Mexican street cat with short forelegs.

TWISTY CATS - THE ETHICS OF BREEDING FOR DEFORMITY

The originator of Twisty Cats says they are cute. Breeders worldwide have said she is cruel to deliberately breed deformed cats. Texan laws say she is doing nothing illegal. Who is right and what are the ethics of breeding for deformity? This site is a commentary on breeding ethics - I am not a breeder of Twisty cats.

Important Note: It is necessary to understand that the European and American definition of "abnormality, "defect" or "deformity"" differs greatly. What American breeders see as a breed trait (short legs) many European countries condemn as a deformity. What is awarded high honours in the USA may be condemned in Europe.

THE ORIGINS OF SELECTIVE BREEDING

Throughout the ages, humans have been fascinated by anything that is visibly different. This is well illustrated by the vast array of modern breeds of dogs, rabbits, guinea pigs etc many of which were bred for looks rather than function. Even before full domestication, undesirable traits could have been removed from an animal population by culling certain individuals, thus removing their genes from the gene pool. After domestication, selective breeding became easier. This possibly included selective breeding for colour and shape of horns (lyre-horned cattle) which may have been important traits for religious reasons.

The concept of deliberately breeding for looks is chronicled as far back as biblical times when Jacob separated spotted animals from white animals. It no doubt goes back even to prehistoric times. Perhaps our ancestors found a wolf cub which looked different enough from other wolves that they kept it, and its tamest descendants, as novelties (later exploiting its traits as the domestic dog generations later). This must have happened again and again with horses, cattle, sheep, swine etc and it continues today. Colour and body type also makes it easier to distinguish between wild and domesticated animals - compare the looks of the primitive Przewalski horse and the selectively bred modern thoroughbred.

Our inborn curiosity, coupled with our ability to control the breeding of animals, must be tempered with a respect for an animal's health and for the ongoing health of future generations of those we selective breed because they are visually pleasing or are useful to us. For example, white turkeys are bred for hypertrophied chest muscles to provide us with breast meat. However, the extreme over-development of the chest can make it impossible for the birds to mate naturally and they must be bred using artificial insemination. This would not occur in nature because animals which cannot mate cannot pass on their genes and the trait dies out except for occasional individuals which appear due to recessive genes or recombination of genes.

THE REASONS FOR SELECTIVE BREEDING

Most breeders want to improve their breed. To want to improve a naturally evolved species perfected over many generations is part of human arrogance. The improvements are not to enhance the breeds viability in the wild, but to enhance its usefulness or appeal to humans. Humans improve species according to criteria of aesthetic appeal, yield of meat, milk, wool, more offspring etc or a temperament more amenable to being kept as pets or farm animals.

While horses may be bred for speed or ability to carry or haul heavy loads, pigs may be bred for fast maturation rates and large litter size. Dogs may be bred to be better guard animals or fighters while sheep may be bred for better wool and hardier lambs. But other traits may lead to a strain bred entirely for aesthetic appeal, e.g. the diminutive Falabella horse.

If domestic cats were bred for their functionality, only those which were proven hunters of vermin would be selected for controlled breeding. However, domestic cats are selectively bred as pets. Breeders seek to improve them according to aesthetic criteria while not adversely affecting health or temperament. However, human curiosity has often led breeders to look for novelties or curiosities which might not be viable in a natural environment. These are viable in a commercial environment.

This is not to say that cat-breeders are purely financially motivated. Most seek to improve upon the traits of existing breeds, for example to develop a better coat in Persian cats, to expand the colour range of another breed, to eliminate the incidence of hereditary illness in a breed etc. Some seek to perfect a body type - if the short nose of a Persian is desirable, then extreme flat faces are even more desirable as the ultimate expression of short-nosedness.

According to naturalist/biologist Roger Tabor in his text "The Rise of The Cat" (1991) "When selection was made for showing purposes, genetic disasters occurred. In cat breeds, physical mutations that were previously allowed to perish are now being developed merely for the sake of difference. Not all are harmful, but some are achieved at considerable cost to the cat."

For further information on selective breeding see Pros and Cons of Inbreeding

NOVELTIES AND CURIOSITIES

In the past, the human love of curiosities led to freak shows which exhibited two-headed calves, human dwarfs, bearded women, people with extra limbs, deformed limbs or missing limbs etc. Freak shows might be out of fashion, but the deliberate breeding of freakish individuals continues with animals. Most people feel sadness or outrage at the sight of an animal deliberately bred for a crippling deformity, but there is always a ready market of such breeds among those who want a novelty as a pet.

Mutants appear from time to time in litters of kittens. The mutant may have a different type of fur, folded ears or bobbed tail. Usually, mutant kittens with severe abnormalities die or are euthanized. Those with lesser abnormalities may trigger the interest of breeders. If it is otherwise healthy, this is not a problem, but if it is also a sickly kitten then its descendants (carry the desired new trait) will also be weak and breeders must work hard to introduce vigour into the breed using outcrosses while not losing the trait. Sometimes the mutation is inextricably linked with health problems and this poses an ethical dilemma.

|

|

|

Mexican street cat with short forelegs. |

Nature sometimes makes genetic mistakes. Kittens have been born with two heads (fused together) or extra legs due to incomplete separation of twins. Extra limbs can often be corrected by surgery, but animals with two fused heads rarely survive because of brain damage, but they are curiosities so the owner has tried to rear them. 'Cabbits' are genetic quirks (often, but not exclusively, found in the Manx breed) where the hind end resembles that of a rabbit rather than a cat. One sometimes reads queries in magazines asking 'What are Cabbits? Where can I find a breeder?'. Someone somewhere may currently be considering the breeding of Cabbits to meet the novelty-value market.

