Author of

"Cat Superstitions," "Mummy Cats," "Intelligence In Animals," "Are Animals Immortal?" "Peculiarities Of The Cat World," "Why We Keep Pets," "Why Cats Purr," Etc.

Andrew Melrose Ltd.

London & New York

Printed in Great Britain by Billing and Sons, Ltd., Guildford and Esher

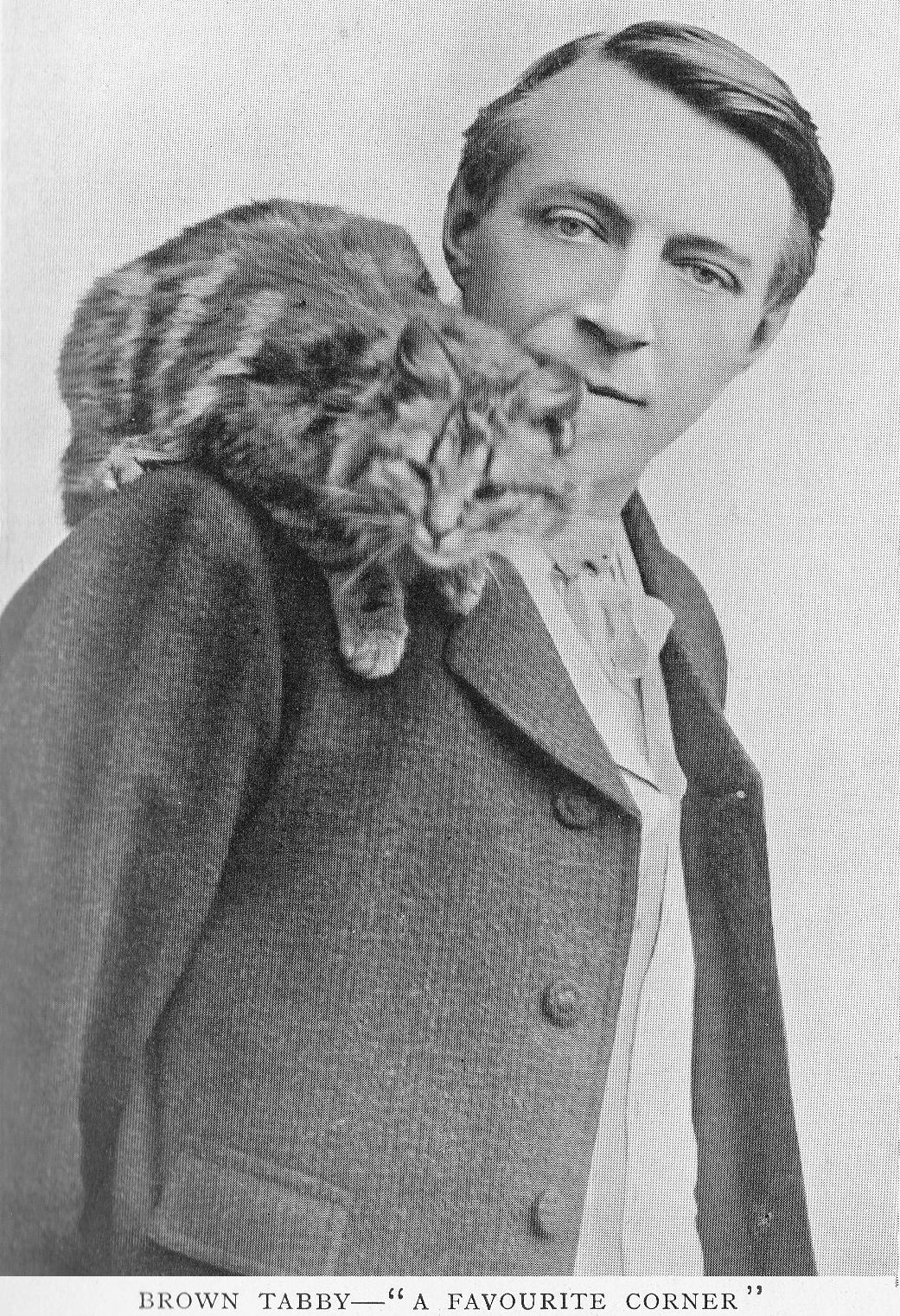

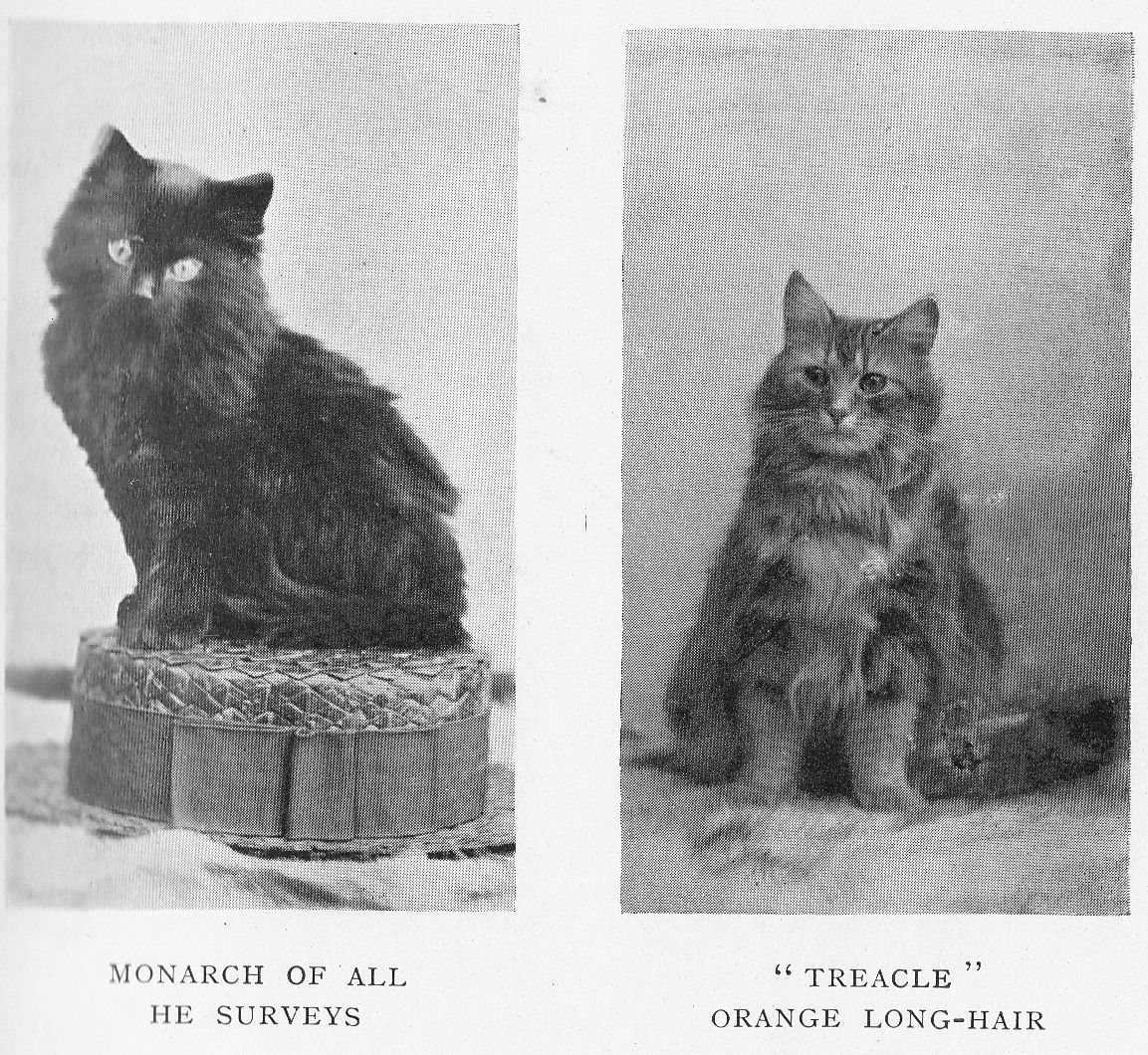

Dedicated to that intelligent little friend my orange long-haired cat yclept Treckie.

CONTENTS

I The Cat's Unique Position

II - Mummy Cats

III Colour in Cats

IV Pussy's name

V The Cat in History

VI Superstitions about Cats

VII Mentality in Cats

VIII Cat and Other Animal Anecdotes

IX The Cat's Senses

X Pussy's Structure

XI Concerning Cats, Large and Small

XII Cats in Captivity

XIII - Are Animals Immortal?

XIV Those Interesting Kittens

XV - Curious Points in Cats

Bibliography

CHAPTER I - THE CAT'S UNIQUE POSITION

Do you know that Puss has five toes on each of her front paws, but only four each on the back ones?

The Cat holds a very uncommon position in the animal kingdom, and there are many interesting points about her that most people know nothing of. Puss has been a domestic pet and a companion of Man for many centuries, and it is impossible to get back historically to the time when this was not the case. We cannot, therefore, explain why Man first made a pet of the Cat, unless it was because of its utility as a mouser. We are then faced with the natural query: How was it discovered that Puss was a useful vermin-killer?

It is the old problem again, in a new form: Which came first, the hen or the egg?

It is not generally realised that no savage race has ever made pets of Cats. Dogs are tamed into service for hunting or tracking; cows, goats, or similar animals for their milk; but our friend Puss demands civilisation. This is a very curious and interesting fact, and demonstrates the essential difference between Cats and dogs Man's two principal animal companions.

