Harrison Weir was the first person in England who suggested to the Crystal Palace authorities that they should hold a cat show. The authorities were dubious. Most of them knew that a cat, with the exception of the breed peculiar to the Isle of Man, had four legs and a tail ; it seemed to these gentlemen that it was quite immaterial to discover and adjudicate upon any other points. But Harrison Weir was mildly insistent; and when the authorities, still doubtful, agreed to his proposal, the next difficulty was to find the cats. Mr. Weir enlisted the services of all his friends, and, though the Crystal Palace people went forth into the highway and byways on the look out for presentable animals, the supply was still short of the required number. Then someone discovered that the Palace cellars were full of cats and kittens and mice, so a few workmen were set to work cat-hunting. The workmen also brought their own cats to the show. Hence the workman’s class in most cat shows of today.

When the opening day of the show came, it proved to be a great success. People went home and were absolutely courteous to the family cat ; for in him they saw the possibilities of future wealth in the shape of prizes. The family cat, after the manner of cats from time immemorial, went on his way without paying much attention to the matter. It annoyed him, however, to be sent on long journeys to shows, but he was consoled by the fact that, when the enthusiasm spread, he sometimes met the cat from next door at the show. It gave him unlimited opportunities to express his opinion of the other cat – opportunities of which he was not slow to avail himself.

As cat shows increased, they gradually produced the cat fancier, and the results were rather startling. Each fancier tried to develop a different type of cat, and every man fought for his own type. Mr. Harrison Weir built up his book on cats out of these varying types. The book attracted people, and gave them a great deal of information on the subject. Up to this time, the common or garden English cat had been quite good enough for everyone. A vague superstition prevailed that each longhaired cat was a Persian. Whether it came from Spain, America, Russia, France, or the East, provided it had a fluffy coat and a long tail, it was called either a Persian or an Angora. Then the belief in tortoise-shell toms began to spread. Tortoise-shell toms are, as a matter of fact, very scarce among fanciers ; but she tortoise-shells are very plentiful, especially in the north of England, and are not more valuable than any other cat.

Old ladies, who were not up in cat “ points,” became excessively annoyed when their pets did not take prizes ; and still more annoyed if a neighbour’s animal did. Consequently, cat shows gave rise to a good deal of scandal at afternoon teas. But here, the cat came to the rescue and asserted himself. Very often without any pedigree at all, he won prizes, and scored over pampered aristocrats of his race with pedigrees as long as their own tails. “You can make an exotic of some of our race,” he seemed to say, as he sat on the show bench with the prize ribbon round his neck ; “ but here am I, without any artificial assistance whatever, the best cat in the show ; and if that prize is not handed over to me I should just like to know the reason why.”

