|

|

THE SHADY STORY OF THE SINGAPURA

According to cat fancier lore, the Singapura's tale is a feline Cinderella story. The Singapura, or Singapore River Cat, was discovered on the streets and in the drains of Singapore and was whisked back to the USA to be admired on the show-bench.

As it later turned out, the breed owes more to Texas as a place of origin than it does to Singapore. And in recent years, DNA studies have determined it to be almost genetically identical to the American Burmese with very little genetic diversity. With so many breeders refusing to expand the Singapura gene pool through outcrosses or new imports, this man-made breed is also at risk of being inbred into extinction.

DISCOVERY OF THE SINGAPURA, VERSION 1

Version 1 of the Singapura history says it was discovered by Tommy Meadow and her husband Hal while they were living in Singapore. Hal worked for an oil company and had been transferred to Singapore in 1972. Tommy was an established Abyssinian and Burmese breeder. In 1974, they relocated to Singapore Some time after they arrived there, Tommy, a former Cat Fancier's Federation all-breed judge, became registrar for the Singapore Feline Society (SFS). She apparently heard about a small, brown-ticked feral cat from other members of the SFS. It was known as the "drain cat" and had apparently been seen in the area since at least 1965. It was apparently quite different from typical bobtailed Singapore street cats.

According to the Meadows, they spied their first Singapura, outside a Thai restaurant in June 1974. This was a small, brown-ticked female kitten they named Pusse (with an accent mark over the e). About a month later, they apparently found a litter of four kittens near the waterfront and took a female and a male, whom they named Tes and Ticle. In April 1975 the Meadows returned to the United States with Tes, Ticle, and Pusse, and with two of Pusse's kittens; Gladys and George (sired by Ticle). These were given the 'Usaf' suffix to their names.

They claimed that the three brown-ticked cats were native Singaporean "drain cats", whose small stature was due to generations of living in storm drains, and began promoting a new breed they called the Singapura. The Singapura exhibited the ticked tabby pattern of Abyssinian cat and the semi-albinism colour and body type of the American Burmese. A female Singaporean cat named Chiko (found in a cat shelter and not a street-cat) was imported in 1981 that broadly fitted the breed standard apart from being part-tailed. Her finders, Brad and Sheila Bowers, claimed to have seen Singapura cats elsewhere in the city.

Back in the USA, it seems that Tes was mated to sibling Ticle resulting in a male called Wun Hung Lo who was later mated back to his mother. Tes was then mated to her nephew George, resulting in mostly male offspring. When Wun Hung Lo was old enough, he was mated back to his mother. Meanwhile, Ticle was neutered and Pusse lost several litters due to uterine inertia, a condition she passed on to her female descendents.

TICA recognised the Singapura in 1979 and the CFA in 1982. They were recognised as a "natural" breed.

SOME INVESTIGATIONS

A reporter for The Straits Times in Singapore named Sandra Davie; a longtime official of the Singapore Cat Club named Lucy Koh; and an American Singapura fancier from Georgia named Jerry Mayes then enter the scene.

