CAT BREEDS

Translated Excerpts from “Encyclopédie Féline” (1957)

Dr. E. DECHAMBRE

Assistant Director of the Menagerie of the National Museum of Natural History, Paris

There was an existing translation of this, but it was not the sort of translation a native English speaker would produce so I have done my own translation. The original translation also had several errors in cat fancy terminology which I have corrected e.g. “blue-cream” instead of “creamy blue.”

DOMESTICATION

There seems to be little point in considering whether the cat should be classed as a domestic animal. Etymologists point out that it must be a domestic animal because one of its supposed faults is that the cat is more attached to its home than to its masters. If we go back the close of the last century, we find the learned zoologist, Cornevin, wrote:-

“As for the cat, it is an open question whether it is really a domestic animal. Without contradicting myself, it is possible to theorise that the cat is a parasite rather than a servant. The cat only lives in our homes when this is to its advantage; it readily leaves home for the fields and woods once nesting birds and game are plentiful. Man has not succeeded in changing the cat’s reproductive habits, so it is understandable if opinion is divided on the matter, and that in this present work I am hesitant about coming down on one side or the other. However, the cat is unquestionably a valuable ally in the war on rodents, and Lenz assures us that a single animal may destroy as many as 3,500 of these in a year. It is for this reason alone that I have decided not to omit it from the list of domestic animals.”

Today this attitude may provoke much protest. But readers should remember that in the past fifty years the situation has changed greatly, and during that time the cat has been selectively bred as intensely and purposefully as any other domestic species.

HISTORY OF DOMESTICATION

The history of feline domestication is still less well understood than that of other domestic species. Any clear indications of domestication are relatively recent, at least, in regard to the north-west European region. Regarding other regions the indications are generally very vague.

For a long time — until Cuvier’s writings on the subject — it was considered that the familiar domestic cat was descended from the wild cat, Felis sylvestris. This is the most obvious explanation. However, this comes up against certain difficulties. Firstly, the two cats are different in size and in several anatomical features. Secondly, the wild cat which we know is extremely difficult to tame and always lives well away from human habitation. Admittedly, these objections are not necessarily decisive because anatomical and coat differences are not always as precise as some people claim.

In Europe, prehistoric remains, starting with the Danish kitchen-midden people, the peat-bogs and caverns provide numerous specimens of wild cats of very different size. Yet they all appear to be Felis sylvestris, and there is no indication of it having been domesticated in any of those locations.

In the absence of zoological proof, we must turn to historical evidence for the clearest indication that our familiar domestic cat had an exotic origin. Evidence from Great Britain is particularly conclusive. The wild cat seems to have been plentiful in earlier times in the British Isles, right up to the 13th Century, and there were various special laws authorising their destruction, so they had the same status as wolves, foxes and other such nuisance animals. Similarly, there is evidence that the skins of wild cats were commonly used in cloaks for ordinary people, along with skins lambs, rabbits and foxes.

Finally, there are travellers’ tales, that us that as late as the beginning of the eighteenth century, England was considered to be infested with wild cats.

But in that same period and in the same region the domestic cat was strictly protected by law. Thus, Brehm reminds us of the Welsh law at the beginning of the 10th Century that shows that the domestic cat remained rare in the British Isles and was highly valued. The Welsh Code contains a measure introduced by Howell Dha (Howell the Good), who died towards the middle of the 10th Century, which lays out the value of a domestic cat and the fines imposed on any person tormenting, wounding or killing a cat. The price of a young cat which had not yet caught a mouse was set, the price of one which had caught a mouse being double that amount. The purchaser of a cat had the right to insist on the ears, eyes and claws being well formed, on the animal being a good mouser, and, if a female, on it being a good mother. If a cat sold proved to have any failing, the purchaser could claim back one third of the purchase price. Any person killing or stealing a cat on the lands of the Prince was fined a milch-ewe and its lamb, or had to provide sufficient wheat to cover the dead cat completely when this was hung up by the tail so that its muzzle "just touched the ground.”

It is clear from such legislation that the cat was considered a valuable possession. It cannot, therefore, have been descended from the wild cat because that animal was very common, and there would have been no difficulty in getting wildcat kittens to tame. Similar evidence from France and Germany leads us to the same conclusion.

At the same time it is evident that in some countries cats were used, if not actually domesticated, at a much earlier period. However, there is only one region where we have reliable early evidence of this, and that is Egypt. In Assyria, Chaldaea and India, and among the Jews, there is no trace of the domestic cat although we have evidence from those countries that pre-date that of Egypt. However, some of these people knew the cat (as a species) from very early times. Among some striking bas-reliefs found at Tell Halaf by von Hoppenheim, and dating from before 3,000 B.C., we find two very interesting representations that include the cat. These bas reliefs depict orchestras of animals. A harp-playing lion seated on a throne presides, while asses, wolves, dogs, monkeys, bears, and cats stand on their hind legs and play various instruments such as cymbals and tambourines. But these scenes, whose meanings we can only guess at, are not domesticated.

CLASSIFICATION

As a whole the classification of the wild cats is still somewhat undecided, especially regarding the small wildcat species in South America and Central Asia. The main problem is the great variability of the coat. In many cases the coat is not the same in the adult as in the young animal. Classification by coat markings is therefore unsatisfactory, since it results in the separation of animals which are otherwise closely related.

The classification of the wild cats by geographical distribution is also unsatisfactory. It may well be true that species are found in the Americas which are unknown in the Old World, but this does not necessarily mean that the American species form a distinct group. For instance, the jaguar is closely allied to the panther [leopard] and should be regarded as a form of panther that has become specially adapted to forest life. Finally, many of the smaller American cats are so similar to those of Asia that some authors group them together as a sub-genus. At the same time, there are many species common to both Africa and Asia.

The close relationship of cats to one another is further shown by the ability to obtaining hybrids between lion and tiger, jaguar and leopard, leopard and puma and so on ... Hybridization is even easier between the smaller species, which further complicates the matter of classification.

To resolve the issue we would need to have a very large number of specimens of varied origins. This, however, is very hard to achieve because cats, as a rule, live in isolation or in pairs. It is very difficult to observe them closely, and as a result the information on them is very scanty, both in terms of collecting specimens and also in collecting data on their habits.

It is outside of my remit to attempt to give a full list of all the kinds of wild cats here. Nevertheless, a brief description of those bearing on the subject of the domestic cat may be of interest, particularly regarding those species which may be the origins of our domestic cat or which are most easily domesticated.

As a rule, cats are classified in a very arbitrary manner, by length and colour of hair and country of origin. Here is the classification proposed by the French cat fancy:—

1. SHORT-HAIRED CATS

(i) European cats

(a) single colour: blue with orange eyes; white with blue eyes; black, cream, ginger

(b) tri-colour: tortoise-shell, tortoise-shell and white

(c) tabby: ginger, silver, brown

(d) striped: ginger, silver, brown

(e) Carthusian blue (eyes orange)

(f) Russian blue or American blue or Maltese (eyes green)

(g) Manx

(ii) Siamese

(a) blue point

(b) seal point

(iii) Abyssinian

2. LONG-HAIRED CATS

(i) Persian

(a) orange-eyed: single colour: black, white, blue, cream, ginger

two colours: blue-cream, smoke

tri-colour: tortoise-shell, tortoise-shell and white

tabby: ginger, brown

(b) blue-eyed: single colour: white

( c) green-eyed: speckled – chinchilla; tabby – silver

(ii) Burmese [Birman]

Classification might also be made according to head shape. The European cat has a rounded head, with tall ears, slightly open at the base, round eyes and a straight nose. The Siamese and Abyssinian have a triangular head, and in the Siamese the eyes are very “asiatic”. The Persian cat’s head is square, the ears are very small and wide apart, the eyes are round and the nose is very small, short and flat.

BREEDS

There are many fewer different breeds of cats than there are of other domesticated creatures, for example the dog. Nevertheless the question of their origin is equally complex, and proves to be closely linked to the origins of the species itself. The fact that it probably has multiple origins goes to explain the existence of a number of breeds, but does not explain everything. There have been a number of studies written on the subject, but unfortunately many of these were not written recently and we now recognise that they were based on insufficient or inaccurate data.

Many of those writers thought it necessary to trace a definite wild ancestor for every separate breed. There is now no doubt that this approach was incorrect. A comparison with other domesticated species demonstrates that the breeds recognised by the Cat Fancy do not all differ each other to the same degree. Some breeds have specific differences between them, but others are just variations and cannot really be regarded as distinct breeds. Therefore, it is essential to be certain how important a “breed’s” characteristics are before looking for a distinct zoological origin for the breed in question.

In all probability, some cats are still very close to their wild ancestors. This is especially true of the Abyssinian, but even here there isn’t sufficient data to be certain. Siamese cats differ from our own common cats in so many important features that they are said to resemble a distinct wild ancestor. Lack of a tail is not related to any distinct zoological origin. It is simply a mutation, and the trait can also be found in other species.

Other breed characteristics are less obvious than those mentioned above. They are no more than variations from a single type, which can be seen in the bodily proportions. Such distinctions cannot be used to classify breeds, they are still important and worth mentioning.

Many cat breeds depend entirely on coat characteristics termed “markings,” – i.e. length of hair, colour, and patterns. Markings allow us to distinguish two distinct types in the European [his term for Shorthair] cat. The reduction and disappearance of markings gives us cats with uniform colouring (self-coloured cats). This, however, does not touch upon the problem of coats marked not by barring, but by coloured patches.

