THE MODERN CAT - HER MIND AND MANNERS - AN INTRODUCTION TO COMPARATIVE PSYCHOLOGY

To My Mother.

INTRODUCTION

Many books have been written about cats. There are cat tales for children like "Puss-in-Boots" and "The White Cat," and stories for adults such as those collected by Carl van Vechten in his "Lords of the Housetops." Many poets have sung the charms of the feline, and the essayists, in such books as Agnes Repplier's "Fireside Sphinx," have given us some of our most delightful descriptions and interpretations of "Pussy's" behaviour. Medical men have written a number of volumes (which the cat lover will pass over hastily) on the dissection and the anatomy of the cat. There are treatises on the care and breeding of these animals and even magazines devoted entirely to such interests. "Natural histories" contain many stories about these pets. The cat has been viewed from many angles, the legendary, the poetic, the historical, the descriptive, the medical, the economic, even the legal. Nowhere, however, do we find a volume which deals exclusively with the mind of the cat.

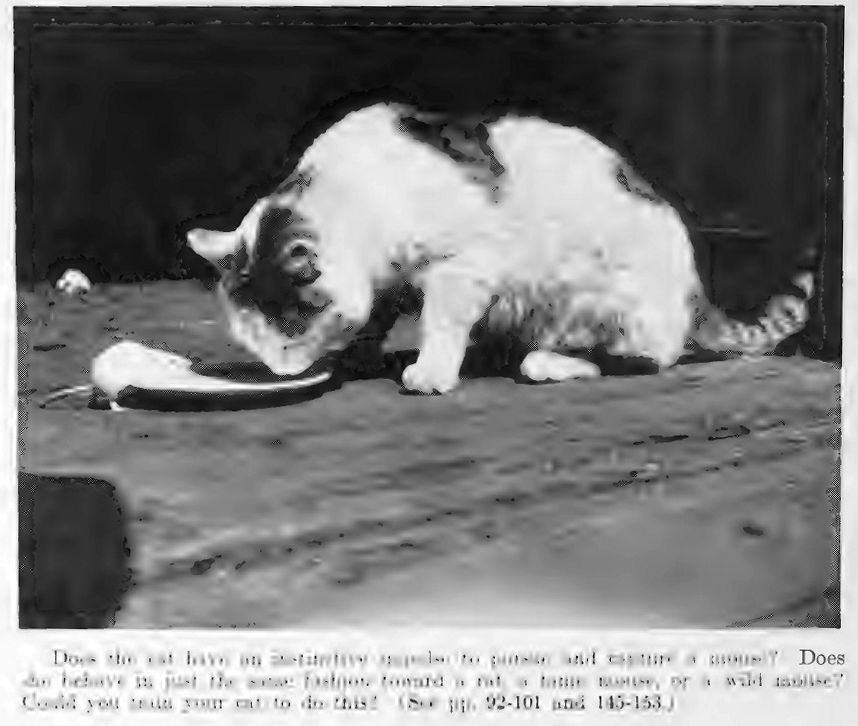

Many of us would like to find the answers to such questions as "Does my cat reason?" "How does she compare in intellectual ability with other animals, as the dog, the horse, the racoon, or her adversaries, the mouse or the rat?" "Does my cat see colours as I do, hear tones as I do?" "Why does a kitten catch mice; is this act an inherited instinct or something which she is taught to do by her mother?" "Is it true that the cat always finds her way home?" "Does she always land on her feet when she falls?" "Can my cat imitate me or another cat?" "How much can she learn?" "How may I train her and why is it that some methods succeed while others fail?" "Does my cat have emotions like mine?" "How can I tell from her appearance what she is feeling?" Does she have ideas, thoughts like mine?"

These problems are rarely mentioned in the typical book dealing with cats. Yet they are all questions on which careful experiments have been performed by students of comparative psychology. Some of the answers have been determined with approximate accuracy; in the solution of other problems only a beginning has been made.

I have tried to collect from the literature of psychology those facts which are pertinent to a discussion of cat behaviour and the cat mind. The book (like most of the other volumes) contains many "cat stories." But unlike most other treatises, it includes, with the exception of certain ones used for purposes of illustration, only "true stories," those which are as nearly accurate as science can make them. The tales are intended for two classes of readers: those who love cats and would like to know more about the explanation for their actions, and those who may wish to obtain, through a description of methods employed with one animal, a first glimpse of the ways of comparative psychology.

I am grateful to Professors H. L. Hollingworth and A. J. Gates for reading the manuscript. My debt to three authors, Professors Edward L. Thorndike and Margaret F. Washburn, and Miss Agnes Repplier is apparent throughout the book. To Mrs. E. A. Holton grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to use a photograph and to the following for the liberty of quoting: E. H. Forbush, E. W. Gudger, The Literary Digest, The Living Age, The Scientific Monthly.

CONTENTS

Introduction.LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

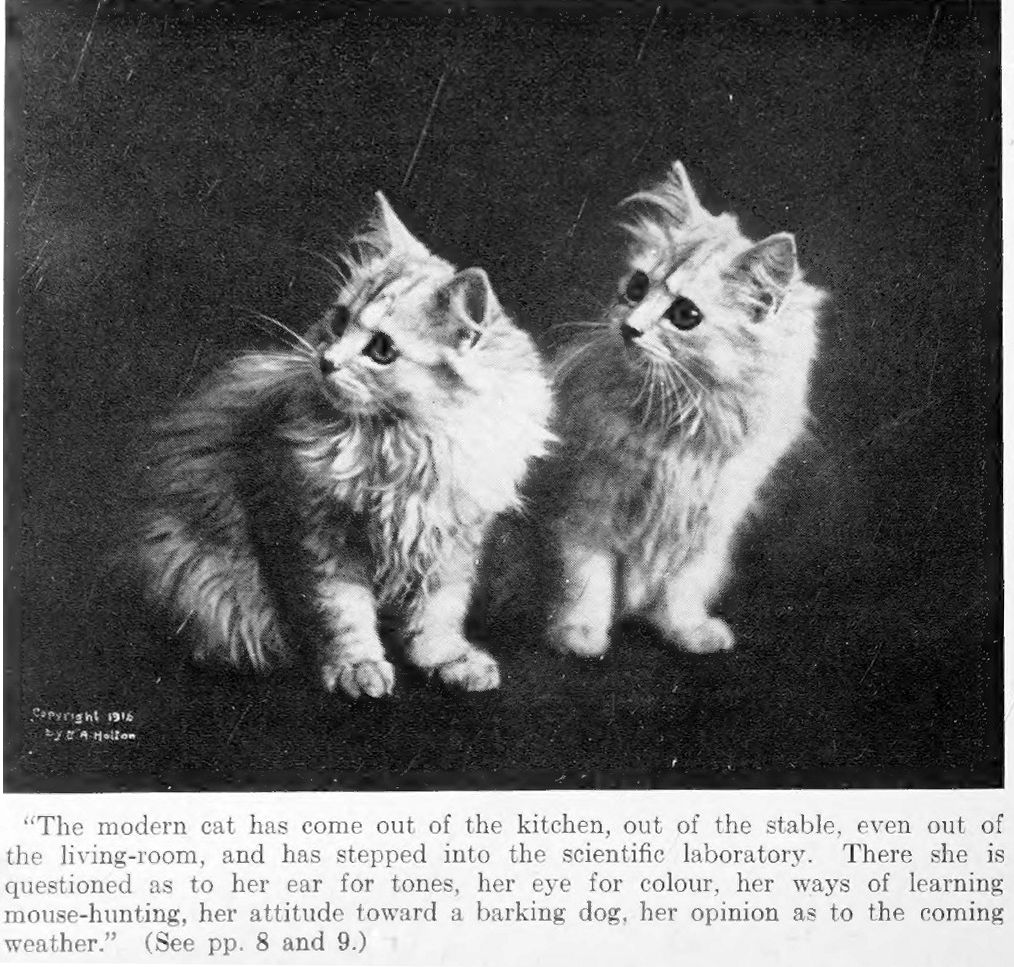

In the Laboratory - FrontispieceCHAPTER I - THE MODERN CAT

"Keeping cats is a mad practice, something like having children, but without that consciousness of public approval, of doing one's duty and of God being responsible, which sustains the courage of parents." (Atlantic Monthly (2), "The Contributor's Column.")

In much the fashion in which magazines and newspapers deal with the position of Modern Woman, of the Modern Infant, of Modern Marriage, and of Modern Music, we may attempt to define, with brevity, the standing in our nation of the Modern Cat.

With the possible exception of the cow, the cat seems to the unsophisticated eye to be, of all domestic animals, the one who has most opportunity for mental activity. She wastes no time bidding for our attention or bewailing our neglect as does the dog; she performs no time-consuming labours as does the horse; she lacks to our eyes, moreover, the appearance of feeble-mindedness which distinguishes the pig, or the preoccupation with alimentation for which the sheep and chickens are notable. You find her curled by the hour in front of the fire, or sitting all day long by the mouse hole, or on the mantelshelf looking down, or under the porch looking up. What is she doing? The simplest answer seems to many to be: "She just sits and thinks."