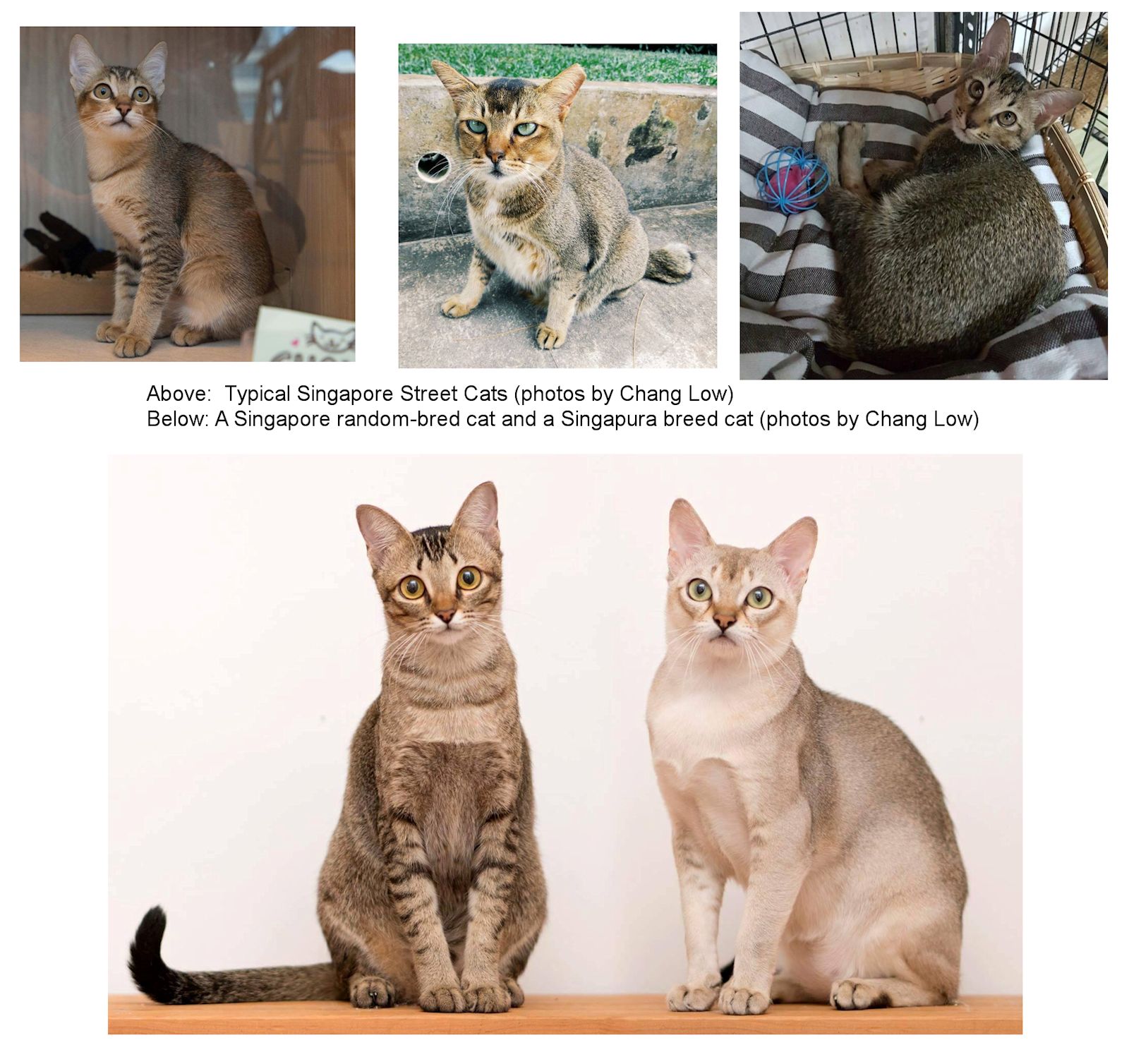

Lucy Koh located a genuine "Singapura," named Baby Bull, but unlike the Meadows' small, delicate cats, "Baby Bull" was a large, dark ticked cat. Early Singapura hunts by western fanciers located "Bull" and then "Baby Bull" (found on behalf of Jerry Mayes), but very few cats that resembled the Singapura breed. A "Limau Kohlum" (red cat) was found, as were several strongly ticked, dark cats dubbed "Wild Abyssinians" because they resembled large, strongly marked Usual (Ruddy) Abyssinians. Burmese-type, Korat-type and colourpoint cats were also found.

|

|

Mayes went to Singapore in 1987 and the local people told him they had never seen the type of cats he described. His investigations led him to the Primary Production Department of the Ministry of National Development where he discovered importation papers for five cats that the Meadows imported into Singapore on November 1st, 1974 from the USA. These included Tes, Ticle, and Pusse (also known as Tess, Tickle and Puss). Quarantine papers listed the cats as two Burmese and three brown Abyssinians (or Aby-Burmese crosses). The Meadows later claimed the latter referred to the cats' brown-ticked appearance, not their breed. Four months later, on March 3rd, 1975, Tommy Meadow arrived in Honolulu with six cats, which included Tes, Ticle, Pusse, George and Gladys.

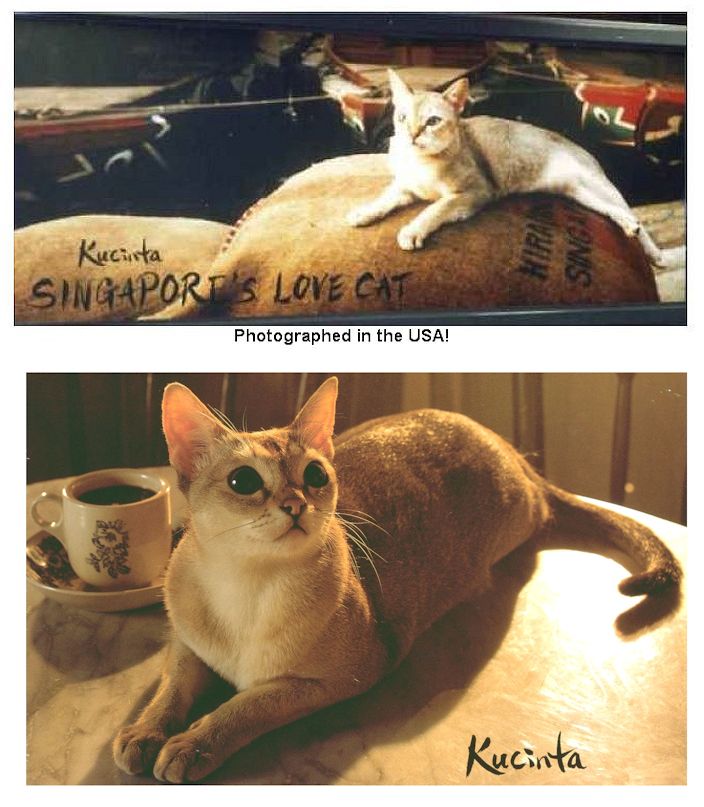

Lucy Koh was in possession of a copy of a personal letter that Tommy Meadow had written to the editor of Cat World magazine in March 1975, a month before leaving Singapore. It appeared that Meadow planned to achieve fame and notoriety by passing off American-bred cats as a native Singaporean breed. As the Singapura, and its Cinderella story gained credence in the west, Koh wrote to American and British cat magazines, trying to give the true story of the breed. No-one took much notice until the 1990s when the tourist board of Singapore made the Singapura the island's national mascot (Kucinta, the Love Cat of Singapore), complete with poster campaigns and sculptures along the riverside.

The tourist board asked Koh's advice and she told them the truth - the Singapura cat was an American-bred hybrid. The tourist board didn't want to hear that, so they went to Tommy Meadow for a better story. At that point, Koh provided all of her information to reporter Sandra Davie who wrote an article discrediting the Meadows' story. Far from rescuing street kittens, Tommy Meadow had created the breed in Houston, using Abyssinians and Burmese. Tommy Meadow died in 2004, but left behind quite a bit of information, not all intentional, that allowed others to piece together the true story.

THE REVISED HISTORY OF THE SINGAPURA

Tommy Meadow was called before the CFA board in February 1991 to explain how Burmese and brown Abyssinians exported to Singapore in 1974 had become Singapuras in 1975. In her new version of the story, she claimed that Hal had been sent to Singapore in 1971 on sensitive work for an oil company. This work was so sensitive that no-one was supposed to know he had been there so the Meadows had withheld this part of the breed's history.

While there, Hal had adopted three, brown-ticked cats and paid a crewman on a US-bound ship to ship the cats to Galveston where Tommy would collect them. Hal stated that these original cats, two females and one male, were not Tes, Ticle and Pusse. A fourth cat (female) was shipped by boat in either late 1971 or early 1972. The four cats were his pets found in and around the Lo Yang district of Singapore, on the docks. They had no import or export papers and no record of their origin, but Hal could prove he had been in Singapore in 1971. There were also no records, veterinary or otherwise, to indicate that those cats had ever existed in the USA, and Tommy couldn't even recall their names!

