THE CAT IN THE MYSTERIES OF RELIGION AND MAGIC

By Mary Oldfield Howey

Author Of “The Horse in Magic and Myth” and “The Encircled Serpent.”

Philadelphia

David Mckay Company, 604-608 South Washington Square

PLEASE note that there is an exhaustive bibliography of authorities consulted at the conclusion of each chapter, so that it is possible for the student to confirm every statement, whilst the ordinary reader is not annoyed by constant footnotes.

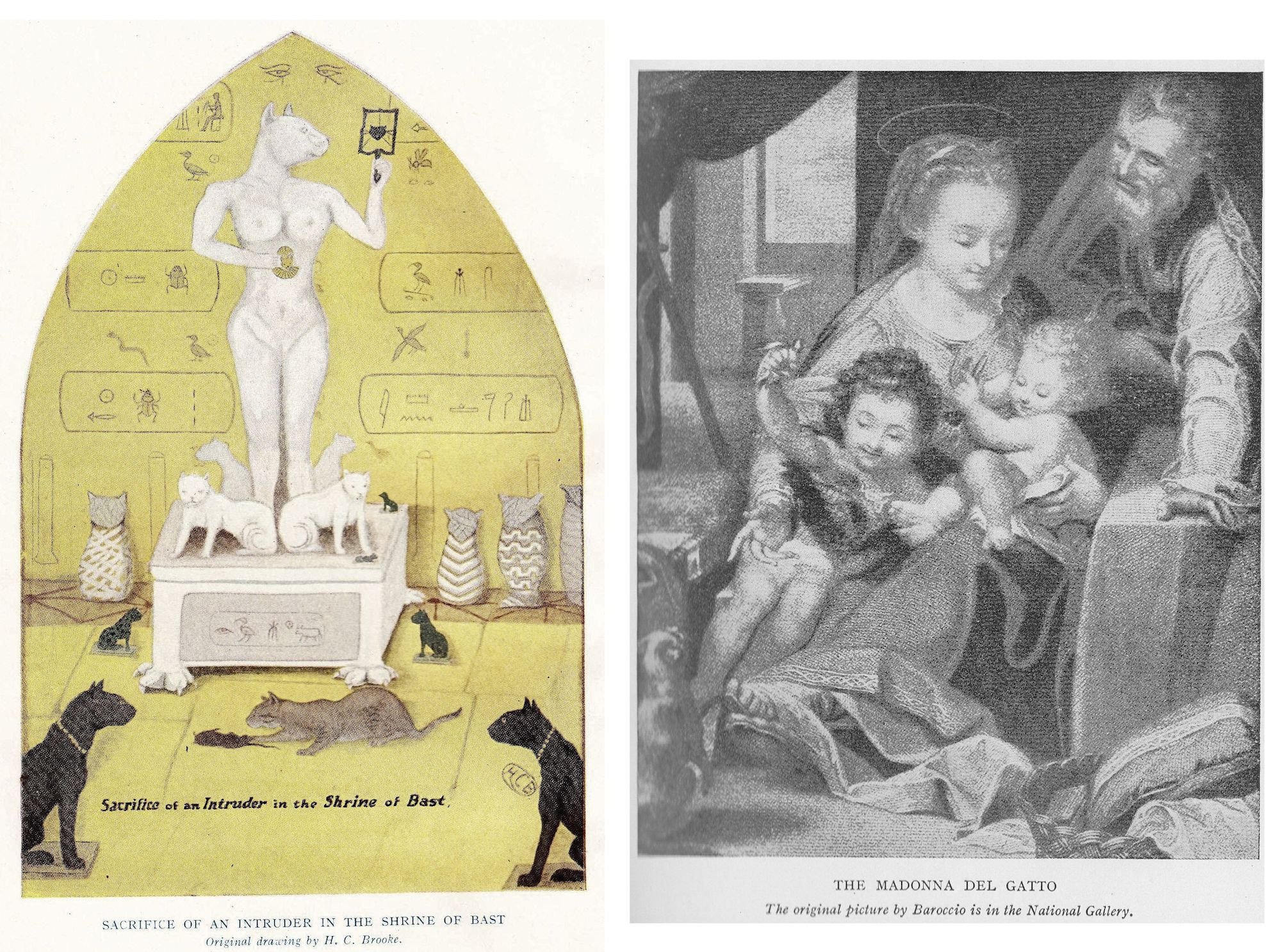

My thanks are due to Mr. H. C. Brooke, the well-known cat fancier and first editor of “Cat Gossip” for permission to include some of his valuable literary and artistic contributions to the subject.

INTRODUCTION

“MAN created God in His own image,” was the dictum of Voltaire, but the Gods have not always been visualised by man in human form. In comparatively early stages of religious evolution it became apparent to the devotee that man as man could not adequately symbolise or personify the conception of divinity innate within him. Among primitive peoples life is intimately interwoven with religion, and every concrete object of perception is recognised as an idea and manifestation of the Creator God, and therefore as a claimant for man’s awful [awe-inspired] reverence. Beasts, birds, fish, reptiles, and even insects, plants, and stones, and monstrous forms of imaginative fantasy, have all been seen by poet primitives as images of attributes of the Infinite.

Thus a fundamental equality of all things animate or inanimate was first accepted; but profounder study proved that certain forms presented such many-sided facets that they outshone all lesser lights, and in themselves conveyed to their observer something of the all-inclusiveness of the Divine. One of such symbols is found in the Serpent, as I have endeavoured to prove in a former volume, but another most outstanding example of a multum in parvo emblem that, because of its essential appropriateness, has persisted millenniums beyond the age in which it took birth, is the subject of this present study, the Cat. The Cat, like the Serpent, conveys, though necessarily imperfectly, the thought that God is All. Such a stupendous conception involves the examination of many totally distinct, and even apparently antagonistic aspects which can only be unified by that single thought. Therefore my readers must pardon any lack of sequence that may obtrude itself in this study. The Cat is the symbol of Good and of Evil, of Light and of Darkness, of Christ and of Satan, of Religion and of Black Magic, of Sun and of Moon, of Father, Mother, and Son. It will repay our investigation because of the vastness of the vistas upon which it opens rifts in the veil. The subjects to which the Cat Symbol introduces us are themselves so tremendous that scarcely one of them could be exhausted by a lifetime's exclusive devotion, so of course no claim of completeness is made for this work. But absolutely inadequate as it must be in relation to its theme, I believe it still contains much that will be found of absorbing interest both to the general reader and to the student of Life’s mysteries. – M.O.H.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