By providing herself thus with opportunity for contemplation the cat seems to have arranged her life in a most intelligent though possibly unethical way. She is like the lady of fashion who so directs her affairs that all necessary work shall be performed by some one else and her own time left free for pleasure. The cat gives the world nothing and receives from it everything. Like the goldfish she provides us with neither shelter, food, nor clothing (for "cat fur" though warm and pretty is for some reason socially taboo). But unlike the simple fish she suffers no curtailment of her freedom. Like the dog, she gains sufficient exercise in her own way and at her own time. But a blade of grass or a curtain tassel provides a much more accessible playfellow than a human being willing to whistle or throw sticks. And in spite of a life of relative freedom from care for food and shelter, her instinctive equipment remains such that if occasion arises, as when she is abandoned perhaps in the woods, she is much better fitted to resume a wild life than is the dog. But usually you find her in our homes. There she occupies a position much like that accorded by primitive theology to the deity. Her function is to sit and be admired.

To be sure we no longer accord the cat the wholehearted worship which the ancient Egyptians provided. We do not feel it necessary that a whole city, or even a whole family, should go into mourning on the death of a cat. We do not even shave our eye-brows when a kitten dies, nor do we maintain troops of cats in temples, fed on fish and bread dipped in milk, nor do we tear to pieces a "noble Roman" who accidentally kills a cat. On the other hand we do not view the cat with as marked uneasiness as did our ancestors of later date. If we find (and our forebears report definitely that they did make such discoveries), a cat on some dark night engaged in an unholy rite - such as dancing on a gravestone - and if in anger we cut off her right front paw, we do not expect next morning to discover that one of our neighbours - perhaps some shrewish old woman - has lost her right hand! Some of us even scoff at statistical evidence and are undisturbed in our belief in feline integrity when we learn that in the reports of witch-trials (collected by an eminent jurist) the Arch-Fiend appeared to his followers only sixty times as a cavalier, only two hundred and fifteen times as a he-goat, but nine hundred times as a black cat (38).

We would furthermore be offended were anyone to insist on presenting us with that medieval musical instrument, the "Cat Organ" in which sounds of various pitches and intensities were provided by the simple expedient of pulling the tails of a number of tethered cats. A recommendation to punish a murderess (even for a most heinous crime) by hanging her in an iron cage over a slow fire, accompanied by fourteen cats (who as Agnes Repplier tells us "had killed nobody"), would be instantly vetoed by every honest citizen.

To be sure there are even now the unfriendly critics; like the modern woman and the modern dance, the cat has her enemies. Shaler (41) describes the cat as the "one animal which has been tolerated, esteemed and at times worshipped without having a single distinctly desirable quality." Students learning psychology and anatomy are required to put her to uses which would be abhorrent to the normal "cat fan." During the war the British government advertised for "common cats - any number." They were used to detect gas in the trenches, as white mice and canaries were employed in the American army. One writer (17) in an excellent treatise called "The Domestic Cat" occupies most of his space in recounting her depredations to birds, chickens, weasels, squirrels, rabbits, moles, shrews, bats, and toads, and includes in his book sections headed "Animal Substitutes for the Cat," "Methods of Taking and Killing Stray or Feral Cats," "Is the Cat a Disseminator of Disease?" The same author states that the cat's value as a mouse-trap has been much overrated, and suggests that her chief advantage over the commercial trap is that she is "self-setting."

But most of us continue to treat the cat as a friend, as did Ben Johnson when he bought oysters for his fastidious pet, or Victor Hugo whose cat sat unrebuked on his dias, or Matthew Arnold when he described feline gambols, or Sir Walter Scott who encouraged his pet's despotic rule of his bloodhound, or Lord Chesterfield who left his cat a pension, or the Brontes, or Richelieu, or Mahomet, or Petrarch, or Henry James, or Robert Southey, or Horace Walpole, or Gregory the Great, or Cardinal Wolsey, whose intimate companion she was. We tend to applaud the action of that president of the United States who when leading a procession turned aside in order not to disturb a complacent grey cat lying in the way, and thus made a whole line of ambassadors, high officials and distinguished women detour about the animal.

We are unwilling to go so far as did the lady who inserted this well-known advertisement in a German newspaper: "Wanted by a lady of rank, for adequate remuneration, a few well-behaved and respectably dressed children to amuse a cat, in delicate health, two or three hours a day" (17).

Yet there is scarcely a person who does not stoop to pet the cat in the grocery store. We continue to permit her to occupy our hands in smoothing and stroking, to consume our milk (which the dieticians tell us is our most perfect food), to claw the rugs and leave hairs on the upholstered furniture, to disturb our nights with her music without melody, to put us to distasteful tasks in the matter of drowning the young and wriggling.

Whether we consider her as ally or enemy, whether we believe her to be the most contemplative or only the "sleepiest" of friends, the most astute or the most stupid of our pets, we continue to be curious about her mental life (if she has one). We write to the newspapers about the exploits of our own and our neighbours' cats; we develop all sorts of theories concerning her "jealousy," her "cruelty," her "love of home," her "maternal passion."

We read about her in encyclopaedias and natural histories. There we learn that relative to their size, "cats are the fiercest, strongest, and most terrible of beasts" (25), or we hear that "so far as mere agility goes, the common house cat probably surpasses all its clan, if not every known species of quadruped. It can catch its (comparatively diminutive) prey with as much skill and celerity as any tiger or jaguar' (36). The cat is distinguished among carnivora for the flexibility and strength of her spine, for her small head, her loose skin, and especially for her suppleness, speed, and the muscularity of her jaws and limbs. All the cat's "anatomy represents agility and power to the highest degree" (34).

Most interesting to the naturalist are the cat's claws. They are used to seize and hold the prey till the animal can get the better of it by biting it in the neck. They facilitate motion on steep inclines or slippery surfaces. They must therefore be flexible and capable of a powerful grip. At the same time it must be possible to keep them out of the way when the foot is used for walking, and to prevent them from being blunted by continued contact with the ground. The muscular arrangement for protruding and retracting the claws provides for all these circumstances (34).

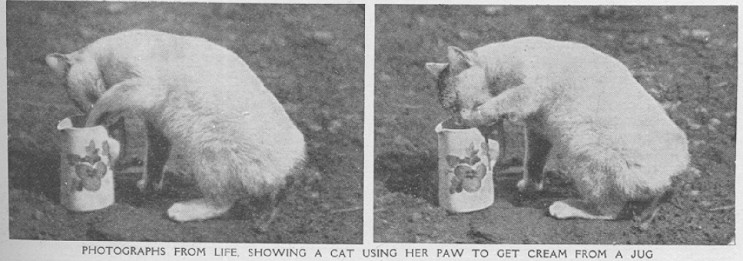

The fore-limbs have a freedom of motion about equal to that of the apes and monkeys. They can be stretched out, turned, can strike a blow as easily as can a man's fist (25). The tiger can smash the shoulder blade of an ox or buffalo at a single stroke and the domestic cat is, in her own realm, similarly efficient.

The rough tongue enables the cat to lick clean the bones of her prey, her teeth tear or chop or cut like scissors, but do not grind (26). One author tells us that the cat in combat represents the female sex of the carnivorous quadrupeds - displaying the "feminine traits of timidity, deceptiveness, indirectness and use of the tongue as practical weapons of offense" (36).

The feline mode of life is described as spasmodic (33). The cat alternates periods of intense activity with times of deep repose; at one time she is pursuing, springing upon, "torturing" the mouse, every muscle active; in a moment you find her curled in the corner purring. We are told that cats are very difficult to train or tame, and that a certain "inflexibility" in their behaviour is paralleled in their structure for they go on from generation to generation with very little change in anatomical features. After three thousand years of domestication, we have very few distinct breeds of cats (33).

All very interesting and useful. But what of the cat's mind? What goes on behind those strangely inscrutable eyes? As she curls self-sufficient on the best chair, is she merely admiring her own astuteness in achieving bodily comfort, or reviewing with pride her appearance after a recent bath, or her last encounter with a mouse, or contemplating the meal to come or the meal just past? Or is she perhaps engaged in commenting critically, though, of course, sub-vocally, on her human companions or the decoration of the room? Or are her thoughts so different from these and so different from human thoughts in general that the two can only with difficulty be compared?

The modern cat has come out of the kitchen, out of the stable, even out of the living room, and has stepped into the scientific laboratory. There she presides, not in the cringing manner of the aid to medical research, but as the treasured enigma, the sphinx (no longer of the fireside), whose riddles the scientist would like to solve. She is treated (frequently, at least) as an honoured guest; problems are carefully arranged to suit her capacity. Fish of peculiarly enticing odour is provided. Mice, both living and dead, of all sizes and consistencies, are furnished. She is questioned as to her ear for tones, her eye for colour, her ways of learning mouse hunting, her preference for light or vigorous punishment, her attitude towards a barking dog, her opinion as to the coming weather. Scientists sit about with notebooks and stop-watches contemplating her. An observer reports that his animals often "purred during the experiments" (14). Who would not?

The cat holds a prominent place in psychological research. She has the honour of acting as the chief subject in a series of experiments which marked the beginning of the laboratory study of the higher animals. The investigations had such far-reaching effects that, sixteen years after their completion, L. W. Cole complained that the psychology of mammals was still "a mere generalization of the psychology of cats" (9).

Not only did these studies initiate other researches in the field of animal behaviour, but they resulted in discoveries which were applied with marked success to the interpretation of human action. School children rejoicing in easier modern methods of learning algebra and arithmetic and even reading or spelling, would be surprised to know that their teachers had studied and were applying "principles of learning" first promulgated after prolonged study of the reactions of hungry cats! Some time before "intelligence tests" were so widely used in diagnosing human difficulties, cats were being tried out in situations which taxed their powers of learning.

We may ask two questions about this modern cat. First, what methods shall we use in investigating her mind? Second, what are the results of such researches? First, we shall review the behaviour of the cat, what she actually does under experimental conditions. Then we may investigate theories as to how she feels.

