1800s- 1900s - MEDICAL CARE OF CATS

In 1870, the Honourable Lady Cust produced a book called "The Cat" in which she perceptively wrote "In the present day, a love for cats appears chiefly permitted to 'elderly spinsters,' and is often even ridiculed". She went on to say that she was ridiculed by learned members of the Zoological Society for asserting that grass was a necessity for cats. Not all of her advice was so sensible. For instance, she recommended slitting the ear as a cure for fits. Her remedy for vomiting went"Stop it as soon as you can by giving half a teaspoon of melted beef marrow, free from skin; one dose is generally sufficient, but if not, another half-teaspoonful may be given in half an hour. To allay vomiting from irritation I have never seen this remedy fail in human or animal subject." Lady Cust described cat-pox as "a disease like chicken-pox in human subjects will sometimes appear in spring and autumn, chiefly on the throat and head." She recommended a cooling diet, grass and an ointment made of lard and brimstone.

Some of the earliest feline remedies included eating a whole kipper (including bones) to remedy constipation; and eating crushed clay pipes to remedy diarrhoea. A regular dose of fish oil kept cats regular and supposedly protected them against worms. According to Dr Gordon Stables in 1872, if a cat should have a convulsion, a smelling-salts bottle should be held to his nostrils, or a pinch of dry snuff and, if this does no good, 'Pussy must be bled'. In 1901, the only documented feline ailments were colds, pleurisy, distemper, mange, worms, fits, diarrhoea and constipation. In 1901, "How to Keep Your Cat in Health" was written by "Two Friends of the Race" and contained such advice as "If your cat should be taken ill, have as little as possible to do with drugs, unless it be in the homeopathic form". Cats with colds were dosed with a tonic of tincture of arsenicum in a spoonful of milk. The same tonic was given for distemper, along with a mixture of eggs, cream and brandy. Tincture of arsenicum was recommended for mange. The symptoms of mange were to be treated with sulphur ointment, carbolic acid ointment, green iodide of mercury ointment and acid sulphurous lotion. Arsenic was used as a tonic and an antiseptic; prussic acid was used as an anti-spasmodic and for pain relief; lead was used as an astringent and a sedative.

Pedigree cats were believed prone to dyspepsia and the "Two Friends" wrote "[Dyspepsia] is more often met with in highly-bred and notably show specimens, when a too-fixed and stimulating system of feeding is adopted". At the time, pedigree cats were not usually fed horse meat (fed to household cats) but lean chopped mutton. To set a broken bone, a papier mache cast was made. Brown paper was soaked in boiling water, the excess water was squeezed out and the papier mache was moulded onto the broken limb. Strips of calico fabric or linen were laid over this to hold the cast in place. This simple cast was effective.

One of the first small animal veterinary books was "Diseases Of Dogs And Cats And Their Treatment" by Anonymous in 1893. The anonymous veterinarian had good reason to stay anonymous - some of his opinions were controversial at the time and he made cutting about quacks and about fellow vets. In 1895 came Rush Shippen Huidekoper's "The Cat: A Guide To The Classification And Varieties Of Cats And A Short Treatise Upon Their Care, Management and Diseases" published in New York . This described all the known members of the cat family and was illustrated with scientific drawings and with drawings of cat breeds reproduced from Harrison Weir's 1889 book "Our Cats And All About Them"

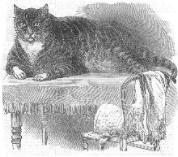

In 1901, J. Woodroffe Hill, Fellow of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, brought out "The Diseases of the Cat". Some of Woodroffe Hill's opinions were the exact opposite of the anonymous vet almost 10 years earlier. His book was illustrated with photos of his clients' pedigree and non-pedigree cats. Like those before him, he described ailments in great detail, with none of the investigate methods now taken for granted diagnosis was based entirely on observation. Equally, none of the modern drugs were then available and the treatments he described now seem hit-or-miss or primitive to say the least.

Before the advent of vaccination, "Nasal Catarrh" or "Cold in the Head" was very common. "The cat becomes languid, is less inclined to play or hunt, and may show a varying degree of inappetance. A thin mucous discharge issues from the nostrils, which the cat endeavours the quicker to expel by constant sneezing. There is also a watery discharge from the eyes, a warm, dry nose, and usually attended with a normal or slightly elevated temperature." The disease (which is now called an upper respiratory tract infection) was variously considered to be due to damp, cold or contagion or to a sedentary or confined life.

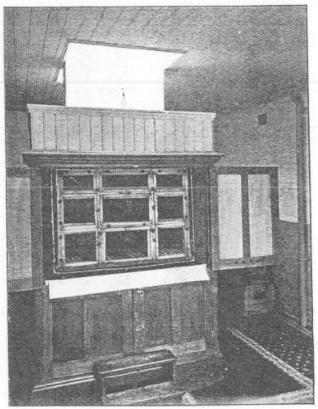

Suggested treatment for a mild case included keep the cat warm and treating it with camphor water and spirits of ether nitrate. More severe cases required steaming of the cat's head with an infusion of poppy heads or 2% Jeyes fluid. "For the purpose of administering vapours, it is suggested that it may be expedient to place the cat on an old chair with perforated seat, beneath which is placed the steam kettle, the whole being surrounded by a rug." Eucalyptus oil was used as an antiseptic, but was to be applied to the cat's forehead, because if it was dropped into his bed, he would probably refuse to sleep in it. Some early vets recommended a liberal, stimulating diet, but others advised a diet of warm milk.

Far more sever was Feline Distemper: frequent shivering fits, with sneezing, coughing, retching and vomiting, watery discharge from the eyes and nose, the breathing laboured and snuffly Distemper might then be followed by any of the diseases of the respiratory system. Treatment was the same as for nasal catarrh, with the addition of twenty or thirty drops of whisky or brandy. It was known to be very contagious, and isolation of infected cats was advised. Some early cat doctors mentioned the extensive and tragic epidemics of distemper in the fifteenth century. There were already some crude canine distemper vaccines available (though they were more dangerous than disease itself) hence one early vet suggested that his inoculation system for dogs should also be used for cats, but failed to give further information on this! For the most part, distemper was the more severe form of cat flu, though some early descriptions of distemper included symptoms associated with enteritis.

A disease recognisable as Feline Infectious Enteritis was described: "A special form of inflammation of the stomach and bowel combined frequently attacks cats, and has lately been somewhat prevalent, assuming the appearance of an epidemic and being undoubtedly infectious... Symptoms in many respects simulate typhoid. The disease is accompanied with great prostration, offensive diarrhoea, often of a dirty green colour, or resembling pea soup. There is increased pulse, injection of the mucus membranes, furred tongue - especially dark at the edges - high temperature, abdominal enlargement and tenderness, disinclination to move and in advanced cases the animal lies stretched out on the side. In some cases there is frequent vomiting and intense thirst. Before death the animal may become comatose or delirious."

Treatment consisted of ½ grain of napthol in salad, hot fomentations or poultices to the abdomen, doses of sulphate of copper and opium (then easily available), starch enemas, fluid, mucilaginous food and iced milk. Strict cleanliness and disinfection was to be rigidly observed. Should the cat survive, it could expect to convalesce on "a diet of Eastons syrup and cod-liver-oil, with the yolk of an egg and cream beaten up, and by degrees a little shredded or scraped raw meat can be introduced; but the greatest caution should be exercised in giving solid food, as the gastric and intestinal membrane remains in an extremely sensitive condition for a considerable period."

Early anaesthetics were unsophisticated and risky: either chloroform or chloral hydrate and largely reserved for euthanasia. Feline surgery was mostly restricted to neutering (spaying was available, although not common), repairing wounds and fractures and alleviating obstructions of the bowel.

Obstructions of the gullet, stomach or intestine were apparently common. Common causes were listed as needles, buttons, bones, hairballs (more than one good breeding cat died after swallowing a needle) and dire consequences were predicted. More than one author suggested the use of a probang - a "sponge tied onto a cleft stick, flexible cane or piece of whalebone" which was used to force an obstruction in the gullet into the stomach, but does not mention anaesthesia for this procedure. This treatment could be worse than the disease! If the gullet was damaged (either by the original obstruction or by the treatment) the animal should be "starved if necessary for a week or two, while giving nutritious enemas". If the obstruction was in the stomach or intestines, a dietary lubricant such as coarse oatmeal and sardine oil was recommended to help it pass through. One early book mentioned the possibility of surgery and the considerable danger of peritonitis (due to poor antiseptics and no antibiotics). Such surgery should only be risked by an expert abdominal surgeon.

