handler. Flea powder is safer. BUT, remember a cat's skin is sensitive, and "any kind of flea powder" won't do. Obtain a safe brand from a pet store, or a veterinarian.

TREATMENT: Sprinkle the cat thoroughly with powder, working it down from the face, head, and ears to the tip of the tail. Guard the cat's eyes from powder, and try to prevent it from licking the powder. It is wise to use a cat jacket, or the collar of card-board. After two or three hours, depending on the directions for the powder you use, stand the cat on newspapers and brush and comb it thoroughly. Really BE thorough, because the fleas will be only punch drunk and you will have to comb them out. Burn the papers immediately.

While the flea powder is working, remove your pet to a different part of the house so you may give its bed and general camping ground a flea-killing treatment. Flea powder, or a spray, should be poked and shot into every possible breeding-ground. If a liquid spray is used, be certain the residue is all evaporated before you return the cat to its usual living quarters. You may have to give the flea treatment twice to kill all fleas. It is possible that you will get only the adult fleas ON the first attack-there may be another hatch coming along to plague the cat later.

These are common focal points of infection in cats, especially the ears. One or a dozen illnesses may come to your 40 pet through its ears. Parasitic canker of the ear is one of the worst-and the most common. Eye inflammation (conjunctivitis) is the second. The eyes and ears of a cat are sense organs that have no business harbouring infections. Such ailments cause the cat considerable pain, and since its paws are its only instruments of surgery, there is constant danger of scratching and further infection. But more important, eye or ear ailments may seriously hamper your pet's activities.

PARASITIC CANKER: Unlike common ear canker found in dogs, this ailment is caused by an organism somewhat similar to the one causing mange. The easily recognized evidence of an attack is a brownish discharge and, since most cats are subject to it, examine your cat's ears regularly. Left unchecked, the canker spreads downward in the ear to a region difficult to treat, and may eventually injure the cat's hearing. General inflammation of the ear is usually the result of not treating soon enough. Inflammation causes the ear to swell up, and the cat may have fever and general discomfort.

TREATMENT: Begin treatment as soon as you see the first trace of the brown wax. Never use soap and water, the cat's ears weren't meant to be washed inside. Warm a little olive oil and gently swab out the ear, using a prepared swab or a dab of absorbent cotton twisted on a toothpick. Dry up the oil with fresh swabs and finish the treatment by dusting the cat's ear with powdered boric acid. One treatment won't cure the canker, because there are probably colonies of pests still active. Keep after them, but remember that the cat's ear is sensitive: proceed gently. Extreme cases need and deserve the care of a veterinarian.

EYE INFLAMMATION: This frequently follows colds, or may be the result of continued exposure to dust-filled air. As with ailing human eyes, the cat's eyelids become red and puffy. Tears form, and later a sticky discharge begins to gather and leak down the cat's face. Sometimes the eye will be covered by a film.

TREATMENT: Apply a dilute solution of warm boric acid with a saturated dab of cotton. Take care to wipe away the excess, and also any mucus that may have formed. Protect the cat's eyes by bandaging. This treatment is for simple eye disorders only. If your cat has what appears to be serious eye trouble, take it to a veterinarian.

INDIGESTION: Most digestive distress in a cat traces back to one cause wrong feeding. Indigestion, dyspepsia, colic, gastritis, and chronic constipation may be prevented by sane feeding. Indigestion and constipation seem to occur together, and it is probable that one results from the other. Constipation is easily cured if you watch your cat. When constipated the cat may vomit froth.

TREATMENT: Keep food and water from the cat for a day, its stomach needs a rest. Give a teaspoonful of mineral oil twice a day, or a teaspoonful of milk of magnesia at five-hour intervals.

NOTES ON INDIGESTION: As soon as the treatment has an effect, begin to feed the cat sparingly. Revise its menu and eliminate foods you think may have caused the trouble. Usually the cat has been getting too much starch or fat, or not enough fresh meat and grass. A straight meat diet may sometimes cause indigestion because the cat digests meat thoroughly, without leaving enough bulk to cause a proper bowel movement. Try adding asparagus to diet. More serious digestive ailments require professional care. Remember to watch your pet's elimination.

NEUTERING: Neutering is not a crime against the cat; it is often a humanitarian practice. By nature cats are very fertile-a cat can produce several mewing litters of kittens a year. This fact causes countless hordes of stray, diseased, homeless cats. Too much kitten bearing will shorten the life of a female cat. Remember this if you enjoy and value your pleasant household cat.