CHAPTER II - STORIES ABOUT CATS

"Cats are a mysterious kind of folk. There is more passing in their minds than we are aware of. It comes no doubt from their being so familiar with warlocks and witches." (Sir Walter Scott.)

The time-worn method of investigating the animal mind is to collect anecdotes from friends, periodicals, "nature books," even perhaps from works of fiction, and having assembled a number of stories to attempt an interpretation. Many of us are inclined to do even less than this and to base our conclusions on only one or two such cases.

If you should stand on the street-corner and in the manner of a reporter on a daily paper ask the first six persons who were willing to listen to you, "What is your opinion? Do you believe that cats reason?" you would probably get answers much like the following. These were actually collected by students of animal psychology from waitresses, clerks, elevator boys, members of their own families, and other persons whom they encountered.

"I think they do. I'm sure our cat reasons. If she hears anyone coming, she runs to a room where she can see out of the window, and looks to see who is coming. If it is some one she knows, she comes to see them, but if it is a stranger she hides."

"Yes. Our cat enjoys being in front of the gas fire in the dining room and when the waitress did not light the fire the other morning, she looked at the fireplace and mewed."

Or you might get replies of this kind -

"I'm sure my sister's cat doesn't reason. When she calls him, he comes, but he doesn't seem to think about it. When he is hungry, he will go to the pantry and look for his food. My sister thinks this shows great intelligence, but to me he just seems to go there without thinking about it, in a lazy, half-sleepy fashion."

Perhaps half of the persons questioned will reply that cats surely do reason, perhaps the other half will answer just as certainly that feline reasoning is incredible. It will be a rare individual who will question you further and attempt to discover what you mean by "reason" or who will base his answer on the behaviour of more than one or two cats of his personal acquaintance. Whether the answer shall be favourable or unfavourable to the cat's mental powers will depend more than anything else upon the particular animals and the particular situations encountered. One man will be impressed by what appears to him to be a particularly stupid bit of behaviour. Another may just have witnessed a feat performed by a cat which, because it was unique, impressed him greatly.

Convinced of the inadequacy of such methods of inquiry, we go next to literature for anecdotes about cats. There we find essayists, novelists, and poets writing most charmingly about her whom they always designate as "Puss."

What child can resist, or what adult either, when he forgets for a moment his preoccupation with truth as science sees it, the exploits of Puss-in-Boots, of Dick Wittington's cat, of the Cat who Walked by Himself ( and all places were alike to him"), or even of the Kilkenny Cats -

There wanst was two cats in Kilkenny,

Aitch thought there was one cat too many

So they quarrelled and fit,

They scratched and they bit,

Till, excepting their nails,

And the tips of their tails,

Instead of two cats, there wasn't any.

Or what reader of fairy tales does not experience regret when the unique and charming little White Cat was beheaded by the Prince and turned on the instant into an ordinary, every-day Princess?

The most delightful legend about the cat is perhaps the following, a story found in the mythology of many countries, which is here quoted as Shelley told it.

"A gentleman on a visit to a friend who lives on the skirts of an extensive forest, on the east of Germany, lost his way. He wandered for some hours among the trees, when he saw a light at a distance. On approaching it, he was surprised to observe that it proceeded from the interior of a ruined monastery. Before he knocked, he thought it prudent to look through the window. He saw a multitude of cats assembled around a small grave, four of whom were letting down a coffin with a crown upon it. The gentleman, startled at this unusual sight and imagining that he had arrived among the retreat of fiends and witches, mounted his horse and rode away with the utmost precipitation. He arrived at a late hour at his friend's house, who had sat up for him. On his arrival, his friend questioned him as to the cause of the traces of trouble visible in his face. He began to recount his adventure with some difficulty, knowing that it was scarcely probable that his friend should give faith to his relation. No sooner had he mentioned the coffin, with the crown upon it, than his friend's cat, who seemed to have been lying asleep before the fire, leaped up, saying, "Then I am the King of the Cats!' and, scrambling up the chimney, was seen no more."

This tale is quoted in a pleasant book by Marion Clark, published in 1895, and called Pussy and Her Language (8). There the author suggests ironically that the story shows not only the attention which cats (even when apparently indifferent) pay to human conversation, but also the "monarchical character of their political organization."

A similar tale in verse is described as a characteristic legend of Northern Nations.

THE TROLL CAT

Knurremurre rules with a will

All the trolls in Brondhor Hill.

Throughout all Zealand has it rung -

The fame of Knurremurre's tongue.

One young troll got tired of the worry,

"I'll away," said he,

"To company

More pleasant than Knurremurre."

"Wife, what scratching at the door

On this cold winter night?"

The gales through the snow-heaped forests roar,

And the hut-fire is burning bright.

"Open the door, good wife," says Plat -

In walks a stately whiskered cat,

He sits by the fire and dries his fur,

And purrs his thanks with a loud long purr,

And eats his groute and washes his face,

And makes himself at home in the place.

Weeks pass on, a good cat he,

He is quite one of the family,

For the kindly wife of Plat,

In her wooden hut by the northern sea,

Has a poet's love for a cat.

Tis night; the cat by the hearth fire lies

Purring and dozing with blinking eyes;

When Plat comes in and says - "Good wife!

What strange things happen in one's life!

I saw a sight

As I came tonight

By Brondhor Hill,

Where all was still

Save the trolls who hammered below with a will,

Out jumps in my way

A man old and gray,

And squeaking he said -

Hearken, Plat!

Tell your cat

That Knurremurre is dead.' "

Up jumped the cat from the hearth-fire side -

"Ho! Knurremurre dead!" he cried -

"Now I may go home, I ween."

And out he scampered with a will

Out through the night to Brondhor Hill,

And nevermore was seen.

In humorous vein, Clark describes the consternation which would ensue did it become generally known that the "little innocent who hears the family secrets," "the ever-present spy," was capable of communicating her information. That this is the case, that the "feline community" does possess a language of its own has been revealed to him by a mysterious document, called "The Discovery of the Cat Language," left to him by a gentleman who bore a card reading

ALPHONSE LEON GRIMALDI, F.RS., F.b.S., M.O., D.H. du C., M.F.A.S., M.F.A., et al,

Rue de Honore, 13, Paris. Metropolitan Hotel, N. Y.

The article, which was much gnawed by mice, though the author does not know whether "in a spirit of vandalism and to demonstrate the hatred of the destroyer for the subject of the story, or with a mere wanton desire to destroy my property," is described as an attempt to demonstrate not only that the cat is a more delicate organism than the dog; that she is of a higher order of intelligence than any other four-footed beast; that with proper opportunity, she would lose those attributes which make some of us dislike her and acquire dog-like characteristics; but also that she possesses a language much like the Chinese and possibly derived from it. In the word part of the language there are, probably, not more than six hundred fundamental words, all others being derivatives.

I shall quote a few of these words for the benefit of those individuals who may be moved to communicate with their pets in this fashion.

"Purr-r-r-r-r-r-rieu" means "happy," "mieouw" with a strong emphasis on the first syllable "beware," "aelio" is "food" and "alieeo" is water, "parrierre" is uttered in front of the door and means "open," the numbers begin "aim, hi, zali," "leo" is the head, "tut" the tail," "oolie" the fur, "ptter-bl" is mince-meat and "bleeml-bl" cooked meat. The sentence "mie-ouw, vow, vow, telow you tiow, wow yow, ts-s-s s-syw," is a mixture of defiance and a curse and much resembles "bold, bad swearing."

Many cats who do not aspire to the gift of language are famous, not because their own behaviour was in any way unique, but because their masters, men of talent, interpreted it so delicately and charmingly.

Such was Pierre Loti's Moumoutte Chinoise, described by Agnes Repplier as the "Jane Eyre of pussies, ugly, intelligent, secretive, passionate, self-controlled, intrepid and vivacious" (38), or Gautier's various cats, including Madame Theophile and Eponine. The latter is described as being most hospitable, willing to receive guests and entertain them till her master enters, having, moreover, her own place at the table, where she behaves "with a gentleness and decency which might be imitated by many children. She is very punctual, coming as soon as she hears the bell, and when I enter the dining-room, I find her already in her place, her paws folded on the tablecloth, her smooth forehead held up to be kissed, like a well-bred little girl who is politely affectionate to relatives and older people" (38).

As the astronomer does not take account in his writings of imaginative tales of life on the moon, nor is the physicist disturbed by H. G. Wells' stories, so the comparative psychologist can make no use of such tales other than to admire and enjoy them. The stories of "Puss" depicted as a graceful lady, an astute cavalier, a monarch, a gossip, entertain us greatly, but give us no real information concerning the cat mind. We turn to "nature books," or to magazines or newspapers purporting to describe the behaviour of these animals with approximate accuracy, and to advance, in some cases, arguments concerning their reasoning powers. We find cats famous for various causes.

One animal, whose name is now Thomas Cadillac, became well-known because, shipped by accident from America to Sydney, Australia (a seven weeks' trip), within a Cadillac chassis with nothing to eat but grease, oiled paper from the engine and, of course, the book of instructions, he survived the ordeal. He subsequently had his life insured for $5,000, posed for the motion pictures, and dined from the gold service at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco. The evidence provided here is of the type to favour the theory of nine lives rather than that of high intelligence.

Other stories describe instances of friendships between cats and dogs, or cats and horses, or even cats and mice. There are tales of cats who adopted puppies or chickens, cats who fought successfully with hawks and alligators, who resented injuries, accused murderers, punished marital infidelity, were excessively fond of brandy or valerian, of cats who came to their owners and attempted to communicate bad news, as the death of a kitten. "John Harvard" was famous, not only because, in spite of her name, she produced three kittens, but because on the night when the family decided to get rid of her, she warned them, by her mewing, of a conflagration, and thus saved not only their four lives, but her own nine.