The Munchkin is often condemned as such a novelty. With its short legs, it cannot jump onto high counters or shelves although, contrary to some reports, in can jump. Many cat-lovers condemn it as deformed or freakish. However, between the two World Wars, several generation of short-legged cats occurred naturally in England. These were feral or stray cats and the line was lost during the Second World War. The cats apparently survived naturally. Evolution did not work to eradicate them. In a natural environment, short-leggedness might have allowed such cats to pursue rabbits into their burrows making them specialised hunters (there is no actual evidence of this occurring in the English cats of the 1940s).

In England in 1944, 4 generations of these cats were documented in the Veterinary Record by Dr. H.E. Williams-Jones. Only the front limbs were affected, while the hind limbs appeared to be of normal size and the cats' gait resembled that of a ferret. At rest, the cats sat upright. These cats were one of many established bloodlines which disappeared during World War II and the few surviving individuals had been neutered, losing the mutation altogether. (Reports of these short-legged cats being eaten by starving Britons is probably exaggeration; even in the most prosperous times, many interesting British mutations have simply not been propagated by cat fanciers.)

The modern Munchkin is a reoccurrence of this trait and on this occasion it has been perpetuated by breeders. It may be a freak, but this mutation has proven a viable freak in the past. More details on Kangaroo Cats, Squittens and Munchkin-type catns and recorded occurrences of these mutations can be found in Kangaroo Cats and Squittens Revealed

Tailless Manx cats occurred naturally and were perpetuated because of their isolated, island environment which prevented out-breeding. Human intervention occurred later when a naturally established breed was perfected. Tailless strains of cat appeared in Edinburgh in 1809 and in Pendarvis in Cornwall in 1837. The Cornish tailless cats appear to have been related to the Manx and to a Dorset variety of tailless cat. In 1909 tailless cats were known variously as Cornwall cats or Manx cats. Wirehaired, Rex and LaPerm cats with their curly coats are also natural occurrences and able to breed in an uncontrolled environment. The 'Buckfast Blue' cats around Buckfast Abbey in Devon were free-breeding, wavy-haired feral cats (predominantly grey in colour).

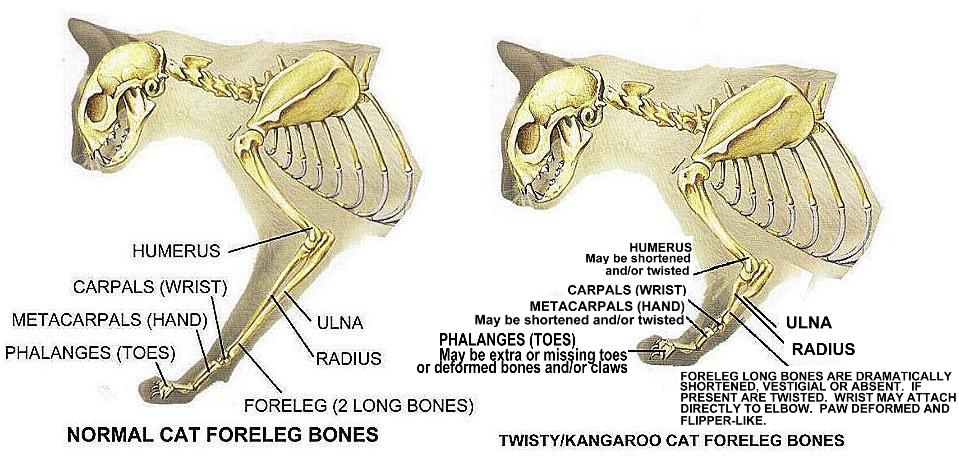

Twisty Cats, for those who have not seen the web-wide publicity and protest, have a condition called radial hypoplasia or the more extreme form, radial aplasia. The long bone of the leg is vestigial or absent and the wrists and paws appear to be attached close to the shoulder. In extreme cases, the cat has a flipper-like paw attached to the shoulder. The paws themselves may be deformed, absent or vestigial. The deformity causes locomotory problems for the cats which must either hop on their back legs like kangaroos or use their almost useless front flippers to hobble along. The foot and/or claws may also be deformed, causing further discomfort. The deformity has been likened to that caused by Thalidomide in humans. So far nothing is known about whether the cats have internal abnormalities as well. Without human intervention, the cats would be easy prey for other carnivores.

THE LINK BETWEEN POLYDACTYLY AND RADIAL HYPOPLASIA

It is strongly suspected tht polydactyly itself is caused by a number of different genes with a similar outward expression. There is some evidence for a dominant polydactyl trait which results in different structural changes to the usual expression of polydactyly and which affects the whole limb and not just the paw. The extra toes are not a problem, but the way the limb develops adversely affects the cats inheriting this gene. The trait is similar to human conditions associated with triphalangeal thumb and radial hypoplasia. The owners of the Twisty Cats had unknowingly used cats with this form of polydactyly and not the more common form. The breeder had after all been attempting to breed polydactyl cats and had produced kittens with radial hypoplasia as part of this breeding program.

As a result, breeders working with other polydactyl cats (including polydactyl Maine Coons) are now more aware of this harmful gene and will not breed from any cats with affected limbs. A number of years ago, foot defects cropped up the Abyssinian breed - ranging from twisted claws through to web feet, missing toes and other foot malformations in the same breeding line i.e. probably a single gene whose expression varied from minor cosmetic effect through to serious defects. Unfortunately, the creator of the Twisty Cats has gone the other way completely and has perpetuated a defect which reduces the cats' quality of life.