If you have a male cat and you expect to keep him in your apartment, castration is a practical necessity. The tendency of cat fanciers is to develop a cat of neutral sex characteristics and a fine, friendly disposition. Any male cat, kept perpetually at home, develops argumentative tendencies, a habit of yowling to the sky during mating season, and a touchy disposition.

SPAYING THE FEMALE CAT: Have this done during the latter part of the cat's first year. The operation is fairly difficult and the cat needs partial maturity before it takes place. The cat should be free from worms, and in general good health, before the operation.

NEUTERING MALE CATS: This is a comparatively simple operation, and should be taken care of between the fourth and seventh month of life. Good health is a pre-operative requisite.

[GENERAL] If you take your cat travelling, by car or train, don't feed it en route. Water is necessary, but food will bring trouble. Keep the cat in a satchel or ventilated box. Never allow pussy to be loose in your car, especially when the windows are open. Be sure your cat returns with you from a ride. An abandoned cat, particularly a sheltered pet, has little chance to survive. Don't believe the old fib that a cat can take care of itself.

Don't let your cat be a "tin can cat:" Shun, shun the can opener; it gives your cat wrong eating habits. Canned fish and canned cat food are pleasant delicacies for occasional feeding-cats love them-but they're not the foods for steady eating. Don't let your cat trick you into thinking it will tolerate nothing but a caviar diet. Just cut out ALL food for twenty-four hours and see what the cat thinks about its usual raw beef and cooked green vegetables then.

Even if you do think kitty looks cute that way, don't tie a ribbon around its neck. There's too much danger of strangulation.

If your cat is an outdoors cat don't let it drink icy water in the winter time. Warm the water a bit.

A well-fed cat catches more mice than an underfed cat believe it or not. The reason is simple. A plump cat has more energy, is more active. Catching the mouse is the cat's chief game of skill. Your cat probably won't eat all the mice it snares, but catching the quick mice is a welcome release for energy. No underfed cat has excess energy.

Never forget that cats are easily poisoned by antiseptics, soaps, or medicines that are harmless to human beings, or dogs: Tar, lysol, soaps containing carbolic acid, gasoline, turpentine, or any powders containing these things, may be fatal to a cat.

COLDS AND RESPIRATORY AILMENTS (1936)

Colds and What They Lead To: A cat with a cold in the head is just as uncomfortable as you are when you have the snuffles; and you have the solace of a handkerchief, while even the most intelligent cat can never be taught to blow its nose. Colds are sometimes called nasal catarrh, or coryza, or rhinitis, but by whatever name we call them they are just as annoying and dangerous. The beginning of a cold may be the first symptom of distemper, or influenza, or really serious catarrh, and for this reason, and also because colds are contagious among cats, you should, if you have more than one cat, isolate the infected animal at once.

Cats that are soft from a sedentary life, or logy from overeating, are more likely to contract colds than those that are sensibly fed and have plenty of exercise. Exposure, a draft, a run-down condition may bring on a cold. If you bathe your cat and do not dry it properly, it is apt to have an attack of the snuffles. Kittens are especially susceptible, and a tendency to colds is often found in youngsters purchased from pet shops or catteries where the animals are crowded together in quarters lacking air and sunshine.

A cat with a cold coming on is usually languid, and sneezes and shakes its head, trying to expel the mucus that clogs its nostrils. Examine the nose and you will find that it is warm and dry, sometimes with a thin discharge issuing from it. The eyes, too, are watery. Usually there is fever, but this you can determine only by using a thermometer, and as a cat's temperature is taken in the rectum it requires dexterity to do it. As I mentioned in Chapter II, there is a rectal thermometer for small animals, but an ordinary clinical thermometer can be used. Often, with nursing, a cold clears up in a few days, and it is not necessary to call a veterinarian. Just keep the patient warm and quiet, away from drafty windows, and give it inhalations of medicated steam several times a day to clear out the head. I have heard cat-owners say that when they tried this the cat scratched and bit and upset the steam kettle, but I think this was the fault of the owners. Accustom your pet from the first to accept necessary ministrations, and if you are firm and gentle you will not have much trouble.

