THE CAT IN HISTORY, LEGEND, AND ART

LONDON: ELLIOT STOCK

61 & 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.

1909

To my dear father and to the memory of my dear mother I lovingly dedicate the following pages.

PREFACE

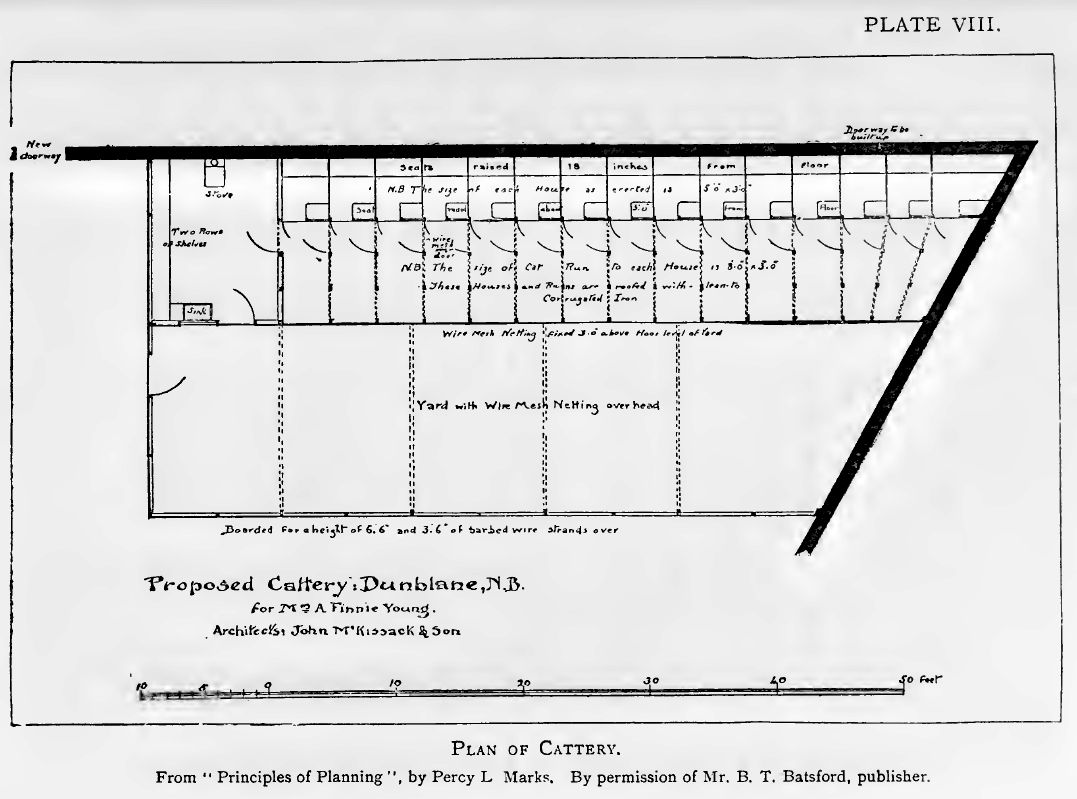

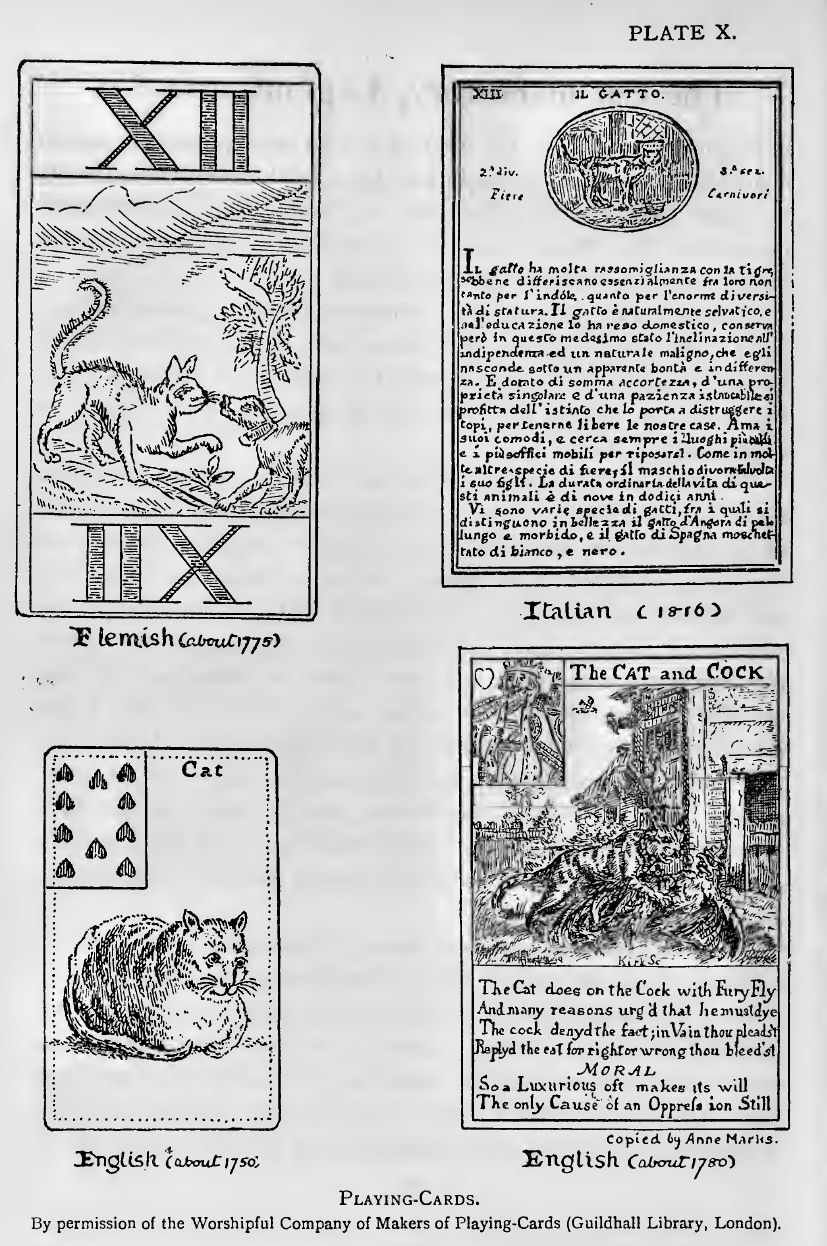

The Author desires to express her thanks to Dr. E. A. T. Wallis Budge, M.A., Litt.D., D.Lit., Keeper of the Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities, British Museum, for permission to use extracts from his publications, “ The Book of the Dead: Papyrus of Ani ” and “Facsimiles of the Papyrus of Hunefer ”; to Professor W. M. Flinders Petrie, D.C.L., F.R.S., for the use of photographs taken by him in Italian museums, and to him and the College for access to objects in the Egyptology Museum, University College, London; to the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing-Cards for permission to copy various cards on which the cat is figured, and for the facilities granted by the representative of the Company, and by the officials of the Guildhall Library of the Corporation of the City of London; similarly to the different departments of the British Museum. Her thanks are also rendered to her brother, Mr. Percy L. Marks, and to Mr. B. T. Batsford, the publisher of his book, “The Principles of Planning”, for permission to use the “Plan of Cattery” appearing in the second edition of that work. The Author trusts that all publishers and authors to whom she is indebted for various old tales, legends, superstitions, etc., will accept her grateful thanks.

ANNE MARKS.

10, Matheson Road,

West Kensington, W.

September, 1909.

CONTENTS

Chapter 1 - The Cat in History

Chapter 2 - The Cat in Mythology and Legend

Chapter 3 - The Cat and Superstition

Chapter 4 - Some Facts about the Cat in Natural History, and an Account of the Different Varieties

