THE BOOK OF CATS.

By Gustav Michel.

Second low-cost edition. Price 4.50 marks.

1870. Weimar. Published by Herm. Weissbach.

Opinions of the Press.

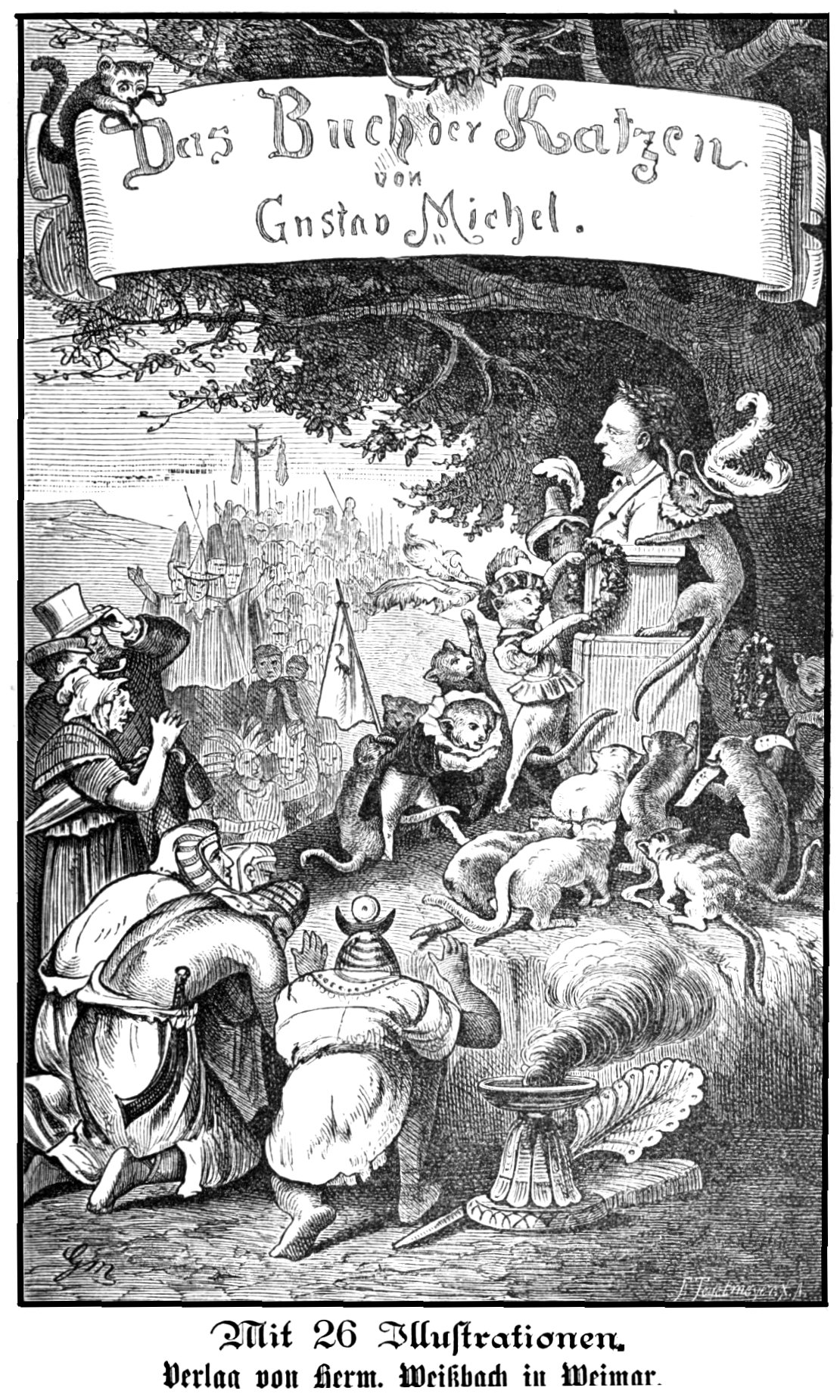

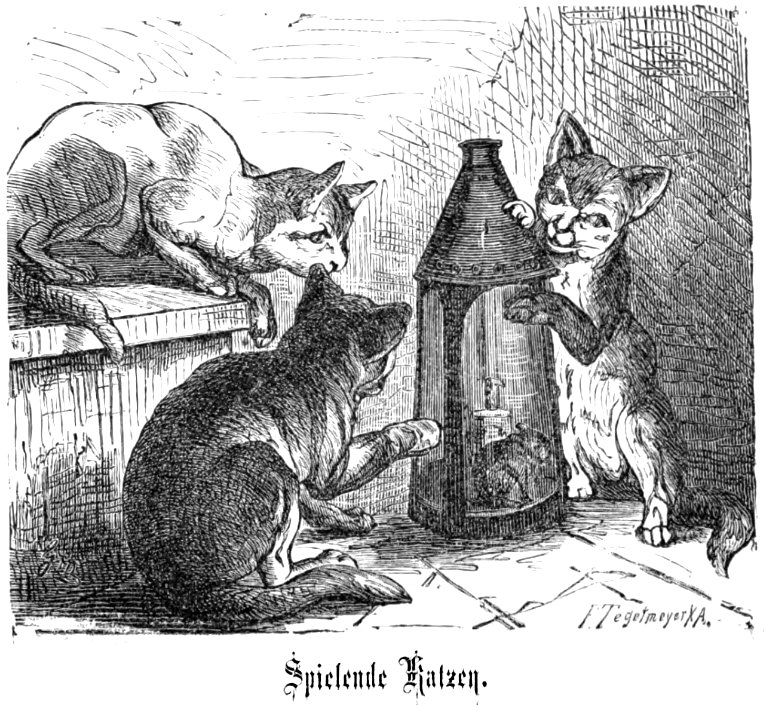

(Nature.) The book, written by painter Gustav Michel in Weimar with great erudition and artistic feeling, is a sort of hymn to the cat, which everyone who has ever lovingly stroked a kitten's fur in their youth or later should read at least once. In and of itself, the theme is simply: The cat in history, legend and art, as well as its virtues; but the author does not write his variations in asthmatic flowery classicism, but prefers to depict them smelling of both roses and of ammonia, which shakes the senses powerfully. So all of his cat pictures, which he also decorates with mischievous woodcuts in the old Nuremberg style, are as fresh as the spring and their colours enliven the reader like moss and meadow green. Nevertheless, this one has no need to fear romanticism in "Kater Murr" or "Puss in Boots" style, and this time the scientific truth does not appear in a long toga, but in the light veil of teasing and charming poetry. All credit to him if the author did it consciously, for we value a good composition and believe that even a scientific book should be a work of art, something we dear Germans pay too little attention to, because we always think that the subject must speak for itself, which it does not, or only rarely does. We credit the author for not allowing himself to be carried away, like other so-called natural science writers, into a perfidious, supposedly witty, depiction that injects something into a subject that is not actually there. Fortunately, his scientific conscience prevented this and caused him to meet even the strictest requirements in 78 footnotes. A. M.

(Literary communication.) - A written defence of the feline race! Doesn't that sound so outrageous and strange that curiosity alone must make this remarkable book worthy of our attention? - The author teaches us in the most inspiring way about the rich fortunes of his subjects, "with a cheerful and keen eye" - sometimes serious, sometimes bubbling with humour, but always instructive, entertaining and scientifically thorough, the author pursues his goal. The Book of Cats is the first work on this subject in our language and is so original in its style that it deserves not only the thanks of cat lovers, but also of science, which thereby receives a work that it has previously lacked. M. M.

Reprint prohibited. Law of June 11, 1870. Right of inspection reserved. [expired]

FIRST LETTER.

A spectacle for the gods

To see two lovers. -

But may I ask, I ask for one thing!

Let me have the best cup of wine

in pure gold.

Singer, by Goethe.

When I think of those days, dearest, those beautiful days on the Rhine, our Rhine, with its vines, its blue sky, its green mountains and fragrant valleys; when I think of that beautiful moonlit night when I said farewell to you and the mountains of my homeland: it almost seems to me as if it had been a dream, told of a lovely mermaid, as if old Father Rhine had sung his most beautiful fairy tale to his departing son. But it was no dream! I really did say goodbye to you, with a pounding heart I timidly asked to be allowed to send you letters, many letters, and you laughed as only you can laugh. "You want to send me letters, lots of letters," you said, and your beautiful eyes looked down on me compassionately like stars from above - "and what do you want to write?" Oh, my dearest! I want to write about everything that moves my heart, about all the hot pangs "Which will soon burn it out and leave it empty, like Mount Etna once did., you interjected, "so I ask you, beloved, write about everything that moves your heart, but above all - about your cat." With these words I felt as if the earth would swallow me up. The mountains danced around me; the castles leaned down into the valley, and the Rhine embraced them like a white snake. - My senses became confused, I closed my eyes, and when I looked up again, everything was still and motionless, only in the distance on the old walls a bright gown shimmered, and the nightingales sang their sweetest songs. "Eleven o'clock! Eleven o'clock!" called the night watchman at my side, "and the Kronenwirth has the best wine," he added quietly. -

You can see now, dear lady, that although the beautiful location on the Rhine has long since vanished and my heart has burned empty like Etna once did, your written wish has nevertheless remained unforgotten. Things have become serious with the cat, serious without any real merit on my part; for, contrite with shame, I confess the enthusiasm of that hour of farewell, i.e. the enthusiasm for my cat, had long since evaporated when one day or one evening, chance presented a serious warning to me.

You know the saying about small causes having great effects; how a soap bubble led to optics and a falling apple led to gravity; that the steaming tea kettle led to the discovery of the enormous power of steam, that the twitching frog's leg led to the discovery of galvanic current, and that Bismarck discovered the German Empire; but you certainly have no idea how great ideas are connected with my cat. Now listen and have pity on your poor friend who, like Goethe's sorcerer's apprentice, can no longer dismiss the spirits he summoned.

It was an autumn evening. Outside, the storm roared, and the mighty, ancient linden trees, which embraced the house as if with protective arms, groaned under its grim force, while it snapped branches and whipped withered leaves around like snowflakes in the air. It chased dark masses of clouds before it, which towered threateningly and poured down icy rain. Deep night lay over the earth, not a friendly star was visible, and the roar of the storm sounded like rumbling thunder.