Fractures were usually splinted using wood, pasteboard or leather. Bandages soaked in gum, starch or plaster of paris might also be used. Warm pitch was used to prevent the splint from slipping. Quite complicated fractures could be treated and many cats made an excellent recovery though a few complicated or infected cases required amputation.

In the days of hearth fires, burns were common. "Puss, with its love for the fireside more often gets burnt than scalded, and very deep burns sometimes occur when a large cinder falls on the fur, which more readily ignites than the coat of a dog. A cat aflame is a dangerous creature, for it may rush to any part of the house, and set fire to other materials. This disaster is treated by the application of equal parts of linseed oil and lime water, covered over with cotton wool... poulticed and warm emollient fomentations may be required." If a large amount of skin was lost to a burn or scald, the damaged area could be removed entirely and the skin drawn together: "When... a considerable blemish follows the healing process. that portion of the skin creating the eyesore... may by careful surgery be removed, and the union of the edges of the surrounding skin so neatly affected as to disguise the fact that puss is so much integument short."

Common home treatments:

"In well-broken cats fond of their owners the administration of medicine is sometimes an easy matter but again in equally well-broken and affectionate animals it is an excessively difficult one." Early authors all advised persuasion as better than force (the same is true today). However when force or restraint became necessary, there were no sedatives available and physical restraint was necessary. "Take the cat by the loose skin of the neck with one hand and by the skin of the pelvis with the other and place it on a table pressing down until the breast-bone in front and under surface of the pelvis behind are held firmly against the table." If the cat had to be restrained for a longer period, it might be wrapped in a sack of cloth, leather or indiarubber . At home, it could expect to be restrained in a towel or piece of sheet.

From 1898 to December 1899, “Fur & Feather” had competition in the form of “The Show Reporter” published by George A Townsend in Leeds. One of the magazine’s regular feline correspondents, right from the first issue, was Miss H Row, from Crediton, Devon. Miss Row’s column was called “The Cattery” and ranged from serious to light-hearted, from show news to chit-chat. Here are a couple of items are from Miss Row’s column in the final issue (December 21st,1899.)

All questions relating to Cats will be answered weekly by Miss H. Row Crediton, Devon and under the above heading all correspondence on the subject is dealt with. Cat Fanciers are invited to send us any item of news concerning their stock likely to be of interest to their fellow fanciers. Please send all letters intended for this column to the above address, with “Cattery’ written in the top left-hand corner of the envelope, and the writing on one side of the paper only.

According to my promise. I am now going to tell the story of the clever cat; it was told to me by the cats own mistress, who assured me that it was quite true. The cat, just an ordinary one, with no particular beauty to speak of, had the misfortune to break her leg. Miss H. (pussy’s mistress), got the parish nurse to assist her in bandaging the leg, which was done with splints, and made a very neat job of; pussy was goodness itself for keeping the bandage, etc. on, and all went well. One day the nurse said, “Tomorrow morning we shall be able to take off the splints and bandage.” Next morning pussy went out for a short walk, returning about half an-hour after with its leg free from any encumbrance whatever. She had heard what nurse said about taking off the bandage next day, so thinking to save trouble, she had gone out and taken them off herself. Strange to say she had never tried to interfere with them before in any way. I asked Miss H. whether pussy brought back the splints, etc. to be useful another time, but my little bit of satire was thrown away, for it was not understood. This same cat was expecting a family, and was looking about for a bed to put them into. One day she spied a boxful of blankets and thought to herself that nothing could be softer or more comfortable for her babies, so in she went. But she saw that the two top blankets, so neatly folded in the box, were quite clean, lust returned from the laundress in fact, whilst the pair under were to be sent the next week; here again pussy’s cleverness showed itself, for she actually took off the clean ones from the top and made her bed upon tie soiled ones underneath.

Since writing last, I have been called upon to bandage the broken (or dislocated) leg of the cat I mentioned, having gone to see it accompanied by the vet. The bandage he put on stayed there something under three hours Miss C. told me. I felt sure that I could make one that would remain in its place, if the cat were encouraged to stay in by the fire, and made happy and comfortable there. I will try and give a description of the bandage, as it may be of help to some young fancier, who like Miss C may be at her wits end to keep a bandage on. I took a long strip of calico, about six inches wide and cut a slit going lengthways, large enough to go over the cat’s head. This I put on round his neck, letting one end go along the cat’s leg, straight down, cutting it narrower where it went down the leg. The other end I left about seven or eight inches, perhaps a little more, that would greatly depend on the size of the cat, then I took a narrower bandage about three inches in width, and began to wind round the leg, commencing at the foot just above the first joint and bandaging in the ordinary way, as high as it was possible. Then taking the strip that I had laid along the cat’s leg lengthways, I turned it up and laid it alongside outside the bandage, straight up again towards the shoulder, and passing it across the back, I passed it under the other arm and back again to meet the broad one round the neck, I then put a stitch to every round of the bandage on the leg, sewing it to the straight strips and thus preventing the rounds of the bandage from separating or slipping off as it had done before. Four days after it was still on and pussy using his leg, awkwardly of course, but that he’s sure to do. The Vet and I are both of the same opinion that a small bone of the leg is broken, whether or not it will unite is another matter, we have done our best.

Miss Florence Dresser writes: “I am sorry to have to tell you that since I wrote last, my beautiful “Carrots” died of distemper and worms. So has “Watch Hazel” (the Manx with the sore nose). She got vhc [very highly commended] and 1st in team at the Crystal Palace; and so has a little brown tabby by “Bonhaki” ex “Belle Ma hone “. My three kittens by “Bonhaki” had worms dreadfully, but two were fairly strong and one was very weak from distemper. As they got no better and had very sore eyes I thought I had better dose them. I gave the strong ones each of “Rackham ‘s Japanese Worm Balls for Puppies” and the weaker one a third of a ball, but the poor little thing was too weak to recover from the effects. I do not think she could possibly have lived, she was so very emaciated. The little silver tabby Tom and his other brown sister are as lively as possible, they eat tremendously and are so nice and fat now. By the way, have you ever tried “Rackham’s Katalepra for Excema”? I have found it marvellous in its effects on both cats and dogs. We mix it with Vaseline (two parts Vaseline and one part Rackham’s Katalepra) and put it on warm and melted; it heals so fast and clearly. I enclose a photo of a Griffon, which is better than describing it; the two Griffons in the photo weigh 4lb 12oz and 5lb 8oz respectively.

Miss Dresser has a tortoiseshell and white cat, which I believe I mentioned a week or so ago as having been fostered by one of her Mother’s Griffons. On asking Miss Dresser what a Griffon was like, she very kindly sent me a photo of her Mother’s, a male and a female. Very curious little creatures they are, with something between a cat’s and a dog’s face, and long hair hanging over their faces and bodies. They must be sweet little pets.

H.Row.

I am sure we all sympathise with Miss Florence Dresser on the loss of her valuable cats. None but those who love their pets can know what such a loss means, or the worry and anxiety the illnesses which precede death give to the owner.

From the 1880s, it was generally believed that cats were becoming weaker than their predecessors. This was blamed in part on the breeding (or inbreeding) of delicate pedigree cats, especially imported varieties such as Angoras, which supposedly brought disease with them. Many of the home remedies used by owners contributed to early death of the cats they were trying to make well. The less harmful early remedies included eating a whole kipper (including bones) to remedy constipation; or dosing the cat with crushed clay pipes to remedy diarrhoea. A regular dose of fish oil kept cats regular and was believed to protect them against worms. In 1901, the only documented feline ailments were colds, pleurisy, distemper, mange, worms, fits, diarrhoea and constipation.

In 1901, "How to Keep Your Cat in Health" written by "Two Friends of the Race" contained such advice as "If your cat should be taken ill, have as little as possible to do with drugs, unless it be in the homeopathic form". Cats with colds could be given a tonic of tincture of arsenicum in a spoonful of milk. The same treatment was advised for other ailments such as distemper, along with a mixture of eggs, cream and brandy. Tincture of arsenicum could also be given for mange. The symptoms of mange were to be treated with sulphur ointment, carbolic acid ointment, green iodide of mercury ointment and acid sulphurous lotion. Arsenic was used as both a tonic and an antiseptic. Prussic acid was used as an anti-spasmodic and also for pain relief. Lead was used as an astringent and also a sedative. Most of these remedies are actually poisonous.