Chapter 5 - The Cat in Art

Chapter 6 - The Cat in Anecdote, Poetry, Proverb, and Nursery Rhyme

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

The illustrations, from various sources, have been specially drawn by the Author

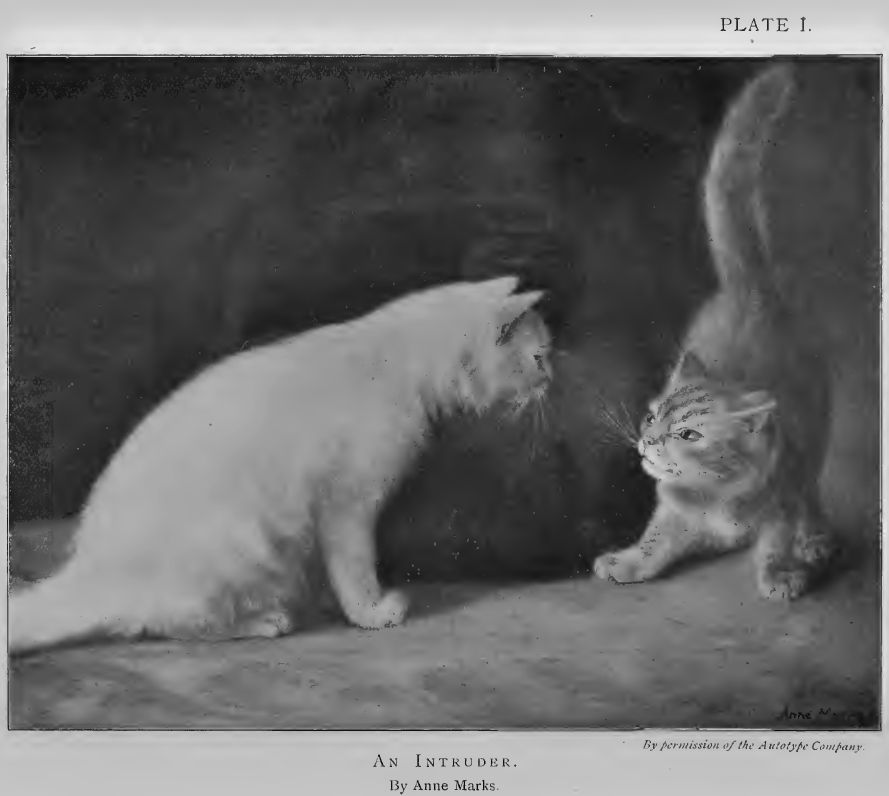

I. An Intruder - By Anne Marks. By permission of the Autotype Company.

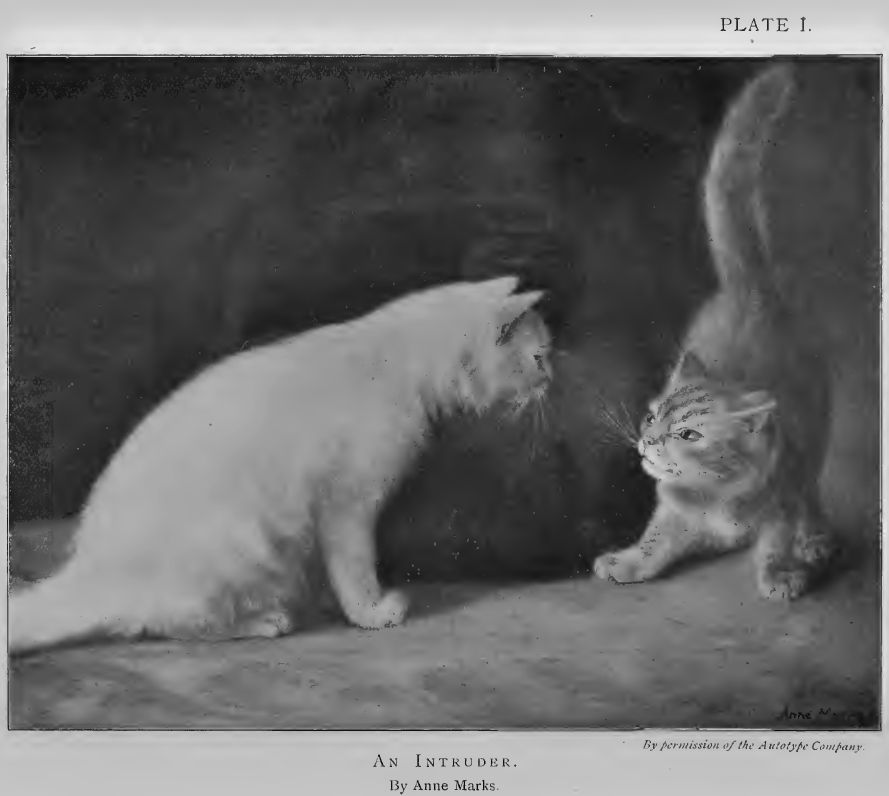

II. “A Miscellany” - Pictures and portraits by Anne Marks.

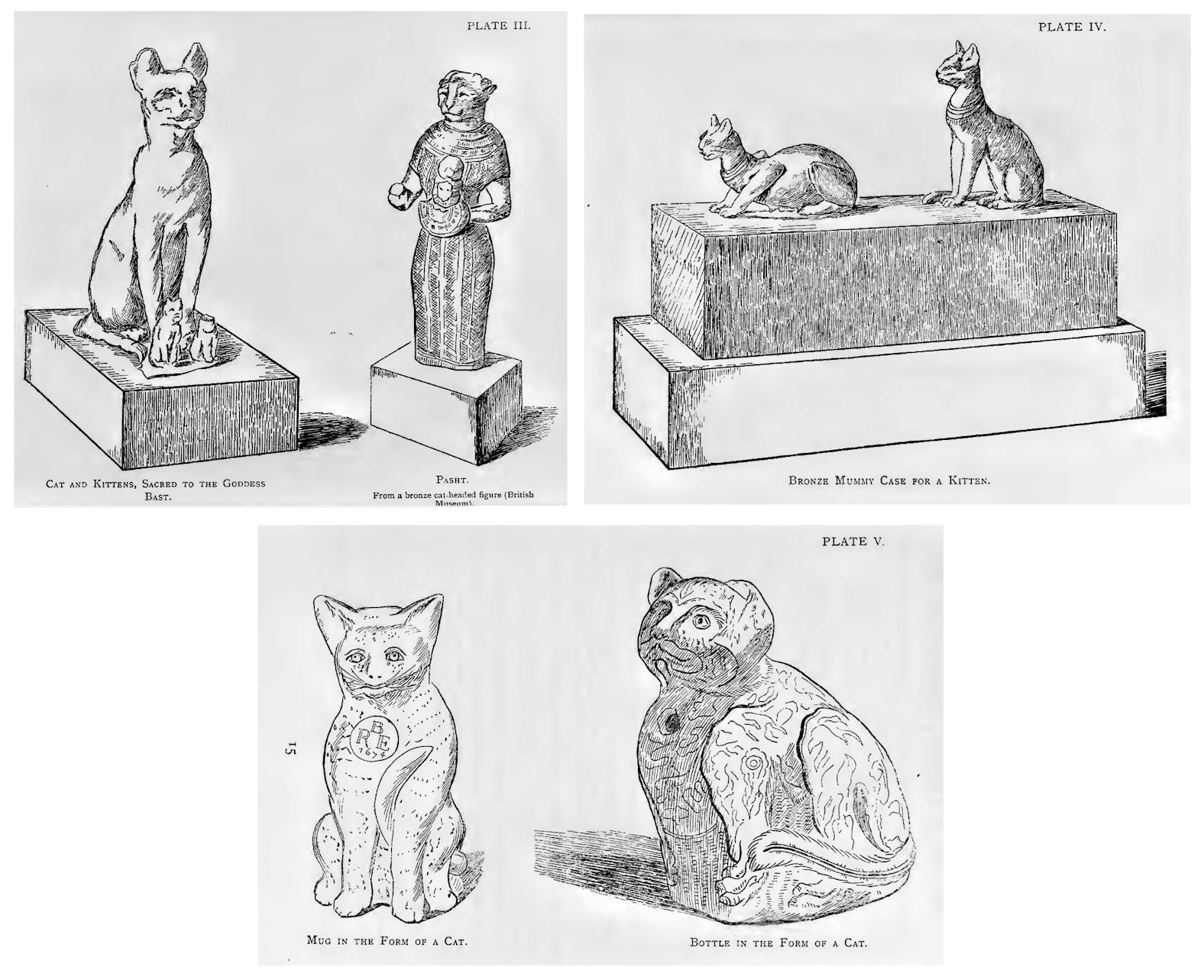

III. Cat and Kittens, Sacred to the Goddess Bast - From bronze model (British Museum).

Pasht - From a bronze cat-headed figure (British Museum).

IV. Bronze Mummy Case for a Kitten - British Museum.

V. Mug in the Form of a Cat - In Lambeth delft. From the Willett Collection (British Museum).

Bottle in the Form of a Cat - Persian, sixteenth or seventeenth century. In glazed earthenware (Victoria and Albert Museum).

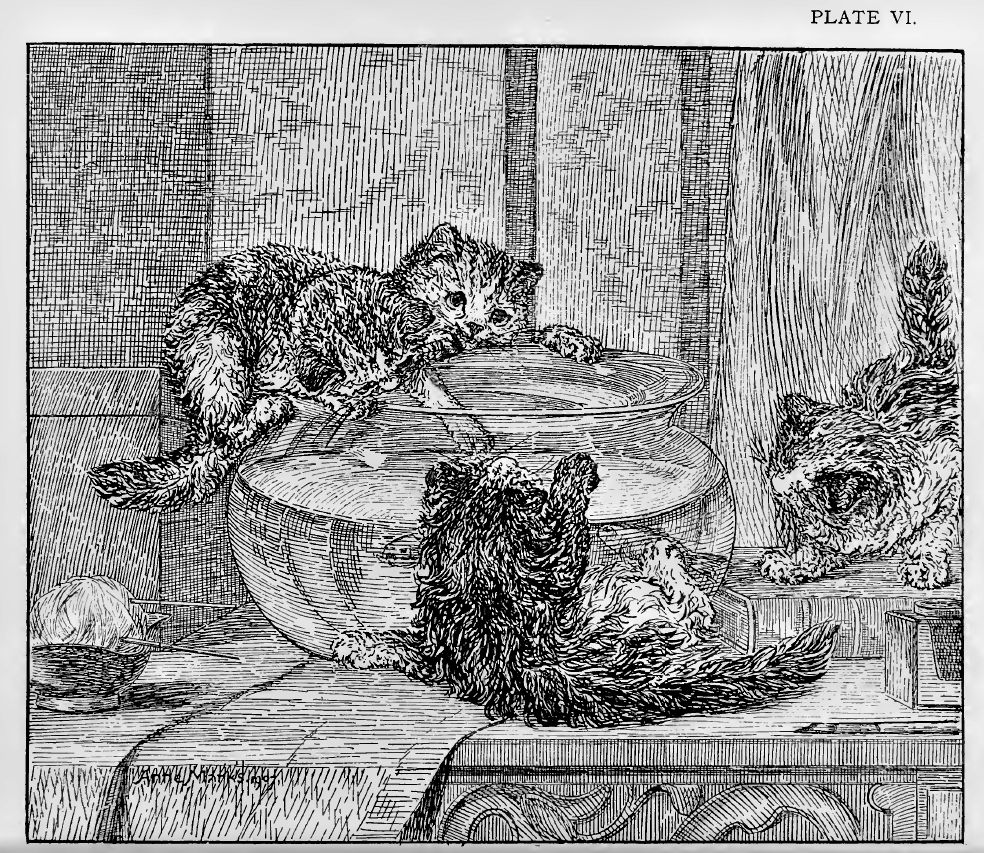

VI. “To-morrow will be Friday” - From the original oil-painting by Anne Marks.

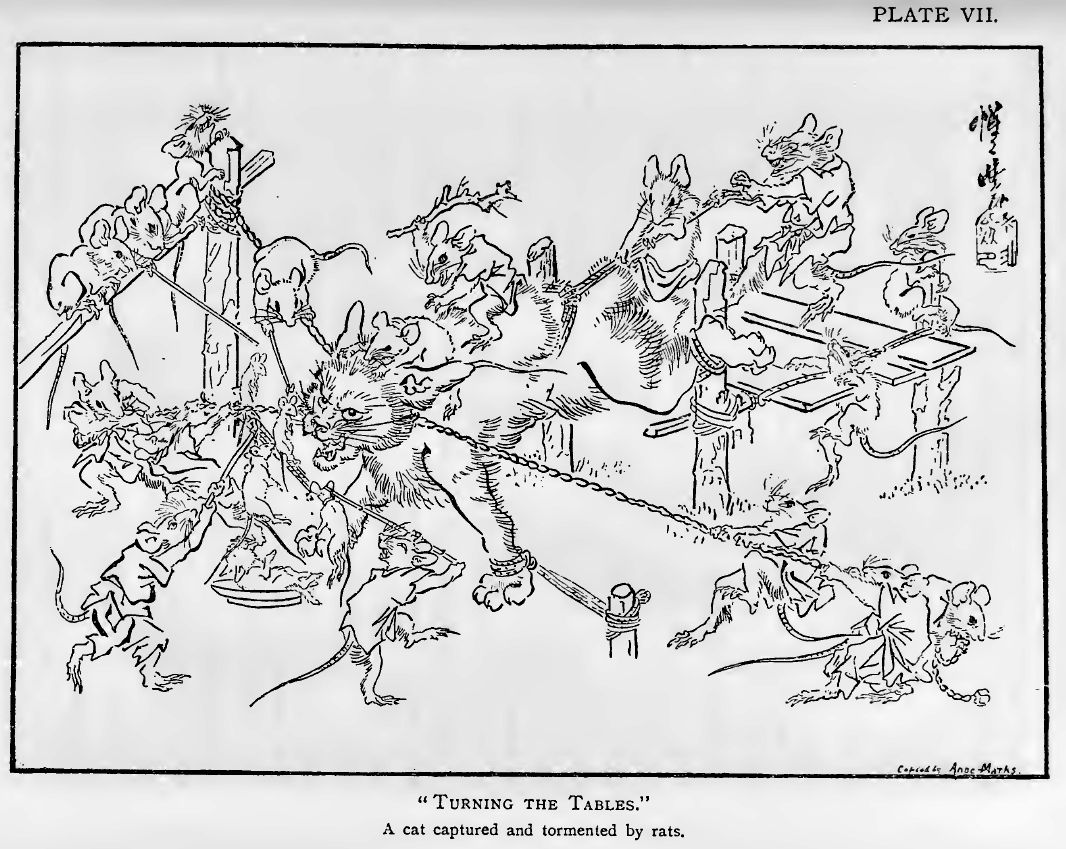

VII. “Turning the Tables” - A cat captured and tormented by rats. From a painting by Kio-Sai, 1879, now in the Print Room, British Museum.

VIII. Plan of Cattery - From Percy L. Marks’s " Principles of Planning,” second edition. By permission of Mr. B. T. Batsford, publisher.