Tommy said that one of the original four 'boat cats' did not survive. She had been so intrigued by their brown-ticked sepia colour that she let them breed, though she kept no records because she hadn't intended to create a fancy breed. She described the original cats as looking like Singapuras, although one or two of them had kinks in their tails. The surviving three boat cats produced several offspring, one of which was allegedly named Sassy Face. Tes, Ticle, and Pusse were 3rd generation.

When Hal went back to Singapore in Autumn 1974, Tommy went with him. Expecting to be living there for some years, they took six cats with them, including the 4-month old grandchildren of the cats that Hal had shipped to Houston in 1971. The grandchildren were Tes, Ticle, and Pusse and according to their import papers they were Abyssinian-Burmese crosses. Along with Tes, Ticle and Puss, she took a blue Burmese female and a neutered sable Burmese (Fat Cat). The blue Burmese was spayed soon after arrival in Singapore. The subsequent breeding between Puss and Ticle was unplanned because the cats were so young. The kittens were George and Gladys, plus a third kitten that remained in Singapore.

According to Tommy, 'someone' in the Singapore Feline Society (SFS) (later the Singapore Cat Club) suggested that the brown-ticked cats resembled a local variety of street cat and that they would make an attractive new breed. The SFS apparently gave the three cats initial registration status as Singapuras. According to Lucy Koh, Tommy Meadow - who was registrar of the SFS! - created the breed standard herself and had "revised and made alterations to registration procedures."

In the 1950s, Tommy had bred Abyssinian cats, but denied she had been breeding Abyssinian cats at the time she allegedly received the Singapore cats. When the 'boat cats' arrived, she had an old Burmese male who was later put down and then a pair of Burmese kittens (Margaret and Fat Cat). Fat Cat was neutered and allegedly accompanied her to Singapore.

Tommy admitted that Burmese had been used in test matings to isolate the solid brown gene, but said none of the progeny of those matings had entered Singapura bloodlines. The Meadows had felt they could eliminate solid brown by test-mating the males. When this didn't eliminate the rogue gene, they also had to test-mate all of the females. Six additional cats were found to be carriers and eliminated from the breeding programme.

The CFA only heard the Meadows' testimony and basically did nothing. Meadow went unpunished and the Singapura remained a 'naturally occurring' cat and not a 'hybrid' cat. The CFA justified this inertia by saying "Everyone generally agrees that the gene pool that created the Singapura has always been in southeast Asia. Naturally it came from the Burmese gene pool, the Copper Cat has been there since 1350 that we know of, and the Abyssinian. Whether they mated on the streets of Singapore or whether they mated in Michigan, it doesn't really matter. Besides, there was now at least one documented Singapura foundation cat that had been found in Singapore, therefore even with none of the cats the Meadows brought in, we still have a legitimate cat from Singapore behind our Singapuras."

PADDLING IN THE SHALLOW SINGAPURA GENE POOL

The Singapura was founded from a very small number of cats. Careful selection to establish the colour to 'breed true' further means it is now one of the least genetically diverse cat breeds. They are bred only in sepia (Burmese brown) ticked tabby. Solid brown cats kittens occurred in early litters due to a recessive gene inherited from Tes and Ticle. Any Singapuras that carried the solid colour were removed from the breeding programme.

Being derived from an extremely small gene pool has meant a serious degree of inbreeding, practically to the point where the cats are clones. Litter sizes are small and some breeders have reported fertility problems in Singapura studs; these problems are characteristic of severe inbreeding. It has also made recessive genes and heritable conditions widespread in the breed. Pusse had the heritable condition uterine inertia (weak uterine muscles that cannot push a kitten from the womb), hence some Singapura females require caesarian sections. The recessively inherited PK-def (Pyruvate Kinase Deficiency) is also present in the breed.

