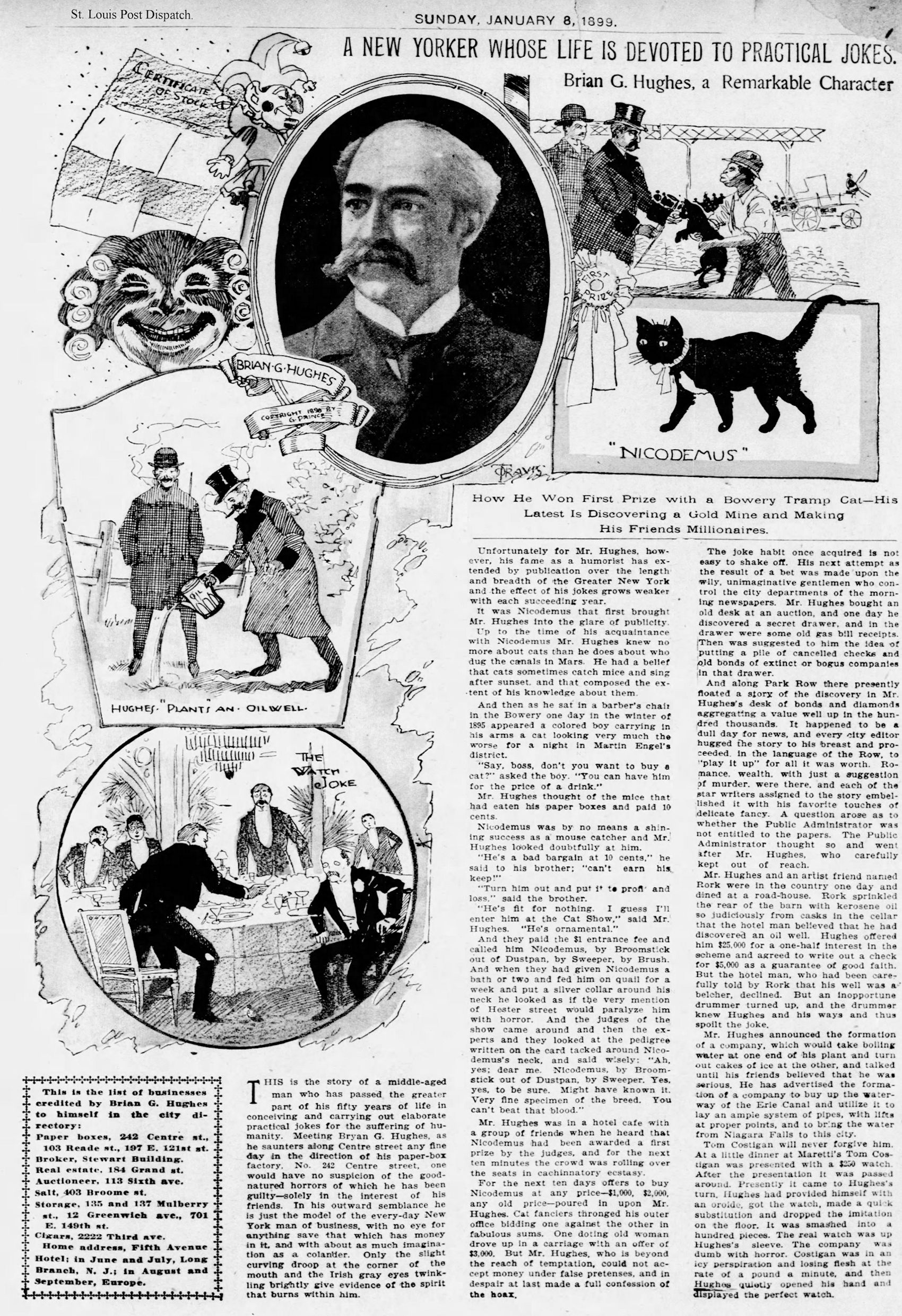

NICODEMUS – NEW YORK’S FAKE CHAMPION CAT OF THE 1890s

No history of American cat shows would be complete without a mention of “Nicodemus,” a prize-winning cat of an obscure breed that turned out to be a practical joke played by his owner, Mr. Brian Hughes. Hughes was a successful banker and cardboard box manufacturer and was a well-known practical joker. To give a little context to this tale, it happened at a time when American cat fanciers were hungry for new breeds to rival those at British shows. Australians (a breed now lost), Manxes, Angoras and Persians were arriving on American shores, and the newspapers carried reports of the Crystal Palace Cat Shows in London, so a “Dublin Brindle” breed was entirely plausible. In those early days of the western cat fancy, recognised breeds were still in their infancy and a great many cats were “foundation cats” having the right look, but lacking any pedigree, sometimes to the point of “unknown parentage”.

In 1895, Hughes purchased a dark grey cat for ten cents from a young bootblack on Hester Street. It was about to be drowned. Hughes said that he was attracted by the cat’s six toes and decided to keep it as a mouser at his cardboard box factory. The cat turned out to be a lousy mouser, but apparently held its head at an “aristocratic angle” so Hughes took it home, gave it a wash and brush-up and entered it in the National Cat Show as “Nicodemus, the last of the Dublin Brindle breed.”

Nicodemus was given a pedigree: Nicodemus, by Bowery, out of Dust-Pan, by Sweeper, by Ragtag-and-Bobtail . Other ancestors were Coleslaw, by Cabbage, and right back to a mummified Egyptian cat. These were plausible enough household pet nicknames in the 1890s. Hughes was wealthy enough to create an extravagant charade. Nicodemus was displayed on a silk cushion inside a gold-plated cage surrounded by roses and attended to by a “nurse.” Each day of the show, Sam Smith, an African-American livery footman delivered ice cream and chicken packed in the boxes of a celebrated caterer, and a florist delivered fresh flowers. According to The New York Times, one lady visitor commented that it was absurd for a cat to have its own nurse when so many children in the world did not receive half the amount of care and attention.

