Early Naturalists' Texts About Domestic Cats

Wenceslas Wratislaw Of Miteowitz. What He Saw In The Turkish Metropolis, Constantinople ; Experienced In His Captivity; And After His Happy Return To His Country, Committed To Writing In The Year Of Our Lord 1599.

Literally Translated From The Original Bohemian By A. H. Wratislaw, M.A. Head-Master Of The Grammar School, Bury St. Edmunds, And Formerly Fellow And Tutor Of Christ's College, Cambridge.

Note: The original text was first published in 1777 and a second edition published in 1807, These excerpts are from a translation of the 1807 edition. I have broken it into paragraphs for ease of reading. It is freely available online as an ebook.

We saw also, in Constantinople, wild beasts of various nature and form ; lynxes and wild cats, leopards, bears, and lions, so tame and domesticated, that they are led up and down the city by chains and ropes.

In Constantinople there are also large gardens, surrounded with walls, on which cats usually jump and assemble, waiting at certain hours for people to come and give them alms. For it is customary among the Turks to boil and bake paunches, lights, livers, and pieces of meat, and carry them in wooden buckets up and down the city, crying out, “Kedy et, kedy et !” i.e. ” Cat’s meat!”

A kitchen-boy also carries on his shoulders a number of spits, upon which are baked pieces of meat, liver, and spleen, and cries in the streets, ”Tiupek et, tiupek et !” i e. ” Dog’s meat !” till they ring again. Behind him run three-score dogs or more, looking to him to be served. The Turks buy this food, distribute it to the dogs, and throw it to the cats upon the wall ; for these superstitious and barbarous people imagine that they obtain especial favour in the eyes of God by giving alms even to irrational cattle, cats, dogs, fish, birds, and other live creatures; and, therefore, they consider it a great sin to kill and destroy captured birds, and prefer to ransom them with money, and release them into their previous state of freedom, that they may fly away.

They also throw bread to fishes in the water for them to live upon. They have a custom of distributing bread, meat, and other victuals to cats and dogs, of which a very large number are found daily in the streets, at certain places, and definite times ; and it is an undoubted truth that on the walls of these gardens the cats breakfast in good time in the morning, and assemble for the second time at the hour of the evening meal, in large bodies out of the whole city, and stand on the look out ; for we went purposely to these walls, listened to their caterwauling, and, with great laughter, watched how they ran out of the houses and assembled.

So, too, we several times saw Turkish matrons [married women] and old women buying pieces of meat on the spit from the kitchen-boys, or from the public kitchens, which are not far from this place, and handing them on a long stick or wand to the cats as they sit on the walls, muttering meanwhile a kind of Turkish prayers.

Compare this treatment of cats with that in a later section:

Once, on a festival after holy mass, a master-carpenter, a Christian prisoner, invited the chaplain and me to partake of a fine tabby tom-cat, which he had fed up for a long time, and named Marko. It was a fine and well-fatted cat, and I saw, with my own eyes, when the carpenter cut his throat. As my partner, Mr. Chaplain, would not go, and fettered together as we were I could not go without him, he sent us, as a present, a fore- shoulder of the cat, which I ate. It was nice meat, and I enjoyed it very much, for hunger is a capital cook, so that nothing makes one disgusted ; and if I had only had plenty of such tom-cats, they would have done me no harm.

