THE CAT : ITS CARE AND MANAGEMENT

BY MRS. LESLIE WILLIAMS

AUTHOR OF THE MANUAL OF TOY DOGS, HOW TO BREED, REAR, AND FEED THEM.

WITH FRONTISPIECE and 17 ILLUSTRATIONS in THE TEXT

PHILADELPHIA HENRY ALTEMUS COMPANY

1908

PREFACE

WHEN planning this little handbook, I desired to pay special attention to the diseases of cats, and it is therefore necessary to explain why, after all, not very much space is occupied in the consideration of this part of the subject of Pet Cat management. The fact is, that if cats are kept at liberty and fed on meat, they have no diseases apart from accident or injury. Such inherited troubles as some weakly kittens show are all, directly or indirectly, due to mistaken feeding and overcrowding. Now that the ‘boom’ in Persian kittens, which a few years ago caused a great many people to take up cats more for profit than because they loved them, is a thing of the past, over-production is ceasing, and in time, no doubt, all cats will be as healthy as Nature intended. In the meantime fresh air, liberty, and the natural diet of a purely carnivorous animal are worth all the drugs in the world for our pets.

With regard to the pictures in this book, I must acknowledge debts of gratitude for kind help to Mrs. Clark of Kyrie, Batheaston, Bath, Mrs. Higgens (Dick Whittington), and other ladies who have allowed their favourites to be depicted. The Ladies’ Field has also been so kind as to let me reproduce some excellent pictures.

M. L. WILLIAMS.

September 2, 1907.

CONTENTS

The Management of Pet Cats

Liberty

Food for Cats

Feeding Kittens

The Care of the Coat

Parasites on Cats

Breeding

Treatment of Breeding Queens

Kittens in the Nest

Complaints of Kittens

Training Kittens

Neuters

Showing Kittens

Showing Cats and Kittens

Preparing Exhibits for Show

Common Ailments of Cats

Colds

Skin Troubles

Mange

Eczema

Tuberculosis, Pernicious Anaemia, and other Wasting Diseases

Distemper and Gastritis

Wounds, Accidents, and Emergency Appliances

Appliances other than Medical

Abscesses in the Head and Toothache

Growths and Tumours

Ringworm

Congestion and Canker in the

Liver Disorders

Worms

The Rarer Diseases and some Abnormalities of Cats

The Cattery

Cats’ Houses

Cattery Life

The Different Varieties of Cats (Long-haired Cats)

Points of Long-haired Show Cats

The Chinchilla Persian

White Persians

Blue Persians

Smoke Persians

Black Persians

Tabby Persians

Tortoiseshell and Tortoiseshell and White, or Tricolour

Persians

Orange and Cream Persians

Short-haired Cats

Blue Short-haired Cats

Black and White Short-hairs

Tabby Short-haired Cats

Dutch-marked Short-hairs

Tortoiseshell Short-hairs

Manx Cats

Siamese Cats

Abyssinian Cats

How to begin keeping Pet Cats

General Hints to Cat Owners

Index

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

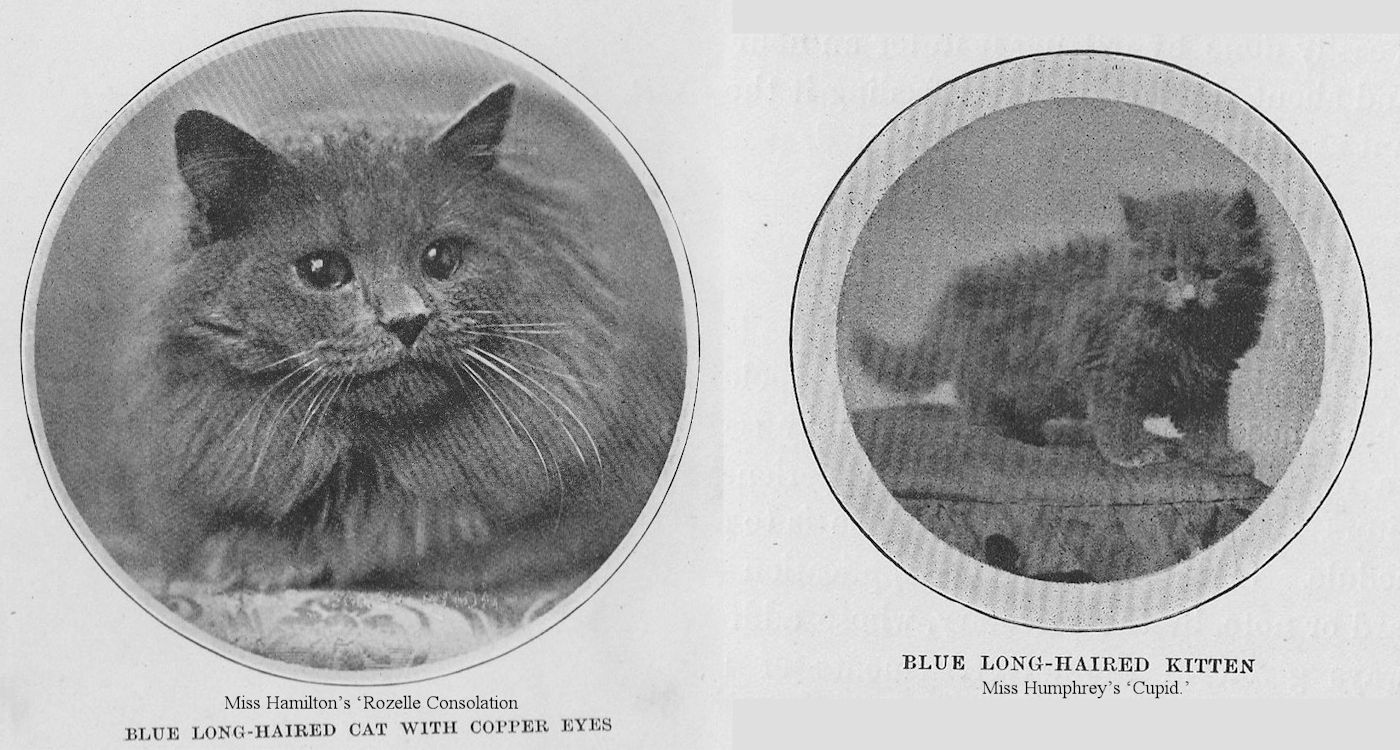

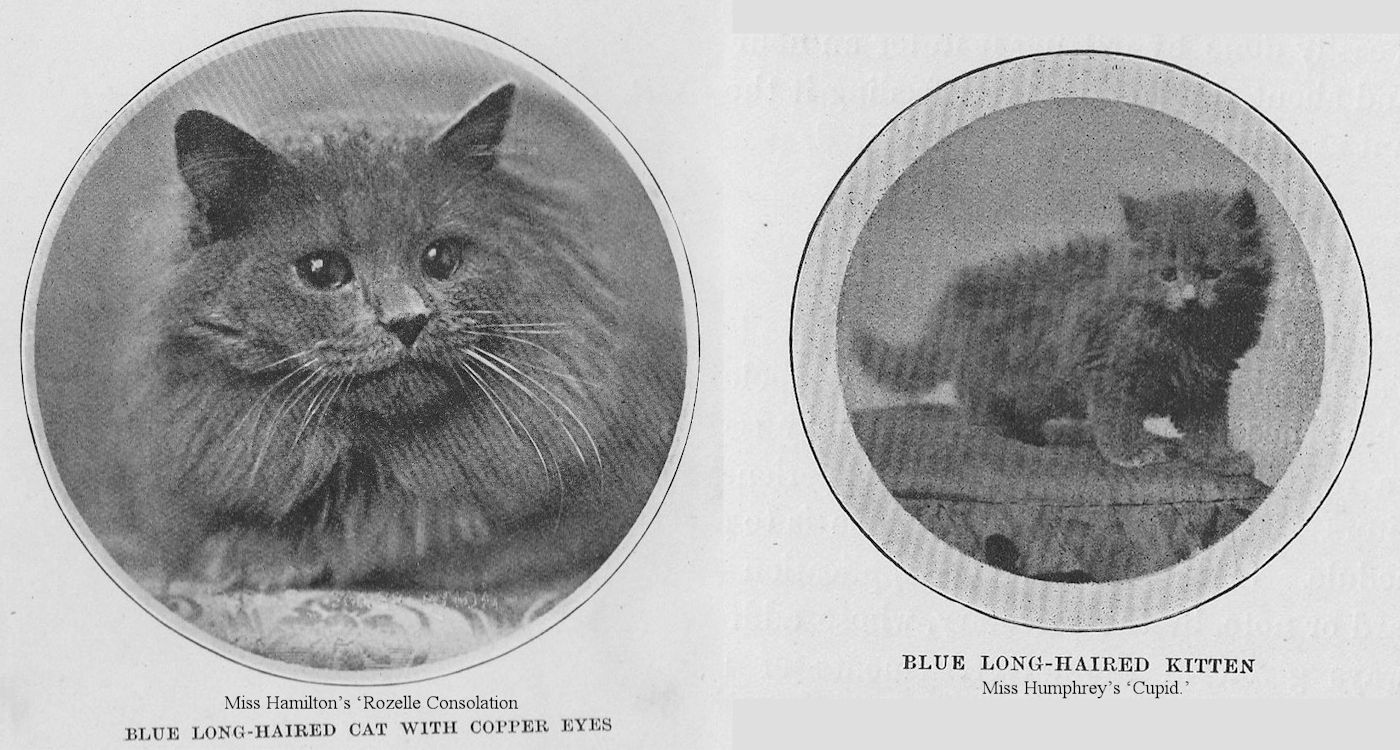

Blue Long-haired Cat with Copper Eyes (Frontispiece) - Miss Hamilton’s ‘Rozelle Consolation.’

