THE DOMESTIC CAT

By Gordon Stables

1876

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE. CLASSIFICATION: ITS BASIS.

CHAPTER TWO. BREEDS AND CLASSES.

CHAPTER THREE. BREEDS AND CLASSES. THE TORTOISESHELL.

CHAPTER FOUR. THE BLACK CAT.

CHAPTER FIVE. THE BLACK-AND-WHITE CAT AND THE PURE WHITE.

CHAPTER SIX. THE BLUE CAT; AND TABBIES—RED, BROWN, SPOTTED, AND SILVER.

CHAPTER SEVEN. ASIATIC CATS.

CHAPTER EIGHT. ON DIET, DRINK, AND HOUSING.

CHAPTER NINE. THE DISEASES OF CATS.

CHAPTER TEN. DISEASES OF CATS — CONTINUED.

CHAPTER ELEVEN. TRICKS AND TRAINING.

CHAPTER TWELVE. AGRÉMENS OF CAT LIFE.

CHAPTER THIRTEEN. SAGACITY OF THE CAT.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN. CATS FEEDING THE SICK.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN. TOM, TIMBY, AND TOM BRANDY.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN. SOME TRAITS OF FELINE CHARACTER.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN. LOVE OF CHILDREN AND AFFECTION FOR OWNER.

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN. HINTS UPON BREEDING AND REARING CATS FOR EXHIBITION, AND A WORD ABOUT CAT-SHOWS.

CHAPTER NINETEEN. ON CRUELTY TO CATS.

CHAPTER TWENTY. PUSSY’S TRICKS AND MANNERS.

CHAPTER TWENTY ONE. THE FIRESIDE FAVOURITE.

CHAPTER TWENTY TWO. THE DUNGHILL CAT.

CHAPTER ONE. CLASSIFICATION: ITS BASIS.

In the feline world you find no such diversity, of form, shape, disposition, coat, size, etc, as you do in the canine. Dogs differ from each other in both the size and conformation of the skeleton, and in many other important points, almost as much as if they belonged to entirely different species. Mark, for instance, how unlike the bulldog is to the greyhound, or the Scotch toy-terrier to the English mastiff; yet, from the toy-terrier upwards to the giant Saint Bernard, they are all dogs, every one of them. So is the jackal, so is the fox and the wolf. The domesticated dog himself, indeed, is the best judge as to whether any given animal belongs to his own species or not. I have taken dogs to different zoological gardens, and have always found that they were ready enough to hob-nob with either jackal or fox, if the latter were only decently civil; but they will turn away with indifference, or even abhorrence, from a wild goat or sloth. But among the various breeds of cats there exists no such characteristic differences, so that in proposing a classification one almost hesitates to use the word “breed” at all, and feels inclined to search about for another and better term. If I were not under a vow not to let my imagination run riot in these papers, but to glide gently over the surface of things, rather than be erudite, philosophical, theoretical, or speculative, I should feel sorely tempted to pause here for a moment, and ask myself the question—Why are there so many distinct breeds of the domesticated dog, and, properly speaking, only one of the more humble cat? Did the former all spring from the same original stock, or are certain breeds, such as the staghound, etc, more directly descended from the wolf, the collie, Pomeranian, etc, from the fox after his kind, and other breeds from animals now entirely extinct in the wild state? And once upon a time, as the fairy books say, did flocks of wolves, foxes, wild mastiffs, and all dogs run at large in these islands, clubbing together in warlike and predatory bands, each after his kind, much in the same way that the Scottish Highlanders used to do two or three hundred years ago? Animals of the dog kind are a step or two more advanced in civilisation, if I may be allowed to use the term, than cats; and hence, as intelligence can appreciate intelligence, and always seeks to rise to a higher level, more breeds, or a larger number of species, of the former than of the latter have forsaken their wild or natural condition to attach themselves to man. May not the time come, in the distant future, when a larger variety of feline animals shall become fashionable—when domesticated tigers, tame lions, or pet ocelots shall be the rage? If so, that will indeed be the millennium for cats. Just fancy how becoming it would be to meet the lovely and accomplished Miss De Dear out walking, and leading a beautiful leopard by a slight silver chain, or Lady Bluesock in her phaeton, with a tame ocelot beside John on the dickey! A lady beside a lion on the lawn would, I think, make a prettier picture than one by the side of a peacock, and a tame Bengalese tiger would be a pet worthy to crouch at the foot of a throne. To be sure, little bits of mistakes would occur at times; instead of the pussy of the period bolting away with the canary, nothing less would satisfy the pet than a nice fat baby, and then those extraordinary people the cat—exterminators would be louder in their denunciations than ever.

If we dissect the cat, we will find that the skeleton of one breed of pussy would pretty nearly pass for that of another; we find the same shape and almost the same size of bones, the same arrangement of teeth as regards their levelness, the same number of teeth, and the same formation of jawbone. Clothe that skeleton with muscle, and still you can hardly tell the breed of the cat, for scarcely will you be able to find a muscle in the one breed that has not its fellow in all, a little difference perhaps in the size and development of one or two, but even this more the result of accident and use than a distinction real and natural.

I feel as I write that I am sailing as close to a wind as possible; I am luffing all my ship will steer; were I to keep her away a single point, I should drift down into the pleasant gulf-stream of comparative anatomy, and thence away and away to the broad enchanted ocean of speculative theory. And I confess, too, I wouldn’t mind a cruise or two in those latitudes, did space and time admit of it.

Now, I do not mean to say that there is really no difference in shape and form between the different breeds of the domestic cat, but rather that this difference is so minute, compared to that which exists between dogs, that the term “breeds” seems almost a misnomer as applied to cats. It is only when you see pussy arrayed in all the wealth and beauty of her lovely fur, that you can see any real distinction between her and another.

In regard to the origin of the domestic cat, naturalists have squabbled and fought for centuries, and the best thing possible, I think, is for every man steadfastly to retain his own opinion, then everybody is sure to be right. For myself, I really cannot see that it would either assist us in breeding better cats, or render us a bit more humane in our treatment of the pretty animal, to be assured that she was first imported into this country from Egypt or Persia in the year one thousand and ever so much before Christ, or that the father of all the cats was a Scottish wild cat, captured and tamed by some old Highland witch-wife a thousand years before the birth of Noah’s grandfather. What matters it to us whether the pussy that purrs on our footstool is a polecat bred bigger, or a Polar bear bred less? There she is,—

The rank is but the guinea stamp,

And a cat’s a cat for a’ that.

But, and if, you are fond of pedigree, why then surely it ought to satisfy you to know that, ages before your ancestors or mine could distinguish between a B and a bull, pussy was the pet of Persian princes, the idol of many a harem, and the playmate of many a juvenile Pharaoh. What classification, then, are we to make of cats? We search around us in vain for something to guide us; then, fairly on our beam-ends, are fain to clutch at the only solution to the question, and fall back upon coat and colour, with some few distinctive points of difference in the size and shape of the skull and body. Colour or markings, then, and quality of coat, are the guiding distinctions between one breed of cat and another; and to these we add, as auxiliaries, size and shape.

Colour.—Whether we understand it or not, there, undoubtedly, is nothing in this world left to chance alone, and nothing, I sincerely believe, is done by Nature without a purpose. The same merciful Providence that clothes the lambs with wool, the reason for which we can understand, paints the rose’s petal, the pigeon’s breast, or even the robin’s egg, for reasons which to us are inscrutable, or only to be vaguely guessed at. We can tell the “why” and the “wherefore” of the rainbow’s evanescent hues, but who shall investigate the laws that determine the fixed colours of the animal and vegetable creation? Who shall tell us why the grass is green, the rose is red, that bullfinch on the pear-tree so glorious in his gaudiness, and that sparrow so humble in his coat of brown?

If we ask the Christian philosopher, he will tell us that the colours in animated nature are traced by the finger of God, who always paints the coat or skin of an animal with that tint or hue, which shall tend most to the propagation and preservation of its species. That He clothes the hare and rabbit in a suit of humble brown, that they may be less easily seen by the eye of the sportsman, or their natural enemies, the polecat, weasel, white owl, or golden-headed eagle. That birds—who flit about all summer in coats so gay and jackets so gaudy, that even a hawk may mistake them for bouquets of flowers, and think them not worth eating—as soon as the breeding season is over, and the leaves and flowers fade and fall, are presented by nature with warmer but more homely suits of apparel, more akin in colour to the leafless hedgerows, or the brown of the rustling beech leaves, among which they seek shelter from the wintry blast. If you go farther you may fare worse. No one in the world can be a greater admirer than I of the genius of Tyndall, Darwin, or Huxley, but I must confess they get a little, just a leetle, “mixed” at times; and I doubt if Darwin himself, or any other sublunarian whatever, understands his (Darwin’s) theory of colour. He says, for instance—I can’t use the exact words, but can give his meaning in my own—that the wild rabbit or the hare was not painted by the finger of nature the colour we find them with any pre-defined idea of protecting the animal against its enemies; but that in the struggle for life that has been going on for aeons, considering the conditions of its surroundings, it was only the grey rabbit that had the power of continuing in existence, escaping its enemies by aid of its dusky coat. Darwin thinks, indeed, that religionists put the cart before the horse, to use a homely phrase. I confess that I myself prefer the good old theory of design—of a God of design, and a prescient Providence. I believe the testimony of the rocks, I believe to a great extent in evolution—it is a grand theory, and one which gives the Creator an immensity of glory—but I cannot let any one rob me of the belief that beauty and colour are not all chance.