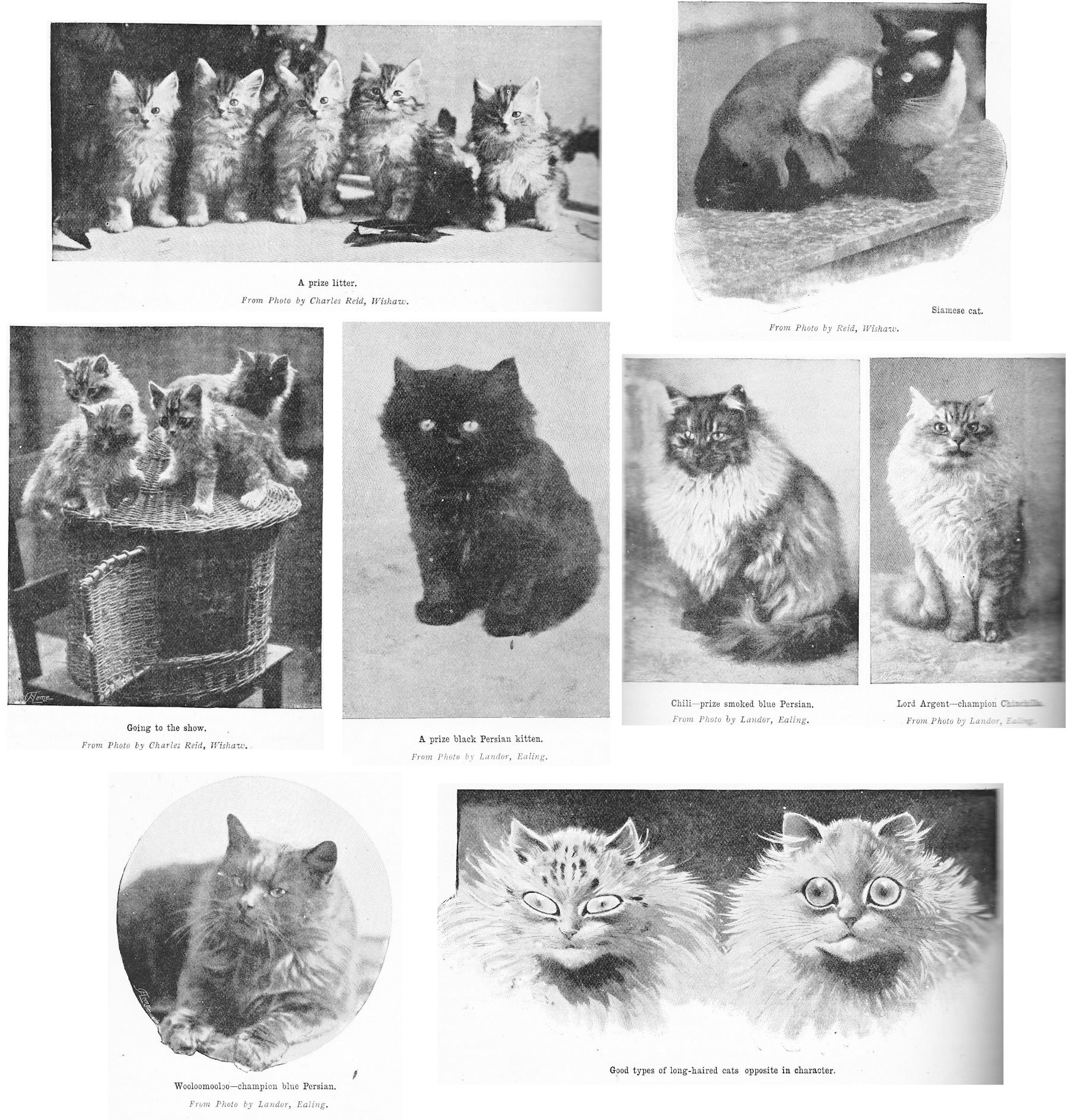

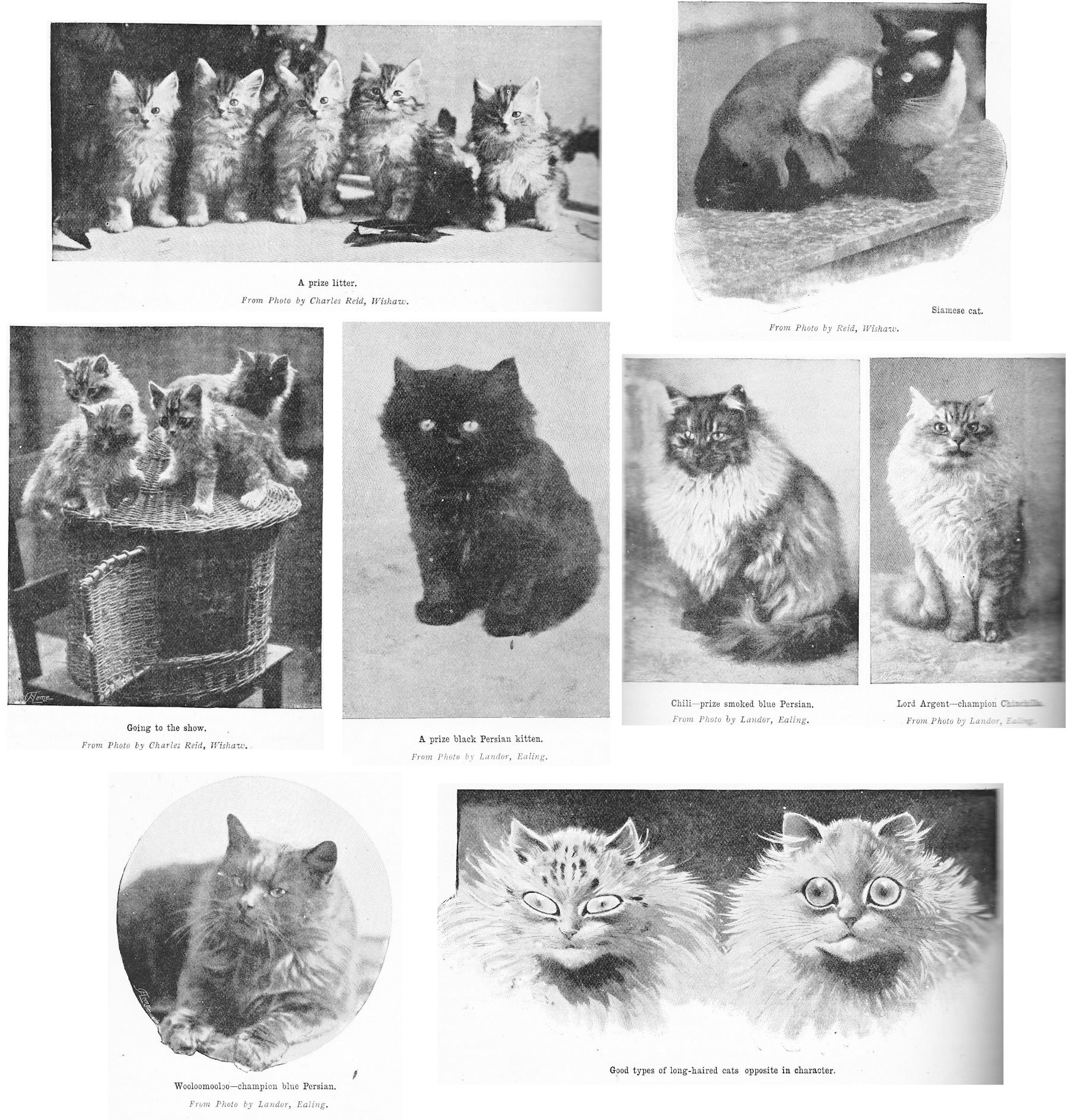

It has thus become a known law in the cat world that, though you may evolve a type of cat and it is recognised as the standard for judging, an exhibitor may come across a cat of quite another type, but which is equally beautiful ; both types have to be judged on their merits, or, perhaps, yet another type will dominate the old. This proves the extreme complexity of cat nature. While, on the one hand, you get an extraordinary number of types, yet cats build up to one form : a cat is always a cat, no matter what you do to him. Turn him loose into the woods even, and he never degenerates but always keeps his type. The classification at shows, however, has to be extended every year for the addition of little known types, new breeds', and new colours. The so-called “ Persian ” is now included in the more comprehensive title of “ long-haired,” and all long-haired cats are classed under colour, marking, and race. Short-haired cats are classified in the same way, and are generally known as tabby, whole colour, tri-colour, bi-colour, and black and white.

A long-haired show cat must be as full of points as Mark Twain’s horse, although in a different sense. He must have a round face, round, big eyes, small ears, with tufts well inside them, big ruffle and frill, tufted toes, natural long hair, close, dense undercoat, with a silky fur outside; the brush should be long, and very full. When the cat in full coat is standing up, his fur should be within two inches of the