IX. “Mischief” - From the original oil-painting by Anne Marks.

X. Playing-Cards - By permission of the Worshipful Company of Makers of Playing-Cards (Guildhall Library, London).

XI. “ What we should Weigh when in Health ” - From the original oil-painting by Anne Marks.

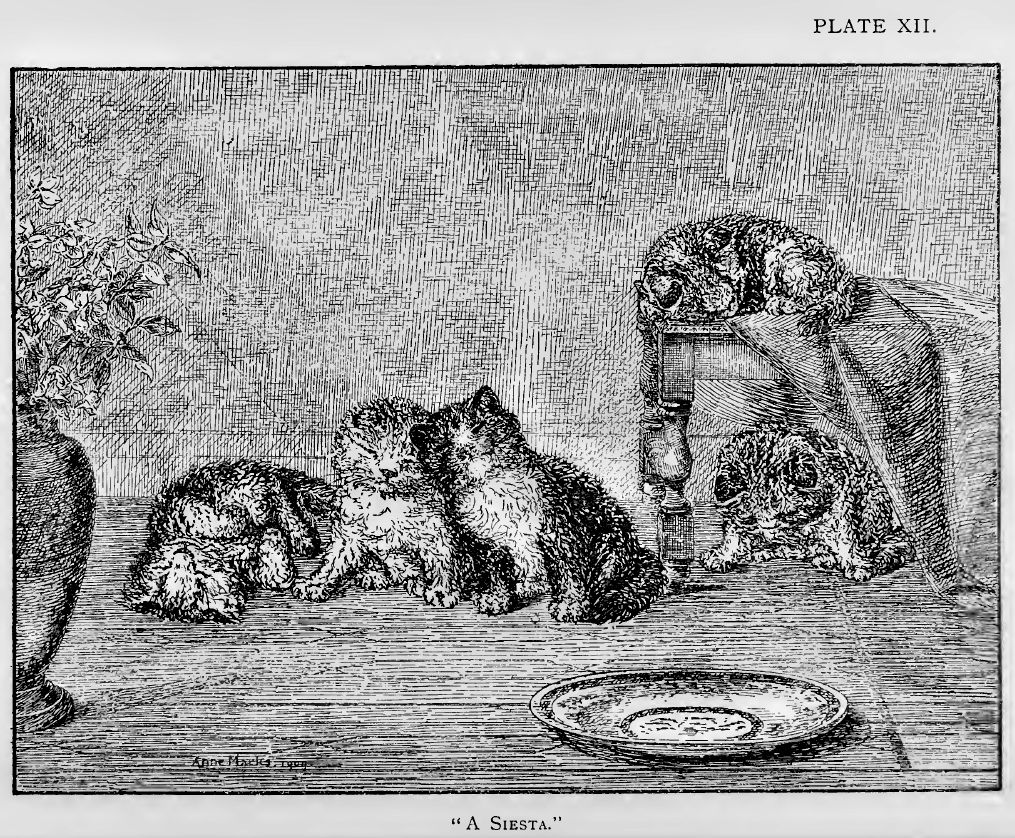

XII. “A Siesta” - From the original oil-painting by Anne Marks.

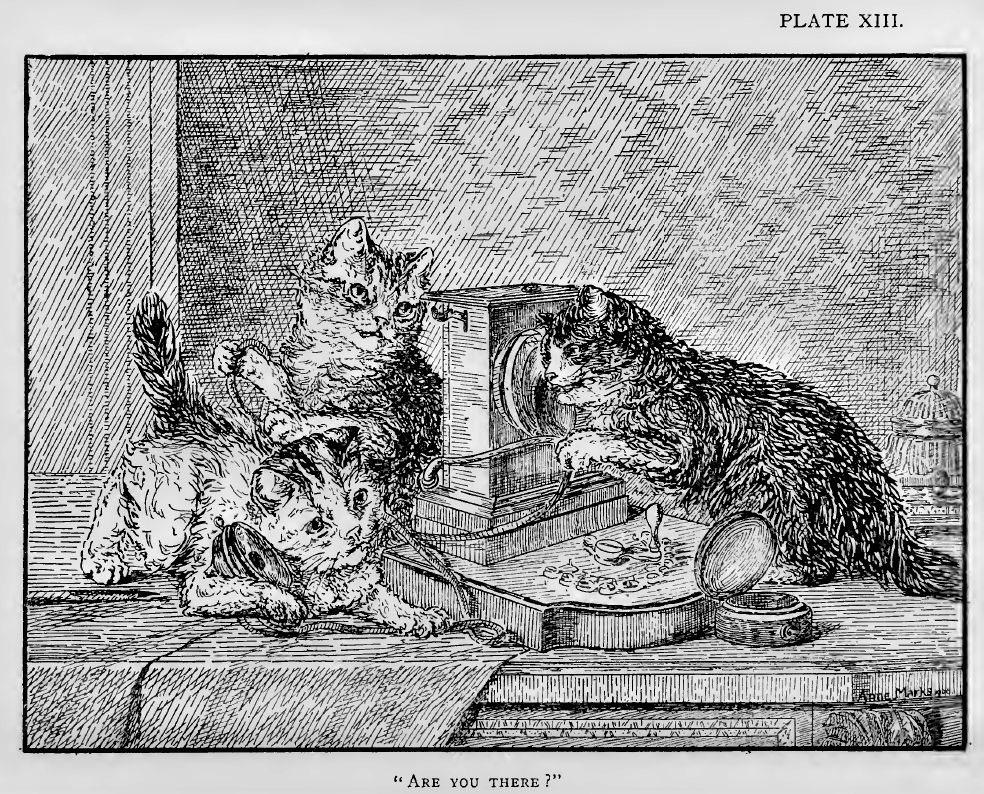

XIII. “Are you there?” - From the original oil-painting by Anne Marks.

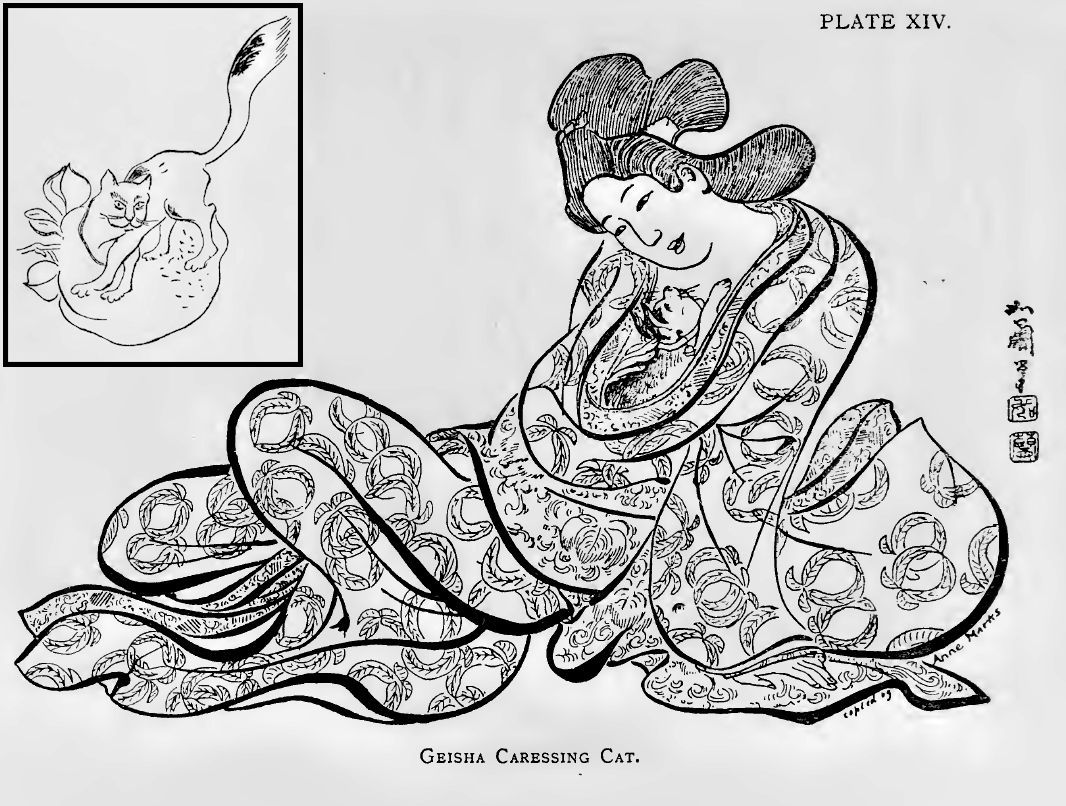

XIV. Geisha Caressing Cat - From a Japanese painting on silk by Joran, eighteenth century (Print Room, British Museum).

FIGURES.

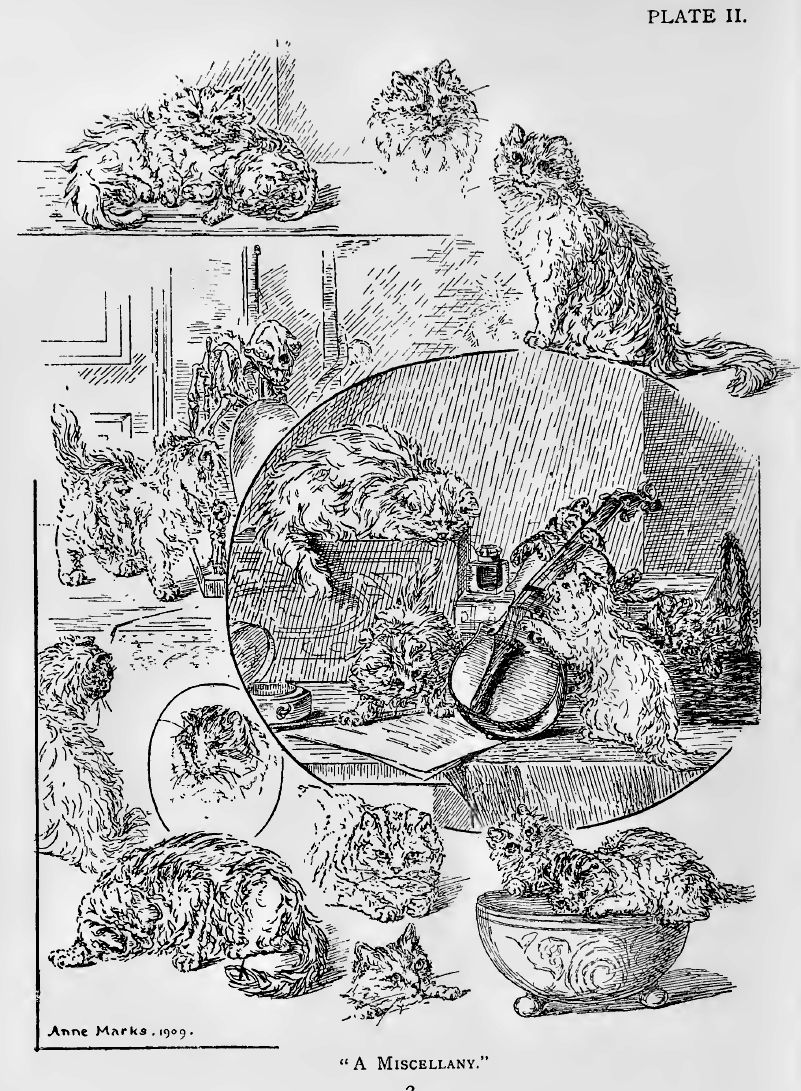

1. Osorkon II. (XXII. Dynasty, circa 866 b.c.) in a Shrine with the Goddess Bast and Officials - Inscribed granite slab (British Museum) from the Temple at Bubastis.

2. Cat and Three Kittens in Blue Glaze - From Professor W. M. Flinders Petrie’s Loan Collection (University College, London).

3. Bast, holding a Sistrum - British Museum.

4. Mummy Cat - British Museum.

5. Effigy of a Cat - At the museum at Turin. From a photograph by Professor W. M. Flinders Petrie, D.C.L., F.R.S. (by permission).

6. From the Papyrus of Ani - From “ The Book of the Dead,” by E. A. T. Wallis Budge, M.A., Litt.D.

7. Two Gods and a Cat-headed God, holding Knives (Papyrus of Hunefer) - From “The Book of the Dead: Facsimiles,” by E. A. T. Wallis Budge, M.A., Litt.D.

Cat Cutting Off Head of Serpent (Papyrus of Hunefer) - From “The Book of the Dead: Facsimiles,” by E. A. T. Wallis Budge, M.A., Litt.D.

8 . Hebrew Verse - From the Jewish Passover Service (with English translation).