In such phenomena, poets see the "unleashed wrath" of heaven; the ordinary mortal, however, speaks of bad weather, which is usually followed by sunshine. So what does it matter to us, one or other of my friends may have thought, it is all the more comfortable in a warm room, with a slim-necked bottle and a fragrant dish. - And indeed, my dearest, how quickly one forgets the day's storms when, in the company of dear friends, one recalls in lively conversation the many journeys and forays; when hour after hour passes in cheerful enjoyment, comfort and cheerfulness, Bacchus and the night let the lightning of wit shine. How wonderful is such a round table! Is it not a feast for body and soul, whose epicureanism is revealed by lips and palate; the culinary side is merely a vehicle for intellectual social nourishment, friendship rules the hearts, humour and wit are the best delicacies, which not only refresh while one is enjoying them, but long afterwards when you think back to them.

So we sat together happily, light-hearted and cheerful, and had already cracked open many a bottle, when we were suddenly startled out of our divine mood by a long drawn-out cry, like that of a child. A child's voice! A child outside on such a stormy night! We jumped up from our seats, rushed to the window, tore it open . . . and above us sat a black tomcat. Oh, my dearest! these pale, mortally frightened, ashamed faces struggling to keep their composure, and merrily mad faces, and in the middle of the room the tomcat meowing with delight - is this not splendid material for history painters?

But cold horror soon gave way to a burning indignation. "Out," cried the chorus, "out with the black monster," and hot-blooded, busy hands grabbed stick and umbrella to chase the poor stranger away; the cat, however, thought that I was his protector and meowed imploringly up at me, and my warm heart, as you know, dearest, was conquered. A strangely eloquent spirit overcame me; I spoke fiery words in defence of the oppressed, and when they tried to dismiss me and my arguments, I cried out that I would not only defend this tomcat, but defend all the tomcats of the world, that I would write a defence of the feline race, that I would . . . Derisive laughter interrupted the flow of my speech, but just as there are songbirds that stay silent while all is quiet around them, but sing louder whenever they have to strain to be heard, so there are many people who are taciturn when all is silent, but who become more and more talkative when others are less inclined to listen to them; like canaries, they try to outdo one another with their voices as the noise around them becomes louder.

That's what happened to me. The opposition made me a cat panegyrist, and what some people may not understand is that I like this position. And why shouldn't I? Homer found it worthy of his muse to write the war of the frogs and mice, Virgil wrote of immortality of the mosquito, Lucian of the fly, and other famous people of the rooster, beauty and the flea, so why, by the eternal stars, should the cat not find its bard; its story is no less brilliant and remarkable than that of Odysseus and Helena!

This awareness made me set to work with glee. I searched through old, yellowed folios, combed through the literary treasures accumulated by scholarship, but had the unpleasant experience that the cat is rarely mentioned in our German literature. The French have treated this subject with deference for a long time, but it's probably the English, most of all, who seem to have a special love for this animal, which, in my opinion, can be explained scientifically. The cat is said to have electrical powers, and the chapter on the properties of electric bodies in Experimental Physics teaches that if one places a non-electric body near these bodies, or, as one would say, in their atmosphere, it also becomes electric. I therefore suspect that since Albion's sons, in their watery nature, were not very electric from birth and have little cat-like speed to show, but mostly walk along as if they had swallowed the pole of their national flag, it is precisely the transfer of cat-electricity that can be regarded as the bringing about their love of cats. -

During these excursions, thirsting for knowledge, it soon became clear to me that most of the very few authors who have written about cats - among them authorities in the field of zoology - harbour understandable prejudices against this animal, and in many cases continue to circulate traditional myths without their own judgment. The common sayings and opinions that cats are less intelligent and loyal than dogs, and are more devoted to the house than to their owner, have become almost universal. In particular, since the Middle Ages, the Christian view has regarded the cat as a symbol of deceit, malice and low flattery, but the great falseness of this view can be seen by anyone who observes a domestic cat, not in its random appearance, but in its development. Nor can one speak of a cat without referring to it as cruel', without considering that if the word cruel' is applied to a creature without reason, one may just as rightly assert that all animals are cruel, from the camel to the nightingale.

It is mostly only the more perfect animals that are accused of cruelty and are blamed because they think and act like humans; however, they are never cruel to a human degree or in a human sense. Even the tiger is not cruel; only humans have this quality. People unscrupulously cut off frogs' hind legs and throw them back into the water without killing them completely, they boil live crabs and mussels, they skin live eels, and are hunting, cockfighting and boxing fights noble virtues? It is a curious fact that all peoples who have not yet been touched by civilization treat the animals whose services or company they require very kindly and humanely, and as a result there exists between those primitive people and their domestic animals a bond which is highly worthy of the respect and imitation of civilized people.

The Indian in the American savannas and prairies devotes the very best care to his mustang, speaks to it as if the animal can understand him, and in return achieves an admirable intelligence and efficiency in the animal. Even among the Eskimo, who has only reached the lowest level of education, we always find the same gentleness towards his running animals pulling his sled across the endless expanses of ice and snow, and here, as everywhere where treatment by purely human means seeks to awaken the understanding and affection of the domestic animals, greater intelligence is shown in these and there is no trace of life-threatening excesses, such as we have the opportunity to observe daily in Germany. If we look at the relationship between man and his domestic animals, we find the most pleasing results, as a rule, only in regions where the enervating artificiality of education, with all its harmful effects, has not yet broken the dominion of nature - on the plains, among farmers and shepherds, and among the inhabitants of the mountain regions - there one finds the most enduring, most willing and most capable animals. The intelligence of sheepdogs is world-famous, and now - who has ever seen a shepherd mistreat his dog, the friend who guards and helps to guide his flock?

And now I ask, why is the cat mistreated in such an unjust manner, when it is of such great value to the house? One should not be angry with the cat because it is sometimes shy and unfriendly, it is just how it was made; for it is always man, with his various living conditions and character traits, who has a decisive influence on the character of domestic animals, so that the same types are found in a completely different form among primitive peoples, where, as mentioned, they are treated better.

It is indeed astonishing how much the overall expression of animals can change, improve or worsen; good treatment, good care and educative words ennoble them, and in young animals both their external appearance and their mental nature can quickly improve or worsen through contact with people, so that one could also apply the proverb: Tell me who you associate with and I will tell you who you are! Good, intelligent people can only have a good influence on animals and raise good animals, and the more one spends time with the cat, the more its attachment to the family becomes, but the more one leaves a cat to itself, the more its attachment to its birthplace becomes.

However, dear friend, I will report on all the hardship and injustice that Mrs. Pusscat has to endure elsewhere and will now try to start at the beginning.

According to the famous Englishman Dr. Johnson, the cat is an animal that catches mice. This learned definition, I fear, will not satisfy you; nor will the views of Ross, who claims that the English word "puss" is derived from the Egyptian "Pasht" or from the Latin "pusio". The word "Katze" commonly used in German, English "cat", Danish and Dutch "kat", Spanish "gato", Italian "gatto" are, as in all Romance languages, with the exception of Wallachian, derivations of the Latin word "catus", which was first used by Palladius for the new domestic animal that came from Egypt and has since then, like the Egyptian animal itself, spread not only to all European peoples, including the Basques, Finns, and modern Greeks, but also far into the Orient to Asians of various tribes.[1])

The cat is also called "Mietze", Italian micio, Slavic maceka, as a peculiar name, and just as Mietzchen means little Marie, and Bohemian macek means little Mathias, in Russia the cat is called "waska", i.e. little Basil or "mischka", i.e. little Michel (sic!). The oldest name for the cat is probably to be found in Egypt. Church records in the Louvre give it as Mau, Mae, Maau, but some Egyptologists have read "Chaou" on certain monuments. It is possible that our German word "miauen" comes from the Egyptian "Mau, Maau". -

[Translator's note: the following section discusses words that contain "Katze" [cat], in particular Katzenjammer - "yammering cats" - which means both "hangover" and "depression." Kater can refer to a hangover as well as a tomcat.]

In thieves' language, a lady's muff [hand-warmer] is called a "cat," and "to free a cat" is the same as stealing a muff. The English army knows a cat with nine tails, and the significance of a corpulent money-purse [Geldkatze] is probably generally understood; as is the significance of pretty chambermaids [Kammerkatzen]. A constellation in the southern hemisphere under the neck of the water snake, discovered by Lalande, is called the cat; Katzenbuckel is the highest mountain in the Odenwald, and Katzenveit in Voigtland [in Namibia], is a mountain spirit who is a dwarf, like the Katzenbutz.

According to the Linnaeus system, the lion, the Asiatic tiger, the leopard, and the American panther are also called cats; some other animals are also called cats because of their similarity in shape, for example the civet cat, the guenon, etc. The word "cat" is a general expression that leaves the gender undecided. If this is to be defined more precisely, the male is called Kater [Tomcat], probably also Heinz [2]) or Hinz, in other regions, e.g. in Livonia, he is Kunz, in Lower Saxony he is Bolze, and in English Karl cat (which means the cat's husband).[3])

There are other things that can be understood by the word "cat". Moerike sings beautifully and touchingly:

"Remember, you tearful singers,

In times of despair, one does not call upon gods, "

and Heinrich Heine also gave deep insights into the essence of this world suffering, his description:

"The grey flock of clouds

rose from a sea of joy;

today I must suffer for

being happy yesterday.

Ah, the nectar has turned into wormwood!

Ah, how painfully depression [Katzenjammer]

Has weighed down my heart

And my stomach is as sick as a dog [Hunde-Elend]"

remains imperishable, at least as long as there are still hangovers [Kater].