Yonder is a hornet, just alighted at the foot of the old oak-tree where I am writing, so uncomfortably near my nose, indeed, that I can’t help wishing he had kept to his nest for another month; but the same April sunshine that lured me out of doors lured the hornet, and there it stands, all a-quiver with delight, on a budding acorn, looking every moment as if it would part amidships. “Do you think, Mrs Hornet, O thou tigress of bees, if your lovely body, with its bars of gold, had been of any other colour, that, under the peculiar conditions in which your ancestors lived, you would, ages ago, have ceased to exist; that ants, or other ‘crawling ferlies,’ who detest the colour of turmeric, would, in spite of your ugly sting, have devoured you and yours?”

Yonder, again, is a beautiful chaffinch; he was very glad to come to my lawn-window every day, during all the weary winter, to beg a crumb of bread. He forgets that now, or thinks perhaps that I do not know him in his spring suit of clothes, and golden-braided coat and vest. But I do, and I still believe—simple though the belief may be—that the same Being, who gave life and motion to that little beetle which is now making its way to the highest pinnacle of my note-book, as proud as a boy with a new kite, to try its wings for the first time, tipped that ungrateful finch’s feathers with crimson, white, and gold, in order to make him more attractive to his little dowdy thing of a wife, who has been so busy all the morning building her nest on the silver birch, and trying to find lichens to match the colour of the tree. For Mrs Finch is a nervous, timid little body, and had no thoughts of marrying at all, and indeed would have preferred to remain single, and would have so remained, had she not been a female; but being a female, how could she resist that splendid uniform?

I go into the garden and bend me over the crocus beds—white crocuses, orange crocuses, and blue, all smiling in the sunshine of spring. Each is a little family in itself, and they would like to know each other too so very much, for they have ever so many love tales to breathe into each other’s ears. But they are all fast by one end and cannot move. Whatever shall they do, and what will become of the next generation of crocuses? I can hear them whispering their tales of love to the passing wind, and so can you if you are a lover of Nature; but the wind is too busy, or too light, or too something or another, and cannot pause to listen. So the little things are all in despair, when past comes a bee. Now bees, and butterflies too, for all they have got so many eyes, are rather short-sighted, but even a bee cannot help seeing that gorgeous display of orange, white, and blue, so he pops at once into the bosom of a blue crocus, and is made as welcome as the flowers in May.

“Oh! you dear old bee,” says the crocus, “you’re just come in time; have something to eat first. I have a nice little store of honey for you; and then you shall bear a message to my lady-love—the pretty blue belle crocus mind, not the white. I wouldn’t have a race of variegated children for the world.”

“All right,” says the bee, and away he flies with the message of love to the blue belle crocus, and thus the loves of the crocuses are cemented. They tell the old, old story by proxy, because they can’t do it as you or I do, reader, eye to eye and lip to lip.

For colour has its uses, and nothing that exists was made in vain, although some are selfish enough to believe that all the colour and beauty they see around them, during a ramble in the country, was made but to please the eye of man.

Colour I believe to be connected in some way with the mystery of heat and life. We all know that certain colours will dispel or retain heat; black is more warm, for instance, than white. There may be, then, a scale of colours as it were, each colour differing in the amount of heat-retaining power; and, it may be that, having reference to this scale, the colours on an animal’s coat, are apportioned to it in the way which shall best conduce to its health, comfort, and happiness.

The colour of any animal is an important consideration in determining its breed, and this is especially the case among cats, where indeed it forms the basis of our classification. Colour is often the key to the character of the cat—to its temper, whether savage or good-natured; to its qualities as a good hunter or the reverse; and to its power of endurance, its eyesight, and its hearing.

Size.—Cats of different breeds—I use the word for want of a better—are generally of different sizes, and the skeleton is, as a rule, larger in some breeds than in others. The male ought to be larger than the female.

Form.—The difference in form is principally observable in the shape and rotundity of skull, the length and shape of the nasal bones and jaw, and the length of the tail and its form at the point. The ears also vary a good deal in length in the different breeds, and also in breadth, and in “sit” or position.

Pelage, or Coat.—The coat is of two different kinds, the long and the short. In the former, the longer and softer and silkier the better, and in the latter the length of the hairs, their closeness and glossiness, are to be taken into consideration. You can generally tell by one glance at the animal’s coat how she is fed, how she is treated and housed, and the condition of her health.

Having got so far, we will next bring pussy herself on the stage, and see how far these remarks apply to her, according to her breed and species.

CHAPTER TWO. BREEDS AND CLASSES.

In future chapters I will give the habits and characteristics of the domestic cat in general, with some specialities of a few of the different kinds in particular. The “tricks and manners” of one cat, however, will be found to correspond pretty closely with those of any other.

But before going farther on with this chapter, I wish to make a plea in pussy’s favour. I myself have studied cat life, off and on, for twenty years, so I suppose it will be admitted I am no mean authority on the subject. During that time I have come to certain conclusions, which in some cases run contrary to the opinions generally conceived of those animals—contrary, at any rate, to the belief current some years ago, before pussy was thought worthy to hold a show of her own. Towards this ocean of contrary opinions I have been wafted, not by the wind of my own sails alone, but aided and supported by many hundreds of anecdotes of domestic pussy’s daily life, habits, likes and dislikes. These anecdotes have been supplied to me from trustworthy people, in every position of life—from the poverty-stricken old maid with her one feline favourite; from the honest working-man with his fireside pet and children’s playmate; from farmers, solicitors, doctors, and parsons; from baronets’ ladies; and, in more than one instance, from the daughters of peers of the realm, allied to royalty itself. These anecdotes have, in almost every case, been substantially authenticated, and always discarded wherever, in any case, they were open to doubt.

From these anecdotes and essays, and from my own experience as well, I have arrived at the following conclusions—and be it remembered I speak of cats that are properly fed and housed, and have been taught habits of cleanliness when kittens:—

1. That cats are extremely sagacious.

2 That cats are cleanly and regular in their habits.

3. That cats are fond of children.

4. That cats are excellent mothers, and will nurse the young of any small animal on the loss of their own.

5. That cats are fond of roaming abroad.

6. That cats are brave to a fault.

7. That cats are fond of other animals as playmates.

8. That cats are easily taught tricks.

9. That cats are excellent hunters.

10. That cats are good fishers, and can swim on occasion.

11. That cats are very tenacious of life.

12. That cats are fond of home.

13. That cats are fonder far of master or mistress.

14. That cats are not, as a rule, thieves, but the reverse.

15. That long-headed, sharp-nosed cats are the best mousers.

These are not texts, but deductions.