Those who see a cat with Radial Hypoplasia for the first time either think it has both front legs broken or notice that it sits up like a rabbit. They walk in a shuffling or scrabbling motion. There are varying degrees of the condition, these tips take a worst case scenario. Some affected cats are found among feral cat colonies, but unless the colony is being fed by someone they are unlikely to survive outdoors - they cannot hunt, cannot run from predators, traffic or malicious humans and cannot defend themselves if molested. In addition they are likely to be singled out for abuse because they are different and therefore "easy targets". The gene is therefore not one conducive to survival and nature would select against it. While those which occur can be cared for, it is not ethical to select for such a deleterious gene or to deliberately perpetuate cats whose lives will be blighted by serious disability.

DEFORMITY AND COMPASSION

What constitutes a detrimental deformity is an emotive issue. Should a deformed kitten be immediately euthanized or should it be placed in a nurturing home and prevented from breeding? How severe must a deformity be to warrant euthanasia? Can the cat live a good quality life in spite of its deformity? Many deformities elicit feelings of compassion.

Some people are aghast that kittens born without eyes are allowed to live. There are many blind cats living happy, healthy lives in secure indoor environments where they compensate for their blindness by having an acute sense of hearing and by greater use of their whiskers. We faced this dilemma with Smudge who was born with empty sockets and a strangely shaped skull. For the first several weeks there was a debate as to whether an eyeless kitten should be euthanized. Human compassion ensured that the guarantee of an excellent home for him. By the time he reached 7 weeks old the skull deformity indicated hydrocephalus and a deteriorating quality of life. The decision to euthanize was unanimous.

Despite their obvious deformity and the difficulties they face, there are unfortunately some people would like to see Twisty Cats bred purely because they are a novelty with certain adaptations that make them extra attractive as pets. They do not consider the cat's quality of life (unlike those who dealt with Smudge, the hydrocephalic kitten), they only consider the fact that the cat's helplessness and deformity make it look cute. They consider it particularly endearing when the cat adopts the upright pose, like a mongoose or prairie dog or rests its chest and forelimbs on a ledge (leaning on the bar) even though these are unnatural postures which the cat adopts because its normal posture is impossible. In short, the cats sit like this to ease or prevent the discomfort associated with their deformity.

DEFORMITY AND FUNCTION

I haven't seen a Twisty Cat in the flesh, only in photographs. However, I have had first hand experience of a cat with this type of deformity. 'Crooked Legs' was born in a colony of severely inbred feral cats and luckily her deformity was less severe than that observed in the Twisty Cat. Once her quality of life was assessed she was spayed so I will never know whether her deformity was a birth defect, caused by environmental factors, or an inheritable condition.

Crooked-Legs was mobile though there were limitations - she could not run or play in the same way as other cats. She could not cover up her own faeces in a litter tray. There were concerns about the claws on her front paws because she could not use a scratching post. She liked to rest with her front quarters elevated on a ledge and she often sat up on her hindquarters like a rabbit; this probably put less strain on her spine and was a more comfortable resting position. In addition she had a slight cranial deformity which might have been linked to the forelimb deformity. However, her forelimbs were not useless flippers and the vet's opinion was that she could expect a happy, healthy life in a good home with owners who were aware of her limitations and problems. However curious we were as to the nature of her deformity, the welfare of Crooked-Legs and of a potential future generation was paramount so she was spayed. She was judged as a one-off and not as a potential new and novel breed.

The same year, another deformed kitten came to my attention when a stray cat and her kittens were reported to us. One kitten, Sophia had a serious deformity. At 6 weeks of age, she had the front half of a normal kitten and the back half of a newborn kitten. A well-meaning person persuaded their vet to splint the legs in the hope of having them surgically corrected later, but the defect included the tail and bowel (Sophia did not produce normal stools, only a sort of brown, poorly set jelly). Sophia had only survived to 6 weeks because of maternal care and human intervention. It was natural to feel sorry for such a kitten, but the well-meaning person did not initially assess the kitten's overall health.

As well as locomotory problems there are other problems in cats with severely reduced forelimbs. The severe deformity of the forelimbs prevents the kittens from milk-treading which stimulates the flow of milk from the motherís nipples. Human intervention may be required to partially hand-rear severely afflicted kittens. The Twisty Cats web page reported that one kitten required its forelimbs splinted until a callus formed because the paw deformity and lack of a wrist-pad caused problems in learning to walk.

In order to walk, the cats must either bound on hind legs or hobble on all four limbs. Unlike kangaroos or extinct carnosaurs, which evolved over a long period of time, cats have not yet evolved the spinal adaptations or counterbalancing tail for a bipedal way of life. Their hindlimbs become well developed because they are the main form of locomotion (just as a weightlifter develops bulging muscles), but there are no skeletal adaptations to compensate for the almost useless forelimbs. The majority of breeders, when faced with such a deformity would assess an individual kittenís quality of life and either euthanase it or, if it can expect a reasonable life within its own limitations, would have it neutered to prevent further and perhaps worse deformities.

DEGREE OF DEFORMITY

How deformed does a cat have to be before that deformity is considered damaging? Can a tailless or bobtailed cat still balance, run, jump or hunt? The Manx and the various bobtailed breeds can do all of these things. Can a cat with folded or curled ears still hear? American Curls and Scottish Folds have good hearing. Can a short-legged cat hunt, run or climb, even if it cannot jump? The Munchkin has ferret-like gait and short-legged cats have proven that they can feed themselves and breed without human interference. Blind cats can adapt to life in a human household and some have even demonstrated the ability to hunt using sound alone. So far, no-one has deliberately bred eyeless cats - there is some unspoken agreement that this is an undesirable deformity. In a temperate climate, curl-haired cats are not at all disadvantaged. Hairless cats are somewhat more disadvantaged because they lack the insulating and protective features of fur, but they are not crippled by their hairlessness.

In the dog world, there are giant dogs and midget dogs. Already some cat breeders are trying to follow suit although giantism and miniaturism are considered by others to be deformities because they are so far removed from the normal, natural size range of the domestic cat.