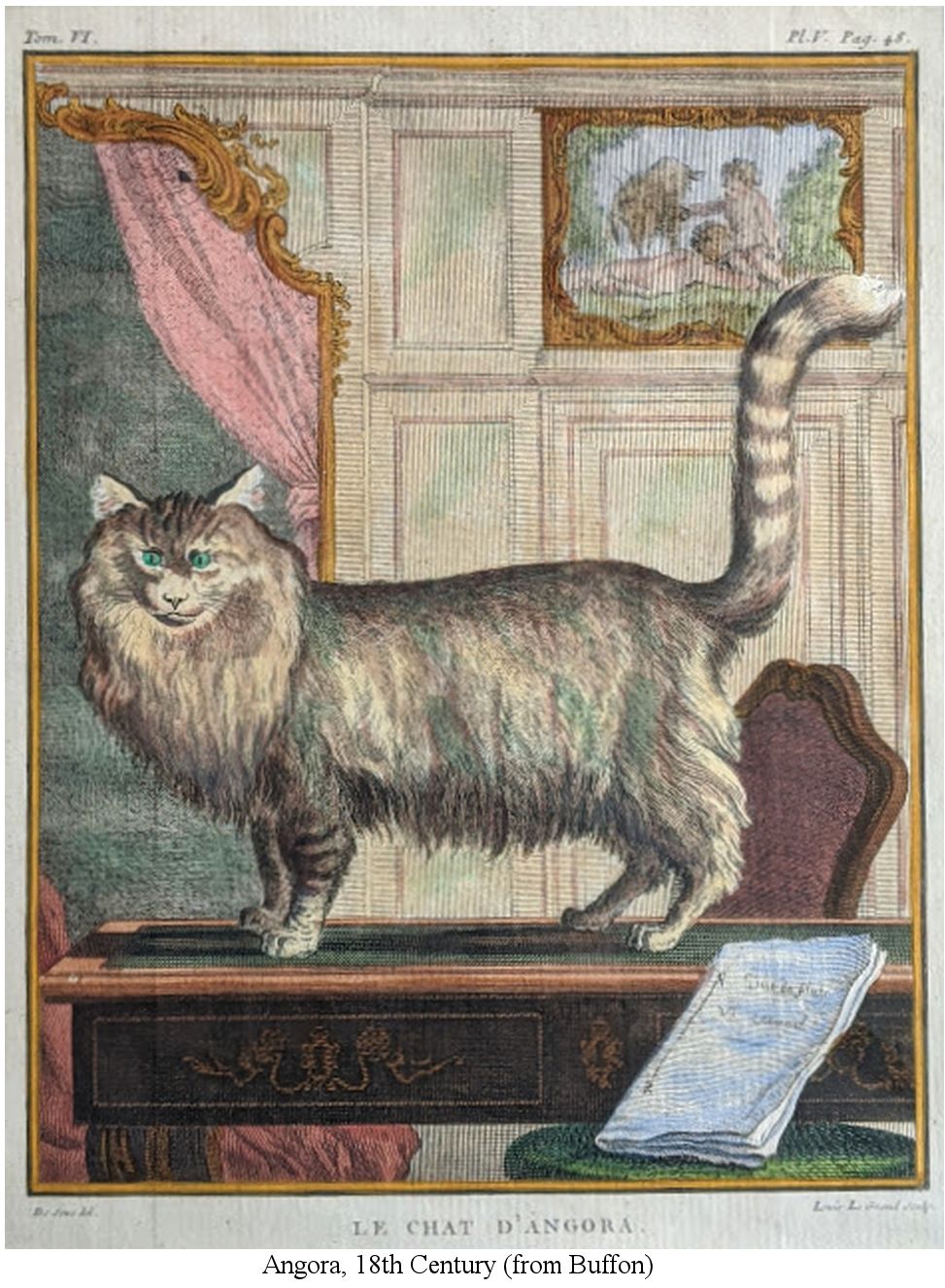

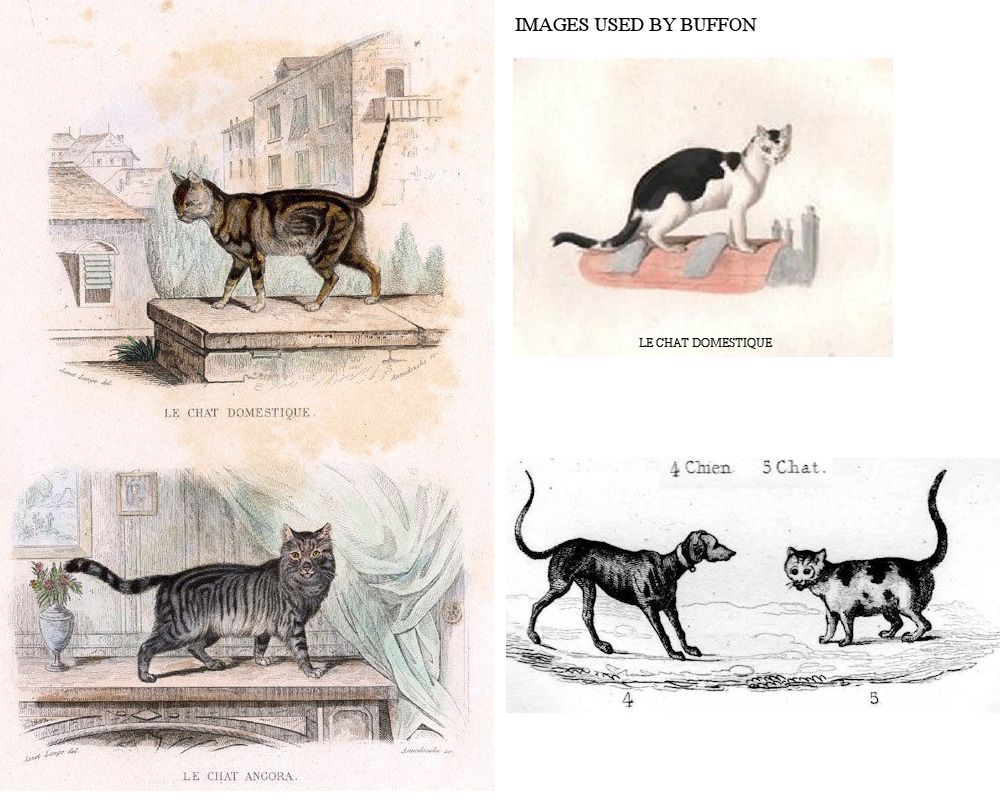

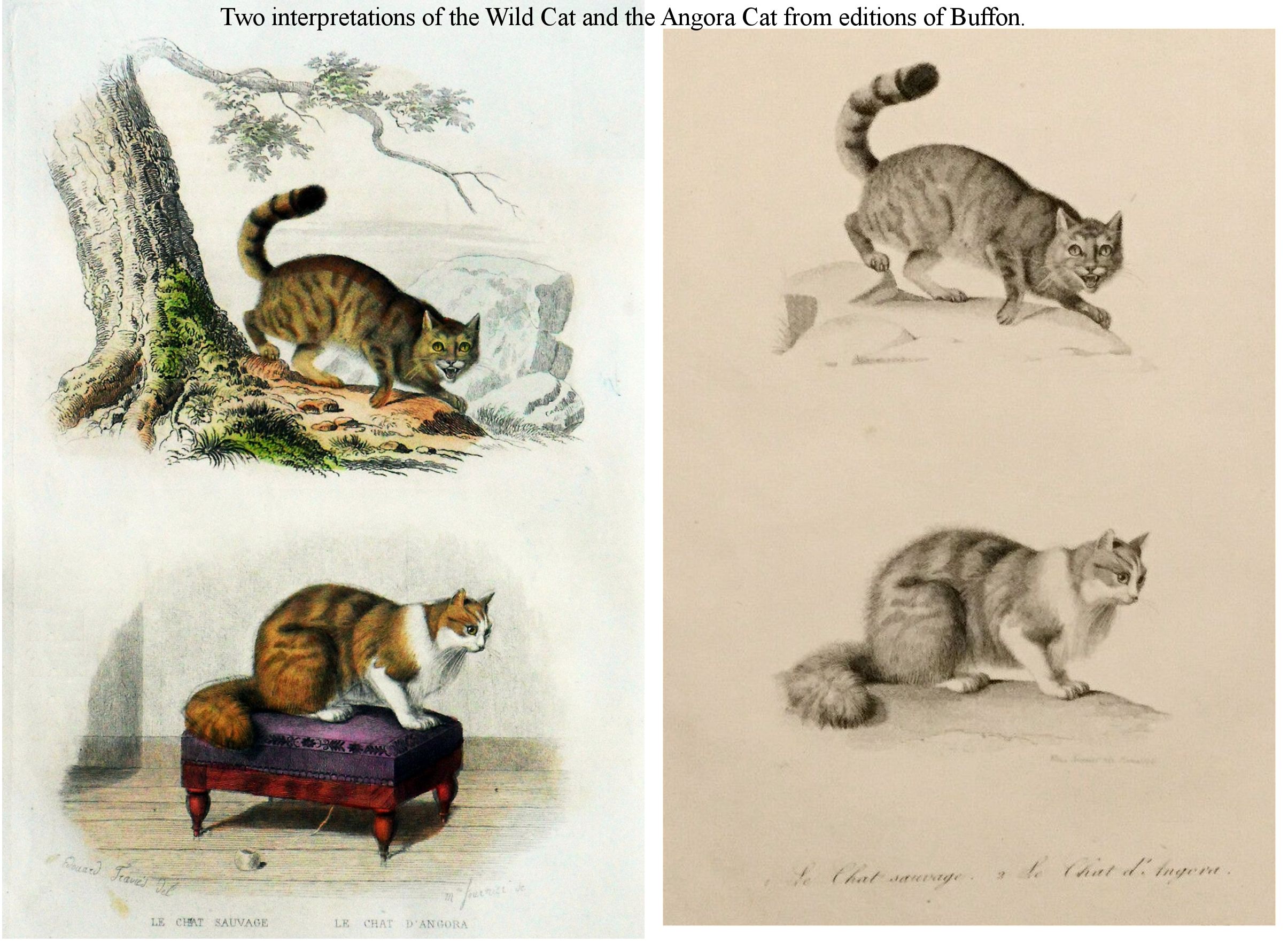

Histoire Naturelle Vol 4: The Natural history of The Cat

Georges Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1767)

Translated from French to English 1781 by William Smellie

THE cat is an unfaithful domestic, and kept only from the necessity we find of opposing him to other domestics still more incommodious, and which cannot be hunted; for we make no account of those people, who, being fond of all brutes, foolishly keep cats for their amusement. Though these animals, when young, are frolicksome [sic] and beautiful, they possess, at the same time, an innate malice, and perverse disposition, which increase as they grow up, and which education learns them to conceal, but not to subdue. From determined robbers, the best education can only covert them into flattering thieves; for they have the same address, subtlety, and desire of plunder. Like thieves, they know how to conceal their steps and their designs, to watch opportunities, to catch the proper moment for laying hold of their prey, to fly from punishment, and to remain at a distance till sollicited [sic] to return. They easily assume the habits of society, but never acquire its manners; for they have only the appearance of attachment or friendship. This disingenuity of character is betrayed by the obliquity of their movements, and the duplicity of their eyes. They never look their best benefactor in the face; but, either from distrust or falseness, they approach him by windings, in order to procure caresses, in which they have no other pleasure than what arises from flattering those who bestow them. Very different from that faithful animal the dog, whose sentiments totally centre in the person and happiness of his master, the cat appears to have no feelings which are not interested, to have no affection that is not conditional, and to carry on no intercourse with men, but in the view of turning it to his own advantage. By these dispositions, the cat has a greater relation to man than to the dog, in whom there is not the smallest mark of insincerity or unjustice.

The form and temperament of the cat's body perfectly accord with his temper and disposition, He is jolly, nimble, dexterous, cleanly, and voluptuous. He loves ease, and chooses the softest and warmest situations for repose. He is likewise extremely amorous, and, what is singular in the animal world, the female seems to be more ardent than the male. She not only invites and goes in quest of him, but announces, by loud cries, the fury of her passion, or rather the pressure of her necessities; and, when the male disdains her, or flies from her, she pursues, tears, and, though their embraces are always accompanied with the most acute pain, compels him to comply with her desires. This passionate ardour of the female continues only nine or ten days, and it happens generally twice a-year, though often thrice, and even four times. The period of gestation is 55 or 56 days, and four or five are commonly produced at a litter. As the male has an inclination to devour the young, the female carefully conceals them; and, when apprehensive of a discovery, she takes them up, one by one, in her mouth, and hides them in holes, and in places which are inaccessible. After suckling them a few weeks, she present them with mice, or young birds, to learn them to eat flesh. But, by an unaccountable caprice, these same careful, tender, and affectionate mothers, sometimes assume an unnatural species of cruelty, and devour their own offspring.

Young cats are gay, vivacious, and frolicksome, and, if nothing was to be apprehended from their claws, would afford excellent amusement to children. But their toying, though always light and agreeable, is never altogether innocent, and is soon converted into habitual malice. As their talents can only be exerted with advantage against small animals, they lie in wait, with great patience and perseverance, to seize birds, mice, and rats, and, without any instruction, become more expert hunters than the best trained dogs. Naturally averse to every kind of restraint, they are incapable of any system of education. It is related, however, that the Greek Monks of the island of Cyprus had trained cats to hunt and destroy serpents, with which that island was much infested [Descript. des isles de l'Archipel, par Dapper, p 51]. But this hunting must rather be ascribed to their general desire of slaughter, than to any kind of tractability or obedience; for they delight in watching, attacking, and destroying all weak animals indiscriminately, as birds, young rabbits, hares, rats, mice, bats, moles, frogs, toads, lizards, and serpents. They have not that docility and fineness of scent, for which the dog is so eminently distinguished. They hunt only by the eye: Neither do they properly pursue, but lie in wait, and attack animals by surprise; and, after sporting with them, and tormenting them for a long time, they at last kill them without any necessity, and even when well fed, purely to gratify their sanguinary appetite.

The most obvious physical cause of their watching and catching other animals by surprise, proceeds from the advantage they derive from the peculiar structure of their eyes. In man and most other animals, the pupil is capable of a certain degree of contraction and dilation. It enlarges a little when the light is faint, and contracts when the light is too splendid. But, in cats and night birds, as the owls, &c. the contraction and dilation are so great, that the pupil, which is round in the dark, becomes, when exposed to much light, long and narrow like a line. Hence these animals see better in the night than in the day. The pupil of the cat, during the day, is perpetually contracted, and it is only by a strong effort that he can see with a strong light. But, in the twilight, the pupil resumes its natural roundness, the animal enjoys perfect vision, and takes advantage of this superiority to discover and surprise his prey.

Though cats live in our houses, they are not entirely domestic. Even the tamest cats are not under the smallest subjection, but may rather be said to enjoy perfect liberty; for they act only to please themselves; and it is impossible to retain them a moment after they choose to go off. Besides, most cats are half wild. They know not their masters, and only frequent barns, offices, or kitchens, when pressed with hunger.

Though greater numbers of them are reared than of dogs, as they are seldom seen, their number makes less impression on us. They contract a stronger attachment to our houses than to our persons. When carried to the distance of a league or two, they return of their own accord, probably because they are acquainted with all the retreats of the mice, and all the passages and outlets of the house, and because the labour of returning is less than that which would be necessary to acquire the same knowledge in a new habitation. They have a natural antipathy at water, cold, and bad smells. They are fond of basking in the sun, and of lying in warm places. They are also fond of perfumes, and willingly allow themselves to be taken and caressed by persons who carry aromatic substances. They are so delighted with valerian root, that it seems to throw them into a transport of pleasure. To preserve this plant in our gardens, we are under the necessity of fencing it round with a rail; for the cats smell it at a distance, collect about it in numbers, and, by frequently rubbing, and passing and repassing over it, they soon destroy the plant.

Cats require fifteen or eighteen months before they come to their full growth. In less than a year, they are capable of procreating, and retain this faculty during life, which extends not beyond nine or ten years. They are, however, extremely hardy and vivacious, and are more nervous than other animals which live longer.

Cats eat slowly, and with difficulty: Their teeth are so short and ill placed, that they can tear, but not grind their food. Hence they always prefer the most tender victuals, as fishes, which they devour either raw or boiled. They drink frequently; their sleep is light; and they often assume the appearance of sleeping, when they are only meditating mischief. They walk softly, and without making any noise. As their hair is always clean and dry, it is easily electrified, and the sparks become visible when it is rubbed across with the hand in the dark. Their eyes also sparkle in the dark like diamonds, and seem to throw out, in the night, the light they imbibe during the day.

The wild cat couples with the domestic kind; and, consequently, they belong to the same species. It is not uncommon to see both males and females quit their houses in the season of love, go to the woods in quest of wild cats, and afterwards return to their former habitations. It is for this reason that some domestic cats so perfectly resemble the wild cat. The only real difference is internal; for the intestines of the domestic cat are commonly much longer than those of the wild cat. The latter, however, is larger and stronger than the domestic kind; his lips are always black; his ears are also stiffer; his tail larger, and his colours more constant. In this climate there is only one species of wild cat; and it appears from the testimony of travellers, that this kind is found in all climates, without being subject to much variety. They existed in America before its discovery by the Europeans. A hunter brought one of them to Christopher Columbus [Vie de Christ. Columb. Part. 2. p167].

which was of an ordinary size, of a brownish grey colour, and having a very long and strong tail. They were likewise found in Peru [Hist. des Incas, tom. 2. p121] though not in a domestic state, and also in Canada [Hist. de Nouvelle France, par Charlevoix, tom. 3. p407] in the country of the Illinois, &c. They have been seen in many places of Africa, as in Guiney [Prevot, tom. 4. p230.] and the Gold Coast; at Madagascar [Relation de Francois Caiuche, p225] where the natives keep them in a domestic state; and at the Cape of Good Hope [Descript. du Cap par Kolbe, p49] where M. Kolbe says there is likewise a wild kind, of a blue colour; but they are not numerous. These blue, or rather slate coloured cats, are also found in Asia.

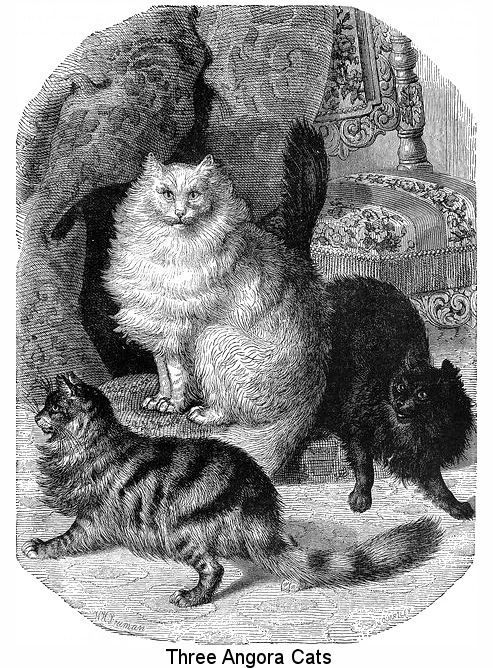

"In Persia," says Pietro della Valle [Voyage, tom. 5. p98] "there is a species of cats which properly belong to the province of Chorazan. Their figure and size are the same with those of the common cat. Their beauty consists in the colour of their hair, which is grey, and uniformly the same over the whole body, excepting that it is darker on the back and head, and clearer on the breast and belly, where it approaches to whiteness, with that agreeable mixture of clare-obscure, to use the language of the painters, which has always a wonderful effect. Besides, their hair is fine, shining, soft as silk, and so long, that, though not frizled [sic], it forms ringlets in some parts, and particularly under the throat. These cats are among other cats, what the water-dog is among other dogs. The most beautiful part of the body is the tail, which is very long, and covered with hair five or six inches in length. They extend and turn it upon their backs, like the squirrel, the point resembling a plume of feathers. They are very tame; and the Portuguese have brought them from Persia into India." The same author adds, that he had four couple of these cats, which he intended to bring to Italy. From this description it appears, that the Persian cats resemble, in colour, those we call Chartreux cats, and that, excepting in colour, they have a perfect resemblance to the cat of Angora. It is probable, therefore, that the cat of Chorazan in Persia, the cat of Angora in Syria, and the Chartreux cat, constitute but one race, whose beauty proceeds from the particular influence of the climate, as the Spanish cats, which are red, black, and white, owe their beauty to the climate of Spain. It may be remarked in general, that, of all climates on the habitable parts of the globe, those of Spain and Syria are most favourable to the production of beautiful varieties in natural objects. In Spain and Syria, the sheep, the goats, the dogs, the cats, the rabbits, &c. have the finest wool, the most beautiful and longest hair, and the most agreeable and variegated colours. These climates, it would appear, soften Nature, and embellish the form of all animals.

The wild cat, like most other animals in a savage sate, has coarse colours, and hard hair. But, when rendered domestic, the hair softens, the colours vary; and, in the favourable climates of Chorazan and Syria, the hair grows long, fine, and bushy; all the colours become more delicate; the black and red change into a shining brown, and the greyish brown is converted into an ash-coloured grey. By comparing the wild cat with the Chartreux cat, it will be found, that they differ only in this degradation in the shades of colour. As these animals have always more or less whiteness on the sides and belly, it is apparent, that, to produce cats entirely white and with long hair, like the cats of Angora, nothing farther is requisite, than to join those which have the greatest quantity of white, as has been done to procure white rabbits, dogs, goats, stags, &c. In the Spanish cat, which is only another variety of the wild kind, the colours, instead of being weakened by uniform shades, as in the cat of Syria, are exalted, and have become more lively and brilliant; the yellow is changed into red, the brown into black, and the grey into white. These cats, though transported into America, have not degenerated, but preserve their beautiful colours. "In the Antilles," says Father Tertre, "there are a number of cats, which have probably been brought from Spain. They are mostly marked with red, white, and black. Several of our countrymen, after eating the flesh, carry the skins of these cats into France. When we first arrived at Guadaloupe, the cats were so accustomed to feed on partridges, pigeons, thrushes, and other small birds, that they disdained the rats; but, when the game was diminished, they attacked the rats with great fury [Hist. gen. des Antilles, par. Le P. du Tertre, tom. 2. p306.] &c. In general, cats are not subject, like dogs, to degeneration, when transported into warm climates. "The European cats," Bosman remarks, "when carried to Guiney, change not, like the dogs, but preserve their original figure," &c. Their nature is indeed more constant; and, as their domestic state is neither so complete, so universal, nor, perhaps, so antient as that of the dog, it is not surprising that they are also less variegated. Our domestic cats, though they differ in colour, form no distinct races. The climates of Spain and Syria have alone produced permanent varieties: To these may be added the climate of Pe-chi-ly in China, where the cats have long hair and pendulous ears, and are the favourites of the ladies [Hist. gen. des voyages, par M. l'Abbé Prevot, tom. 6, p10 ]. These domestic cats with pendulous ears, of which we have full descriptions, are still farther removed from the wild and primitive race, than those whose ears are erect.

We shall here terminate the history of the cat, and at the same time that of domestic animals. The horse, the ass, the ox, the sheep, the goat, the hog, the dog, and the cat, are our only domestic animals. We add not to this list, the camel, elephant, rain-deer [sic], &c. which, though domestic in other countries, are strangers to us; and we shall not treat of foreign animals, till we have given the history of the wild animals which are natives of our own climate. Besides, as the cat may be considered as only half-domestic, he forms the shade between domestic and wild animals; for we ought not to rank among domestics those troublesome neighbours, mice, rats, and moles, which, though they inhabit our houses and gardens, are perfectly wild and free. Instead of being attached or submissive to man, they fly from him, and preserve entire, in their obscure retreats, their manners, their habits, and their liberty.

SUPPLEMENT.

By mistaking some of my expressions in the above history of the cat, I find it has been imagined that I had denied him the power of sleeping altogether. I always knew that cats slept, but not so profoundly as I now find they sometimes do. On this subject M., Pasumot, of the academy of Dijon, an able naturalist, communicated to me a letter, of which the following is an extract.

