DOMESTIC CATS

From

ANIMAL LIFE:

A Complete Natural History For Popular Home Instruction And For The Use Of Schools

by Alfred Edmund Brehm

Published 1895

THE CAT FAMILY

If asked to whom the place of honour among the Beasts of Prey belongs, no Man would be long in doubt as to the family he should name. The Lion was crowned king of the beasts at a remote period of time, and so we first turn to his tribe, which is that of the Cats, or Felidae.

The Cats are the most perfect and typical members of the family of Carnivora. No other group presents the same symmetry of limb and body and the same regularity of structure. Every part of the body is lithe and graceful and this is why these animals are so pleasing to our aesthetic sense. We may safely regard our domestic Cat as representative of the entire family.

PHYSICAL FEATURES OF THE CAT FAMILY

We may assume the structure of the body to be known; the strong, yet, graceful body, the round head set on a stout neck, the limbs of moderate length, the long tail, and the soft fur corresponding in colour to the surrounding objects, are features with which everybody is familiar. The weapons with which the Felidae are endowed are perfect. The teeth are formidable, the canines being large, strong, very little curved and so perfectly adapted to life-destroying action that the small incisors are hardly noticeable beside them. The tongue is thick and muscular, and is supplied with fine, horny thorns, whose points lie towards the throat. The teeth are not the only weapons possessed by the feline animals, their claws being no less terrible instruments for seizing their prey and speedily terminating its existence. Their broad, rounded paws are proportionately short; for the last toe-joint is curved upwards. In repose and in ordinary walking two tendons keep the member in its upright position; but when the animal is angry and needs its claws, a strong flexor muscle inserted below draws it down, stretches the paw and makes it an effective weapon. This structure of the feet enables the Cats to walk without leaving any traces of the claws, and the softness of their step is due to pads upon their soles. The Cats are both strong and agile and their every movement displays vigour and lithesome grace. Nearly all members of this family partake of the same physical and moral traits, although some special group may seem to have a particular advantage over the others.

All Cats walk well, but slowly, cautiously and noiselessly; they run quickly and can jump distances that exceed many times the length of their respective bodies. There are only a few of the larger species that are unable to climb; the majority being greatly skilled in this accomplishment. Although as a rule averse to water, they swim well, when necessity compels; at least, none of them can easily be drowned. Each member of this family knows how to curl up its handsome body and reduce its compass, and all are experts in the use of their paws. The large species can strike down animals larger than themselves with one stroke of the paw and force of their spring. They are also capable of carrying considerable burdens, and easily convey to a convenient hiding place animals they have killed, although their prey may be as large as themselves.

ACUTE SENSES OF THE CAT FAMILY

Of their senses those of hearing and sight are the most acute. The ear undoubtedly is their guide on their hunting expeditions. They hear and determine the nature of noises at great distances; the softest foot-fall or the slightest noise from crumbling sand is not lost upon them, and they are thus able to locate prey that they cannot see. The sight is less keen, though it cannot be termed weak. Probably they are unable to see distant objects, but at short range their eyes are excellent. The pupil is round in the larger species and dilates circularly when the animal is in a state of excitement; smaller species show an elliptical pupil, capable of great dilation. In the daytime it shrinks to a narrow slit under the influence of the bright light; in darkness or when the animal is excited, it assumes a nearly circular shape.

The sense coming nearest to that of sight in keenness is probably that of touch, which manifests itself in sensibility to pain and other outward conditions as well as in a discriminating faculty of feeling. The most sensitive organs are the whiskers, the eyebrows, and, in the Lynx, probably also the ear-tufts. A Cat with its whiskers cut off is in a very uncomfortable plight; the poor thing is at a complete loss to know how to act and shows utter indecision and restlessness until the hairs have grown out again. The paws also seem endowed with an exquisite sense of touch. The entire family of Cats is very sensitive; being susceptible to all external impressions; showing decided dissatisfaction under disagreeable influences and a high degree of contentment under agreeable ones. When one strokes their fur they exhibit a great deal of pleasure; while if the fur is wet or subjected to similar repulsive impressions, they display great discomfort.

Their smell and taste are about equal in degree, though perhaps taste may be somewhat the more acute of these two senses. Most Cats appreciate dainty morsels, in spite of their rough tongue. The remarkable predilection of certain species for strong-smelling plants, like valerian, admits only of the conclusion that the sense of smell is very deficient, as all animals with a well-developed organ of smell would shrink from them with disgust; while Cats jump around these plants and act as though they were intoxicated.

MENTAL ENDOWMENT OF THE CAT TRIBE

As to intellect Cats are inferior to Dogs, but not to such an extent as commonly supposed. We must not forget that when instituting a comparison we always have in mind two species that can scarcely be regarded as fair standards: on the one hand the domestic Dog, systematically bred for thousands of years, and on the other the neglected and often ill-treated domestic Cat. The majority of the Felidae show a higher development of the lower instincts than of those that are noble and elevating; yet even our Kitty demonstrates that the Cat family is capable of education and mental elevation. The domestic Cat often furnishes instances of genuine affection and great sagacity. Man usually takes no pains to investigate its faculties, but yields to established prejudice and seems incapable of independent examination. The character of most species is a blending of quiet deliberation, persevering cunning, blood-thirstiness and foolhardiness. In their association with Man they soon lose many of the characteristics of the wild state. They then acknowledge human supremacy, are grateful to their owner, and like to be petted and caressed. In a word, they become perfectly tame, although their deep-rooted, natural faculties may break out at any moment. This is the principal reason why the Cats are called false and malicious; for not even the human being who habitually torments and ill-treats animals accords them the right of revolting now and then against the yoke of slavery.