In 1996 I spoke with a Persian breeder whose 14 lb stud tom was consistently siring miniature kittens (three quarters of all kittens he sired). There were concerns that the miniature cats might carry a recessive gene for normal size and might sire normal-sized kittens on miniature females with disastrous results. After several years of test breeding under veterinary and geneticist guidance, the miniature Persians proved to be healthy and vigorous. They exhibited two degrees of miniaturisation: Toy Persians which reached approximately 5 lbs and Teacup Persians which grew to approximately 3-4 lbs. They are healthy and exhibit no structural changes, only a change in size. Even among breeders there is no general consensus as to whether they are acceptable or not - to some they are, but to others they are undesirable freaks.

So when is a structural change radical enough that it cannot be the foundation of a new breed? What is acceptable and what is unacceptable? For some people, any alteration to the basic shape (or size) of the domestic cat is unacceptable. Other understand that cats show a natural diversity in type and that some changes in type are acceptable and may be perpetuated as long as the cats themselves are able to function as well as their 'normal' kin and are not unnecessarily handicapped.

There is a grey area between a harmless mutation and one which is damaging or renders the cat totally dependent on humans for its survival. Most breeders tread warily in this grey area; avoiding breeding from cats whose changed structure renders them cripples. Cats are valued for their independent nature (when they care to display it!) and a trait which detracts from this is generally considered undesirable as the basis for a breed. If the new and interesting structure is linked to more damaging traits, the grey area becomes a minefield. Can the damaging traits be bred out of the cats or is it inextricably linked? If it is inextricably linked, as in Manx and Scottish Fold cats, can the cats be bred carefully enough that the incidence of damaged individuals be eliminated or dramatically reduced?

Not all Scottish Folds have folded ears and this is necessary to keep the breed - and the individual cats - healthy. One early myth about Scottish Folds was that non-folded Scottish Folds often die between 2 - 4 years old from cancer, while those with folded ears do not. I have found no actual evidence to support this statement.

Munchkin breeders must take care to avoid problems associated with the short legs and a long back. A skeletal condition called thoracic lordosis, causes back pain and pressure. The condition is not confined to Munchkins and is not common in Munchkins, however inbreeding could increase its incidence. Munchkins appear to be predisposed to compressions in the chest, which can put pressure on the heart and lungs with sometime deadly results. Outcrossing can reduce these problems by widening the gene pool. However, Munchkins should not be outcrossed to heavily-boned (cobby) cats such as Exotics or Persians as the combination of heavy boning and short limbs can lead to cats which develop leg bones and elbows that are pushed outward. All in all, the Munchkin appears to have no more health problems than longer established breeds such as the Manx or the Scottish Fold which are also arguable "deformed" or the ultra-typed Persian with its blocked tear-ducts and constricted nostrils.

Just as there is a world of difference between short-leggedness and virtual absence of forelimbs, there is a world of difference between a single kitten born with a deformity and an entire breed deliberately bred for the that trait. What is acceptable in a single, non-breeding individual is not necessarily acceptable as the basis of an entire breed or variety.

The appeal of novelty value must be carefully weighed against the quality of life not of a single isolated individual (an 'accident of nature'), but of the entire breed line. This is the root of the outrage felt by most of those who have read about Twisty Cats. They occurred in a strain of polydactyl cats and radial hypoplasia/aplasia might be an extreme expression of the gene causing polydactyly in that cat population. Most breeders would work to find out which cats could be safely bred and which were carriers of the defect in order to avoid forelimb defects. In the case of Twisty Cats, the opposite has occurred - the breeder has actively selected for radial hypoplasia/aplasia in order to increase the number of Twisty Cats. Sadly there appears to be a market for "cute" deformed cats just as there used to be an audience for the human freak show.

THE ETHICS ISSUE

Unlike Crooked Legs (who was spayed) and Sophia and Smudge (both euthanized as kittens), further Twisty Cats have been deliberately bred. The breeding of deformed kittens is perhaps only excusable when two cats are bred together to investigate whether they have any detrimental genes. In the Ojos Azules, the deformities are so sad that alternative modern genetics methods of investigation are to be used to determine whether the genes for deformities are linked to the gene for the desirable blue-eyed trait. The gene giving the Ojos Azules blue-eyed effect turned out to be lethal in the homozygous form (when the kittens inherit two copies). Kittens with two copies of the gene are born dead. They have cranial deformities and are all white in colour with small curled tails (as though it has not formed fully). In the heterozygous form, the Ojos Azules are blue eyed non-white cats and often have a white tail tip. From the standpoint of breeding, it means breeders must select matings to avoid stillborn kitten i.e. a heterozygous Ojos Azules to a non-blue-eyed cat. This gives a 50/50 likelihood of offspring inherited the gene for blue eyes. This will mean some offspring have one copy of the gene while others will have no copies of the gene and hence will not have the blue eyes which is the Ojos Azules' defining characteristic. They can, however, be used for breeding to maintain other traits such as body type.

The responsible breeder not only decides the fate of the affected kittens in such a breeding program but ensures that the parents and any other kittens (which almost certainly carry the detrimental gene) are neutered; in fact other related cats may also be neutered if there is a high likelihood that they are carriers. Responsible breeders do this to limit the spread of damaging genes and to try to eliminate the damaging genes.

What then are the ethics of breeding for deformity? The responsible breeder strives to improve a breed without reducing its quality of life. The breeder in search of novelty strives to perpetuate the novelty with little regard for quality of life. Sadly, human nature is such that a crippling defect is viewed as an attractive novelty.