I used half a teaspoonful of Vick's VapoRub in a cupful of steaming water, but five or six drops of any volatile oil, such as eucalyptus, will do. I set my cat on a chair, draping a blanket over chair back and cat like a tent, and with one hand bent its head over the steam kettle, which I held with the other hand. But if your cat struggles it is best to use a chair with a perforated seat, and set the kettle under the chair. A drop of oil of eucalyptus brushed on the fur of the forehead so that the patient will inhale the vapour is a good measure. If the mucus in the nose is obstinate, put two drops of argyrol (5 per cent solution) in each nostril twice a day. If your pet's afflicted nose is sore, rub on a little white Vaseline to soothe it. When the throat is inflamed it may help to swab it with a 10 per cent solution of argyrol. Swabs are easily made by winding absorbent cotton securely around the end of an orange stick.

Medicines, I think, should be avoided in dealing with cats, except when prescribed by a competent veterinarian. But aspirin is simple and can do no harm [a dangerous misconception: aspirin is poisonous to cats]; a quarter of a five-grain tablet three times a day for two days has been known to break up a cold. At any rate it soothes the headache that accompanies a cat's cold, just as it does yours. And be on your guard against constipation. At the first sign of it administer milk of magnesia in the morning and again at night for one day, repeating this treatment the following day in obstinate cases. The dose is from one-half to one teaspoonful of the liquid milk of magnesia, or one tablet for a small cat, two tablets for a large cat. Directions for administering medicine in its various forms will be found in the chapter on The Importance of Nursing.

A common cold does not usually affect a cat's appetite, except in severe attacks, where there is general inappetence. Unless there is fever it is well to heed the old adage and feed the cold; but remember that right feeding is doubly important at such times. Sometimes a convalescing cat is debilitated, and then half a teaspoonful of cod-liver oil is a good builder, unless it disagrees with the patient, as it does with some cats. Some take oil nicely from a spoon; for others it must be mixed with the food or put in a capsule.

Superior folk who suppose that the human race has a monopoly on diseases are surprised to learn how many respiratory ailments cats can have. And often it is a cold that ushers one of them in. Laryngitis is not uncommon in cats, and they have sinus affections, which hurt them just as much as yours do you. They have acute bronchitis, and chronic bronchitis, and bronchopneumonia, and the more serious lobar pneumonia. They have pleurisy, they have influenza, and they have cat distemper, which is not quite like dog distemper but is bad in its own way. And many a neglected cat has wasted away from tuberculosis, just as poor human beings did in pathology's dark days. Most of these diseases have their own danger flags. If you are informed you can pretty well guess, from the character of the cough, the changed breathing, or some other symptom, what it is. But do not experiment with treatment. Call the veterinary.

All respiratory diseases of course cause disturbances of one sort or another in the breathing. In some of them respiration is quickened, in others it is laboured and heavy. Abnormally fast breathing may of course result from other causes-from excitement, or fear, or exertion-but that is temporary. If you note that your cat in its own home, with nothing to frighten or disturb it, is having trouble with its breathing, then it is time to consult the doctor. Difficult breathing may come from some growth that is pressing on the air passages, but that too calls for prompt action. Into a busy New York animal clinic, one day, two women brought a magnificent tiger cat. "He can't breathe," they said. "We think he must have swallowed something."' So the veterinarian made a swift examination.

"How long," he asked, looking pityingly at the cat, who was lying down, and struggling up, and panting, and stretching out his neck in the effort to suck oxygen into his tortured lungs, "how long has this been going on?" At first the women said they had only noticed it the day before, but then they admitted it had been longer. The doctor smiled rather grimly. "A tumour on the windpipe," he said. "His breathing must have been distressful for a month or two at the very least." Poor Tiger died on the operating table. Probably he never could have been saved, but if his owners had been watchful and truly kind he might have had a quicker, easier end. Obstructed breathing, or dyspnoea, which may come from disease but is oftener due to a growth or some foreign object in the nose or throat, can be distinguished from an ordinary increase in the number of respirations by the muscular effort that the animal makes to overcome it.

