THE DISEASES OF DOGS AND CATS AND THEIR TREATMENT.

BY A VETERINARY SURGEON.

1893.

PUBLISHED AT THE OFFICES OF THE BRITISH AND COLONIAL DRUGGIST,

42, BISHOPSGATE WITHOUT, LONDON, E.C.

PREFACE

In presenting this treatise on the diseases of dogs and cats to our readers, we do so with confidence in its value as a vade mecum on the subject.

It is written by a veterinary surgeon of very large experience, who has made the smaller domesticated animals a special study, and condensed in the pages of a comparatively small book more practical information than can be found in any similar work. It has been the aim of the author to avoid technical terms and the scientific jargon which often does duty for plain and concise instruction, but, being written for the use of chemists, the formulae are expressed in the ordinary language of the dispenser.

The need of such a work has been long recognised in the trade, but not supplied. It is impossible within the covers of a single work to afford chemists and druggists the information required on horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, dogs, cats and poultry, and we have endeavoured to avoid such a mistake by offering our readers a work which can be thoroughly relied upon for directions as to the treatment of those animals about which the chemist is so often consulted, and for which he may easily acquire a reputation, adding to his business a profitable branch which has been generally neglected by Veterinary Surgeons, who prefer to devote their attention more exclusively to horses and cattle.

INTRODUCTION.

In treating of the diseases of dogs and cats, we do not propose to follow the beaten path hitherto adopted and slavishly copied, to the exclusion of all originality and introduction of modern pharmaceutical agents. Nearly all that has been written on dogs and cats may be briefly described as Youatt boiled down or Stonehenge plagiarised. These writers had a practical acquaintance with their subjects, and brought to bear upon them an amount of talent which has been aptly described by Carlyle as “an infinite capacity for taking pains,” but they had not the aids to diagnosis now in the hands of pathologists, nor were an army of scientists continually engaged in the laboratory and the dissecting-room poring over the microscope, or working out theories for the benefit of those who cannot themselves spend time in scientific investigation, however much inclination they may have in the direction of original research. The practitioner cannot keep up with the times unless he accepts the aid so freely offered by investigators. In the chapters we propose submitting to our readers we shall advocate the use of materia medica not found in any other work, but not, therefore, experimental, as we are advised by the most advanced veterinary authorities, whose maxim in therapeutics is to “prove all things, and hold fast to that which is good.”

Methods of treatment and theories of causation, etc., will not be despised, because time has not yet proved them, nor will the latest microbe be accepted without question as the cause of disease. In his inaugural address at the opening of the 1892-3 session of the Royal Veterinary College, Professor McFadyean said “The old order is going; the old practitioner who disguised his ignorance and never hesitated is making way for the new man who dares sometimes to say ‘I don’t know,’ but always attempts to understand his case. . . Modern pathology either rests its explanations upon solid facts or continues its researches until a sound bottom is found.” Progress in every other department with which pharmacists have to do has been very marked during the past few years, and the contrast is made the more unfavourable when animal medicine is compared to human. The messes we were called upon to dispense 20 or 30 years ago are fast disappearing, and more elegant preparations taking their place, yet black drinks and red drinks and cure-alls are still in vogue for animals whose increased value should make their treatment and medicines a concern of greater importance to the veterinary practitioner and pharmacist.

Chemists and druggists have not catered sufficiently well for the animal-owning public in the past, but have allowed, unqualified pushing dealers to gain access to the farmer and supply him at markets and fairs with what he does not want, when otherwise he would have bought what he was really in need of from the local druggist.

It is not too late for the intelligent chemist to supply the wants of those household animals, the dog and cat.

A dose of acid hydrocyanic, administered with fear and trembling, is as much as a good many men ever attain to in this direction, but it need not be so, and the public quickly learn to appreciate a man who can for a reasonable charge treat a sick dog or cat intelligently.

In making these remarks we wish it to be clearly understood that we in no way recommend our readers to compete with the properly qualified veterinary surgeon, but should such make an objection, we would respectfully remind the profession that diseases of anything but horses and cattle are treated with neglect at the veterinary colleges, and the majority of practitioners have little or no knowledge of dogs and cats.

THE DISEASES OF DOGS AND CATS AND THEIR TREATMENT.

By A Veterinary Surgeon.

EXTERIOR OP THE DOG AND CAT.

The skin of both these animals differs from that of other domesticated animals. Horses and cattle perspire profusely upon very slight provocation, but such is not the case with the animals now under consideration. The dog, who from compulsion or inclination takes violent exercise, does not break out into a sweat, but pants, as it is commonly called, and obtains relief from the rapid evaporation of the lips or flues. Pussy declines long continued and violent exertion altogether. In pursuing her prey, there is more of the wisdom of the serpent; and some catty folks go so far as to say she has the same power of fascination; however that may be, whether engaged in love, in sport, or in war, she never travels far, though she can go incredibly fast to the next tree or area railing, and she does not sweat either from fear or exhaustion. This is a fact that should be borne in mind in the treatment of skin diseases.

The thickness of the skin varies much on different parts of the body. It is thickest along the course of the spine, where are situated those larger and coarser hairs, which in both dog and cat become erect when the creature is angry or apprehensive of danger from another animal. Under the arms and thighs the skin is thinnest and the whole of the belly is covered with a thinner integument than the upper half of the animal. The skin of the tail is also thicker on the upper than under surface, and erectile hairs are found on the upper surface chiefly, as will be seen by careful examination of pussy’s caudal appendage just after an encounter with a dog.

Skin diseases are not so numerous in cats and dogs as in human beings, but a larger percentage of them suffer at some time or other of their lives. The commonest of all is

MANGE.

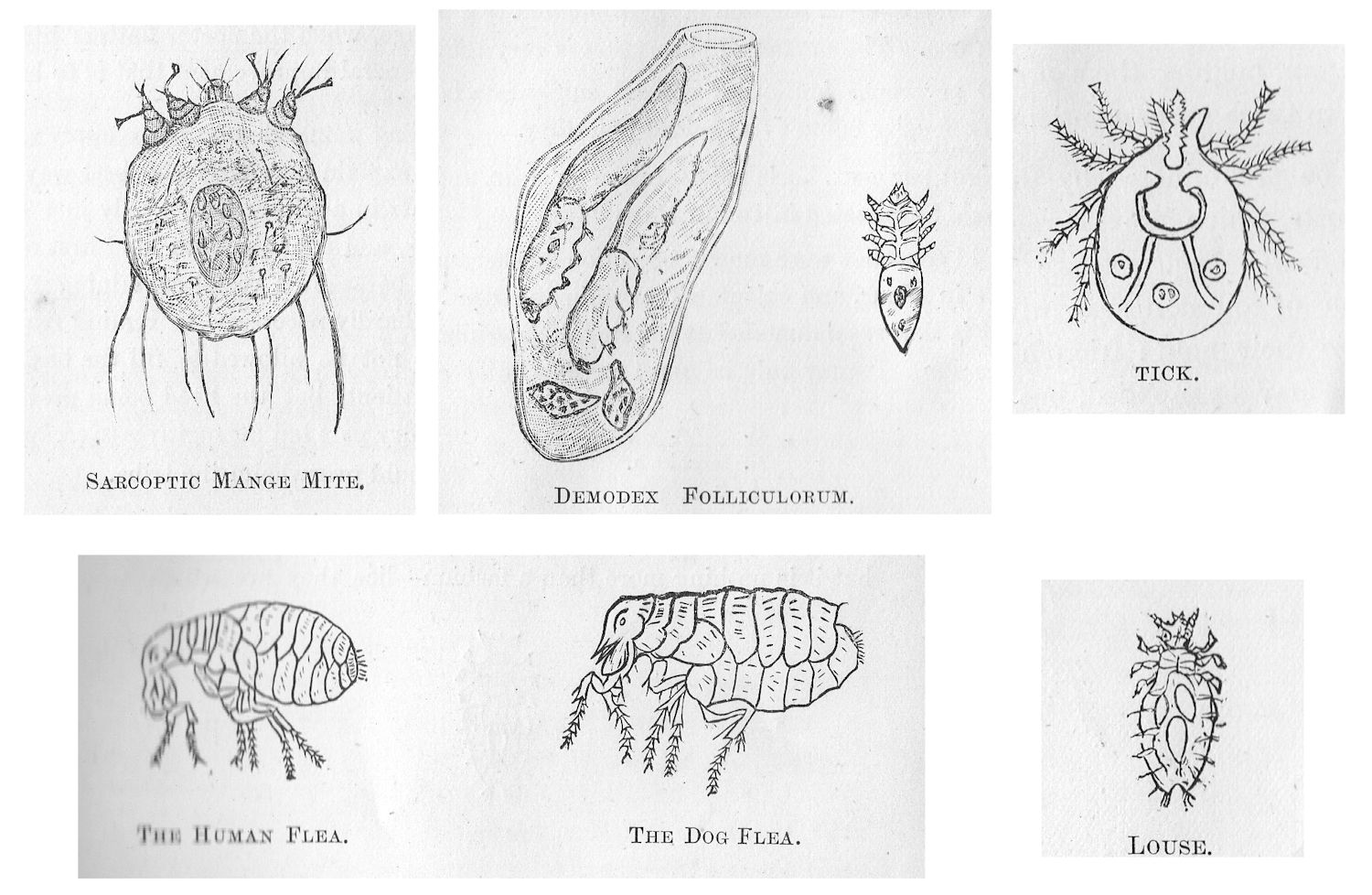

This term is applied by the general public to all sorts of skin diseases, and more particularly to one that is not mange at all, but eczema. True mange is of two varieties, sarcoptic and follicular.

Sarcoptic mange is caused by a parasite, analogous to the itch insect of man. Its scientific name is sarcoptis canis, and a similar parasite is the cause of scab in sheep, and mange in the horse. Sarcoptis catis, differing but slightly in form, causes the same diseased condition of the skin in the cat.

The sarcoptic mange mite feeds upon the serous discharge his presence produces, or perhaps we should be more correct in saying her presence, since it is only the female that burrows in the epidermis, while the lordly male waits the result. The activity of the male is chiefly conspicuous as a progenitor of

His evil race, and he may attain to grandfatherhood in a couple of days. Although this creature is said to have been correctly portrayed in engravings 200 years ago, we are still unable to pronounce with certainty, when a mange case is submitted to us, unless we use the simple and easy means of a magnifier.

It is only the work of a minute to scrape off the scales from a bad part, and mount on a slide with a drop of water or liq. potassae. You may be sure of capturing a male or two on the surface; and on the principle of every Jack having a Jill, you may be quite sure that the other sex is represented below the surface. To treat mange for eczema, and vice versa, is inexcusable now that everyone almost has some acquaintance with the microscope.

Suppose, then, that a case of sarcoptic mange is clearly diagnosed, how are we to cure it? By removing the cause, certainly; and to do it where it is of long standing we must, get rid of a lot of broken down material — scabs of serum and broken hairs and dirt and dead parasites and excreta.

An alkali that will cause the cuticle to swell up, and come away, can be readily found in soft soap, and the mistake too commonly made is to use too much soap and insufficient rinsing. After a bath of this kind, and when the animal is nearly dry, is the time to apply your external dressing, as the rubbish has been cleared away, and the skin is open to remedies that will kill the pregnant female, whose escape is the cause of recurrent mange, when the doctor flatters himself he has cured it by the general improvement that is to be seen.

As the foregoing remarks on mange apply to cats as well as dogs, we may explain here that the best way to give a cat a bath is to put her in a wicker basket only just big enough to accommodate her, and pour the bath fluid first over her head, and then dip the basket in a vessel containing the medicated bath fluid; it is hardly necessary to remind readers that the bath water must not be allowed to fill the basket to the top and drown the patient, but the head being previously wetted there will be no dry part left for fugitives to escape the general deluge which should overwhelm the tribe.

For a medicated bath for dog or cat suffering from sarcoptic mange, there is nothing better than an infusion of quassia with soft soap. A three per cent, solution of hyd. bichlor. is effective and clean in use. The danger of absorption is very remote. A 10 per cent, solution of potassa sulphurata is effectual, hut the offensive odour is a decided objection.

An eight per cent, boric acid solution is clean and reliable, but should be repeated in two or three days.

The old remedies were mostly objectionable because greasy, offensive in odour, and calculated to stain the coat. One of the best is that recommended at the Royal Veterinary College 20 years ago. It may only be used for dogs, and consists of

Ol. olivae.

Ol. terebinth.

Ol. picis, p. ae.

Two applications at three days’ interval are recommended. Whatever agent may be selected, it is well to finish the treatment with a bath of glycerine — one to 40 is sufficient.

FOLLICULAR MANGE

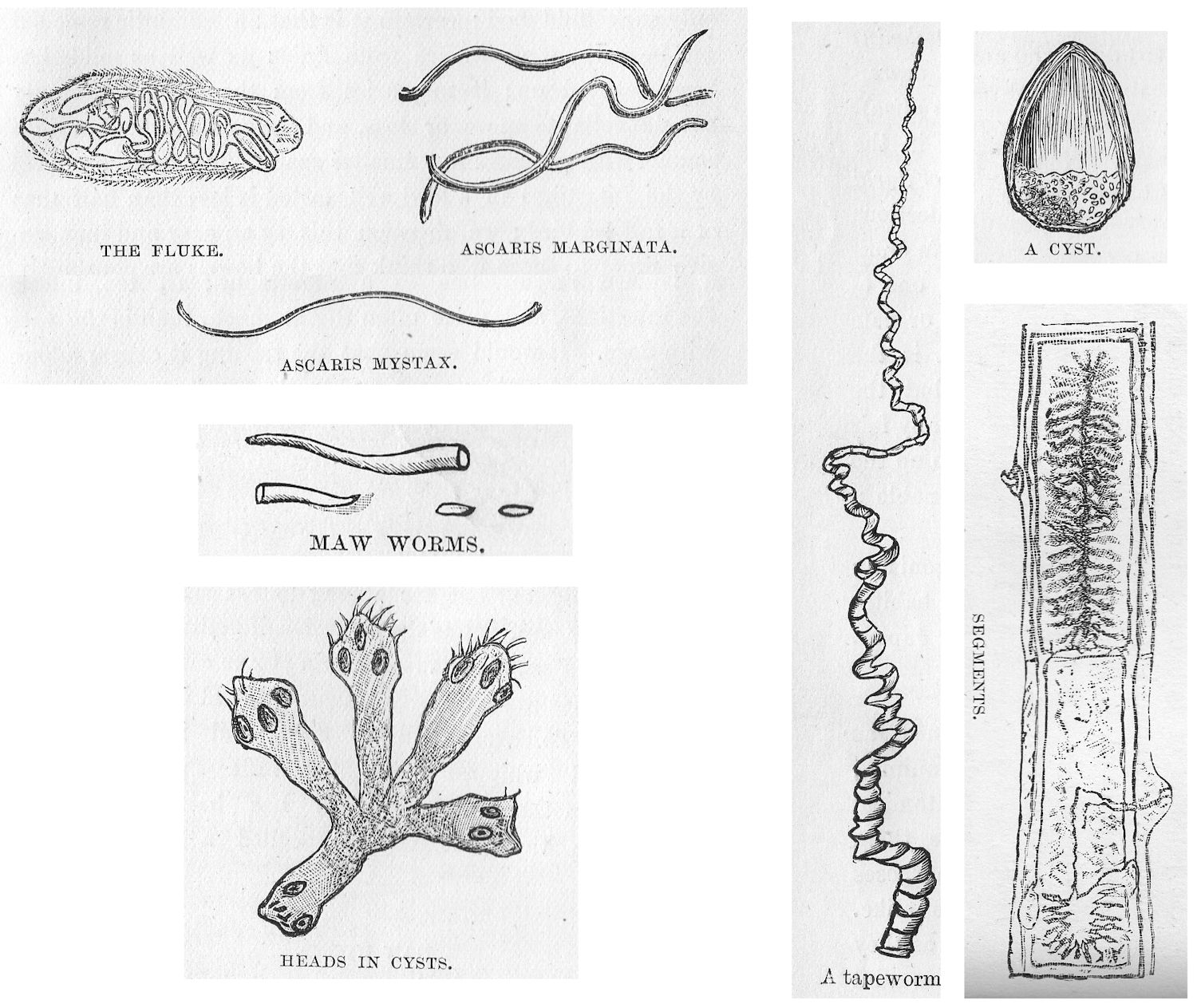

is also due to a parasite, but of a different order. Demodex folliculorum is its name, and its habitat those large glands of the skin in which the erectile hairs are rooted, and which we have elsewhere described as extending from the neck to the tail. It is not an insect proper, as it has eight legs, and belongs to the Arachnidae. It lives head downwards in the sebaceous follicles, and may be found with eggs in the same follicle. This disease is not so contagious as sarcoptic mange, and healthy dogs have been kept together with subjects affected for a long time without contracting it, while it may be readily taken by a dog rubbing his back on the staves of a chair where an infected animal has just before done the same thing and squeezed out one of the parasites. This form of mange is distinguished from sarcoptic by the slowness with which it progresses, the parts it affects, and the comparative absence of scratching and irritation. In sarcoptic, the thin and nude parts of the skin or else of the face and head are first affected, while the line of the spine is the first part besieged by the demodex folliculorum.

The microscope is not necessary to decide this form, though its use will prove interesting in comparing the parasites.

For treatment, what we have said of the other form of mange applies with double force to this. If it were necessary to remove effete material with thorough washing in sarcoptic mange it is absolutely indispensable in attempting to cure the variety under consideration, because it goes deep down into the follicles, and by its presence causes the production of an excess of sebaceous matter and detrita. To effectually deal with it the dog or cat should be clipped as close as a machine will do it, then soaked in oil for a night, next washed with an abundance of soft soap and water until the surface looks red and bare, when it should be well rubbed with an ointment of

Chrysophanic acid - gr. v.

Lanolin - ad oz i.

M. ft. ung., or hyd. bichlor. lotion 5 per cent.

A well-tried but nasty smelling application, first introduced by Professor Williams, of the New Veterinary College, Edinburgh, consists of

Ol. creasoti – 3 iv.

Liq. Potasssae – oz i.

Ol olivae - ad oz viij.

M. Ft. lotio. To be applied alternate days for a fortnight.

In bad cases of mange very great debility may accompany it, and cod liver oil in small doses be given either in a spoon or upon the food. Most dogs and some cats will eat it. That is, you may get dogs to take it with some favourite food, and cats with sardines. Physicking dogs is easy enough by simply making a funnel of their cheeks and pouring in a fluid medicine, holding up the head till a gurgle and a lick of the nose tells you it is gone down, but “the harmless, necessary cat” is so easily alarmed it is well to adopt her own methods of stratagem rather than force. Liquor arsenicalis in doses of fim one to five minims daily with the food often prove to be just the thing needed in these cases and adds a lustre to the new coat, not unknown to carters and others who use it as a substitute for “elbow grease.” It should not be used after the coat has began to grow in a healthy manner.

Arsenicum is prescribed by homoeopaths for this affection of the skin and may be given as globules or liquid.

Ung. hyd. viride, ung. sulph., ol picis et olivae, p.ae., are all good but greasy remedies, unfit for the household pet or lady's lap dog.

When prescribing for a kennel of hounds or sporting dogs these messes may be very well, or the now favourite remedy of paraffin 1 part to 8 or 4 parts of seed oil; but we have seen a few dogs killed by paraffin, and would in no case advise it for cats.

ECZEMA

is so commonly confused with mange, that a learned M.D., in writing for the instruction of the British public, describes it under one heading, and says it is caused either by parasites or impurity of the blood. It is doubtless an impurity of the blood that produces the eruption known as eczema, but if caused by a parasite, then it is not eczema, and this should be quite clearly understood by everyone who takes upon himself to doctor his own dog or anybody else’s. The microscope will settle it for him.

Those parts of the body which are comparatively free from hair are generally affected first. Redness and irritation is followed by little vesicles in clusters; these break and form sore patches or scabs, which by their presence seem to irritate the contiguous parts, and cause the invasion of what was before healthy skin. A variety of causes have been assigned by different observers, and it used to be attributed to an acid condition of the blood, to be combated by the administration of alkaline bicarbonates. A large measure of success attends such treatment in dogs and cats, but the most successful remedy internally administered is potassae tartras acida in doses of from 2 to 10 grains twice a day. Magnes. sulph. exsic. in like quantities has often proved a cure, especially with gross feeders.

The dose for a cat should be half the above quantities, and in both animals the powders must be administered by throwing them upon the tongue. A towel should be wound round the neck of the cat to prevent her striking out with the front feet, which is the only difficulty in giving powders to feline patients; they pretend to be very miserable for some time afterwards — great ropes of saliva hanging from the lips to the ground, but one need take no notice of it. Eczema is not infectious, and care must be taken not to mistake it for mange, where several dogs have contracted it; like causes having produced like results, and not parasitism. In prescribing for other folks’ dogs, one must disregard their statements as to the food. Nineteen out of twenty people who declare that their dogs have nothing but biscuits are quite mistaken, and a little cross-examination

will elicit that an occasional tit-bit is given, and further enquiry will probably enable the prescriber to ascertain that every member of the household feeds the dog without letting anyone else know it. Ladies are especially guilty of giving sugar and other things to their pets, and will assure the professional attendant that the patient has had nothing to eat for a couple of days, when its breathing is laboured by a loaded stomach.

A complete change of diet should be insisted on. One of the most fruitful sources of eczema in young dogs is the drinking of cows’ milk not previously scalded. Water is the drink for dogs, and it is a mistaken kindness to give them milk and tea, of which latter some become inordinately fond, and will take medicaments in it, while refusing them in all other vehicles.

Simple cases of eczema are generally to be cured with simple remedies, and if greasiness is no objection, an ointment of

Zinci. Ox - gr. v.

Ung. lanolini - ad oz j.

M. Ft. ung.

applied daily will allay the irritability quickly and facilitate the removal of scabs. For house pets and cats, who have no respect for cushions and hassocks, a lotion should be used of

R., Acid boracic - gr. v.

Glycerin. - drachm ss.

Aq. - ad oz i.

M. Ft. lotio, bis die applic.

There is, however, a chronic form of eczema, which is frequently called red-mange, but is not parasitic in origin. It is a much more serious affair than ordinary acute eczema. Beginning in the same way it goes on to an erysipelatous condition, and constitutional disturbance is so great that death often results.

Pustular patches and ulcerated areas may be seen on cases of long standing, and there is no difficulty in diagnosing it. The case has probably been aggravated by treatment as for mange, and after a course of paraffin and turpentine and other irritants, applied with the boldness that characterises gamekeepers and amateurs generally, it is no great pleasure to undertake the treatment of a dog rapidly declining in constitution. The first thing to be done with such a case is to wash the animal tenderly with curd or other neutral soap, and dry him with a soft Turkey towel, applying the following, lotion:

Acid hydrocyanic. - drachm i.

Glycerin. - oz. i.

Aq – ad Oi.

M. Ft. lotio.

This should be dabbed on and allowed to dry twice a day.

The diet must be nourishing, frequent doses of beef tea or meat essence (no salt should be used); bread crumbs and boiled milk; eggs and farinaceous puddings, etc.; and for drugs, liq. arsenicalis, in doses of from 2 to 8 minims, twice a day. If hydrocyanic acid lotion does not allay the irritation, boracic acid or zinci. ox. or lap. calam. may be dusted on the sores, but we recommend the first named as having answered the purpose when others have failed. Lanolin made thin with other emollients can also be recommended. The bath may have to be repeated.

Chronic eczema in cats is not of frequent occurrence, and when it is met with is caused by suppressed sexual desires; caged cats of the fancy varieties, especially females, being the subjects. The treatment that suggests itself is a natural one or an operation, but if neither of these remedies commend themselves to the owner a course of saline medicines, as mag. sulph., is the next best thing, with a reduced dietary and plenty of grass to eat. Couch grass {Triticum repens) should be kept wherever dogs and cats have access. Town cats and dogs will eat it from a vessel if freshly gathered. It excites vomition, and in the case of cats enables them to get rid of maw worms (Ascaris mystax). It is probable that this salad has alterative properties also, as the most careful observers agree in attributing to it curative powers, and have fresh supplies daily in their hospitals.

ERYTHEMA.

Erythema is a redness of the skin accompanied by irritability and swelling, but does not produce vesicles as in eczema, or pustules as in the various pocks. In dogs and cats it is most often met with in the winter, especially where salt has been used to sprinkle the roads. Snow will cause it without the presence of salt. Frosted grass coming in contact with the belly may often account for erythema. Considerable constitutional disturbance accompanies it at times — loss of

appetite, increased temperature and tenderness on pressure, restlessness and bad dreams.

It is very amenable to treatment, a saline dose or two, as pot. bicarb, gr. iij. to gr. x., or the acid tartrate of

potash will be found excellent treatment unless constipation is sufficiently marked to require an aperient, in which case a dose of cascara sagrada, m. 5 to 20 (liquor), or tinct. jalapae m. 2 to 8, for a cat or small dog.

Doses for St. Bernards, Great Danes, mastiffs and suchlike breeds may be calculated on the human scale, except with those drugs like aloes, of which a small dog can take as much as a man. Special notice will be taken of the peculiarities of our patients as to their being refractory to particular medicines.

To give immediate relief to the skin, evaporating agents may be recommended as

Ammon, chlorid. - drachm j.

Spt. Vini - drachm j.

Tinct. opii. – drachm i.

Aq. - ad oz ij.

M. Ft. lotio. It is essential to see that the bowels are open and exercise insisted on.

RINGWORM

in dogs and cats is of two kinds, each having for its cause a vegetable parasite. The commonest form is that produced by the Tricophyton tonsurans. It is not only contagious as between one dog and another, but from animals to man and man to animals. It is not frequent in dogs and cats, not to anything like the extent it is with cattle, and this is fortunate for the owners of pet dogs and cats whose children would be in constant danger from fondling these creatures. Few of our readers but can call to mind some obstinate case of ringworm in the human subject, and that perhaps among farm hands who have contracted it from horned stock. Yet it is not at all difficult to cure in animals, and will even die out in some seasons without treatment at all.

The distinct ring from which this affection of the skin derives its name makes it unnecessary here to describe it with exactness. Those who would have a scientific knowledge may scrape and mount a specimen in the usual way for the microscope, and ascertain with certainty for themselves if the outward character of the sore leaves any doubt in the mind of the prescriber.

Dirty and insanitary conditions favour its propagation, and its progress is rapid among the ill-fed and weakly of all species. When debility accompanies ringworm, mineral tonics should have the preference. One to 10 grains of ferri. carb. sacch., or ferri. sulph. 1 to 5 grains, or ferri. iodid. half to 8 grains.

For outward application tinct. iodi. daily until the edges begin to be raised. After this a bath and a dressing of ung. lanolini. Ung. hyd. biniod. 1 in 10 is an effectual dressing, but must be rubbed in thoroughly and the surface wiped clean with a soft rag, as dogs and cats are always liable to lick off dressings, and do not desist because a thing is nasty. Chrysophanic acid, again, is a reliable remedy. The old ung.

sulph. answers in many mild cases, but is not so trustworthy as either of the before-mentioned ointments.

Favus (Achorean Schonleinii or Favus tinea favosa) is very rare in dogs. It has a peculiar smell, which has been compared to the urine of the male cat. Mice being the most frequent subjects it necessarily follows that, of the domesticated animals, cats are the most liable, and it affects the front paws. When dogs get it it is about the face and head — the two animals seizing or holding their prey in such a manner as to communicate to those parts mentioned.

Treatment must be preliminated by thorough washing to remove the thick crusts, which prevent remedial agents from having immediate effect. Liq. potassae painted on with a brush or a solution of common soda will make the scales swell up and let go their hold; friction with a bone knife or wooden spatula may be applied, but great care should be taken to avoid fingering these places as the most serious cases in men have been brought about in the curing of animals. The spots should on no account be made to bleed; better to apply several dressings than run the risk of contagion through impatience. Glacial acetic acid applied with a camel’s hair pencil or a 5 per cent, solution of hyd. bichlor. repeated for several days have proved destructive of the fungus, but considerable time is required to repair the damaged skin. The iodides are good remedies, but given a well-washed skin with an alkali, the corrosive sublimate lotion is likely to effect the speediest cure.

TICKS

cause a deal of pain and irritation to dogs as well as cats.

They are peculiar to certain districts and almost unknown in others. Besides the dog tick, those large ticks found upon sheep and deer will also fasten upon dogs, sawing through the skin with a powerful apparatus provided for the purpose and distending themselves with blood.

They are very difficult to destroy, and hand picking is the best treatment, though a tedious plan, especially in thick- coated, long-haired dogs and cats.

Mercurial preparations destroy them, but should be used with caution. White precipitate, rubbed smooth and dusted over the animal, brushing the hair backwards, has been found to answer well, but brushing it out again should be thoroughly performed, and for safety, a muzzle should be employed between the time of dusting on and brushing out again.

If a bath can be used, the season, etc., being suitable, it should consist of soft soap with an excess of alkali, either soda or potash being used. Dry powders are to be preferred as alkaline washes destroy the natural secretion and dry up the skin, and if the hair is white naturally, a yellowness follows, although it may be remedied to the eye by a judicious use of the blue bag.

Borax leaves the least effect upon the hair, and should be selected for Maltese and white poodles, cats, etc.

FLEAS

In some seasons, among dogs and cats, whose toilet is not a constant concern with owners, cause a great deal of trouble; not content to run over the body with that irritating agility known only too well to our readers, they form nests or colonies from the nape of the neck to the root of the tail, and many a fair owner takes such cases to the veterinary surgeon under the impression that the animal has mange. Parting the hair backwards will discover the excreta in large quantities, together with other debris, while the enemy may be seen retreating in all directions on being disturbed. They are easily enough destroyed by washing with infus. quassiae and sapo mollis, or any of the dog soaps in vogue, and the only thing necessary is to begin by wetting the face and head.

For delicate dogs and refractory cats, Persian powder may be used, but it makes the creatures look very bad afterwards, and is not nearly so effectual as washing.

LICE

are to be found in nearly every dog of the fashionable poodle family. The lady owners insist upon calling them “ticks,” but it is nothing more than a fashion — lice they are whether called “by any other name” or not. Their method of propagation makes it necessary to give three baths at two days’ interval to get rid of them effectually, and yet at every fresh dipping these dogs are found to be infested again, with very few exceptions. Fortunately for the owners these parasites have no inclination to change their hosts, or poodles would not remain fashionable, despite their superior intelligence and aptitude for tricks. [Note: this was probably due to poodles often having “corded coats” rather than trimmed coats.]

The same remedies will destroy them that have been recommended for ticks and fleas.

WARTS, SCURF AND EXCRESCENCES.

Having spoken of the commonest skin diseases in dogs and cats, we will just glance at those occasional conditions that make one ashamed of his dog instead of that feeling of pride in a well-kept and properly-trained animal to which very few people are strangers. Some dogs, but very rarely cats, have what one might call a warty diathesis — they come and go - and there is more come than go about them in some cases, hut no reason can be given, though generalisations have been attempted by authors of medical works who are not yet able to explain why charms and incantations remove them. It is admitted by the talented author of "Minor Ailments” that “they have a close relationship to the nervous system.” So did our grandmothers believe, in their vague way, but this does not seem to account for animals losing their warts between the time of noticing them and getting the remedy. For those warts which do not thus disappear we recommend removal. There are two principal kinds of warts met with in dogs and requiring quite different treatment. The one resembling human warts are proliferation m of the papillae, cauliflower-like in composition, but divided and examined microscopically they consist of squamous epithelium piled up in heaps and twisted into all sorts of shapes. When allowed to grow large they gradually grow an artery of supply and nerve tissue as well, so that removal is extremely painful. The best method of removal is to take a pair of close pointed tooth forceps, such as are used for upper stumps, and having secured the wart, destroy it by strangulation, a slow but continued twisting round and round, so as to break the vessel of supply, and afford a natural plug to prevent haemorrhage. The blood from a wart is credited with the power of producing others in its course, but it is a popular delusion. The same idiosyncrasy, or constitutional tendency, that produced one wart is liable to produce another, and not the blood stream from a benign growth.

A touch of liquor ferri perchlor, or collodion, hyd. Bichlor, acid tannic, acid gallic or other styptic will generally suffice to arrest haemorrhage, and the cicatrisation of the part will so quickly follow as to make it difficult to trace the operation after a few days.

To those persons who will not consent to remove warts in this way, we would say before applying any caustic, take care that the wart is thoroughly softened with hot water, as one application of caustic will then have more effect than three on a dry surface.

Nitrate of silver is expensive and unsightly, and in the hands of amateurs too frequently remains on their hands as well as on the warts. Hyd. sulph. flav. is little known, but a most reliable agent for the purpose. Chloride of zinc is probably the best of all caustics, and will remove an excrescence in a shorter time than any other agent.

Ligaturing is, of course, a good plan, but warts with a spreading base in the hairy patients we are considering are difficult to get at and secure. If ligaturing is decided on, it should be done with the strongest of thread, wetted and tied in a “doctor’s knot.”

Encysted warts cannot be removed by external remedies, but must be laid open with a keen knife. They are frequent on the bellies of dogs and occasionally on the head, spine, and other parts. They are composed of a fibro-cartilaginous material enclosed in a cyst or sac, and when cut down upon boldly, jump out as if glad to be released. Sometimes the serosity in which they are nourished is considerable in quantity, and makes them look much more serious than they really are. No after treatment is required.

Besides warts and other excrescences above the level of the skin, there is a bran-like scurf, a dandriff it might be called in man, that makes some dogs and cats too, life-long subjects of disappointment to their owners. A dry, unthrifty skin that is always peeling and is frequently an outward manifestation of chronic indigestion, or something even worse.

In attempting to treat this condition which has been described as ptyriasis, care should be taken to ascertain the history of the case. A dog that has been dressed with paraffin for mange will be covered with desquamating epithelium, which may easily be mistaken for the disease under consideration.

It is associated with, if not caused by, oxalates in the blood, mid generous diet and exercise is the best treatment, unless worms are the origin, and in that case they must be expelled before any treatment can avail. If the ordinary urine examination shows oxalates — calcium oxalate usually — then lithia should be given in doses of 2 grs. to 10 grs. of the carbonate, or a like quantity of sodae salicyl., or homoeopathic doses of arsenicum or sulphur.

LOSS OF COAT.

As in the case of men and women losing their hair without ordinary causes to account for it, so do show dogs and cats often begin to moult just before a show, to the great chagrin of the would-be exhibitor. Besides the ordinary coat shedding or moulting in spring and autumn, bitches and she-cats moult after giving birth to young; about the time of weaning it is most noticeable, and for this natural process there is no remedy, and should be no objection. The loss of coat at other times is annoying, but generally traceable to unnatural conditions.

Long-haired dogs and cats seem to have been originally provided with such coatings for the sake of warmth, and when a long-coated collie is crossed with a Gordon setter to produce a golden tan, and then kept warm and pampered indoors, nature sets about adjusting the clothing to the circumstances by thinning out the coat.

The remedy then is exposure to cold, friction to the skin, hard brushing, exercise and poorer fare. The process that makes the hair remain on a dead skin has much the same effect on a live one, and a strong solution of alum exsiccat will often make it hold till a show is over for which the dog may have been entered and fees paid. No artificial remedies will avail except for temporary purposes, and hygiene must rule.

THE EAR.

The skin upon the outside of the ear is very thin, and the hair short and soft. The inside is but a reflection of skin, though provided with special glands not found in other parts. Sebaceous and ceruminous glands are provided to keep supple and to supply with wax the meatus. It should be remembered that animals have the power of moving the ears, and that very constantly. There is much expression in the ears of both dogs and cats, and to facilitate these movements these sebaceous follicles or glands, as they are variously called, produce just sufficient unctuous material to render them soft and pliant, while the ceruminous glands supply wax for the same reasons as in man. Interference with the function of these glands is the origin of

CANKER.

Heredity has much to account for in cankered ears, some families being prone to it, and some breeds more than others, while no breed can be said to be immune. Water-dogs have always been considered most liable to canker, but if a hundred poodles and a hundred water-spaniels were taken at random it is a question whether the poodles would not show a larger percentage of bad ears.

Because canker has an offensive smell, like the disease known by the same name in horses’ feet, it was treated on wrong principles by the same men who understood the nature of the fungoid growth in horses. It is not a fungus in the dog or cat requiring caustic remedies, but has its origin in inflammation of the lining of the ear in which the glands before mentioned become involved, and instead of secreting a soft emollient material they pour out an offensive irritating matter, which inflames and ulcerates the surrounding parts.

The treatment consists in removing the cause, and this is best done by pouring into the affected ear a little warm oil — ol. amygd. dulc. for preference as being thin and free from extractive - and gently manipulating the base of the ear to break down the concretions of wax, dirt, dead hairs and diseased products. This should be repeated for two or three nights, when it may be cleaned out with warm water and neutral soap; then carefully dried with cotton wool twisted round the end of a bone penholder, taking care not to bruise the tender tissues. This done, a lotion as follows will be found to answer well:

Acid boracic - 10 grs.

Zinci. Oxyd - drachm ss.

Gllycerin - drachm iv.

Aq - ad oz. iij

M. Ft. lotio. Nocte maneque utendum.

The practice of using strong solutions of or ointments containing sulphate of zinc, copper, etc., etc., cannot be too strongly condemned as both useless and barbarous.

Where an ointment is preferred, lanolin may be combined with the above remedies, or with half a drachm of emulsified creasote to the ounce.

Another good ointment is:

Camphorae - drachm ss.

Pot. Nit - gr. x.

Lap. calam. – drachm ss.

Adip. vel vaselini - ad. oz. j.

M. Ft. ung.

Canker of the ear is confused in the minds of many persons with an abscess in the flap of the ear, between the skin lining it and the cartilage which gives it stiffening. After fights or other injuries, such as hunting thick hedgerows, the ear is observed to be hot, painful and swollen, and closer examination shows that a fluid has accumulated in the part above described. If allowed to remain it increases in size, but does not point and break like an abscess containing pus. The pressure of the fluid within arrests the circulation, and the ear withers away, ruining the dog’s or cat’s appearance for life; cats are almost as liable as dogs to this affection of the ear, but true canker is less frequent in the cat.

For treatment there is nothing but bold surgery; it is no use to prick it; however carefully the fluid be evacuated, it will refill in a single night, and each time with a fluid of greater density. The skin on the inside of the ear must be boldly lanced from top to bottom of the swelling, and to prevent the rapid re-union and refilling, a pledget of tow, cotton-wool or other material inserted to prevent union. If the case is already two or three days’ old before treatment is attempted there will be found a membrane lining the cavity, and this should be removed mechanically, and the wound dressed with either of the following:

R Acid carbolic – drachm i.

Glycerin – drach i.

Aq. camph. – ad oz. i.

M. Ft. lotio.

R Resina pulv.

Pot. nit

Magnes. carb. pond. p. ae

Ointments are difficult to keep on the wound, and if the above lotion be selected it should be used frequently. If the case is not within easy access it will be better to use the powder, as once a day is sufficient. Not to heal but to hinder the reparative process is the method of treatment productive of the best results.

Injuries to the cartilage are quite another matter. The skin is disposed to repair itself too quickly, while cartilage has in it no disposition to renew or replace lost structure with new material. Dogs with pendulous ears, of which the bloodhound may be taken as representative, get ulcerated tips to the ears through violently shaking the head. The shaking is caused by canker and the ulcers by the shaking, hence the confusion that has arisen and the origin of the term external canker. Ulcerated cartilage must be excised with as much regard to appearances as each individual case will permit; the new edge may or may not heal up. Styptics, of the collodion type, are the best. A preparation composed of collodion and tannic acid, answers well. The difficulty in this and many other diseases of the smaller animals is to prevent them from doing injury to the parts when absolute rest is required. Canker caps and various other contrivances have been tried, but anything that confines the offensive odour reacts upon the ears, and exposure is in the opinion of most authorities the best. If the ear is confined in a cap or bandage because of an ulcerated tip, the probability is the dog will rub his head along the wall till he gets any sort of appliance off, and then the last state of that dog is worse than the first. Among the minor ailments of dogs, cats and monkeys, there is nothing more troublesome to treat than sore ears and tails.

SORE FEET.

Apart from the many pricks and wounds from thorns, broken bottles and sharp flints, the feet of dogs especially are liable to become sore; following a carriage, or after a long day’s work, the pads are found to be worn away, and the sensitive structure rendered hot and painful with the bruising that has succeeded when the natural horny skin has been worn away.

For this soreness, fomentations, poultices, and rest are essential, but the sporting dog may be got to work a day or two sooner if his feet be soaked in a solution of alum or boracic acid, or painted with tinct. myrrh, co.

A distinctly different kind of lameness is produced by the sore feet of winter when in towns the roads are salted to thaw the frozen paths. This is not wearing away of the pad, but chaps and cracks chiefly between the toes, where the skin is thin and readily inflamed. Treatment with a 10 per cent, solution of salicy. soda is recommended for house dogs, and for sporting and country dogs generally, ung. boracis or lanolin, or washing with an acidulated lotion (5 per cent. acid hydrochlor. dil.), and after careful drying to dust between the digits with pulv. amyli, 1 pt.; pulv. zinci. ox., 1 pt. Cases of long standing, or those neglected at first, will require, in addition to careful cleansing with warm water and soap, to have a mildly caustic application to induce a healthy action in the cracks that gape open and cause great pain, besides being receptacles for grit and dust.

Sore feet of yet another kind are quite as common, and at all seasons of the year. The sores are between the digits and caused by an eruption of vesicles, which, for want of a better name, will continue to be called eczema. The pampered pet is the most frequent subject; the same dog that is lame from overgrown nails will often be lame from this eruption. Saline aperients and topical remedies, as recommended for eczema, will generally bring about a cure.

DISEASED AND BROKEN NAILS

are generally, but not always, the result of neglect. The sporting dog gets sore nails, especially those known as dew- claws, from the wet or frosted grass getting between the claw and the leg. Many good sportsmen have them removed while the pups are quite young, but their absence in some breeds would disqualify the dog for the show bench. If a painful dew-claw will not yield to fomentation and poultices it bad better be cut out. It is not a difficult operation, and two or three days suffices to heal up the wound. The rule to be observed in operating is to hold the claw as clear of the leg as possible, and to take away the minimum amount of skin. Bind up the wound with a pad of carbolised oil (1 in 20 to 25), and over it a light bandage, taking care not to tie it tight; a few stitches are always preferable to tape or string, which has a knack of getting tight and causing the foot to swell. The pain and lameness of a dew-claw in lap dogs is often caused by the nail having grown in a circle and pierced the pad; the obvious remedy is to cut it short. It should be borne in mind that nails, like horns, grow a vascular inside, and a long nail cut short will bleed considerably. If the owner has sufficient patience to keep cutting back the nail a little at a time, it may eventually be reduced to reasonable proportions without bleeding. The probability is that the person so careless as to let it grow long enough to lame the dog will not be thoughtful enough to give the necessary attention to reduce a nail by degrees. To stop haemorrhage of the cut nail, a touch or two with a hardened caustic point is sufficient; any other styptic will do, as liq. ferri. perchlor, zinci chlor., cupri. sulph., etc.

There is a disease, coronitis it may be called, affecting the secreting band of the nails of the foot proper. It is very troublesome to treat, but poulticing first and varnishing with a thin paper varnish when dry, has been found to answer when more scientific treatment has failed. In speaking of sore feet and nail diseases, we have made but small reference to cats, because they pick their way so daintily over bad roads that they seldom suffer as do dogs. True it is that no weather will hinder pussy from going out, but she walks warily, and uses the same old footprints in the snow time after time. Cats’ nails sometimes split, and should be cut and filed. Some cats of the “third sex,” [note: neuter] who never go out of doors, suffer from overgrown and ingrown nails, and must be treated in the same way as dogs.