Random-bred rescued twisty kittens. Photo copyright Marilyn, Director, NEADY Cats |

Over the years, selective breeding has produced a catalogue of structural defects. Some are accidental and linked to desirable attributes such as coat quality. Others are an integral part of the cat's 'type'. The brachycephalic heads of the Peke-faced Persian (and the trend towards ultra-typing of other Persians) causes problems with breathing, drainage of tears due to distorted or absent tear ducts and dental problems. Some of these must be surgically corrected so that the cat can live some semblance of a normal life. However the large head size of the kittens means that caesarean delivery is often necessary and the high palate (due to the skull shape) means that the kittens must be hand-reared. This is an example of a mutations which would be self-limiting in the wild. The kittens would almost certainly not survive and in many cases the mother would die due to birth complications.

One of the oldest breeds, the Manx, suffers from a tendency to spina bifida and pelvic problems. Litter sizes are small because homozygous kittens (those inheriting the full expression Manx gene from both parents) die in utero. Most are reabsorbed, but analysis of those that arrive stillborn shows them to have gross defects. For this reason, Manx-type cats are used as laboratory models for certain neural tube defects (see Footnote). "Manx syndrome", appears in affected kittens during the first weeks or months. Although some breeders debate the lethality of the homozygous Manx or claim to breed tailless cats together with no ill-effects, many conscientious breeders prefer to use tailed cats (Manx variants) in breeding schemes and do not let kittens leave home until they have reached four months (16 weeks approx) of age with no signs of abnormality. In addition, breeders may dock kittens' tails at 4 - 6 days old to avoid another effect of the deferred lethal mutation. The tail vertebrae may become painfully ossified and arthritic, necessitating amputation. The Manx originated as a natural breed in an isolated area where its mutation became common due to inbreeding. Had it been created recently and deliberately, many cat fancies would refuse to recognise it because of its associated problems (see Footnote).

Roger Tabor write "Only the fact that the Manx is a historic breed stops us being as critical of this dangerous gene as of other more recent selected abnormalities.". Although "Manx Syndrome" is a variable set of symptoms, and spina bifida and other problems can occur in tailed cats and in tailless cats of non-Manx ancestry, what is of interest is the recognition of a breed whose defining characteristic is linked to a syndrome. The dictionary defines a "syndrome" as a group of symptoms that occur together to define a condition (though often only a subset of those symptoms may be present in any single individual).

A more recent natural mutation is the Scottish Fold. Bred for its folded down ears, homozygous individuals are subject to skeletal problems with the hind limbs and tail. These affect mobility and cause discomfort. To their credit, most breeders of Manxes and Scottish Folds carefully match cats to reduce the incidence of deformed or crippled individuals while maintaining the desirable attributes e.g. taillessness or folded ears. Purebred cats which don't exhibit the trait are used to reduce the likelihood of homozygous individuals. Not all breeders are this responsible towards their chosen breed. A few value profit above the health of future generations of cats.

According to former CFA president Richard H. Gebhardt breeders of Manx and Cymric face disappointments which include "crippling, spina bifida and abnormalities of the bowel and bladder, occur in proportion to the shortness of the cat's spine. Lumbar vertebrae do not materialize in Cymric in the same number as they do in ordinary cats. Therefore, breeders who persist in breeding the shortest possible two Cymric together may find their kittens suffering from too little of a good thing. [...] Only those fanciers with a deep concern for the Manx's well-being should be involved with them, for heartaches most frequently exceed triumphs [...] ." There is good reason to argue that the Manx should not be a natural breed. True, it produces tailless kittens quite naturally, but a pure breed should not produce defects from like-to-like breedings. This happens all too often with Manx. For as long as Manx have been recognized - and there were Manx taking prizes in British shows more than a century ago - the genetic defects have never been bred out of these cats."

Like Manx litters, Twisty Cat litters are small. In the Manx breed, small litter size is linked to the semi-lethal nature of the gene for taillessness. Homozygous kittens die in utero and are either resorbed or stillborn (as mummified kittens at whatever stage of development they reached). So far, nothing is know of the internal deformities which may be linked to radial hypoplasia. Small litter size suggests that it may also be semi-lethal. Those kittens which are born live may starve as a result of inability to milk-tread or inability to locomote. In the wild state such cats would be severely disadvantaged being unable to escape predators and unable to hunt properly so the deformity is, ultimately lethal.

In the case of spectacularly deformed cats, the driving forces for perpetuating them are curiosity and money. It is not in the interest of cats to breed individuals with vestigial forelimbs. The mutation is partly self limiting in that severely affected kittens will not survive without human interference; but the gene will be carried by cats which appear unaffected or only mildly affected. Further human interference - that of selecting affected cats and breeding from them - ensures that the mutation is perpetuated. Deliberate inbreeding is needed to perpetuate the mutation. Inbreeding has the disadvantage that any other detrimental genes become widespread in future generations.

The breeder of Twisty Cats believes that if scientists can clone a sheep then she has the right to breed cats which stand on their back feet. She plans to keep on experimenting to see what she comes up with next. There is a world of difference between a healthy cloned sheep and a deformed kitten. The sheep may have required human intervention to ensure its conception, but it was a viable individual at birth with no detrimental structural deformities.

EUROPEAN LEGISLATION AGAINST HYPERTYPES AND BREEDS WITH DEFECTS?

European bodies are concerned about the gradual shift towards American-style ultra-types (referred to as "hypertypes") in domestic pets. If made law in the member states of the Council of Europe, a number of cat breeds risk being banned: ultra-typed Persian/Exotic, Manx, Scottish Fold, Sphynx, Munchkin.

A controversial edict regarding genetically defective and ultra-typed breeds was issued by the Council of Europe which covers 41 member States including the UK. Though not (yet) law, the March 1995 draft of their "European Convention for the Protection of Pet Animals" would ban ear cropping and tail docking in dogs and potentially ban abnormal or defective dog and cat breeds. The Council recommends that if the breeders do not amend their own breeding practices, the affected breeds should be "phased out".

