THE CAT, PAST AND PRESENT

FROM THE FRENCH OF M. CHAMPFLEURY

WITH SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES BY

MRS. CASHEL HOEY

AND NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

(GEORGE BELL AND SONS, YORK STREET, COVENT GARDEN, 1885)

A FEW WORDS TO THE READER

You either love Cats, or you do not love them. In the former case, it will give you pleasure, such as only the friends of “the harmless necessary cat” can appreciate, to peruse a panegyric upon it full of knowledge, humour, and enthusiasm, by the celebrated writer, M. Champfleury. In the latter case, the persuasion of a man of genius, and his fine handling of his subject, may induce you to recognize the beauty, the intelligence, the wonderful variety of character, the surprising ways, and the fascinating qualities of an animal whose organization, the most eminent naturalists tell us, is a singularly perfect one, and whose worth as a household friend and companion has never before been set forth with so much zeal according to knowledge.

While I have been engaged in the pleasant task of translating this work, I have often longed to be able to impart the nature of my occupation to the home circle - to the cats, in fact, to whom we belong - and to take their opinion upon it. It would be very interesting to get at their views of the speculations in which M. Champfleury indulges, and to discover how far they would go with, him in his estimate of their own relations with the human race.

When we deal with the wonderful creatures of the animal world, almost as mysterious to us as those of the spiritual world, it must always be the old story of the Lion painted by the Man. In this particular instance at least, the Cat, could it assume the character of critic, would have no cause to complain of the Artist.

FRANCES CASHEL HOEY.

September, 1884.

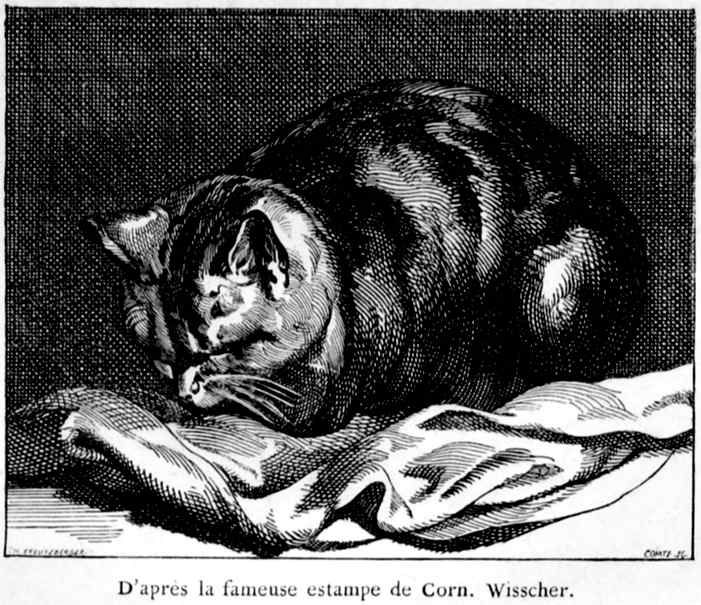

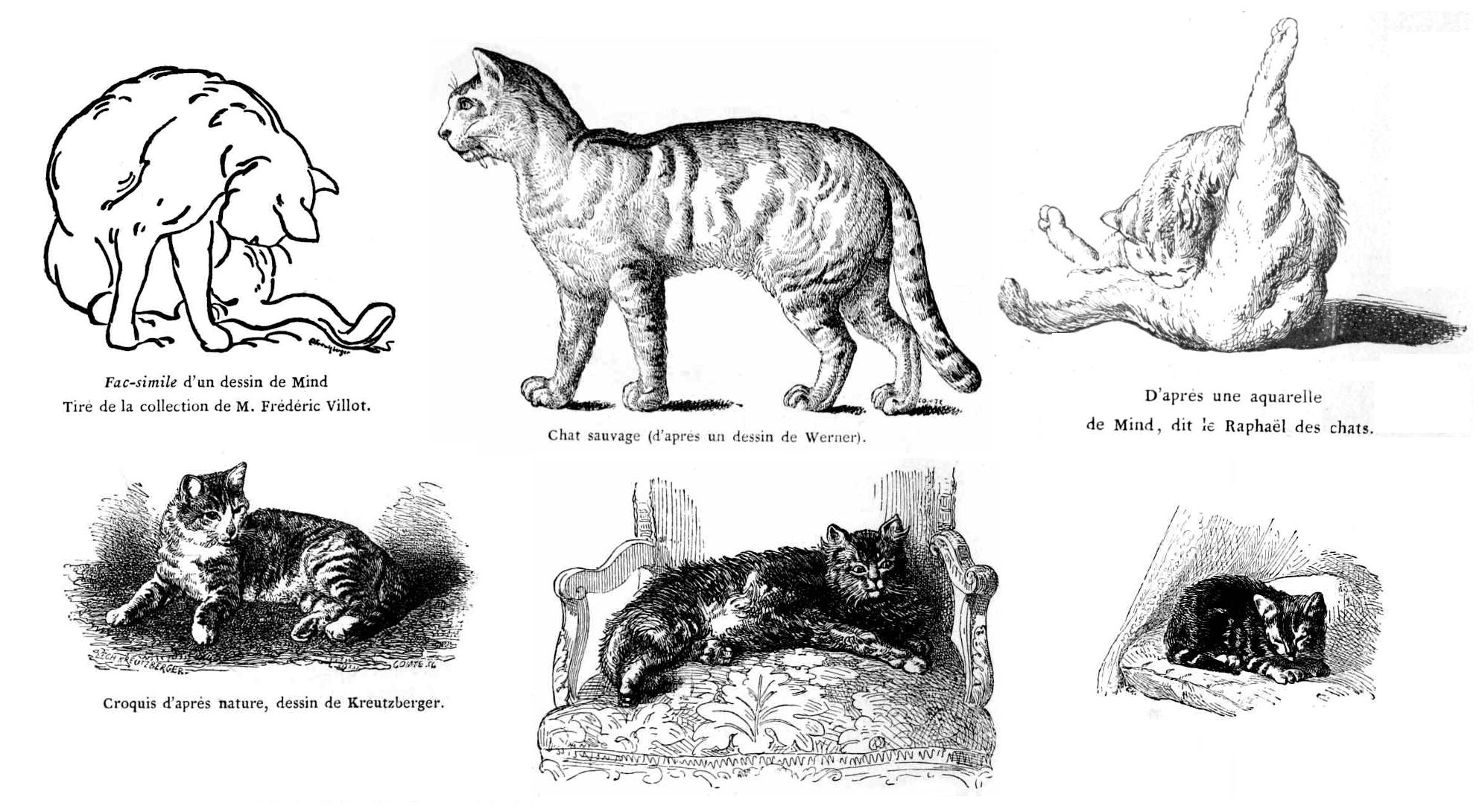

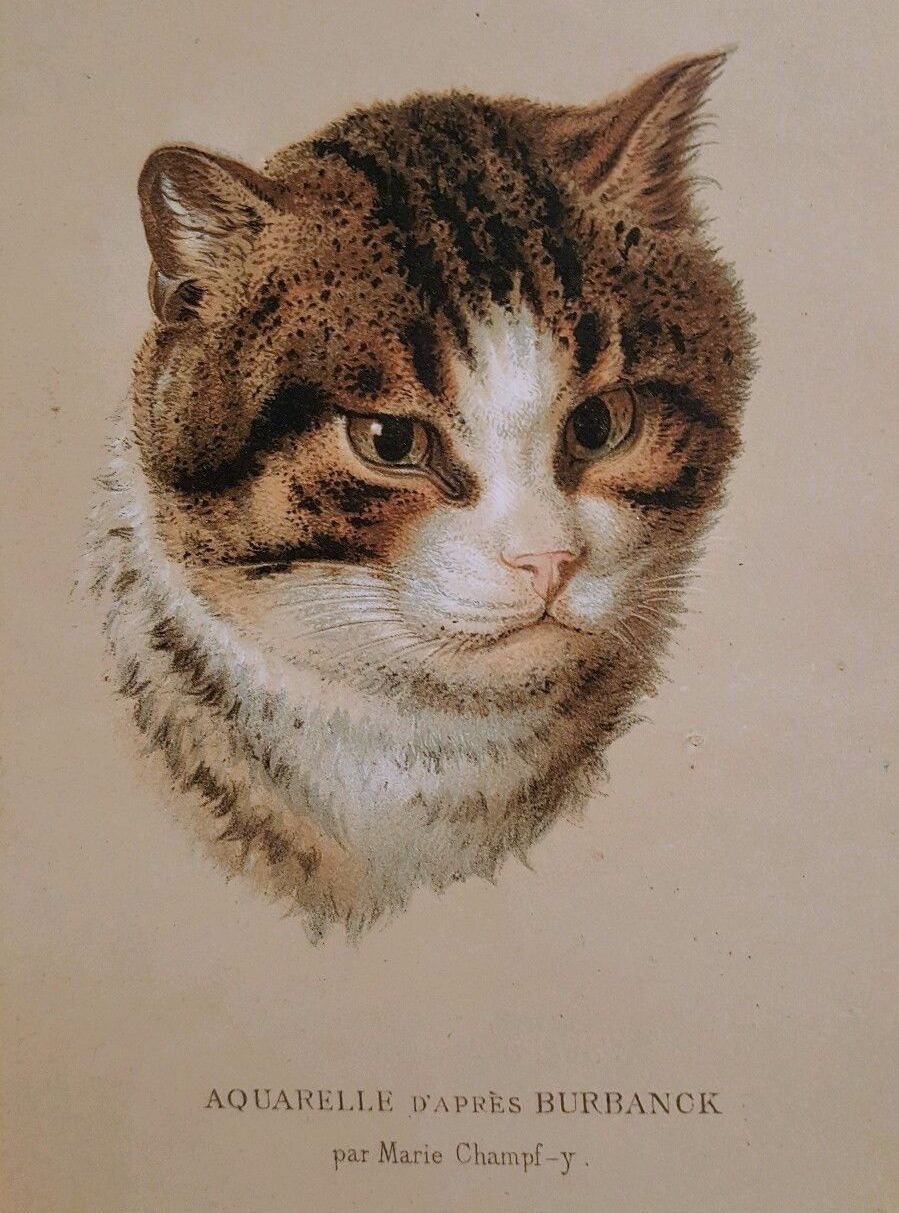

Illustration: After a watercolour by Mind, known as the Raphael of cats.

PREFACE 1869

To my friend Jules Troubat.

I.

It may seem strange that long studies are devoted to a simple individual, to the cat who, though summarizing some of the faculties of the feline race, cannot give a complete idea of the larger members of the species, but its sedentary habits allow the office worker to study it at any moment without interrupting his work. The cat has passed among the writers of the alchemists’ workshops where it is part of their modest interior, and it offers this peculiarity with the men of letters: it has almost as many detractors as if the cat itself was writing.

Like all creatures that the beings that provoke caresses, that give and receive them like women, if the cat is well-loved by some, it has not been forgiven by others, especially by metaphysicians. Many would admit, with Father Bougeant, in his entertaining little book of “Philosophical Musings on the Language of Beasts,” that "the beasts are nothing but devils," and that at the head of these devils walks the cat.

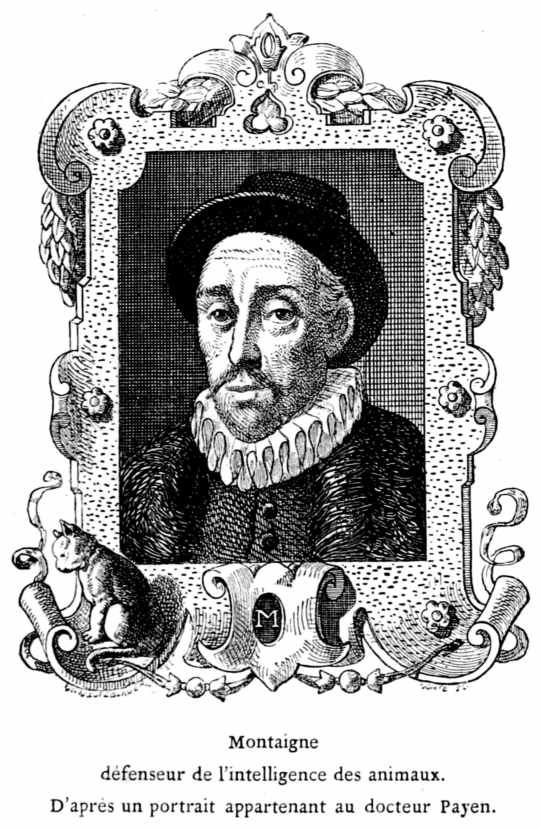

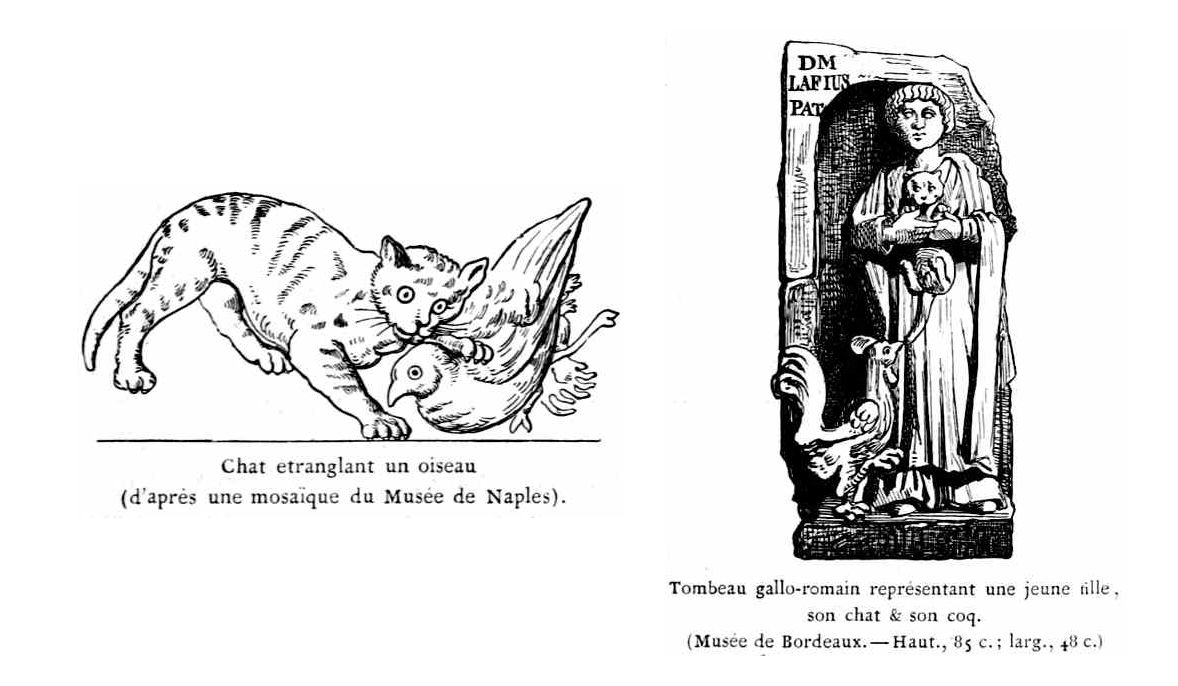

Descartes considers every animal an automaton. To combat this assertion, one would have to deploy a great deal of metaphysical paraphernalia, which I do not feel I have. I prefer other kinds of intellect: Aristotle, Pliny, Plutarch, Montaigne, who base their doubts on fact , proved by reason and observation.