THE EYE AND ITS APPENDAGES.

The chief anatomical difference in the eye of the dog and of man is the presence of a large retractor muscle at the back; and in the front, or rather the inner corner, instead of that little body known as the caruncula lachrymalis, will be found a somewhat dense membrane, called variously cartilago nictitans and membrana nictitans; either name is applicable since a portion of it is membranous, while the remainder is of denser material, like cartilage. When the lids are open and the retractor muscle at rest, not much of this membrane is to be seen, but on the entry of a fly or other foreign body, the muscle draws back the globe of the eye upon the cushion of fat behind it, and the membrane sweeps the eye to clear away the intruder. The human hand being capable of removing foreign bodies, this caruncula lachrymalis is sufficient for our purposes, though in London fogs one may be forgiven for envying the cat whose membrana nictitans is even more developed than in dogs, and only equalled in birds.

There is another difference, and that more conspicuous in the cat than the dog — we refer to the tapetum lucidum or bright carpet. The retina of the night marauding feline tribe is specially luminous, enabling them to see in a very poor light — not in absolute darkness, as many may suppose. It may be observed that most animals see better in the dark than man. Who shall say that savage man did not once possess a tapetum lucidum, which has disappeared with the advent of candle makers? It is not our province to discuss this subject, but it is a notable fact that defective sight and increased artificial lights have characterised the last half of the century.

Injuries to the eye, the lids, the haw, etc., are common enough with dogs, but not so frequent with cats; the latter are often the cause of injured eyes in dogs.

Torn eyelids should be brought together by very fine sutures and a wet pad bandaged over that side of the face. Keeping it on is not always an easy matter, but to prevent a dog from injuring himself by rubbing or scratching with front paws, or from biting his legs or any part of the body, a simple contrivance may be made by securing a stout piece of millboard or floor-cloth and cutting it round according to the size of the dog; for a small dog it need be 10 ins. or 12 ins. in diameter. Having ascertained the exact size of his neck, a hole should be cut in the centre and then slit through from the centre to the circumference, in order to get it on the dog’s neck. To secure it there, holes should be punched, and a leather boot-lace passed through them. This Elizabethan frill answers many purposes, and must be so wide that the patient cannot get his mouth beyond the edge. To induce a torn eyelid to heal, it is essential to bring the edges into apposition and to secure for them rest. When these conditions can be obtained — always a difficulty with animals — a fairly good mend may be expected, but a large proportion leave a tongued process, and always a blemish for life.

The haw (membrana nictitans) is subject to inflammation, swelling, and ulceration, and in bulldogs and some other breeds there is a predisposition to the formation of little cartilaginous tumours.

Cocaine is a most valuable remedy, as it reduces the sensibility, and enables one to make a careful examination for foreign bodies or the application of caustic agents. A 2 per cent. lotion should be dropped in a minute before attempting to handle the lids.

An increased display of the haw in cats must not be mistaken for disease of that structure, but is a common symptom of debility. In almost any illness a cat or a bird will show more of the haw than in health. In acute inflammation of the eye a darkened room should be chosen, both for the rest of the eye and the inclination the patient feels to sleep and get through time when there is nothing to occupy his attention.

OPHTHALMIA

is a term applied to any inflammation of the eye, but to treat dogs and cats successfully one should be able to distinguish between a superficial inflammation (conjunctivitis) and deep-seated forms, which are producing changes of structure.

All ordinary inflamed eye from external violence, dust, draughts, etc., should be treated topically with fomentations of warm milk; low diet, and an aperient dose. There is no necessity when giving an aperient to choose the stickiest and most unpleasant to administer; the favourite old remedy of castor oil and syrup of buckthorn may surely be so classed. Aloes in very uncertain, and produces so much nausea as to be generally lost. Pulv. glycyrrhizae may be given in gravy or or other food; cascara sagrada is efficient without being sticky or greasy, while mag. sulph. and pulv. sacch. may be thrown

On the tongue, and taken up in the saliva easily enough. We have elsewhere recommended mag. sulph. exsic., because

The bulk is much reduced, but it has the additional advantage that when given as a powder it cannot be thrown out of the mouth by shaking the head, whereas the crystals can be so got rid of.

In simple ophthalmia one or both eyes will be closed, and highly sensitive to light — tears provoked at the thought of an examination. On opening the lids the vessels will be very red and distendd, but all the fluids discharged will consist of tears and not matter.

In periodic, constitutional, or deep-seated inflammation, the symptoms are not so acute as a rule. It is more gradual in its invasion, a weakness of the eyes, and a grumous or puslike discharge not large in quantity, and with a tendency to adherence of the lids is marked. Not so much objection is made to an examination, and the membrane will be found generally suffused with redness of a brick-like colour instead of the bright red of acute inflammation with its well defined vessels. If a view can be obtained of the inner structures a cloudiness or orange-tinted yellowness may be detected. To get a good view a little atropine should be dropped in, and five minutes afterwards cocaine, as by the one dilation of the pupil is produced, and by the other diminished sensibility to handling.

Constitutional remedies are required for this form of ophthalmia, and the iodides have long had credit as curative agents.

After an aperient dose, potassas iodidi, gr. i. to v. bis. die., and applied to the lids with care, ung. liyd. nit. mit. alternate days. The meibomian glands which line the edges of the lids should in health secrete just so much unctuous material as to prevent the overflow of tears, but when these are involved in the general inflammation they produce an irritating matter that causes the lids to stick together, and confine the matter upon the surface of the eye, the presence of which is so irritating as to produce ulceration of the cornea.

Ulceration of the cornea is not a frequent result of traumatic or of constitutional ophthalmia, but is a sequel to distemper, and will be again referred to when treating of that malady. Cats of the common breed are not often the subjects of the above, but the fashionable long-haired cats, of which some 500 are exhibited at the Crystal Palace annually, are much more delicate and occasionally troubled with entropium and ectropium, which, in plain English, is turning in or turning out of the eye lashes. Dogs of the bloodhound and King Charles spaniel class are also the subjects of this uncomfortable and disfiguring departure from normal conditions. It is not always easy to induce cats to hold still while a bend in the opposite direction is given to the hair by a pair of forceps, or while manipulation of the lids is going on; the perverse hair or hairs must be somehow induced to follow the proper course or else be removed, since their presence produces inflammation, and in time opacity of the cornea; tears also run down the face, scalding the skin and causing a veritable eye sore. These eye sores are also caused by occlusion of the lachrymal duct, which, may be a consequence of distemper or congenital in some breeds. All the snub-nosed dogs, as bull dogs, King Charles and Blenheim spaniels, pugs, etc., are prone to tear-stained faces.

Little sebaceous tumours upon the margin of the lids or fibrous tumours upon the haw, if interfering to any extent with the surface of the eye, must be removed under the influence of cocaine. The tumour should be secured by a needle and thread passed through it, holding it away from the eye, and with a sharp knife or scalpel, always cutting in a direction outwards. Very little after treatment is required. If any amount of irritation is produced it should be treated as ordinary inflammation with warm milk or water fomentations.

Puncture of the eye-ball by a cat’s nail or other cause may cause the escape of the aqueous humour. It cannot be brought together by sutures, as the remedy would be as bad as the disease. It is a remarkable fact that if rest can be obtained for the injured member that repair takes place and a fresh supply of aqueous humour is secreted. Advantage is taken of this in removing from the eyes of horses a filaria, which in some climates finds its habitat in the aqueous humour and swims about in it. Perfect rest, a wet pad with a soothing lotion of liq. plumbi, or an aqueous preparation of opium and belladonna alternately is to be advised. If the anterior chamber is not evacuated by too large and ragged a rent, and repair does take place, there will as certainly be an opaque line left on the cornea, after every means has been adopted, to cause absorption of superfluous material. These opacities of the cornea are confused in the public mind with

CATARACT,

which is an opacity of the lens, either the substance or the capsule, and called lenticular or capsular.

There may be cases in which the one or the other are alone affected, but in everyday practice we generally find both together. It is only in books that diseases fit exactly into the squares made for them; it would be more convenient to the student, as well as the practitioner, if they would follow a definite course and attack one structure at a time.

The removal of cataract is not practicable, as dogs and cats cannot be trained to use spectacles.

More frequent than cataract is a change in the vitreous humour. Nearly all dogs and cats which live to be very old have dim vision from this cause. This humour, which is so named from its resemblance to molten glass, becomes foggy, a yellowish cloud settles upon it, and becomes denser and denser as extreme old age is reached. No rejuvenating process has yet been discovered by which this can be averted. If it occurs in dogs and cats as a result of debilitating diseases, iodide of iron in small doses, one eighth to 2 grains daily for a long time, may do much to cause its absorption. With the return of vigorous health it becomes clear again.

AMAUROSIS

Is the name given to paralysis of the optic nerve. The eye is clear and bright, and the tyro easily deceived in purchasing an animal with this grave defect. Fortunately, it is not very common. The subject of it is worthless and incurable. Total blindness is the usual result.