Numerous authorities claim that Angora and Persian cats are descended from the Manul, as the fur resembles it in terms of colour and length. However fur colour and length are secondary characters and the Angora and Persian differ from the Manul in more important traits. Hairless cats have their origin in a mutation that occurs frequently in other species as well.

Finally, many breeds are classified solely by characteristics of hair colour. From a zoological perspective, this is unquestionably the least important distinguishing characteristic.

Doubtless to breeders such minor distinctions are of huge interest, but that does not alter the fact that they are merely variations, some of which are scarcely fixed at all, since it is very difficult to produce the same colouring in kittens as in its parents.

Due to still-unknown influences, cats generally and easily tend to develop colour variations due to variations in the amount of pigment in the hair. Unfortunately, the reasons for such variations are still unknown which makes the deliberate production of such modifications difficult.

COAT PATTERNS

Taken in itself, without regard to colouring, the European cat’s coat pattern falls into one or other of two categories, which is interesting with regard to the ancestry of the cat.

One type is “tiger-marked”, i.e. the striping on the flanks is vertical, the rearmost stripes tending to break up into flecks of colouring. The stripes along the spine are narrow, and there may be a sort of necklace in front of the shoulders, hence this variety is called Felis torquatus (necklaced cat).

These markings are strongly reminiscent of the African cat.

The other pattern is characterised by bold lengthwise dorsal stripes and especially by three slanting bars on the flanks, the uppermost being very distinct and often repeated behind, the central one often being a mere patch, and the lower one being short. These three bars form a sort of ring, either a closed ring or an open horse-shoe marking. This is the pattern described by Linnaeus as Felis catus and the “English tabby.” It is not known in any modern wildcat species.

We have no indications of the tabby type’s origins. It was unseen in Europe until the end of the 17th century or in America before 1860. It has been hypothesised that this type is descended from a long-extinct fossil species called Felis Zitteli (Boule’s classification): a very small animal remarkably like the present-day domestic cat. This hypothesis is not logical. How can we account for the persistence of hypothetical characteristics, supposed to have existed in a species now known only from fossils? How can we explain these cats having remained unobserved for so long before reappearing? Based on the current information, all we can do is recognize that “such and such” are the facts, but these facts cannot yet be satisfactorily explained.

Regardless of their origin, the important and remarkable fact is that we there are two very different types of coat marking and the animals exhibiting either one or the other. Although they are constantly free to cross-breed, we never see any intermediate markings, only one or the other. This means that the two types must have differentiated a very long time ago and it is likely that each has had a different zoological origin.

Reduction and eventual disappearance of barred markings explains the origin of self-colour cats, but the question of the origin of the various markings remains unanswered.

ABYSSINIAN

This short-coated cat was imported fairly recently from Abyssinia. As far as we can tell from depictions of the Ancient Egyptian cat, the Abyssinian is the breed that most closely resembles it. There has been an Abyssinian Cat Club in the United Kingdom since 1926, and American Abyssinian clubs have been organized.

The first specimens were brought to Europe around 1869, and were described in Dr. Gordon Staples’ book “Cats, Their Points” (1882). He based his description on a cat imported at the end of the Abyssinian War (1868).

The Abyssinian is much like the European wild cat, except in temperament, as it is very gentle, and even timid. It is slow to make friends, but can become very affectionate. It dislikes close confinement and is best raised where it has ample space to roam. It is a lively and active creature and retains its youthful behaviour even at an advanced age. In general it is charming animal, well deserving the attention of cat-lovers.

Standard:

General appearance: The Abyssinian is built along graceful lines. It is on the small side. It has a haughty and dignified demeanour, with an expressive head carried high.

Colour: This is the most important thing when judging an Abyssinian. Its colour resembles that of a hare, except that the roots the hairs are golden red instead of grey. The preferred colouring is a warm, golden hue, with no sign of dullness, and the coat must be uniform, with no evidence of markings, either patches or barring. A serious defect found in Abyssinians is a white neck. One characteristic of the breed is the appearance of two or three coloured bands on each hair. The lower three-quarters of the hairs are a golden fawn colour, and then there are two shades of brown, the darker shade being at the tip. This shading is not found on the centre of the hind rear paws, which are a lovely golden fawn colour throughout their length.

Head and ears: A delicate, triangular head, with ears that are broad at the base.

Eyes: Very expressive, large and round, green, hazel or yellow in colour.

Tail: Long and well-furred, ending in a slight point.

Paws and feet: Very finely built, with little round tips; black in colour, the black continues up the rear portion of the hind feet.

Height: Medium, with very distinguished bearing.

AMERICAN BLUE – See Russian Blue.

AMERICAN COON CAT

A long-haired American variety that got its name because it was once believed to be a cross between an ordinary cat and a raccoon. It generally resembles the ordinary European cat.

ANGORA

For a long time all long-haired cats were called “Angoras”. Nowadays, the term “Persian,” introduced in England, is preferred. However, neither of these terms truly relates to their geographical origin, which is still extremely uncertain. The Angora has a pointed face and slender body; while the Persian has a snub face (like a Pekinese), and a more chunky conformation.

Several authors claim the Angora is descended from the Persian Manul cat. They base this theory on the length and colour of the fur. However, these are secondary characters and the two felids differ in numerous important points. This makes any racial link very doubtful. The Manul has dental features that are not found in the Angora, it has smaller ears which are very wide-set and are position very low down. Finally, the eye pupil of the Manul contracts into a disc, not a slit.

This reputed origin is also improbable, in the light of our present knowledge of the “angora” (long-hair) characteristics. This trait reappears in a number of other species, for reasons not fully understood. Angora goats and angora rabbits are both very common animals. In rabbits, it has been established that the angora characteristic commonly appears occurs in otherwise normal rabbit colonies, and is hereditary. The name given to the angora cat should not, therefore, be considered proof of origin. It was given that name by analogy, because of the silky long-haired goat that is found in Angora. Considering that angora hair appears in other species, some of which are unknown in the East, there is no point in claiming that the ordinary angora is found there any more than anywhere else. There is no historical evidence of this.

It is more likely that this peculiarity appeared spontaneously, and that man subsequently perpetuated the trait by selective breeding. The most one can suppose is that there may be districts in western Asia, for instance, where local conditions are more favourable than elsewhere for the development and perpetuation of the angora characteristic.

The following piece of evidence is somewhat interesting - a letter addressed to the President of the French Zoological Society by M. Lottin de la Val. It dates from a sitting of the French Zoological Society on May 11th, 1856:-

“Sir, When you recently did me the honour of calling on me, you mentioned the commonly held opinion that the so-called ‘Angora’ cat does not, or could not, exist except in the vicinity of ancient Ancyra. I hasten to dispel this illusion. I personally encountered specimens of that lovely species of cat in the great Armenian plateau, at Erzerum, where the climate differs greatly from that of Angora. The variety is very numerous at Mourch in Kurdistan, and is the dominant variety there. I also found it at Billis and in the pashalik of Bayazit. However, the finest specimens I saw belonged to the Archbishop of Van, a town in eastern Kurdistan, on the frontier of Azerbaidjan. He had three of them, one pearl grey, one orange-coloured with black and white markings, and a third which was completely white. Their fur was magnificent, though they were not considered anything unusual there, as such cats are common in Kurdistan. I also saw some at the residence of Khan Mahmoud, Prince of Hekiars, at Alpeit. I cannot recall having seen any in Persia, though, if I had known that scientists were interested, I would have taken care to look for them, despite being busy. But what will surprise you most of all is that despite the high temperatures prevailing in the area, one can find Angora cats at Bagdad, albeit they are not so fine as those found on the northern slopes of the Medique and Taurus mountains; whether the difference is due to the hot atmosphere or to the hostility of the people of Bagdad, I do now know. You will doubtless be able to settle that point better than I. All I can say is that the people of Bagdad are in constant conflict with their cats, maintaining not without good reason, in my opinion, that the cats carry the plague because of their fur coats and their habits.”

BRITISH CAT (see European Cat and Classification).