Such stories are entertaining mainly because of the singular character of the incidents described, rather than because of the light which they may throw on the possible reasoning powers of cats. Other tales are definitely intended by their writers to be evidence of the unique intellectual ability of the feline.

In Cassell's "Popular Natural History," published 1817-1865 (6), we find the following somewhat gruesome tale of wisdom rewarded. "De La Croix witnessed, however, a display of extraordinary sagacity. I once saw,' he says, a lecturer on experimental philosophy place a cat under the glass receiver of an air-pump, for the purpose of demonstrating that very certain fact, that life cannot be supported without air. The lecturer had already made several strokes with the piston, in order to exhaust the receiver, when the animal, who began to feel very uncomfortable in the rarefied atmosphere, was fortunate enough to discover the source whence her uneasiness proceeded. She placed her paw on the hole through which the air escaped, and thus prevented any more from passing out of the receiver. All the exertions of the philosopher were now unavailing; in vain he drew the piston - the cat's paw effectually prevented its operation. Hoping to effect his purpose, he let air again into the receiver, which, as soon as the cat perceived, she withdrew her paw from the aperture; but whenever he attempted to exhaust the receiver, she applied her paw as before. All the spectators clapped their hands in admiration of the wonderful sagacity of the animal and the lecturer found himself under the necessity of liberating her, and substituting in her place another, that possessed less penetration and enabled him to exhibit the cruel experiment.'" Perhaps the astute reader can discover some explanation of the cat's behaviour less exciting but more probable than "penetration" and "wonderful sagacity."

In a book called "Sketches and Anecdotes of Animal Life" written by the Rev. J. G. Wood, M.A., F.S.S., etc., in London in 1861 (66), the purpose of which was "to see how that portion of reason implanted in animals can overcome their natural instincts whenever the occasion requires," we find this event described - "Four cats, belonging to one of my friends, had taught themselves the art of begging like a dog. They had frequently seen the dog practise that accomplishment at the table, and had observed that he generally obtained a reward for so doing. By a process of inductive reasoning, they decided that if they possessed the same accomplishment, they would in all probability receive the same reward. Acting on this opinion, they waited until they saw the dog sit up in begging posture, and immediately assumed the attitude with imperturbable gravity. Of course their ingenuity was not suffered to pass unrewarded and they always found that their newly-discovered accomplishment was an unfailing source of supplies for them."

This story is of value in connection with our subsequent discussion of the experimental evidence for the existence of imitative ability in the cat.

The same writer, in a volume called "Illustrated Natural History" (65), describes a mother cat's behaviour when her kitten was given to him. "Minnie knew perfectly well that her kitten was going away from her and, after it had been placed in a little basket, she licked it affectionately, and seemed to take a formal farewell of her child. When I next visited the house, Minnie would have nothing to do with me, and when her mistress greeted me, she hid her face in her mistress' arms. So I remonstrated with her, telling her that her little one would be better off with me than if it had gone to a stranger, but all to no purpose. At last I said, Minnie, I apologize and will not so offend again.' At this remark Minnie lifted her head, looked me straight in the face, and voluntarily came on my knee. Anything more humanly appreciative could not be imagined."

Shall we credit this to understanding of language or to something much simpler?

Clark quotes a story of a cat who, when her master was sick, assumed the position of head nurse and directed when medicine was to be taken - "It was truly wonderful to note how soon she learned to know the different hours at which I ought to take medicine or nourishment, and, during the night, if my attendant was asleep, she would call her, and if she could not wake her without such extreme measures, she would gently nibble the nose of the sleeper, which never failed to produce the desired effect." She was, furthermore, "never five minutes wrong in her calculation of the time," even though there was no striking clock in the house "amid the darkness and stillness of the night." The master's amazement would have been changed - at least in its direction - had he some knowledge either of the laws of evidence or of feline psychology.

Romanes, one of our most famous writers on animal behaviour, describes in "Animal Intelligence" (40), which was "an attempt to write something resembling a text-book of the facts of Comparative Psychology," various anecdotes about cats. These animals, he says, "in the understanding of mechanical appliances ... attain to a higher level of intelligence than any other animals, except monkeys and perhaps elephants."

He gives one instance of "zoological discrimination." A cat, who was in the habit of poaching young brown rabbits to "eat privately in the seclusion of a disused pigsty," one day caught a small black rabbit and, instead of eating it, as she always did the brown ones, brought it into the house unhurt, and laid it at the feet of her mistress. "She clearly recognized the black rabbit as an unusual specimen, and apparently thought it right to show it to her mistress." Again, one is inclined to ask whether the author is reading more into the cat's mind than is implied by her behaviour.

Romanes describes cats who, when they want milk, summon servants by pulling the wires of bells. "My informants tell me that they do not know how these cats, from any process of observation, can have surmised that pulling the wire in an exposed part of its length, would have the effect of ringing the bell, for they can never have observed any one pulling the wires. I can only suggest that in these cases the animals must have observed that when the bells were rung, the wires moved, and that the doors were afterwards opened; then a process of inference must have led them to try whether jumping on the wire would produce the same effects. But even this, which is the simplest explanation possible, implies powers of observation scarcely less remarkable than the powers of reasoning to which they gave rise."

He tells us this tale also: "To give only one other instance of high reasoning power in this animal, Mr. W. Browne, writing from Greenock to "Nature" (vol. XXI, p. 39), tells a remarkable story of a cat, the facts in which do not seem to have admitted of mal-observation. While a paraffine lamp was being trimmed, some of the oil fell upon the back of the cat, and was afterwards ignited by a cinder falling upon it from the fire. The cat, with her back in a blaze, in an instant made for the door (which happened to be open) and sped up the street about 100 yards, where she plunged into the village watering-trough, and extinguished the flame. The trough had eight or nine inches of water, and puss was in the habit of seeing the fire put out with water every night. The latter point is important, as it shows the data of observation on which the animal reasoned."

Romanes' best story, since made famous by another investigator, we shall save for the next chapter, where we shall also include a more probable explanation of the behaviour just cited.

It is not only in the older text-books that we find remarkable tales of animal prowess. Newspapers and magazines are full of such stories today.

The "Literary Digest" for November 8, 1924, reports this story of thwarted cunning, which was entered in an animal contest held by the Boston Post. Fred G. George, of Meriden, Conn., is the author of the tale. "As a general thing, cats are not noted for their reasoning powers, but an incident which happened recently in our yard has proven that they do at times show considerable cunning. We have three adult cats at our house and in our front yard is a maple tree where squirrels make their home; on the side of our house, about 100 yards from the maple tree, is a hickory-nut tree, and between these two trees the cats and squirrels have been running races for some time, with the squirrels always winning by inches. The cats seemed to realize that it was a waste of effort to catch Mr. Squirrel, so seemed to grow indifferent as to his presence, but it would seem that they were plotting the downfall of their enemy.

"One day, as a squirrel left his home tree for his morning meal on nuts, the three cats sat lazily blinking; suddenly, as if by pre-arrangement, Tom' made a bee-line for the walnut tree, Blackie' made a wide detour to get on the opposite side of the squirrel's route; the white cat remained stationary, but on the alert. Suddenly the two cats rushed Mr. Squirrel, who quickly about faced' so that the two cats came together in a terrific head-on collision. As they sat gazing at each other in a dazed condition, the squirrel was laughing at them from his home' tree, while "Tom' sat lazily blinking at the base of the walnut tree."

W. H. Hudson, writing in the "Living Age" (June 18, 1921) (28), attempts to prove that cats "have something more than just the unreflecting intelligence which we find in all creatures, from whales and elephants to insects - something which in many instances cannot easily be distinguished from what we call reflection in ourselves." He tells the story of a lady who served afternoon tea in the garden and at the same time a tea of bread and cake for the birds. Her cat was in the habit of stalking the birds who congregated, but "invariably, just before the moment for making his dash, they would fly up into the branches of a tree." This continued apparently for some days (the number is not stated), when, instead, the cat seated himself in the middle of the "becrumbed area" and waited for the birds to come down. He waited for an hour, then walked away and repeated this procedure for three days; on the fourth day he did not even look at the birds and never thereafter did he pay any attention to them. "In this instance, the cat had made a fool of himself all the time, a bigger fool when he changed his strategy than before - but the very fact that he did change it appears to show reflection. He didn't know the mind of a bird as well as we do, but he hit on an idea - one must use the word in this case - that it was his conspicuous advance over the smooth lawn which alarmed and sent them away; that if he dispensed with the advance and established himself beforehand where the food was, and sat still, they would come to devour it and he, being on the spot, would have no difficulty in catching them! After giving this second plan three days' trial, he was convinced that it was as useless as the former one, and so gave it up for good." Again, even a superficial acquaintance with the methods of learning employed by animals would have led this writer to make a vastly different interpretation of the cat's behaviour.

He tells another story of a cat who experienced difficulty in transporting her kittens; she then remembered her friend, the dog, "mentally visualizing him as a big, strong creature with a big mouth to carry, and remembering also that he was obedient to her and quick to respond to her wishes.". . . "Her actions undoubtedly show reasoning of a higher kind than that of the cat described in the first part, though that too was reasoning. His impulse was to dash at the bird, but in the pause before it could be made, he listened to the still small voice of the higher faculty telling him that he would fail again as he had failed many times before."

Our crowning anecdote (23), purporting to prove the ability of the cat, is a case of telepathy, the first ever met with between human and cat. This is of unusual importance, for, as the author tells us "that such communication between mind and mind . . . should be possible between man and animals is but a further proof that they are mentally very near to us; that their brains function even as ours do, far as we have risen above them in all mental powers."

Mrs. Barry, the wife of the late Bishop Barry, possessed a cat which was most unusually attached to her mistress because she had saved the cat's life from a dog just two minutes (note the scientific accuracy!) before her first kitten was born. The cat lived in a house that was supposed to be haunted, but the raconteur admits quite openly, "I do not know whether it could in any way have affected the cat." The animal was left in charge of the gardener during the absence of her mistress, who one night dreamed that she was walking on a favourite path where the cat was accustomed to follow up and down. The lady heard a piteous cry and, looking up, saw "Puss" starved to death and very weak. The cat came to her three times (note the scientific accuracy of the figure) that night. In spite of the protests of her family, Mrs. Barry rushed off the next morning to succor the cat, and found, of course, as happens in all good stories of telepathy, the identical animal in the identical spot and condition. She states, "This story is perfectly true. Who can explain the fact of the cat spirit being able to make an impression on a human spirit so as to induce me to act as I did and in time to save her life?"

This tale makes a fitting end to our survey of cat stories.

CHAPTER III - THE EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

"There is no answer, there is no answer to most questions about the cat. She has kept herself wrapped in mystery for some 3,000 years, and there's no use trying to solve her now." - Virginia Roderick (39).

Shall we accept these tales as fact and shall our picture of the cat mind be a composite portrait drawn from such sources, or is there some other method which will give a better understanding of feline intelligence? What are the objections, first of all, to the anecdotes just described? What would a scientist say if you told him one of these stories and asked for his comment upon it?

He might, if sufficiently interested, ask three questions:

1st. Is this story true? did the events really happen just as described?

2nd. If all the circumstances are as pictured, is the interpretation given by the story-teller adequate?

3rd. How many events of this kind can be reported? Is this merely a chance occurrence or one of many representative instances?

How can we tell whether the tale is true? Is it advisable to depend on the accuracy of observation of the story teller? Some of our tales are very old and the cats have been dead fifty or a hundred years and their masters possibly half as long. Even where our stories come from contemporaries, we have no means of questioning them further. Can we be certain that two independent observers would agree? Many of the events were witnessed by clergymen, bishops, personal friends of the writer, etc. Are even educated and intelligent persons always accurate observers?

We may recognize the good intentions of the writers, and applaud their efforts to observe with care. Yet we may doubt their ability. A comparison of witnesses often reveals discrepancies. Five psychologists and a physician (all persons who had been trained to observe accurately) were walking in the woods one day when a man approached, pointed a pistol at them, and after some discussion of the right of way over the property, permitted them to depart. After the event, the friends compared their impressions. Two of the observers had seen a young woman in knickers with the gunman, one had seen a young boy with him, one had seen a child, two had observed no companion. One said the man held a mask in his left hand, another that he had a bunch of grasses, the others that he carried nothing. One had observed him wearing spiral leggings, another leather puttees, another golf stockings. The only fact on which the friends agreed was that the gentleman they met certainly had a pistol and certainly had pointed it in their direction. When trained observers disagree thus on facts in which they can have no personal interest or bias, how can we expect men of less experience always to be accurate when they are trying to tell a good story about a beloved cat?

Romanes states concerning his stories that "the most remarkable instances of the display of intelligence were recorded by persons whose names were more or less unknown to fame. This, of course, is what we might antecedently expect, as it is obvious that the chances must always be greatly against the more intelligent individuals among animals happening to fall under the observation of the more intelligent individuals among men" (40).

Even this most credulous student of animal behaviour notes a negative relationship between a good story and a famous man. His interpretation of the fact is probably inaccurate. Possibly his less intelligent observers were merely the more credulous.

Intelligent and unintelligent observers alike suffer from the following disadvantages, according to Washburn (59), any one of which may be illustrated by the stories in the preceding chapter. The story-teller is neither scientifically trained to distinguish what he sees from what he infers nor intimately acquainted with the habits of the species to which the animal belongs, nor the past experience of the individual animal. Furthermore, he usually has a personal affection for it, a desire to show its superior intelligence, and to tell a good story.

These last objections apply not only to the accuracy of the observation, but also to the validity of the interpretation, the second point which our scientist - would question. A gentleman who had just come from Chicago to New York, went to call upon a medium there, without telling any of his acquaintances of his intention. After taking off his coat and hat, he was ushered into the seer's presence. She greeted him with the words, "How are things in Chicago?" This man could interpret this occurrence in various ways. He could believe that a "spirit-control" had told the medium about his recent arrival in the city. He could think that the seer possessed the power to read his mind and so would know that his thoughts were still concerned with his journey. He might decide that mediums have some elaborate and mysterious organization that enables them to secure information concerning all their visitors, or he could merely recall that his overcoat bore the label of a Chicago firm and that the words, "How are things in Chicago?" implied no further knowledge of his connection with that city than that he had been there long enough to buy an overcoat; and that this sentence would be equally startling, were he in the mood to be amazed, had he left the city the day before or a year previous.

Which interpretation shall he choose? The explanations in terms of thought transference, or communication with the dead, are more exciting to the human imagination and make, in general, more remarkable stories. Learning one's previous home from a label on an overcoat is a commonplace procedure which any ordinary individual could employ. What makes the medium entertaining is that she claims to be a person of extraordinary ability, and the raconteur naturally prefers evidence of supernatural powers. The scientist, however, warns him against this tendency and tells him that in order to compensate for it he must make especial efforts always to consider and to give preference to the simplest explanation.

So, if we wish to approximate the truth in our interpretation of cat behaviour, we must take account of this habit of enjoying the unusual and accepting the marvellous; and even though we should like to believe that our cat understands our language, can tell time, appreciate the suction pump, love and hate as we do, we should still continue our search for a simpler and more credible interpretation of behaviour. The stories in the last chapter can all be explained quite readily, as we shall see presently, either on the basis of errors in observation or errors in interpretation.

Furthermore, this warning to prefer the simplest explanation reminds us that the stories represent only one side of the picture, animal intelligence rather than animal stupidity. The man who goes to a medium and hears nothing at all unusual, rarely tells his story, certainly he never publishes it. Thorndike says, "Thousands of cats on thousands of occasions sit helplessly yowling, and no one takes thought of it or writes to his friend the professor; but let one cat claw at the knob of a door, supposedly as a signal to be let out, and straightway this cat becomes representative of the cat-mind in all the books" (52). A cat book or a cat magazine giving instances only of feline stupidity would prob- ably not be well received.

There is another method of investigating the accuracy of these stories, other than that of doubting the competence of the witnesses, the validity of the interpretation, or the universality of the behaviour. This is the method of experiment which the psychologist has for a number of years been applying to cats as well as to other animals.

The scientist who investigates the cat mind, first carefully observes the behaviour of the animals, then makes inferences as to their "thoughts." He may attempt, in considering such anecdotes as those we have cited, to arrange a situation similar to that of the story and to observe whether other cats of presumed equal intelligence, are capable of performing the feat.

Consider the following story, told by Romanes (40): "My own coachman once had a cat which, certainly without tuition, learnt thus to open a door that led into the stables from a yard, into which looked some windows of the house. Standing at these windows, when the cat did not see me, I have many times witnessed her modus operandi. Walking up to the door with the most matter-of-course air, she used to spring at the half-loop handle, just below the thumb latch. Holding on to the bottom of this half-loop with one forepaw, she then raised the other to the thumb piece and, while depressing the latter, finally, with her hind legs, scratched and pushed the door posts so as to open the door. . . . We can only conclude that the cats in such cases have a very definite idea as to the mechanical properties of a door; they know that to make it open, even when unlatched, it requires to be pushed - a very different thing from trying to imitate any particular action which they may see to be performed for the same purpose by man. The whole psychological process, therefore, implied by the fact of a cat opening a door, is really most complex. First, the animal must have observed that the door is opened by the hand grasping the handle and moving the latch. Next, she must reason, by the logic of feelings' - If a hand can do it, why not a paw?' Then, strongly moved by this idea, she makes the first trial. The steps which follow have not been observed, so we cannot certainly say whether she learns by a succession of trials that depression of the thumb piece constitutes the essential part of the process or, perhaps more probably, that her initial observation supplied her with the idea of clicking the thumb piece. But, however this may be, it is certain that the pushing with the hind feet, after depressing the latch, must be due to adaptive reasoning, unassisted by observation, and only by the concerted action of all her limbs in the performance of a highly complex and most unnatural movement is her final purpose attained" (40).

Consider, also, this story and interpretation of more recent date, originally printed in the "New York Times" and quoted here from the "Cat Journal" for February, 1910: "That the lower animals reason I have stacks of evidence, which have grown greater and greater through twenty years of work in animal psychology, grown from my own observation and that of correspondents in all quarters of the globe. Having formed the habit of psychological observation, there does not go by a day which does not give me some new evidence that the lower animal is essentially simply man; the difference between man and the lower animal lying in the plan, size, and proportions, and not in the material used in construction."

One of the instances on which these pronouncements are based is the story of a cat who was shut up for the night in a shed. She was observed by watchers outside to mew, to scramble up the door, and then "wonderful things happened." The bar between the knobs rattled. Then the knob on the kitchen side of the door partly turned. "What was happening to the knob on the shed side of the door? Pixie was trying to open it."

But Pixie was unsuccessful, and the next night the same phenomena occurred again. "In this action, what had she in view? The turning of the knob, which turns the bolt, which withdraws the latch, which holds the door, which closes the passage between the shed and the kitchen. Since the third night of her imprisonment, Pixie has not touched the knob nor made any fuss. Why? Because she is intelligent enough to know that any effort to get into the kitchen will not attain its end."

Apparently, whether the cat opens the door or fails to do so, her action is interpreted equally well as an example of marvellous intelligence. She seems in both cases to understand, with surprising completeness, the mechanics of door latches.

In order to investigate such occurrences as these, to discover whether they ever happen as described, and whether, if they do, they are correctly interpreted or are common events in cat-life, it is necessary so to arrange events that the behaviour shall occur before the eyes of competent witnesses, prepared to record it, and well versed in the difficult art of separating their theories from their observations. The experiments must be so described that they may be repeated by other independent observers. Many cats must be tested on many occasions. The situation must be such that it is greatly to the cat's advantage to perform a certain feat, or to solve a certain problem. Then one may observe how she goes about it.

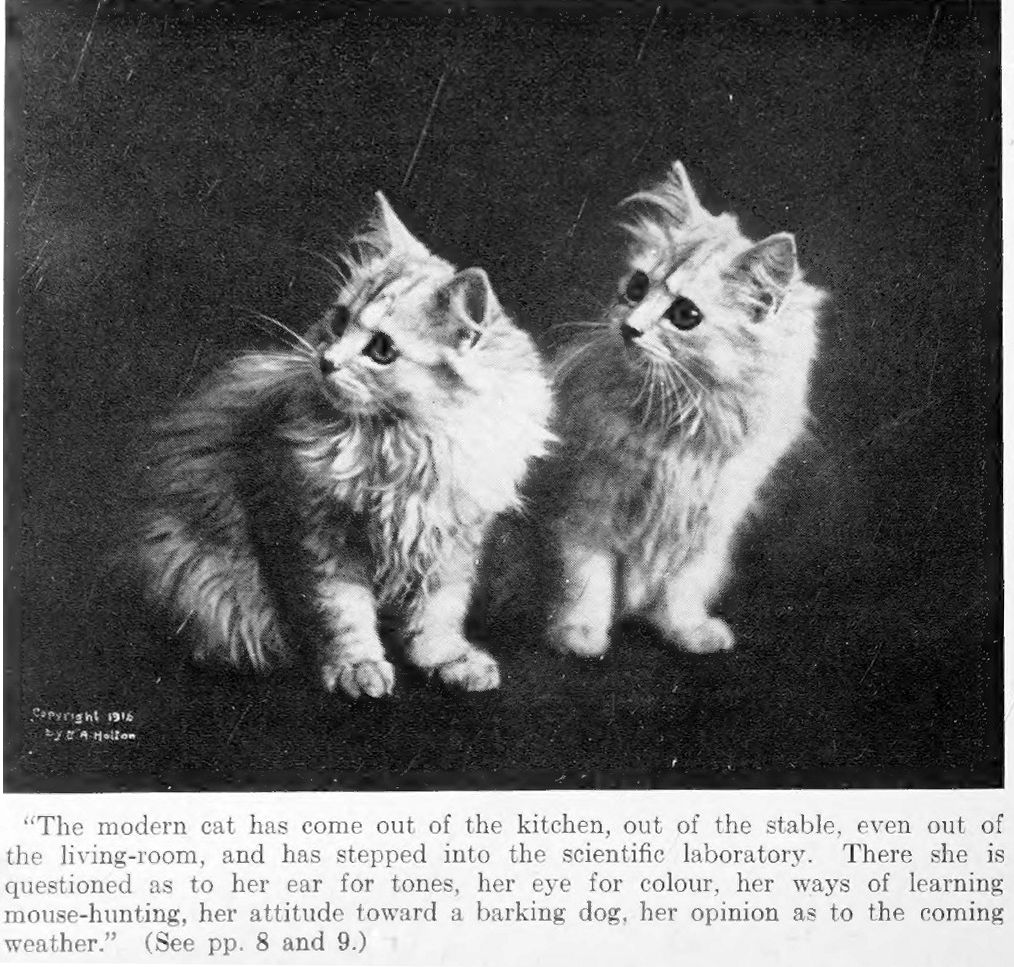

Thorndike in 1898 performed the most famous of animal experiments (52). His apparatus consisted of various boxes with doors which might be opened by animals, by such simple methods as pulling at a loop or cord, pressing on a lever, turning a button, or stepping on a platform. His first subjects were twelve most commonplace cats, who were picked up in the street. A cat who had not yet had her breakfast was put in one of the boxes; a piece of fish was left outside. The experimenter recorded what happened.

Observe the similarity of the situation to that described by Romance and the other story-teller. The cat has a strong motive for escape, she is hungry and food is in sight. The door opens readily by some simple mechanical device. As a matter of fact, the problems presented to these twelve felines were easier than those described by Romanes, since the cat's activity was confined to a relatively small area. When loose in a room she might, in her efforts to escape, investigate windows, floors, walls, as well as the door; in the boxes described by the experimenter the amount of space which she might explore was much less extensive. Observe also the dissimilarity in the situations; in one case a story recounted by an untrained observer, perhaps some months after the event; in the other, we have the careful record of the behaviour of the cat made at the moment it occurred. In the one case, we have only one cat, in the other about a dozen.

What does the cat do in such a situation? If you confined a college professor in similar fashion, locking him in a cell and placing a book just outside which he much desired to read, you would find him, probably, after a few moments of surprise and incredulity, going systematically over the walls, floor, and ceiling of his cell in an effort to discover some device which would permit escape. Failing in his search the first time, he might repeat his performance, being careful to omit no part of the box and paying especial attention to certain areas which might seem to offer clues. You might see him sitting down with his head in his hands, trying to "think out" some answer to his problem. If pencil and paper were available, he might be observed figuring or drawing. If you found such behaviour, you would probably describe it as "rational," as implying "reasoning" and "thought."

Suppose that he discovered the exit, and after permitting him to read a chapter of his book, you put him in again. You would expect that during the first solution he would have "seen through" the problem and would therefore know what button to turn, which latch to unfasten, and so would now escape instantly.

Does the cat, confronted with a similar situation, react in this manner? Does she work systematically, give an appearance of deep thought, or show during a repetition of the experiment that she has profited by her experience? Our anecdotes would lead us to suppose that she would behave much as a man would in similar circumstances.

This is what happens in a typical case. The cat gives evidence of discomfort - often vocal. "It tries to squeeze through any opening; it claws and bites at the bars and wire; it thrusts its paws out through any opening and claws at everything it reaches; it continues its efforts when it strikes anything loose or shaky; it may claw at things within the box. It does not pay very much attention to the food outside, but seems simply to strive instinctively to escape from confinement. The vigour with which it struggles is extraordinary. For eight or ten minutes it will claw and bite and squeeze incessantly" 52).

You have then a picture of a struggling, fighting cat, rather than of a contemplative cat. The animal shows no signs of studying the situation or of proceeding in systematic analysis. Such statements, of course, are merely inferences from behaviour, and the psychologist who based his conclusions wholly on the mere appearance or lack of appearance of "reasoning,' might well be criticized.

But we have further facts. The cat's solution is an accidental one. It happens by chance, during the varied clawing and struggling. In the course of the cat's strenuous activity, her paw accidentally pulls the loop which means release. The door opens, the cat escapes, and is fed. Furthermore, one experience in the box does not teach the animal a method of escape. After she has eaten a little of the fish, the cat is put back. Does she immediately walk to the loop, pull it, so as to obtain release and more fish? Does she realize, as we might say, how she previously obtained her freedom and immediately go through the movements which before brought her satisfaction? Does she think, "When I pulled the loop the door opened," or perhaps, "When I was on that side of the box I escaped," or even, "It was something I did with my right paw?" Does she understand the situation even vaguely? She apparently does none of these things, but merely goes through the same series of reactions: biting, struggling, mewing, varied movements! Again, in the course of battle, she hits the loop by accident and is released. Perhaps the time required for escape is a little shorter on the second occasion, though it may well be a little longer. It looks as though she had profited not at all from her experience.

Yet you find, if you continue the training, if you put her in the box not only once or twice, but a third time, a fourth time, perhaps a twentieth time, that she does learn something. Gradually the period required to escape grows less, gradually the mewing ceases, the biting drops out, the attempts to squeeze between the bars are eliminated. Finally she reaches a point where as soon as she is dropped in the box, without making any other movements, she pulls the loop. She has learned the trick!