Naturalists, those on whom it is convenient to rely, believe in animal intelligence, starting with the father of natural history. "The whole of animal life," says Aristotle, "gives several actions that imitate human life. This accuracy, which is the fruit of reflection, is even more apparent in small animals than in large ones. "This is a long way from the automata of Descartes.

With Montaigne one has an embarrassment of choice. His Essays are the richest arsenal in favour of the intelligence of animals. On almost every page, Montaigne enjoys rebutting man's cackle. "It is out of vanity," he says, "that man considers himself different, and separates himself from other animals, cutting himself away from his animal colleagues and companions, and giving himself that portion of faculties and forces that seems appropriate to him." Man’s animal brethren, according to this sceptic, has passed so much boldness under the cover of good-nature.

Montaigne grants the faculty of caution to bees, of judgment to birds; to him, the spider that spins his web deliberates, thinks and decides. This prudence, this judgment, this deliberation, these thoughts and these decisions, would provoke volumes of controversy demand of the metaphysicians who know little of animal.

These dreamers, who look neither at the sky nor the stars, have rarely been troubled by this thought: what does the thinking animal think? Fortunately, there are meditative and observant minds, independently eager, who, struck by the independence of certain animals, communicate directly with them, study their behaviour, amass facts unknown to those naturalists that remain shut in laboratories, and arrive at audacious conclusions, for which they are pardoned because of their character, their life, their science, and their virtues.

We can’t deny the scientific authority of Audubon, the naturalist, living in the forests of America, who surrounds his life with nature’s scenes. A positive spirit, who discusses his recollections of nature eloquently, served by an active, intelligent brain, all of Audubon’s words are bear the hallmark of truth; his accounts are so faithful that you can believe them. This American naturalist is of Franklin’s ilk, a moralist, an enlightened believer. And yet this elevated spirit has arrived at the idea that animals can have the sense of Divinity.

Studying two crows flitting freely through the air, this is what Audubon says: "I wish I could render the variety of musical inflections with which crows converse with each other during their tender journeys. I don’t doubt that sounds express the purity of their conjugal attachment, as it continues, strengthened, by long years of happiness tasted in each other’s company. Thus they recall the sweet memories of their youth; they recount the events of their life; they depict shared pleasures, and perhaps they finish with a humble prayer to the Author of their being , that he deigns to continue them yet.” [Audubon, Scenes of Nature in the United States . Voll II, Paris, 1837.]

I won’t dwell on what might appear paradoxical to anyone other than that great American naturalist. That is enough on the intelligence of animals. I will come back to the cats and it just remains for me to say how, having lived with cats since my childhood, the idea came to me from those studies.

II.

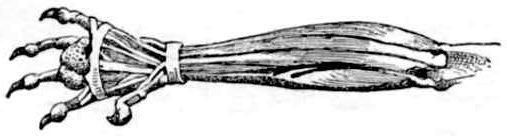

One of the things which surprised me most in the revelations which the revolution of 1848 brought about was that fifty thousand francs had been granted to the author of the “Anatomy of Cats” on the secret funds of the Ministry of the Interior.

It isn’t surprising that there are politicians who break their oaths and betray their former masters. Their baseness is paid for with money, their disgrace with honours, and it has always been that way; but finding a writer awarded fifty thousand francs for occupying himself with cats in the pay of the ministers, astonished me when I browsed the lists of the terrible retrospective Review (audit).

The happy mortal favoured so liberally by the government of Louis-Philippe was Strauss-Durckheim . He is now dead, and I must say that he was a German of true knowledge, who, after having spent his life in study and retirement, produced in exchange for fifty thousand francs, works in which the cat is treated as a king of creation. [The Theology of Nature, by Strauss-Durckheim. 3 vol. 1852 (among other works)]. His Cat's Monograph, in particular, is supported by plates where the muscles, nerves, and skeleton of the animal are shown with care.

What the learned Doctor has done for anatomy, I will try to do for the story of feline ways, but it is from the public that request a subsidy, and if the he doesn’t underwrite my study with fifty thousand francs, then the funds raised by the publications and sale of this book to readers won’t appear on any retrospective Review .

Champfleury.

CONTENTS.

PART I.

