OWNING AND KEEPING WILD CAT HYBRIDS (OUTSIDE OF THE UK AND USA)

This article looks at the regulations and restrictions on owning or possessing small wildcat hybrids in countries outher than the UK and USA.

Note 1: I do not own or trade wildcats or in wildcat hybrids and I cannot put readers in contact with anyone who sells wildcats or hybrids.

Note 2: The "Ashera" cat is not mentioned here; all known Ashera cats were found to be a fraudulently re-badged early generation Savannahs purchased in the USA.

Overview of UK Regulations

The importation and ownership of small wildcat hybrids in the USA is detailed in Owning and Keeping Wildcat Hybrids in the USA. The importation and ownership of small wildcat hybrids in the UK, sand the Dangerous Wild Animals Act 1976 is detailed in Owning and Keeping Wildcat Hybrids in the UK . A case study into the red tape surrounding the importation of new hybrid breeds into the UK is given at Ownership and Importation of Domestic x Wildcat Hybrids (UK)

In the UK, the keeping of wildcat hybrids in Britain is governed by the Dangerous Wild Animals Act 1976 (the DWAA) which requires the owner to have a licence in order to keep any animal listed on the Schedule. This is enforced by local authorities who have discretion in whether or not to grant a licence. This restriction affects wildcats and their F1 hybrids in breeding programmes for Bengals, Savannahs, Chausies and Caracats. For historical reasons, it does not affect Safari Cats, Oncilla hybrids or F silvestris hybrids. Clarification was issued that the F2 and later generations do not require a DWAA licence. The following small wildcats, and their F1 hybrids with domestic cats, are currently not restricted by the UK's DWAA (but may be restricted by CITES) Domestic Cat (Felis silvestris catus), Scottish/European/African wild cat (Felis silvestris: F s grampia, F s silvestris, F s lybica), Pallas cat (Manul) (Otocolobus manul), Little Spotted Cat (Oncilla) (Leopardus tigrinus), Geoffroy’s cat (Oncifelis geoffroyi), Kodkod (Oncifelis guigna), Bay Cat (Catopuma badia), Sand Cat (Felis margarita), Black-footed cat (Felis nigripes), Rusty-spotted cat (Prionailurus rubiginosus).

Roughly speaking, if the wildcat/domestic hybrid is 2 generations removed from a wildcat (whether excepted or not) it doesn't need a DWAA licence. In 2007, DEFRA (Dept for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs - Britain's equivalent of a Dept for Natural Resources) clarified the position of the Bengal, the first hybrid breed imported into Britain, and the Dangerous Wild Animals Act 1976: They are several generations removed from the wild ancestor, and currently kept in their thousands in the UK without serious problems arising. It was not specifically named on earlier versions of the Schedule but it technically fell within the catch-all listing of all species of Felidae (ie the cat family) except Felis catus, the domestic cat. Its effective inclusion in the list [of species requiring a DWAA permit] partly arose because the Schedule pre-dated the breeding of these animals in this country. Other cat hybrids also fell within the catch-all listing for Felidae.

Overview of USA Regulations

In the USA, restrictions on the ownership of hybrid cats varies greatly, not just from state to state, but also between counties within a single state. Some towns and cities have ordinances that restrict ownership of hybrid breeds within city limits. For British readers, this is equivalent to local by-laws banning Bengals and Savannahs in Chelmsford, but allowing them in Colchester 25 miles away. The restrictions may also vary according to which generation the hybrid is. Restrictions also depend on how close the hybrid is (genetically) to the wild parent: F1 hybrids are generally highly restricted while F5 generations are often considered domestic. To own any wild cat or wild x domestic hybrid in the USA, it is necessary to check the laws at town/city, county AND state level! This can become a minefield should the owner move house and find that their currently legal F4 or F5 "domestic" house-pet will be prohibited as a "wild animal hybrid" in their new locale or must be kept in a cage.

A number of states prohibit the import and ownership of hybrid cats excepting domestic breeds recognized by The International Cat Association. Others widen this to include recognition by other North American cat registries or by any "nationally or internationally recognised" registry. This could prohibit hybrids developed under the auspices of non-mainstream or paper registries such as the Rare & Exotic Felines Registry (REFR). Restrictions may apply to specified generations (most often F1) or to all generations including F5 and later.