The early shows were run as “claiming shows,” and a value was set on each cat. Owners who wanted to sell their exhibit listed a reasonable price in the catalogue. Those who didn’t want to sell set a price that was out of reach. A percentage of the sale price went to the venue. In the catalogue, Nicodemus was valued at $1,000 and “Not For Sale.” $1,000 was roughly £200 in 1895. He won the $50 prize in the class for brown and dark grey tom cats, being the only prize-winner in this class. The high value set on the cat attracted attention – the public assumed the cat to be something really rare and special – and there were those who were willing to pay double that amount to acquire such a rarity, despite the risk that the cat might quickly succumb to “a fatal distemper” contracted at the show.

According to The Inter Ocean of May 23, 1895, Nicodemus, "the six-toed cat that took the first prize at the New York cat show, is a living warning to all wicked boys who have a weakness for testing the old tradition as to a cat having nine lives. Nicodemus was on his way to the dock in the arms of a bad boy, who proposed to drop him into the river, when a man ransomed him with a silver dime and sent him to the cat show. Since he secured the first prize he has been on exhibition in a dime museum, and $1,000 has been refused for him. Every bad boy who drops a cat into the lake should carefully consider the story of Nicodemus before he sacrifices the life of what may be the prize cat of the land."

The story was published in various newspapers during 1895, for example “Taken In By A Bogus Pedigree - Nicodemus,” the Pet of the Cat Show, Turns Out To Be an Ordinary Bowery Yowler” (various, New York, May 20, 1895). According to this report, Nicodemus had attracted the attention alike of experts and the public. He was backed by a pedigree “a yard long and quite as broad”, and was offered for sale, pedigree and all, for $1,000. It then transpired, says the report, that Nicodemus was a bogus nobleman whose owner, Brian G. Hughes, had entered him at the show for a joke. Mr. Hughes and his brother decided to invent a pedigree and enter Nicodemus at the Madison Square garden cat show, and the price tag and floral decorations meant their Hester street moggy did not seem at all out of place. As well as securing third prize, Nicodemus was coveted by fanciers, even at the large price of $1,000. After the show, Hughes was besieged by offers for his pet. Every mail delivery brought in a bid, some of which went up as high as $1,500, but though Hughes was a joker, he was not so dishonest as to sell his feline imposter. Finally, two ladies arrived at his house in a carriage and offered him $2,000 for the cat, and when he declined, they apparently increased their offer and he said he wouldn’t part with his cat at any price. Deciding it was time to put an end to the monetary offers from covetous cat fanciers, he owned up that he had “humbugged the public $2,000 worth by an outlay of just 10 cents worth of Hester street cat.”