Chapter

I. The Cat in Ancient Egypt

II. Cats in Eastern Lands

III. The Cat in Greece and Rome

IV. The Cat in Popular Tradition

V. The Cat in Heraldry, and on Signs

VI. The Enemies of the Cat in the Middle Ages

VII. Utilitarian Enemies of the Cat

VIII. Addressed to Utilitarians

IX. The Enemies of the Cat - Sportsmen

X. Advice to Sportsmen

XI. The Feline Race in Statistics

XII. Cats in Court

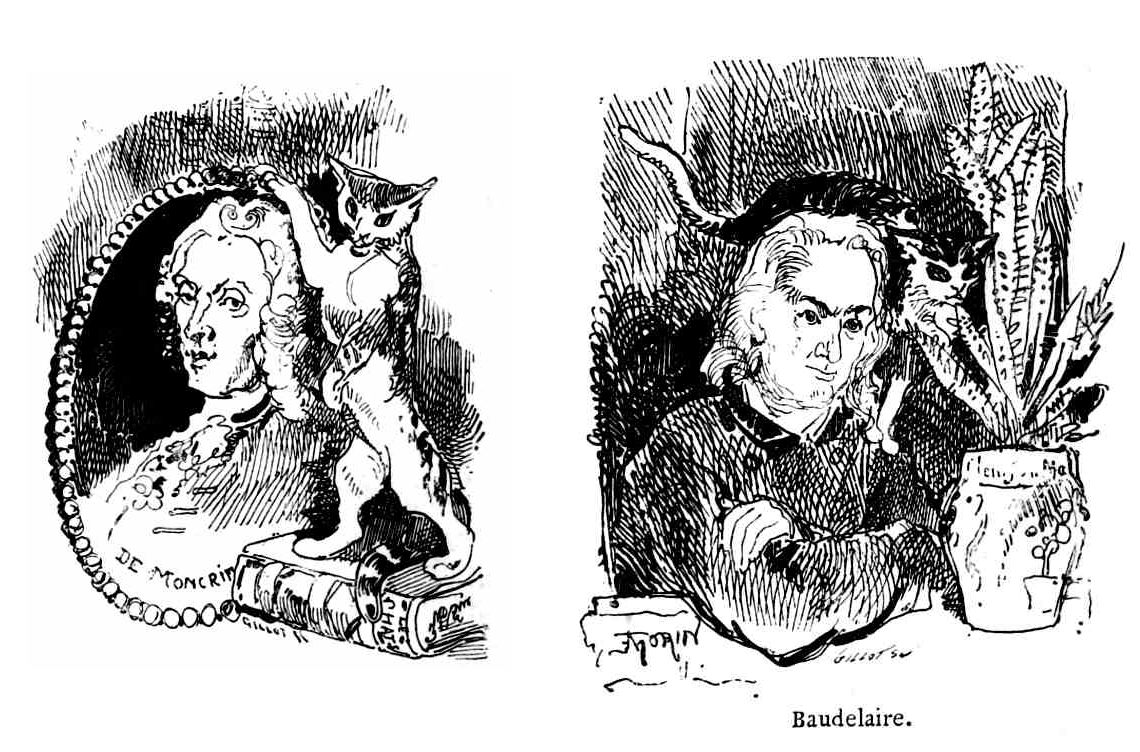

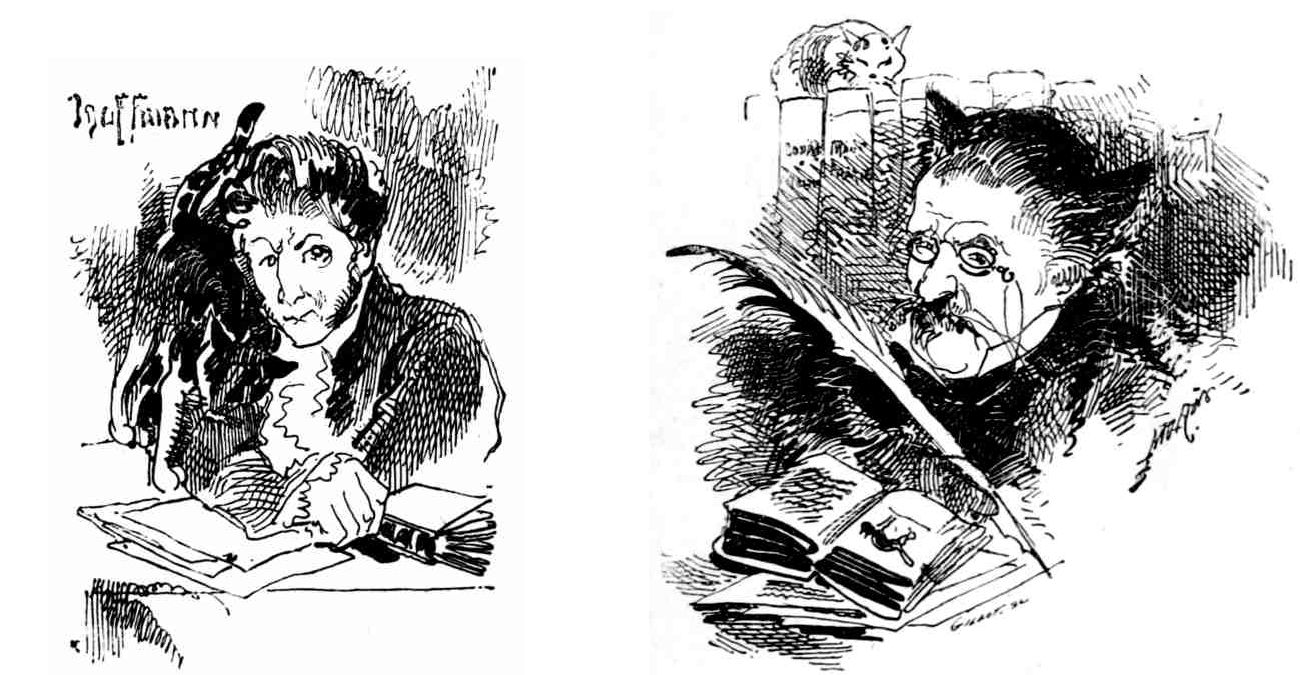

Mil. The Friends of Cats

XIV. Concerning some Clever People who took Pleasure in the Society of Cats

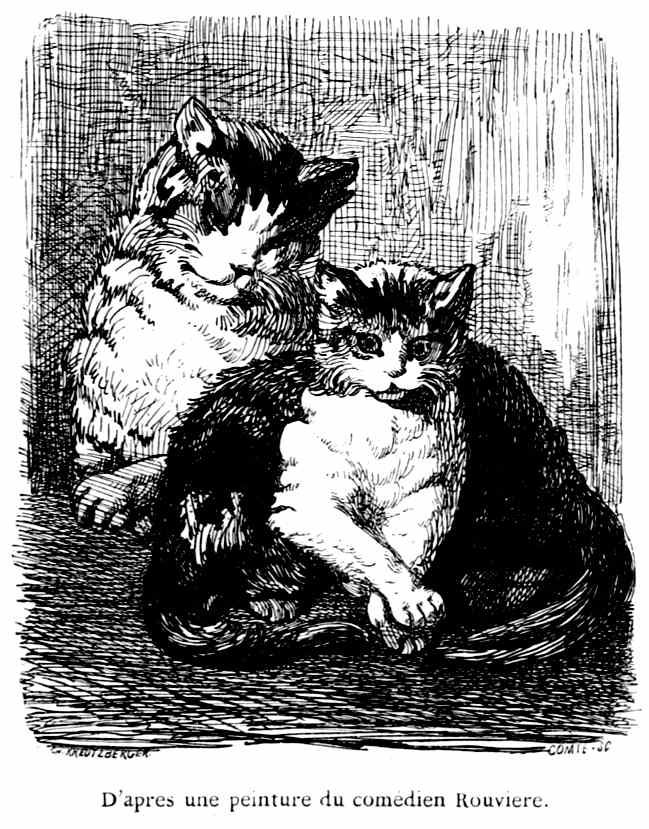

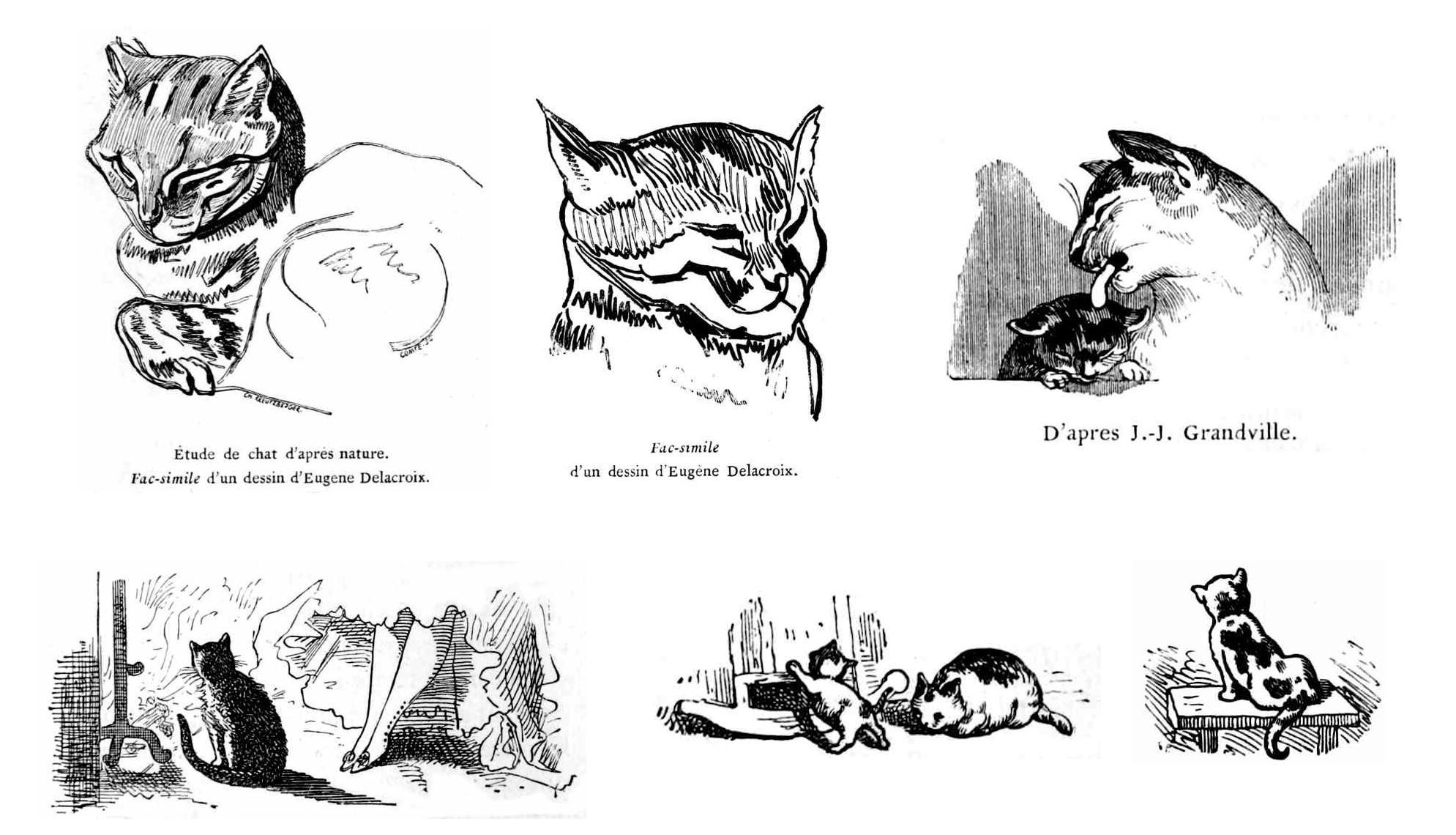

XV. Painters of Cats

PART II

XVI. Is the Cat a Domestic Animal?PART III

XXI. Five o’Clock in the Morning

XXII. The Infancy of the Cat

XXIII. Play to the Cat, Death to the Mouse

XXIV. Family Feeling

XXV. Cleanliness

XXVI. Cats Sketched from Nature

XXVII. Local Attachment to the Cat

XXVIII. Country Cats

XXIX. Out for a Walk

XXX. A Polite Discussion among certain Distinguished Personages on the Subject of Cats and Dogs

XXXI. Cats in Love

XXXII. Nervous Affections of the Cat

XXXIII. The Egotism of Cats

APPENDIX.

I. The Cat in Ancient Times and among the Hebrews

II. Etymology of the word Cat

III. A Wild Cat

IV. Cat Music

V. Cats and Religion

VI. Louis XIII. and Cats

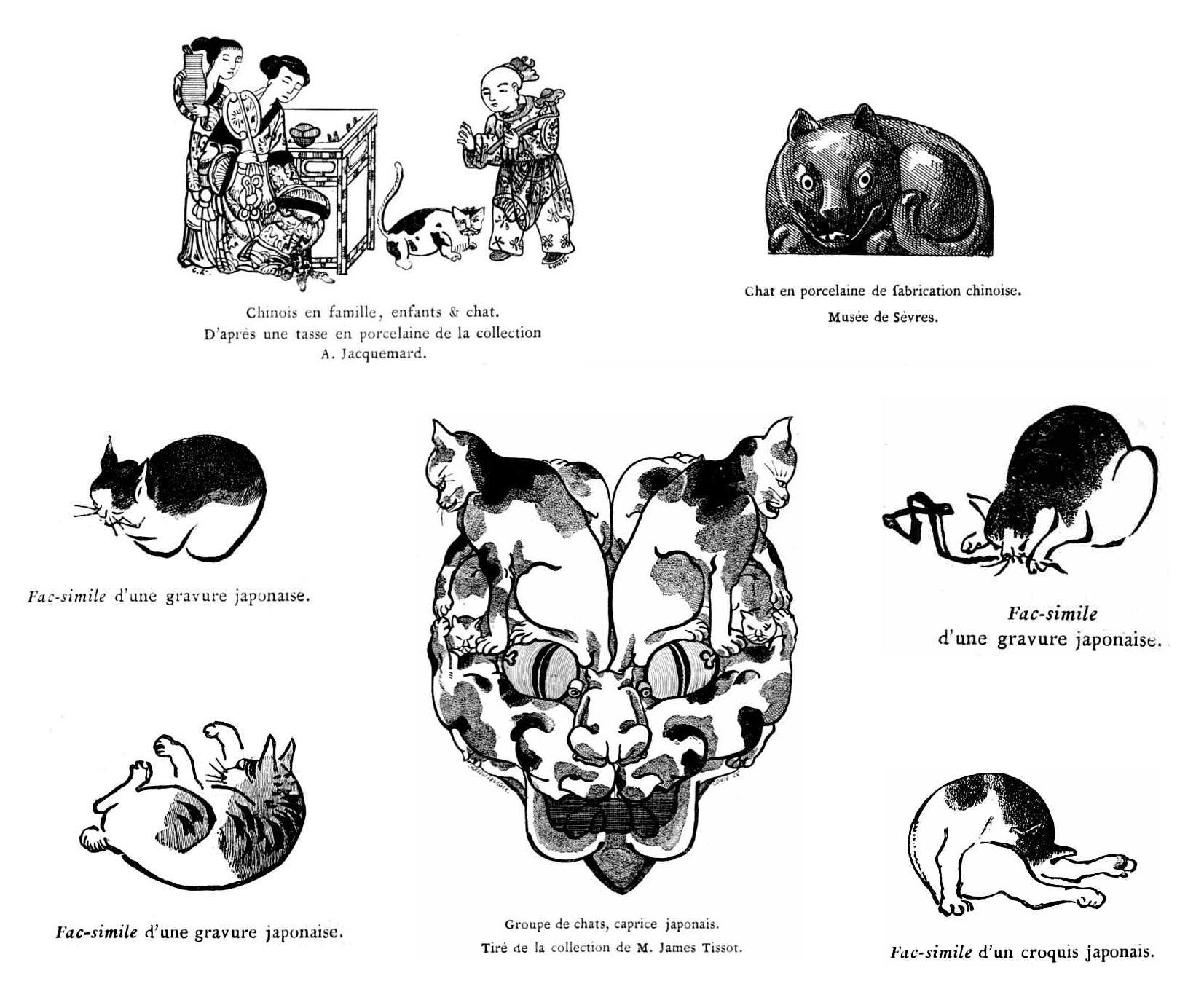

VII. The Japanese Painter Fo-Kou-Say

VIII. Doges and their Cats

IX. The Cats of M. de la Fontaine

X. Gottfried Mind, the Raphael of Cats

XI. Cats in China

XII. Legends

XIII. Burbank the Painter

XIV. Cat-Language, by the Abbé Galiani

XV. The Cat’s Bóle in Architecture

SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES BY THE TRANSLATOR.

I. (note)

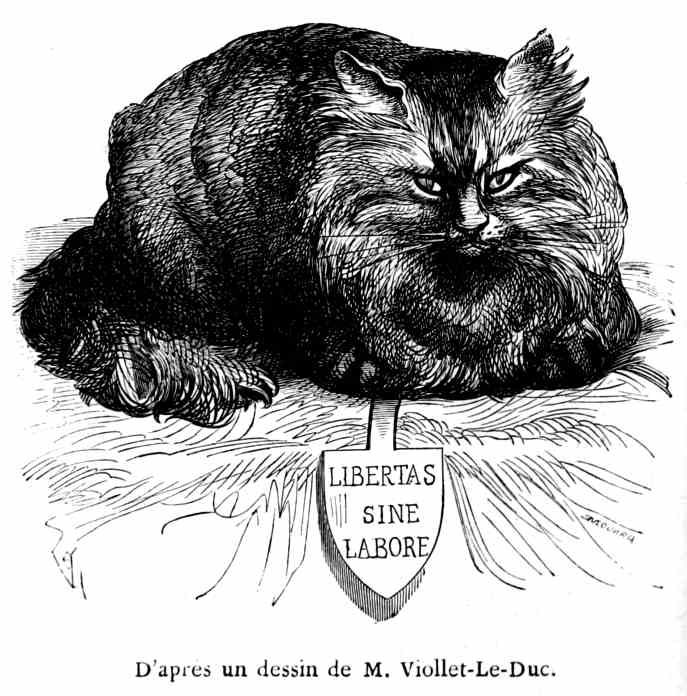

II. On the Persian Puss

III. A Four-Footed Friend

THE CAT, PAST AND PRESENT.

Chapter I. THE CAT IN ANCIENT EGYPT.

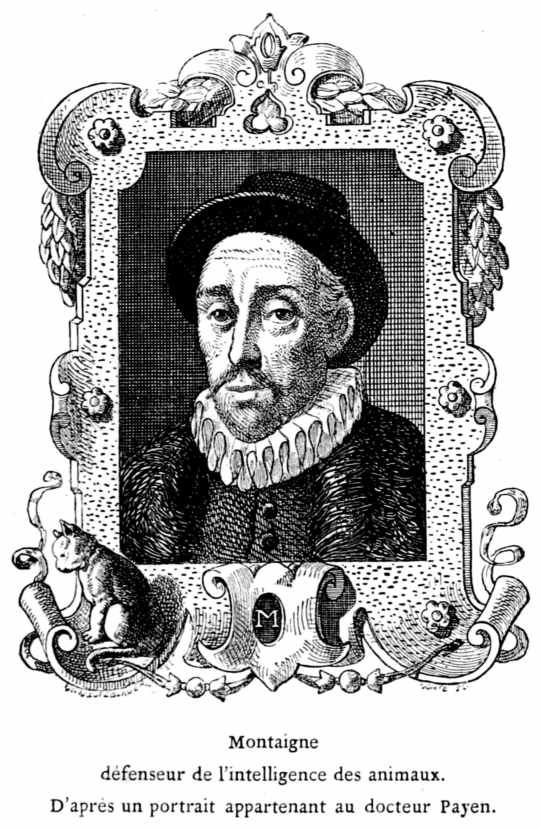

A naturalist, on examining a collection of Egyptian monuments, and observing that cats abound in them, either in the condition of mummies, or represented in bronze, is led to ask, how was the cat introduced into the country of the Pharaohs? The actual condition of our knowledge does not enable us to solve that problem. Egyptologists have not found any representation of the cat upon buildings contemporaneous with the pyramids. The cat appears to have been acclimatized at the same time with the horse, at the beginning of the new empire. (About 1668 B.C.)

The most ancient version of the Ritual of the Dead of which we have any knowledge, goes no farther back. At that epoch we find the cat represented in mural paintings, sitting under the arm-chair of the mistress of the house; a position also occupied by monkeys and dogs.

The rarity and the utility of the cat probably led to its admission to the ranks of sacred animals, with a view to its systematic propagation. Its utility is attested by paintings representing sporting scenes in the marshy valley of the Nile, where cats plunge into the water to retrieve and carry the game. The Egyptians, when pursuing game in the marshes, used light boats, and were attended by their families, their servants, and their animals. Among the latter cats are frequently represented.

[Footnote. The Egyptians were wonderfully skilled in training animals. At the present day in country places, a starving cat may perhaps be seen to dip its paw cautiously into a pond and catch a little fish as it darts by; but th race has entirely lost its ancestral faculty of fishing, and if a cat were to retrieve a wild duck shot in a marsh, and carry it to the sportsman, the feat would be regarded as miraculous.]

On a tomb at Thebes there is a painting of a sporting scene, in which a cat points, like a dog, by the side of his master, who stands up in a boat, and is about to throw the bent stick, like an Australian boomerang, called a schbot. Another painting, also taken from a tomb in Thebes, and which is now in the British Museum, is described in Wilkinson’s “Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians,” as follows:- “A favourite cat sometimes accompanied the Egyptian sportsmen on these occasions, and the artist intends to show us, by the exactness with which he represents the animal seizing the game, that cats were trained to hunt and carry the water-fowl.”

M. Mérimée has been good enough to make a drawing for me from this fragment of painting. The cat carries the birds to his master, who is waiting for them in a boat. Pictures of this kind, in which cats figure, belong to the eighteenth and nineteenth dynasties. (About 1638, and 1440 B.C.) One of the most ancient representations of the cat is to be found in the Necropolis of Thebes, which contains the tomb of Hana. On the stela is the statue of the King, standing erect, with his cat, Bouhaki, between his feet.

[Footnote. King Hana seems to have belonged to the eleventh dynasty. At any rate, he is earlier than Rameses VII., of the twentieth, who had his tomb explored.]

We constantly find, in the centre of the small Egyptian images in bronze or enamelled earthenware in our museums, a crouching cat, with the symbolic eye, an emblem of the sun, engraved upon its collar. King Hana’s cat wears golden ornaments suspended from its pierced ears.

The cat is also represented on certain medals of the noma of Bubastis, where the goddess Bast (the Bubastis of the Greeks), was held in special reverence. That goddess (a secondary form of Pasht), is usually depicted with a cat’s head, and holding the sistrum, the symbol of the harmony of creation. Those cats to whom sacred honours had been paid in the temple of Pasht during their lifetime, as the living image of that goddess, were embalmed after their death, and buried with great ceremony.

Several funeral statues of women bear the inscription TECHAU, the cat, in token of the patronage of the goddess Bast. Frenchmen occasionally call their wives “ma chatte,” but they probably attach no hieratic association to that term of endearment.

Some cat-mummies, found in wooden coffins at Bubastis, Speos, Artemidos,Thebes, and elsewhere, have painted faces. These curious mummies, all long and thin, look like bottles of rare wine done up in plaited straw. The cat in the accompanying drawing was an alert creature, doubtless, and much revered; the wrappings and the unguents are eovidence of that.

The symbolism of the cat still remains shrouded in mystery, although it has been treated of by both Horapollo and Plutarch, for the legends related by these historians are contradictory. According to Horapollo, the cat was worshipped in the temple of Heliopolis, sacred to the sun, because the size of the pupil of the animal s eye is regulated by the height of the sun above the horizon. Thus the cat’s eye symbolises the marvellous orb of day.

Plutarch states, in his treatise on “Isis and Osiris,” that the image of a female cat was placed at the top of the sistrum as an emblem of the moon. “This,” says Amyot, “was on account of the variety of her fur, and because she is astir at night; and, furthermore, because she bears firstly one kitten at a birth, and at the second, two, at the third, three, and then four, and then five, until the seventh time, so that she bears in all twenty-eight, as many as the moon has days. Now this, perchance, is fabulous, but ‘tis most true that her eyes do enlarge and grow full at the full moon, and that, on the contrary, they contract and diminish at the decline of the same.”

So that, while Horapollo discerns a mysterious analogy between the pupil of the cat’s eye and the sun, Plutarch assigns that relation to the moon.

Modern science, leaving it to necromancy to define the influence of the stars on animals, has explained these phenomena of vision by optics. The varying number of kittens produced at successive births, of which Plutarch speaks, may also be classed among the fables of the classic naturalists. Nor is Herodotus more veracious when he makes the following statement:-

“If a fire occurs, cats are subject to supernatural impulses; and, while the Egyptians, ranged in lines with gaps between them, are much more solicitous to save their cats than to extinguish the fire, those animals slip through the empty spaces, spring over the men’s shoulders, and fling themselves into the flames. When such accidents happen, profound grief falls upon the Egyptians. When, in any house, a cat dies a natural death, the inmates shave the eyebrows only; but if a dog dies, they shave their heads and their bodies.”

The fact of the cats throwing themselves into the flames is one which requires confirmation. I prefer to give credit to the statement, also made by an ancient, that the Egyptians gave each female cat a suitable husband at the proper age, paying great attention to harmony of taste, temper, and personal appearance, between the high contracting parties.

The Case of a Cat-Mummy in the Museum of the Louvre.

By what name was the cat known to the Egyptians? The antique rituals in the Louvre give the name as Mau, Mai, Maau; some Egyptologists have read Chaou on certain monuments. I am informed by a friend who is very erudite in such matters, that the correct reading is Maou. This forms one of those onomatopes [words that sound like the things they represent] which so frequently occur in all primitive languages.

With due respect to the Egyptologists, I take leave to express my conviction that the translation of certain hieroglyphs is beyond them, and that their cabalistic language will in all probability remain for ever the cere-clothed mummy it now is.

CHAPTER II. CATS IN EASTERN LANDS.

A distinguished Egyptologist, M. Prisse d’Avennes, has collected important material for a history of Art in many countries, whose manners and customs he has closely observed, and he has furnished me with the following facts concerning the domestication of the cat in modern Egypt:-

“The Sultan, El-Daher-Beybars, who reigned in Egypt and in Syria towards 658 of the Hegira (a.d. 1260), and is compared by William of Tripoli to Nero in wickedness and to Caesar in bravery, had also a particular affection for cats. At his death he left a garden, called Gheyt-el-Quottah (the cat’s orchard), which was situated near his mosque outside Cairo, for the support of necessitous and masterless cats.

Subsequently the field was sold by the administrator, under the pretext that it was unproductive, and resold several times over by the purchasers. In consequence of a succession of dilapidations, it now produces only a nominal rentof fifteen piastres per annum, which, with some other legacies of the same kind, is appropriated to the maintenance of cats. The Kadi, who is the official administrator of all pious and charitable bequests, ordains that at the ‘Asi,’ or hour of afternoon prayer, between noon and sunset, a daily distribution of a certain quantity of the entrails of animals, and refuse meat from the butchers’ stalls, all chopped up together, shall be made to the cats of the neighbourhood. This takes place in the outer court of the Mehkémeh, or tribunal, and a curious spectacle may be witnessed on the occasion. At the usual hour, all the terraces in the vicinity of the Mehkémeh are crowded with cats; they come jumping from house to house across the narrow streets of Cairo, in haste to secure their share; they slide down the walls, and glide into the court, where, with astonishing tenacity and much growling, they dispute the scanty morsels of a meal sadly out of proportion to the number of the guests. The old hands clear the food off in a moment; the youngsters and the new-comers, too timid to fight for their chance, are reduced to the humble expedient of licking the ground. Anybody who wants to get rid of a cat, takes it there, and loses it in the midst of the confusion of this strange feast. I have seen basketsful of kittens deposited in the court, to the great annoyance of the neighbours.”

Similar customs exist in Italy and Switzerland. In Florence there is a cloister, situated near the church of St. Lorenzo, which serves, I am told, as a house of refuge for cats. Any person who is either unable or unwilling to keep his cat may take it to this establishment, where the animal is fed and kindly treated. Also, any person who wants a cat, may go there and select one; there are specimens of every kind and of all colours. This is one of the curious institutions bequeathed by the past to the city of Florence.

At Geneva, cats prowl about the streets like dogs at Constantinople. They are respected by the people, who charge themselves with the maintenance of these free animals. Every day, at the same hour, the cats come and take np their positions at the house doors, where their food is served to them.

In Rome, too, at a certain hour, butchers’ men go through the city, laden with meat for the cats. They utter a peculiar cry, and the animals come out of their houses to receive their allowance, for which their owners pay a fixed sum monthly. I must now return to Egypt, and the narrative of M. Prisse d’Avennes:-

“Cats in Egypt are much more sociable and attached than cats in Europe; probably because they are much better cared for, and treated with such affection that they are permitted to eat out of the same dish with their masters. The Arabs have other motives for respecting cats, and sparing their lives. It is a general belief that Djinns assume the form of the cat, and haunt houses. Stories, as extravagant as any of those in the ‘Arabian Nights,’ are told in support of this superstition. The inhabitants of the Thebaid are even more credulous, and their imagination lends, unknown to themselves, a poetic form to the lethargic slumber of catalepsy. They hold that, when a woman gives birth to twins, boys or girls, the latest born (whom they call baracy) experiences for a certain period - in some instances throughout his whole life - an irresistible longing for certain kinds of food, and that, the individual frequently assumes the shape of various animals, and in particular that of the cat, in order to gratify this desire. During this transmigration of the soul into another body, the human being remains inanimate, like a corpse; but so soon as the soul has satisfied its appetite, it returns, and restores life to its habitual form. On one occasion I killed a cat which had committed sundry depredations in my kitchen at Luxor. A druggist in the neighbourhood came to me in a great fright, entreated me to spare all animals of that species, and informed me that his daughter, who had the misfortune to be baracy, frequently took the shape of a cat, that she might eat the sweetmeats served at my table.

“Women condemned to death for adultery are thrown into the Nile, sewn up in a sack with a female cat. This refinement of cruelty is perhaps due to the oriental idea that of all female animals the cat bears the closest resemblance to womankind, in her suppleness, her slyness, her coaxing ways, and her inconstancy.”

CHAPTER III. THE CAT IN GREECE AND ROME.

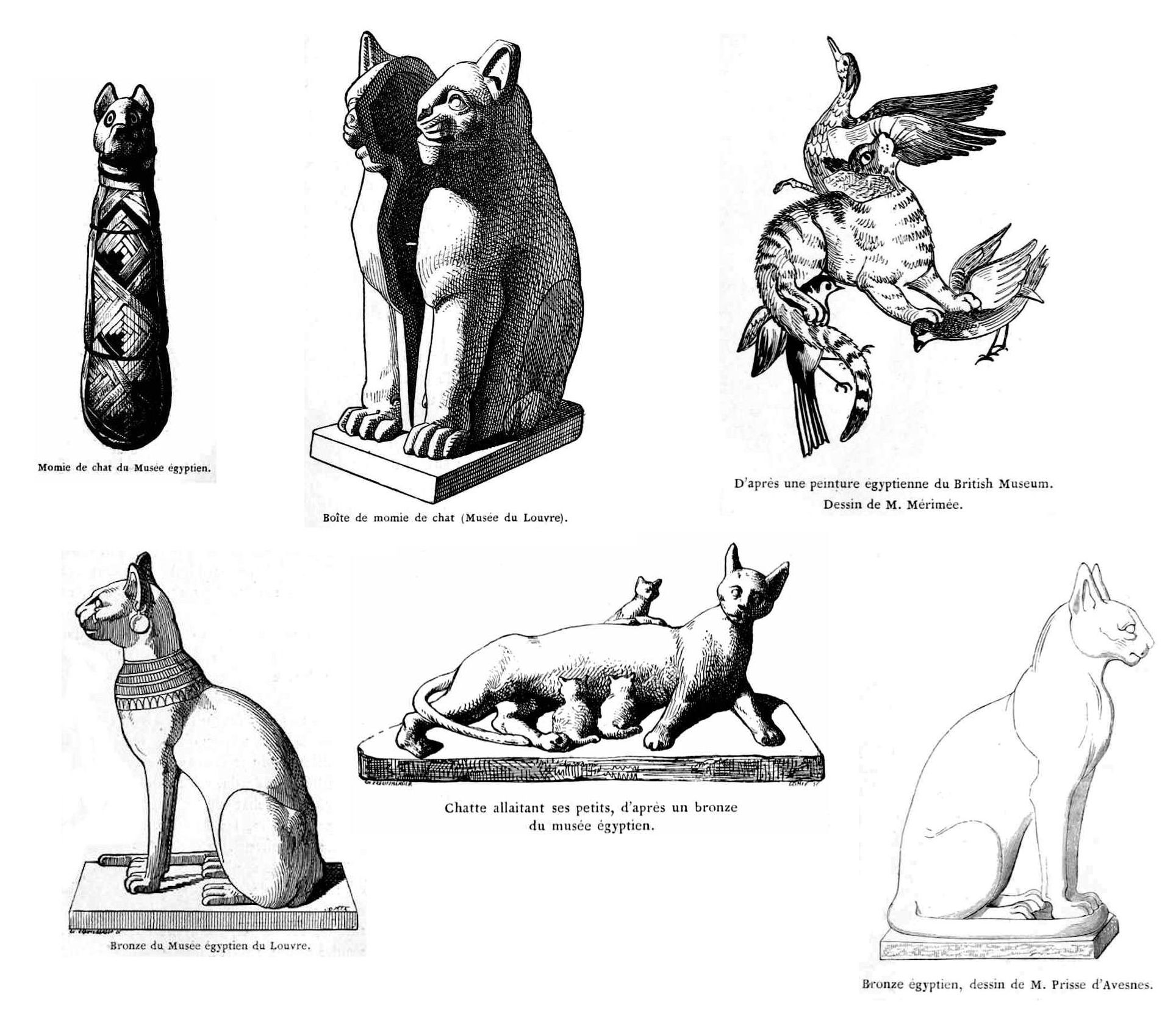

It is singular that the cat, an object of worship to the Egyptians, from whom it received a positive cultus, was entirely neglected by the Greeks and Romans. Although Egyptian artists had not failed to discern the fine outlines through the soft coat of the animal, it was natural that the cat should not have been represented by Greek sculptors, for they worked exclusively on grand lines. It is, however, difficult to understand why the Romans, who took pleasure in depicting domestic scenes as well as imposing objects, should have tailed to represent the cat.

In Rome and Athens that animal seems to have been neglected in proportion to its popularity in Egypt; for it is mentioned only by poets who wrote in the decline of either empire. Bearing in mind, therefore, the wide interval between the representations of the cat upon the Egyptian monuments and those upon the buildings of the Lower Empire, I shall act as prudentiy as Wilkinson did when he demurred to the identity of domestic animals like our own cats with the feline creatures that plunged into the water to retrieve from the birds wounded by the Egyptian schbot. Modern naturalists at first believed the mummied Egyptian cat to be the same as our domestic pussy, but they afterwards recognized special variations between the species.

The cat by which the Egyptians were attended on their sporting excursions, seems to have been a sort of cheetah; its coat resembles that of the hunting leopard.

The Greeks and Romans did not care to admit beasts into their houses, which, however useful for hunting purposes, were too wild for the domestic circle. And yet, in the dialogue of the Syracusans, Theocritus makes the mistress of a slave scold her in the following terms:-

“Ennoa, bring water! ” cries Prassinoé. “ How slow she is! The cat wants to lie down and rest softly. Bestir thyself, then. Quick with the water, here! Etc., etc.”

[Footnote: Learned philologists, to whom Theocritus is a religion, bid me state that this should be read, “it is the business of cats (or, it is for cats) to sleep softly.”]

Theocritus, by comparing a lazy slave to a cat, conveys to us an idea of the animal such as it has come down to our time. The domestic cat was already a sufficiently familiar object of the life of the period to be introduced into the poet’s dialogue as a visible image.

We find no traces, properly speaking, of any domestic cat, except in this charming Syracusan dialogue, between the Egyptian artists of the eighteenth dynasty (1638 years B.C.) who adorned tombs with representations of cats, and the poet Theocritus, who was born 260 years before the Christian era.

Without venturing on hazardous hypotheses, we may conclude that the acclimatization of the cat, disdained by Athens and by Rome, was accomplished by chance in the Lower Empire. A couple of Egyptian cats were probably carried away as curiosities, just as our African officers brought home lion-cubs after the conquest of Algiers, and reared them; then, no doubt, a slow domestication and deterioration of the cat took place, through the loss of its liberty. It was, however, considered useful for the destructions of rats, and although disregarded by the poets, the effigy of the animal was preserved by artists in mosaic.

The petty poets of the “Decline and Fall” despise the cat, mention its defects only, and strongly denounce its voracity.

Agathias, a writer of epigrams in the time of the Lower Empire, and a lawyer or scholasticus at Constantinople, who lived from 527 to 565, under the reign of Justinian, has left two funereal epigrams, in which the cat cuts a sorry figure:-

“O my partridge! Poor exile from the rocks and the heath, thy little willow-house possesses thee no longer! At the rising of the rosy dawn no more dost thou rustle thy wings in its warmth. A cat has torn off thy head. I seized the rest of thy body, and he was unable to appease his odious voracity with that. Let the earth not lie lightly on thee, but cover thy remains weightily, so that thine enemy may not disinter them.”

Thus does Agathias give rhythmical vent to his grief, and then, having shed his tears, the poet meditates his vengeance. This is the second epigram:-

“The domestic cat which has eaten my partridge flatters himself that he is still to live under my roof. No, dear partridge, I will not leave thee unavenged, but on thy grave will I slay thy murderer. For thy shade, which roams tormented, cannot be quieted until I shall have done that which Pyrrhus did upon the grave of Achilles.”

So, for having eaten a partridge - and not even that, for he was done out of the body - the unfortunate cat was to be sacrificed to its manes.

Damocharis, a disciple of Agathias, whom his contemporaries called “the sacred pillar of grammar,” was touched by the grief of his master, and, being anxious to prove his sympathy, heaped fresh invectives on this same cat:-

“Detestable cat, rival of homicidal dogs, thou art one of Actaeon’s hounds. In eating the pet partridge of thy master, Agathias, it was thy master himself thou wast devouring. And thou, base cat, thinkest only of partridges, while the mice play, regaling themselves upon the dainty food that thou disdainest.”

The exaggeration of these invectives leads to a suspicion that Damocharis was making fun of his master. Here is a pretty pother all about a partridge! And the comparison with those homicidal dogs, Actaeon’s hounds, is surely sarcastic.

However, let the motive of Damocharis have been what it may, it is clear from these few fragments of the Lower Empire, that, in its days, cats had declined far indeed from the worship formerly paid to them in Egypt.

I have gone through more than one museum of antiquities, examined a great number of publications, and questioned divers archaeologists, but I cannot discover that the cat is represented upon any vase, medallion, or fresco. In the Cabinet of Gems there is an engraved cornelian representing a sceptre and an ear of corn divided by the inscription:-

LVCCONIAE FELICVLAE “The inscription upon the seal,” writes M. Chabouillet, in his catalogue “gives us the names of its owner, a woman named Lucconia Felicula. Felicula signifies ‘Little Cat.’

The carving indicates a debased period in art.” This is the only monument to the cat to be found in our museums of the epoch of the Decline and Fall. [Footnote: Caylus says that the sceptre represents a tiring or head pin, and this is also the opinion of the present Director of the Cabinet of Gems.]

In the provinces and throughout Italy, more numerous proofs of the acclimatization of the cat are to be found. At Orange, Millin saw a mosaic representing a cat in the act of catching a mouse, but the portion that formed the cat had been destroyed. [Footnote: Voyage dans la Midi de la France,” vol ii, p. 153.]

The Pompeian mosaic is more significant; the cat devouring a bird may serve as an illustration of the epigrams of the Antholologia, which are of about the same period. [Footnote: According to Pliny, mosaic art dates from the reign of Sysla, nearly one hundred years prior to the Christian era.]

In the Museum of Antiquities at Bordeaux there is a representation of a young girl holding a cat in her arms on a tomb of the Gallo-Roman epoch. At her feet is a cock. At that time their playthings, and the domestic animals among whom they had lived, were buried with the bodies of children. Unfortunately the principal portion of this precious monument of the fourth century, the cat, which particularly interests us, has been so much injured that only the vague form of the animal remains. [Footnote: On the left side of the head are the following letters:- D M LAFIVS PAT. The other side of the niche is destroyed, so that the name of the young girl is unknown; the father’s name seems to have been Lapitus or Lafitus.]

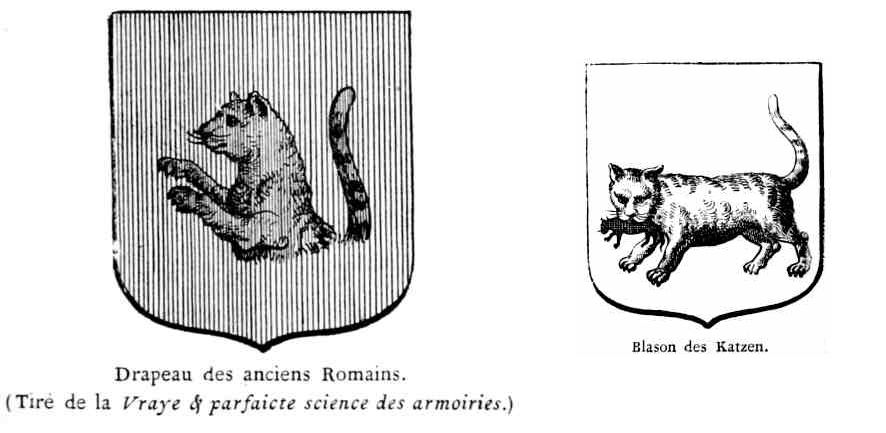

Ancient authors of works on heraldry also give us some information derived from Latin authors. According to Palliot, the Romans frequently blazoned the cat upon their shields and targets. [Footnote: “La Vraye et parfaicte science des armoiries,” Paris, MDCLXIV.]

“The company of soldiers, Ordines Augustei, who marched under the command of the Colonel of Infantry, sub Magistro peditum, bore on their ‘white’ or ‘silver’ shield, a cat of the colour of the mineral prase, which is sinople, or sea-green. The cat is ‘courant,’ and turns its head over its back. Another company of the same regiment, called ‘the happy Old Men’ (Felices seniores) carried a demi-cat, red, on a buckler gules; in parma punica diluciore, with its paws up, as if playing with someone. Under the same chief, a third cat passant, gules, with one eye and one ear, was carried by the soldiers qui Alpini vocabantur.”

Examples of a similar kind might no doubt be multiplied by examining ancient works on heraldry, but these will be sufficient to satisfy ordinary curiosity on this point.

CHAPTER IV. THE CAT IN POPULAR TRADITION.

IT is curious to contrast the invectives against the cat, of the poets of the Decline of the Lower Empire, with some of our own popular village poetry. The cat is the nurse’s favourite animal, and the first living creature whose utterance strikes the ear of infancy. The cat is associated with melodies of peculiar rhythmical form; a simple little drama in which the cat plays its part is used to amuse the child and to lull it to rest. A baby falls asleep with a fantastic image of the cat impressed upon its brain.

French popular poets, having observed this, introduced the animal into their verses. A remarkable instance is furnished by the Song of the Cat and the Mice, which is common throughout Poitou. A party of mice having gone to enjoy themselves at a ball and a play:-

Le chat sauta sur les souris,

II les croqua toute la nuit.

Gentil coquiqui,

Coco des moustaches, mirlo joli,

Gentil coquiqui.

[The cat jumped on the mice,

He crunched them all night.

Good crunchies,

Coco of the mustaches, mirlo pretty,

Nice crunchies.]

The cat and the mice are so conveyed to the child by the rhymes that the song is never forgotten.

In the lessons in natural history which nurses give their nurslings, the cat figures with wolves and lions, and the animal belongs to the class of moving objects that vibrate like bells in the sensitive brain of children. The important part played by the cat in the impressions of early childhood is easily explained by its presence in even the poorest household, its marked outline, constantly before the children’s eyes, and its one only utterance, which is easy to imitate and retain in the memory.

Weo might fill a volume with nursery rhymes about cats. What French child has not heard the nursery alphabet:-

A, B, C,

Le chat est allé

Dans la neige; en retournant

Il avait les souliers tous blancs.

[A, B, C, The cat has gone in the snow and come back with white shoes.]

In collection of popular songs of the Western Provinces of France, made by Jerome Bugeaud, we find a verse which is a picture of the animal as well. Here it is:-

Le chat à Jeannette

Est une jolie bète.

Quand il vent se faire beau,

Il se léche le museau;

Avecque sa salive

Il fait la lessive.

[Jeannette’s cat is a pretty animal.

When he makes himself beautiful,

He licks his muzzle with his spittle

And does his laundry.]

cats and mice are habitually brought together by poets and painters for the instruction of children, who, although they cannot reason upon the antagonism between the two kinds of animals, are thus taught to observe the strife between strength and weakness.

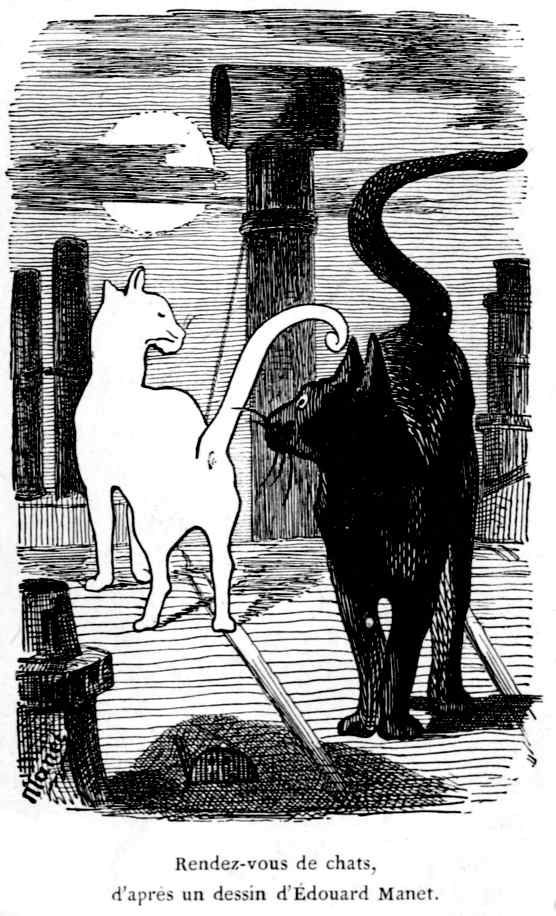

Among the memories of my childhood, I recall with perfect distinctness a very old picture, used as a chimney-board, which represented a dozen cats of every kind and colour, fat, thin, black, white, Angoras and gutter-toms, all collected in front of a music-stand. On the desk lay open, in oblong form, the venerable “Solfège d’ltalie.” The notes were represented by little rats, which perfectly rendered the black and white; their tails accurately indicating the quavers and semiquavers. In front of his companions stood a handsome cat, beating time with all the dignity that befits the conductor of an orchestra; his paw, placed upon the music-book, seemed to scratch the rodents imprisoned between the staves with a spiteful pleasure. Breughel and Teniers have both repeated this conceit.

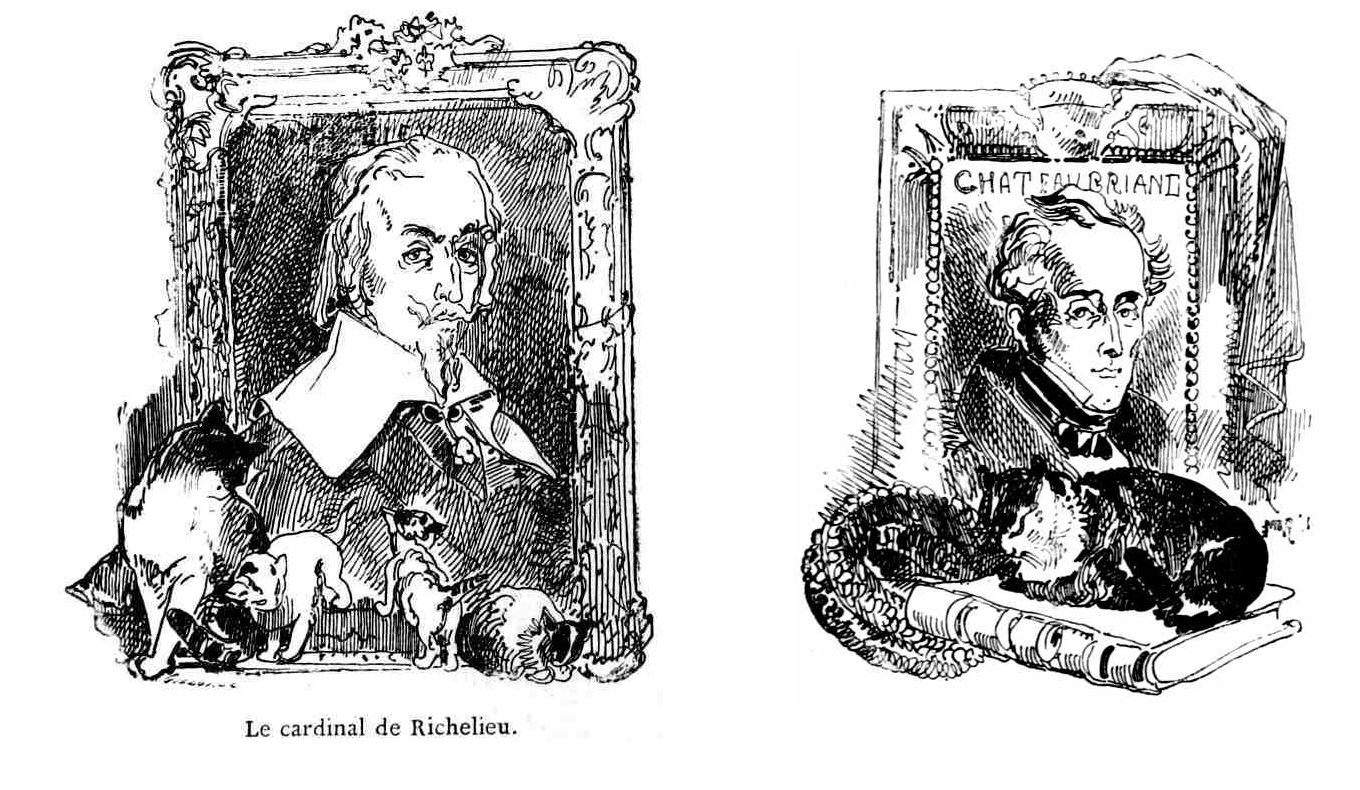

The minds of children were thus filled with stories concerning the cat, and the people preserved the tradition of its cultus. On this foundation a great number of storytellers, as well as our own Perrault, built. From Norwegian, German, and English sources come Puss in Boots, Master Peter and his Cat, Whittington and his Cat, etc. All these stories are derived from popular traditions, which would furnish me with ever so many pages; I shall, however, content myself with one truly fantastic passage from the “Memoirs” of Chateaubriand:-

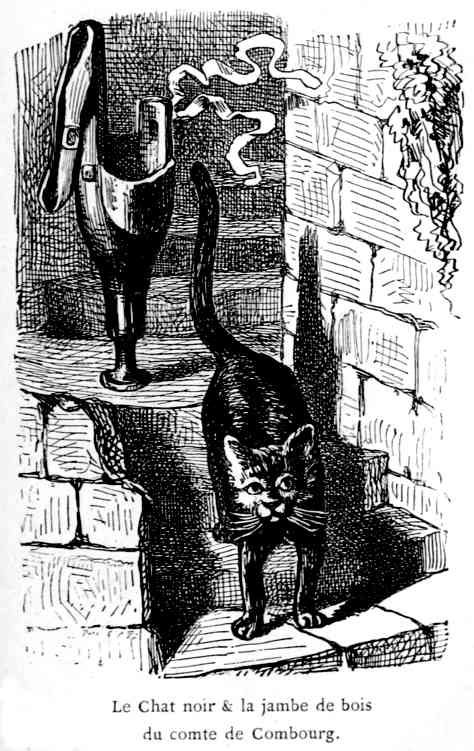

“The people were firmly persuaded that a certain Count Combourg, who had a wooden leg and had been dead three hundred years, appeared at certain periods, and that he had been met on the tower stairs. His wooden leg was also in the habit of walking about, attended by a black cat.”

Here was a story told to a child by a servant. The child was destined to grow up, to fight the battle of life, to be called to the exercise of lofty functions, to become an illustrious person, and one day, when the great man should be musing over his triumphs, his conflicts, his loves, and his political fortunes, the black cat, accompanied by a wooden leg, and gravely walking up the tower stairs, was to start up among the images of the past.

A recollection of childhood is dearer to the high-minded and the gentle-hearted than titles and honours. Under the layers of learning piled up in the brain of great workers and thinkers, there lies, safely stowed away, a nursery song, - for it is characteristic of fine intelligences to remain children in one little nook of their being, and to preserve the impressions of childhood in maturity. This explains why so many eminent men have retained a great love of cats.

CHAPTER V. THE CAT IN HERALDRY, AND ON SIGNS.

The cat, as a strange and eccentric animal, would naturally be included in the heraldic fable-book, which was formed, not only of noble beasts with a definite significance, but also of chimerical creatures whose representation was strongly attractive to the popular fancy. Vulson de la Colombière, a learned heraldic scholar, who gives some cat coats-of-arms in his “Livre de la science heroique," says:-

“As the lion is a solitary animal, so the cat is a moon-struck beast. Its eyes, clear-visioned and glittering in the darkest nights, wax and wane in imitation of the moon; for as the moon, according as she shares in the light of the sun, changes her face every day, so is the cat moved by a similar affection towards the moon, its pupil waxing and waning at the times when that heavenly body is crescent or in its decline. Several naturalists assert that when the moon is at its full, cats have more strength and cunning to make war upon mice than when it is weak.”

I prefer to this interpretation that of Pierre Palliot, another commentator upon heraldry, who concocted the following fantastic legend from the antagonism between the sun and the moon:-

“The cat is more harmful than useful, its caresses are more to be dreaded than desired, and its bite is fatal. The cause of the pleasure that it gives us is strange and entertaining. At the moment of the creation of the world, says the fable, the Sun and the Moon emulated each other in peopling the earth with animals. The Sun, great, fiery, and luminous, formed the lion, beautiful, sanguinary, and generous. The Moon, seeing the other gods in admiration before this noble work, caused a cat to come forth from the earth, but one as disproportionate to the lion in beauty and courage as she (the Moon) is to her brother (the Sun). This contention gave rise to derision, and also to indignation; to derision on the part of the spectators, to indignation on the part of the Sun, who, being angry that the Moon should have attempted to match herself with him,

Créa par forme de mépris

En mème temps un souris.

[Showed his contempt by creating a mouse.]

As, however, ‘the sex’ never surrenders, the Moon made herself still more ridiculous by producing the most absurd of all animals, the monkey. This creature was received by the company of stars with a burst of immoderate laughter. A flame spread itself over the face of the Moon, even as when she threatens us with a tempest of great winds, and by a last effort, in order to be eternally revenged upon the Sun, she set undying enmity between the monkey and the cat, and between the cat and the mouse. Hence comes the sole advantage which we derive from the cat.” [Palliot, previously quoted.]

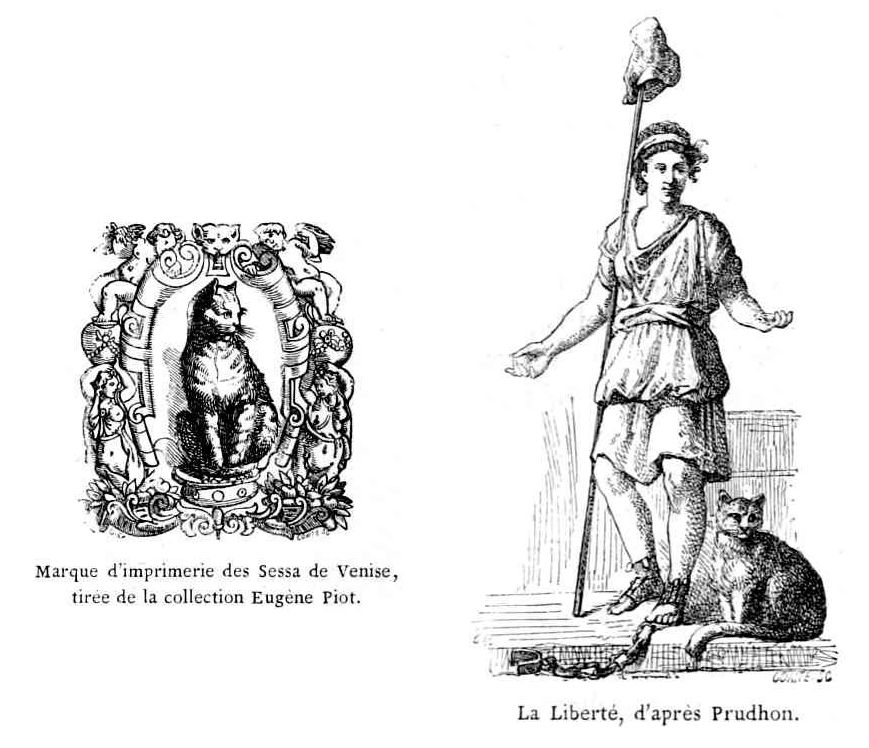

The origin of the cat as a symbol of independence is of remote antiquity. In the Temple of Liberty which Rome owed to Tiberius Gracchus, the goddess was represented arrayed in white; in one hand was a sceptre, in the other a cap; at her feet was a cat, the emblem of liberty. The Vandals and the Suevi carried a cat sable upon their armorial bearings, among the Greeks and Romans.

Those peoples who love legends took pleasure in seeing these fantastic creatures upon the banners of their lords. The ancient Burgundians had a cat in their arms, and; according to Palliot, “Clotilde, a Burgundian, the wife of King Clovis, carried a cat sable killing a rat of the same.” The Katzen family bore on azure a cat argent holding a mouse. The Chetaldie family, in the Limoges country, bore on azure two cats argent. The Neapolitan noble house of Della Gatta bore on azure a cat argent with a label gules in chief. The Chaffardon family bore on azure three cats or, two full face in chief. Many other instances are to be found among the coats-of-arms of European families. [See Champfleury’s “Histoire des faiences patriotiques sous la Revolution.” Paris, Dentu, 1867.]

From the Middle Ages down to modem times we find the cat repeatedly used as the symbol of independence. Thus I account for the “mark” of the firm of Sessa, printers at Venice in the sixteenth century. On the last page of most of their books we find the representation of a cat surrounded by curious ornamentation. Printing was light, and light was enfranchisement. Thus the sixteenth century understood it. How many great minds were persecuted on account of the new invention; how many stakes were lighted by the torch which those free-thinkers held aloft! Italy especially, the country that supplied so many martyrs, did not use the “mark” of the cat without a meaning.

From the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, I find but few traces of the cat used as a symbol of independence. Hagiographers always depict Saint Ives, the patron of lawyers, accompanied by a cat, and for this reason Henri Estienne represents the cat as the symbol of the officials of justice. The French Republic resumed heraldic possession of the cat, and added it to its glorious shield of arms. Over and over again the symbolical figure of Liberty was represented holding a broken chain, and a pike surmounted by a cap; by its side were a horn of plenty, a cat, and a bird escaping, with a string on its foot.

Prudhon, the gentle republican painter, the only artist who gave a mild and tender character to allegorical national faces, has left us a curious symbol of the Constitution. Wisdom, represented by Minerva, is associated with the Law and with Liberty; behind the Law come children, leading a lion and a lamb leashed together. Liberty holds a pike surmounted by the Phrygian cap, and at her feet sits a cat.

With the Republic the reign of the cat comes to an end; nor had it, indeed, implanted itself very deeply in revolutionary heraldry. The pike, the fasces, and the cap of liberty spoke more eloquently than animals to the hearts of the people. It must be admitted that, at this period, the cat was sometimes presented in an unfavourable light; no longer as the symbol of independence, but as that of perfidy. The frontispiece of a vile book, “Les Crimes des Papes,” shows us a cat seated at the feet of a prelate, as an emblem of hypocrisy and treachery.

Our forefathers regarded the cat rather as a singular animal than as one to be loved. This is proved by its frequent appearance upon the signs over shops, with curious legends attached to it, as for instance La Maison du chat qui pelote (literally, “the cat which rolls itself up”), and it evidently engaged the shopkeeping imagination a good deal. I do not allude to shoemakers only, they would of course have Puss in Boots painted upon their shop fronts.

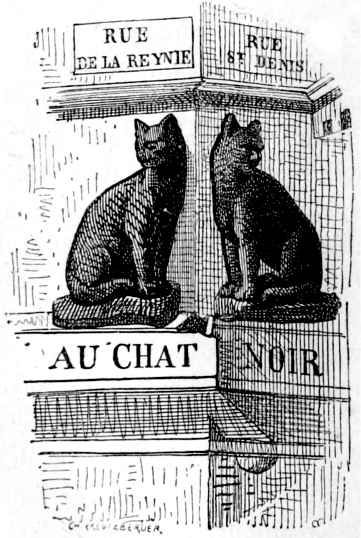

The sagacious profile of the animal, its proverbial cunning, always likened to that of women, its characteristic domesticity combined with independence, all rendered it a favourite object for representation. And at present, when our ancient customs are vanishing, when the pickaxe and the spade are demolishing all that was formerly dear to the bourgeois of Paris, I pause, with a pang of regret for the old “signs,” before one of the last relics of the Lombards’ quarter, the confectioner’s shop which has, perched on its two corners, two black cats.

CHAPTER VI. THE ENEMIES OF THE CAT IN THE MIDDLE AGES.

FOR centuries the cat was looked upon as a diabolic creature. It was contemplative in its ways, so it was regarded as fit company for witches, and invariably figured with the owl among the “properties” of mediaeval alchemists. Sorcerers, and sometimes savants, were burned in the Middle Ages. So were cats.

“It was considered an encouragement to good behaviour, to throw a few cats into the fire at the festival of St. John,” says M. du Méril; and in fact the Abbé Lebeuf quotes a receipt for one hundred sols parisis [Parisian Sols] (coinage of the period), signed by a certain Lucas Pommoreux in 1575, for having supplied for three years all the cats required for the fire on St. John’s Day, as usual.”

The author of the “Miroir du Contentement,” speaks –

D’un chat qui, d’une course breve,

Monta au feu saint Jean en Grève.

[A cat who, after a short run, went into the St. John’s Fire on the (Place de) Grève.]

In the journal of Héroard, the physician, we read that Louis XIII, when Dauphin, interceded with Henri IV for the lives of the cats about to be burned at the festival of St. John [See Appendix]. These cruel deeds of the past were no doubt the effect of the popular terror of sorcerers, and of the cat as their supposed familiar. Fear has always been a strong incentive to cruelty.

From the Middle Ages until the seventeenth century, so much that is legendary is mixed up with the records of antiquity, that even to the present day the most erudite writers have not cleared up the confusion between those elements. It, was believed that the devil borrowed the black coat of the cat when he wanted to torment his victims. Many legends bear conclusive evidence of this; the people firmly believed it, and the better educated confirmed them in their ideas. Vincent de Beauvais relates that Saint Dominick, when he spoke to his hearers of the devil, represented him as wearing the form of a cat.

The large, fixed, green eyes of the animal had something to do with its terribly bad reputation. The owl, and all animals which have fixed eyes, were to be found among the surroundings of sorcerers and witches. The cat was one of the caryatides of the demon-temple; and yet there are legends which relate how cats have faced the foul fiend in an attitude of hostility.

The tradition of the architect who, being unable to complete the last arch of a bridge, called the devil to his aid, is claimed by more than one nation.

"I engage to bring your work to a good end,” says the devil, “if you give me the first soul that shall pass over the bridge.” The cunning architect consents, and sends a cat across the completed bridge. The animal springs at the devil’s throat, and tears him so fiercely that Satan is forced to let this well-armed soul go free. There is a place in the Sologne still called “le Chaffin (chat fin, or cunning cat), in memory of this event.