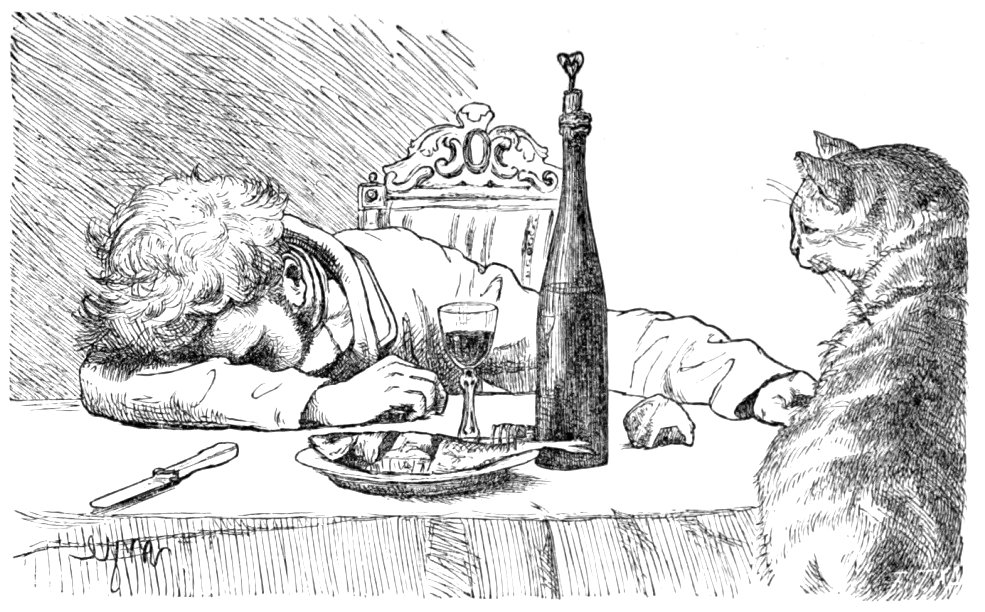

Hangovers [Katzenjammer, Kater] are those incomprehensible feelings of woe and world-weariness that weigh heavily on us after a night of drinking, when we wake up late the next morning with a dull headache as if from a deep stupor. There is a terrible rumbling in the head as though someone is hammering in there, it feels as if icicles and fiery saws are alternately pushing from the inner surface of the skull into the brain. One lies as though on a bed of thorns, rolling about; first your chin hangs on your knees, then you support your leaden head with your hands; now you lie flat on your stomach, now on your back, letting your arms stick out from your body like windmill sails, while your legs hang from the bed in strange resignation.

Lost choruses and unclear jokes swarm like flies through your weary head, until finally you enter a that in many respects resembles apparent death. Then long-forgotten sins pass before your soul, and in addition to this misery you are particularly plagued by a certain, inexplicable capriciousness of the stomach, which you are powerless to satisfy. It is a pitiful state! The mental and physical devastation is unspeakably hopeless! Deep remorse, burning shame and a contrition that threatens to destroy you because of a not entirely clear night that had been so beautiful, darkens your soul and makes the beautiful earth, sunshine, spring joy, wine, women and song seem like mere trifles. Wisdom and understanding, wit, the greatest philosophers and poets, the most ingenious artists and the boldest acrobats are all null and void in your eyes; but the most terrible thing - and this contempt extends to myself - you are convinced that you are nothing but a miserable human being. Can there be anything more devastating than this awareness of your immeasurable misery and that the earth itself is a vale of tears, not extinguished by pain!

With difficulty you rise from the bed, stagger along dreamily, and sad, deeply clouded eyes gaze into the unknown. You put on your waistcoat first, grab your empty purse instead of the soap, run the shoe brush through your hair, try to comb your hat with the comb and use the newly bought scarf as a garter. Finally you're dressed; breakfast is not something to look at, the newspaper is read mechanically, the essence of the leading article is incomprehensible and you cannot tear yourself away from the adverts. Your attention is particularly drawn to news of deaths and advertisements where you can be paid for civil service. But all these temptations cannot whitewash your future; life is boring, expensive and hopeless. Oh, nature, holy nature! is it possible that a little too much of that noble liquid enjoyed on a high flood of joy can make you forget all your caring love, that you can become a rebel against yourself after being convinced that the earth with its joys is the best there is, and you must be happy to live on it.

This affliction, my lovely friend, has been with mankind for thousands of years and, as they say, has become chronic among Germans. As far as the history of this ailment goes, it dates back to the time when Noah came out of the Ark, planted a vine and thus caused scandal in the Lot family. The hangover has become native to all peoples of the earth and it is, therefore, understandable that since the earliest times medicine has had to try to master this inevitable affliction. Pickled herring (harengus acetecum) has been used successfully as a magic pill against this ailment, which doctors classify as "acute alcohol poisoning". This remedy sets the head straight, takes away the stomach's eccentric moods and, preferably in the company of a fine drink, brings about a radical elimination of the evil, based on the rule that he who inflicts a wound must also heal it. Herring is the faithful companion of the hangover and should not be underestimated in view of its historical significance in the animal kingdom. (4) [Translator's note: this also plays on the cat's love of fish.]

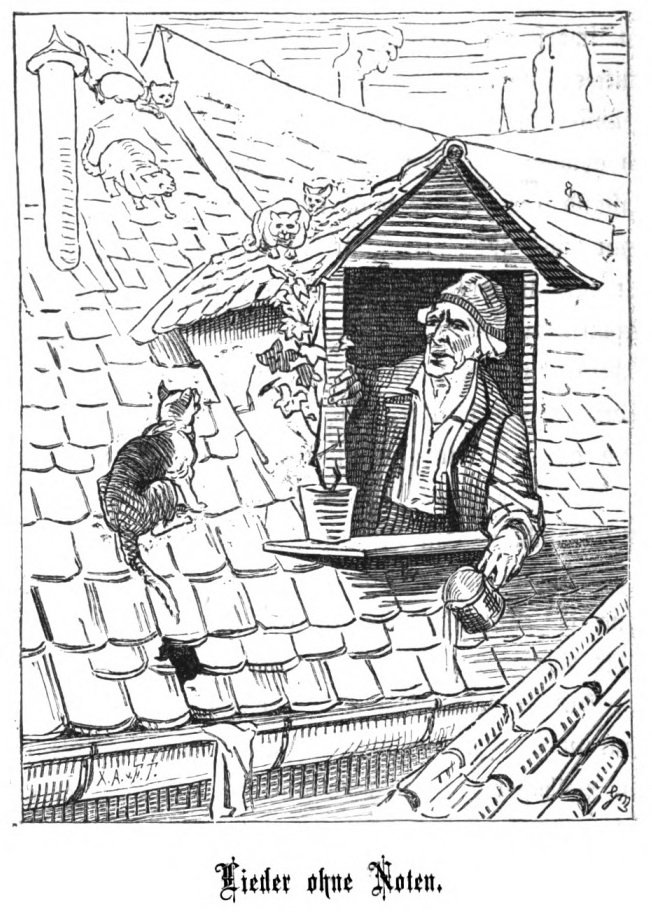

I would also like to mention the word "cat music" (5); it has a history of its own and is connected with marriage and therefore with the fairer sex - and with this I have come to the end of my letter which, along with its subsequent companion letters, I hope will find an attentive reader in you, dear lady.

SECOND LETTER.

Animals and people soundly slept,

Even the lively house rooster was silent,

As a flock of truant guests

Arose from the nearest roofs.

Lichtwer.

My life is love and air and loud singing.

Mahlmann's student song.

As you know, dear friend, there are often inexplicable likes and dislikes, which, because one is at a loss for a more correct definition, are called sympathies and antipathies. What matters here is the extent to which the other person's temperament, ideas and wishes coincide with our own, or, conversely, the extent to which we are repelled by them. In the former case, we feel attracted to one another, often only because of a certain peculiarity of the look or an inexpressible movement of the lips; and in the latter case, sometimes the most external thing has a repulsive effect on us, such as a slightly distorted nose or a too conventional hairstyle.

Antipathies are also often acquired, and are the result of the uncontrolled imagination of mothers, the philosophy of spinsters, and old wives' tales, which have laid the foundation for these idiosyncrasies in children. The most vivid and indelible impressions on the mind of children arise from fear; this is the source of antipathies, which easily extend to objects that least deserve it. Thus, from the cradle, we have been told that cats are false, are sorcerers and witches, and even that they suffocate children. A fear of cats is no more than one of those irrational combinations of ideas which dishonour our understanding. Even the famous Buffon, in his Natural History, was inexplicably unable to break free from the traditional, false assessment of the cat.

"The cat," he says "is a treacherous animal, and is only tolerated in the house to drive away animals that are even more of a nuisance to us. Although cats are polite and mischievous when young, their innate cunning and false character are already evident, which develops more and more with each passing day and cannot be eliminated by training. They are naturally inclined to stealing, and the best training can only turn them into servile, flattering, and malicious robbers; for, like all slaves, they know how to conceal their intentions and wait for the moment to pounce on their prey, evade punishment, and keep away until the danger has passed. They easily adapt to human habits without adopting them; they only appear to be attached, as is evident from the crawling manner in which they move and the ambiguity of their glances. The cat does not look its best friend in the face, even if it shows its attachment to him by certain gestures; it seems to tolerate his caresses, which are more annoying than pleasant, only out of fear or deceit. Very different from the faithful dog, whose feelings are all directed towards its master, the cat seems to feel only for itself, to think only of itself, to love man only conditionally, and to remain in his company in order to abuse it in a selfish way. These characteristics are, however, more closely related to those of humans than to those of the dog, which in its complete sincerity is decidedly the opposite."."

Buffon's views have been sufficiently refuted by modern naturalists. I refer to Scheitlein, Lenz, Brehm, Wood, etc. These erroneous views can only be the result of false impressions from youth, and there are ridiculous antipathies. Bartholin tells the following of a Danish nobleman who was so strong that he could bend iron like sheet metal and yet was extremely afraid of cats: "A good friend of his who was a guest wanted to test him during his meal and had a covered dish with a cat in it served alongside others. Although the nobleman did not see the cat, he was nevertheless very frightened, as evidenced by the sweat that poured from him all over. When the dish was uncovered and the cat had stuck out its head, the nobleman became so indignant that he gave his host such a hard slap in the face that he fell dead to the ground."

Henry III, that weak king of France, could not stay in any place where a cat was present, and Germanicus could not bear the cry or the sight of a rooster. (6)

Many people fear and have an aversion to snakes, crickets, earwigs, even harmless mice, and yet I know women who had mice as their favourites, just as snakes are kept in India for a similar purpose. The prisoner Pelison in the Bastille was fortunate to have a spider in his dungeon, which came to him when he called. Beethoven also had a spider as his most attentive listener for a long time; whenever he played, it let itself down from the ceiling right above his instrument and stayed until the last notes had died away. When one day the maid entered the room and saw the spider, she knocked the little creature to the floor and trampled it before Beethoven could stop her. Beethoven was beside himself with this loss and was inconsolable for a long time.