The Cats are well distributed throughout the New and the Old World, except in Australia, where only the domestic Cat is found, many of which have there degenerated into the wild state. They inhabit plains and mountains, arid localities and marshy districts, forests and fields.

FOOD AND HUNTING METHODS OF FELINES

The food of the feline family consists of all kinds of vertebrates, preferably mammals. Some show a predilection for birds, a few others are fond of Turtles, and some even go fishing. All species pursue the same methods when attacking their destined prey. With stealthy footfall they creep over their hunting ground, listening and looking in all directions. The slightest noise makes them alert and incites them to investigate its origin. They cautiously glide along in a crouching position, always advancing against the wind. When they think themselves near enough, they take one or two leaps, fell their prey by a blow in the neck with one of their fearful paws, seize it with their teeth and bite it a few times. Then they open their mouth slightly but without letting go of the victim; they watch whether any sign of life remains, and then again close the teeth upon it. Many of them utter a roar or a growl at this time, which expresses greed and anger as much as satisfaction, and the tip of the tail wags to and fro. The majority have the cruel habit of tormenting their prey, seemingly giving it a little liberty, sometimes even letting it run a short distance, but only to pounce upon it at an opportune moment, and then repeat the operation over and over, until the animal dies of its wounds. The largest members of the Cat family shun animals which offer great resistance, and attack them only after experience has taught them that they will be victorious in the fight.

The Lion, Tiger and Jaguar, at first acquaintance, fear Man and avoid him in a most cowardly manner. It is only when they have seen how easily he is conquered that some of them get to be his most formidable enemies. Though nearly all Felidae are good runners, yet most of them give up their intended prey if they do not succeed in the first attempt. It is only in secluded places that they will eat their prey on the field of capture. Usually they bear away the killed or mortally wounded animal to a quiet hiding-place, where they devour it at their leisure.

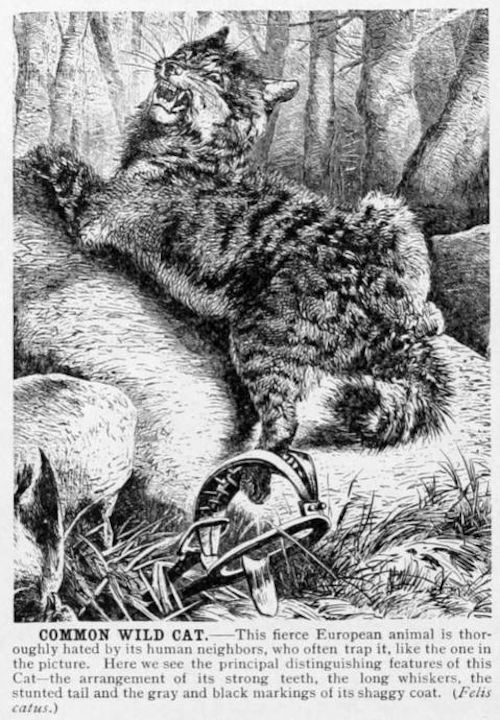

THE CAT KIND AND ITS YOUNG

As a rule the female gives birth to several cubs at a litter, but seldom to one. We may say that the number varies between one and six; although some species are declared to have more than the latter number. The father, as a rule, is indifferent or hostile to the offspring, the responsibility and care resting upon the mother. A feline mother with her young ones is a very pleasing spectacle. Motherly tenderness and solicitude are expressed in every gesture and in every sound, the voice being gentle and soft to a surprising degree. Her watchfulness is so unremitting that one cannot doubt the absorbing love she has for them. It is very gratifying to observe how carefully she trains them from earliest youth in habits of extreme cleanliness. She cleans, licks and smooths their fur unceasingly, and will tolerate no dirt near the lair. At the approach of a foe she defends her offspring with utter disregard for her own life, and at such times the mothers in all the larger species are most formidable enemies. In many species the dam must protect her little ones from their father, who, if not prevented, will enter the lair and devour them while in their stage of blindness. This, probably, is the origin of the feline habit of mothers hiding their little ones.

When the latter have grown somewhat older, the aspect changes, and they have nothing more to fear from the father. Then begins the merry childhood of the little animals, for they are full of fun and play. Their nature is revealed in the first movements and emotions, their play being nothing but a preparation for the serious hunts of their adult life. Everything that moves attracts their notice; no noise escapes them; the slightest rustle makes the little listeners prick up their ears. The earliest delight of these young ones is their mother's tail. They first watch it in its movements, and soon the whole mischievous company tries to catch it. The mother is not in the least disconcerted, but continues to express her moods by the wagging of that member. In a few weeks the little ones are able to indulge in the liveliest romps and the mother joins them, no matter whether she be a stately Lioness or one of our domestic Pussies. Sometimes the whole family forms a single ball, and each is intent upon seizing the tail of the other.