9. Bast, the Cat Goddess of the City of Bubastis - From bronze model (British Museum).

10. Cat Suckling Kittens - Emblem of Bast from Bubastis (British Museum).

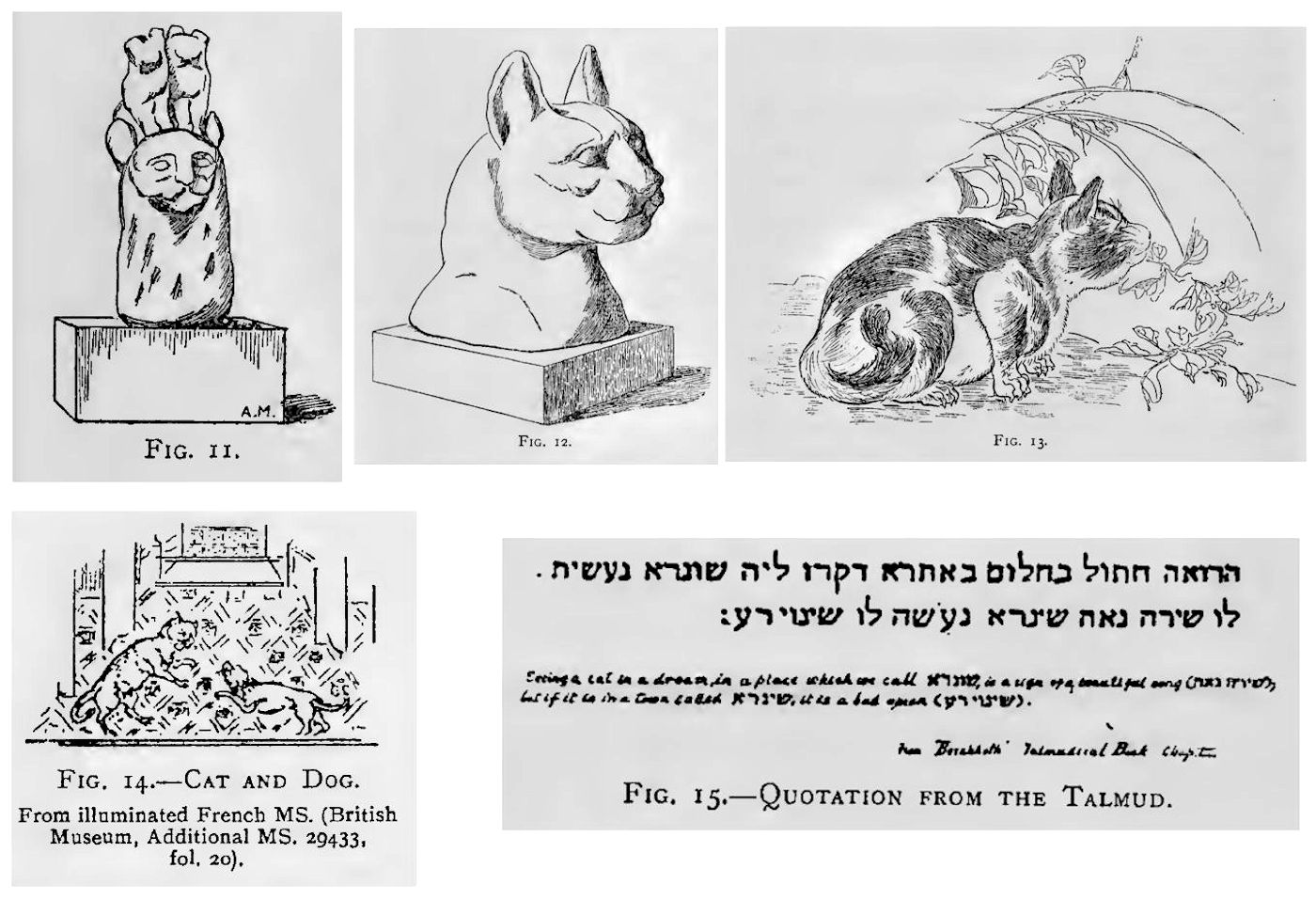

11. Head of Sekhet (Bast) with Two Kittens - British Museum.

12. Bronze Head of a Cat - From Edward’s Collection, University College, London.

13. Cat and Flowers - From a Japanese painting, seventeenth century (Print Room, British Museum).

14. Cat and Dog - From illuminated French manuscript (British Museum, Additional MS., 29433, folio 20).

15. Quotation from the Talmud - From “ Berakhoth," Talmudical book, chap. ix.

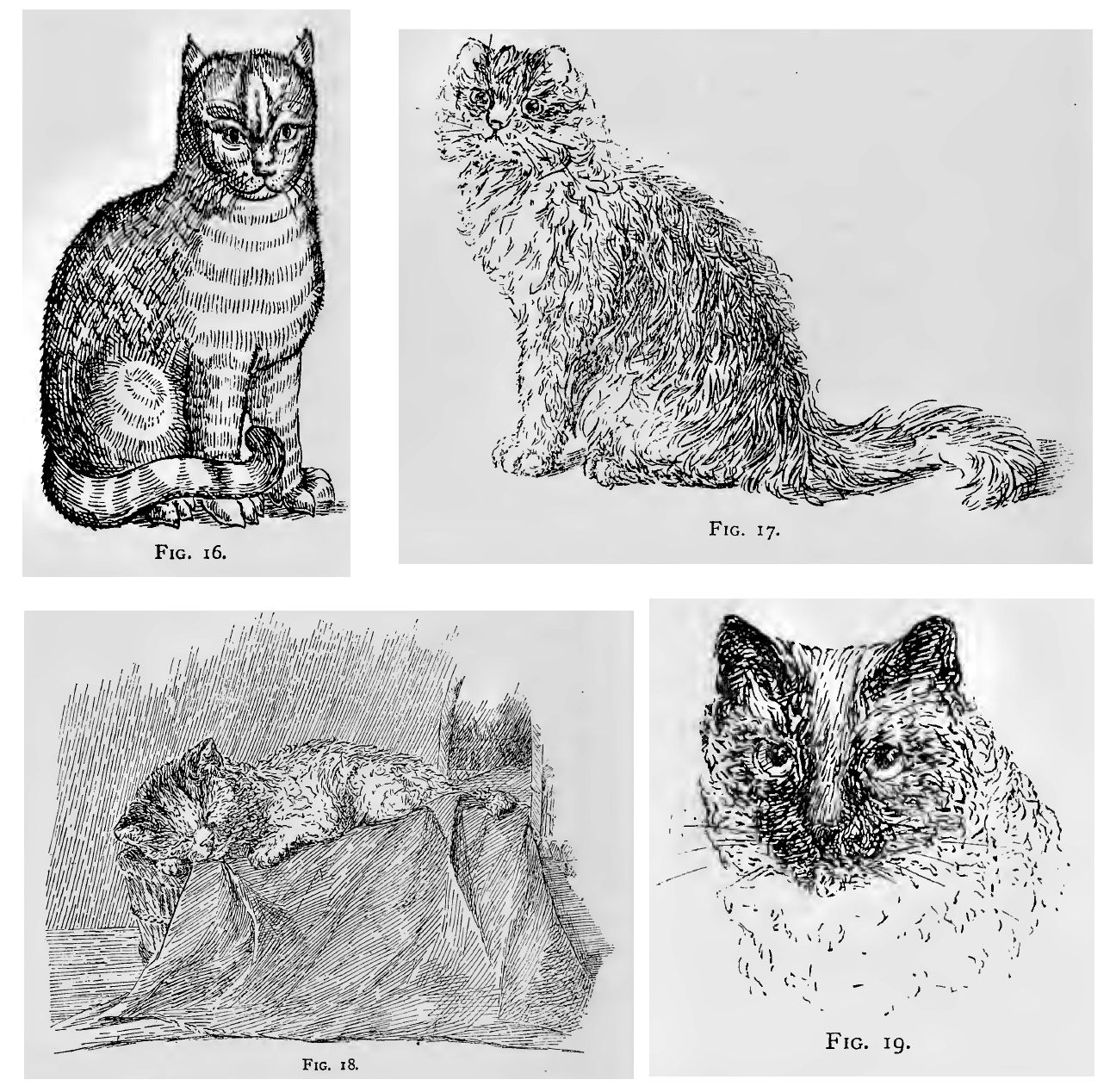

16. Figure of a Cat - From " The Historic of Foure-footed Beastes,” by Edward Topsell, 1607.

17. Sketch of a Persian Cat - By Anne Marks.

18. “Hush-a-bye, Baby” - Sketch of an English cat. By Anne Marks.

19. Head of a Siamese Cat - By Anne Marks.

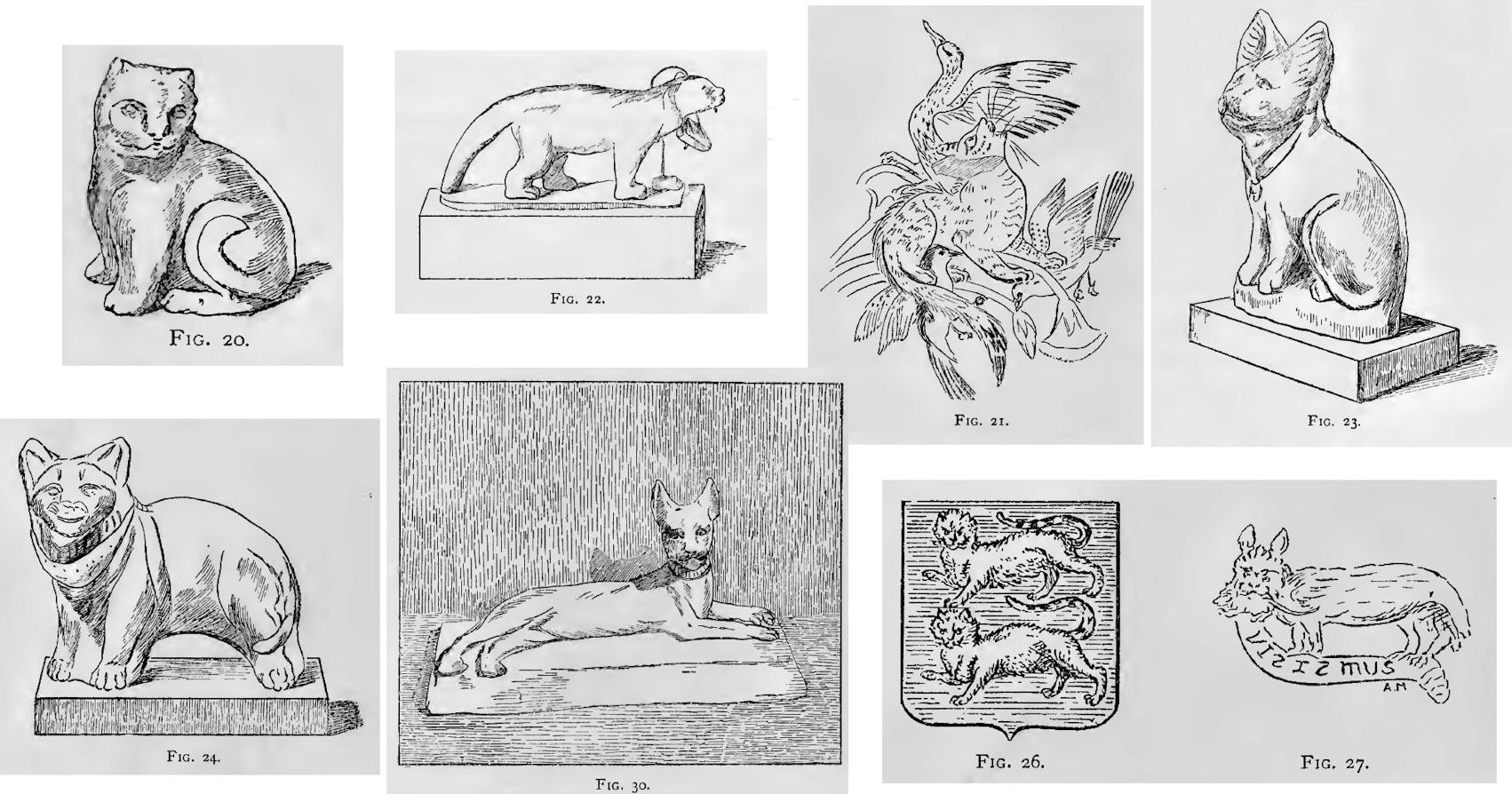

20. Figure of a Cat in Chinese Porcelain - From British Museum.

21. From “A Scribe of the Royal Granaries— Fowling ” - Portion of a wall-painting from tomb at Thebes (British Museum).

22. Cat with Movable Jaw - From model (British Museum).

23. Cat (Roman Period) - From terra-cotta model (British Museum).

24. Cat with Collar and Other Ornaments (Roman Period) - From terra-cotta model (British Museum).

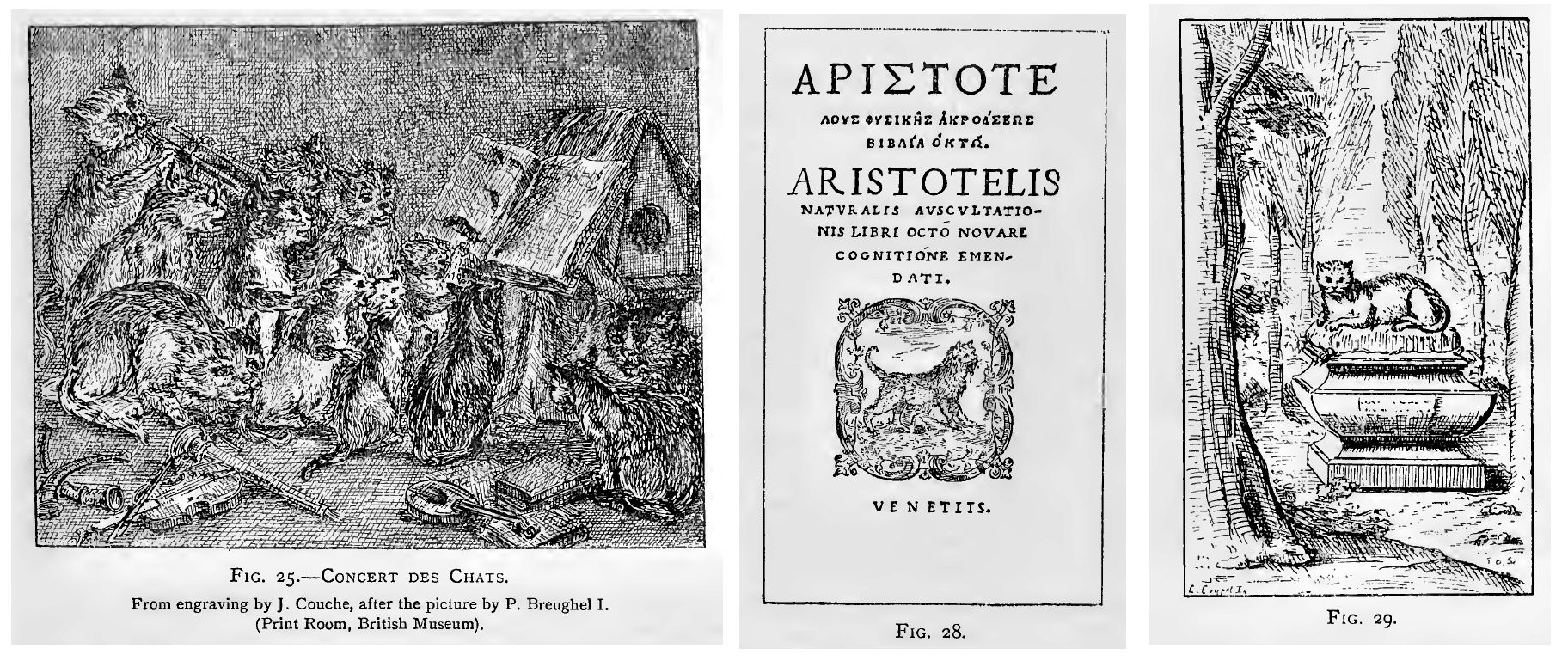

25. Concert des Chats - From engraving by J. Couche, after the picture by P. Breughel I. (Print Room, British Museum).

26. The Device of “La Chetardie ” of Limoges - From Palliot’s “ La vraye et parfaite science des armoiries ou l’indice armorial.”

27. Cat and Mouse - Mediaeval lead badge (British Museum). This and similar were worn by retainers of great English families.

28. Title-Page of Volume (Venice, 1546) - Showing trade-mark of Fratres de Sabio. From copy in British Museum.

29. Tomb of a Cat belonging to Madame de Lesdiguieres - From Moncrifs "Les Chats.”

30. Effigy of a Cat - In the museum at Bologna, Italy. From a photograph by Professor W. M. Flinders Petrie, D.C.L., F.R.S. (by permission).

Tailpiece - From painting on a Chinese plate (British Museum).

CHAPTER 1 - THE CAT IN HISTORY

Although at the present time the cat undoubtedly occupies a fairly important position, it is equally true that no other animal has experienced more varied changes in the estimation of mankind. The cat is now pampered and petted, exhibited, painted, and caricatured; it is provided with its own Burke and Debrett, and has its Clubs and shows, its boarding-establishments and hospitals. This happy state has succeeded to a period of suspicion and ill-treatment, the latter having followed still earlier ages, when puss flourished — an object frequently of reverent homage.

The history of this animal dates back to the time of the ancient Egyptians, when it was considered sacred, had its special goddess, and towns consecrated to its service, when it was sculptured and painted, and at death embalmed.

If we turn to ancient history, we find the cat-goddess of the Egyptians a deity that had many names. Under that of Sekhet she is shown with the head of the lioness, but there are innumerable representations of the cat-headed goddess Bast and of the cat as an emblem of Bast, the difference being that the goddess has the animal's head with the human figure, whilst the cat as an emblem of Bast is of course the beast itself (see Plate III.), and it is sometimes seen resting on a pedestal made in the form of the hieroglyph signifying Bast. The image was worn as a charm (Fig. 2), and children who were dedicated to the service of Bast wore a medal with the impression of the animal. The sale of these medals was a source of considerable revenue to the priests of the cult. Greek historians assert that every Egyptian temple had its feline pets.

[Footnote: Pasht,Tefnut, and Menhi were other names by which the goddess Bast was known. Bast or Sekhet was daughter of the sun-god. She was the goddess of love and one of the deities of the underworld, where as Sekhet she held the position of judge. Bast is often represented holding the Right Symbolic Eye in her left hand. ]

In Egypt the cat was held to be spiritually akin to both the Sun and the Moon, the male being more generally associated with the former and the female with the latter. As an instance of the animal’s relation to the Sun, it may be noted that Thebes means the City of the Sun, and there the cat was accounted sacred; this city was also a favourite burying-place for the animal. It is certain that in ancient Egypt the cat was an object of idolatry, the “ luminous-eyed cat ” being one of the most popular of the sacred animals; it was associated with the Sun, which was revered as an attribute of Divine power. According to some authorities, the animal was likewise worshipped in the temple of Heliopolis (the City of the Sun), because the size of the pupil of its eye was observed to vary with the height of the luminary above the horizon.