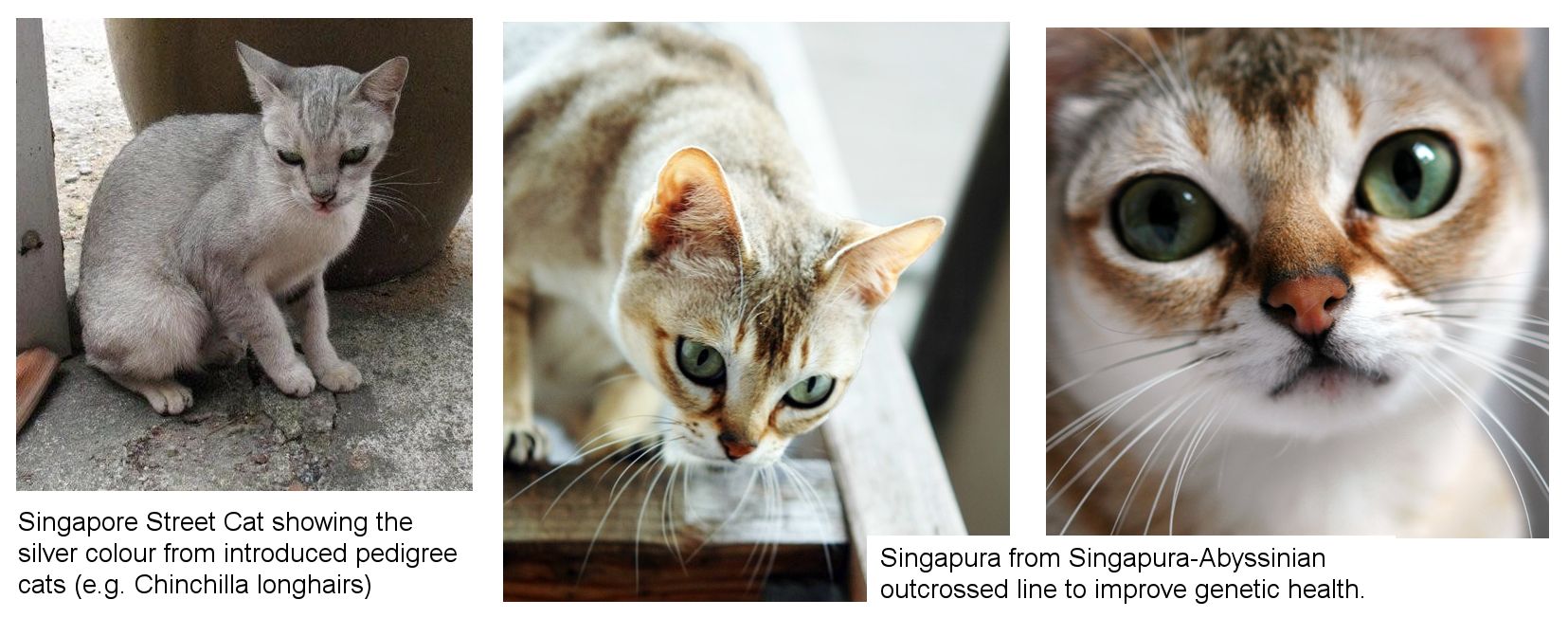

Bobtailed or part-tailed Singapuras have also cropped up, due to one of the few genuine Singaporean cats introduced into the breeding programme, probably Chiko. Almost all Singaporean street cats are bobtailed, making the Singapura's "Cinderella story" even more unlikely.

Longhaired Singapuras have also turned up in the past. The Usaf Abyssinians who were to become (or were to produce) Tes, Ticle and Pusse were almost certainly related to Raby Ashanto or to Raby Chuffa of Selene (Abyssinians that carried the recessive longhair gene). Linechasing finds that other Usaf Abyssinians were related to the Raby cats, for example Selene's Pogo of Usaf, or Blue Grass Vanilla of Usaf. The occurrence of longhaired purebred Singapuras in the early days was a (not so) well-kept secret. Current Singapura breeders would probably dismiss them as coming from unauthorized outcrosses rather than coming from recessive genes from the breed's Abyssinian ancestor.

During the 2000s, there were several DNA studies into the breeds recognised by TICA and/or the CFA. The Singapura was treated as being a natural breed from Singapore. The DNA studies found it to be closely related to other Southeast Asian breeds including the American Burmese, Havana Brown, Korat and Siamese. You might argue that this is because all of these originated naturally in SE Asia. Lipinski et al found that the Singapura and American Burmese formed an indistinguishable pair. This means the Singapura is pretty much a variety of American Burmese! In strong contrast, genuine random-bred cats from Singapore were found to be a genetic mix of Southeast Asian and European cats, possibly as a result of maritime trade. In Europe, ticked colour varieties of Burmese are known as Asian Shorthairs and were derived through outcrossing Burmese to other breeds. When it comes down to it, the DNA studies indicate the Singapura was created in the same way and shares very little genetic content with genuine Singaporean cats.

The follow excerpts are from personal correspondence with Dr Brigitte Leonhardt (Wolfsburg, Germany) in April 2005. Dr Leonhardt is a zoologist with more than 50 years of research in the Ticked coat patterns of wild, feral, and domestic cats wrote an article about the Tabby Cats of East and South East Asia ; where she lived for some years. After she saw the first articles about the Singapura, she knew at once that the pattern must have come from a breed-Aby. “What I did not know I learnt from Silver Ticked Tabby Burmese breeder Dr. Terence D. Lomax in New Zealand where I spent more than 12 three-months winter. He bred the (brown) seal Ticked Tabby Burmese and told me that such a cat was called Singapura in the States.”

Dr Leonhardt had read of one of my earlier articles about finding no warm ivory-coloured Singapuras in Singapore and knew that breed purists would accuse me of not looking in so-called pockets where the cats could be found. She wrote “Well I did look into them for years not only in S[ingapore] but all over the island and the surrounding other islands (like Riau group). Only wild Abys [brown ticked tabbies] can be seen there.”

Curious to see how the Singapura might have been bred, she started her own experimental breeding programme. She mated a New Zealand Seal Silver ticked Burmese to a French Singapura stud and was very lucky to get 2 Silver Burmese and 3 females, all phenotypically Singapuras of show and breed quality. She went on to breed a number of other litters with similar results.

“I talked to Mrs. van den Berg, who nearly wept, called herself a purist and Tommy Meadow as her best friend, spoke of politics etc. Here the breeders are also split [. . .] Often breeders also get carried away with their love of their breed, [caring] nothing for such a sober research. T. Meadow, though a gifted breeder, never called her cats seal, not to bring people to suspect Burmese. I bet you would be interested in my six page article, which I did not dare to offer the Singapura Club GB, they, who are not permitted to mate to cats, even Burmese like the Singapura definitely is genetically, might lynch me. Dutch breeder Margaret Monderson of Eindhoven Holland showed a Seal Ticked Tabby from her Cinnamon programme which the US judge promptly judged as a fine Singapura. Margaret was the first to establish the genetics of the Singapura.”