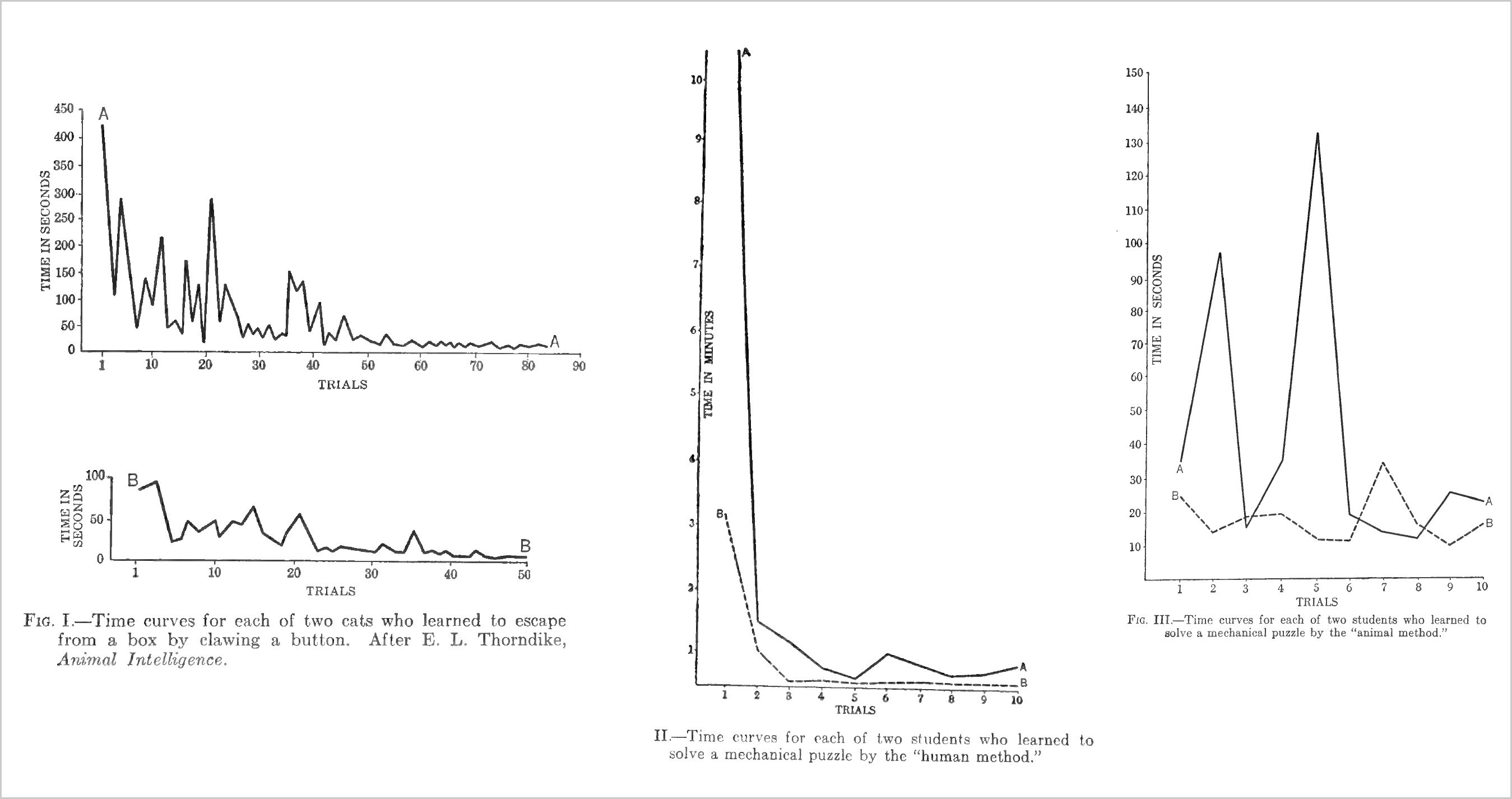

Figure I presents some curves showing the time required by two cats to learn to escape by clawing a button and thus turning it from a vertical to a horizontal position. The height of the line shows the amount of time required by the cat to escape during each of the trials which are represented along the baseline. Figure II shows some curves representing in similar fashion the time required by college students to solve simple mechanical puzzles.

There is one very significant difference between the graphs of the cats and the graphs of the girls. The cat curves are gradual, there are no sudden and sharp descents which affect materially the subsequent course of the curve. The cat required perhaps seven minutes the first time, two minutes the second, five the third, and so forth. She does not change suddenly from five minutes to two seconds and then remain at the low level. The human graphs, however, each display a quick drop, a place where the time required falls sharply from possibly ten minutes to two, after which it varies comparatively little. Such a change is caused usually by the individual suddenly gaining "insight" into the situation, suddenly understanding what is to be done. Then she does it immediately without the fumbling about previously necessary. These evidences of the functioning of ideas or notions about the problem are entirely lacking in the performance of cats.

If you had observed the cat only on the final occasion, you might be moved to marvel as Romanes did at the wonders of animal reasoning powers and to make all sorts of gratuitous assumptions regarding the cat's understanding of mechanical contrivances and the complexity of her ideas. You might say, "See, she understands that pulling the loop will open the door." Yet the cat understands nothing, she does not see through the situation. All that has happened is that the tendency to claw the loop has been strengthened through repetition and through the fact that it has brought release and food, whereas the tendencies to make those movements of biting, mewing, struggling, which brought only continued discomfort, gradually disappeared. The cat learns to escape from a box much as a child learns to button his coat. He does not think, "I will hold the button thus and push it thus." Instead, he struggles with it, twists it first this way, then the other. After several experiences with buttons, he learns to operate them immediately. That method of holding the button is retained which has brought him satisfaction. Those methods of handling have been eliminated which were awkward, uncomfortable, unavailing. He probably thought little about the matter other than to be pleased at his final achievement.

Such learning contrasts with that of our college professor who, having opened the door once, knew immediately, on the second occasion, which movements to make; or with that of the man who is trying to guess the solution of a riddle and who, having guessed it once, is immediately able to give the answer if you propound it to him a second time; or with that of the college students who saw through the puzzle. The cat's behaviour in learning to operate a mechanical contrivance such as we have described, differs from that which the average man describes as "reasoning out a problem," in that it typically involves varied activity of the muscles rather than contemplation, accidental rather than planned success and learning which involves the gradual disappearance of useless movements rather than sudden insight.

As examples of the kind of things which cats can learn readily, we may give the following data. All the cats who were tried in boxes that opened by pulling a loop which hung down the front of the box or one that hung down the back, or by pulling a string within the box or a string outside, or by pressure on a lever, were successful in learning to escape. Four out of five cats failed when the string must be pulled in just one direction, five out of eight when not only must a thumb-latch be opened, but the door pushed in order to escape, two out of five when two separate acts were required for release (pulling a loop and knocking down a board), and two out of five also when three acts were required (depressing a platform, pulling a string, and pushing a bar). Some cats were permitted to escape as soon as they had licked themselves, others as soon as they had scratched themselves. Again they were capable, after a number of trials, of learning to bite or scratch very soon after they had been placed in the box.

Perhaps these simple experiments considered in connection with our discussion of scientific precautions will help to explain the cat stories cited in the preceding chapter. We may criticize either the accuracy of the description or the adequacy of the interpretation of these tales. We feel no hesitation in doubting the facts in the legend of the cat who vanished up the chimney saying, "Then I am the King of the cats," or in the story of the discovery of the cat language, or of the marvellous case of telepathy between woman and cat.

Similarly, we may be led to doubt the story of the kitten who was such a perfect timepiece that she not only remembered the hours when medicine was to be given, but was "never five minutes wrong." Perhaps once or twice (induced by some slight restless movement on her master's part) she chanced to come to the nurse at the proper moment and her enthusiastic owner, who was ill at the time, in recalling the incident, believed that she acted with clocklike regularity. Or perhaps she did come many times, but always in response to some signal given, possibly unconsciously, by her master or the nurse.

We may, if we care to, admit the facts in the other stories and still doubt the explanations. The cat who is alleged to have accepted an apology probably just happened to lift her head at the right time, the cat who looked at the fire and mewed when she was cold probably mewed and looked at the fire on many other mornings when she was not cold, and the fire was not needed. There is no reason for assuming that three cats simultaneously chased a squirrel, were "plotting the downfall of their enemy," or that a cat who reacted differently to two kinds of rabbits was capable of "zoological discrimination," or that putting out fire by jumping in the water implies anything more than an accidental vigorous reaction to a most annoying stimulus. The behaviour of the cat who, during the "philosophic experiment," placed her paw over the hole when the air was drawn, may have been due either to accident or to the mechanical action of the suction pump. One notes that when air was forced in, the paw, no longer drawn to the hole, was removed. Preferring the simplest explanation, we need not assume "wonderful sagacity" or "penetration." The stories of the cats who ceased their efforts to catch birds or to open doors when such attempts were unsuccessful, the tales of the cats who learned to pull wires, open doors or beg, when such feats brought them food, petting, or release from confinement, are all quite readily explained as cases of gradual learning, of the elimination of some movements, the strengthening of others.

We have emphasized throughout the chapter the difference between the way in which cats learn and the way in which a man solves a similar problem. The man thinks, the cat scrambles. But that is not the whole story. One should not leave the reader with the impression that human learning is always of an entirely different kind from cat learning. There are similarities as well as differences.

Suppose that your college professor, instead of being locked in a cell, was thrown into the college swimming pool. Suppose that he had not "gone swimming" since he was a boy. You would not find him sitting down and thinking, but instead, making countless "random" movements. Some of them would succeed, some would fail. Those which tended to keep his feet in the air and his head in the water would disappear. Those which had the effect of keeping his nose above the surface would tend to be repeated. This might happen without his thinking about the matter at all. He might not say to himself, "If I wave my arms thus, I feel easier," or "Lifting the feet too high has an unfortunate effect." He might merely react, continue the satisfying and discontinue the unsatisfactory responses. The next time you threw him in he would probably still flounder, but perhaps not quite so much. The next time still less. If you continued the treatment for a sufficiently long period, he might learn to swim off gracefully as soon as he had struck the water.

The curves on page 51 were presented to a class of students in comparative psychology who had heard a discussion of the various methods of learning employed by different species. They were asked to guess which animals were represented by the graphs. Various individuals suggested monkeys, cats, dogs, chickens, pigs and horses. No one in the class guessed that they were really pictures of a certain learning process in college students!

They show the time required by various students to solve difficult mechanical puzzles, of the kind which, try as they would, they could not "see through." The puzzle required that one separate two pieces of metal. In the course of twisting and turning suddenly the two pieces seemed to fall apart. The second trial was often no better than the first, the third little better than either of these, for the student though she had by chance operated the mechanism which solved the puzzle had no idea which of her movements were effective and which were ineffective. She must try again, and only gradually did useless moves drop out. In this case her learning was much like that of the cat's; it did not come mainly through an understanding of the situation but through trial and chance success.

Conclusions reached by the experimental method differ then from those arrived at by the compiling of anecdotes. In the latter case the cat is credited with a method of learning similar to that of man at his best. She is said to solve problems by thinking out their solutions. Experiments demonstrate, however, that the cat is incapable, within the limits of the investigations, of employing this method, but that she uses instead man's second best procedure, hit-or-miss varied struggling, guided by accidental solution.

CHAPTER IV - THE CAT COMPARED WITH OTHER ANIMALS

Cats I loathe, who, sleek and fat,

Shiver at a Norway rat.

Rough and hardy, bold and free,

Be the cat that's made for me,

He whose nervous paw can take

My lady's lapdog by the neck,

With furious hiss attack the hen,

And snatch a chicken from the pen.

- Dr. Erasmus Darwin (37).

Believing that the experimental method is superior in accuracy to the method of anecdote, we may ask the comparative psychologist to tell us not only what feats cats can learn and how that acquisition takes place, but also, if he can, how cats compare in ability with other animals. We have seen that human methods of learning frequently, though not always, resemble cat methods of learning. Do chickens and monkeys proceed in similar ways? The dog is commonly described as being more intelligent than the cat. Is this true? How does the cat compare in speed of learning or acuteness with her ancient enemies, the mouse or rat, or with the raccoon, or the horse?

The investigations which make possible a comparison of various species have a more important function. They attempt once more to demonstrate whether the cat or other animals show evidence of the possession of ideas, of learning by thinking rather than learning by eliminating useless movements. The college professor who has been thrown in the swimming pool will be able to recall his experience, to call up mentally a picture of the pool, perhaps he will hear - again mentally - the sound of the splash, perhaps he will feel, when he is telling the story, his own struggling movements. He will at least be capable of thinking in some fashion or other about the event which is not now present. Does the cat have a similar mental image of the box from which she escaped, of the loop which she pulled, or a similar thought about her experience? When temporarily absent from her nest in the wood- shed does she carry about with her a mental image of five grey kittens snuggled together in the straw or seem to hear their faint cries? Does she anticipate her adversary, the neighbour's cat, and, in her absence, see her as large, snarling, striped, with protruding claws, or does she meditate on plans of attack?

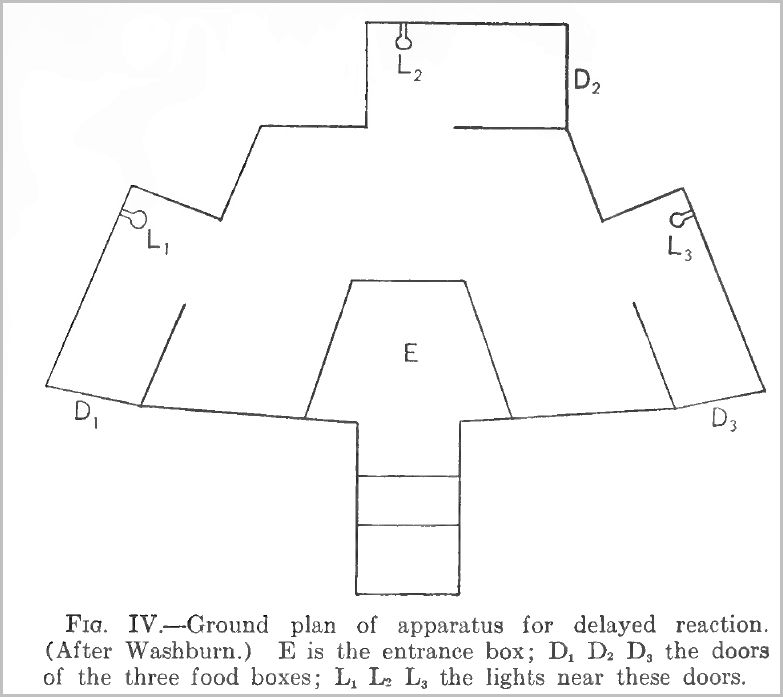

We have seen that in learning to solve the problems described in the last chapter, the cat gives no evidence of proceeding by means of thoughts about the situation, ideas, or mental pictures. Several other ingenious experiments have been devised to test whether animals have (or use) memory ideas. Of these, five bearing especially on the problem of the cat mind will be reported here. Thorndike (52) performed the investigations which we have just described, not only on cats but also on dogs, chickens and monkeys. Another observer (Shepherd) (44) compared the ability of monkeys, dogs, and cats in what he called "Adaptive Intelligence." Hamilton (20) contrasted the reaction to a simple apparatus of a normal man, a defective man, five normal boys, one defective boy, one infant, five monkeys, sixteen dogs, seven cats and one horse! The ability to delay reaction has been studied by a number of investigators, including Hunter (24), Yarborough (67), Walton (56), and Cowan (12), in the case of cats, dogs, raccoons, rats and children. Hobhouse (22) who tested not only his cat, Tim, but a dog, Jack, two elephants (Sally and Lily) and Billy the otter, failed to make accurate time records, and varied his procedure so much from animal to animal that no accurate comparison of species is possible from his experiment.

Thorndike (52) tried three dogs in boxes similar to those which he used with cats. The dogs were very much less vigorous in their struggles than the cats, they gave up sooner, seemed to pay attention to the food rather than to the process of escape. Their bodily structure is, of course, very unlike that of the cats and in this case there was a difference in motive too, for the dogs were not nearly so hungry; all of which makes a comparison of the species very difficult. Thorndike says, however, that it is his opinion that dogs are "more generally intelligent."

It was apparent that chicks were inferior to both dogs and cats in speed of learning simple performances and in the difficulty of the tasks which they could learn, and on the other hand, that monkeys were decidedly superior to all these animals. The monkeys not only learned to operate more complex mechanisms with greater speed, but employed a superior method of acquisition. After a successful operation of a mechanism they were much more likely, upon being tried again, to perform the correct movement immediately than were the cats. The curves for the cats showed, as we have seen, a process of slow learning by a "gradual elimination of unsuccessful movements, and a gradual reinforcement of the successful ones"; but the monkey curves showed a "process of sudden acquisition by a rapid, often apparently instantaneous abandonment of the unsuccessful movements and a selection of the appropriate one which rivals in suddenness the selection made by human beings in similar performances." (52) One might say the monkeys appeared to understand, to have some idea of the movement they were to make. The monkey seems "even, in his general random play, to go here and there, pick up this, examine the other, etc., more from having the idea strike him than from feeling like doing it. He seems more like a man at the breakfast table than like a man in a fight." (52)

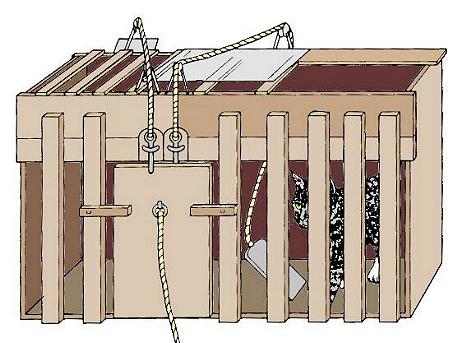

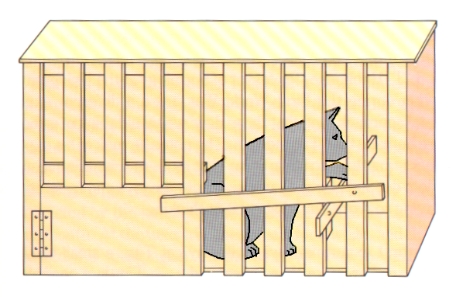

The monkey in these experiments then often shows evidence of the possession of ideas. In an investigation by Shepherd (44) we get a further notion of the kind of feats which monkeys readily perform, and of which cats and dogs, if the experiment is conclusive, are incapable.

A monkey was confined in a cage. A piece of banana hung by a bit of string about twelve inches away from the cage beyond the reach of the animal. Thrust through the banana was a thin piece of wood which could be grasped by the monkey and the food thus brought in. Ten of eleven monkeys confronted by this situation immediately grasped the stick and secured the food. They did not hesitate, they did not first try to reach the food and in "fumbling about" accidentally hit the stick and so grasp it. They merely seized it and used it, possibly somewhat as we would use a spoon on which a piece of food had been placed or the stick which bears the lollipop. The monkeys were all able, furthermore, to secure food by pressing a lever and to pull in a bucket which had been attached to the end of a string.

Three dogs and two cats were tried with a similar stick thrust through a piece of meat. All five failed utterly! The situation was possibly made easier for the cats than for the monkeys, since the stick which was run through the piece of meat instead of hanging outside projected into the cage. All the cats needed to do in order to obtain their food was to claw in the stick, but they paid no attention to the stick. They scrambled madly and excitedly about the side of the cage. They failed similarly in the lever experiment.

Possibly we may explain the greater ability of the monkeys in these experiments as due to their superior sensory and motor equipment. Monkeys can see much more clearly than can cats and dogs, they depend more on vision; furthermore, they are much more adept in using their paws, which are structurally quite different from those of the former animals. It may be that the monkey merely perceives the conditions more clearly and is also more adequate to deal with them. Or it may be that superior mental endowment enables him to understand the situation, to adapt to it in a way in which the cat does not.