"Permit me, Sir, to remark, that, in your work, you seen to deny the cat the power of sleeping. I assure you, that, though he sleeps seldom, his sleep is so profound, that it is a species of lethargy, which I have observed at least ten times in different cats. When young, a favourite cat lay every night in bed at my feet. One night, I pushed him from me; but I was surprised to find him so heavy, and at the same time so immoveable, that I believed him to be dead. I pulled him smartly with my hand; but I felt no motion. I then tossed him about, and, by the force of the agitation, he began slowly to awake. This profound sleep, and difficulty of wakening, I have frequently observed. It generally happened in the night, having only once observed it in the day; and this was after perusing what you have said concerning the sleep of these animals. I know another gentleman who has likewise often seen cats sleeping in this profound manner. He tells me, that, when cats sleep during the day, it is always at the time of the greatest heat, and particularly before the approach of stormy weather."

M. de Lestrée, a merchant of Chalons in Champagne, who is accustomed to allow cats to lie in his bed, remarks:

1. "That, when these animals purr, when they are tranquil, and appear to be sleeping, they sometimes make a long inspiration, which is followed by a strong expiration; and that, at this period, their breath has an odour which greatly resembles that of musk.

2. That, when surprised by a dog, or any other object which suddenly alarms them, they make a kind of hissing noise, which is accompanied with the same odour. This is not peculiar to the males; for I have remarked the same thing of both sexes, and of cats of all ages and colours."

From these facts, M. de Lestrée seems to think, that, in the breast or stomach of the cat, there are some vessels filled with an aromatic substance, the perfume of which issues from the mouth. But we discover nothing of this kind from anatomy.

I formerly remarked, that, in China, there were cats with pendulous ears. This variety is not found any where else, and perhaps it is an animal of a different species; for travellers, when mentioning an animal called Sumxu, which is entirely domestic, say, that they can compare it to nothing but the cat, with which it has a great resemblance. Its colour is black or yellow, and its hair very bright and glittering. The Chinese put silver collars about the necks of these animals, and render them extremely familiar. As they are not common, they give a high price, both on account of their beauty, and because they destroy rats [Journal des Savana, tom. 1. p261].

At Madagascar there are also wild cats rendered domestic. Most of them have twisted tails; and they are called Saca by the natives. But these wild cats are of the same species with the domestic kind; for they intermix and produce [Voy. de Flacourt, p152]

Another variety has been observed. In our own climate, cats are sometimes produced with pencils of hair at the points of their ears. M. de Seve writes me (Nov. 16. 1773), that a young cat was brought forth in house at Paris, of the same race with that we have called the Spanish cat, with pencils at the points of its ears, though neither of the parents had any pencils. In a few months, the pencils of this cat were as large, in proportion to its size, as those of the Canadian lynx.

The skin of an animal, which greatly resembles that of our wild cat, has been lately sent me from Cayenne. It is called Haïra in Guiana, where they eat its flesh, which is white and good; and hence we may presume, that, however similar to the cat, it belongs to a different species. But, perhaps the name haïra is improperly applied; for it is probably the same with taïra, which is not a cat, but a small martin, taken notice of in the last volume of this work.

Notes

The cat has six cutting teeth, and two canine in each jaw; five toes before, and four behind; sharp hooked claws, lodged in a sheath, that may be exerted or drawn in at pleasure; a round head, short visage, and rough tongue. The wild cat has long soft hair, of a yellowish white colour, mixed with grey; the grey is disposed in streaks, pointing downwards, and rising from a dusky list, which runs from head to tail, along the middle of the back; the tail is marked with alternate bars of black and white, and its tip, and the hind part of the legs, are black. It is three times as large as the domestic cat, and very strongly made; Pennant. synop. of quad. p183.

A cat's meat man, by royal appointment, in 1780.

" Travels Through the Southern Provinces of the Russian Empire in the Years 1793-1798" by P S Pallas

Published in in 1798 and translated into English in 1812, this describes colourpointed cats near the Caspian Sea.

The formal history of Siamese cats begins with their importation to Britain from Siam in 1884. There were at least three Siamese cats in Europe before that date. In a rare but classic travel book called " Travels Through the Southern Provinces of the Russian Empire in the Years 1793-1798" by P S Pallas, there is a description of a colourpointed cat accompanied by a coloured plate, that Pallas came across near the Caspian Sea. In the translation published in London in 1812. Pallas writes :

"A particular species of mongrel variety of the domestic cat engaged a considerable share of my attention. It was the offspring of a black which belonged to Yegor Michailovitch Shedrinskoi, Counsellor of State, and had kittened three young ones that exactly resembled each other. The mother lived alone in the village of Nikloskoi in the district of Insara, on this nobleman's estate and often returned to a young forest behind a garden which is laid out in the English style.

" The domestics had remarked that the cat was absent during the rutting season and it was also reputed that she formerly had kittens of the common kind which she devoured a few days after their birth. I saw two of her brood in the house of Counsellor Martyof and one in that of the Lord Lieutenant' The form of this cat and particularly the nature and colour of the hair exhibited so extraordinary an appearance that I was induced to give a report of it in the first plate.

"It is of a middle size, has somewhat smaller legs than the common cat and the head is longer towards the nose. The tail is thrice the length of the head. The colour of the body is a light chestnut brown like that of a polecat but blacker on the back, especially towards the tail and paler along the sides and belly. The throat is whiter and the female has a white spot on the lower part of the neck. A black streak runs along and surrounds the eyes and ends in front of the forehead. The ears, paws and tail are quite black. The hair, like that of the polecat. is softer than that of the common cat and the lower or furry part is of a whitish grey. The hair of the tail is somewhat elastic and lies flat in divisions.

"The exquisite olfactory sense, agility and other characteristics of these three animals are similar to those of the common cat, but they had been extremely wild at first, hid themselves in cellars and holes, nay' even burrowed underground and had not yet acquired the sociable qualities of our domestic cats. I shall not attempt to determine whether they may be considered as a mongrel breed."

The description is unmistakably that of a Siamese, but how could they appear so far from Siam at that time ? Pallas was a trained observer and was interested in cats, but his two large volumes contain no other reference to such cats. In 1952, Dr. Nora Archer suggested that that the " Siamese " in Southern Russia were the result of a (probably) male cat carrying the Siamese pattern escaping from a merchant's caravan and breeding with local cats. her other suggestion was that the mutation had occurred more than once.

Had Herr Pallas not been otherwise engaged, he might have imported those cats to the West, and the colourpoint cat might have been called Russian or Caspian rather than Siamese. Unfortunately the colour plates in the 1812 edition of the book are hand-coloured and the exact colouring of the cat varies in different volumes. However the " points " are unmistakable. In some copies of the book the cat is very much darker than modern Siamese (perhaps a Tonkinese?) while in the London Library copy it is light chestnut. The colourists responsible for the plates in London in 1812 would never have seen a "Siamese" and had to imagine what it looked like from the written description.