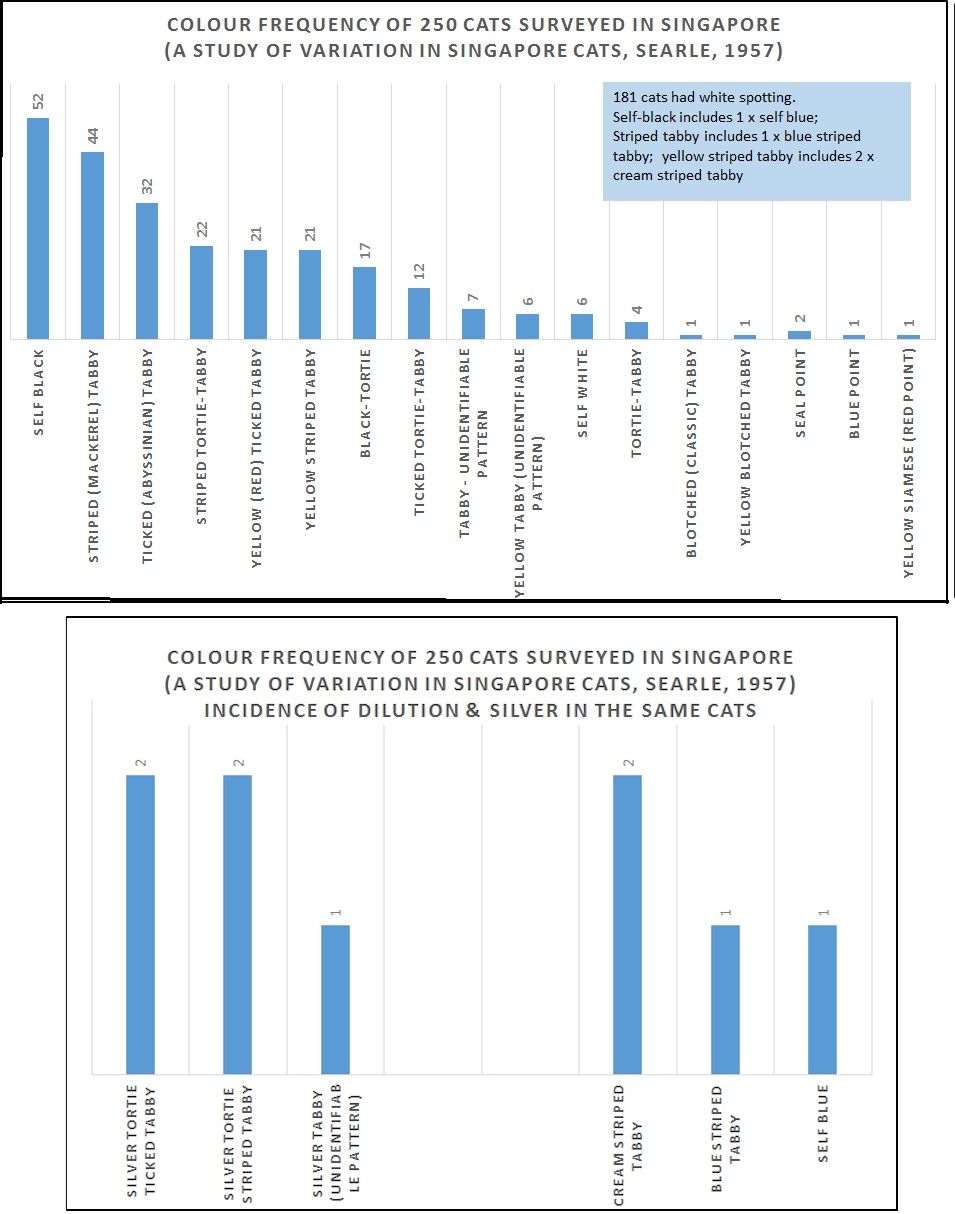

PREVIOUS SURVEY OF SINGAPORE CAT COLOURS AND PATTERNS

A G Searle conducted a survey of Singapore cats in 1957, reporting his findings in “A Study of Variation in Singapore Cats” in 1959. His study was one of a series on different “alley cat” populations to find out if there were regional differences in type and whether this was due to natural or artificial selection. He surveyed 250 cats – 80 living cats from kampongs on the outskirts of Singapore city and 170 dead cats from the City Animal Infirmary (stray or unwanted cats taken for destruction). He found kinked tails to be widespread (approx. 70%), varying from slight kinks at the end to tight bobbed tails, while 31% lacked either one or both upper premolars or 1st upper molars. The yellow gene (“red” in modern parlance) was present in about 30% of cats. I have summarised his findings in two graphs.

While ticked tabby is a common pattern, he did not record any cats with the Singapura colour. He found only white, black, blue, yellow (red) and cream, plus silver, plus a high incidence of white spotting. Searle was vigilant for novel mutations and would certainly have reported any new colour he found. This supports the view that the Singapura’s colouring was unlikely to have originated in the Singaporean cat population, but was introduced.

SINGAPURISM

If the Meadows contended that the CFA-recognized Singapuras were truly the same as can be sighted on streets in Singapore, why did they object to further foundation cats being imported from there? In other words, why were they so protective of what was supposedly a natural breed? Hal Meadow claimed to have no objection to new imports as long as the CFA could ensure that the imports met the Singapura breed standard and had no undesirable recessive genes. He claimed that even minor variation would harm the breed.

When the problems of a limited gene pool were explained to him (using the American Burmese and Egyptian Mau as examples), Hal denied that the problems were a result of limited gene pools. He claimed they were due to breeders' failure to ruthlessly cull affected cats, and affected breeding lines, from their breeding programmes. He claimed breeders continued to breed from affected lines in order to produce show winners: "You can not prove that the problems come from narrow gene pools."

As a result, purist Singapura breeders (those who value genotype over phenotype or genetic health) would rather see their breed inbreed itself into ill-health and extinction than introduce new blood. Such breeders have lost sight of the fact that the Meadows' Singapura was never a naturally occurring cat from Singapore, but was a man-made hybrid breed. Additionally, breeds are defined by phenotype (appearance) and as long as the look is maintained, crossing to another breed of compatible type and colour does not mean the offspring are moggies. If they look, behave and reproduce as Singapuras then to all intents and purposes - appearance being what defines a breed - they are Singapuras.

Most registries and breeders remain unreceptive to the idea of crossing to other breeds. This, they claim, would damage the integrity of the Singapura. It's common to see Singapura adverts stating that cats will not be sold to anyone involved in outcross programmes. Careful outcrossing may become unavoidable in the near future due to the inevitable inbreeding caused by the very small foundation stock. A number of experimental Burmese-Abyssinian crosses have closely resembled the Singapura in colour and type. In Continental Europe, some Abyssinians so closely resemble the Singapura that judges have suggested they be registered as Singapura foundation cats to expand the gene pool.