[Footnote: It must be understood that the word “ idolatry ” is not used in its usual signification, as it is now urged that the Egyptians worshipped only one God, and that their idols symbolized the various attributes of the Supreme Being. ]

As an emblem of the Moon the female cat is figured on a musical instrument, the sistrum (a sort of timbrel) which, usually held in the hand of the goddess Bast (Fig. 3), symbolized the harmony of creation. Remembering this, does it not seem incongruous to speak of the discord of our cats’ nocturnal concerts?

Another point of affinity between the luminary and the animal was found in the enlargement and fulness of the pupil of the eye, when the moon was full, and its contraction and diminished size when the planet was on the wane. A still further point of similarity was found in the increased activity of both after nightfall. It is thought that the consecration of the cat and the divine honours paid to it by the people of Egypt were due to this belief in the variation of the size of its eye in sympathy with the phases of the moon. These sympathetic changes also gave rise to the impression that the animal was to a certain extent under the influence of the luminary, and that therefore it was well to propitiate it.

[Footnote: This notion did not originate in Egypt — it is prehistoric. All the old writers give expression to this belief, although, according to the laws of light, the reverse effect would naturally take place, and the pupil of the eye would appear small in the brighter light of the full moon, and enlarged in the lesser amount of light given by the waning luminary. It may be, however, that the pupil of the cat’s eye, showing merely a line in the day-time and increasing to a full roundness at night, forms the basis of this dubitable opinion. It is said that in Egypt the feline eye glows with supernatural brightness. ]

In Suffolk it is believed that pussy’s eyes dilate and contract with the ebb and flow of the tide; this would seem to have relationship to the old idea of the influence of the moon on the eye of the cat.

While on the subject of “ cat-worship,” Pliny relates that the Arabs revered a golden cat, and in much later times the Templars were accused of adoring what has been loosely styled “ a certain cat.”

The following appropriate lines from a translation from Juvenal may be quoted:

“All know what monsters Egypt venerates;

It worships crocodiles or it adores

The snake-gorged ibis; and sacred ape

Graven in gold is seen. . . . Whole cities pray

To cats and fishes, or the dog invoke.”

It is evident that amongst the ancient Egyptians the cat held a very enviable position, and its importance may be measured by the fact that, if a fire occurred in a house, puss was first to be saved, and when in the course of nature it died, the members of the household shaved their eyebrows as a sign of mourning. If anyone killed a cat, even by accident, the punishment was death, and there is an instance on record that the life of an unfortunate Roman was forfeited for a mishap of this kind, and that the intervention of King Ptolemy and the dread which Rome inspired were insufficient to prevent the infliction of the penalty. This fear of killing puss possibly gave rise to the anecdote of an easy victory gained by King Cambyses at Pelusium. He is said to have placed several cats in front of his army, and the enemy was consequently afraid to attack it. Certainly the veneration in which the animal was held in those bygone days was a sufficiently powerful guarantee for its protection.

In Egypt at that remote period, when a cat paid the debt of nature, it was embalmed and preserved as a mummy, and the swathed face was sometimes painted (Fig. 4). The mummy-case was often made in the form of the animal (Fig. 5); occasionally it was of an oblong shape with models of cats on the top. It is said that, when an Egyptian died, his favourite cat or kitten was sacrificed, embalmed, and placed in the same sarcophagus; this seems curious, considering the penalty exacted for killing the animal. Another strange assertion is that the Egyptians used the skins of cats to cover their shields; it is scarcely credible, but, if true, it is certain that they were unsuitable, being too flimsy to be really serviceable as a means of defence. It may be noted that a few years ago a large cave was discovered in which were thousands of mummied cats, many of which were used in the neighbouring fields as manure, and many too were exported to England for the same purpose, a most unexpected and ignoble end to animals long held to be sacred, and which had been preserved for so many hundreds of years.

The most ancient testimony of the cat’s connection with man occurs in the old monuments of Egypt, Babylon and Nineveh. The earliest known representation of one of these animals is in the Necropolis of Thebes, and is four thousand years old. It is at the tomb of King Hana, on the stele of which are the effigies of man and cat; the animal (by name Bouhaki) has golden earrings hanging from its pierced ears. The representations of the cat were numerous in the Theban tombs, and models both in bronze and porcelain have been brought thence to England. The city of Beni-Hassan was another favourite burying-place for cats.

It will be noticed that in the hieroglyphics the cat is described by drawing it, and inscriptions relating to the animal are found even as early as 1684 B.c. It has its place in the Ritual, and in vignettes in the “ Books of the Dead ”; it is sometimes shown with its claws on a snake, and this combination is found in the written Rituals. In a copy of the Egyptian Ritual, dated 1500 B.c., a curious inconsistency appears in the text, “Thou hast eaten the rats hateful to Ra [the sun], and thou feedest on the bones of the impure cat.” A possible explanation of this is that puss, who was accounted sacred in one city, might in another be regarded as impure, and that thus all cats were not held to be divine. The animal is also mentioned in the seventeenth chapter (of the Ritual), which is so frequently inscribed on the coffins of the eleventh dynasty, and this (according to Lepsius) carries us back to about 2400 b.c. Amongst the vignettes in Dr. Wallis Budge’s “ Books of the Dead ”, in which cats or cat-headed gods are seen, is one which shows a tree, a serpent, and a cat with a knife. The explanation of this is that “ a cat in front of a Persea-tree, cutting off the head of a serpent, symbolizes the slaying of the dragon of darkness by the rising sun-god Ra.”

The hieroglyphic word for cat is Maou , an instance of onomatopoeia. It is met with on an old tablet (about 1 800 B.C.), “ Maiu ” or “ cat ” forming part of a woman’s name, so that to associate “ feline amenities ” with feminine attributes is not without the sanction of a high antiquity; and, alas, for women and cats! it is hinted that in the hieroglyphics on some of these monuments the cat represents false friendship.

The cat was not domesticated amongst the ancient Hebrews; indeed, there is no mention of it in the Bible, though allusion is made to it in the Apocrypha, Baruch vi. 22: “ Upon their bodies and heads sit bats, swallows, and birds, and the cats However, there are occasional references to the animal in Hebrew writings of later date. One of these is at the end of the service which is recited at the inauguration of the Jewish festival of the Passover, and occurs in a poem of the nature of “ The House that Jack Built”, a parable allusive to incidents in the history of the Jewish nation: “ And a cat came and devoured the kid ”, etc. The kid (a clean animal) represents the Hebrew people, and the cat is understood to be typical of Babylon. The Talmud says that a cat never quits the house that it has made its home, and this suggests its domestication amongst the Jews at this later epoch of their history.

[Footnote: The original of this verse is from the Greek Bible of Angelus Maius (Epistle of Jeremy, i. 21), and runs as follows ]

In India the cat was held in high esteem, and was known two thousand years ago. In the fairy-tales of that country puss is described as being clever and cunning, and always triumphing over her enemies. Sanskrit writings of a still earlier period refer to the animal.

In tracing the history of the cat through the variations of fortune which the animal has experienced in more recent times, it will be observed that fact is still so mingled with legend and superstition that it is impossible to separate the several component parts of the ensemble from each other; but it will, it is to be hoped, also be observed that as far as possible a methodized plan has been followed in this and the succeeding chapters.

The punishment of death which the ancient Egyptians inflicted for the killing of a cat was modified at a later period, when in England and Wales, in Switzerland, Saxony, and other European countries a penalty of lesser severity (yet, doubtless, sufficiently heavy to be an effective protection to the animal) was imposed upon the slayer. [Footnote: The penalty inflicted during the Middle Ages was the forfeit of a ewe, or a heavy fine of as much wheat as would be required to cover the cat when it was held up by the tip of the tail with the nose touching the ground. ]

In Persia, where we might reasonably expect that some of the most beautiful cats would be found, long-furred specimens are now very seldom seen, and a Londoner finding himself in that country might fancy that the lean and half-starved Metropolitan strays had followed him on his travels. The occasional passable specimens that are to be seen, especially if they are white, are bought for a small sum by horse-dealers and taken to India, where they are readily purchased.

The best cats of Persia — which are very unlike what we understand by Persian cats — are called “Van ”, have odd-coloured eyes, and, if thoroughbred, are deaf. They do not bear a high character, as it is said that they are in every way objectionable; indeed, the people have no respect for the cat, and there is not much trace of the influence of the animal in the art of the country. Some examples, however, occur, such as bottles made in its shape. We find similar ware of Delft manufacture (Plate V.).

The cat was very popular among the Arabs, who believed that their fairies (the Jinns) took the feline and other animal forms. In the feline shape they haunted dwellings, and extravagant tales are associated with the subject. It is stated that every caravan of pilgrims is accompanied by a man on a camel. He is called the Father of the cats, and has with him nine to a dozen of these animals, some on his lap and the rest in baskets slung by the side of his steed. Up to a recent period it was a woman, who with several cats accompanied each caravan of pilgrims journeying to Mecca, the custom being, it is believed, a survival of the carrying of cats to Bubastis.

In the East generally the animal is still very much esteemed — even honoured — and it is met with in Chinese and Japanese art and lore. In China, people tell the time of day by examining the eye of the cat, the pupil of which, as we know, becomes continually narrower until 12.0 (noon), when it has almost the appearance of a vertical line. After that hour the dilation recommences, so that in this manner we may imagine the time may be approximately known by an intelligent and experienced observer. The following appropriate anecdote, said to be quite true, is related of a missionary who, having gone out without his watch, asked a small boy the time of day. The child hesitated, and then replying: “ I will tell you directly ”, disappeared. In a few moments he returned carrying a very large puss, and looking intently into its eyes said with decision: “ It is nearly midday.”

The Chinese make a national and dainty dish of the flesh of the cat, and in China and the extreme East enormous cats are seen hanging at the provision dealers’ stalls. These animals, large and very like our own, are to be found chained in all the farms for the purpose of being fattened. In Spain, and other countries also, the people used to eat cats. The head and tail were removed, and the flesh hung in the open air to get rid of its strong flavour; after a day or two it was ready for eating, and was considered almost as sweet as rabbit.

In the Flowery Land (as in the Isle of Man) cats without tails are found, though all of these are not born without the appendage. In fact few countries can boast of so many varieties of the animal — cats without tails, cats with ordinary tails, and (mythical) cats with two tails. The kittens of Yedo are reputed to be bad mousers, in con- sequence, it is supposed, of excessive petting by their owners.

The Siamese dislike a white cat, and this is an inconsistency, as they greatly value white elephants and other white animals.

Cats were domesticated in Europe prior to the Christian Era, though they would appear not to have been widely known before the tenth century. The Etruscans and the inhabitants of Taranto in South Italy were the first Europeans to make use of the animal. It was imported from Egypt, and kept not only as a rare and petted favourite, but as a destroyer of mice. It is thought that the cat was about this time also introduced into Greece from Egypt, but, in spite of the assertion that it was quite a common animal among the Greeks at this period, there are very scant traces of it to be found in their art; it is, however, seen on some of the painted vases, and one of the few examples known is a bronze dagger engraved with the scene of a cat hunting ducks.

The Romans used the cat as an emblem of liberty, and during the French Revolution the animal was borne on the Republican shield of arms as a type of this same quality which held a supreme position in the aspirations of the French people at that time; but with the passing of the frenzied outburst the cat ceased to be of any importance in their heraldry. The Dutch, who struggled so fiercely for their independence, appropriately chose this animal as their ensign, and the Burgundians also bore it on their banner as emblematical of the same principle.

On a fourth -century tomb of the Gallo -Roman period, now in the Museum of Antiquities at Bordeaux, there is a likeness of a girl holding a cat in her arms, with a cock at her feet; at that time the playthings and the domestic animal pets of children were buried with them. This custom was probably a survival of the Egyptian one of putting food, playthings, etc., in the tomb with the mummy. The idea was that, should the departed spirit revisit the body, it would find at hand familiar objects as well as refreshment.

Pope Gregory the Great, who lived towards the end of the sixth century, made a pet of his puss, but towards the period of the Lower Empire the position of the cat had become degraded, the minor poets of the age holding it in profound contempt and accusing it of all kinds of failings, including greed and dishonest propensities. Yet the artists in mosaic were in the habit of portraying it.

In Turkey, as in all Mohammedan countries, cats have always been the object of much solicitude, probably because of the extreme affection shown for them by the prophet Mahomet. They may even enter the mosques, where they meet with attention and caresses. At Constantinople they are treated with as much consideration as the children.

In Cairo there is an endowment for lodging and feeding homeless cats; this was founded in the thirteenth century by El-Daher-Beybars, the Sultan of Egypt and Syria, who was very much attached to these animals, and it is the first of similar institutions that now exist in London and other places in England, in Italy, and in Switzerland.

Referring to the Cairo home, or the garden Gheyt-el-Quottah (the cats’ orchard), it was originally adequately endowed, but from various causes the funds arc now so reduced, that the food provided is insufficient for the pensioners. It is also narrated that there exist in Constantinople institutions supported by people of the highest quality, and having for their object the maintenance of cats that prefer to live unattached. Open house is kept; puss is kindly received, and may, if she desires, spend the night in the home. Moreover, she has a choice of such hospices, for a great many are to be found in nearly all the towns. Hence mistress puss need never revisit a home which does not satisfy her whimsies.

In Florence there is a cloister near the Church of San Lorenzo which serves as a home for cats.

The cat was not domesticated in Gaul, and amongst the numerous small terra-cotta figures of animals made by the potters of Allier it is not included, but at a later period the representations of puss began to appear, and gradually became more numerous.