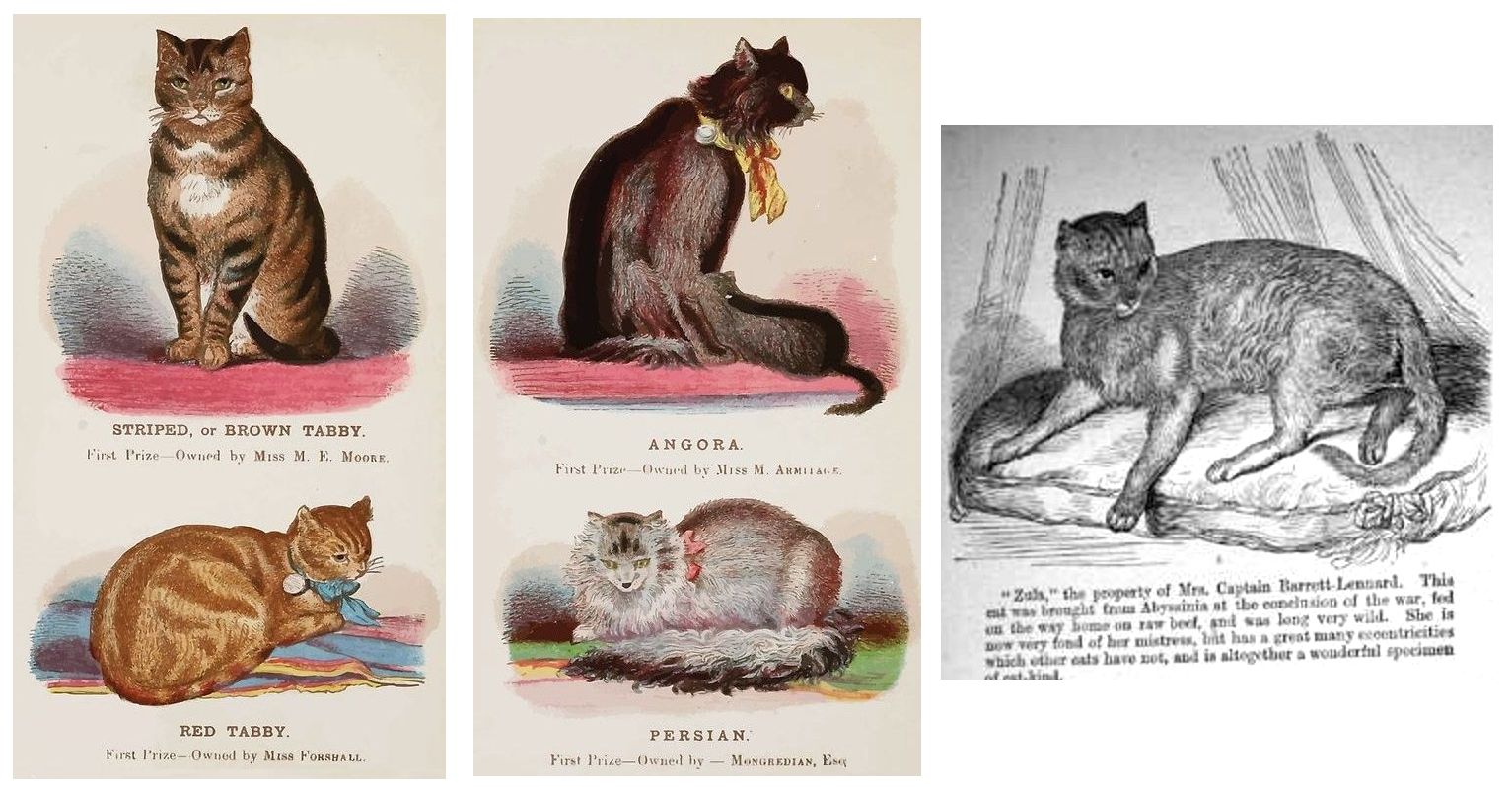

All that is known for certain of the origin of the domestic cat may be expressed in three letters, n i l—nil. And, after all, I cannot see that it matters very much, for if the theory of Darwin be correct, that everything living sprang originally from the primordial cell, then cats or dogs, or human beings, we all had the same origin. But, again, according to Darwin, the cat is an older animal than man in the world’s history; and if this be so, how silly of us to bother our heads in trying to find out who first domesticated the cat, when in all probability it was the cat who first domesticated man. But, avaunt! all learned discourse on the subject; perish all discursive lore. I have studied the matter over and over again, and read about it in languages dead and living, till my head ached, and my heart was sick; and still, for the life of me, I cannot make out that there are any more than two distinct species of domestic cats in existence. There are, first, the European or Western cat, a short-haired animal; and secondly, the Asiatic or Eastern cat—called also Persian or Angora, according to the difference in the texture of the coat, it being exceedingly fine, soft, and satiny in the Angora, and not so much so in the Persian—a long-haired cat. All the others, such as Assyrian, Abyssinian, the Maltese, Russian, Chinese, Italian, French, Turkish, etc, are either inter-breeds between the two, or lineal descendants of the one or the other, altered and modified by climate and mode of life.

Taking everything into consideration, I am inclined to favour the belief held by some, that our own fireside cat was first domesticated from our mountain wild cat. I mentioned, this to a naturalist of some repute, with whom I was dining only a few days ago.

“What?” he roared, trying to get across the table, in order to jump down my throat. “You ought to know, sir, that all animals increase, instead of degenerating in size, by being transplanted to domestic life.”

I didn’t contradict the man in his own house; but indeed, reader, the rule, if rule it be, admits of numerous exceptions. It holds good among horses, and I suppose cattle of all kinds; it even holds good if we go down the scale of organic life, and apply it to fruit and flowers; but how about the wilder animals, and our forest trees? Take the latter first—will the acorns of a garden-grown oak-tree, or the cone of a transplanted Scotch pine, produce such noble specimens as those that toss their giant arms in the forest or on mountain-side? Or will a menagerie-bred lion, or tiger—feed them ever so well—ever reach the noble proportions of those animals who in freedom tread the African desert, or roam uncaged and untrammelled through the jungles of Eastern India? What prison-born elephant ever reached in height to the shoulders even, of the gigantic bulls that my poor friend, Gordon Cumming, used to slay? Do eagles, owls, the wilder hawks, alligators, or anacondas do anything else but degenerate in captivity? But even admitting, hypothetically, that the rule would hold good as regards cats, there isn’t such a very great difference in the size of the tame and wild cats after all. I do not think that all the wild cats ever I saw in Scotland or elsewhere, would average over ten to twelve pounds; and twelve pounds is no unusual weight for our domestic cheety. Another thing that has often struck me is this: the farther north you go in Scotland, and the nearer to the abode of the wild cat, the greater is the resemblance in head and tail, and often in colour, of the tame cat to the wild. And, mark you, the domestic is often known to inter-breed with the wild cat, and the offspring can be tamed and reared. This is considered nothing unusual in the Highlands.

CHAPTER THREE. BREEDS AND CLASSES. THE TORTOISESHELL.

The classification I propose of the domestic cat is an exceedingly simple one, as I think all classifications ought to be; it will, I trust, however, be found quite sufficient, and a useful one. We have first, then, the two and only two distinct breeds mentioned above, viz:— One. The European Cat. Two. The Asiatic.

From these two alone, if you get them of different colours, you can very easily manufacture all the varieties and various-coloured pussies you are ever likely to meet with, either on the show-benches or in domestic life.

One. The European, short-haired, or Western Cats.

These I divide into five primary classes, namely—

1, Tortoiseshell;

2, Black;

3, White;

4, Blue or Slate-colour; and

5, the Tabbies.

The Tortoiseshell I subdivide into secondary classes:

1, the pure Tortoiseshell; and 2, the Tortoiseshell-and-white.

The Black is subdivided likewise into two:

1, pure Black; and 2, Black-and-white.

The White has no subdivision, but is bred in with any or all the other classes.

The Blue or Slate-coloured Cat. These are subdivided into two:

1, the pure Blue; and 2, the Blue-and-white.

Tabbies are easily subdivided into four classes, viz:—

1, the Red Tabby;

2, the Brown Tabby;

3, the Blue or Silver Tabby; and

4, the Spotted Tabby.

There are other odd cats, such as the Manx or tailless cat, the hybrid, the six-clawed cat, and some curiously-coloured animals, which I shall mention in another place, for these have no right to have classes of their own, any more than black-and-tan Newfoundlands, or kittens with eight legs.

I shall take these in their order of rotation.

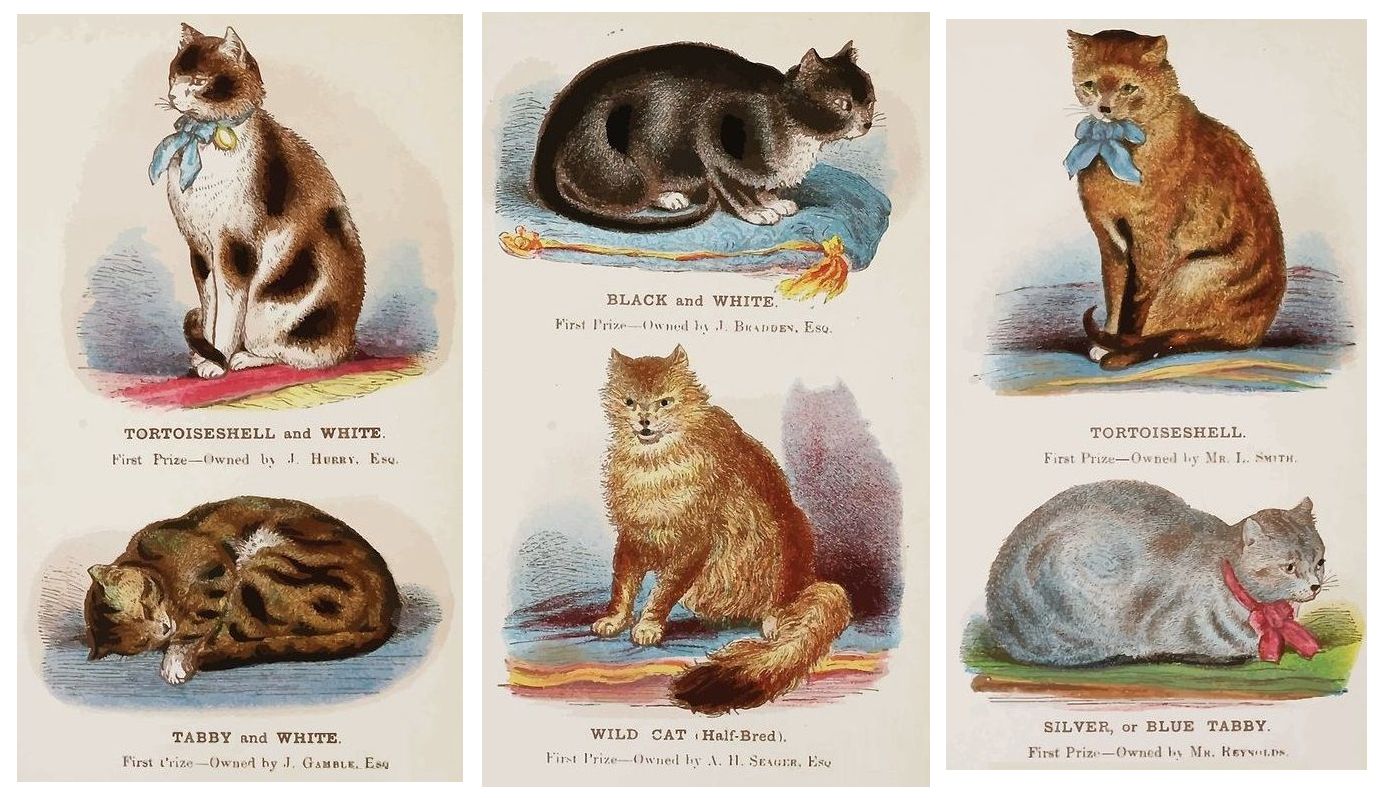

1. The Tortoiseshell Cat.

This might also be called the black-and-tan cat. If you want to get a good idea of the colour this cat is, or ought to be, take a keek through a lady’s tortoiseshell back-hair comb. That is about it; but you never see such perfection in pussy’s coat.

For many a long year it was almost universally believed that there never was any such thing as a tortoiseshell male or Tom cat, or ever could be; and many an anxious search has many an old maid had over her newly-born litter of kits, to see if she would be fortunate enough to find the much-to-be-desired anomaly. For, bear in mind, a belief used to be pretty current that 300 pounds—or was it 500 pounds?—would be paid over some counter, by some fool or fools unknown, to anyone who should be able to put the possibility of the existence of a tortoiseshell Tom beyond dispute—by producing one. I saw an advertisement the other day in The Live Stock Journal, offering for sale a tortoiseshell Tom, at the low price of 100 pounds! I hope, if only for poor Tom’s sake, that somebody with more money than brains bought it—for the cat anyone paid 100 pounds for would, I should think, be certain of good milk and generous treatment.