Several papers also ran a short report on the gullibility of the public who tested the “Honesty of a Man Who was Offered Two Thousand Dollars for a Ten-Cent Cat.” They noted that the pedigree showed that Nicodemus was “descended from a cat the mummy of which was found in an Egyptian tomb,” a claim that should have rung immediate alarm bells since pedigree recording dated back to the 1870s. “The confession of Mr. Hughes, who makes paper boxes in a wholesale manner at 242 Centre street and resides at 49 East One Hundred and Twenty-sixth street, shows, first, that he is an honest man, and, secondly, that New York is full of gullible people.” Hughes had bought the cat from a bootblack who’d been instructed to drown it by a Hester-street woman. He’d taken it to be a mouser in his mouse-infested factory/shop, and, as a joke” Hughes and his brother concluded to send him to the cat show, putting up a long pedigree, which they made up as they went along. They tacked the pedigree on the cage, along with a tag fixing the price at $1,000, and nature and gullibility did the rest.”

The Hawaiian star of June 1, 1895, was a little more charitable towards the public, stating “The innocence of the general public is strikingly illustrated by a happening of the great cat show just closed in New York,” and concluded it was “shown as a joke because he was too lazy to hunt rats.”

To his credit, Hughes never succumbed to the lure of big money for his factory cat. Had he done so, his reputation, and his business, would have suffered. For Hughes, there was greater value in poking fun at people who were taken in by seeing a highly priced commodity. However, Nicodemus would be back the following year, proving that memories were short and lessons had not been learn by the supposedly learned men promoting the show. The famous author Rush S Huidekoper was left red-faced and his failure to detect the imposter. It is also reported that Hughes entered that rarest of creatures, a tortie tom cat in the show, but that the cat inconveniently produced two kittens, undoing his ruse, and that he had entered a one-eyed Tom in a class for Tabbies (females), though I haven’t yet found the official reports of these.

The following report in the New York Times describes Nicodemus’s role in the 1896 show:

NICODEMUS THE JOKE OF THE SHOW. Nicodemus continues to occupy his cage at the extreme southwest corner of the lines of benches, and rather revels in the fact that he, she, or it, is the biggest joke of the show, and is rather tending to make a huge joke of the pedigree cat business. Nicodemus is decidedly the unknown quantity among cats, and Dr. Huidekoper and T. Farrar Rackham, the judges now have to submit to a deal of chafing, all because of a mistake they have made about this " Chimmie Fadden ” cat. A year ago Nicodemus was also given a prize, and it now appears that the feline in question has been sailing under false colors ever since it flashed on the horizon of catdom with a fairy story about being royally bred and with a pedigree as long as one's arm. Nicodemus, so far as is known, never had a pedigree, and how the animal came to be made famous is a part of the gigantic joke which the owner has played on the judges and the alleged cat experts. Nicodemus had been a common every-day Bowery cat until one day, when Brian G. Hughes was getting his shoes shined at the stand of an Italian. Hughes took a fancy to the cat and the Italian owner of the boot-blacking stand was very ready to part with him for a few small coins. This was just before the last cat show, and Mr. Hughes decided to have some fun with the cat. So this midnight prowler of the Bowery was brushed up, that pedigree, long and wondrous, and scintillating, was constructed for the animal - and so it was sent to the show labelled Nicodemus, when it should have been labelled Fanny, or some such feminine name.

To carry out the joke the price of the cat was put at $2,500 [an exaggeration!], and that sum still figures in the official catalogues as the price at which the owner holds the common Bowery feline. Mr. Hughes was astonished that the cat should be able to capture a prize, but he kept his own counsel and entered the cat under about the same conditions again this year. Once more the misnamed feline captured a prize as a Thomas cat when it should have been hustling about among the Marias. That the cat should have gone through two campaigns without its sex being discovered was a bit too good a joke to be kept by the owner for another year, and so he gave the facts away. Those facts had not generally leaked out yesterday or Nicodemus would have been more of a lion than she now is. Dr. Huidekoper is a large man and a powerful one. Those who are discreet will refrain from saying “Nicodemus" in his presence, unless they are very much larger and more powerful than the doctor. The fact of the discovered change in the sex of Nicodemus was made a part of the official records of the show yesterday, when the prize that had been awarded to Nicodemus was declared to be withheld. - The New York Times, March 6th, 1896

The unmasking of Nicodemus was reported in The Times (NY) of Saturday March 7th, 1896:

NICODEMUS. There was a humorous incident at the cat show which has been in progress in Madison Square Garden this week. It happened thusly: There was a class for “he” cats with short hair. In this class were two entries, one named Nicodemus, the other Dot. The latter was disqualified by the judges because he had white whiskers, which was not allowable according to the conditions. As there were only two entries the first and second prizes were withheld and the third was awarded to Nicodemus. Everything was all right for a couple of days, when a protest was lodged by the owner of Dot against Nicodemus getting third prize. The committee had the owner of Dot on the carpet and asked him why he protested.

“The class calls for he cats, don’t it?" said the owner of Dot.

“It does,” replied the committee in chorus.

“Well, Nicodemus is not that kind of a cat.”

The committee looked surprised and the judges pooh-poohed.

“Come and see for yourselves,” said the owner of Dot.

Forthwith the committee attended the inspection in a body. One of the judges looked over Nicodemus critically, and there, sure enough, Nicodemus was discovered to be of the feminine gender. The committee was somewhat amused at the mistake, and of course disqualified Nicodemus. One of the judges was the well-known Dr. Huidekoper, the other Mr. Rackham. The laugh was on the judges. The mistake, however, might happen to any judge at a cat show, because some of the animals are so savage that it is dangerous to handle them. At least, this is the excuse handed out to the press by the management.

That Nicodemus had been unmasked was a good thing really, because she did not take to cat show life and he escaped on the final day of the show, thankfully reappearing at Hughes’ Center Street market offices a few days later. While Nicodemus may have retired, Hughes was not yet done with poking fun at early fanciers. He formulated an elaborate hoax for the 1899 International Cat Show at the Grand Central Palace.

Not all cats exhibited at those early shows were there because of their pedigree. Some were there as curiosities or celebrities. Medical curiosities were routinely exhibited, as were cats that had survived adverse circumstances. Hairless cats had been exhibited, as had six-legged cats, three-legged cats (one with a wooden leg) and other oddities. The public seemed even more entranced by tales of cats that had crossed the ocean or had accompanied their owners the length and breadth of the USA. The successor to Nicodemus combined a freakish appearance with a life story straight out of a boys’ adventure magazine.

Under the pseudonym “Nairb G. Sehguh” (his name backwards) Hughes exhibited a cat named “Eulata,” whom he alleged had been a mascot on the Spanish ship Vizcaya during the Spanish-American War and had been owned by no less a person than the King of Spain. Eulata had allegedly been presented to the King of Spain by a Bombay merchant, before being presented to Captain Don Antonio Eulate of the Vizcaya. According to his yarn, Eulata was a native of Hindustan. When the Vizcaya was sunk in 1898, she swam to the USS Oregon and was rescued by sailors. This was all entirely plausible because shipwrecked cats had been exhibited as celebrities at much earlier shows. Since no-one knew what a Hindustan cat should look like, she had been completely shaved, except for her head and tail-tip, giving her an exotic appearance never before seen by cat show judges.

WONDERFUL CAT SHOW (Logansport Tribune, Feb 1, 1899, taken from the New York Sun). Brian Hughes’ Joke Cat Eulata. The Viscaya’s Mascot Appears As A Shaven Nondescript. Mr. Nairb Sehguh has a wild and weird exhibit in the cat show at the Grand Central palace in New York. Mr. Sehguh spells his name Brian G. Hughes except when he has a joke buzzing in his bonnet. Then he turns his name around and chortles over the signature of Sehguh. Mr. Sehguh has always had a weakness for playing his jokes on the managers of cat shows, and the people in charge of the present one have been lying awake nights so as not to be caught napping by Brian. Now that Mr. Sehguh’s plans have materialized the managers are doing some of the chortling themselves and are praying for an epidemic of practical joking like unto this.