Puss is an animal of higher physical organisation than the dog; she is more highly strung and less plastic, and often suffers unjustly by comparison. The domestic Cat is in many ways very similar to Man, though it is true that this may partly be due to their centuries of life in common.

It is not too much to say that, after Man, the Cat is the most independent of all animals. As a family, the Felidae (cat-shaped animals) live a solitary life, or at most have one companion of the opposite sex. Their sexual feelings are strong, and the mother-cat is notoriously devoted to her young. In Nature the Felidae have to fight their own battles, strive single-handed in the great struggle for existence. But the dog comes from a stock that has always lived in packs, dominated by a head and controlled by brute force.

You can strike a dog and it fawns at your feet; not so the Cat, who never fully forgets a blow. A trainer can quickly teach a dog to perform tricks quite foreign to its nature; but it is far more difficult to coerce Puss, not because her intelligence is less than that of the dog, but because she is an independent creature used to thinking for herself. She does not want to perform; she is keenly sensitive to ridicule; she acknowledges no master, but gives and expects friendship and equality.

Make a friend of a Cat, and she is far and away more faithful than a human friend. Many people, ignorant of the truth, state that a Cat is more attached to a place than to a person. This is quite a false idea, though Puss, from the nature of her prehistoric wild life and instincts, hates a disturbance or a removal to new surroundings.

But this dislike to a removal has nothing to do with the question, and merely serves to hide or obscure the real faithfulness of the Cat's nature. This independence of nature makes Puss resent any ill-treatment that she does not understand; but, as a rule, she is very gentle when children (whom she knows) pull her about in unintentional rough ways that must often be very painful.

So in her very independence the Cat comes nearer to Man than almost any other animal. No wandering people have ever gained her sweet companionship; she cares little for the world at large, greatly dislikes the discomforts of travel, and is a true home-lover. She is the friend of those who are too happy or too wise for restlessness!

"However mysterious and informal may have been her birth," writes Agnes Repplier, "Pussy's first appearance in veracious history is a splendid one. More than three thousand years ago she dwelt serenely by the Nile, and the great nation of antiquity paid her respectful homage. Sleek and beautiful, she drowsed in the shadow of mighty temples, or sat blinking and washing her face with contemptuous disregard alike of priest and people."

As a matter of fact, the earliest known record of a Cat dates back to about 1800 B.C. At that time Puss was a recognised domestic pet, so we can only wonder as to the dim and distant date when first she was rescued from the rough vicissitudes of wild, uncared-for life. Yet even today, after forty centuries of (more or less) peaceful domestic life, Puss still carefully washes her jaws and forepaws directly after a meal, an instinct passed down through countless generations from the wild days when any dripping blood from mouth or claws would have betrayed her lair and sleeping-place to prowling enemies!

Many attempts have been made to define the exact meaning of the word "instinct." Dr. Murray's Oxford Dictionary gives the following:- "Instinct an innate propensity in organised beings manifesting itself in acts which appear to be rational but are performed without conscious design or intentional adaptation of means to ends."

Herbert Spencer holds a somewhat singular view i.e., that instinct was a higher development of reason, which it has replaced, owing to the more perfect adjustment of inner relations to outer than exists where mere reason is concerned.

One can hardly accept this view. Reason may often car, but so does instinct. Take, as an example, the dread of the dark so common among human young. This curious instinct dates back to the time when night was really a time of stress and danger to primitive Man. In the same way a Cat will generally turn round and round in its bed or even on the open floor before it settles down, just as its primeval ancestor did in the long undergrowths when it sought to conceal its resting-place from prying enemies. In this way the wild-cat made a comfortable hollow space for itself, and, at the same time, brought together the tops of the long grasses so as to hide the sleeping animal.

Perhaps a simple and useful definition of the word "instinct" would be: an inherited memory of useful actions.

Mr. Douglas Spalding found kittens to be imbued with an instinctive horror of the dog before they were able to see it. He tells us: "One day last month, after fondling my dog, I put my hand into a basket containing four blind kittens three days old. The smell my hand carried with it set them puffing and spitting in the most comical fashion." (Nature, October 7, 1875, p. 507)

This typical example of "instinct" was clearly an inherited memory carried forward for countless generations; yet a few weeks later those same kittens would, by the exercise of reason, be quite friendly with that particular animal, but would retain the strong protective dislike for dogs in general.

Yes, Puss holds a very uncommon position in the animal world: from its peculiar independence of nature which resists subjection to Man, in striking opposition to all other animals; the very large vocabulary of the Cat, which at times will "chatter" quite obviously in its anxiety to tell its news or thoughts; the strong feeling of "home" love (shown by no other animal); the structural resemblance in many ways of brain and vocal cords of Man and Puss; and the uncommon "purring" sound made by the Cat when pleasurably excited.

No animal sings but Man except, of course, birds, whose case is different although the purring of the Cat can best be described as monotone singing. The peculiar sound very closely resembles a pedal note on the organ, or the vibrating undertone of the bagpipes. It has been maintained that the purring of the Cat arose from the fact that the animal is carnivorous, that it killed its prey by the powerful grip of the teeth, and that the monotone purring was caused by the exhaling of the breath through the incoming rush of blood from the newly killed "food." In other words, that a Cat purrs in the same way as a man gargles.

This suggestion will hardly bear keen examination. In the first place, the incoming rush of arterial blood would be too great and would almost certainly cause suffocation; in the second place, it is well known that a Cat will purr while licking its young, sucking the tip of its own tail, or caressing the hand of the friend who owns it. None of these actions could be performed by the tongue if the Cat were maintaining a film of moisture in the throat in order to "purr."

The explanation is an ingenious one, but needlessly far-fetched. The vocal cords of a Cat more nearly resemble those of Man than in the case of any other animal, and it is only natural to assume that purring is a simplified and primitive song. In the Cat there are two kinds of vocal cords true and false, so-called. The upper or false vocal cords are said to be used in purring, and, indeed, appear to have no other purpose. By means of the muscles attached to the lower or true vocal cords the tenseness is regulated and the various pitches of voice are produced.

It is by the use of this muscular tension on the vocal cords that Man is enabled to sing. Puss uses the less flexible "false" vocal cords and can only produce a monotone singing note. But except for the birds, Man and Puss alone are singers, and this surely should be a bond of union between ourselves and our faithful (though very independent) furred friends.

CHAPTER II - MUMMY CATS

According to the chronicles, there was no Cat in the Garden of Eden; and Charles Lamb wondered how far this loss was responsible for Eve's lapse into sin. Had our renowned ancestors made a pet of the Cat instead of the Serpent - But it is impossible to follow such a speculation very far!

The earliest historical records of our four-footed friends are found in Egypt, where, some four thousand years ago, Puss was not only petted, but venerated, having her place in the temples, guarded alike by priests and people. Egypt then was the great granary of the world; but it does not therefore follow that Cats were kept to keep down the mice and other vermin. It is quite probable that this was an "acquired" art, developed after Puss became associated with Man. The Cat family, by natural habit and instinct, are tree-climbing creatures, and one part of their natural prey would lie birds. In addition to this, the Felidae prey upon warm-blooded animals, frequently of greater size than themselves, and in order to capture these, they hide in the long grass or undergrowth and spring unexpectedly upon their victims.

None of the Cat tribe are built for long-distance hunting, as are the dogs and wolves, and all their habits point to the open for their night work, and warm caves or lairs for their sleeping daylight hours. If we think this over carefully, we shall see how extremely doubtful it is that the Cat should be, by nature, a mouser. And, in Egypt, Puss was certainly venerated and held sacred, and that would hardly have been the case had she merely been introduced to protect the grain stores.

In this connection, we must also remember that Puss is a very dainty creature, fussy over her food, and therefore hardly likely to select rats or mice or any other vermin. The Cat has a very marked dislike for any strong or unpleasant smell, though certain delicate scents attract her very quickly.

Basil Hall relates that tigers are afraid of mice, and it is well known that lions in captivity will allow rats to play about in their cages. In face of these facts we must conclude that Puss is not, by instinct, a mouser; but probably developed the habit, in civilised homes, by springing after the quick-moving grey shadow which she mistook for a bird.

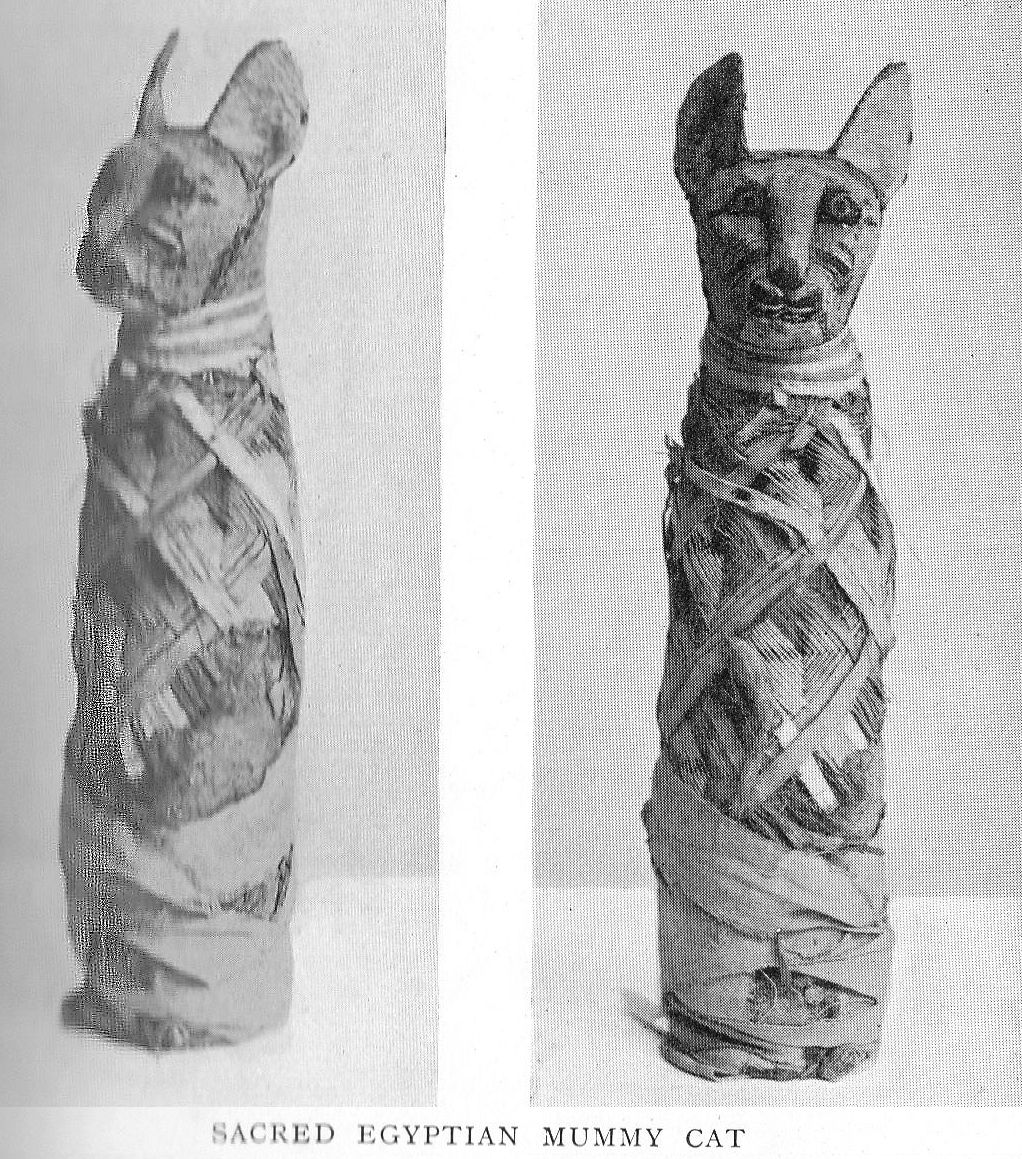

The goddess Pasht (or Bubastis) was represented with a Cat's head. A temple at Beni-Hasan, dedicated to Puss, is as old as Thothmes IV., of the eighteenth dynasty, about 1500 B.C. She is mentioned in the seventeenth chapter of the Ritual, and the coffins of the eleventh dynasty are inscribed with that chapter, which (according to Lepsius) would carry us back to about 2400 B.C. Behind this temple (at Beni-Hasan) are pits containing a multitude of Cat-mummies. Indeed, so great was the number of these little mummied pets of the ancient Egyptians that they were actually broken up and sold by the ton as manure for the fields!

Poor little Puss! How different from her treatment a thousand years or more before the birth of the great Christ! It is true that the great veneration in which she was then held provoked bitter jests from travellers from other lands, but then, as now, the saying was only too true: "Other people, other gods."

There was the enforced mourning, the shaving of eyebrows, and other symbols of woe, which followed the death of even the smallest kitten; there was the law which forbade the sinful slaying of a Cat. So great was this latter peril that an Egyptian who chanced to witness Pussy's death would stand trembling and bathed in tears, protesting to the world at large that he was not responsible, that he "didn't do it."

The temples of Bubastis (a city of Lower Egypt, now called Tel Basta), of Beni-Hasan (commenced by Thouthmosis IV.), and of Helipolus were the most sacred haunts of our soft-coated friend. There her little corpse was lovingly embalmed and buried in a gilded mummy case, with elaborate ceremonial.

The actual reason for embalming dead bodies, man or animal, is somewhat doubtful. The general feeling seems to have been that the animal body was essential as a tie or connection line between the soul (or Ego) and the earth interests of the deceased. They did not expect the resurrection of the actual physical body. This is proved by the removal of the vital organs before the body was embalmed. And we know that the Romans burnt their dead in order to free the soul more quickly from the lower ties of earth. So, for some reason, it would appear as if the early Egyptians deemed it an advantage that the Ego should never be freed, but should be able to keep in touch with earthly human affairs.

Apparently this could only have been from selfish motives, for the benefit it brought to living generations of men and women. In the reign of Asychis, money circulating very slowly, a law was enacted that a man might borrow money if he gave his father's body as a pledge. If he failed to refund, he lost the right of personal burial anywhere, nor could he entomb any of his relations who might depart this life during the continuance of the loan.

The principal aromatic substances used for embalming were bitumen, balsam, cedar, honey, wax, and resin. But for our little Cat friends, a bath of bitumen was the usual method, the dead animal being plunged in bodily. Undoubtedly this would affect the colour of the fur, and in the only unwrapped specimen at the British Museum the coat is of a deep orange.

It is somewhat difficult therefore to say, offhand, if this is the natural colour of the Egyptian Cat, or whether the colour is due to the use of bitumen, which would, undoubtedly, stain orange. We may, perhaps, assume that the bath would be a weak one, not powerful enough to absolutely dye, or disguise, the original shade of the fur. And the natural colour of the Cat tribe is a tawny one, as in the lion, tiger, etc. There are no signs of marks or bars on this (British Museum) specimen, which probably was a shaded, but not tabby, sable.

When we come to consider (in a later chapter) the question of colour in Cats, we shall find some very curious and interesting points. How can we explain the entire absence of tortoiseshell male Cats, though a few tortoise-and-white have been reared? Why should the Introduction of the white patches in the colour of the affect the question of sex?

We shall also find another curious colour problem. Until a few years ago, all our orange Cats were males, and all had white chins. Fanciers set to work to breed out the white and thus produce a pure self-orange, and, in doing so, they successfully bred females! How can we explain this, when we know that white Cats are freely produced, male and female, in the same litters? Yet the introduction of white patches in tortoise-shell Cats has led to the much-wished-for toms; while the elimination of the white in orange Cats has correspondingly led to the breeding of queens.

These curiosities of colour in our soft-footed little friend obviously show that the Cats of to-day are not directly descended from the early Egyptian Puss.

The mummy-cat that we have been examining has rather long fur, though not so heavy as that of the cultivated modern "Persian" Cat. In build, also, the animal is different, being longer in body and in tail, as well as of a slighter build. The rib capacity is shallow, conclusively proving that Puss is not a true hunter. The upper leg is long and the foot broad; the neck and head are also long, though the mask is not foxy, a defect often seen in the modern short-hair Cats, though breeders of to-day are correcting it.

The ears are small, so are the mouth and nostrils (corresponding with the shallow lung capacity); the eyes are long and slanting. Nowadays our Cats have perfect round eyes, a feature of great beauty in a well-kept pet. One mummy-cat in the British Museum (No. 35858) has an artificial eye according to the label, "inlaid obsidian eyes" made from volcanic glass. The colour chosen is a deep orange or copper, as nearly as possible the same as the ideal colour of to-day!

The collar-bone is somewhat large, the tail much longer than in our modern Cats.

Although Puss was thus reverenced and mummied -in ancient Egypt, she was seldom buried with humans, except among the lower classes. A few exceptions to this rule have been found, but as a general practice the mummied Cats were buried in their own special sepulchres in various parts of the country. This marked and deliberate separation of Cats from their masters, after death, is rather difficult to explain when we remember that during the famines that afflicted Egypt from time to time, though the people themselves were driven to eat human flesh, the sacred animals were invariably respected, being fed principally upon fish.

The word "mummy" is, nowadays, used in connection with the actual embalmed body, yet it should apply to the essences used in the process. It would appear to be derived from the Arabic "Mum" (wax) or "Amomum" (a kind of perfume), or perhaps (and more probably, in our opinion) from the Persian "Mumiya" (bitumen, the actual drug used). Mummy, as a medicine, is recorded as early as A.D. 1100, and in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it formed one of the ordinary everyday drugs, and was obtainable from any of the apothecaries' shops. Tombs were searched and the dead bodies were broken into pieces and sold as mummy, the drug being an especial favourite in France!

Lord Bacon ("Sylva Sylvarum," Cant. X., S 980) says: "Mummy hath great force in staunching of blood which . . . may be ascribed to the mixture of balmes that are glutinous."

But poor little Puss, as we said before, was broken up by the thousand and used as manure for the fields at thirty shillings the ton!

CHAPTER III - COLOUR IN CATS

Variation in colour is a subject about which there will always be much controversy. The generally accepted theory of colour in Nature is that it is "protective" that is to say, that certain colourings help the animal in its struggle for existence. To a great extent, no doubt, this is true, but it remains very difficult to explain variation in colour if we accept the above theory in full. If Nature has been struggling for centuries, by means of the survival of the fittest, to fix certain valuable colourings and markings, why is it so easy to produce variation in this protective quality?

For Instance, albino strains frequently arise in nearly all races. We have white cattle, horses, sheep, pigs, dogs, cats, birds, trees, plants, deer, bears, wolves, rabbits, mice, rats, etc. In a few cases the albino strain has been established by man in preference to the natural stock, as, for instance, with sheep and pigs.

In dealing with this question of colour, as with all matters of heredity, we must remember that all domestic animals have developed a variety of favourite strains, which, in time, are recognised as breeds; and the individuals of such distinct strains are spoken of as "purebred." The word "thoroughbred" is sometimes erroneously used to designate such animals, but this term is properly the breed name of the English running horse. So we can have a pure-bred cow, but a thoroughbred is a horse, and a particular type of horse at that.

It is interesting to note that colour does not always blend in life as it does on the artist's palette. If we breed from white and black in Man, we get a mulatto, but this is not the case in (for instance) the pig, where we get black, or white, or spotted, never roan or mulatto. In horses the colours sometimes blend as in roan or grey animals, but not always, black horses with white points being common. This curious anomaly is also seen in Cats, where we find numberless black and white specimens as well as many that are more truly described as white and black while, in addition, as the result of blending, we have the beautiful soft grey, known as silver or chinchilla, as well as the very popular blue, which is really a pleasant slate colour.

Yet in the case of the domestic sheep, we have either white or black, a very curious preference on the part of the breeder, retaining the albino strains and the melanistic (excess of colouring matter) strain, with no intermediate colour.

Melanism signifies a darkness of colour resulting from abnormal development of black or dark pigment in the skin and hair. It is far rarer than albinism, due to an absence of colouring pigment. It is interesting to note that the Siamese Cat is the only animal known to us that shows both melanism and albinism in the same animal as the recognised character of the species! The blue eyes and the white body colour are clearly due to albinism, while the dark "points" are only too obviously due to excess of colour pigment in certain characteristic parts of the animal anatomy.

As the Siamese Cat grows old, these tendencies merge into each other, more or less, the white body colour deepens, while the dark points become lighter, until the whole animal becomes more or less a pale chocolate or deep biscuit colour. No explanation has ever been offered for this curious change, and one fails to see what possible "protective" or other use it can be.

Undoubtedly "tabby"-bred Cats have a marked tendency both ways. In many specimens the black bars almost obliterate the original body colour, while in others the markings are very narrow and faint, often degenerating into spots. And, until quite recent years, all tabby-cats had white chins, chest, tail-tip, or other similar albino points.

Poulton ("Colour of Animals") puts forward the sensible suggestion that all animal colouring must have originally been non-significant, because colour pigment occurs abundantly in the internal organs and tissues. We must also bear in mind that, apparently, the uter colourings of skin and fur conform to the skeleton of the animal, as in the well-known case of the dark mark along the donkey's spine. And in the tabby-cat we again find this dark spinal mark, with bars down the ribs and round the limbs at (or near) the joints.

If colouring is "protective" in character, these marks may serve to direct attack to the bony skeleton and thus preserve from injury the softer vital organs. On the other hand, we may reasonably suppose that colour development to a great extent depends upon the direct action of the sun's rays upon the pigment in the hair and skin, and, if so, the underlying bone may easily turn back the light waves (as it does in the case of X-ray photographs) and thus intensify the colour. If this is accepted, we are forced to conclude that these body marks are not "protective", but are merely natural chemical results due to light and heat.

Again, Grant Allen states that the white marks on the head of a tiger correspond to the distribution of the infra-orbital nerves, and claims that there must be some distinct connection between the nerve supply and the colouration of the animal. And all hunters of big game confirm the fact that the spots of the jaguar look like round patches of sunlight, such as would be seen through a screen of leaves, and that the stripes of the tiger closely resemble the tall grasses among which it moves. So even if the origin of the body and fur markings is a commonplace chemical one, we find it almost impossible to pass over the protective value of such colourings.

Our difficulties, however, do not end here. Mr. Gregson (Zoologist, p. 7903) gives the results of his experiments with moths, and shows that food undoubtedly affects the colour. A diet of heather darkened the colours, whereas elm produced quite dull tones, almost markless. Thorn, on the other hand, deepened the red tints and the moths were all well marked, while grass intensified the yellow pigment. Those fed on birch were all beautifully marked, but those fed on currant were invariably light. The, colour changes thus brought about are obviously due to the change of food, the deposit of pigment (both as regards quantity and quality) being a question of waste matter. This easily explains the darker colourings, the deepening of the reds or yellows, but why should a diet of birch or thorn produce beautifully marked specimens, while those fed on elm were almost markless?

Another curious point to remember is that a state of albinism does not do away with the markings. For instance, the "eyes" on the fan (tail) feathers of a white peacock are quite distinctly seen and readily recognisable. It is impossible to connect these with any bony under-structure, and they are no doubt due to hereditary influence. The albinism is not quite so complete where racial markings have for centuries been displayed.

We get the same peculiarity in some of our self-coloured Cats. Blues and blacks, for instance, frequently show tabby markings. This is not noticeable in whites, though a cream tinge on the spine is often found, due to incomplete albinism. It is rather curious that the extreme tip of the tail should be so sensitive to colour changes, but it is hardly ever true to colour. In most Cats it is much paler than the body colour; in blacks it is often a dark brown; in orange Cats it is frequently cream; while in creams and tabbies it degenerates to white. On the other hand, it is often cream in white Cats where albinism is shaky.

MacCurdy, describing his experiments with rats and guinea-pigs, quotes the case of a wild grey male rat, mated to a black female, the litter of seven young being all grey, with a small patch of white on the chest. At first, we are inclined to blame the black female for this curious albino variation, as these white patches are so often, in Nature, associated with melanism (blackness). But the same wild grey male was afterwards mated with an albino female, and the litter of young were exactly the same, all grey with the small white patch on the chest! Obviously, therefore, it descended from the grey rat, and this makes it very difficult of explanation. MacCurdy, in a further experiment, mated a wild albino male rat and a wild grey female; but the young all bred grey for three generations. In this case, therefore, it was the female who transmitted the colouring.

Alfred Tylor, in his book upon the colouration of animals and plants, goes very fully into the origin of colour. Put briefly, his suggestions are as follows:

That the lowest forms of Protozoa themselves the lowest members of the animal kingdom, simply masses of jelly-like protoplasm with no distinct organs have no system of colouring, being merely a uni-tint, generally a dull brown. In the higher members of Protozoa, there is a tendency to development in the shape of a pulsating vesicle, an incipient "organ." This vesicle is invariably tinged with a different colour. Here, therefore, we are brought into contact with the first trace of a system of colouration in the animal kingdom.

It is owing to this all-pervading natural principle that we find the extreme points of quadrupeds so universally decorated the tips of the nose, ears, tail and feet. There is an all-powerful tendency in Nature to do again what she has once done.

Colour variation, therefore (he claims), depends upon the distinctive action of internal organs and bone (or other opaque matter) as against that of light. The physical cause of colour, as seen by the human eye, is due to the vibrations of light, chiefly from the sun. The mean speed of these vibrations is 185,000 miles per second. In that brief space of time, could our eye nerves work quickly enough, we should recognise four hundred and fifty million million (450,000,000,000,000) tiny wavelets of colour pass (in a single second, remember), and as we looked upon the last of these, the first would already be 185,000 miles away!

Truly, Nature's doings are stupendous.

It is easy, therefore, to realise that self- coloured animals are non-existent. We may call them so for simplicity and convenience, but it is against every tendency of Nature. The so-called self-colour is made up of a multitude of shade variations, all closely approximating.

There is one general law of colour, universal in application, that colour is invariably most intense upon that surface on which the light falls. In most animals, obviously, this is the back. But colour, where diversified, follows the anatomy of the animal and changes at definite points (such as joints) where any special function changes. In tabby, or barred animals, repetition accounts for the "rib- marks" so often continued into the dorsal region, as Nature has a marked tendency to continue variation (of any kind) when once begun.

The hereditary continuance of definite colouration depends upon the varied combination of three natural laws:

(1) The law of heredity, by which the offspring would naturally resemble one or other of the parents; (2) the law of variation, by which the offspring has an individual character, differing from either parent, because due to a mixture of the characteristics of both parents; (3) the law of multiplication or survival of the fittest, by which more individuals are born than can possibly survive, thus automatically tending to weed out and eliminate the unfit.

Cats generally have dark stripes over the dental nerve and cheek bone, as also along the orbital nerve on the forehead; dark rings round the ears; and marks on the jugular vein. Colour variation, as already stated, appears to be primarily due to the great nerves and nerve centres, bones, or important vital organs, the stripes so common on the head (and so difficult to breed out for self-colours) falling into two lateral masses corresponding with the cerebral hemispheres, and separated by a straight line corresponding with the median fissure of the brain.

It is rather curious to note that, while the tabby (or barred) type is the most common among our domestic Cats, a self-tawny colour is more general among the big Cats. Beddard ("Animal Colouration") states that this tawny colour is due to a lack of moisture in desert animals; and without doubt we may assume that it is not due to a yellow pigment (as such), but to the uniform distribution of a small amount of dark pigment.

We know that the baby lion is more or less spotted (traces of spots can also be seen in the female), showing the descent from a spotted ancestry; but so also is the baby tiger, though in the latter case the spots develop into the well-known stripes. This forms an interesting proof of their original common ancestry, acted upon by the rigid laws governing the survival of the fittest, the lion and puma living in open country under the protection of their self-coloured skins, while the tiger with his stripes finds safety in the jungle. The leopard and jaguar living in forests retain the original spots.

According to Beddoe, dark-haired humans (in Britain) are far more prone to phthisis than the fair-haired. He thinks that this explains the elimination of dark people from cold climates; so apparently fair people are less fitted to survive, or become dominant, in hot countries. The pale tawny colour of our "big Cats" seems to contradict this.

Tylor, in his "Colouration of Animals", suggests that all stripes and markings began as spots, due to some local disarrangement of the colour pigment. He quotes the ordinary rash, as seen in diseases such as measles, which begins as a set of minute red spots which run together and become bars. We have already drawn attention to the spots on the baby lion, and must not forget that the tawny adult has a very marked dark dorsal stripe, while the nose and other points are emphasised in colour.

Tylor's theory of colour is an interesting one, and is well shown in the following brief reference to butterflies and moths, probably the most beautifully coloured creatures in the universe:

"The wings are moved by powerful muscles attached to the base of the wings close to the body and to the inside of the thorax, all the muscles being necessarily internal. There are two sets which depress the wings; firstly, a double dorsal muscle, running longitudinally upwards in the middle division of the thorax, and secondly, the dorso-ventral muscles of the hinder division of the thorax, which are attached to the articulations of the wings above and to the inside of the thorax beneath. Between these lie the muscles which raise the wings and which run from the inner side of the back of the thorax to the legs. When we consider the immense extent of wing as compared with the rest of the body, the small area of attachment, and the great leverage that has to be worked in moving the wings, it is clear that the area of articulation of the wing to the body is one in which the most violent movement takes place. It is here that the waste and repair of tissue must go on with greatest vigour, and we should, on our theory, expect it to be the seat of strong colour emphasis. We commonly find it adorned with hairs, and the general hue is darker than that of the rest of the wing and never lighter than the body of the wing. Even in the so-called whites, this part of the wing is dusky."

Colour undoubtedly fails after death, which we should expect if we accept the theory that the deposit of pigment is due to waste elements caused by extreme physical effort and repair.

It has been urged that the constancy of animal colour indicates utility in the struggle for existence, and that the easy variability of domestic animals is due to the fact that Man has relieved them of this constant strain. This may well be the case, for, supposing a marked variety occurs in a wild species, there are many chances against its survival. It may not even reach maturity, its variation from type possibly setting the parents against it; or, again, it may not find a mate, and, if it should, the offspring might resemble the female, as there would always be such strong hereditary influences against the perpetuation of the variety.

If, however, the human fancier wishes to carry on this chance variation, special care is taken of the young animal and a suitable mate is found.

"The fact is [says Beddard] that not only is colouration, with a few exceptions, constant for a given species, but it is also, with a wider range of variation, constant to genera and to families. We find green to be a very common colour among parrots, touracons, and other tree-frequenting birds, but this colour does not occur at all in plenty of other genera and families which equally live among trees."

Green, however, appears to be an impossible colour among mammals, though many of them, such as the Cat and monkey families, live among trees. A green Cat would be a distinct novelty, but is probably quite an impossibility.

It is, indeed, a remarkable fact in Nature that brilliant colours are absent in the Mammalia. To this rule there are no conspicuous exceptions; a few monkeys have red or blue patches, but there are no mammals which can be compared in point of brilliancy and variety of colour even with such a plain and unobtrusive bird as the common everyday chaffinch.

The colours of mammals are generally confined to dull shades of brown and orange, with black (melanism) and white (albinism). The Cape golden mole appears to be one of the few exceptions, and it is remarkable that it should be so in an animal that spends most of its time underground. It is very difficult to imagine that its bright colouration is of any protective value to the creature.

Many experiments have been made to test the effect of food upon colour pigments. It has, for instance, been proved that cayenne pepper will alter the yellow colour of canaries to an orange red. But this can only be done in very young birds whose feathers are not matured, or through the old birds while sitting on the nest, giving them food containing cayenne, with which, in their turn, they feed their offspring. But when carmine was introduced the yellow colour was destroyed and the birds became white. This unexpected result was due to the fact that a mixture of violet and yellow produces white.

Temperature and moisture also affect colour, and no doubt they act both directly and also indirectly through food. For instance, it is well known that albinism (or whiteness) is much more prevalent in northern districts. The colours become less sharply defined, then gradually blend with the surrounding tints; the red first disappears, then follows blue, while yellow remains the longest.

This seems to suggest that mammals, as a class, originated in the northern districts of the world, and birds in the warmer and more tropical parts. An objection may be urged that Alpine plants are usually very brilliant in colour, but of course, the pigment in mammals, birds, and butterflies is very different from that of the flowers, the animals being without chlorophyl, so that the same conditions may, physiologically, produce very different effects.

Mr. Wallace, however, points out that we must not rashly assume that heat and light are responsible for colour. It is true, he admits, that there are more brilliantly coloured animals in the tropics than elsewhere; but then it is equally true that there are more animals. Animal life is naturally at its maximum in the tropics.

Sexual difference of colouring is seldom seen among mammals, the only instance worth recording being in the lemur, a species of monkey or ape. In this animal (Lemur Macaco) the male is black and the female brown. But in another lemur (L. varius) there is so much individual variation of colour that scarcely any two appear to be coloured alike.

This undoubted animal characteristic destroys at once the old-fashioned idea that the original male Cat (of the type from which our modern domestic Cat is descended) was an orange and the original female a tortoise-shell, or tricolour. This belief was long held because all orange Cats were males and all tricolours were female. It was therefore only natural for non-scientific Cat lovers to conclude that they represented the male and female of the same original species.

Such an idea will not bear the slightest investigation, and in this connection we must bear in mind the stubborn fact that, beyond the slight essential structural differences, there are practically no sex variations among mammals, the flowing mane and heroic build of the lion being a striking and unusual exception.

In recent years, too, the sex-colour difficulty mentioned above has been overcome. Breeders now possess plenty of orange queen Cats on the one hand, while a few male tortoise-and-white can be seen at most of the important Cat shows, though they are still very rare.

But in overcoming this peculiarity in the Cat world, we have merely stumbled upon another: the old-fashioned orange male Cats all had white chins, and an endeavour was made to get rid of this blemish. It proved successful, and when we got rid of the white patch we got the orange queens. On the other hand, we have never reared a pure tortoise-shell male Cat; but by breeding with white, we get an occasional tortoise-and-white tom. Why should the presence of white affect the sex question, as at first sight it appears to do?

There is another colour peculiarity connected with these tricolour Cats. The self-tricolour is really a ticked or speckled mixture of black, red-orange, and yellow; but when we mix white in and produce the handsome tortoise-and- white, the four colours stand out distinctly, in small irregular blotches of colour. Why should the admixture of white cause the three primary colours to separate?

Very little is known regarding the correlation of colour with other qualities, but Messrs. Dewar and Finn ("Making of Species") draw attention to the association in Nature of black colouring with courage; yellow with a power to resist cold and damp; white with a lessened sensitiveness to cold; chestnut or bay with speed; and so on.

Of course, white (or albino) plants could not live anywhere that is to say, pure albino strains. But the many variegated types appear to be less fitted to resist cold or damp, being far less hardy than their green cousins. So in the vegetable world, the correlation with white appears to be the reverse of what it is with animals. But we must not forget that albinism is most prevalent when animals are in a state of domesticity protected from cold and damp, rather than exposed to them.

CHAPTER IV - PUSSY'S NAME

When we bear in mind the length of time that Puss has been a domestic friend of Man, we shall not be surprised to find, all over the world, a great similarity in the word used to describe her.

The English word Cat was in old Anglo-Saxon Catt; in Danish it is Kat, and in Swedish Katt; the Icelandic form is Kottr, Russian and Polish Kot, German Katze; in France we have Chat, in Italy Gatto, and in Spain and Portugal Gato. The Latin form was Catus, Armenian Kaz, Turkish Kedi (the most distinct form of all), and the Arabic was Qitt. The Burgundian form was Chai, Picardian Ca, Provencal Cat, and Catalonian Gat.

This striking similarity of sound in so many diverse languages is, without doubt, due to Pussy's strong hold upon the affections of mankind. She was a much-talked-of animal, and therefore the primitive name was passed on from one nation, and from one generation, to another. One writer suggests that "Puss" as a name is derived from PERS, and he considers this a proof that Persia is the native land of our four-footed friend.

Although we frequently use the word "Cat" as a term of reproach or opprobrium for a fellow human being, the word is really extremely popular (and always has been) in proverb, local phrase, or word. Sailors use it frequently among their technical words, as, for instance, the following (with many others): Cat-head, Cat-tackle, Cat-purchase, Cat-hole, Cat-back, Cat-fall, Cat-rope, Cat-beam, Cat-block, Cat- hook, Cat-stopper, etc. A "Cat" also was the name of a type of vessel, now obsolete, that was used for carrying coal and timber on the north-east coast of our island. It is still applied to a small rig of sailing boats with a single mast, set well forward.

The word is also used in a number of children's games, such as Tip-Cat, Blind Cat, Cat's Cradle, Cat in the Hole, Cat and Trap, Cat's Carriage, Puss in the Corner, to say nothing of the too-well-known Cat-o'-nine-tails, which has not quite such playful associations.

Then we find many well-known and oft-used phrases, such as "A Cat may look at a King"; "Care killed the Cat"; "Enough to make a Cat speak (or laugh)"; "See which way the Cat jumps"; "Fighting like Kilkenny Cats"; "Bell the Cat"; "Letting the Cat out of the bag"; "Not room enough to swing a Cat"; "Grinning like a Cheshire Cat"; "Making a Cat's-paw of one"; "Cat-and-Dog life"; "Raining Cats and Dogs"; "When the Cat's away"; "The harmless necessary Cat"; "How can the Cat help it?"; " Cats in gloves will never catch mice"; "The scalded Cat dreads cold water"; "Before the Cat can lick her ear"; and many others.

It may be explained that the phrase "Grinning like a Cheshire Cat" refers to the fact that at one time cheeses (in Cheshire) were moulded in the form of a grinning Cat.

Then again the word is often used in describing other animals, as, for instance, the "Flying Cat," or owl; "Sea-Cat," or wolf-fish; "Cat Fish," or cuttle-fish; "Civet- Cat"; "Musk-Cat," and "Polecat," none of which are Cats in reality; the "Cat Squirrel," or grey American variety; "Cat- Bird," or American thrush.

In popular botany also the word is freely used, and we find such familiar names as "Cat in Clover," or bird's-foot trefoil; "Cat-keys" for the fruit of the ash-tree; "Cat Sloe," or wild sloe; "Cat Succory," or wild succory; "Cat Thyme," a species of teucrium that causes sneezing; "Cat-trail," or great valerian, so called because Puss is very sensitive to the scent of valerian; "Cat-tree," or spindle-tree; "Cat Whin," or dog-rose; "Cat-wort," or mint; "Cat's Claw," or kidney vetch; "Cat's Grass," or "Cat's Milk," for the sun spurge; "Cat's Spear," or reed mace; "Catkin," a familiar name for the clustered hanging flowers of the hazel, willow, birch, poplar, pine, and others; "Cat's Eye," for the germander speedwell or forget-me-not; "Cat's Foot," for the ground-ivy or mountain cudweed; "Cat's Tail," commonly used for either the great mullein, the reed mace, the horse-tail (Equisetum), viper's bugloss, or a well-known form of grass; " Cat-brier," or smilax; "Cat- chop," for one of the curiously shaped family of Mesembryanthemum.

The Cat's Head is a large apple of the russet variety, while Cat-Face is used for a mark in wood.

There are many other popular ways in which Puss is used to give point to our words, as when we talk of a Cat-nap, meaning our usual "forty-winks" taken when sitting up; or a Cat-hole, in reference to a hole in a wall or a deep pool in a river. And most of us have heard the phrase "Catlap" in reference to tea or any other "weak" drinks.

The Cat's Eye is a well-known precious stone, a variety of chalcedonic quartz, very hard and transparent.

Catling is an old-fashioned word for kitten, and is also used to designate the smallest strings used on a musical instrument, though "catgut" (so called) is really made from the intestines of sheep. The word "Sea-catgut," in reference to seaweed, is not so well known, though the analogy is obvious.

The word "Catling" is also used for a small, narrow, double-edged surgical knife, while the Cat's Hair is a kind of tumour. Another very appropriate word is "Cat's Purr," to denote a certain thrill felt over the region of the heart in certain cases of heart disease.

The Cat's Paw (a well-known phrase) is also used in architecture, and we also come across "Cat-steps," as the name of certain parts of a gable roof, while a Cat-ladder is appropriate enough for a certain kind of ladder used on sloping roofs.

Cat Gold or Cat Silver are the names given to a brilliant variety of mica, while Cat Salt is a finely granulated form of common salt.

"Cat and Clay" is the curious name given to a mixture of straw and clay, which, when worked together, is used for building mud walls; while Cat-Brain is the word used for a soil consisting of rough clay mixed with stones.

The Cat-Call, as a method used by theatrical audiences to show their disapproval, is very well known, as also is the word "caterwaul."

"Cats," now more generally known as "Dogs," were, of course, useful articles upon which things could be put before a fire: they are generally used for the fire-irons.

In medieval times a Cat was a movable penthouse used to protect besiegers when approaching a hostile gateway or wall. The same name was applied to a double tripod on six legs, so placed that, in any possible position, it always rested steadily on three.

It is difficult to explain many of these uses of the name of our domestic friend, nor is it easy to explain why a mess of coarse meal, clay, etc., placed in dovecotes to allure stranger birds should be called Cat!

And why should the iron bar used for securing a door be called a Cat-band?

It is not for us to say.

CHAPTER V - THE CAT IN HISTORY

Outside Egypt the early history of the Cat is not very clear, and is, in many cases, merely fable. There is no proof that she was domesticated in Babylon or Assyria; while in Rome and Athens Puss appears to have been as badly treated as she was venerated in Egypt. Theocritus compares a lazy slave to a Cat; and Damocharis (a disciple of Agathias) comments as follows: "Detestable Cat, rival of homicidal dogs, thou art one of Actaeon's hounds. Thou, base Cat, thinkest only of partridges, while the mice play, regaling themselves upon the dainty food that thou disdainest."

Champfleury remarks: "I have gone through more than one museum of antiquities, examined a great number of publications, and questioned divers archaeologists, but I cannot discover that the Cat is represented upon any vase, medallion, or fresco of the epoch of the Decline and Fall."

According to Palliot ("La Vraye et parfaicte science des armoiries," Paris, 1664), the Romans frequently blazoned the Cat upon their shields. One company had a sea-green Cat on a white or silver shield; another carried a half-cat, red, on a buckler; while a third showed a red Cat with one eye and one ear.

But no Greek monument shows Puss. Homer, who tells the story of the hound Argus, does not mention the Cat. As a pretty plaything, Puss was brought from Africa to Europe before the Christian era, but the veneration shown by the Egyptians no longer surrounded her.

Among the Celtic people (according to Champfleury) the Cat was not a domestic animal. This he proves by a reference to the tumuli, in Europe and Northern Asia, by M. de Blainville, in which he found great quantities of the bones of the bovine and ovine species, together with those of deer, dogs, and swine; but there were no remains of the Cat.

In Turkey, as in most parts of the East, Cats have always been favourites, possibly because of the extreme affection shown for them by Mahomet. They may enter mosques, where they meet with caresses and every attention, and they are treated with as much consideration as the children.

In Cairo there is an endowment for lodging and feeding homeless Cats. This was founded as far back as the thirteenth century (about 1260) by El-Daher Beybars, Sultan of Egypt. There is a daily distribution of food principally refuse meat from the butchers and at the official hour all the terraces in the vicinity are crowded with Cats!

"There is an admirable permanence about Oriental customs which we of the West regard with envious scorn," says Agnes Repplier. "Seven centuries have elapsed since El-Daher Beybars atoned for the misdeeds of his fierce life by gentle charity. His gilded mosque has crumbled into ruins, the site of his orchard called Gheyt-el-Quottah, the Cat's Orchard is unknown; his legacy has lapsed into oblivion. Yet the Cats of Cairo receive their daily dole, no longer in memory of their benefactor, but in unconscious perpetuation of his bounty."

In Florence there is a cloister, situated near the Church of St. Lorenzo, which serves as a house of refuge for Cats.

A once popular tradition maintained that Cats were first introduced into Northern Europe by the Crusaders, but this is merely one of those numerous charming but fanciful morsels of history. Long before Peter the Hermit was preaching, Puss was sleeping by English firesides. The "Ancren Riwle" of 1205 denied to all nuns, even abbesses, the possession of any animals but Cats. As the old Saxon manuscript has it: "No best bute Katane" (no animal but one Cat). It has been suggested that this custom led to the traditional saying which associates Cats and old maids!

In Mill's "History of the Crusades" an account is given of the fete of Corpus Christi, held in Provence, when the finest male Cat of the district was wrapped up in white dressings, placed in a magnificent shrine, and exhibited to the people. Everyone knelt before the Cat, strewing flowers or offering incense. One wonders what Puss thought about it all.

It is somewhat painful to contrast the universal kindness to the Cat in the East with the ghastly barbarities practised in the so-called civilised West in the Middle Ages. It is humiliating to remember that it was not till the middle of the eighteenth century that the wife of the Marshal d'Armentieres obtained from her husband an order for the suppression, in Metz, of the custom of flinging live Cats into the bonfires kindled on the festival of St. John, June 24. For this ceremony the magistrates used to assemble with much solemnity in the public square, and place the cage containing the Cats on the funeral pile, to which they then set light!

The Turk, although he enjoys an unenviable reputation for cruelty, has never been, and is not now, cruel to animals. At Persian Banquets, troops of Cats glide in and out among the guests, offering no disturbance. In Siam and Burmah, Puss is treated with every consideration; and the Hungarian scientist, Vambery, is quoted by Miss Repplier as telling of a Buddhist convent, in eastern Thibet, where there were so many Cats, all sleek and fat, that he asked the pious inmates why they thought it necessary to keep such a "feline colony."

"All things have their uses," was the serene reply.

The god of Egypt, the plaything of Rome, became in the West a symbol of witchcraft and evil. Many extraordinary cases are recorded of witch trials, in which poor Puss shared the tragic fate of her mistress, generally by burning.

One result of this is seen in the scarce use of the graceful little animal in the church and cathedral decorations of those centuries of barbaric Superstition. Two droll Cats can be seen in the old minster in the Isle of Thanet. San Georgio Maggiore, in Venice, shows several, but these carvings were done by Albert de Brule at the end of the sixteenth century, when superstition was losing its grip on the popular mind.

The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth the "good" Queen who was responsible for so many deaths by fire was disgraced by the burning of a wicker-work "Pope", the interior of which was filled with live Cats. When these unfortunate little animals screamed in terror, while being thus burnt to death, the spectators were delighted, saying that it was the language of the devils who had possession of the body of the holy Father.

So much for Humanity a couple of hundred years ago!

The dull-witted country folk of England roasted Puss alive, because they believed that such an act brought good luck to the house; in Scotland they spitted her before a slow fire. Cat-worrying was, for centuries, as recognised a "sport" as cock-fighting.

It is in France that we find the first signs of the modern turn of the wheel that has restored Puss to the place of favour that she has never lost in the East. The French country houses built in the seventeenth century were all furnished with "chatieres" or little openings cut in the doors for the accommodation of Puss, who was, in consequence, able to come and go at her own sweet will.

Probably we have all heard of the amusing case of the absent-minded philosopher and Cat-lover, who had two holes cut in the door, one for the mother-cat and a smaller one for the kittens!

Many prominent Frenchmen of the last two centuries were great lovers of Puss. Richelieu delighted in the gambols of kittens, and found them his only relief from his natural melancholy; but he gave them away when they grew up!

Mazarin's love for Cats was more real and thorough, and, like Cardinal Wolsey, he made actual companions of them.

Frangois de Moncrif wrote a series of letters in praise of Cats. In his verses we read of his many Cat friends: Marmalain, Tata, Dom Gris, Menine, Grisette, and others. After his election to the French Academy, he was chaffed about his " Histoire des Chats", and withdrew the book from circulation.

La Fontaine, Madame la Duchesse de Bouillon, and many others could be named from this period. The Pontiff, Leo XII., made a most intimate companion of his Cat, Micetto, who was born in the Vatican, in the loggia of Raphael. And many Popes, besides Leo, have been devotedly attached to their Cats, "Gregory XV. cherishing his pets with exceeding fondness, while Pius IX so delighted in his Cat that he shared his meals with this little companion, whose dish was placed at his feet and filled by his kind old hands." Victor Hugo was blessed in his feline society. All his Cats were serene, quiet, and dignified; and one of his friends, a M. Mery, remarked: "God made the Cat that Man might have the pleasure of caressing a tiger."

"Sainte-Beuve's Cat," says Agnes Repplier, "would sit for hours on his master's table, watching that swift and steady pen travelling down the page and sometimes encouraging it with a soft approving pat. He would step gently backward and forward over the loose sheets; the delight which all Cats take in the contact of crisp paper being doubtless enhanced in his case by appreciation of the courseries with which those sheets were covered."

In all probability, however, it was not from appreciation of the courseries, but the fact that his master's hand had left its peculiar personality on the paper.

The "Black and White Dynasties" of Cats that ruled over Theophile Gautier's home have been mentioned in every book upon Cats. We need only refer to that amusing story of the big grey Cat that flew at and bit Mme. Gautier's legs when she scolded her son!

But we cannot refrain from once again putting on record a few of Gautier's references to his pets. "It is a difficult matter to gain the affection of a Cat. He will be your friend, if he finds you worthy of friendship, but not your slave. He lies for long evenings on your knee, purring contentedly, and forsaking for you the agreeable society of his kind. Sometimes he sits at your feet, looking into your face with an expression so gentle and caressing that the depth of his gaze startles you. Who can believe that there is no soul behind those luminous eyes!"

In spite of the frequency with which we come across Puss in English life, it was not until comparatively recent years that she was more than tolerated.

There are a few isolated cases to the contrary before the eighteenth century, but they are the exceptions that prove the rule. The most striking, and best known, is the Cat of Cardinal Wolsey, who shared his master's seat in Council. There is also the faithful Cat of the unfortunate Duke of Norfolk, who was imprisoned by "good" Queen Bess from jealousy of her fair cousin. This loyal little Puss actually made her way down a chimney to the Duke's room, and was thereafter permitted to share his captivity.

Lord Westmorland's Cat also freely shared her master's confinement, while Sir Henry Wyatt's furry friend followed him to the Tower.

In more recent days Sir Walter Scott inspired the most steadfast affection in every animal he met; while at Naples he visited the

Archbishop of Taranto, another Cat-lover, and promptly fell in love with all the pets. These animals were also referred to by Sir Henry Holland, who remarked that he scarcely knew which he admired the more, the prelate or his Cats!

It is worth noting that the return of poor Puss to a position of favouritism was largely due to the Church, a strange fact when one remembers the ghastly years of religious persecution and burning to which Cats had been subjected in the civilised West.

We have mentioned three or more of the Popes; while Richelieu, Mazarin, and Wolsey were not the only Cardinals who delighted in the companionship of their Cats. Of Bishop Thirlwall a story is told that might equally be quoted of many others. A visitor, who observed that the venerable Bishop looked wearied, asked him why he did not use his easy chair. "It is already occupied," said the Bishop, pointing to a big grey Cat fast asleep on the cushion.

Canon Liddon was the proud possessor of many Cats, as also Archbishop Whately.

Indeed, turn where we may, we see the same consoling picture: Puss restored to her old position of comfort and friendship, valued for her quiet sympathy, for her peace-loving ways. Southey, Sterne, Charles Lamb, Christopher North, Shelley, Johnson, Lord Byron, Scott, Matthew Arnold, Canning, Marshal Turenne, Lord Heathfield, Charlotte and Emily Bronte, Miss Edgeworth, Wordsworth, Carlyle. "Chosen companion of students, valued friend of careful housewives, and genius of the quiet fireside, she gives to Man, in return for his protection, nothing but her gracious presence by his hearth. The serenity of her habitual attitudes, her enjoyment of cushioned ease and warmth, have endeared her naturally to men of thought rather than to men of action. The race of authors have found in Pussy's gentle presence a balm for their sensitive souls: to understand the character of a Cat, to respect her independence, to be charmed by her gentle moods, to appreciate her intelligence, and to love her steadfastly!" (Agnes Repplier: "The Fireside Sphinx."),

CHAPTER VI SUPERSTITIONS ABOUT CATS

Black Cats and skulls have always been associated with magic and witchcraft, the most powerful weapon for spells being the skull of a black Cat that had been fed on human flesh. Yet in the earliest years of the ancient Egyptians Puss was considered sacred, and had her special goddess; towns were dedicated to her service, and at death she was as carefully embalmed as her master. It is, indeed, almost impossible to fix a time when the Cat was not a domesticated animal and a companion of Man, and there can be no doubt but that she responds more easily and more fully to Man's mood than any other animal, even the dog. It is true that she is more independent than the dog, and in a sense, therefore, less companionable; and, of course, one cannot take a Cat out for a walk as one can a dog. But this very independence of habit proves Puss to be the possessor of a stronger personality, and her faithfulness to those she loves is as great as, or greater than, the dog's. Her vocabulary of sounds is much more varied, and, as a rule, Cats are fond of music, which shows that their sensibility to sound vibrations is similar to that of Man.

Under the Egyptians the male Cat was likened to the sun, and the female to the moon, and they held a very enviable position. In case of a fire, Puss was the first to be saved. But for some unexplainable reason the Cat passed from this state of semi-worship. So many ancient Eastern "fairy-tales" show Puss triumphant over her enemies through her cunning and cleverness, and so presumably she gradually became associated with magic and witchcraft, a curious perversion of her original position.

One can safely state that no other animal has suffered so much through association with superstition as the Cat. Often, as the companion of a witch, poor Puss perished in the flames with her mistress. In China people sometimes reverence the ghost of a Cat. They hang poor Puss, and then for seven weeks indulge in occasional prayer and fasting in her honour; this is supposed to bring prosperity. But if a neighbour whips the dead Cat, the luck is broken.

THE INFLUENCE OF THE BLACK

A black Cat in many districts is supposed, even to-day, to bring good luck; whereas in other parts a Cat is always thrown into a new house before anyone enters, the idea being that the first to cross the threshold alive will be the first to cross it dead. In Cornwall it is said that sore eyes can be cured by passing the tail of a black Cat nine times over the afflicted eye. In other places, but not, I believe, in this country, blood from the tail of a Cat is believed to hold great healing properties. Another curious Chinese superstition is the hanging of hairs of Cats and dogs for eleven days outside the door of the room where a mother is lying. This insures that the baby will not be frightened by these animals.

We all know that a Cat is supposed to possess nine lives, yet this cannot be on account of any special vitality or power of endurance. Puss is not really long-lived, and if taken ill makes hardly any effort to assist recovery. The saying no doubt originated from her happy knack of twisting over while in the air and thus always alighting on her feet. Science is not able to explain this phenomenon satisfactorily; some authorities actually claim that the tail is used as a rudder; but they do not tell us why, if this be the case, all tailed animals have not the same power.

In Scotland and the North of England it is considered unlucky for a Cat to die in the house, and Puss is generally removed to an outhouse when ill, which, perhaps, is unlucky for the Cat. In Devonshire it is believed that a Cat will not remain in a house that contains a corpse, and stories are told of disappearance on the death of an inmate and reappearance after the funeral. Yet many of us know cases of a faithful Cat refusing to leave the bed of her dead master, ignoring food and dying, practically of a broken heart, on the bed. But Puss certainly does not like an upset in the house, and this probably explains the mysterious disappearance of the Devonshire Cats at such times of stress and unrest.

Sailors are notoriously superstitious with regard to Cats. When Puss becomes unusually frolicsome, they say it foretells stormy weather. At Scarborough, in former days, the fish-wives believed that by keeping a black Cat they insured the safety of their husbands when at sea. In Russia a Cat is put into a new cradle in order to drive away all evil spirits from the infant. Another superstition is that if a young maiden is fond of Cats she will have a sweet-tempered husband. In all probability I fancy the husband would have no better time because of it. Some people believe that a Cat, to be a good mouser, must itself have been stolen. In Sicily it is held to be a bad sign if the Cat mews while the rosary is being counted.

"A LUCKY SNEEZE"

If Puss sneezes on the bridal morn, it presages " good luck" to the fortunate bride!

Amongst others, Hindus believe in the transmigration of the soulfrom humans to animals and it is a remarkable fact that, owing to some curious coincidences noticed on the day of the death of a governor of Bombay, the Hindu soldiers believed that his soul had passed into the body of one of the household Cats. Whenever Puss quitted the house, between certain hours, she was duly saluted in full military form. This observance was honoured for many years by the Sepoys of various regiments.

It has been seriously claimed by Professor Garibaldi that Cats have a distinct language comprising several hundred words, and it is admitted by most leading physiologists that the throat and vocal organs of a Cat very closely resemble those of man. The brain, too, is notoriously similar to the human, and differs only in weight and size. But all this was not known to the ancients, when witches were hanged or burned, especially in Scotland. A famous Scotch witch, Isobel Gowdie, burnt in 1662, actually confessed that she changed to a Cat at night and roamed the neighbourhood learning secrets. Joan Paterson, hanged at Wapping in 1652 for plaguing her neighbours under the semblance of a black Cat, was another so-called witch.

Margaret Gilbert and Margaret Olson, two women of Caithness, were accused of bewitching the family of a stonemason named Montgomerie by means of her Cats. It was seriously stated that these Cats entered the man's kitchen at night, though the place was bolted and barred, and that if cut in two with a hatchet, they disappeared only to return at a more favourable moment. Another witch confessed that she rubbed her naked body all over with a special black ointment that turned her into a Cat!

TIMES OF CRUEL PERSECUTION

The "Church Booke of Bottesford" gives the record of an extraordinary witch trial, where it is stated that the Earl and Countess of Rutland and their children had been bewitched by one Joan Flower and her two daughters, Margaret and Phyllis, by the aid of a black Cat called Rutterkin. The three women were hanged. A learned jurist, by name Keisner, collected the evidence given at a large number of witch trials, and showed that the Prince of Darkness appeared to his followers some sixty times as a cavalier, never as a woman, two hundred and fifteen times as a he-goat, but more than nine hundred times as a black Cat. And so it came to pass that poor Puss was cruelly persecuted through the dark Middle Ages.

In the reign of Queen Mary, it was a custom among those who hated Popery to shave the crown of a black Cat's head, in imitation of the monk or friar. At the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth, as related, a wickerwork Pope was carried through the streets, the figure being filled with struggling, screaming Cats! Spectators were delighted at this suggestion of the worthy Father filled with devils!

Yet, curiously enough, Puss has always been the companion of the learned. Petrarch had his pet Cats embalmed; Cardinal Wolsey had his Cat by his side when he gave audiences or received princes; Rousseau loved Cats; Sir Isaac Newton cut two holes in his door for his Cats, a large one for the mother-cat and a small one for her kittens! Dr. Johnson taught his pet to eat oysters; Henry James wrote his books with his Cat sitting on his shoulder; Paul De Koch, the French novelist, had thirty pets, and Cardinal Richelieu twenty. De Musset wrote verses to his Cats, and Edgar Allan Poe was a Cat-lover. The Pope gave Chateaubriand a present of a Cat, knowing that nothing would please him better; while Mahomet cut the sleeve from his garment rather than disturb a pet Cat that was sleeping thereon. Horace Walpole, Robert Southey, Shakespeare, Milton, Byron, Moore, Talleyrand, Benjamin Franklin, Julius Caesar, Thomas Gray, Sir Walter Ralegh, Lord Chesterfield, and many other great men, were all Cat-lovers.

Pussy's rapid progress in esteem appears to have begun in France, largely aided by Cardinal Richelieu. In the brilliant Court of Louis XIV., Puss enlarged her social triumphs, and thus from the absolute worship of the ancient Egyptians she passed through a period of stress and persecution (too ghastly to detail here) as the familiar of witches and devils, until she at last has secured a well-deserved and enduring niche in nearly every household, in nearly every home.

CHAPTER VII - MENTALITY IN CATS

Louis Robinson, in his interesting book, "Wild Traits in Tame Animals," suggests that the strong reasoning powers in Man were developed in self-protection, because his sense of smell is so small!

Just at first this appears to be rather far-fetched, but his argument is that Man comes from a tree-dwelling, fruit-eating ancestor, so that in his wilder years he did not need to track his food, or protect himself from enemies, by means of scent. Whereas the dog (or the wolf) gallops blindly and without thought along the tainted line left by the feet of his quarry, the primeval hunter had to infer, from a hundred small signs, what had passed that way. A broken twig, a shaking leaf, a shifted stone, all these told their tale, and so Man developed his powers of reasoning as a means of self-preservation.

This is the reason why "mental furniture" in dogs and men differs so essentially: "If you examine a human brain, you will find that the parts which first receive impressions from the nerves of smell are very small and rudimentary; but in the dog these olfactory lobes are large and full of ganglia, which are connected by innumerable telegraphic fibres with the main hemispheres of the brain. Hence most of the information we gather comes in through the channels of the other senses, and our ideas of external things are but little based upon the presentation of them offered by the organ of smell. The dog, on the contrary, forms his notion of the outside world more from impressions gathered in this way than in any other. He may be said, indeed, to think through his nose."

Now, in the Cat, the sense of smell is no doubt stronger than in Man, but at best it is only very feeble. Unlike the dog, Puss has only a limited lung capacity, and therefore she cannot secure her supper by running it down, but instead she crouches out of sight and springs upon her prey as it comes towards her. In other words, she depends more upon her splendid eyesight than upon her sense of smell.

Now the eyes of a Cat are remarkable for their extreme adaptability. It is, of course, quite false to say that Puss can "see in the dark"; such a remarkable optical feat is quite impossible. But certain it is that she can see in the dusk long after Man's power of vision fails him. Many people think that the Cat can see what is invisible to us, and it is quite a common thing to see a Cat obviously watching something that is passing across the room, unseen by ourselves. But whether Puss is watching a spook or a small insect is quite another question.

Grant Allen was probably the first to suggest that our appreciation of bright colours (and therefore of the splendours of the flower garden or of the sunset tints) might be owing to the arboreous and frugivorous habits of our very early ancestors, to whom the sight of red or golden-ripe fruit was naturally a keen pleasure, because it insured a good meal!

Poor "Little Mary", what a part you have played in the world's history and development!

This question of the sense of smell brings up another interesting point: the dog, dependent more upon scent than sound, frequently has drooping ears. Not so Man and the Cat, to whom sound is of far more importance. We may also note that the dog's call or cry is shrill, piercing, and far-carrying, whereas Pussy's note is soft and gentle as herself, except, of course, in the case of the harsh mating cry of the male.

Cats prefer deep tones, either in the voice of their masters or in music (of which, by-the-bye, they are very fond), as in the case of a stirring march tune, with a strong bass part. Many instances are on record of Cats sitting on the shoulders of a singer or a violinist. Theophile Gautier, referring to one of his pets, says: "She also had a taste for music. Seated on a pile of scores, she would listen attentively and with evident signs of pleasure to the ladies who came to our house to sing. But shrill notes made her nervous, and when the high A occurred, she never failed to shut the mouth of the singer with her paw."

Wotherspoon ("Knowledge") says very truly that "between the dawning consciousness of the infant and the full intellect of the adult, there is the widest possible difference of degree, but no difference of kind. We pass from one to the other by an unbroken series of gradations, and at no stage can we positively say, Here intelligence begins.'" "Practically all scientific men agree that instinct is stronger in animals than in human beings, and to a very great extent delays the full development of reason or intelligence. But that is a very different thing to denying any intelligence at all to other animals than Man. The same material is there, but when human beings neglected the use of their protective instincts, their intelligence rapidly developed.

Necessity has always been the mother of invention, and as Man strayed farther and farther from the simple primitive " instinctive" life, he gradually lost the keenness of his senses; and without that keenness the primitive instincts are very largely useless.

People are very often confused by the word "instincts" and perhaps it would be wise to give here the definition offered by Professor Romanes in his " Natural History of Instinct"; "Instinctive actions depend upon knowledge anterior to individual experience. They are actions which are performed by all individuals of the same species when placed in similar circumstances." In other words, instinct is inherited memory, automatic actions due to the inherited experience of countless previous generations of each species.

Thus in our tests of intelligence in animals, we must always bear in mind that the entirely unreal conditions seriously affect the animals experimented upon. Thus Thorndike spent many months putting dogs and Cats into boxes and watching how they released themselves. His conclusion was that it was purely by accident that they clawed around vaguely and indefinitely and so chanced upon the means of release. But his elaborate experiments were merely a waste of time, as obviously the poor animals were dominated by the one idea, the utter strangeness of their surroundings.

Upon this feeble basis he built his conclusion that the numerous recorded cases of Cats (not dogs) opening doors (by moving the latch or otherwise) were also due to accident. But all these authenticated instances occurred in the animal's normal home surroundings, when the intellect could peacefully work, even if slowly.

Then again, Man's artificial surroundings must often puzzle an animal, as, for instance, when a man undresses and slips into the sea, and then calls his dog. The animal, it has been recorded, at first fails to recognise his master when undressed, but wonders where the familiar voice comes from. We get a similar condition when sheep are shorn of their wool: the young lambs for some time fail to recognise the ewes.

It certainly appears as if animals inherit some extremely complicated instincts, as in the case of nest-building by birds, the vast majority of whom cannot possibly have been taught by their parents; or in the case of the cuckoo, who never by any chance imitates other birds, but invariably lays its egg in an alien nest.

But these acts are obviously instinctive inherited memories, in fact and though the greater part of the life of most wild animals is thus governed and ordered, it seems impossible to get away from the fact that the power of intellect is there as well, much less in degree than the mentality of Man, but the same in tendency and in action.