Of the respiratory diseases, bronchial pneumonia is one of the most dangerous to cats. It may come from any one of various causes. If when you give your pet medicine the liquid goes the wrong way and gets drawn into the lungs, pneumonia may supervene. Exposure to the cold or wet may bring it on; so may accumulations of mucus from bronchitis. Sometimes it just seems to spring from an enfeebled condition, as in the case of a beloved Persian of mine, a very old cat whose liver became affected as livers sometimes will in old age. She was apparently recovering, when one morning I noticed a curious little catch in her breathing, and knew it for pneumonia. The veterinarian did not advise medicines or a pneumonia jacket; sometimes, he said, nursing is the only thing. When I coaxed her she would raise herself and take a little chicken or scraped beef or beef juice from my hand, and I think nursing would have pulled her through, only she was so old, and the weather was cruelly hot.

Nursing is the best help, but medicines are sometimes necessary, and there is great value in applications such as Antiphlogistine (a clay which is used as a poultice) and in mustard plasters and other counterirritants. But use them only on the advice of a competent veterinary. Do not torture a sick cat with experiments. To shave any part of a cat's body in order that the skin may be more easily reached is not, I think, a good thing to do unless it is absolutely necessary. It robs the animal of the covering that nature put there, and the coat takes a long time to grow again.

Signs of pneumonia are quick breathing, a heightened temperature, and sometimes a murmuring sound in the chest, which you may detect by pressing your ear against it. In the catarrhal form there is a short and painful cough, but in some forms there is no cough at all.

Pleurisy, which is an inflammation of the lining membrane of the thoracic cavity, generally comes on as a cold does, with listlessness and loss of appetite. As it develops the cat shows pain when moved or lifted; it uses the abdominal muscles as an aid to respiration; and if you listen closely you hear a rustling sound in the pleurae. Pleurisy is sometimes the first indication of tuberculosis in a cat.

Laryngitis, rather common among cats, is not so serious. Its symptoms are a dry cough, unwillingness to swallow solid food, and frequent retching. It may be serious if the parts swell suddenly; once I knew a cat that was saved from death by smothering only by the quick use of a tiny tracheotomy tube. But it is usually cured if taken in time, so if your pet shows an inclination to sit with its head outstretched, and coughs when you press a finger on its throat, you may guess laryngitis, and keep the cat warm and quiet, and send for the veterinary.

A symptom of bronchitis is a dry, deep cough. In this, as in most of these troubles, the medicated steam kettle brings great relief. Asthma, which most frequently attacks old cats, particularly if they have been allowed to get fat, is generally accompanied by a spasmodic cough; an asthmatic cat, like an asthmatic person, wheezes terribly at any exertion. There is not much to be done except to cut down the diet and guard against constipation. Of course if paroxysms of coughing occur, medicines are needed to relieve them.

But the best cure for respiratory diseases is good nursing; the best preventive is right feeding, sunshine, and fresh air.

DISTEMPER, TUBERCULOSIS AND INFECTIOUS ENTERITIS (1936)

Of all the diseases that afflict our cats, these three are the least curable, the most to be dreaded: distemper, tuberculosis, and infectious enteritis. Feline distemper is different in some ways from canine distemper, and though it is very contagious among cats, it is said that dogs do not catch it from them. Puppies have been known to associate with cats suffering from distemper and to remain immune. However, it is not a good thing to let healthy animals mix with sick ones. Just as with dog distemper, no scientist has succeeded in finding out much about the microbe that causes cat distemper. Really we know only that it is very virulent and that it manifests itself in many ways, of which the commonest is the deceptive one that seems to be a cold at first. This is variously called infectious catarrh, the snuffles, influenza, and, from the way that it sometimes sweeps through a cat show and even follows the champions home, "show fever."

Watery eyes and a running nose are the first symptoms of catarrhal distemper. Oddly enough, it sometimes affects just one eye, which will be so inflamed and sensitive to the light that you might think it had a cinder in it. The cat sneezes and has fits of shivering, and its hair roughens up into untidy points. Medicine is of little avail in these cases. From one to three grains of aspirin once a day for two days may check the attack and certainly will do no harm, and if there is much diarrhea (a little is salutary because it carries away the poison in the system), a pinch of bismuth subnitrate with each meal is advisable. But it is generally conceded that nursing, not dosing, is the important thing in distemper. Most veterinarians when summoned tell you this.

Make the patient as comfortable as possible in a warm, sunny room (isolated from other cats, of course), and if it shivers dress it in a cosy sweater. Protect it from drafts, but admit plenty of fresh air. Coax it to eat nourishing things. Scraped beef, beef juice, chicken jelly, egg, and milk are best. In the abdominal forms of distemper, however, meat should be avoided, lest it irritate the intestines. These attacks call for arrowroot, white of egg beaten up in milk, and similar soothing foods that are rich in albumin.

