RUSSIAN & UKRAINIAN CAT BREEDS

In the nineteenth century, two Russian breeds played an important role in the cat fancy. The Russian Longhair was one of the ancestors of the modern Persian, while the Russian Blue was one of the early recognised breeds. For much of the twentieth century, the Iron Curtain meant that little was known about the aboriginal cat breeds that existed in the former Soviet Union. That changed in the 1990s with Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of "perestroika" (restructuring) and "glasnost" (openness). The growth of the internet and usenet, particularly in the mid 1990s, played an instrumental role when an article containing short descriptions of a number of Russian breeds was circulated. This piqued the interest of Western cat fanciers so that all of the breeds described, excepting the Ussuri, are now bred and shown outside of their home country. This article covers the Russian and Ukrainian breeds.

ALTAI AND TOPAZ

See Blue-Eyed Breeds for details of these Russian/Ukrainian blue-eyed cat breeds.

CARACAT (KARAKET)

See Serval and Caracal Hybrids for details of Russian Caracat breed.

DON SPHYNX (DONSKOY)

The hairless Donskoy, also known as Don Sphynx, was born in 1987 when cat breeder Elena Kovaleva rescued a hairless cat in Rostov-on-Don. The breed foundation cat was blue-cream tortoiseshell female rescue named Varvara. At first, it was believed Varvara was hairless due to illness or a skin condition, but as time went on Varvara was found to healthy, albeit hairless. Around 1989, she was bred to a neighbouring tomcat and produced several hairless kittens, demonstrating the mutation to be a dominant gene. The progeny were bred to European Shorthairs and Domestic Shorthairs and became the foundation cats of the Donskoy Sphynx breed. It seems other hairless kittens were born in the area, one of which was rescued and used in breeding.

Unlike the recessive hairless mutation which created the Sphynx breed, the Russian hairless mutation is a dominant "hair loss" gene, meaning that only one parent needs to have the gene for hairless kittens to be produced. Some kittens born from mating a Donskoy to a fully furred outcross can have a residual curly or fine coat at birth. This fur is shed their coats between 2 months and 2 years of age. Other kittens from Donskoy-to-furred matings retain a curly coat throughout their life and are known as "brush" coated. When this first generation are bred among themselves, kittens that are hairless at birth appear in litters.

The Donskoy was recognised by World Cat Federation (WCF) in 1997, and by The International Cat Association (TICA) in 2005. Not all registries recognise the breed and there are some concerns that cats with 2 copies of the dominant hairlessness gene could suffer feline ectodermal dysplasia which can cause poor dentition and affect the ability to lactate (milk glands are modified sweat glands).

It is a solid, medium-size cat with a short wedge-shaped head with prominent cheekbones; large, upright ears; almond-shaped-eyes; and wrinkles on the face, forehead, and jowls resulting in an old man expression. Some Donskoy have whiskers, others don't. Young cats may have curly whiskers, short fur on the muzzle, cheeks and at the base of the ears. The Donskoy may grow a fine coat of fur in the winter.

It is recognized in all colours. Because hairlessness in these breeds is a dominant trait, expression of the hairlessness trait can varies. Cats with one copy of the gene may have a different feel to their skin from cats with two copies of the gene. Variations include complete hairlessness on the body, resulting in a rubbery feel to the skin that resembles vinyl; a soft, velour coat of short hairs that feels like crushed velvet; and a curly, coarse, brush-like coat. TICA classify the different coats as: Rubber Bald/Ultra Bald (born bald), Flocked/Chamois, Velour (crushed velvet texture) and Brush (coarse and curly). Straight coated kittens also occur due to recessive genes carried in these breeds. The amount of hair may change with the seasons, becoming more dense in the cooler months.