Succeeding the cruelties perpetrated on the animal during the Middle Ages, amongst the first signs of improvement in pussy’s condition was the publication of an edict in Flanders in 1618 prohibiting the practice of throwing cats from the high tower of Ypres, which had hitherto been a customary performance on the Wednesday of the second week in Lent. The custom of flinging cats into the bonfires kindled at Metz on the festival of St. John (held on June 24) lasted longer, and it was not until the middle of the eighteenth century that the wife of the Marshal d’Armentieres obtained from her husband an order for the suppression of this act of cruelty. For this ceremony, while it lasted, the magistrates used to assemble with much solemnity in the public square, and place a cage containing cats on a funeral-pile; to this, with great parade, they set fire. The people believed that the frightful cries made by the poor beasts were evidence of the sufferings of an old sorceress, supposed long ago to have been transformed into a cat when she was about to be burned. On the other hand, even in the Middle Ages, puss could be an honoured personage at high festivals. In Mill’s “ History of the Crusades ” an account is given of the fete of Corpus Christi, held at the town of Aix in Provence, in which the finest male cat of the district was selected to be wrapped in swaddling-clothes like a child, and was then placed in a magnificent shrine and exhibited to the public for their homage. This was evidently a survival of Egyptian adoration, for everyone knelt before the cat, strewing flowers or offering incense, and puss was held in every way to be the god of the festival.

At the time of the Norman Conquest laws were in force in Britain regulating the price to be paid for kittens. A kitten before the eyes were opened was worth one penny, afterwards just double the amount, and when ranked as a mouser it was valued at fourpence. By the same laws it was also decreed that a cat to be of full value should see, hear, have its claws, and be able to kill mice. In order that a mistake should not be made as to the animal referred to in these (and other) laws, a rough sketch of puss is added. These regulations indicate the value of the domestic breed in this country at the time, and are probably a proof that it was distinguished from the wild species at a period when the latter existed in large numbers. Early in the twelfth century a law was in force in England forbidding any abbess or nun to wear fur more costly than that of the lamb or cat (the latter fur being at that period commonly used for trimming dresses), but it seems uncertain whether this regulation applied to the fell of the domestic or the wild animal. By the way, it has been suggested that about this time the custom of keeping cats in nunneries originated the tradition which associates the animal with old maids.

Wild cats were an object of the chase, but, on the other hand, they were also employed in the capacity of hounds, and were of sufficient importance to require an officer to take charge of them. This functionary was called a “ Catatore ”, and his position was equal to that of the Master of the King’s Hounds. In “ The Scornful Lady ”, a play by Beaumont and Fletcher, an allusion to this employment of the animal is made in the line, “ Bring out the cat-hounds; I’ll make you take a tree.”

There were different sports indulged in in Scotland and elsewhere in which puss was most cruelly treated. “ Cat in Barrel “ (1) and “ Cat in Bottle” (2) — the latter referred to by Shakespeare, and in vogue long after his days — were two of these of a somewhat similar nature. “ Catte in a Basket ” was still another game, but in this the cats shot at were sometimes dummies, though on other occasions the animal itself was used. [Footnote: (1) To the sound of music and the beating of drums, a cat was placed in a barrel that contained a quantity of soot; this was suspended from a cross-beam resting on two high poles. Those taking part in the sport rode in succession underneath the barrel, striking it with clubs and wooden hammers. When the barrel at last broke, and the cat was forced to appear, it was cruelly killed. (2) In this sport a cat, enclosed in a bag or leather bottle, which was suspended from a tree, served as a target. The object was to break the bottom of the bag, and by agility to escape receiving a blow from the falling animal.]

M. Paul Megnin relates that the domestic puss may occasionally be found engaged in catching fish. He writes of one that was surprisingly dexterous in taking gold-fish from a bowl; with a rapid movement of the paw the fish was quickly captured, and transferred from the water to the table. Apropos of this, Gray wrote a poem on the tragic death of a cat by drowning while trying to take gold-fish from a bowl. The author has had several kittens whose chief delight was to dabble with their paws in their dish of drinking-water. One was especially skilful in playing a game of repeatedly sending a ball or piece of paper into the saucer for the express purpose of fishing it out again.

Our Government allows a certain yearly sum for the maintenance of cats in our different shipping and other public offices, stores, etc.; the value of their services is thus amply acknowledged. The Vienna municipal authorities maintain several of the animals in like fashion.

Cats are of a loving nature, and delight in displaying it towards those whom they select for attention; they rub against them, or insist on being nursed, purring loudly and continuously the while. Frequently they exhibit a decidedly jealous tendency, and resent notice taken by their owners of other cats. Indeed, there is an anecdote told of one puss who, if displeased, marked her disapprobation by deliberately taking a distant seat and turning her back to the company.

Some say that St. Ives, the patron saint of lawyers, is depicted as accompanied by a cat, and that in consequence the animal is used as the emblem of the officials of Justice — very suitable, if we remember that a clause in law, like a cat’s claws, may under a smooth exterior conceal a weapon sharp and formidable. It has also been said that cats are frequently involved in grave testamentary questions, and occupy the attention of the police and tribunals of civil law more than any other animal. As an example, if a merchant ship is without a cat on board, and the cargo has received injury from rats, the proprietor of the cargo can recover compensation from the owner of the vessel, although, in a general way, marine insurance does not cover injury by rats. On the other hand, if rats kill a cat, there is no redress — on the same basis that “ a man who is killed by a woman is held to be no man.”

An instance occurred some years ago, when a suit was heard which made a great sensation. A brother demanded “ interdiction ” against his sister, because “ she had had a tooth of her deceased cat set in a ring ”, and he considered that this was an undeniable proof of insanity or imbecility. We are inclined to agree with him.

CHAPTER 2 - THE CAT IN MYTHOLOGY AND LEGEND

The cat is fabled to have appeared first at the time of the Deluge, when Noah, fearing the depredations of the mouse, prayed that the stores in the Ark might be protected. As an answer to the prayer the lion sneezed, and a pair of cats sprang out of his nostrils. The Manx, a tailless cat, claims as ancient a pedigree, for, when the Flood ceased, puss — so runs the legend — in her impatience to leave the Ark, jumped out of the window and had her tail snapped at by the dog, then, as now, her natural enemy. Puss escaped, but left her tail in the dog’s mouth. How the Isle of Man was reached and became the home of this feline curiosity is not told.

There is a legend in Russia which is supposed to explain the antagonism that prevails between the cat and the dog, but it differs widely from the foregoing fable in some points. It tells us that, when the dog was created, and while he was waiting to receive his robe of fur, he lost patience, and followed the first-comer who called him. This happened to be the Devil, who made him his emissary, and sometimes even borrowed his appearance. The fur destined for the dog was given to the cat, and perhaps the former’s belief that the other has appropriated what should have belonged to him may suffice to explain the antipathy that exists between the two animals.

Apropos of the association of the cat with the Ark, in an old Italian picture showing the departure of the animals from its shelter, a fine puss leads the way, evidently well satisfied with its prominent position. Moncrif relates another curious legend concerning the origin of the cat, which was imparted to him by Mulla, a minister of the Mussulman religion. It runs thus: “For the first few days of residence in the Ark each animal, frightened by the motion and by the strangeness of the surroundings, remained with its kind. The ape was the first to tire of the restricted life, and made advances to a young lioness, and it was from this ‘ amour ’ that the first pair of cats sprang.” Greek mythology gives it a still different origin. Apollo, wishing to frighten his sister, created the lion; Diana, for the purpose of retaliating, and at the same time desiring to throw ridicule on the animal whom the god designed to call “ king ” of the beasts, created the cat.

The association of the cat with the moon is set forth in the mythologies of many nations. We have already treated of the cat in Egyptian mythology, which is so closely interwoven with the early history of the animal that it would be difficult to separate the two accounts. Among the Hindoos the word for “ moon ” is the same as that for a “ white cat ”, and their quaint expression, “ The cat-moon eats the grey mice of the night,” is symbolic of the disappearance of clouds under the influence of the moon. In Sanskrit legend the huntress Diana — who is also the Moon, and identical with the goddess Bast of the Egyptians — took the feline form, when the gods fled from the giants. In this shape she was able to act as a spy, the cat being watchful and wary. Plutarch associates the luminary and the animal, because a cat was fabled to bear one kitten at the first birth, two at the second , three at the third , and so on until the seventh. She had then borne twenty-eight in all — i.e. the same number as there are days in the lunar month. The following is an Australian myth which is supposed to have a con-nection with Mityan (the moon): A cat fell in love with a bride, and in the consequent quarrel with the husband was beaten, and ran away — condemned to wander for ever. Another Australian legend tells us how certain animals solved the problem of kindling a fire, and in this legend the native cat tribe is mentioned ( vide “ Australian Legendary Tales ”, collected by Mrs. K. Langloh Parker). Nevertheless, some writers assert that the Australian region may be considered the typical catlrss portion of the world, and that the domestic breeds now found there are entirely the result of importation.

It must be understood that in legends of this class there is a distinction between the white and the black cat, the former being an emblem of the Moon and a protector of innocent animals, the latter a symbol of the dark — that is, the moonless — Night. Black cats are also associated with witches, and this superstition was very prevalent throughout the Middle Ages, and survived until comparatively recent days, during which period puss had usually a bad time.

In Northern mythology the cat figures somewhat prominently. That the chariot of the goddess Freya was drawn by cats, and that Holda was attended by maidens riding on cats, indicated, it is said, a widespread belief in the animal’s weatherwise powers. The wolf “ Fenrir ”, a monster, is fabled to have been effectually bound with the chain “ Gleipnir ”, which was, so runs the old story, composed of six materials, one of these being “ the sound of a cat’s footstep.” In Teutonic mythology the cat is sacred to St. Gertrude, the goddess who protected departing souls; and in Sicily it was honoured as belonging to St. Martha. [Footnote: Freya is the Venus of Scandinavian myth; she is also a form of Demeter, and her cats are said to be symbolic of sly fondling and sensual enjoyment. Bast is the Venus of Egyptian mythology. ]

A very old legend is told of the prophet Mahomet, who was a great lover of the cat. It is related that one day, his feline pet having fallen asleep whilst lying on the sleeve of his robe, he cut off that part of his dress when obliged to move, in preference to disturbing pussy’s slumbers. There is a similar modern anecdote given of a certain soldier in the East. He was observed to remain persistently in the scorching sun instead of seeking shade, because the movement would have disturbed a kitten that was sleeping on his lap.

An old Grecian fable relates that, when the mice were at war with the frogs, the former covered their cuirasses with cat’s-skin.

It is difficult not to give credence to the usual acceptation of the legend of “ Whittington and his cat.” It is very well known, and need not be repeated here; but a second and very interesting, though less romantic, variant avers that his cat was not an animal, but a ship that was used for carrying coal, in which traffic Sir Richard is said to have made his fortune by bringing coal in his cat from Newcastle to London. On the other hand, when Whittington’s house was restored in recent years, a carved stone was found which showed the portrait of a boy holding a cat. [Footnote: The “cat" was originally an old-fashioned Danish or Norwegian ship. It had a narrow stern, projecting quarters, and deep waist with rounded ends, and was flattened underneath; the masts were small and light, with square-cut sails. The last cat-built ship disappeared about fifty years ago. In addition to the ship, an anchor, and tackle for drawing up the same, were similarly named. Apropos, there used to be a joke: “ Do you know when the Mouse [a certain sandbank in the Thames] caught the Cat?" ]

The following is a Russian rendering of the ancient tale from which the usual version of “ Whittington and his cat ” is supposed to have emanated, but probably both are derived from a Buddhist source, to which the incident of burning of incense points: A poor youth seeing a kitten being tormented, purchases it for three copecks, the only money he possesses. In order to earn his living, he engages to sit in a merchant’s shop and mind the business, which thereupon prospers exceedingly. The merchant charters a vessel to go on a distant voyage, and borrows the kitten both to catch the mice and to amuse himself. When the ship reaches its destination, and the owner is on shore, he is put in a bedroom infested with rats and mice, and puss protects him by destroying the vermin. The landlord purchases the kitten, giving in exchange as much gold as would cover it when held up by the fore-legs, the hind-legs resting on the ground. On the return journey the merchant thinks he will keep the money for himself, but a terrible storm bursts forth, which only ceases when he decides to give it to the rightful owner. With the gold the youth purchases a shipload of incense, and he burns it along the shore in honour of God. An old man now appears before the hero, and gives him the choice of riches or a good wife. Not knowing what answer to give, he is told to inquire of three brothers who are ploughing close by, and the advice is to choose a good wife. Thereupon a beautiful girl stands by his side, and tells him she will marry him. This tale, like so many of the old fairy legends, contains a warning against the sin of avarice. A variation of the story is related in Servia.

Puss also appears in the nursery tales of the Western Isles of Scotland, tales which, however, can be traced to Indian stories, these having been taken from Chinese books translated from Sanskrit manuscripts. It is, by the way, generally conceded that the nursery tales of most countries bear a strong resemblance to each other. This suggests their having had a common genesis.

Our Puss-in-boots has its equivalent in Russia and other countries, and the Swedish version is found in one of Thorpe’s “ Yuletide Stories” — namely, “The Palace that stood on Golden Pillars”; but in this latter tale the principal character is a princess whose cat performs the wonders that Puss-in-boots did for the Marquis of Carabas. The legend is also met with in France, where it was translated from the Italian in the sixteenth century. The moral of the tale is that “ mother-wit is better than riches.” Our Cinderella dispenses with puss, but another version of this fairy story is “ Cat-skin ”, and in it the heroine is clothed in a robe of the animal’s fur, until her fortunes change with her marriage with the hero-prince. This tale is also of Oriental origin.

The fable of “The Cat and the Mouse” that appears in different countries is undoubtedly of Buddhistic origin, and is found in ancient Sanskrit, Indian, and Chinese books, the Indian rendering varying but slightly from the Chinese. The following versions of it will show the similarity between them.