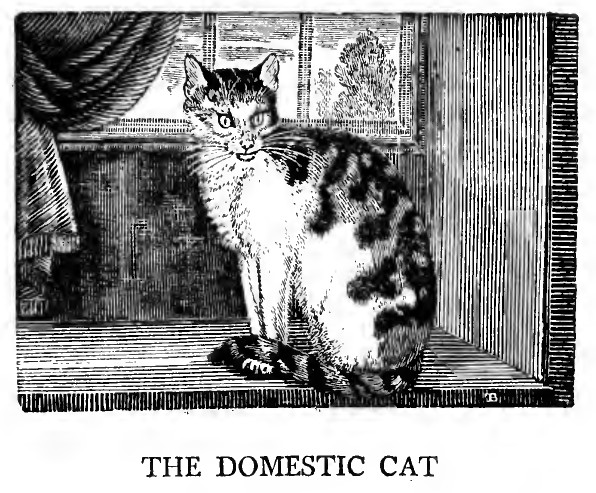

THE DOMESTIC CAT

A GENERAL HISTORY OF QUADRUPEDS (1792, 1803) BY THOMAS BEWICK

Differs from the Wild-Cat, In being somewhat less ; and, instead of being uniformly the same, is distinguished by a great variety of shades and colouring. To describe an animal so well known, might seem a superfluous talk : We shall only, therefore, select such of its peculiarities as are least obvious, and may have escaped the notice of inattentive observers.

It is generally remarked, that Cats can see in the dark ; but, though this is not absolutely the case, yet it is certain that they can see with much less light than most other animals, owing to the peculiar structure of their eyes, the pupils of which are capable of being contracted or dilated in proportion to the degree of light by which they are affected. The pupil of the Cat, during the day, is perpetually contracted ; and it is with difficulty that it can see by a strong light : But in the twilight, the pupil resumes its natural roundness, the animal enjoys perfect vision, and takes advantage of this superiority to discover and surprise its prey.

The cry of the Cat is loud, piercing, and clamorous ; and whether expressive of anger or of love, is equally violent and hideous. Its call may be heard at a great distance, and is so well known to the whole fraternity, that on some occasions several hundred Cats have been brought together from different parts. Invited by the piercing cries of distress from a suffering fellow-creature, they assemble in crouds -, and, with loud squalls and yells ; express their horrid sympathies. They frequently tear the miserable object to pieces ; and, with the most blind and furious rage, fall upon each other, killing and wounding indiscriminately, till there is scarcely one left. These terrible conflicts happen only in the night ; and, though rare, instances of very furious engagements are well authenticated.

The Cat is particularly averse to water, cold, and bad smells. It is fond of certain perfumes, but is more particularly attracted by the smell of valerian, marum, and cat-mint : It rubs itself against them ; and, if not prevented from coming at them in a garden where they are planted, would infallibly destroy them.

The Cat brings forth twice, and sometimes thrice, a year. The period of her gestation is fifty-five or fifty-fix days, and she generally produces five or fix at one litter. She conceals her kittens from the male, left he should devour them, as he is sometimes inclined , and, if apprehensive of being disturbed, will take them up in her mouth, and remove them one by one to a more secure retreat: Even the female herself, contrary to the established law of Nature, which binds the parent to its offspring by an almost indissoluble tie, is sometimes known to eat her own young the moment after she has produced them.

Though extremely useful in destroying the vermin that infest our houses, the Cat seems little attached to the persons of those who afford it protection. It seems to be under no subjection, and acts only for itself. All its views are confined to the place where it has been brought up ; if carried elsewhere, it seems lost and bewildered : Neither caresses nor attention can reconcile it to its new situation, and it frequently takes the first opportunity of escaping to its former haunts. Frequent instances are in our recollection, of Cats having returned to the place from whence they had been carried, though at many miles distance, and even across rivers, when they could not possibly have any knowledge of the road or situation that would apparently lead them to it. - This extraordinary faculty is, however, possessed in a much greater degree by Dogs ; yet it is in both animals equally wonderful and unaccountable.

In the time of Hoel the Good, King of Wales, who died in the year 948, laws were made as well to preserve, as to fix the different prices of animals ; among which the Cat was included, as being at that period of great importance, on account of its scarceness and utility. The price of a kitten before it could see was fixed at one penny ; till proof could be given of its having caught a mouse, two-pence ; after which it was rated at fourpence, which was a great sum in those days, when the value of specie was extremely high : It was likewise required, that it should be perfect in its senses of hearing and seeing, should be a good mouser, have its claws whole, and, if a female, be a careful nurse : If it failed in any of these good qualities, the seller was to forfeit to the buyer the third part of its value. - If any one should steal or kill the Cat that guarded the Prince's granary, he was either to forfeit a milch ewe, her fleece and lamb, or as much wheat as, when poured on the Cat suspended by its tail (its head touching the floor), would form a heap high enough to cover the tip of the former. – From hence we may conclude, that Cats were not originally natives of these islands ; and, from the great care taken to improve and preserve the breed of this prolific creature, we may suppose, were but little known at that period. - Whatever credit we may allow to the circumstances of the well-known story of Whittington and his Cat, it is another proof of the great value set upon this animal in former times.