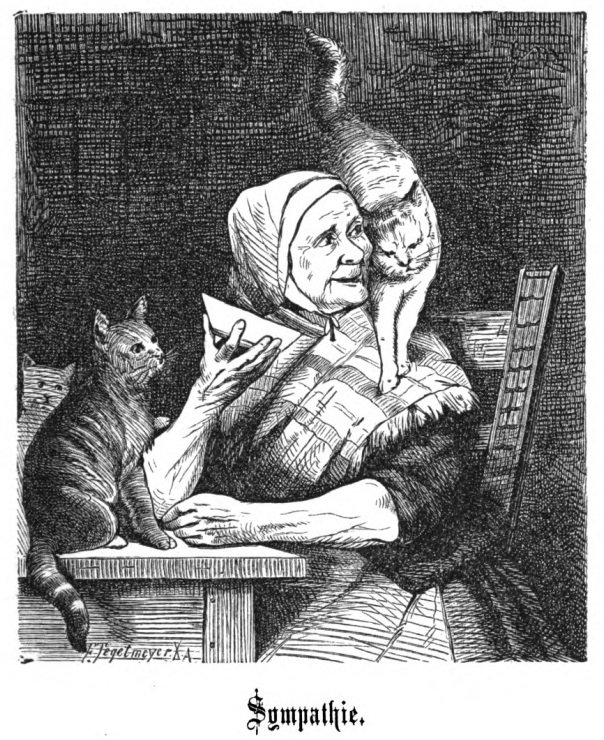

Sympathy is far nobler and more spiritual in nature. Joy and pity are its children, and when we yawn, laugh, cry and drink with one another, the strength or weakness of sympathy depends on greater or lesser imagination and is therefore found among young people and the fairer sex. When this remark is made, many will think of old maids, and not without reason; for they can hardly be imagined without cats, and this is fortunate for both.

Old maids are sufferers, to varying degrees, victims of modern society; poverty alone has destroyed all hope of a husband, of having children, of family happiness; they are alone with the heavy burden of existence, alone in this cold, wide world - so is it surprising that they take refuge in their solitude and transfer all their love and spurned tenderness onto a cat, the only friend in a dreary life who at least knows how to return that love with loyal devotion, sweet purring and heartfelt meowing. Poor old maid, you too have known the rosy, blissful days of youth, have dreamed of happiness, have seen one hope after another die, and now old age has arrived with its icy certainty of the end, the end of a lost, useless life.

Surely it is harsh, unfair, and disgusting to make her the target of ridicule for her undeserved misery, and to mock her love of cats! Did not the mutual love of the maiden and the cat arise from the similarity of their misfortune, from the hard-heartedness of people, from loneliness! But even the abandoned old maid has virtues which, as Huxley proves, have a national significance in England.

"We Englishmen," he says, "hold old maids in high esteem, because England owes its strong race of people to them. The Englishman draws his strength from good meat, from excellent beef. This thrives mainly in red clover - but red clover needs the visit of bumblebees to produce its seeds. Unfortunately, the bumblebees are being killed by field mice. But who kills field mice? The cat. And who best keeps the cat so that it breeds by the thousand? Old maids. And in this way England owes its strong race of people to old maids!"

Poets and artists also hold cats in high esteem. A particularly sensitive nervous system enables them to recognize its great qualities - a recognition that is impossible for those with coarse-minded natures. Cats also have great friends in politics; the love of certain political figures for cats is explained by their contempt for people, for statesmen know that even the purest can often be won over by money, grandeur and honours. In this respect, people in politics hold no illusions; if they had any, they would not be great politicians. Therefore, they like independence in animals, especially the type of independence found in cats. I will just mention Mohammed, the Sultan of El-Daher-Beybars (1260), Stein, Richelieu, Cardinal Wolsey, Chesterfield, Washington, Chateaubriand, de Colbert, Peter the Great, etc.

Wolsey always had his cat sitting next to him on an armchair during his audiences and Richelieu was always surrounded by young cats in his cabinet. Chateaubriand was an enthusiastic admirer of cats; they were his most devoted friends, who remained loyal to him in misfortune, in happiness, in exile and at the embassy. As an ambassador in Rome, he received a cat as a gift from Pope Leo XII as a sign of special favour, which still possessed all his love and affection in his twilight years, when all other feelings had gradually died away,.

The cat was most revered in the Orient. From recent research we know the prehistoric times of many peoples, especially Asian peoples, including their religious relationship. The Indian idolized all of nature, but did not idolize man, the sinner; he seems to have placed him below all natural things; hence his worship of animals.

Hebrews say that man is related to God, while Indians claim that animals are related to God. While Mosaic worship commanded that rivers of animal blood should be shed, Indian priests strangled only one ram a year, and did so only with a plea to the gods for forgiveness. While Israelites considered animals to lack souls, Indians taught that the human soul travelled through animals in order to be cleansed of sins in these sinless, holier beings. The sun and moon - and their earthly expression and image, the bull and the cow, symbols of nutrition, natural power, male and female, heaven and earth - were the most important, and were as sacred as the transmigration of souls, and celebrated in great festivals. Other animals were also worshipped, such as the elephant as a symbol of wisdom and strength, the swan as Brahma's steed; the raven represented the departed, the shadow souls, the snake represented life and the cat, in the form of a white cat, represented the moon that chases away the grey mice, the shadows of the night.

The Egyptians are an ancient people; Egypt, like India and Palestine, is a land where human knowledge originated in times of antiquity and is closely related to India in terms of ideas, but presents a stark contrast to Palestine. Everything about the Egyptians is striking, most inexplicable is their worship of animals. No people saw so much in animals as the Egyptians; they had entire divine animal species for the whole country, and divine animal species for individual provinces. Some people worshiped them all, others worshiped only one individual from them all.

According to Herodotus, the ibis and the vulture were sacred everywhere and the other animals were only sacred in certain regions; according to Diodorus, it was the ibis and the cat. The main animal sacred to the Egyptians, their highest animal deity, was the Apis bull; everyone worshipped him with the deepest reverence. He lived in a temple palace, rested on expensive carpets, ate his food from golden bowls, and the leading men of the state considered it the greatest glory to serve him. But the cat was also sacred and was particularly revered. At Bubastis the Egyptians had a goddess, the moon goddess, named Pasht (7); the Greeks called her Bubastis and compared her to Artemis, the goddess of childbirth and the protector of women. Great festivals were celebrated for Pasht, and one of these was one of the six great general festivals of the Egyptians.

According to Herodotus, "When they go to Bubastis, a large number of men and women travel in each boat; the women have rattles and clatter along, and the men play the flute; other men and women sing and clap their hands. But when they come to another place, they go out on the land, do as described, and tease the women by raising their skirts. But in Bubastis they celebrate the festival with great sacrifices and more grape wine is consumed then than in the whole of the rest of the year, and seven hundred thousand men and women, not including the children, come together according to the natives." From this description it is clear that the festival of Pasht was a very joyful one and that the blessing of this goddess must have been general, great, and especially joyful for women. The custom of the women, as described above, in its crude naturalness, points to reproduction and birth and justifies the comparison with Artemis. (8)

The goddess Pasht has the head of a cat, the cat is a sacred animal, just as the animal of such an important goddess must be. It is impossible to know for certain why the cat was considered sacred, but we can assume, with a high degree of probability, that it was a symbol of light and radiance and therefore symbolised a goddess with light and radiance. The goddess of birth, who ripened the seed and brought those that were mature into the light is in this respect connected with light; the Romans also called the goddess of birth "Lucina", i.e. goddess of light. If we now consider a birth goddess through festive customs and through comparison with Artemis, we may also assume that in Egypt the cat symbolised of the birth goddess. In Thebes it was one of the temple deities and the Artemis Grotto, as the Greeks called it, takes its name from it. Champollion says in the sixth of his Egyptian letters that the so-called Artemis Grotto was hewn into the rock opposite Beni-Hassan-el-aamar and contained images of Bubastis and around it were the burials of cats. In front of the sanctuary there is a row of cat mummies wrapped in mats, and further between the valley and the Nile in a desolate area there are two burials of cat mummies in packages, covered with sand two feet high.

In bronze statues, Pasht is often depicted with the sistrum (9) in her right hand and in her left hand the lion's head with the sun disk and the uraeus, the symbol of royal dignity, and sometimes also with a basket or an urn on her arm. The sistrum evidently has no symbolic meaning other than its sound which is intended to scare away hostile creatures. In Egyptian mythology the hostile creatures that must be chased away with the sistrum - which mostly belongs to the service of Isis - can be none other than those that could hinder nature's prosperity and blessing. So in Bubastis's hand this tool must also relate to chasing away those creatures that hinder the blessing and Bubastis must, therefore, be a goddess who promotes the blessing. If we assume that Isis's sistrum was decorated with a cat's head, it follows that the cat was considered a symbol of nature's blessing and reproduction.

A cat-headed goddess Rta is found in the oldest monuments of Upper and Lower Egypt, especially near the pyramids, and had the same significance as the Bubastis.

The Egyptians paid full divine honour to the animals chosen as symbols of their deities. Where such a symbol was worshipped as a god, the entire species was not allowed to be killed. One of these animals was the cat; it was worshipped through a mysterious cult that was gradually transmitted to the Greeks and Romans and left traces in many monuments, as eloquent witnesses to the great importance of the cat species. And, dear friend, does it not seem to be a particularly wise act of Providence that these antiquities have come to us, to remind us that little Mrs. Pusscat does not deserves to be treated badly! Is it not greatly importance, indeed indispensable, to present copies of those ancient works of art to the cat's enemies? - And so I begin with a figure which, as you will notice, is richly decorated with symbols and is designed to arouse envy. In front of the cat goddess one sees a lotus flower and a sistrum, the handle of which is in a cup - and now I would like to ask her opponents how they explain the coming together of the sistrum and the cup, which are usually depicted between the cat's feet. I believe, my dear, that they will honestly admit - and there are certain truths that can overcome the prejudice - that the sistrum is the symbol of music, the cup evokes the idea of festivities, and if they pursue this path further, they soon reach the realization that cats took part in Egyptian festivities and, with the magic of their beautiful voices, were the cream of the entertainment.

The Egyptians were anxious to enjoy the life's pleasures as much as possible, so skeletons were carried around during their banquets as silent reminders of life's transitoriness. "Drink," they said, drink and be happy, tomorrow you may be dead." This custom certainly has its advantages, but I do not know whether the first impression of this reminder could have been a pleasant one; for joy can only be awakened by joy, and how could this be better achieved than by the sistrum and the cats! Surely only they were able to bring joy and merriment to the festivals by their appearance.

Another image shows the cat goddess with a cat's head on a man's body and a sistrum in his hand. But with what a sense of security he carries it; does that not undeniably mean: "Behold, I have mastered it!"