Other strange and fantastic notions concerning these animals were entertained in old times. French peasants believed that if a cat were in a cart, and the wind, passing over its fur, blew at the same time upon the horses, the latter would be tired out immediately. The country people also maintained that if any part of a rider’s clothing were formed of cat’s skin, his horse would have to carry double weight.

These ideas were fostered by sorcerers, who pretended to cure the peasants of epilepsy by the aid of three drops of blood taken from the vein under the tail of a cat, and of blindness by blowing into the patient’s eye, three times a day, dust made from the ashes of the head of a black cat that had been burned. [Footnote: Half a century ago apothecaries sold a substance which pretended to be the grease of the wild cat, for the cure of abscess, rheumatism, and ankyloses, under the title of Axungia cati sylvestris.]

A clever young writer in the Journal des Débats reminds me, in relation to these sorceries, of a question which Balthazar Bekker put to himself in the seventeenth century. “Why,” pondered that learned man, “s a cat always to be found among the belongings of the witches, when, according to the sacred books, and the Apocalypse in particular, it is the dog, and not any feline animal, that consorts with sorcerers?” To this M. Assézat replies very justly, that “the cat takes the place of the dog in mediaeval times, because the witch replaced the sorcerer at that period.”

The characteristics of womankind lend themselves naturally to the practice of sorcery. Women read the secrets of the heart more clearly than men. An old woman telling fortunes on the cards is more imposing than an old man, and Shakespeare was right in putting the incantations in “Macbeth” into the mouths of witches, not sorcerers.

Poets dealing with the fantastic element combine it with the homeliest realities. The witch travels through the air, indeed, but on a broomstick. The fireside, cat, and the implement used for house-cleaning, are both familiar to old women; therefore it was that the cat, in company with the broom, was regarded as the accomplice of sorcery.

Another story which was told over the fire by night in every country, is that of the woman, a native of Billancourt, who was cooking an omelette, when a black cat sitting in the chimney corner said to her: “It is done; you had better turn it.” The woman was so frightened that she flung the hot omelette at the animal’s head. On the following day she met one of her neighbours, who was reputed to be a sorcerer, in the village street, and observed that his face was burned. She recognized in him the Co of the previous evening. [Footnote: Since then the people of that place have been called the Cos of Billancourt. Co is Picard for cat.]

In former ages these traditions, and many others, were spread abroad among the higher classes. It was probably because of his belief in “the black art” that Henri III always fainted at the sight of a cat.

Fontenelle himself, who was a sceptic, told Moncrif that he had been brought up to believe that not a single cat could be found in the town on the Eve of St. John, because they all went on that day to the Witches’ Sabbath. We can understand from this why the people threw cats that were foolish enough to allow themselves to be caught, into the fire on that day; for they really believed that by so doing they were ridding the country of sorcerers.

The peasants, who adhere with great tenacity to old customs, observed the “diversions of St. John’s Day,” as they were practised in the towns, for a very long time. In the Canton of Hirson, in Picardy, where the “Bihourdi” is celebrated on the night of the first Sunday in Lent, torches and lanterns are carried through the village, at a given signal, and a pyre is raised in the middle of the marketplace, to which each inhabitant contributes his share of faggots. Then begins a dance around the flames; the young men fire off their guns; the village fiddlers are requisitioned; and until recently the piteous mewings of a cat tied to the pole of the “bihourdi,” were heard. Finally the poor animal was dropped into the fire, to the delight of the children, who danced about and cried, “ Hion! Hion!”

That the Flemish people are more humane than the French, we may judge by a statute of so far back as 1618, which interdicts thenceforth the hurling of a cat from the top of the tower of Ypres. That festive ceremony had habitually been performed on Wednesday of the second week in Lent. For a few years past, however, cats have escaped this martyrdom in France.

One cat the less is nothing. One cat the more is much. The animal saved from the fire is the tide-mark of the advance of civilization in country places. Some of the people of the canton have learned to read, and consequently, to reflect. The schoolmaster has come there, and, having gained influence over the children, he has taught them the inhumanity of burning a cat alive. And the feu de joie on St. John’s Day is none the less joyous.

CHAPTER VII. UTILITARIAN ENEMIES OF THE CAT.

ECONOMISTS having demonstrated that all things, although appearing to be worn out and destroyed, find some industrial employment in a new form, certain wise folk undertook so to regulate the actions of men that none of them should remain barren of result. I remember, among other odd ideas, that of an individual who propounded to the architects of the period that the floors of ball-rooms might be so constructed as to admit of corn being crushed by the feet of the dancers, without detriment to their pleasure.

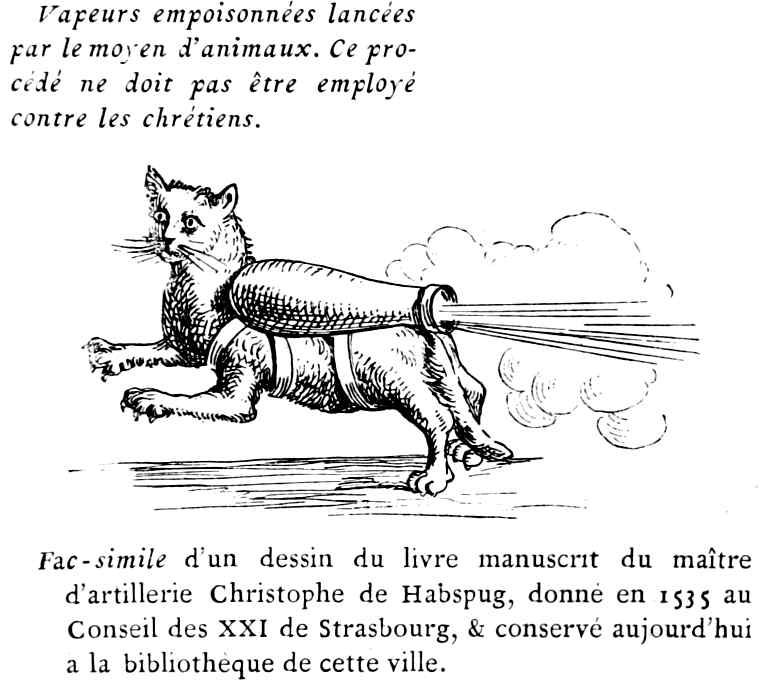

We may class with this pleasant oddity an inventor (he lived in the sixteenth century), who proposed to spread terror among the ranks of the enemy by the discharge of small cannon charged with pestilential odours, and attached to the sides of cats. M. Loredan Larchey, who visited the museums and archives of France in search of unpublished documents for his “Origines de l’Artillerie,” discovered this singular document in the Great Library at Strasburg. We may presume that the sapient invention was not put into execution - historians, at least, do not allude to it.

Other persons also speculated in the cat, not with a view to employing it for useful purposes, but as a popular show. The Middle Ages, prolific of all kinds of oddities, and the Renaissance, with its lasting traces of the barbarism of preceding centuries, were remarkable for the ingenious employment of animals in shows and on public occasions.

At festivals, and on the triumphal entry of kings into a town, animals almost invariably played a part in the spectacle. The spirit of the age is manifested by the fact that educated men, and even savants, tormented the poor beasts, employing them as actors in representations which wore equally singular and useless. Juan Cristoval, a Spaniard, gives an account of a procession which took place at Brussels in 1549, at the fetes in honour of Philip II.

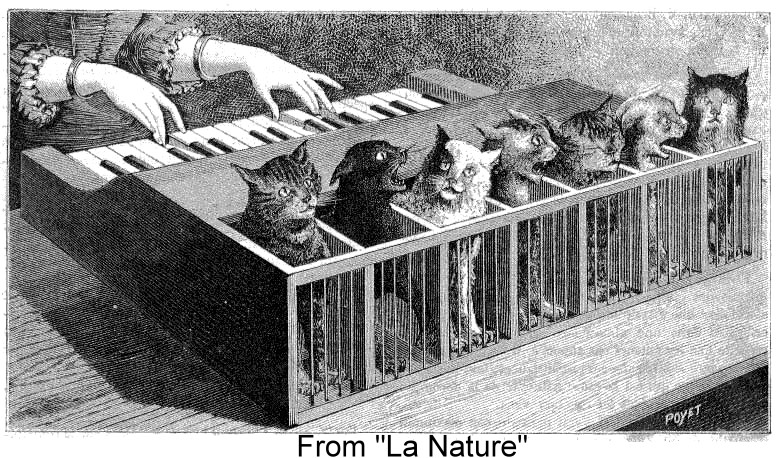

“The ‘body of music’” (orchestra), he says, “was upon a large car; in the middle sat a great bear playing on a kind of organ, not composed of pipes, as usual, but of twenty cats, separately confined in narrow cases, in which they could not stir; their tails protruded from the top and were tied to cords attached to the keyboard of the organ; according as the bear pressed upon the keys, the cords were raised, and the tails of the cats were pulled to make them mew in bass or treble tones, as required by the nature of the airs.”

Live monkeys and other animals, made by curious mechanism with movable joints, such as wolves, deer, etc., danced to this music. “Although,” says the chronicler, “Philip II was the most serious and the gravest of men, he could not refrain from laughter at the oddity of this spectacle.”

Diversions such as these were to the taste of fanatical and bloodthirsty princes. By real, and elevated art, they were not to be moved. It is a just punishment inflicted on ferocity that it is not to be appeased or amused by means of poetry or music.

Turning from the cruel king, Philip II, to men of science, we find that Pere Kircher amused himself during his whole life with musical oddities. The cat-organ which he describes, differs, however, from the mechanism invented by the Flemish people in honour of Philip II. Instead of cords which pulled the cats’ tails, Kircher speaks of spikes fixed at the end of the keys, which prodded the poor animals, and made them mew piteously. The result produced by this barbarous invention can hardly have been very agreeable.

Another learned individual of the seventeenth century, deriving his inspiration from the labours of Pere Kircher, undertook to popularize the invention of the cat-organ. Gaspard Schott adds a drawing of the machine in which the cats are shut up, to the chapter of “Magia Universalis” entitled “Felium Musicam exhibere.” This machine is a long box, with an aperture through which the heads of the cats protrude. The wretched animals, tortured by imprisonment and the pain inflicted on their tails (their most sensitive part), were infinitely amusing to pitiless spectators of this atrocity.

The popular cat-organ does not seem to have been very successful. The cats, on coming out of their cellular prison, must have been rather difficult to get on with. It is not their way to lick the hand that strikes them.

There were other people who exhibited “learned cats” and “cat musicians” in public. A woodcut, of the most primitive order of art, represents a showman, with cats crouching upon his head and shoulders, standing before a table on which are three others. The latter mew from written musical notes in the music-books open before them. Three instrumental musician-cats play on the mandoline, the viol, and the bass-viol. At the top of the woodcut is the following, printed in rough type:- “La Musique des Chats”

On a scroll is written: “Ceans l’on prend pensionaires, et le maistre va monstrer en ville.” [Footnote: Pupils (also boarders, or patients) are taken here, and the Master shows (exhibits) in the town.”]

The costume of the showman and the cutting of the block indicate that this representation dates from the seventeenth century. I have seen another drawing of the same subject, but not by the same hand, with the signature “P. Gallays excudit.” Copper was selected this time as a medium for immortalizing the musical talents of the performing cats. All the details are similar to those in the first woodcut, but treated in a less barbaric fashion. Beneath the copperplate drawing are the following lines:-

Vous qui ne sauez pas ce que vaut la musique,

Venez-vous en ou'ir le concert manifique

Et les airs rauissants que iaprens aux Matous.

Puisque ma belle roix ren ces bestes docilles,

Je ne scaurois manquer de vous instruire tous

Ni de vous esclairsir les nottes difficiles.

[Footnote: The following is a translation of the showman’s doggerel: “All you who know not how charming music can be, come and listen to this magnificent concert, and the ravishing airs which I teach to my Tomcats. Since my fine voice can render these animals docile, I surely could not fail to instruct you all, and to make you master the most difficult notes.”]

We find, then, that at the end of the seventeenth century, a man existed who was half mountebank, half animal-doctor (céans l’on prend des pensionaires), and that he did a sufficiently good business with his four-footed musicians to enable him to indulge in prints to puff his profession. No doubt, this woodcut was an advertisement placarded in the streets of Paris.

Notwithstanding the extreme difficulty that must have attended the teaching of any kind of music to animals of so independent a nature, the spectacle found imitators. Valmont de Bomare, the naturalist, saw a showman at the fair of Saint-Germain, in the eighteenth century, who had stuck up over the door of his booth a placard with the daringly original word “Miaulique ” in huge letters. This meant “cat-music.” Inside the booth were cats upon a table, a music-book was open before them, and at a signal given by a monkey, who acted as conductor to the orchestra, they all mewed in concert.

In a newspaper of 1789 there is an account of a Venetian who was giving “cat-concerts ” in London at that date. The animals obeyed the slightest sign from their master, but it must have taken long years to produce this poor result.

One wonders what the vulgar crowd find to amuse them in the spectacle of “learned” monkeys, dogs, or cats. How much suffering must the animals have undergone to arrive at their “learning,” especially those who, as the poet says, can not

Au servage incliner leur fierte.

[Incline their pride to serfdom.]

In the faces of these poor creatures we may read the permanent result of this teaching; they look constrained, pitiful, and sad. The frippery in which they are decked out worries them. They are no longer free, they hardly dare to look in the face of the showman, who fixes his hard eyes upon them, and their timid glances are furtive and dim. They are commanded to do a “trick,” and they execute it with the dread inspired by the remembrance of the merciless stick that is always threatening them. Their bodies are pitiful all over, their ears and tails, that ought to be silky and carried with pride, hang down in the misery of constant terror.

The Chinese, wiser than we, never endeavour to make any animal do feats which are contrary to its nature. Of the cat they make a clock. Pere Hue relates that he met some native naturalists at Pekin, who showed him in what fashion a cat may fulfil the purposes of a timekeeper. “They pointed out to us,” says the missionary, "that the pupil of its eye contracted gradually as noon drew near; that at noon it was like a hair, or an extremely thin line, traced perpendicularly on the eye; after midday the pupil began again to dilate. When we had attentively examined the cats in the place we concluded that it was past noon; the eyes of all presented an exactly similar appearance.” The Chinese are true utilitarians.