In the UK, the GCCF currently allows outcrosses to combat the excessive degree of inbreeding in Singapuras. Naturally Singapurists (the cat fancy's equivalent of religious fundamentalists!) are predicting the end of the world, or at least the end of the breed, as we know it, but outcrossing is essential due to the limited foundation gene pool. Outcrosses must not carry longhair, white spotting, PK deficiency or any other identifiable (by blood test) genetic disorder. Permitted outcrosses are:

(a) - Shorthaired ticked tabbies of Singapura type imported from Singapore and neighbouring countries.

(b) - Abyssinian cats in the following colours: usual/ruddy, sorrel and chocolate (excluding silver or orange series)

(c) - Korats

(d) - Non-pedigree Domestic shorthairs of Singapura type and colours black, brown or brown ticked tabby.

Singapura variants (e.g. non-agouti or incorrect colour) may be used in the breeding programme, but cannot be registered or exhibited as Singapuras. Those that have an approved outcross in their 3-generation pedigrees are defined as "Singapura Type" cats.

In Europe, some progressive breeders have openly outcrossed to Abyssinians; the grandchildren of the outcross being used to expand the Singapura gene pool. Despite the cats being physically indistinguishable from pure Singapuras (and a great deal healthier genetically), those breeders have been publicly hounded by purist/fundamentalist breeders who vilify the outcross cats as moggies. There seems to be some secret outcrossing going on as well, because some of those progressive breeders have allegedly been offered false pedigrees that would have allowed their outcrossed cats to be registered with the CFA as pure Singapuras.

The Singapura continues to have a lot of shady goings on. Unfortunately the ultimate victims will be the cats themselves.

|

|

DR. BRIGITTE G. LEONHARDT INVESTIGATIONS INTO, AND COMPARISON OF, THE SINGAPURA, TICKED BURMESE AND SILVER BURMESE

Dr. Brigitte G. Leonhardt, a zoologist with a special interest in the agouti pattern in wild and domestic cats, published a study called “The Agouti Pattern - A Study of Burmese and Singapura Cats” in German. This is a summary.

Leonhardt loved Abyssinian cast, but had become enamoured of Burmese cats, especially the ticked Burmese, while in New Zealand. She visited Dr. Terence D. Lomax and fell in love with Cineole Tigerlily, a seal silver Burmese, one of his first champions. In Summer 1993, Chocolate Silver Burmese Cineole Eve was flown to Frankfurt and exhibited at Wuppertal. Unfortunately Tiki despised the young Burmese cat and Leonhardt got permission to sell Cineole Eve to a Burmese breeder. The breeder began a breeding programme with Cineole Eve and soon there was a silver stud cat. He was bred to Leonhardt’s Seal Ticked Tabby Burmese resulting in a Silver Burmese daughter, Mingo. Leonhardt now decided to to investigate the Singapura in order to understand how it had been created and why it was not called Seal Ticked Burmese, like those cats bred in New Zealand by Dr. Lomax.

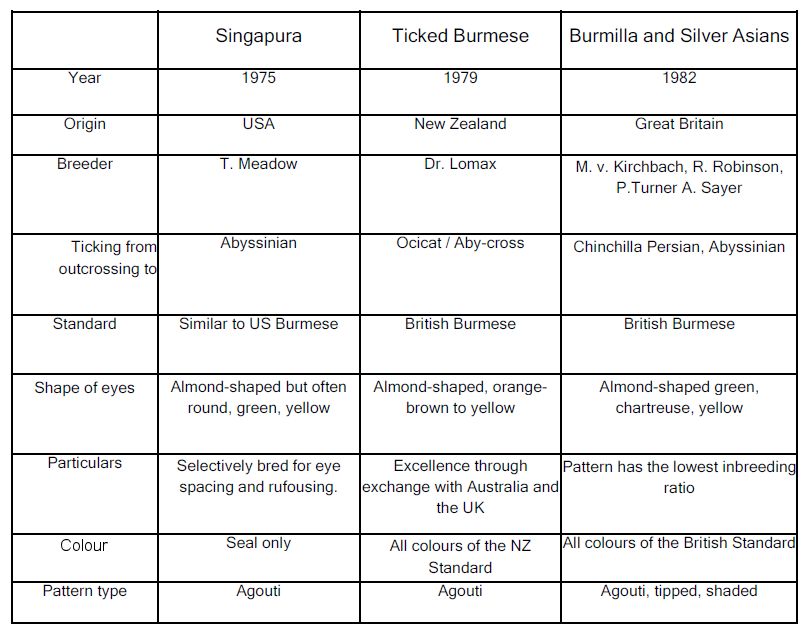

In the 1970s and early 1980s three different Seal Yicked Burmese arose with different names and slightly different standards. New Zealand had the Ticked Burmese (1979) originating which had used Ocicat / Aby crosses to introduce the ticking. Britain had the Burmilla and Asian Shorthairs (1982) from outcrossing to Chinchilla Longhairs and Abyssinians. The USA had only the Singapura (1975), found only in one colour and which Leonhardt suspected had used the Usual Abyssinian or “Wild Abyssinian” (ticked cats from Singapore). All conformed to their region’s Burmese standard for type.

Three Seal Ticked Tabby Burmese with Different Names and Origins. In the seventies and early eighties, it seemed to breeders in America, New Zealand and, last but not least, in Great Britain that it was time to add patterns to the Burmese. This was done in experimental breeding programmes approved and supervised by the governing bodies.

Since 1951, Leonhardt had been investigating the agouti pattern of both wild and domestic cats in East and South-East Asia, where she had spent some years. The the cats in and around Singapore, all of them Wild Abyssinians, [naturally occurring ticked tabbies] were well known to her, and she had published the results of her 50 years of research in "Edelkatze" in 2004 (reprinted in "Our Cats Annual" in the UK). It became clear that there was never a “Singapura cat” or a “Singapura neighbourhood”, not even in so-called pockets. When she had read Tommy Meadow’s first illustrated articles in the 1980s, she realized that only the Abyssinian/Wild Abyssinian could be responsible for the pattern, but it could not have produced the brighter coat colour or the head conformation. How could the breeder claim that such cats were found in Singapore, an area that Leonhardt had covered exhaustively from 1951 to 2006 in terms of cats, while Mrs. Meadow had been there for scarcely a year and “discovered” the Singapura. Leonhardt began to investigate.