And why shouldn't there be a real relationship between musical instruments and cats, seeing as it has been recognised for centuries that dolphins can understand the sounds of the lyre, that deer delight in the sound of the flute, and the mares of Libya loved the songs of the shepherds so much that a special song was made up for them. (10)

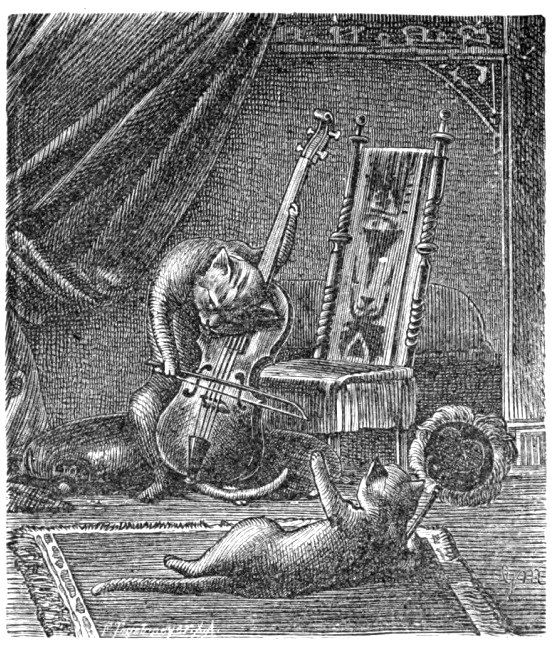

Music is without doubt the oldest and most powerful of the arts, and its power lies more in feeling than in understanding. The dried intestines of a cat, stretched over a piece of wood and raked by hair, can summon the spirits of harmony from the realm of the air, and make the harmony of Plato's heavenly spheres and the harmony of Christian angelic choirs audible even here on earth. Musical notes are truly air spirits that move from one soul into another, hence they are a universal language not only for humans, but also between humans and animals and are perhaps the next transition to mutual understanding. All peoples at the first level of culture already have music; primitive man follows his feelings when he hears musical tones or makes them himself though he has no idea of our mathematical tonal systems; what "moves his heart," dear friend, is sung out, just as the lark sings, high up in the blue ether, in the radiance of the sun, yes even like the tomcat on a moonlit roof slope.

According to the ancients, gods invented music; Maneros (11) invented music in Egypt, Apollo created the lyre, "from Jubal came the pipers and fiddlers" and among the ancient Germanic peoples, Odin was the god of music. The first real musicians were the priests of Egypt and India. The ancients had many wonders to tell about music as the ruler of all passions. Orpheus (12) moved trees, rocks and even hell with his art; Amphion moved the building stones in the construction of Thebes (13); Voinamoinen's harp in the Kalevala made the wolf forget its cruelty, the bear forget its wildness and the fish forget its coldness; the trumpeters of Jericho blew down the walls, and in Germanic myths the Albleich is a sweet, tempting tune and that of the Swedish Stromkarl or Fossegrim is tempting and enchanting. Of his eleven variations, only ten may be played: at the eleventh, which belongs to the Night Spirit and his army, tables and benches, jugs and cups, old men and grandmothers, even children in the crib would begin to dance. Anyone who wants to learn his art sacrifices a black lamb or a white kid to him; if it is very fat, the Fossegrim takes hold of the apprentice's right hand and moves it back and forth until blood spurts from the fingertips: then he is perfect in his art and can play so that the trees dance and the waterfalls stand still; indeed, the player cannot stop unless someone cuts the strings from behind or he has learned to play the piece backwards.

The basis of all music is song, and therefore vocal music is the oldest, in which birds, and animals in general, were our teachers; in music they are freer, they make their own rules. But cats are also very well organized for music; their voices are capable of the richest modulation and are able to express their feelings in the most varied expressions. What inner well-being the cat shows when it purrs or makes the sound of a spinning wheel, or what a wonderful gift it has to express sorrow, joy, delight, anger, fear and despair in its meow. In a chivalrous "Murr Murr" it can express belligerence, a short chuckle can express love and tenderness, its growl and hiss can express anger and pain - in short, it can express all emotions in the most varied modifications. Does it not have the most extensive vocabulary of all animals, and this, the simplest of all languages, is surely more admirable than the language of man, who often speaks a lot, but conveys so little?

I am convinced that these views will be challenged by cat-haters; but what sounds like howling to today's cultured people is probably nothing more than their own lack of knowledge and taste. Our music today is limited by a division of tones that we call whole tones or half tones - and we ourselves are limited enough to assume that this division must encompass everything that can be called music. This is precisely where the injustice of referring to cat songs as roars, howls and meows comes from, precisely because we find their intervals and admirable connections incomprehensible because they transcend the boundaries within which we are trapped. In this respect the Egyptians were more enlightened than we are, they knew the cat and its musical abilities; for they knew that it is a matter of individual feeling as to whether a tone is right or wrong, and that some people, out of habit, call certain combinations of tones either dissonances or chords; they felt that when cats in their music went from one tone to another in the same proportion as we do, or when they split the same tone and struck the intervals which we call pitches: that this would have produced an extraordinary difference between their music and ours. The Egyptians were able to distinguish well between the simple or artistically hidden modulation in a cat choir or in a recitative, the lightness of the runs, the softness of the sound or the sharply penetrating accent of the dramatic climax because they were receptive to pleasures that we have completely lost in our desire to be know-it-alls. As a result, we have no qualms about declaring the cat's songs to be wild noise, even if this difference is due only to our ignorance and a lack of sensitivity in our own organs. To us, the music of the Asian peoples seems ridiculous at the very least, and the Asians find no sense in ours; we each believe we only hear the other yowling instead of singing; every nation has this view to a greater or lesser extent and each is, so to speak, the other's cat. (14)

My opinion about the euphony of cats' voices may seem dubious to some, but it finds strong support in what Plutarch says about crickets. Plutarch calls crickets singers and claims that they were declared as such by Pythagoras, who, out of love for their singing, issued the command to destroy swallows' nests on houses, because swallows tried to kill crickets. Pythagoras was the finest connoisseur of music in antiquity; someone who heard and felt the concert of the stars when the planet Earth, through its movements, produced exactly a third or an octave with the tone formed by the planet Venus, certainly deserves to be believed when he says that crickets are singers. (15) If we must therefore admit to Pythagoras that the song of crickets is melodic, only ugly envy can deny this recognition to cats; at the very least we must admit that the voices of cats are clearer and that we can more easily distinguish the differences in their tonal figures.

How greatly music was refined in animals, not only as natural song but also in theory, is evident from the seventh story of the Panchatantra, in which the donkey appears as a singer, and with unexpected success. Once upon a time there was a donkey named Uddhata (the arrogant one). During the day he carried loads in the house of a fuller, and at night he roamed about wherever he wanted. One day, as he was wandering around the fields at night, he made friends with a jackal. Both of them broke down fences, went into the cucumber fields and feasted on the fruit to their heart's content; in the morning they returned to their places. One day the donkey, arrogant with pride, said to the jackal when he found himself in the middle of a field: "O sister's son! Look! The night is so clear, so I want to start a song. Tell me, in what key should I sing?"

The jackal replied: "My dear! Why all the unnecessary noise? We are involved in roguery. Thieves and lovers must stay hidden! It is also said that if you have a cough, you should not steal; if you oversleep, you shouldn't be a robber; if you're sick, you shouldn't talk too much. Besides, your singing sounds just like the sound of a conch shell and isn't at all pleasant. As soon as they hear it from a distance, the field guards will set out and bring about your imprisonment and death. So just eat these cucumbers that taste like jelly and don't bother singing here."

When the donkey heard this, he said: "Ah! You don't know the magic of music because you live in the forest, that's why you say such things. They also say: If the autumn moonlight breaks through the darkness near your sweetheart, blessed then are the ears into which the divine drink of the song penetrates!"

The jackal said: "My dear! That is true, but you sing harshly. So why all this shouting, which would only disturb our plans?"

The donkey said: "Ugh! Ugh! You ignorant one! You think I don't know what singing is? So listen to its division: seven tones and three octaves and twenty-one intervals and forty-nine time signatures and three quantities and tempos. There are three kinds of rests, six melodies, nine moods, twenty-six colours, and then forty states. This system of singing, comprising one hundred and eighty-five numbers, if well executed and flawless, encompasses all parts of singing. There is nothing in the world that even the gods would prefer than singing; through the magic of the gut strings Ravana sings Siva himself. So, oh sister's son! why do you call me an ignorant one and stop me?"

The jackal said: "My dear, if you do not want anything else, I will stand at the gate of the fence and watch the field guard, and you can sing as much as you like!"

When this was done, the donkey stretched out its neck and began to bellow. When the field guard heard the donkey's bellowing, he gritted his teeth in anger, picked up a club and rushed over. When he saw the donkey, he beat it until it fell to the ground. Then the field guard tied a wooden mortar with holes in it to its neck and went to sleep. But the donkey got up immediately without feeling any of the pain, as is the nature of donkeys, smashed down the fence and fled with the mortar.

In the meantime the jackal watched this from afar and said laughing: "Although I said: 'Oh uncle! Stop singing!' you still continued: now, as a reward for singing, you have this completely new adornment hanging around your neck."

The views on the expressiveness of the cat's voice, and on the language of animals in general, are still very poor and it is astonishing how close communication between humans and animals in this direction has not been able to produce more results.

Every animal has its own language. Animal language is only gesture and tone language, which does not begin with syllables, as with us, but is taught by nature according to the phonics method and is quickly learned. The cock, the farmyard despot, converses with his hens like a sultan in his harem, storks hold long councils and make long speeches, and cats, as has been proven, have a great gift for conversation and have an extensive dictionary. We understand only a few words, and we are naive enough to think that all words must sound German; but we overlook the fact that animals are astonished to hear us speaking in our own gibberish. Man, as the pinnacle of civilization, is able to account for a subordinate intelligence. He is able to dissect his most secret feelings in the alembic of reason and study them to their final reduction. While a child cannot follow the complicated mechanism with which civilization has equipped man, an older person knows from experience how to understand the child's utterances; in the same way the wet nurse understands the child, but the child does not understand the wet nurse; and an animal is comparable to a child in this respect.

What prevents us from discovering the secret of animal language, from understanding the conversations of most animals, is the difficulty of putting ourselves in their place. This difficulty is increased by the prejudices with which we view animals and at the same time by our own overestimation. Learning the language of animals is not as difficult as it seems; for if one observes it most carefully, one soon understands that the animal attaches different meanings to different sounds. The cry, evoked by emotion, by a nervous reflex, is repeated on a similar occasion, becoming the definite expression of a definite feeling. If you lives in close contact with animals and have the necessary powers of observation, you will find that learning animal language cannot be more difficult than learning that of savage peoples, or that of some distant nation of whose language we know neither dictionary nor grammar.