CITES

In addition to regulations on owning wild cat species and hybrids, the international trade in some species is covered by CITES. This will also affects some hybrids (generally F1-F4 generations) being exported out of the USA or into the USA. Since all of the recognised hybrid breeds originate within the USA, it will only affect breeders wanting to export their cats out of the country and who will need an CITES export permit for affected hybrids (e.g. Serval hybrids). Although the currently recognised hybrid breeds were founded by wild cats bred and kept as pets in the USA, this does not exempt them from CITES regulations (if the parent species is listed by CITES).

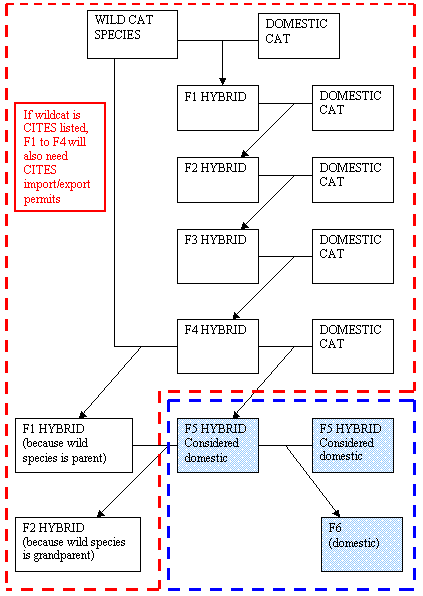

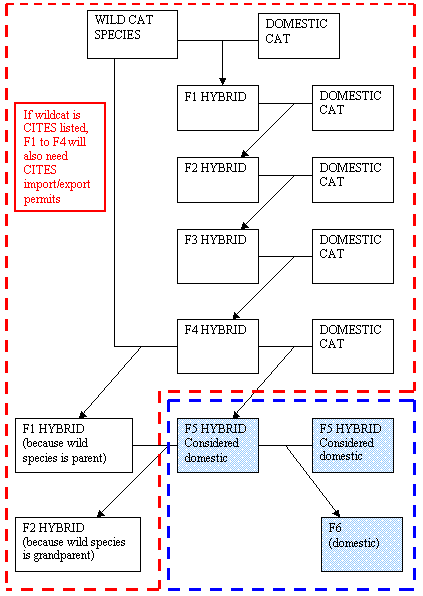

Many countries use the definition of animal hybrids that is used by the CITES Conference of the Parties resolution 10.17 (as revised at the fourteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties, The Hague (Netherlands), 3-15 June 2007). Under the CITES definition, a hybrid animal that has in its previous four generations of lineage one or more specimens included in Appendix I or II of the Convention shall be subject to the provisions of the Convention just as if they were the full species. For example, under this interpretation, the F1 to F4 hybrids of the Serval and the domestic cat (known as Savannahs) are treated in the same way as a pure-bred Serval.

In general, for hybrids involving CITES-listed wild cat species, the exporter must first obtain a CITES export permit regardless of which country the animal is being shipped to. The CITES export permit is copied to the overseas purchaser who then applies for a CITES import permit. Not all countries require a CITES import permit; for example shipping hybrids from the USA to Canada requires a CITES export permit, but not an import permit, but some Canadian states prohibit private ownership of F1-F4 generation hybrids. In terms of keeping hybrids as pets, some countries regulate the ownership (as well as the import) of the F1-F4 generations, while others set their own guidelines based on potential danger to humans or threat to native wildlife. This can vary from prohibiting all generations (either permanently or until the hybrids are better understood in the countries where they are legal) to restricting ownership of the F1 generation (these being 50% wild blood) to allowing ownership of all generations of hybrid that do do not exceed a certain weight.

As a cautionary note, several Ashera cats ended up in legal limbo after they were exported to the Netherlands. It was genetically proven that they were early generation Savannahs from the USA and exported by another party. As Serval hybrids, regardless of what breed name was used, they required both a CITES export permit (from the USA) and a CITES import documentation (in the Netherlands). The cats were seized and the original Savannah breeder was unable to get the cats back despite being able to prove their parentage.