As they grow, the games become more serious. The little ones learn that their tail is but a part of themselves and long to try their strength on something else. Then the mother brings them small animals, sometimes alert live ones, then those that are half-expiring. These she turns loose, and the little fellows practice upon them, in this way learning how to pursue and handle their prey. Finally the mother takes them along on her hunts, when they learn all the tricks — the stealthy approach, the mastery of their emotions, and the sudden attacks. When they become completely independent of parental care they leave their mother, or their parents, as the case may be, and for some time lead a solitary, roaming life.

The harmful species are hunted zealously, and there are men who find the keenest enjoyment in the very danger of this sport.

SUBDIVISIONS OF THE CAT SPECIES

The classification of the Felidae is very difficult; yet we think it proper to divide them into the Cats proper (Felis); the Lynxes (Lynx); the Cheetah (Cynailurus) and the Foussa (Cryptoprocta) of Madagascar. A typical specimen of the first group is our domestic Cat and its most highly developed members are the Lion and Tiger. The Lynxes have a shorter tail and longer limbs than the Cats proper and have hair tufts on their long ears. The Cheetah has longer limbs and the claws are not retractile. The last family, the Foussa or Cryptoprocta, has a dentition differing from the other groups, hairless soles and other peculiarities which place it among the distant relatives of the Civets or Viverridre, and stamp it as a being similar to the first original Cat, from whom the others have descended.

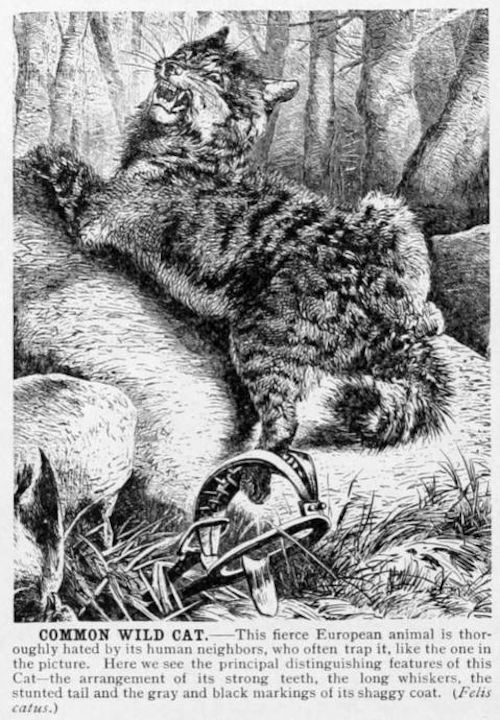

THE COMMON WILD CAT.

The Common Wild Cat (Felis catus) is the only one of the family that has not been quite exterminated in the Old World countries, like Germany. For a long time it was thought to be the ancestor of our Domestic Cat, but closer investigation does not support this belief. The Wild Cat is considerably larger than Kitty. It may be distinguished from the latter at a glance by its thicker fur, its larger whiskers, its ferocious look and its stronger teeth; its head is thicker, and its tail is fuller and shorter, does not taper toward the end, and is ringed in grey and black. The throat shows a whitish-yellow spot, and the soles of the feet are black or dark.

The Wild Cat attains a weight of sixteen or eighteen pounds. Its height at the shoulders is about sixteen inches; its length from snout to tip of tail, forty to forty-five inches, the tail measuring twelve or thirteen inches.

The fur is long and thick, grey in the male, yellowish grey in the female. The face is yellowish, the ears are russet grey on the outside and yellowish white on the inner side. Four black bands run from the forehead backward between the ears, and two of them uniting run along the spine and the upper side of the tail. From this band others of a rather faded dark colour proceed downwards, dying away on the abdomen, which has a yellow colour, dotted with black spots. The eyes of the animal are yellow.

COMMON WILD CAT. This fierce European animal is thoroughly hated by its human neighbours, who often trap it, like the one in the picture. Here we see the principal distinguishing features of this Cat — the arrangement of its strong teeth, the long whiskers, the stunted tail and the grey and black markings of its shaggy coat. (Felis catus.)

WHERE AND HOW THE WILD CAT LIVES

The Wild Cat inhabits all parts of Europe, with the exception of the north, or more especially Scandinavia and Russia. In Germany it inhabits all the wooded mountains, though not in very large numbers. The southeast of Europe is particularly well stocked with it. In the lower parts of the Alps it is very common. It is also frequent in Spain and France, and Great Britain has not yet quite exterminated it. Outside of Europe it has only been found in Grusia, south of the Caucasus. Great, thick forests, especially gloomy woods of the pine, and fir-tree, are its favourite haunts. The more deserted a district is, the more devoted is the Wild Cat to it. It prefers rocky forests to all others, as rocks afford so many places of concealment. Besides it lives in the holes made by Badgers and Foxes, and in hollow trees.

The Wild Cat lives in company with others of its kind only during the breeding season and while its young ones are dependent on it. At all other times it leads a solitary life. The young separate from the mother at an early age and try hunting on their own account.