If we accustom our ear to the sound and imprint it in our memory, we will immediately recognize it when it is repeated and distinguish those sounds which have a similarity to it.

The animal has few needs and passions, but those needs are imperious, those passions lively, and the expression of them is significant; but its ideas are few in number, its dictionary small and the language more than simple. In comparison to this, we have a very rich language, a multitude of ways of expressing the differences in our ideas, and therefore we should not be embarrassed to be able to translate animal language into human language. But is it not incomprehensible that animals are able to translate our own rich language into their own impoverished language; for it is well known that they understand us; otherwise how would the cat, the dog, the horse and the birds obey our call and understand our teaching?

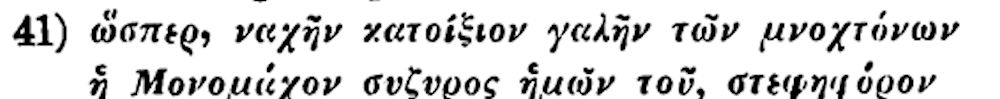

Important people have studied animal language and published noteworthy observations about it. Among others, Scheitlein, Montaigne, Dupont de Nemours; Marco Bettini translated the song of the nightingale, Wezel wrote a book about love and the language of animals. Even outstanding musicians have recognized the cat's musical virtues. Domenico Scarlatti, born in Naples in 1683, was the greatest piano player of his time and composer of many piano pieces, including a cat fugue. His favourite cat, who ran across the keys, gave him the theme in the following tones:

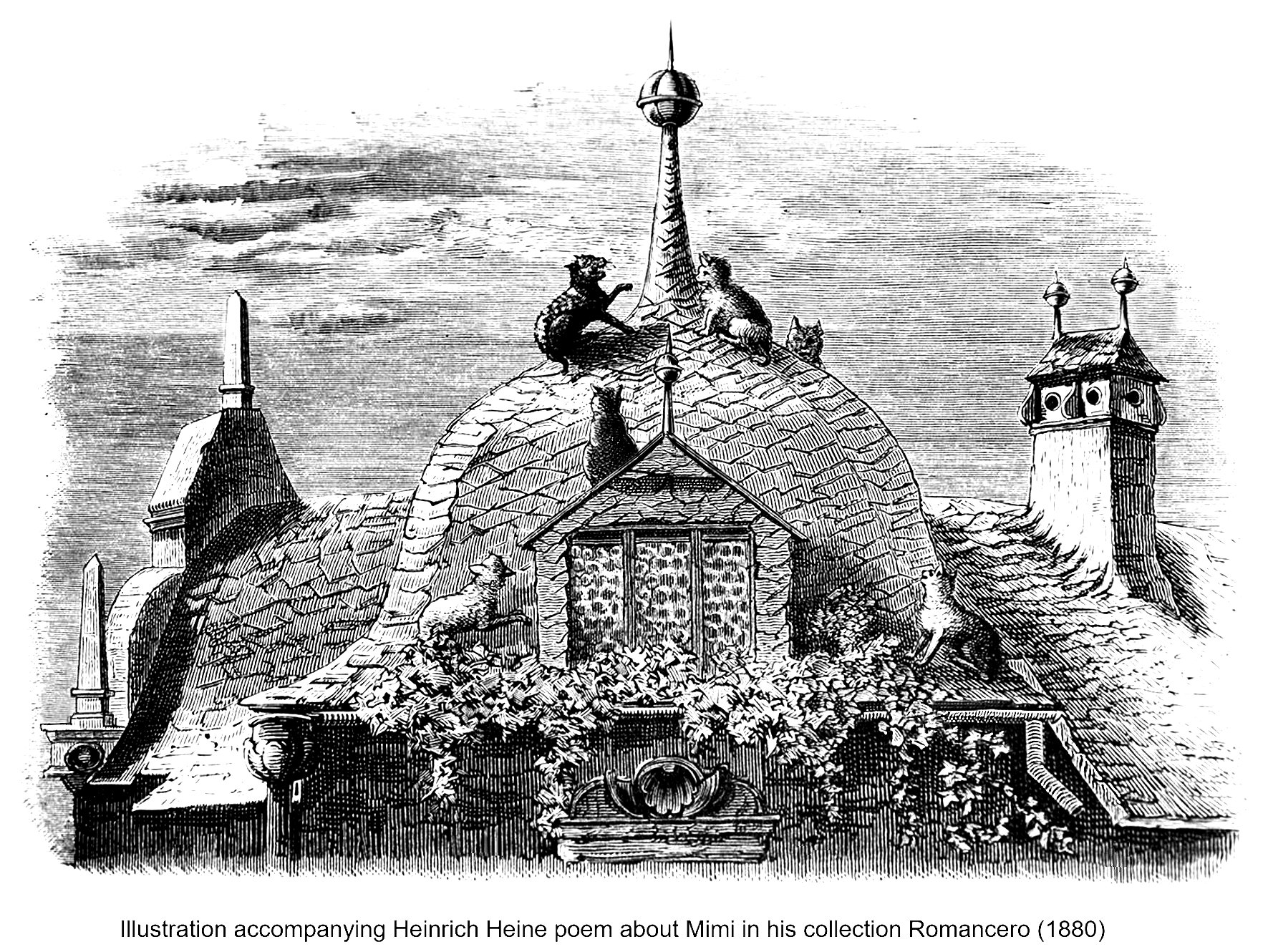

Rossini's famous cat duet is believed to have had the specific purpose of pointing to the increasingly widespread externalization of Italian music, and truly, he could not have chosen better and more authentic interpreters. The composer Adam also loved cats very much, and is said to have always composed while lying in bed with his cat. Only a few of the great minds of our century have understood the music of the cat, and the foremost of them is Heinrich Heine, who poetically described the beauty and expressiveness of the cat's voice in the following truly magnificent poem:

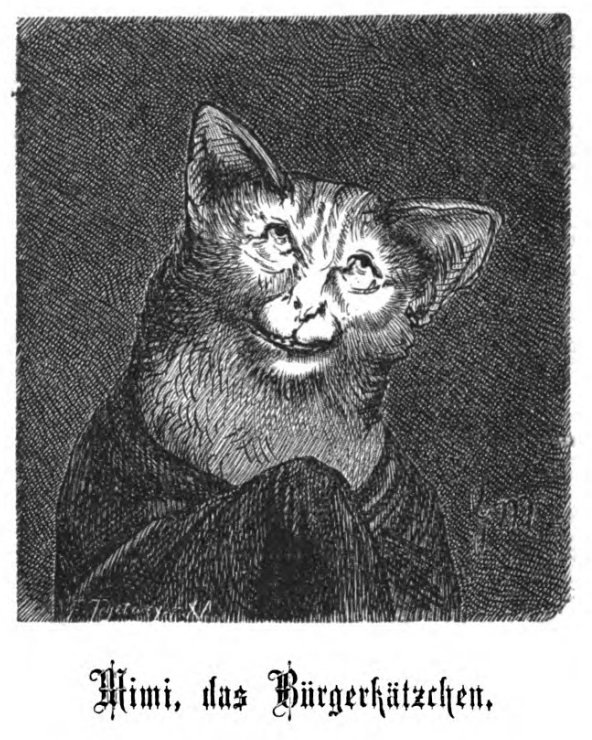

Mimi.

I am no modest bourgeois kitten,

Purring in some pious little room,

I'm a free cat roaming in the open -

Prowling upon the city roofs.

When I am raving on a summer night

When the air is cool upon the roofs

Music stirs and growls within me,

In song I let my passions loose!

Thus speaks Mimi. From her bosom

Pour forth her wild bridal songs,

And her euphony is a summons

To all the wandering bachelor toms.

The tomcat bachelors flock to the singer

Purring, growling, to express their love,

Longing to make their music with sweet Mimi,

Thos ardent suitors glow with lust.

These singers are not virtuosos,

Who desecrate music for reward,

No, these remain faithful apostles

Of holy music, from the heart.

These musicians need no instruments,

They themselves are violas and flutes;

Their bellies are the kettledrums,

Their muzzles play the part of trumpets.

Together they raise their many voices

Performing in a that rooftop concert;

They play their fugues, like those of Bach

Or Guido of Arezzo's works.

They perform great night-time symphonies,

To outdo Beethoven's caprices,

Competing with Berlioz's melodies

Which they growlingly surpass.

They make such wonderful forceful tones!

Their magical sounds are beyond compare!

Their choruses even shake the sky,

And make the shining stars grow pale.

When she hears that magical night-time music,

Those wonderful nocturnal sounds,

Selene, the pallid moon, covers her wan face

And hides behind a veil of clouds.

Only the slanderous songstress nightingale,

Haughty Prima Donna Philomela

Turns up her proud nose, denigrating

Mimi's singing, that cold, unfeeling soul!

But no matter, for Mimi plays her music,

Despite the Signora's disparaging tones,

Until on the horizon dawn approaches,

And fair Aurora's rosy smile glows.

If I claimed above that through careful and loving treatment of animals, man can gain a more detailed knowledge of the mental life, language and of all vital expressions of the animal's nature and can thereby expect extraordinary affection from the animals in return, I am in the pleasant position of being able to support this claim with a drastic example from my own experience. Through the trusting affection of a cat friend, I have managed to come into possession of the photograph of that citizen's kitten, which I do not wish to withhold from you, dear friend, and which, in its correct reproduction, may adorn the end of this letter.

THIRD LETTER.

History is just an agreed fable.

In the Mysteries of Isis, to return to the cats in Egypt, several more images were found which I will discuss in more detail in order to characterize the full significance of the cat.

The cat goddess Pasht, sometimes called Aeluros in Greek, was often depicted with a human-like face, a peculiar appearance that has been interpreted in many ways and explained, among other things, by the resemblance that the cat is said to have to the moon. Plutarch says that she represents the moon because of the colour of her fur, her activity at night and her fertility; for she first gives birth to one offspring, then two, three, four and five, and then seven at once, so that in total she gives birth to twenty-eight, which correspond to the days of the lunar month. The cat's pupil is said to become full and wide during the full moon and to become smaller again and lose its shine during the waning moon.