I knew a poor old woman in Skye, and this old woman’s pussy was as pussies love to be. And lo! one night the old woman, in the silence of night, dreamed a dream. She thought that the cat came to her bedside, and said to her, “Arise, mistress, come and see.” That she followed pussy at once. That pussy led her to the barn. That there she found, cuddled together in a heap upon an old sack, no less than five tortoiseshell Toms. She dreamt besides that she sold the lot for 1,000 pounds each, and bought a carriage and four, right off the reel, and set up for a lady of fashion on the spot. Anxiously did the old woman watch for her cattie’s accouchement, but much to her disappointment they all had white about them. Next time that pussy was in the same way, her mistress had an old tortoiseshell comb nailed up above its bed. Even this didn’t do, so—for by this time the ancient dame had tortoiseshell Tom on the brain—she set out for Portree, a distance of fully sixteen miles, where she managed to procure a live tortoise as a playmate for her pet. Pussy never took much to the tortoise; all she did was to sit and watch it, and whenever it protruded its scaly head, the cat smacked it in again. This might have been the reason why her kittens had all white about them the third time. The old woman didn’t despair, however; she took to praying, and prayed in English, and prayed in Gaelic, and she told me seriously that she never doubted but that her prayers would one day be answered—if, she added, it was for her good. I didn’t doubt it either, but Tom never came ashore as long as I was in the island, neither was the old creature’s snuff-box ever empty.

I have but little fancy for this breed myself. They are usually sour-tempered, unfriendly little things to all save those who own and love them. They are, moreover, not very prepossessing. I speak of the cat as I have found it, and I doubt not there are many exceptions.

Merits.

They are excellent and patient mousers, and the best of hunters. They are likewise good mothers. They are as game as a bull and terrier—in fact they seem to fear nothing on four legs; and when they do take off the gloves to fight, I pity the animal they tackle, for what the tortoiseshell lacks in weight, she makes up for amply in courage. They are very wise and sagacious, and faithful to the death to those who own them.

Points.—1. Size: You don’t look for a very large cat of the pure tortoiseshell breed, nor a very pretty one. The larger the better to a certain extent. I have known a small-sized tortoiseshell cat follow the rats even into their own burrows, again and again, until she had exterminated them. 2. Head: The head is small and rather bullety, the ears moderately large and nicely cocked, and the eyes small, and the darker the better. 3. Colour and markings: The colour is as near tortoiseshell as possible, and the markings must not only be deep and pretty, but very distinct in the centre, although blending insensibly where they meet, and artistically arranged. You mustn’t expect to find the colour or markings very nicely arranged on the male tortoiseshell. No white is allowed on this breed of cat. Tortoiseshell Tom is tortoiseshell Tom, and prefers to be judged alone and on his own merits; for, as a rule, his right there is none to dispute. 4. Pelage or Coat: Hair moderately short, but very fine, glossy, and silken. N.B.—Knock off from five to eight points for cinder-holes. I now give the points in a tabular form, with their full value. Not, remember, that as a rule I go in for judging by points; still, a table of this sort has its value, as one can see just at a glance what is looked for in each breed, and what isn’t:—

Points of the Tortoiseshell Cat.

1. Size, 5.

2. Head, 10.

3. Colour and markings, 25.

4. Pelage, 10.

Total, 50.

The next pussy which demands a few passing remarks is The Tortoiseshell-and-white. This is often a very beautiful cat, more especially when young, as, when old, they sometimes degenerate into very lazy habits, especially if they have a large amount of white about them. They are pretty, and they seem to know it, taking great delight in keeping the white portions of their fur as pure as snow. I knew a cat something of this breed, who was nearly all white, excepting a beautiful tortoiseshell patch on the upper part of one thigh. She was unexceptionably cleanly, and the frantic efforts she used to make to wash off that spot of black-and-amber were ridiculous to behold. She would sit for hours admiring herself in the glass, and occasionally dipping her paw in her saucer of milk, until she spied that unhappy spot; to that she would at once devote a good half-hour, but finding no appreciable difference in it, she would start away in high dudgeon, swishing her tail about, like a lion in love. That spot was the only barrier to pussy’s bliss. Moral: There’s no such thing as perfect happiness here below—even to a cat.

Next on the list of classification comes the Black Cat, subdivided into—1, the Pure Black; and 2, the Black-and-white.

1. The Pure Black

This is one of my pet breeds. The pure black cat is such a noble, gentlemanly fellow, and if well-bred and trained—and he is capable of a very large amount of training—he is one of the best and most useful cats you can have in the house. There is no namby-pambiness about black Tom, and no squeamishness either. You can take him or tire of him, just as you please; it is all one to Tom. There is a certain independence about his every movement, and an assumption of dignity, as he saunters about the house, gazes at the fire of a winter’s evening, or rolls himself in the sunniest spot of the garden in summer, that are both amusing and delightful. Black Tom will give you a paw, but you may take it or leave it, just as suits you; and if you annoy him too much, he will very quickly cast his gloves and make you laugh with the wrong side of your mouth, as the saying is. And it is quite astonishing, too, what a beautiful deep and cleanly-cut wound—I speak feelingly, as a surgeon—Tom can make on the fleshy portion of your hand, or down the side of your nose. For black Tom, and all the race of black cats, seem to have made up their minds ages ago not to stand any nonsense from man or beast.

But you mustn’t run away with the idea that black Tom is a pugnacious animal, or fond of fighting for fighting’s sake. No, Tom is never aggressive; he stands a good deal before he is thoroughly roused, and, to tell the truth, I have more than once seen a tortoiseshell thrash a black cat double its size. But if there is a lady cat in the play, the affections of a queen to be gained, or if black Tom has made up his mind to carry war into the heart of a rival’s camp, doesn’t he go at it with a will! If the other cat will not surrender, ten to one all you’ll find of that cat in the morning will be the front teeth, the wind of the battle having blown all the fluff away, while, if you cast your eyes upwards, you will see black Tom on the top of the wall making love to his Dinah, and looking as if butter wouldn’t melt in his mouth.

Black Tom is generally most exemplary in the matter of cleanliness, personal or otherwise—there you have him again. And he is as proud as Lucifer—for he is quite well aware that he is good-looking. If he were a man, he is just the sort of fellow who would wear a well-fitting coat, spotless linen, and well-fitting boots and gloves, and part his hair in the centre without appearing a cad. You will seldom see cinder-holes in black Tom; if you do, you may lay your honour on it, that the animal is either aged and infirm, or suffering from some internal disorder.

The black cat might be called the Newfoundland of the feline race, not only in colour, but in nearly all his ways. He is not the pussy, however, I like to see made a pet of by children, for two reasons—first, he is too fine an animal to be crumpled and spoiled; and, secondly, because, like a good many Newfoundlands, he is liable at times to be just a little uncertain in temper.

Although he cannot save life, like his prototype, still black Tom makes the best of black guards, and will protect his master or mistress, or their property. One or two that I happen to think of now, keep a watch on their master’s wares just as a dog would. One belonging to Mr Taylor, of Cumministon, “clooked” a little boy in the very act of stealing a piece of butter, and held him, growling fiercely the while, until his master came. The same cat would keep the packet of groceries ordered by a customer, until the money was paid, and he was told it was all right. The cunning and wiliness of the black cat is sometimes highly amusing. I have known a cat of this breed feign death to escape a thrashing; that is, when being thrashed, he pretended that one of the blows had suddenly killed him, and would lie to all appearance stark and stiff on the floor for several minutes; but if you watched him narrowly you would presently see just a line of his cute brown eye, and as soon as the coast was clear, Tom would come to life again, and be off like a shot.

Black cats are sometimes thieves. I know the reader would put it in more forcible language, but don’t you expect for a single moment that I will say more against my pets than the exigencies of truth compel me to, so there! I say they are at times just a leetle addicted to appropriating what they have but small legal right to. But there is this to be said in their favour—when they are thieves they are swells at it. I have a black cat in my eye at this very moment, and if, my dear lady, you are at all fond of that sort of thing, it would, simply do your heart good to watch that pussy stalking steak. He is such an honest-looking cat, you see, and from the easy way he sits in the doorway opposite the butcher’s, with his half-shut eyes and his dreamy air, you would feel convinced that the house was his home, that all the adjoining property belonged to him, and he had a vote in Parliament and a seat on the municipal bench. But bide a wee till Blocks turns round to serve a customer, when pop! fuss!! honest Tom is round the corner with a pound of beef in his mouth, before you could say “Muslin!” Oh! it’s charming, I assure you, but rather rough on Blocks.

I must confess, too, that, at times, there is about a black Tom cat a look which you can only designate as Satanical—Mephistophelean, then, if you object to the other word—and I have no doubt it is this look of devil-beauty in Tom which has often led him to be suspected of being either an imp of darkness or possessed of one. A witch, you know, is generally supposed to have as a companion a familiar spirit in the shape of a black cat. Superstitions connected with the black cat are still common in some parts of the country and among sailors. We had a black Tom in the Penguin which led us many a pretty dance. He was treated as a fiend, poor fellow, and behaved as such; and the captain was as much afraid of him as anybody else, and never failed to let go the life-buoy and lower a boat when Tom missed his footing and fell overboard, which the cat had a happy knack of doing periodically. Tom was missed, though, one morning, and seen again no more. He had doubtless fallen into the sea in the darkness of the middle watch.

This cat had a strange method of fishing, which is worthy of notice. You are, I suppose, aware that flying fish are caught by exposing a light on deck, which they always vault towards. Black Tom’s eyes had the same effect. He would sit on the bulwarks and glare into the sea till a fish flew towards or over him, then he nabbed it nimbly. Just before we came to the Cape, for the last time in that commission, I heard two blue-jackets conversing about this black Tom.

“Look, see!” one was saying, “I think he were a devil, nothin’ more and nothin’ less; and I’ll bet you five bob he were a devil.”

“Done,” said the other sailor.

Three days after, both men were “planked” for coming off drunk. They had been on shore drinking their bet beforehand. Simple souls, they both came to me after punishment, to get my decision as to who should pay. Their doctor, they thought, knew everything. But very sadly were they put out, when I told them the bet could never be satisfactorily decided in this world.

“Ah! doctor,” said one, waggishly, “it’s a jolly good thing we drank the bet beforehand.”

Black Tom’s queen is usually a very lively lady, and up to any amount of fun and mischief.

Merits.—For house-hunting they are the best cats you can have. They are very beautiful and graceful; and, indeed, a well-bred, well-trained black Tom is a veritable prince of the feline race. The finest cat of this sort I ever saw was at Glasgow Show, “Le Diable” to name. He was a beauty. What attitudes he did! What grace in every movement! and such a colour and coat and eye! I forget now who owned him, but I remember I gave him first prize after only one glance at the others. Black cats are not so easily seen at night, and their hearing is extremely keen; so, likewise, is their eyesight. As a rule, they kill rats and mice more for sport than anything else, and are fonder of tackling larger game. In the field, however, their colour is against them, and makes them a good mark for the keeper’s gun. I prefer seeing black Tom in the parlour, or on a hosier’s counter, or coiled up in a draper’s window.

Points.—1. Size: You want them large—as large an possible, and with great grace of motion. 2. Head: The head is medium-sized, and not too bullety; a sharp nose, however, is an abomination in a black cat. The ears must be rather longish, and shapely, and well-feathered internally, and set straight on. 3. Eyes: A brown eye is best, next best is hazel, which in turn is better than green, but green is better than yellow. 4. Colour: All black; not even a toe must be white, nor one hair of the whiskers. 5. Pelage: A beautiful, soft, though not too fine, fur, and inclining rather to length than otherwise, and as sheeny as a boatman beetle.

Points of the black cat.

Size, 15.

Head, 5.

Eyes, 5.

Colour, 15.

Pelage, 10.

Total, 50.

CHAPTER FIVE. THE BLACK-AND-WHITE CAT AND THE PURE WHITE.

I have been asked to give a few hints as to the best and most useful classification for show purposes, and may as well do so here. For a large show, the classes can hardly be better arranged than they are in the Crystal Palace catalogue, or that of the Edinburgh or Glasgow Shows. For smaller shows I beg to suggest the following:—

One. Long-haired cats, any colour, male or female.

Two. Short-haired black and black-and-white, and white.

Three. Short-haired tabbies, any colour.

Four. Short-haired tortoiseshell and tortoise-and-white.

Five. Anomalous, as Manx, etc.

The first class would include Persian, Angora, and other long-haired cats—black, white, tabby, or tortoiseshell. The third class would include all tabbies—brown, red, and grey or silver. Class Four must have tortoiseshell-and-white as well as tortoiseshell, or it will be a small class, owing to the rarity of the pure tortoiseshell. The last class will give a place to Manx, six-toed cats, wild cats, and hybrids, as well as any curious foreign pussy that may be forthcoming. At all shows you find a great many cats entered in the wrong class. I think it a pity that secretaries don’t arrange these in their proper classes; it is not right to exclude merit through mistake. In judging, prizes should be withheld where there is no competition; and where there is want of merit in any one class, some of the prizes should be withdrawn and added to any class of extra merit. We come now to the black-and-white cat.

A good black-and-white cat is a very noble-looking animal. If well-trained and looked after, you can hardly have a nicer parlour pet. He is affectionate in his disposition, and cleanly and gentlemanly, so to speak, and makes himself quite an ornament to a well-furnished drawing-room. I must speak, however, of the demerits of my pets, as well as of their good qualities, and feel constrained to say that I have sometimes found black-and-white Tom a pussy who did not trouble himself too much about his duties as house-cat; he much preferred the parlour to the kitchen, a good bed to a hay-loft, and seemed to think that catching mean little mice was far below his dignity. If well treated black and white cats are apt to turn a little indolent and lazy, and if improperly fed and housed, they degenerate into the most wretched-looking specimens of felinity you ever looked upon. All the bad in their character comes out, and their good qualities are forgotten. Their coat gets dry, and tear, and are cinder-holed; and, instead of the plump, round-faced, clerical-looking cat which used to adorn your parlour window, you have a thin, emaciated, long-nosed, pigeon-loft-hunting, flower-unscraping, dirty, disreputable dunghill cat. Of course, the same may, to a certain extent, be said of most neglected cats, but the two breeds that show to the least advantage, when ill-used, are the black-and-white and the red-and-white, and more especially the former.

Merits.—I like these cats more for their appearance than anything else. When nicely marked they look reverend and respectable in the extreme. I consider them but very ordinary pussies in regard to house-hunting. A naval officer who cannot go to quarters without having his hands encased in white kids, and a black-and-white cat, carry on duty much on a par. Neither do these cats make over good children’s pets, being at times a little selfish. They are beautiful creatures, nevertheless, and well worthy of a place at our parlour firesides.

Points.—

1. Size: As big as possible, but not leggy; reasonably plump for the show-bench, but very graceful in all their motions; with stoutish short forelegs, and plenty of spring in the hindquarters.

2. Head: The best black-and-white Toms have large, well-rounded heads, with moderately long ears, and a well-pleased, self-contented expression of face. The whiskers are usually white, but black is not objectionable. The eyes are preferred green, and sparkling like emeralds of the finest water.

3. Colour and markings: The colour is black-and-white, with as much of the former, and as little of the latter as you can find. I like to see the nose and cheeks vandyked with white, the chin black, white fore-paws, white hind legs and belly, and a white chest. This is all that is needed for beauty’s sake; but, at all events, the markings must be even.

4. Pelage: Fur should be longish (and I don’t object to its being ticked all over the back with longer white hairs), silky, and glossy.

Points of the Black-and-White Cat.

Size, 10.

Head, 5.

Colour and markings, 25.

Pelage, 10.

Total, 50.

The next cat on the boards is the white cat.

It is very remarkable—and most students of feline nature must have had an opportunity of observing this—the great difference in the temperament, constitution, and nature of cats, which colour alone, apparently, has the power of truly indicating; and this is nowhere more easily seen than in the peculiar characteristics of the pure black pussy and the all-white one. The black cat, on the one hand, is bold, and free, and fierce; the white, far from brave, more fond of petting and society, and as gentle as a little white mouse. The black cat is full of life and daring; the white of a much quieter and more loving disposition. The black cat stands but little “cuddling;” the white would like to be always nursed. It takes but little pains to teach a black cat to be perfectly cleanly, but much more to train a pure white one. In constitution the black cat is much more hardy and lasting, the white cat being often delicate, and longing apparently for a sunnier clime. A black cat is often afflicted with kleptomania, while a properly-educated white puss is as honest as the day is long.

The senses of the black cat are nearly always in a state of perfection, while the white is often deaf, and at times a little blind. Again there is nothing demoniacal about a white cat, as there often is about a black one. I remember, when a little boy at the grammar school of Aberdeen, receiving a box from the country containing lots of good things, and marked, “A Present from Muffle”—Muffle was a pet tabby of mine—and, childlike, replying in verse, the last lines of the “poem” being—

“And when at last Death’s withering arms

Shall throw his mantle thee around,

May angel catties carry thee

To the happy hunting-ground.”

Well, a blue-eyed white pussy was my idea of an “angel cattie” then, and it is not altered still.

It will be observed, however, that the colour of the kittens of the same litter will often differ, and the question naturally comes to be asked, Do I assert that the nature and temperament of cats in the same litter will not coincide? I do so aver most unhesitatingly; and the thing is easily explained if you bear in mind that a litter of differently-coloured kittens has had but one mother, but many fathers. Although born from the same mother in one day, they stand in the relation to each other of half-brothers and half-sisters. Except when the odds in colour is very distinct, as in black, white, or red, the difference in constitution, etc, will not be so easily perceived, but it is there, nevertheless. Colour follows the breed, and temper and quality follow colour. This is the same all throughout nature, and is often observed, though but little studied, by dog fanciers. I have only to remind pointer and setter men, how often hardiness and good stamp cling to certain colours. That “God tempers the wind to the shorn lamb,” I believe to be merely metaphor, but I am ready to go to death on it that He paints the petals of the flower and the blossoms on the fruit-tree, to the requirements of the tender seedlings. What sort of fruit would you grow in the dark, or under deeply-coloured glass shades? Lest I be found guilty of digression, I shall say no more now on this subject.

Merits of the White Cat.—A pet, gentle and loving above a cat of any other colour, though at times dull, and cross, and wayward; “given,” as a lady said, “to moods of melancholy.” Not a bad mouser either, when “i’ th’ vein,” and a good cat for a miller to have, not being easily seen among sacks of flour.

Points.—1. Size: Seldom a large cat. 2. Head: Smallish, and as nicely rounded as possible; ears not too long, and well-feathered internally; eyes of “himmel-blue;” eyes ought to be both the same colour—if not so, deduct five points. 3. Pelage: Fine, soft, and glossy; but a too long coat shows a cross with Angora. 4. Colour: White as driven snow, if intended for a show cat; if not, a very little black wonderfully improves the constitution.

Points of the White Cat.

Size, 5.

Head and eyes, 15.

Colour, 25.

Pelage, 5.

Total, 50.

CHAPTER SIX. THE BLUE CAT; AND TABBIES—RED, BROWN, SPOTTED, AND SILVER.

The Blue cat: just one word about this pretty creature before passing on to the Tabbies. Although she is called a blue cat, don’t fancy for a moment that ultramarine is anywhere near her colour, or himmel-blue, or honest navy serge itself. Her colour is a sad slate-colour; I cannot get any nearer to it than that.

Apart from her somewhat sombre appearance, this cat makes a very nice pet indeed; she is exceedingly gentle and winning, and I’m sure would do anything rather than scratch a child. But the less children have to do with her the better, for all that: for this simple reason—she is a cat of delicate constitution—all that ever I knew were so, at least, and I daresay my readers can corroborate what I say.

Merits.—

Their extreme gentleness is one merit, and their tractability and teachability are others. A pure blue cat is very rare, and they are greatly prized by their owners.

Points.—

1. Size: They are rather under-sized, never being much larger than the pure tortoiseshell.

2. Head: The head is small and round, and the eyes are prettiest when of a beautiful orange-yellow. The nose should be tipped with black.

3. Pelage: Moderately long and delightfully soft and sheeny.

4. Colour: This is the principal point. It is, as I said, a nice cool, slate-grey, and, like the black cat, our blue pussy must be all one colour, without a hair of white anywhere. Even her whiskers must be of the same colour as her fur.

Points of the Blue Cat.

Size, 5.

Head, 5.

Pelage, 10.

Colour, 30.

Total, 50.

We now come to the Tabbies—the real old English cats—the playmates of our infant days and sharers of our oatmeal porridge. They are the commonest of all cats, and justly so, too, for there is hardly anything they don’t know, and nothing they can’t be taught, bar conic sections, perhaps, the Pons Asinorum, and a few trifles of that ilk. You will find a tabby cat wherever you go, and you will find her equally at home wherever she is—whether sitting on the footstool on the cosy hearthrug, singing duets with the tea-kettle; catching birds and rabbits in the woods, or mice in the barn; conducting a concert for your especial benefit on the neighbouring tiles at twelve o’clock at night; examining the flower seeds you lately sowed in the garden to see if they are budding yet; or locked, quite by accident, into the pigeon loft.

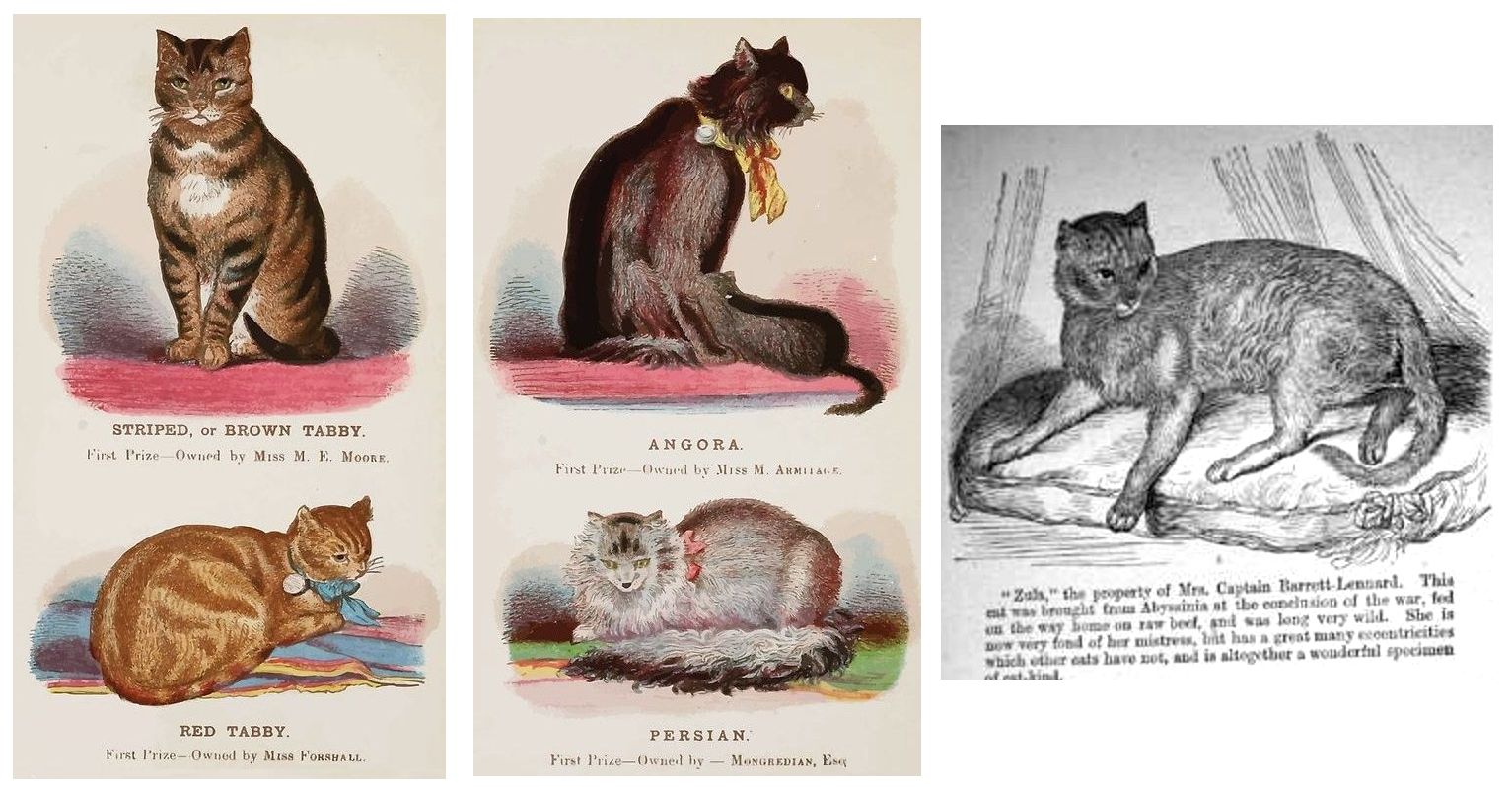

The first cat of the Tabby kind which claims our attention is the Red or Sandy Tabby.

This is a very beautiful animal, and quite worthy of a place in the best drawing-rooms in the land. Although they do not grow to the immense size of some of our brown tabbies, still they are better hunters, much fiercer, and of a hardier constitution. They much prefer out-of-door sport, and will attack and slay even the polecat and weasel; and instances have been known of their giving battle to the wild cat himself.

Merits.

They are the prettiest of pets, and the honestest of all cat kind. They are such good ratters that neither mice nor rats will frequent the house they inhabit.

Points.—

1. Size: They ought to be as large as possible, and not clumsy; they are generally neater cats all over than the Brown Tabbies.

2. Head: The head should be large and broad, with rather shortish ears, well placed, and the face ought to beam with intelligence and good nature. The eyes should be deep set, and a nice yellow colour.

3. Pelage: The coat is generally short in nearly all the Tabbies, but ought to be sleek and glossy. 4. Colour and markings: The colour is a light sandy red, barred and striped with red of a darker, deeper hue. No white. The stripes or markings ought to be the same on both sides, and even the legs ought to be marked with cross bars, and one beautiful swirl, at least, across the chest. This is called the Lord Mayor’s Chain, and when the cat has two, give him extra points.

Points of the Red Tabby.

Size, 10.

Head, 5.

Colour and markings, 30.

Pelage, 5.

Total, 50.

Next comes the Brown Tabby.

This is the largest of all breeds of cats, fourteen, seventeen, and even twenty pounds a common weight. They are also, when well marked and striped, exceedingly beautiful. Of all cats they are the best adapted for house-hunting, being less addicted to wandering than some breeds.

Merits.—Their hunting proclivities. Their fondness for children is sometimes quite remarkable. I have known many instances of Brown Tom Tabbies, so fierce that scarce any one dare lay a finger on them unscathed, but a little child of four years of age could do anything with them, lug them about anyhow, and even carry them head down, over its shoulder by the tail. They are, moreover, nice, loving, kind-hearted pets, and exceedingly fond of their master and mistress. They are the cats of all cats to make a family circle look cosy and complete around the fire of a winter’s night.

Points.—

1. Size: It will be observed below that I give fifteen points for size. The bigger your Brown Tom Tabby is the better he looks, if the one-half of it isn’t fat, for if so he won’t be graceful, and that is one essential point. I can find a Tabby at this moment who weighs over twenty pounds, and who will spring from the floor, without scrambling, mind you, clean on to the top of the parlour door, and that is little short of seven feet. I like to see a tabby with a graceful carriage then, and shortish in forelegs, with beautifully well-fitted and rounded limbs, and with a tiger-like walk and mien.

2. Head: Very large and broad and round, ears short, eyes dark, and muzzle broad, not lean, and thin and long. This latter certainly gives him more killing power, but it brings him too near the wild cat. I don’t care how savagely he behaves in a cage at a show, for well I know he is quite a different animal at his own fireside, asleep on the rug in little Alice’s arms, or purring in bed on old Maid Mudge’s virgin bosom.

3. Colour: A nice dark brown or grey ground, and the workings as deeply black as possible. No white.

4. Markings: Like a Bengal tiger, and even prettier. The tail and legs likewise barred. The head striped perpendicularly down the brow, and the marks going swirling round the cheeks. Nose black or brown, and the eyes as dark as possible, and full of fire.

5. Pelage: Short and glossy.

Points of the Brown Tabby.

Size, 15.

Head, 5.

Colour, 10.

Markings, 15.

Pelage, 5.

Total, 50.

Lastly, we have the Silver Tabby and the Spotted Tabby, and in almost all points these may be judged alike.