The Wild Cat begins its activity at dusk. Endowed with excellent organs of sense, cautious and cunning, noiselessly creeping up to its prey and patiently watching its opportunity, it is a dangerous foe to small and moderate sized animals. It lies in wait for the bird in its nest, the Hare on the ground, the Squirrel on the tree. It kills larger animals by jumping upon their backs and severing the carotid artery with its sharp teeth. It also shows its genuine feline nature by renouncing its intended prey, if the first leap is unsuccessful. Fortunately its principal nutriment consists of Mice of all kinds and small birds. It is only occasionally that it seeks for larger animals. Still, it is a fact that it attacks Fawns and Roes, and is strong enough to cope with them. It keeps watch by the banks of lakes and rivers for fish and birds and catches them very adroitly. It is extremely destructive in parks and game preserves.

Considering its size, the Wild Cat is a very dangerous Beast of Prey, especially as it is guilty of the bloodthirstiness that distinguishes all of its kindred. For this reason hunters detest it and pursue it without mercy. No sportsman gives it due credit for all the Mice it kills. How many of them it destroys may be seen from Tschudi's statement that the remains of twenty-six Mice were found in the stomach of one Cat. Zelebor examined several stomachs of Cats of this species and found them to contain the bones and hairs of Martens, Fitchets, Ermines, Weasels, Marmots, Rats, Mice, Squirrels and birds. Small mammals, therefore, form its principal food, and as Mice are the most frequent among these, we are inclined to think that the good services of the Wild Cat more than compensate for the mischief it does. It exterminates more harmful than useful animals, and if its attributes do not endear it to the hunter, our woods profit by its activity.

HUNTING THE WILD CAT

The Wild Cat is hunted with a considerable amount of zeal. Zelebor says: "It is the most difficult thing in the world to draw a live Wild Cat from the hollow of a tree. Two or three of the strongest and boldest men, with hands protected by tough gloves and a wrapping of rags, will find both strength and courage taxed to the utmost by the effort to drag one of these Cats from such a retreat and put it in a bag." I must confess that the chances of success of this method of hunting these animals seems dubious to me, for all other writers agree that to hunt a grown Wild Cat is no joke.

Winckell advises sportsmen to proceed with caution, not to delay with the second shot if the first does not kill outright, to approach the Cat only when it has been completely disabled from moving, and even then to give it a finishing stroke before touching it. Wounded Wild Cats driven to bay are very dangerous. Tschudi says : "Take good aim, hunter ! If the beast is only wounded, it curves its back, lifts its tail straight up, and makes for the sportsman with a vicious, hissing snort, and buries its sharp claws in his flesh, preferably his breast, so that it can hardly be torn away; and such wounds are extremely slow to heal. It has no fear of Dogs, but will of its own accord, and before it sees the hunter, often come down to them from a tree; and the fight that ensues is fearful. The fierce animal uses its claws to good purpose, always aiming at the Dog's eyes, and fights with desperate energy until the last spark of its tenacious life is extinguished."

We must carefully differentiate the Wild Cat proper from stray domestic Cats that may have degenerated in the woods. The latter are frequently met with, but they never attain the size of the Wild Cats, though greatly exceeding that of the domestic Cat. They are as ferocious and dangerous as the Wild Cat, and after several generations have been born wild in the forest these animals come to resemble their progenitor, the Egyptian Cat, in colour and tint, though they always lack the blunt tail, the light spot at the throat and the dark soles of their ancestor. The animal known as Wild Cat in the United States is very different from the European animal of that name and is in reality a Lynx. (See Red Lynx.)

FEMALE WILD CAT AND YOUNG. In the forests of Europe the Common Wild Cat makes its home. This is not the animal commonly known in America as the Wild Cat, the latter being really the Red Lynx. The European animal is a true Cat, larger than the domestic species and very fierce and bloodthirsty, preying upon all mammals and birds it can master. Yet like all felines it rears its young with great tenderness and affection. Here is a family of Wild Cats which has its home in a hole in the rocky forest. The mother has just returned with dinner for the Kittens, who are welcoming her with voracious expectancy. (Felis catus.)

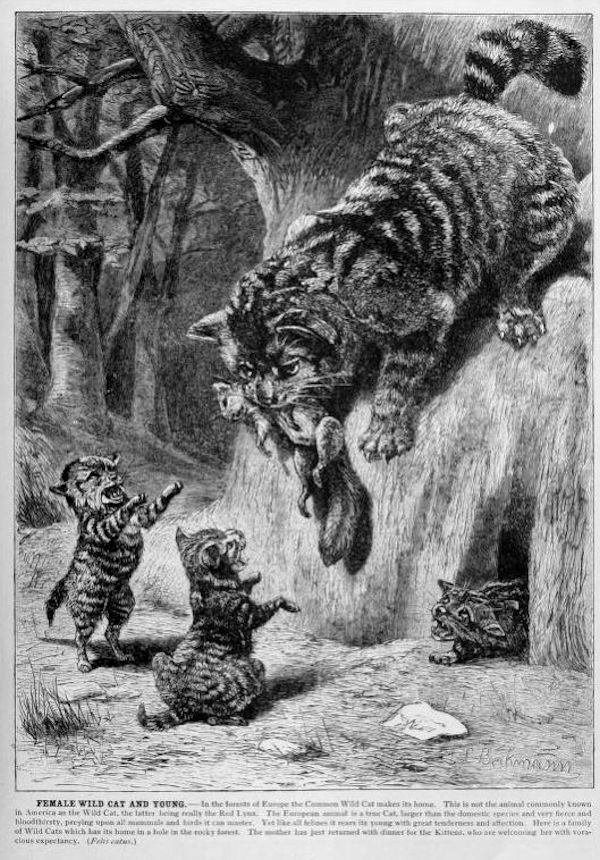

THE EGYPTIAN CAT.