Chapter One, Article Five of the Treaty says: "Any person who selects a pet animal for breeding shall be responsible for having regard to the anatomical, physiological and behavioural characteristics which are likely to put at risk the health and welfare of either the offspring or the female parent." The resolution demanded that breed standards be rewritten to eliminate (by fiat if voluntary efforts failed) certain characteristics or potential genetic abnormalities (some of which were defining traits of a breed). It ruled that certain breeds, deemed to have defects, be discontinued.

As far as cat-breeding is concerned, the Recommendation by the Council of Europe's Convention for the Protection of Pet Animals encourages breeding associations to:

Reconsider breeding standards and amend any causing potential welfare problems. This means reconsidering the standards and selecting breeding animals taking into account aesthetic criteria and behavioural problems and abilities. It would ensure, by educating breeders and judges, that breeding standards are interpreted so as to discourage development of extreme characteristics (hypertype) which can cause welfare problems. In other words, it is up to breeders to curb, and even to reverse, the excesses of ultra-typing before matters are taken out of their hands by European legislation.

It might phase out and prohibit breeding, showing and selling of certain types or breeds whose characteristics are linked to harmful defects such as abnormally short face and abnormal positions of teeth (brachycephaly and brachygnathia in Persian cats) to avoid difficulties in feeding and caring for the newborn.

If severe defects cannot be eliminated, cat breeders would have to avoid or discontinue breeding of animals carrying semi-lethal (deferred lethal) factors (e.g. Manx cat where the homozygous state is lethal and the heterozygous state can be crippling), those carrying recessive defect-genes (e.g. Scottish Fold Cat where the homozygotic state causes hind leg/tail skeletal defects), hairless cats (lack of protection against sun, chill and environment), cats carrying the "dominant white" gene (significant disposition to deafness in blue-eyed white cats), the Manx cat (movement disorder, disposition to vertebral column defects, difficulties in urination and defecation, semi-lethal factor).

European breeders justifiably argue that any ban would be unfair since targetted breeds will be unaffected in countries outside of the Council of Europe. They argue that a global approach is needed to prevent cat breeds being taken to unacceptable extremes. Meanwhile, a small number of breeders will produce hypertypes, regardless of the adverse effect on the cats' health, in order to be competitive on the showbench. It really is up to judges and breed societies to curtail these excesses.

Cultural differences cannot be ignored. In Europe, common American breeds with structural differences (Scottish Fold, American Curl) or hybrid origins are considered, rightly or wrongly, to be undesirable. By contrast, American breeders are quick to adopt structural changes but remarkably reluctant to introduce new colours, already common and admired in Europe, into existing breeds. What one registry perceives as desirable or admirable, another seeks to ban as deformed, harmful or impure. Readers from both regions must understand that the definition of "defect" is country specific. One American breeder asked me what defects she could expect to see when breeding Sphynx. In the eyes of some European legislators, hairlessness (the Sphynx's defining trait) is the defect!

Some nations have accepted all or part of the treaty. Britain has rejected the restrictions, but the German government has accepted them. The German animal welfare law prohibits breeding that brings suffering to offspring, but has been poorly administered and planned for change. The German standpoint has been widely reported on the web and in the media. For example, Rex breeds are apparently banned from shows due to the abnormal coat and whiskers. The following summarises those applied to specific "defects" which may be the defining characteristic(s) of a breed. Note: What is termed a "defect" in the report may not be considered a defect elsewhere.

GERMAN RESTRICTIONS ON BREEDING OF CATS WITH DEFECTS

Some nations have chosen to abide by some sections of the treaty but to ignore others. Fifteen nations have agreed to the provisions of the pet protection treaty: Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, and Switzerland. Britain has rejected the restrictions, but the German government has accepted them and the other member European States may find themselves forced to follow suit. In Sweden a general act of Parliament prohibited breeding cats with defects that could be passed to the offspring. The German animal welfare law prohibits breeding that brings suffering to offspring, but has been poorly administered and planned for change.

The Germans have a succinct word for extreme breeding leading to health issues: Qualzucht ("torment breeding" or "torture breeding") which refers to the breeding of animals with characteristics associated with physical or behavioral problems.

The German animal welfare laws have been widely reported on the web and in the media. For example, Rex breeds are apparently banned from shows due to the abnormal coat and whiskers. The following summarises those applied to specific "defects" which may be the defining characteristic(s) of a breed. Note: What is termed a "defect" in the report may not be considered a defect elsewhere.

Tailless, Short-Tailed And Kink-Tailed Cats.

This covers various types of shortening of the caudal spine ranging from shortened rolled tails, shortened straight tails, stumpy tails, completely tailless cats or with an indention instead of the tail. It affects cats with Manx-type and Japanese Bobtail-type mutations and spontaneously occurring short-tailed cats of any breed.

Rationale: In short-tailed and tailless cats, locomotory disorders are likely and social communication is impaired. Manx cats are associated with a number of defects e.g. spina bifida.

Recommendations: Total ban on Manx-to-Manx AND Manx-to-Non-Manx breedings since offspring are likely to have pain, disease or defects. Japanese and Kuril Bobtails to be examined by a vet with regard to both increased sensitivity to pain in the tail area and possible fused vertebrae. Only pain-free cats to be bred. Medical Certificate required and all examined cats to be permanently identified by microchip or tattoo. Breed associations to keep stud books. Stud books and examination reports to be made available on demand (auditable). In the case of kinked tails, only cats certified negative for this defect permitted to be bred.

Dominant White and Albinism (Including Colourpoint)

A number of different genes govern white colouration in cats. Autosomal dominant white causes completely white fur colour and has complete penetrance for defective hearing, frequently combined with blue eyes.