To set a broken bone, a papier mache cast was made. Brown paper was soaked in boiling water, the excess water was squeezed out and the papier mache was moulded onto the broken limb. Strips of calico fabric or linen were laid over this to hold the cast in place. This treatment (immobilisation using a cast) is familiar and effective, even if the materials are not.

The most serious feline disease was distemper, now called Feline Infectious Enteritis (panleucopaenia) though some early descriptions confuse it with cat flu (calicivirus etc). It was also known as "show fever" since cats returning from shows often developed it as a result of mixing with cats carrying the disease (the "mother and kitten" classes at early shows were particularly vulnerable). "Show fever" was sometimes blamed on a jealous competitor poisoning cats. Another name was "market fever" since kittens or cats purchased from crowded markets often went down with the disease. Whatever the name used, distemper wiped out entire breeding lines, but no-one understood how it was transmitted.

Distemper was believed to be caused by high temperatures or drought and that outbreaks diminished in cooler weather. Cats with symptoms of distemper were treated with a mixture of castor oil and liquid paraffin which supposedly cleared bile. The owner was instructed to dose the cat every three hours with a dessertspoon of egg white mixed with ten drops of brandy to settle the stomach.

Although distemper has been around since the 15th Century, with major outbreaks in Britain and Europe in 1796 and another in the USA in 1803, the anonymous 1893 "A Veterinary Surgeon" blamed longhaired cats of spreading the disease (they were considered weak and carriers of various diseases). He wrote, "Cats did not formerly suffer from distemper when wild in back gardens the noble tabby ran, but since the long-haired varieties have been largely bred, and the meanest-looking cat may give birth to a long-haired kitten through some casual acquaintance, distemper has become quite common, and many lovely kittens succumb to it despite the most careful nursing and attention."

In 1900, diarrhoea was treated by dissolving I oz of fresh mutton suet in a quarter pint of warm milk. A teaspoon of the mixture was given every two hours. For sick cats not up to taking solids, a preparation of beef called "Somatose" was recommended by Mrs Hardy, breeder of blue Persians (1903). Somatose came in 1 oz and 2 oz tins and was a fine soluble powder. This could be made into a beef tea and, unlike beef essence, the powder could be stored for longer periods of times. The beef tea was made by mixing a teaspoonful with a boiling water and serving when cold. She also recommended "Plasmon" powder for cats and kittens with chronic dyspepsia, diarrhoea or dysentary. Cold Plasmon jelly should be alternated with cold Somatose tea. A cat or kitten with looseness of the bowels should not be given milk in any form. "Salvo's Preventive" was tonic used by breeders of Mrs Hardy's time.

For the braver owner, feline constipation could be treated with an enema of water and glycerine. The other cure for constipation through the ages was a tablespoon of olive oil. Olive oil and cod liver oil (or halibut oil) were cure-alls and preventatives for many years and are still given as supplements today. A suitable treatment for an out-of-condition cat was a mixture of olive oil, milk, cream and salad oil beaten together or, alternatively, sardine oil. A pregnant cat was given a teaspoon of olive oil at least twice a week for the last three weeks. If cod liver oil was not to be had, fried bacon and bacon fat could be given instead.

Cats were generally believed to become off-colour in the spring, losing their appetites, developing foul breath and unkempt coats. A daily dose of cascara laxative tablets supposedly prevented those symptoms from worsening. Failure to treat these symptoms would result in constipation, diarrhoea, runny eyes, running nose and suppurating ears! If untreated, the cat would die from nervous exhaustion, heart failure, enteritis, pneumonia or pleurisy. In all likelihood, the cats were going through a combination of spring moult, hair balls, hormonal changes (they were unneutered) and were picking up external parasites such as fleas and mites. Tomcats were believed prone to summertime skin troubles which could be remedied by a twice weekly dose of olive oil. Female cat sometimes developed skin problems after having kittens; this was blamed on her mating with an out-of-condition tomcat.

Early wormers were toxic to cats and would have killed a good many. In the mid to late 1800s, cats with worms were dosed with turpentine. Turpentine also caused cystitis (inflamed bladder) which could be treated with hot hip baths, linseed poultices between the cat's thighs, warm gruel enemas and opiates (turpentine is toxic and causes kidney damage). It was far safer to prevent worms in the first place and in the early 1900s, a pinch of salt with every meal was supposed to prevent worms. In 1901, regular doses of cod liver oil were considered an excellent antidote to worms.

Despite the vogue for freaks such as "heaviest" or "fattest" cats at shows, obese cats were said to be prone to apoplexy which could be treated by applying leeches to areas from which fur had been clipped or shaved. Dropsy (accumulation of fluid) could be treated by "tapping" i.e. removing the fluid, bandaging the affected area and then dosing the cat with brandy in warm milk as a stimulant. Little was known of dental or oral problems. Mouth or tongue ulcers indicated "internal derangement" and were treated with Milk of Magnesia.

Up until the early 20th century, cats were believed prone to fits, in which case smelling salts were waved under their noses. Fits were believed due to a variety of causes such as eating raw meat, or a female cat having all her kittens taken away (i.e. destroyed) at once. Female cats would supposedly never have fits if they had at least one litter of kittens. Other early treatments for fits were a warm bath and an enema (in the case of female cats whose kittens were removed), or slitting the cat's ears and expelling a few drops of blood. A good many fits were probably caused by the many toxic medications then given to cats.

DISEASES OF CATS, 1893, BY AN ANONYMOUS VETERINARY SURGEON

The following are excerpts from “The Diseases Of Dogs And Cats And Their Treatment, by a Veterinary Surgeon” published in 1893:

“Chronic eczema in cats is not of frequent occurrence, and when it is met with is caused by suppressed sexual desires; caged cats of the fancy varieties, especially females, being the subjects. “

“Ulceration of the cornea is not a frequent result of traumatic or of constitutional ophthalmia, but is a sequel to distemper, and will be again referred to when treating of that malady. Cats of the common breed are not often the subjects of the above, but the fashionable long-haired cats, of which some 500 are exhibited at the Crystal Palace annually, are much more delicate and occasionally troubled with entropium and ectropium, which, in plain English, is turning in or turning out of the eye lashes. “

“Cats and dogs suffer from common colds and from influenza as do human beings. Influenza is most infectious as between one cat and another or from dog to dog, but is it infectious from cat to man? The household cat has been accused of all sorts of things, from witchcraft to the conveyance of diphtheria, but does she convey those influenza colds of which it is often remarked, “When the cat has a cold everybody in the house has one?” That black cats bring luck to a house, diphtheria to the baby, and necromancy to the “wizards who mutter and peep,” we can readily believe, because we were told so when children going to bed, and the notion took root “in the witching hour of night, when churchyards yawn.” Besides coming home ragged and torn, they catch the most frightful colds, and get no sympathy, as do human beings, when their nocturnal follies have laid them by the heels. When a cat sneezes she is promptly turned out of the room, while, if she coughs, everyone thinks she is going to be sick, and her ejectment is even less tenderly performed. Nevertheless, she has her feelings, and if we could read her thoughts, we should find she has but a poor opinion of our intelligence in behaving in such a manner to a creature in need of nursing and extra comfort. The symptoms of a common cold are too well known to need description, and the form of influenza met with in our patients is not the prostrating fever known by the same name in men and horses, but an aggravated cold, a profuse discharge from eyes and nose, accompanied by sneezing, coughing, loss of appetite, and staring coat. Treatment consists in comfortable surroundings, in which to get through three or four days of great discomfort, without again getting wet, or being exposed to the conditions which brought about the disease. “

“Inflammation of the Lungs is more frequent now than in former days, and the probable reason, both in dogs and cats, is that they have been bred for points rather than constitution. Nature exacts a penalty for what is called scientific breeding, though a disregard of constitution would seem to take such breeding out of the realm of science. Dogs are bred from near relations in order to develop certain peculiarities, which fashion declares to be correct to-day, and discards in two or three seasons. All through the fancy stock — the aristocracy of the show-bench — there is a tendency to delicate and feeble constitution. The prize pigeon, bred by careful selection in order to develop particular feathers or colours, becomes scrofulous. The hero of the poultry pen begets pullets which will not lay or sit. The beautiful long-haired cats are frequently sterile, or such bad mothers, their progeny die unless provided with wet nurses. “