2018 FOREWORD

I. BAST

II. SEKHMET

III. THE SISTRUM

IV. THE CAT AND THE SERPENT

V. THE CAT AND THE RIDDLE OF ISIS

VI. THE CAT IN CHALDEAN AND EGYPTIAN MAGISM VII.

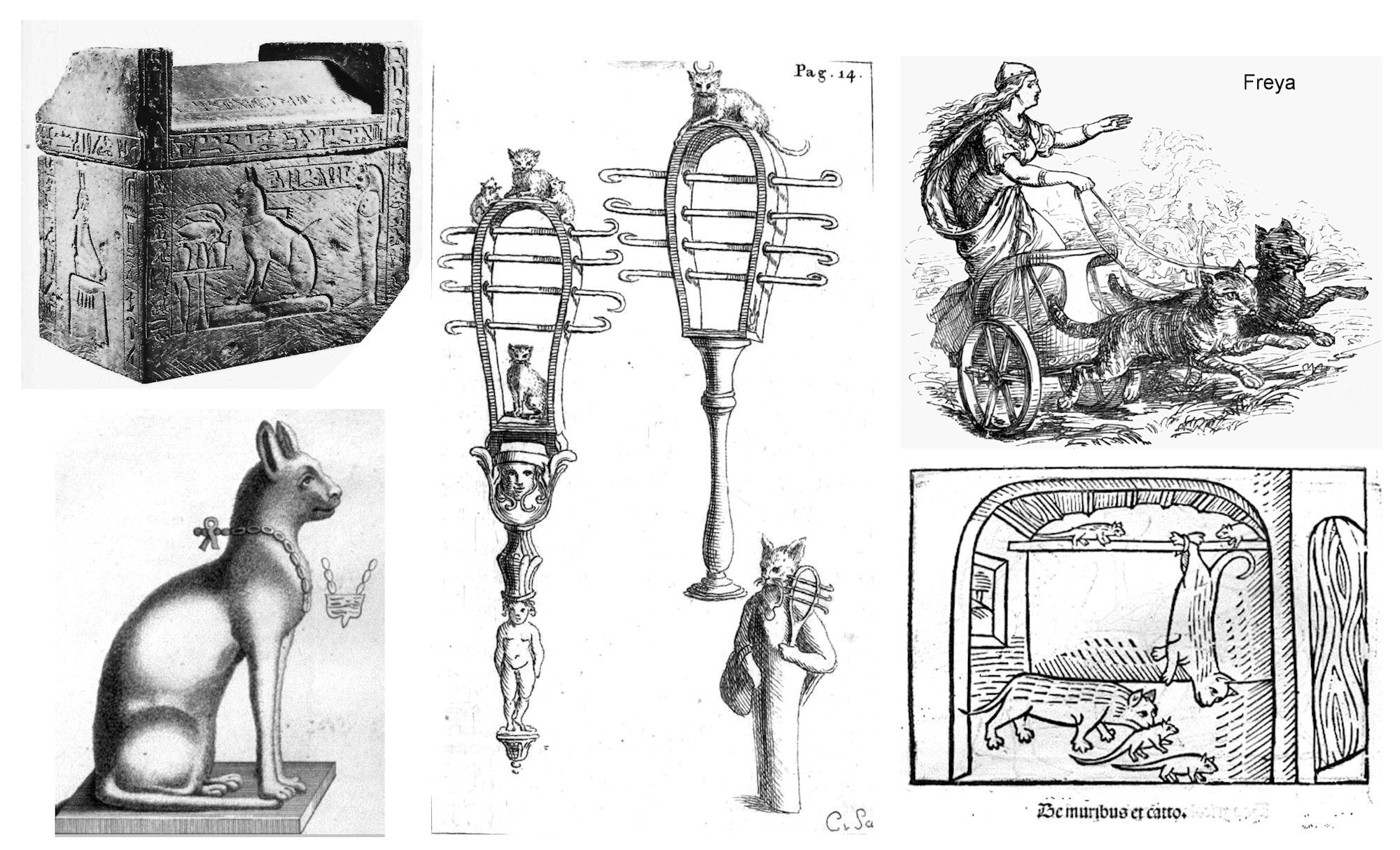

VII. FREYA AND HER CATS

VIII. CHRIST AND THE CAT

IX. THE VIRGIN AND THE CAT

X. THE MAY KITTEN

XI. THE CORN CAT

XII. THE CAT AND THE SABBAT

XIII. WITCHES IN CAT FORM

XIV. WITCH CATS AND REPERCUSSION

XV. SECRET SECTS AND CAT WORSHIP

XVI. THE CAT AS SACRIFICE

XVII. THE CAT AND TRANSMIGRATION

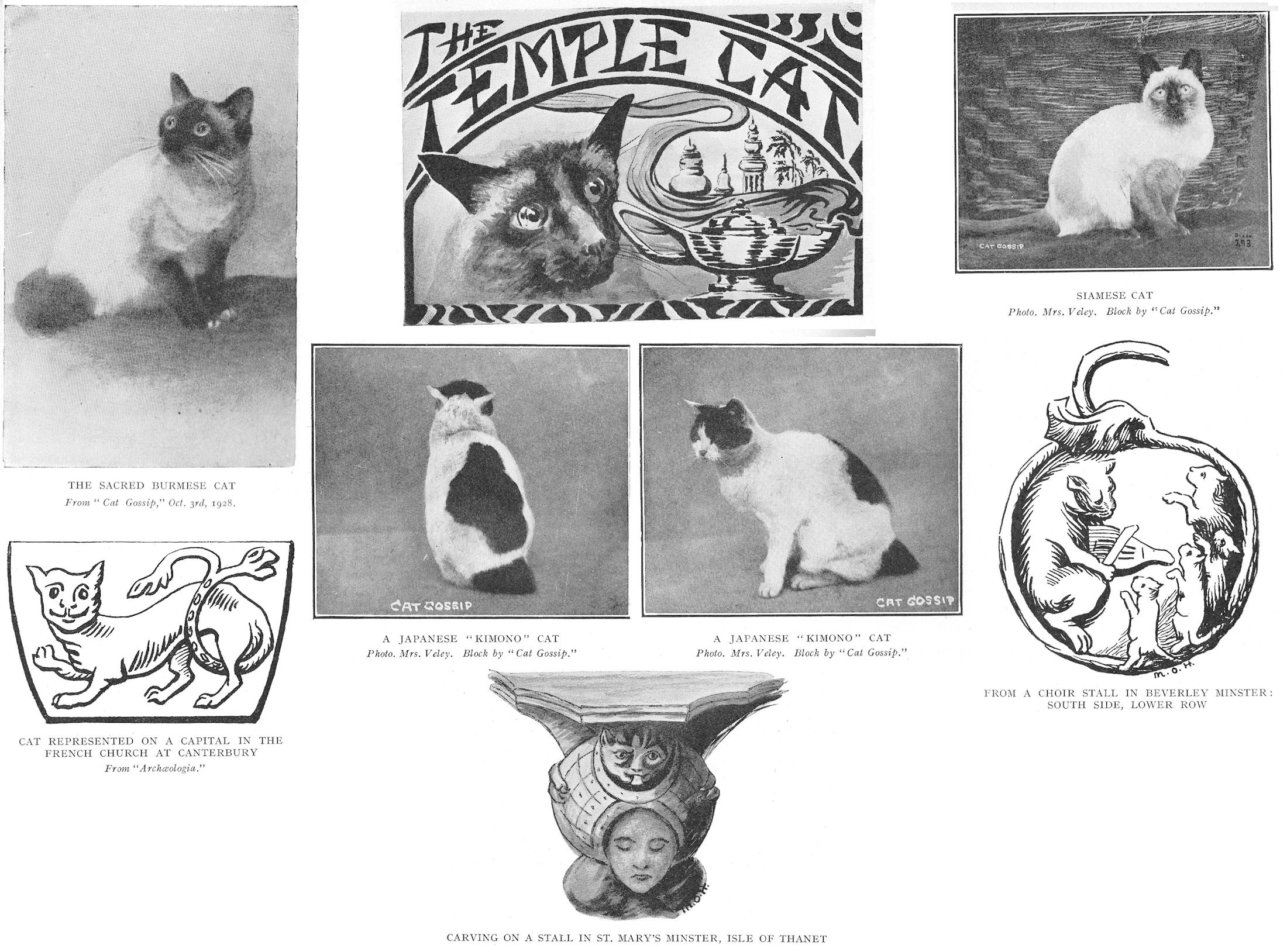

XVIII. THE TEMPLE CAT

XIX. ANIMATED CAT IMAGES

XX. THE CAT IN THE NECROPOLIS

XXI. THE CAT IN PARADISE

XXII. GHOSTLY CATS

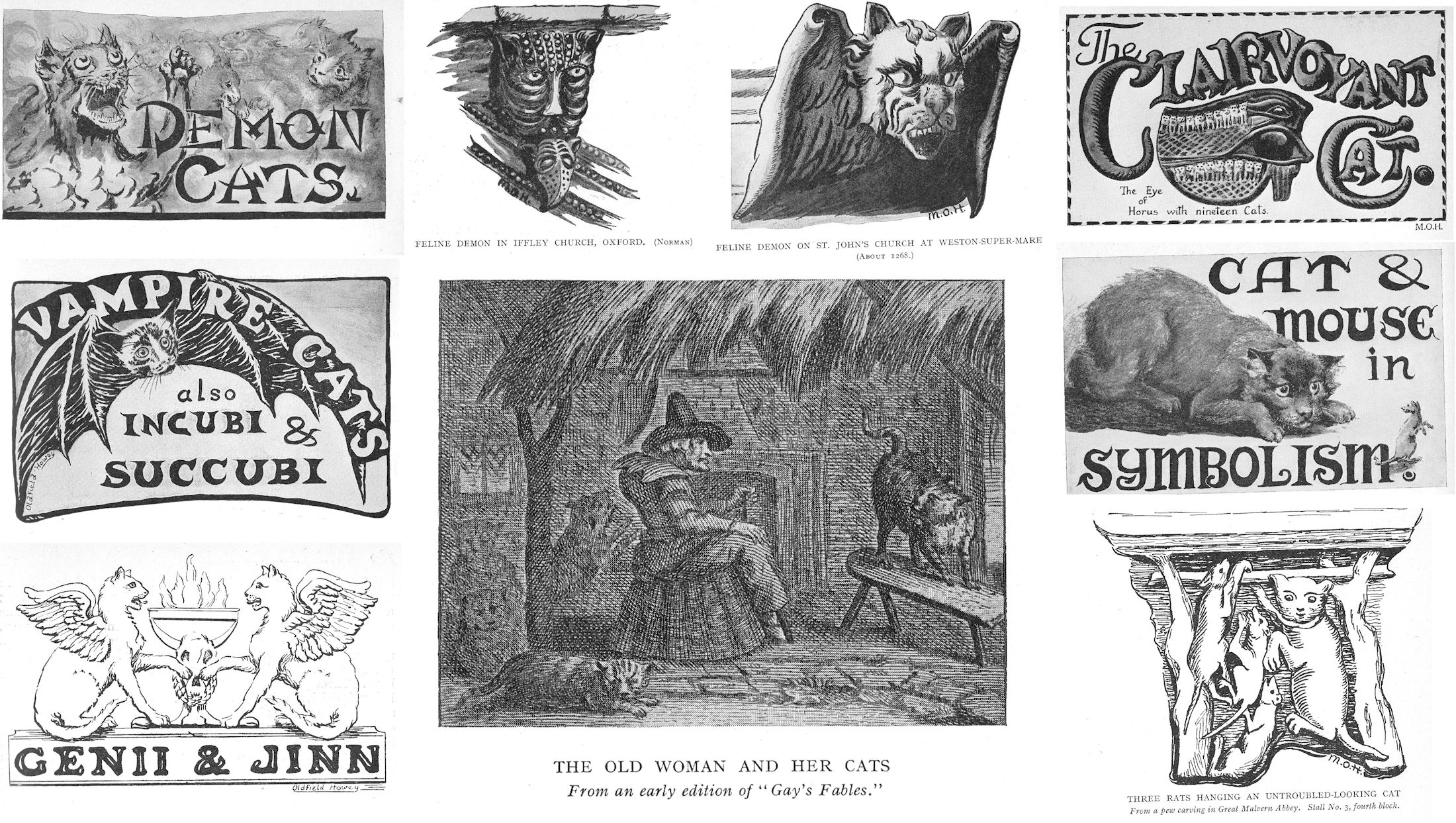

XXIII. DEMON CATS

XXIV. VAMPIRE CATS

XXV. CAT GENII AND FAMILIARS

XXVI. CAT AS OMEN OF DEATH

XXVII. CLAIRVOYANT CATS

XXVIII. CATS AND TELEPATHY

XXIX. THE CAT AS PHALLIC SYMBOL

XXX. THE CAT AS CHARM AND TALISMAN

XXXI. THE SYMBOLOGY OF CAT AND MOUSE

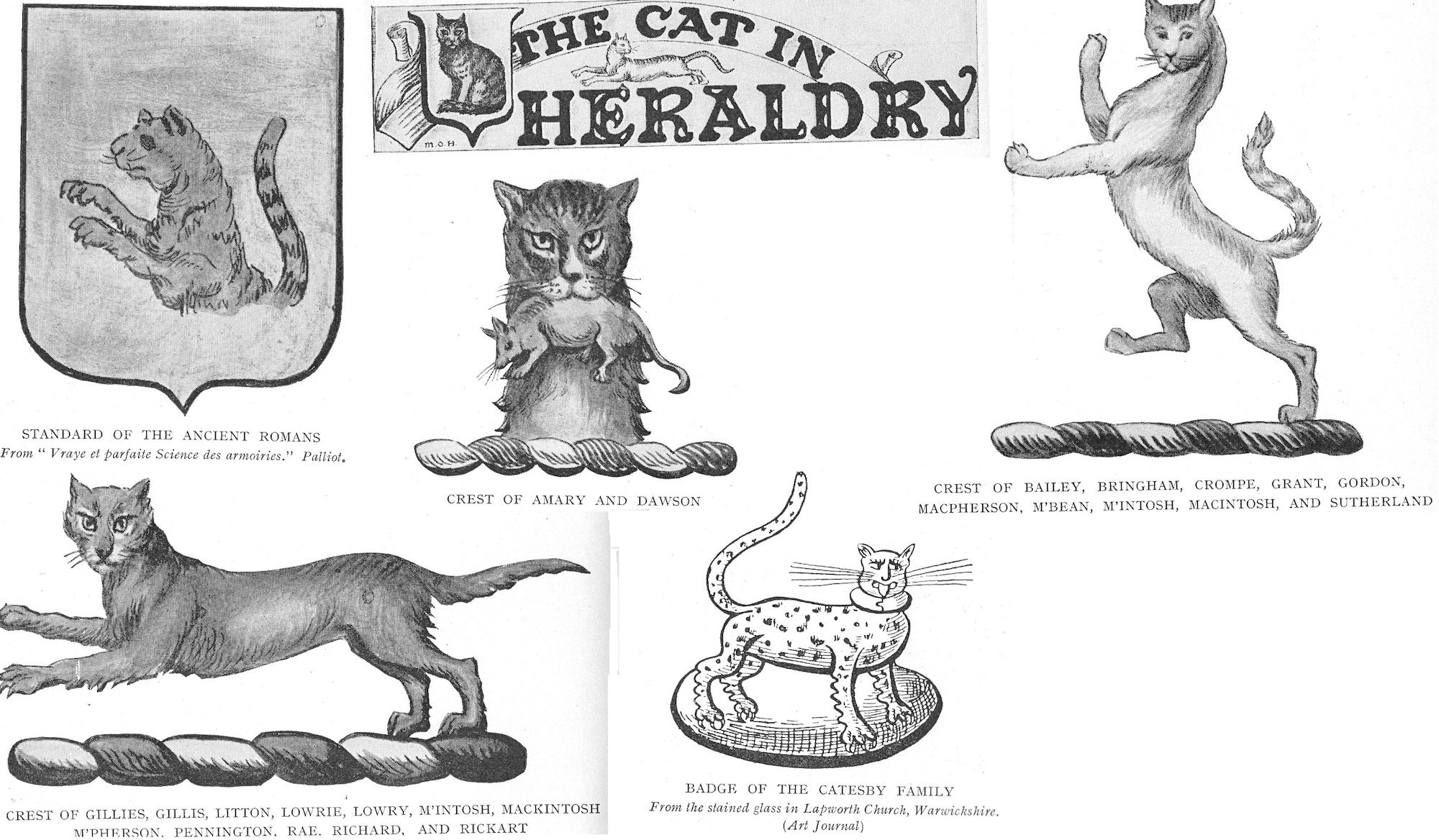

XXXII. THE CAT IN HERALDRY

XXXIII. THE CAT’S NINE LIVES

XXXIV. THE CAT’S NOMENCLATURE

XXXV. MANX LEGENDS

L’ENVOI

INDEX

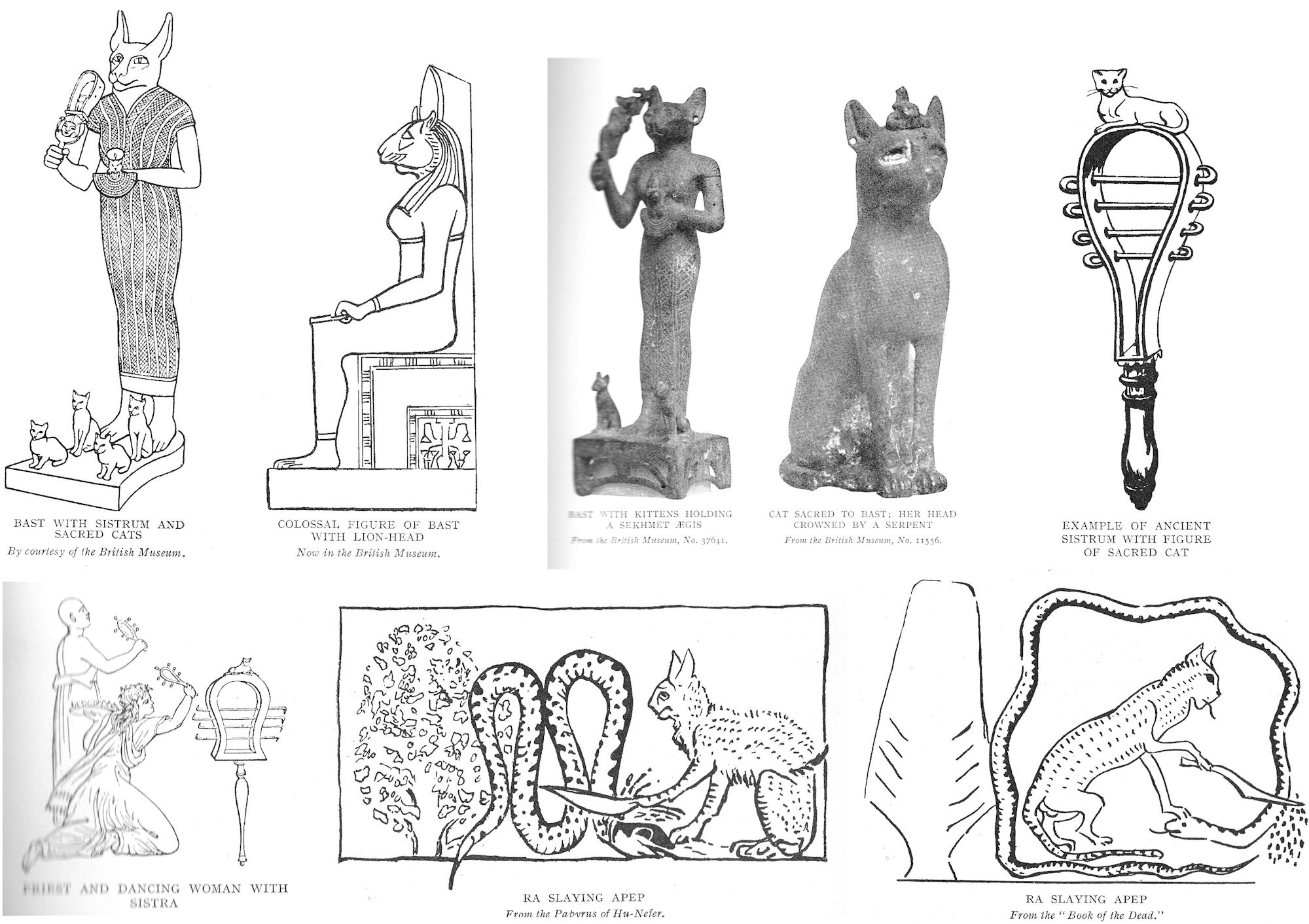

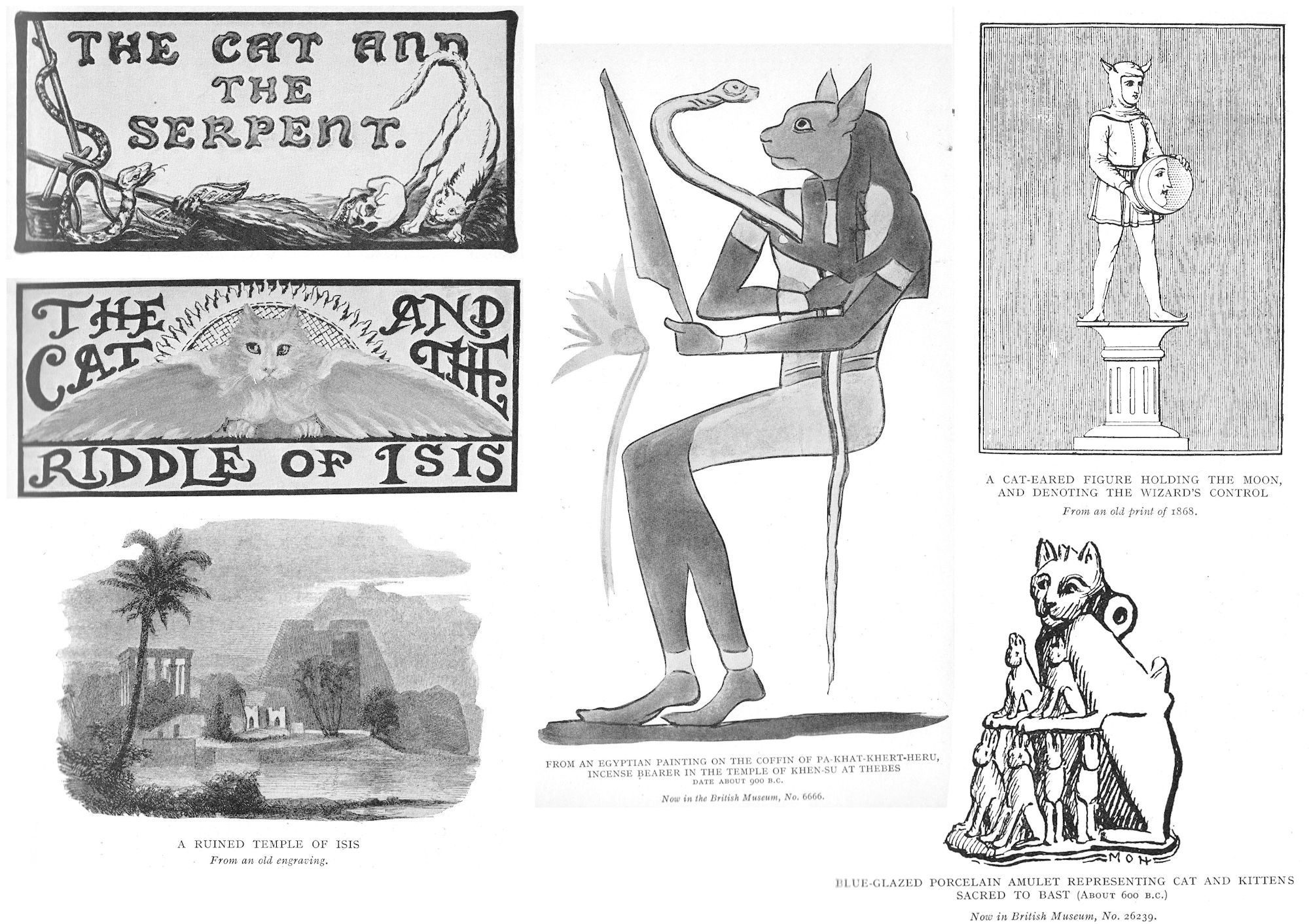

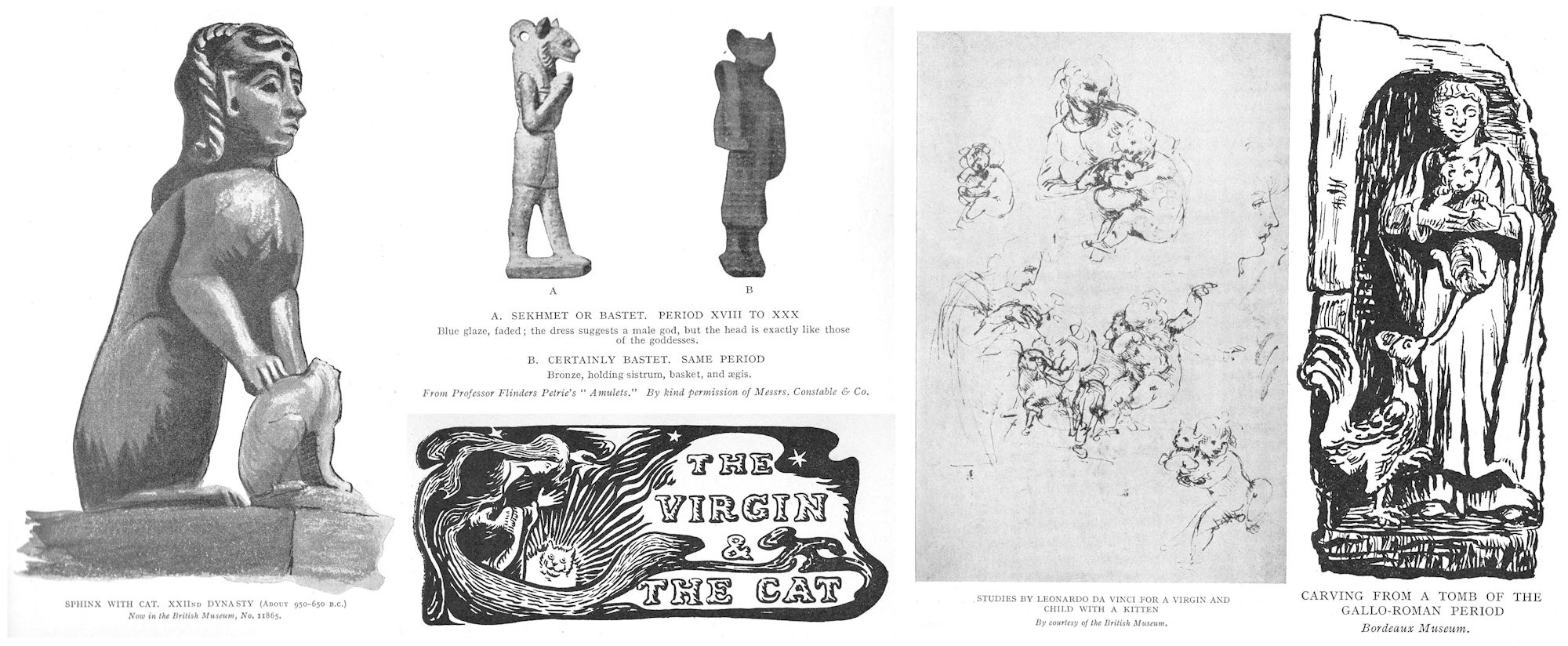

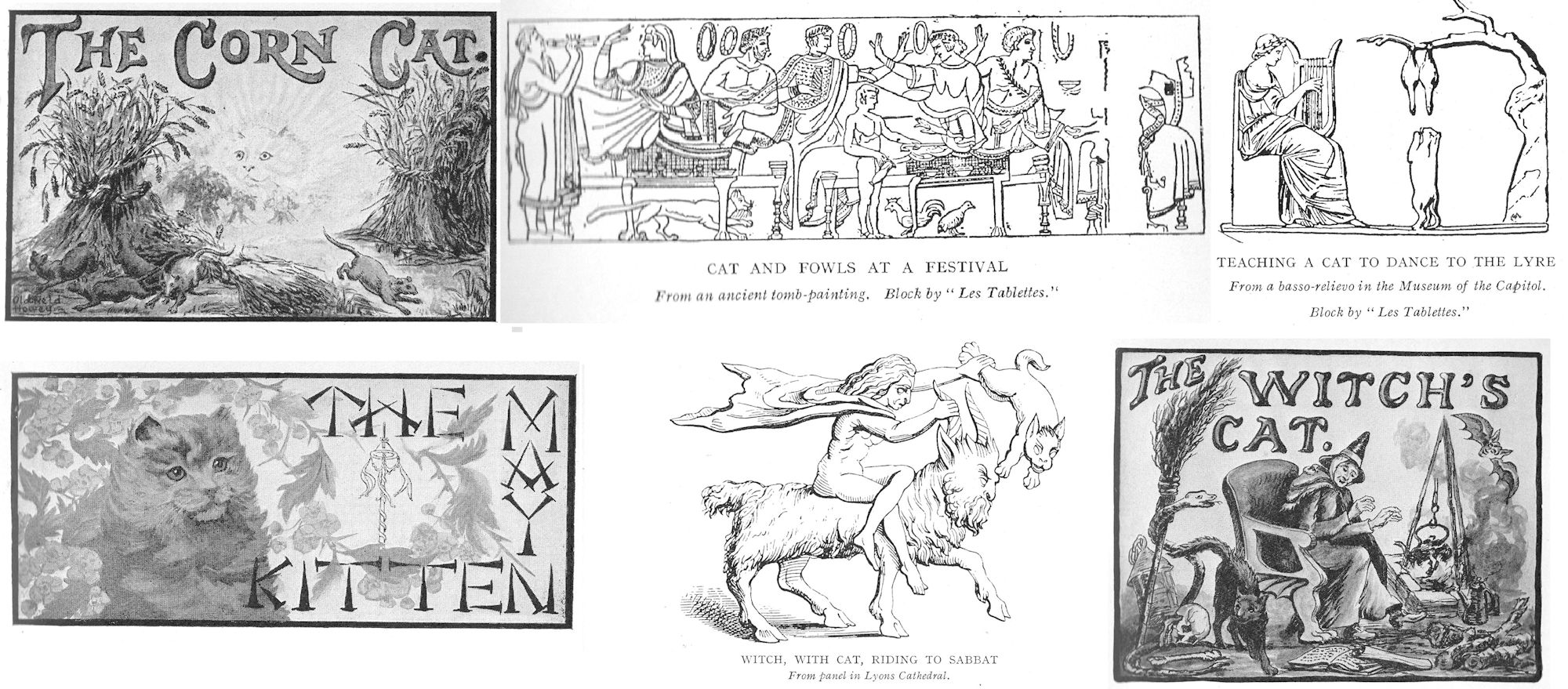

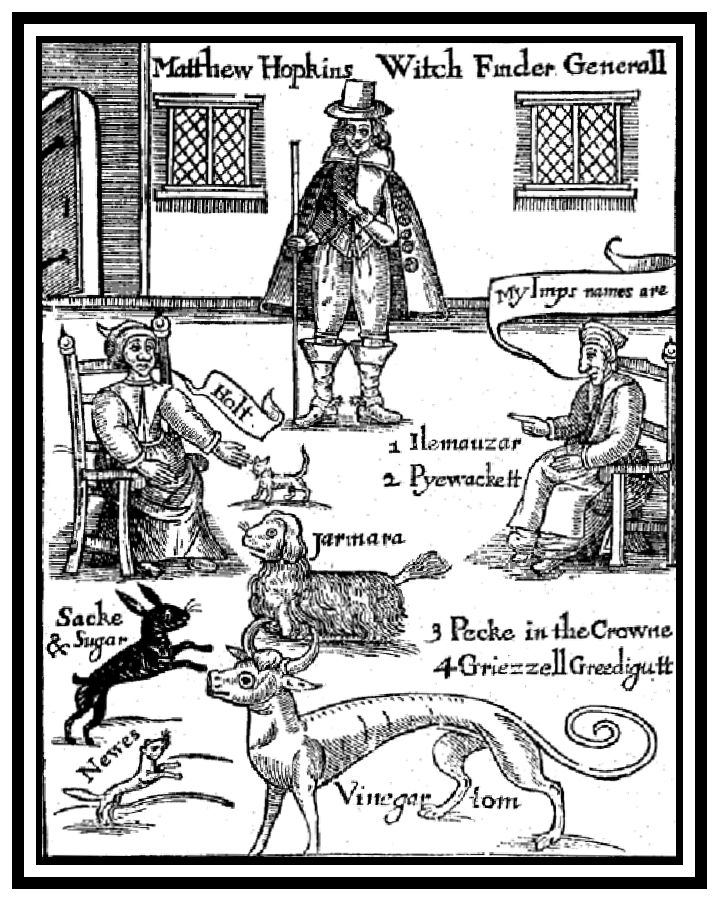

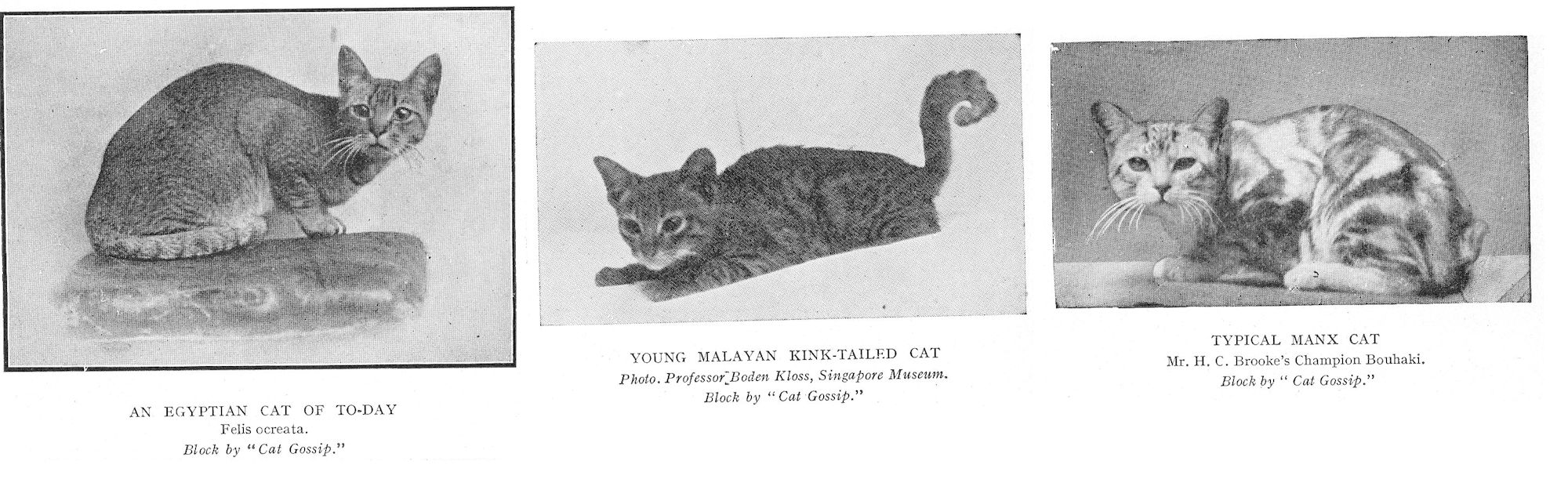

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

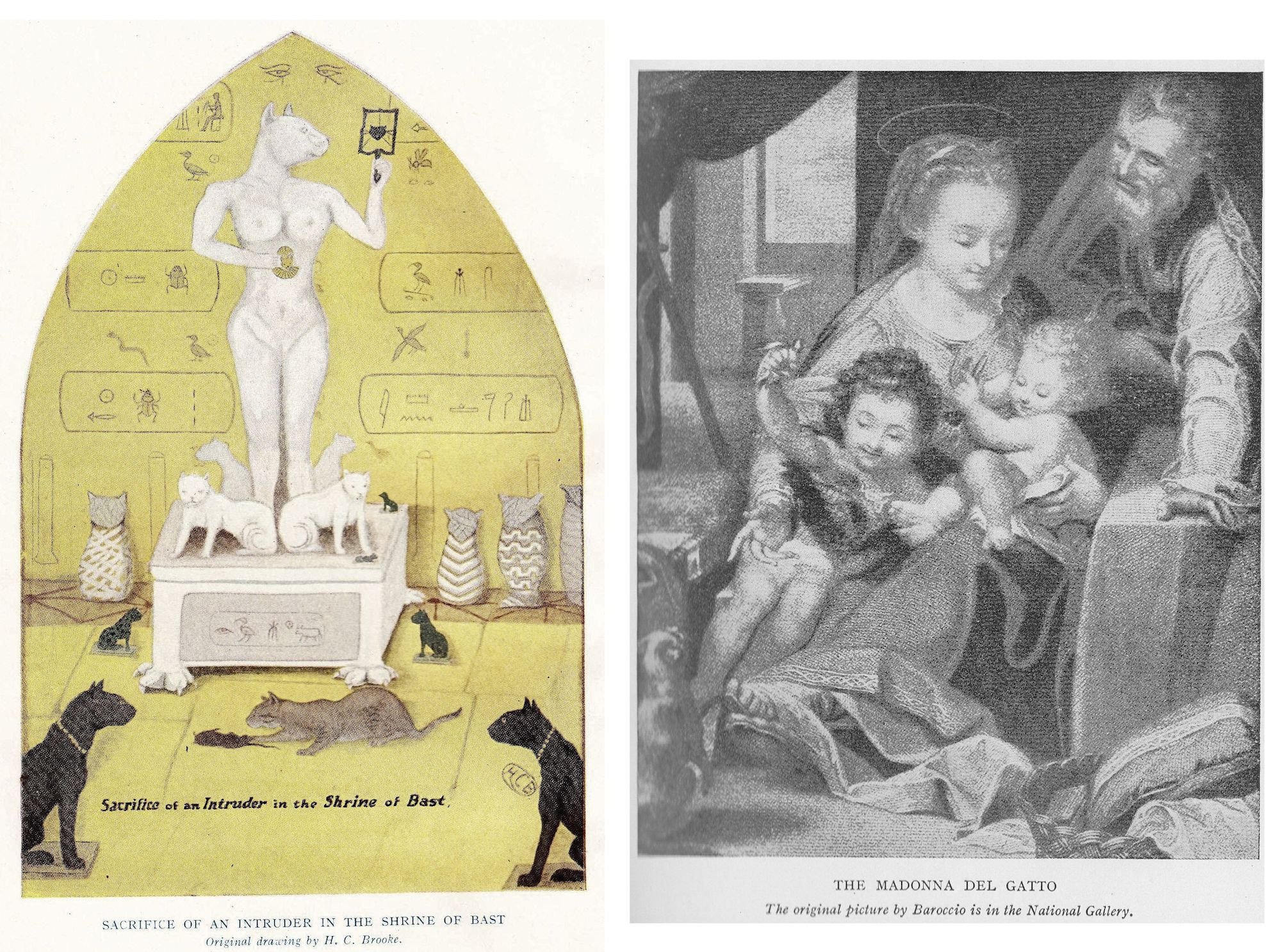

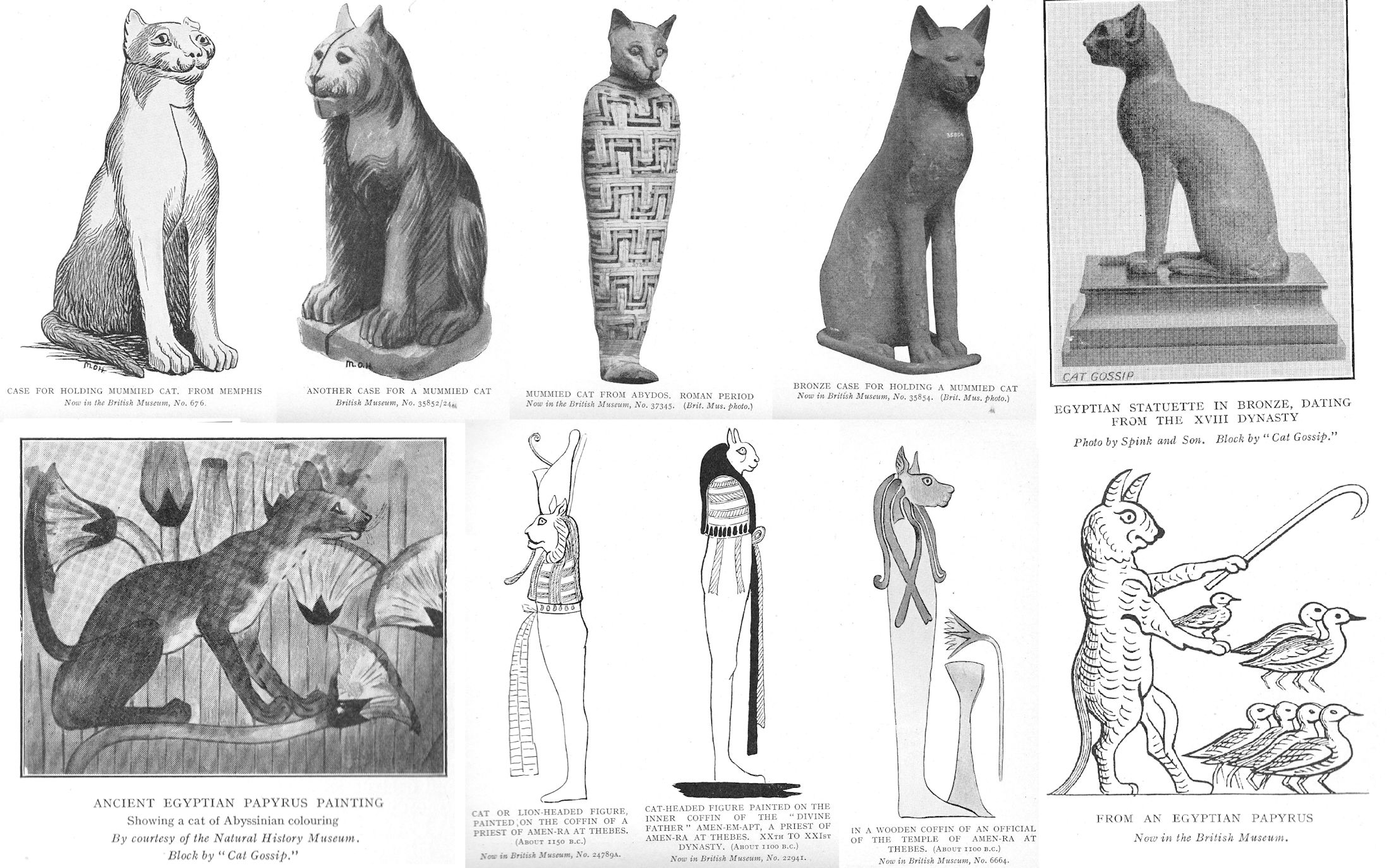

SACRIFICE OF AN INTRUDER IN THE SHRINE OF BAST - FRONTISPIECE -- BAST WITH SISTRUM AND SACRED CATS -- COLOSSAL FIGURE OF BAST WITH LION-HEAD . -- BAST WITH KITTEN HOLDING A SEKHMET AEGIS -- CAT SACRED TO BAST: HER HEAD CROWNED BY A SERPENT -- EXAMPLE OF ANCIENT SISTRUM WITH FIGURE OF SACRED CAT -- PRIEST AND DANCING WOMAN WITH SISTRA -- RA SLAYING APEP -- INCENSE BEARER IN THE TEMPLE OF KHEN-SU AT THEBES -- RA SLAYING APEP -- A CAT-EARED FIGURE HOLDING THE MOON, AND DENOTING THE -- WIZARD’S CONTROL -- A RUINED TEMPLE OF ISIS -- SPHINX WITH CAT -- SEKHMET OR BASTET -- BASTET -- BLUE-GLAZED PORCELAIN AMULET REPRESENTING CAT AND KITTENS -- SACRED TO BAST -- STUDIES BY LEONARDO DA VINCI FOR A VIRGIN AND CHILD WITH -- A KITTEN -- CARVING FROM A TOMB OF THE GALLO-ROMAN PERIOD -- THE MADONNA DEL GATTO -- WITCH, WITH CAT, RIDING TO SABBAT -- CAT REPRESENTED ON A CAPITAL IN THE FRENCH CHURCH AT -- CANTERBURY -- FELINE DEMON ON ST. JOHN’S CHURCH AT WESTON-SUPER-MARE -- FROM AN EGYPTIAN PAPYRUS -- FROM A CHOIR STALL IN BEVERLEY MINSTER -- THE SACRED BURMESE CAT -- SIAMESE CAT -- A JAPANESE “KIMONO” CAT -- A JAPANESE “ KIMONO CAT -- ANCIENT EGYPTIAN PAPYRUS PAINTING -- CASE FOR HOLDING MUMMIED CAT FROM MEMPHIS -- ANOTHER CASE FOR A MUMMIED CAT -- MUMMIED CAT FROM ABYDOS -- BRONZE CASE FOR HOLDING A MUMMIED CAT -- CAT OR LION-HEADED FIGURE, PAINTED ON THE COFFIN OF A PRIEST -- OF AMEN-RA AT THEBES -- CAT-HEADED FIGURE PAINTED ON THE INNER COFFIN OF THE “DIVINE FATHER” AMEN-EM-APT, A PRIEST OF AMEN-RA AT THEBES -- IN A WOODEN COFFIN OF AN OFFICIAL OF THE TEMPLE OF AMEN- -- RA AT THEBES -- CAT AND FOWLS AT A FESTIVAL -- TEACHING A CAT TO DANCE TO THE LYRE -- FELINE DEMON IN IFFLEY CHURCH, OXFORD -- THE OLD WOMAN AND HER CATS -- EGYPTIAN STATUETTE IN BRONZE -- CARVING ON A STALL IN ST. MARY’S MINSTER, ISLE OF THANET -- AN EGYPTIAN CAT OF TO-DAY -- YOUNG MALAYAN KINK-TAILED CAT -- THREE RATS HANGING AN UNTROUBLED-LOOKING CAT -- STANDARD OF THE ANCIENT ROMANS -- CREST OF BAILEY, BRINGHAM, CROMPE, GRANT, GORDON, MACPHERSON, M'BEAN, M’INTOSH, MACINTOSH, AND SUTHERLAND -- CREST OF AMARY AND DAWSON -- CREST OF GILLIES, GILLIS, LITTON, LOWRIE, LOWRY, M’INTOSH, MACINTOSH, M’PHERSON, PENNINGTON, RAE, RICHARD, AND RICKART -- BADGE OF THE CATESBY FAMILY -- TYPICAL MANX CAT

2018 FOREWORD

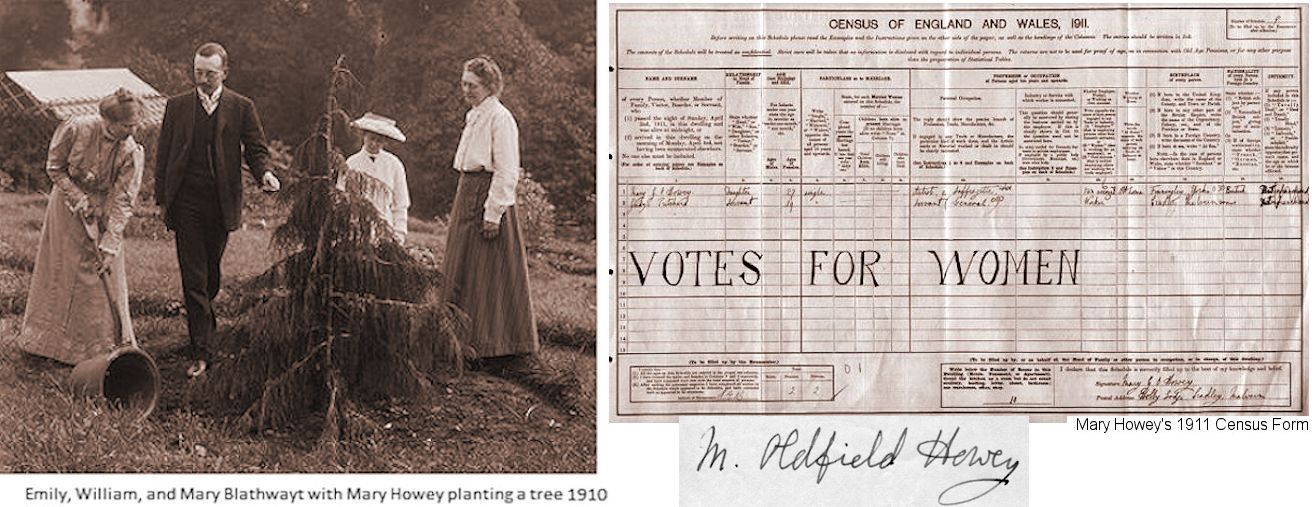

Miss (Marie) Mary Gertrude Oldfield Howey (1882-1967) Mary was the daughter of Thomas Howey (1851/2–1887), rector of Finningley, and Emily Gertrude (nee Oldfield). She became an authority on religion and occultism. Her 4 major works were The Horse in Magic and Myth (which she illustrated) 1923, The Encircled Serpent; a Study of Serpent Symbolism in all Countries and Ages 1926, The Cat in the Mysteries of Religion and Magic 1930, and The Cults of the Dog 1972 (posthumous publication).

Following her father’s, the family moved to the Malvern area. Her younger sister was the famous suffragette (Rose) Elsie Neville Howey (1884–1963). The Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 4th October 1902 reports “The results of the Government Examination of those students who studied memory and other drawing on the black board have been received follows: First class: [. . .] Mary G. Howey “