In many of the listed countries, legislation was put in place after the Bengal was developed from Asian Leopard Cat hybrids. This can mean that the established population of later generation Bengals are treated as domestic cats, but earlier generation Bengals can't be imported. It can also mean that newer hybrids (Savannahs, Caracats) are restricted in some way.

Europe: Brussels (Belgium) Legislation Against Hybrid Cats (April 2019)

Being the home of the EU, it is not surprising to see legislation in Brussels. The banning of certain cat breeds was reported by The Brussels Times on 15th April, 2019. This has recently been decided by the Brussels government by approving at first reading of a preliminary draft of this new law. According to “La Dernière Heure” newspaper, the Brussels government has banned certain hybrid cat breeds from the city due to risks associated with their behaviour and health. The Bengal and the Savannah may not be bred or sold in Brussels anymore, because they are “not adapted to a life in captivity.” The Brussels Council for Animal Welfare is “using a sledgehammer to crack a nut” and failing to distinguish between early generation hybrids and those that are many generations removed from a wild ancestor.

Secretary of State for Animal Welfare Bianca Debaets (CD & V) was supported in her choice by two opinions of the Brussels Council for Animal Welfare. "The first generations of hybrid breeds do not behave appropriately for life in captivity, which can cause serious problems. On the other hand, they present the problem of lack of fertility and their gestation period is not the same as that of domestic cats. During mating, the risk of aggression is very high.” The ruling overlooks the fact that from the F4 generation onwards these cats are so far removed from the wild ancestor that their temperaments, behaviour and requirements are those of a domestic cat and show only the variability seen in non-hybrid domestic cats. It is only the early generation hybrids that display non-domestic traits, meaning there is no need to ban the later generations. So why can’t Brussels selectively ban the early generations, as happens in some US cities? Undesirable genetic traits have been eliminated from the gene pool by selective breeding.

According to Yvan Beck, a Brussels veterinarian. "This is a minority problem compared to other issues to be addressed in terms of animal welfare. During my career I was dealing with very few cats of these breeds and those that I could cure did not have these characteristics, "he explains. "At the Savannah level, it is true that it is a very independent cat but I have never observed behavioural problems. As for the Scottish Fold, there are now almost no issues. Regarding the owners of hybrid cats, what will they do when the law comes into force? Euthanize their cats? It's absurd. I will never accept euthanizing a hybrid cat that is in good health."

Indeed, once the law is applicable, keeping hybrid cats will be totally forbidden. Owners who wish to keep their cat will have to report it to the Brussels government in order to get a permit. The latter will give an opinion and if the report is negative, they will euthanize their animal. However, the Secretary of State emphasised that such extreme measures will be very rare. "The opinion will almost never require owners to euthanize their cat, except in extreme cases."

“We want to know where those cats are,” said Eric Laureys of the Debaets cabinet, “officially, there are currently 65 of those cats in Brussels, but there may be more.”.

Australia and new Zealand

In Australia, importation of cat hybrids of all generations are effectively banned. The Bengal breed was already established, but only at F5 and later generations. The Savannah cat was specifically prohibited as a potential threat to wildlife. This sets the precedent for all other cat hybrids. In Queensland, Australia, servals and their hybrids are declared pests under the Queensland Land Protection (Pest and Stock Route Management) Act 2002 and cannot be kept without a permit. Permits are not available for animals kept as pets.

New Zealand regulations are similar to Australia in that importation of hybrid cats of all generations are prohibited as being a wildlife threat.

In both countries, the Bengal cat was established before 1998. In order to import a new hybrid breed to Australia or new Zealand, a risk assessment must be conducted, but there is currently nil likelihood of proving to the relevant departments that a tiny level of wildcat genes from an F5 cat can't turbo-charge the invasive feral population! Unlike Australia, New Zealand may review the policy with regard to F5 generations. It should be borne in mind that Australia has a strong anti-cat movement and simply does not want any more cat breeds imported.

North America (except USA)

Regulations applicable to the importation and ownership of hybrids in the USA vary greatly, with legislation at state, county and municipal level. These are discussed in Owning and Keeping Wildcat Hybrids in the USA.

