LIFE IN THE COUNTRYSIDE and "Farms and Chateaux" Combined

EXTRAORDINARY ISSUE - THE PERFECT DOG AND CAT VETERINARIAN.

Practical review above all, Published under the direction of Mr. Albert Maumené.

Subscription: 6 Nos: FRANCE: 25 Fr. Postal union: 32 Fr.

RADIOSCOPIC EXAMINATION OF A DOG. The installation comprises a strong coil transforming the local current into a current of 5,000 volts and an X-ray table under which is placed the bulb producing X-rays. The veterinarian, here using a "supplementary lens" with a fluorescent screen, observes the abdominal cavity of a Dog which has ingested a foreign body. (Widow Malvezin Co.)

TWO IMPORTANT KENNELS FOR HUNTING DOGS. 1. Installation comprising a series of fully demountable wooden dwellings, each with a mesh-screened enclosed courtyard (Domaine des Vaulx-de-Cernay). 2. This brick-built version also includes a row of exercise yards delimited by a small wall.

PERFECTLY SET UP MODERN KENNEL for Borzois. The kennels, entirely in masonry, are topped by a terrace to which the dogs have access. The kennel itself and the vast exercise courtyard are enclosed by a metal fence with a sill.

SMALL KENNEL for some individuals installed in a farmyard. This construction is divided into two compartments, each communicating with a small mesh-screened enclosed courtyard.

MAINTENANCE OF THE KENNEL FLOOR. If the exercise yard is made of dirt, cover it with a layer of river sand, and renew this once or twice a month.

TO CARE FOR AND CURE DOGS AND CATS

This Volume Teaches you in the Text and Shows you Using Images:

WHY, this Manual of Hygiene, Medicine and Small Canine and Feline Surgery will make you the valued helper of the Veterinarian by teaching you to discern and detect specific benign or serious conditions.

HOW to ensure the hygiene of stock, housing and food in order to prevent epidemics and diseases of all kinds which could decimate the Kennel.

HOW, by knowing the symptoms and lesions, to treat your sick or injured animals, to give them first aid while waiting for the Veterinarian to arrive.

HOW to treat, care for and cure Dogs and Cats with intelligence and punctuality, by applying the Veterinarian’s prescriptions.

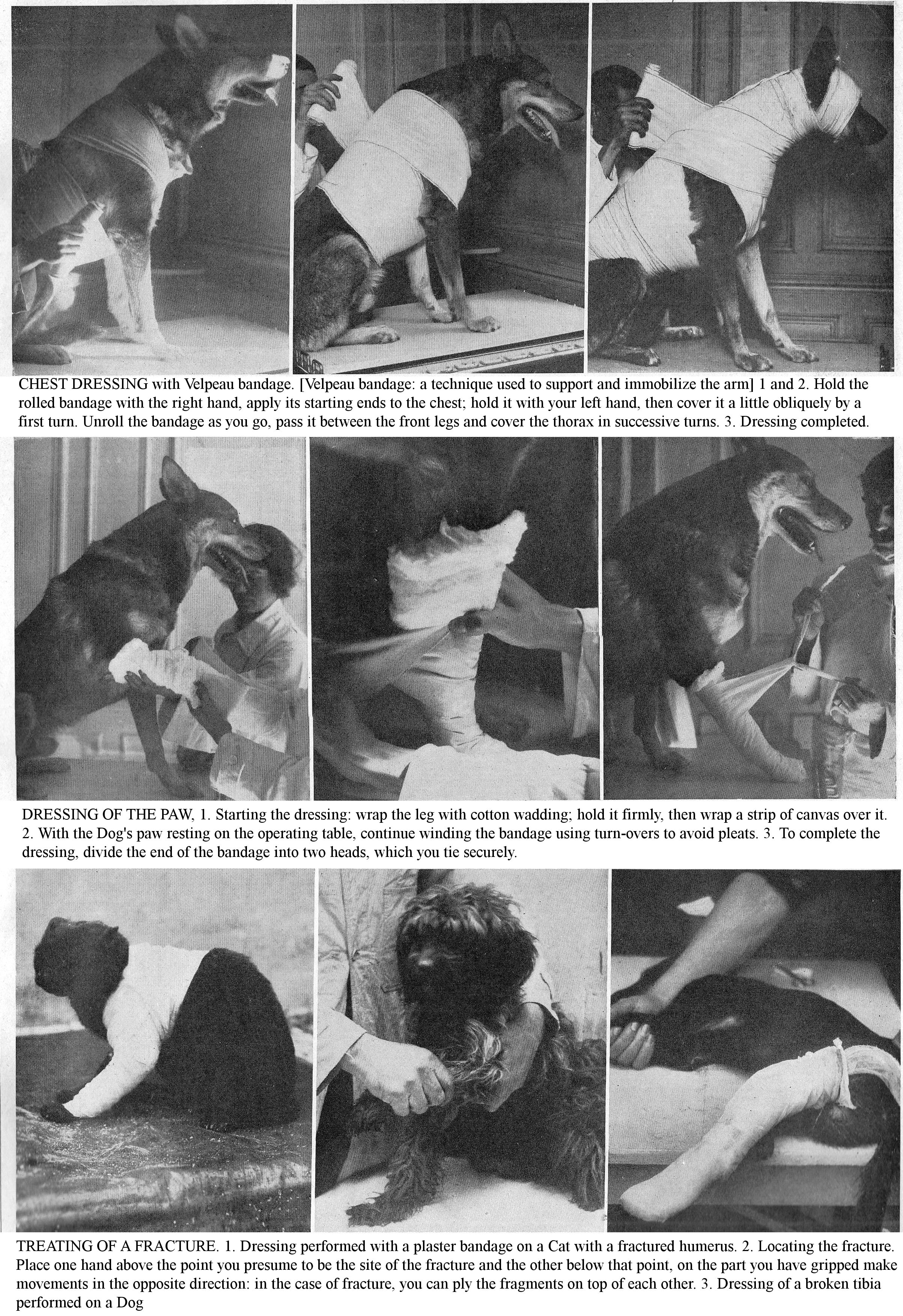

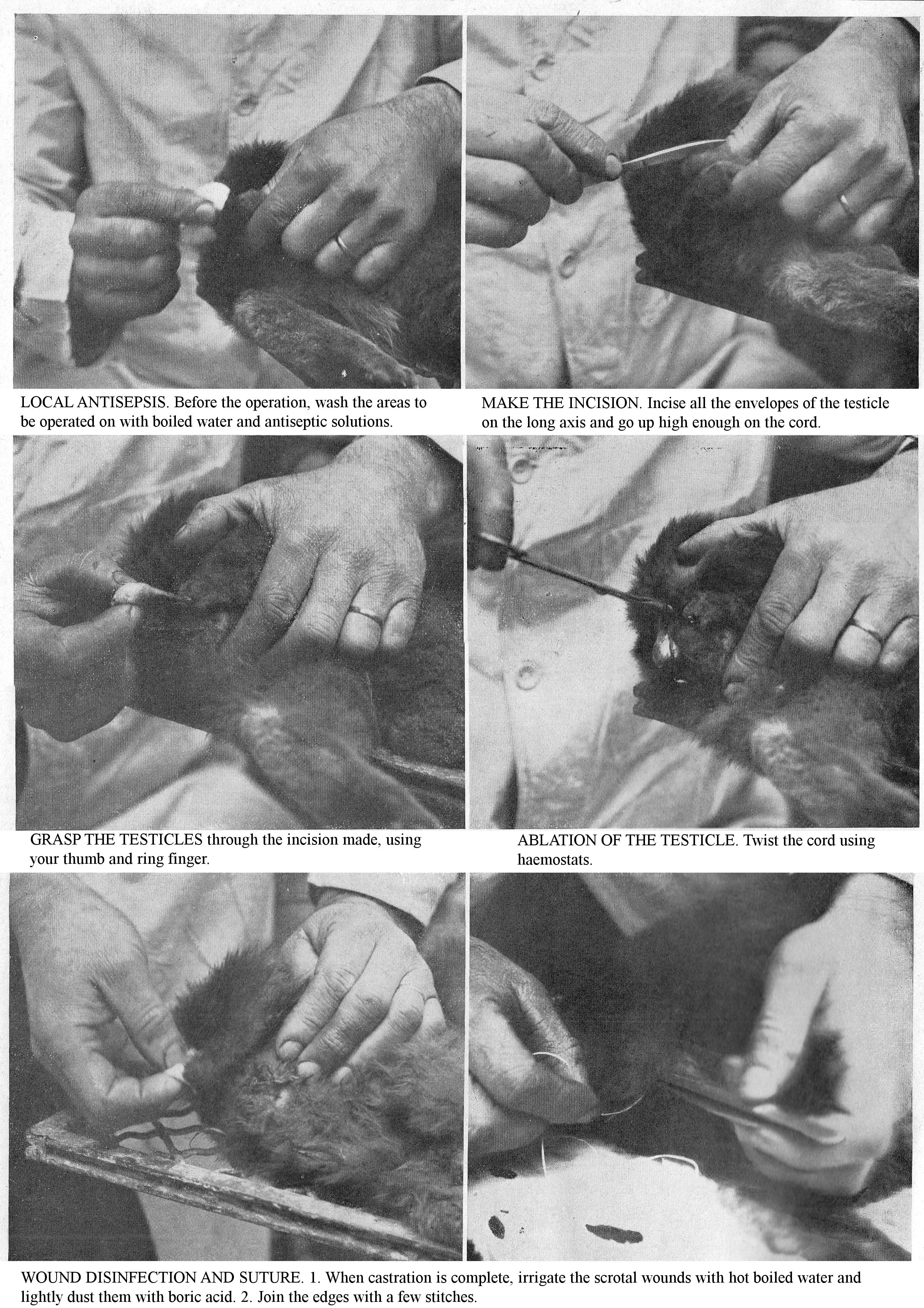

HOW to carry out small operations in the event of accidents of any kind, how to assist the Veterinarian, how to apply dressings, avoid cases of infection and hasten Healing.

THE PERFECT VETERINARIAN is the Vet himself, I wrote at the top of the presentation of "The Perfect Vet of the Courtyard." It is the same for everything concerning Ailments and Hygiene of Dogs and Cats. Do not try to be a substitute for the practitioner, but be the collaborator he needs by relating remarks of any kind that you may have noted, symptoms you have observed and that you need to look out for, the course of the illness, and, above all, strictly observe his prescriptions, follow his advice on hygiene measures, in the event of an epidemic, the treatment of sick individuals and prevention of spread to others.

While an ignorant person neglects to follow the given advice to the letter, because he often and without reason considers it useless, you, on the contrary, after reading this volume, will not omit anything, because you will know the importance of it. No veterinarian mindful of his task, rather than inflating his bills by the multiplication of visits and surgical interventions, does not prefer to be in the presence of an enlightened person, likely to assist him effectively, rather than some layman who is unable to comprehend the advisability of his prescriptions.

Certainly, I am aware that a few very rare and narrow-minded Vets, view this volume as a competitor; while, on the contrary, their more broad-minded and progressive colleagues view it differently. This is why valuable and quality practitioners have assisted in the preparation of this manual. They understand and realise that a work which exposes why and how to identify Canine and Feline Ailments in order to treat them better, like the preceding Volume and like those which will follow, are accessories of their profession.

Our collaborator Mr. Ed. Curot, veterinarian, in charge of preparing this volume, naturally tried to limit the descriptions of ailments to those most frequently observed in kennels. It would make your task more difficult if you were told about Ailments that are quite rarely seen or that specialists are still studying. However, he had to mention ailments that appear rather rarely: this is the case for rabies, where hardly any cases have been seen for over 2 years, as administrative measures have been observed.

The Ailments, Accidents, etc., are examined in their logical order for each case and, according to the nature of the Condition, the author describes it in a few words, follows the process, reviews in turn everything concerning the Etiology, Symptoms, Wounds, Diagnosis, Prognosis, Prophylaxis (preventive treatment), Curative Treatment, surgical intervention, when necessary, etc. Note that we have not repeated the conditions and accidents common to Cats and Dogs to avoid repetitions, but it has always been specified when such a condition is common to Dogs and Cats.

By pointing out the symptoms of Diseases, our goal is not to invite you to treat them yourself, but to show you how delicate, complex and difficult it is often to establish a correct Diagnosis, which would lead directly to effective treatment and prophylactic measures. By knowing and observing the Symptoms in a methodical way, you can often detect a serious condition which you had not otherwise paid attention to, and you can provide the Veterinarian with the essential elements for diagnosis.

In urgent cases, while waiting for the practitioner to arrive, the recommended treatments avoid the need to resort to using empirical measures (measures based on observation), so numerous in Canine and Feline Therapeutics, which are very often harmful and increase the severity of the prognosis. As well as noting the bad treatments, you will always find, if not the absolute remedy, at least the most appropriate treatment, with formulas of drugs for internal and external use. Obviously, drug doses are mostly given as a basic indication, because dosage often varies depending on Age, Race, Size and the individual subject and this is, essentially, the responsibility of the Veterinarian, to avoid serious accidents.

We explain at length the prophylactic measures in the field of hygiene and food that will help you reduce the frequency of internal diseases. Prophylaxis of contagious diseases (isolation, disinfection, vaccination, etc.), when judiciously applied, allow you to avoid epidemic outbreaks which all too often decimate breeding kennels and catteries.

In such a work, however, substituting scientific data for empirical data is often a rash attempt because, when the latter is badly applied due to lack of technical knowledge, they may be more dangerous than the former by assuming a pseudo-scientific character. Avoid this pitfall, the consequences of which (increased mortality, spread of contagious diseases) would be very serious, by calling your Veterinarian at start of an illness.

Our collaborator Mr. Ed. Curot, author of several important works in Veterinary Medicine, has tried to follow the guidelines and scheme of this Journal, by expanding on and substituting practical advice in place of considerations and empty and irrelevant sentences.

Images appropriate to the subject play an important role in this valuable practical work. We have used illustrations extensively in this Volume: photographs show you the characteristics of some ailments; other show characteristics, lesions and attitudes of sick subjects; many show you hygienic installations, expand on methods of treatment, administering drugs, surgical interventions, dressings, bandages, hygiene and grooming measures, etc., by presenting to you all the successive and logical phases, the whole process of carrying out the tasks which objectively informs you and engraves the subject forever in your memory. In this work, the photographs complete the various chapters and are so numerous that there are ten times as many as can be found in the most famous veterinary volumes.

Many of the original photographs were taken at the National Veterinary School of Alfort; others in the clinics and veterinary surgeries of J. Malvezin and J. Taskin.

Always at the forefront of progress, we wanted to encourage you to find new things that you looked for in vain elsewhere; we have, in fact, included in this Volume excellent radiology illustrations (fluoroscopy, radiography, radiotherapy). Radiology has a large role in the diagnosis and treatment of ailments in Dogs and Cats; so you should not be ignorant of what to expect from it. You will appreciate the synthetic radiography of Dr. André Lucy, radiologist at Hôtel-Dieu; another very remarkable one from U.S.A. doctor of veterinary medicine and radiologist, Jacques Tashin, as well as his special radiology facilities for small animals, and those of veterinarian J. Malvezin.

I am very grateful to these collaborators for supporting our efforts, for their interest and for the part they took in preparing this Volume, which I am convinced you will find a veritable Manual of Hygiene, Medicine and Small Canine and Feline Surgery, the Guide and the Advisor you have been waiting for.

Albert MAUMENE.

HYGIENE OF HOUSING AND SUBJECTS

A COMFORTABLE HOME WHOSE CLEANLINESS IS CONSTANTLY ENSURED AND PHYSICAL CARE IS THE BEST GUARANTEE OF A STATE OF GOOD HEALTH IN DOGS AND CATS.

Many ailments would be avoided if Dogs and Cats were provided with all the hygienic measures required by their breeding. Therefore we will first draw your attention to this point.

HOUSING HYGIENE.

Remember that lack of ventilation, damp and cold temperature in the kennels, the presence of drafts, the poor maintenance of litter, and the non-disinfection of premises, constitute the most frequent etiological causes of diseases; also, you cannot attach too much importance to the installation and perfect hygiene of your Kennel. It is through ignoring the importance of these issues that many farms, despite the animals’ lofty origin and a rational diet, are decimated by high mortality which often negates the breeders’ efforts.

HEALTHY HOUSING. The home of Dogs is, depending on the case, a Hutch or Kennel; all too often the Dog is housed in unsanitary conditions and suffers the adverse effects of cold and damp. Kennels are not recommended for all breeds. Miniature Dogs especially, when their births occur during winter, should be reared in apartments, up to the age of 5 or 6 months.

Here we consider the establishment of the Kennel from the point of view of hygiene; everything concerning technical questions (construction, fitting out of kennels, fixed or removable, enclosures, annexes, etc.) having already been dealt with (1). The Kennel needs air, light and space, a hygienic trinity, which directly affects the health of your subjects. When setting up your Kennel, do not sacrifice hygiene for luxury. Build it in a high place, surrounded by trees (pines, fir trees preferably) with loose and dry soil, exposed to the sun, sheltered from cold winds, with doors and windows facing east, south or west, depending on country and altitude. Give preference to a South-East orientation, which offers the maximum benefit, as your subjects, while enjoying the rising sun, are sheltered from freezing winds coming from the North.

(1) Vie à la Campagne: Chiens de service, Ëlevage et Dressage lucratifs (242 grav. Prix: 6 fr.). (Country life: Service Dogs: Lucrative Breeding and Training (242 engravings. Price: 6 fr.).

Ventilation, one of the most important points in Kennel hygiene, exerts a variable action on the inhabitants according to the degree of atmospheric purity. Depletion of the air, apart from having a depressive action on the body, promotes contagion in the event of any outbreak. The atmosphere is renewed by means of natural ventilation (openings, windows, fireplaces, etc.).

While ventilation is a physiological necessity, avoid over-ventilation which would lower the inside temperature beyond the degree compatible with the conservation of animal heat. Puppies are extremely sensitive to cold, their health means avoiding drafts skimming the ground; design the exposure and arrangement of openings to achieve this.

The dampness of the air in the kennels is one of the worst conditions for the health of young animals; it chills them more than a lower temperature in dry air, and predisposes them to rheumatism and rickets. So build your Kennel, or locate the hutches, on dry ground a little above ground level. Heat the Kennel during severe seasons, when you require great expenditure of strength, for pack dogs for example. The kennel of a medium-sized dog should be 1 metre in height and length, and 75 cm wide; do not exceed these dimensions, indeed, if a kennel is to be sufficiently ventilated, it should not be too spacious, as it becomes cold. For economy, use strong barrels, preferably those that contained petroleum oils because, due to their antiparasitic action, they repel the pests that commonly infest kennels.

For hygiene, establish the Kennel double-walled, empty wooden Kennel in double-walled wood with the space filled with sawdust. Cover everything with roofing felt; cement the ground; ventilate it through fairly high openings and fit it with benches. Arrange the beds around the perimeter of the area, except near the door; raise them 30 or 40 cm. above the ground. Avoid the Dogs getting their claws caught in the gaps by a grooved and jointed plank construction. Leave a border of 7 to 8 cm. to hold the straw and, on the opposite side, have a hinge to lift the sleeping benches for cleaning.

Complete this layout with a courtyard of concrete, brick or even asphalt which allows effective disinfection; draw a few markers that you foresee to be useful. Surround the courtyards with railings so that the Dog is not always tempted to jump up to see the horizon, a position that can distort the hindquarters.

Experience shows that, despite strict hygiene, gatherings of dogs are frequently centres of epizootic outbreaks, a consequence of numerous changes due to purchases, exchanges, trips to competitions, etc. For these various reasons, a removable Kennel is preferable to a fixed kennel, as it allows easy disinfection and immediate removal.

Plan for sick dogs under observation, sled dogs, bitches with puppies, and other special accommodations; arrange these as comfortably as possible, depending on their purpose. In a large Kennel the annexes will include, in addition to the kitchen and attic, an infirmary, a pharmacy, an operating room, and a bathroom with a cement bathtub, showers or water jets. Above all, plan the installation of an isolation room. Put any foreign subject or any animal returning from a competition or trip, in a special room for 15 days to monitor their health status, and apply the same measures if one of your own Dogs shows symptoms of illness: depression, inappetence, digestive or respiratory problems. Keep the isolation room as clean as possible, line the bunks with plenty of straw, constantly renewed; spread sawdust on the floor to allow dry cleaning; its odour repels the parasites that like to infest sick individuals. Disinfect the room frequently and urgently in cases of contagious diseases. By applying these basic hygiene principles, you can anticipate and quickly limit the contagious outbreaks that often decimate Kennels.

Do we need litter; which litter to choose? The role of litter is complex; it must absorb excreta, keep the premises dry, and protect the Dogs from damp and cold. The best litter for Dogs is fern; alternatively, use wheat or rye straw and add a few walnut leaves, the smell of which eliminates parasites. Oat straw is too short and quickly crumbles into dust. If a Dog has developed the bad habit of soiling the straw where he sleeps, dissuade him by putting some soiled litter on the floor of the kennel, and let him lie down on a bare bench. Change the litter at least once a week, more often for Puppies who dislike damp; to this end, lay down a thick layer to preserve them from the cold; put Puppies, at least for the first month, on good hay, and never use peat litter for them because it is very powdery and could block the noses of young animals and cause them to suffocate.

HYGIENE MEASURES. Purchases, exchanges, trips for competitions or for breeding, often require the movement of the subjects. Observe the following hygiene rules: avoid shipping the Dog after a large meal, and especially during hot or cold weather. Have the Dog travel in a special crate or strong basket; attach feeding and drinking troughs inside it; line the bottom with good litter, and double its food ration two days before the expedition in anticipation of post-travel fasting. Secure the top of the crate and provide ventilation with a small metal mesh frame. On arrival, report on the subject's health status, and if it is sick or has died, report this.

Traveling in railway kennels exposes Dogs to drafts and colds due to their lack of hygiene and comfort.

Kennel hygiene. The upkeep of the animals and the cleanliness of their kennels have a marked influence on their state of health. The hygiene of the Kennel includes the absolute cleanliness of the premises, the frequent renewal of the litter placed on the benches, and the grooming and bathing of the residents.

Disinfection, the best preventative of contagious diseases, is most often applied haphazardly. Insufficient disinfection explains the frequency, persistence and spread of contagious outbreaks. However severe it may be, isolation is never perfect and can only be an incomplete preventative measure. In fact it is not sufficient to avoid contagion by rigorous measures, it is also necessary to destroy the germs; disinfection fulfils this goal. However, it is only effective in hygienic premises; its effects are uncertain in the insanitary and badly arranged Kennels.

Do serious cleaning every day as soon as the Dogs have eaten their slop, put them in the exercise run or give them their freedom. While they are away, sweep the floor, rid the Kennel of excrement, then wash it with a brush with plenty of water. Finally sprinkle it with cresylated water to neutralize bad odours. Some breeders are in the habit of dusting the ground with sawdust or ashes to facilitate cleaning; do not use this process as it has the disadvantage of frequently dirtying the fur and sawdust gets into the food. Change the straw or bedding material frequently, especially if you are dealing with animals that have a bad habit of urinating in their kennels. Finally, dismantle and thoroughly clean the removable cabins every month in Winter and every two weeks in Summer. By doing so, you significantly reduce the number of parasites that infest Dogs. Bring your subjects in when the ground is perfectly dry and the water gutter is clean and covered with its grating.

To disinfect the Kennel, brush all the walls of the kennels [niches] with one of the following solutions which have the advantage of not attacking the paint or varnish: cresyl solution at 3% or 4% solution of sublimate at 1 part per thousand; wash the floor with a brush and a boiling solution of soda crystals at 10%, and swill it with cresylated lime milk comprising 10 parts slaked lime, 3 parts cresyl, 100 parts water. Preferably use removable wooden kennels because these are easy to clean thoroughly; rapid singeing or carbonyl disinfection immediately sanitizes them, something impossible with brick or cement boxes. Also disinfect the feeders, brush them, wash them with plenty of water, and leave them for at least twenty-four hours in bright sunlight, weather permitting. Sanitize the litter, stable manure, slurry and excrement with 10% milk of lime and add a quantity equal to that of the material to be disinfected.

ANIMAL HYGIENE.

Grooming, bathing or washing and exercising are valuable means at your fingertips to ensure the health of your animals. Do not neglect these.

PERFORM GROOMING. Grooming is a procedure that rids the skin of the grime and impurities deposited on the body's surface. In in common canine breeds it is all too often considered superfluous, but it meets an imperative need and contributes, to a large extent, to the maintenance of health. Lack of grooming allows the accumulation of epidermal waste, predisposing them to parasitic skin conditions. The skin of a healthy animal living in freedom, unlike one living in the kennel, is generally in a satisfactory state of cleanliness.

ISOLATION AND NURSING ROOM. 1. Small building located close to breeding kennel for the isolation of subjects with contagious diseases. 2. Interior of an infirmary. The parquet is cemented; a central corridor below has a drainage channel for the water.

IMPORTANT FACILITIES for the treatment of sick Dogs and Cats. 1. Interior of a well-arranged veterinary Kennel; a whole series of entirely metal cages are arranged around the room; heated in winter, well lit, ventilated and easy to clean. 2. Exercise pen for hospitalized Asylum Dogs. This park is exposed to the sun and offers several compartments allowing animals to be separated at will. 3. Interior of cat hospital.

TO BATHE YOUR DOGS. 1. Bathroom: this very simple installation, installed in a large breeding kennel of Pyrenean Dogs, has 3 bathtubs and a stove with boiler. 2. A Dog is placed in a bathtub containing lukewarm water at a temperature of 35 Centigrade.

SOAP METHODICALLY. 1. Soap all parts of the body starting with the ears and ending with the tail. Avoid getting water into the ears and eyes. 2. Leave the soapy lather in contact with the skin for a few minutes. 3. Rinse the Dog in a second tub. 4. Then put it in a third tub containing clear, lukewarm water.

WASHING AND DRYING DOGS. 1. How to make a Pekingese Dog take a bath in a washtub. 2. Bathing a Borzoi in a tub: the animal is rinsed by spraying it with clear water from a watering can. 3. Drying a Dog using an electric dryer.

Give a regular daily grooming with a horsehair brush if the hair is long, or with a pig bristle brush if the hair is short. Follow this grooming with a general massage, performed with the free or gloved hand. Regular use of a brush, handled expertly, often makes washing unnecessary; washing removes the oily substance intended to lubricate the skin and hair and to maintain these in the necessary state of suppleness. Use an angled bristle brush for grooming short-haired dogs: terriers, etc.; strong whalebone, quack-grass or wire, half on rubber for long-haired dogs; silky bristles for luxury dogs. Awkwardly directed combs can irritate the skin and damage the coat; use combs with wide teeth and very blunt ends, in black rubber or aluminium. There are curry-combs for rough-haired dogs; dry them well after use. For hygiene reasons, and to prevent the transmission of skin diseases, disinfect these items often.

Grooming Dogs to appear in an exhibition has a few peculiarities: perfect the moulting of the winter hair by removing any dead hair, the fluff that eventually becomes felt, leaving only the young, shiny fur. Proceed with a somewhat stiff quack-grass brush, rubbing in all directions; then carefully use an unknotting comb, either metal or horn. This operation finished, continue with a fine comb, gently pulling out any dead hair. These preparations finished, give a bath, rub the Dog in all directions, and comb it before the fur is completely dry using a special curry comb or a curry-glove.

The hygienic care given to a Cat, due to its normal state of independence, is almost nil. The Cat, by using its tongue, grooms itself automatically; it successively and frequently, licks the various parts of its body for hours on end and its hair presents a shiny and silky appearance due to successive massages. However, perform a light brushing each morning, followed by a light hand massage.

Do not bathe Cats, due to this species’ aversion to water and the respiratory ailments to which they are exposed if they are wet.

BATHS – WASHES

Skin hygiene, apart from grooming, can be achieved by washing and bathing; these can be hygienic or medicinal. The therapeutic effect varies with the temperature of the water and the duration of immersion. Cool water (10 to 15 Centigrade), exerts a tonic action which resonates, by reflex, on other organs, by the reaction it causes on the skin.

Do not use baths before the age of 6 months; give lukewarm baths, around 35 centigrade, monthly in summer, and every two or three months in winter, in a warm room. Take care to stir up the subjects well during the bath, and above all rinse and dry them thoroughly at the end, avoiding any chills and drafts. Only give baths 2 or 3 hours after meals to avoid digestive upsets.

To soap it methodically, place the Dog in a tub containing hot water; soap all parts of the body starting with the ears and ending with the tail. Avoid getting water into the ears or eyes; leave the soapy lather on the skin for 7-8 minutes to give it time to kill fleas or other parasites. Then rinse the Dog in a tub, remove it and put it in a second tub of clear lukewarm water; wipe it down with tea towels, and let it run in a meadow or sandy place where it can lie down without getting dirty. Carry out this procedure carefully; never let a dog that has just been washed lie down in the kennel without first ensuring that it is completely dry. During the cold season, rub the Dog down; wrap it in a woollen blanket; or better, place it in front of a good fire to avoid any organic repercussions due to cooling.

Despite the hygienic effects of baths, do not overuse bath-therapy, especially among delicate breeds; remember that methodical and regular grooming avoids the need for frequent bathing.

Complete the grooming by washing the eyes, ears, nipples, and take special care of the digital region. Wash the eyes every day with a little lukewarm boric water; keep the inside of the ears very clean by washing with soapy water then dry them carefully; by this hygienic practice you will avoid auricular catarrh, a very stubborn affliction. Clean the nipples because, while nursing, Puppies can contract the parasitic diseases from the mother resulting in death or stunted growth: wash the nipples with a sponge soaked in a solution of salicylic acid at 1 part per 1000.

You will read with interest the following articles which have already appeared in Vie à la Campagne: How to choose a hunting dog, no. 230; What You Can Expect From The Gordon Setter, no. 231; The Breton Spaniel, a remarkable hunting dog, no. 237.

ENSURE EXERCISE. Exercise is necessary for the Dogs you want to keep healthy, fit and resilient. It prevents an accumulation of fat between the muscle fibres; it maintains the normal relationships that should exist between the different parts of the musculoskeletal system (bones, muscles, tendons, ligaments, joints); it ensures their regular play to a fair extent. In methodically measured sessions, exercise gradually acts most successfully by increasing respiratory capacity, promoting regular digestive function and it constitutes a preventive treatment for obesity and constipation which are frequently seen in apartment dogs which are kept almost completely inactive. Therefore, the duration of exercise must be in proportion to the Dog’s temperament, age and abilities. Give Service Dogs one hour in the morning on the leash and half an hour in the playground in the evening, releasing them two or three times. Take them for a daily walk in freedom to keep them in good condition; give Hunting Dogs a route of 5 to 6 km but take care that this exercise never take place straight after meals.

To stimulate the Dog, make it run behind a rider or a cyclist, preferably in the morning, especially in summer; the walk and the exercise enclosure are insufficient for service dogs. If you have more than one Dog, take them out together so that they train each other. To get an Apartment Dog to take healthy exercise, give it a rubber ball; he will fetch it, developing a particular eagerness in this game. When returning from a walk, wipe the Dogs dry if they get wet; wash their paws if they are muddy. Then shut the subjects in a kennel lined with dry straw or a cushion, as appropriate.

If the Dogs are kept in a too narrow place, take them for a walk after their meal so that they can frolic and void their wastes; once in a while, in the morning as much as possible, to a meadow, take them along a grassy road, so that they can eat the soft grass, which is the best purgative for them.

BASICS OF RATIONAL DOG FEEDING

UNDER WHAT CONDITIONS TO DISTRIBUTE FOOD, ACCORDING TO THE AGE AND CONDITION OF ANIMALS, TO AVOID NUTRITIONAL DISORDERS AND DISEASES OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM.

The Dog’s diet must be both economical and hygienic. The cost of the daily diet is an important factor which directly depends on part of the envisaged profit; currently, a dog costs more than 400 francs in food per year.

Even more, or in the same way as hygiene, food plays a very big role in breeding; an irrational diet, both in quantity and quality, can cause serious digestive disorders and a predisposition to nutritional diseases (rickets) and in general to all the infectious diseases that often decimate kennels. Morbidity and mortality factors are largely due to food hygiene.

The Dog is a predator, but domestication has made it an omnivore whose diet includes animal and plant material. The terms of this mixed diet, which is a physiological necessity, are imposed by the structure of the dog's digestive system and by the particular conditions in which the animal lives at various times of its existence.

Chewing is very cursory in the Dog; mixing with saliva is minimal and food enters the stomach without undergoing any noticeable changes. The dog's stomach is spacious and its entire surface is covered with a mucous membrane endowed which actively secretes gastric juice. Stomach digestion, quite slow and very powerful, is an important act. In consequence of this long digestion time, and its intermittent nature, hunger returns at long intervals so meals should therefore be infrequent.

The Carnivore’s digestive system has a much smaller capacity than that of herbivores. The intestine, in particular, is significantly shorter and narrower; it is remarkable for its brevity and small volume. Large stomach, short intestine, cursory chewing, superficial mixing with saliva and very powerful gastric digestion are the physiological data which you must take into account in canine dietetics. From the point of view of hygiene, the dog's diet plays a big role: carefully avoid either excess or stinginess.

Common food-related illnesses (dyspepsia, stomach dilation, gastritis, gastroenteritis, etc.) show the importance of diet.

Dyspepsia is most often caused by an irrational, poorly regulated, insufficient or too copious diet. Stomach dilation is seen mainly in naturally voracious adult dogs that are heavily fed and accustomed to only one meal per day. Gastroenteritis and Indigestion are common following repeated ingestion of coarse, irritating, spoiled or toxic foods. Overconsumption of meat causes a predisposition to inflammation, most commonly eczema and auricular catarrh.

Examination of the faeces constitutes the best criterion of the diet used: look for a moulded, homogeneous, dark-coloured stool, with a typical odour, all signs of a well-functioning digestive tract. Prevent fluid faeces, consisting of undigested residue, discoloured or with a red appearance, bloody traces and a foul odour, indicating digestive disorders and incorrect diet.

DAILY DIET. The amount of food to be given to a Dog is not usually determined by any specific rule. Some are overfed, fat, plump, lazy, and predisposed to skin conditions; others, who are sparingly fed, are thin, fussy, physiologically poor, and predisposed to disease or parasitic invasion. Fix the dog's daily diet at about one-fifteenth of its weight; set it to about one-twelfth during the growing period and for those who tire; reduce it to one-twentieth for adults, the elderly, and the sedentary. But take into account that the daily diet is subject to variations depending on the degree of activity of the digestive functions, the constitutional state or the temperament of the animals.

A good diet must, in order to satisfy the creature’s needs, contain the necessary nutritional principles quantitatively and qualitatively, include easily digestible materials palatable to the animals, and have suitable nutritive values. When substituting foodstuffs, generally done for economic purposes, take into account the requirements expressed above, and also be aware that any substitutions must be applied carefully and gradually in order to avoid accidents.

In general, a combination of carefully chosen and complementary products is, in terms of nutrition, the best way to avoid deficiencies and the physiological and economic double wastefulness that can result from a defective make-up of the diet. It should not be too watery, containing more than 75% water; preferably make it up by combining elements of animal and plant origin, as digestible as possible and containing a minimum of cellulose.

Vary the food often to stimulate appetite and digestive functions. Remember that a uniform diet causes food aversion and has a depressive effect on the stomach and intestinal function. In the diet, take into account the importance of ancillary factors, hormones, vitamins: substances still poorly determined but whose absence from the diet can lead to serious deficiency disorders: acute, subacute, and chronic diseases (scurvy, rickets, anaemia, various weaknesses). These are destroyed by the handling of the specialties recommended for dog food and by temperatures above 110 to 120 Centigrade. Also supplement prepared foods with natural and fresh foods, in particular with tubers, roots and vegetables.

Vary the number of meals, their importance to health being considerable, with the age of the animals and the nature of the food. After weaning, give 5 meals; from 2 years old give 2 meals a day: one in the morning, another in the evening, to avoid the ingestion of excessive amounts of food at one time. Never give a heavy meal immediately before or immediately after strenuous exercise. Whenever possible ensure the meals are regular. Give lukewarm food to young dogs, cold or lukewarm food to adults during the winter season.

COMPLEMENTARY FEEDING. A milk diet, however physiological it may be, is no longer sufficient to ensure the rapid and steady development of puppies; achieve nutritional balance by complementary feeding which is really the first stage of weaning. The delicate structure of their digestive organs, their smaller volume, their incomplete development, and the state of secretions, are all health factors that you must take into account during this period.

The use of complementary foods must, therefore, be introduced slowly and progressively; carefully avoid overfeeding which leads to serious digestive disorders. At first it is more of a food substitution than an addition. "Often and a little at a time" is the rule you must observe.

Base the choice of foods on their nutritional value and digestibility; the cereals and pâtés serve as a transition between the milk diet and meat diet and allow a gradual adaptation of the digestive tract to the new diet. In the case of numerous young and towards the 4th or 5th week, the period when breast milk decreases in quantity and quality, make up for this deficit by giving boiled milk at a temperature of 30 to 35 centigrade. At this time, the basis of the diet should be raw and grated mutton, a teaspoonful of oil with a few drops of cod liver oil; soups with rice and vegetables, milk, pepsinated or baby cereal, grated veal bones. Distribute this ration in 5 or 6 meals; with very regular intervals between them, because of the reduced digestive capacity of the subjects.

FEEDING AFTER WEANING. The future of Puppies is ensured by breastfeeding that is sufficient in abundance and in duration, by a weaning conducted without a difficult transition and by an intensive and easily digestible feeding, after this period. After weaning, give milk soup morning and evening and meat soup at noon. Add, in addition, a little raw or cooked meat, grated or cut into small pieces, given as is or after having drizzled with cod liver oil. Do not distribute hot meals, but lukewarm, that is to say at a temperature below 37 °. Thereafter, vary the diet and gradually bring the puppies to the adult diet. Until their full development, give them a mixed easily assimilable diet, but especially meat; promote skeletal growth by adding bone powder, crushed eggshells or a phosphate mix to the mash.

Pay close attention to the health and diet of Puppies to be entered in a competition; partially remove the ration of bread and vegetables, and replace it with a meat diet, rich in proteins, so as to eliminate the fat which gradually clogs the tissues, invades the muscles and masks the animals’ harmonious lines. On the day of the exhibition, give a dozen raw eggs, which, by their reduced volume, ensures sufficient nutrition and prevents a bloated belly.

Feed Kittens separated from their mother with milk, then with breadcrumbs crumbled in milk. Later on, base their diet on soft or raw, boiled liver; if the budget allows it, add some fish. For apartment cats, continue the milk; give as little cooked meat as possible, a daily ration of soft and raw liver being necessary to keep them in good condition.

SPECIAL DIETS. Gestation: During this period the diet must meet the following physiological requirements: avoid abortion, ensure foetal development and promote lactation; it must therefore be easily assimilable and plentiful. Towards the end of the gestation period, give a refreshing diet to facilitate milk yield and avoid the use of artificial breastfeeding.

Parturition. The profound changes in the body produced by childbirth, especially in complicated births, require special nutrition. For 2 or 3 days give Bitches a refreshing diet (a paste of oatmeal flour with milk, plain milk, broths and lean meat, etc.). Do not resume the normal diet until systemic disorders have disappeared; to act otherwise is faulty health care and prejudicial to the health of the mother and young.

Lactation: Apart from individual variation, lactation is largely related to diet; the diet of nursing mothers is even more important because it directly influences the establishment and production of milk and, consequently, the future of the subject. The diet must be easily assimilable and contain the nutrients necessary to ensure the mother’s maintenance and her milk production. Food should also be refreshing, as, apart from its influence on the quantity of milk, it has a positive influence on the health of newborns. During the lactation period, give your Bitch plenty of milk, eggs and meat; the health of her offspring depends on it. Vigorous young will easily withstand weaning. Add lukewarm soups with added vegetables to the diet.

MINERAL DIET. In nature the Dog is a carnivore, but, in the state of domestication it does not exclusively require meat. Feed him a diet that includes both plant and animal matter in roughly equal proportions. More precisely, adopt the following ratio: 40% animal products, 60% plant-based foods. There is no doubt that meat should be included in the dog's diet, but base the proportions on the work he is required to do, the climate, and his age and breed.

Meat: Meat is an essential food for youngsters and those whose bodies are not fully developed. Give a smaller amount to adult dogs, and reduce it still further in old age. Remember that raw meat, being much more nutritious than cooked meat, is particularly advantageous during a period of convalescence, as well as for those suffering from diseases causing poor appetite.

Fresh meat can present dangers: meat from animals affected by parasites, meat whose ingestion can produce symptoms of poisoning, due to the presence of toxins before slaughter or developed afterwards (stale meats, sick meats). Therefore, the quality of the meat is greatly important, and if you notice any signs of spoilage, reject it as unsuitable for consumption. Of all the meats used in the dog's diet, favour horse-meat, it is the only one that does not expose the animals to contracting worms.

Provide all types of butcher's waste - mutton tripe, sheep heads, meat meal, dried meat, supplied by the rendering plants, fish meal – as the high protein content of these by-products will ensure skeletal development in young dogs; use them, moreover, in preparing the broths used for diluting cooked vegetable foods. Also use cretons, the caked residue of melted tallow, because of their high nitrogen content (55%) and fat content (23% - 24%). Also give blood mixed with meal (corn flour, rice, etc.), in the proportion of 100 grammes of blood for 300 to 400 grammes of meal.

Bones are composed of an organic substance, ossein, impregnated with various minerals: phosphates, calcium carbonates, magnesia, etc. Give them to clean and strengthen the teeth as well as to supply the body with the necessary minerals, especially calcium.

Milk, according to its chemical analysis, can be considered a complete and physiological food during infancy: the Puppy gets all the elements necessary for normal growth from it. Eggs, being rich in albumin, and having a high organic phosphorus content (lecithin, vitelline, etc.), constitute a powerful means of completing growth in slow or sick individuals. Offer them diluted in milk; Puppies are very fond of them in this form.

PLANT FOOD. Consider bread made from flour (corn, oats, rye, peas, field beans, etc.) as the basis of dog food and a maintenance food. The total diet (maintenance and output) of a working Dog obliged to expend muscular energy must include bread or vegetable matter and meat.

Distribute the bread as it is, or as a mash made with hot water or broth; mixing it with skimmed milk is recommended. Dogs gladly take bread in the form it is prepared for man; stale bread and breadcrusts are advantageous in the Dog’s diet if they have not deteriorated. The same is true for batches of army biscuits.

Do not feed a dog exclusively on soups, which are always swallowed greedily and, if they are mixed with saliva, will overwork the stomach’s digestion; in addition, this diet is debilitating and does not maintain the condition of the Dogs. Never serve soup hot.

Use pasta and pasta scraps made from wheat flour made for human consumption (noodles, tapioca, semolina, vermicelli, etc.), because of their real health and nutritional value. Include them in the composition of the diet of small breeds. Add them to the milk or cook them in water, with the addition of a little gravy or vegetable broth.

Oilcake is difficult to assimilate, despite the high protein content; Dogs lose weight on this diet. Potatoes, because of their low coefficient of digestibility, 18%, fatten and weigh the Dogs down; only introduce them for 1/4 as a substitute for bread. Distribute root vegetables (carrots, beets) cut into small pieces before cooking; these combat the heating effect of a meat diet. Use vegetables widely despite their low nutritional value, as they increase the appetite for food, provide essential nutritional factors (vitamins) and act as laxatives.

Sugar, chocolate, sweets and pastries, which form the basis of the diet of luxury dogs, are only a problem if you give them in excess.

HEALTHY DRINKS. Drinks are intended to introduce, into the budget, the water necessary for the normal composition of the blood, for the constitution of tissues and for the maintenance of bodily secretions; they are, therefore, greatly important. The lack, excess, or irregularity of drinking water can cause physical disorders.

Distribute water that has all the characteristics of drinking water (colour, clarity, odour, etc.). Do not use water that is muddy, silty, or has organic matter in suspension, as well as water from ponds, ditches, etc. These waters are unsanitary due to the presence of parasites and highly pathogenic germs and are a vehicle for microbial and parasitic diseases. Renew the water often. Avoid soiling the containers with urine or manure, by placing them on a small support fixed at 25 to 30 cm., depending on the size of the Dogs. Occasionally, especially in hot weather, add a small dose of baking soda to the water for 8 to 10 days.

PHARMACY AND ADMINISTRATION OF MEDICINES

WHY YOU SHOULD NOT IGNORE THE PURPOSE A FORMULA OR SPECIALTY IS PRESCRIBED FOR, AND HOW TO ENSURE THE PERFECT APPLICATION.

Before starting the study and description of diseases of Dogs and Cats, it is essential that you know the basics of dosage, the composition of an emergency pharmacy and the methods of administering drugs to these animals.

PRINCIPLES OF DOSAGE. The dosage, that is to say the indication of doses of drugs in dogs, is very variable; the great variation, due to the variation of height and weight, are indeed represented by the numbers from 1 to 10. Use only the doses indicated by your veterinarian, because the therapeutic or toxic effect of drugs measurably varies according to age, individuality, size, breed, severity of symptoms observed, etc. Therefore, we point out the formulas purely for documentary purposes; the minimum and maximum doses indicated correspond to small and large breed dogs.

The dosage of the cat corresponds to approximately half of the doses applied to small dog breeds; remember this therapeutic peculiarity, because, during the course of our study, to avoid unnecessary repetitions, we do not indicate special doses for felines, except for toxic drugs.

Evaluation of tablespoons, dessert-spoons, coffee-spoons: for liquids whose specific weight is equal or approximate to pure water, a tablespoon or mouthful contains about 15 gr.; a dessert spoonful, about 10 gr .; a teaspoonful of coffee, about 5 gr.

The number of drops contained in one gram of the drugs most often prescribed are: Acid hydrochloride, 21 drops; Sulphuric acid, 26 drops; Ammonia, 22 drops; Paregoric elixir, 53 drops; Sydenham's Laudanum, 43 drops; Ether, 90 drops; Fowler's liqueur, 34 drops; Iron perchloride, 20 drops; Tincture of aconite, 53 drops; Tincture of belladonna, 53 drops; Foxglove tincture, 57 drops; Tincture of iodine, 61 drops. A pinch of powder equal to 1 to 2 gr.

KENNEL PHARMACY. Organize an emergency pharmacy so that you can ward off minor ailments and, in severe cases, give first aid, while waiting for the veterinarian to intervene.

Keep the following usual medications in reserve:

Purgatives: Castor oil, Buckthorn syrup; Internal astringents: Bismuth sub-nitrate, Tannin; Gastrointestinal antiseptics: Calomel, Salol, Benzonaphthol, Bismuth salicylate. Antipyretics: Quinine. Tonics: Tincture of cinchona, cola, gentian. Stimulants: Ammonia acetate, Caffeine, Ether, Camphor oil. Haemostatic: Iron perchloride. Dewormers: Kamala powder, areca nut, Semen contra. Antiseptics: Potassium permanganate, Carbolic acid, Sublimate, Cresyl, Hydrogen peroxide, Tincture of iodine. Also put together a kit containing the essential instruments: a scalpel; a pair of dismantlable scissors, a suturing needle, a lancet, a fluted probe, a Pravaz syringe, ordinary forceps, forceps, haemostatic tourniquets, Florence horsehair or catgut for the sutures, a packet of absorbent wadding, bandages.

The timing of administration influences the physiological and therapeutic effect of drugs. Observe the following indications. Acids: if the main purpose of ingestion is to activate digestion, give these during or at the end of meals. Alkalis: To stimulate gastric juice, give them before or during meals, or 2 hours after meals to calm acidity and evacuate the stomach. Antifebriles: give these before meals, or 3 hours after. Iodic preparations: avoid rapid transformations of acids and starches by giving these on an empty stomach. Irritants or dangerous drugs; (Arsenic) give at the start of the meal. Laxatives: give on an empty stomach. Medication-Food: Administer ferruginous foods, cod liver oil, phosphate medications, etc., before and during meals.

ADMINISTRATION OF MEDICINES. Difficulties often arise in administering liquid medicine to a dog. So proceed as follows: enlist the help of a helper who, after sitting down, places the animal between his legs and squeezes his knees to prevent any defensive movements. Position yourself in front of the Dog, insert a finger between its cheek and molars, gently spread the cheek to form a kind of funnel, pour in the liquid slowly, while the helper raises the animal's head well to prevent rejection of the drug. Keep its mouth shut; if he does not want to swallow, keep him from breathing for a moment by squeezing his nose; this will force him to swallow.

As soon as the drug is swallows, prevent it being vomited by taking the Dog by its front paws and raising it onto the back ones; turn his attention away from the state of his stomach by walking him for a few minutes in that position. Thanks to this distraction, vomiting that would prevent the therapeutic effect does not occur.

With a large, strong and hard-to-handle Dog, use the following method: Secure it with two straps, one of which is attached to a belt that goes around the kidneys and the other to the collar. Join each of these straps by its free end to a hook fixed to a wall; in this way, defensive movements are naturally limited. Using a light strip of leather around the end of the jaw, lift the head and keep it at 45 degrees; then introduce the medicine into the opening formed by the slightly spread cheek.

Give solid or powdered medicines without difficulty by presenting the Dog with several small pieces of meat; place the drug dose in an incision made in the 3rd or 4th piece that the animal immediately grabs without chewing it, being unable to predict this substitution. The pills are generally active drugs, with a firm consistency, divided into small spherical or ovoid shapes, so as to facilitate their ingestion. This drug form allows you to give substances that smell and taste offensive. The capsules, formed from a solid shell usually made of gelatin, allow you to administer remedies with an unpleasant smell or taste. To administer the pills or capsules, open the subject's mouth, pull his tongue forward and place the medicine at the back; then let go of that organ, and swallowing occurs automatically.

It is more difficult to proceed with Cats due to their defensive movements. Mix liquid medicines with milk and drinks. Administer powdered substances which smell or taste unpleasant in the form of pills or granules, incorporated in meatballs, in butter or preferably in veal lung.

DISEASES OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM, PERITONEUM AND LIVER

PREVENT THESE VERY COMMON CONDITIONS AND THEIR CONSEQUENCES BY GIVING YOUR PETS HEALTHY HOUSING AND A SENSIBLE DIET ACCORDING TO THEIR AGE AND CONSTITUTION.

Illnesses of the digestive system, peritoneum and liver account for 50% of causes of death. The group of digestive system diseases is one of the most important in canine and feline pathology. Although diverse in their symptoms, these conditions have the same aetiology: poor hygiene and diet. Remove your Dogs from the harmful effects of unsanitary kennels (cold and wet); give them regular exercise; provide a mixed diet (meat and vegetable); avoid coarse foods, especially those rich in cellulose, which Dogs and Cats do not assimilate because of their reduced digestive system; avoid indigestible, spoiled foods, and especially avoid overeating; observe great regularity in the number and interval of meals; give unpolluted drinking water, etc., and you will significantly decrease mortality.

Examination of the digestive system includes exploration of the mouth, pharynx, oesophagus, stomach, intestine.

EXAMINATION OF THE SUBJECT. Mouth: Carefully inspect the muzzle internally to see the condition of the nose, lips and their corners. This done, insert a finger into the oral cavity, to approximately determine the local temperature and the general temperature. Spread its jaws to directly appreciate the smell as it exhales and any possible abnormal qualities: acidic, sour, foul or putrid. Sight will tell you if there is anaemia or hypertrophy of the mucous membrane at its various points. The appearance of the tongue provides a valuable diagnostic sign: tongue dry, furry, coated, dark.

To explore the mouth, use small speculums, or more simply use cords or two strips of bandage, tightly bound around each jaw and held in opposite directions, or place a piece of wood between the rows of molar, applied to the corners of the mouth and fixed with a ribbon behind the neck, or use a flat nickel-plated rod. By proceeding according to this method, you will very easily be able to note any wounds, cuts, various sores or specific eruptions (ulcerations, pustules) on the lips; signs of gingivitis and periostitis on the gums; inflammatory rashes on the tongue; dental irregularities or decay caused by foreign bodies lodged between the teeth.

Pharynx: Inspection tells you about possible deformation of the throat area; palpation tell you about the condition of the tissues, tenderness, the presence of abscesses, foreign bodies, etc.

Oesophagus: Its examination, when the passage is blocked in its neck area, gives you useful information; methodical palpation of the jugular channels allows you to detect oesophageal tumours and the presence of foreign bodies. To perform catheterization, secure the subject on a table with the head extended and jaws opened using a speculum or two ligatures in the opposite direction; use the probes used for exploring the urethra.

Stomach: The stomach is a membranous sac, located in the diaphragmatic region of the abdomen between the oesophagus and the intestine, where it assumes a transverse direction of the midplane of the body. Exploration is possible by inspection, palpation and probing. Inspection gives variable results, depending on whether it is performed before or after a meal; it provides information on the state of emptiness and makes it possible to detect the presence of foreign bodies.

Intestine: The intestines of predators are remarkable for their brevity and small size. On a medium-sized dog, this tube measures barely 4.5 metres in length; in the Cat it measures only about 2 metres. The small intestine rests on the lower abdominal wall. Palpation of the abdomen, performed lightly with the tips of the fingers, detects abnormal tenderness in acute enteritis or the presence of tumours, foreign bodies, intussusception, etc.; in the case of Peritonitis or Ascites, palpation makes it possible to perceive fluctuation.

Rectal exploration is a valuable means for the diagnosis of all visceral conditions of the pelvis and abdomen. To perform it usefully, evacuate the intestinal contents with a large enema. Introduce an oiled index finger into the anorectal canal; gently palpate the mass of convolutions of the small intestine and colon. This exploration can recognize food overload, intestinal strangulation, internal hernias, intussusception and volvulus.

Palpation of the abdomen and methodical exploration of the intestinal mass, the patient being examined first when standing, then lying on his back, often make it possible to detect the presence of foreign bodies.

STOMATITIS.

Inflammation of the oral mucosa, Stomatitis, is associated with seizing food or liquids that are too hot, irritating or caustic, the replacement of deciduous teeth, the build-up of tartar, dental caries, foreign bodies, etc.

Symptoms: At first, the mouth is hot, dry and gives off a stale, sometimes foul odour; the oral mucosa is swollen and has a uniform or slightly dotted red tint; it sometimes shows small vesicles and erosions. The dryness at the beginning is followed by profuse salivation (ptyalism).

Treatment: Give the patient food that is either liquid or does not require chewing efforts (milk or broth, to which you add a little raw minced meat). Treat the causative condition; remove tartar and decayed teeth, papillomas, etc. Give frequent injections into the mouth with a solution of potassium chlorate or sodium borate, at 5% or 10%, or vinegar diluted with water. If the stomatitis is ulcerative, touch the ulcers with a brush dipped in hydrogen peroxide diluted 1/4 or with tincture of iodine diluted with two parts water.

DENTAL TARTAR.

Tartar is a calcareous material which is deposited on the teeth of animals, especially in house-dogs. Aetiology: Tartar is due to various microorganisms which cause the deposition of mineral salts contained in saliva mixed with food materials.

Symptoms: This deposition occurs at the neck of the teeth, and the microorganisms inflame the free edge of the gum tissue. Little by little, the tartar creeps between the tooth and the gum, enters the tooth socket, which becomes inflamed; teeth loosen and fall out. As soon as the tartar causes gum lesions, chewing becomes difficult and the mouth becomes foetid.

Treatment: Remove, using a blunt instrument, the layer of tartar deposited on the teeth, and wash the mouth with a boric solution at 1% or 2%. If the gum is inflamed or ulcerated, touch it with tincture of iodine; if there is dry socket, have the loose tooth pulled out. Prophylaxis: Prevent tartar build-up through sensible dental hygiene (washing and brushing).

TOOTH DECAY.

Dental caries is characterized by progressive destruction of the tooth; it is best observed on molars and in old subjects.

Symptoms: The ailment manifests as discomfort when chewing, profuse salivation, a foul odour from the mouth and weight loss of the animal. While examining the mouth you will find, on one of the molar teeth, a blackish cavity containing food particles.

Treatment: Treatment consists of the removing the decayed tooth; perform this with caution so as not to break the weak crown of the tooth. Extraction requires special equipment: pliers with articulated arms and curved jaws, or special forceps.

DENTAL FISTULAS.

Dental fistulas are found as a result of cavities or alveolar periostitis; they are characterized by a narrow cutaneous wound, resistant to cauterization, which gives rise to a purulent, greyish, blood-tinged and foul-smelling liquid. A probe inserted into the wound stops at a tooth root or enters the oral cavity.

Treatment: If the fistula is recent, have it treated with debridement, curettage and strong antiseptic injections, or tincture of iodine. If it is old or complicated by alveolar periostitis, have the tooth removed. Feed dogs that have had dental operations with liquid or easy-to-chew food for a few days.

FOREIGN BODIES IN THE MOUTH.

Foreign bodies in the mouth are often found in dogs. These are bones, needles, pins, pieces of wood, fish bones, etc. These foreign bodies are found implanted in the tongue, the cheeks or between the teeth.

Diagnosis is easy; salivation, difficulty chewing, sometimes the inability to close the mouth, puts you on the right track; methodical exploration of the cavity provides more exact information. After immobilizing the Dog and separating the jaws, extract the foreign bodies, using ad hoc forceps or a blunt hook.

TUMOURS OF THE MOUTH AND LIPS.

The mouth and lips can be the site of benign tumours (papillomas, myxomas, cysts) or malignant tumours (cancroid, epithelioma, sarcoma, chondroma, etc.). Young dogs are particularly prone to papillomas, small whitish tumours, warty in appearance, scattered or confluent, that develop on the inner side of the cheeks and lips. Labial cancer, observed exclusively in the elderly, and in most cases on the lower lip, is characterized at first by a small flattened tumour, followed by a greyish, granular, bleeding ulceration which progresses slowly, but is quickly accompanied by subglossian or cervical lymphadenopathy (engorgement of the ganglia in the region). Papillomas are transmissible between young dogs; remove the largest growths with curved scissors; touch the others with a small cotton ball attached to the end of forceps and soaked in 1% acetic acid solution. Administer, in the morning on an empty stomach a dose of 30 cgr. at 3 gr. of calcined magnesia in a little milk as internal treatment. In labial cancer, total and early ablation is the only effective intervention.

A Ranine Tumour is a salivary cyst that is often encountered in dogs and whose only treatment is surgical; in addition to the unpleasant odour of the oral cavity, this lesion is characterized by discomfort when chewing, profuse salivation, by one or more tumours from hazelnut-sized to the size of a small egg, under the mucous membrane between the frenulum of the tongue and the molar arcade, or by a cystic tumour which occurs in the lower region of the throat.

LABIAL ULCERS IN CATS.

Symptoms: The cat is prone to a labial ulcer, called a Carcinoma, which occurs most often on the upper lip, sometimes towards the midline, sometimes on one side. At first, you notice the formation of a concave, regular, greyish wound, with a narrow area of hardening of surrounding tissues. By its gradual growth, this ulcer causes a semi-circular loss of substance, which can measure 1.5 cm. to 2 cm. and lets you see the teeth and gum. When the condition is in the midline, the nose may be affected. When the ulcer becomes general, it causes weight loss and sometimes death.

Treatment: The condition is parasitic and contagious; isolate the patient and support him with easily assimilable food, especially meat. Wash the ulcer several times a day with an antiseptic solution (1/5 iodine solution, or 10% methylene blue), then touch it with pure tincture of iodine.

PHARYNGITIS.

Pharyngitis, or inflammation of the lining of the pharynx, is mainly caused by cold, by ingestion of too hot food or caustic substances, by foreign bodies, etc. Microbes (micrococci, diplococci, pasteurella, etc.) constitute the real determining cause of Pharyngitis; the others are only predisposing or incidental.

Symptoms: At first, you observe difficulty swallowing coinciding with a slight tenderness of the pharynx, some coughing fits and a slight fever. In young or weak subjects, Pharyngitis can become phlegmonous [diffuse spreading inflammation of or in the connective tissue]; then you notice abscesses in the submucosal connective tissue, or in neighbouring lymph nodes; these cause difficulty in breathing, sometimes anxiety and bouts of suffocation; in cases of pseudomembranous pharyngitis, the general symptoms are marked, the breath is foetid and the pharyngeal mucosa is covered with greyish false membranes.

Always be careful with Dogs showing signs of Pharyngitis; do not engage in any local exploration until you have made sure that the subject is not rabid. Pet owners often say "My Dog tries hard to swallow, as though a bone is stuck in his throat," when the real cause is the onset of pharyngeal palsy, symptomatic of rabies.

Treatment: Protect the patient from cold and damp; give them liquid or easily digested foods: milk, broth or light mash. Reduce superficial inflammation using warm, moist compresses, held in place by a bandage; renew these every two hours. Then make a few local applications of tincture of iodine; calm the cough by dissolving about 2 to 15 drops of opium tincture in milk and by emollient or antiseptic fumigations. In phlegmonous pharyngitis, puncture deep abscesses. Prophylaxis: Avoid exposure to cold and damp, the ingestion of too hot food, and of irritating or caustic substances.

OBSTRUCTION OF THE OESOPHAGUS.

Obstruction of the oesophagus, often seen in young dogs, is caused by swallowing hard, large bodies, usually a bone fragment, fish bones, etc.

Symptoms: Difficulty or inability to swallow, profuse salivation, nausea, cough and dyspnoea characterize this disease. When the obstruction is in the cervical region, you may see a painful, circumscribed swelling at any point in the oesophageal groove or even clearly locate the foreign body.

Treatment: If the body is stuck at the start of the oesophagus, attempt extraction with forceps after the jaws have been spread with a speculum. If this does not produce a result, induce efforts to vomit by a subcutaneous injection of 0.5 cgr. to 1 cgr. apomorphine. If the foreign body is not ejected, push it back into the stomach with an oiled or Vaselined probe, and give a few teaspoons or dessert spoons of olive oil. In the event of failure, if the body can be perceived in the cervical region, perform an oesophagotomy.

DYSPEPSIA.

The Dyspepsia frequently seen in dogs are digestive disorders, independent of any pathological lesions of the stomach, intestines or their appendages.

Aetiology: These conditions are closely linked to incorrect food hygiene: poorly regulated, insufficient or erratic feeding. Dyspepsic disorders can result from changes in the functioning of the glands of the gastric mucosa; they generally begin with disorders of stomach secretion: hyperchlorhydria or hypochlorhydria.

Symptoms: Dyspepsia is manifested in Dogs and Cats by signs of discomfort and prolonged indolence after meals; these often go unnoticed. You may notice taste aberrations (pica), bloating, frequent belching, vomiting, and stomatitis with foul mouth odour.

Treatment: Diet is the bottom line of treatment; give the patient a lactic diet; with milk, broth, light soups of toast, raw meat minced or cut into small pieces, and well-cooked vegetable purees; decrease the amount of food at each meal and increase the number of meals. Treat hyperchlorhydria with alkalis (Vichy water, Vais water, baking soda); in case of failure which indicates hypochlorhydria, replace the alkalis with hydrochloric acid or lactic acid (2 or 3 gr solution p. 1,000). Combat abnormal fermentation with antiseptics: calomel (1 to 5 gr.), Benzonaphthol (5 to 50 cgr.) or salol (10 cgr. to 1 gr.).

Prophylaxis: Prophylaxis lies entirely in food hygiene; avoid illogical, poorly regulated, insufficient or copious food; observe great regularity in the number and interval of meals, especially in young dogs.

DILATION OF THE STOMACH.

Stomach dilation is seen mainly in older, naturally voracious, copiously fed dogs, especially those who have only one meal per day.

Symptoms: Along with the symptoms of dyspepsia, there is constipation or diarrhoea. The abdomen is large, often distended; percussion of the stomach region may denote, on the left side, a very extensive zone of dullness. Patients lose weight and get weaker. Prophylaxis: Avoid overeating and increase the number of meals.

MISCELLANEOUS CARE.

Dip a comb in formalin water and run it with the grain, then against the grain.

2 and 3. Brush vigorously with a brush soaked in formalin water.

3. A Japanese Dog's Boric Acid Sprinkle.

5. Using haemostats, remove any foreign material from between the digits of the paws.

6. Soap the outside of the ear and clean the inside with a cotton ball moistened with formalin water.

TO IMMOBILIZE AND GROOM A CAT. Keep the animal crouching on a table by grasping the skin with both hands at the neck and on the rump. Without letting go of the skin of the neck, use the other hand to comb and brush to remove dust and dead hairs.

A VISIT TO THE VETERINARIAN. Alsatian Shepherd Dog presented by Miss Geneviève Spitz for consultation with our collaborator Mr. Taskin. The Dog, lying on the operating table, is carefully examined by the veterinarian.

TO GIVE A PILL OR LIQUID. 1. To administer a pill or capsule, open the subject's mouth and place the medicine on the back of the tongue.

2. To immobilize a dog that is not very docile, grasp it between your knees and hold its paws and head.

3 and 4. Administering a potion from the bottle to a Dog and a Cat.

5 and 6. To make it drink liquid from a glass: insert your finger between the dog's cheek and molars; part the cheeks to form a funnel and slowly pour in the liquid.

INDIGESTION.

Indigestion is a temporary acute disorder of the digestive function, which usually occurs a few hours after ingesting too much food or poor-quality food, sometimes under the influence of an external cause such as cold, fatigue. Indigestion can also be the result of microbial self-poisoning, following paralysis or weakness of the digestive viscera. Dogs and cats that consume all kinds of food, foreign bodies or rotting matter, are very prone to stomach or intestinal indigestion; but the ease with which these animals vomit makes such digestive accidents mild.

Symptoms: The patient is depressed, worried, agitated, shows signs of mild colic, paces, lies down, gets up, complains; you sometimes notice salivation and nervous disorders.

Treatment: Induce vomiting by administering syrup of ipecac, or emetic, 3 teaspoons per day. Subsequently, if signs of depression persist, institute a milk diet for a few days. Prophylaxis: Through sensible feeding (sufficient number of meals varying with the age of the animals) avoid gluttony, ingestion of excess food, coarse or spoiled food, toxic substances or foreign bodies.

ACUTE GASTRITIS.

A most common disease, particularly frequent in young subjects, where it is a major cause of mortality. Gastritis, acute or chronic inflammation, has a complex aetiology, ingestion of coarse or indigestible food, too cold or too hot food, water tainted with irritating or caustic substances, foreign bodies, overeating, meals containing excessive fat, etc. Cold and dyspepsia are predisposing causes. This inflammation is rarely localized and often spreads to the intestinal lining (gastroenteritis).

Symptoms: Apart from the general symptoms (prostration, depression, febrile reaction), this disease is characterized by intense thirst, nausea and vomiting first of food, then mucous or bilious matter. The mouth is dry, furry, the tongue coated, the breath foul; palpation in the epigastric region indicates abnormal tenderness. The patient looks for cool places. From the start there is constipation which usually persists for the duration of the condition. You may observe jaundice as a complication during the course of the disease.

Treatment: Protect patients from cold and damp; give them a milk or water diet: milk diluted with Vais water, Vichy water or water with a little baking soda. Combat frequent vomiting with opium extract (2 cgr.), Sydenham's laudanum (50 cgr. to 1 gr.), or chloroformed water. Treat constipation with simple warm water enemas, or mucilaginous ones, or with a laxative (5 to 50 grams of castor oil). Stimulate the appetite with stomachics (tincture of gentian, cinchona, cola, etc.). After recovery, monitor the diet and health-care to avoid relapses; add a small dose of baking soda to its drink.

Prophylaxis: Avoid cold, ingestion of coarse or indigestible foods; observe great regularity in the number and interval of meals (especially with youngsters), use clean water.

ACUTE ENTERITIS.

Symptoms: While vomiting is the specific symptom of gastritis, diarrhoea is the hallmark of Enteritis; stools are frequent, semi-liquid, greyish, oily, often foetid; sometimes they contain small greyish-white flakes or bloody mucus. The febrile reaction is marked in proportion to the degree of infection; palpation of the abdomen indicates abnormal tenderness. You quite commonly see signs of mild colic and tenesmus [the need to defecate even though the bowel is empty]. In severe forms of acute enteritis, there is intense fever, the temperature can reach 41 centigrade, there is complete prostration, watery and profuse diarrhoea. Patients lose weight quickly; poison absorbed from the intestine can cause fatal disorders.

Lesions: Lesions are usually localized in the small intestine; the swollen, reddish mucosa, devoid of its epithelium, is covered with thick, yellowish-white mucus; it is sometimes softened in a few points; the mesenteric nodes are infiltrated.

Treatment: Apply the same health care as for patients with gastritis. According to the degree of illness, institute a water diet for 24 to 48 hours (boiled water, Vais water, Vichy water) or give in small quantities good quality food at the same time: a little meat, milk with added lime water and milk preparations (milk soup, rice, semolina and vermicelli soups). In severe forms of Enteritis, use a wet stomach wrap or emollient poultices. At first, achieve intestinal antisepsis by using a purgative; then calm the diarrhoea with the use of astringents: bismuth sub-nitrate (1 to 5 gr.), tannin (10 to 25 cgr.); opiates: tincture of opium, laudanum (I to VIII drops); intestinal antiseptics: calomel (0.25 to 1 gr.), salol (0.25 to 1 gr.), bismuth salicylate (0.5 gr.), benzonaphthol (5 to 50 cgr.), lactic acid (2 to 5 gr.). Use enemas of warm water with the addition of starch, potassium permanganate or laudanum (IV to X drops per enema).

Prophylaxis: Prophylaxis lies entirely in food hygiene: avoid the use of coarse, indigestible foods, and irritating or caustic substances, over-abundant meals, or mash containing excessive fat. Suppress, by a well-regulated diet, the gluttony and voracity of patients; give unpolluted water; reject empirical procedures (such as giving a large dose of coarse sea salt); avoid the harmful effects of cold and damp.

CHRONIC GASTROENTERITIS.

Chronic Gastroenteritis, a common ending to acute Gastroenteritis, can result from repeated ingestion of irritating, greasy or spoiled foods.

Symptoms: When chronic stomach catarrh predominates, you will notice disturbances in appetite, pale coating in the mouth, vomiting, first of food and then of mucus and bilious matter, constipation or diarrhoea. In the case of Chronic Enteritis, you will notice a decrease in appetite, and foul diarrhoea alternating with constipation. These two forms are frequently associated.

Treatment: In the case of chronic gastritis, institute the following diet: boiled milk, whey, broth with added meat juice, light soups, eggs; dilute the milk with 1/3 Vichy or Vais water or a small dose of baking soda. Calm the vomiting and stimulate the appetite using the treatment indicated for Acute gastritis. Gradually re-feed the patient to avoid relapses. Use the preparations indicated for the treatment of acute enteritis.

Individuals with chronic Gastroenteritis, especially in miniature breeds, exhibit sluggish digestion which often resists medical treatment. Combat this inappetence with healthy feeding: increase the number of meals, reduce their size, and above all vary the diet. Here are the foods and culinary preparations that can enter the menu of these delicate patients, a. Milk and milk preparations: solid creams made from flour, sweetened milk and eggs, liquid creams (sweetened milk and eggs), pasta pudding (semolina, vermicelli, noodles, tapioca), b. Broth, broth with added meat juice or eggs, c. Light toast soups, d. Minced or grated raw meat, e. Mashed well cooked vegetables. f. Dry cakes, biscuits, cookies, sugar, chocolate, etc., in moderate quantities.

TOXIC-INFECTIOUS GASTROENTERITIS [ACUTE FOOD POISONING].

This form of foodborne enteritis, with a very severe prognosis, is caused by ingesting rotten, spoiled meat. The bacteria and ptomains contained in these materials cause severe inflammation of the gastrointestinal mucosa and general disorders. Wandering and stray animals, and Shepherd Dogs are predisposed to it.

Symptoms: This poisoning is characterized by vomiting, signs of abdominal pain, profuse, fetid, bloody diarrhoea, intense fever, nervous phenomena, weakness, prostration, and coma. Death can occur within hours.

Treatment: Induce expulsion of toxic foods by vomiting (5 to 50 cgr. Ipecac); perform intestinal antisepsis (calomel 1 to 5 cgr.), benzonaphthol, salol, etc. Combat debility with infusions of caffeine, camphor oil; combat diarrhoea with astringents, opiates. (See "Treatment of Acute Enteritis.")

DYSENTERY.

Dysentery in dogs, characterized by frequent bloody evacuations and signs of colic, is generally a symptom of haemorrhagic gastroenteritis or various toxins.

Lesions: The disruption of the mucosa is sometimes very advanced (swelling, epithelial desquamation [shedding of lining], ulcerations, etc.).

Treatment: Subject the patient to a water or milk diet. Perform intestinal antisepsis by using a purgative (castor oil), calomel, salicylic acid, naphthol, etc.; relieve pain with laudanum, emollient enemas; calm diarrhoea with astringents: bismuth sub-nitrate, tannin, iron perchloride (5 to 15 cgr.). Combat fever with antipyretics (quinine, acetanilide); combat weakness, debility, with coffee, lightly alcoholic tea, injections of caffeine, camphor oil, etc.

GASTROENTERITIS IN PUPPIES [DISTEMPER].

Symptoms: This disease, of which simple diarrhoea is often the first stage, is characterized by lack of appetite, great thirst, signs of colic and tenderness of the stomach to pressure. Soon food vomiting occurs, then bilious or haemorrhagic vomit, and diarrhoea; faeces depending on the degree of intestinal infection are frequent, abundant and mucus, greenish yellow, streaked with blood, often foetid. Profuse diarrhoea and fever quickly lead to emaciation and exhaustion in young patients.

Treatment: Protect young Dogs and Cats with simple diarrhoea or gastroenteritis from cold and damp; in severe cases, perform a padded stomach wrap. If the wet nurse is ill or her milk is insufficient or poor quality, wean the young prematurely, and feed them with boiled cow's milk, given pure or diluted with rice water or lime water. If the diarrhoea is profuse, foetid, institute a water diet: boiled water, by the teaspoonful or dessertspoonful, for 24 hours. Combat vomiting with tincture of opium or belladonna (I to VI drops in a spoonful of cold water, every two hours); calm diarrhoea with lime water, astringents, intestinal antiseptics.