In December 1907 Elsie encountered the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and she, Mary and their mother joined the union. Both sisters embraced militant tactics and were arrested and gaoled in February 1908 when, with other suffragettes, they hid inside a pantechnicon and were “delivered” into the House of Commons. The journal “Votes for Women” of 9th July, 1909 contained this letter by Mary: ‘In the street recently a lady said to me, " What I can't understand about you Suffragettes is how you ever bring yourselves when in prison to wear that badge of shame, the broad arrow. I should feel utterly crushed by it." " But don't you know," I cried, " this so-called broad arrow is really a crown, and therefore is anything but a badge of shame. True, it is a somewhat thorny crown, but this does not dim its brightness nor our joy that we are accounted worthy so to serve our great cause."—Yours, etc., MARY HOWEY.’ Elsie seems to have been the more militant of the Howey sisters and was gaoled multiple times.

The women were also “census evaders“ (i.e. if women do not count [vote], neither shall they be counted – no vote, no census) . 27 year old WSPU member Mary Howey took part in the 1911 census boycott. On the census form she described herself as a self-employed ‘Artist and Suffragette’ while her sister and mother refused to be listed on the census form. Mary completed the form as ‘daughter’ occupying ten rooms, with one servant. She then defaced the form listing “not enfranchised” in the column for infirmity and wrote “VOTES FOR WOMEN” in large capitals on the form. The Museum of London’s Suffragette Fellowship Collection has a suffragette scrapbook made by Mary.

Like many well-educated women, Mary was an artist and we have this clipping from the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 29th January 1924: “Horses in Heaven. Lord Chaplin would have been pleased, though perhaps a little disturbed, by the exhibition opened at the Arlington Gallery this afternoon of ‘Allegorical and mystical horse pictures.’ These paintings by Miss Oldfield Howey claim to depict the afterlife of animals and show horses in heaven. The Countess of Wemyss, the Countess of Carnwath, and other society people who attended the private view seemed quite in sympathy with the belief inspiring the pictures.”

A review of “The Encircled Serpent” in The Spectator, 2nd October, 1926 read: “This is a volume of much good material on ancient and modern symbolism ; but it has not been worked over into any satisfying form, and Miss Oldfield Howey is a little indiscriminate in the writers she accepts as authorities. It is disconcerting, for example, to find a chapter upon ‘Sea Serpents,’ in which irreconcilable accounts are cited as accumulative evidence.” This is equally true of her volume on cats.

She advertised “Handsome Tabby Polydactyle Kittens” for sale in “Cat Gossip” of 26th October, 1927, priced “From 5 shillings each, or Exchange for Books on Occultism. – OLDFIELD HOWEY, Cradley, Malvern.” On 12th September 1928, “Cat Gossip” reported: “Miss Oldfield Howey, the well-known authoress (when are we to expect your promised book on ‘The cat in Religion and Myth,’ Miss Howey?) [. . .]” On 24th July, 1929 the same publication notes “Miss Oldfield Howey is again advertising her little bungalow, and is hoping that she will once more be lucky enough to let it to some realy cat lovers. She has not lost her former tenants, who are moving into an unfurnished bungalow, so that there may be quite a little colony of enthusiastic cat fanciers at Cradley in the near future. There are very few owners of furnished bungalows who do welcome cats, and this is an opportunity not to be missed by those who only enjoy their holidays when they can be shared by their pets.”

She wrote to “Cat Gossip,” on several occasions, for example this note from 22nd May 1929 “We have received a most interesting letter from Miss Oldfield Howey, who has for a long time been seeking for information concerning the origin of polydactyle cats. She has recently met a lady who tells her that they are Siberian, and were imported by the Government during the War to fight the rats in the docks, as their large, powerful feet and extra claws were supposed to give them a great advantage over the ordinary British cats, and they were said to be more sporting. The type is a very dominant one, and, once introduced, is difficult to breed out again. Miss Howey has herself proved this to be true, since without any artificial selection it has continually reproduced itself in her cats, since it first appeared in the litter of an adopted stray — not herself polydactyle. Miss Howey’s informant is the owner of a shorthair male, with eight claws on the front feet, obtained from Liverpool docks, and this cat treads heavily, not noiselessly like an English cat, and is a fine ratter. Miss Howey is still thirsting for more details about Polydactyle cats, and hopes that some reader of “Cat Gossip” may be able to tell me whether they were originally long or shorthair, and whether they have any special characteristics as well as the extra claws. Alost of the Polydactyle kittens in her cattery are born with drop ears, and retain them sometimes for weeks, though they eventually take the ordinary form.”

Mr. H. C. Brooke (an authority on cats) responded in the same issue: “The information given Miss Oldfield Howey as to their origin is erroneous. I doubt if any Government, however foolish, however desirous of squandering the taxpayers’ money, would perpetrate the absurdity of bringing cats from Siberia to a cat-infested country Even if each such cat caught daily three more rats than an ordinary cat, would the purchase be worthwhile? But even assuming, for the sake of argument, that this was done, the origin of these cats would by no means be accounted for. They exist and have existed in all countries. Thirty odd years ago I showed a Manx with all four feet bearing each four extra digits. It is a ‘freak,’ and undoubtedly reproduces itself with some pertinacity. Let us be content with that, and not strive, as has been done, to make out that it is a ‘provision of Nature,' etc., etc., to enable them to take their prey more easily. Were this the case ‘Nature’ would seem rather foolish not to thus ‘improve’ some wild felines, whose existence depends entirely on their power of ‘grabbing.' As a matter of fact, in very many Polydactyles the extra digits are practically useless.

Far more interesting is the fact mentioned by Miss Howey as to the dropped ear. Apparently another freak, which if it only persisted with age would explain to us the legend (?) of the Chinese Drop-Fared Cat, the puzzle of two centuries. No doubt many properties in various animals were originally such ‘freaks’ ; probably the first canine which dropped its ears out of the normal upright position of the canine ear, was so regarded. Polydactylism occurs in the human race, both on feet and hands, but I’ve never heard it suggested this was a provision of ‘Nature’ to enable the human being the better to do this, that, or the other. Such human polydactylism is heritable, as in the cat, but no one has found it so beneficial that they have striven to found a polydactylous strain of humans. The cat, probably owing to its extreme sensibility, seems very prone to ‘freak’ formations.”

Howey also supported the Anti-Vaccination League. On 8th September, 1942, a letter appeared in the Birmingham Daily Post “it must in fairness be recognised that there exist wide differences of opinion not only among the public but among medical men as to the value of inoculation as preventive of diphtheria. - M. Oldfield Howey. Cradley, Malvern, September 5.” At the time, cats were still suspected of spreading diphtheria to humans. There is also a Times obituary on 2nd April, 1968, which reports Miss Mary Gertrude Oldfield Howey leaving a bequest to the Anti-Vaccination League.

Later on, she appears to have been an aviatrix as indicated by this cutting from the Cheltenham Chronicle, 4th March 1950: “Aero Club Has Plan to Make Staverton Pay. THE Cheltenham Aero Club has a plan to make Staverton Aerodrome into a financial success and an asset to its joint owners, the Gloucester City and Cheltenham Borough Corporations, instead of it being a liability to the ratepayers. The plan is to set up at Staverton a fully operative training establishment. . . . there are only three lady members of the club— Miss M. Oldfield-Howey, the authority on world religions and sects [. . .].”

The Cat in the Mysteries of Religion and Magic, published in 1930, seems to have had positive reviews despite Howey’s tendency to throw everything but the kitchen sink into the book and what appears to be an attempt at a grand unifying theory of religion with Egypt at its root. For example, the Derby Daily Telegraph, 11th December 1930, calls it “a terrifying book for the cat-owner [. . .] revealing as it does what a half royal, half satanic relic of magical dignity and power we have purring the hearthrug. The cat in her long history has always been close to the supernatural. She had been a queen in Egypt for three thousand years, symbol of the sun and the moon, of life and death, a figure of magic, a goddess of fertility, a witches' imp, god and devil. She has accepted incense and human sacrifice, and still in Burmah she is a divinity with temples of her own. After reading Mr. Howey's book we cease to wonder why our hearthrug friend is independent of human affection.” And according to the Aberdeen Press and Journal of the same date: ”Truly this is a captivating study, and its value enhanced the exhaustive bibliographies given to each chapter.” (The reviewers get the author’s gender wrong as Mary used her initial rather than her first name.)

The Cat in the Mysteries of Religion and Magic suffers from the same problem as “The Encircled Serpent” in being disorganised and quoting some questionable “authorities.” It also reflects the era’s obsession with Egypt (Tutankhamen’s tomb had been opened 1922), overlooking the fact that belief systems arose independently in different regions and that many cultures independently created deities responsible for important aspects of human life – agriculture, love, death etc. Reading the book one would think that religion did not exist before dynastic Egypt and that Egyptian beliefs were the root of, or assimilated into, all later religions.

THE CAT IN THE MYSTERIES OF RELIGION AND MAGIC

CHAPTER I. BAST

At the head of the deities of ancient Egypt to whom the cat was specially sacred stood the great goddess Bast, or Ubastet—also known as Bubastis and Pasht — the second member of the Triad of Memphis, and the loved and constant companion of Ra himself. She appears to have been originally a foreign deity, but, in very early times became identified with the female counterparts of the Sun-gods, Ptah, Ra, Osiris, and Tem. We may see in her a personification of certain aspects of Isis, who, as the moon, or the Cat that represented the moon, was specially adored in the city named after Bubastis — Aboo-Pasht, the City of Pasht. Here the worship of Bast dates from a remote antiquity, and the Cat was held in such reverence as her symbol by its citizens, that deep mourning followed the death of the sacred animal.

Bubastis was situated east of the Delta, at a short distance from the Pelusiac branch of the Nile, and lofty mounds named Tel Basta still mark its site. It is referred to in Ezekiel XXX. 17, as Pi-beseth (margin, Pu-bastum), and seems to have been then a city of some importance. The prophet foretells its downfall, saying its young men shall fall by the sword, and it shall go into captivity.

It is not known where the greater number of the numerous statues of Bast now in the British Museum came from, but some were brought from Thebes, and some probably once graced the Temple of Bubastis. Many of them bear the name of Amunothph III, and it is difficult to understand why this monarch of the Theban line made so many statues in honour of a goddess who more especially belonged to Lower Egypt. Sharpe suggests it is partly explained “by the title used within the second oval of his name, where he calls himself ‘Ruler of the city of Mendes.’” However this may be, great honour was accorded to Bast in the Upper Country; and at Thebes, as at Heliopolis, she held a conspicuous position among the contemplar deities. She is mentioned in the Pyramid Texts [* Texts of the Pyramid of Pipi], but only occasionally figures in the Book of the Dead.

[2018 Note: Herodotus was prone to traveller’s tales and should be taken with a grain of salt!]

Herodotus has bequeathed to us a vivid description of the shrine of the goddess as “standing on an island completely surrounded by water except at the entrance passage. Two separate canals conduct from the Nile to the entrance, and diverging to the right and left surround the Temple.” These were about 100 feet broad and their banks were planted with trees. The remains of the once magnificent building show it to have been about 500 feet long. It was built of the finest red granite, and encompassed by a sacred enclosure about 600 feet square, beyond which was a larger enclosure, 900 by 1200 feet, containing a canal, a grove of trees, and a lake. “The vestibule,” continues Herodotus, “is sixty feet high, and is ornamented with handsome figures, six cubits in height. The temple stands in the centre of the city, and in walking round the place you look down upon it from every side, because the foundations of the houses having been elevated, and the temple still remaining on its original level, the sacred enclosure is encompassed by a wall, on which a great number of figures are sculptured, and within it is a grove, planted round the cella of the temple, with trees of a considerable height. In the cella is the statue of the goddess. The sacred enclosure is a stadium (600 feet) in length by the same in breadth. The street which corresponds with the entrance of the temple crosses the public square, goes to the east, and leads to the Temple of Mercury.”

One of the principal festivals of the Egyptians was that celebrated at Bubastis, in honour of Bast, in the months of April and May. Herodotus (II, 59, 60) considers that the Egyptians took more interest in this than in any of the numerous fetes which were annually held in their country, and he has handed down to us an account of the ceremonial observed on the pilgrimage to Bubastis. The celebrants “go by water,” he says, "and numerous boats are crowded with persons of both sexes. During the voyage omen strike the crotala; some men play the flute; the rest singing and clapping their hands. As they pass by a town they draw the boat into the bank. Some of the women still singing and playing the crotala; others calling out as long as they are able, uttering reproaches against the people of the town, who begin to dance, whilst the former pull up their clothes before them in a scoffing manner. The same performance is repeated at every town they pass upon the river. Arrived at Bast, they celebrate the festival of Diana, sacrificing a great number of victims, and on that occasion a greater consumption of wine takes place than during the whole of the year; for, according to the accounts of the people themselves, no less than 700,000 persons of both sexes are present, besides children.

Although the name Bast implies “the tearer,” or “the render,” yet, in contradistinction to the fierce Sekhmet, goddess of war, who represented the destructive powers of the solar orb, Bast typified its kindly fertilizing heat. She was considered as embodying the beneficent portion of the elemental fire, and as the bringer of good fortune. She was also known as “the lady of Sept,” i.e. of the star Sothis. Bast is a counterpart of the joyous Hathor, like her delighting in music and the dance. We may recognise her by the sistrum of the dancing women adorned with the heads or figures of cats, which she holds in her hand, and by the aegis, or by the basket supported on her arm. But occasionally she is represented without these attributes, and then it is difficult to know whether we are viewing he Cat’s head of the kindly Bast, or the lion’s head of the mighty and terrible Sekhmet. Bast herself is often represented as lion-headed, and occasionally the demonstrative sign following her name is a lion instead of a cat, though the latter was her particular emblem. Some of the black basalt figures in the British?Museum are of Bast as a lion-headed goddess, and it is probable that these are of the earliest date, since Bast only appears with the head of a cat at a later period, and then principally in small votive bronzes.

Finding wolf and jackal were both dedicated to Anubis, we may easily admit lion and cat to have been alike emblems of Sekhmet and Bast. Originally Bast seems to have been represented with the head of a lion (not of a lioness, for the mane is indicated) in allusion to the arsenothelic, or male and female nature which was hers. The Egyptians appear to have regarded these feline animals as interchangeable from the standpoint of symbology. But in the bronze figures the Cat’s head is distinct. They sometimes represent her with the sistrum in her right hand, and in her left, the head of a lion surmounted by a disk and asp; but such bronzes are of later date, and so can less be depended upon as a true mirror of the goddess’s attributes than the sculptures of the ancient monuments. Probably the lions, which AElian states were kept in the courts of the Temple of the Sun, were dedicated to Bast. It is as a lion-headed woman that Bast is represented in the colossal seated figure in sienite which is now in the British Museum (No. 57 [* Sharpe, p. 44]). It is clothed in a tight-fitting dress, the feet side by side, the hands resting on the knees, the left hand holding the ankh, the symbol of life, and the right hand open. On the sides of the seat is an inscription in honour of “the priest, the Son of the Sun, the good king of Upper Egypt, Lord of battles, Amunothph III, beloved by Pasht.” This statue is 5 feet 2 inches high from the feet to the top of the head, exclusive of the base on which it rests and the crowning solar disk.

Another colossal statue of Bast bears a cat’s head. This is six feet high, exclusive of the disk and the base. Sharpe gives its number as 517. It immortalises the name of Shishank, the earliest Egyptian king personally mentioned in the Hebrew scriptures. He reigned at Bubastis, which was the chief city in that part of Egypt where the Jews dwelt, both during the life of Moses and afterwards. But Shishank made himself master of Thebes, and was king of all Egypt. He fought against Rehoboam, king of Judah, about 956 B.C., as recorded in I Kings XIV. 25, where we are told that "he took away the treasures of the house of the Lord, and the treasures of the king’s house; he even took away all.” The Kingdom of Judah is enumerated among the conquered nations listed on the walls of the Temple of Karnak. It seems to have been as the Tearer and Render that Shishank honoured Bast.

Another aspect of Bast is symbolised in the striking exhibit in the British Museum (listed by Sharpe as No. 105), showing the forehead and ears of a colossal cat-headed goddess with a large head-dress formed by a ring of sacred asps, each crowned by a sun. This gives us an idea of the reverence in which Bast was held by her worshippers, and clearly exemplifies her dual nature, embracing both sun and moon, and all that was symbolised by them to the Egyptian mystic, especially the essential unity of the light proceeding from them both. As the Cat sees in the darkness so the Sun which journeyed into the underworld at night saw through its gloom. Bast was the representative of the Moon, because that planet was considered as the Sun-god’s eye during the hours of darkness. For as the moon reflects the light of the solar orb, so the Cat’s phosphorescent eyes were held to mirror the sun’s rays when it was otherwise invisible to man. Bast as the Cat-moon held the Sun in her eye during the night, keeping watch with the light he bestowed upon her, whilst her paws gripped, and bruised and pierced the head of his deadly enemy, the serpent of darkness. Thus she justified her title of the Tearer or Render, and proved that it was not incompatible with love.

Later Egyptian theology seems to have produced little original thought, but to have spent its powers in reconstructing and resuscitating the old. It lost its pristine purity, and conceptions which owed their origin to magic were admitted into religion, Because the gods had often been symbolised as birds, a bird-shape was given to the great gods of each nome. Bast was represented as a cat-headed hawk in this corrupted theology. Perhaps the metaphor was intended to emphasise her identity with Isis, for that goddess hovered over the dead body of OsiriS in the form of a sparrow-hawk, and caused breath to enter into his lifeless form by the fanning of her wings, so that the dead god entered upon a new existence as king of the underworld. It was whilst Isis thus restored life to her lord that she became pregnant, and, later, gave birth to the hawk-headed Horus.

The Vulture which represented Mut (the World-Mother and great female counterpart of Amen-Ra), also appears in connection with Bast where the latter is considered as a member if the Egyptian Trinity that is recognised by the composite name of Sekhmet-Bast-Ra. This figure well illustrates the extraordinarily complicated nature of the goddess, for it depicts a man-headed woman with wings springing from her arms. And the symbolism is further complicated by two vultures growing from her neck, and lions’ claws that arm her feet.

It is impossible not to recognise this deity in Diana Triformis and Tergemina, who, by virtue of her three different offices is known as Luna in the Heavens, Diana on Earth, and Hecate in Hell. Symbologists employed various means of typifying these paradoxical aspects of the Great Mother. Porphyry sees her with the triple forms of bull, and dog, and lion united. Other writers said she had the head of a horse on the right side, of a dog on the left, and of a human being in the centre. Virgil refers to:

“Threefold Hecate with her hundred names,

And three Dianas . . .”

And Claudian says:

“Behold, far off, the Goddess Hecate

In threefold shape advances.”

In her aspect as Hecate this deity seems to have been enough to terrify the bravest. According to Tooke, "They say that she was excessive tall, her Head was covered with frightful Snakes instead of Hair, and her Feet were like Serpents.” But he also points out that her name suggests the Moon’s action in darting her rays or arrows long distances and “according to the Opinion of some, she is called Triformis because the Moon hath three several Phases.”

As Bast was sometimes identified with Mut, so we find Diana occasionally coalesced with Venus. Thus Servius, in his commentary on Virgil (2. AEneid), says that the men sacrificed to Venus under the name of Luna, in women’s clothes, and the women in men’s clothes, and the Roman historian, Spartianus, has a similar allusion {Imp. Caracal).

Wilkinson has pointed out that we must admit the identity of Diana with Venus, for otherwise she could not rank among the eight great deities, but only with those of the third and even fourth order, and this is belied by the exalted character she bears in the temples of Thebes. He thinks it possible that Horus the Elder, or Aroeris, who was the brother of Osiris, and like him represented the Sun, has been confused with Horus, the son of Osiris, identified with the Grecian Apollo, whose sister was Diana. But he warns us not to push such analogies too far. The younger Horus had no sister, and Bast could not have been the sister of the elder Horus.

Herodotus, who travelled in Egypt about 450 B.C., endeavoured to point out the identity of the Egyptian and Grecian gods, but apparently found the origin of Bast even then obscure. He considered her to be the daughter of Osiris (or Bacchus) and Isis, and to be one with the Greek Diana. A rock temple dedicated to Bast, which bears the name Speos Artemidos (The Cave of Artemis, i.e. Diana), shows that this was the accepted opinion in Egypt during the Greek period; and by the Greeks at Sais and Alexandria she was sometimes called Diana and sometimes Minerva. This is the origin of the Alexandrian proverbial description of two things very unlike, by saying they bore the same amount of resemblance to one another as a cat to Minerva. The Greek myth related by Ovid, in which Diana assumes the form of a cat to escape from Typho (Met. v. 330), further confirms the conclusion arrived at by Herodotus.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Egyptian Antiquities in the British Museum,” pp. 12, 44-7. By Samuel Sharpe. Pub. by John Russell Smith, London, 1862.

"Symbolism.” By Gerald Massey.

"The Ancient Egyptians.” By Sir J. Gardner Wilkinson, D.C.L., F.R.S., F.R.G.S. Pub. by John Murray, London, 1878.

"The Secret Doctrine,” Vol. I, pp. 323, 416. By H. P. Blavatsky. Pub. by the Theosophical Publishing Company, London, 1888.

“A Handbook of Egyptian Religion.” By Adolph Erman. Trans, by R. Griffith. Pub. by Constable & Co., London, 1907.

"Among the Primitive Bakongo,” p. 160. By John H. Weeks. Pub.

by Seeley, Service & Co., Ltd., London, 1914.

“Myths of Ancient Egypt.” By Lewis Spence. Pub. by George G.

Harrap, London, 1922.

“Egyptian Mythology,” p. 150. By W. Max Muller, Ph.D. Pub. by George G. Harrap, London.

CHAPTER II. SEKHMET

THE dread Sekhmet, the cat- or lioness-headed goddess of Egypt, who personified the fierce consuming fire of the scorching sun, was the feminine counterpart of Ptah — the title by which the Sun-god Ra was known at Memphis. The temples of Ptah, Sekhmet, Bast, Hathor, Osiris, and Seker were all placed in this city, and it seems probable that this proximity was not accidental, but intended to prompt the recognition of the essential unity of all these deities.

To aid us in comprehending the nature of Sekhmet, let us glance for a moment at the multiform character of her spouse Ptah. As we do so, we realise how dear to the heart of the Egyptian mystic was the doctrine of the Encircled Serpent, or — in the terms of the metaphor we are now considering — the Coiled Cat. The Deity was All, and Unity embraced Plurality. The name Ptah is said to signify the “Opener,” because this god personified the rising sun, and threw wide the gates of day. But we find him continually fused with other divinities, and sometimes even with those whom we should normally expect to see represented as his deadly foes. As Ptah-Seker, for example, he typifies the union of the Creative Principle with chaos and darkness, and is a form of Osiris as the dead Sun-god, or Sun in the night hours. In this character he is fitly represented by the Cat who traverses the night unseen.

We also find him as a member of the trinity, Ptah-Seker-Osiris, that about the XXIInd Dynasty had become merged in Osiris. As the Master-architect and demiurge who carried out the plans of Thoth and his helpers, together with Sekhmet his spouse, Ptah shared in the attributes of the Seven Wise Ones who came forth in the form of seven hawks from the pupil of the Eye of Ra. Bat his union with Sekhmet is more usually illustrative of the axiom that “extremes meet,” for, in contrast to the creative activities of the benevolent Ptah, she represented the destructive force of solar heat, an aspect so much in evidence in Africa that it is impossible to entirely ignore it when contemplating the sun in that continent. Its rising is watched with dread and aversion by manyiy African tribes who have learned to fear the strength of its burning rays, and carefully conceal themselves when it appears.

The solar cult originated with the hierarchy at Heliopolos, and all the feline goddesses of Egypt were representative the varying degrees of the sun’s intensity, from genial warmth to burning devastation. This accounts for many apparent paradoxes in the Egyptian pantheon, and for such descriptions as that of Isis-Hathor in a Philas text: “Kindly is she as Bast, terrible is she as Sekhmet.”

In a XIIth Dynasty tale Sekhmet is referred to as the awful goddess of plagues, but this is only one of her many aspects. She must be thought of as bearing the same relation to the kindly and beneficent Bast, as Nephthys, the consort of the evil Seth, hears to her sister Isis. The antagonism is more apparent than real. Essentially the two are one. Thus we find that though formerly the name of Bast was read as Pasht, some authorities go so far as to state that they consider the true reading to be Sekhmet. A further confirmation of the identity of the two goddesses is found in the fact that in the temple of Koptos, the Theban goddess, Mut, was at one time known as Bast, and at another time as Sekhmet of Memphis. In the; sculptures various names are attached to the feline-headed goddesses, such as “Sekhmet, the great Merenptah,” or beloved of Ptah, mistress of the heaven, and “Sekhmet, the great Urhek.” Here also Sekhmet is connected with Mut, and is then styled “Mut dwelling in the abode of Ptah, mistress of Heaven, regent of Earth.”

Instances occur where Mut is represented with the head of a cat or a lion, and Wilkinson tells us we may then think of her as having assumed the attributes of Bast or of Thriphis, since her own shape was that of a vulture.

It seems fairly evident that Sekhmet and Bast must originally have been one, or at least have had a common source, and developed from a sky-goddess such as Hathor, Nut, or Neith. The name Hathor signifies “House of Horus,” and is an analogue for the. sky, wherein the Sun-god Horus made his dwelling, She was also, regarded as a Moon-goddess, and as such was often referred to as the “Eye of Ra,” which was one of the titles of Sekhmet. Hathor was said to be the mother, wife, and daughter of Ra, and to the Egyptians represented ideal womanhood. She was described as “the lady of music and mistress of song, lady of leaping and mistress of wreathing garlands,” and was a personification of the female principle.

In this aspect we recognise Bast, but when Hathor was the

instrument of the vengeance of Ra, we find her identified with the terrible Sekhmet, as Sekhmet-Hathor, slaying the human race, and wading exultantly in their blood till Ra himself had to deliver mankind from her hands by resorting to the stratagem of making her drunken, and so unable to continue the work of destruction.

The Syrian goddess Ashtoreth, known to the Egyptians as “Mistress of Horses” and “ Lady of the Chariot,” is also considered to be one of the forms of Hathor, or Sekhmet-Hathor; and her cult seems to have been introduced into Egypt during the Syrian campaign of Thothmes III. Like Bast and Sekhmet, she is depicted with the head of a lioness. She was the terrible and destructive goddess of war, and is mounted on a four-horsed chariot which she drives over the bodies of her fallen foes. A second Syrian deity, Getesh, or Gedesh, goddess of love and beauty, and the moon, was identified with the other aspect of Hathor in Egyptian thought. In her native country she was worshipped with somewhat licentious rites as a Nature goddess, and the Egyptians prayed to her for the gifts of life and health. She is regarded by some authorities as being the other aspect of Ashtoreth.

Though not lion-headed, she is represented in Egyptian art as standing upon a lion. She wears the sun and the moon on her head. Her figure is nude: in her right hand she grasps a mirror and lotus blooms, emblems of life, and in her left, two serpents, emblems of death, thus declaring the Gnostic and Manichaean doctrine of Antitheses.

At a later period we find her still more definitely identified with Hathor, and wearing the headdress of that goddess. In an inscription of the XVIIIth and XlXth Dynasties she is similarly described as “Lady of Heaven, mistress of all the gods, Eye of Ra, who has none like unto her.”

This personification of the attributes of a single goddess in so many separate forms is confusing to a modern mind, but we must ever remember, as an old poet observed, that

"Pluto, Proserpine, Ceres, Venus, Cupid,

Triton, Nereus, Tethys, and Neptune,

Hermes, Vulcan, Pan, Jupiter, Juno,

Diana, and Apollo, are ONE GOD.”

[2018 Note: the above verse was an attempt to reconcile polytheism with monotheism!]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Celtic Researches,” p. 297. By John Davies. Pub. about 1630.

“Egyptian Mythology,” 2nd edition, p. 63. By Samuel Sharpe. Pub. by Carter & Co., London, 1896. R

“Religion of the Ancient Egyptians.” By A. Wiedemann. Pub. London,1897.

“Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt,” p. 147. By Lewis Spence, Pub. by George G. Harrap & Co., London, 1922.

“The Book of the Dead.” Trans, by Sir E. A. Wallis Budge; M.A., D.L., L.D. Pub. by Kegan Paul, Trench & Triibner, London, 1923.

CHAPTER III. THE SISTRUM

THE mystical musical instrument known as the Sistrum is of great interest and importance from a symbolical standpoint. Upon its, apis the Sacred Cat is enthroned, as emblem of the moon, and the great goddess that planet represented. Perhaps no other instrument of music has been so generally associated with magic and religious ritual as has the ancient sistrum. But the Egyptians seem to have more especially dedicated it to Hathor (or Athor), the Egyptian Venus. This goddess was in in reality but a popular personification of Isis in the role of the loving, protecting Mother of the living, and Guardian of this souls of the departed during their sojourn in the dreary Underworld. She is regularly identified with Isis in the inscriptions of the great Temple of Hathor at Denderah, although a smaller temple specially dedicated to Isis is within the same enclosure. Nowhere else do we find such prominence given to the sacred Sistrum as in this sanctuary of Hathor, so it is evident that it possessed a special significance in relation to this goddess; nor is it hard to guess what that may have been, since the Cat typifies and exemplifies the ideal Mother.

It has been suggested that the form of the Sistrum was derived from that of the Ankh, the well-known symbol of life carried by every Egyptian deity. Or, conversely, that the Ankh was based on the Sistrum. The fruitfulness of the Cat accords with either theory. The erect oval is emblematic of the Female Principle of Nature regarded as the womb of Divine Manifestation, whilst the upright pillar of the handle symbolises the corresponding Male Principle. The Cat is the presiding Deity blessing the mystic union with fecundity and abundance.

We may compare this with the description and interpretation of the Sistrum bequeathed to us by Plutarch. He describes it as being “rounded above,” and adds that “the loop holds the four bars which are shaken. Upon the bend of the Sistrum they often set the head of a cat with a human face; below the four little bars, on one side is the face of Isis, on the other side that of Nephthys.”

The Sistrum is the symbol of the world's harmony. The heads of Isis and Nephthys which adorn its handle signify birth and death. The shaking of the four bars within the circular apis represents the agitation of the four elements within the compass of the globe, by which all things are continually destroyed and reproduced, and further figures that all creatures must move in a fixed order as does the moon, whose orbit embraces all that is on earth.

To emphasise the lunar symbolism, the Cat is often represented with a crescent upon its head, but Plutarch would have us make no mistake. He points out that the Cat, from “its variety of colour, its activity in the night, and the peculiar circumstances attending its fecundicity” is the proper emblem of the moon.

In reference to this last matter, the Egyptians stated that the Cat brought forth at birth, first one, then two, afterwards three kittens, and so on, adding one at each later birth until she reached seven. So that she brought forth twenty-eight young altogether, corresponding to the several degrees of light which appear during the moon's revolutions. And Plutarch, who records this, comments that “Though such things may appear to carry an air of fiction with them, yet it may be depended upon, that the pupils of her eyes seem to fill up and to grow larger upon the full of the moon, and to decrease again, and diminish in their brightness on its waning.”

When in use the Sistrum was held in the right hand (as illustration) and shaken, from which circumstance its name is derived (aera repulsa manu. Tibullus, I. 3, 24). Its most usual form is seen in the second drawing. It was really a kind of rattle, and generally consisted of a metal frame pierced by four brass or iron rods, which were either loose, or fitted with loose rings. Apuleius describes it as a bronze rattle, consisting of a narrow plate curved like a sword-belt through which rods were passed, that emitted a loud shrill sound. He seems to suggest that the shakes were in trios, thus making a sort of rude music. He says that the sistrums were sometimes of silver, or even of gold.