IRITIS

Is inflammation of the iris, that movable curtain which gives colour to the eye. It is composed of two orders of muscular fibre, the radiating and the circular, and by the contraction of the former the pupillary opening is enlarged, and by the latter diminished. It is an involuntary muscle, and the size of the pupil depends upon the degree of stimulation of the light. The cat is the best subject for examination. Her pupil dilated at night in a low medium of light shows the tapetum lucidum before referred to, while it shrinks to the size of a pin’s head when she lies basking in the sun.

When inflammation of this structure takes place, bands of lymph form and arrest the muscular contractions which regulate the pupil. It is not so frequently met with in dogs and cats as in horses, and not so often in them as in man. Rheumatic and syphilitic sequelae appear to account for its greater frequency in man. When it occurs in animals, bleeding from the eye-vein is recommended, and a course of mercury, with aperients and a generous diet, fresh air and exercise, and a room from which direct sunlight is excluded, Salicine and its preparations have an absorbent effect, even more so than the iodides which were until recently in great favour. The dose for a dog or cat is from 2 to 8 grains of sodae salycilas daily.

Iritis seldom exists by itself in cats and dogs, but the iris becomes involved in the inflammatory processes that are associated with distemper.

DISPLACEMENT OF THE EYE-BALL

is not such a rare accident as one might imagine, and we have known it happen to a pug-dog in giving a dose of castor oil. A blow on the orbit is sometimes sufficient to produce it, and it is not confined to those prominent eyed dogs as pugs, Blenheims, and King Charles spaniels, but occasionally happens to long-faced animals, as greyhounds and the terrier class. It is a ghastly sight, that of a dog with his eye laying on his cheek, but not so hopeless a case as to forbid efforts to replace it. If quite recently done, no time should be lost in securing the dog and slitting the outer canthus or corner of the lids, and by gentle pressure with oiled fingers endeavouring to replace the globe. It has often been done and should certainly be attempted, since extirpation can be effected when return has failed. A pug was once taken to a West End doctor to have his teeth scaled, and while struggling to evade the operation his eye came out, and was replaced so rapidly that he went home with his mistress, who brought him back two days later “because he had a cold in one eye” which she attributed to a draught under the door; no greater damage than a slight inflammation resulted. In treating a dislocated eye-ball, the first thing to be done is, of course, to replace it, next a wet compress — belladonna or opium, or liq. plumbi, lotions, as elsewhere advised.

For the treatment of other injuries. Even if the sight is lost it is better to retain the eye than to extirpate it, since the cavity left is so unsightly, and the division of the optic nerve, whose fibres cross its fellow of the opposite side, causes a predisposition to failure of the remaining eye. If there is no choice but removal the ordinary treatment for wounds is to be adopted.

HAIR ON THE SURFACE OF THE EYE

is a curious disfigurement occasionally met with in dogs, and less rarely in horned cattle. A little warty substance of yellowish tint grows upon the cornea, and from it distinct hairs spring up. There is no effectual treatment, but careful removal with a fine edged scalpel, first transfixing the body of it with a needle and thread; operations of this kind are almost impracticable without anaesthetics, and as they are easily and safely administered, we had better describe the methods than advise an operation so delicate to be undertaken by anyone without them.

ANAESTHETICS

have not hitherto been used as frequently as they should upon the lower animals, not even among advanced veterinarians, who are beginning to take shame to themselves for the unnecessary suffering of their patients. There are several reasons for this. We will not here consider why horses, cattle and other domesticated animals so seldom have the benefit of chloroform, our concern at present is with cats and dogs.

Dogs are notoriously bad subjects for chloroform, and the pretence of keeping a dog anaestheticised for two hours while vivisectional experiments have been performed is nothing more than a pretence. No dog will survive chloroform for two hours or for one, and very few will recover from complete anaesthesia so produced for ten minutes.

AEther is the only safe anaesthetic for dogs, and it should be administered by preparing a cardboard cone with open ends, and introducing sponge saturated with the fluid. The patient must, of course, be secured, as he will fight against the inspiration of any anaesthetic. Quick and deep inspirations should, if possible, be obtained, and insensibility is rapidly produced. There are dogs occasionally met with which cannot be quickly subdued with aether, and such subjects may have a fifth part of chloroform added with safety and success. As soon as the muscles are completely relaxed, the cone should be removed and no time lost in operating, as experience teaches that the more rapidly anaesthesia is produced the more rapidly is sensibility restored and the less the subsequent effects. Anaesthesia appears to be produced by the rapid deprivation of the blood from the nerve centres, the rebound being in proportion to the rapidity of the action. It was formerly insisted that safety was to be sought in a free admixture of air, but those who have had most experience of anaesthesia prefer to rush their subjects under and out again as quickly as possible. Of course there are cases — tedious operations for the removal of tumours, etc., with numerous small blood vessels to be picked up and secured, necessitating the continued insensibility of the patient; in such cases he had better have a few whiffs again.

The pulse can be, entirely disregarded, and only the respiration watched; the flank does not rise and fall with regular sequence throughout, but if interrupted for more than one inspiration the cone should be removed at once, and a flick of the ear given with the finger; this slight application will bring back signs of life, and the operator will soon learn to judge of the necessity for giving more or withdrawing the effects of his anaesthetic.

The A. AE. C. mixture, that is alcohol, aether and chloroform, so much liked for children, does not suit dogs or cats;

they do not readily succumb to it, and show signs of drunken headache, nausea, and loss of appetite afterwards.

Cats are of all subjects the best for anaesthesia; they take chloroform well and recover completely and rapidly. They cannot and need not be held in order to administer it. They should be put into a bag; the only precaution is not to “let the cat out of the bag” when introducing a sponge saturated with chloroform, or if for a long operation a fifth part of aether may be added. Cats go naturally, so to speak, into a bag, and should be sat into it, they do not like to go in head first. A Gladstone bag that will shut up quickly answers best, and no air need be admitted. After about 60 seconds the bag should be tilted, and if the tenant tries to right herself she has not had enough chloroform; if she is felt to fall over with the movement of the bag she should be quickly taken out. If no movement is felt the bag should be cautiously opened to see if she is sitting bewildered, or only waiting for an opportunity to escape. If after an operation under chloroform or aether a cat or dog does not quickly become conscious they should not be hurried, provided the respiration is at all steady; to come to gradually in fresh air is better than by artificial aids. If it is feared that the patient is too far gone, a cold douche to the head and ammonia sprinkled round will have a rousing effect. If a drop of cold water inside the ear causes shaking of the head there is not much to be feared. In bringing animals too quickly out of anaesthesia there is a danger of them hurting themselves while only half conscious,

and particular care should be exercised not to let them bite the sponge, as they cannot let go again; this also applies to the operator’s hands.

Before administering any anaesthetic the stomach should be empty, and in the case of abdominal operations the bowels also, or the straining to evacuate the rectum may produce very bad results.

From the diseases of the eyes and the anaesthetics to be used in operating upon them we pass down the face to the nose.

CRACKS AND ULCERATION OF THE NOSE

are generally caused by too much indulgence by the fireside, inducing at first dryness, then cracks, and finally obstinate ulcers, which take on a cancerous appearance and become incurable. Cats as well as dogs are subject to this malady, and from the same cause.

Treatment to be successful must be undertaken in a place removed from an open fire. The patient should be confined in a cage or on a chair, and the nose frequently anointed with cold cream, vaseline, lanoline, lard, fresh butter, or any similar emollient free from salt. Water is really the best remedy, but its application is the difficulty. It has been done by confining a wet swab inside a leather muzzle, but the patient is very impatient of its presence, and will remove it with front or hind feet unless the Elizabethan collar already mentioned is kept constantly on him.

Nasal troubles are not confined to the outside; hitherto we have been considering the exterior of the cat and dog — skin, ears, eyes, feet, etc. Beginning with the nostrils, we propose to consider the air passages and breathing apparatus, including those parasites and abnormal growths found within the nasal chambers and respiratory apparatus. The widespread teaching of anatomy under the name of animal physiology in our public and private schools permits us to assume, without suspicion of affectation, that the majority of our readers have at least a superficial acquaintance with the structure of the human body, and in asking them to apply that knowledge to quadrupeds we would only direct their attention to the chief differences. The modern schoolboy does not suppose that the heart swings like the pendulum of a clock in a cavity containing food, and impeded only in its action by excessive doses of plum-duff, in which it struggles for sufficient space to move. Nor does he believe that swallowing a piece of cotton will cause premature death by twining round his heart, as our grandmothers led us to believe. We remember the fallacies they taught, while forgetting their wholesome precepts.

POLYPUS AND SNUFFLES.