ground. The fur, however long in parts of the body, should never be out of proportion but evenly developed all over. A cat with no frill and huge stockings and tail would be called out of proportion, or with a big frill and body and no tail or knickerbockers, again would be out of proportion. An important thing in all show cats is that the cheeks should be well filled out and dropped, so that the nose and mouth should not have the appearance of being “snipey.” There are several types for the shape of the body, which are all good in their way :

1 With a ridge right down the back.

2 With back as flat as a prize cow’s.

3 Arched back, with a gradual falling over.

With regard to weight, a big cat may carry as much weight as he can. Provided he does not have the appearance of a Daniel Lambert or a beer-barrel, he may be, to take a familiar illustration, either a Sandow or a Peter Jackson. It is a curious fact that Peter Jackson, the black pugilist, is said to be the very personification of “ cat form ” ; he is so active, agile, and free in all his actions. Agility is the chief characteristic of “ cat form.” Witness, for instance, the ease with which a London cat will run up twelve feet of a perfectly straight brick wall.

The short-haired cat is usually of the somewhat thickset, arched back, cobby type, with stout body, legs, head, neck, and tail; in short, the type of the modern fox-terrier. A cat which generally spends its time in the house is of a somewhat softer type, but has beautiful characteristics. It is generally fatter, and more rounded.