In serious attacks of catarrhal distemper the discharge from the eyes and nose becomes a thick, clogging mucus, and this should be wiped away often. Put a pinch of boric acid in a cup of warm water, wash the eyes gently with soft cotton, and clear the nostrils with a tiny swab made by wrapping a bit of cotton around the end of a wooden toothpick. This is important; we know how uncomfortable we feel if our breathing is impeded, and neglect of the eyes at such a time may mean blindness. Remember, too, that cats are unhappy if their fur is soiled, and keep all stains wiped off. Cats usually recover from mild catarrhal distemper in three or four weeks, but they should be quarantined for eight weeks longer. The distemper germ is long-lived. The room in which a cat with distemper has been kept and the bed and other articles which it has used must be thoroughly disinfected, and even when this is done it is unwise to take a healthy cat into the place in less than three months.

When the distemper germ settles in the pharynx there is trouble indeed. The cat dribbles at the mouth and hangs over its food as if it wanted badly to eat but was afraid to try. Look into its mouth, and on the throat you will see tiny inflamed cysts, which break and turn into ulcers. Unless the disease is halted, a putrid deposit presently collects in the throat, and the patient, unable to swallow, suffers so much that the merciful thing is to put it to death. There is a pulmonary form of distemper which sometimes manifests itself in pneumonia, bronchitis, or pleurisy. Abdominal distemper generally starts with vomiting and diarrhoea, and it can strike so swiftly that at the first danger signal you should call the diagnostician. The death roll in distemper is large, and the victims who recover may be left with ulcerated eyeballs, or skin eruptions, or weak digestion. Veterinarians tell me that chorea, a nervous twitching resembling St. Vitus's dance, which dogs sometimes have following distemper, is not known in cats. But I have read of cats that were left with a palsied shaking of the head, so there you are.

Infectious enteritis, the cat plague, fatal as the black typhus is to man, is sometimes hardly to be distinguished from acute abdominal distemper. Symptoms of this disease are fever, the throwing up of yellow slime, bloody diarrhoea, and great weakness. Often there are convulsions at the end. Like distemper, it has a deadly contagion. One cat lover I know lost four Persian kittens from it, in succession, in a year. After the death of a kitten she would wait three months before taking another, but the germs were still in her apartment.

Does your cat drink fresh milk? If it does, be sure that the cow has been tested for tuberculosis and found healthy, for milk from tubercular cows is the great source of this disease in cats. But cats who dwell in slums sometimes get it from eating the stuff thrown out from tenements and cheap restaurants, and from the dirt they must swallow in making their toilets, and if your pet is permitted to mingle with these unfortunates it may contract the disease from them. Tuberculosis in cats develops slowly, with increasing emaciation and weakness, and sometimes, though not always, a cough. The layman cannot distinguish it from the wasting type of distemper, which also brings loss of appetite and flesh, but, unlike distemper, it can be communicated to human beings. Just as in humans, tuberculosis will attack various parts of a cat's body-the abdomen, the bones, the kidneys and bladder, as well as the lungs. It is almost never cured, and it means great suffering for the cat.

I once found, in the dark, wet cellar of a building that had lately been vacated by a speak-easy [a sort of bar], a cat far gone in tuberculosis, and I did not soon forget the haggard misery in that feeble creature's face. It is painful to put an end to any spark of life, but I was glad to end that one. Dr. Hamilton Kirk says that death is best for all tubercular cats, whether they be homeless strays or treasured pets. And he speaks not as a cold scientist, but as a real lover of cats. Tubercular cats have been kept alive for some time by care and good food, by owners who thought they loved them, but I do not think life meant much to these cats, and I doubt the genuineness of such affection.

TROUBLES OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT (1936)

Digestive ailments make a long story, for they extend all the way from the teeth to the anus, from pyorrhoea to rectal abscesses, from stomatitis, or sore mouth, to colitis. They make up the greater part of the cat cases at animal clinics, and for this we cat-owners ought to take shame to ourselves, because wrong feeding is the chief cause. But I hope not many of us are as foolish as the coloured girl who brought a white Persian cat, miserably sick, to a veterinarian late one night. "What have you been feeding him?" the doctor asked.

[The girl answered] "Horatio had sausages and a chicken bone and fried potatoes foh dinnah. Then mah girl friend across the hall had a pahty, and she treated him to ice cream. Horatio shuah does appreciate ice cream. 'Nothah thing he likes is cigarettes. It does tickle folks to see Horatio gobble the end of a cigarette. It's a trick mah boy friend learned him." The boy friend had run to the drugstore when Horatio succumbed, and bought castor oil and buckthorn to pour down his throat. They were naively surprised that this made him worse. Now this may be an extreme case, but there are many just as outrageous.

Cats that are allowed to roam pick up things that upset the digestion, or worse. Country cats sometimes get thin from eating too many grasshoppers and beetles. And, contrary to the general belief, mice are not wholesome for cats, but fortunately well-fed cats seldom eat the mice they catch.

I do not suppose that four cats out of five have pyorrhoea, but as they grow old they are subject to it, and the cause is what it is in humans: too much soft food. If your cat rubs its face with its paw, picks at its food, dribbles from the corners of its mouth, and has indigestion, you may guess pyorrhoea. As pyorrhoea develops the teeth are loosened and the gums become soft and inflamed. Often the first indication is tartar on the teeth; this is the time to take it in hand, and clean the teeth with a soft brush or a swab dipped in a one per cent solution of hydrochloric acid, or in bicarbonate of soda. Real pyorrhoea requires the veterinarian, for it may be a case for the forceps.

Stomatitis is an inflammation of the mucous membrane of the mouth. Your pet may get it from being scalded by hot food, or from strong medicine, or from indigestion. The symptoms are bad breath, difficulty in eating, fever, and a tendency to sit with the head held stiffly forward. Open the mouth and you will find it inflamed, perhaps ulcerated. Sometimes there is a deposit at the back which the timid take for diphtheria, but it is not really that, and you need not fear contagion. The mouth should be cleansed with an antiseptic solution and the ulcers painted, but a layman should not attempt to treat ulcers.

Pharyngitis, or inflammation of the cavity into which the nose and mouth open, is a sort of extension of stomatitis, harder to deal with because the pharynx is less easy to reach. It may be caused by chills, or by bacterial invasion, or by a bone lodging in the throat. The most serious form, that caused by distemper germs, was described in the chapter on distemper. A cat with pharyngitis almost always coughs, especially when it tries to eat; but if the throat is very bad it refuses food, becomes very nervous, and hides away in corners. In its mild form this disease soon yields to treatment. Keep the patient warm, coax it with soft nourishing foods, and pin a baby's wool sock snugly around the throat, with camphorated oil rubbed into the skin under it. Two per cent lime water is a good wash for a sore throat.

Gastritis, to which cats are rather subject, usually comes from bacteria taken into the system with food that is not fresh. Cats get it from eating mice, or poisoned baits that have been put out for vermin. A distressing symptom of gastritis is thirst along with an inability to drink; the sufferer will sit by the water dish eyeing it longingly, or if it does drink or eat anything, up it comes directly, accompanied by froth. Cats lose strength fast in gastritis; the sooner the doctor comes the better. There may be gastric ulcers, and they are very serious.

Gastritis is inflammation of the stomach, enteritis is inflammation of the bowels. If your pet cries with pain when you press on the abdomen, you may conclude that the trouble has gone on down. The toxic results of constipation can bring on enteritis, but do not experiment with purgatives, for they may do more harm than good. The cat's strength must be kept up (if it recovers enough to take nourishment) with small doses of beef juice, rice water, barley water, milk, and white of egg in water. In bad cases these are introduced by way of the rectum, but this, and the drugs that are needed to relieve pain, are matters for the veterinarian.

Plain dyspepsia often troubles cats fed not wisely but too well. They show it by hiccoughing instead of purring, by emesis, constipation, halitosis, and a dull demeanor. It is a good plan, when you suspect dyspepsia and cannot immediately have an expert opinion, to starve the cat for a day or two, and to empty the bowels with an enema of warm soapy water. You can easily do this with a soft rubber ear syringe, and if your pet has been properly trained to handling it will lie quiet on a rubber apron across your lap. Fractious patients must of course be held by an aid, and their claws muffled in a towel.