Polypus is a soft, fleshy tumour, growing within the nostrils, generally high up, but sometimes in view, and gives rise to snuffling and difficult breathing. It bleeds profusely on being interfered with, but this must be disregarded and the offending body removed. The most useful, though not very scientific, instrument is a small button-hook, which should be first greased and then carefully introduced up the nostril, when it should be turned gently but firmly to break up the growth as much as possible, and when the haemorrhage has nearly subsided, the exterior should be anointed with lard or vaseline, and a solution of chloride of zinc injected; a 10 per cent, solution will do well, but to prevent excoriating innocent parts a final syringing of soap-water and glycerine should be performed.

Iodoform is also recommended, and the insufflation of finely powdered burnt alum. Ligature has been commended, but if the reader will examine the nostrils of the biggest dog he can find he will see that its application is impossible.

OZOENA

is a fetid discharge from the nostrils, and may be caused, by the irritation of polypus, or of decayed teeth, abscesses in the thin plates of bone within the head, or as the result of chronic catarrh, or lodgment of foreign bodies, or

WORMS IN THE NASAL CHAMBERS.

There is a parasite recognised as belonging to the sheep and called pentastoma teniodes, but occasionally found in the dog. It causes snuffles and such acute annoyance when moving as to make the dog behave like a demented creature. Frequent sneezing is another symptom. If a discharge from the nose exists without ascertainable cause, or the other symptoms, above described, lead to the suspicion of worms, a few doses of snuff should be tried; it cannot do harm, and may result in expulsion of the uninvited guest. Injections of 10 per cent. solutions of ferri sulph. may cause him to quit his lodgings.

SNORING

may be attributable to the same cause, but the usual source of snoring is the relaxation of the soft palate; though not belonging properly to the respiratory apparatus, we speak of this condition of the velum palati here, because snoring is commonly looked upon as a defect in breathing — and it is. Old pugs are especially addicted to snoring, and while awake to making a noise which is described by school boys as “snorking.” Astringents applied on a mop to the back of the palate have a temporary effect, just long enough to keep down the noise during a visit from one’s mother-in-law, or while the dealer is selling the old dog for a young one, but there is no radical cure for it. Acid tannic or glycerine and borax are perhaps the best things to use.

CATARRH AND INFLUENZA.

Cats and dogs suffer from common colds and from influenza as do human beings. Influenza is most infectious as between one cat and another or from dog to dog, but is it infectious from cat to man? The household cat has been accused of all sorts of things, from witchcraft to the conveyance of diphtheria, but does she convey those influenza colds of which it is often remarked, “When the cat has a cold everybody in the house has one?” That black cats bring luck to a house, diphtheria to the baby, and necromancy to the “wizards who mutter and peep,” we can readily believe, because we were told so when children going to bed, and the notion took root “in the witching hour of night, when churchyards yawn.” Besides coming home ragged and torn, they catch the most frightful colds, and get no sympathy, as do human beings, when their nocturnal follies have laid them by the heels. When a cat sneezes she is promptly turned out of the room, while, if she coughs, everyone thinks she is going to be sick, and her ejectment is even less tenderly performed. Nevertheless, she has her feelings, and if we could read her thoughts, we should find she has but a poor opinion of our intelligence in behaving in such a manner to a creature in need of nursing and extra comfort. The symptoms of a common cold are too well known to need description, and the form of influenza met with in our patients is not the prostrating fever known by the same name in men and horses, but an aggravated cold, a profuse discharge from eyes and nose, accompanied by sneezing, coughing, loss of appetite, and staring coat.

Treatment consists in comfortable surroundings, in which to get through three or four days of great discomfort, without again getting wet, or being exposed to the conditions which brought about the disease. With due respect for those persons who vaunt specifics for the cure of influenza, it may be justly urged that if it is caused by the invasion of a specific microbe, which no remedy will kill, that would not also kill the patient, then no means of cutting short the disease will be certain till an antagonistic microbe can be found and employed to hunt the evil doer. The progress of bacteriology leads us to hope that in this direction lays a great future for medicine, which has not during the past 50 years kept pace with surgery, but and until the life history of such microbe is ascertained, and an antagonistic one bred to combat him, we shall have to go on using those remedies which experience teaches, or tradition says, modify the acute symptoms. These for cats and dogs are much the same as for human beings. We have seen the defluxion of mucus from the nose, and tears from the eyes in bad colds cut short by homoeopathic mercurius. The cough arrested by spongia or bryonia, while those who have at the initial stage of rigor began on bi-hourly alternate doses of aconite and belladonna, declared that the attack has been made altogether lighter. How would it have been without any treatment? This is the stumbling block of all curative medicine. Preventive medicine has its converts by the million, and the effects of surgery can be seen by all, but medicine given for the cure of disease is a speculative art; it cannot be called a science since there is nothing exact about it. Homoeopathic treatment recommends itself for dogs and cats for the same reason as for children; there is no tweaking of the nose, while a nauseous powder is placed upon the tongue, to be vomited amidst screams and tears the next moment.

COUGHS

we put in the plural, as there are many causes besides catarrh of which coughing is a symptom or stage in the progress of catarrhal inflammations.

Coughs may be roughly divided into two qualities, hard and soft. The former are generally attributable to irritation in the larynx or fauces, while the latter are symptomatic of deeper structures being involved.

With an ordinary sore throat a dog coughs passionately, as though angry, with something more annoying than actually painful — a trumpeting, harsh and frequently repeated cough, finishing up with a sound more akin to expectoration, which, in fact, often takes place, only that the mucus brought up is swallowed instead of ejected from the mouth.

A soft cough, such as accompanies inflammation of the lungs, is such a soft sound, that persons not accustomed to animals do not recognise the fact that the animal has a cough at all, though they may have noticed that he puffs his cheeks out from time to time.

For an ordinary dry, hard cough, spongia or bryonia is recommended. Chlorodyne in doses of from 1 minim to 10 minims has been found an excellent remedy, but counter-irritation to the throat, and a laxative for the bowels should be also used if this plan of sedative treatment is preferred. A wet compress instead of a liniment is a good remedy. Ol. terebinth, ol. sinapis, ol. caryoph or lin. ammon. briskly rubbed into the throat produce slight vesication. Nausea, as evinced by dribbling, may be disregarded; it is a common result of anything nauseous to the taste or objectionable to the sense of smell. It is more easily provoked in the cat than the dog; both exhibit their disgust in the same way, and not like horses who turn up the upper lip.

INFLAMMATION OF THE LUNGS

is more frequent now than in former days, and the probable reason, both in dogs and cats, is that they have been bred for points rather than constitution. Nature exacts a penalty for what is called scientific breeding, though a disregard of constitution would seem to take such breeding out of the realm of science. Dogs are bred from near relations in order to develop certain peculiarities, which fashion declares to be correct to-day, and discards in two or three seasons. All through the fancy stock — the aristocracy of the show-bench — there is a tendency to delicate and feeble constitution. The prize pigeon, bred by careful selection in order to develop particular feathers or colours, becomes scrofulous. The hero of the poultry pen begets pullets which will not lay or sit. The beautiful long-haired cats are frequently sterile, or such bad mothers, their progeny die unless provided with wet nurses. Dogs cannot be reared because malignant distemper kills the valuable pup, while passing by the worthless mongrel. Cows develop milking properties by increasing the deaths from; milk fever, and pedigree shorthorns become tuberculous to a fearful extent, while racehorses produce hereditary roarers.

Besides the soft cough, which is not, taken alone, diagnostic of inflammation of the lungs, there is a high temperature (as much as 106—7 Fahr.) evidenced by curling up in a corner, loss of appetite, and staring coat, cold ears, rheumy eyes and dry nose. The respiration is short and hurried, and if a short- coated animal, the ribs are seen in the rising and falling of the chest. Some persistently sit on their haunches with turned out elbows.

PLEURISY,

especially in dogs, may occur alone, but with cats it is generally associated with pneumonia.

The pleurae lining the chest and investing the lungs are subject to acute inflammation from cold, exposure to east wind, going into the water in cold weather, or oftener still, getting dry by sitting about, instead of by exercise and movement. All varieties of dogs and cats are liable to pleurisy, but more especially the long-haired cats and sporting dogs, and such as delight in swimming. Pleurisy, pneumonia and pluero-pneumonia, require pretty much the same treatment, and we take them as a group for that reason; the chief difference in the symptoms of pleurisy and pneumonia is that in the former the breathing is more painful, the flanks go in and out like bellows, and there is greater difficulty in moving. In the treatment modern practitioners are not altogether agreed. The most advanced scientists, or, at least, some of the most prominent, do not hold with counter-irritation, but the bulk of experienced men claim to have proved its great value, and it is probable that when some modern theory can be found to fit the practice there will be a general return to the plan of blistering the sides of the ribs with mustard or turpentine, or lin camph. co.

Hot water continually applied and covered with oiled silk, to prevent evaporation, is excellent treatment, but difficult in its execution — so few people will take the necessary trouble with a dog or cat, whereas the blister can be quickly applied, and the result rapidly attained.

Internal remedies calculated to allay coughing and moderate the temperature should be given, such as

Chlorodyne m 1 to 5.

Liq.ammon.acet. minim v. to 20.