When you have made up your mind to exhibit your cats, you may do one of three things.

1 Send the litter of kittens to show with their mother.

2 Send in pairs at six months old.

3 Send singly at eight months old, or over.

The danger of adopting the first course is that many kittens die from exposure. They have been kept in a warm place at home, and are not yet hardened. If the young cats are sent in pairs, the two most perfectly-matching, consistent with good breeding, gain the prize. After eight months, a cat graduates as a full-grown animal.

It is impossible to lay down any hard and fast rule for feeding cats, as everybody has a different theory on the subject. Some people rear their cats on all sorts of dainties, and others give them nothing but the simplest food. Very few people give the show cat horse meat, and cats themselves are the most fastidious of animals with regard to what they eat. In a litter of seven kittens of three months old, one will be ravenous for beetroot, another for cucumber, another crave for tomatoes, one touch nothing but rotten fish or meat, one pine for raw meat, one will eat only fish, and another nothing but bread and milk ; five out of the seven will drink water only. Each cat will have its own individuality and its own proper proportion of food. A cat that is allowed to roam about will eat more than an animal that is confined to the house. Once a cat takes to catching and eating live birds, it becomes savage and morose.

Most people who keep show cats have a cattery. The hutches are arranged each with a little wired-in run. There is one article of diet of which all cats will eat more or less, and that is well-cooked mutton, without fat, and chopped up in small pieces. The ordinary show cat is fed twice a day — morning and evening — and drinks water with the chill off. It is combed every morning, and all its clotted under-fur taken out. Another method of managing show cats is to keep them confined to rooms heated up to a certain temperature. These animals are not nearly so strong or healthy as the ordinary ones, but develop much thicker fur.

The amateur exhibitor of cats, sometimes from sheer thoughtlessness, is guilty of very cruel conduct by sending his animals to shows in baskets open to the four winds of heaven. Occasionally, very cruel amateurs indeed have been known to forward their cats to shows in a sack, tied round the neck, and with only the animal’s head projecting. The professional cat-shower, who knows his business, always has a properly-made box, which is thoroughly disinfected after every visit to a show.

A cat can go on being shown until his spine begins to drop in the middle and he loses colour. This happens when he is seven or eight years old ; he is in his prime from five to six. In ordinary circumstances a show cat does not live long after he is eight or nine years old. The excitement of being shown tells on his nerves, for a cat naturally loves quiet. A sure sign of an old cat is if his tongue always hangs out ; when young, he keeps it in his mouth. It is a peculiarity of old cats, however good-tempered they may be, that they cannot bear their spines being touched without displaying an intense nervous irritation which often goes to the length of causing them to bite their best friends.

The value of Show cats varies a, great deal. An offer of £50 was refused for last year’s winner (a tabby) of the championship and challenge cap. £25 is a very ordinary price for long-haired cats. A long-haired kitten fetches from two to five guineas, and an exceptional kitten, five or six months old, will bring from £20 to £25. A good cat, if systematically shown, can easily win prizes aggregating twenty pounds a year for or six years.

“With regard to the desirability of cats as pets,” said a to me the other day, “the ordinary cat is a kind of negative life about the house. It has not the positive activity of children ; it does not need a very great amount of attention ; it does not attach itself too much to the house ; is naturally clean, and is no more of a nuisance than you allow it to be. The town cat, in particular, is an animal born with a nature which is entirely colourless : that is, it is receptive to every impression made upon it. Although capable of great affection, it does not force itself upon you as a dog does. A cat will attach itself to you one day, and its next impression may be a stronger one - to-morrow the cook with a bit of meat, the next day a desire to play with children, the next day it fraternises with a visitor, the next day it hunts mice, the next day the canary, and on the next day it basks in the sun, oblivious to all human life - a Negative Impressionist.”

At that moment I chanced to look out of my study window', and saw my own “ Negative Impressionist ” sitting on the fence, and allowing his tail to dangle down just out of the reach of a frantic fox-terrier. His great weakness is fish, his only failing a desire to take astronomical observations from the fence when all decent cats should be in bed. I used to lure him into the house by bringing out an empty plate and calling “ fish." The first two or three times, this ruse succeeded. Now, unless I take the fish up to the fence and allow him to see it, he declines to come in. There is not much Negative Impressionism about him.