The next member of this group is the Egyptian Cat (Felis maniculata). Ruppell discovered it in Nubia, on the western bank of the Nile, in a desert where rocky stretches of country alternated with bushy tracts. Later writers have found it in Soudan, in Abyssinia, in the innermost centre of Africa and in Palestine. The length of its body is about twenty inches and its tail measures a little over ten inches. These are not the exact dimensions of our domestic Cat, but they approximate them closely.

The arrangement of the colours of the fur is much like that on some of our Cats. The mummies and pictures on Egyptian monuments agree most closely with this species, and evidently tend to prove that this was the domestic Cat of the Egyptians. Perhaps the priests imported it into Egypt from southern Nubia. It probably extended thence to Arabia and Syria, and later to Greece, Italy and the remainder of Europe, and in more modern times, emigrating Europeans spread it still farther.

The observations of Schweinfurth in the Niam-Niam country are of great weight as evidence that the Egyptian Cat is the original stock from which the race of our domestic Cats descended. He says that the Egyptian Cat is more common in the Niam-Niam country than in any other part of Africa that has been fully explored, so that the centre of the continent might be considered the point from which it spread. The Niam-Niam do not possess a domestic Cat, in the proper meaning of the word, but their boys capture the Egyptian Cat and wholly or partially tame it. At first they are tied in the vicinity of the huts, and soon become completely at home in the house, where they make it their business to catch the Mice which infest these dwellings in great numbers.

VENERATED BY THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS.

Ebers in "An Egyptian Princess," says : "The Cat was probably the most sacred of all the sacred animals which the Egyptians regarded with veneration. Herodotus says that when one of their houses was on fire, the Egyptians first thought of saving the Cat and then of putting out the fire, and when a Cat died they cut off their own hair as a sign of mourning. When a person wittingly or unwittingly caused the death of one of these animals, he forfeited his life. Diodourus himself saw a Roman citizen, who had killed a Cat, put to death by a mob, though the government, in its fear of Rome, tried its best to pacify the people. Dead Cats were artistically embalmed, and of all mummified animals that are found, the Cat, carefully swathed in linen bandages, is the most common."

The Egyptian Cat. This picture has a familiar look, the resemblance to the house-cat being so marked. Although still disputed by some naturalists the great weight of authority shows the Egyptian Cat to be the progenitor of our domestic feline. The markings of the fur in the Egyptian Cat are shown in the picture, and no differences from the house-cat are observable that cannot be accounted for by the wild life led by the former. (Felis maniculata.)

THE DOMESTIC CAT.

All researches point to the fact that the Cat was first tamed by the Egyptians, and not by the Hindoos, or any northern people. The old Egyptian monuments speak clearly in pictures, signs and mummies, while the records of other nations do not even give us food for conjecture. The very fact that the mummies of both the domestic Cat and the common Jungle Cat are found supports me in my opinion, for this goes to prove that when Egypt was in the meridian of its power, its inhabitants extensively caught and probably tamed the Jungle Cats. Herodotus is the first Greek to mention the Cat, and it is but slightly alluded to by even later Greek and Roman writers. We may conclude, therefore, that the animal spread very gradually from Egypt. Probably it first went East. We know, for instance, that it was a favourite pet of the prophet Mohammed.

In northern Europe it was barely known before the tenth century. The Codex of Laws in Wales contains an ordinance fixing the price of domestic Cats and penalties for their ill-treatment, mutilation and killing. The law declared that a Cat doubled its value the moment it caught its first Mouse; that the purchaser had a right to require that the Cat have perfect eyes, ears and claws, to know how to catch Mice, and, if a female Cat, to know how to bring up her Kittens properly. If the Cat failed to meet any of these requirements, the purchaser had the right to demand a return of one-third of the purchase money.

This law is of great value as furnishing proof that in those times domestic Cats were held in high estimation, and also because we learn by plain inference from it that the Wild Cat cannot have been the progenitor of the domestic species, as Great Britain was overrun with Wild Cats, whose young ones it would have been easy to tame in unlimited numbers.

THE DOMESTIC CAT ALMOST UNIVERSAL

According to Tschudi, the Cat now inhabits all parts of the globe except the extreme north and the highest altitudes of the Andes, and has established itself wherever civilization, progress and domestication have penetrated. But notwithstanding the fact that it is an inmate of human habitations throughout the world, the Cat reserves to itself a large measure of independence and only recognizes Man's authority when obedience suits its inclination. The more it is petted, the greater becomes its affection for the family; the more it is left to its own devices the more its attachment is directed toward the house in which it was reared rather than to the people who live there. Man always determines the degree of tameness and domesticity of a Cat by his conduct towards it. When neglected it is likely to take to the woods in summer. Sometimes it becomes quite wild there, but usually comes back at the approach of winter, accompanied by its Kittens if any have been born to it during its vacation. It is often the case that after such a sojourn in the woods the Cat shows little liking for people, and this is especially noticeable in warm countries. Rengger tells us that Cats live in a particularly independent state in Paraguay, although Cats that have become really savage are seldom seen in that country, and the localities abandoned by white Men are also deserted by Cats.

DOMESTIC CAT WORTHY OF STUDY

Our domestic Cat is an excellent specimen for the purpose of studying the whole feline family, for it is accessible to all. It is an exceedingly pretty, cleanly and graceful creature. Its movements are stately and as it walks with measured tread on its velvety paws, with claws carefully retracted, its footfall is imperceptible to the human ear. It is only when pursued or suddenly frightened that it displays any precipitous haste, and then it proceeds with a succession of jumps which soon carry it to a place of safety, for it profits by every advantageous nook or turn and can climb to any height. With the help of its claws it clambers up trees or walls easily, but on level ground a Dog can overtake it without difficulty.

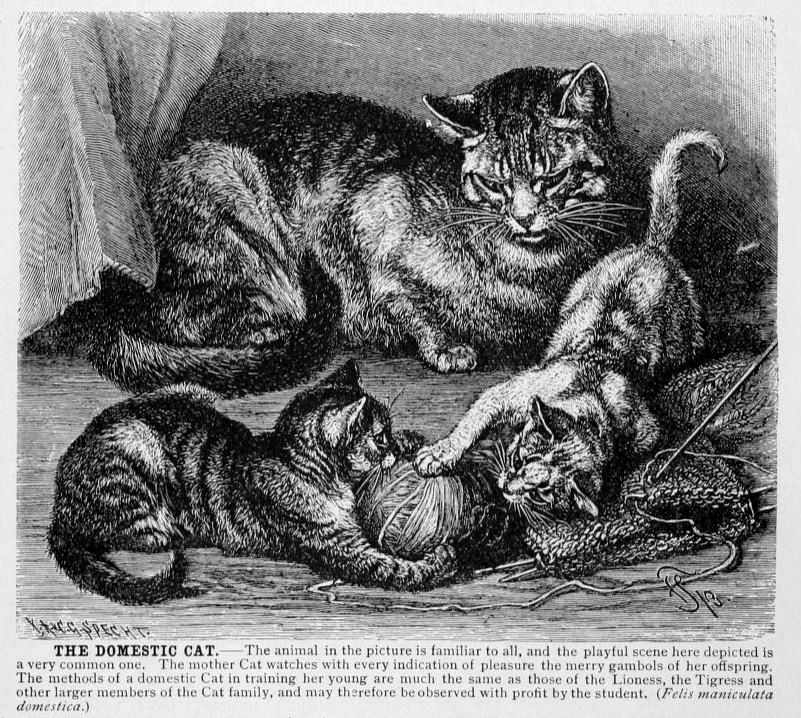

THE DOMESTIC CAT. The animal in the picture is familiar to all, and the playful scene here depicted is a very common one. The mother Cat watches with every indication of pleasure the merry gambols of her offspring. The methods of a domestic Cat in training her young are much the same as those of the Lioness, the Tigress and other larger members of the Cat family, and may thsrefore be observed with profit by the student. (Felis maniculata domestica.)

However a Cat is dropped, it will always alight on its paws, the pads of which soften the violence of the fall. I have never succeeded in causing a Cat to fall on its back, even when I have dropped it from close range over a chair or table. As soon as I would let go it would instantly turn over and stand on its feet quite unconcerned. How it is able to accomplish this feat, especially when the short distance is considered, is quite a mystery to me. In falling long distances, it, of course, regulates its position in alighting by means of its tail. The Cat can also swim, but it practices this accomplishment only when there is an urgent need for it, and it probably never enters the water of its own accord, as it even shows a great dislike of rain; but there are exceptions, for Haacke knew a Cat which was in the habit of jumping into a pond and catching Goldfishes. In sleeping, the Cat likes to curl up in a soft, warm place, but cannot bear to be covered. I have noticed that Cats show a decided liking for hay as a bed, probably because the fragrance is agreeable to them. After a nap on such a bed their fur usually has a very pleasant odour.

Of the senses those of touch, sight and hearing are the strongest in the Cat. The sense of smell is rather dull, as anybody can see when the creature is offered a favourite dainty in such manner as to prevent it from using any other sense in the effort to determine what it is. If the whiskers are used, the result is different, for they are very sensitive organs of touch; so are its paws, but in a less degree. The eyes are excellent and capable of seeing by night as well as by day. But the palm undoubtedly belongs to its sense of hearing. Lenz tells us that he was once sitting outdoors with a Kitten in his lap; suddenly it jumped backwards after a Mouse, which was running unseen on a smooth stone pavement from one bush to another and did not make a particle of noise that a human ear could detect. He measured the distance at which the Kitten had heard the Mouse running behind it and it proved to be fully fourteen yards.

NOTEWORTHY QUALITIES OF THE CAT

The intellectual capacities of the Cat are usually quite misunderstood. People consider it a treacherous, deceitful, sly animal, that is not to be trusted. Many confess to an unconquerable feeling of antipathy towards it. As a rule it is compared with the Dog, which ought never to be done; and as such comparison shows that the Cat does not possess the Dog's good qualities, the conclusion is frequently drawn that there is no use of any further investigation. Even naturalists are given to pronouncing prejudiced and one-sided opinions against it. I have sympathetically studied the Cat from my childhood, and therefore accept the following description of Scheitlin's, which certainly possesses the merits of originality, understanding and just appreciation: "The Cat is an animal of a high order of intelligence. Its bodily structure alone indicates this. It is a pretty, diminutive Lion; a Tiger on a small scale. It shows the most complete symmetry in its form — no one part is too large or too small. That its every detail is rounded and beautiful is even shown by an examination of the skull, which is more symmetrical than that of any other animal. Its movements are undulating and graceful to the extent that it seems to have no bones. We value our Cats too slightly because we detest their thievish propensities, fear their claws and love their enemy, the Dog, and we are not able to show equal friendship and admiration for these two opposite natures.

"Let us examine the Cat's qualities. We are impressed by its agility, yet its mind is as flexible as its body. Its cleanliness of habit is as much a matter of mental bias as physical choice, for it is constantly licking and cleaning itself. Every hair of its fur must be in perfect order; it never forgets as much as the tip of its tail. It has a discriminating sensibility as to both colour and sound, for it knows Man by his dress and by his voice. It possesses an excellent understanding of locality and practices it, for it prowls through an entire neighbourhood, through basements and garrets and over roofs and hay-sheds, without bewilderment. It is an ideally local animal, and if the family moves it either declines to accompany them or, if carried to the new residence, returns at the first opportunity to the old homestead; and it is remarkable how unerringly it will find its way back, even when carried away in a sack for a distance of several miles."

THE MOTHER CAT AND KITTENS

When the mother Cat gives birth to her Kittens there are usually five or six Kittens in the litter, and they remain blind for nine days. The mother selects for her young ones a secluded spot and hides them carefully, especially from the Tom-Cat, which, if he found them, would make a meal of them.

Young Kittens are beautiful little animals, and their mother's love for them is unbounded. Whenever she scents danger she carries them to some place of safety, tenderly lifting them by compressing the skin of their necks between her lips so gently that the little Kitties scarcely feel it. During the nursing period she leaves them only long enough to forage for food. Some Cats do not know how to take care of their first young ones and have to be initiated into the duties of motherhood by Men or by some old experienced Tabby. It is a proven fact that all mother Cats learn how to care for Kittens better and better with each succeeding litter.

A Cat during the suckling period tolerates no Dog or strange Cat near her Kittens; even her owner is an unwelcome visitor at such a time. At the same time she is particularly open to compassion for others. There are many instances on record where Cats have suckled and brought up young Puppies, Foxes, Rabbits, Hares, Squirrels, Rats and even Mice; I myself have tried similar experiments successfully with my Cats, when I was a boy. Once I brought a little Squirrel yet blind to one of my Cats. Tenderly she accepted the strange child among her own, and from the first cared for it with motherly solicitude. The Squirrel thrived beautifully, and after its step-brothers had all been given away, it stayed and lived most harmoniously with its foster mother, and she then regarded it with redoubled affection. The relations between them were as close and tender as possible. They understood each other perfectly, though each talked in its own language, and the Squirrel would follow the Cat all over the house and into the garden.

INTELLIGENCE AND AFFECTION OF CATS

It is commonly thought that Cats are incapable of being educated; but this is an injustice. They are also capable of constant affection, and I have personally known some which moved with their owners from one house to another and never thought of returning to their former home. They were well treated, and therefore thought more of the people than of the house. They will allow those they like, and especially children, to take incredible liberties with them, nearly as much, in fact, as Dogs will. Some Cats accompany their owners in their walks, and I knew two Tom-Cats which usually followed the guests of their mistress in the most polite manner. They would accompany them for ten or fifteen minutes and then take their leave with many an amiable purr, expressive of their good will. Cats often strike up friendships with other animals, and there are many instances where Dogs and Cats have become fast friends, in spite of the familiar proverb.

ANECDOTES ABOUT THE CAT

There are a great many anecdotes illustrating the intelligence of this excellent animal. Once our Cat gave birth to four charming little Kittens, which she kept carefully hidden in a hay-shed. Three or four weeks later she came to my mother, coaxingly rubbed against her dress, and seemed to call her to the door. Mother followed her, and the Cat then joyfully ran across the yard to a hay-shed. Soon she appeared in the door of the upper story carrying in her mouth a Kitten, which she dropped down upon a bundle of hay. Three other Kittens followed in like manner and were made welcome and petted. It proved that the Cat had no more milk to give her young ones, and in her dilemma bethought herself of the people who gave her food.

Pechuel-Loesche had a Cat which had struck up a friendship with an old Parrot, and would always go to it when the bird called its name: "Ichabod." When the Parrot interrupted the Cat's slumbers by biting its tail the latter never showed the least resentment. The two friends were fond of sitting together at the window, looking out at the passing sights.

In my native village a friend of mine lost a little Robin Redbreast and in a few days his Cat brought it back in its mouth unharmed. Thus it had not only recognized the bird, but caught it with the intention of pleasing its master. Therefore I also believe the following story to be true: A Cat lived on very good terms with a Canary bird and frequently played with it. One day it suddenly rushed at it, took it in its mouth and growling climbed up on a desk. The terrified owner, on looking around, perceived a strange Cat in the room. Kitty had distrusted her sister and thought it best to rescue her friend from the other Cat's clutches.

GREAT USEFULNESS OF THE CAT

From all these accounts we must conclude that Cats are deserving of the friendship of Man, and that the time has come at last to correct the unjust opinions and prejudices many people hold against them. Besides, the usefulness of Cats ought to be taken more into account. He who has never lived in an old, tumble-down house, overrun with Rats and Mice, does not know the real value of a good Cat. But when one has lived with this destructive plague for years and has seen how powerless Man is against it, when one has suffered day after day from some fresh mischief and has become thoroughly enraged at the detestable rodents, then he gradually comes to the conclusion that the Cat is one of the most important domestic animals, and deserves not only tolerance and care, but love and gratitude. The mere presence of a Cat in the house is sufficient to render the impudent rodents ill-humored and inclined to desert the place. The Beast of Prey pursuing them at every step, seizing them by the neck before they have become aware of its presence, inspires them with a wholesome terror; they prefer moving away from a locality defended in this way, and even if they remain, the Cat soon gains a victory over them.

Mice of all kinds, notably house and field Mice, arc the preferred game of the Cat, and most Cats will also wage war upon Rats. Young and inexperienced Cats catch and kill Shrews, but do not eat them, as their powerful scent repels them; older Cats usually leave these odourous animals unmolested. The Cat finds variety in its diet by hunting Lizards, Snakes and Frogs, May-Bugs and Grasshoppers. The Cat exhibits as much perseverance as dexterity in its hunting. Being a Beast of Prey at heart, it is also guilty of many little depredations. It destroys many an awkward young bird, attacks rather grown-up Hares, catches a Partridge once in a while, lies in wait for the very young Chickens in the yard, and under some circumstances goes fishing. The cook is usually not on speaking terms with it, for it proves its domesticity by visiting the pantry whenever it has a chance. But the sum total of its usefulness by far exceeds all its peccadilloes.

VARIETIES OF THE DOMESTIC CAT

The Domestic Cat (Felis maniculata domestica) embraces but few differing species. The following colourings are the most common: black with a white star on the breast; white, yellow and red; brown and striped; bluish grey; light grey with darker stripes, or tri-coloured, with white and yellow or yellow-brownish and coal-black or grey spots. The bluish grey Cats are rare, the light grey ones very common. The most handsome Cats have dark grey or blackish brown stripes like a Tiger. It is a peculiar fact that tri-coloured Cats, which in some localities are regarded as witches, and for this reason slain, are nearly without exception females.

THE ANGORA CAT, A DISTINCT VARIETY

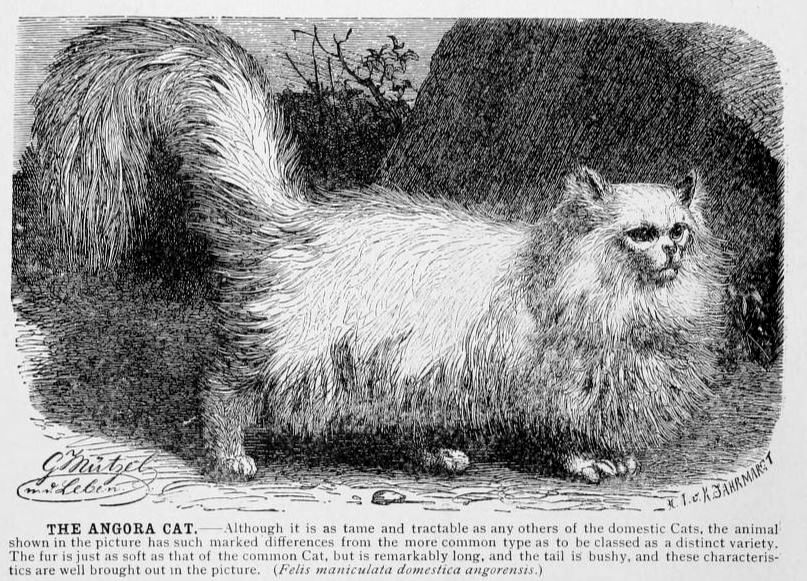

The Angora Cat (Felis maniculata domestica angorensis ) is usually regarded as a quite distinct variety of the domestic Cats. It is one of the most beautiful Cats, distinguished by its large size and long silky hair, which is either a pure white or assumes a yellowish, greyish or mixed tinge. The lips and soles are flesh-coloured.

THE ANGORA CAT. — Although it is as tame and tractable as any others of the domestic Cats, the animal shown in the picture has such marked differences from the more common type as to be classed as a distinct variety. The fur is just as soft as that of the common Cat, but is remarkably long, and the tail is bushy, and these characteristics are well brought out in the picture. (Felis maniculata domestica angorensis.)