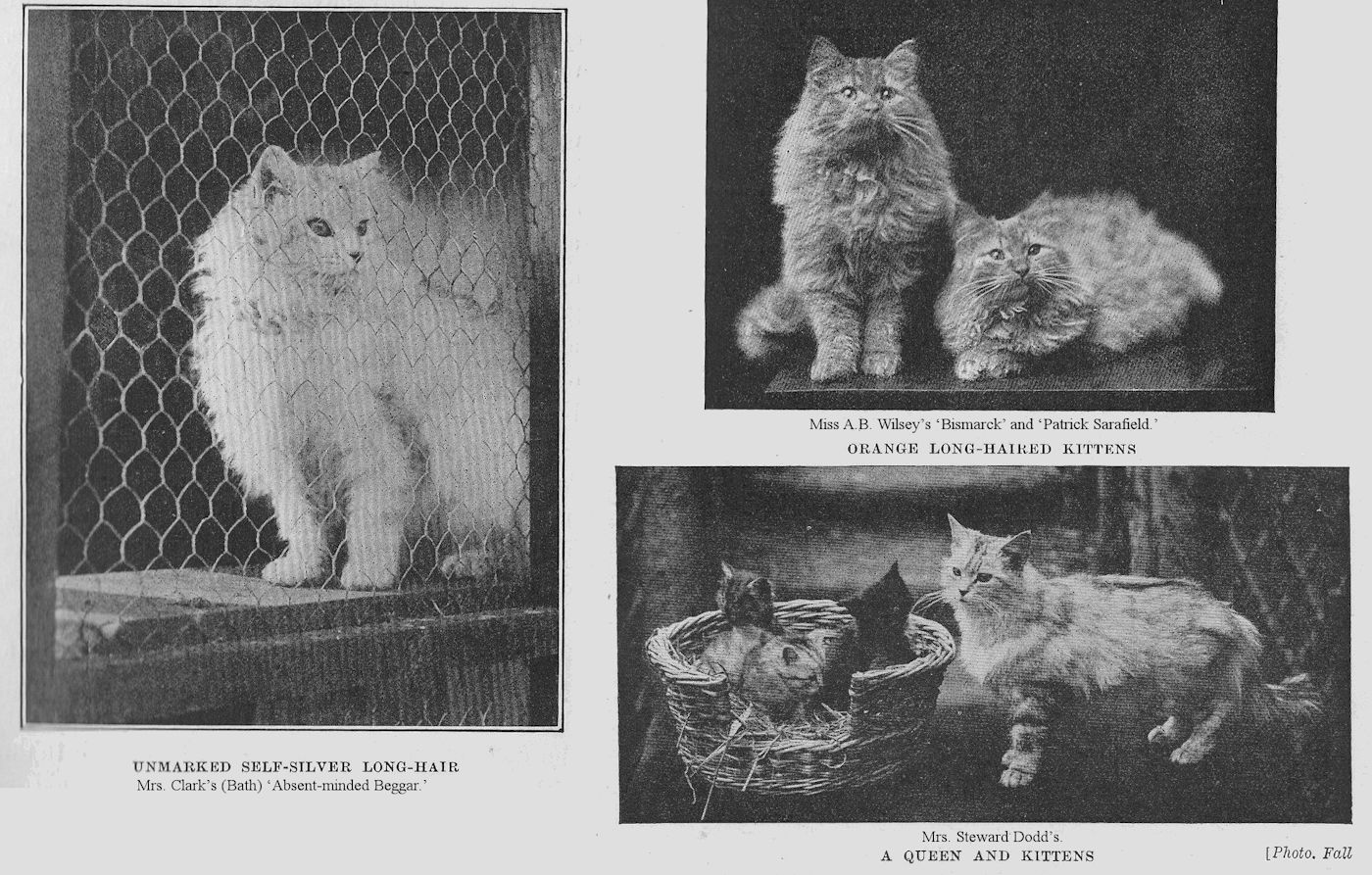

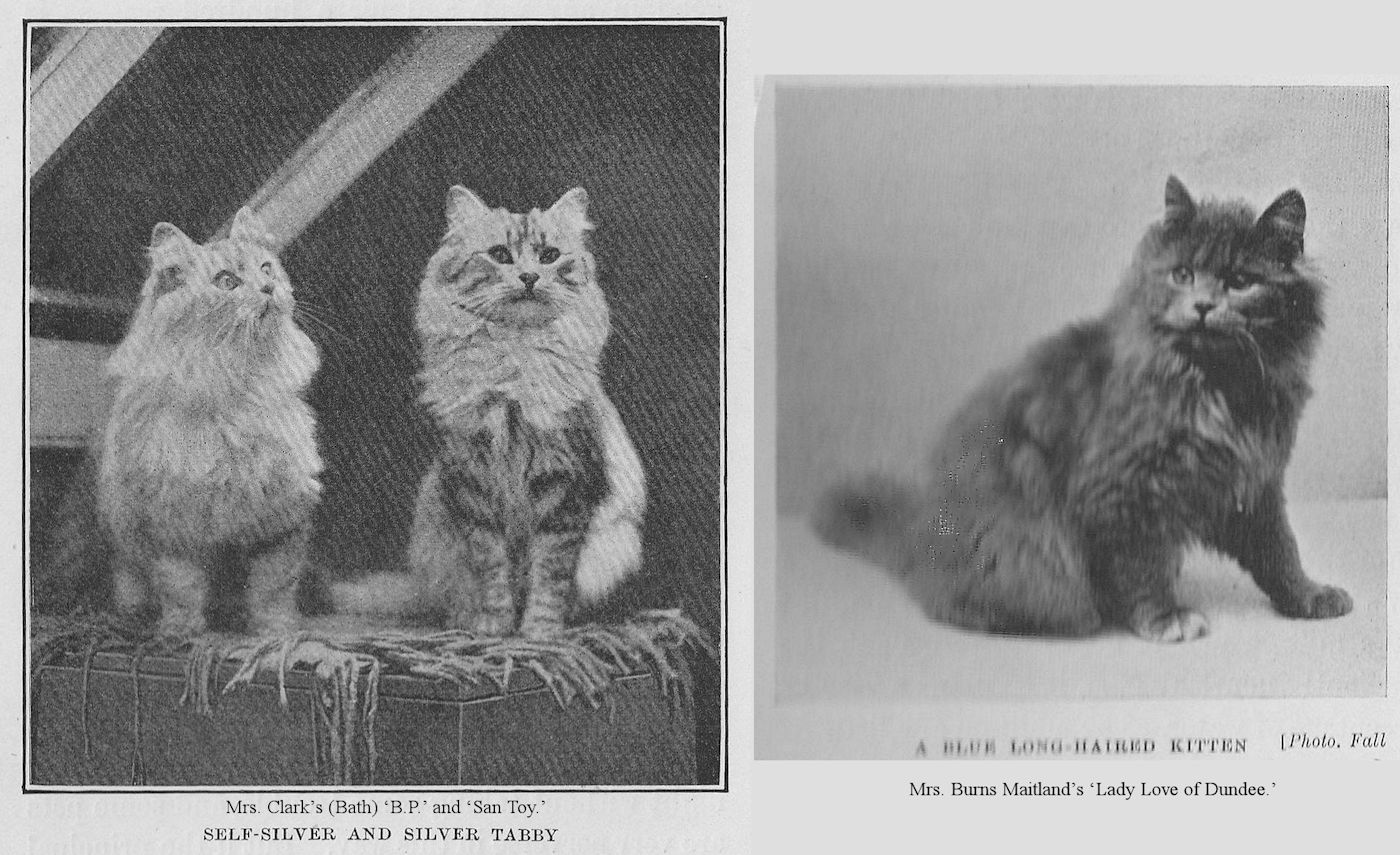

Self Silver and Silver Tabby - Mrs. Clark’s (Bath) ‘B.P.’ and ‘San Toy.’

A Blue Long-Haired Kitten - Miss Humphrey’s ‘Cupid.’

Unmarked Self-Silver Longhair - Mrs. Clark’s (Bath) ‘Absent-minded Beggar.’

A Queen and Kittens - Mrs. Steward Dodd’s.

Orange Long-haired Kittens - Miss A.B. Wilsey’s ‘Bismarck’ and ‘Patrick Sarafield.’

Blue Long-Haired Kitten - Mrs. Burns Maitland’s ‘Lady Love of Dundee.’

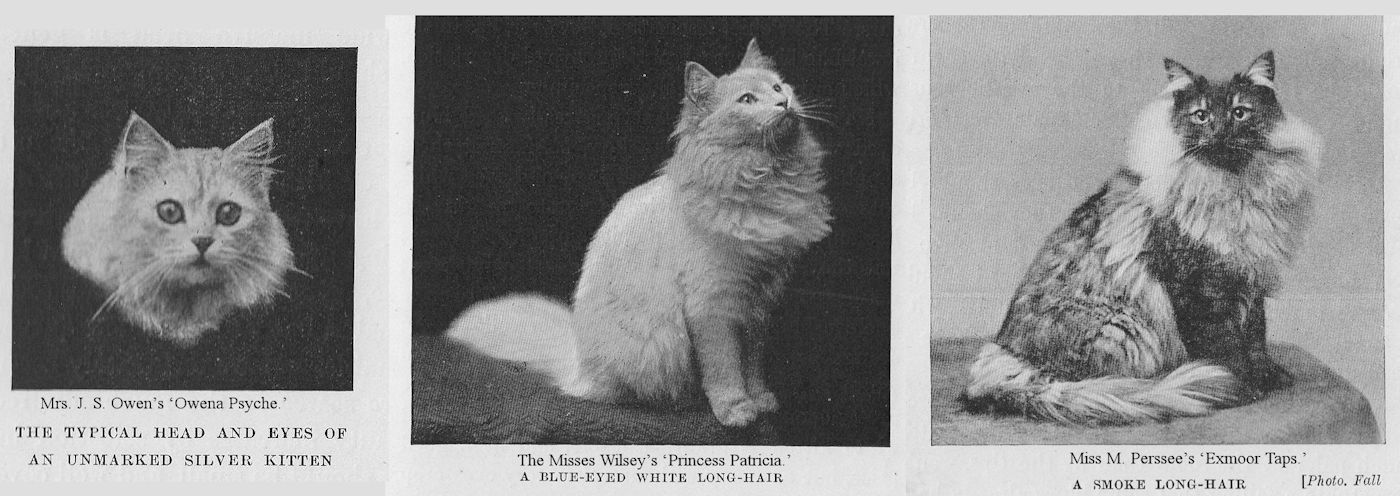

The Typical Head and Eyes of an Unmarked Silver Kitten - Mrs. J. S. Owen’s ‘Owena Psyche.’

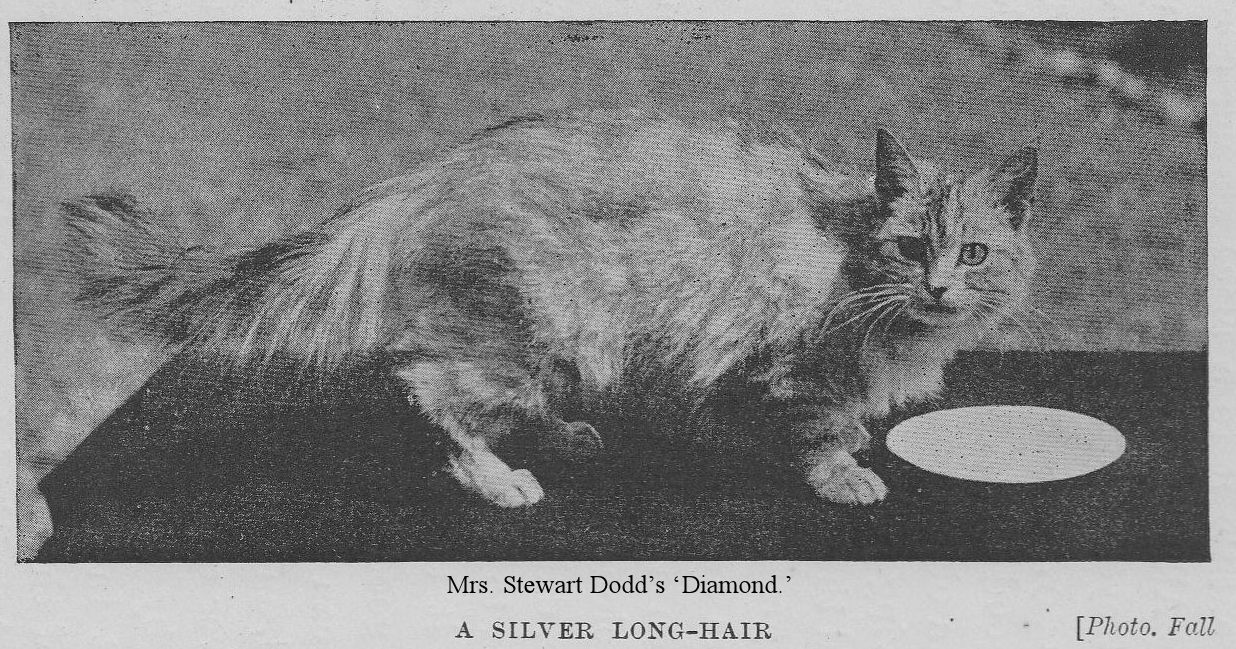

A Silver Long-Hair - Mrs. Stewart Dodd’s ‘Diamond.’

A Blue-Eyed White Long-Hair - The Misses Wilsey’s ‘Princess Patricia.’

A Smoke Long-Hair - Miss M. Perssee’s ‘Exmoor Taps.’