The, Sistrum is said to have been also used in Egypt as a

military instrument for collecting the troops (Virgil, AEneid VIII, 696), but this does not imply a secularisation of it, as the Egyptians lived their religion and introduced it into every action. In this case it would probably be considered as an implement of Hathor or Isis in her warrior aspect personified by the terrible Sekhmet, for, like the Serpent, the Cat is a constant reminder that extremes meet, and that All is embraced by One. The Goddess inspires or destroys according to the angle from which she is contemplated. Mistress of the Heaven and Regent of the West, in her celestial character - she is the Eye of Ra, the Sun, and the solar deities Shu and Tefnut are her children; but her terrestrial presentation may be that of the goddess of youth, and pleasure, and beauty; like the Greek Aphrodite, the goddess of love, or may show us the cruel and destructive Sekhmet, whose counterpart was Bellona, goddess of war.

Sistra do not seem to have been entirely confined to Egypt. They were used in the Circle Dance of the Sebasian Mysteries, rigin of which is lost in the mists of antiquity, though

they are thought to have been derived from the Mithraic Mysteries. The dance symbolised the motion of the Planets around the Sun. The Sistrum is said to be used to-day in Abyssinia and Nubia.

The introduction of the worship of Isis into Italy shortly before the commencement of the Christian era made the Romans familiar with this instrument, and in two paintings found at Portici (at the foot of Vesuvius), a priest of Isis and a kneeling woman are represented as rattling it.

An analogous musical instrument used by the singing-girls of Japan is known as the Samisen, and its strings are made from cat-gut. Not so very long ago the geishas of Tokio subscribed for a Mass for the souls of the Cats whose lives had been brought to an untimely end in order to provide the material which was an integral part of the Instrument. Such honour and recognition suggests that the connection of the Cat with the music of the geishas is not entirely a fortuitious one, but possibly owes its origin to the same conception as that which placed the Cat on the Sistrum of Isis.?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Metamorphesos, sive de Asino Aureo,” XI, 4. By Apuleius Saturninus. . *

“Metamorphoses.” IX, 784. By Publius Ovidius Naso.

“Isis and Osiris.” By Plutarch.

“Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians.” By Sir Gardner Wilkinson, F.R.S., M.R.S.L., etc. Pub. by John Murray, London, 1842.

“The Secret Doctrine,” Vol. II, pp. 437, 483. By H. P. Blavatsky. Pub. by the Theosophical Publishing House, London, 1893.

CHAPTER IV THE CAT AND THE SERPENT

THE Cat and the Serpent must be numbered among the most ancient glyphs of Egypt, and, in its original form, seems to have been identical with the symbol of the Virgin and the Dragon. Because the Cat is the emblem of the time honoured ideal of Virgin-Motherhood, the Egyptian Great Mother Goddess, variously invoked as Isis, or Atet, or Mout, etc., as time and place might decree, was constantly represented as assuming feline form. Atet is said to have taken this shape when she conquered and slew the serpent of evil, and the myth gave rise to the Egyptian belief that cats possessed the power to heal those bitten by asps or other venomous creatures.

Like the other Great Mother Goddesses, Atet seems to have been eventually absorbed in the Great Mother Mout, “queen of the gods,” who wears the double crown of Egypt. Her symbol was the lioness, and this animal was probably chosen that it might indicate her sovereignty over all other deities; since it is the head of the family to which the Cat — representative of so many deities — belongs.

The individuality of Atet having been obliterated by a greater [one] than herself, her feat of slaying the serpent was attributed by later mythology to Ra, who personified the life-giving properties of the solar orb. It is certainly remarkable that Ra, like his predecessor, assumed the form of a cat in order to combat the evil power. The battlefield was in the Other World, for serpents were not only the foes of the living, but had to be counted among the enemies of the dead. The most formidable of these ghostly serpent antagonists was the monstrous Rerek, who had his abode in the deepest gloom of the Other World, and ever opposed the passage of Ra, and the host of glorious beings who accompanied him into the Kingdom of Day. Rerek had many forms, and was known by many names, but of all his metamorphoses the most terrible was when he appeared as Apap. He was immortal, so although Ra daily clove his head in twain, and his bones were crushed, and his body dismembered, and many other punishments inflicted on him by the gods, he always returned to life, and continued his evil doings.

During a solar eclipse a terrific battle would take place — a titanic combat between darkness and light, evil and good. Fearful of the issue, mankind breathlessly watched the peril of the Sun-god, shouting, and shaking the Sistrum to terrify the serpent foe. Suddenly the Celestial Cat would leap upon the deadly reptile with fiery eyes and bristling, coat, and Apap would fly, bleeding and torn, to the depths of darkness. After the eclipse was thus ended, the veneration of the Egyptian people for the sacred animal was always intensified. At other times priestly interference might save the slayer of a cat from popular vengeance, but after an eclipse even the power of the priesthood could not rescue the guilty person, however high a position he might hold. The Sicilian historian, Diodorus, who travelled in Egypt during the first century B.C., recorded how a Roman soldier, stationed at Alexandria, slew a cat, and in consequence was seized and executed by the mob, notwithstanding his privileges as a Roman citizen, and the entreaties of King Ptolemy who feared the vengeance of Rome.

This incident is commented on in the following striking poem to a cat:

TEMPORA MUTANTUR

When Nile was young; when Britain's savage hordes

Woad-stained, lurked beastlike in their woods and caves,

Whilst daily battling with the wolf and bear,

And mighty Urus: then, wast Thou divine!

'Fore Thee a priesthood, wise in ancient lore

Spread offerings rich and rare, and humbly bowed,

Whilst Temple girls paced in the votive dance,

With Utchat-Amulet of gold adorned,

Thou didst recline on Pharaoh's golden throne;

And when Thy time upon this earth was o’er

— And mighty Pharaoh, too, must pass away,

Ptah-Seker-Asar* having called ye hence —

Then cunning workmen wrapped Thy slender form

In choicest swaddling-cloths, with spices rare,

And, jewel-decked, Thou shareds’t the Pharaoh's tomb.

. . . . . . Egypt fell

On evil days: the Roman Eagles waved

Their threatening pinions o’er Nile’s yellow sand —

’Gainst Thee the Roman raised an impious hand —

Not yet, not yet, was Egypt’s spirit dead!

“The Roman slew a cat!” — Athirst for blood —

Forgotten dread of Rome — the swarthy mob

Poured, howling vengeance, from each alley-way —

And the proud Roman knew the taste of death —

For he had slain a Cat! . . . Far, far away

Are now those Pagan days! O’er all our heads

Civilisation’s blessings freely pour;

O; Bast, look downward through the centuries,

And see Thy children! Timorous through the streets

Some crouch, the sport of every ruffian lad;

Cold-blooded torturers wrench their tender limbs

In name of Science: others meet their end

Choking and struggling in the deadly gas,

Whilst white-clad savants, smiling, book their throes,

And khaki soldiers, shuddering’, stand aghast –

Yet scarce a soul lifts a protesting voice!

WE ARE NOT PAGANS, AS THOSE SONS OF NILE!

LET US GIVE THANKS WE ARE NOT SUCH AS THEY!

(H. C. Brooke: “Lines to an Abyssinian Cat,” 1925.)

[*Ptah-Seker-Asar - The triune god of the resurrection]

To return to our subject of the combat between the Cat of the Sun and the Serpent of Darkness; we find it vividly described in the following lines, translated by Dr. Budge, from the papyrus of Nubseni (British Mus., No. 9900, sheet 14,1,16 ff.). Ra himself is speaking, and he says, “I am the Cat which fought (?) hard by the Persea tree (19) in Anni (Heliopolis), on the night when the foes of Neb-er-tcher were destroyed.”

As the exact phrasing of the original of the sentence is admittedly somewhat obscure, I add a slightly different interpretation of the same lines by another authority, Samuel Birch. This version reads: “I am the Great Cat at the pool of the Persea, there in Heliopolis; the night of the battle made by the binders of the wicked, the day of strangling the enemies of the entire lord.”

The vignette from the seventeenth chapter of the Ritual here reproduced, represents the Sun-god (variously known as the

Great Mau, Ra, or Shu), in the form of a cat, slaying Apap (Apep, or Aphohis), the serpent of darkness. According to Karl Blind the Ritual was already ancient when, in the XIIth Dynasty, about 2500 B.C., or earlier, the gloss was added explaining that the Cat was the Sun-god himself who had adopted that form as his symbol.

Dr. Budge says that “the male cat is Ra,” and “he is called

‘Mau’ by reason of the speech of the god Sa, [who said] concerning him: ‘He is like [mau] unto that which he hath made’; thus his name became ‘Mau’;* or [as others say] it is the god Shu** who maketh over the possessions of Seb to Osiris.”

[* This is a very ancient pun on the words mau “cat” and mau “like.” Possibly also, as Renouf suggests: “ The cat, in Egyptian Mau, became the symbol of the Sun-god or Day, because the word Mau also means ‘light’.”

[** Ra, the father of the Gods, is said to have first created Shu, or Shoo, the wind-god, as a personification of himself. In this role he is “often represented in the Egyptian monuments seated and holding a cross, symbol of the four quarters, or the Elements, attached to a circle.” (Blavatsky.)

Tefnut, the consort of Shu, like Mut, had the head of a lioness. She was named “The Spitter,” because she sent the rain. Her title suggests another connection between the cat and the serpent, for it has often been remarked that the “spit” of the cat so perfectly imitates the hiss of the serpent as to suggest that it is protective mimicry.]

Chapter XXXIII of “The Book of the Dead” is directed against Apap, here called Rerek, who was rendered powerless to harm the deceased if the latter pronounced the names of Seb and Shu. The deceased orders Rerek to stand, promising to give him to eat the rat, the abomination of Ra, and the bones of the “filthy cat.” “ Hail, thou serpent Rerek, advance not hither. Behold Seb and Shu. Stand still now, and thou shalt eat the rat which is an abominable thing unto Ra, and thou shalt crunch the bones of the filthy cat.” Since the Cat is the emblem of Ra, and in that role is the Slayer of the serpent of darkness, it is difficult to explain the meaning of the text, unless we assume that the dead man hoped to disarm by flattery a foe against whom force could not prevail. Not only does he promise that the serpent shall devour the Sun Cat, but that it shall eat the rat on which the Cat feeds. The darkness shall swallow alike the Sun, and the grey clouds that are its prey [See Chapter on the Cat and Mouse.]

But possibly a more convincing explanation is that we are here up against one of those apparent paradoxes that are so numerous in Egyptian mythology. We must remember that the serpent not only represented evil and darkness slain by the Divine Cat of the Sun, but was also actually the symbol of the Sun-god himself, especially when the solar orb was personified as Ra-Tem, the setting sun entering the underworld of darkness; whilst the Cat, when considered as the representative of Sekhmet, the spouse of Ra, was the personification of destruction and chaos [see chapter on Sekhmet].*Read has pointed out that some passages in the Book of Amduat (or, the “Book of that which is in the Under-world”) seem to suggest that those who had not rendered due homage to Ra on earth shared after death in the punishment he inflicted upon Apep; and it would appear that the later Egyptians, at any rate, so understood the texts, for when they embraced Christianity their conceptions of Amenti were clearly transferred to the Hades of their new faith. In proof of this Sir Ernest Budge quotes as follows from the Gnostic work, Pistis Sophia (“Gods of the Egyptians”), Vol. I, p. 266:

“‘Jesus tells the Virgin Mary: The outer darkness is a great serpent, the tail of which is in its mouth, and it is outside the whole world, and surroundeth the whole world; in it there are many places of punishment, and it containeth twelve halls wherein severe punishment is inflicted. In each hall is a governor but the face of each governor differeth from that of his neighbour. . . . The governor of the second hall hath as his true face the face of a cat, and they call him in his place Kharakhar. . . . And in the eleventh hall there are many governors, and there are seven heads, each of them having as its true face the face of a cat; and the greatest of them, who is over them, they call in his place Rokhar. . . . These twelve governors are in the serpent of outer darkness, and each of them hath a name according to the hour, and each of them changeth his face according to the hour.’”

In the above quotation we find cat-faced governors in charge of certain of the halls of punishment said to be within the body of the world-encircling serpent of darkness. Cat and serpent are working in harmony to execute the vengeance of Ra.

These paradoxes of imagery were not accidental, or the result of confusion of thought as might appear to a casual reader, but are a constant feature in occult symbolism, and had a deep purpose. By thus portraying extremes in unity, the priestly initiator prepared the mind of the understanding aspirant for the reception of spiritual truths and mysteries otherwise unutterable. When we endeavour to interpret such sacred and ancient symbols it is essential that we take into account the context and environment in which they are found, and the fact that they almost invariably bear an esoteric as well as an exoteric significance.

For the purpose of comparison, we would ask our readers to recall the Norse myth, which relates how the God Thor was fooled by the giant’s king, Utgard-Loki, during that deity’s visit to Jotunheim. Thor was challenged to lift from the ground the cat that was the playfellow of the giant’s children, but in spite of all his efforts was only able to raise one of its paws. Afterwards Utgard-Loki explained his failure by telling him that the seeming cat was in reality the Midgard serpent that encompasseth the earth. The Cat and the Serpent are merely two forms of the same allegory, both symbolically portraying the truth that God is All. Each alone represents the apparently dual and warring forces of Good and Evil.

Throughout mythology the idea underlying the symbol of the Coiled Cat (or Encircled Serpent) is emphasised and insisted upon. Of good beings, evil entities are born, and of evil good. From the beautiful the hideous comes forth, from the hideous the beautiful.

All natural phenomena confirm, and possibly gave rise to the allegory. Night is born of day, day of night, light of darkness, darkness of light, cold of heat, and heat of cold, life of death, and death of life, The cat in repose forms a circle, even as the serpent's head finds and bites its tail again. Thus it is the ideograph of Divinity in Nature, the Eternal, the Universal, the Complete. It is Om, the sacred Name, the prayer that exceeds all prayer and obviates words in realisation.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“Archseologia: or Miscellaneous Tracts relating to Antiquity,” Vol. VIII, pp. 174,176. Pub. by the Society of Antiquaries of London, 1787.

“On the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illustrated by the Religion of Ancient Egypt,” p. 237. By Peter le Page Renouf. Pub. about 1860.

“The Contemporary Review,” Article by Karl Blind, October, 1881.

“The Secret Doctrine,” Vol. II, p. 545. By H. P. Blavatsky. Pub. by the Theosophical Publishing Company, London, 1888,

“Egyptian Myth and Legend.” By Donald A. Mackenzie. Gresham Publishing Company, London, 1913.

“The Book of the Dead,” 2nd edition. An English translation of the “Theban Recension.” By Sir E. A. Wallis Budge, M.A., Litt.D, Pub, by Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., London, 1923.

“Egyptian Religion and Ethics,” pp. 139-41. By F. W. Read. Pub. by .Watts & Co., London, 1925.

CHAPTER V. THE CAT AND THE RIDDLE OF ISIS

TO fully comprehend the tremendous powers which were anciently attributed to witches we must continually remember that they were originally the priestesses and votaries of the Moon-goddess Isis, Diana, or Luna, the Queen of Heaven, and Great Mother of all life. As such they claimed, and were credited with, power to wield the forces supposed to emanate from the planet over which their deity presided. These were numerous and far-reaching in their effects. The ancient alchemists taught that the human body was a microcosm, in which the heart represented the sun, and the moon the brain. Consequently the lunar orb was regarded as responsible for mental derangement, which belief is yet perpetuated in such words as lunacy and lunatic. Endless instances are recorded by physicians of all periods to prove that the insane become more violent when the moon is at the full. But the brain was not the only human organ to be affected by lunar changes. The very marrow of men's bones, and the weight of their bodies were said to suffer increase or diminution in sympathy with its modifications. In fact, hardly anything escaped the subtle influence of our satellite. The circulation of sap in trees, the quality of the vintage or the harvest corn were alike placed to its account. Therefore timber had to be felled, the juice of the grape expressed, and the harvest gathered, when the appearance of the moon indicated that the right time had arrived. Otherwise failure would follow. The influence of lunar motion upon the tides, was observed long before it was explained, and gave countenance to the idea that the moon was responsible for weather conditions. It would be easy to fill a volume with accounts of the planet's supposed powers, so many directions were they believed to extend in. And all these varied potentialities were held to be within the control of witches and wizards, the degenerate and wicked survivors of Luna's once great hierarchy.

Shakespeare refers to this conception in “The Tempest”:

"A witch; and one so strong

She could control the moon — make flows and ebbs,

And deal in her command* without her power."

[*Or “with all her power.” (See Corrector of folio of 1632.)]

That such occult forces might actually be seized upon, and controlled by human beings was a belief as widespread as it was ancient, and the student of religion will have no difficulty in tracing it to its source. Water is everywhere the symbol of the motherhood of God. Whether this be personified as Venus, or as Mary, the essential characteristics are the same. The Mother of the God of Love is the queen of the sea, and the patroness of sailors. Her colour is the ocean blue. The Power of God moves upon her waters, and is reflected therein, causing material phenomena to be manifested. Mary, or Mariah, in the Hebrew means “mirror.” The name of Buddha's mother, Maya or illusion, conveys the same idea of unsubstantiality, and is perfectly symbolised by the seemingly actual forms imaged in the bosom of deep water which are not only unreal, but inverted. Many of her examples might be given, but these will suffice. The sacred element was believed to be obedient to the priests and priestesses who served the goddess personifying both water and the moon that controlled its tides.

We have seen in other chapters how closely ancient peoples connected the Cat with the moon. So we shall not be surprised to find that witches specially favoured the feline form when they sought to raise a storm, and that sailors saw a disguised witch in every unknown cat. This is why the light breeze that ripples the water during a calm, and indicates a coming squall, is known to seamen as a Cat’s Paw; and a frolicking cat is believed to foretell a gale, if not to be actually making one. It is common knowledge in Scotland that a cat scratching table or chair-legs is “raising wind,” and the Rev. James Macdonald relates how he once “heard a Scotch matron order her daughter to 'drive out that beast: do ye no see she’s making wind, and we’ll no get a wisp o’hay hame the day gin she goes on.’”

In many languages the word cat is found with a nautical meaning attached to it. In English we have cat-block, cat-boat, eat-harping, cat-head, cat-rigged, cat-roller, cat-stopper, cat-tail, and other technical terms with the same prefix too numerous to name.

Even the ship itself was sometimes known as a cat. This was specifically so in the Norwegian type of vessel, and the flat- bottomed fire-boats employed by the English against the French in 1804. The “Cat” of Dick Whittington is sometimes said to have been a ship, and colliers and trading-boats are often so designated. We should probably not be far wrong in assuming that the idea of using the name of the sacred animal protectively was borrowed from Egyptian mythology, which, passing through Italy, permeated European thought and was employed in nautical nomenclature with the deliberate intention of invoking the assistance of Isis, and warning her priestesses from harming the vessel that had placed itself in her care. Where witches are credited with the destruction of sea-craft (as the annals of English law-courts gravely record was often the case), we may suppose that no such appeal had been made by the sailors to the Queen Of the Deep, and that her votaries saw cause for anger in the too rude violation of the sanctified element. Some such religious or patriotic motive seems to have inspired the Witches of Mull, who, in the legend related by Dr. Macleod, are said to have assumed feline form in order to sink a hostile ship.

The Spanish king had sent a war vessel to the town with instructions that it was to avenge his daughter Viola, who had been murdered by Mrs. MacLean of Duart. But all the local witches took the shapes of cats and gathered together on the shrouds of the ill-fated ship in an effort to send her to the bottom. It so happened, however, that the captain also knew something of the art of magic, and was able to counteract their direful intent. So, seeing that they could not thus prevail, the witches enlisted the aid of the queen of Highland enchantresses, Great Garmal of Moy. She appeared on the top of the mast in the form of the largest cat ever seen, and she had only begun to sing one spell, when the vessel sank like a stone to the bottom.

A tale from the Isle of Skye related by the Rev, J. Gregorson Campbell has a peculiar interest, since it describes how a witch disguised as a cat, used a riddle [sieve] for a boat, and so makes clear the Egyptian influence responsible for such stories.

“A witch who left home every night, was followed by her husband, who wondered what she could be about. She became a cat, and went in the name of the devil to sea in a sieve, with seven other cats. The husband upset the sieve by naming the Trinity, and the witches were drowned.”

Reginald Scott tells us it was believed that witches “could sail in an eggshell, a cockle or mussel-shell, through and under the tempestuous seas.” But their favourite vessel was certainly the riddle or sieve, which was one of the emblems of Isis, and as such is often depicted on Gnostic gems. It will be remembered that it was upon a riddle the goddess collected the scattered limbs of her husband Osiris, after he had been slain and dismembered by his enemy Set, known to the Greeks as Typhon [Cp. typhon, a whirlwind; typhoon, a hurricane]. The Christian Church, following her settled policy of placing the Gentile gods in Hell, transferred the Sieve of Isis to Satan, who, in his own person, she made representative of practically all the ancient deities other than Jehovah, whether they were male or female. An article so readily available, and with such a history as the ubiquitous riddle, was naturally regarded as a most favourable instrument for bearing the devotees of Satan — formerly the priestesses of Isis — upon the waters which were her sacred symbol, and even for raising the devil himself.

And when we refer to Satan's activities on the waters, we are reminded of another link between ancient cosmogony and the devil of Christian dualism. For in his familiar cognomen, “Old Nick,” we recognise the ocean and river god Nicksa, or Nixas, who possessed the attributes common to Neptune and Isis, and was formerly worshipped on the Baltic shores. Amid the terrible tempests that tore those gloomy seas, their presiding deity naturally loomed forth as an enemy to mankind, and was readily identified as the Prince of the Power of the Air, who led the witches and warlocks in their wild flights, and delegated to them the ruling of the storm.

The earliest ecclesiastical law in England, the Liber Penitentialis of St. Theodore (Archbishop of Canterbury 668-690), was directed against those who by invoking fiends (i.e. the ancient gods) cause storms: “Si quis emissor tempestatis fuerit.”

>In the Capitaluria of Charlemagne, more than a hundred years later, the death penalty is decreed against such as by means of the devil disturb the air and excite tempests. And Pope Innocent VIII in his Bull (Summis desiderantes affectibus) of 1484 explicitly charges sorcerers with such practice.

Witches traded on these superstitions, and even went so far to sell favourable winds to sailors. Summer, writing in 1600, records how in his times:

“In Ireland and in Denmark both,

Witches for gold will sell a man a wind,

Which in the corner of a napkin wrapp'd,

Shall blow him safe unto what coast he will."

(" Last Will and Testament.”)

It does not appear to have been essential for the witch or wizard to assume the form of a cat in order to raise a storm, since in many recorded cases a mortal cat was used for the purpose with equally effective results. Thus Polson tells us Highlanders used to draw a cat through the fire in order to raise the wind when they wished to affect the progress of a ship at sea.

Sometimes quite an elaborate ritual was followed to attain the desired result. For instance, when Satan wanted to shipwreck King James and Queen Anne on their voyage home from Denmark, he taught his following warlocks and witches to take a cat and christen it, and cast it into the sea, calling “Hola!” which, he said, would raise a storm. His advice was practically carried out by John Fian, alias Cunninghame, master of the School at Saltpans, Lothian. This gentleman was described by Agnes Sampson, whose own calling made her an authority on the subject, as “ever nearest to the devil, at his left elbock.” Accordingly, in 1590, he was “fylit” in this connection, for the “chaissing of ane catt in Tranent; in the quhilk chaise, he was careit heich aboue the ground, with gryt swyftnes, and as lychtlie as the catt hir selff, ower ane heicher dyke, nor he was able to lay his hand to the heid off: And being inquyrit, to quhat effect he chaissit the samin? Ansuerit, that in ane conversatioune haldin at Brumhoillis, Sathan commandit all that were present, to tak cattis; lyke as he, for obedience to Sathan, chaissit the said catt, purpoiselie to be cassin in the sea, to raise windis for distructioune of schippis and boitis.”

A scarce black-letter pamphlet, entitled “Newes from Scotland, declaring the damnable Life of Doctor Fian, a notable Sorcerer,” describes him as , “Register to the Devil, that sundrie times Preached at North-Baricke Kirke to a number of notorious Witches,” and further discovers how “the said Doctor and Witches . . . pretended to Bewitch and Drowne his Majestie in the sea coming from Denmarke, with such other wonderful Matters as the like hath not bin heard at anie time.”

According to the indictment on which John was tried and convicted, the devil appeared to him in the night “appareled all in blacke, with a white wande in his hande,” and “demanded of him if hee would continue his faithfull service, according to his first oath and promise made to that effect, whome (as hee then said) he utterly renounced to his face, and said unto him in this manner ‘Avoide, Satan, avoide — I utterly forsake thee.’” But this renunciation did not save John, and after appalling tortures had been inflicted on him by command of the zealous King James and his counsel, hee was put into a carte, and being first strangled, he was immediately put into a great fire, being readie provided for that purpose, and there burned in the Castle-hill of Edenbrough, on a Saterdaie, in the ende of Januarie last past, 1591.”

An elaborate ritual for raising a tempest at sea by means of a cat is described in the confession of Agnes Sampson, “the wise wife of Keith,” who belonged to the same coven as John Fian. According to Wright's “Newes from Scotland,” “this aforesaide Agnis Sampson, which was the elder witch, was taken and brought to Haliriud-House, before the king's majestie, and sundry other of the nobilitie of Scotland, where she was straytly examined, but all the perswasions which the king's majestie used to hir, with the rest of his councell, might not provoke or induce her to confesse any thing, but stoode stiffely in the deniall of all that was layde to her charge; whereupon they caused her to bee conveyed away unto prison, there to receive such torture as hath beene lately provided for witches in that country. . . . Item. The sayde Agnis Sampson was after brought againe before the king's majestie and his councell, and being examined of the meetings and detestable dealings of those witches, shee confessed that of Allhollon-Even, shee was accompanied, as well, with the persons aforesaid, as also with a great many other witches to the number of two hundreth, and that all they together went to sea, each one in a riddle, or cive, and went in the same very substantially, with flaggons of wine, making merrie and drinking by the way in the same riddles or cives, to the kirk of North-Barrick, in Lowthian, and that after they had landed, tooke handes on the lande, and daunced this reill, or short daunce, singing all with one voice:

‘Commer, goe ye before, commer, goe ye;

Gif ye will not goe before, commer, let me.’

We are scarcely surprised to read that “these confessions made the king in a wonderfull admiration”; but Agnes had many more marvels yet to relate, and poured them forth into his royal ears. “She confessed that at the time when his majestie was in Denmarke, shee being accompanied with the parties before specially named, tooke a cat and christened it, and afterwards bounde to each part of that cat the cheefest parte of a dead man and severall joyntes of his bodie; and that in the night following, the saide cat was convayed into the middest of the sea by all these witches, sayling in their riddles or cives, as is aforesaid, and so left the saide cat right before the towne of Leith in Scotland; this doone, there did arise such a tempest in the sea, as a greater hath not bene seene, which tempest was the cause of the perishing of a boat or vessell comming over from the towne of Brunt Island to the towne of Leith, wherein was sundrie jewelles and rich giftes, which should have beene presented to the new queene of Scotland at her majesties coming to Leith.

“Againe it is confessed, that the said christened cat was the cause that the kinges majesties shippe, at his comming forth of Denmarke, had a contrarie winde to the rest of his shippes then being in his companie, which thing was most straunge and true, as the kinges majestie acknowledgeth; for when the rest of the shippes had a faire and good winde, then was the winde contrarie and altogether against his majestie. And further, the sayde witch declared that his majestie had never come safely from the sea, if his faith had not prevayled above their intentions.”

In the legal record of the witches' feat there is no mention of the sieves, but other details are supplied. The Coven of Prestonpans wrote a letter to the Leith Coven advising them to "mak the storm universall thro the sea. And within aucht dayes eftir the said Bill [letter] wes delyverit, the said Agnes Sampsoune, Jonet Campbell, Johnne Fean, Gelie Duncan, & Meg Dyn baptesit ane catt in the wobstaris hous, in maner following: Fyrst, Twa of thame held ane fingar, in the ane syd of the chimney cruik, & ane vther held ane vther fingar in the vther syd, the twa nebbis of the fingars meting togidder; than thay patt the catt thryis throw the linkis of the cruik, & passit itt thryis under the chimnay. Thare-eftir, att Begie Toddis hous, thay knitt to the foure feit of the catt, foure jountis of men; quhilk being done, the sayd Jonet fechit it to Leith; & about mydnycht, sche & the twa Linkhop, & twa wyfeis callit Stobbeis, came to the Pierheid, & saying thir words, ‘See that thair be na desait amangis ws’; & thay caist the catt in the see, sa far as thay mycht, quhilk swam owre & cam agane; & thay that wer in the Panis, caist in ane vthir catt in the see att xj houris. Eftir quhilk, be thair sorcerie & inchantment, (the boit perischit betuix Leith & Kinghorne.”

Pitcairn I, 2, 237.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“The Discoverie of Witchcraft.” By Reginald Scott. Printed 1584.

“The Rare and Singular Work of Pomponius Mela, that excellent and worthy Cosmographer,” Book III, Chapter 6. Trans, into English by Arthur Golding, Gentleman, London, 1590.

“Newes from Scotland, declaring the damnable Life of Doctor Fian, a notable Sorcerer, who was burned at Edenbrough in Januarie last, 1591. Pub. according to the Scottish Copie.” Printed for William Wright.