Recommendations: For cats with dominant white a total breeding ban is recommended. Where the white colour may or may not be due to dominant white, a genetic test must be performed before breeding, as soon as an appropriate testing method is available. Test-matings cannot be justified, as impaired offspring are likely.

Rationale: Dominant white is associated with deafness and with defects of the tapetum lucidum (in eyes). Deaf cats are severely handicapped in their social and behaviour and in normal expression of predatory behaviour. Restrictions of vision, especially in semi-darkness and at night (the normal activity times of cats), increases this handicap. This is deemed a bodily defect that leads to permanent suffering.

Recommendation: Colourpointed cats (any breed) require veterinary ophthalmologic examination. Breeding allowed only with cats with unrestricted vision

Rationale: depigmentation of the iris and retina, absence of tapedum lucidum, impairment night vision, squinting or cross eyes (strabismus, nystagmus)

Recommendation: Other white or predominantly (over 50%) white cats require veterinary ophthalmologic and audiometric (hearing) examination. Breeding allowed only with cats with unimpaired sight and hearing. Microchipping and tattooing of examined cats, stud books (as previously).

Folded Ear

Relates to cats with folded ears (Scottish/Highland Fold, Poodle Cat etc) due to the incomplete dominant gene expression for "folded ears". This gene is also associated with bone and cartilage defects. [Note: The American Curl was not mentioned in the source work]

Recommendation: Total breeding ban.

Rationale: Cartilage and bone defects often found in homozygote and, to a lesser extent, the heterozygote. These skeletal problems cause locomotor problems, permanent pain, diseases or defects. The ears serve as a signal system in establishing social contacts, a function lost in fold-eared cats.

Curled Hair and Hairlessness

Applies to cats with abnormal fur such as partial or total hairlessness, shortened or missing tactile hairs. It includes the various Rex cats and the various Sphynx-type cats [Note: the source work did not specifically mention the Wirehair mutation]. Rex cats have reduced growth of the hair and undercoat and may lack guard hairs. Devon Rex are affected by partial or temporary nakedness. Above all, in Devon Rex and Sphynx the tactile hairs (whiskers/vibrissae) are curled (useless) or absent.

Recommendation: Total breeding ban on affected cats and modification of breed standards to avoid cats with missing, shortened or curled whiskers.

Rationale: Vibrissae are an essential sensory organ. They are important for orientation in the dark, in predation, in examination of objects and in social behaviour. Loss of functionality due to absent or deformed tactile hairs is a physical defect which limits normal feline behaviour in a way which leads to permanent suffering.

Munchkins, Kangaroo Cats

Applies to cats with chondrodysplasias (e.g. Munchkin) and microbrachy (kangaroo legs).

Recommendation: Abstention from breeding cats showing these defects. The breeding population to be monitored regarding vitality and functionality with particular attention to the intervertebral disks (spine) including x-rays (radiographs). Examined cats to be microchipping or tattoed, stud books etc (as previously). In the case of microbachy, only cats certified as negative for the trait may be used in breeding.

Rationale: Structural defect affecting function and preventing normal feline behaviour/locomotion.

Polydactyly

Applies to cats with polydactyly e.g. polydactyl Maine Coon and the American breed named "Superscratcher" which is deliberately bred for polydactyl [Note: I have never heard of a Superscratcher breed]. Polydactyly is an autosomal dominant and a semi-lethal defect.

Recommendation: Total breeding ban on cats showing these defects since defective offspring are to be expected.

Rationale: None was given, presumably the "semi-lethal defect"; certainly my own experiences have shown no problems with polydactyl cats and no adverse effects on their functioning.

Facial Defects

This applies to cats showing brachycephaly and brachygnathia (Persians, Exotics), also to any cats with misaligned jaws (skew muzzle), brachygnathia inferior (under-bite) and brachygnathia superior (over-bite). Brachygnathia is particularly associated with short muzzled breeds but may be found in other breeds. Cleft lip, cleft palate and related defects are associated with brachycephaly. The mode of inheritance is not fully understood.

Recommendations: Breeding associations to determine an index defining over-typing. Breeding ban on cats not meeting this index. Breeding ban on extremely short-nosed cats where the upper edge of the muzzle is higher than the edge of the lower eye lid. Health check required for brachycephalic individuals: examination for breathing problems, tear ducts (not draining), shortened upper jaw, dental problems. Breeding ban on cats showing one or more of the described symptoms as these would produce offspring with similar defects. Examined animals to be microchipped or tattoed, stud books kept etc (as previously).

Recommendation: Modification of the breed standard of brachycephalic breeds to avoid an overly pronounced stop, too high nose, too short muzzle etc. Preference should be given to cats with longer facial bone structure. Breeders to avoid breeding from individuals affected by brachygnathia, cleft palate and other facial defects.

Rationale: Depending on the degree of muzzle shortening, food intake and chewing can be impaired.

In Germany, an unsubstantiated fact (or propaganda) states that polydactyl kitten suffer a 50% mortality rate during the first 6 months and that polydactyl cats live in pain. In fact the kitten mortality rate in polydactyls is no different to that in normal-foot cats. Possibly polydactyly is still being confused with the severely disabling radial hypoplasia.

AMERICAN LEGISLATION?

American cat breeders are concerned that an equivalent "Convention for the Protection of Pets" could happen in their own country. Some humane societies, veterinary associations and animal rights groups would like to see comparable legislation on certain breeding practices (currently most are aimed at ear-cropping and tail-docking in dogs). The US government's Animal Welfare Act regulates conditions in breeding facilities, research facilities and shows., but breeding ethics remain the province of breeders and breed societies and are jealously guarded from interference.

So, at present there appears to be no comparable "legislation" (or potential legislation) in the USA although animal welfare organisations have voiced concerns against deliberate breeding of gross deformities such as Twisty Cats, while animal rights organisations additionally condemn many of the breeds/types targetted by the Council of Europe's Convention for the Protection of Pet Animals and for the same reasons (but in stronger language: "genetic disasters").

Responsible breeders are keen to point out that they not only minimize the potential for genetic abnormalities in their breeds, they raise money and participate in studies to find genetic markers for various diseases and to develop treatments and cures. Even so, some breeders are uneasy about seeing how far a certain look can be taken hence the slowly growing number of "Traditional" breeds.

In 2006, TICA proposed to clamp down on certain breeding trends. Their Genetics Committee report stated: "The Committee proposes that TICA does not accept any proposed breeds for Registration Only status that do not exhibit novel mutations. The current mutations would be reserved for currently recognized breeds exclusively. This would end the seemingly endless applications for "munchkinized" new breeds, and then deter the inevitable introduction of "rexed", "Bob-tailed" and Poly-ed" everything else."

AUSTRALIAN LEGISLATION AGAINST BREEDS WITH DEFECTS

In Victoria, Australia, The Animals Legislation (Animal Care) Bill was released by the Minister for Agriculture, the Hon Jo Helper MLA, on 11 Oct 2007. This included amendments to the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act (POCTA) 1986 that would outlaw a number of cat breeds.

15C Breeding of animals with heritable defects:

For the Schedule to the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1986 substitute Section 15C "Table of Diseases Caused By Heritable Defects". In cats, this means cats with the following must not be allowed to breed: Polycystic Kidney Disease (PKD); Mutations causing aplasia or hypoplasia of any long bone; Folded ears due to osteochondrodysplasia.

This effectively prohibits the breeding of Munchkins and Scottish Folds, but interestingly (and demonstrating the inconsistency of the legislation) it did not mention Manx despite the effect of the gene on the vertebral column. The concern is that other states will follow Victoria's lead; in the meantime it would remain legal to breed Munchkins and Scottish Folds outside of Victoria. (In addition, in 2008 the Australian government has banned the importation and breeding of Savannahs through fears that dilute serval genes would turbo-charge the feral cat population.)

BRITISH (GCCF) DRAFT RULING

In Britain, during 2009 the Governing Council of the Cat Fancy (GCCF) strengthened its anti-polydactyl stance (this primarily affects the Maine Coon Polydactyl and Pixie-Bob). While other World Cat Congress member registries accept polydactyly as a harmless trait in these breeds, the GCCF remained close-minded and insistent that polydactyly is a genetic defect. At the April 2009 World Cat Congress meeting in Arnhem, The Netherlands, the GCCF delegate responded "Never" when asked if and when the GCCF would accept polydactyly. In spite of discussions by scientists at the meeting, the GCCF's position is that polydactyls are at "greatly increased risk of deleterious impact" and therefore should not be recognized nor accepted in the (Maine Coon) breed. The GCCF disregarded a British report into polydactyly known as the "Edinburgh Study".

The GCCF have gone even further and produced a extensive draft rewrite to the Breeding Policy. This could be a knee-jerk reaction after recent TV documentaries and RSPCA condemnation of dog breeds based on defects or it could be partially in line with European legislation. The new draft includes the GCCF refusing recognition to any new breed based upon structural anomalies, this specifically includes shortened limbs, shortened or bent tails, polydactyl feet, bent or deformed ears, hairlessness, or any miniaturized breed. Additionally the GCCF will require each Breed Advisory Committee to have in place a breeding policy by January 1st 2011, to be reviewed by the Genetics Committee to ensure they are comprehensive and consistent with the GCCF's General Breeding Policy. This could affect existing breeds with traits that would be unacceptable in new breeds (eg the Manx structural abnormality). Will the extreme flattened faces and high nose leathers of Persians, or the increasingly narrow skulled Siamese be banned? Somehow I don't think the GCCF will go that far for fear of losing members. The GCCF seems incapable of distinguishing between a harmless cosmetic trait such as normal polydactyly and the the unhealthy extremes already being shown. Put more simply, the GCCF has opted for the easy route of discriminating against mutations while failing at the difficult task of curtailing ultra-typing.

The appearance of spina bifida and other defects in the Manx/Cymric breed has led to Manx-type cats being used in biomedical research into human spina bifida. The cats used are those which have the Manx gene (where the cats came from is another matter - such cats are bred specifically for laboratory use, though the founding stock must have come from somewhere). This constitutes deliberate breeding of damaged individuals.

"The Manx cat is bred for an absent or shortened tail, but additional deformities of the sacrum and spinal cord are common. Osseous deformities of the Manx cat are variable and range from spina bifida to sacrococcygeal dysgenesis." (Disorders of the Lumbosacral Plexus, by Marc R. Raffe and Charles D. Knecht)

In papers relating to the use of cats in biomedical research (i.e. in vivisection), Michael S. Rand, DVM & Paula D. Johnson, DVM (Assistant Veterinary Specialist- University Animal Care, University of Arizona, Tucson) write "Spina Bifida: The spontaneous occurrence of this condition in the Manx cat has been offered by many investigators as a model through which to study the similar condition in humans. Detectable amounts of a-foetal protein in amniotic fluid have been reported in human pregnancies with neural tube defects. Similar detection has been verified in the Manx cat with neural tube anomalies. The clinical syndrome varies and can include megacolon, urinary incontinence with secondary predisposition to urinary infection, locomotor disorders, uterine inertia and chronic cystitis, along with the wide variety of bony anomalies. It appears to be an autosomal dominant trait with incomplete penetrance. The near absence of hydrocephalus and other CNS lesions in the cat model dims total homology, but this is the best known and most homologous model to date."

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

DeForest ME, Basrur PK. Malformations and the Manx syndrome in cats. Can Vet J 1979; 20: 304-11.

Marc R. Raffe and Charles D. Knecht: Disorders of the Lumbosacral Plexus