The Silver Tabby is a sweetly pretty cat. Perhaps the prettiest of all pussies. They are a size smaller than even the best Red Tabbies, and are infinitely more graceful, and quicker in all their motions. They are proud, elegant, aristocratic cats, fond to love and quick to resent an injury.

Merits.—Their special merit is their exceeding beauty. They are somewhat rare, however. Here is a bit of advice to any one who would like to have four really pretty cats about the house, each to show the others to advantage. Get a pure white kitten, a pure black one, a red tabby, and a silver ditto. Take great care in the training of them, be careful in feeding and housing them, and you will have your reward.

The Spotted Tabby is also very pretty. He ought to be a good, sizeable animal, with broad head, short ears, and a loving face; ground colour a dark grey, one dark stripe, and down the spine, and diverging from this stripes of black broken up into spots.

Points.—The Silver Tabby ought to be—

1. In size, less than or about the size of the Red Tabby, and very quick and graceful.

2. Head: Large and shapely, but not so blunt as the Brown Tabby’s; ears short and eyes light.

3. Colour and markings: Of a deep Aberdeen granite, grey in the ground-work, and the markings very dark and beautifully arranged. Don’t forget the Mayor’s Chains.

4. Pelage: Longish, if anything; but not so long as to make the judge suspect crossing with the Persian.

Points of Silver and Spotted Tabbies.

Size, 10.

Head, 5.

Colour and markings, 30.

Pelage, 5.

Total, 50.

There are one or two fancy cats I have not mentioned, as the Red-and-white, etc; but I believe I have said enough to make anyone, with a little study and attention, a good judge of the points and qualities of the different breeds of the English domestic cat.

When I was a little boy at school, floundering through Herodotus, and getting double doses of fum-fum daily for my Anabasis — for my old teacher, when he couldn’t get enough Greek into one end of me, took jolly good care to put it in at the other—there was no man I had greater respect for than Alexander the Great, owing to his having done that Gordian knot business so neatly. I practised afterwards on the dominie’s tawse (i.e., the fum-fum strap); I tied a splendid knot on it, and then cut it through with a jack-knife; but, woe’s me! the plaguy dominie caught me in the very act, and—and I had to take my meals standing for a week.

But ever since then I have always been a don at knots; and I give myself no small credit, whether you do or not, reader, for the dexterous manner in which I have polished off the cat-classification knot. There it lay before me, interminable, intricate, incensing; and bother the end could I see to it at all at all. “Draw the sword of Scotland.” Swish! There it lies, the short-haired European pussies on the one hand, and the Asiatic or long-haired on the other.

Among these latter you will find exactly the same colours, and the same variety of markings, as among the European cats proper. We give their points in a general way.

1. Size: The blue cats and the pure white are usually of the smallest dimensions; next comes the black, and lastly the tabbies. Some of these latter grow to immense sizes, and are animals of a beauty which is at times magnificent. The cat that belonged to Troppman, the distinguished French murderer, and now, or lately, possessed by Mr Hincks, of Birmingham, is worth going a day’s journey to behold. Yet, although very large, they are very graceful, too, and can spring enormous distances. Fierce enough, too, they can be when there is any occasion, especially to strangers or dogs.

2. Head: The heads of the white, blue, and black ought to be small, round, and sweet, the expression of the countenance being singularly kind and loving. The heads of the tabbies ought to be broad and large, and not snouty. The whiskers of both ought to be very long, and of a colour to match the general tone. The ears have this peculiarity—they are slightly bent downwards and forwards, which gives rather a pensive character to their beauty. They are, moreover, graced by the aural tuft. The eyes must also match; and this is what I like to see—a blue eye in a white Persian, a hazel in a black, and a lovely sea-green in a tabby.

3. The Pelage: The pelage is long (the longer the better), especially around the neck and a-down the sides; and a good brush, gracefully swirled and carried, is an essential point of beauty. The fur ought to be as silken as possible; this shows that the cat is not only well-bred, but well-fed and taken care of.

4. Markings: They ought to be as distinct as possible, as pretty as possible, and evenly laid on with reference to the two sides.

5. Colour: All white in the pure white, all black in the black, and so on with the other distinct colours; and for the tabbies the same rules hold good as those given for short-haired tabbies.

General rules for judging Asiatic Cats.—

First scan your cats, remembering the difference in size you are to expect in tabbies from the others. Next see to the length and texture of the pelage—its glossiness, and its freedom from cinder-holes, or the reverse. Then note the colour, and the evenness or unevenness of the markings. The head most be carefully noted, as to its size and shape, the colour of the eyes and nose, ditto the whiskers; mark, too, the lay of the ear, and its aural tuft. In the tabbies the Mayor’s Chain should swirl around the chest. Lastly, take a glance at the expression of face.

Merits of the Asiatic Cats.—

I think every cat-fancier will bear me out in saying that, although more delicate in constitution than our European short-hairs, and hardly so keen at mousing, ratting, or so fierce in fighting larger game, there can be no doubt of it they make far nicer pets. They are extremely affectionate and loving in their dispositions, and so fond of other animals, such as dogs, pet rabbits, guinea-pigs, etc. Their love for a kind master or mistress only ends with life itself. Then they are so beautiful and so cleanly, and, if kept in a clean room, take such care of their lovely pelage, that I only wonder there are not more of them bred than there are. They are a little more expensive at first. You can seldom pick up a good kitten at a show under one pound sterling—but if you do succeed in getting one or two nice ones, I am quite certain you will never have to repent it, if you only do them ordinary justice.

It will be well to end this chapter here; but before doing so, I beg to make one or two remarks, which I feel sure will interest secretaries of coming cat-shows.

1. In all shows give the cats nice roomy pens, whether of wood or zinc.

2. Attend well to the ventilation, and more especially to disinfection.

3. Attend to the feeding, and, at a more than one-day show, cats ought to have water as well as milk. I think boiled lights, cut into small pieces, with a very small portion of bullock’s liver and bread soaked, is the best food; but I have tried Spratt’s Patent Cat Food with a great number of cats, both of my own and those of friends, and have nearly always found it agree; and at a cat-show it would, I believe, be both handy and cleanly.

4. On no account let the pussies lie on the bare wood or zinc, but provide each with a cushion of some sort, and have a small box filled with earth or sand, in each pen. Sawdust in a cat’s cage is an abomination. It soils the fur, and gets into the food-dish, and renders pussy simply miserable.

CHAPTER EIGHT. ON DIET, DRINK, AND HOUSING.

“Throw physic to the dogs,” said the immortal William. That was a good many years ago, and dogs then were of very little value, and little used either to physic or good treatment; but nowadays we have found out that the possession of even a cat, entails upon us the duty and responsibility of seeing she is well cared for while in health, and properly treated in sickness. I recommended small doses of quinine and steel to an unwell pussy the other day.

“Ma conscience!” cried her owner; “gie medicine to a cat! Wha ever heard o’ the like?”

I’m sorry that woman was Scotch, but glad to say I reasoned even her round, and her cat is now as sleek and lively as the day is long.

Most, if not all the diseases which feline flesh is heir to, are brought on by bad feeding, starvation, or exposure to the weather, especially the cruel custom many people have of leaving their poor cats out all night, to seek for food and shelter for themselves. These are the cats who make night hideous with their howling, who tear up beautiful flowerbeds, rob pigeon-lofts, murder valuable rabbits, and, in a general way, do all they can to bring into disrepute the whole feline race. I declare to you honestly, there is as much difference between one of these night-prowlers and a well-cared-for cat, as there is between one of the lean and mangy curs who do scavengers’ duty in Cairo, and a champion Scottish Collie.

Some men will tell you that it is unmanly to love or care for a cat; just as if it could be unmanly to love anything that God made and gifted with sagacity, wisdom, and undying love for all the human race! But I can point you out scores of men who are good sportsmen, fearless huntsmen, and fond of every manly sport—ay, and men, too, who are at home on the stormiest ocean, and never pale when fired upon in anger—who can both pride and prize a favourite cat. At Exeter, not long since, out of thirty-nine owners of cats, all were men except nine, and of these nine seven were married, and the two others were young ladies, while the owner of the first-prize cat was a gallant soldier. So much for the notion that only old maids care for cats.

Before going on to describe the diseases which afflict pussydom, we must give a few general instructions regarding her treatment while well.

And first, as to her food. Pussy will catch a mouse, and after playing with it for half an hour in a way which is very cruel, but no doubt makes it very tender, she will generally kill and eat it; but it by no means follows that mice are the cat’s natural food. The majority of cats catch mice more for the love of sport than anything else. Nothing, therefore, is more cruel than to starve poor pussy, with the erroneous idea that it will make her a good mouser; it is just the reverse. My Phiz bids me say that mice-catching is long, weary, anxious work at the best, and she is quite certain she would die if compelled to make a living at it.

Feed your pussy well, then, if you would have her be faithful and honest, and keep your house clear of mice and rats.

I have lived a good deal in apartments in my time, and I have always avoided places where there was a lean and hungry-looking cat. It is a sure sign of irregularity and bad housekeeping.

Twice a day is often enough, but not too often, to feed your cat, and it is better to let her have her allowance put down to her at once, instead of feeding her with tid-bits. Nothing can be better for pussy’s breakfast than oatmeal porridge and sweet milk. Entre nous, reader, nothing could be better for your own breakfast. Oatmeal is the food of both mind and matter, the food of the hero and the poet; it was the food of Wallace, Bruce, and Walter Scott, and has been the food of brave men and good since their day.

“Oh! were I able to rehearse

Scotch oatmeal’s praise in proper verse,

I’d blaw it oot as loud and fierce,

As piper’s drones could blaw, man.”