Sehguh has sent a cat to the show. He had intimated that he wanted to furnish an entry, but the wildest dreams of the management had not pictured anything approaching what has happened. Sehguh’s cat arrived in a large cage, which was elaborately gilded and silvered. It was wreathed with smilax and festooned with fresh roses, violets, carnations and hyacinths. The floor of the cage was covered with velvet carpet, and at one end a box filled with pale blue cotton wool served as a luxurious couch for the occupant A silver bowl was filled with water for Eulata — that being the cat's name — and a silver comb and brush, as well as a fine tooth-brush, were laid neatly side by side for use in making the toilet of the pampered cat. There was also a bottle of violet perfume and an atomizer for spraying said perfume over the whole outfit. [note: people went to “See Eulata” – “See you later”]

As for the cat itself it was one the like of which was never seen on sea or land nor yet on an alley fence. It was shaved closely except for the head and the very tip of the tail and looked more like a hairless dog than almost anything else. A quartet of attendants arrived with the cage and a colored man is always on hand to look after the animal, or rather to help carry out the Sehguh joke. On top of the cage is a doll, a trunk labeled “Eulata,” a cat made of red and yellow immortelles, the American and Spanish flags, and a box of food labeled “From Sherry’s.” The colored attendant distributes circulars which read as follows:

“Eulata, mascote del Vizcaya.” Was presented to Captain Eulate of the Vizcaya by the boy king of Spain, to whom it had been sent by a Bombay merchant, it being one of an almost extinct species of Hindustan, India. She was named Eulata and looked upon as a mascot until the vessel went down with the others of Cervera’is fleet on the memorable 3d of July, l She swam to the Oregon, was handed aboard by one of the crew, from whom she was purchased by her present owner, Nairb G. Sehguh of New York. For sale: price. $3,000.

During the show, Eulata was displayed in a splendid gilded cage, ate out of silver dishes, slept on velvet cushions, and was periodically sprayed with violet perfume, though quite what she thought of that last indignity is not recorded. Her cage was covered with fresh roses, violets, hyacinths, and carnations alongside the American and Spanish flags. To complete the theatrical appearance, there was a doll’s cabin trunk labelled “Eulata,” and a box of food stamped “Sherry’s.” This time, the judges cottoned on to Hughes’ style and to his pseudonym. While Eulata may not have fooled the judges, Hughes succeeded in entertaining the public and poking a little fun at the establishment who were then foremost in the cat fancy. With his jokes now known to the organisers of cat shows, Hughes turned his attention to horse shows where he entered a former tram-horse under the name “Puldeka” (Pulled a car).

GULLIBILITY OF JUDGES. Belfast Telegraph, 22nd December 1924

America's great practical joker, Mr. Brian G. Hughes, has just died at the age of 75, of apoplexy. In his lifetime be often caused a near approach to apoplexy in the victims of his jokes. He had an amazing ability for showing up the gullibility of the world, and a passion for making solemn and self-important personages appear ridiculous. He was a successful banker and box manufacturer of New York. and he spent large sums to carry out some of his hoaxes. His most famous and successful joke (states the "Daily Express" New York correspondent) was at the expense of the National Cat Show, which some years ago was an annual social affair, at Madison Square Garden, New York. Mr. Hughes found a stray cat in the street a short time before the show opened. He carefully cleaned and groomed the animal, and wrote a long pedigree of its descent from the royal cats of the Shah of Persia. He had an elaborate cat house constructed, covered with rosettes pretending to represent prizes the cat had won in Europe. He entered the cat in the name of a Persian. Every day during the show, a liveried servant appeared at the show with cream and chicken to feed the cat. The impression created was enormous, and when the judges made their awards Mr Hughes’ stray tow won a first prize.