Margaret Henderson, a well-known Dutch Burmese breeder of Cinnamon Burmese, reported that the American judge Vicky Markstein had classed her experimental brown-tipped Burmese stud, Kallistra Eustathes, as a Singapura. New Zealand Burmese breeder Jill Dugan had presented a brown-ticked tabby at the "National Show", where the South African judge Johan Lamprecht promptly classified it as Singapura, even though not a single Singapura was in the New Zealand at that time. In 1990, Silver Burmese breeder Terence D. Lomax said that the seal-brown ticked tabbies in his breeding programme were known as Singapura in the USA. Cat judges already realised that Singapuras were ticked Burmese and that appropriately coloured and marked Burmese could be transferred into the Singapura breed. At least a dozen European, and even some American, All-breed judges therefore proved that a cat could be a Singapura even if the mother was called silver Burmese or ticked Burmese. The rule that Singapura can only be bred to Singapura came from the time when the breed’s genetics was kept secret by its creator.

Leonhardt also looked into Meadow’s background to see what motive she might have for creating a new breed. The then CFF all-breed judge Tommy Brodie had been abandoned by her husband and had to raise 5 children unaided. Unable to afford her cats, to keep her Abyssinian and Burmese breeding lines alive she sent her cats out on loan to other breeders. Ten years later she met Harold “Hal” Meadow and the couple spent 7 months in Singapore because of Hal’s job. Once home, she had much work to do with her few specimens of the newly “discovered” breed. She publicised and promoted the cats so they could be registered and involved a number of breeders to get the numbers up so they could be recognised as a breed.

When the Singapura was presented at the first shows, the Abyssinian breeders wondered if it could be an Abyssinian because it bore such a resemblance in terms of markings. The Singapura could have gone through as an Abyssinian except for having brown tipped hairs instead of black tipped hairs. If this seems odd to European readers, please understand that American clubs were (and still are) much more restrictive on permitted colours than the European clubs. Oddly, nobody asked which cat breed had produced the brown colour. When quizzed, Meadow admitted that occasional solid colour and incorrectly coloured kittens were born and were excluded from further breeding along with their parents (which crried unwanted genes). This should have attracted more attention, but most breeders are too interested in their own breed unless, of course, the newcomer is going to compete against them. More plausible reasons for the Singapura’s colouring and conformation was presented through the diligent work of American geneticist D. H. Shaw and British geneticist Roy Robinson, but these were not available as mainstream works. Thus Meadow was able to launche her Singapura as a "natural breed" in the USA and worldwide.

For years, all Singapura breeding was controlled by Meadow because she owned all the stud cats. Breeders had complained about inbreeding defects, reduced fertility, very small litters, reduced viability and decreasing body size. Jerry Mayes, a Singapura breeder from Georgia, did not tell anyone of his plan to get Singapuras directly from Singapore to revitalise his breeding programme. He had never doubted Meadow’s Cinderella story. Despite a keen search and consultation with the head of the local animal shelter, Mayes could not even find even a single Singapura. He found only the Wild Abyssinians, and finding one of those with a straight tail was difficult enough! Although those cats did not exactly resemble his Singapuras back home, he took some back with him as outcrosses. Leonhardt considers that this corresponds to an outcross with Abyssians, that is, a hybrid.

Mayes hoped for advice and clarification from the President of the Singapore Cat Club, Mrs. Lucy Koh. Instead, she told him that she had not seen any Singapuras in Singapore apart from Mrs. Meadow's cats. Lucy Koh did not know of anyone who had ever seen a local cat that matched the Singapura. She recalled that Meadow had become a member of the Singapore Cat Club and had regitered her cats as brown Abyssinian. With Lucy Koh's help Mayes got an insight into Meadow's import and quarantine papers. He was astonished when he read that Meadow had imported six cats from the US into Singapore in 1974 and had taken them back to America seven months later. The breed details clearly indicated brown Abyssinian and Burmese. In his disappointment, Mayes turned to the reporter Sandra Davie from the high-profile English-speaking "Straits Times" newspaper. Davie conducted a recorded telephone interview with Tommy Meadow. After hearing about the disclosure of the import and export papers, Meadow finally admitted she had completely invented the whole story.

The street cats Mayes had seen in Singapore there were quintessentially different from those in America. He had seen no pattern except the ticked tabby, albeit broken up by white spots and in brown, cream, foxy red, and dark grey colours. The Singapuras were an American-bred colour and pattern variant of American Burmese. They could not be introduced as Burmese in the USA because American Burmese breeders resisted all efforts to allow any colour in the breed except for sable (seal). Those breeders had previously put up such a battle against new Burmese colours (blue, chocolate and lilac/lavender) that the cat fancy had been forced to call the new varieites “Malayan” in order to appease all parties. Meadow would have known that her cats needed a new name in order to be accepted, and needed to be a “natural breed” in order to keep the peace with Burmese and Aby breeders. It is easier to get a “natural breed” recognised in TICA than to go through many hoops when developing a breed from one already existed. The drain cat elevated to stardom added to their attraction. She also avoided using pre-existing colour descriptions: her cats were the colour of unbleached muslin with sepia tips to the ticked hair and the intervening light bands were the colour of old ivory. Those three colour names had not previously existed in cats.