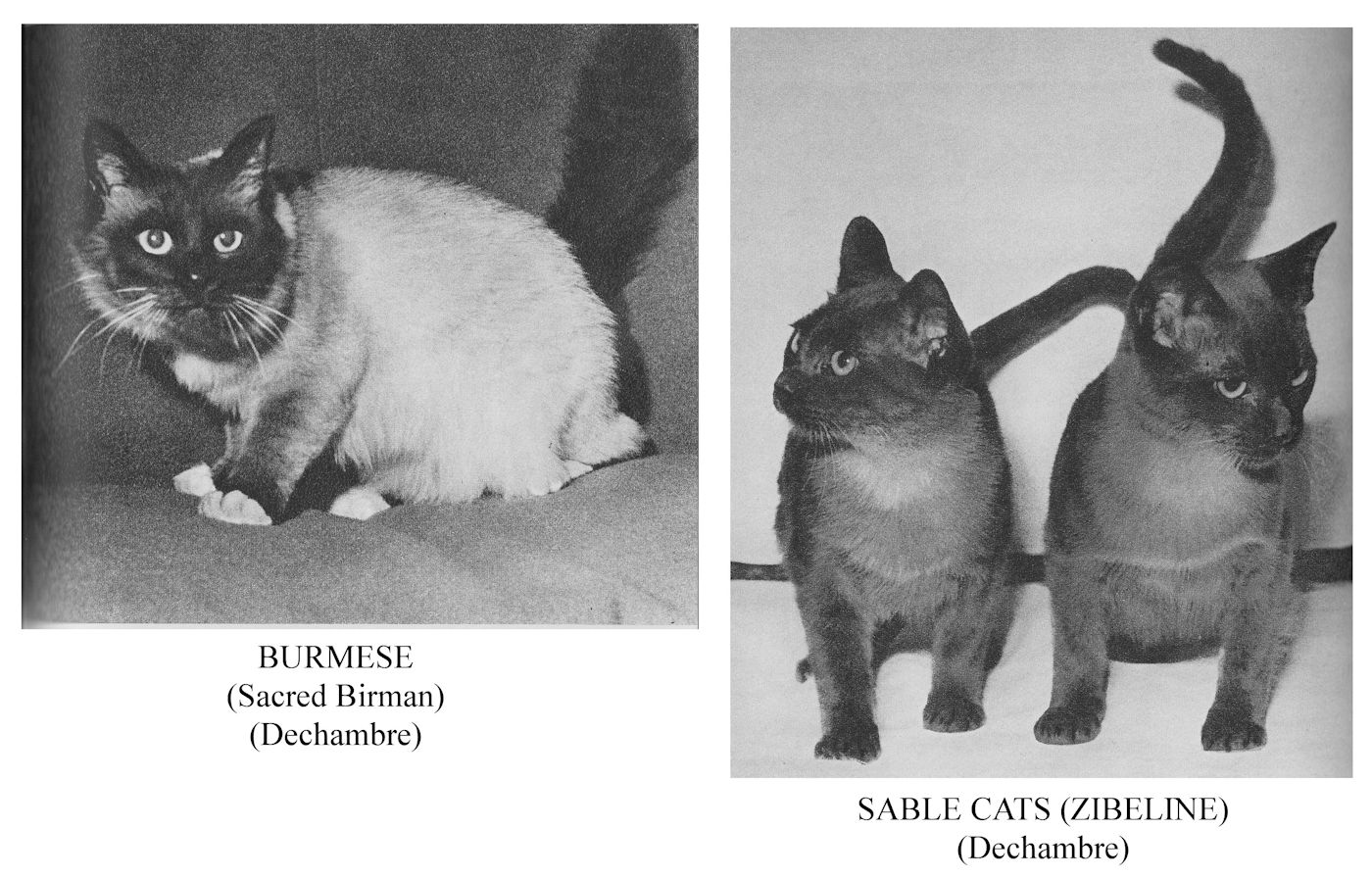

BURMESE

[By which Dechambre meant the Sacred Birman]

This is a long-haired cat. There are legends about its origin which, however pretty, are merely legends. Far too often any long-haired half-Siamese cat gets called Burmese. The fur of the true Burmese varies from medium long to long according to the part of the body. The facial hair is short except for the cheeks. The rather long tail fur fans out in a striking way.

The Burmese [Birman] cat has brown markings similar to those of the Siamese with the remainder of the coat being a very pale cream colour. White gloves on all four paws are essential. Pure white should extend as far as the first phalanx of the fore-paws and form a point at the back of the foot.

Standard.

Body: Lengthy, but massive, low-slung on powerful, well-proportioned, moderately-long legs.

Head: Powerful boning more closely resembles the Persian [i.e. old style] than the Siamese, with a short nose and protruding forehead.

Eyes: Slightly oblique and deep blue.

Coat: Long fur, dense ruff, fanned-out tail fur, silky texture; belly fur is slightly curled.

Colour: The same markings as the Siamese – brown face, paws and tail, but with the dark cream body slight golden in hue. White gloves on the paws; on the hind feet the white comes to a point under the back of the foot. These white markings are an essential feature of the Burmese [Birman] breed.

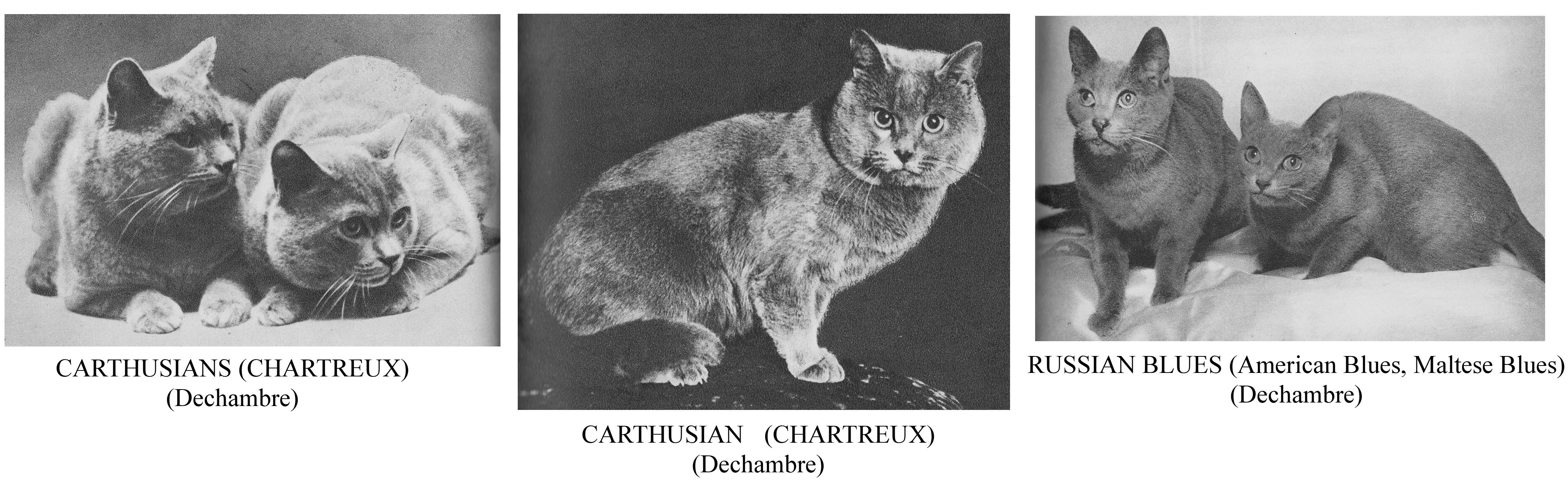

CARTHUSIAN CAT (CHARTREUX)

The Carthusian is one of the oldest cat breeds in France. It is a short-haired, blue, orange-eyed European cat, described by Buffon in his Natural History two hundred years ago. As with most other breeds of cat, there are legends surrounding its origins. Some claim it originally came from South Africa, and was imported into France by Carthusian monks.

Fitzinger claims that it originated as a cross between an Egyptian cat and a Manul. No matter what its true origin, we can say that this breed appears almost only at French cat shows. There may be similar-looking cats elsewhere, such as the British Blue, but even they differ clearly from the Carthusian in bone structure and head shape.

The Carthusian gives an impression of great strength and contrary to some authors, it is definitely not a long, slender animal like the Siamese. It has a massive body, set on long legs, and is most graceful despite its size. Its head fits into a trapezium with the longer of the two parallel sides at the bottom, whereas the head of the Siamese cat fits into a triangle stood on its point. The jaws of the Carthusian are powerful and from about two or three years old its cheeks fill out, becoming slightly jowly. It has a thick neck which merges into broad, powerful shoulders. Its chest is markedly prominent. Every feature of this breed suggests strength.

The colour varies from pale grey to a deep blue-grey. The eyes are deep gold and give the face a very gentle expression.

This cat is gentle, affectionate and intelligent. It is also sturdy and easy to rear in a climate like that of the United Kingdom. It is not worried by temperature changes and its dense coat allows it to resist both cold and damp.

The Carthusian is an excellent ratter. Despite its lazy appearance, it never hesitates to tackle the most powerful rodents.

Standard:

Body: A massive, heavy cat, well-muscled limbs, broad chest, dense, heavy undercoat.

Head: Broad at the bottom, with a straight nose with no stop. Medium-sized ears placed high up on a very rounded skull. Very full jowls. Eyes are yellow to orange.

Coat: Any shade of grey permissible, though the most prized colouring is a very light bluish grey. No shading or markings are allowed, and white fur loses points.

Fur: Very slightly woolly. Dense like that of the otter to the touch.

N.B. Anything suggesting a cross the Carthusian and the Russian Blue should be disqualified.

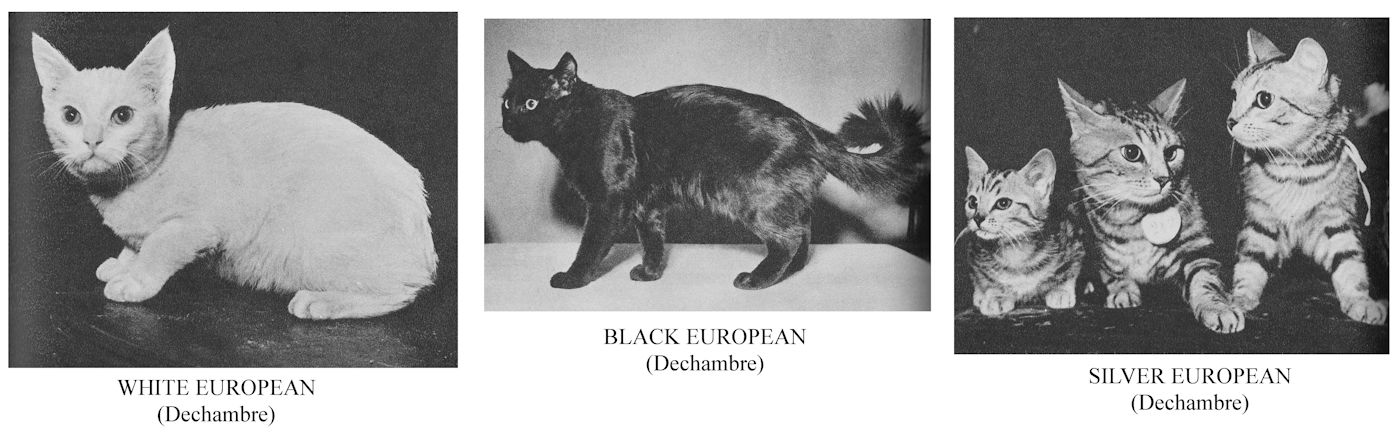

EUROPEAN CAT

This is the name given to a several varieties of domestic cat with short hair and varied colourings, which live in close proximity to man not just in Europe, but in almost all parts of the world. It is the commonest variety found in both town and country. Breeding is frequently left to chance mating. From time to time fine specimens do occur, but it is difficult to establish varieties on a hereditary basis.

One of the distinctive features of the European is its head. This is rounded, with tall ears, somewhat open at the base. The eyes are round and the nose is straight. There are two sorts of body, one slender, standing on long legs, known as the Egyptian, the other markedly cobbier and more compact with a short neck that almost forms one solid block with the head.

European cats are divided into self-coloured, tricolour cats, (tortoise-shells), tabby or tiger-marked. The brown tabby resembles a wild cat, and cats will revert to these markings after a number of generations living wild. Despite this, they differ considerably from the true wild cat, Felis sylvestris, and that wildcat is not considered to be the ancestor of the domestic cat.

Following R. I. Pocock, several authorities agree that there are two distinct strains among our “common” cats. These are their arguments, which are not trivial. Firstly, they point out, it is easy to distinguish two sorts of markings, the [blotched] tabby and the tiger. Pocock concluded that it is the former pattern that Linnaeus described as Felis catus, with its characteristic three black stripes along its back and the spirals on its flanks. These spirals on its sides are characteristic of the domestic cat and are certainly never found in any wild feline. This is a pivotal argument.

The second type of domestic cat is more similar to the African cat, to which it may partly owe its origin. For a long time it was the only cat known in north-western Europe. It is first described in the Swiss naturalist Gessner’s book (1551). Pocock terms this type Felis torquatus, because its markings form a sort of necklace [note: this is the mackerel tabby].

The domestication of Felis catus is unquestionably the more recent of the two. It did not appear in Europe before the eighteenth century and the earliest record of it in America dates from 1860. The two types interbreed and the progeny are fertile. Yet it is striking that the coat markings never combine to give any intermediate forms. One or other always wins, which is further confirmation of the existence of the two varieties.

Following are descriptions of the various recognizable types.

Firstly comes the Self-colour cat, the most widespread of cats. This is our grand old common pussy, which everybody knows. It is a delicate, slender, high-standing, thin-necked animal. According to Professor Swangart, it is often known as “the Egyptian cat”.

Four colourings are recognized: white, black, cream, or ginger (this last is described below.)

Self-colour Black: A very popular cat, considered to bring either good or ill luck as it was allegedly the cat favoured by witches and by Satan. Nevertheless, it is a handsome creature, often used as a decorative detail. A good specimen must have a perfect outline and proportions, bearing and colour. The colour must be jet black, without a single white hair and without any rusty tint; white patches are not permitted. The hair should be dense and shiny. The eyes may be either green or yellow, but the colour should be pure. In the United Kingdom coppery or orange eyes are preferred. The handsomest blacks often have a very snake-like head, with almond slit eyes, less round than in other cats, which a number of authorities attribute to interbreeding with the Siamese.

Self-colour Cream: No markings are permitted. Perfect specimens are very rare.

Self-colour Ginger: The colour should be a fawny ginger, very dark and lustrous, with no hint of markings. This is a very rare variety, which nobody seems to have specially bred or essayed to maintain pure.

Standard for the Self-Colour European Cat:

Body: High-standing, on slender legs, with a long, thin tail, and completely smooth-haired.

Head: Carried high on a slender neck, the nose rectangular, with no stop, a straight muzzle and large ears.

Eyes: Round, very slightly oblique, coloured blue in white cats, otherwise yellow or green (either admissible).

Hair: Very thick and velvety, with no roughness.

Colour: Must not have patches of other colour, or any markings.

European Tabby: The most widespread and most common European Cat, which is found everywhere, as cosseted pet or as rat-hunter in barns. It is very adaptable to different circumstances and when well treated it becomes as affectionate as any other pet cat.

There is an infinite variety of tabby pattern coats, but preference should be given to cats with very clear and symmetrical markings. Bold markings produce a strikingly wild feline appearance giving the distinct impression of owning a small version of a wild animal.

Clear distinction should be made between the true tabby and the tiger-marked cat. A perfect tabby must have three dark stripes along the spine, ending at the tail, which is marked with rings. The head should not have any light markings, and the dark lines should converge on the nose and continue along the cheeks. The chest should be barred with two horizontal stripes, and there is often a third stripe at the base of the neck.

There are oval patches on the shoulders which join up with those on the head and paws to form a sort of butterfly pattern when the cat is resting and is viewed from above. Another pattern on the flanks resembles an oyster-shell.

A white patch on the neck, or a white belly are faults. There should be no heavy jowls to the head.

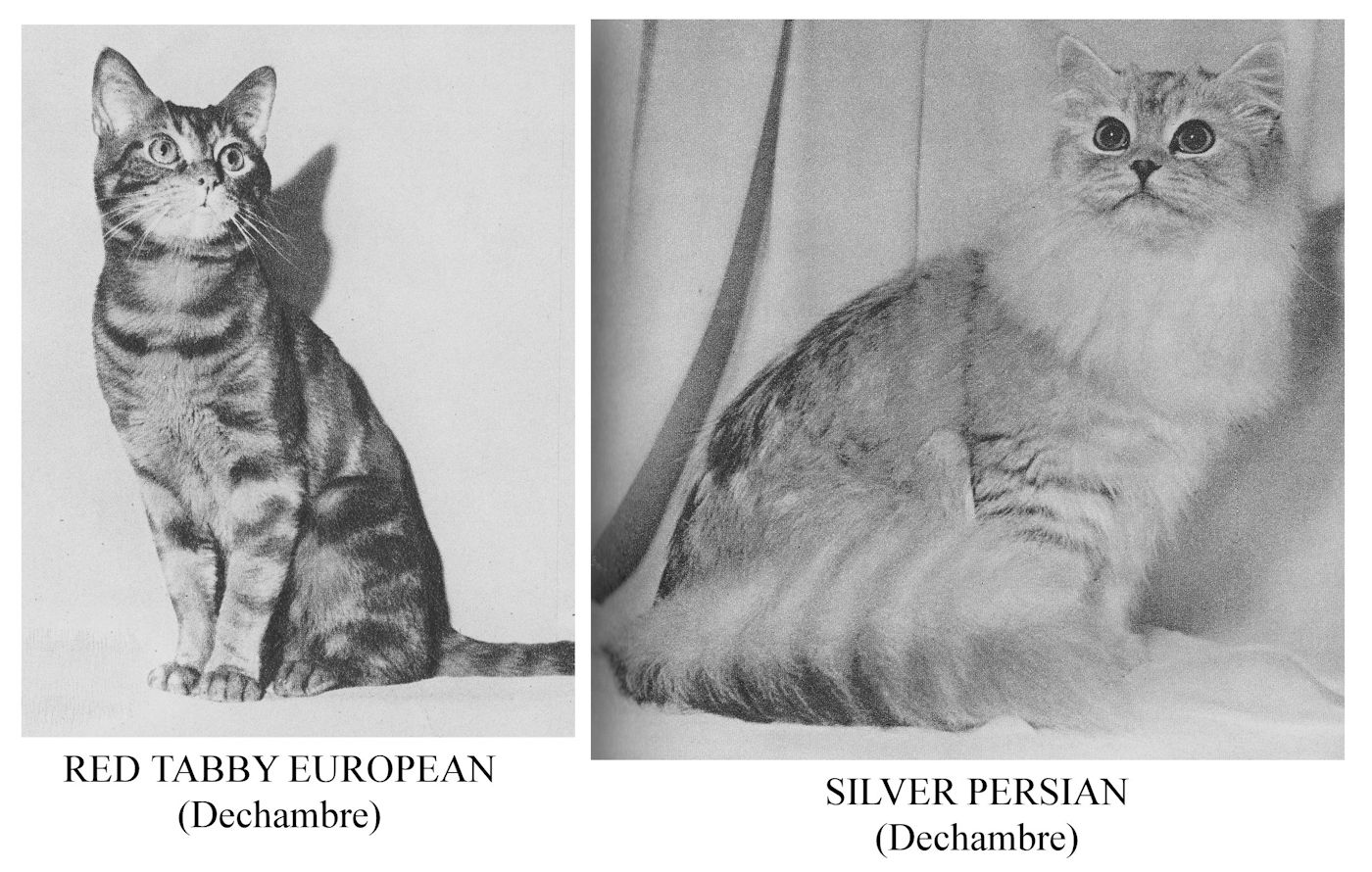

The tabby is a robust cat, rather long in the body, and found in three colour varieties: the Red Tabby with a basic beige colouring and very warm ginger markings, the Silver Tabby with pale grey background and dark bluish-grey markings (very common in Paris) and the Brown Tabby which is fawn with dark brown markings. The latter is the most common of all.

Red Tabby: Careful selection is essential to maintain the features of the coat. To bring out the colour to the maximum, breeders cross the red tabby with a cream strain. Crossing with the Tortoise-shell strain improves the pattern contrast. The kittens have poor colouring during the first six months and their final appearance cannot be assessed earlier than this.

Tiger-marked Cat: The tiger-marked cat should be clearly distinguished from the tabby. As the name suggests, the pattern resembles that of the tiger i.e. stripes from the spine passing under the belly. Many cats described as tabbies are just poor quality tiger-marked cats. The tiger-marked cat is stronger and more compact than the tabby. The neck stands solid with the head. The shoulders are broad and the body appears shorter.

Standards are the same for both the tabby and tiger-marked European Cat.

Colouring: Clearly defined pattern, but not too deep. A bright, warm-looking coat, particularly in the tabby.

Body: Lanky in the tabby, sturdy and compact in the tiger, tail thick.

Head: Finely-drawn and triangular in the tabby, but massive and jowly in the tiger-marked.

Eyes: Most often green, sometimes yellow. Either colour is permissible. The eyes are round in shape.

Fur: Dense and glossy.

Tricolour: The coat consists of hair of three distinct colours. According to the distribution of the colours, we distinguish two varieties: Tortoise-shell and Tortoise-shell and white. An interesting feature of this variety is the great rarity of toms with this colouring, and those which do exist are sterile.

Tortoise-shell: So called because of its resemblance to a tortoise’s shell. Though it seems to consist of only two colours, on close inspection these are found to break up into black, ginger and cream, mingled harmoniously.

Tortoise-shell and white: The three colours of the coat are black, cream or red, and white. White is often the main colour. A coat with the three colours well balanced is preferred. A single all-white limb or a wholly white chest is considered a fault.

This variety is very common near the border of France with Spain, hence its name “Spanish cat”.

Standards:

Colour: These are mainly judged on their colouring, looking for good distribution and balance, and pleasant patterning on the face.

Body: Well-muscled, standing high, but small and delicately built.

Head: Dainty and rounded with a straight muzzle and rounded ears.

Eyes: Yellow or green, very round.

Fur: Shiny and soft.

Self-colour White: The eyes may be blue, orange or yellow, or

occasionally green. Those with blue eyes are most prized, but unfortunately, are usually deaf. The muzzle is delicately formed, and should be snowy white, without any trace of any other colour. This cat not highly favoured, which is hard to understand, because it is very attractive. Perhaps it is due to the difficulty of keeping it white that explains this?

GLOVED CAT

The gloved cat, Felis libyca maniculata, is a sub-species of the Tawny cat (Felis libyca). It is very close to the domestic cat in size, but differs in colouring. Its back is a fawny yellow or yellowish-grey, slightly more reddish behind the head and in the middle of the back, with lighter flanks and an almost white belly. The back is barred lengthwise with eight darker bands, and there are transverse striped markings on the body; these become more defined in the limbs. In various places the body is speckled with black. The tail is fawny yellow in colour with three black rings and a black tail-tip.

This cat is found wild in Nubia. According to Brehm, the domestic cat of the present-day inhabitants of the Yemen resembles the Gloved Cat. In his account of his last journey in Abyssinia, Brehm says: “I observed that the domestic Cats of the inhabitants of the Yemen, and those of the Arabs living on the west shore of the Red Sea, have the same colouration as the Gloved cat and the characteristic grace of that species.”

It is feasible that the people of ancient Egypt had domesticated the Gloved Cat, and it is reasonable to attribute that a number of mummies and Ancient Egyptian depictions of cats to this species. There are various other pieces of evidence supporting this hypothesis of early domestication, and these are supported by the ease with which the Gloved cat can be tamed. For example, Schweinfurth states that the Niam-Niam people do not have domestic cats in the strict sense of the term, but make use of Gloved cats. Children catch the kittens and when tied up close to their huts they soon become tame. When released, they remain close to human habitation and provide a service by cleaning up the countless rodents that infest the homes.

HAIRLESS CATS

Hairless cats exist. Their skin is smooth with a fine grain and many wrinkles, and they occur in various colours. Their general appearance is unattractive. They look thin, have skinny limbs and exaggeratedly large ears. They are rarely deliberately bred, but they have considerable scientific interest.

This anomaly has been studied in more depth in the dog and other domesticated animals (pigs, rabbits, goats, cattle, horses) than in the cat, but genetic studies show that the characteristic is racially lethal i.e. the progeny of two hairless animals are not viable. One parent must be normal, for offspring to be produced, and this explains why there is no pure hairless breed. Cases occur sporadically in many countries, and although a number of geographical labels have been attached to these animals, there is no foundation for the idea that any particular country is home to a special hairless breed of cats. These are simple the result of a mutation that is not related to geographical locality.

MANX CAT

The cat breed found on the Isle of Man, known as the Manx Cat, is a short-haired cat notable for its lack of a tail. They originate from the Isle of Man and have not spread very far beyond the Channel.

The lack of a tail is not the only distinguishing characteristic of this breed; it differs from other European short-haired cats in its coat and in a number of other points. The general shape is curious. Its head is like that of the average European cat, but its backbone is short, and the hind-quarters are very well developed with the hind legs being markedly longer than the front legs. This gives the cat a hopping gait, resembling that of a rabbit. In fact there are amateur geneticists — or humourists — who have asserted that the Manx cat is the result of a rabbit breeding with a cat!

Other equally imaginative suggestions about the origin of the Manx cat have been put forward. One tale says that a feudal lord, to increase his revenues, taxed cats’ tails, and this caused the Manxmen to amputate the tails of their cats in order to avoid taxation. Despite my belief in that some acquired characteristics can be transmitted to the offspring, I am reluctant to admit this as a sound hypothesis. Finally, some authors have suggested they descended from cats imported from the Far East, or from cats that survived the Spanish Armada.

Quite simply, it seems to be that this is a mutation which, owing to the isolation of the island, has established itself. Anouria, (absence of tail), is known to occur in various other, especially among dogs, and tailless dogs have also been seen on the Isle of Man. It is not impossible that there are some special circumstances on this island which favour the tailless mutation.

For exhibition purposes there must be a complete lack of tail and the place where the tail would normally be must instead be marked by a distinct dimple. Nevertheless, in otherwise excellent specimens a very tiny tuft of hair over a scrap of cartilage may be allowable.

The Manx cat is a good ratter, a faithful pet and is also intelligent. It becomes very attached to its master and makes a delightful companion.

Standard:

Tail: Must be absent, though a tiny tuft of hair covering the final piece of cartilage of the backbone is permitted.

Hindquarters: It is important that the hind legs are longer than the front legs. Though very difficult to judge in a cat on show, a hopping gait caused by the difference in the length of the legs is a characteristic feature.

Spine: Very short, giving a very “cobby” cat.

Rump: Very well-developed and well rounded, with deep flanks. Fur: Double coat, very soft and fine.

Head and ears: Like those of the European cat.

Colour and markings: Like the European cat, either a solid colour or classic tabby or tiger markings.

Eyes: Colour is considered secondary to the other traits; in general eye colouring is the same as that of European cats with the same coat colour and pattern.

PERSIAN

The essential mark of the Persian cat is its long, silky coat. It is primarily kept as a drawing-room pet, but it can also be an excellent ratter. Its origin is dubious. Breeders sometimes insist on distinguishing between the Persian and the Angora, classing the latter as the bastard offspring resulting from crossing a Persian with an ordinary cat. Personally I consider this erroneous, although it is feasible that English breeders, who were the first to become interested in the Angora, have succeeded in developing a special type through selective breeding.

Persian cats occur in several distinct colours, which constitute as many varieties as do the markings. However, all these cats conform to the same general type, except that using the Angora as their starting point, British breeders have used inbreeding to create a cat in which the massive build and cobby conformation have become exaggerated into a cat with a powerful, rounded head, a very small but broad nose, full cheeks, well-formed chin, small ears set well apart, and large, round, rather prominent eyes.

The best variety obtained is the Blue Persian, which displays several outstanding features.

General Persian Type:

Body: Cobby, compact, with short, powerful legs, and a relatively short bushy tail, generally carried low, following the line of the back, a posture that gives the cat an aristocratic and disdainful air.

Head: The head fits into a square, with the nose in the centre. A line drawn from the outer comer of the eye towards the top of the skull leads to the ear, which should be small and low-set.

Fur: Very long and silky, with a ruff round the neck and a tuft of hair protruding from the interior of the ear.

Eyes: Very large and round, very pure in colour, whether orange, blue or green — according to coat colour.

BLACK PERSIAN

An outstanding animal although perfect specimens are rare. It is not a cat where mediocrity is allowed. The hair must be jet black, with no hint of rustiness, and the eyes should be coppery. One of the difficulties in breeding Black Persians is selecting cats when they are young. As a general rule, their colouring is poor at that time. It has been found, especially in this breed, that mediocre, badly coloured kittens often develop into fine adults.