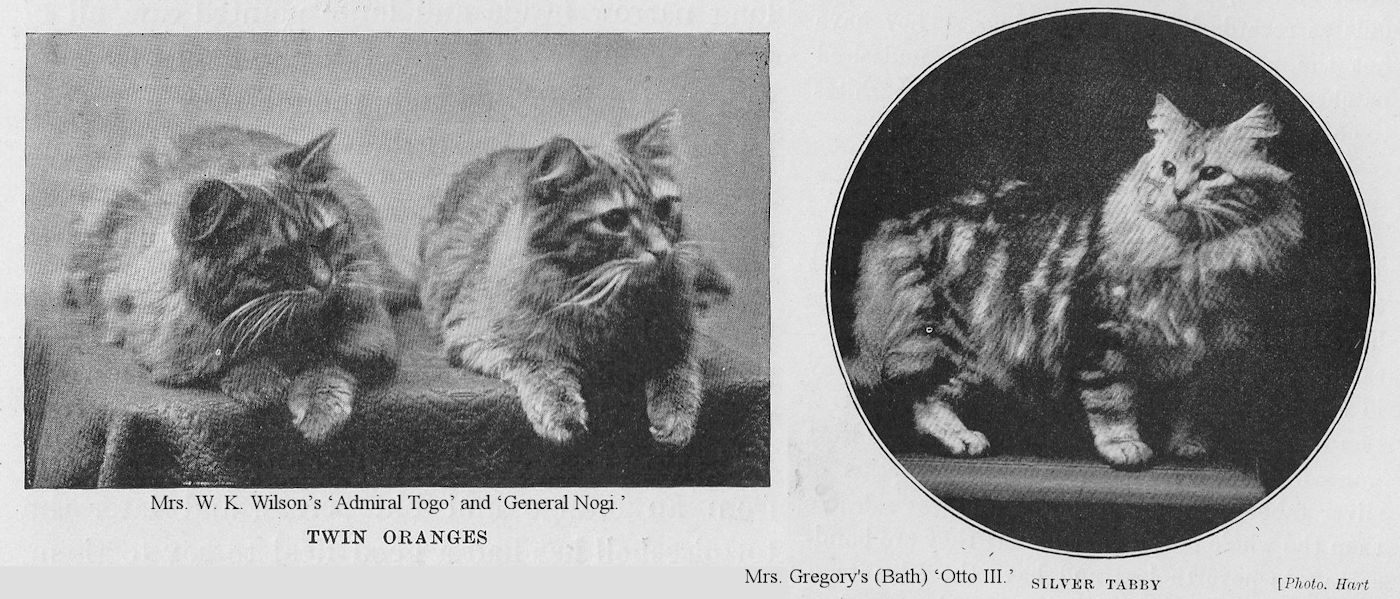

Silver Tabby - Mrs. Gregory's (Bath) ‘Otto III.’

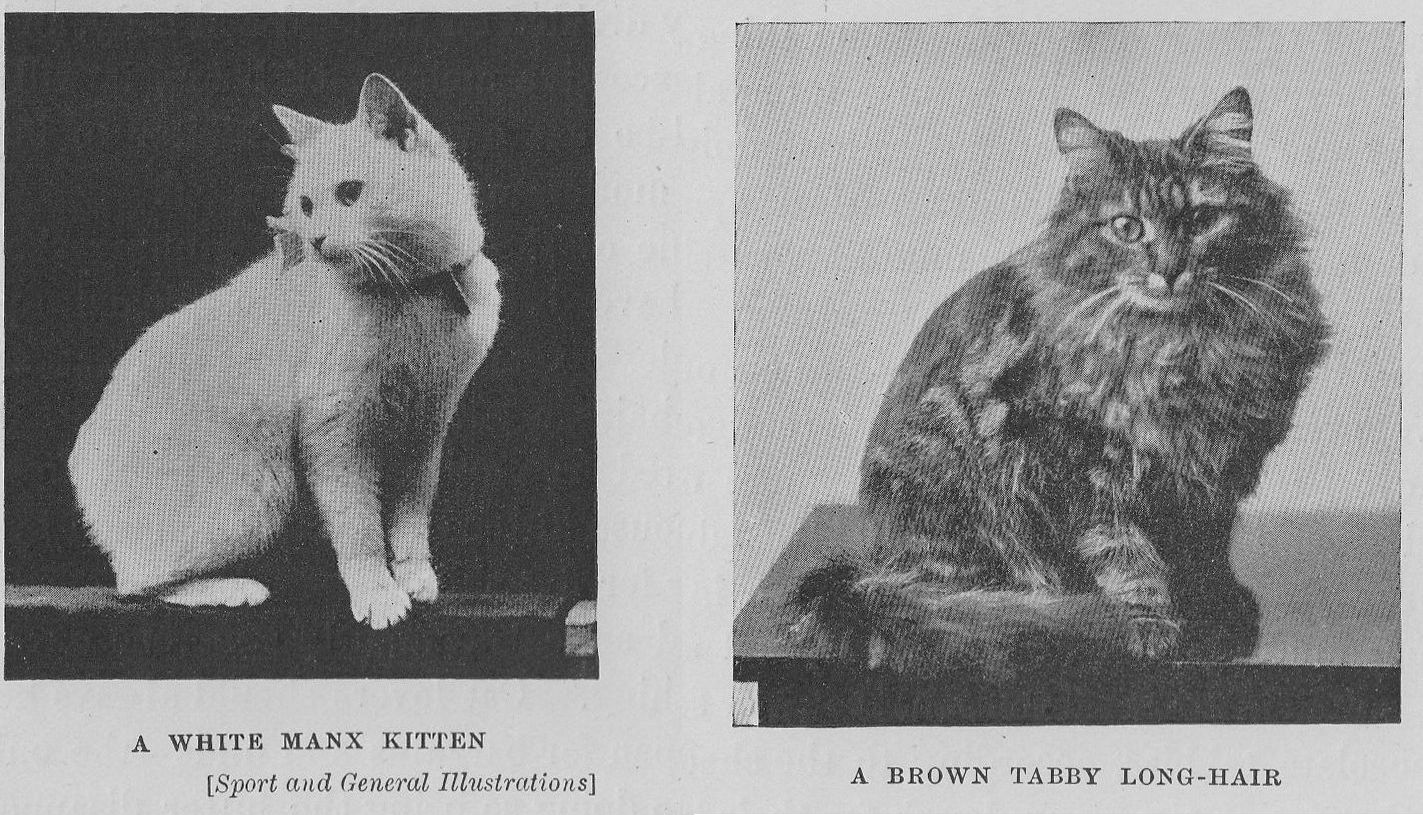

A Brown Tabby Long-Hair - Mrs. N. F. McLean’s ‘Clover.’

Twin Oranges - Mrs. W. K. Wilson’s ‘Admiral Togo’ and ‘General Nogi.’

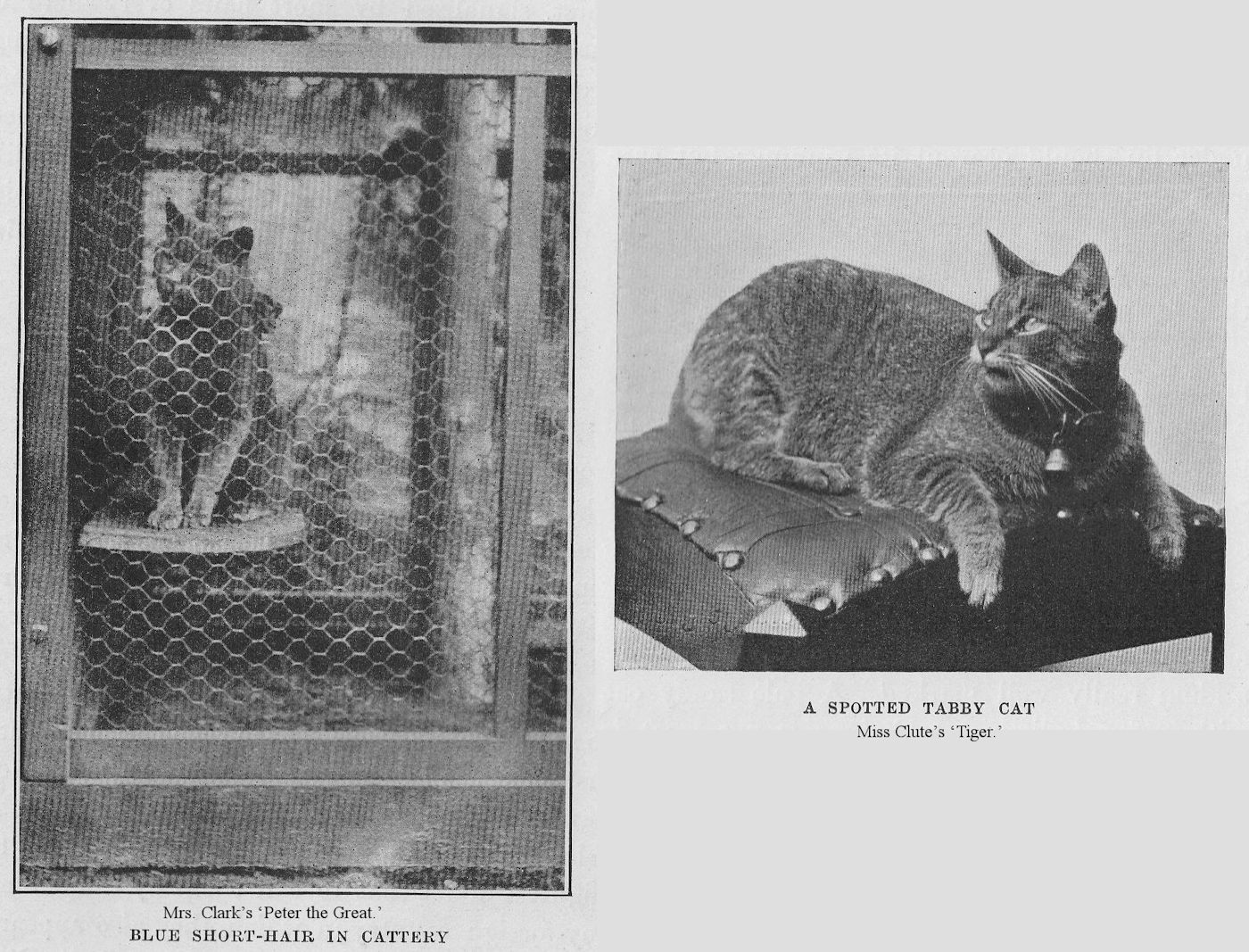

Blue Short-Hair in Cattery - Mrs. Clark’s ‘Peter the Great.’

A Spotted Tabby Cat - Miss Clute’s ‘Tiger.’

A White Manx Kitten - Mrs. Collingwood’s ‘Mona Elysee.’

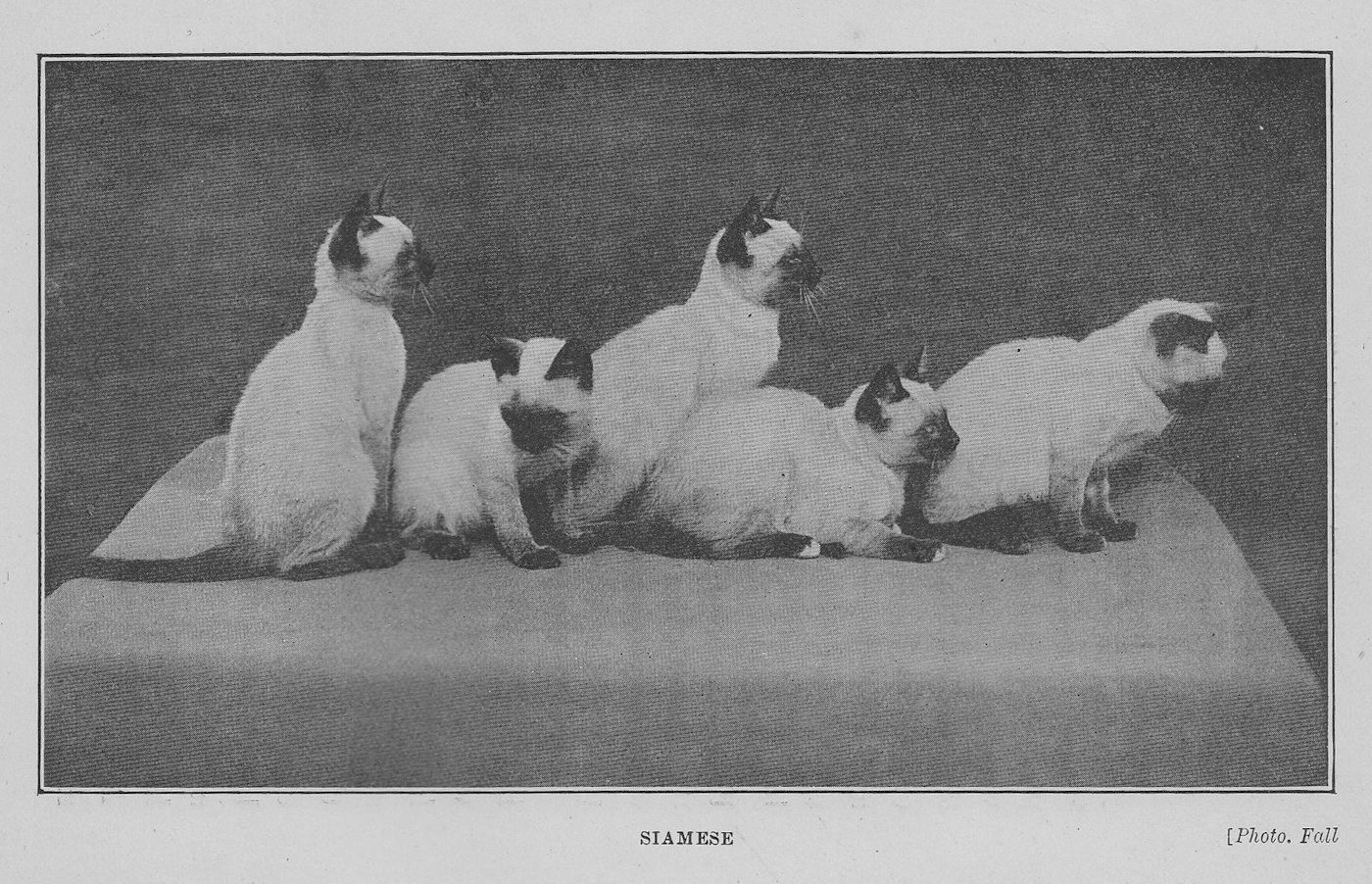

Siamese - Lady Marcus Beresford’s.

Note. — The cats shown in the illustrations are in nearly all cases well known as leading winners, and are all types of beauty in their respective varieties.

THE CAT. ITS CARE AND MANAGEMENT

THE MANAGEMENT OF PET CATS.

The ideal life for a cat, whether long- or short-haired, is one of liberty, combined with care and petting. Unlike the dog, who, except in the case of the hound breeds, has lost all feral wildness, the cat retains its instinct of independence to such a degree that constraint of any kind is bitterly irksome to it. When we come to consider the question of breeding, we shall have to face the fact that it is absolutely necessary to keep male cats in confinement, if they are kept at all, for they are quite impossible as pets at liberty. But where females — which in the cat world are always called queens — or neuter males are kept as pets, and allowed to have their freedom about a house and garden, they are at their very best and healthiest. Those who keep at most a couple of queens, mating them now and then to stud cats kept by other people, are the cat-owners who may most confidently look forward to making some small profit out of their hobby. At one time breeding Persian kittens in this way, by which the maximum results were obtained with the minimum of trouble and expense, was really advantageous, because there was a ready sale for the kits at remunerative high prices, about £3 3s apiece being a fair average. But so many people took up the hobby that overproduction spoilt the market, prices went down, and there was no longer the certainty of selling. At the present time nice, healthy, silver and blue Persian kittens will generally sell, but there is no assurance of finding many buyers for those of other colours, and, so far as the race of cats is concerned, it is just as well. They do not gain by being made articles of commerce to such a degree as to render it profitable for people to force them into the world in numbers too great to receive individual love and care.

Liberty.

While it is part of the ideal life for the cat to have full liberty, it must not be understood by this that she is to be left to take care of herself. No pet cat on which the owner sets any value should be allowed to stay out all night. This is particularly important from the breeder’s point of view, but even a neuter should be most strictly kept under supervision in this way. Being out and about at night cannot do the cat the least good in any way, and for a hundred reasons is undesirable.

Cold may be caught, and besides fighting with stray cats and the riff-raff of miserable neglected felinity that prowls the night, out pets may easily pick up contagious skin diseases that will give a world of trouble to sure. Diphtheria too, is a disease of neglected cats that healthy and wholesome pets may catch and bring into our houses, and even if this dreadful complaint itself is not experienced, a cat’s sore throat and cold is highly contagious to human beings. Again, poaching habits are immensely encouraged by night liberty, and once a cat, no matter how sleek and silken its fireside innocence of the day, takes to the enjoyment of sport by night, its final disappearance, or some dreadful misfortune of trap or snare, is inevitable.

Of course we cannot always get the cat in at night without taking some trouble, and some pets are very perverse in this way. But if the principal meal of the day is given in the evening, about six or seven p.m., pussy is pretty sure to turn up for it, and must then be captured and safely secured. In the daytime cats get nothing but good from being able to roam as they please, and if a large garden and country pleasure is available, so much the better. In towns, where the usual oblong, walled back-garden is all that we can command, it is generally quite worthwhile to go to the expense of wiring this in to keep off other cats and keep our own favourites at home. The run of a house and small garden is quite enough to constitute a happy liberty, so long as grass is obtainable. It is a necessity to the health of cats, but it need not be growing. A weekly bunch from the country, of the rather coarse broad-headed stuff called dog-grass, is easily arranged for, and can even be tied in a bunch and put tightly into a jar of water. Many cat owners grow their own cat grass by sowing the seed in shallow boxes of soil, and even canary seed, which springs up with magic quickness to fresh green blades is sufficient and appreciated.

Sunshine is life to cats, and, although they still pretend at times to the lofty aloofness that no doubt was a more leading characteristic in the race that shared ancient Egyptian reverence with the onion, they also enjoy and require a large share of sociality. At the time when a pet queen must be shut up she should never be condemned to a room without a window, but it should be remembered that she loves to bask on the sill in the sunshine, watching all that goes on in the street below.

Food for Cats.

Some very strange fallacies, whose foundation it is impossible to trace, are in existence, and apparently in the firmest possession of universal credit, on the subject of feeding cats. Probably nineteen people out of twenty, in spite of much good advice they might have taken to heart had they cared to follow the modern literature of the subject — pets of all kinds are now well and wisely written of in many papers — are still quite determined that the proper, the only, food for cats is milk and fish. As a matter of fact fish is by no means wholesome as cat dietary: to a pet that is fed on house scraps an occasional meal of fish will do no harm, but neither is it of much nutritious value. It does not contain the mineral salts and other elements, so largely present in meat, that the system of a carnivorous animal requires. A cat fed only on fish is bound, sooner or later, to suffer from anaemia and skin trouble, inseparable companions as they are. Milk is undesirable for adults because it is liquid, and the fully developed stomach of the cat is not adapted to digest or subsist upon liquid food. Putting a large bulk of liquid into the organ taxes and strains it to an extent quite inadequate to the amount of nourishment derived. There is more nourishing goodness in an ounce of raw meat than in many ounces of milk, and the stomach is neither dilated nor affected, otherwise than pleasurably, by its ingestion. From the trouble many people will take to argue in favour of, and to carry out, any possible scheme of dietary for the purely carnivorous cat other than that for which its organs were designed and adapted, one might suppose that they think themselves wiser than the animal’s Creator. That cats have been civilised, so to speak, has no value as an argument in favour of any unnatural diet. The difference between a wild life of hunting, gorging, and sleeping and a tame one of comparative confinement with provided food is appreciable, of course, but it has not altered the cat's anatomy of digestion. A meat diet does not ‘make a cat smell’ – this is another fallacy. The nearer the cat is to a state of fortunate Nature – of Nature without its cruel accidents – the healthier, and a thoroughly healthy cat is a very sweet-smelling creature as to skin and fur.

For cattery cats, raw meat, beef or mutton, and raw rabbit cut into joints with the fur left on, with plenty of clean water daily changed, is an excellent dietary. For pets, at liberty about the house, any kitchen scraps of meat that are not salt, or sour, or twice-cooked, are suitable. It is not necessary, while throwing these away, to buy fresh meat daily for the cat. But it is always well to let her have some fresh raw meat twice a week, and if she cannot catch a bird or a mouse now and then, an effort should be made to get her a rabbit, and to give it, as before-mentioned, with the fur on, and cut up into uncooked pieces. The fur, or the feathers in the case of a bird, has some specific action in the stomach and intestinal canal which is very beneficial. Cats do not, of course, swallow all the feathers of a bird, but the considerable quantity they do eat does them nothing but good, probably because the mechanical action, as the mass passes more or less unaltered through the digestive track, affords the natural stimulus of distension.

In some cases of illness a freshly killed sparrow will tempt a cat to eat when nothing else will, and may prove the turning-point for recovery; and perhaps no apology need be made for the prescription, considering the unlovable character of these mischievous little birds, for whom even the sentimentalist cannot find much to say. They are certainly not more useful or generally popular than mice, and the most ardent humanitarian seems hardened to the idea of a cat’s dinner being the mouse’s rightful end.

The amount of meat to be daily given to each cat varies according to the latter’s size and appetite. Many queens are most fastidious eaters, while neuters, as a rule, have hearty appetites and large frames to support. A long-haired cat requires more food, or food of better quality, than a short-hair, in proportion to the amount of coat it carries. An expenditure of vitality is needed to supply the hair-bearing follicles and glands, upon which long hair draws more than a short coat can.

A poorly fed, anaemic cat cannot possibly show that splendid bloom of condition that is the aim of every true cat lover to see in his pets. As a rule eight ounces of raw meat a day, divided into two meals, is quite enough for a large neuter, while a queen may be quite satisfied with six ounces. Cats in kitten must be liberally fed if they are hungry, but very often they lose rather than gain in appetite, and require tempting with dainties.

There are certain parts of meat that butchers, if approached on the subject of economical provision for pets, always suggest, and these are exactly what it is least desirable to give. Lights, or lungs, and throttles, for instance, are quite valueless, because so lacking in nutritive power. Liver is also innutritious, though it is likely to cause a bilious attack if given raw. Well boiled, it is somewhat aperient in its action, and occasionally useful in illness, both for this reason and because many cats are fond of it, so that a little grated boiled sheep’s liver, sprinkled over a meal of meat, may induce a shy feeder to eat when other temptations fail.

Beef is the best meat for cats, and where an ailing animal is concerned a little of the best rump-steak may be an extravagance that will save a good deal of dosing. Foreign beef, however, is quite good enough as a general rule, and foreign mutton makes a nice change; it must not, of course, be given in a frozen state. The beef should be kept in a warm place for some hours at least, and the mutton, after being slowly thawed, should be very lightly roasted, so that it still remains red.

It is false economy to spare kitchen physic in the case of even a cattery full of cats, for it takes the price of a great many pounds of meat to pay a veterinary bill, and cats are bad patients. Once let them get below par, and the door is open to a perfect Pandora’s boxful of ailments, always difficult to diagnose, and often far harder to cure. It may be added that popular as the cat’s-meat man undoubtedly is among the town feline population, many of whom never see meat on their plates at home, or taste it otherwise than from his skewer, horse-flesh is not a good cat food, even when healthy and wholesome. Still less is it to be desired when the horse affording it has been given physic before its death, or died of illness rather than accident; and as this is always a probability, cat owners who can afford to keep their pets properly should pay a little more for a better article.

FEEDING KITTENS.

When we come to discuss the feeding of kittens we shall find ‘many men, many minds’ thoroughly well exemplified. Almost every breeder of repute or experience has his or her own method, and naturally considers it the best. But there can be no question that in the case of the kitten, as in that of the adult cat, Nature is the safest guide. Her plan is to let the cat suckle her young ones until their first teeth are fully developed, when they at once begin to eat meat. During the short period when the mother’s milk is beginning to fail, while the kitten’s teeth are still not fully through, Nature’s plan was that the mother should, as it were, teach her offspring to eat by sometimes disgorging partly digested food for them, while at other times they would gnaw the prey she brought, and suck the meat juices without actually tearing off or swallowing any portion. A great many queens, however, have lost the instinct of thus teaching their babies to bite flesh, and as the mother’s milk is often less abundant than it would be in a state of pure Nature, we may have to fill up the hiatus for the space of two or three weeks or longer.

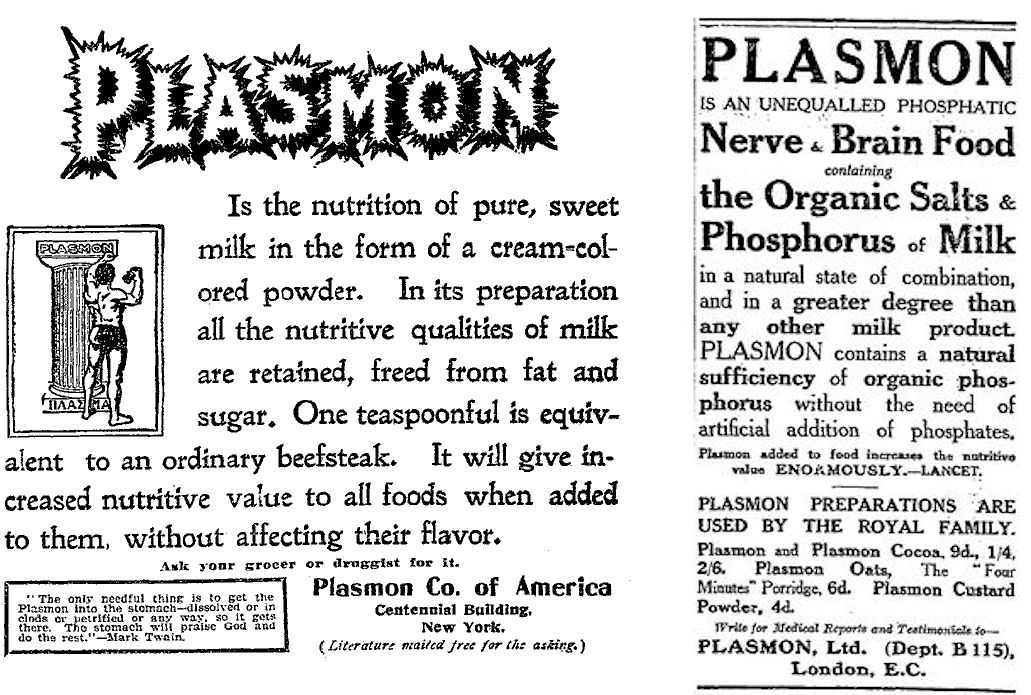

For this purpose no food excels a mixture of cow’s milk, cream, and plasmon. Cow’s milk — or goat’s milk, which is better — given alone is not sufficiently nourishing, as it contains a very large percentage of water. The addition of a little fresh raw cream or a beaten-up fresh egg and about-a teaspoonful of plasmon to each teacupful of milk brings it about up to the standard of mother’s milk. A little pure cane-sugar should be added also, just enough to sweeten it faintly. The milk and plasmon powder should be mixed and stirred over a slow fire for five to ten minutes until the mixture begins to thicken slightly; the cream should then be added in the proportion of one tablespoonful to a teacupful.

[Note: Plasmon is a milk protein powder manufactured from skimmed milk. It was invented by a German chemist and popularised in Britain from 1899. Plasmon now exists only as a brand name for a Heinz-owned Italian baby food containing plasmon.]

It may be objected that this is a fussy method giving a great deal of trouble. It is certainly more troublesome than it would be to feed the kittens on plain cow’s milk; but if we can take the trouble to breed kittens we may as well make up our minds to rear them afterwards as well as possible. It is upon their first start in life that their future depends, and a well-nourished healthy kitten is so delightful a possession that it is well worth a little extra pains to secure. Enough of the food can easily be made in the morning to last until night, and it keeps perfectly sweet and fresh over a night light in a food-warmer, so that a meal is all ready for the kittens at the proper intervals.

Kittens should not be stuffed at irregular hours. Their meals may as well coincide with those of the rest of the household, since once every four hours is quite often enough to feed them during the day while they are at this stage. As soon as they begin to eat meat, a small quantity of minced-up raw beef or other meat twice a day is amply sufficient. The exact amount will depend on the kits themselves, their size and appetites, but it is a mistake to overdo them with meat food. They may have as much, up to two teaspoonfuls at six weeks old, as they will eat eagerly without moving away, but the moment they leave the meat, or stop eating, it should be taken up.

As to the psychological moment at which to begin upon meat, it must be decided by each breeder according to his lights. As a rule the kittens give a lead themselves, for directly their teeth are ready to bite solid food they will make for their mother’s plate and try to share with her. After this they should be brought gradually on to meat, till they are having one milk meal and two meat ones daily.

Some little kittens have very tiny appetites, and a small teaspoonful of minced raw beef twice a day is quite enough to begin with. No idea that there is not sufficient bulk here need be entertained for a moment; the meat is concentrated nutriment exactly adapted to the small stomach that receives it. As the kittens grow older they will naturally want larger meals, but they should not be fed oftener.

They may gradually be allowed a nice variety of meat food, beef, mutton, rabbit, house-scraps of any fresh meat, chicken and game. But the plan of removing their food the moment

They cease to eat hungrily should always be followed.

That there is absolutely no comparison in point of healthy and perfect development between meat-fed kittens and those kept, as some people argue that they should be kept, on the utterly unnatural farinaceous food system, is very easily proved by demonstration, and it is open to anyone who doubts the wisdom of natural or meat-feeding to make the experiment of feeding one kitten thus, and bringing up another beside it on sloppy milk foods, porridge, bread and milk, puddings, and the rest of the cereal gamut.

These foods do,, of course, contain some small nutriment, or kittens fed on them would never live at all, and they certainly ensure the survival of the fittest, because the great bulk that has to be somehow or other got through the system in order to extract a feeble livelihood from these scanty elements of nutrition cannot fail to put a tremendous tax on the digestive system, a tax too severe by far for the weakly ones.

But a kitten that is busy fighting to keep alive on food it was never created to eat has no strength to spare for other purposes, and let but the slightest chill or shock or contagion approach it, it is down at once. Meat-fed kittens are far less liable to distemper, colds, and other bronchial and lung troubles, while digestive disorders, from simple indigestion to enteritis, visit them not at all. Lastly, they are infinitely cleaner in their habits, as will readily be understood, and very much easier to train to the house.

If the cat is a really good mother, and has plenty of milk, she will easily take them on until they are quite ready to eat meat, and in this case a short period of milk feeding is all that is necessary. This is the ideal upbringing. Kittens whose mothers are indifferent, or, as sometimes happens, without milk to give their offspring, can be reared on the milk and plasmon mixture by hand, at all events for a few hours or days, until a foster-mother, either natural or artificial, can be found; but it is a very troublesome task, and one not to be undertaken unless the litter is a very valuable one, in which case the wise breeder will have arranged beforehand that some reliable common cat shall be having her family at the same time. Fresh water is at all times necessary to both cats and kittens. The cat should have her drinking dish as scrupulously attended to as that of the dog.

THE CARE OF THE COAT.

Short-haired cats can, as a rule, look after their own jackets, and if they are well fed and not allowed to stay out at night and racket about with fighting toms and other bad company of the roofs and tiles, they will certainly do so admirably. It is in this matter that the short-coated cat excels as a pet. The long beautiful coat of the Persian is a joy, when it happens to be in perfection, but how short a time, unfortunately, does that perfection endure!

Some long-hairs are worse than others in the matter of moulting, but with most of them a much longer time is devoted to getting rid of the jacket and growing another than to the becoming wearing of the perfect article. The cat may be at his best, perhaps, for two or three months of the year; the rest of the time he is like the little boy who, in respect of mischief, was always ‘just a’goin’ in, th’else just a’comin’ out.' Neuters are more constant in coat than queens or toms.

It is not at all desirable that long-haired cats should swallow their fur, and this they are constantly doing unless they are properly groomed, and such coat as may happen to be loose daily removed by comb and brush. It is, however, an appalling task to comb a large, strong, self-willed cat — and cats are, one and all, horribly impatient of any constraint — that has not been accustomed from its youth up to this necessary attention.

Sometimes we may become possessed of such an animal, or even of one that has been neglected, and may be covered with tangles and hard cots and lumps of matted fur. The latter are sure to be thickest underneath, and sometimes are so hard and stiff as to form a perfect mattress under the unfortunate cat’s body. Before a good new coat can grow it is absolutely necessary to get rid of all this.

Two operators, wearing the stoutest possible gloves — what are known as housemaid’s gloves, made of thick wash-leather, will best answer the purpose, if securely tied round the wrists with tape — will be needed, one to hold the patient, and the other to clip away the mats with a pair of round pointed scissors. If the head and shoulders and front paws of the victim are well muffled up in a rolled bath-towel or woollen table-cloth, there will be a better chance of getting through the business without much bloodshed.

Some writers recommend softening the cots with warm water first, but this only prolongs the business unduly, and very little coat worth keeping can be teased out of them. It is better to do the thing thoroughly, pull them as far from the skin as may be without using the least roughness or force, and clip them away. By using round-pointed scissors we avoid any risk of snipping the skin, which it would be difficult not to do if the instrument had sharp points.

A soft brush with long bristles should be used for the daily grooming of long-haired cats. The ideal brush is that sold by dogs’ caterers for Yorkshire terriers. This has very soft bristles higher in the middle than at the sides, and brings out all loose and dead hair at once, without any pulling or straining at the rest. Kittens should be brought up to consider a daily grooming as inevitable as their dinners, when they will soon learn to regard the brush and comb with complete indifference, or even to like having their toilets performed.

PARASITES ON CATS.

Cats, and especially kittens, kept in neighbourhoods where the soil is warm and sandy, and also in the south of England, are always subject to fleas, particularly in very hot weather. Sometimes kittens, that are in every way well-kept and cared for, will nevertheless be found to be absolutely alive with myriads of these pests. They do not leave the cats, nor trouble human beings, as a rule, but still it is usually a great shock to the uninitiated amateur to find his pets in this condition. They may be so covered with fleas, that if they lie for a few minutes on a cushion or chair with a dark covering, it will be found, when they move off, to be powdered with a sort of whitish deposit like very fine sago, which, rightly or wrongly, is called ‘fleas’ eggs.’

Of course, no owner likes to have the cats in such a condition, but it is, all the same, almost impossible to clear off every one of the creatures, and next day the well-combed kitten may be just as bad as ever. The only thing to do is to persevere with the comb and the small tooth-comb, and to rub powdered camphor and flowers of sulphur, mixed in equal parts, into partings made all over the coat, and also round the neck and about the ears. An antiseptic powder called ‘raydia’ is also very useful for this purpose, and is quite harmless to the cat or kitten, besides being nicely scented. Cat owners living on heavy soils or in the north and east of England are spared this trial, and should be indulgent if they buy a kitten from someone who has to contend with the summer flea plague, and find it has not arrived without a few undesired companions.

Under no circumstances should either kittens or cats be washed with an idea of getting rid of fleas or other parasites. Combing, the cat being first placed on a chair or small wooden stool set in the middle of a shallow bath with a little hot water in it, will do quite as much, or more, good, while being washed would, at the very least, upset the cat terribly, and might make it very ill.

Some breeders tub their white or very pale-coloured cats before showing them, but only the most experienced person should attempt to subject any cat to so detested an ordeal, and one so likely to be followed by bad consequences. Leave well alone is an excellent rule with cats, for, once ill, they are always bad patients and may give endless trouble before they come round again.

Weakly cats and kittens, badly fed and anaemic, or healthy cats that have been in bad company, sometimes become covered with lice, small yellow or grey insects, which cluster about them, chiefly on the face, head, neck and shoulders, and on the legs. For these small tooth-combing, the comb to be frequently dipped in lavender water or Eau de Cologne — which must not go near the eyes, however — is the only local remedy, and the camphor -sulphur powder or raydia may afterwards be rubbed in, and later brushed out.

Occasionally a cat may pick up these parasites in a stable, as ill-groomed horses not infrequently have them. They do not irritate their host, nor cause any inconvenience, neither can they live on human beings, but they are troublesome because they lay eggs in the form of minute nits firmly attached to the hairs of the coat, and these are not affected by any treatment, but must be attacked with the comb as they hatch and keep up a supply.

The only other external parasite that cats suffer from is a very minute white insect, invisible to the naked eye, that sometimes infests the roots of the external ear, causing considerable irritation. It is easily got rid of by means of a dressing of sulphur ointment.

No ointment nor wash containing mercury, either in the form of the green or yellow oxide or otherwise, should ever be allowed to touch a cat, neither should carbolic nor any of its derivatives be used for them. Mercury is a most dangerous and highly unsuitable drug for use on either dogs or cats; it is readily absorbed into the system, and the mischief it sets afoot may only be realised after months of suffering, and may end in incurable disease. Carbolic acid and its phenyl and other derivatives are exceedingly valuable in canine practice, but for some reason they are desperately toxic to cats, and should be most carefully avoided, otherwise we may get rid of

a few skin parasites, or some unimportant lesion, at the cost of an attack of enteritis or intestinal inflammation that will cure the patient for ever of all the ills of this weary world.

BREEDING.