“ Animals have acute or chronic bronchitis as with man, and the same fogs and atmospheric conditions that oppress the owner oppress the dog or cat. It was seldom that bronchitis attacked the old English tabby, though he was exposed to the same conditions of bad weather, and was morally no better, than his descendants, but pulmonary diseases are quite common nowadays among the fancy cats so delicately nurtured and bred from Persian, Angora, and other foreign progenitors, and these creatures have in course of time tinctured the blood of the indigenous cat, if we may so speak of animals originally imported from Egypt, but long since acclimatised. Any mean-looking cat may have a kitten with long hair nowadays, and show the gentle blood of the sire in facial expression as well. There is no doubt but what with the improvements brought about by cat shows, and the greater distribution of the long-haired varieties, the cats of this country will be quite changed in a comparatively few years. “

“Rickets among kittens was unknown until the last few years, when the breeding for points and coat among the prettiest, but least robust, has developed a variety of diseases unknown to our fathers as affecting cats. A good old English tabby is so hardy an animal as to have acquired for his tribe the reputation of having nine lives. Anyone who has visited a cat show with his eyes open must have seen how many weak and diseased animals are shown, only to go home and die in a few days.”

“Distemper is, without doubt, the most important disease, or generic term for a number of diseases, with which the dog is afflicted. Cats did not formerly suffer from distemper when wild in back gardens the noble tabby ran, but since the long-haired varieties have been largely bred, and the meanest looking cat may give birth to a long-haired kitten through some casual acquaintance, distemper has become quite common, and many lovely kittens succumb to it despite the most careful nursing and attention. After each cat show at the Crystal Palace or the Brighton Aquarium numbers of kittens go home to die, and until the October, 1892, show at the Crystal Palace, no veterinary surgeon had previously been appointed to inspect them. On this occasion Mr. Harold Leeney rejected some twenty exhibits suffering from well-defined infectious disease. “

“Cats are but very little troubled by their teeth, except in extreme age or at the critical period of cutting the tushes when they are subject, but not nearly so liable, to fits as puppies. In old age the molars get loose, and remain so for a very long time. The patient suffering of the cat fails to attract notice or excite sympathy, and the loose tooth is retained till it falls out, as it were, by its own weight. Notwithstanding the fact that cats are so much more careful in feeding than dogs, they are even more frequently injured by splinters of bone, fishbones, pins and other foreign bodies getting lodged between the teeth or firmly fixed in other parts of the mouth. When a foreign body becomes thus fixed in the mouth of a cat she is first angry, next frightened, then sulky, and finally resigned to her fate. A few ineffectual attempts to dislodge the offender with the paws, a rub or two of the face on the mat, and then she retires to a quiet corner, as is her wont when wounded, to suffer alone. If the accident is not observed at the time, nor the ropes of saliva hanging from the mouth next day, with mouth a little wry and swollen face and anxious look, then these acute symptoms abate, though the bone remains. Nothing is eaten, but the cat waits on; whether supported by hope or a philosophy we cannot understand, . . . a cat will go without eating for weeks, until a splinter or foreign body sloughs out, if it has not been got rid of in any other way. “

FELINE ANAESTHESIA

This note appared in The Gentlewoman, 11th February 1899:

MR. HENRY GRAY, M.R.C.V.S., who is well known as a painstaking investigator into the diseases of cats and dogs, contributes another able paper to The Ladies' Kennel Journal on various methods for rendering the cat insensible to pain. The matter is too technical for treatment here, but cat owners will be much indebted to Mr. Gray for his valuable advice. I agree with him that no person should cause a domestic pet to undergo an operation without it being under the influence of anaesthetics. The law should be put in force against any who cause pain when we have such valuable and effectual means at our hands to prevent suffering. An interesting article on the Manx cat is published.

THE DISEASES OF CATS AND THEIR TREATMENT

Contributed by Henry Gray, MRCVS to Frances Simpson's "The Book of the Cat", 1903. By modern standards, some of the remedies are quite scary; in some cases the "cure" is likely to be as lethal as whatever disease or symptoms the owner is trying to treat.

Note: The term "distemper" refers to a disease characterised by fever, vomiting, diarrhoea, dehydration and, all too often, death. It is often used to denote either/both cat flu (calicivirus) and/or Feline Infectious Enteritis (panleukopaenia), both being infectious and widespread. Often the description tells the modern reader which of these ailments is actually meant in the text. Descriptions of frothy vomit and foul diarrhoea indicate FIE; descriptions of severe respiratory symptoms indicate calicivirus. Some of the treatments, and the amount of milk in the diet, would have induced diarrhoea which would confuse the diagnosis. In recent times, distemper (feline distemper) has come to mean panleukopaenia in the USA (being called FIE in Britain) and, given prompt and intensive treatment, cats can recover.

ADMINISTRATION OF MEDICINE

In the treatment of the diseases of the cat, the correct method of administering whatever medicaments are deemed necessary is a most important consideration. To the uninitiated and timid the task is generally a difficult one, and may, in some cases, appear almost impossible; but with a little practice, aided by courage and determination, the difficulties can nearly always be overcome. The administration of medicine, however, is seldom so easy in the case of the cat as in that of the dog.

Some cats are so gentle that the mouth can easily be opened by means of the index finger and thumb of the left hand acting as a wedge between the jaws. The palm of the hand rests on the top of the head, while the finger and thumb gently but firmly press the cheeks at the angle of the jaws inwards, until they intervene between the finger and thumb of the operator and the posterior teeth of the patient.

The jaws being thus kept open, and the head at the same time raised, the right hand of the operator drops the pill or powder at the back of the mouth between the tongue and palate. This having been accomplished, the right hand is passed under the lower jaw, so as to keep the head raised until the animal swallows, while the left hand is withdrawn from its previous position and the jaws allowed to close, thus facilitating the act of swallowing.

For the administration of liquid medicine it is not necessary to open the mouth The operator grasps the head with his left hand, and taking the spoon in his right he slowly and carefully drops the liquid between the teeth, or into the space between the cheek and teeth, at the angle of the mouth. For the cat, a coffee-spoon is preferable to a tea-spoon, and care must be taken that too much is not poured into the mouth at once. The dose should be administered drop by drop, and time allowed for swallowing.

DISEASES OF THE STOMACH

Vomiting, though a symptom common to many diseases, may be quite natural in some instances, such as over-feeding or during the weaning period, when the mother cat eats a lot of animal food and them brings it home and vomits it up for her young kittens to feed upon [note: this is how dogs feed puppies, cats carry home intact prey!]. The act consists of ejecting the contents of the stomach through the gullet and then out of the mouth.

The causes of vomition are various: worms travelling from the bowel into the stomach, emetics, expectorants, poisons, foreign bodies (as hair, cork, pins, etc); bad or altered food, blood-poisoning, distemper, gastritis, tumours, tuberculosis, jaundice, diseases of the kidneys, etc, may cause it. It may also occur from parasites in the ear, foreign bodies in the mouth, and as a symptom of brain disease, such as meningitis.

Treatment - This depends upon the cause, which should be removed if possible. When due to foreign bodies or altered food, an emetic (especially the hypodermic injection of one fortieth to one twentieth grain of apomorphine hydrochloride) would most likely remove the source of trouble. If the foreign body cannot be removed by simple means, an operation may be deemed necessary. If due to inflammation of the stomach, bismuth and aerated soda-water are of great value. Ice and cocaine or chloretone are occasionally useful when these have failed. Sometimes it is necessary to wash the stomach out with mild antiseptic. If of nervous origin, a hypodermic injection of one twelfth to one eight grain of morphine, or five-minim doses of tincture of opium or bromide of potassium, given by the mouth, may prove successful. When resulting from tumours of tuberculosis, humanity dictates that the lethal chamber should be called into requisition and the animal put out of its misery. Easily assimilable and non-irritating food only should be given for a few days. Aerated soda-water forms the best drinking fluid.