According to Horapollon, the cat was worshipped in the temple of Heliopolis; it was sacred to the sun because the animal's pupil follows the course of the sun. Horapollon sees secret analogies in the play of the cat's eye and the sun; Plutarch connects them with the moon; modern science, on the other hand, is very cold; it explains these phenomena through optics and leaves the influence of the stars on humans and animals to the mystics.

But this union of human and animal nature in the cat goddess has another, metaphysical cause, which I think it is particularly important to examine. You know, dear friend, that the vanity of humans always drives them to resemble the being they have raised above themselves. When altars were dedicated to the Pasht in Egypt, some of their features were transferred to her, perhaps unconsciously, for this deity has a human body and a cat head, and as a sign of the highest veneration, was adorned with the uraeus and the radiant crown, among other symbols. It is obvious that the women of Egypt felt the advantage of resembling the Pasht, and one may assume that it was they who embellished the goddess with some of her forms and thereby contributed greatly to her prevalence and popularity. And really, who could object to that! It's surely praiseworthy to see the cat goddess represented by a beautiful woman, adorned with the uraeus, a kind of sceptre in her hand, majestic, sublime, every inch a queen! -

Another image (16) in the form of a woman wears a kind of half-veil which partially covers the shoulders, but leaves her graceful neck free. A tunic falls modestly to her feet and in her hand, pressed to her breast, she holds a man's head as a symbol of power over hearts. Is it any wonder, then, that with such a wealth of grace, they saw in her the mother of love, and that the beauties of Memphis strove eagerly to resemble her, that poets in their praise of women could say nothing more flattering than to find the eyes of their beauties as round and shining as those of their ideal, the cat goddess! Perhaps women who hate cats may be displeased by the strength of these facts, but I cannot help wishing them such an enviable fate, to be as loved and praised as the cats in Egypt.

In Egypt (17) every deity had several priests, among whom was a high priest, and from the order of priests the kings were sometimes chosen. These priests led a very austere life, had taken a vow of celibacy and spent most of their time in the temple caring for the cats. The priests who were next in command to the king took part in the government of the country and all higher wisdom - what an honour for the cats - emanated from them.

The ceremonies of their temple service - we assume - corresponded with the spirit and other characteristics of this deity; liveliness, elegant suppleness and graceful movement of the body would have been cultivated and practiced in the temple of Pasht. But isn't it strange that this kind of temple service, this tendency to amuse ourselves, has found a clever imitator, a representative in our German Kasperl puppet show, that what makes the scene comical in our country was, in Egypt, the entire majesty of the goddess, before whom one bowed to the ground! What a strange contradiction of the human mind! The animal that was divinely worshipped in the land of the pyramids is, after a while, mistreated by a stable maid - yet people say that the gods are immortal!-

The respectful treatment that cats received in Egypt (18) shows us how much value was generally placed on them in society; they were perfumed daily, fed with the most exquisite delicacies and laid in well-stuffed beds. Cats of delicate constitution were cared for with loving attention; in cases of illness all the secret remedies of medicine were used and for the time of love their mate was chosen with careful attention. Herodotus tells us: "When the females have given birth, they no longer run to the male; the males then steal the young from the females and kill them, whereupon the females return to the males, since this animal likes to have young."

"But when a fire breaks out (19), a strange thing happens to cats: the Egyptians stand aside and watch over the cats, not worrying about putting out the fire, but the cats slip through the people and throw themselves into the fire." At this disaster there was a general solemn mourning, and it was so sincere that women even forgot their beauty, smeared their faces, wandered through the streets weeping and beat their breasts; at their side walked their closest relatives, half naked and lost in that kind of mental confusion which is always the mark of great grief. (20)

Diodorus reports that anyone who kills a sacred animal either deliberately or unintentionally is often put to death in the most gruesome way by the arriving crowd without a verdict. Therefore, those who see such a dead animal stay far away from it out of fear, and cry out loudly with lamentations and assurances that they have found it dead (21). The sacred fear of these animals was so deeply rooted (22) that King Ptolemy was unable to save a Roman who had unintentionally caused the death of a cat. The people, outraged by the disgraceful act, gathered in a mob and marched to the perpetrator's house and neither the nobles sent by the king nor the fear of Rome prevented the embittered crowd from avenging the supposed sacrilege by murdering the perpetrator. This rebellion was the beginning of the downfall of the Roman power - which was bound to fall as soon as it had a cat as a rival.

If a cat died of natural causes (23), the inhabitants of the house wore mourning and shaved their eyebrows (24). The deceased was laid in one of the holy houses, embalmed with the most precious spices and buried with solemn pomp at Bubastis.

In Memphis (25) there may have been cats whose funeral was more splendid and more expensive than that of Alceste or Hephaestus. Admetus, to show his great grief at the loss of his dear wife, ordered the manes and tails of the horses that drew the hearse to be cut off, and Alexander went even further and had the manes and tails of the mules removed throughout his kingdom, as well as the horses' manes and tails, and even the battlements of the cities had to be torn down; (26) - but what are such sacrifices (27) compared to the tears of the most beautiful women who wandered through the streets lamenting and demanded that ate returned their cat whose days had been prematurely cut short by the pitiless Fates; what can be weighed against so many sacrificed eyebrows, the adornments of the most beautiful foreheads in Egypt!

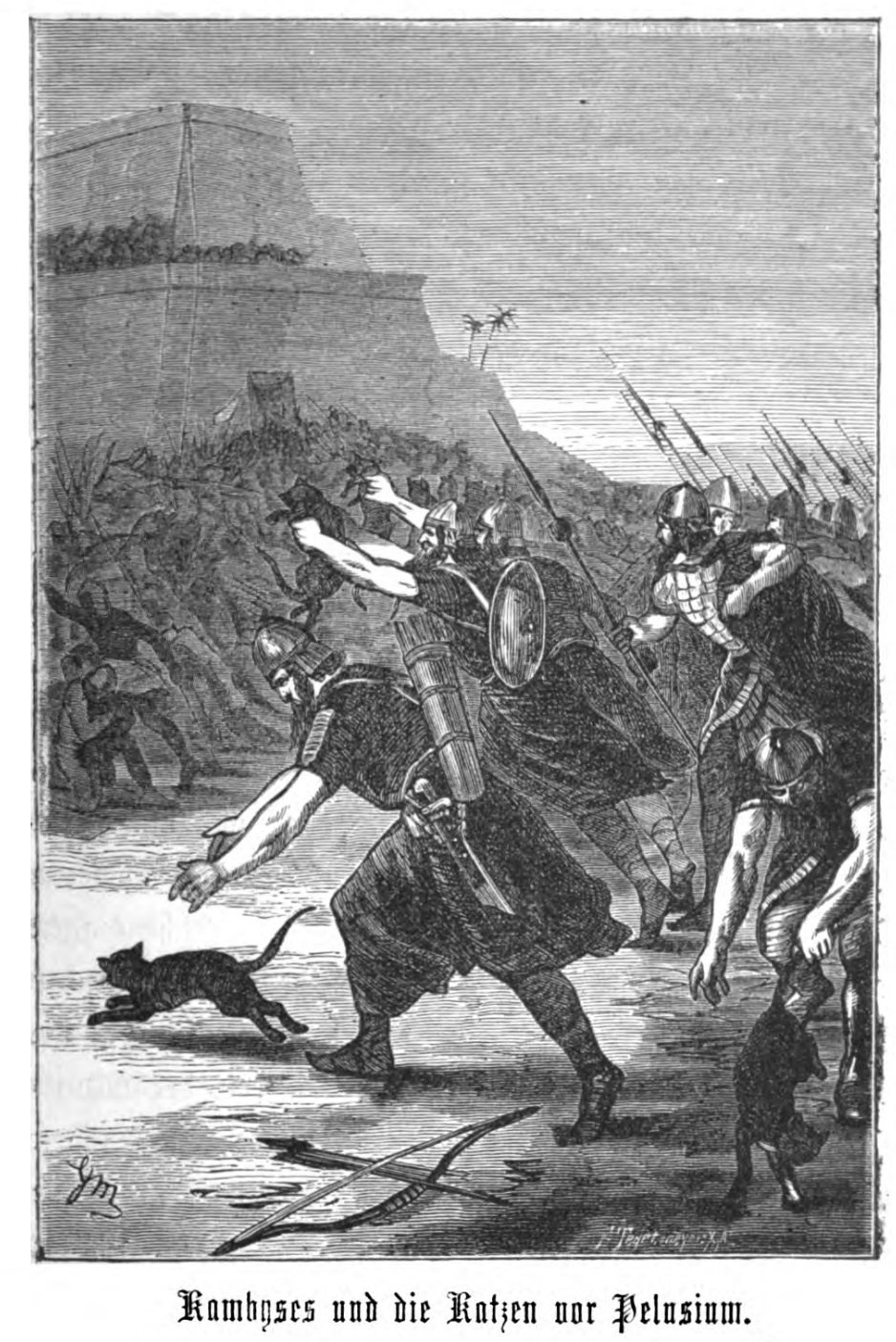

This veneration of animals influenced all the Egyptians' actions. According to Diodorus "In the cities, vows are made to these animals and parents shave their children's whole head or a part of it and the weight of the hair in silver is given to the animal's keeper receives for the animal's care. The sacred animals are cared for in sacred rooms, receive warm baths, the finest food and are anointed with the best ointments." (28) Caring for these animals was considered a great honour; people wore the image of the sworn cat on their chests and the citizens' respect sometimes went so far that they bowed to the ground in greeting these people. (29) This piety towards the cat was never shown in a clearer and more beautiful light than in the war against Cambyses. (p. p. 65.)

This ambitious and violent king was unable to expand in Egypt until he conquered Pelusium (30), which was strongly fortified and considered impregnable. Many attacks had already been repulsed when Cambyses came up with an ingenious stratagem. He knew that the city garrison consisted only of Egyptians, and he knew of their idolatrous worship of cats, therefore, during the next attack, he had cats driven in front of the army and each of his soldiers carried a cat on his arm instead of a shield, (31) - and the Egyptians surrendered without a stroke of the sword.