FLEECY CLOUD

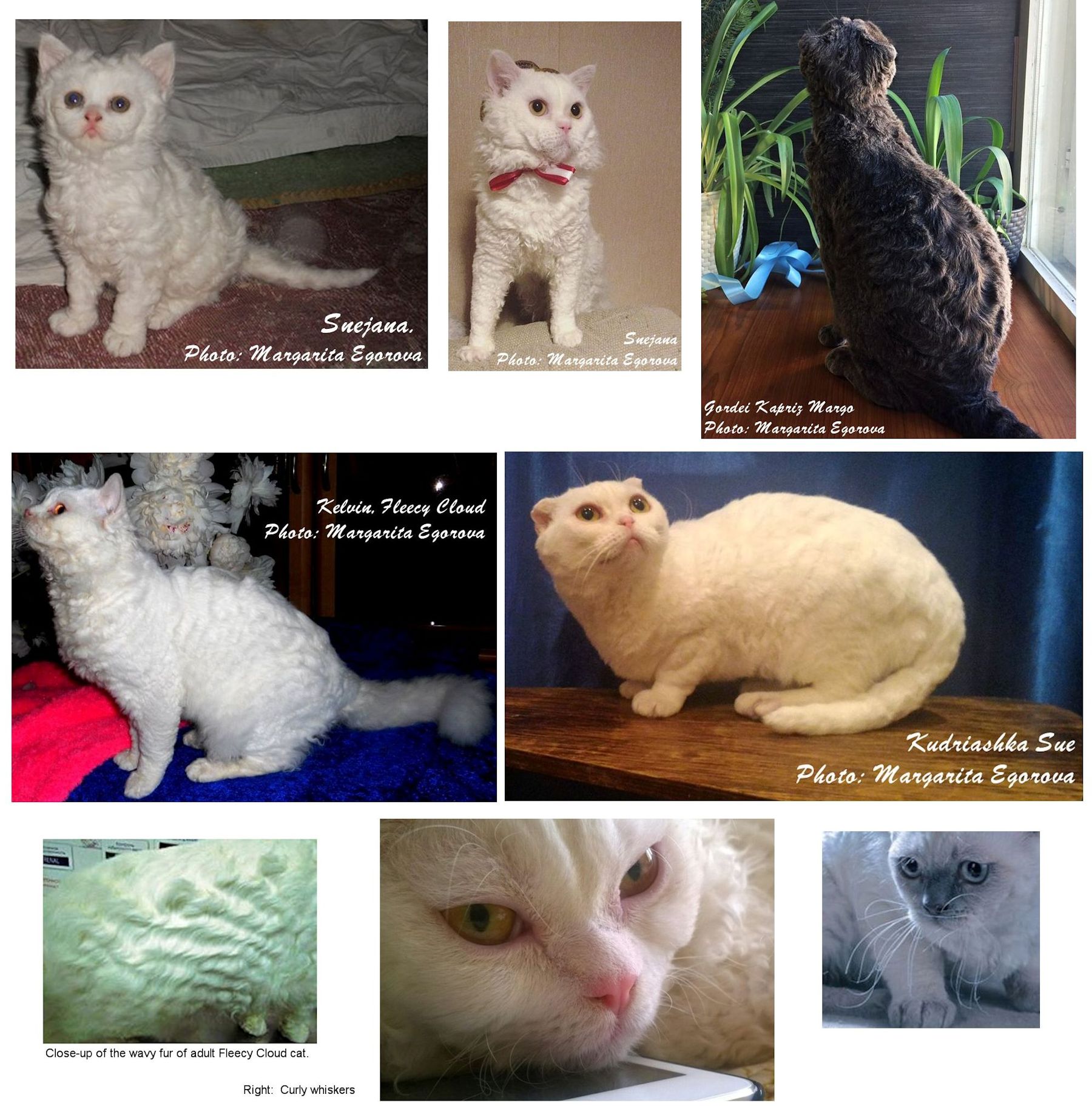

Firstly, this mutation occurred naturally in Russian breeding lines and not from a deliberate attempt to create rex-coated Scottish Folds. Several known rex mutations have been ruled out so this may be a spontaneous mutation. The fur of the Russian-bred Fleecy Cloud breed is distinguished by its large, elastic curls that are soft to the touch. The coat looks impressive and the curls never droop, but look more like fleecy clouds, hence the name. The ancestors of this breed were purebred Scottish cats who produced some curly-coated cats. Today breeders are committed to fixing this gene and improving the breed.