About the only advantage of the cattery, or system of keeping cats in specially built houses, to which they are confined, is that the worry of keeping watch on queens and shutting them up when in season is avoided. Where pet queens are kept about the dwelling-house, and at liberty, we get far better results from breeding, and both cats and kittens are much healthier and more intelligent, but we may expect a good deal of trouble in keeping their affairs arranged to our liking and avoiding the results of independence — which is to say, litters of half- breeds.

No two queen-cats are exactly alike in their ways. Some will come in season perpetually, perhaps every month or so, while others only think of breeding once or twice a year. The latter is the normal state of affairs. First the cat becomes restless, then she takes to sitting at the window and doing what can only be clearly described as ‘yowling’ — a peculiar melancholy mewing, long drawn out and harassing. Then she rolls about the floor, and to those who have had much to do with cats is sure to betray unmistakably what is in her mind. She usually continues thus for about a week or ten days, sometimes for as long as three weeks, and is at the first ready to be sent away to visit the stud cat.

People who only have two or three pet queens will never find it worthwhile to keep a stud cat of their own on the premises. These animals are, of course, quite impossible about the house, and, if kept, must lead a cattery life, each in its own separate abode. A really good stud cat of popular colour that has done some winning is a profitable possession, but the profit is, to some minds, dearly bought. Visiting queens are an endless source of worry, and, in short, the cat fancier who successfully manages one or more stud cats and their affairs must be an experienced enthusiast, and is deserving of the warmest gratitude from all owners of pet queens, who only want pleasure, amusement, and perhaps small profit, without hard work or any unpleasant tasks.

The fees for stud cats vary from 10s 6d to 30s, a guinea being the most usual sum. Most owners of stud cats are willing to give a second service should the first prove fruitless, and this is a stipulation that it is always fair to make beforehand. The journey alone may upset a young queen, or the inexperienced breeder may be forgiven, for once, if the queen is sent not quite at the right time. When, however, the breeder really does understand the ways of queens, it is inexcusable to send them off ‘on the chance,’ perhaps again and again, for queens that are really not wishing to breed spoil the stud cat, and give great trouble to his owner.

A cat that is to be used for breeding should always have, as a matter of course, a proper travelling-box or basket, chosen in good time, roomy, strong, and with a neat and secure fastening. A wild search and scramble, at the last moment, for something to send the cat away in is sure to result in trouble. She may escape on the way; she may be cramped and very uncomfortable in too small a box, or a very costly traveller in one much too large and heavy; lastly, the owner of the stud cat cannot be expected to be responsible for, or to supply, deficiencies in the packing of visitors.

A draughty, cold package is worst of all, as it may easily mean death for the traveller. Unlined wicker-baskets should never be used; but a well-made, close-woven, buff wicker-hamper, with a rounded lid, that has a handle at the top, with a removable lining of good all-wool flannel, and a secure buckled strap round it, is a comfortable and efficient article for the purpose, and not expensive, either to buy or to send about. Before starting, that is about two hours before, the cat should have a moderate meal of underdone meat. On no account should a large meal be given immediately before she goes, or she will certainly be sick on the way.

Breeding for colour is a matter that can only be properly considered from a scientific point of view, but this matters the less, as it is only in the procuring of tortoise-shells that it is likely to be a subject of interest to the average cat-owner. To breed a tortoise-shell tom is the as yet unrealised ambition of many, and crosses of blacks, tortoise-shells, and oranges have been repeatedly tried, and though but little success is recorded, this formula is undoubtedly somewhere near the mark, and might repay further experiment by experienced breeders.

Cats of self-colour, however, are, or should be, bred to their own colour — a blue to a blue, a black to a black, and so on. It is a very great mistake for beginners to plunge wildly into chance mixing of strains, by which means they are sure to get kittens of bad or indeterminate colour.

What is necessary in choosing a stud cat is to ascertain that he is perfectly healthy, not over-worked, and possesses points that may correct any faults in the queen. Thus, if the queen is a blue or a black that has pale-yellow eyes, a mate should be sought who excels in the deep orange colour desired in eyes. In the case of chinchillas or self-silvers, a great deal of the undoubted delicacy of cats of this colour may be ascribed to the fact that stud cats sufficiently perfect in absence of shadings and black hairs are few, and the popular ones have to work harder than is the case in other colours where there is abundant choice of excellent sires.

Queens should not be allowed to breed when out of coat, nor to have more than, at the outside, two litters in the year. If either parent is out of coat at the time of mating, the kittens are likely to suffer from constant loss of coat, and of course this tendency is much increased if both parents should be moulting when they meet. One occasion of meeting is quite sufficient, as a rule, though some breeders prefer to put the two together twice at a day’s interval.

TREATMENT OF BREEDING QUEENS.

Queens in kitten must be carefully looked after. They should never be lifted or handled in any way; but it is quite unnecessary to restrict their liberty, as they do not hurt themselves by jumping up or down, no matter how active they may be: this is owing to the elasticity of their movements.

They require liberal feeding, and if the appetite is not naturally good it must be tempted. Drugging is to be sedulously avoided. If the queen is healthy, and getting plenty of amusement and gentle exercise, it is most unlikely that, there will be any difficulty about the coming of the kittens. The only contretemps that is at all common is the mother’s failure to nurse her infants, which now and then occurs. Sometimes she actually has no milk, and sometimes she may, apparently, take a dislike to her family and refuse to notice it.

Having this possibility in view, it is always well, especially in the case of first kittens, to have a foster-mother ready, whose time of kittening should be, if possible, a day or two before that of the more valuable cat. If the foster — a common short-haired cat of a kind and motherly disposition is best — has lived a few weeks with the defaulting mother, there will be no quarrels.

The kittens should be gradually mixed, so to speak. The new family must not be hurriedly sprung upon the foster, but while she is out of the way one or two of her own should be removed and the valuable kittens substituted, first rubbing them against her own kittens so that they may not smell strange to her when she returns.

A valuable cat for her own sake should not bring up more than two, or at the very most three, kittens at a time, and therefore, even if she be the best of mothers, a foster is always useful, since few breeders have the strength of mind to destroy embryo champions, and so reduce the claims upon their pets.

Cats have nine weeks, or sixty-three days, of gestation, but kittens are often born a day or two before their time, and are not at all the worse. If, however, the cat goes beyond the sixty-three days, though obviously in kitten, and if she seems uneasy, veterinary advice should be sought. It is a great mistake to give aperients, such as castor oil, before kittening, and no amateur attempts at midwifery should ever be made with cats, as they usually resent interference very strongly.

Even if it does any good at the time, which is unlikely, it is almost, certain to set them against their kittens, and may mean desertion or even cannibalism, a thing that is unfortunately not unknown.

Some queens before kittening are extremely fidgety, not to say annoying. They will wander about making all manner of investigations in the most unsuitable places for depositing the new arrivals.

Considerable tact is needed, because if a self-willed and petted cat makes up her mind that the spare bed and no other place will suit her, she may resent any attempt at removal or disturbance very deeply. A wooden box with sides about eight or nine inches high, containing a nice bed of dry warm hay or a piece of soft flannel, which should be changed for a freshly aired and warmed clean piece during the mother’s first absence from her litter, is the best provision for kittening. It should be put in some secluded place, such as the bottom of a dry cupboard, whose door must be fixed slightly open, so as to preclude any fear of puss sharing the dreadful fate of Ginevra, or being shut away from her offspring.

Nature teaches the expectant mother not to eat much for a few hours before her kittens are born; and some cats are always sick shortly before the event. As soon as it is all over, the mother should have a good saucerful of warm gruel, made with Robinson’s groats and milk, and slightly sweetened. A few hours later she may have her usual meal of meat, and after this she will require very liberal feeding, and, indeed, cannot well be overfed during the suckling period.

It is very important to the health and size of the kittens that they should be nursed by their mother as long as possible, and to nurse them will do the mother no harm at all, provided she is thoroughly well fed and there are not too many in the family. As before stated, it is obviously bad for the cat to rear too many, and it is also bad for the kittens. It is much better to have — even supposing a foster-mother cannot be found, and some of the kits must be destroyed — two fine large healthy kittens than four or five weaklings. The majority of breeders, who wish to make a little profit out of their pets, find female kittens unsaleable, and may just as well destroy them to begin with as give them away later on, perhaps to doubtful homes, and with the chance of their further spoiling a market that is already over-crowded. There is no cruelty in drowning day-old kittens in warm water, for their spark of vitality is very tiny, and they have no developed consciousness.

KITTENS IN THE NEST.

For the first three weeks of their lives properly cared for kittens, with an attentive mother, should give no trouble at all if they are healthy. If they are not healthy it is much better to destroy them, as a kitten that has had a bad start in life is very seldom worth anything later on, and only has a miserable existence to look forward to. The bed on which they lie should be looked after, and a clean warm flannel given when necessary. If the cat is attending to them properly they will, very soon after birth, be quite dry and glossy, losing the wrinkled appearance they have when, they first appear in the world. Kittens that retain this thin baggy look, and that cry, constantly, are not being adequately fed, and must be transferred to a good foster-mother if they are to do any good. A small dog will generally rear kittens very nicely, though the converse state of things, that of a cat taking to puppies, is much more usual; and, of course, cat fosters are generally much more readily obtainable. Still, if there is a litter of toy puppies about, a kitten usually thrives splendidly under canine care.

Great care must be taken that the box containing the kittens is not visited by draughts or chills. The enclosed under part of the dresser in a warm kitchen is generally a good place for it, but wherever it is put, the temperature must be even. If a small room in the house can be floored with linoleum or cork carpet and given up to the cats as a place to keep their families, so much the better. In winter a fire will be needed, or some kind of hygienically planned oil-stove, as all young things need warmth. The mothers should not be, shut up in the room, but allowed to go in and out as they please. Some cats so resent coercion of any kind that the mere fact of being shut in with their kittens turns them against their offspring.

COMPLAINTS OF KITTENS.

The great danger of draughts to young kittens in the nest cannot be exaggerated. ‘Bad eyes,’ those bugbears of breeders of show stock, may easily result from the slightest chill. Kittens may, and frequently do, develop ophthalmia neonatorum spontaneously, and merely from inherited weakness, but if draughts are allowed to play about them they are sure to go wrong in this or other ways, but most often thus.

An inherited strumous tendency that leads to inflammation of the eyes also often caused this symptom to develop a little later, when the kittens have left the nest, and this latter form of the trouble is intensely contagious and often very difficult to cure. If in litter after litter by the same parents we find eye trouble shows itself either in the first weeks of life or later, it is safe to conclude that one or both of the parents is strumous and unfit to be bred from. Should the mother appear perfectly healthy, she should be tried again with another sire; but should the trouble again recur, she must be held guilty of the strumous taint, and no longer used.

[note: strumous means scrofulous and referred to a variety of diseases with swollen glands including thyroid conditions and tuberculosis]

It is a wicked thing in itself to cause the bringing into the world of unfit and unhealthy creatures, setting aside the selfishness of desiring to make a profit by doing so. There will, of course, while the world remains this side of the millennium, always be breeders whose only thought is to produce and sell as many kittens as possible, no matter what disappointment they cause their buyers, nor what diseases they carry with them to infect other peoples’ healthy stock; but no one who really has true affection for such charming pets as healthy and happy cats can be, should let any false sentiment promote the production or survival of the unfit, to be a misery to themselves and their owners.

Bad eyes, when they are curable, which is often not the case if they arise from constitutional weakness, will generally yield to either boracic, zinc, or lead lotion. Any chemist knows the proper formulae for these, but as a rule, unless requested not to do so, will make them up with rose water, whereas for animals they are best made up plainly with distilled water. It is never possible to say which lotion will best suit individual cases, and they should be tried in turn or alternated.

Bathing, either with lotions or, as is often advised, with hot water or milk and water, is a great mistake. If the eyes are closed and the lids glued together with wet pus or matter, use a small pledget of aseptic dry cotton wool, to be had at all chemists, to remove the stuff, and burn the pledgets immediately. If the pus is dry and hard, moisten the pledgets with hot water, coloured pink with permanganate of potash, but only just sufficiently to soften hard matter, not to wet the face at all. If the hardened pus resists, smear the lids with boracic ointment and leave for a few minutes, then clear all the ointment away carefully with a pledget. As soon as the eye is cleaned from pus, drop into it two or three drops only of the lotion, using for the purpose a small all indiarubber bottle syringe. Do not touch the eye or lids with the point of the syringe, as, if it becomes contaminated with the septic discharge from the eye, it will infect any other kitten it touches. The eye should be treated with a drop or two of lotion every two or three hours. Supposing one kitten only of a litter shows symptoms of eye affection, it is worth while to take a good deal of trouble to segregate it and prevent, if possible, any contagion from affecting the others, for the patience of a greater Job is required to see a whole litter through an attack of conjunctivitis or ophthalmia.

Diarrhoea from chill or unsuitable feeding is about the only other frequent ailment of kittens, if we except common colds, to which they are as subject as babies of our own race.

Distemper, of course, carries off its thousands, but it does not come spontaneously to healthy meat-fed kittens. It comes with strange kittens we buy, or by contagion from a show, or by some side wind or other.

Diarrhoea is almost unknown in meat-fed kittens, but a very everyday affair among those fed on sloppy milk and cereal foods. It is caused in this latter case by flatulence due to indigestion, and over-distension from flatulence, being extremely painful, may make the kittens cry very pitifully. The obvious remedy is to change the absurd milk pudding and porridge for bi-diurnal small meals of finely minced raw meat, immediately after each of which a one- to three-grain pill of carbonate of bismuth may be given. In some cases an intestinal antiseptic, as an eighth to a quarter of a grain of beta napthol, given every four hours in pill form, is most efficacious.

If the diarrhoea is from chill, which is pretty sure to be the case if the patient is meat-fed, a piece of soft flannel should be put round the body and sewn down the back, and the kitten should be kept in one room quite secure from draughts. A teaspoonful of pure olive oil with a few drops of good brandy may first be given, and then the bismuth pills immediately after food. Diarrhoea in both cats and kittens may be set up by giving meat that is not perfectly fresh, and the greatest care should be exercised in seeing that this does not happen, as this form of diarrhoea is quite likely to end in peritonitis and death from ptomaine poisoning. Colds in both cats and kittens are very infectious for human beings, children especially. They must run their course, but a cat’s or kitten’s sneeze bears out the old tradition of calamity, for the cold is quite likely to run through the house when puss begins it. The little room on the sunny side of the house, with the linoleum floor and two or three comfortable old armchairs, is how more needed than ever as an isolation hospital, and the moment a sneeze is heard, away to it with the patient. A few days’ warmth and seclusion should follow with extra good feeding, and, for kittens, one grain of saccharated carbonate of iron and a quarter of a grain of sulphate of quinine made into a pill, twice a day. Full-grown cats may have three grains of the iron and half a grain of quinine. The pills should not be pearl-coated, as if they are, they are apt to pass unchanged through the digestive system.

Kittens and cats often suffer from sore throat with cold, and in addition to the above treatment, if the kitten is seen to swallow a good deal, its throat may be well rubbed with a little Elliman’s embrocation, or a trace of opodeldoc liniment, and adorned with a piece of red flannel — an old wives’ remedy, that is nevertheless, in this case, worth all the poultices in the world. A cough, or cold on the chest, should be similarly treated, but with a chest protector of flannel carried between the front legs and tied round the waist by tapes. When the time comes for those things to be left off they should be first loosened and then removed while the patient is still in hospital, so as to avoid chill. A sick kitten or cat always goes to the draughtiest place it can find, and may usually be looked for on the window-sill, or plastered against the crack under the door; therefore the cats’ hospital should have a precautionary wire-netting all over the window and a good thick mat outside the threshold. The beginnings of kittens’ ailments should always be most carefully watched, and any unusual dullness or sleepiness is particularly suspicious.

Teething fits are not at all uncommon in kittens, and generally not important. The afflicted one should be taken to a perfectly dark and quiet place, and a cold sponge may be applied to its head. Bromide of potassium, in three-grain doses twice a day, is the only drug that is recommended, but if the fit passes off quickly, it may not be required. An unhealthy kitten may go on having fits, at first slight, then gradually merging into epileptiform attacks, and finally into actual epilepsy, and when this occurs cure is hopeless.

TRAINING KITTENS.

For every reason it is much better to have only two or three kittens, at most, on the premises at one time. Where there are more, even if they have the run of house and garden, some illness is nearly sure to break out sooner or later. For instance, one kitten may have a slight cold or a trifling attack of diarrhoea, which, if it ended there, would be nothing. But it goes the round, and one or more of the other kittens is pretty sure to have it badly, and then they are all weakened, and the door is opened to further disaster. People who must keep cats in numbers should never lose an opportunity of placing their kittens separately, even if they have to pay for them as boarders, in families where they will be brought up and well looked after as the only feline pet of the establishment, for they will do infinitely better so, or in couples, than where there are more. It is so very pretty to see two kittens playing together, and they get so much enjoyment out of their games, that two may be preferred to one, but if a puppy playfellow is available, so much the better for the kitten.

The training of kittens to be clean in the house is, fortunately, not often a difficult task. All kittens, whether they have easy access to a garden or not, should have been first taught, in their earliest infancy, to use a box of earth, ashes, or peat-moss litter.

When they first begin to crawl in and out of the nest they should have a little pen made for them, with the nest box or basket at one end and the shallow box of earth at the other. A well-trained mother will do a good deal for them, and they have, if healthy, very clean instincts. But it is absolutely necessary that the earth, or whatever substance is used in the box, should be quite dry, and very frequently renewed. The kittens will not go near it if it is wet or dirty. Sawdust should not be used, as it gets on their paws and into their fur; if ashes are chosen, they must be finely screened. Nothing is better than powdered peat-moss litter, which is deodorant and very absorbent.

In catteries, and in town houses where the cats cannot get out readily, breeders always give them these boxes or shallow earthenware or tin or iron pans of earth, etc.; and when queens must be shut up it saves an infinitude of worry if they have been accustomed to them as kittens. When older, as when young, however, clean cats will never use pans in which the earth is not fresh, dry, and clean, so they must be frequently attended to.

NEUTERS.

The operation usually performed on male kittens is a most necessary one, if they are to be kept as pets. It should not be done too early, or they will not grow to the great size that is their chief beauty. Neuters make charming pets, as a rule, less independent than other cats, and very affectionate and docile. The operation, which is best done at from six to nine months old, is the affair of a moment, if performed by a

clever veterinary surgeon, and no other should be allowed to do it. No anaesthetic is actually required, though most surgeons prefer to use one, and the cat does not suffer, and need only remain with the veterinary surgeon for a day or two. The parallel operation, however, as performed upon the other sex, is far more severe, and does not obviate all the inconveniences it is designed to prevent. Only a very few practitioners claim to do it successfully, or advise it, and what little popularity it may have had among breeders is hardly justified by results, except in cases of hysteria, which is not uncommon in female cats. In these it may be very beneficial.

SHOWING KITTENS.

To show very young kittens is tempting misfortune, for as many bad colds as there are kits in the litter is the least return the Fates are likely to make, and no amount of prizes will compensate the cat lover who sees distemper introduced into the cattery on their home-coming. They may, of course, be sold at a show, though wise people who understand cats are chary of purchases straight out of a show, especially kittens, preferring to negotiate a little later on, when it is sure that the desired acquisition has not picked up distemper or anything else undesirable.

The show may be all that care can make it in the way of good sanitation, and there may not be draughts — though these usually abound — but who can protect baby kits against the dangers of the journey, and the, to them, harassing ordeal of a strange place in strange company? The true cat lover would like to see a final rule established altogether excluding kittens under five or six months from all shows. The public, of course, is of a different opinion, and the litter classes are always very popular.

Kittens of more mature age that are intended to be shown should have a little preliminary training as otherwise they may be frightened when they find themselves in a show-pen. These pens can be bought for a very small sum, from about eighteenpence each, and they are advertised in all the poultry papers. All that is necessary is to accustom the kitten to being in one, and this is easily done by putting it in for an hour or so round about dinner-time and feeding it there. Pleasant associations are thus engendered.

SHOWING CATS AND KITTENS.

Many novices have not the smallest idea how to set about showing a cat, therefore no apology is perhaps needed for directions that may seem to be a repetition of the obvious, to experienced exhibitors. The first thing to be done is to get a schedule. It will be sent, on application by postcard or note, by the secretary, whose address is always given in the advertisements of the show, and should be carefully read, both because show rules may vary to some extent, and because the cat or kitten to be entered may be eligible for some special prize. Besides this, registration with one of the Cat Clubs, of which there are several, may be necessary. The entry-form enclosed in the schedule is then to be filled up and sent in with the stated fees. After this nothing remains but to await the day, and meanwhile to get the exhibit into the best possible fettle. If the show is held in the summer, when almost all long-haired cats are out of coat, this condition in the exhibit is of less moment, as others will be as bad; but if it is a winter or spring show, an exhibit that unluckily happens to be out of coat will be much handicapped.

Neuters, with which other cats have often no chance of competing in the matter of coat and size, are always given classes of their own, and must not be entered except in their own stated section.

Very roomy, comfortable, and substantial boxes or baskets, well lined, warm, with easily fastened but secure strappings, should be used for show cats. The stewards who have charge of the un-packing and repacking at a show are generally careful, but they often have a very great deal to do, and in the rush a hamper of which the fastenings give trouble is apt to be neglected, and the inmate may escape, and perhaps be lost, or it may oven spend the time of the show in its basket, of course unnoticed by the judges, and worse still, unfed. Some exhibitors are most careless in this respect, perhaps expecting a busy show official to undo and refasten several yards of string with which they have laced together some old basket only fit to hold vegetables.

As a rule the schedule gives particulars of the way in which the exhibits will be fed, and if they are not to be dieted as the exhibitor desires, it is always best to put a card inside the lid of the package, on which the diet to be given is legibly inscribed, ‘This Cat to be fed on Meat only,’ for example. The food at shows is often very good, scraped or minced raw beef being very usual.

The disinfectants, however, which, of course, are to some extent absolutely necessary, are frequently overdone, and many exhibitors believe that illness after shows is often due to the cat’s or kitten’s being sickened with the tremendous volume of whatever antiseptic is in question. In this respect, as in that of feeding, is illustrated the very great advantage of an owner’s attending the show in person.

It is easy enough, if the pen seems to smell too strongly of disinfectant, to get it cleared out and wiped up, and to put in fresh hay or straw with a blanket or cushion if desired. Again, the cat exhibitor who has experience of shows generally takes some ready-made curtains, or a rug or shawl, with which to ward off draughts if the pen happens to be in a cold place.

At some shows there are rules regulating the amount of decoration that may be hung about the pens; at others, owners have free rein for their fancy, and make their exhibits perfect little bowers, more or less extravagantly draped with embroidered curtains and mottoes, and elaborately cushioned within. Occasionally there are classes for led cats, when it is rather a pretty sight to see a number of fine big neouters, more or less docile, going round a ring in collar and lead; but otherwise cats are always judged in their pens, and usually not in the presence of the public. Of course the judge may, and generally does, handle the exhibits, and takes them out on to a table, but only one by one, and in the presence of the stewards and officials only.

PREPARING EXHIBITS FOR SHOW.

Cats and kittens should always be thoroughly groomed, and sent or taken to a show in the best possible state of bloom and finish. White or light-coloured cats should be shown clean, and it is permissible to gain this end by rubbing fine flour, fuller’s earth, warm bran, or violet powder (starch powder) into their coats, provided it is thoroughly well brushed out again, and no particle remains that could be supposed to improve their whiteness or colour.

No kind of radical improvement, by plucking or cutting or pulling out hair, is allowed. Of course, the world being what it is, a certain amount of ‘faking’ by such means, and also by devices of colouring to improve existing colour or disguise faults, does pass unchallenged; but, on the other hand, there is always the risk of disqualification, and if the judge either does not, or dare not, penalise any offender, the other exhibitors are not likely to fail in detecting any such treatment, and in the end honesty is decidedly the best policy — apart from the moral considerations which should deter the exhibitor from illegal improvements.

Unfortunately, trials of temper to the perfectly straightforward exhibitor are by no means lacking at cat shows, and both judges and exhibitors frequently have entirely legitimate grievances, but in the end good temper and uprightness are certain to win recognition, besides comforting the conscience with self-approval. A very cross cat — there are, unluckily, a few such — is not a very satisfactory show possession. However good the specimen may be, it is hardly in human nature for the judge or visitor who has been soundly clawed when he put his hand in or near the pen to remain unresentful. Cat scratches are the worst of all minor wounds to heal, and the show-pen always seems to exacerbate whatever uncertainty of temper an animal may possess. Queens and neuters are very rarely savage, but stud cats occasionally suffer from pains in their tempers, and the novice will do well to remember this when going round a show.

A good brushing and combing, with, for short hairs, a finishing polish with a chamois leather, is desirable just before judging, as cats’ coats are not at their best after a journey and being shut up in a box or basket.

As a rule a cat is improved by being shown fat, and therefore a little extra meat may be given for a week or two beforehand. For bad doers, or cats not quite up to their best form for any cause, a little cream (not milk) daily is a good conditioner. It must, however, be really pure, and quite free from preservatives, such as formalin, borax, etc., or thickening matter, such as glucose, starch, and corn-flour.

To ensure purity, and yet get good double cream, the best plan in these days of uncertainty as to adulteration is to set a pan of milk — a quart in a very shallow dish will do - and let it remain for twenty-four hours, then skimming the cream from the top. If it only sets for twelve hours we get thinner cream: what rises in the twenty-four hours is good double cream, always supposing the milk itself to be pure and of good quality. A kitten may have two tablespoonfuls and a cat double that quantity in the day, given midway between the meat meals.

A new-laid egg is another good conditioner, but some cats will not take it. It should be slightly beaten up, but not mixed with milk or anything else. Luckily not even Chicago has yet solved the problem of egg-adulteration, and freshness or its converse is readily perceptible. Some writers advocate aperient medicines for kittens and cats on their return from shows, but if such drastic and irritating drugs as castor oil are given, any lurking intestinal mischief is only likely to be stirred into activity, whereas gentle exercise, warmth, and the comfort of being at home might otherwise have soothed it away. If constipation is suspected, a dose of olive oil, warmed, may be given.

Olive oil, provided it is pure — and it should always be got from a good chemist, never from a grocer, when required for medicinal purposes — is a splendid aperient, the best possible thing to give animals. It entirely removes any obstruction, mechanical or otherwise, causes not the slightest pain, is nourishing and most healing in its effect on the intestine, does not, like castor oil, clear away all the natural and healthful mucus coating of the intestinal membrane, thus setting up a worse subsequent condition of costiveness than that it was given to cure, and does not cause sickness or nausea. It is not nasty and many cats will take it quite readily if a couple of teaspoonfuls are mixed with a little minced boiled liver, or poured over a boned sardine, or herring roe.

Castor oil, oh the contrary, is a veritable poison in its irritating quality, and is certainly accountable for many evils worse than those it is supposed to cure, besides which it is horribly nauseous and very troublesome to administer. Like Epsom salts, another virulent but favourite drug with many, it ought to be banished with ignominy from the animals’ pharmacopoeia. The isolation of exhibits on their return from a show is a very wise practice. It is always possible that they may have brought distemper back with them, and until we are quite sure that they have not done so it is most desirable to segregate them from any other cats or kittens in the house. Their travelling baskets, or boxes, too, should be kept apart until it is certain that no contagion exists.

COMMON AILMENTS OF CATS.

For the cat owner to attempt, without skilled veterinary advice, the treatment of the more serious diseases, such as pneumonia, distemper in either its catarrhal or enteric forms, or gastritis, to which cats are subject, is only working in the dark. No amount of advice on paper is of any use where the treatment depends, as it must in these severe illnesses, entirely on the special symptoms, which vary in each case. There are only certain general rules which can be laid down. For example, when a cat seems to be unnaturally heavy and sleepy, indifferent to food, and tucking itself up with its head down and remaining motionless, though apparently contented and in no pain, for hours at a stretch, a competent veterinary surgeon should be asked to ascertain whether it is sickening for the enteric form of distemper, which resembles typhoid fever in human beings.

Or if a cold, more or less severe, which has been treated in the beginning by warmth and kitchen physic — really all that a conscientious adviser can recommend the amateur unlearned in medicine to do for ailments that it is so difficult to diagnose correctly as the chest and lung troubles of cats — seems to be getting worse about the end of the second day, a veterinary surgeon should at once see the patient. Any panting, with the mouth open, is a serious sign intimating pneumonia; and a desire to lie in draughts, close to the door or window, is always a token that the patient is quite ill enough to require skilled medical aid.

Young kittens that take distemper or any really severe illness are seldom able to get over it enough to be really strong and healthy in afterlife, and though it may sound heartless, it is never worth while to go through the anxiety and worry of nursing kittens through a severe illness, in order to preserve lives that will never be of much value to their sickly and stunted possessors. The survival of the unfit is no benefit — far from it — to the race, even on sentimental grounds.

COLDS.

A cat showing any signs of cold in the head and throat, as sneezing or gulping, should at once be put by itself in a sunny room, not too hot, but comfortably warm. It will be all the better if the room is not very large, so long as it is not draughty, as inhalations often do great good, but it is never worth while to struggle with a feline patient if it can possibly be avoided. More harm would probably be done by forcibly holding the cat’s head over steam than good by the inhaling, for we should then find puss resisting, and resentful on every subsequent occasion when it might be really necessary to give medicine or otherwise constrain her. Tact and gentleness are more needed in conjunction with cats than with any other sick animals, which is saying a great deal.

The best inhalation for a cold is one of oil of eucalyptus - and pinol. This latter is a somewhat expensive but very valuable extract, exceedingly soothing to the bronchial tubes, and most effective in combination with eucalyptus oil. A bronchitis kettle, or, for the matter of that, a little sixpenny tin kettle on a small oil stove, should be kept at steaming point, and a few drops of the two oils should be added now and then. The diet should be good — feed a cold — and anything the cat has a special liking for should be given. No going out must be allowed, and here comes in the advantage to a cat of having been trained when a kitten to use a box of earth.

Colds, once firmly established, must run their course, which cannot be greatly hastened. The only drug treatment desirable or permissible on unqualified prescription is the administration of a little quinine in the incipient stage, when a quarter to half a grain of sulphate of quinine, in pill form, every five hours, may cut the ailment short.

Again, after recovery from a cold there may be obstinate relaxation of the bronchial mucous membrane; shown by snuffling and persistent discharge, though the patient seems otherwise well. In these cases a course of iron often works wonders, as it has a very beneficial influence in toning up the mucous membrane. The saccharated carbonate is in most cases much the best form in which to administer iron to animals. It is a beautiful preparation in fine powder, quite non-constipating and tasteless, except for a slight sweetness, and is nearly, always readily taken on meat. The dose for a kitten is one grain, and for a cat about three grains, twice a day.

It is, of course, quite useless to give any form of iron spasmodically, or for only a short time. The shortest course likely to do good; is three weeks, and a course of at least six weeks is generally desirable.

SKIN TROUBLES.

Iron is a most valuable drug in the treatment not only of degenerated mucous membranes, but of all skin troubles arising from anaemia. Anaemia is, practically speaking, an impoverished or degraded state of the blood, which is deficient in red corpuscles. All cats and kittens fed too much on farinaceous food, and denied animal food, which contains certain mineral salts and an earthy element necessary to healthy blood, are more or less anaemic by force of circumstances. Their blood would normally take up these desired elements through the agency of numberless minute ducts in the intestinal canal walls. Failing to do so, they become anaemic, and in this condition the skin is not properly, nourished, and soon begins to deteriorate in health.

As a first step in the process of skin degradation we get a simple falling out of hair from weakness of the follicles, and a dry, scaly or scurfy, ill-nourished appearance of the skin. When in this state, if a cat or kitten picks up any ova of worms, either round, or, much more commonly, tapeworms, these horrible parasites find a most congenial lodging, and increase and multiply rarely, thus helping to increase the malnutrition and anaemia by their demands on the system. Advisers, quite ignorant of cause and effect, will now certainly be found in plenty, eager to assure the novice that the worms are the beginning and origin of all the patient’s evils, whereas, if the host had been healthy, the parasites could not have increased sufficiently to be anything more than an inconvenience at the worst.

Both in this initial stage and in more advanced states of skin trouble a course of iron and a strict but very liberal regimen of raw meat is the invariable prescription, and the only one likely to be successful. Great patience is always necessary in cats’ skin trouble — firstly, because their skins do not betray the constitutional trouble so soon as those of dogs, and secondly, because only very mild outward applications are possible in their case. We are debarred from the use of any carbolic or phenyl or tar derivatives, because all these are poison to cats, and so the sharpest weapons against most skin diseases per se are denied to us.

After the commencing stage of skin difficulty already described, the trouble may develop into dry or weeping eczema, or mange. There are two forms of mange, but luckily the worse of the two, follicular mange, is very uncommon in cats. Sarcoptic mange is rather frequently seen on the wretched strays and starved castaways of towns, and an otherwise well-cared-for cat that has been mistakenly fed and denied meat may very easily, when in the early stages of anaemia, pick up this form of mange from some undesirable acquaintance.

MANGE.

Mange is a dreadful word, but the disease is really easier to cure than many eczemas. The cat must be entirely covered with a dressing of warm olive oil and flowers of sulphur, mixed to a thickish cream. After this a coat of thin white Saxony flannel, made to fit closely round the body and over the chest — a bag drawn up round the neck, and with four holes for the legs, is perhaps the best rough-and-ready way of describing it — should be put on, and the patient must be strictly isolated in a warm room. The dressing will probably need repeating several times, at two days’ interval. When the patient has entirely ceased to scratch, and a new growth of fine hair is seen appearing — the coat falls off entirely in mange, so far as the disease extends — the cure is generally complete. As mange may produce some skin irritation in the hands of people who are susceptible — those who have a rheumatic diathesis especially — an old pair of gloves should be worn when handling or dressing a cat with the complaint.

ECZEMA.

The difference between mange and eczema is generally perceptible even to the inexperienced, as in the former disease the hair comes out in tufts, and very rapidly leaves comparatively large spaces bare, whereas in eczema one or more small bare places appear, and if neglected increase in number and slowly in size, and the hair does not fall in tufts, but disappears by degrees. Also the irritation of mange — which usually begins about the head — is much more severe, and there is a bad and peculiar smell that is unmistakable. Mange is always a cause of violent irritation, while in some forms of eczema there is little or no scratching.

When any cat starts a skin complaint and there is no competent veterinary surgeon at hand, the best thing to do is to pluck a small tuft of fur from the affected part and send it by post to a good veterinary surgeon for microscopic examination, as it is always important to know whether or not the disease is contagious. The amateur cannot be expected to be able to diagnose at sight where most experienced authorities would prefer to use the microscope before pronouncing a decided opinion, unless an obvious mange or ringworm be the trouble.

The several forms of eczema afflicting cats are roughly divisible into weeping or wet and dry or scaly eczema. The latter is much the most common.

A liberal diet of raw meat, as many freshly killed birds and mice as possible, no milk, no fish, no vegetables, and above all no farinaceous foods, together with a persevering course of iron, as before described, constitute the treatment necessary, whether the bare places that appear are sore and wet, sore and dry, or merely bare without any lesion of the skin. A sulphur lotion should be freely used, the following being a good prescription: Flowers of sulphur 2 ounces, bicarbonate of soda 2 drachms, boric acid 2 drachms, new milk to half a pint. Shake, well before using, and apply with a bit of sponge. Water should not, as a rule, be employed in making up any lotion intended for use on eczema patients.

When after a fair trial of several days’ steady use this lotion — which can never do any harm — does not seem to be conquering the trouble, break off with it, and for a few days use a lotion of pure methylated spirit, followed by a dusting of iodoform or ichthyol powder if the patient cannot lick the parts affected. If it can, use fuller’s-earth or pure starch powder. If the head is the seat of skin disease the front paws should always be hobbled, or tied loosely together, with a few twisted strands of Berlin wool or something equally soft, so that the patient cannot wash its head and face in the way customary with cats. By so doing it would infect the rest of its body.

In some cases where the skin is very scurfy and branny on the bare parts, and these are out of reach of the cat’s tongue, zinc ointment is a good application; but as a rule any greasy preparation like ointment should be, if possible, avoided, because the grease is apt temporarily to increase the irritation, and also the cat at once feels that a smeary application has been made, of which it is most intolerant, and which worries it terribly, and is sure to try all it can to get it off. Zinc acts as an emotic if swallowed in sufficient quantity, and no ointments, not even simple sulphur ointment, are ‘halesome faring.’