There have been many attempts improve the qualities of Black Persians by crossing them with Blues. Fine dark blue Persian queens are crossed with high quality Black Persian sires, and only the female kittens are kept for breeding. Whether these turn out blue or black, they are mated to black sires, and the queens of this second generation, when mated to a Black Persian sire, tend to produce a high proportion of kittens with excellent type and colour, and good eye colour. A number of champions have been produced in this way.

Exhibition Black Persians require for special attention. They must be carefully combed, and must avoid direct sunlight in order to avoid a brownish hue to the coat. Some days before the coat is to be judged it should be wiped with a flannel soaked in a very weak ammonia solution — a few drops only in a bowl of warm water. Then bring up the shine with a very dry flannel.

Black Persian Standard:

Colour: Deep black tight down to the roots without a trace of rustiness or grey or white hairs, and no markings.

Coat: Long and silky, with an abundant ruff and tail.

Body: Cobby and compact, with short, broad feet.

Head: Round and broad, with small, wide-set ears, covered with hair, full cheeks, a broad muzzle and a prominent chin.

Eyes: Large and wide open, pure deep orange with no green ring permitted.

N.B. Up to six months old the kittens are not quite black, but brownish or grey.

BLUE PERSIAN

According to Pietro della Valle, their first importer, the Blue Persian breed is indigenous to the province of Khorassan, in Persia. They did not spread into north-west Europe until the end of the 19. They did not have a class of their own in England until the Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1888. There has been careful attention to improving this variety and it is now the breed which has the greatest number of fine specimens.

It is also the breed that has been most influenced by fashion. Initially a darker colouring was preferred, but now the pale blue tint, without any shadow, and with brilliant coppery eyes, is preferred. This combination is hard to obtain and this has led to close in-breeding among the few specimens available. This will need to be offset now by making sacrifices in secondary points of the standard and giving prime attention its general constitution and health. Careful attention will have to be paid to the queens and kittens.

Properly bred Blue Persians are splendid animals and are currently in great demand. However, they require daily attention. As with other Persians, care is needed to avoid them developing hair-balls. In addition, owners must understand that the coat is very unattractive in the moulting season. At this time any dead hair must be groomed out frequently. This is a simple enough procedure, but it has the disadvantage of producing a cat with short hair for several months. Though a rather unpleasant sacrifice it is the only way of ensuring the cat grows a fine and even new coat. Finally, the tail sometimes has to be bathed separately and then brushed out to give it a fine appearance.

Their strong character makes Blue Persians delightful companions; they seem to delight in showing off their appearance, and appear to appreciate the admiration which this prompts.

Blue Persian Standard:

Coat and colouring: Any shade of blue or blue-grey is permitted, but it must be pure and even all over. The fur should be dense and long with a silky texture, and there should be a long and abundant ruff.

Head: Round with small very wide-set ears, a short, flat nose, a prominent chin, and very plump cheeks.

Eyes: Very dark orange or copper, round and clear, with no hint of green.

Body: Cobby and low-standing, with powerful legs.

Tail: Short and well furred, rather round at the tip.

TABBY PERSIAN

Developed in the United Kingdom, the tabby Persian has gone through some interesting phases. They are currently in fashion. The background colour should be a slightly coppery fawn, with very clearly marked black tiger markings. Greyish blacks should be eliminated, as should any with poorly defined markings. You should, therefore, select a kitten as late as possible. No white markings are allowed, and the eyes should be hazel or orange, but never green.

Tabby Persian Standard:

Colour and markings: Dark or warm sable, the head very faintly striped with black, with two or three distinct spirals on the cheeks. The chest has two thin, unbroken necklace lines, and there is a butterfly-patch on each shoulder. The legs are striped and there are three stripes along the back from head to tail. There are “oyster shell” rings on the flanks, and the tail is ringed.

Coat: Long and silky, with a short, bushy tail.

Head: Broad and rounded.

Eyes: Large and round, copper or dark orange in colour.

CHINCHILLA PERSIAN

It’s worth briefly revisiting the history of the Chinchilla Persian to show how artificial the origin of some cat breeds are. It is one of the most recent breeds to appear. In 1919, a Silver Persian Club was formed in London. They decided to create two classes, one for the pure silver and the other for the shaded silver, but none of the latter type were obtained and there were no entries in that class at shows. On the other hand, judges considered cats with slight shading to be “pure silver” cats. In actuality, it proved difficult to lay down a precise dividing line between the two varieties, and the pure silver cats were given the name “Chinchillas”. Thus silver Persians without any trace of markings began to be called Chinchillas.

For a long time those Chinchillas were rather dark in colour. Then a somewhat lighter colour became fashionable and today the tipped marking of the hairs is reduced to a faint shading. Breeders are a little haphazard in their crossings, and as a result this variety is not precisely fixed in either conformation or in coat, and really successful specimens are rare.

It is difficult to select these as kittens, as they are born dark and often have markings, but as their fur grows longer, the shading diminishes. It is only at six to eight months old that you can properly judge the qualities of a chinchilla, since it is not until then that the colour of the coat or eyes have acquired their full brilliance.

Chinchilla Persian Standard:

Colour: Lower part of hairs pure white. Any shading or any patches of colour are to be disqualified, as are any hairs that are black throughout their length. The sides, head, ears and tail should be slightly tipped with black. The legs should be shaded but not marked. The chin, and ear tufts should be pure white. The nose is brick-red and the eye rims dark brown or black. The same goes for the paw-pads.

Head: Round and broad, with small, tufted, wide-set ears, a short nose, and round, full cheeks.

Body: Massive and low-set.

Eyes: Large and round, very expressive, emerald green or dark blue-green in colour, with black or brown rims.

Coat: Long and fine in texture, with a very long and dense ruff.

Tail: Short and full.

CREAM PERSIAN

This is a much sought after and valuable variety, of recent origin. Earlier this century, the colouring was darker, so much so that nobody considered calling it “cream”. It was a light fawn colour. Through careful selection, English breeders developed a cat with outstanding proportions and colouring. This would best be called “old ivory”, straw yellow or very pale fawn. It was obtained by various crossings, according to breeders. As a result of crossing, it is a well-established variety, its only failing being excessive in-breeding. It is advisable to avoid further inbreeding of cats that are closely related. However, it is still difficult to find a Cream Persian with a faultless coat, i.e. a coat that is a uniform colour all over. Far too many specimens are dark on the back, and other are a dull, pale cream.

Cream Persian Standard:

Colour: Very pure, pale cream with no hint of tabby markings.

Coat: Long and silky, tail short and very bushy. A tuft of white at the tip of the tail is a fault.

Body: Cobby and heavy, on strong, small feet.

Head: Powerful and round, small, tufted, wide-set ears.

Eyes: Large and wide open, dark orange in colour.

BLUE-CREAM PERSIAN

This is a very difficult variety to obtain, and presents great difficulties, both for judges and breeders. Its standard was not recognized till 1930, and up till then the blue-cream was considered an “irregular” cat. Since 1930, the standard has remained unchanged, though there has been much disagreement between breeders and judges. The main difficulty is the exact shade to be aimed at. It should consist of blue and cream completely intermingled, with no markings hinting at tortoise shell. However, most specimens have had some distinct patches of colouring, at least on the face and the top of the head.

Another remarkable feature is that only females appear in this breed. As with tricolour cats, males are very rare, and the few males that are bred appear to be sterile. Most breeders only make use of the blue-cream for the purpose of improving the cream Persian. This is an experimental breed which is mainly of interest for dedicated breeders and for lovers of or rare cat breeds.

Blue-Cream Persian Standard:

Colour and marking: A subtle intermingling of blue and cream, without any markings.

Coat: Long and silky.

Head and type: Head large, with small, fluffy, wide-set ears, a broad, short nose, and plump cheeks.

Eyes: Large and wide open, orange or copper in colour.

Body: Short and massive, set low on powerful legs.

RED TABBY PERSIAN

This handsome variety is especially prized in the United Kingdom and the United States, where there are some outstanding specimens. The colour should be very warm and coppery, like that of an Irish Setter. Many are too pale and the two colours, pale copper marked with mahogany red, are not sufficiently distinct.

The markings and pattern are the same as the European tabby. Crossing a cream with a red tabby may bring out the redness, but the best results are obtained using a black queen and a red tabby sire. This gives a warmer colouring, with more distinct tabby markings.

Red Tabby Persian Standard:

Colour and markings: Deep rich red with clear, well-defined markings all over the body.

Coat: Long and dense, the tail short and light, without any white tip.

Body: Massive and cobby on short legs.

Head: Broad and round, with short, tufted ears, short, broad nose and full cheeks.

Eyes: Round and large, copper-coloured or dark orange.

RED PERSIAN

True red Persians are very rare and may have completely disappeared. They are sometimes confused with the red tabby Persian. The difficulty is in the colouring, which should be uniformly rich ginger and not a dirty cream.

Red Persian Standard:

Colour: Warm ginger, without any tabby markings or brighter patches.

Coat: Long and silky. Profusely furred short tail.

Body: Cobby and heavy on short, strong legs.

Head: Powerful and round, small wide-st ears, short, broad, nose, full cheeks.

Eyes: Large and very open, dark orange in colour.

SILVER TABBY PERSIAN

Once much esteemed, the Silver Persian is in decline, becoming less and less common. The basic colour is the same pale silver as the Chinchilla. The markings are those of the tabby: striping on the head, dark rings on the tail and legs, “oyster shells” on the flanks and a butterfly marking on the shoulders. There has never been agreement about the eye colour of the eyes. Should they be green, or hazel brown? The Standard allows for either.

Silver Tabby Persian Standard:

Colour: Silver grey with black tabby markings. Any hint of brown is a fault.

Head: Round and powerful, small, wide-set ears, short nose.

Body: Massive and cobby, low-set.

Tail: Short and well furred.

Coat and condition: Silky in texture, long and close-lying, with a very long “waistcoat”.

SMOKE PERSIAN

The Smoke Persian is a very fine cat, attractive to the cat-lover and breeder alike. With its silvery under-hair, the head and face black in hue, and fine coppery eyes, it is a most pleasing animal. Breeding it, however, is a thankless pursuit. The Smoke Persian is the result of crossing, and it is difficult to establish the colour. Some breeders get it by crossing black and silver Persians, others by mating a black queen with a smoke sire, while yet others use a blue queen with a smoke sire.

The kittens cannot be judged until about six or seven months old when their coats and eyes assume their final colour. There are two kinds of smoke Persians - the black smoke and the blue smoke. Both are allowed. The standard and scale of points are the same for each.

Smoke Persian Standard:

Colour: The body is black or silver-blue on the sides and flanks, the face and the feet are black or blue, there are no markings, and ruff and ears are silver coloured, with white undercoat.

Coat and condition: Long, thick, silky fur with very long “waistcoat” hair.

Form: Head broad and round, small, tufted ears, cobby body, with no tendency to coarseness, low-set.

Eyes: Orange or copper, round, with a refined expression.

Tail: Short and thickly-furred.

TORTOISE-SHELL PERSIAN

Just like the European tortoise-shell, the tortoise-shell Persian is invariably female. It is a very attractive variety, much sought after by cat lovers, though not yet established as a breed since a queen will have a very varied litter. The most characteristic type is the queen mentioned by Mrs Soame which had five kittens: one ginger, one cream, one tortoise-shell, one black and one blue-cream.

The colour consists of black, ginger and cream, and should be bright with the three colours well distributed over the body and limbs.

Tortoise-shell Persian Standard:

Colour: Three colours, black, ginger red and cream, in distinct markings, but in a balanced way, without any very large patches of any colour, all the colours rich and bright.

Coat: Long, silky hair, with a profuse ruff.

Body: Massive, on short legs.

Head: Broad and powerful, small wide-set tufted ears.

Eyes: Large, round, yellow or orange.

TORTOISE-SHELL AND WHITE PERSIAN

A very attractive variety, and as with other tortoise-shell cats, only females are found. The ideal colouring is a mixture of black, yellow and orange, in patches on head, back and tail, with a white chest and some touches of white on the lips, limbs and ruff.

Tortoise-shell and White Persian Standard:

Colour: Black, cream and ginger, with the white well-spaced between the other two colours.

Coat: Long and silky, with a long, dense ruff.

Body: Massive, on short legs.

Head: Broad and strong, small wide-set tufted ears, short broad nose, and full cheeks.

Eyes: Large, round, orange or yellow.

WHITE PERSIAN (BLUE-EYED)

White Persians are directly descended from the ancient White Angora of Asia Minor. In the United Kingdom the ancestral Angora has been improved to create the standard Persian type.

The first cats imported from Asia Minor had blue eyes, and this is still found in the ancestral type.

The coat should be silky in texture and long, close-lying, and light, with a fine ruff and a puffed-out tail. The colour is absolutely pure white, without any hint of cream. Maintaining the coats of these cats is quite a task. This is usually done with frequent brushing and combing, using white powder, but when showing there must be no trace of powder in the coat as this may lead to disqualification.

Originally, only blue-eyed Persians were allowed, and the required eye-colour was a very intense sapphire blue, and not a watery blue. Unfortunately, this is now quite rare. Very often blue-eyed White Persians are deaf. There seems to be a connection between the colour and this disability. Nevertheless, rigid selection has made it possible to eliminate this defect.

Blue-Eyed White Persian Standard:

Colour: Pure white, with no markings or shading.

Coat: Long and silky over the whole body, with well-covered ruff and tail. The hair should be soft and dense.

Body: Cobby with heavy boning, and low set.

Eyes: Large, round and very open. The required colour is an intense sapphire blue.

WHITE PERSIAN (ORANGE-EYED)

Recently, orange-eyed White Persians have been bred and found favour among cat lovers. The eyes should be dark orange or, preferably, a dark coppery colour. The shape should be perfect — small or oval eyes must be rejected.

Orange Eyed White Persian Standard:

Colour: Pure white, without any marking or shading.

Coat: Very silky, with very dense ruff and thick tail; the hair should not be light, not woolly or stiff.

Body: Cobby and compact, on very powerful, short legs.

Head: Round and broad, with small, well-spaced ears, a short nose and full cheeks, with a broad muzzle.

Eyes: Round, very large and open, small eyes being a fault, and in colour dark orange. Pure yellow eyes are allowed.

PIED CAT

A pied cat is one with large patches of colour on a white background. Occasionally we find cats with this pattern and although they are attractive and interesting, Pied Cats are not selectively bred and are not recognised as a variety for exhibition.

RUSSIAN BLUE (or American Blue or Maltese Cat)

These are three names for a European short-haired, self-coloured blue cat with a slender build. It is common particularly in Britain, the Scandinavian countries and the USA. Nothing is known about its origin. The Russian Blue is sometimes confused with the Carthusian (Chartreux) cat, but the two races are quite distinct. Firstly, the eyes of the Russian Blue are green, whereas those of the Carthusian are yellow. The proportions of the two types are also different: the Russian Blue is slender, like the cats of Ancient Egypt, with fine lines and a light build which gives it a very feline appearance.

Its head is triangular, like that of the Siamese, and its ears are tall and close-set on a narrow skull. A lithe, slender neck on graceful shoulders combine to give this breed a delicate appearance. It has a long body that ends in a slender tail. It has a sleek short-haired coat; the hair is glossy and close-lying, like that of a mink. In colour it does resemble the Carthusian, being grey, and this explains the frequent confusion between the two breeds. The eyes are emerald green, slightly almond shaped and set at a slant. It is as good a hunter as the Carthusian, but its light of build, puts it at a slight disadvantage.

Standard:

Body: Very slender, standing high on slender legs. The neck is delicately made and slightly bent forward. Tail is long and slender, and quite silky. Its stance is an important characteristic of the breed.

Head: Narrow and slightly rounded at the top, forehead receding, no stop, V-shaped muzzle, ears are large but are narrow at base. The head is carried high.

Eyes: Slightly oriental slant, colour pale or emerald green.

Hair: Loose-lying, a little coarse, but lustrous.

Colour: Preferably blue-grey all over, although any shade of grey is permissible, but patterning or white hair is not tolerated.

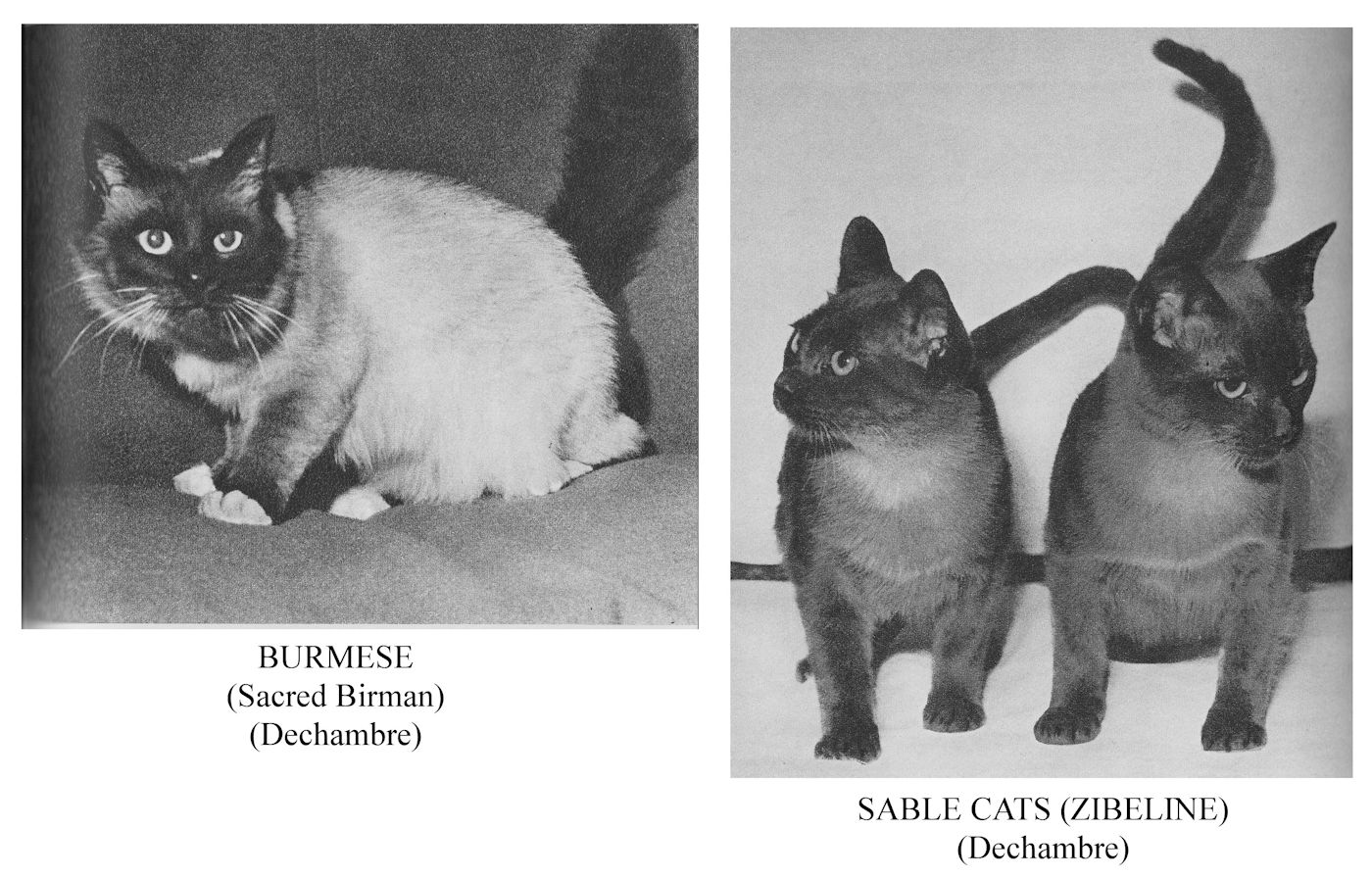

SABLE CAT

This variety was created in America, where it is known as the Burmese. Is better to call them Zibelines or Sables, because of their coat, and to distinguish them from the true Burmese [Sacred Birman]. Without a doubt, the Sable cat was derived from crossing a Siamese with one or more other breeds, either in the United Kingdom or America. It is a short-haired, self-coloured, chocolate brown cat, with green eyes and a long tail. The hairs are the same colour all along their length, in contrast to the Siamese, which has various degrees of shading.

SIAMESE

A short-haired cat with distinctive features, both in colouring and body. There are two kinds, the so-called seal point, and the blue point.

SEAL POINT SIAMESE

The face, ears, paws and tail are dark brown. The fur on the body is fawny brown on top, lightening to cream underneath.

The head should show a regular, pointed outline, reminiscent of the marten’s head. The ears are wide-set and flared at the base, giving its face a strikingly eager appearance. The hind legs are slightly longer than the front. When standing, the Siamese looks as if it is ready to spring.

The question of the tail conformation has caused arguments among Siamese cat lovers. Originally, a broken, stunted, atrophied tail was considered a sign of breed purity, but this is no longer the case. As a general rule the normal tail is recognized and the kink is considered unattractive. A short or a corkscrew tail is not aesthetically pleasing and a long, untruncated, flexible tail completes the cats outline far better. The long-tailed Siamese has now definitely won the day.

The coat colouring varies with age and also with the environmental temperature. The kittens are born almost white. The first brown markings soon appear, and become gradually more defined, but the full, darker development of this feature is not complete till the animal is about one year old. Even at that age, the face has often not acquired its full colour and character. As a rule, the colouring tends to darken with age, but on the other hand, in elderly Siamese cats it sometimes grows lighter again.

The most sought after eye colour is sapphire blue. This is a difficult colour to keep in a breed and some sacrifices may be necessary to achieve it. Cats with sapphire blue eyes tend to have points that are too dark in colour, and their belly may be a dirty white colour.

Siamese cats differ from ordinary domestic cats by some important features, and we can probably assume they have a specific wild ancestor.

First of all, their coat is very distinct. However, there are more important physiological differences. Siamese cats and ordinary cats do not get along very, and may even show a distinct aversion for one another. Their voices are also different. Another point of difference to which attention has only recently been drawn is the ovarian cycle, which is different in Siamese and other cats. In the Siamese, there are heats through the greater part of the year, and these last from 8 to 12 days, with intervals of about ten days, whereas in the ordinary cat there are never more than four, and most usually only two, periods of oestrus, and these last only 4 to 6 days each.

There is also a difference in the length of gestation. In the Siamese this lasts from 65 to 68 days (the figure given by various authors varies), compared with about 64 days in other cats. Surprising though it may be, it is not always easy to establish the exact gestation period of a species, as there can be some error about the date of conception. In the case of the cat, this is assumed to be the date of the first mating during a heat.

At the same time, we know of no wild species from which the Siamese could be descended. Some authors even think that the coat was once striped, because young Siamese may show traces of markings. There has been much enquiry into their origins, and many hypotheses have been advanced, but this remains a mystery. On the other hand, we know precisely how and when these cats were first brought to Europe.

The first arrivals were a pair brought out of Bangkok in 1884 by Owen Gould. Their names were Pho and Mia, and their progeny carried off first prizes at the 1885 Crystal Palace Cat Show. Two other early Siamese are more famous, Tiam o-Shian and Susan, belonging to Miss Forestier Walker, were imported in 1885. According to the register of Siamese cats, half the Siamese cats of the United Kingdom are descended from the latter pair.

Curiously, there is no precise information about the tails of these first Siamese, but certainly one specimen which was imported in 1887 is described as "a bobtail cat”.

The first scientific study of these cats was that made by Professor Oustalet, of the Museum of Paris, which appeared in 1893 in the pictorial magazine “Magasin pittoresque.” Oustalet mainly describes the young Siamese which had just been given to the Botanical Gardens menagerie by Madame Carnot, wife of the French President. Other specimens were presented to the menagerie in 1885 by M. Pavie, at that time the French Minister Resident in Bangkok. The description corresponds to the cat we know now. Regarding the tail we read: “The tail is round and slender”. The description continues: “With their slenderness and their long, thin tails and strange colouring, the cats of Siam are so different from all those we are used to seeing in our homes and so like any other felines in the wild state in the forests of Indo-China that nobody can tell to which breed, wild or domesticated, they should be assigned”.

The imported adults settled down very well in their new environment, but there was little in breeding efforts. As often happens in such circumstances, too many precautions produced too artificial an environment. The fact is, these cats need a great deal of room. They must have clean housing and above all they require human company. Contrary to general belief, they are very fond of being caressed and become very attached to their masters, though this does not prevent them from having a very different temperament from the ordinary cat. They are extremely independent, which some consider a fault, while others find it a positive feature.

There are no particular difficulties in rearing Siamese; it merely requires patience and perseverance. You have to take account of their mind-set. Although domesticated a long time ago, the Siamese cat retains something of the feline of the jungle in its character.

The Siamese becomes very attached to its owners, and has a marked tendency to be jealous. Its liveliness and agility are striking, and can be dangerous to your curtains and upholstery. These features, which some consider faults, make it an interesting cat, which can occupy an important place, both in the household and in its masters’ hearts. Cat-lovers who have once kept Siamese cannot easily do without them.

There is one difficulty in the task of breeding — choosing kittens cannot be done early. They are born an ashy white colour, and their brown markings don’t appear till later, and grow steadily darker with age. This is connected with their food. If you want a light-coloured cat, it should not be fed almost exclusively on raw meat.

As a rule a generally light coloured coat is preferred as this brings out the dark markings better. This is obtained by methodical selection, making it possible to have cats that remain light in colour to an advanced age. But it is difficult to tell before six months, and can be difficult even at 14 months, whether a kitten will have good markings. In the adult cat, especially in the blue point (q.v.), the colour fluctuates from year to year may be observed. An adult cat which has darkened may become lighter again, then subsequently darken once more, without any change of diet.

Though the opposite is sometimes asserted, their diet need not differ greatly from that of the common cat. They are exceptionally fond of fish. Raw meat is also indispensable from time to time. The Siamese is a born hunter and will wreak havoc on mice and rats. Unfortunately, it is also very fond of small birds.

Standard:

Build and shape: Moderate in size, with a long, lithe body and delicately-made legs. The hind legs are slightly longer than the front. The paws are small and oval, the tail long, thin and whip-like. A normal-length tail with a slight crook in it is permitted.

Head: Long and well-proportioned, fitting into a triangle (front view), broad across the eyes, pointing towards the muzzle, the ears are rather close, large, broad at the base, and pointed.

Eyes: Very wide-set, large, bright, pure in colour, oriental-looing, sloping to the nose, and intensely blue. Squinting is a fault.

Colour and markings: The general colouring is cream, fading to off-white on the belly. The ends of the legs and the feet, the face and the tail are chestnut and should be distinctly delineated, no white patches are tolerated. The kittens are pale and lack these markings.

Hair: Very short, with a fine texture, glossy and close-lying.

BLUE POINT SIAMESE

This variety has been selectively bred mainly in the United Kingdom, where it is very popular. The only difference between the blue-point and the seal point is in the colour of the markings. Instead of chestnut-brown, the darker patches are blue. The coat is generally silvery beige and the blue colour brings to mind Copenhagen porcelain. Otherwise, the standard is the same as the seal pointed Siamese.

TAILLESS CATS

Absence of a tail is not related to any distinct zoological origin. It is a mutation and, as such, it can also be found in other species. Tailless cats have been noted at various times in a number of countries. They are common in ancient Japanese and Chinese prints. They have been found in the Crimea. In 1907 Saint-Blancard found a fairly large number of failless cats in Touraine, between Amboise and Vouvray.

For reasons we don’t know, pure-breeding lines of tailless cats have arisen, the most notable being the MANX cat from the Isle of Man.

Atrophy of the tail is not always complete and various degrees of near-tailless cats may exist. Tailless cats are sometimes called Malay cats, but there is nothing to justify this name. It is no more than a variation.