In January 2014, a strange curly-haired kitten was born in the litter of pure-bred Scottish cats Daryl White and her son, Nestor Petrovich, owned by breeder Margarita Egorova. The curly kitten was named Snejana. Margarita Egorova was interested to see how the kitten would develop and kept it for study. When Snejana grew up, her fur formed large waves. Margarita also wanted to know if this was a one-off or whether the same mating would produce more curly kittens. In their next mating, Nestor and Daryl produced two curly-coated white kittens, named Kelvin and Kudriashka Sue, a white male Scottish Fold (went to a pet home) and a lilac female Scottish Straight. The lilac female was assumed to be a carrier of the curly gene and was mated to an unrelated bicolor Scottish cat who was also was a gene carrier. This paring produced 4 kittens, one of which was curly.

The mating was inbred, so it was assumed that a recessive rex mutation was being expressed. This was confirmed by the fact that both cats had produced litters with other partners without producing rex-coated kittens. However, curly-haired kittens were also born in a litter of the same cat, Nestor Petrovich, and cats of unknown origin that were phenotypically Scottish fold. Curly-coated kittens had also been born repeatedly in Scottish Fold litters (in Russia), but no-one was working to identify the rex gene involved. The recessive Urals Rex gene was ruled out because that native Russian breed has not being crossed with other cats.

Because curly kittens were born to straight-haired parents on both occasions, it was clear that this was a recessive gene. The breeder had two assumptions about the genetic basis of these kittens' curly hair. The first was that it came from the Bohemia Rex (aka Czech Curly Cat), a rex-coated Persian-type cat bred in the mid-1980s in Czechoslovakia. This breed had the Cornish Rex gene, and though the breed was lost, the Cornish Rex gene persisted in the Persian gene pool and found its way into the gene pools of British Shorthairs and Scottish Folds when Persian blood was used to improve conformation. Being recessive, it was periodically expressed when carriers were mated together. At the start of the 21st century, curly-coated Persians quite often appeared in Belarus, Poland, and Moscow, but breeders had no interest in them, and the trait became rare in the Persian breed. On the other hand, it was not so unusual for rex-coated Scottish Folds to appear in Russia. Because Persians were used to give the Scottish Folds more rounded heads and a shorter-nosed, sweeter expression, and create a longhaired version, it was assumed that the Cornish Rex gene had been introduced at this time. However, DNA testing has ruled out the Cornish Rex gene.

The second theory was that the rexed Scottish Folds were due to the Devon Rex gene via the Poodlecat (Pudelkatze). In the 1980s, German breeder Rosemary Wolf developed a new and unusual cat by crossing a number of breeds together. Early on she used the Somali, Maine Coon, Norwegian Forest Cat and Chartreux. Later crossed the Devon Rex and Scottish Fold creating the first Poodlecats, with folded ears and rexed coats, in 1994. Long years of breeding and careful selection led to partial recognition of the experimental breed by FIFe, but lack of recognition by other major registries meant the breed stayed rare and is now presumed extinct. The possibility of the Devon Rex gene entering the Scottish Fold gene pool could not be ruled out without testing. DNA testing of Fleecy Cloud cats ruled out the Devon Rex gene.

DNA from the rex-coated kittens was tested at the Veterinary Genetics Laboratory School of Veterinary Medicine, Davis, California, ruling out the Cornish and Devon rex genes. Selkirk Rex and LaPerm were ruled out because they are dominant mutations. The Russian cats were therefore a unique mutation. The Fleecy Cloud breed is therefore considered unique by expert felinologist, and president of the "FELIS" cat club Nina Vladimirovna Ekimova, who conducted a review of the cats. Together with Nina Ekimova, Margarita decided to develop the cats as a new breed called FLEECY CLOUD. The name reflects the fur type. Nina visited many exhibitions throughout the country and knew that curly kittens were sometimes born in Scottish Fold litters; she had seen such kittens at exhibitions. The occurrence of rex-coated Scottish Folds was also mentioned in specialist felinological literature. A similar mutation had appeared in St. Petersburg (Russia) and also in Kazakhstan, where breeders tried to develop a curly-coated Fold.