MISCELLANEOUS NOTES

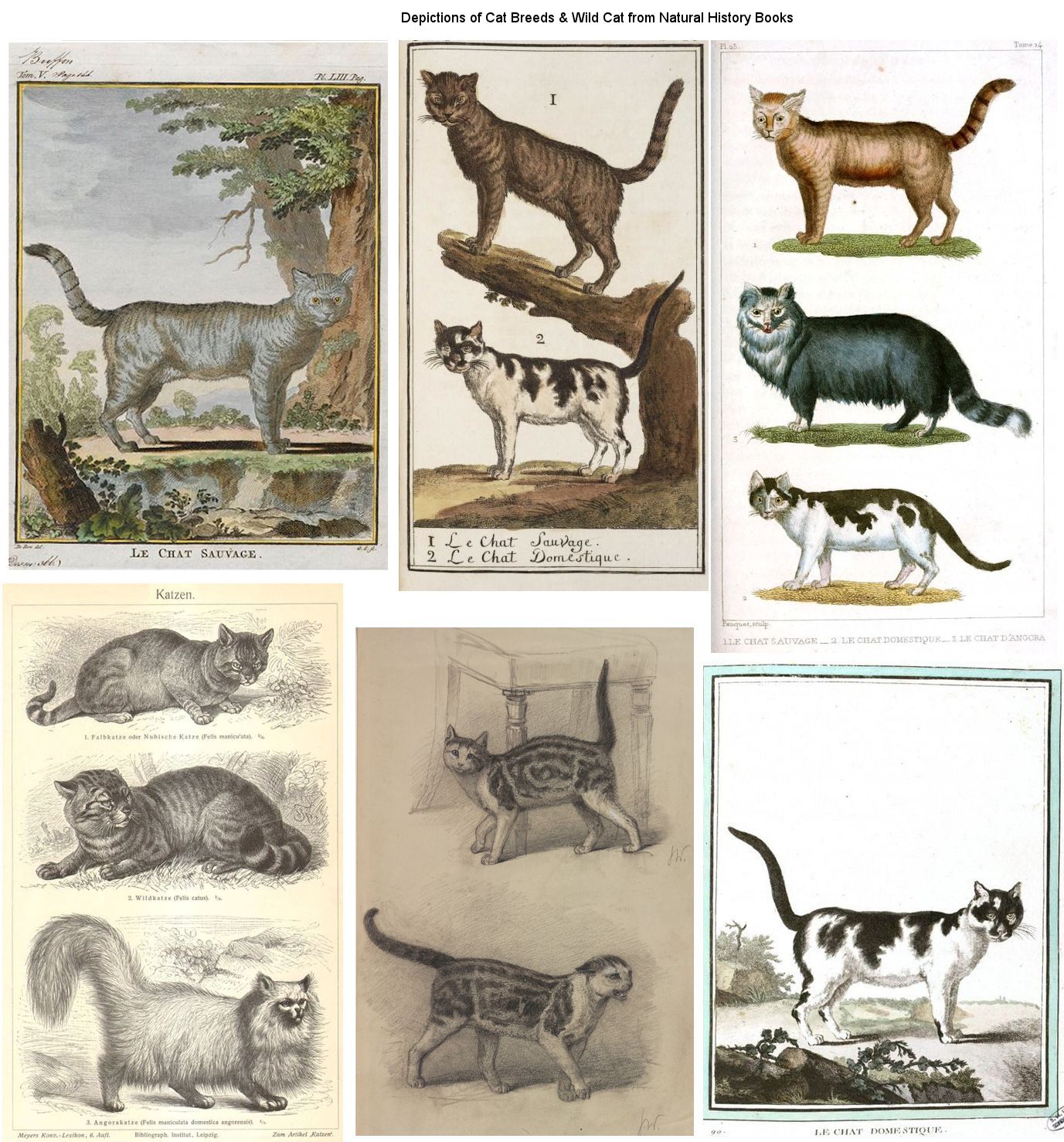

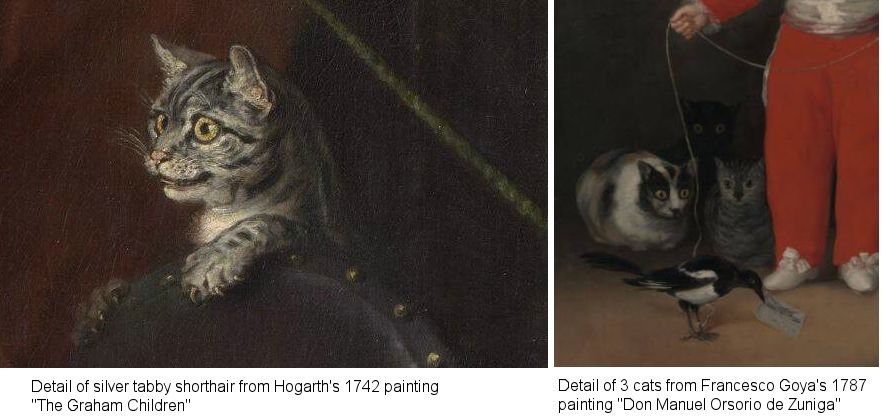

We tend to think of silver tabby shorthairs as a product of the 19th century cat fancy. here are 2 depictions from the 1700s, though we must allow for artistic licence. The first is Hogarth's 1742 painting "The Graham Children" which shows a yellow-eyed silver tabby climbing over the back of a chair. The second is Francesco Goya's 1787 painting "Don Manuel Orsorio de Zuniga" shows a tortoiseshell-and-white (calico) cat, a black cat and a blue/silver striped tabby, all with yellow eyes.

Excerpts from “THE NATURAL HISTORY OF SELBORNE”

By Gilbert White, 1770s, republished with annotations 1829

Letter XXIX - To Thomas Pennant, Esquire

Selborne, May 12, 1770.

Dear Sir,

Last month we had such a series of cold turbulent weather, [. . .] There is a propensity belonging to common house-cats that is very remarkable; I mean their violent fondness for fish, which appears to be their most favourite food: and yet nature in this instance seems to have planted in them an appetite that, unassisted, they know not how to gratify: for of all quadrupeds cats are the least disposed towards water; and will not, when they can avoid it, deign to wet a foot, much less to plunge into that element. [. . .]

Letter XXXIV - To The Honourable Daines Barrington

Selborne, May 9, 1776.

Dear Sir,

… admorunt ubera tigres.

We have remarked in a former letter how much incongruous animals, in a lonely state, may be attached to each other from a spirit of sociality; in this it may not be amiss to recount a different motive which has been known to create as strange a fondness.

My friend had a little helpless leveret brought to him, which the servants fed with milk in a spoon, and about the same time his cat kittened and the young were dispatched and buried. The hare was soon lost, and supposed to be gone the way of most foundlings, to be killed by some dog or cat. However, in about a fortnight, as the master was sitting in his garden in the dusk of the evening, he observed his cat, with tail erect, trotting towards him, and calling with little short inward notes of complacency, such as they use towards their kittens, and something gamboling after, which proved to be the leveret that the cat had supported with her milk, and continued to support with great affection.

Thus was a graminivorous animal nurtured by a carnivorous and predaceous one!

Why so cruel and sanguinary a beast as a cat, of the ferocious genus of Feles, the murium leo, as Linnaeus calls it, should be affected with any tenderness towards an animal which is its natural prey, is not so easy to determine.

This strange affection probably was occasioned by that desiderium, those tender maternal feelings, which the loss of her kittens had awakened in her breast; and by the complacency and ease she derived to herself from the procuring her teats to be drawn, which were too much distended with milk, till, from habit, she became as much delighted with this foundling as if it had been her real offspring.

This incident is no bad solution of that strange circumstance which grave historians as well as the poets assert, of exposed children being sometimes nurtured by female wild beasts that probably had lost their young. For it is not one whit more marvellous that Romulus and Remus, in their infant state, should be nursed by a she-wolf, than that a poor little sucking leveret should be fostered and cherished by a bloody grimalkin.

… viridi foetam Mavortis in antro

Procubuisse lupam: geminos huic ubera circum

Ludere pendentes pueros, et lambere matrem

Impavidos: illam tereti cervice reflexam

Mulcere alternos, et corpora fingere lingua.[1]

[1. 1 See Gilbert White's note on a Cat suckling three young Squirrels (Obs. on Quadrupeds). Sir William Jardine (ed. " Selborne," p. 209) writes : " " On the 27th of April 1820," writes Mr. Broderip in "Zoological Journal," "I saw a cat giving suck to five young rats and a kitten. The cat paid the same maternal attention to the young rats in licking them and dressing their fur as she did to her kitten, notwithstanding the great disparity in size.". [R. BOWDLER SHARPE.] ]