Gastritis, or inflammation of the stomach is sometimes called gastric fever, and when of a mild type, gastric catarrh. Its causes are variable. It may be due to altered or decomposed food, distemper, microbes of various kinds, large doses of emetics or aperients, mineral poisons, chills, absorption of dressing applied to the skin, or licking the same off. It is also caused by worms, especially the broad-necked tapeworm (Taenia crassicollis), travelling into the stomach and setting up irritation. Again, diseases of the uterus, liver, kidneys, and other organs give rise to gastritis. It frequently rages as an epizootic, causing considerable mortality in some catteries, especially after cat shows.

Symptoms - The disease is ushered in by sudden vomiting of the food, followed by the repeated rejection of ropy mucus, and then, if the case is severe, this is succeeded by a thin, clear, greenish yellow or bloody fluid; saliva flows from the mouth, the thirst is great, especially for cold water, which is generally expelled almost as soon as taken; there is a distressed appearance, restlessness, or a frequent shifting of the posture. As a rule, the animal prefers to lie on its belly full length, with its limbs resting on cold objects.

Pressure on the region of the stomach causes moaning and sometimes vomiting. After the lapse of some time, when a fatal termination is advancing, the eyes appear sunken, the pupils become dilated, the expression is sad, the animal becomes cold and indifferent to his surroundings, the mouth gives off an offensive odour, and the coat is dull, open, and lustreless. The animal dies either in a comatose state or from sudden failure of the heart during a fit of vomiting.

Treatment - If recognised early, an emetic is sometimes very useful in cutting short the complaint. No food or ordinary water should be allowed until twenty-four to forty-eight hours have elapsed since the last vomiting; but a teaspoonful of Brand's essence of beef jelly and two to four tablespoonfuls of aerated water should be given every four hours. Bismuth subnitrate of carbonate in five-grain doses may be shaken on the tongue and hour before these two latter are administered. [note: the inability to diagnose the cause- simple gastritis vs FIE - makes treatment hit-or-miss]

If this means of treatment should prove ineffectual after twenty-four hours, one may conclude that the disease is of a severe type, and in this case one to five minims of the liquid extract of opium in a little mucilage, or chloretone, half to two and a half grains, should be given every three hours. Feeding by means of rectal suppositories, or injection of an ounce of milk containing a little common salt, may be attempted. Finally, if this fail, washing out the stomach with borax or boracic acid, or chinosol and warm water, and a hypodermic injection of bullock's or sheep's serum might be tried. In gastric inflammation due to infection the hypodermic injection of quinine hydrochloride or trichloride of iodine will sometimes answer when everything else has failed. Cocaine and orthoform have no advantage over opiates, especially the denarcotised preparations, in soothing the stomach. Ice in small pieces pushed down the throat sometimes answers in assuaging the thirst when the soda-water does not. In the chronic form, doses of one eighth to half grain of calomel or mercury with chalk given in bismuth three times a day are beneficial in many instances.

Enteritis, or inflammation of the intestines or bowels, frequently co-exists with gastritis, and then the disease takes on the term of gastro-enteritis. The causes, like those of gastritis, are various. It may be due to infection, bad food, drugs, foreign bodies, chills, distemper, intussusception or irritating enemas, etc. There also seems to be a special contagious type of this disease which frequently causes great mortality in catteries, especially with kittens. Generally the small intestine forms the seat of the disease, which may in rare cases, however, extend the whole length of the bowel, which is sometimes lined with croupy or diphtheritic membrane.

The symptoms are restlessness, great pain, frequent crying or moaning, offensive and profuse and frequent diarrhoea. The dejections varying in colour and consistence and frequently containing blood, and sometimes vomiting, especially when the stomach is implicated; thirst is intense, food is refused, the animal is cold, haggard, and depressed; its fur is dull, open, and lustreless, and becomes soiled, giving off an abominable odour. When the abdomen is manipulated, the animals cries or moans from the pain caused. If the pupils are dilated and the expression has an anxious appearance, and emaciation is rapid, a fatal termination may be anticipated.

The treatment varies according to the cause. If the case is seen in the early stage a tea- to a dessert-spoonful of castor-oil containing 1 to 2½ minims of liquid extract of opium may be given at once, to clear out any irritating material from the bowels and also to allay pain and irritation; or morphine in one sixteenth to one twelfth grain doses may be injected under the skin every four hours. Bismuth salicylate, in five grain doses, should be dropped on the tongue about the same time. Starch enemas containing liquid extract of opium may also be administered. Boiled milk containing bicarbonate of sod should be given in small and repeated quantities.

Turpentine stupes frequently applied to the abdomen are recommended, but where this is objected to, the floor of the abdomen may be painted with tincture of capsicum or tincture of iodine, until soreness is produced, the hair being first clipped off.

In those cases of epizootic nature, isolation is called for. The food and surroundings should be changed, and the catteries and utensils thoroughly cleaned and disinfected. In the chronic form a powder composed of bismuth salicylate 2 to 5 grains, and beta-naphtol 1 to 2½ grains, should be shaken on the tongue three times a day. Milk and rice for the best diet.

Diarrhoea, like vomiting, is not a disease of itself, but an expression of many different affections. It may be salutary or otherwise. It may be due to aperients, irritating or indigestible food, microbes, diseases of the bowels, kidneys, and liver. It frequently results from distemper or gastro-enteritis, tuberculosis, intestinal cattarrh, and from licking applications put on the skin in the treatment of skin affections. Sour milk, tainted milk or fish, and chills will also induce it. In kittens, improper food, especially during hot weather, is a common cause.

The symptoms are a looseness of the dejections from the bowels, which are passed several times a day. The stools vary in colour according to the food taken by the animal, or according to the severity of the cause; they are generally of a very offensive odour, and may contain blood.

Treatment - If the cause of the diarrhoea is due to irritating food, a dose of castor-oil will be beneficial. When due to catarrh of the bowels, the carbonate subnitrate, or salicylate of bismuth, in five-grain doses, two or three times a day, is the most appropriate treatment. If it is associated with distemper, or typhus, the bismuth salts mentioned above, or tannablin or tannigen, in 2½- to 5-grain doses, are suitable. For chronic diarrhoea, 2½ to 5 grains of salicylate of bismuth, with 1 to 5 grains of beta-naphtol, given three times a day on the food, is generally followed by recovery. Failing this, a mixture composed of dilute sulphuric acid, concentrated infusion of cloves, and concentrted infusion of haematoxylin should be tried. When the diarrhoea is due to irritation of the so-called large or posterior bowel, injections containing starch, laudanum, and tannic acid should be used.

As long as the diarrhoea lasts, no meat or meat infusions should be given. But milk, rice-pudding, bread and milk, and such-like food are suitable [note: we now know that milk causes, rather than reduces, diarrhoea].

Constipation is an impaction of faeces in the hind bowel, and is generally due to weakness of this portion of gut, or results from a cleanly animal having no place to evacuate its faeces in. Sometimes it is due to a ball of fur, and occasionally foreign bodies, such as cat's-meat skewers, being swallowed along with the meat by a greedy animal. When due to paralysis of the bowel, which is occasionally seen in young cats, the abdomen becomes distended by the faeces in the bowel. It also occurs as a symptom of spinal paralysis. The non-passage of faeces seen in cats when not well and not taking solid food must not be confounded with constipation.

The symptoms, as a rule, are the non-passage of faeces for some time, distension of the abdomen, and impaction of the bowel with faeces which can be felt by manipulating the abdomen.

Treatment - A dose of castor-oil and an enema of soapy water or glycerine will generally put matter right. If these means do not succeed, massage or kneading of the bowels, by grasping the abdomen with the hand and alternately compressing and relaxing the grasp, will assist to stimulate the intestines to force on their contents. Of course, this only applies when impaction is due to soft material and not hard foreign bodies, which, in this latter case, should be removed by the fingers or forceps. If any irritation of the mucous membrane, evidenced by frequent straining as if to pass faeces, remains after the bowels have been relieved, an enema of warm salad-oil, containing a few drops of liquid extract of opium, will allay it, and prevent straining. In case of the bowel remaining weakened or paralysed so as to bring about a recurrence of the constipation, pills containing one sixteenth grain of the alcoholic extract of nux vomica should be administered morning, noon, and night after food.

