AN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY MISCELLANY OF CATS

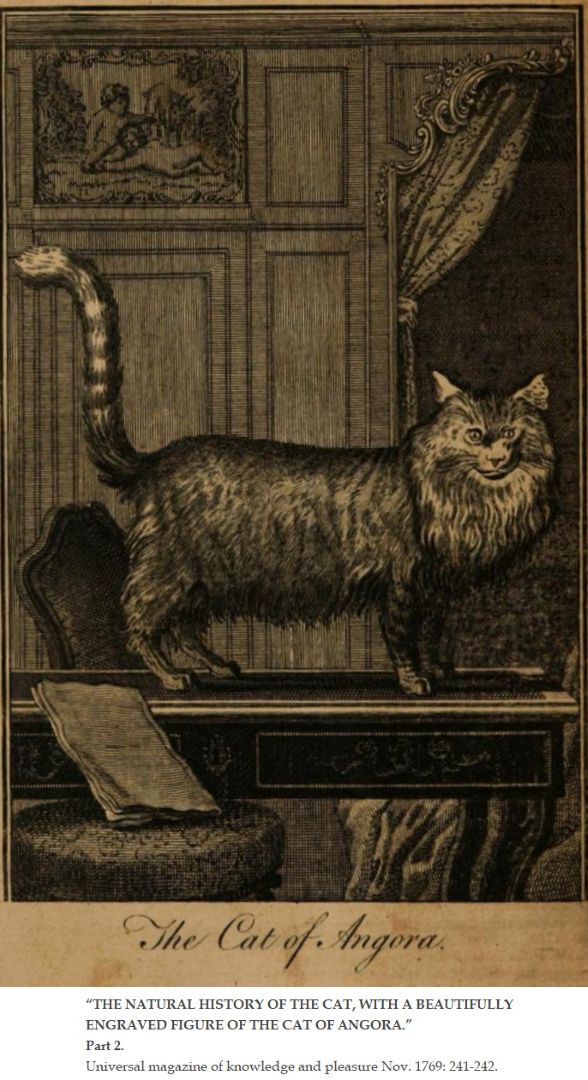

"THE NATURAL HISTORY OF THE CAT, WITH A BEAUTIFULLY ENGRAVED FIGURE OF THE CAT OF ANGORA."

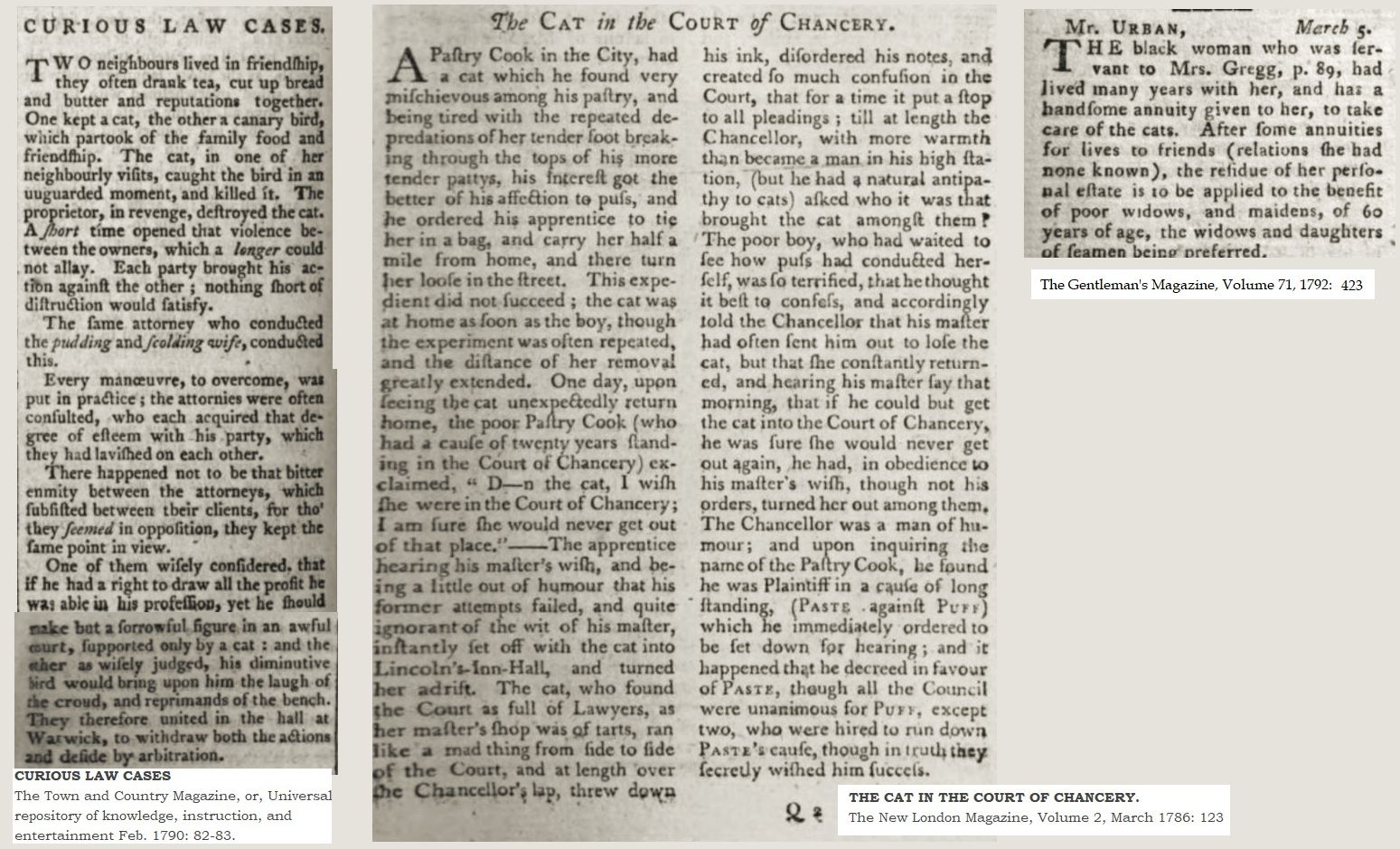

Universal magazine of knowledge and pleasure Nov. 1769: 185-188 and 241-242.

This anonymously published article in two parts, the second part having an engraving of an Angora cat was a translated section of Buffon's Natural History. It is different from the better-known William Smellie translation of 1781.

We have hitherto given an Account of such Parts of Natural History, as seemed curious ore useful; and, as our Readers seem desirous of our continuing such subjects, which indeed are both instructive and amusing, we shall endeavour to gratify them in that Particular, and occasionally illustrate with well-engraved Copper-plates whatever we give the History of. – Here we present them with the Natural History of the CAT, and a finely engrave Figure of that Animal in its wild state.

The Cat is a faithless domestic, kept only through necessity, for the purpose of being opposed to another domestic enemy still more troublesome, which cannot be otherwise expelled: For we here make no account of those, who, fond of most sorts of beast, rear them only for their amusement; the one is an use, the other an abuse; and though these animals, especially when young, have many pretty ways and tricks, they have all, at the same time, an inbred malice, a false nature, a perverse disposition, increased by age, and marked only be education. Tho' well trained up and familiarised, they turn out, notwithstanding, arrant thieves, yet supple, fawning, and flattering as knaves; they have the same address, the same cunning and stratagems, the same inclination for doing mischief, the same propensity for petty larceny: Like them they know how to disguise their intended progress, dissemble their design, spy out their opportunity, wait, chuse, seize the instant of doing business, and then avoid punishment by running away and keeping at a distance till they are called. They easily contract the habits of society, but never the manners. They retain only the appearance of attachment: This may be observable from their oblique motions, their equivocal eyes; they never look the beloved person in the face; whether through diffidence or a false heart, they go a round-about way in their approaches, to seek caresses, of which they are no otherwise sensible, than by the pleasure they receive from them. Very different from that faithful animal, whose sensations are all directed to the person of his master, the cat seems to have no feeling but for himself, to love only upon condition, to keep up a correspondence only for abusing it; so that, by this natural disposition, he is less incompatible with man, than with the dog, in whom every particular is sincere.

The form of the body and the constitution are of a piece with the natural disposition. The cat is pretty, light, nimble, dextrous, cleanly, and voluptuous. He loves his ease, and seeks the softest furniture for repose, or diverting himself with this sports; he is also very amorous, and, what is rare in animals, the female seems to be hotter than the male; she invites him, seeks after him, calls him, and expresses by earnest cries her passionate desires, or rather the excess of her wants; and, when the male shuns of slights her, she pursues, bites, and forces him to a compliance, though the approaches are always accompanied with a lively sense of pain. Her heat lasts nine or ten days, and is regulated by stated time, usually twice a year, in the spring and autumn, and sometimes three and even four times. Cats go with young fifty-five or fifty-six days; they do not produce so great a number as the females of dogs, the common litters consisting of not above four, five, or six. The males being subject to devour the young, the females hide themselves to bring forth, and when they fear a discovery, or taking away of their kittens, they transport them into holes and other unknown or inaccessible places; and, having there suckled them for some weeks, they bring them mice, small birds, and accustom them betimes to eat flesh; but, by a strange behaviour hard to be comprehended, these same mothers, so careful and so tender, become sometimes cruel, unnatural, and devour also their young that were so dear to them.

The young cats are wanton, sprightly, and full of play, and would be very proper for amusing children, if the scratching of their claws were not to be apprehended; but their sportive humour for scratching, though always agreeable and light, is never innocent, and soon is converted into habitual malice; and, as they cannot exercise these talents with advantage but on small animals, they lie on the catch near a cage; they watch birds, mice, rats, and become themselves, and without being trained to it, more expert at hunting than the best taught dogs. Their nature, averse from all constraint, makes them incapable of a regular education. It is, however, related by Dapper, in his description of the Isles and Archipelago, that the Greek monks of the Isle of Cyprus had trained up cats for hunting, taking, and killing the serpents with which that isle was infested; but it was rather from the general propensity they have for destroying, than through obedience that they hunted; for it is their humour to spy out, watch, attack, and destroy indiscriminately all weak animals, as birds, young rabbits, leverets, mice, shrews, bats, moles, toads, frogs, lizards, and serpents. They have no docility; they also want sagacity and the fineness of smell, two eminent qualities in the dog; and therefore they do not pursue the animals which they do not see; they do not hunt but wait for them; they attack by surprise, and, having played with them a long time, they kill them without any necessity, when even they are well fed, and have no occasion for their prey to satisfy their appetite.

The most immediate physical cause of this inclination they have for watching and surprising other animals, proceeds from the advantage the particular conformation of their eyes gives them. The pupil in man, as in most other animals, is capable of a certain degree of contraction and dilatation; it becomes larger in the absence of light, and contracts when too vivid. In the eye of the cat and night birds, this contraction and dilatation are so considerable, that the pupil, which in darkness is round and large, becomes, in a bright ay, long and narrow as a line, and hence these animals see better in the night than day, as may be observable in owls; for the form of the pupil is always round when it is under no constraint. There is therefore a continual contraction in the eye of the cat in the day-time, and it is not as it were but by efforts that he sees in a strong light; whereas, in the evening twilight, the pupil resuming its natural state, he sees perfectly, and avails himself of this advantage to reconnoitre, attack, and surprise other animals.

It cannot be said that cats, though inhabitants of our houses, are intirely domestic animals; those that are the best-tamed are not therefore the more in a state of subjection: Nay, it may be said that they are intirely free, that they do what they please, and no consideration is able to prevail on them to remain one instant in a place hey have a mind to get away from. Besides, most of them are half-wild, have little or no knowledge of their masters, and frequent only sometimes the kitchen and pantry, when pressed by hunger. Though more of them are reared than dogs, their number is not so discernible, and therefore they are less fond of persons than houses. When they are transported to pretty considerable distances, as a few miles off, they return of themselves to their granary, and it is probably, because they know all the retreats in it for mice, all the outlets, all the avenues and passages; and because the trouble of the journey is less than that they must take to acquire the same facilities in a new country. They dread water, cold, and ill smells; they love to bask in the sun, to lie in the snuggest and warmest places, in chimney corners and ovens. They love also perfumes, and suffer themselves to be taken up and fondled by those that are scented with them. The smell of the plant called cat's-herb, or valerian, affects them so powerfully and deliciously, that they appear quite transported with pleasure. Those who chuse to give a place to this plant in their gardens, are obliged to inclose or rail it in; for the cats smell it at a distance, run to rub themselves against it, and pass and repass over it so often, that they soon destroy it.

In fifteen or eighteen months time these animals come into their full growth; they are also in a state of engendering before they are a year old, and may copulate during their whole life, which seldom extends beyond nine or ten years: They are, notwithstanding, very hardy, full of life and spirits, and have a greater supple play of the nerves than other animals that live longer.

Cats cannot chew but slowly and with difficulty; their teeth are so short and so ill-set, that they only serve for tearing and not grinding their aliments; they give therefor the preference to the tenderest meats; they love fish and eat it dressed or raw; they drink frequently; their sleep is light, and they sleep less than they pretend to sleep; they step so lightly, almost always in silence and without making any noise; and they hide and keep aloof to o their occasions, which they cover with earth. Being neat and cleanly, and their coat is always dry, sleek, and glossy, their hair is easily electrified, and sparks are easily seen to pass out of it when rubbed with the hand in a dark place: Their eyes glisten also in darkness, nearly as diamonds, which reflect, in the night, the light, they had, as it were, imbibed the day.

The wild cat produces with the tame, and both consequently constitute but once and the same species. It is no rare thing to see male and female cats quit houses in the time of heat to go into the woods in quest of wild cats, and afterwards return to their respective habitations. On this account it is, that some of our domestic cats intirely resemble the wild; the most real difference is internally; the tame cat's intestines are usually longer than those of the wild; yet the wild cat is stronger and larger than the tame; he has always black lips and stiffer ears, the tail thicker, and the colours constant. In the European climates but one species of wild cat is known, and it appears, by the testimony of travellers, that this species is likewise found in almost all other climates without being subject to great varieties. There were cats on the continent of the New World before it was discovered; a hunter brought one he had taken in the woods to Christopher Columbus; this cat was of the common size, his hair was of a grey-brown, the tail very long and strong. There were also wild cats in Peru, though none tame could be met with; in Canada, in the country of the Illinois, &c. in several parts of Africa, as in Guinea, the Gold-coast, at Madagascar, where the natives of the country had likewise tame cats; at the Cape of Good Hope, where Kolben says there are wild cats of a blue colour, tho' few in number: Those blue cats, or rather of a slate colour, are again met with in Asia. ‘There are in Persia,' says Pietro della Valle in the account of his travels, ‘a sort of cats that are properly of the province of Chorazan; their size and form is as that of the common cat; their beauty consists in their colour and hair, which is grey without the least spot, of the same colour throughout the body, except a little darker on the back and head, and clearer on the breast and belly, which runs sometimes to whiteness, with that agreeable blending of the clair-obscure, as Painters express it which intermingled, produces a wonderful effect: Their hair is moreover thin, fine, glossy, soft and delicate as silk, and so long, that, though it is not rough, but lies flat, it buckles in some places, and particularly under the throat. These cats are, among their species, as the barbets among dogs: The most beautiful part of their body is the tail, which is very long, and quite covered with long hairs of five or six fingers breadth; they extend and turn it over their back as squirrels, the tip upwards in form of plume of feathers, they are very tame. The Portuguese brought some of them from Persian to the Indies.' Pietro della Valle adds, ‘ that he had four couple which he thought of taking with him into Italy.' It appears by this description, that these Persian cats resemble those in colour that are called Carthusian cats, and that in other respects they perfectly resemble those we call cats of Angora. It is therefore probable that the cats of Chorazan in Persia, the cat of Angora in Syria, and the Carthusian cat are of the same breed, whose beauty proceeds from the peculiar influence of the Syrian climate, and the cats of Spain, which are red, white, and black, and whose hair is also very soft and glossy, are indebted for this beauty to the influence of the climate of Spain. It may be said in general, that, of all the climates of the habitable earth, those of Spain and Syria are the most favourable to those beautiful varieties of nature. Sheep, goats, dogs, cats, rabbits, &c. have in Spain and Syria the finest wool, the beautifullest and longest hair, and the most agreeable and variegated colours; it seems that this climate renders nature mild, and embellishes the form of all animals: The wild cat has harsh colours, and the hair somewhat rough, as most wild animals: Because tame, the hair grows mellow, and the colours have a greater variety; and, in the favourable climate of Chorazan and Syria, the hair has grown longer, finer, fuller, and the colours have been more uniformly softened: The black and red are become of a clear brown, and the grey-brown an ash colour grey; and, comparing a wild with the Carthusian cat, it may be perceived that they differ only in fact by a shadowed degradation of colours; and it may likewise be easily conceived that (as these animals have more or less white under the belly and at the sides) in order to have cats quite white and with long hairs, such as those we properly call cats of Angora, we need only chuse in this tame breed those that have most white on the sides and under the belly, and by their union cats intirely white might be produced, as has been done for procuring white rabbits, white dogs, white goats, white deer, &c. In the Spanish cat, which is but another variety of the wild, the colours, instead of being weakened by uniform shadowings as the Syrian cat, are as it were, exalted in the climate of Spain, and become more lively and distinct, the russet being almost red, the brown black, and the grey white. These cats, transported to the American islands have retained their beautiful colours, and have not degenerated. ‘There are at the Antilles, says Father Tertre, a great number of cats, which probably were brought there by the Spaniards; most of them are marked with red, white, and black. Several of the French, after eating the flesh, export the skins to France for sale. These cats, when we were first at Guadaloupe, were so accustomed to feed on partridge, pigeons, snipe, and other birds, that they had no manner of mind to look after rats; but, the game being at length much diminished, they broke their truce with the rats, and now wage war in earnest against them.' In general, cats are not, as dogs, subject to alter and degenerate when transported into warm climates. European cats, says Bosman, transported into Guinea, are not subject to change as dogs, for they retain the same figure. They are in fact more consistent in their nature, and as their domesticity is neither so entire, nor so universal, nr perhaps so ancient as that of the dog, it is not surprising that they have less varied. Our domestic cats, though different from one another in colour, do not form distinct and separate breeds. The only climates of Spain and Syria, or Chorazan, have produced constant varieties, which are perpetuated: We may herewith add the climate of the province of Pe-chi-ly in China, where there are cats with long hair and hanging ears. The Chinese ladies are very fond of them, and these cats, of which we have not a more ample description, are undoubtedly still more remote than others with erect ears, from the breed of the wild cat, which, notwithstanding, is the original and primitive flock of all cats.

The Natural History of the CAT, finished from Page 188, of our last, with a beautifully engraved FIGURE of the CAT of Angora.

Description of the CAT of Angora, &c.

SUCH of those cats as are met with in Europe have been brought from Angora in Syria: They seem much larger than other domestic cats, and even than the wild cat, their hair being much longer. They are for the most part white; but there are some which are of a fallow colour, and striped with brown. The cat, represented in the annexed plate, was fallow. His legs were so short, and his hair so long, that the hair of his belly reached down to the ground; yest his longest hair formed a sort of ruff on the sides of the head and neck, and under the lower jaw-bone, and fore part of the neck, it was four inches long; but the hair of his lips, nose, forehead, fore and hind feet, was short as in other cats. Under each of his eyes were two arches of a reddish fallow colour, and the tip of the nose was of the same colour. The fore legs and tail were incircled with rings of a deep fallow colour; the head, back, sides of the body, flanks and legs were also of a deep fallow colour, which was lighter on the rest of the body.

This cat has a round head, the ears erect, the forehead well proportioned, the eyes large and little distant from one another, the nose with a spring or bearing out, the snout short, the mouth small, and the chin appearing but little, The assemblage of those features give it an air of softness, which proceeds particularly from the eyes being large, and the snout very short. The proximity of the eyes to each other, and to the mouth and nostrils, with their forward position, seem to express an air of fineness, which is still heightened by the form of the forehead and entire head, and the position of the ears. This mild and fine face changes in a very remarkable manner when the cat is agitated by some violent passion; he opens his mouth and his eyes flash with fire; he turns about his ears and lets them fall; he shews his teeth; his hairs stand on end, and he assumes a furious look, accompanied with quick and vigorous motions of the body, and some lamentable and frightful cries. His tufted hair covers the figure of his body, so as to keep the proportions from being distinguished; all that is seen is, that his body is long and legs very short, but his motions indicate the suppleness and agility of his limbs.

Almost all animals have on each side of the snout some long, straight, and stiff hairs like hog's bristles. These hairs are very apparent in the cat, so assembled and situate as to receive commonly the name of whiskers: There are also others on the side of the forehead over the fore angle of the eye, and on each side of the head beyond the corners of the mouth; they are for the most part white, and the longest are about three inches. There is in the fold of the cat's fore leg a tubercule of a conic figure, which seems formed as that of the dog, by the friction of the third bone of the first row of the carpus.

It will not be amiss to observe in regard to some domestic cats, which, like wild cats, have black lips, and the soles of their feet black, that they generally are the best mousers, and most diligent in attacking their prey of any kind. These have black bands of stripes on the body, and rings of the same colour on the tail and legs, as wild cats, but they have less of the fallow colour, and grey seems to be the predominant colour of their hair: There is reason, however, to believe that they have less degenerated from the original race than others, because they have black lips and the soles of the feet black, and it is therefore they are distinguished from other domestic cats; but their hair is shorter than that of the wild cat, and consequently the head, body, and especially the tail, appear less large.

Cats with red lips are different from the foregoing, and are of one colour, white or black, or of a colour mixed with white, grey, brown, black, and fallow. There are often several of those colours on each hair, and they are also distributed by spots, waves, stripes, and so various that there are not two cats on which the mixture is alike.

The bright and deep red colour is the principal, and perhaps the only character that distinguishes the cats of the Spanish breed. These, however, are not all indiscriminately of that colour, some of the females having white and black spots, distributed and mixed irregularly with the red spots, and differently in each individual. It is pretended that none of the male have three colours, having only white of black with the red; so that, when one has a mind to have a fine Spanish cat, a female is generally chosen, because she has a colour more than the males.

The domestic cats of an ash-colour are called by the French Carthusian cats. Some pretend that these cats are blue, but they have not the least tint of that colour. Their hair is of an ash-grey in the greatest part of its length and at the point, and there is a blackish brown under the extremity. The hairs being thick and lying upon one another, the grey colour of the point and the brown underneath are not seen. This mixture of grey and brown is not distinguished but when closely inspected; they seem at a distance as tinged with a glossy grey-brown, and the grey or brown is more or less apparent in different points of view. About the eyes and mouth, the chest and lower part of the legs, there is more grey than brown; the ears are unfurnished of hair, at least on the edges; and of a blackish colour, as are the lips and soles of the feet. These cats likewise are more or less grey at different ages; some are remarkable for a black stripe on the back, and rings of the same colour on the legs, yet very lightly marked.

The cat, being but half tame, forms a shadowing, or rather stands in a medium between domestic and wild animals; for we should not place in the number or rank of domestic any of our troublesome neighbours, such as mice, rats, moles, which though inhabitants of our houses or gardens, are not therefore less free and wild, because, instead of being attached and subject to man, they fly from him, and in their obscure retreats, retain their manners, habits, and liberty quite intire.

Education, shelter, care, and the hand of man, have a great influence over the natural disposition, manners, and even the form of animals. These causes, acting conjointly with the influence of climate, modify, alter, and change the species, so as to be different from what they were originally, and render also the individuals so different among themselves, at the same time and in the same species, that we might have reason to regard them as different animals, if they did not retain the faculty of producing together fruitful individuals, which constitutes the essential and only character of the species. The different races of domestic animals follow in different climates the same order nearly of the human race: As mankind, they are stronger, larger, and more courageous in cold countries; more civilised, more gentle in the temperate climates; more timid, more feeble, and more ugly in too hot climates. It is likewise in temperate climates, and among the people that are best policed, that the greatest diversity is found, the greatest mixture, and the greatest variety in each species; and what is not less worthy of observation is, that there are in animals several evident signs of the long existence of their slavery: Hanging ears, various colours, long and fine hairs, are so many effects produced by time, or rather by the long duration of their domesticity. Most animals that are free and wild have erect ears; the wild boar has them erect and stiff, the tame hog inclined and half hanging. Among the Laplanders, the savages of America, the Hottentots, the negroes, and other unpoliced people, all the dogs have erect ears; whereas in Spain, France, England, Turkey, Persia, China, and all civilised countries, the far greater number have them soft and hanging. Domestic cats have not such stiff ears as the wild, and at China, which is an empire very anciently policed, and where the climate is very mild, domestic cats may be seen with hanging ears. It is therefore that the goat of Angora, which has hanging ears, ought to be considered among the goats as that which is most removed from the state of nature: The so general and signal influence of the climate of Syria, joined to the domesticity of these animals among a people very anciently policed, must have produced in time that variety, which could not be maintained in another climate. The goats of Angora reared in Europe have not such long nor such hanging ears as in Syria, and would probably resume the ears and hair of the European goats after a certain number of generations.

"AN ACCOUNT OF A CAT, THAT LIVED 25 MONTHS WITHOUT DRINKING – From the History of the Royal Academy of Sciences at Paris, for the Year 1753."

Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure Feb. 1759: 62-63.

M. l'Abbe de Fontenu, of the Royal Academy of Inscriptions and Belles Lettres, at Paris, to whom the Academy is indebted for several curious observations, was pleased to communicate to it in 1753 a very singular one. Having remarked how cats often habituate themselves, and oftener than one would wish, to dry warrens, where they certainly cannot find drink but very seldom, he fancied that these animals could do for a very long time without drinking. To see whether his notion was well grounded, he made an experiment on a very large and fat castrated cat he had at his disposal. He began by retrenching by little and little his drink, and at last debarred him of it entirely, yet fed him as usual with boiled meat. The cat had not drank for seven months, when this observation was communicated to the Academy, and has since passed nineteen without drinking. The animal was not less well in health, nor less fat; it only seemed that it eat less than before, probably because digestion was somewhat slower. The excrements were more firm and dry, which were not evacuated but every second day, though urine came forth six or seven times during the same time. The cat appeared to have an ardent desire to drink, and used his best endeavours to testify the same to M. Fontenu, especially when he saw a pot of water in his hand. He licked greedily the mug, the glass, iron, in short, every thing that could procure for his tongue the sensation of coolness; but it does not appear in the least, that his health suffered any alteration by so severe and so long a want of all sorts of drink. It may be inferred from hence, that cats may support thirst for a considerable time, without risk of madness, or other fatal accident. According to M. de Fontenu's remark, these animals are not perhaps the only that enjoy this faculty, and this observation might lead perhaps to more important objects.

"A SAFE AND CERTAIN CURE FOR THE BITE OF A MAD DOG OR CAT."

Anon. The Grand Magazine of Magazines, or a Public Register of Literature and Amusement, Nov. 1750: 331.

Published in a magazine for the general public, rather than in a text-book, this explains how to deal with a common eighteenth century hazard. Mad dogs or cats were believed to be diseased; even if they didn't have hydrophobia their bites could cause infection so it was important to know how to properly deal with such incidents. It was advised that a surgeon should carry out the procedure.

When you are bitten by a mad dog or cat, let a surgeon cut out the flesh the whole length of the bite, and if there is no vein in the way, let him cut it cross-wise in form of a star, that the blood may discharge itself freely; as soon as it is cut, let it be well washed with spirits of turpentine, or vinegar and salt mixed, if the former is not readily to be come at; while you are washing the part, be sure to squeeze the blood out as much as you can; afterwards put on a drawing plaister, and let it be dressed twice a day, rembring to wash it thoroughly before you put on a fresh plaister; after three days all danger will be removed, and dressing once a day will serve.

Oil of turpentine and bees-wax mixed together over a slow fire till they are of the consistence of salve make a very proper plaister.

THE MOST HUMBLE PETITION OF THE CATS OF THIS KINGDOM TO THE LEGISLATIVE BODY

Grimalkin, Norton (pen-name) in The Oxford magazine, or, Universal Museum Jun. 1770: 274-276.

A satirical piece written from the perspective of a cat responding to a new law which meant that the killing of a dog, but not of a cat, was a criminal offence.

The most humble Petition of the Cats of this Kingdom to the Legislative Body,

Humbly Sheweth,

That the above petitioners have, for time immemorial, laboured under grievances almost innumerable, some of which are too melancholy here to relate; but being now apprehensive that our grievances will become more insupportable, from the protection the legislative power, has of their infinite goodness and wisdom, lately confirmed to our fellow-brutes the dogs; the numerous disasters our species constantly suffer, and the apprehension of still greater danger to ourselves, from the late dog-law, has reduced us to the necessity of addressing that truly laudable power to take our sundry calamities into their wise consideration; humbly hoping, their boundless tenderness for domestic brutes, will promote a similar protection for us the ancient and most faithful society of English cats: particularly as the dog-act has rendered our lives and situation more dangerous than heretofore; for consequently, since the killing of a dog is legally pronounced criminal, it will in some measure enable them to make their natural, barbarous, and unprovoked attacks upon us with impunity; as neither the masters of the families we are engaged in. nor their servants, nor any other of our human friends, will venture to rescue us with their usual spirit, from these daring and cruel enemies; lest an unfortunate sling or stroke, should occasion the death of one of these licensed invaders; which would consequently subject our friends to the late law in such cafes provided. A law so admirably calculated, that both the admirer and the enemy of that animal must pay a strict regard to it; as an imprudent cherishing of the admired dog of your neighbour, or a rash chastisement given to an offending one, may be attended with danger. This law, according to our catish conceptions, was not calculated for the purpose of rendering us more happy than heretofore; but, for the more effectually securing the safety of those creatures on the one hand, and, on the other, to humble, in some degree, the daring spirit of the English subjects. Since nothing the sagacity of the legislature could invent, can have a greater tendency to baffle and over-awe the natural firmness of the English temper, than to deprive them of the privilege of a jury of their peers, in trials of a criminal nature. Here the eminent wisdom of that body manifestly appears, who has most ingeniously evaded the above privilege, by investing the civil magistracy with an almost discretional power of convicting and punishing offences against the above dog-law.

This power, no doubt, must be very discreetly placed, since experience tells us, that a number of these respectable gentlemen have not the least feeling for the generality of the human species, as some of them have been active agents in wantonly shedding the blood of their fellow-creatures: whilst others have made use of their interest and power, to screen the most barbarous and unprovoked murderers from justice. This the more imboldens us to pray the legislative body, that they will of their eminent goodness, please to put us on the present dogly footing, under the protection of those respectable gentlemen now in the commission of the peace; trusting, that the alienation of their tenderness to the human specie, may be an addition of it to that of the brutal, to whom their minds seem to have been the most of kin, we shall also rely on the protection of the magistrates, with regard to the safety of our lives, with the firmest confidence, by reason that out bodies are no ways applicable for food. Many of those gentlemen being remarkably unmerciful to such animals as gratify most the delicacy of their appetites, we also humbly entertain the most cheering hopes of being favourable considered by the legislative body, on account of our numerous, faithful, and important services, which in all ages far surpass all that the most strenuous advocate for the dogs can boast of; witness Whittington's most famous and most memorable Cat, whose eminent services will be handed down with a veneration to the latest posterity. Our general demeanor too, we hope, will not fail to be some recommendation to us, as we are in no wise prone to the many enormous vices that distinguish the dogs.

We therefore humbly flatter ourselves, that our protection will as least be made equal to theirs; though nature has not induced us with the pleasing power of hunting out delicious game, for the service of our legislative and executive benefactors; many of whom. In both departments, are much more pleased with eating than thinking. Yet it is to them in particular we can recommend ourselves; for in what a disgustful plight would all the costly dainties of the epicure's table appear, if not guarded by our ever-watchful tribe, from the ravages of the Danish and Norwegian troops of devouring vermin, the Rats. With these, and the lesser invaders the Mice, proportionately calculated for destruction, we faithful Cats are engaged in perpetual war for the preservation of human property. Diligently extending our care to all kinds of provisions, and almost every necessary of life; the very title-deeds of your immense fortunes would with difficulty be preserved from the tattering vermin, were it not for the faithful watchings of our nocturnal guards. The Record altered by a Lord Chief Justice to a most courtly purpose, might have perished, had we been off our duty. To us you owe the preservation of his Majesty's most gracious speeches from the throne: together with his Majesty's most gracious answers to the City remonstrances; which speeches and answers being masterly compositions of true English constitutional spirit, we voluntarily engage to defend from all damages by our common and numerous enemies: but as magna charta and the bill of rights are now become useless, it is needless to pledge our faithfulness in the security of them, as they are no longer of value; but the return, made by order of the honourable House of Commons, at the late Middlesex election, in favour of Co. Lutterell, we will engage to preserve against the united force of all the Rats and Mice in Europe, in honour of the brave gentleman, who possesses a great share of our confidence and esteem; and as we expect that our rough and catified petition will meet with some opposers, we rely greatly on that gentleman's abilities in our favour, as he is known to be a nonsuch in the opposing way; he having gloriously, at one time, with 296 overthrown an opposition of 1143, to his immortal honour: he has the honour also to be held in great esteem by his Majesty, and his ministers, who admitted him into the royal presence, while the prostrate Lord Mayor, attended by the Aldermen, and Sheriffs, presented the City Remonstrance; at which time our hero, in imitation of our nimble catish advances, mounted a table, from whence he made an awful figure: and perceiving his Majesty laugh at the City officers, he complaisantly fell in with the merriment, and grinned like we Cats, by whom he stands almost adored. Now, as this important person is a favourite of the King's, and at the same time an imitator and favourite of our tribe, we have the most lively hopes, through his friendly influence, to get our grievances and apprehensions removed; when we shall, as in duty bound, ever pray, in our poor catish manner, that the justice of heaven may reward his actions.

NORTON GRIMALKIN, Praeses.

THE ADVENTURES OF A CAT

Anon. "The Adventures of a Cat." The Westminster Magazine, Or, the Pantheon of Taste, Aug. 1774: 393-397.

Part II - "The Adventures of a Cat." The Westminster Magazine, Or, the Pantheon of Taste, Sept. 1774: 459-463

Whenever a new face makes its appearance upon the bon-ton, the first enquiries are, "Who is she? = What's her name? – Of what family?" To the first question I answer, May it please your Ladyship, I am a CAT. To the second I reply, Mopsey. And to the last, I have the honour to descend by my father's side in a right line from the famous mouse-catching cat of Whittington's; and by my mother's I am an immediate descendant of Tibsey, a favourite tortoise shell of the unfortunate Dido's Queen of Carthage. Should any ill-natured critic think it worth his while to contradict me, by affirming that her Majesty of Carthage had no cat, I shall even leave him to enjoy his own opinion; as I know by experience, whenever a critic is resolved to think himself right, it must be more than human evidence to convince him he is wrong.

In London I first drew my breath; and scarcely had the first dawn of light visited my eyes, before I became an unhappy spectator of the cruelty and inhumanity of those two-legged monsters who stile themselves the Lords of the Creation: This was no other than witnessing the death of four of my brothers and sisters, who were all wantonly immerged into cold water, while their cries only served as sport to the barbarous authors of their misery.

I know not by what miracle I chanced to escape a watery death; and notwithstanding the detestation in which I held this world, I must acknowledge I was not a little pleased at finding myself reserved for some future whim of Fate.

My present master's name was Mr. Jeremiah Sparkle, a jeweller of no small repute, as he served ost of the demi-reps of quality. He was parsimonious to a proverb; and it was observed, he never made any dots to his i's, or strokes to his t's, so very careful was he lest he should be accused of extravagance. However, his avarice was amply balanced by his son's prodigality. Jack was a Buck of the very first water. Lovejoy's and the Bedford rang with his exploits. No man could roast a parson, kick a waiter with such a grace; yet, notwithstanding the amplitude of his talents, he frequently met with his match, which was as often witnessed by the melancholy evidence of two black eyes.In this condition Jack made his appearance one morning before his father. The old gentleman, as usual, gave him much good advice, which the son regarded no otherwise than by humming over the end of an Opera tune: however, as the prudent father accompanied his admonition with a bank note, Jack in an instant cleared up his countenance, and stammered out, " ‘Tis very right as you say, Sir; and – so – Sir, I wish you a good morning."

Perhaps the Reader may wonder what induced Mr. Jeremiah to behave so generously to his son, more especially as he has been already represented as an object of frugality. Know then, that Jack was in possession of a large fortune left him by a deceased relation, who had appointed his father guardian. The old man supplied him liberally with money, in hopes that some-time or other, by running into the vices of the Town, his son might get himself knoked on the head; or, what was more probably, he might fall a sacrifice to his debaucheries. This was the good man's motive for indulging him in his prodigality, as he himself was in want: of Jack's fortune to complete his own plum. As to the salutary advice he had given him, he considered himself, as his father, bound to offer his that; though, at the same time, he most ardently hoped the other would not follow it.

Scarcely had Jack taken his leave, before a coach stopt at the door, from which issued a Lady, who, by her dress, might easily have been mistaken for a duchess. "Your servant, Mr. Sparkle; I want a diamond necklace." "I'll shew your La'ship one of the finest in Europe. – Only observe the brilliancy of that stone; - the very workmanship is of more value than all the baubles in Cox's Museum." " ‘Tis very pretty, Mr. Sparkle; what is the price?" – "A thousand guineas, Madam." – "Is that the lowest, Mr. Sparkle? – Bless me! What a pretty creature! I insist upon having that charming Cat into the bargain: and, do you hear, Mr. Sparkle? Book the necklace to Lord C--."

I was immediately resigned into the possession of this queen of diamonds; and the coach conveyed us to an elegant house near Soho, which I found belonged to this mistress of mine, who was a celebrated toast, and was then in keeping by a certain Nobleman, to whom, however, I soon learnt she was not so constant as was consistent with gratitude.

Her father was a half-pay officer, whose abilities extended no further than in placing her with a milliner in the Strand. As she possessed a handsome person, with the advantage of a tolerable education, she soon began to consider herself as formed to move in a more extensive circle than that of a milliner's shop. According, Colonel M–of the Guards having seen her, se listened to the first overtures of his passion, and by his contrivance eloped from her mistress to find an asylum in the arms of her admirer. But as satiety too soon follows enjoyment, the Colonel shortly after discharged her to seek a keeper elsewhere. With no great matter of money, and nearly in a state of despondency, by the greatest luck in the world she chanced that evening to go to Ranelagh; and almost the first person she saw was Lord C–e, who had a few days before discharges his Dulcinea, and was actually then looking out for another. They soon entered into conversation; and his Lordship, finding her disengaged from the Colonel, generously offered her a carte blanch, which she was too prudent to refuse; and that same evening she went home in his Lordship's carriage.

About an hour after my arrival at this new habitation, the servant announced Captain S--. I soon perceived, by the novelty of their salutation, that they were no new acquaintances. "Well, Harriot," says the Captain, "how does your old Lord do?" – "Do!" replied the Lady; "it is impossible he should do much." This brilliant speech was concluded by a hearty laugh, though for the life of me I could not find out where the joke lay. A conversation now took place, which the Reader will excuse my not repeating, and which was soon interrupted by the maid, who informed them that his Lordship was coming up stairs. The Captain was in an instant stationed to the closet; and by his facility in entrance, it appeared that this was not the first time of his occupying that respectable post.

Upon his Lordship's entrance, I was at a loss to guess what occasion so emaciated a figure could have for a mistress; but I have since learned, that his Lordship is not the only person that keeps a mistress to look at. She received him with an easy, cheerful countenance, and gently chid him for staying from her so long, which he endeavoured to excuse by pointing out the necessity he was under of attending the House. After some insipid chit-chat she produced the necklace, and begged his Lordship's opinion of it. He answered her no otherwise than by demanding what is cost? To which she replied, she had got it a monstrous bargain; and notwithstanding Mr. Sparkle protested it cost him much more, yet he had been so obliging as to rate it to her only at a thousand guineas.

Nothing can equal the Peer's astonishment at this information. – "A thousand guineas, Harriot!" exclaimed he; "and do you think any man's abilities capable of administering to your extravagance at this rate?" – "O, my Lord," replied the Lady, coolly, "if your Lordship does not choose it, you know there are others that will; there is no compulsion required. Besides, my Lord, I received another message to-day from the Baronet; I dare affirm he would not hesitate at presenting me with ten times the value of such a trifle." – "Zounds! Madam, do you term a thousand guineas a trifle?" cried his Lordship, his eyes all the while glistening like those of a rattle-snake. "O, if your Lordship's in a passion," returned his mistress, "why – I have no more to say;" at the same time carelessly throwing the unconscious cause of their dispute out of her hand.

The Captain, who had advance as near as possible to the door of the closet for the better convenience of listening, in varying his position unfortunately overturned a tea-equipage; and the noise of the fractured China in a moment rousing his Lordship from a momentary reverie, he forced open the door just time enough to be witness to the Captain's scape; which he effected by taking the lover's leap out of the window.

The Peer, now thoroughly sensible of his mistress's infidelity, very wisely discharge her, which she submitted to with the greatest composure; and notwithstanding the love she affected for me; she left me without the least regret to the compassion of his Lordship; who seeing something in me superior to the common race of my species, resigned me to the care of his servant, with orders to take me to C–house. I must confess I was not a little pleased at being released form the sight of so abandoned a creature; more especially as I exchanged her service for that of a nobleman so universally respected as Lord C--.

As soon as I arrived at C–house, his Lordship introduced me to is Lady, whose character I soon had the pleasure to be acquainted with. Perhaps Nature never exhibited a stronger instance of benevolence and credulity that she manifested in her Ladyship. She was an universal friend to the necessitous; she was eyes to the blind, and feet to the lame; to meet with redress required no other means than to declare your wants. Yet with this natural goodness of heart she was so exceedingly weak, as to implicitly believe every circumstance that cunning or artifice might suggest to her; by which means she was too frequently laid under contribution by the undeserving.

But the most remarkable trait in the composition of her character, was, a firm persuasion that every man who saw her was in love with her; by which means her Ladyship was often led into some ridiculous situation, rather mortifying to her vanity.

A well-known Doctor, who from a walking Physician is transform into a walking Author, having written a Treatise upon the Virtues of Mustard Seed, was somewhat ambitious of having the honour to dedicate it to his Lordship, which favour he hoped to gain through the influence of his Lady. Accordingly, have brushed his only suit of black, he one morning waited upon her Ladyship at C–house, and by the servant craved an audience upon an affair of consequence. Her Ladyship, who was in an undress, having expeditiously put on her fly, gave orders for the Doctor's admittance. The first salutation being over, the author proceeded to assure her how much he was her Ladyship's humble servant; which she, as usual, construing into a regard for her person, asked him with a tremulous accent, where he had seen her before? "Madam," replied the Doctor, "to the best of my knowledge this is the first time I ever had the honour of seeing your Ladyship." - "Perhaps, then you have heard me described! I have read of astonishing effects from such a circumstance." – "Yes," answered the author; "I have frequently heard your Ladyship's character painted in the most amiable colours." – "Well, Sir, and what would you have me do for you?" – "Why, if your Ladyship would but indulge me so far as grant me the favour" – "Grant you the favour!" interrupted the Lady. "Merciful Heavens! What have I done to deserve such usage? From your appearance, Sir, I expected, at least, common civility; but I find I am deceived. However, as I consider it more my misfortune than yours, I shall punish you no further than by banishing you from my presence for ever." In vain the astonished investigator of mustard seed endeavoured at an explanation; in vain he affirmed he had no intention of offending her Ladyship. She turned a deaf ear to all his remonstrances, and he was fain to take his departure without an opportunity to boast of her Ladyship's favours.

During the twelve months I continued with her, I was frequently a witness to some such an adventure; nor could all the gravity of a Cat at times restrain the sallies of risibility which they occasioned: however, after I had resided there about a year, a certain Right Reverend Bishop taking a liking to me, begged me of her Ladyship, and with her concurrence I was presently conveyed to his Lordship's palace. The Bishop was a patriot, and always sided with the Minority. His name appeared the first on the list upon every occasion of a Protest. Yet, notwithstanding his patriotism, he possessed so much of the Mammon of unrighteousness as to wink at any simoniacal contract, provided his interest was consulted/

The truth of the above I had an opportunity of being a witness of, the very next morning after I had the honour to attend upon him. A living in his Lordship's gift becoming vacant, he was waited upon by the Curate, who had truly discharged the duty of his office upwards of twenty years, much to the satisfaction of the parishioners, requesting his Lordship's favour to succeed the Rev. Mr. Flint, as Rector. The Bishop, with a truly prelatic sneer, exclaimed, "Pray, Sir, what should I see in your face to induce me to present you with a living of two hundred pounds a year?" – "My Lord," respectfully returned the Curate, "I humbly apprehended, that being twenty years a labourer in the vineyard of the Gospel would have excus'd me in preferring my fruit." – "On my conscience," replied the Prelate, "I fancy the fellow's turn'd Methodist! Hark'ee Mr. I tell you the living is not for you; so get about your business; and, do you hear? If you ever appear before me on any future occasion, divest yourself of that cant, or I'll strip your gown over your ears." The unfortunate Curate despairingly took his leave of his dignified brother; and whilst the tears stood quivering in his eye, he only silently exclaimed, "The Lord's will be done!"

Reader, be thou male or female, protestant or Papist, a Poet of a Privy-Counseller, I assure thee upon the veracity of a Cat, that the fate of the poor Curate so sensibly affected me, that I wanted but little to make me cry, so truly did I sympathize with his misfortune.

Soon after the Curate was discharged, a fine, full-fed figure entered, whose errand I found was much the same as the other's. Their appearance was not more opposite that their method of addressing the Patron. "My Lord," said this jolly son of the church, "I am inform'd your Lordship is promoting a subscription for the furtherance of the Christian religion in foreign parts; as it certainly is praise-worthy undertaking, your Lordship will permit me to contribute my mite." So saying, he presented his Lordship with a note for five hundred pounds. "I am exceedingly pleased to find you so charitably disposed, Mr. Guzzle," replied the Bishop. "Indeed, as this life," continued he, "is so very uncertain, we should be always prepared for death, which we cannot do better than by being kind to our necessitous brethren. Apropos! Have you heard of the death of Mr. Flint?" – "You surprize me, my Lord!" exclaimed this hypocrite, "this is, indeed the first I heard of it. Has your Lordship resolved as to the presentation?" – "Why, not absolutely," replied the Prelate; "however, I shall take your advice as to that; I think it lies very contiguous to your rectory of Tithum, if one could but depend upon a dispensation." – "O, my Lord, if your Lordship will give me leave, I have no doubt of getting that." – "Well, Mr. Guzzle, I give it you, upon the condition that when you are charitably disposed again, you make me your almoner."

I lived long enough with his Lordship to see that the Laity are not the only ones who have a relish for the good things of this world. – I had remained six months with the Bishop, when one evening the devil put it into my head to enjoy the benefit of a little fresh air by getting to the door. I had scarce been there a moment, before a fellow in a vulgar, tawdry livery caught me up in spite of all my agility, and proceeded with me at a strange rate through the City, without slackening his pace till we arrived at the Mansion-house.

Misfortune, says the Stagyrite, is the lot of mortal; or, to speak in the sublime language of the Homer of the North, "Rejoice not, O man! In thy prosperity, nor count with thyself upon the continuance of they felicity. Soon shall they happiness appear as a dream, and shew they tat it was founded upon the pinnacle of insecurity. To-day thou art in the prime of they strength; healthful as the fawn of the forest; bounding as the mountain doe; thoughtless as his copper Majesty, in Berkley-square; and beautiful as the terrace of the New Adelphi. But, lo! To-morrow's fun shall behold thee fallen; shall view thee solitary as a discarded Minister, emaciated as a Temple Beau, discontented as a City Politician, and disagreeable as London Bridge. So an order from the Board of Works arrives: A murmur is heard from afar; the workman seize their instruments of destruction, and presently the Wonder of St. Martin's, the Beauty of the Seven-Dials, lies prostrate with the earth!"

Reader, there's a specimen of the Sublime for thee! Which even my great original, Mr. Macpherson, must acknowledge for a Cat. But to resume the thread of my adventures.

Notwithstanding the change in my situation required me to summon forth all my philosophy, yet when I reflect that "Priam from Fortune's lofty summit fell," I began to be more reconciled to my fate, and to consider a Citizen as composed of the same materials as a Lord.

It was in the Mayoralty of Jemmy Contract (the blackness of whose heart but ill agreed with the gold chain which hung dangling at his breast) I first commenced Cit. Jemmy was a mere ingrate: he would not have scrupled to mount to public honours on the back of the devil; but his point once carried, he would have served his Highness in the same manner as he had been known to have served his best friends. – Yet Jemmy's a Patriot! His principal friend and counsellor was Parson Brentford, who condescended to be his tool in every dirty transaction. The following conversation which happened between these two friends, a few days after my residence in the Mansion-house, will serve to throw some new lights on the political sentiments of this Castor and Pollux of Patriotism.

"O Parson!" says Jemmy, "I am glad you are come; I want your assistance to punish that hot-brained fellow, Sir Griffin Goofe. Since the King has knighted him, the fool imagines every man his inferior. Suppose we attack him in the Public!" – "An excellent thought, my Lord!" replied the Parson, "and conclude it with a challenge!" – "Bravo!" says the Magistrate; "but be sure you don't challenge him in private." – "Never fear, my Lord," replied the Churchman; "I am not so fond of that exercise as some folks may imagine: besides, your Lord ship knows there's a material difference betwixt saying and doing." – "Yes, so it seems," says Jemmy, "or your black coat had been dyed red before this time." – "True, my Lord, and your Lordship would have scratched for your old Friend W–in the Court of Aldermen, had this not been the café. Your Patriotism, my Lord, is nearly upon and equality with my courage; much talked of, but seldom used."

This curious conversation concluded with a flaming letter to the Knight, which, however, did but little execution.

Jemmy, whose avarice gained the ascendancy over every other consideration, kept so indifferent a table that it was no miracle I began (after such high living as I had before experienced) to look thin and impoverished and to pine after the flesh-pots of Egypt. As it occurred to me that it was impossible to change for the worse, I was resolved to effect my escape from this mansion of famine; which resolution I that very evening put into execution.

It was nearly midnight when I set out; and proceeding with the utmost circumspection Westward, I travelled on, without any material accident, till I had reached the Strand; but before I had penetrated half way through it, I found it impossible to proceed from the number of prostitutes that at all hours infest that street: I therefore found myself under an absolute necessity of seeking an asylum in the first place I could find.

It was not long before Fortune favoured me so far as to point me out such a place; into which I crept, and sincerely blessed the negligence of the servant, who had, so luckily for me, left the kitchen window open. My master was a humble Retainer to one of the Theatres; generally known by the name of Billy Bustle. Billy is a Critic, and may be seen the first night of every new play in the Twelve-penny Gallery, retailing out left-handed sentiments to girls of the town, and attornies clerks. He is the echo of the Manager, the diabetes of sense, the shadow of wit, and the oracle of the Green-room. Whenever his friend the manager deigns to oblige the world with a specimen of his miraculous abilities, they you may see him armed with a large oak stick, the very first to begin applauding; grinning, and shrugging up his shoulders, as though he had been bit by a mad paragraph-writer.

Notwithstanding Billy is by no means a stranger to the attacks of vanity, he is, nevertheless, too well convinced of the fallibility of his own judgment, to depend upon it in the least particular. He is, therefore, remarkably careful to notice the observations of those who may chance to sit next him, whose opinion he immediately adopts as his own, till somebody else happens to differ from him; making it an invariable rule, that the las speaker cannot chuse but be right.

I lived with this curiosity two months, during which period I was frequently led to admire the depth of his critical sagacity; when one day, without having ever before vouchsafed to bestow the least notice upon me, he took me in his arms, and proceeded with all the gravity of a Philosopher with me towards the water-side.

"By the sacred memory of my grandmother, thought I, my time is come!" My fears, however, were ill-founded; for stopping with me at a house, which I found belonged to Mr. Patent the Manager, he was admitted to an immediate audience.

"Say," says Billy, "I think I heard you observe yesterday, that you were in want of a Cat; now, if you think as how this here will do, she is at your service." – "I thank you, Mr. Bustle," replied his friend; "you are ever attentive to my wants; but pray was you at the House last night?" My master having answered him in the affirmative, he proceeded – "Well, and how did I behave? – Did I play as well as usual? – Don't you think there was a falling off? – Come, answer me with the candour of a friend." – "A falling off! No, Heaven forbid!" replied Billy; "why, I was never so pleased in my life. I'm sure, I was frightened at your eyes, and then I cried from the beginning to the end." – "Cried!" exclaimed the astonished Manager – "Why, it was a Comedy! – You mean, I supposed, you laughed." – "To be sure," says Billy, "that is, - that is, as a body may say _ I cried to think what a loss the world will sustain whenever you shall retire from the stage; - tho', to be sure, I laughed – yes, yes, I laughed, sure enough, now I think of it. But, Sir," added he, "I came partly to ask your advice about a circumstance that greatly troubles me. You know there is a new Comedy to be performed nest week; now since the Authors have got into this new stile of writing, I am often puzzled to know when I should laugh and when cry. I have already asked the opinion of my friend Tom Vamp here, just by, but it seems he is as ignorant as myself."

"Why, to confess an honest truth, my Friend," says Mr. Patent, "I am as ignorant as either of you can possibly be; however, I fancy you may indulge yourself in either of these passions, without danger of erring."

Here they were interrupted by the entrance of a young man, who cam to give the Manager a specimen of this abilities for Stage elocution. As he came stronger recommended, Mr. Patent was under and absolute necessity of granting him a hearing; previous to which, he first enquired if he could read. Being answered in the affirmative, he next proceeded to interrogate him, whether or no he thought himself capable of getting up a pantomime? If he could jump through a cask, eat fire, walk upon his hands, or do any of them there sort of things? Of all these qualification the other expressed a profound ignorance. "Well, but you say you can read," exclaimed Mr. Patent; "come then, let me hear you recite Sternbold and Hopkins's version of the Hundred and Nineteenth Psalm." The candidate for the buskin was astonished, and even ventured to express some surprize at the injunction; which the Manager observing, told him, it was always his custom; and indeed nothing could be more proper, as our modern plays consisted of little else besides a string of proverbs and sentiments, much of the same nature as the work he had recommended to his consideration, only labouring under the disadvantage of being turned into dialogue.

His recitation not proving agreeable to the wishes of the Manager, he (after he had given him a specimen of his own talents, by reading part of one of the late Mr. Whitefield's Hymns) discharged him, by desiring him never more to direct his mind to the Stage. The disconsolate and disappointed candidate had not been gone many minutes, before his loss was supplied by the entrance of Dicky Cumbersome. Sentimental Dicky is an Author, a Poet, a Critic, and a Politician; he is Secretary to the Graces, and first Wardrobe-Keeper to the Muses; the Flower of Gallantry, the Quintessence of Sentiment, and the Caput-mortuum of Wit.

Dicky was just come from the perusal of Gulliver's Travels, where he had learnt that the inhabitants of a kingdom, the latitude of which I am not thoroughly acquainted with, made use of certain instruments called flappers, consisting of blown bladders in which were inclosed a small number of pebbles; and that by means of gently applying these instruments to the ear of the auditor, many wonders had been effected. Dicky, who is well acquainted with the construction and organization of the human ear, fancied he had discovered another method, which, nevertheless, would tend to produce a similar effect. Accordingly, full of these hopes, he repaired to the Manager, upon whom he was resolved to make the first experiment.

The moment he entered, Mr. Patent leaped up to embrace him; when Dicky, throwing himself into a Ciceronian attitude, addressed him in the following very elegant and classical manner:

"Divine Epitome of Perfection, Master-piece of Nature, and Wonder of the Universe! Thou Summary of all that Euripides thought, of Terence conceived! the Treasury of Knowledge, and the Summit of Sublimit! What are Princes in comparison with Thee? Or what the Kings of the earth, when Thou art named? Homer was lofty and nervous, Virgil-majestic and poetical, and Shakespear glowing and descriptive. But what are their merits when weighed against thine? Thou are Homer, Virgil, and Shakespear united! Tragedy is not high enough, but they genius will outsoar it; nor Farce so low, but thou canst level thy talents to it. Prodigious production of Maturity! Surely, all the Muses assisted at thy formation. Discord was banished from the elements, the winds were hushed, the sea was calm, and universal harmony alone prevailed through all the works of Nature!"

Here Dicky ceased. – The Manager leaped upon a pile of his own St. James's Chronicles, which very luckily happened to be then in the room; upon which he stood a tip-toe, stretched out his neck like a cock in the attitude of crowing, and thrice he cried "hem!" – "Hem!" echoed Billy Bustle. "My dear fiend," says Mr. Patent, addressing himself to the orator, "you make a very fine speech! A very fine speech, to be sure, Mr. Cumbersome; but then you want action; that is, you have not the – the – the – you put too much of the – the – the – the – you understand me, Mr. Cumbersome?" – "Perfectly well, Sir," replied Dicky; "I think few people understand you better than I do."

"Well – but, Mr. Cumbersome, tell me how I can serve you?" – "Why, Sir, I have a Piece I would beg your assistance in getting up, and which, from the fondness of the Town for Sentimental Novelty, I have not the least doubt but will prove acceptable. But first, I must inform you, Sir, that travelling lately down in the West of England, curiosity induced me to become spectator of a puppet-show. The story selected for our amusement was that of Mr. Richard Whittington and his Cat, of famous memory. Now, Sir, a thought struck me during the representation, of converting this same wonderful performance into a regular Comedy; which requires nothing more than only creating three or four new characters, that may easily be done.

When the exhibition was concluded, I made application to the Master of the Shew, requesting he would permit me to take a copy of his manuscript; which he very readily granted me, and which I have here with me. I shall select a passage or two for your ear, and which I doubt not but you will agree with me in pronouncing truly sublime and grand."

Scene draws, and discovers the King and Queen at dinner, several large Mice enter, and run away with the provision. King draws his sword and kills two of them; after which the Queen speaks.

QUEEN .

"Great Sir! ‘tis time you Highness would determine

To rid the kingdom of these cursed vermin;

A thund'ring Cheshire Cheese, as I'm a sinner,

I lock'd up safe but yesterday at dinner.

Secure I thought it; but upon a sudden

They eat it all – and eke a large Plum-Pudding."

KING.

"A Cheshire Cheese! – Ah me! – O Heav'n confound ‘em!

Ye cataracts and hurricanes drown ‘em!

Plum-Pudding, too! – Is that a mouse's breakfast?

O, may the next within their gullets stick fast!

What, all at one fell sweep! – Devouring evils!

Must they, ye Gods! with pudding stuff their devils?"

"Enough, enough, my friend," says the Manager; "I am fully satisfied as to the merits of the Piece. The Author undoubtedly must have been a man of uncommon genius, and from whom our great Shakespear seems to have borrowed some hints. Cannot you see an evident similarity betwixt the King's massacre of the mice, and Lear's killing the two ruffians in the last act? Nay, is it not demonstrable, that the whole scene in Macbeth, where Macduff receives the first intelligence of the murder of his wife and child, is nothing more than an exact copy of the King's pathetic exclamations for the loss of his Cheese and Pudding?"

"But, Sir," says the Poet, "we shall want a Cat."

Billy Bustle reminded them of me: thought was applauded, and I was instantly approved of. Dicky, however, presently after started an objection. "In an original picture of Whittington, now in possession of Dr. Trefoil, his Cat," says he, "is depicted as having neither ears nor tail; and you know we ought to do everything in character."

"Give yourself no uneasiness about that," replied the Manager; and immediately ringing the bell, he, with the greatest coolness, gave the necessary orders, which were no sooner received than executed, and I was in an instant divested of those ornaments which so materially constitute the beauty of a Cat; and knowing it would avail nothing to resist, I bore this stroke of fortune, barbarous as it was, with a fortitude even astonishing.

I have now lived with Mr. Patent upwards of a year, in which time I have been witness of so many scenes as would surprize an ordinary reader. I have seen Authors of merit insulted, and Coxcombs caressed; I have seen Performers of eminence discharged, to make room for an engagement in such as can't read; I have seen Sense and Shakspear banished, to encourage Pageantry and Pantomime. In a word, I have lived here long enough to see Folly triumph over Taste, and Flattery over Candour.

To add to my mortification, I am informed that Mr. Cumbersome has concluded his Piece, which is ordered for immediate rehearsal, and in which I am to make my appearance. That it may the first night meet with the fate it merits, together with the whole catalogue of Pantomimes, Installation, and Jubilees, is the sincere prayer of the Public's most humble servant.

MOPSEY.

Adelphi, Sept.

"A DEFENCE OF CATS."

Serio-Jocosus in Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure March 1796: 172-175.

The Cat Will Mew – Shakspeare.

To vindicate the innocent from the sneers of calumny and the attacks of malice, to rescue the worthy from misrepresentation, and the helpless from tyranny, has ever been the province of the wife man, and the peculiar attribute of the good. Far be it from me, however, to insinuate that my humble endeavours should entitle me to more than the reward of honest intention. To the praise of goodness I can but faintly aspire, and to the character of wisdom I dare not look. But at a time when a general disposition is shown to rescue the oppressed and bring forward modest merit, why may not I contribute to the mass of public benevolence, by vindicating one who has solaced the hours of languor by her playful fascination, and has guarded the necessaries of life for midnight depredation?

It has been ever a matter of surprise with me, that so useful an animal as a cat should labour under the oppression, and have to contend against the danger of popular prejudice. That a cat should be an object of terror, is absurd; that she should be an object of aversion, is unaccountable. Harmless to all above her, whom can she injure that ought to be preserved; a foe to the vermin under her, whom does she kill, that ought not to be destroyed? Yet some persons are so delicate that they cannot touch a cat, some cannot bear them in a house, and some, as our immortal bard has it, ‘are mad, if they behold a cat!' let us consider the character of this animal, and investigate whether there be any real cause why she should be segregated from the brute creation to be the wanton prey of ‘prentices and butchers' boys.

To describe the cat is needless. Naturalists tell us that they can see in the dark. If so, here is a proof of the superiority at least of one sense, which they possess. How many persons are there who are most lamentably deficient in eyesight even in open day, and with the advantages of a meridian sun! Persons, who not only cannot see dangers and hazardous steps; but cannot even be made to see their own interest, and whose sight is so truly capricious and uncertain, that they cannot perceive their own relations unless mounted in a coach or some similar vehicle. Such may well be said to ‘grope at noonday.'

So much for the external senses of this animal. With regard to the mind, it has been very strongly reported that cats are deficient in gratitude. Now, let us for a moment suppose this to be true. What does it amount to? It amounts only to this, that a cat, an animal whose education is very shamefully neglected, falls into a vice which some of the most enlightened and best scholars in the kingdom are not free from at all times, and which some of the most wealthy and dignified of our species, are notoriously guilty of. But this state of the case is not strictly true. A cat is certainly a grateful animal; when stroked and fed, she sings the song of satisfaction and complacency; her features brighten, and her language, if we could understand it, would convey an expression of thankfulness. What proof, then, have we of the ingratitude of this animal?

A very fine one, forsooth, - ‘That however kind you are to a cat, if you attempt to play with her, she will turn, and bite and scratch you, as soon as any other person.' – Now, gentle reader, this objection affords us a fine demonstration of what is generally meant by gratitude. Indeed I know not an instance that throws more light upon it. Here you are to feed an animal, and because you have fed it, you are to torment it (which is called play) without it feeling pain, or endeavouring to defend itself. Benefits are bestowed that insults may be acceptable; pleasure is given that pain may follow. Such doctrine may suit an absolute slave, but a cat is a free and independent animal, and will die in defence of herself from wantonness and cruelty. If this be the kindness to which gratitude is expected to follow, I grant there is a great deal of it in the world, but it deserves a very different name. Such is the kindness of the selfish to their dependents. They take them to their houses to triumph over their misfortunes, to secure their hardest services, and they expect gratitude, because – because what? They do not add starvation to their other sufferings. Enough gratitude!

In confirmation, however, of what has been advanced on this subject in favour of the feline tribe, let us quote, in substance, what all naturalists, and all old women are agreed upon; namely, that all the views of a cat are confined to the place where it has been brought up; if carried elsewhere it seems lost and bewildered. Neither caresses nor attention can reconcile it to its new situation, and it frequently takes the first opportunity of escaping to its former haunts. Frequent instances are in our recollection (say they) of cats having returned to the place whence they have been carried, though at many miles distance, and even across rivers, when they could not possibly have any knowledge of the road or situation, that would apparently lead them to it. Now, does this look like ingratitude for protection and food? Does it not point at the very opposite virtue, and does it not argue that they have less of a gadding, visiting turn, than any other of the inhabitants of the house? It may be objected, indeed, that they do sometimes absent themselves for two or three days together; but this is for the wise and natural purpose of increasing their species; and, in this respect, if one may believe the records of Doctor's Commons, which are certainly credible enough, they do not differ very materially from animals of a much higher order.

And this leads me to consider of two objections, which apparently are more difficult to surmount than any which we have yet stated. These regard the moral character of cats. It is commonly asserted that they are remarkably deficient in the articles of chastity and honesty. With regard to the first, I shall be very brief. They labour under certain defects in their education, which renders them rather indiscriminate in their intrigues; but let it be remarked, that though they sometimes disturb the peace of families, and their amours make a considerable noise in the world, yet they are the most tender and affectionate of mothers, always suckling their young, and behaving to them with a kindness that ought to be exemplary to those who perhaps would disdain such an example. They never desert their young, till they are able to provide for themselves; but when that period arrives, they disdain to bring them up in idleness, and they send them into the world with faculties as well adapted to earn a subsistence as their parents enjoyed before them. I cannot help thinking that this is very much to the honour of the feline race; for idleness is the root of all evil, and parents who bring up their children in such a habit, only prepare insult and contempt for themselves, and bitterness for the hour of death.

With respect to honesty, much may be said on both sides; but dishonesty is not upon the whole peculiar to cats. What of it we find among them is owing to a variety of causes. First, hunger; to the cravings of which they sometimes give way, and take a little provisions by stealth; but they never assault those who are in possession of plenty, otherwise than by their importunities, and their suit may be rejected, if not without the danger of contempt, at least without the risk of injury. Secondly; temptations are often held out to them, which are too much for frail nature; a cupboard door open, or a piece of mutton invitingly placed in their way, are what they seldom can resist, if hungry. Besides, for any thing they know to the contrary, such articles may be placed in their way on purpose, and when they find out their error, it is generally at the expence of a good beating – a punishment which does not attend errors, at least wilful ones, quite so often as would be very convenient in society.

Having now got rid, and I hope with conviction, of the main objections to cats, I might condescend to notice many scandalous reports propagated by interested persons, by servants, and by rat-catchers. The former are always in league together to bring the cat into disgrace, by imputing to her the breaking of china, cups, glasses, and twenty other things, in the destruction of which it is impossible to conceive that a cat can be seriously interested one way or other. As to rat-catchers, the cause of their enmity needs be no secret. Jealousy of success is the cause of ill will, and unneighbourly behaviour in all trades. Any thing, therefore, they may think proper to say against their fourfooted brethren, ought to be received with great allowance and, like the evidence of an accomplice in a court of justice, regarded only as it may be corroborated by persons of a very different character. Gay, in one of his excellent fables, has put words into the mouth of a cat, which ought for ever to shut that of the rat-catcher. Puss says, in answer to the rat-catcher's obloquy:

In every age and clime, we see,

Two of a trade can ne'er agree:

Each hates his neighbour for encroaching;

‘Squire stigmatises ‘squire for poaching;

Beauties with beauties are in arms,

And scandal pelts each other's charms;

Kings too their neighbour kings dethrone,

In hope to make the world their own:

But let us limit our desires;

Nor war like beauties, kings, and squires;

For though we both one prey pursue,

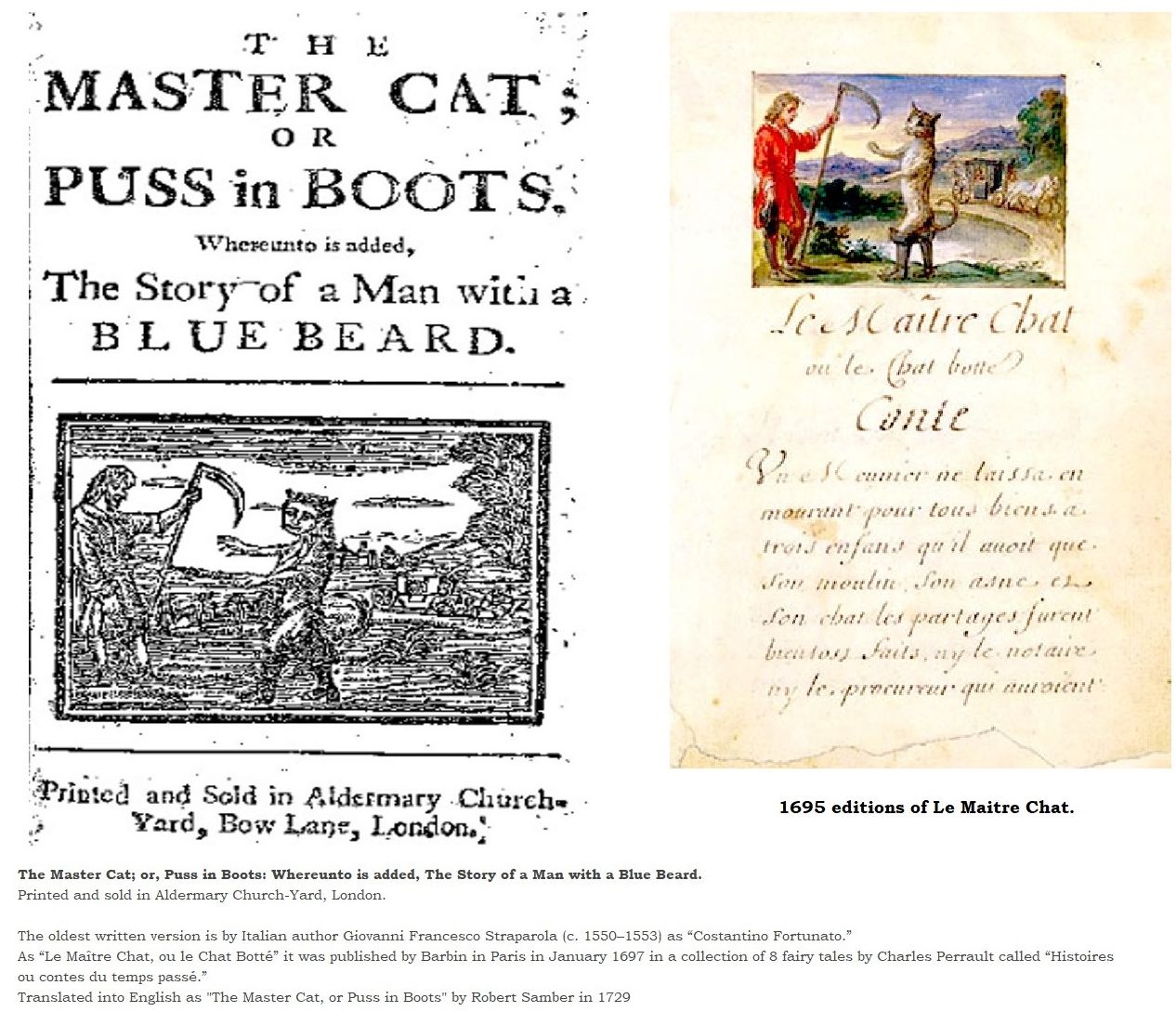

There's game enough for us and you.'