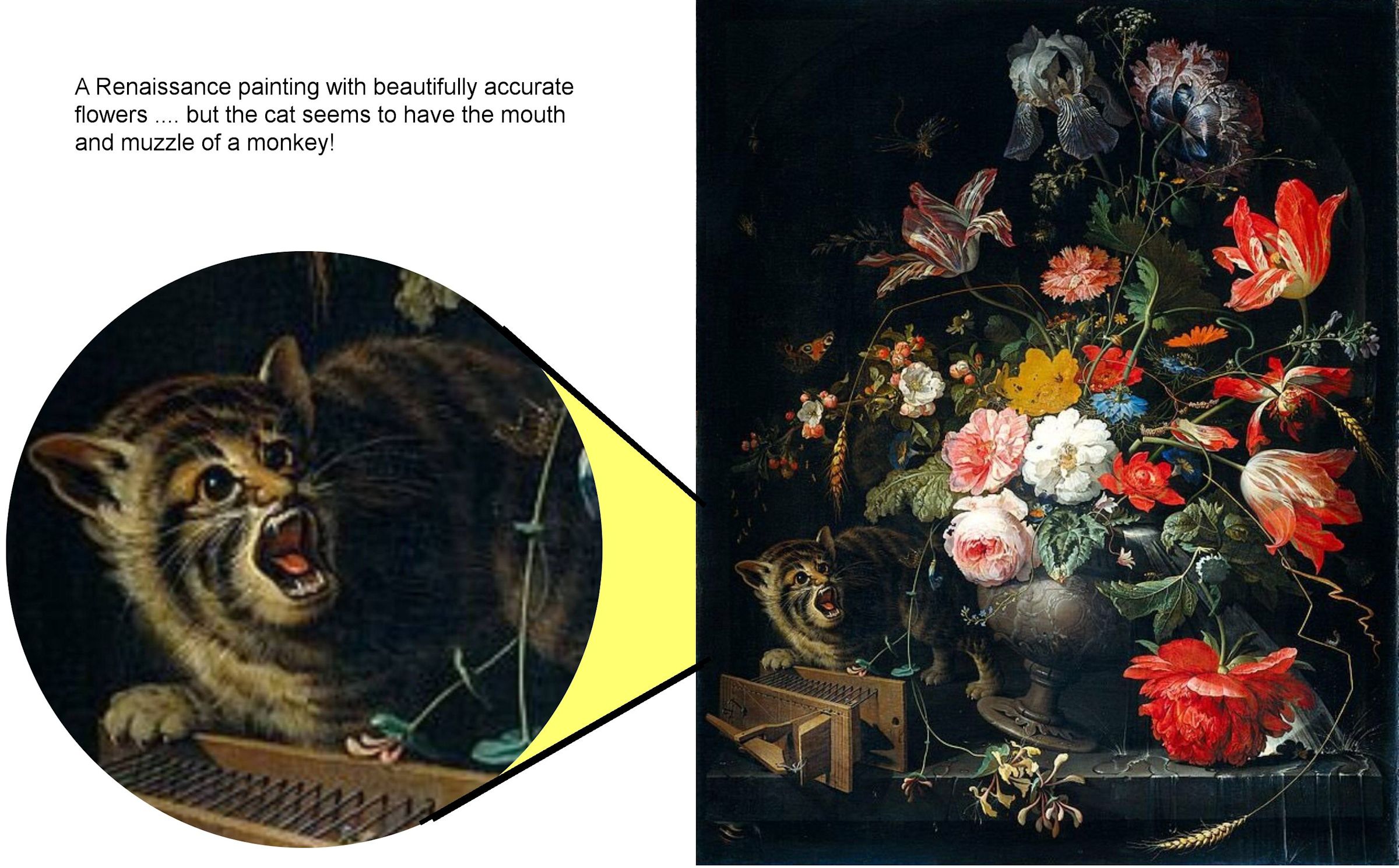

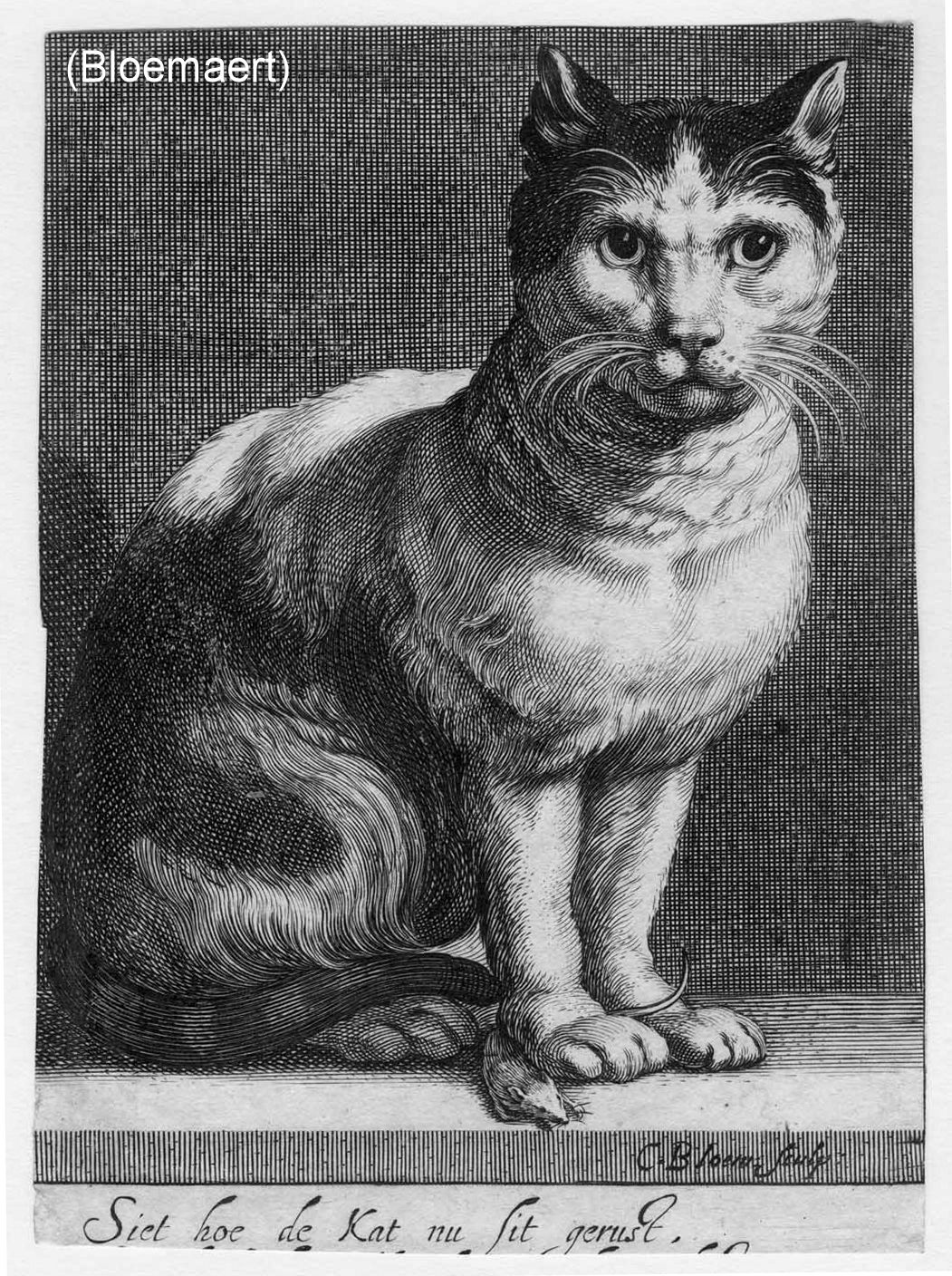

A PECULIAR RENAISSANCE PAINTING OF A TABBY CAT