Colitis, or inflammation of the lower bowel, is as painful to cats as to humans. Most veterinarians put the sufferer on a milk diet, and give enemas of starch or opium. Abscesses near the rectum are painful too. A very old cat of mine had them, and they hurt her so that I decided to see if enemas would not correct the condition, and happily they did. Kittens are subject to colic, and occasionally adult cats have it too. Usually they tell you; they cry and are very restless. A harmless remedy is a ten-grain tablet of bicarbonate of soda in water every few hours till the bloating is reduced. And a hot-water bottle on the tummy is as grateful to a cat as it is to a human being with a midriff ache.

It cannot be said too often that constipation, diarrhoea, bad breath, loss of appetite, and an abnormally large appetite are danger signs. Never neglect constipation. If your cat does not evacuate once a day, you must give it milk of magnesia, as prescribed in the chapter on Colds and What They Lead To, make sure that he has plenty of fresh water to drink, and check up on his diet to see that the cook is not giving him spaghetti or something equally harmful. And remember that a cat with diarrhoea is a sick cat.

An increased appetite may indicate worms, or intestinal catarrh, or diabetes. Refusal to eat, if persisted in, shows illness, except in the case of a homesick or grieving cat.

I met, one day, a man who had often told me of his intelligent old cat, Plato. He looked as if he had lost his last friend. He is a solitary, shy sort of man, and Plato was the whole of his family. "Plato is dead," he told me, "and I killed him." Having had to leave the city for a time, he had put his cat in a cats' boarding place, and Plato, unable to understand the separation and perhaps thinking it final, had refused to eat. And the stupid attendants who collected the dishes from the boarders' cages after a meal never noticed that Plato's meat was untouched. This had gone on till Plato died of starvation. Doctors know that it is hard to get a homesick cat to eat, and so they advise keeping ill cats at home rather than in a hospital.

WORMS AND HAIR BALLS (1936)

Worms are not good things for cats to have inside them, but I do believe they are less harmful, by and large, than are some of the remedies used to expel them. The mistaken notion that all kittens have worms and must be wormed as a matter of routine has brought a great deal of suffering to our pets. It never occurred to me to worm my cats, and so far as I knew they never needed it. I think worms do not often trouble cats that are born under sanitary conditions, that are kept clean and free of lice and fleas, and that do not eat mice or the offal of animals. Filth, vermin, and body pests are great breeders of intestinal parasites that can be communicated to cats. Of course if yours is an outdoor cat you can hardly guard it against all contamination, but fortunately cats are dainty, and the well fed ones especially so.

But if you buy a kitten from a careless breeder or a badly kept pet shop, look out for worms. There was a bargain-hunter who bought a Siamese kitten "cheap" at a pet shop, only to find when she got it home that it was infested with worms. Kittens are not born with worms, as some people think, but sometimes a few are imbedded in the fur under the mother's tail, and her babies pick them up. The bargain-hunter did not deem it necessary to call a veterinary; a bottle of vermifuge that she had used to worm her police dog had been standing on her bathroom shelf ever since its death, and she gave the wee Siamese a generous dose. She was afraid that the stuff had lost its strength, standing so long, but it had not. It was the kitten that lost its strength, and in a fortnight it was dead from enteritis. For worming is not a business for amateurs, and worm remedies that are all right for dogs may be entirely too drastic for cats. Their inner machinery is more delicate than that of dogs, and some drugs which are used with excellent results on dogs have been known to poison cats.

Cats are subject to several kinds of worms, and sometimes a laboratory test is needed to determine the kind and what the treatment ought to be. The two sorts from which they commonly suffer are the round worm and the tape worm.

The round worm is a threadlike pest, from two to five inches in length,, white or cream-coloured. Its eggs are spherical and very tiny, and very numerous in an infected cat's intestines. Sometimes the cat throws up worms; almost always the appetite is capricious, now abnormally keen, now failing; and most significant of all, the cat loses all pride in its personal appearance. Its coat looks rough and untidy, and it does not care. That is when there is a really serious invasion; if the invasion is not checked, diarrhea is likely to set in, and catarrh of the intestines or something equally bad.

Tape worms are diabolical creatures, for their hideous heads are capable of sprouting segments indefinitely, so no matter how many segments are gotten rid of there will be more as long as the head remains. Though the taenia peculiar to cats may be eight inches long, the segments measure only a tiny fraction of an inch, and are hard to identify.