WORMS, OR INTERNAL ANIMAL PARASITES

Cats, like all other animals, are liable to be infested with worms, which may not cause any disturbance, unless in great numbers or when another disease is in existence.

The Common Round-worm is very prevalent in young kittens, generally when they are living on milk, upon which these worms thrive. Their natural residence in the cat is in the small intestine, but sometimes they wander from here into the stomach, and set up vomiting and occasionally convulsions.

Treatment - The worms should be expelled and the animal fed on a nutritious and stimulating food, such as raw fish, raw meat, and fresh birds. The milk, to which is added a pinch of salt, should be boiled. The best remedy to expel these worms is santonin given along with or followed by an aperient. The following is a convenient formula: Santonin 1 grain, Calomel ½ grain. This powder is to be dropped on the back of the tongue of an adult cat after fasting twelve hours, every other morning, until four doses have been given. Half this quantity is suitable for a cat three or four months old, and a quarter for a kitten of a month to six weeks of age.

The commonest Tapeworm of the cat is the Taenia elliptica vel jelis, with which fifty per cent or more are affected. It is caused by fleas, lice, and mange-mites, which have at some time or another infested the cat. They do not seem to cause much harm, even when numbering hundreds. In one case that I encountered the cat was in the pink of condition, and yet I found 700 of these worms. It is a delicate tapeworm with joints resembling a cucumber in outline. The ripe joints, which are often of a reddish tint, frequently become detached, and pass with the faeces, on which they are seen. They are generally termed by fanciers maw-worms.

Treatment - The worms should be expelled, and fleas, lice, or mange-mites destroyed, so as to prevent a recurrence of the trouble.

Another tapeworm of the cat is the Taenia crassicollis, or broad-necked species. It is seen only in cats that kill and eat rats and mice, in the liver of which the larval form of this parasite resides. It is a big, coarse tapeworm, measuring eighteen to thirty inches in length, and having no well-defined neck.

Treatment - For the expulsion of tapeworms there are many remedies, the best of which are areca nut, kamala, oil of male fern, pomegranate, and kousso, but as the dose of these in the crude in generally too bulky for the cat, it is advisable to give either of them, with the exception of the male fern, in their alkaloidal form, as: Koussein ½ to 2 grains, Kamalin - ½ to 2 grains, Arecoline - ¼ to ½ grain, Pelletierine - ¼ to ½ grain.

Any one of these may be given wither in pill or tabloid form, or rubbed up with milk sugar, as a powder on an empty stomach after the animal has fasted at least twelve hours, and repeated every third or fourth morning. A dose of castor-oil or jalap should be given an hour later. The oil of male-fern is best administered in a capsule. Powdered pumpkin seed may be sprinkled on the food.

DISEASES OF THE KIDNEYS

Diseases of the kidneys, such as degeneration, fatty degeneration, parasitic disease, tuberculosis, cancer, acute and chronic Bright's disease, and calculi are not rare, but, as the space at our command is limited, we only mention them.

Incontinence, or the involuntary passage of urine, is usually due to weakness of the bladder, brought on by over-distension. It sometimes results from injury to the spine and calculi.

The treatment that is best suited for this is the administration of one sixteenth grain of the alcoholic extract of nux vomica and ½ grain of quinine in a pill three times a day. If there be irritability of the bladder, soda bicarbonate 2 grains and extract of henbane one eighth grain in a pill should be given.

Retention of urine is generally caused by a calculus or chalky material blocking up the urethra or canal leading from the bladder, and preventing the exit of the fluid. If relief is not given to the bladder - that is, if the obstruction is not immeidately removed - the urine decomposes and then sets up inflammation of the bladder, and death takes place from uraemic poisoning.

Symptoms - The cat seems in pain, and makes ineffectual attempts to pass its urine; it strains to no purpose; it seems restless, getting up, lying down, rolling on its side, swishing its tail, looking towards its side, and crying. After a time the animal becomes drowsy and indifferent. If the abdomen is manipulated, the bladder will be felt to be distended, hard, and painful.

Treatment - The only rational treatment is to remove the obstruction and pass the catheter immediately, a special silver catheter, half the size of the smallest human catheter, being required for this purpose. If the urine is bloody, it may be necessary to wash out the bladder with a warm solution of boracic acid and alkalis and sedatives, but no meat or meat extracts should be given.

DISEASES OF AIR PASSAGES AND LUNGS

A Common Cold, or coryza, or acute nasal catarrh, or cold in the head, is caused by exposing the cat to inclement weather, or washing it and not thoroughly drying afterwards. It may also be due to the irritating vapours of chloroform or ether sued by inhalation to produce anaesthesia. Letting a cat out in the cold and wet after it has been used to a warm, dry dwelling sometimes results in a cold. It is not contagious, but is frequently mistaken for distemper [note: viruses and their infectiousness were not understood, it appears to be a description of mild cat flu].

Symptoms - There is frequent sneezing, and sometimes a cough; a clear watery discharge trickles from the corner of the eyelids and nostrils. After a time this discharge becomes gluey, thick, and yellowish or greenish; the eyelids become partially closed, and the haw protrudes over the front of the eyeball; food is refused, or sparingly eaten; the fur is dull and open; warm or dark corners are sought for; the animal trembles and seems miserable. If the throat is sore, there is a cough; the breathing is wheezy, and a discharge may issue from the angles of the mouth. These symptoms generally pass away in a few days.

Treatment - Where many cats are kept, an animal suffering from "a cold" should be isolated from the rest as soon as possible, as it is difficult to distinguish a simple case of "catarrh" from the early stage of distemper. A warm place, well ventilated, but free from draughts, is essential. Raw meat, scraped and given three times a day, is the best diet. Fish, milk, bread-and-milk, or rice pudding should be offered.

A small pilule of half a grain of quinine sulphate should be dropped at the back of the mouth three times a day. The nostrils and eyelids should be sponged with a warm solution of boric acid, containing eight grains to the ounce of water, and afterwards smeared with a little white vaseline three times a day. Sanitas or turpentine should be sprinkled on the floor of the room. Great relief is often given by inhaling the fumes of eucalyptus oil dropped into a jug of boiling water.

Chronic Nasal Catarrh, sometimes called "feline glanders," differs from the preceding complaint, inasmuch as it runs a longer and more persistent course; it may, however, follow on simple catarrh which has been neglected. Distemper is one of the commonest causes of it, but it is also seen after diptheria. It may occur as a symptom of tuberculosis, foreign bodies in the nasal channels, malignant growths, such as sarcoma or cancer attacking the turbinated bones, diseased bone, or teeth, etc. When neglected, it may last for months or even years, and is frequently incurable.

Symptoms - There is persistent gluey odourless, or sometimes foetid discharge either of a gelatinous or yellowish appearance, with or without streaks of blood from the nostrils, the outsides of which are sometimes ulcerated. The throat may be swollen; the appetite and general condition of the animals are often preserved. Sometimes there is an abscess in the inner corner of the eye.

Treatment - in those cases that are due to malignant tumours or tuberculosis, and in consequence, incurable, merciful destruction of the animal is called for. If due to foreign bodies - such as fish-bones, pieces of grass, or food, or to diseased teeth - they should be removed. Syringing the nostrils, so as to wash the diseased lining membrane of the nasal channels, with some mild antiseptic is the only means to insure success. The mode of procedure is this: A skilled assistant must firmly secure the animal between his hands - that is, he holds the limbs firmly - then the operator grasps the head with his left hand, taking care to keep the mouth shut by means of the thumb and index finger, and steadies it on the table; and with the right hand he carefully and gently passes the pipe of the syringe up one of the nasal channels and the presses out the fluid. When this is finished, the other nostril is served the same.

The following is a suitable formula for the solution to be injected: Alum - 30 grains, Boric Acid - 2 drachms, Liquid Extract of Hydrastis - 2 drachms, Warm Water - ½ pint. This should be used every other day until some benefit is derived from it. If the disease is not amenable after a fortnight's adoption of this treatment, the following should be substituted: Tincture of Iodine (BP) - 10 minims, Glycerine - 6 ounces, Warm Water - 1 ounce.

Pills of iron, quinine, arsenic, and such-like, as well as plenty of flesh food along with cod-liver oil, should be given. Fresh air is invigorating, and a change to the seaside sometimes does miracles. Eucalyptus sprinkle about the cat's box is useful, because it acts not only as an antiseptic, but as a stimulant to the mucous membranes of the nostrils.