The Indian tale relates that a man in joke hung a religious emblem round his cat’s neck, but the mice took it as a sign of a devout disposition on pussy’s part, and congratulating themselves, commenced enjoying life with easy minds. Speedily, however, the cat having caught and eaten many of them, the survivors remarked: “We believed he was praying to Buddha, but it is evident that his piety was only a cloak.”

In Sanskrit legend we have the cat who feigns repentance, and who is called upon to act as judge in a dispute between a sparrow and a hare. He pretends to be deaf, and asks the two disputants to come nearer so that he may hear what they say; on their approach, he seizes and devours both.

One more variation of this fable — namely, that from Thibet — shall be given: A cat that had been a great hunter when he was young, found that his powers lessened as years advanced, and therefore contrived the following stratagem in order to still obtain his prey. He took up his position near a mousehole, and pretending to do penance, appeared quietly devotional. This deceived the mice and won their confidence, but every day as they returned to their hole the cat slyly caught and ate the last of the troop. The chief mouse, noticing the diminishing number of his followers, became concerned, and remembering the flourishing appearance of puss, suspected deceit. He set a watch and discovered the artifice, when he bitterly reproached the cat for the feigned penitence which had enabled him so treacherously to secure his prey.

In Hellenic fable the mice decide that in order always to know the whereabouts of puss, and thus be on their guard, a bell shall be hung round her neck, but no one amongst them will consent to undertake the formidable task of putting it there — hence the proverb, “ Who will bell the cat?”

There is a Zulu nursery story in which occurs the incident of the presentation to a widowed Queen of the tail of a wild cat, the emblem of a Queen Dowager.

A negro fable (which strongly resembles one of Aesop’s) tells how a cat and a rat, after stealing some cheese, cannot agree about the division of the spoil, and ask the fox to be umpire; but he takes so much of it as the judge’s share that the disputants expostulate. He loses his temper, and tells them to be thankful that he does not kill them both; after this he eats all the cheese. [Charles C. Jones, jun., LL.D., “ Negro Myths from the Georgia Coast.”]

There is a legend which tells of a race of Chinese cats with pendent ears, but it is said that no one can be found to verify the existence of this variety, and Pere David, the French missionary, who knew China intimately, regarded the report as fabulous. However, in M. Paul Megnin’s “ Notre Ami le Chat ”, a sketch of this animal is given.

In the folk-lore of Japan cats are mentioned with great awe, for they are credited with the power of assuming the human shape in order to bewitch mankind; on the other hand, it is set forth that they work for good as well as for evil ends. Many a legend comes to us from that country. In one, the two-tailed Vampire Cat destroys the customary beautiful heroine, and taking her form, preys on the handsome prince, but in time the cruel creature is exposed and destroyed by a faithful retainer. In another legend cats appear as loyal and devoted followers, and two of them, dying in the service of the lord’s young daughter, have honourable burial in the neighbouring temple. A third narrative bears on the reputation puss has won as a destroyer of snakes. Two cats run away from their respective homes in order to be married; they get separated, and one of them is taken to the royal palace, where he kills the viper that is persecuting the Princess. Later, he and his former companion meet again and marry; they live happily in the palace for many years, and in the end they die together.

Near Bafa (the ancient city of Paphos), in the island of Cyprus, is the noted Cape of the Cats. In connection with it there is an interesting old tale which relates that in former times a monastery stood there, and the monks kept a certain number of cats for the purpose of making war on the serpents that infested the neighbourhood. These animals had been trained to repair to the abbey, when they heard the sound of a particular bell, in order to take their meal; afterwards they returned into the country and continued their hunting with persistence and skill. However, when the Turks conquered the island, the cats (strange to relate) were destroyed with the monastery.

It is said that cats are also employed at Paraguay to hunt the rattlesnakes which abound in the sandy soil. With instinctive skill puss strikes the reptile with the paw, and immediately throws herself on one side to avoid the counter-attack of the enemy. This is repeated until the serpent is dead.

But though generally enemies, the cat and the serpent may at times become friends, and apropos of this, it is narrated that in a certain monastery, where there was a pet cat, the monks, who were in the habit of fondling it, suddenly became ill, and, it was said, showed symptoms of poisoning. The poison theory was incomprehensible to the sufferers, until a labourer announced that he had seen the cat at play with a serpent, when the physician concluded that the reptile had conveyed some of its poison to its playmate, and this was transferred to the monks when they handled their pet. The reason that puss was not harmed by the virus was that it was not communicated in anger, and the same argument would probably explain that, though the monks became infected, no serious consequences followed.

Puss appears (but only incidentally, and chiefly in association with millers) in some of the Turkish fairy-tales. In one entitled “The Ghost of the Spring and the Shrew”* there is a vivid description of a poor old cat, but in a curious manner it completely drops out of the story near its commencement. Another, “The Rose Beauty ”, begins in the approved fairy-tale fashion, “ Once upon a time ”, etc., and introduces a miller who has a black cat. [“Turkish Fairy-Tales”, by Dr. I. Kunos. Translated by R. N. Bain]

An anecdote (probably legendary) tells us that the wife of an Emperor of Turkey indulged her feline favourite by serving her with food on a gold plate at the imperial table.

In a Russian folk-tale, “ The Ring with Twelve Screws ”, the hero is saved by the good offices of his cat and dog; they also recover and restore to him his magic ring, the loss of which has occasioned his troubles. In another of these legends, “The Seven Simeons, Full Brothers ”, the Tsar has desired to wed a beautiful Princess, but his suit has been rejected. The Seven Simeons undertake to kidnap her, and, accompanied by their cat, travel to the far-off land where she dwells. The cat, an unknown animal in this remote country, attracts the attention of the Princess, who desires to buy it. The youngest brother replies that they will be very pleased to present the cat to the royal maiden, and by request he visits the palace daily to teach it to be friendly with her. On pretence of showing the Princess some beautiful brocades, he persuades her to accompany him to his ship, and directly they are on board sets sail, carrying her away. After many adventures he brings her to the Tsar, by whom the brothers are munificently rewarded. [J. Curtin’s “Russian Myths and Folk-Tales.”]

Amongst characteristic mediaeval chronicles is the following legend of the cats of Beaugency (a town on the River Loire in France): An architect employed in the construction of the bridge of Beaugency could not manage to complete it, for, as soon and as often as the last arch was built, it tumbled down. This had occurred three or four times, and the poor man, receiving no assistance from the saints he had invoked, in the end appealed to the Evil Spirit. The fiend undertook the work on condition that whoever first passed underneath the arch should belong to him. The architect consented, but, his end attained, he bethought himself of cheating the Devil by sending a cat as first traveller. Satan, enraged, tried to destroy the work, and at last, in giving a mighty kick, succeeded in disturbing one of the buttresses, which has ever since remained out of the perpendicular. However, unable to demolish the structure, and baulked of his human prey, he quitted the spot, carrying off the cat, whereupon the frightened animal tore her captor’s hands and face in a horrible manner. Satan, the tale continues, could not endure the pain, and allowed the unfortunate prisoner to escape. Poor puss speedily took refuge at a place some distance away from Sologne. The locality was in consequence called Chaffin (Chat-fin), and since the time of this notable incident the inhabitants of Beaugency have borne the nickname of “ Cats.”

The cat was known to the ancient Celts, and appears in some of their legends as a transformed Princess. It was, however, as well as the dog and the cock, sacrificed at their religious festivals, and it is asserted that, within recent years in the Western Highlands, a cat was roasted alive as a means of raising the fiend for the purpose of discovering treasure.

The Irish narrative of two cats that fought so fiercely in a saw-pit that, when the battle was over, there was nothing left but the tails, is a figurative relation of the discord that prevailed between the municipalities of Kilkenny and Irishtown. Until the end of the seventeenth century these towns were constantly at variance about their boundaries and other disputed claims. From this tale comes the saying, “to fight like Kilkenny cats ”, which of course signifies, to engage in a mutually destructive struggle.

The association of cats with witches is very ancient, and had its origin in pagan times. It is narrated, that when Galinthias was metamorphosed into a cat, Hecate took pity on her and made her a priestess. [ Vide Ovid’s Metamorphoses, IX. 306.] It has already been mentioned that Diana (another form of Hecate) at one time found refuge in the feline form. Numberless legends are related of cats having spoken to human beings, who in return struck, kicked, or burned them; and, as the sequel, these same people are invariably said to have met men or women, generally the latter, during the next day who bore the marks of the injuries inflicted on the animals the previous night — a supposed incontrovertible proof of witchcraft and bedevilment. There is little doubt that in those days such evidence sufficed to cause the death — as supposed witches — of many innocent women, and the people of the Middle Ages who burnt “ wise men ”, as well as hags and sorcerers, as a matter of course did not hesitate to burn cats; indeed, the latter three were classed together as alike in character.

As cats were supposed to be the companions of witches all over the world, the Highland hags of course followed the fashion, and the animals were credited with marvellous feats in the Scottish mountains. For example, an instance is recorded at the end of the sixteenth century concerning a cat that, after being christened, and having other ceremonies performed over her by witches (who may be supposed to have borne malice to gentle King Jamie), was conveyed into the middle of the ocean, and at last left before the town of Leith. The result was a great tempest, which not only caused the loss of a vessel in which were jewels and gifts for presentation to James’s Queen, then about to visit the town, but also occasioned a contrary wind to arise, so that the ship which was bringing King James himself from Denmark was separated from the rest of the fleet. This is vouched for as not only strange, but true, and was acknowledged to be so by the King himself, who was without doubt a believer in witchcraft.

W. Grant Stewart, in his “ Popular Superstitions and Festive Amusements of the Highlanders of Scotland ”, narrates a couple of anecdotes about witches and cats which are full of weird incident. The events in both occur on the same day, and the heroes are described as men who make unremitting warfare on the hags of their district. In the first tale a well-known laird takes a hunting party across to one of the isles, and after a day’s successful sport they pass the night in the shooting-box. When it is time to return on the following day, the weather has become stormy and the sea turbulent. Most of the party wish to defer the passage, but the laird appeals to an old bent woman, who appears at the moment, as to her opinion of the prospect of a safe crossing home. She advises him to set sail, at the same time deriding for their cowardice those who would draw back. As soon as they have embarked, the tempest becomes more furious, and the host, in order to encourage his guests, keeps very cheerful, and himself takes the helm. At this moment he notices a large cat that is climbing the rigging; another follows, then others, and this continues until the shrouds, masts, and tackle are completely covered with them. He recognizes that they are demons, but does not feel afraid until a black and still larger cat appears on the masthead as commander. The laird orders an immediate attack on the army of disguised fiends, but it is of no avail; by their combined efforts the cats overturn the yacht, and all the passengers are drowned, and thereby the witches are avenged. But these latter are unsuccessful in their second attempt at vengeance, which the other anecdote relates.

The incident which it describes takes place later in the same day. It is an attack on the life of a friend of this same laird. He is in his hunting-box, when an apparently poor, weather-beaten puss appears, and asks for shelter. She pretends to be afraid of two huge dogs that are lying by the fire, and begs their owner to chain them with a hair that she gives to him. This hair, however, looks so peculiar that he only feigns compliance. The witch-cat sits down by the hearth and soon begins to grow larger, and when the hunter remarks on this strange phenomenon, she replies that it is quite natural, and that, as her fur absorbs the heat, it expands. Suddenly she turns into a woman of his acquaintance, and (as he now discovers her to be) a witch. She tells him of his friend’s death, and states that his hour has also come; but when she attacks him, his dogs, whom she believes to be bound, spring on her, and a terrible fight ensues in which she mortally wounds the hounds, but not before they have fatally injured her. She is able, however, to transform herself into a raven and fly away, while they crawl to the hearth and die. The hunter, after sorrowfully burying his poor faithful guardians, goes home to his wife, who tells him that an acquaintance of theirs has suddenly been taken seriously ill; she proves to be the witch who had attacked him in the afternoon, and who is of course dying from the effects of the struggle with his dogs. He goes to her house and exposes her wickedness, but in answer to her prayers for mercy the neighbours allow her to die in peace, instead of inflicting the customary penalties. However, she is evidently not to be at peace after death, as later in the night another neighbour, on his return from a journey, relates that he met a woman who was running at great speed, but halted a moment to inquire how long it would take her to reach the churchyard of Delarossie. When she heard that it was possible she might succeed in doing so before midnight, she hastened on. Farther on he met a huge black dog, and then a second, both running in the same direction as the dame. Still farther on he met a horseman, who inquired whether he had happened to see a woman, and if so, whether he had spoken to her. Shortly afterwards, when this same horseman, returning from the direction of the churchyard, again passed the traveller, the latter noticed that the female was lying across the saddle of the horse with both the dogs fastened on to her, and the rider remarked to him that he had overtaken the woman just as she was about to enter the churchyard. Thus she was too late to escape the Devil, who, however, was only getting his due.

Other legends inform us that puss occasionally gets the mastery over the Devil and other demons, and in doing so becomes a good spirit.

A fable, which has its origin in Tuscany, relates how a woman, with a large family of children and a total lack of means of supporting them, hears of the existence of a beautiful palace inhabited by a great many enchanted cats, who are very charitable to the poor. She seeks the palace and is admitted by a kitten. She performs various domestic duties, and thus shows that she is willing and obliging. At last she is presented to the cat-king, who is seated in state and is adorned with a crown. When he hears how helpful she has been, he orders her apron to be filled with golden coins as a reward. The woman has a wicked sister, who thinks that she also would like to obtain money from the same source, but instead of helping the cats she maltreats them. In return they scratch her badly, and she reaches home nearly dead with pain and terror. A similar theme is illustrated in one of our old fairy stories: the good and beautiful stepdaughter is rewarded for her kindness to an old woman — a disguised fairy — while the bad and ugly daughter, who is lazy and spiteful, and who shows herself disdainful towards one whom she believes to be a beggar, meets in return with merited punishment.