But I cannot wonder for a single moment at this favourite Scottish food being in disrepute in England, because hardly anyone knows how to make it. Our cook at sea once undertook to supply our mess with a daily matutinal meal of porridge, and of oatcakes too. He was sure he could make them, because his “father had once lived in Scotland.” Nevertheless, I gave him some additional information, and we, the Scottish officers, of whom there were two or three besides myself, were in high glee, and took an extra turn on deck the first morning, to give us a good appetite for the great coming double event. Then down we bolted to our porridge. Porridge! save the name, such a slimy, thin, disgusting mess you never saw! Well might our chief engineer call out:

“Tak’ it awa’, steward, tak’ it awa’; it would scunner (sicken) the de’il himsel’!”

“But, hurrah!” I cried, “there’s the oatcakes to come. Steward, where are the oatcakes?”

The steward lifted the cover from the dish on which was wont to repose our delicious “’spatch cock,” or savoury curry, and there, lo and behold! half-a-dozen things of the shape and thickness of a ship’s biscuit, black, and wet, and steaming, and we were supposed to eat them with a knife and fork! Meanwhile the ham and eggs were fast disappearing among the Englishmen at the other end of the table, and we poor Scots had to go without our breakfast, and get laughed at into the bargain.

But here, now, I’ll tell you what I’ll do for you, as Cheap Jack says—I’ll give you a receipt by which you shall live a hundred years, and begin your second century a deal stronger than you began your first. Buy your meal from the meal-shop—no, not the chemist, my dear—taste it to make sure it has no “nip;” see, also, that it is fresh, and not ground before Culloden, and buy it neither too fine nor too round, but just a happy medium. Having thus caught your hare, so to speak, go home with it, and put a saucepan on a clear fire, with a pint of beautiful spring-water, into which throw a teaspoonful, or more, of salt, and a dessert spoonful of oatmeal. This is essential. Then sit down and read till the water boils. Now take your “spurckle” or “whurtle” in your right hand—I don’t know the English of “spurckle” or “whurtle,” but it is a round piece of wood, rather thicker than your thumb and not so long as your arm, and you never see it silver-mounted—and commence operations. You stir in the meal very gradually, to prevent its getting knotted, and you occasionally pause to let it boil a moment, and you continue this until the porridge is quite thick, and the bubbles rise into small mountains ere they escape, with a sound between a “whitch” and a “whirr,” which is in itself a pleasure to listen to. And now it is ready, and you have only to pour it into a large soup-plate, sprinkle a little dry oatmeal over the top of it, and set it aside until reasonably cold. You eat it with a spoon—not a fork—and with nice sweet milk. “A dish fit for a king,” you say; “A dish fit for the gods!” I resound. Now, having told you all this, I feel I have well deserved of my country; and I’m not above accepting—a hamper at any time.

Bread-and-milk, soaked, is the next best thing for pussy; and at dinner you must let her have a wee bit of meat. Lights, boiled and cut in pieces, are best, but horseflesh isn’t bad; but you mustn’t give her too much of either, or you will induce diarrhoea. Give her fish, occasionally, as a treat. If pussy is a show cat, a little morsel of butter, given every day, after dinner, will make her dress her jacket with surprising regularity.

Now, as to what she drinks, a well-bred cat is always particular, and at times even fastidious; but two things they must have—water and milk. They will often prefer the former to the latter. But do keep their dishes clean. Disease is often brought on from neglect of this precaution. Cats will drink tea or beer, and I have seen a Tom get as drunk as a duke on oatmeal and whisky. An old lady, an acquaintance of mine, has a fine red-and-white Tom, and whenever he is ailing she gives him “just a leetle drop o’ brandy, sir.” Tom, I think, must have had two little drops o’ brandy yesterday, when he rode my fox-terrier, Princie, all round the paddock. Those naughty drops o’ brandy!

Just one word about housing. There is no more objectionable practice than that of turning your cat out of doors at night, and none more certain to engender disease and spoil your pussy’s morals. If you have taken the least pains to train your cat to habits of cleanliness, she will never misbehave herself. Keep her in at night, then, and you’ll have her in health; keep her in if you want to run no risk of getting her poisoned; keep her in, and the neighbours will bless you. Don’t lock her into a room, though, unless she has an attic to herself. Let her have the run of the house from basement to roof. Give pussy a bed to lie on, or let her find one for herself, which she has a happy knack of doing, as I daresay more than one of my readers can testify. My pretty Phiz needn’t have kittened in my cocked hat, nevertheless.

So much, then, for the prevention of disease. We will now come to diseases themselves. But just let me impress upon your mind, reader, this fact—that attention to your pussy’s housing, drink, and the cleanliness and regularity of her diet, will almost certainly prevent her from getting sick.

CHAPTER NINE. THE DISEASES OF CATS.

Before describing the management and treatment of feline ailments, I may as well mention that there are three different plans usually adopted for giving a cat medicine. Pussy must first and foremost be caught—not always an easy job, as the little creature is fond of hiding away when ill. Take her on your knee, and, as you gently soothe her, envelope her, all save the head, in a woollen shawl, and then place her in some one else’s arms to hold. Now, if it is a pill or small bolus it must be dipped in oil, and placed well down behind the tongue, and towards the roof of the mouth; if it is a powder, it may simply be placed on the tongue; but the better plan is to mix it first with a little treacle or glycerine; thirdly, if it is a fluid, the mouth must be held well open, and the medicine poured down the throat out of a small phial, but only a few drops at a time.

If your cat is suffering from any severe illness, such as bronchitis, and you value her, set aside a garret or lumber-room for her accommodation, for quiet is essential to her recovery. Arrange her bed as common sense tells you will best suit her comfort; don’t forget to let her have plenty of clean water to drink, and a large box of garden mould in the far corner of the room. There is only one other little matter, which must not be overlooked—and, with this, pussy’s little hospital is complete—Grass.

Grass.—This is the natural medicine of both cat and dog. In large doses, it acts as an emetic; in smaller, as a purgative; its mode of action being similar in both cases, namely, mechanical irritation of the muscular and mucous coats of the alimentary canal; this causing spasmodic contraction of the stomach, or increasing the peristaltic motions of bowel. Grass also possesses valuable antiscorbutic properties, and the cat, either in sickness or health, should never want a supply of it.

If pussy has been out all night at a feline entertainment on the tiles, and the excitement has produced constipation, her remedy is grass. If she has made too free in the aviary, and the feathers of the Norwich cock lie unpleasantly on her stomach, grass is her cure; or if she, at any time, feels hot or feverish, out into the garden she goes, and a little grass, taken at intervals, soon makes her feel as fresh as the lark.

Don’t let your cat want grass, then; if you live in a town, and she has some difficulty in getting it, either procure it for her yourself, or, what is better, get a boxful of earth, and sow it, and call it pussy’s garden. Now for pussy’s ailments.

Mange.

All skin diseases in the cat, whether pustular, papular, or squamous, may be, for convenience’ sake, called mange. Cats are very subject to skin diseases, especially long-haired ones, and those who have been the subjects of bad or careless treatment; for they are always brought about by poverty of the blood, from under-feeding, or surfeit from over-eating on dainties. Now I must warn the cat-fancier that there is no specific for the cure of mange in the cat, and that the cure will take weeks, and at times even months; he must therefore make up his mind either to destroy the cat at once, or set about curing her in earnest. Attend, in the first place, to her diet. It must be nourishing, but not heating; plenty of good milk, and no meat, unless she be very thin, when raw meat in small quantities may be given twice a day. Dress the skin with carbolic oil, washing her carefully next day; then try equal parts of sulphur-ointment and green iodide of mercury ointment, mixed with an equal bulk of lard. Give her arsenic internally—one drop of the Liquor arsenicalis twice a day, in milk, for a week, then thrice a day for another week, when you must omit it for a day or two, and then begin again. At the same time give her, once or twice a week, a little sulphur. Placing brimstone-roll in a cat’s drinking-water is all a mistake, and does no good at all. Sometimes the disease will only yield to a course of iodide of potash. Give her half-grain or whole-grain doses, made into little boluses with breadcrumbs—which any chemist can make for you—twice a day.

Ulcers.

Cats are liable to a variety of these, but they can best and most conveniently be described as of two sorts—constitutional and accidental. The first are the most difficult to cure, and are usually found on the toes or feet. Confine the cat to the house for a term; any simple ointment, such as that of zinc, will do for a dressing, as it will not hurt her if she licks it. Put her on a course of arsenic, as recommended above; give her, once a week, one grain of calomel, or two or three grains of grey powder and a little sulphur; and, if the sores appear sluggish, touch them once a day with blue-stone or nitrate of silver. Feed her well and regularly.

Accidental ulcers are generally the result of scratches and wounds received in the hunting-field, or during some slight difference of opinion with the pussy over the way. They require no internal treatment. If they look angry, bathe in warm water, or milk and water, and use, occasionally, a little lotion of sulphate of zinc—ten grains to four ounces of water, to which add one drachm of tincture of lavender. If the sores are sluggish, and indisposed to heal kindly, truss the cat in the shawl, and cauterise with nitrate of silver; afterwards dress with the mildest mercurial ointment.

Inflammation of the eyes is generally the result of injury or cold caught from exposure. It may be confined to one eye, or may attack both. In either case the treatment is the same. Begin by the use of a purgative—say two or three grains of compound jalap-powder mixed in glycerine, and given in the morning; give nothing but bread-and-milk to eat, and let the cat have a little sulphur mixed with butter or lard every second day. The external treatment consists in bathing frequently with warm water or weak green tea, and the following lotion, may afterwards be used with advantage: two grains of sulphate of zinc to an ounce of water, or one grain of nitrate of silver to the same quantity of aqua pura.

Simple Maladies.