Bronchitis, or inflammation of the bronchial or air tubes, may occur as a sequel to catarrh or during its course, and may also accompany distemper. It is also due to small worms in the tubes; washing followed by exposure to draughts; medicine, especially light powders, going down the windpipe, etc. It is frequently due to tuberculosis [note: from milk, frequently fed to cats].

Symptoms - There is a frequent cough, the breathing is difficult. The desire for warmth is great; there is shivering, and perhaps a discharge from the eyes and nose. On listening to the chest by means of the stethoscope, wheezing or hissing or bubbling sounds will be heard.

Treatment - the animal should be kept in a constant temperature of 60oF, and have warm milk and beef administered to it. The throat and sides should be rubbed with oil of mustard. Inhalations of steam are useful with expectoration seems difficult. Kermese mineral (two grains) and powdered squill (one grain) should be given.

Pneumonia, or inflammation of the substance of the lungs, may be due to various causes, such as exposure to cold, chills after washing, medicines passing down the windpipe, foreign bodies, blood-poisoning, small worms, and principally distemper or tuberculosis. It may be associated with pleurisy or bronchitis, and is then termed pleuro-pneumonia or broncho-pneumonia respectively; and also sometimes with a purulent collection or tuberculosis, and then it receives the names septic pneumonia or tubercular pneumonia, or phthisis.

Symptoms - At first there is intense shivering, a great desire for warmth, loss of appetite, dull appearance, dull cough, sickness, difficulty of breathing, which after some days becomes laboured or panting. On auscultation of the chest the characteristic sounds may be heard. At first fine crepitations, then a day or two after the tubular or blowing sounds, and when convalescence sets in the fine crackling of crepitating sounds are heard again. The cough becomes more frequent and the appetite increases. On the other hand, if there be no improvement, the coat becomes dull and open, the eyes sunken, and the pupils dilated; the flanks move up and down like a pump-handle, and the breath become foetid; food is totally refused, and diarrhoea sets in, a fatal termination is to be anticipated.

Treatment - The animal should be kept in a temperature of 60oF, and fresh air, but no draughts, allowed. The sides are to be rubbed with oil of mustard, or painted with tincture of iodine, or an ointment composed of one part of tartar emetic to eight of lard. Quinine sulphate, ½ grain; alcoholic extract of nux vomica, one sixteenth grain; and extract of digitalis, one eighth grain, in a pill, may be administered every four hours, and nourishing food given. In the case of tubercular pneumonia, which is generally chronic, the animal should be destroyed.

Pleurisy, or inflammation of the covering of the lungs or internal lining of the chest cavity , in the cat as well as in the dog, is chiefly due to tuberculosis. It may however, result from pneumonia, abscess in the lung, cancer, parasites, foreign bodies, gunshot wounds, cold, etc. It is generally accompanied with a dirty sanious, or clear amber-tinted, or port-wine coloured fluid, sometimes containing yellowish-white strings of lymph floating in it in the chest cavity. One or both sides may be affected. It is usually fatal.

Symptoms - The cat has an anxious, painful facial expression, and moans, or rather grunts, and sometimes attempts to bite when the chest is touched or made to move; the abdomen is retracted, and the breathing, which is short and jerky, seems to be performed by the flanks. There is a slight or suppressed cough, but this is often absent. The animal wastes away, the coat becomes dull and open and lustreless, and the hairs are easily pulled out. The creature hides under the furniture and refuses its food, and when a fatal termination is at hand, the flanks move up and down like a pump-handle, the breathing becomes difficult and suffocative, the mouth, which is offensive, being opened at every inspiratory and expiratory effort; the tongue becomes purplish, the elbows turn out, the cat assumes a squatting position on all-fours, and a foetid diarrhoea sets in.

Treatment - Although generally fatal, treatment may be desired to be attempted. The chest should be painted with tincture of iodine or oil of mustard; if there be much pain, a hypodermic injection of morphine will prove useful, and a pill composed of ¼ grain powdered digitalis leaves, ½ grain of sulphate of quinine, and 1 grain of iodide of potassium, administered three times a day. When the breathing becomes difficult in consequence of the accumulation of fluid in the chest cavity, it may be deemed advisable to draw the fluid off by means of a trocar. Nourishing liquid food, such as milk, Mosquera's beef jelly, or eggs, should be given, little and often.

DISTEMPER

Distemper is a contagious, inoculable fever, due to a specific microbe (the cocco-bacillus, or pasteurella of Lignieres), and is similar, if not identical, to that causing distemper in the dog. Krajewsky, Laosson, Lignieres, and others have experimentally demonstrated its identity, but I have never observed the cat naturally giving the dog distemper, nor vice versa, and I believe this is the experience of most veterinary surgeons in this country.

Note: The disease is not the same as that in dogs (canine parvovirus) nor was it caused by Pasteurella. The generic term "distemper" was used for several different, and at that time unidentified, viral illnesses, mostly Feline calicivirus (cat flu) and FIE (panleukopaenia), possibly also FIP, FeLV and/or FIV for the "chronic wasting forms". Hence the symptoms of "distemper" were described as variable. Pasteurella is a secondary infection of animals already sick. It would be several decades before the causative viruses were identified. It was also called "show fever".

The microbe of distemper - which belongs to the same class of micro-organisms, the pasteurella, that causes influenza in the horse, fowl cholera, swine-fever, guinea-pig distemper etc - is generally found in the blood which it alters to such a degree as to make so profound an impression on the system as to diminish its natural resistance to the ordinary germs, which become, in consequence, increased in virulence, and cause the various phenomena by which we know the disease. It is difficult to detect in the body after about a week [note: some cases of distemper could be due to FeLV or FIV causing immune deficiency so that the cat picked up other infections].

The disease varies in severity according to the degree of virulence of the microbe [note: probably due to being different viruses entirely]. If this is very virulent, it causes a very acute or septic disease, as is observed in the typhus of gastro-enteric outbreak, which kills off a large number of animals within a few days or even hours [note: FIE]. If it is of milder strength, we get a subacute form with localisations, such as we usually see in distemper. There is also a chronic form, which lasts a long time, and which tries the patience of the owner as well as the vitality of the sufferer. Finally, a chronic wasting or cachectic form is sometimes observed; it resembles the "going light" in birds and other animals, and may be mistaken for starvation, which it simulates very much [note: possibly FIP, FeLV or FIV].

The microbe may exit in a healthy cat's body for weeks without causing it any disturbance until, perhaps, the animal catches cold, or is depressed in some other manner. However, an apparently healthy animal with the microbe may be infective for other cats.

Period of Incubation - this varies according to the degree of virulency of the microbe and the state of the cat's system and the surroundings in which it is kept. A very virulent infection has a much shorter period of incubation than a mild infection. Whereas the form may cause distemper in from two to five days, the latter takes from one to three weeks. It seems doubtful whether the specific microbe causes the symptoms we usually see in distemper, or whether these are due to a secondary infection resulting from the invasion of the normal microbes of the body, which has become virulent, and prey upon their hosts.

Duration of the Disease - This, like the period of incubation, varies according also according to the degree of virulence of the virus [note: meaning microbe, not virus in the modern sense]. A very virulent virus kills in a few days or even hours, or the animal recovers very quickly. It is not so with a virus of a milder degree of virulence, which may cause symptoms that take from one to five or six weeks to disappear, if the animal recover. In other cases the disease shows itself in so mild a form that it appears like an ordinary catarrh, and recovery is established within a few days. In a few instances death takes place suddenly before any premonitory symptoms have had time to develop.

The principal sources of propagation of the infection are cat shows, catteries (especially those belonging to people who exhibit), homes for lost and stray cats, and institutions that take in these animals as boarders. The cat dealer's shop is not free from blame - many newly purchased kittens develop distemper a few days after purchase, contracted, no doubt at the dealer's. Many cases have been traced to the cattery where the female has been sent to stud. Hampers, cages, and persons coming from infected catteries are so many media of contagion. Even if a cat has apparently recovered from the disease, it may still give off infection and contaminate other cats for a variable but uncertain period.

Although the disease may be seen at all times of the year, it is most prevalent during spring and autumn, especially if the weather is changeable and wet. Moisture of the atmosphere favours the increase of distemper. Wet, following very dry weather, continuous dampness and rain, all predispose an animal to disease. Where catteries or homes for lost and strays are continuously being washed out and not properly dried, especially in damp weather, before the cats are allowed into the rooms, distemper is very prevalent. Where too many cats are crowded into a given space, especially if the place is badly lighted and not very well ventilated, this is favourable for the contamination of the inmates.

The mortality varies according to the breed of the animal, its surroundings, and the degree of virulence of the infection. Seasons and periods have also some bearing on it. Common-bred cats allowed to roam out in the open at their will are more likely to recover from the disease, but if confined to cages or in catteries, or in the house, the mortality is quite twenty-five per cent. The long-haired cats are less resistant against it, and as many as fifty per cent die. In the Siamese breed of cats, the fatality is as high as ninety out of every hundred. The younger the animals, the greater the death-rate; yet, on the other hand, if old animals are very fat or anaemic from want of fresh air and exercise, the mortality is just as high [note: in long-hairs and Siamese, the mortality was partly due to excessive inbreeding depressing the immune system].

Many cats are resistant at one time against the infection, others have it in a mild form, and yet others have it severely; but this does not always prevent them from having it again at some future period. My experience is that a cat may frequently have a recurrence of distemper at least two or three times, and then succumb to it. One season it may appear as a contagious catarrh, another season as an infectious sore throat, and at other times as a bronchitis or pneumonia, and, lastly, as a contagious gastritis or gastro-enteritis. Frequently all these forms may co-exist in a single outbreak, and often a single animal exhibits the whole of these manifestations. For the convenience of description of the symptoms of this multiform malady we divide it into five principle forms as follows:-

1. The Catarrhal, attacking chiefly the eyes and nostrils

2. The Pharyngeal or Tonsillar, affecting the region of the throat

3. The Pulmonary or Chest form

4. The Abdominal or Gastro-enteric

5. The Cachectic or Wasting

The Catarrhal form of distemper is that which is generally seen in the cat, and is the least fatal of any. The first symptoms noticed are a watery discharge from one and sometimes both eyes, the lids of which may be partially or completely closed, so as to hide the front of the eye, and a frequent licking of the upper lip and nose as if they were parched and burning. After a day or so the inner lining of the eyelids may be very much reddened, swollen, and giving rise to a yellow-white or greenish-white thick discharge, which adheres to the lids and seals them together. There may also be shivering fits, a dull open coat, and a great desire for warmth (this being so intense in some cases that the animals frequently gets under the grate when a fire is in it). There is sneezing, followed by a snuffling kind of breathing; the nostrils discharge a thick, ropy, whitish or greenish matter, which clings to their openings, and very often closes them up. When the pharynx or larynx is the seat of catarrh there are frequent fits of coughing. The appetite is diminished or absent, but thirst is, as a rule, great. There may also be seen at times vomiting, diarrhoea, or constipation. Emaciation is gradual and slight, or rapid and great, varying according to the severity of the symptoms.

The breathing is not much altered in the majority of cases, but in a few instances it becomes frequent. The temperature rises a few degrees, but this is variable, and it is sometimes normal. The body and limbs feel cold to the touch, and sometimes give off an offensive odour. The tongue, lips, hard and soft palates, and gums (especially around the teeth) are occasionally ulcerated. Now and again the eyes become the seat of ulceration, which on rare occasions becomes perforated; at other times they become affected with a severe inflammation, which extends to the whole eyeball and destroys this organ. There is at times dulness [sic] or drowsiness, and the animal seeks dark corners or gets under the furniture. Many cats from sheer nervousness, especially in strange places, avoid the fire and seek obscure or lofty positions. Recovery generally takes place within a fortnight or three weeks, but death may take place within twenty-four to forty-eight hours from the commencement of the attack.

The Pharyngeal, Tonsillar, or Throat form is the most deadly manifestation of distemper. The first symptom to attract attention is the drivelling of clear, ropy, albuminous saliva from the corners of the mouth. The animal crouches upon all four of its limbs; there is a frequent gulping movement, and a sound is emitted from the throat as if there was an attempt to swallow the thick ropy saliva which clings about the mouth and pharynx; the swallowing seems difficult or impossible; food is refused, but thirst is constant, although the animal seems incapable of swallowing; there is a great dulness or depression, and the cat appears indifferent to its surroundings.

On examination of the outside of the throat it is found swollen and painful, the glands are enlarged, and there appears to be a gurgling noise at each inspiration and expiration. On inspection of the mouth and back of the throat, the tongue and pharynx are found to be covered with a thick, ropy, bubbling saliva, the mucous membrane is swollen and congested, and the soft palate is of a pinkish or even dark reddish arborescent appearance, due to the congested state of the small blood-vessels. Sometimes ulcers appear on the hard and soft palates. After a day or so the depression increases, there is a discharge from the eyes and nostrils, which appears at first as a clear viscid fluid, and afterwards becomes yellowish or dirty green in colour, and, if the animal lives long enough, ultimately bloody, in consequence of it irritating the mucous membranes and surrounding skin of the eyes and nose. There may also be a catarrhal or purulent foetid discharge from one or both ears, but this is quite exceptional, and is mostly seen in cases having a fatal termination.

If the prostration is very great, and the discharge from the mouth, nostrils, and eyes become foetid, coupled with total loss of appetite, and no abatement of the other symptoms, a fatal termination is to be anticipated. Late in the complaint the pharyngeal mucus may become of a dirty colour or sanious; purple spots appear on the tongue or gums, and lips, and there is a moan or cry emitted at each respiratory effort; convulsive movements of the muscles of the temples, shoulders, and thighs set in, and death takes place from intoxication. The temperature rises at first, but when a fatal termination is to be anticipated it falls below the normal.

The Pulmonary or Chest form, although not so frequently seen in the cat as in the dog, may appear from the outset as a distinct localisation, or follow or intervene during an attack of the other forms as a complication. It may or may not be ushered in by shivering fits; the coat becomes dull and open, there is sneezing or coughing, or both; tears run from the eyes, and mucus issues from the nostrils, and there is a great desire for warmth. The temperature is elevated, and varies from 102.5o to 106 o (Fahrenheit], but rarely tunning a typical course. The cough, when present, is frequent and rattling or harsh, and sometimes dull. On listening to the chest wheezing, rattling, or blowing, or rubbing, or splashing sounds may be heard. Emaciation is either gradual or rapid, thirst is generally great, but the appetite is diminished or absent.

The breathing is either quickened or the inspiratory and expiratory efforts may be prolonged and accompanies or not with a moan or grunt, which is sometimes associated with fluid in the chest cavity, which is known by the pumping or lifting action of the flanks, this effusion in one or both of the pleural sacs being either of a clear greenish or amber-tinted or bloody or dirty yellowish appearance, and sometimes of a foetid odour. Besides pleurisy, which is only occasionally encountered, there may be pneumonia, broncho-pneumonia, or bronchitis, according to the structure of lung involved in this form of distemper. (For a description of these localisations or complications, see under their respective headings.)

The lesions of the lungs may be slight, and yet the symptoms may be severe; on the contrary, the lesions may be extensive, and the resulting symptoms comparatively slight. If the fever remains high, the appetite abolished, the pupils dilated, the breathing plaintive and very rapid, and prostration great, death soon takes place from failure of the hear due to intoxication. In many cases, though, the fever is not intense, and yet death intervenes.

The Abdominal, Gastric, or Gastro-enteric form of distemper is oftener seen than either the pharyngeal or pulmonary form, and may occur as a very acute and rapidly fatal manifestation, or as a chronic disease. It frequently accompanies the other forms. In acute cases there is sudden vomiting of food, quickly followed by a frequently repeated ejection of thick, slimy, and frothy mucus, and ultimately by a thin, watery, serous fluid, which is of an olive-green or yellowish appearance. The thirst is intense, and no sooner is water sipped than it is expelled. There is frequent diarrhoea; the stools at first seem fluid, then become watery, sometimes bloody, and very foetid. The appetite is suppressed, and the animal becomes cold and indifferent to its surroundings, the facial expression is pinched, the eyes are semi-closed; the coat is dull and open, and on pressure over the region of the stomach pain is evinced by a moan or cry, and death usually takes place in a few hours. There is not as a rule any discharge from the eyes and nostrils.