CHAPTER VIII. ADDRESSED TO UTILITARIANS.

I went one evening into a cafe concert in rather low spirits. Neither the fascinating females nor the gifted tenors, neither the orchestra nor the public, awakened any interest in me, until there appeared upon the boards a pale, thin, shabby person, with dabs of red upon his nose, and an old felt hat upon his head. This man was of lugubrious aspect - he was the comic singer and low comedian.

He sang a song about cats; the first part of it was a play upon the words cha-pon (capon), cha-meau (camel), cha-loupe (sloop), and cha-piteau (capital). At first this feat of humour did not dispel my melancholy, but as the performance proceeded, and the jester invoked the cha-pelure (hats) of the bakers, the cha-pelles (chapels) of the churches, the cha-cals (jackals) of the desert, and the shakos of the soldiers, I became infected by the amusement of the public, who were highly entertained.

[Footnote: This play upon words cannot be translated, nor can the following ingenious passage:-Il avait connu un pacha qui fasant des siennes avec des chats; l’un d’eux malheureusement s’appro-cha; il atta-cha, l’embro-cha, l’eplu-cha, le tran-cha, le ha-cha et le ma-cha. Puis vint un juge qui s’effarou-cha, se pen-cha, cra-cha et se mou-cha.

Le juge rentrait dans son cha-let,, otait son cha-peau, demandait son chasse-mouche déposé sur un cha-ssis, et finalement traitait sa servante de cha-braque pour avoir laissé brùler les cha-taignes.

Le public se tordait.

- Messieurs, disait le comique, je n’aime pas qu’on me cha-maille.

Il falsait une serie d’ente-chats, etait pris d’un violent rhume, et, disait-il pour terminer, je crains qu’aucun médecin ne puisse me guérir de matou (Ma toux = my cough, Matou = tom-cat.)]

I acknowledge, with shame, that my depression vanished; this avalanche of puns was too much for it.

I doubt whether any animal in natural history has contributed so largely as the cat to the development of French humour.

CHAPTER IX. TO THE ENEMIES OF THE CAT - SPORTSMEN.

At cottage doors in country places, we see poor, wretched animals, thin and miserable, with rough, dirt-coloured coats, casting furtive glances from their timid eyes at the slices of bread and butter which well-fed children eat in their neglected presence. These are cats; they know too well that not a crumb will come their way. At family festivals, during which the peasants devour whole pigs, the cat does not dare to pass the threshold of the door - kicks would be his sole share of the feast.

It may be said of these animals, as Diderot says of those of his native town: “The cats of Langres are such thieves, that even when they are taking something that is given to them, their furtive way would make one think they were stealing it.” It is not at Langres only that cats have this thievish and suspicious look; for “Langres,” say “country parts” - the observation will be applicable to every place in which a barbarous prejudice against those animals reigns.

In winter, when a bright fire of fir-cones is crackling on the hearth, the dog stretches himself lazily in front of it, forbidding the approach of the cat. It is only in large farmhouses, where plenty extends from the human to the brute inhabitants, and maintains a semblance of harmony between them, that the cat timidly draws nigh to the dog, dreaming his hunting adventures over again as he lies at his master’s feet; but where poverty dwells there is no safety for cats, who are regarded, notwithstanding their indisputable usefulness, as less the friends of man than the dog.

No one knows, and no one cares, where the village cat assuages its hunger or quenches its thirst. The female cat, when about to bring forth her young, hides herself in the darkest part of the garret; and if she falls sick, she ends her days in some corner, unnoticed and unregretted.

Country people are too often hard and unfeeling towards animals and old people. They call them “useless mouths!” Cats are obliged to bestir themselves actively to escape starvation. Nature has adapted them to hunting purposes; hunters they inevitably become, and thus they have aroused the wrath of their dangerous rivals, men, who wage a cruel and unjust war against them.

“I never meet a prowling cat,” says M. Toussenel, “without doing him the honour of shooting him.” And yet, the man who says this has written charming things about birds! Nor is he satisfied with killing the poor cats, who are only seeking their livelihood; he must also urge all sportsmen to imitate his cruelty: “I strongly advise all my brethren of Saint Hubert to do likewise,” adds this follower of Fourier. It is not by such counsels that M. Toussenel will win disciples to the doctrines of the Utopian philosopher.

Without degenerating into silly sentimentality, we may ask - how can any man entertain feelings of this kind? Antipathy towards an animal is no excuse for cruelty. It inspires one with a horror of those brutal sportsmen who think that anything is allowable to them because they carry a gun and a licence, when we find them wantonly shooting harmless cats.

The article which M. Toussenel devotes to the cat, does not substantiate any serious grievance against an innocent it animal on the part of the Phalansterian. “A love of cats,” says the Fourierist sportsman, “is a vice of inferior minds; a man of good taste, and with a keen sense of smell, has never had, nor could he have, sympathy with a beast passionately fond of asparagus.” [Note 2017: Contrary to popular belief, all people produce “asparagus pee,” but not all people are able to smell it.]

If all the human beings who are fond of asparagus were to be shot on principle, France would speedily be decimated. The cat likes those herbs which are necessary to its health. In the country, the animal, after having made its toilet, proceeds to chew grasses and plants. This green stuff fails him when he is shut up in a house; is it not, therefore, natural that in the spring, the cat, like his master, should like to eat of a delicate and delicious vegetable? There is no plea for shooting him in that charge.

Another grievance of M. Toussenel against the domestic cat is the crossing of its breed with the wild-cat. If we are to believe him, the race of wild-cats would have been extinct before the present time if it had not been perpetuated by this means.

CHAPTER X. ADVICE TO SPORTSMEN.

Sportsmen are inclined to indulge in the pleasures of the table. There it is that they relate their exploits, and brag of their prowess. Certain sportsmen are famous for culinary recipes. I, also, have studied the ordering and arrangement of a repast elsewhere than in the Household Cookery Book (“Cuisinière bourgeoise ”), and I should like to draw the attention of sportsmen to a particular application of the intelligence of the cat, which is not without utility, and will doubtless raise the animal in their esteem.

Cooks are in the habit of preparing butter for breakfast by rolling the pats with a knife which makes a pattern on it. By merely leaving a pat within reach of the cat, this operation will be much better performed than by the cook. Pussy’s rasp-like tongue will trace charming designs upon the butter.

CHAPTER XI. THE FELINE RACE IN STATISTICS.

THE domestic country cat has other enemies, more inveterate, if possible, than the sportsman. We find a terrible indictment of the poor animal in the “Journal d’Agriculture pratique.” According to the editor of that periodical, the greatest destroyer of game is the cat. At night it roams about the country, and watches, more patiently than the fisherman watches with his rod and line for his finny prey, the hares and rabbits that come out to play in the dark. The bounds of the cat are, if we are to believe the accuser, as terrible as those of the panther; with one spring the animal falls upon the long-eared creatures, and it is imputed to it as a crime that its claws penetrate their flesh like a harpoon.

A nightingale begins to sing; suddenly the music is mute - both nightingale and song have fallen into the jaws of the cat.

Peasants take ortolans in snares which they set in the vines; when they find feathers only lying beside their engines of destruction they know that the cat, who also has a liking for ortolans and beccaficoes, has been beforehand with them. The cat does more damage in its proper person than those devastators of the poultry-yard, the ferret, the weasel, or even the wolf. The immense advantage of the cat over these beasts of prey, is that it carries on its operations in peace, without exciting suspicion. It is at home.

The least noise in the interior of the farm alarms the fox stealthily prowling about the out-buildings. The corn must be pretty high to afford covert to a fox, but a little shrub will suffice for a hiding-place for the cat. Crouching amid the foliage on the branches of the trees, it commits greater ravages among the birds’ nests than all the ill-disposed boys in the parish. The cat has strange magnetic faculties; its green eye fascinates birds, and makes them drop helplessly into its jaws.

The dog inspects a field of corn with his nose, and the rapidity of his movements prevents him from finding all the birds hidden in the furrows. The more reflective and deliberate cat ferrets minutely into every corner; its velvet paws enable it to approach its prey quite noiselessly. Out of a covey of young partridges not one will escape. The delicate and acute ear of the cat detects the cry which the female hare utters when she wants to collect her young. At this signal the cat arrives on the scene, and the leverets are collected in its stomach.

The hare defends itself against the wolf, and against the rabbit, its most cruel enemy; it seeks protection in the vicinity of man. There is no animal who would be more easily domesticated. The company of cows in the cow-house is not displeasing to the hare, and sometimes a servant, going to the cellar to draw wine, catches sight of its big ears; but the cat is there, and it pitilessly devours the animal who has come to claim hospitality at the farm.

According to the same witness for the prosecution, the fox, the ferret, the badger, and the wolf, are absent from certain countries, and if the kite and the hawk are seen, it is only to appear and disappear at the equinoxes. But none the less do hares and rabbits vanish as if by magic! The enchanter, according to the indictment, is no other than the cat, who eats on an average ninety leverets out of every hundred in the year.

Nevertheless the country cat is thin and miserable. I have explained the cause of its melancholy looks. It gets more kicks than meat, it is despised as much as the dog is cherished, it never receives a caress, it is thrust aside by rude, coarse natures, who do not comprehend its wealth of affection, and the cat suffers profoundly from wounded feelings. There are no friendly legs against which it may rub itself, and the harsh voices of the country people sound rude to the exquisitely delicate ear of this finely organized animal. In its youth it mewed gently to gratify its longing, but no one heeded it. The cat has become misanthropical; its best qualities are injured, It seeks a healing balm for its melancholy in the solitude of the woods and fields; neither the pastures nor the forests can restore its cheerfulness; the village cat is sad.

It is difficult to account for the thinness of the animal, and at the same time to believe in the misdeeds with which the “Journal d’Agriculture pratique” charges it. No doubt life in the woods is less favourable to personal appearance than life in town; a well-warmed apartment makes the coat shine better than exposure to every wind; but, surely, the abundant game which it is accused of destroying ought to have some effect on the stomach of the animal?

We have seen the statement of the depredations committed by cats; the statist is harder upon the creature than a State prosecutor. The number of rural houses in France is set down at six millions. In every house in each village we may reckon one cat, generally more. Here, then, are several millions of beasts of prey, destroyers of game - consequently, six millions of cats at least to be exterminated. The editor of the journal, who has marshalled these facts and figures, enjoins the rural proprietors to prevent their farmers, vine-dressers, shepherds, millers, woodmen, and labourers, from keeping cats in their houses; he too, like M. Toussenel, would settle the matter promptly by powder and shot.

These statistics make no account of the preservation of grain. Rats, mice, and other rodents seem never to have existed. It is not admitted that the mere presence of the cat in a house suffices to banish the destroyers of corn.

Their prejudices mislead all the enemies of the feline race. It is not enough to draw up an act of accusation; the accused has a right to have the witnesses for the defence heard. Has the mission of country cats been sufficiently studied, that they should be so readily condemned? That they protect the storage of grain, is proved by their battles with rats;-but do they not also make war on other animals, on stoats and weasels, for instance? [Footnote: M. George Barral says, in the “Journal d’Agriculture,” that the country people might, by better treatment, turn what one of his collaborators, a member of an acclimatization society, calls the “criminal instincts of the domestic tiger” to their own advantage.]

The reports of the Conseils généraux upon noxious animals state that at a certain period a price was put upon the heads of sparrows. A year later it was discovered that those noxious birds might be useful, and the magistrates were enjoined to proceed against any persons who took their nests. Councillors of State, naturalists, prefects, statists, all contradict each other; that which one department approves is condemned by its neighbour.

We lack attentive observers, and philosophers who might wrest her secrets from Nature. Every living creature fulfils a mission: that mission is hidden from us. We are more destructive than the animals whom, in our ignorance, we accuse. In a “Noel” of Franche-Comté, an old man is brought to bay by the logic of a child, and gets into a rage in order to close the discussion.

“Who made the stars? ” asks the child.

“God,” replies the old man.

“And the sun?”

“God. Partridges, snipe, hares, chickens, turkeys, and leverets are also the work of God,” continues the old man.

All things which strike the eye of childhood are enumerated by the poet, who, at each answer, puts the name of the Creator into the old man’s mouth.

“Tell me, if you please,” asks the child, at length, “is it God who has created fleas and lice?”

“Little pratebox,” says the old man, “if you interrupt the story again, I will rap your knuckles with the tongs.”

CHAPTER XII. CATS IN COURT.

Cats are frequently involved in grave testamentary questions. More than any other animal, they occupy the attention of the tribunals of civil law and police. There we find evidence of the profound affection which certain cats have inspired. It will be objected that cat-lovers are old bachelors, old maids, or persons of mean condition, who awaken but little interest; and yet I might plead for such a sentiment on behalf of the old maid whose lack of dowry has prevented her from gaining a place in society. Poverty has made her timid, her shyness has condemned her to solitude, and, having lost her illusions, having no hope of ever possessing a husband or children, she concentrates her affections in a cat, her only friend. If the animal does but respond by a look, by a purr, the old maid forgets her sadness and her solitude.

It is not only among ordinary people that the cat inspires affection. The famous Lord Chesterfield left life-pensions to his cats and their offspring. Bequests of a similar nature made to cats in the presence of a notary have often been disputed by greedy heirs, who take advantage of their relative’s affection for animals to endeavour to “interdict” the testator by accusing him of insanity.

'These “interdiction” suits bring many strange things to light. They pitilessly expose the wretchedness of poor human nature, its meanness, its misery, and the misfortune of ill-balanced minds. We are also struck by the absence of a sense of family honour which is involved in these painful disputes, when, to set aside the wishes of their aged relatives, the rapacious disputants will invoke justice to declare them mad!

Some years ago a suit was heard which made a great sensation. A brother demanded “interdiction” against his sister, because she “had had a tooth of her deceased cat set in a ring." This, according to her brother, constituted a veritable act of madness and imbecility.

M. Cremieux pleaded for the friend of cats.