In Canada, the regulations also vary. For example, Alberta prohibits ownership of F1-F3 hybrids, but considers F4 and later generations to be domestic cats, while Saskatchewan appears to prohibit all generations of hybrid cat.

In Ottowa, Ontario, F1 hybrids are not permitted as pets (any licenced organisation importing one requires a CITES import permit), while F2-F4 generations required a CITES import permit, and F5 and later generations are considered domestic cats.

Authority to possess a "controlled animal" in Alberta may be granted to zoos, research facilities and wildlife sanctuaries, but not to private individual wanting to keep the animal as a pet. Schedule 5, Section 4(1)(h) of this the Wildlife Regulation "Controlled Animals" states:

(1) Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column [the cat-specific section is detailed below].

(2) Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule.

(3) This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal.

Schedule 5 (the list of Controlled Animals) lists under Section 34: "ALL CAT-LIKE (Family Felidae): Small Cats and Lynxes Genus Felis except the domestic cat (Felis catus); Clouded Leopard Neofelis nebulosa; Big Cats (Leopards, Tigers, Jaguars, Lions) Genus Panthera; Cheetah Acinonyx jubatus."

British Columbia's Ministry of Environment only regulates those animals that, in their opinion, pose the greatest threat to human health and safety. Municipal by-laws can be more restrictive than the provincial regulation so the "Controlled Alien Species regulation" should be considered a minimum standard across the province.

Wildlife Act: Controlled Alien Species Regulation

Section 1 (1) of the Wildlife Act defines "controlled alien species" as:

(a) a species designated by regulation under section 6.4 of the Wildlife Act as a controlled alien species, and

(b) hybrid animals and fish that have an ancestor within 4 generations that is a species designated as a Controlled Alien Species.

Note: all subspecies within the species listed in Schedule 1 and 2 of the Controlled Alien Species Regulation are also considered Controlled Alien Species.

At March 2010, the controlled species of cat were listed as Cheetah, Leopard, Lion, Jaguar, Tiger, Clouded Leopard, Snow Leopard, Eurasian Lynx, Iberian Lynx. Small cat species are not currently listed as controlled on the Government website, but there is a disclaimer that the online version of legislation may not be up-to-date (plus the species might be subject to CITES controls).

If the Controlled Alien Species was in British Columbia on or before March 16, 2009, the owner had to get a permit for the animal before April 1, 2010. Conservation Officers and constables have the authority to seize or destroy Controlled Alien Species where there is good reason to do so e.g. where the animal presents an immediate threat to the health or safety of a person. A conservation officer or constable may seize a Controlled Alien Species if the person in possession of the animal (a) does not have a possession permit, (b) contravenes any condition of their permit, or (c) contravenes any aspect of the Controlled Alien Species Regulation.

South America

In Brazil it is illegal to own exotic animals, but hybrids of any generation are currently considered domestic and legal to own.

It should be noted that indigenous peoples in rural or isolated parts of South America tend to be self-regulating and may keep native small wildcat species and naturally occurring hybrids as pets (these are animals orphaned through subsistence hunting or that scavenge in or around villages), this is part of a traditional lifestyle and falls outside of the cat fancy or the organised pet trade.

Asia and Far East

Import and ownership of F1-F4 generation hybrids into Japan is legal, but are treated as exotic species in terms of quarantine if imported into Japan. F5 and later generation hybrids are considered domestic and fall under the Pet travel Scheme. This aligns with CITES definitions.

Singapore legislation does not currently appear to cover hybrids, but it appears to closely conform to CITES. The import of animals into Singapore is regulated under the Animals and Birds Act. Singapore's Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act, revised 2008, Chapter 92A enacts CITES restrictions which also apply to F1-F4 hybrids. All import of CITES-listed animal species for commercial and personal purposes require CITES permits obtained from the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority (AVA) and must be accompanied by the CITES export/re-export permit from the exporting country. Singapore's Animals and Birds Act is primarily concerned with preventing the introduction or spread of disease and with welfare standards and currently does not mention ownership of hybrids.

You are visitor number