In Germany the “ nightmare ”, amongst other fantastic appearances, sometimes comes in the form of a cat, and a story is related of a man who was visited in this way. He stopped up the hole by which puss had entered the room, seized the animal, and nailed it to the ground by one of its paws. In the morning he found to his horror not puss, but a beautiful girl fastened to the floor with a nail through her hand. He married her, but when in later days he happened to uncover the hole, his wife immediately resumed the cat form, and escaped, never to return.

The following legend is told in the south of Lancashire: One evening a gentleman who was sitting quietly in his parlour was interrupted by the appearance of a cat which came down the chimney, called out, “Tell Dildrum Doldrum’s dead”, and immediately disappeared. Naturally startled, the gentleman told his wife (who presently came in) of the surprising incident, and (the legend continues) his own cat, who now entered, on hearing it, exclaimed: “ Is Doldrum dead?” and vanished up the chimney, never to return. Numerous explanations of the incident were suggested, but the generally accepted one was that Doldrum had been monarch of Catland, and that Dildrum (the gentleman’s cat), who was the next heir, had departed to claim his kingdom. A similar legend has its home in Northumberland.

CHAPTER 3 - THE CAT AND SUPERSTITION

In treating of superstitions associated with the cat, it may safely be asserted (in spite of the fact that some of them favour the animal) that no other four-footed creature has suffered so much from the cruelties incidental to this lamentable offspring of ignorance. In this country, in common with most others, superstition in regard to the animal was great and widespread during the Middle Ages, when many people believed that almost every movement of the cat had some significance. Some of these beliefs linger on even up to the present time, for the idea still survives that a black cat brings good luck, and that a sable stray should never be turned away from the house; it is also believed that, at the completion of a newly-built dwelling, a stray should be brought in “for luck” — a black, not a white puss, for the latter would be considered a harbinger of ill-fortune. Possibly we have here a variation of the superstition that on removal to a new house a cat or dog should be thrown in before anyone enters; the idea is that whoever first crosses the threshold will be the first to die. In Ireland, however, it is considered most unlucky in removing to a new house to take the cat, and in consequence the animal is turned adrift.

By some authorities the sable puss is credited with miraculous healing powers. For instance, there are districts of this country in which a black cat is supposed to be, in regard to epilepsy, not merely an antidote, but a cure. In Cornwall again, sore eyes in children are said to be cured by the passing of the tail of a black cat nine times over the part affected. There are places (not necessarily in this country) where it is believed that blood from the tail of a cat will cure erysipelas.

In Germany it was at one time believed that the appearance of a black puss on the bed of an invalid presaged death, and one seen on a grave was regarded as a sign that the soul of the departed was in the power of the Devil. Another superstition averred that to dream of a black cat at Christmas foreboded some serious illness during the following year.

Black cats and skulls were the requisite accompaniments of the work of witchcraft; the former were always to be found in the hovels of the sorceress and the wizard, while the steed of a witch was a tom-cat, a black one for choice. The apparatus required by the Evil One for the accomplishment of his enchantments included nails from the coffin of a person who had been executed, portions of a goat which had been a woman’s pet, and the skull of a cat that had been fed on human flesh.

For a long time black cats were believed to be witches, because they were reported to be seen on the Sabbath in the company of goats and toads. Often, merely as the companion of a witch, puss shared the fate of her mistress and perished in the flames. It was anciently asserted that hags were allowed to take the form of the cat nine times, and it was a common belief that the animal, when it reached the age of twenty, became a witch, and that a witch who lived to be one hundred turned again into a cat. In Hungary a variation of this superstition was current to the effect that a cat generally became a witch between the ages of seven and twelve years.

In the Middle Ages it was believed that Satan appeared as a black cat, when he desired to torment or show his power over his victims; indeed, this was imagined to be his favourite disguise, and puss therefore became an object of dread. St. Dominique in his sermons represented the Devil in the guise of a cat.

In those days a kind of incantation was employed in which the cat was introduced, and by which the reciter of the charm was enabled to see demons. It may be that the connection of black cats with witchcraft was to a large extent due to the great quantity of electricity (more in black than in other cats) liberated from the coat by friction. Apropos of this supposition, it has been remarked that a cat, in moving quickly through an undergrowth of vegetation, produces an appearance of luminosity, and this being more noticeable in frosty weather, it was attributed to uncanny influence. It has also been observed that highly sensitive temperaments experience something akin to an electric shock through the slightest contact with the fur of a black cat; by the way, the Rev. Gilbert White, in “The Natural History of Selborne”, relates that, during two intensely cold days, the fur of his parlour cat was so charged with electricity, that anyone properly insulated, who stroked the animal might have communicated the shock to a whole circle of people.

Black cats were associated with witches in many districts of Southern Europe, and in Norwegian folk-lore; in the latter they were also believed to inhabit ghost-haunted houses and to indulge in nocturnal revels. It is curious, notwithstanding these delusions, that among the Scandinavians and the people of Northern Europe puss should have been considered as an emblem of love; they used also to believe that cats were possessed of magical powers, and that it was advisable to humour them. In Sicily it was thought that, if one of these sable cat-fiends lived with seven masters, the soul of the last of these was fated to accompany him on his return to Hades.

Although we are told that in China puss is considered to betoken ill-luck, and the display of sudden attachment to a family on the part of a feline stray is supposed to foreshadow poverty and distress, yet a clay likeness of a cat with a bob-tail like those seen in this country is frequently placed on the apex of a roof as a protection against maleficent powers. At the same time the animal is suspected of being in league with the Evil One, and is credited with meteorological prescience. For these reasons it is propitiated, and, as in ancient Egypt, its likeness forms a favourite charm.

Amongst other superstitions prevalent in China is the notion that, shortly after the birth of a child, some hairs of cats and dogs should be suspended for eleven days outside the door of the bedroom where the mother is lying. This prevents the noise of the animals from frightening the baby.

In this country also, according to tradition, people sometimes reverence the ghost of a cat. Spiritual communication is established by hanging the cat, after which seven weeks of occasional fasting and prayer are observed in its honour. A bag is suspended by its side, and offerings are made to it. It is asserted that the ghost purloins the neighbours’ property, and places the booty in the bag, and it is added, that as a consequence those who serve these cat-deities get rich very quickly. A high official in a certain district discovered that a considerable quantity of his store of rice had disappeared, and also learnt that behind his house dwelt a man who sacrificed to one of these cat-ghosts. He ordered that the devotee and the dead cat should be severely flogged, with the not unexpected result that this particular animal ceased for the future to exercise its power. A similar tale appears in Northern legends.

In consequence of her great powers of endurance puss is said to have nine lives, and perhaps that is a reason why at one time the poor creature was assailed and ill-treated so continually, for if one life was ended, were there not others in reserve? In Scotland it was believed that witches often assumed the feline form to facilitate the exercise of their evil influence over a family. On the other hand, in the West of Scotland that person was considered lucky to whom a male cat, on entering a dwelling, attached himself. In fact, a puss of any kind was always welcomed and petted. If, however, the animal became ill then (for it would have been considered unlucky for him to die inside the house) the custom was to remove poor pussy to an outhouse, put plenty of food there, and leave him alone either to recover or die. In Lancashire also it is believed to be unlucky for a cat to die in the house, but in this county the misfortune is prevented by the simple method of drowning the animal when it becomes ill. There is a peculiar superstition current on the Scottish Border according to which, if a cat or dog pass over a corpse, it is a presage of misfortune; in fact, in Scotland the animals are not allowed to approach a dead body, and to prevent the possibility of such approach the poor things are killed without compunction. In Devonshire, however, it is said that a cat will not remain in a house which contains a corpse, and stories are told of the disappearance of one on the death of an inmate, and its reappearance after the funeral.

To return to mediaeval superstitions. Certain characteristics were assigned to the second-born of twins— the power of detaching the spirit from the body, and an insatiable appetite [Some say both twins had this power]. The former helped the latter in that the child was able to take the form of a cat, and so could more easily commit depredations for the purpose of obtaining the particular food desired. Parents of twins were very anxious that puss should not be ill-treated, lest their own child should be a sufferer. After the age of ten or twelve the child ceased to indulge in this practice, and its exercise could have been entirely prevented, if at the time of birth a decoction of onion broth and camel’s milk had at once been administered to the infant. This superstition regarding twins existed among the Copts; it was of Egyptian origin, and probably an outcome of the belief in the transmigration of souls.

A very old saying, ascribed to an Athenian oracle, is that when puss “ combs herself it is a sign of rain, because, when she feels the moisture in the air, she smooths the fur to cover her body, and so suffer the inconvenience as little as possible ”; on the other hand, it is said that “ she opens her fur in the dry season that she may more easily derive benefit from any humidity in the atmosphere.” The superstition lasted long and was greatly extended, so that for a cat to show more than the ordinary tendency to sit by the fire, and with the tail towards it, to scratch the legs of the table, to sneeze, to lick her feet, to trim the whiskers and the fur of the head, to wash with the paw behind the ears, or to stretch the paw beyond the crown of the head, were severally to be considered as signs of rainy weather; belief in the last named dates from the time when the priests of the goddess Pasht flourished.

There is a Spanish saying that when the cat’s fur looks bright it will be fine the next day.

It may be noticed here that sailors believe, when puss becomes unusually frolicsome, it portends tempestuous weather; the same result would follow should a cat unfortunately be drowned, and they think that if a black cat comes on board it foretells disaster. However, at Scarborough in former days the wives of sailors fancied that by keeping a black cat the safety of the husband while at sea was insured; consequently anyone else had a poor chance of possessing a sable puss, as she was nearly always stolen by one of these women.

The idea that the cat under certain circumstances may be a harbinger of evil is the reason that in many countries it is kept away from children’s cradles. Another explanation of the objection that exists to the presence of a cat in a baby’s cradle is to be found in the notion that the animal would inhale the infant’s breath, and that death might ensue in consequence. It is, perhaps, needless to add that this impression has no real justification. On the other hand, it is current in Russo-Jewish folk-lore that, if a cat is put into a new cradle, it will be the means of driving away evil spirits from the infant.

The following are further interesting instances of superstition in connection with the cat, and are taken indiscriminately from the traditions of many countries. It some districts it was believed that all cats that wandered over the housetops in the month of February were witches, and therefore to be destroyed. The belief that “ great evil is in store for him who harms or kills a cat ” is evidently derived from the Egyptian appreciation of the animal, and, in addition, it was doubtless feared that hags would avenge any injury done to their familiars. When a cat washes herself, it is taken as a sign that a guest is coming; but if while so occupied puss looks at anyone, it portends that the unfortunate individual so regarded will be the recipient of a scolding. To keep a cat or dog from the wish to run away, it must be chased three times round the hearth, and afterwards be rubbed against the chimney-shaft; or, according to another mode, when the animal has been bought and brought home, it should be carried into the house tail foremost.

It is believed that if a maiden is fond of cats she will have a sweet-tempered husband. Another superstition holds that if a kitten strays into a house in the morning it presages good luck, but if at night, the reverse, unless the kitten remains as a countercharm. If in a house where a person is ill the cats bite each other, it foretells death at an early date. In Tuscany, if a man wishes for death, it is opined that a cat — i.e., the Devil in this form — approaches the bed.

A superstition that originated in Hungary and Tuscany avers that for a cat to be a clever thief, and therefore a good mouser, it must itself have been stolen. In Sicily there is a prevailing superstition to the effect that if a cat mews while the rosary is being counted for the welfare of outward-bound sailors, a tedious voyage will be the result.

English folk-lore informs us that kittens born during the month of May should be drowned; it was thought that if spared they would not catch rats or mice, and, in addition, that they would attract snakes and other reptiles into the house. A saying in Huntingdonshire runs “ A May kitten makes a dirty cat.” At one time it was a common belief that if puss were hungry she would eat coal, and in some districts the idea prevails to the present day. The tongue of the cat is rough, somewhat like a file, and it was supposed that if, by licking a person sufficiently, the animal drew blood, the taste caused it to become mad. A cat-call on the roof used to be considered as a token of death. If puss sneezed, it was said to presage good luck ” to the bride who was to be married on the following day; but a sneeze was also accepted as an evil omen, which foretold rain, and also colds to every member of the family. It was advisable to look well after pussy’s comforts, for it was believed that rain on the wedding-day showed that the cat had been starved, and in this manner the offended messenger of the goddess of love took revenge. Another superstition which connected the cat and weddings warned the credulous that the union would not be happy if, on the way to church, the company met either a hare, a dog, a cat, a lizard, or a serpent; as some people had full belief in such portents, care was taken to prevent the occurrence of such an ominous encounter. There are instances recorded when brides have fainted through terror as a result of meeting under the circumstances either of the above-mentioned creatures.

A gipsy dislikes a sable cat in his dwelling, as he considers it uncanny, and a thing of the Devil; he approves of a white cat, which he deems good, and like the ghost of a fair lady. However, it used to be believed that the bite of a white cat was more dangerous than that of a black one.

A formula for deliverance of a cat from the power of a witch was to make upon its skin an incision in the form of a cross.

Puss has sometimes been accused of want of attachment to people. A suggested ground for this is that the animal eats mice, which are credited with being the source of forgetfulness, and the fear that this imperfection is contagious is responsible for the report that up to the present day in Russia Jewish boys are forbidden even to caress a cat. Apropos of this association of the Jew and the animal, we may ask whether it is reasonable to assume that the dearth of reference to the cat by early Hebrew writers may be accounted for by their probable dislike to it, consequent on its intimate relationship to the religious rites of the Egyptians.