The Arabs (32) worshipped a golden cat; they held cats in high esteem and attributed to them a different origin from the creation of other animals. In the first book of the censored Alkoran it says as follows: "Once Abiades asked Muhammad why Jews and Turks were forbidden to eat pork and was told that when one day the disciples of Christ asked him to tell them what had happened with the ark, how the people lived and dressed in it, Christ took a handful of earth, kneaded it into a certain shape and threw it on the ground, saying: "Arise in the name of my Father!" and immediately a man as grey as ice stood up. Christ asked him who he was and received the answer: "He was Japheth, the son of Noah." He then asked: "Were you always so grey when you died?" He said: "No, in the hour when I thought that I would have to rise again and perhaps appear before the Last Judgement, I became grey from fear." Then Christ ordered him to tell his disciples the story of his father in the ark. Japheth related that the accumulation of garbage had caused the ark to tilt to one side, which forced his father to move the elephant to the other side as a counterweight. But the elephant, as soon as it arrived, increased the garbage without any consideration, which resulted in a large number of mice, which immediately began to gnaw on the walls of the ark. Noah was in great distress and consulted with God, who gave him the order to strike a blow to the Lion's forehead. When this was done, the lion snorted and a cat fall out of its nose, and throttled the mice in an instant."

Another oriental legend concerning this subject, which has escaped the researches of various travellers, bears more the stamp of probability and therefore appears to me more worthy of note.

During the first few days when the animals were in the ark, frightened by its movements, they remained fearfully in their cages. The monkey was the first to think of breaking the boredom of their new abode by visiting its neighbours. Soon his heart was lost to a young lioness, and from that time on they flirted with each other, with sweet nothings, a attractive example which met with universal approval, and spread a spirit of coquetry throughout the ark, which lasted not only during the flood, but lives on in some of the animals to the present day. As a result, many infidelities occurred, which resulted in entirely new species of animals. From the love of the monkey and the lioness came twins, a male and a female cat, who were distinguished from all other animals which had been created from such unions in the gallant time of the Flood, in that they had the ability to reproduce their race. (33)

The Arabs have other reasons for respecting cats and protecting their lives. It is widely believed that if a woman gives birth to twins, the second-born child may turn into a cat.

Lady Duff Gordon tells, among other things, in Macmillan's Magazine the following about an experience during her stay in the Orient: "Do you remember the German fairy tale about the boy who sets out to learn to be scared? Well, I, who have never been scared before, had a foretaste of it a few days ago. I was having tea in the company of some gentlemen in the morning when I noticed a cat which made a move to approach us. I lured it and offered it milk, but the cat looked at us and ran away. "You would do well, lady, to be kind to the cat," said one of those present, a local merchant, a very sensible man, "you would do well to be kind to this cat, for I believe she gets little enough at home. Her father is a poor man and cannot cook for his children every day." And addressing the company in an explanatory tone: "It is Yussuf, Ali Nassierie's son, it must be Yussuf, for his twin brother Ismaien has gone to Negadeh with his uncle." I confess that this speech gave me the creeps; not, however, because of the strangeness that I had heard, for I have often heard similar ideas expressed by men and women in Europe; but this absurdity in a caftan with the full seriousness of a Muslim made a very special impression on me. What, I said, the boy who brings me meat every day is a cat?! "Certainly, and he knows well where to get a good morsel, as you see. All twins, if they go to bed hungry, walk about at night as cats, while their bodies lie as though dead at home. But no one is allowed to touch this one, otherwise it will die. When the twins get older, around ten or twelve years old, they lose this peculiarity. Our house boy also goes about at night as a cat. Hey, Achmet! Come here! Don't you sometimes go out as a cat too? "No," replied Achmet calmly, "I am not a twin, but my sister's sons do." I then asked whether people were not afraid of such cats. "Oh no," said the merchant, "why be afraid? They will just eat a little of the cooked food. You just must not hit them, because the next day they will say to their parents: "so-and-so hit me," and then show their lumps. But you can also prevent these transformations into cats if you give the twins a certain dish of onions and milk as their first meal immediately after birth."

The Persians, an enlightened people as you know, revered cats to a great extent; this is already evident from the history of one of their most famous kings. He called himself Hormus. He was startled out of the comfortable calm of peace by the news that Prince Shabe-Shah, his relative, had invaded his kingdom with three hundred thousand men. The king was dismayed, his ministers were at a loss; suddenly a venerable old man appeared in the doorway and said to the king: "King, you can destroy the rebel army in a day; the hero who deserves this glory is in your kingdom. You will recognize him among your generals by a distinction as rare as it is worthy of glory; you will recognize him by - - - but, my lord and king, in order not to appear suspicious by the strangeness of my statement, I will remind you of the services I once rendered to King Nuchirron, your great father. It was when your father entrusted me with the task of obtaining a princess for him from the Khan of the Turks in marriage. I was taken to the palace of the princesses, who all seemed to me exceedingly beautiful, and I should have been very embarrassed if beauty alone had been to guide my choice; but I wanted to balance the scales with good qualities of heart and mind. The Khan allowed me to stay at court for a while, and I took advantage of this opportunity to learn the peculiarities of the princesses' characters, and I must confess that they all showed a great desire to become the wife of the Persian King, for each one tried to surpass the other in amiability and beauty. But one of the princesses-she is the one who became queen and your mother-one, I say, did not change her conduct; she always showed the same love for the performance of her duties, was a rare character of great gentleness and true femininity; she possessed a certain grace of spirit which irresistibly won her the love of all who came near her. These signs of true virtue determined my choice; in the name of my king I wooed this lovely princess, and the emperor, her father, following the custom of his country, had his most skilful astrologers cast her horoscope. The observations of all these astrologers had the same result: one day this princess would give birth to a son who would surpass all his ancestors in fame; who, attacked by a prince of Turkestan, would be victorious if he were so fortunate as to find among his subjects a man with the face of a wild cat." The old man, who possessed the knowledge of the wise, had hardly finished his speech when he disappeared as quick as lightning.

The king sent many messengers into the country to find the man who would save his crown. The old man had not given the hero's name or place of residence, but the happy resemblance to the cat soon led him to recognize him as Baharam, called Kunin; he was from the line of the princes of Rei and ruled the province of Adherkigan at that time. Hormus gave him command of his army, but Baharam chose only twelve thousand men to defeat three hundred thousand rebels. This small troop, encouraged by the miraculous sign on the face of their general, defeated the enemy army; Baharam personally killed Prince Schabe-Shah and took his son prisoner. - Thus the victorious end of one of the most famous and remarkable wars can basically be considered the work of a cat. - (34)

The importance of the cat in ancient life - and not only in the Orient - can be seen from the fact that dreams in which cats appeared were given special significance. Artemidorus, the Greek philosopher, writes in his Oneiro kritika (Dream Interpretations) III: If one dreams of cats, it means adultery; for just as the cat pursues birds, secretly and quietly, so does one pursue women; birds are compared to women because of their beauty, loveliness and friendliness, as well as their chatter and charming song.

In other customs and traditions, too, there is the idea of a connection between cats and adultery. The Egyptologist Prisse d'Havennes reports: Women sentenced to death for adultery are sewn into a sack with a cat and thrown into the Nile. A similar law can be read in the Electorate of Saxony Constitution. The murderer of parents, children or husbands was sewn into a sack with a cat and drowned. (35)

The dream book of Apomasiris - to speak even more about cat dreams - tells us: A cat in all dreams means a thief, whether he is a man or a woman, etc. - A dream in which a cat appeared was even the cause of a piece of world history.

A cat once appeared to Etzel, king of the Huns, in his youth. He was sitting dreamily in his uncle Rugila's tent; he was melancholy and was wondering whether he should become a Christian and serve God and the sciences - then the cat came. Among Rugila's jewels it found the golden orb, a piece of booty from Byzantium; it held it in its claws and played with it, rolling it back and forth. And a voice said to Ezel: You shall not become a monk, you shall play with the globe like this animal! And he saw that the Hun god Kuttka had appeared to him, so he went and swung his sword towards the four continents, let his fingernails grow and became what he was to become, the mightiest king of the Huns and the "scourge of God" feared by all peoples. (36)

Many historians, (37) among them the most important, have always been inclined to report remarkable events as being caused by cats, and if they have failed to do so, one can at least observe that they generally showed a marked respect for cats. Lucian, in his Dialogues of the Gods, discussing the revered animals of Egypt, ridicules the Sphinx, the monkey, etc., but maintains a reverent silence about cats. This shy reserve in a writer known as a ruthless satirist can only be regarded as a tacit veneration of the feline race. And this is not the only case of special consideration for cats; for during sacrifices in the Temple of Hercules the Romans were anxious to keep dogs away, as their presence would have desecrated the temple and the sacrifice. This commandment was not applied to cats; it had probably already been seen that their peculiarly supple forms meant they could not be prevented from joining these august assemblies, where they were presumably most pleasing company. (38)

Even today, the Romans love cats very much. These animals are fed in a special way in Rome. The knacker, or certain men who buy the meat of fallen animals from him, carry it through the streets on poles covered with it at both ends. At a certain shout from these men, the cats come together from all buildings, from all corners, and stand in the doorways where the meat is thrown for them. The owner of the cats has to pay a small monthly fee. Something similar happens in Geneva, where cats are as numerous on the streets as dogs are in Constantinople.

The largest of these is the cats' meat business in London. Here, 200,000 pounds of meat are used weekly for this purpose (although dogs also participate in the feeding). A pound costs on average 2 and a half pence; thus 2000 sterling is spent weekly on maintaining the cats. Mayhew estimates that there are a thousand meat dealers for supply cats and dogs, each of whom earns at least 50 sterling annually; he puts the number of cats residing in London at about 300,000.

Muhammad (39), the great founder of Islam, was very fond of cats; it is said that he once preferred to cut off the tail of his robe on which his cat had fallen asleep, rather than disturb his beloved cat's sleep. Muhammad wished to honour Abdorraham, his most faithful and beloved follower, and gave him a title which is an everlasting adornment to the cat race. It was the custom among the Arabs to be called the father of something which was related to the virtues and talents of the person concerned.

Khalid, a guest of Muhammad, was given the nickname "Abujob," i.e., father of Job, for the extraordinary patience he showed during the journey to Medina. And Muhammad believed that among Abdorraham's most outstanding qualities there was none more worthy of respect than his love for his cat, which he always carried in his arms; he therefore gave him the title of "Abuhareira", father of cats, as his highest honor. (40) We can assume that this title must have been of particular importance, given the great care with which Muhammad considered all his steps; for he was too cautious to call one of his disciples, to whom he wanted to give authority over other people, the father of cats, had the cat not been held in such high esteem. This is consistent with what de la Porte says about the respect that the Muslims have for cats: When a soldier came home from war, he usually brought a cat with him, even if he himself had nothing to live on at home. The cats on the Zouaves' knapsacks indicate an African origin - in the former, the tendency towards comfortable rest is shown, in the latter, the sneaking, suddenly pouncing on prey style of fighting.