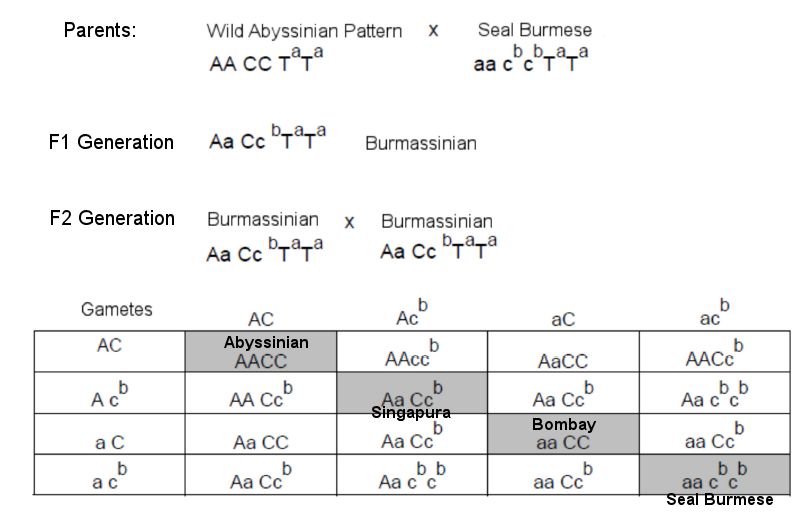

Sandra Davie, who knew the truth about the cats’ American origins, tried to prevent embarrassment to Singapore by preventing the Singapore Tourist Board’s major advertising campaign centered on “Kucinta” the Singapura cat. However the promotional items had already been printed and the campaign could not be stopped without causing financial loss. It also further reinforced the fiction of the cat's origins. However, the truth from Singapore had reached the USA where legal advocates and the CFA president had to calm breeders who found out they had been misled. The CFA were grateful that the Burmese breeders had not risen up again. Although the breed was no longer pitched as a "rare natural breed from Singapore" nothing was changed in the official breed records, and the Cinderella storytale still haunts cat books today. In France, F1 Burmese-Aby crosses were called Burmesessinier and had black hair tips. Mating F1 cats together resulted in the re-emergence of the parental breeds and the emergence two new breeds – the Singapura and the Bombay as well as 12 other combinations. Additionally, the Singapura's "trilling purr" is similar to that of the Abyssinian.

Singapura breeders knew that the breed had to be subjected to four test matings (a time-consuming and costly process) in order for it to breed true for brown. Siamese, Burmese and blue cats were experimentally mated with Singapuras, until all carriers of Siamese, Non-Agouti and Blue were identified and removed from breeding. All blue, blue-tinted, brown and ticked mink-pattern (Tonkinese pattern) kittens were sterilized and given away. Many breeders would not have had the time or finances to neuter and give away favourite cats and they did not want to lose the rare Singapura-patterned studs, regardless of recessive colour/pattern genes. The standard required eye colours between green and yellow. Blue is considered a defect. Nevertheless, a former German Singapura breeder imported breeding cats from America. He sold a young cat from his first litter, whose adult eye colour had not yet developed. When the buyer exhibited the animal, the judges desqualified it because it had aqua eyes. It was a rare Agouti patterned mink colour (Tonkinese colour). The American breeders were apparently unaware they had Siamese colourpoint genes, probably passed on because not all breeders performed test matings (or they had kept typy cats in spite of the recessive colourpoint gene).

In 1982, American Singapore breeders opted for lighter, warmer, rust-coloured tones, which required further test matings and further removal of breeding cats. The gene pool shrank. Rufism (rustiness) of the ears and nose distinguish today's Singapura from the Seal Ticked Tabby Burmese. When Meadow included “Cheetah lines,” in the standard (dark lines from the inner corner of the eye to the upper whiskers) it was just to make her Singapuras more interesting. These markings are standard in darker tabbies and are not exclusive to the Singapura. Meadow also wanted the Singapura to be free of any striping e.g. on the limbs or tail.

The Singapura showed many signs of inbreeding depression including small litters, high kitten mortality and reduced size. While a breeder might not understand “genetic uniformity” it is quickly apparent that the kittens all look identical with the normal small variations found in genetically more diverse breeds. Since most clubs prohibited outcrossing to other breeds, breeders were often left to their own discretionor had to join an an independent club which would help them with an experimental breeding program. This did not seem to worry the late TICA Regional Director Tord Svenson, who crossed his Singapuras with a British Burmilla stud to improve genetic health. This also introduced the recessive long-hair gene into the mix, albeit at low frequency.

Small size and low birth rates are related. Small-sized Singapura females produce the normal number of eggs at each ovulation, but usually cannot carry all kittens to term because there is simply no room in such a small body. A numbe of foetuses are resorbed early on, leaving only mummified remains (if anything) to be expelled when the cat gives birth. We know it is not the stud’s fault because he is producing plenty of healthy sperm and occasionally a large litter (on a larger or outcross female) is born. Those resorbed kittens might well have been show champions. The fact that the Singapura has been registered in the Guinness Book of Records as the smallest breed cat in the world has done it a disservice. Many articles emphasize its diminutive size. Meadow described her creation as small and gave its weight as between 2.25 kg 95 lb) and 2.75 kg (6 lb), corresponding to the weight of Burmese. A Singapura weighing only 1.5 kg (3.3 lb) can only result from selective breeding or inbreeding depression. If breeders of other breeds notice that their cats become smaller than normal,they would consider it time to outcross to an unrelated line. This is impossible in the Singapura because of the small gene pool. Only crossing to another type, then breeding back towards the Singapura standard, can improve genetic diversity.

By 1980, the American Burmese had morphed from the moderate type to the pug-headed contemporary type. Many carried the gene(s) for a lethal head malformation and some also had open abdomens. Deformed kittens that survived had to be destroyed by vets, but the disapproval of the veterinary field meant that some breeders destroyed the kittens at home, hiding their existence. The Singapura, genetically identical to the American Burmese apart from its colour, also risked such defects. The first Singapura to arrive in Britain was a pregnant female that gave birth in quarantine. The GCCF ordered test matings with the English Burmese and also prohibited the registration of Amerian Burmese because of the lethal head defect.

In 2001, Leonhardt’s seal silver Burmese female Mingo was covered by the Singapura stud Opium. The litter contained three Singapura girls and two silver Burmese. Just like the Singapura, the Silver Burmese needed a new name – Asian (including the Burmilla) - in order to gain acceptance because of opposition from Burmese breeders who wanted their cats to remain separate from the silvers. Apart from colour, they conform to the Burmese standard. A variety of ticking colours arose naturally and were emphatically not hybrids (Cineole Eve had been a Chocolate Silver Burmese).

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING