CUVIER - THE ANIMAL KINGDOM ARRANGED IN CONFORMITY WITH ITS ORGANIZATION - FELINAE

By The Baron Cuvier, Member of the Institute Of France, &c., &c., &c.,

Additional Descriptions of all the Species Hitherto Named, and of Many Not Before Noticed, by Edward Griffith, FL.S., A.S. &c. and Others.

Volume II.

Circa. 1844

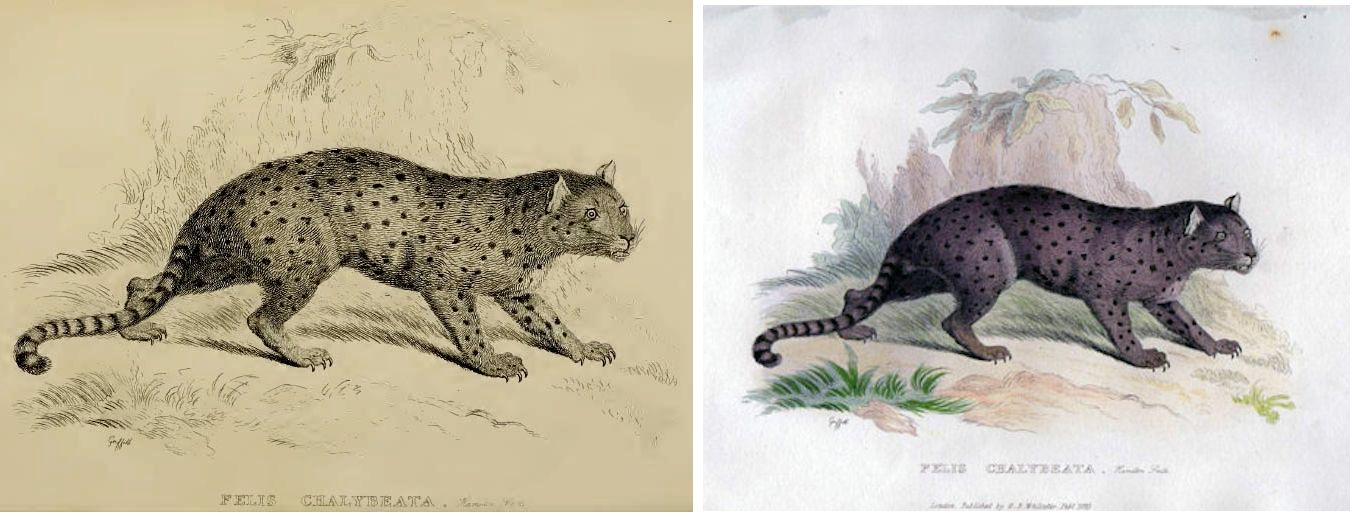

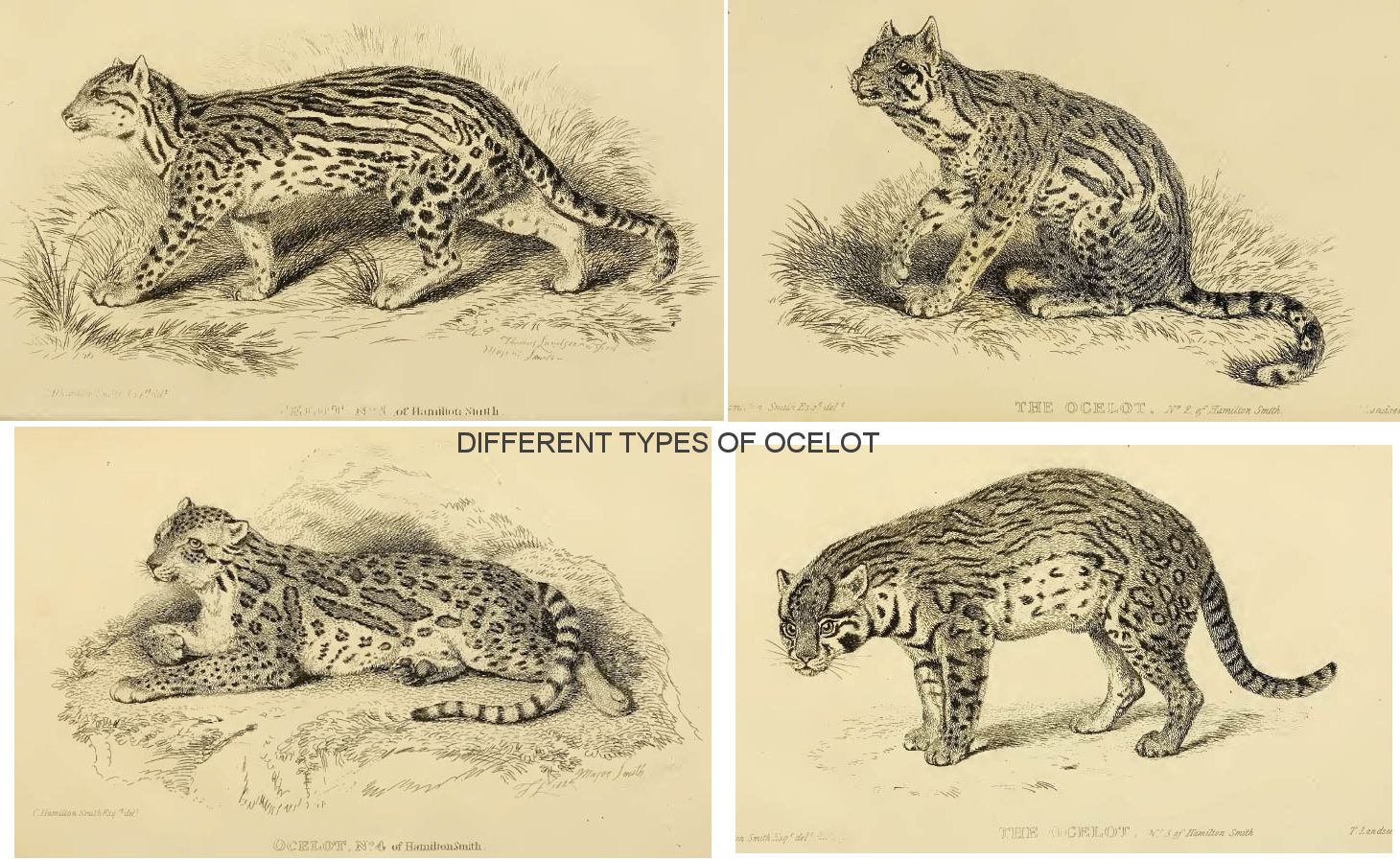

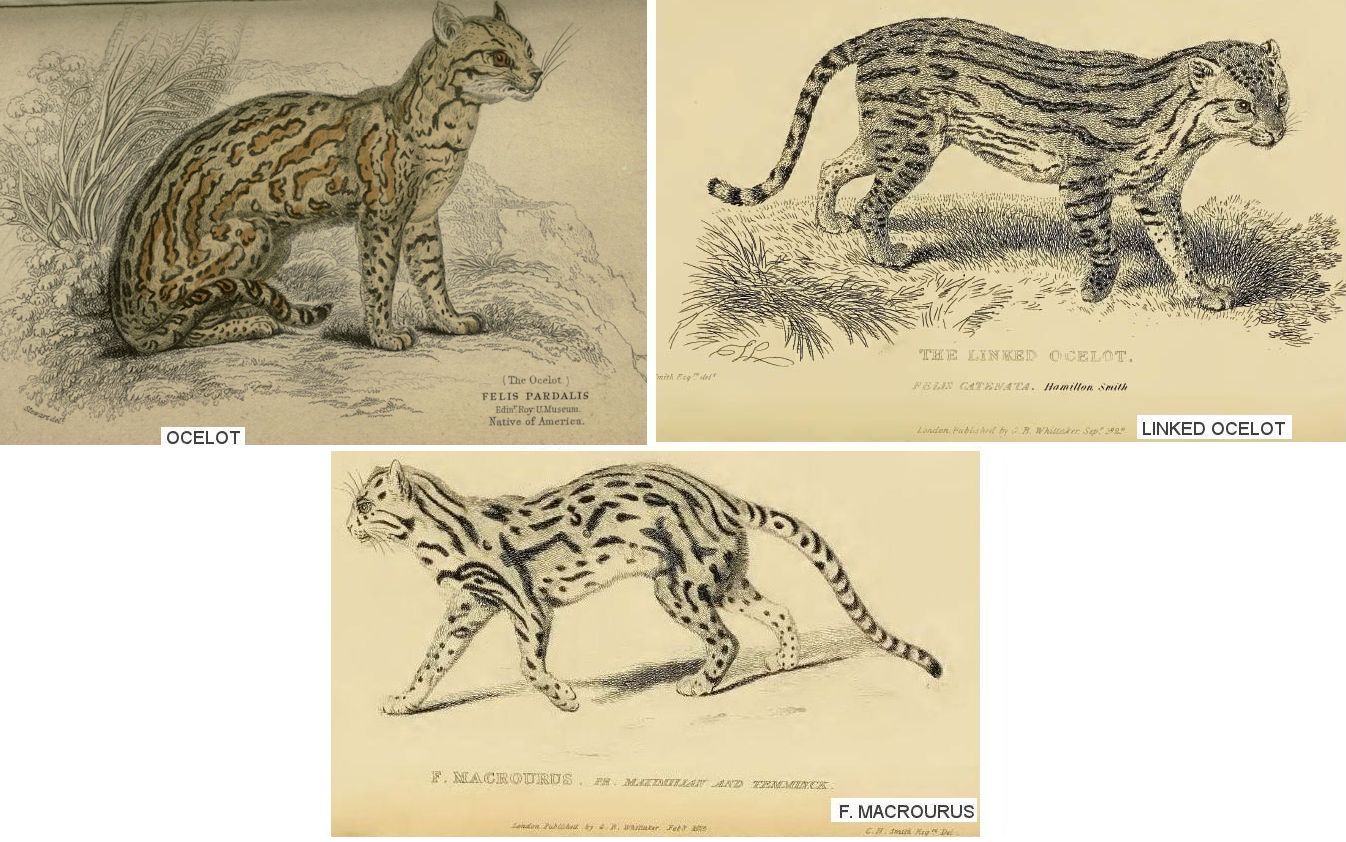

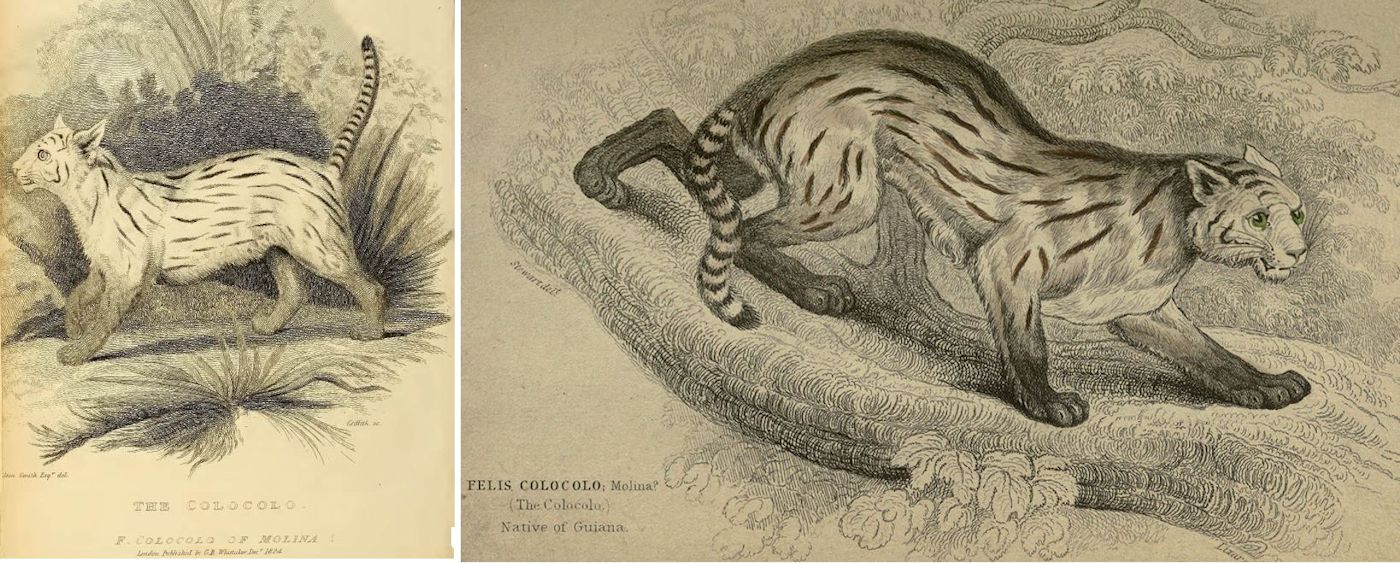

The images are from different editions of Cuvier’s book.

We are now arrived at the genus Felis, the most prominent of this terrible order of animals, a genus more distinct and isolated, more obviously characterized to the eye of common observation, and more easily defined by its systematic characters, than most others. A similarity in physical and moral character, nearly approaching to identity, prevails throughout almost all the species, from the dauntless Lion and ferocious Tiger, to their common domestic congener the Cat; size and colour form their leading specific distinctions. It is true, indeed, that one species at least, and probably another or two, exhibit a slight approximation to the Dogs, whence they have been called Canine Cats; and a similar aberration from the common type has also been observed in one or two species to the Weasel family, instances of partial exception to the above general observation.

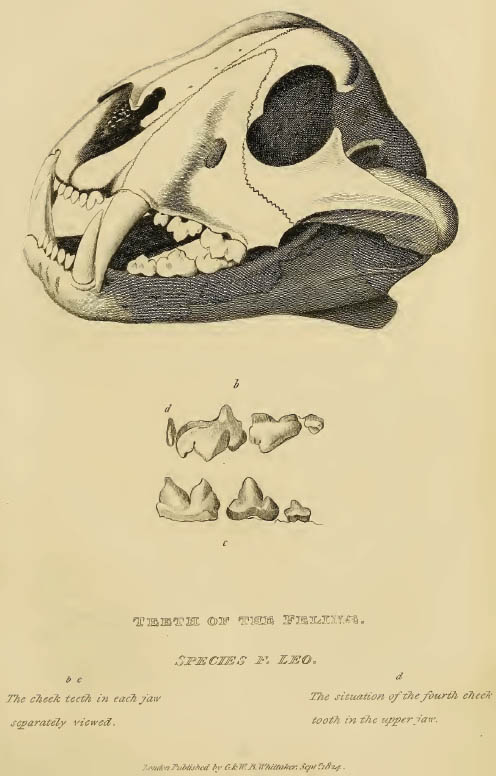

To avoid repetition, we shall not dilate generally on the physical characters of this genus, but merely in recapitulation of the text, remind the reader, that their bent trenchant retractile claws, drawn into a sheath, when inactive, and thus constantly preserved sharp for use, the small number and carnivorous character of their cheek-teeth, the number of their toes, five before, and four behind, their short muzzle, powerful jaws, and aculeated tongue, added to their moral character of natural ferocity, and appetite for a living prey, prevail in all the species.

A more particular description, however, of the fourth or flat cheek-tooth, found in the upper jaw of some of the Felines, may not be unacceptable, to which we shall, with all deference, add a few observations on the eye-pupil of the genus. In the upper jaw of most of the species is found a flat cheek-tooth, altogether differing from the rest, and which, from its singular shape, position, and apparent office, we should be inclined to call an auxiliary tooth. It is so situated as not to be seen, except by opening the mouth wide, and looking upwards. It does not protrude from the edge of the jaw, like the other teeth, but a little way up the inner inclined surface of it, and takes a direction across the lower part of the last carnivorous tooth. It is flat at the top, and seems to be intended as an anvil to receive the cutting edge of the large lobe of the last lower carnivorous tooth, so as to render it more available in acting on the food. From its situation in the mouth, it may easily escape observation; whence it is not unfrequently said, that the cats have only three cheek-teeth in each jaw. The second figure on the opposite plate is intended to show this auxiliary tooth.

The pupil of the eye is in some species oval, and in others circular. It is also capable of much alteration, not only in size, but also in figure, resulting from the degree of light acting upon it, and occasionally from some sudden mental impulse, so as to be sometimes round, sometimes oval, and sometimes a mere vertical line in the same animal.

There are some positions so universally considered as true, that no one ever thinks of doubting them; and it is, indeed, on such, that all reasoning must be grounded; but we cannot be over scrupulous in admitting, or too nice in investigating any proposition, before it is classed with those fundamental axioms as self-evident, and therefore not requiring to be demonstrated. That the pupils of Cats are oval, and that therefore they are enabled to see in the dark, is an assertion very generally made, and seldom questioned; and some naturalists, observing that the felinae vary in this particular among themselves, have separated them into diurnal and nocturnal species; distinguishing the former by the circular pupil, and the latter by that of an oval figure. It may, nevertheless, be doubted, whether the shape of the eye-pupil be at all connected with the extent of the power of vision: the size of it must, in all probability, be materially so; but it does not appear certain, that those animals which dilate the iris, so as to elongate the pupil, have also the greatest power of contracting the former, and consequently of enlarging the latter, more than others which have the pupil at all times circular.

Major Smith has observed, on this subject, that the diskous or circular eye-pupil is believed to be diurnal, and the Lion and Tiger are both, in general, associated together on this account; but the Lion, although he sees by day, may be said, probably, never to hunt his prey while the sun is above the horizon, unless pressed in an extraordinary degree. The pupil of his eye is also at all times circular, and always of a yellowish colour. The Tiger, on the contrary, will seek his prey by day and by night; and his eye-pupil is capable of either shape, and in the twilight or dark, its colour is like a blue-green flame. This remark he made, while drawing a specimen of a large Bengal Tiger at New York. The room of the menagerie in which it was placed was generally rather dark, and at the time was rendered more so by the gloominess of the weather. The animal was exceedingly vicious, endeavouring, occasionally, to strike his keeper; yet he lay in a stately, and, seemingly, unconcerned attitude, with the cleft pupils of his eyes fixed upon the Major while drawing: but if a person passed near him, they were changed instantly into a disk, and their colour altered from yellow-green to blue-green. To this facility of expansion and contraction of the pupils, which, in this instance, resulted from a mental excitement, and not from any alteration in the degree of light, may be attributed the diurnal habits of the Tiger, as also his disregard of night-fires; while the Lion, whose eyes are not calculated for the glare of day, cannot bear the effect of firelight in the dark.

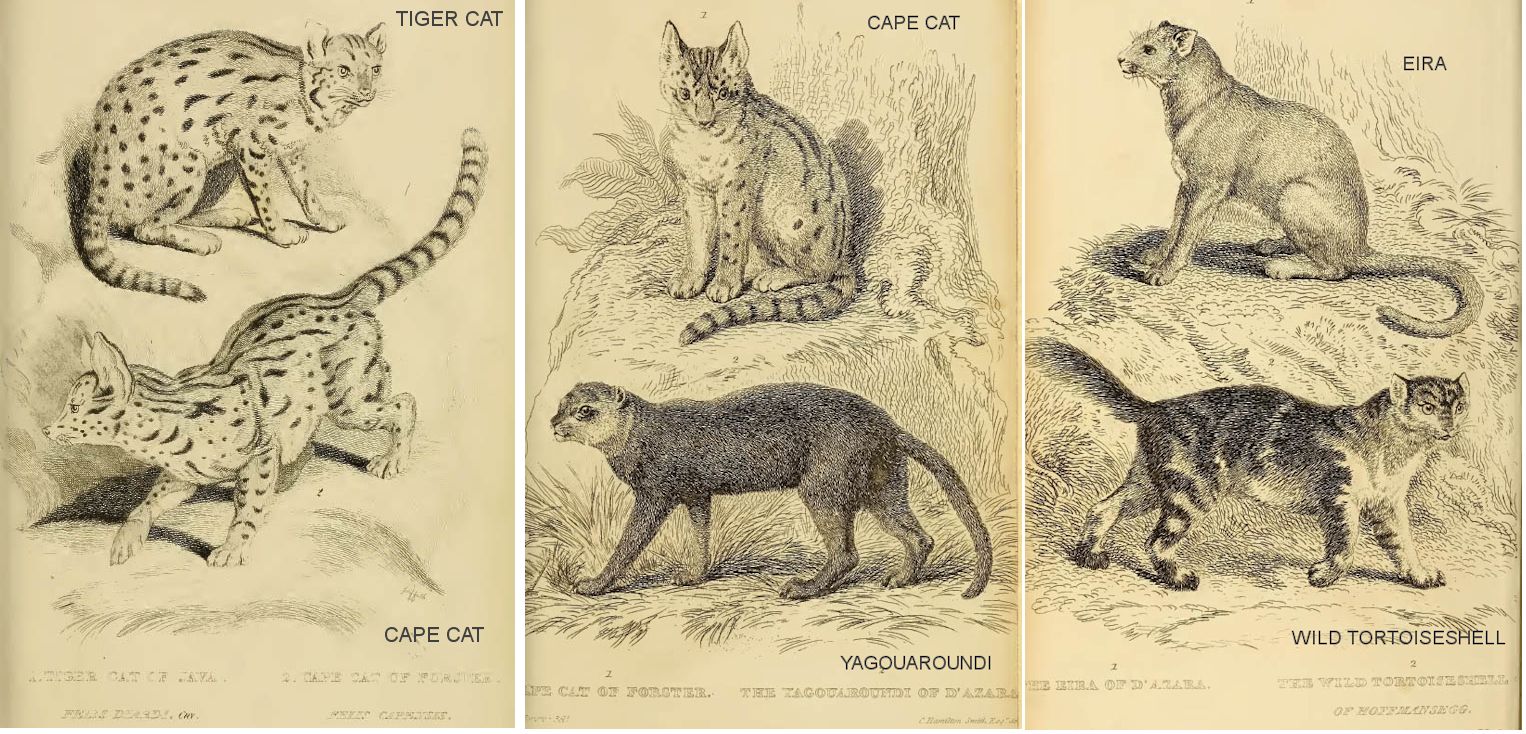

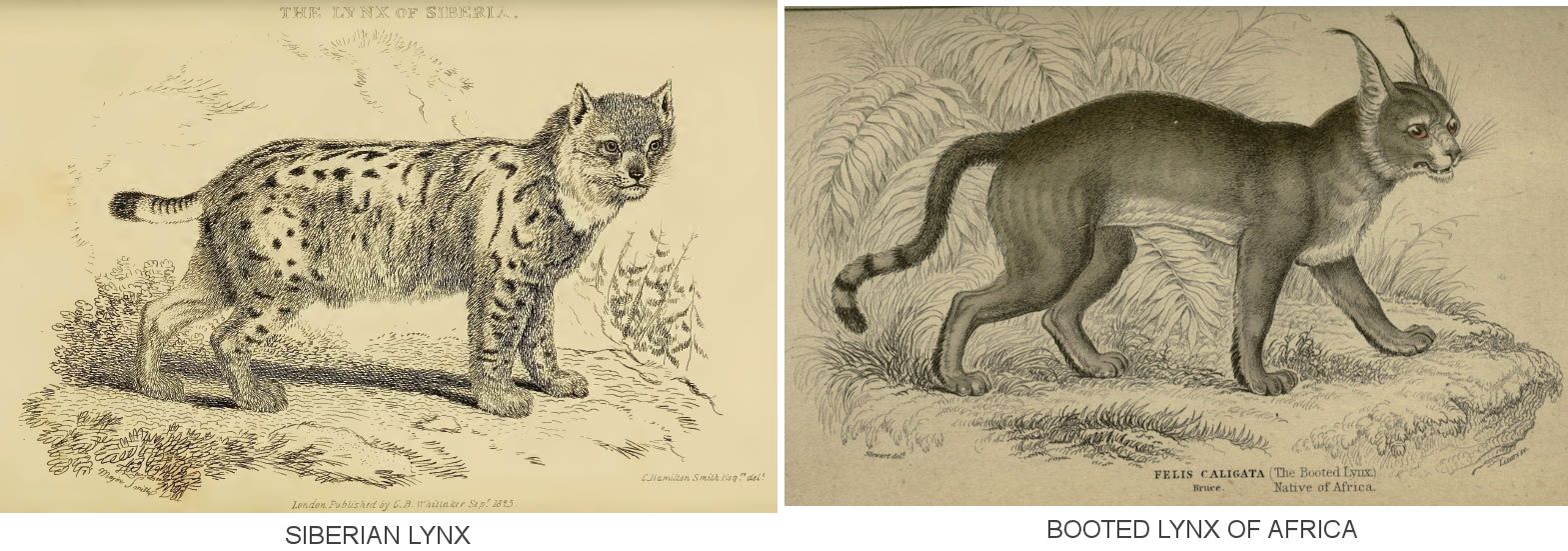

The Puma has the pupil constantly circular; yet this animal is as dangerous by day as by night; or, to speak more correctly, he will hunt his prey while the sun is above the horizon. Of the Lynxes that are found in the United States, that called by the furriers the Chat Cervier, has complete Cats' eyes; while the Felis Canadensis, which is so nearly allied to it, as at most to be a mere variety, has round pupils, yet the habits of both are similar.

The Angora Cat, when in little light, has the eye-pupils nearly, if not quite circular; they form an ellipsis more and more narrow as the light increases, till when exposed to the sun they are almost linear.

If, then, it be considered, that the Lion has round eye-pupils, though it is generally inactive by day, and hunts principally after sunset; that the pupils of the Tiger assume either shape, and that it is equally active day and night; that the Puma, like the Tiger, is equally disposed for action at all times, though its eye-pupils, unlike those of that animal, are always circular; that one Lynx has the pupils changeable as to shape, while the other has them only varying in size, and that both their habits accord; and lastly, that the common Cat, which has the pupils varying greatly in shape, though we know it sees with little light, seems to possess in the day a vision as perfect as those animals which merely increase or decrease the size of the pupil, though it continues always round; — we seem led to a probable conclusion, that there is a fallacy in adopting the form of the pupil as a physical characteristic of the disposition and habits of the animal.

The eyes of Cats and of some other animals are frequently much illuminated with a prismatic sort of light in obscurity. On this subject, says Sir Everard Home, there are two opinions; one, that the external light only is reflected, and the other, that light is generated in the eye. Professor Bohn, at Leipsic, made experiments, which proved, that when the external light is wholly excluded, none can be seen in the Cat's eye. The truth of the results was readily ascertained; it therefore only remained to determine, whether the external light is of itself capable of producing so great a degree of illumination: this was attended with difficulty; for, when the apartment is darkened, and nothing but the light from the Cat's eye seen, the animal, by change of posture, may immediately deprive the observer of all light from that source. This was found to be the case, whether the common Cat, the Tiger, or the Hyaena, was the subject of the experiment. On the other hand, when the light in the room is sufficient for the animal to be seen, the light in the eye is obscured, and appears to arise from the iris.

As these difficulties occurred in making experiments on the living eye, others were made immediately after death, and it was found, that a strong light thrown upon the cornea illuminated the eye, as in the living animal, but when the cornea was removed, the illumination disappeared. The iris was then dissected off, and the tapetum lucidum completely exposed to view, the reflection from which was extremely bright; the retina proving no obstruction to the rays of light, but appearing equally transparent with the lens and vitreous humour. These experiments prove, that no light is generated in the eye, the illumination being wholly produced by the external rays of light collected in the concave bright-coloured surface of the tapetum, after having been concentrated by the cornea and crystalline lens, and then reflected through the pupil. When the iris is completely open, the light is the greatest, but when the iris is contracted, the illumination is more obscure.

The influence, if any, the animal has over this luminous appearance, depends on the action of the iris: when it is shut, no light is seen; when the animal is alarmed, the eye glares, the iris being opened.

A very prevailing, if not a generic character, distinguishes a large proportion of the Feline, — which is, a white spot on the back of the ears. Those that are uniform in colour, as the Lion, the Puma, and the black species, as well as the common varieties of the domestic Cat, seem to be without it; but it is certainly to be found in the Tiger, Panther, Jaguar, Ounce, Hunting Leopards, Ocelots, Lynxes, and several others. In the spotted species, a black bar across the chest seems equally prevalent.

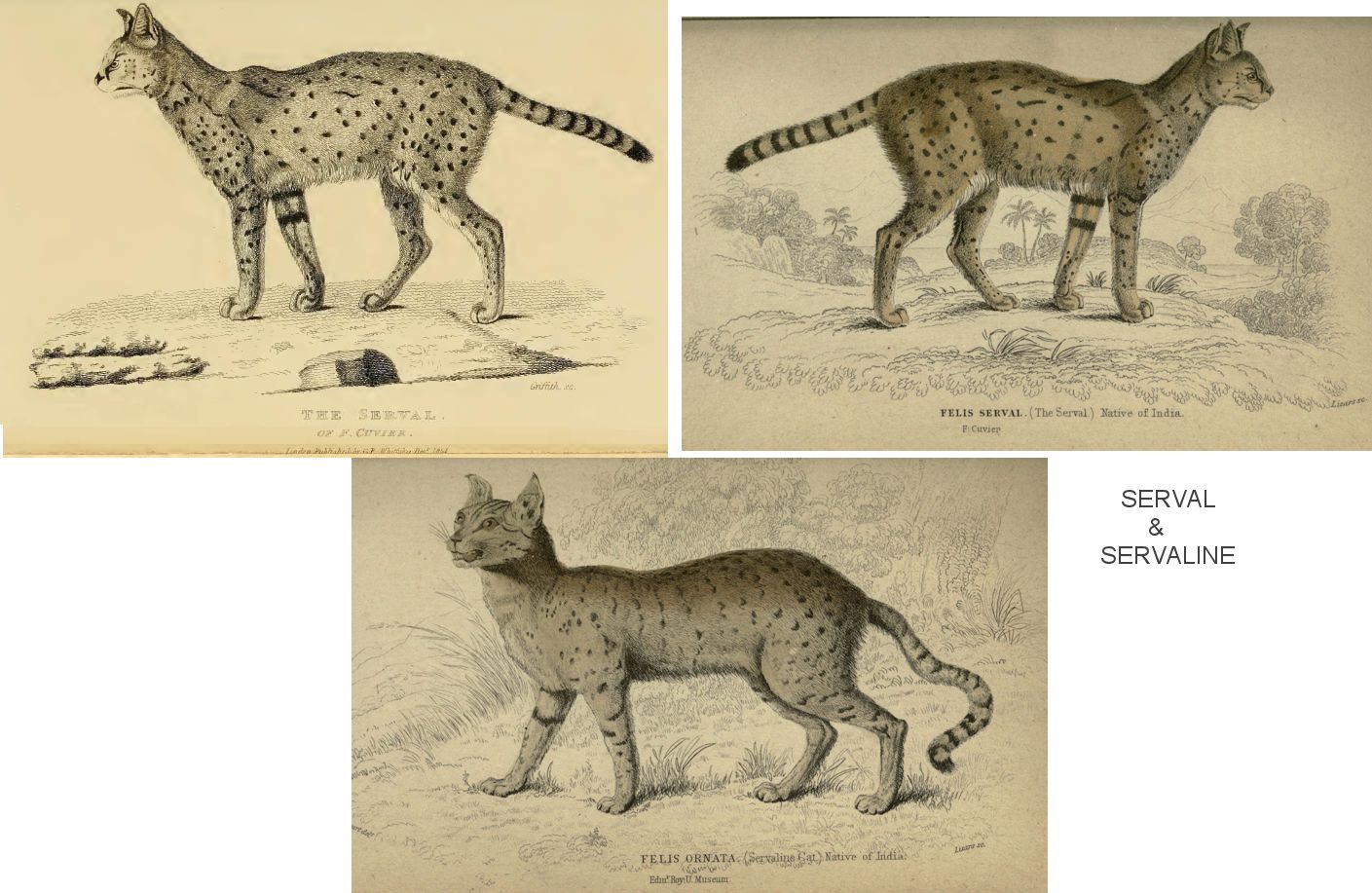

It might well be presumed, that the natural history of a genus of animals playing so conspicuous a part on the theatre of life as the Felines, would be by this time clearly known, and the species accurately defined; but such a conclusion would be very wide of truth. The Baron Cuvier commences his learned observations on the species of the Cats, to be found in the fourth volume of his Fossil Osteology, from which we shall extract largely in the present essay, by observing " that the large Carnivora with retractile claws, and spotted fur, have been for a long time the torment of naturalists, by the difficulty in distinguishing with precision their several species." Some of the species are certainly sufficiently notorious, as the Lion, the Tiger, &c.; others are known to zoologists, principally by specific descriptions, which sometimes seems to agree, and sometimes to vary, as different types successively come to light, as the Panther, Leopard, the little group of Ocelots, Servals, &c.; and many more, hitherto hidden from the eye of critical examination, exist to the scientific world, at least, only in the pages of voyages and travels: these, though named and described, are properly mere candidates for insertion in systematic catalogues, rather than recognised species. Such, however, according to our plan, will be noticed either here, or in the table, with the exception only of those that are clearly negatived; and as the authorities for their insertion will be given with them, the reader will sit in judgment upon their admissibility. Our own collection of drawings would also furnish us with figures of many apparently new species, a small selection from which will be engraved and inserted.

They may be divided into small groups by certain peculiarities of colour; the first of these groups includes the single-coloured uniform large species, and includes only the Lion and the Puma.

The superior bodily powers possessed, by the Lion, joined to his carnivorous regimen and consequent predacious habits, while they place him at the head of the beasts of prey, snd make him also the undisputed tyrant and universal dread of the plains and forests, point obviously to the situation in which he must be regarded as the first and most important species of the carnivora. Verbal description, or even the best of figures, will convey but a very inadequate notion of this tremendous animal. The rhetorician and the painter alike fail in describing and depicting the terrific work of nature exhibited in this king of beasts.

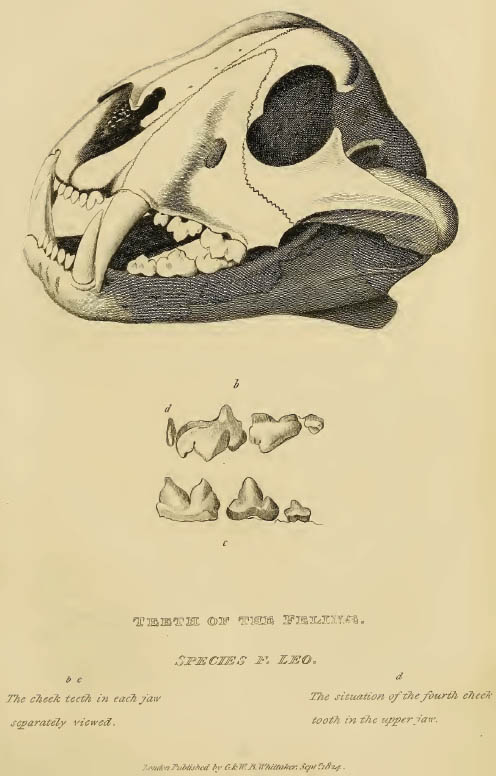

The specific characters are thus given by our author, "a large Yellow Cat, with tufted tail, the neck of the adult male furnished with a thick mane." These vary in slight degrees, as we shall notice presently. If the ancients had any authority in nature for the male Lion without a mane, sometimes figured in their statuary, the species is lost, or at least unknown to modern research [* Major Smith was lately informed by Professor Kretschmen of Frankfort, that he was in expectation of receiving from Nubia the skin and jaws of a new species of Cat, larger than the Lion, of a brownish colour, and without mane. The invoice of the articles from Cairo was already received, but the objects themselves were not arrived. This will probably, says the Major, prove to be the maneless Lion of the ancients, known to them by their acquaintance with Upper Egypt; and not unfrequently observed in the hieroglyphic sculptures of that country. ]

The period of gestation of the Lioness is about one hundred and eight days, and the young, when first born, are very small in proportion to their adult size. They arrive at maturity in about five years, and are then nearly eight feet in the length of the body, with a tail of about four feet. If we judge from the length of their nonage, and from their size and general constitution, as observed by Buffon, it should seem probable, that the average life of this animal does not exceed twenty-five years; though it has been said, that some have been kept in a state of confinement for nearly three times this period. The mane appears to increase as the Lion advances in age, and not to depend for its growth on that of the animal. The female is without it altogether. The Lion laps in drinking, but turns the tongue downwards, contrarywise to the Dog. It seems needless to enter into any general description of an animal so well known. We shall only therefore, in reference to its organs of sense, observe, that the pupil of the eye is circular; the external ear small, rounded with a lobule on the outer edge like that of the common Cat. Their other organs of sense in common with those of locomotion and generation, the peculiar retractibility of the claws, and system of dentition, correspond also with the Domestic Cat.

When young, the Lion has no trace of the mane or of the tuft at the end of the tail. These appear at about three years old. The hair of their body is then partially curled and tufted, and not smooth as in the adult state of the animal. It is remarkable also, that when young, they have a dark dorsal line, together with several transverse parallel dark stripes and faint spots, which give them the appearance, to an inexperienced eye, of being young Tigers. They are born with the eyes open, but the external ear is semipendant and does not become erect for two months. The talons also do not attain their retractile power till the animal is nearly a year and a half old. At about a year old the canine teeth appear, a period very frequently fatal to the young, at least to those born in confinement.

The characters of the Lion and the Tiger have been of late considered as perfectly similar. This assertion, contradicted by the ancients and early moderns, has wholly arisen from some remarks made by travellers to the Cape. No doubt, where similar appetites, similar propensities, similar means, and similar circumstances occur, a great similarity of character must be found. Although individuals are observed to be more undaunted and ferocious, in proportion to the increased distance at which they may be found from the habitations of mankind, more especially the civilized races, yet the Lion, we should submit, when compared with the Tiger, is a noble animal; he possesses more confidence, and more real courage; he likewise differs in his permanent attachment to his mate, and protection of his young; while the Tiger shows no partiality beyond the period of heat in the female, and is himself frequently the first and greatest enemy to his own offspring. The former of these traits of character is substantiated by a great variety of authors and testimonies, and denied only by the assertion of the colonists of the Cape, who report that the Lion, when he fancies himself unperceived, will flee from the hunters; but it must be remembered, that the Lion is generally pursued by day, and it is probable that he bears the glare of an African sun, reflected from a sandy soil, with great inconvenience. It is, therefore, as unjust to tax this animal with cowardice, because he wishes to avoid a contest, at a period when his sight is much deteriorated, as it would be to rate the hunter for his timidity, because he will not chase the Lion in the dark.

Major Smith has met with eleven instances of different Lions, which have protected and fostered Dogs, and but a single one of the Tiger exhibiting a similar kindness of disposition. In a state of confinement, they have frequently shown unequivocal marks of gratitude and affection toward their feeder and keeper, as in the case mentioned by Seneca, of which he was personally witness, of a Lion, to whom a man, who had formerly been his keeper, was exposed for destruction in the amphitheatre at Rome, and who was not only instantly recognised, but defended and protected by the grateful beast. Indeed, those animals which are exhibited as public shows, when they have been for some time accustomed to restraint, will, in general, not only become obedient to their feeder and keeper, but even show a considerable degree of liking toward him, though, in such cases, it is necessary for the man to exercise caution and discretion, and not to expose himself to the animal when feeding, or when its irritability is at all excited.

The keeper of a Lion, which was exhibited about the country, at fairs, a few years ago, was in the habit of putting his head into the mouth of the beast, having previously put on a worsted cap, to defend himself from being lacerated by the animal's tongue; and Major Smith has seen a young man stand upon a lioness, drag her round the cage by the tail, open her jaws, and thrust his head between her teeth.

“A keeper of wild beasts, at New York," says the Major, “had provided himself, on the approach of winter, with a fur cap. The novelty of this costume attracted the notice of the Lion, which, making a sudden grapple, tore the cap off his head, as he passed the cage; but perceiving that the keeper was the person whose head he had thus uncovered, he immediately laid down. The same animal once, hearing some noise under its cage, passed its paw through the bar, and actually hauled up the keeper, who was cleaning beneath; but as soon as he perceived he had thus ill-used his master, he instantly laid down upon his back, in an attitude of complete submission."

The Lion, while feeding, will exhibit a more disinterested courage than most of the Carnivora. When the prey is thrown to him at one corner of the cage, and the keeper holds up a stick at the bars of the opposite side, the animal will instantly quit his food to attack the disturber of his meal; but if the same thing be done to the Tiger, he will lie close upon his food, snort, give shrill barkings, and, at most, just rise to fly at the stick, and then drop upon his meat again."

Unlike some of the carnivorous animals, which appear to derive a gratification from the destruction of animal life beyond the mere administering to the cravings of appetite, the Lion, when once satiated, ceases to be an enemy. Hence very different accounts are given by travellers of the generosity or cruelty of its nature, which result, in all probability, from the difference in time and circumstances, or degree of hunger, which the individual experienced when the observations were made upon it. There are, certainly, many instances of a traveller having met with a Lion in the forest during day,

Who glared upon him, and went surly by,

Without annoying him;

but when urged by want, this tremendous animal is as fearless as he is powerful; though in a state of confinement, or when not exposed to the extremity of hunger, he generally exhibits tokens of a more tender feeling than is to be met with in the Tiger, and most of the Felinae.

The effect of the voice of the Lion, to be properly felt, must be heard. During sexual excitement, its noise is perfectly appalling, and produces on the mind of the bystander, however secure he may feel himself, that awful admiration commonly experienced by us on witnessing any of the grand and tremendous operations of nature. When in the act of seizing his prey in a natural state, the deep thundering tone of the roar is heightened into a horrid scream, which accompanies the fatal leap on the unhappy victim. This power of voice is said to be useful to the animal in hunting, as the weaker sort, appalled by it, flee from their hiding-places, in which alone they might find security, as the Lion does not hunt by scent, and seek for it in ineffectual flight, which generally exposes them to the sight of their enemy, and, consequently, to certain death.

The Lion is capable of carrying off, with ease, a horse, a heifer, or a buffalo. The mode of its attack is generally by surprise, approaching slowly and silently, till within a leap of the predestined animal, on which it then springs, or throws itself with a force, which is thought, in general, to deprive its victim of life before the teeth are employed. It is said, this blow will divide the spine of a horse, and that the power of its teeth and jaws will break the largest bones.

The Asiatic variety of the Lion is of a uniform yellow-colour. The mane, which is more scanty than in the African variety, is also entirely yellow. In physiognomy, as well as character, they seem to agree, but the Asiatic is rather the smaller of the two. The existence of the Lion in south-eastern Asia has not been long ascertained. Two young officers of the 8th light dragoons, during one of the campaigns in India, when out one morning on a hunting excursion, and having quitted their Elephants, were walking near a jungle; one who was more experienced in the country than his companion, suddenly observed a recent track, of what he took to be a Tiger; instantly looking back towards the jungle, they hastened forward in the direction of it, and in the middle of a field, found the mangled remains of a Nyl-ghau, (Antilope picta et Trago Camelus). They were surprised to observe no less than three distinct tracks, all leading to the prey, but from different parts of the jungle, and justly concluded that there were more than one of these fierce animals near them. While returning to their Elephant and their party, among whom was one of the gentlemen who have charge of the Elephants belonging to the East India Company, they were astonished to see a Lion come out to the edge of the jungle, open his jaws, and stretch himself, and then coolly return into the cover. Having mounted their Elephant, a large female, they proceeded into the jungle, with more courage than wisdom; but they had scarcely advanced a few yards, when the Lion sprang at them, and the Elephant, wheeling round, fled to the plain, but with a severe wound in the hough. The next day, a regular hunting party, with a considerable force of Elephants, was mustered, and when the line was formed, the half-hamstrung Elephant, trembling with anxiety, and giving proofs of her extreme uneasiness, was yet so keen as to be always her whole length before the others in the clearing of the jungle [* This was, probably, from a desire of vengeance in the sagacious animal, which continued lame, and was afterwards sold at a considerable loss. ] Before night, three Lions were killed, and thus, for the first time, probably, the presence of the Lion in India was satisfactorily established.

The distinctness of the two varieties may be inferred from this circumstance, that a Lioness of the Asiatic breed, which was in Exeter ‘Change, was frequently offered to the African Lion, which is also kept there, and was constantly refused, while his attachment still remains unaltered for the Lioness of his own country, in the same menagerie, which has produced several litters, the fruits of their intercourse. Major Smith has known two other instances of the same kind.

There is also a South-African variety of the species, with the mane nearly black; and if the specimen, lately in Exeter 'Change, be considered as an ordinary type of this variety, the head and muzzle are broader and more like those of the Bull-dog; the under jaw more projecting; the ears larger, more acuminated, and blacker in this than in the more ordinary breed.

The noxious animals yield, if not to the physical, at least to the intellectual powers of man, and, accordingly, their decrease, either generally or locally, may be observed to accord with the progress of refinement in human life. The Baron has, with much learning and research, accumulated instances of the existence of Lions in parts where they are no longer indigenous, and of their former great abundance in countries where they are now but partially known.

" It is true," says he, " that the species has disappeared from a great number of places where it was formerly found, and that it has diminished in an extraordinary degree everywhere."

Herodotus relates that the Camels which carried the baggage of the army of Xerxes were attacked by Lions, in the country of the Paeonians, in Macedonia; and also, that there were many Lions in the mountains between the river Nestus, in Thrace, and the Archeloiis, which waters Arcanania. Aristotle repeats the same, as a fact, in his time. Pausanias, who also relates the accident which befel the Camels of Xerxes, says further, that these Lions often descended into the plains at the foot of Olympus, between Macedonia and Thessaly. If we except some countries between India and Persia, and some parts of Arabia, Lions are now very rare in Asia. Anciently they were common. Besides those of Syria, often mentioned in Scripture, Armenia was pestered with them, according to Oppian. Apollonius of Tyan, saw near Babylon, a Lioness with eight young, and, in his time, they were common between the Hyphasis and the Ganges. Aelian mentions the Indian Lions, which were trained for the chase, remarkable for their magnitude, and the blackish tints of their fur.

That the species has become rare, in comparison with former times, even where it is now most abundant, may be sufficiently inferred from the Roman historian Pliny, who tells us, that Quintus Curtius was the first who exhibited many of them, at one time, in the Circus. Sylla caused one hundred, all males, to engage together, for the amusement of the people; Pompey six hundred, of which one hundred and fifteen were males; and Caesar, four hundred. The same abundance continued also under the first Emperors; Adrian often destroyed one hundred in the Circus; Antonine, on one occasion, one hundred; and Marcus Aurelius the like number on another. The latter exhibition Eutropius considers as particularly magnificent, whence the Baron infers, that the number of the species was then diminishing, though Gordian the Third had seventy, which were trained; and Probus, who possessed a most extensive menagerie, had one hundred of either sex.

A great deal of interesting matter might be added on the subject of this species, which our need of brevity obliges us to forego inserting.

The Puma (F. Concolor) is large, and uniformly yellow, without mane or tuft to the tail. It is placed next to the Lion, on account of its corresponding uniformity of colour. It is called, by the Mexicans, Mitzli; in Peru, Puma; in Brasil, Cuguaguarana, (the word Cougoua, is contracted by Buffon from this latter barbarous appellation;) and in Paraguay, Guazuara. The name by which it is most generally known is that of the American Lion; so called from a distant similarity it bears to the Lion of the old world, in the uniformity of colour before alluded to. It seems the more necessary to advert to these synonymes, because the name Cougoua, by which it is most commonly known in Europe, particularly in France, appears, probably, to have been borrowed from that proper to another animal [* See the Eira.]. The Linnaean epithets, Concolor and Discolor, have, likewise, no appropriate meaning; but Puma is its native name. Its length, from the nose to the root of the tail, is about five feet; and its height, from the bottom of the foot to the shoulder, twenty-six inches and a half; hence it is longer in the body and lower on the legs than the Lion, but it differs from that species more particularly in the shape of the head, which is small and round, and not square, as in F. Leo.

D'Azara says this animal is less ferocious, and more easy to be killed than the Jaguar; it lies concealed in the under- wood, and does not have recourse to caverns for shelter like the Jaguar. Unlike this animal also, the Puma ascends and descends the highest trees with celerity and ease, though it may be considered in general rather as an inhabitant of the plains than of the forests. He states also that it is not known to attack a man [* Buffon states that it will seize a Man if it find him sleeping, which Azara denies. ], or even a dog, but avoids both with great timidity. Its depredations are generally confined to quadrupeds of a middling size, as calves, sheep, &c.; but against these its ferocity is more insatiable than its appetite, destroying many at an attack, but carrying away perhaps only one. If it have more than sufficient for a meal, it will cover and conceal the residue for a second repast; in which it differs also from the Jaguar, which is not so provident.

D'Azara possessed a tame Puma, which was as gentle as any Dog, but very inactive. It would play with any one; and if an orange were presented to it, would strike it with the paw, push it away, and seize it again, in the manner of a Cat playing with a Mouse. It had all the manners of a Cat, when engaged in surprising a bird, not excepting the agitation of the tail; and purred when caressed like that animal.

An incident occurred a few years back, not far from New York, which seems to disprove the assertion of Molina and D'Azara, that the Puma will not attack a Man; and while it shows the ferocity of the animal, evinces that its power is not much inferior to that of the Jaguar. Two hunters went out in quest of game on the Katskill mountains, in the province of New York, on the road from New York to Albany, each armed with a gun, and accompanied by his Dog. It was agreed between them, that they should go in contrary directions round the base of a hill, which formed one of the points in these mountains; and that, if either discharged his piece, the other should cross the hill as expeditiously as possible, to join his companion in pursuit of the game shot at. Shortly after separating, one heard the other fire, and, agreeably to their compact, hastened to his comrade. After searching for him for some time without effect, he found his Dog dead and dreadfully torn. Apprised by this discovery that the animal shot at was large and ferocious, he became anxious for the fate of his friend, and assiduously continued the search for him; when his eyes were suddenly directed, by the deep growl of a Puma, to the large branch of a tree, where he saw the animal couching on the body of the Man, and directing his eyes toward him, apparently hesitating whether to descend and make a fresh attack on the survivor, or to relinquish its prey and take to flight. Conscious that much depended on celerity, the hunter discharged his piece, and wounded the animal mortally, when it and the body of the Man fell together from the tree. The surviving Dog then flew at the prostrate beast, but a single blow from its paw laid the Dog dead by its side. In this state of things, finding that his comrade was dead, and that there was still danger in approaching the wounded animal, the Man prudently retired, and with all haste brought several persons to the spot, where the unfortunate hunter, the Couguar, and both the Dogs, were all lying dead together [* This incident was related to Major Smith by Mr. Skudder, the proprietor of the Museum at New York, where the animal was preserved after death as a memorial of the story.].

D'Azara asserts, that the Jaguar cannot climb trees, but that the Puma can. The last anecdote sufficiently evinces that the latter can mount a tree; but it seems probable, that it is accomplished rather by a vigorous bound in the first instance, than by absolute climbing.

Major Smith witnessed an extraordinary instance of the abstracted ferocity of this animal, when engaged with its food. A Puma, which had been taken and was confined, was ordered to be shot, which was done immediately after the animal had received its food: the first ball went through his body, and the only notice he took of it was by a shrill growl, doubling his efforts to devour his food, which he actually continued to swallow with quantities of his own blood till he fell.

Notwithstanding such instances of the violence of disposition of this animal, it is very easy to be tamed. The same gentleman saw another individual that was led about with a chain, carried in a waggon, lying under the seat upon which his keeper sat, and fed by flinging a piece of meat into a tree, when his chain was coiled round his neck, and he was desired to fetch it down; an act which he performed in two or three bounds, with surprising ease and docility. A tame Puma, which died recently, was some time in the possession of Mr. Kean, the actor. It was quite docile and gentle. After the death of this animal, it was discovered that a musket-ball, in all probability, had injured its skull, which was not known in its lifetime.

Many of the actions and manners of the Jaguar and Puma have been confounded by different describers. It may perhaps be observed generally, that the Puma is of the most cruel and sanguinary disposition in a state of nature, though easy to be tamed; but is inferior to the Jaguar in bodily powers, and still more in energy and courage.

Though this species is found from Patagonia to California, the Baron has not been able to ascertain any hereditary varieties. Some individuals indeed seem of a deeper colour, and others exhibit indications of spots, the colour in places being more opaque in certain angles of light; but such may be attributable to age, sex, or circumstances, and not probably to actual varieties.

The Black Tiger of Laborde is erroneously applied, according to Cuvier, to a Black Couguar, by Buffon, the existence of which he doubts.

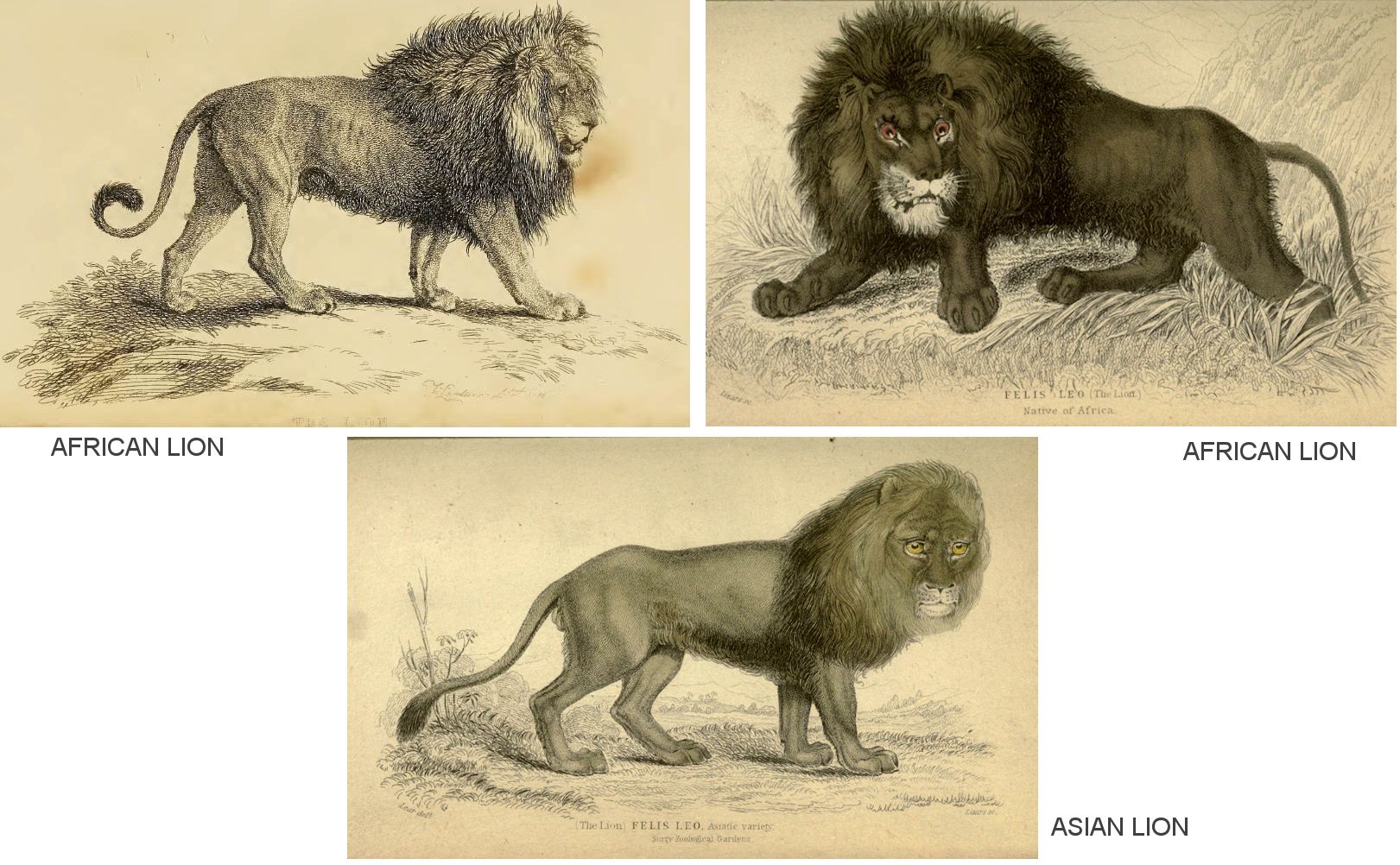

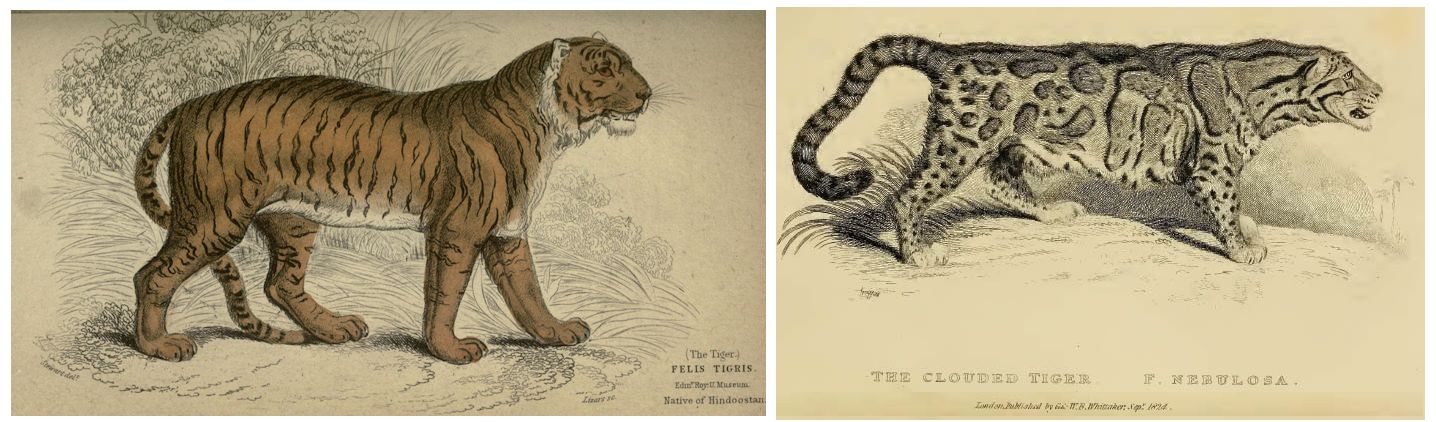

In arranging the various species of Felinae into groups, the Bengal or Royal Tiger will be found nearly isolated. He is easily distinguished from all other species by his transverse dark stripes. Compared with the Lion, he is thinner and lighter, and has the head rounder. The upper part of the body is yellow, the under part white. The whole internal face of the ears, and a spot on the external surface round and over the eyes, the end of the muzzle, cheeks, throat, neck, chest, belly, and internal sides of the limbs are white; and the tail is annulated with black on a whitish-yellow ground. The eye-pupils are generally said to be round, and indeed we have never observed it otherwise; but in the instance already mentioned, witnessed by Major Smith, they assumed an elliptical figure. The black bands are extremely irregular, and vary in different individuals. We shall not describe its person further, but merely refer to our figure of a specimen lately at Exeter 'Change.

Beneficence, however capriciously exercised, may be said occasionally to exhibit itself in the lion; but the ferocious character of the Tiger, in its natural state, presents no such palliation. When its appetite is satisfied, the former seems no longer delighted with blood; but butchery appears to afford gratification to the latter, even after its hunger has been satiated. This animal is the scourge of Asia and the Indian Islands. Equal to the Lion in stature, though generally inferior in strength, it wants not courage and ferocity to attack that animal; but although the combat is sometimes furious, it generally falls a victim to its temerity in so doing, unless some disparity of age or other circumstance should bring the strength and power of the two animals more to a level. Its swiftness and strength enable it to seize a man while on horseback, and to drag, or rather to carry him in its mouth by bounds and leaps into a jungle or forest, in spite of all efforts to prevent it, short of musket-balls: indeed, the weight of a man, or even of a more ponderous animal, in its mouth, does not appear to incommode or delay the ordinary swiftness of the beast.

Mr. Marsden informs us, that the Tigers in Sumatra prove to the inhabitants there, both in their journeys and even their domestic occupations, most fatal and destructive enemies. The number of people usually slain by these rapacious tyrants of the woods is almost incredible. Whole villages, are sometimes depopulated by them. Yet from a superstitious prejudice, it is with difficulty they are prevailed upon, by a large reward which the India Company offers, to use methods of destroying them, till they have sustained some particular injury in their own family or kindred, and their ideas of fatalism contribute to render them insensible to the risk. Their traps, of which they can make a variety, are very ingeniously contrived. Sometimes they are in the nature of strong cages, with falling doors, into which the beast is enticed by a goat or dog enclosed as a bait. Sometimes they manage so that a large beam is made to fall in a groove across the Tiger's back; at other times it is noosed about the loins with strong ratans, or led to ascend a plank nearly balanced, which, turning when it has passed the centre, lets the animal fall upon sharp stakes prepared below. Instances have occurred of a Tiger being caught by one of the former modes, which had many marks in its body of the partial success of this last expedient.

The Tigers of Sumatra are very large and strong. They are said to break the leg of a Horse or Buffalo with a stroke of the fore-paw, and the largest prey they kill is, without difficulty, dragged by them into the woods. This they usually perform on the second night, being supposed on the first to gratify themselves with sucking the blood only. Time is by this delay afforded to prepare for their destruction; and to the methods already enumerated, besides shooting them, may be added that of placing a vessel of water strongly impregnated with arsenic near the carcass, which is fastened to a tree, to prevent its being carried off. The Tiger having satiated itself with the flesh, is prompted to assuage its thirst with the tempting liquor at hand, and perishes in the indulgence.

Buffon's assertion, however, that the nature of the Tiger is perfectly incapable of improvement, is rather too strong, as many instances have evinced since the time that Buffon wrote. A full-grown Tiger was lately in the possession of some of the natives at Madras, who exhibited it held merely by a chain; it was indeed kept muzzled, except when it was allowed (which was occasionally done) to make an attack on some animal, in order to exhibit the mode of its manoeuvring in quest of prey. For the purpose of this exhibition, a sheep in general was fastened by a cord to a stake, and the Tiger being brought in sight of it, immediately crouched, and moving almost on its belly, but slowly and cautiously, till within the distance of a spring from the animal, leapt upon and struck it down almost instantly dead, seizing it at the same moment by the throat with its teeth; the Tiger would then roll round on its back, holding the sheep on its breast, and fixing the hind claws near the throat of the animal, would kick or push them suddenly backwards, and tear it open in an instant. Notwithstanding, however, the natural ferocity of these animals in general, the individual in question was so far in subjection, that while one keeper held its chain during this bloody exhibition, another was enabled to get the carcass of the sheep away by throwing down a piece of meat previously ready for the purpose.

Three specimens in the Museum at Paris became extremely tame, and Mr. Cross has had instances of Tigers, taken quite young, and bred up in a state of confinement, exhibiting nearly as much gentleness as the Lion under similar circumstances; by showing attachment to their keeper, and, in one instance, to a Dog, which was exposed to one of them; so that their nature appears, in some degree, capable of training and education; and the furious character attributed to the Tiger must he considered as applicable to it only in a wild and unfettered condition. But however the disposition of the Tiger when in confinement may yield to judicious treatment, it is very different in a state of nature, and may be deemed a sanguivorous animal, as it sucks the blood of its victim previously to tearing or eating it; and, after having so done with one animal, will leave the carcass and seize on any other that may come in sight, suck the blood of this also with the most horrid avidity, which will induce it almost to bury its face and head in the body of its prey. We are, therefore, not disposed to palliate its natural ferocity, but only to give it credit for its capability of improvement.

Tigers' skins vary as to the number of stripes and brightness of the colours, which latter abates in some degree when the animal is living under restraint, and much more when a skin is dried and prepared for commercial purposes.

The Tigress is pregnant about fourteen weeks, produces four or five at a time, and has been known to breed when confined. When first born, the young do not exceed the size of a Kitten about three months old. They are of a pale-gray colour with obscure dusky transverse bars, like those proper to the Lion of the same age.

A white variety of the Tiger is sometimes seen, with the stripes very opaque, and not to be observed except in certain angles of light. We have engraved from a specimen of this variety, formerly in Exeter 'Change.

We have already had occasion to offer a few observations on the production of mules, considered quite independently of the standing mystery of fecundation. The instance quoted was that of a breed between the Common Chacal and the species or variety of Senegal. We have at this place to notice a similar reproduction between two species of a more prominent character on the great theatre of life, between, in fact, the two tyrants of the worlds — the African Lion and the Asiatic Tiger. The recent discoveries of intermediate genera, discoveries resulting principally from the superior degree of attention lately paid to comparative anatomy, have puzzled and confused the strict systematic zoologists. The small portion of the animal kingdom contemplated in the previous pages, has furnished several instances of these intermediate animals partaking, in many points of character and peculiarities, of distant and strongly-marked genera. It has also furnished ample proofs of the effects of secondary causes on animal organization, and demonstrated that all the varieties of animated nature before us are not the result of distinct acts of original creation, but are, in fact, from time to time, springing up before our eyes.

Mr. Cross, at Exeter 'Change [. . .] has succeeded twice in producing a cross breed among these animals. These were between the Black Leopard, generally treated as a distinct species, and the common African Leopard. The male was the black variety. Three or four individuals of this breed are still exhibiting about the country. The offspring of varieties are generally observed to partake of a middle character [. . .] If a thoroughbred Dog be crossed with a different variety, the consequences will be manifested in the offspring for several generations. But this did not appear to be the case with the cubs bred between the black variety and the Common Leopard; they were in all respects like the ordinary cubs of parents both of the common breed.

But to return to our Lion Tiger-cubs. Mr. Atkins, an itinerant exhibiter, and dealer himself, bred the Lion, the father of these cubs. He was a very fine and very valuable beast, for his beauty and the docility of his disposition, the ferocity of which had never been entirely developed by natural habits. At the period in question, he was about four years old. The Tigress, the mother of the cubs, is supposed to be about four or five years old. She has been in Mr. Atkins's possession about two years, and was, probably, taken very young, as the gentleness of her disposition seems to evince. These two animals, ever since the arrival of the Tigress, have been confined in one den, and have always agreed well together. From the beginning of their being so placed, there had been frequent possibility of issue, though the first, consisting of a litter of three cubs, was not born till the 17th of October, 1824, the result of a more particular intercourse, which lasted ten or twelve days, in the beginning of the previous July. They were born at Windsor, and were shortly afterwards honoured by a visit from his Majesty. The Lion, unfortunately, died about six weeks afterwards.

The cubs were taken from the Tigress immediately after birth, and were fostered by several bitches and a Goat; they are all alive, and promise, at present, to attain maturity. In regard to their personal appearance, we feel constrained, after what has been already said, to be very brief in our descriptions, an omission, however, we hope to compensate by the figures. These show them at three months old, and we have added figures of the young, both of Lions and Tigers, that they may be compared with this singular breed. The young of the Lion are calculated to deceive an inexperienced observer, from the fact of their being striped transversely, so as to induce the opinion, at first sight, that they rather belong to the Tiger, and, in this respect, the cubs in question agreed with those of the Lion. In the young Lions, however, these stripes soon become obliterated, but in those before us, they appear to be getting more decided and permanent, and, in fact, to be assuming the permanent Tigrine character. Our Mules, in common with ordinary Lions, were born without any traces of a mane, or of a tuft at the end of the tail. Their fur, in general, was rather woolly; the external ear was pendant toward the extremity; the nails were constantly out, and not cased in the sheath; and, in these particulars, they agreed with the common cubs of Lions. Their colour was dirty-yellow or blanket-colour; but from the nose over the head, along the back, and upper side of the tail, the colour was much darker, and, on these parts, the transverse stripes were stronger, and the forehead was covered with obscure spots, slighter indications of which appeared also on other parts of the body. The shape of the head, as appears by the figures, is assimilated to that of the father (the Lion); the superficies, of the body, on the other hand, is like that of the Tigress.

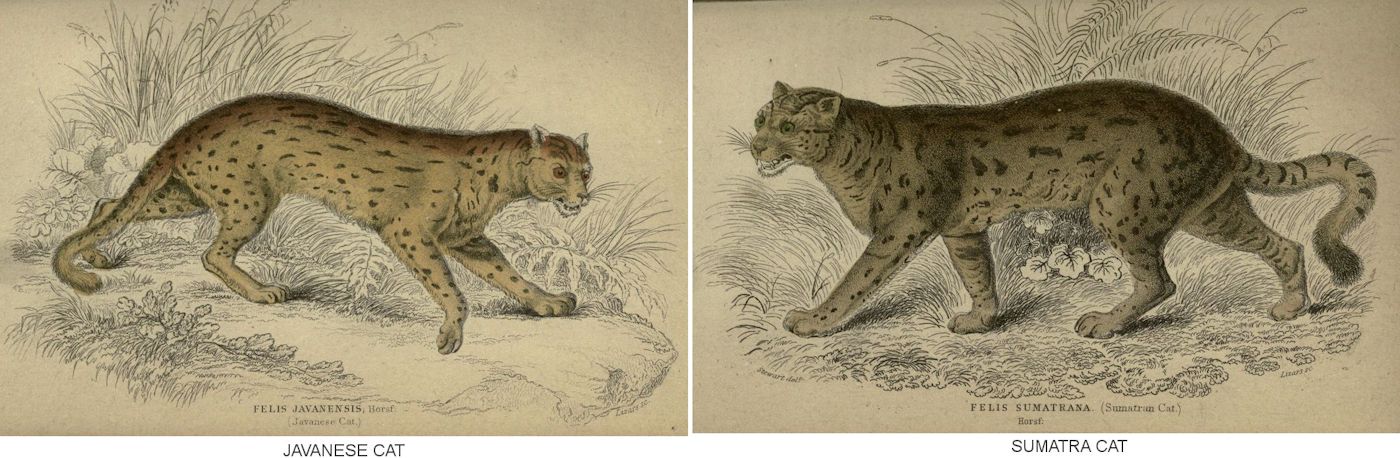

In our collection of drawings, are three figures from a curious and unique specimen, which was for some months in the possession of Mr. Polito, at Exeter 'Change. Major Smith also took a hasty sketch from the same; and Mr. Landseer made another. We have engraved this animal from the last mentioned drawing, under the name of the Nebulose or Clouded Tiger, in reference to the peculiarity of the spots or rather patches, which covered its skin. It acquired the name among the keepers, at the menagerie, of the Tortoiseshell Tiger. The head of this animal was small compared with its general bulk. The throat was thick; the body long, heavy, and cylindrical; and the legs very thick, short, and muscular. The tail also was remarkably thick and long. The extreme irregularity of the markings of this animal render a compressed description difficult. The forehead and the limbs, both outside and within, were covered with numerous small, close spots; on the sides of the face, were a few diagonal stripes; the sides of the throat also, and the dorsal line were marked with long, irregular, black stripes, with but little parallelism or regularity of angle. The whole sides of the animal were covered also with black stripes, forming a few large irregular enclosures, some nearly round; others approaching a long square or oblong, thus assuming something like the irregular uncertain figures of a passing cloud, or the bright yellow and rich brown of tortoiseshell, when viewed by refracted light. The tail was marked with many annuli, almost from beginning to end; and the whole appearance of the animal was excessively beautiful.

The irregular, circular, and oval open patches on the sides of this animal, might approximate it, in some measure, to the group of Ocelots; but its Asiatic habitat and large size, separate it entirely from these American Cats, and bespeak its relative situation among the Felinae to be after the Striped Tiger, and before the group designated by circular open spots. We are unable to give the particulars of his dimensions, but in the bulk of his body, and the size of his head, he was said to be nearly equal to the Bengal Tiger, though his legs were shorter, and appeared still stronger; his tail was also much thicker, and appeared much browner and duller. He was fierce in disposition, but was less active and lively than the Bengal species; nor did his eye convey that treacherous watchfulness of glance observed in the latter animal. He was said to have been brought from Canton.

The specimen in question, was taken into the country with an itinerant exhibition, and died there, and so little attention did Zoology, at that time, receive here, that, as far as appears, its skin was cut up to make caps for the keepers, and no vestige of the animal is now known to remain. It seems, however, there is no doubt of the distinctness of this species, as we are informed Sir Stamford Raffles is acquainted with the animal as indigenous in Sumatra. We may, therefore, hope for some more detailed particulars of it from that distinguished officer, and able writer.

[* After the above observations on this animal were printed, No. 4 of the Zoological Journal came to the hands of the Editor, in which is amply fulfilled his anticipations of further and satisfactory particulars of the species, at least, presuming the identity of that, there described, with the one noticed in the text.

These particulars are furnished by Doctor Horsfield, in his usual detailed and masterly manner, with the addition of various interesting remarks by Sir Stamford Raffles. Under present circumstances, we have only the opportunity of inserting Sir Stamford's notice of the animal, with a few additions, by way of explanation, which seem to be required. A specimen of this species, that described by the Doctor, arrived in England in August last, and is lately dead. Sir Stamford refers to this and to another individual under the native name. In regard to the dimensions, he says, " A small Rimau-Dahan, lost in the Fame, which had been living in my possession about ten months, and might have been four months old, when he first came into my possession, attained a size of about one-third larger than the specimen which was brought to England last August, (length from nose to tail, three feet; length of the tail, two feet eight inches; height one foot four inches.) The colours and marks were nearly the same, but more defined, and nothing yellow or red about it, the black having a striking velvety appearance. The tail was longer and more bushy than in the latter specimen. This was obtained a few days before I last left Bencoolen, in April. It was then smaller than the Common Tiger Cat, and only distinguishable from that animal, by the length of the tail, breadth of the paw, and colours. The natives assert that they do not attain a much larger size than the first specimen, and, perhaps, the full size of the wild and full-grown animal may be fairly taken as half as large again as the present specimen."

To the preceding remarks on the dimensions of the Rimau-Dahan, Sir T. S. Raffles has added the following particulars regarding its manners: " Both specimens, above-mentioned, while in a state of confinement, were remarkable for good-temper and playfulness; no domestic kitten could be more so; they were always courting intercourse with persons passing by; and in the expression of their countenance, which was always open and smiling, shewed the greatest delight when noticed, throwing themselves on their backs, and delighting in being tickled and rubbed. On board the ship, there was a small Musi Dog, who used to play round the cage and with the animal, and it was amusing to observe the playfulness and tenderness with which the latter came in contact with his inferior-sized companion. When fed with a fowl that had died, he seized the prey, and after sucking the blood and tearing it a little, he amused himself, for hours, in throwing it about and jumping after it, in the manner that a cat plays with a mouse before it is quite dead.

“ He never seemed to look on man or children as prey, but as companions; and the natives assert that, when wild, they live principally on poultry, birds, and the smaller kinds of deer. They are not found in numbers, and may be considered rather a rare animal, even in the southern part of Sumatra. Both specimens were procured from the interior of Bencoolen, on the banks of the Bencoolen River. They are generally found in the vicinity of villages, and are not dreaded by the natives, except as far as they may destroy their poultry. The natives assert that they sleep and often lay wait for their prey on trees; and from this circumstance, they derive the name of Dahan, which signifies the fork formed by the branch of a tree, across which they are said to rest, and occasionally stretch themselves.

" Both specimens constantly amused themselves in frequently jumping and clinging to the top of their cage, and throwing a somerset, or twisting themselves round in the manner of a Squirrel when confined, the tail being extended, and shewing to great advantage when so expanded."

Dr. Horsfield refers to a figure by Howitt, published by the editor of the present undertaking, some time ago, in an incomplete work, (the remainder of which is cancelled,) and also to the figure already given in a previous number of this work, under the name of Felis Nebulosa; and having compared these with his specimen, he doubts the identity of the species of both individuals intended, and, therefore, drops the name of F. nebulosa, and in anticipation of M. Temminck, appropriates that of F. microcelis, which that gentleman had given to an inedited species in his possession, said to be the same as that of Dr. Horsfield. A comparison of our figure, here, merely (for of Howitt's accuracy, in general, little can be said,) with that by Mr. Daniel, which illustrates the Doctor's description, has led us, we confess, respectfully, to a different conclusion from that of Dr. Horsfield. Major Smith, it is true, as we shall see, suspects they are varieties. It will be seen, by the text, that our figure was taken from the specimen to which, also, the Doctor alludes, as identified with his species, under the name of the Fox-tailed and Tortoiseshell Tiger.

Howitt's drawing was purchased by the editor a few years back, of that artist, and was, it seems, copied, though not at all faithfully, from Major Smith's sketch. To the species intended, the editor, long since, applied the epithet nebulosus, which Major Smith adopted. Knowing, therefore, no more of the type, he sent the Zoological Journal to Major Smith, at Plymouth, who has returned, in effect, the following particulars. He gave, it seems, a copy of his drawing of the animal, together with his manuscript notes upon it, in 1817, to the Baron Cuvier, in whose collection, and in that of his brother, M. F. Cuvier, he saw it during the last summer. M. Temminck he believes, also, was first made acquainted with the species from his (the Major's) drawing, in 1820, at Amsterdam, at least, M. Temminck professed himself to have been previously unacquainted with it. In the absence, therefore, of further particulars from that gentleman, Major Smith is inclined to suspect that M. T.'s inedited species may be, in fact, the F. macraurus of Prince Maximilian, mentioned and figured in this work, a specimen of which the Major saw at M. Temminck's house. This conjecture, it is true, seems strongly negatived by Dr. Horsfield, who says, expressly, "no doubt remains as to the identity of the subjects from which the description was made," that is of M. Temminck's inedited species, and that of Doctor Horsfield.

Major Smith inclines, also, to think either that the specimens of Sir Stamford Raffles and of Doctor Horsfield were small, or that they belong to a small variety, if not a separate species from nebulosus. The latter, he says diflfers from the former in bulk, in colour, and in the marks on the head, no account being given of the zigzag between the eyes, which distinguished his specimen of F. nebulosa, a peculiarity, we must observe, which is noticed in Hewitt's drawing, before-mentioned, but not in that made by Mr. Landseer. In bulk, he was, it seems, full as large as the great Jaguar, consequently, not quite equal to the Bengal Tiger. With respect to the habitat, the F. nebulosa was said to have been brought from Canton; but it is true that an animal, said to have come from China, may very well have, in fact, been brought from Sumatra or Borneo, both being in the line of route of ships from China homeward.

The editor, presuming the identity of the species, and in deference both to Doctor Horsfield and M. Temminck, would most willingly have cancelled the name of F. nebulosa, and have substituted for it that of F. macrocelis. Some slight uncertainty, however, still remaining, as to the identity of the species described in the text, with that of Doctor Horsfield, particularly in reference to colour, and of both with that of M. Temminck, there would, therefore, be an impropriety in doing it, were there no other objection. But should the identity of the three be clearly proved, it is obvious, that though the first detailed description of it is due to Dr. Horsfield and Sir Stamford Raffles, the first notice and liberal communication of its figure to zoologists long before, both here and on the continent, is attributable to Major Smith. It would, therefore, be a slight, and an injustice done to him, to cancel the name he had adopted, and with it the memorial of his first knowledge and drawing of the animal.

The editor takes the present opportunity of observing, that no small inconvenience presents itself in the progress of this work, in relation to the several new or uncertain species which may be noticed, and for which, however unwilling, he is in some degree obliged to coin names, while inedited figures of the same may already exist in the portfolios of zoologists, to which some other name may have been appropriated. ]

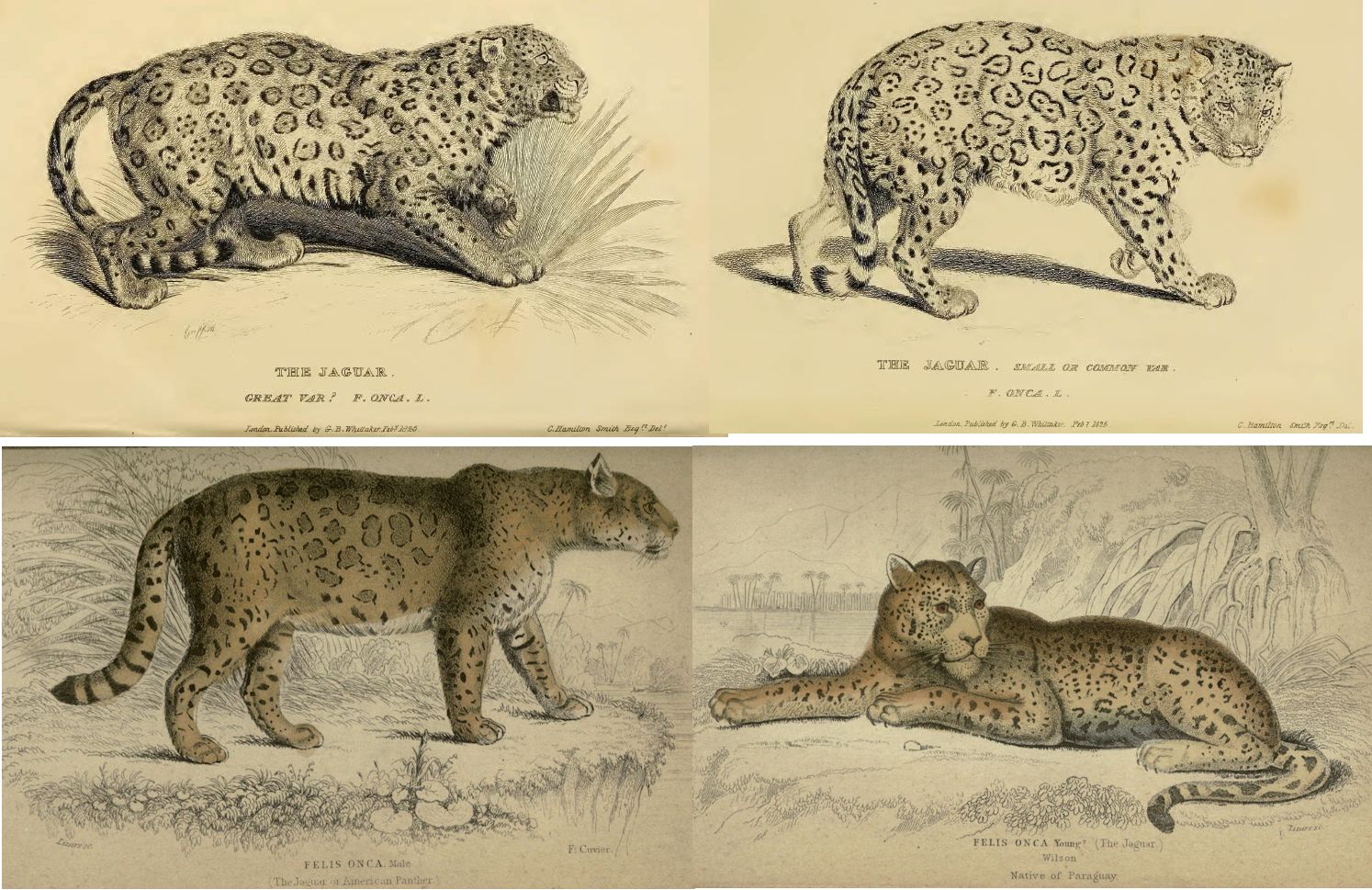

The Jaguar is so named in Brazil. The Portuguese have called it Onca, which Linnaeus adopted as its specific name. It is peculiar to America, and is sometimes called the Tiger of that continent. In size and powers, indeed, it is but little inferior to that formidable beast. The open circles of black, with a central dot, form a strong specific character. The marks, however, differ much in different individuals, nor do the two sides of the same animal always agree. Some inhabitants of South America describe two varieties, corresponding in colour and general appearance, but one of them stands higher than the other, has the forelegs smaller, a fur not quite so bright, and a more gentle disposition. Azara says, it is called Pope, but he thinks they are but one; but Major C. H. Smith, whose long residence in America afforded him ample opportunity of inquiry, satisfied himself there were two distinct varieties of the Jaguar, differing principally in dimensions.

The opposite figure is from his accurate pencil, from a specimen recently killed in America. The type was, as he believes, of the great Jaguar, which was shot in the act of devouring a Peccary, in the woods of Surinam; it measured two feet ten inches in height at the shoulder, but, from its compact and heavy make, it appeared larger than it was in reality. The spots do not strictly agree with what either the Baron or M. Lichtenstein have fixed as criteria; and Major Smith doubts whether any skin of this variety (presuming it to be the Pope or large Jaguar) has ever come under the observation of those indefatigable and accurate observers. The line of lengthened spots on the back was not quite full, and it seems probable, when they are so, that it arises from nonage. The marks on the sides are very irregular, and indefinable; the eyes were small and sunken; the whiskers very long; and the whole character that of an aged animal. It was a male. The portrait is extremely like that given by Azara, in his Travels, particularly as to the make of the animal.

Our figure of the small Jaguar is also from a drawing of Major Smith taken in America. It was a male, two feet two inches in height. Its general colour was paler and more ashy than the large variety, with five large distinct rows of annulated spots on the sides. It was excessively fierce and untameable.

The Jaguar is very like the Panther or Leopard of the Old World, but the spots or rings of the former are larger and more oblong, particularly down the back, and those near the dorsal line have a central black dot, which is never seen in the Panther or Leopard; the head is rounder; the animal altogether stouter and stronger; and the tail never reaches farther than to the ground, which last is, perhaps, the most obvious difference between them.

On the whole, we are inclined to conclude that no accurate description has hitherto been given of the large variety of the Jaguar; or otherwise, that the individuals of this species are so subject to vary, as to render any specific character inconclusive.

There is also a black variety* found in the forests on the frontiers of Brazil, which has the same spots and marks as the others, on a ground of a somewhat browner black; so that they are visible only on close examination, and by viewing the skin when inclining at a certain angle from the direction of the light. This appears to be the Felis Discolor of Gmelin, the Couguar ** of Buffon, and the Black Tiger of Shaw; although the figure given by Buffon does not correspond with it, inasmuch as the under part is white. The black variety, however, is extremely rare. One is also mentioned by Azara, perfectly white, with the spots indicated by a more opaque appearance; but this peculiarity was possibly the eflfect of albinism.

[* It is extremely difficult to say what is a variety, and what a distinct species. The Black Jaguar is, probably, only a variety; but as it is not found in the parts where the Common Jaguar abounds, it may be thence presumed, that they are distinct. ]

[** Major Smith thinks this is distinct. See p. 473. ]

The Jaguars are solitary animals, or are met with only in pairs; they inhabit thick forests, especially in the neighbourhood of great rivers; and if they be driven by their wants to seek for sustenance in the cultivated country, they generally do so by night. It is said they will stand in the water, out of the stream, and drop their saliva, which, floating on the surface, draws the fish after it within their reach, when they seize them with the paw, and throw them on shore for food. They will attack Cows, and even Bulls of four years old, but Horses seem to be their favourite prey. They destroy the larger animals by leaping on their back; and placing one paw on the head, and another on the muzzle, they contrive to break the neck of their victim in a moment. Having thus deprived it of life, they will drag the carcass, by means of their teeth, a very considerable distance, to their retreat, from which their great strength may, in some measure, be estimated.

The Jaguar is hunted with a number of Dogs, which, although they have no chance of destroying it themselves, drive the animal into a tree, provided it can find one a little inclining, or else into some hole. In the first case, the hunters kill it with fire-arms or lances; and in the second, some of the natives are occasionally found hardy enough to approach it with the left arm covered with a sheepskin, and to spear it with the other; a temerity which is frequently followed with fatal consequences to the hunter. The traveller, who is unfortunate enough to meet this formidable beast, especially if it be after sunset, has but little time for consideration. Should it be urged to attack by the cravings of appetite, it is not any noise, or a fire-brand, that will save him. Scarcely any thing but the celerity of a musket-ball will anticipate its murderous purpose. The aim must be quick and steady; and life or death depends on the result. Many parts of South America which were once grievously pestered with Jaguars, are now almost freed from them, or are only occasionally troubled with their destructive incursions.

D'Azara was once informed, that a Jaguar had attacked a Horse near the place where he was. He ran to the- spot, and found that the Horse was killed, and part of his breast devoured; and that the Jaguar, having probably been disturbed, had fled. He then caused the body of the Horse to be drawn within musket-shot of a tree, in which he intended to pass the night, anticipating that the Jaguar would return in the course of it to its victim: but while he was gone to prepare for his adventure, the animal returned from the opposite side of a large and deep river, and having seized the Horse with its teeth, drew it for about sixty paces to the water, swam across with its prey, and then drew it into a neighbouring wood, in sight the whole time of the person who was left by D'Azara concealed, to observe what might happen before his return.

The husbandmen frequently fasten two Horses together while grazing; and it is confidently stated, that the Jaguar will sometimes kill one, and in spite of the exertions of the survivor, draw them both into the wood. This is a performance Molina also attributes to the Puma. It may be reconciled by supposing, that the extreme terror of the surviving Horse paralyzes its efforts.

Generally speaking, particularly during day, the Jaguar will not attack a man; but if it be pressed by hunger, or have previously tasted human flesh, its appetite will overcome its fears; and during the residence of d'Azara in Paraguay, no less than six men were destroyed by this formidable beast, two of whom were at the time before a large fire.

The central spot and short tail of the Jaguar will, with but little observation, soon enable any one to distinguish that transatlantic species from those of the old world, however confused, to which it is nearly allied, and to which we shall now proceed.

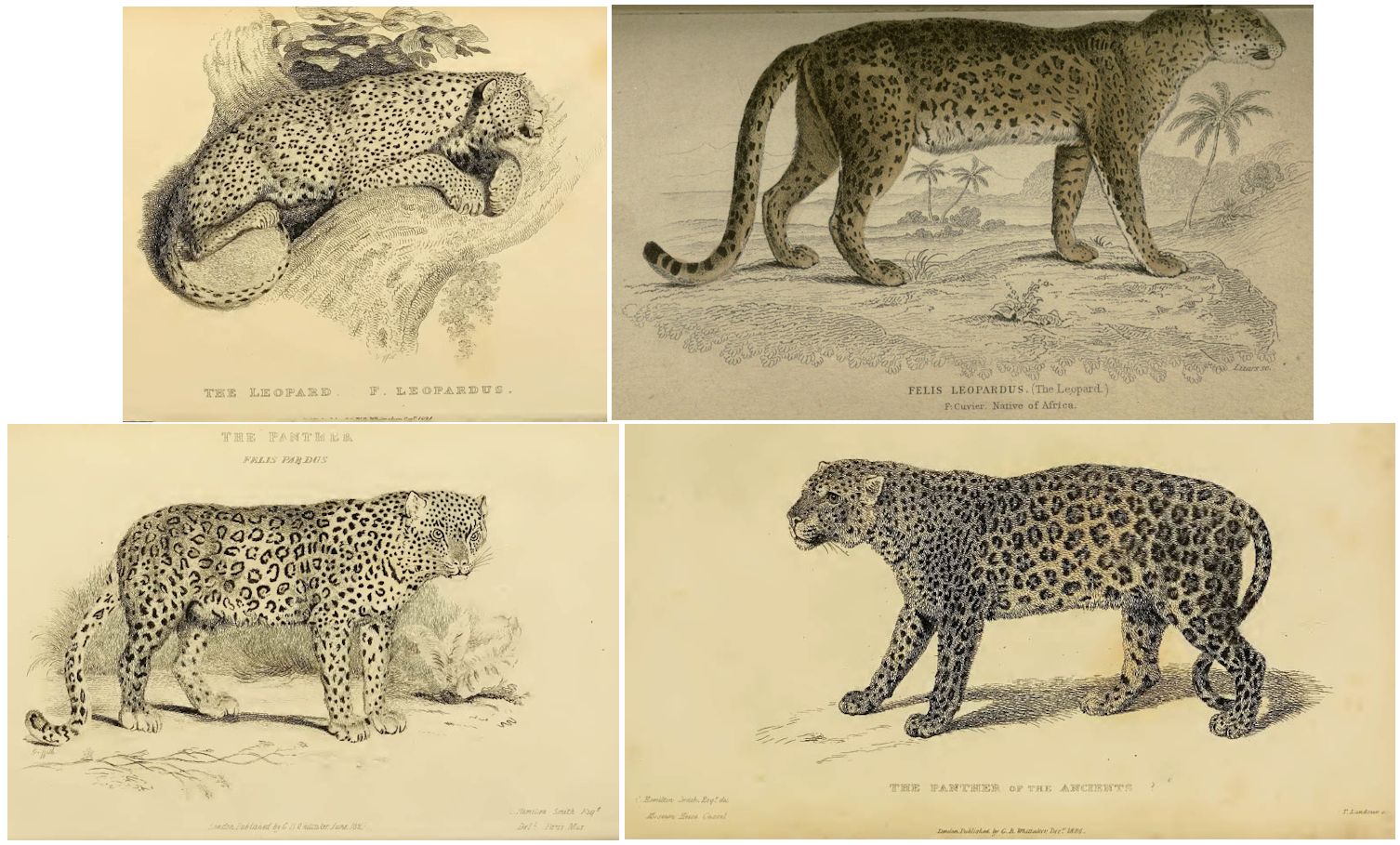

We shall treat of the Panther and the Leopoard conjointly, necessarily so indeed, as the distinctness of the two on the one hand, or the identity of both subject only to variety on the other, seems still in some degree problematical.

The history, says our author, in his Ossemens Fossiles, of the great Cats with round spots of the Old World, is more difficult to elucidate than that of the Jaguar, on account of their mutual resemblance, and of the vague manner in which authors have spoken of them. The Greeks knew one of these from the time of Homer, which they named Pardalis, as Menelaus is said in the Iliad, to have covered himself with the spotted skin of this animal. This they compared, on account of its strength and its cruelty to the Lion, and represented as having its skin varied with spots. Its name even was synonymous with spotted. The Greek translators of the Scriptures used the name Pardalis, as synonymous with Namer, which word, with a slight modification, signifies the Panther, at present, among the Arabians.

The name Pardalis gave place among the Romans to those of Panthera and Varia. These are the words they used during the two first ages, whenever they had occasion to translate the Greek passages which mentioned the Pardalis, or when they themselves mentioned this animal. They sometimes used the word Pardus, either for Pardalis, or for Namer. Pliny even says, that Pardus signified the male of Panthera, or Varia. So reciprocally the Greeks translated Panthera by the word Pardalis. The word Panthera, although of Greek root, did not then preserve the sense of the word Panther, which is constantly marked as different from Pardalis, and by Oppian is said to be small and of little courage. The Romans, nevertheless, sometimes employed it to translate the word Panther, and the Greeks of the lower empire, induced by the resemblance of the names, have probably attributed to the Panther some of the characters which they found among the Romans, on the Panthera.

Bocchart, without knowing these animals himself, has collected and compared with much sagacity everything that the ancients and the orientalists have said about them. He endeavours to clear up these apparent contradictions by a passage in which Oppian characterizes two species of Pardalis, the great with a shorter tail than the less. It is to this smaller species that Bocchart would apply the word Panther. But there are found in the country known to the ancients, two animals with spotted skins; the common Panther of naturalists, and another animal, which, after Daubenton, is named the Guepard, (the Hunting Leopard.)

The Arabian authors have there also known and distinguished two of these animals; the first under the name of Nemer, the other under that of Fehd, and although Bocchart considers the Fehd to be the Lynx, " I rather incline to think," says the Baron, " it is the Hunting Leopard." The Guepard, then, would be the Panther, and there is nothing stated by the Greeks repugnant to this idea. Sometimes they associate it with the great animals, sometimes with the small, which seems to imply that it was of middling stature. Its young were born blind, says Aristotle; it inhabited Africa with the Thos, according to Herodotus; its skin was spotted, and its natural disposition tameable, as we are informed by Eustathius. The two last traits appear inapplicable to any other species than that secondly indicated by the Arabians: it is true, they are silent on the subject of its being employed in hunting, but this is very natural; if, as Eldemiri informs us, the first person who so employed them was Chalib, son of Wail.

As to the word Leopardus, its usage is much more recent, and there is no proof that it indicated a particular species. It is met with only in the authors of the fourth age, and was introduced by the fable of the intercourse between the Lioness and the Pardalis, and by degrees was applied to the Pardalis itself; for, when Vopiscus says, that Probus, when on occasion of the German triumph, he exhibited one hundred Leopards from Lybia, and one hundred from Syria, he could not, doubtless, have meant to say, that they were the produce of such an unnatural intercourse. Thus abstracting for a moment the Lynx, the Greeks and Romans appear to have known but two species of these spotted animals, notwithstanding the opportunities, particularly of the latter, of becoming acquainted with them.

We know at present of Africa but the two species of the ancients, the Panther and Leopard, ordinarily understood, and the Hunting Leopard, (Felis jubata.) The Leopard of modern naturalists, according to our latest researches, comes only from the parts of India the least known by the ancients.

Thus far, in effect, the Baron, with his usual learning and research: to which we shall subjoin a few observations. Pliny tells us, that in his time the words Variae and Pardi were applied to all this family; the former to distinguish the females, and the latter the males: and in a previous passage he observes, that these and the Tiger are almost the only spotted or striped beasts, the rest being uniform in colour, though it varies in the different species. Our author has noticed Pliny's observations, but it may be as well to refer to the passage more particularly, and by the whole context of the quotation from this writer subjoined, it appears probable, that the moderns have been incorrect in applying the word Pardus specifically, as it was originally used only to denote a sexual distinction in the whole genus.

" Panthera et Tigris macularum varietate prope solae bestiarum spectantur, casteris unus ac suus cujusque generis color est leonum, tantum in Syria niger. Pantherus in candido breves macularum oculi. Ferunt odore earum mire solicitari quadrupedes cunctas, sed capitis torvitate terreri. Quamobrem occultato eo, reliquas dulcedine invitatas corripiunt. Sunt qui tradunt in armo iis similse lunae esse maculam, crescentes in orbes, et cavantem pari modo cornua. Nunc varias, et pardos, qui mares sunt, appellant in eo omni genere, creberrimo in Africa Syriaque. Quidam ab iis pantheras solo candore discernunt, nee adhuc aliam differentiam inveni." Plinii Nat. Hist. lib. x.

In another passage mention is made of the Pardi, Pantherae, Leones, et similia. Now, unless Pardi and Pantherae were applied to the two sexes of the Spotted Cats, they could not have been synonymous, as the moderns have made them.

If we turn to modern zoologists prior to the time of our author, we shall find that they have fallen into so many certain errors in describing these species as distinct, that the probability of their identity is rather strengthened by applying to their authority on this subject. To select a few instances.

Linnaeus gives as the specific characters of the Panther, "Felis, Cauda elongata, corpore maculis superioribus orbiculatis, inferioribus virgatis." With a long tail, the upper part of the body covered with orbicular spots, the lower part with stripes. This short description, it has been well observed, is inapplicable to any known species of the genus. Perhaps it is nearer to the Servals than to any other. His characters of the Leopard are, " Felis, cauda mediocri, corpora fulvo, maculis subcoadunatis nigris." "With a moderate tail, a fulvous body covered with subcontiguous black spots." Dr. Shaw observes: "In the twelfth edition of the Systema Naturae, the Panther and Leopard seem to be confounded by Linnaeus himself, who appears to have considered them as the same species, under the name of Pardus." And if we consider the description given to the Panther to be irrelevant and factitious, it follows, that Linnaeus has only described one species of the large Spotted Cats found in Asia and Africa, which must include the Variae, and Pardi, and Leopardi, of the Romans.

Buffon, the brilliancy of whose work has blinded mankind to his imperfections, imbibed an idea which he never seems to have lost sight of, that the American animals were degenerate, and less in size than the species of the old world belonging to the same order: hence, probably, he was led into a misunderstanding, or too willingly confirmed in error on this subject. He has mistaken the Jaguar, which he describes from an Ocelot; and refers the former animal, because, probably, it was a large species to the Panther of the ancients, transposing his figures accordingly. The furriers and exhibiters of wild beasts have imbibed this error; and the Jaguar of America has altogether usurped the name of Panther from the species of the Old World, to which it was originally applied.

Pennant's description of the Panther so nearly accords with the Jaguar of America, both in person and disposition, that there scarcely seems a doubt of this animal's being the type whence his description was taken.

Dr. Shaw states, that the Leopard is best distinguished from the Panther by its paler yellow colour, and that a true distinctive mark between them is by no means easy to communicate, either by description, or even by figure; but he adds, the Leopard is considerably the smaller of the two. He therefore makes the principal difference to consist in size and colour.

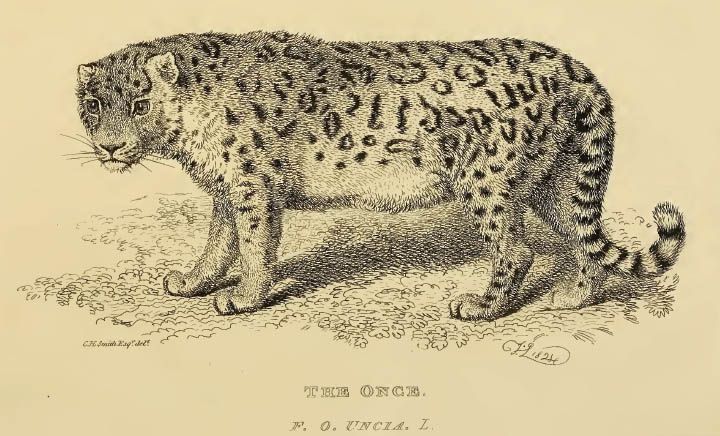

Pliny says further: " Quidam ab iis Pantheras solo candor e discernunt, nee adhuc aliam differentiam inveni." It is possible, however, if the F. Uncia be really distinct, that Pliny refers to that species. Major Smith believes him to be distinct, and describes him as whitish-gray, faintly tinted with buff. "He may," says the Major, “have been a Syrian and Armenian animal, and I believe him now a resident of the mountains of Northern Persia.” We refer to our figure of the specimen formerly in the Tower. It seems probable, that all those which come from Asia are much brighter in colour than those from Africa, and that the females in general have more white about them than the other sex. Mr. Cross, who has had opportunities of inspecting probably some hundreds of specimens, insists, that he has never observed any specific difference between those brought from Asia and Africa among themselves, except that the Asiatic are generally larger and brighter; and except, also, that some individuals constantly carry their long tail curved outwards, and others inwards, the latter of which they call ring-tailed Leopards, It seems probable, therefore, that Dr. Shaw's leading specific distinctions of size and colour, apply rather to the Asiatic and African varieties, than to distinct species found in both those continents. The figures, however, in the General Zoology, neither illustrate the author's position on this subject, nor throw any light on the question; for they are merely copied from Buffon, and that which is called the Panther is properly referable to the Jaguar.