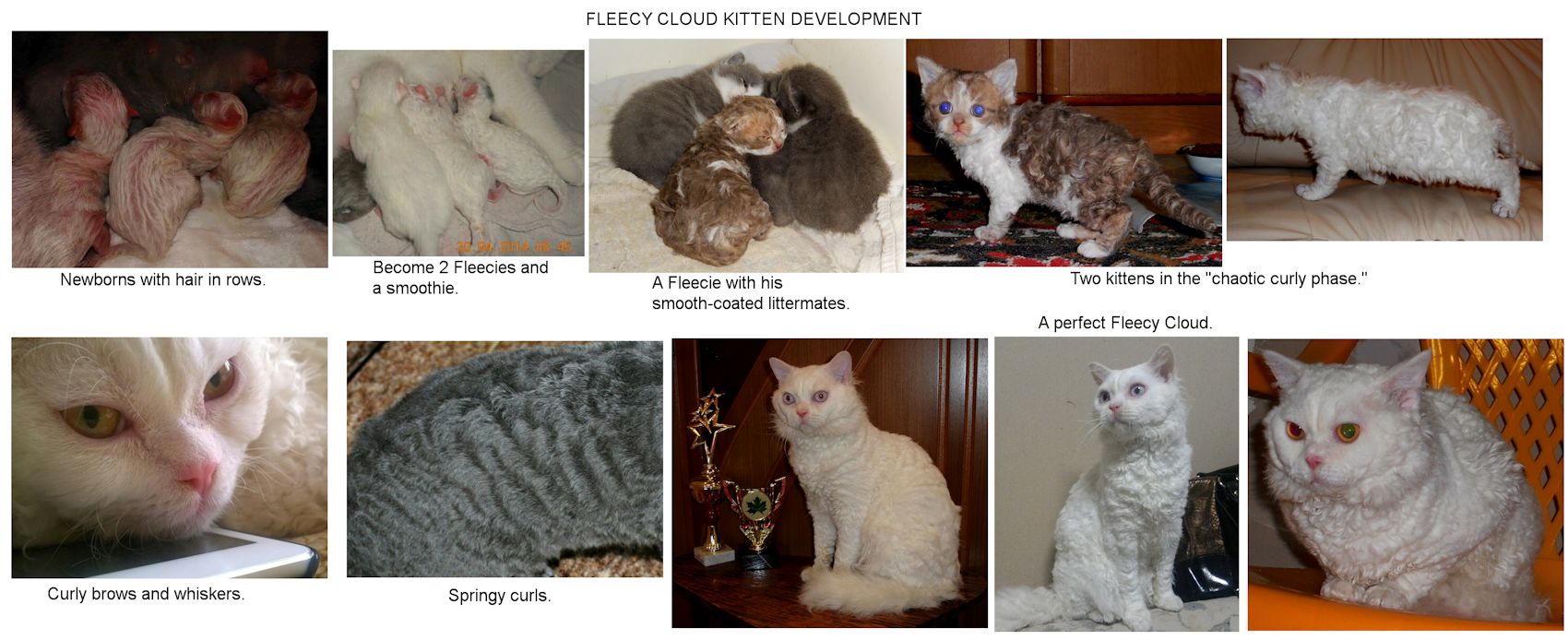

Fleecy Clouds look very different from Scottish Folds. The kittens' muzzles are not so round, and they have broad cheekbones and have almond-shaped eyes set obliquely. These features become more pronounced with age. Breeders are working to preserve and enhance the difference between the Fleecy Cloud and the other recognised rex-furred breeds. The fur forms large open curls and lies in dense waves. Both awn and down hairs are present and have the same curliness. The texture is springy and not too soft and when stroked the curl can be distinctly felt as well as seen. The fur is shiny and slick-textured, but is not oily, and does not become tangled or droopy. The curls do not straighten with age and curls that are disorderly in kittens become regular as they mature, forming neat rows in adulthood with no sparse or bald areas. Kittens are born with very twisted whiskers which straighten into waves as they mature.

Fleecy Cloud cats have very friendly and non-aggressive temperaments and love to communicate with people. This, along with their unique features, makes them a valuable addition to the showbench and the pet home.

Independently of Margarita's breeding work, in the Perm region of Russia, Lana Nasurdinova began to develop curly coated cats from a cat bought in St. Petersburg. When the two breeders met, they realised that they had the same goal and decided to work together. Margarita's breeding programme was further advanced and had a larger genetic pool so the breed development programme was based on this. Margarita gave Lana the right to use the registered name and breed standard and the two breeders exchanged cats with Aleecy joining Margarita's cattery.

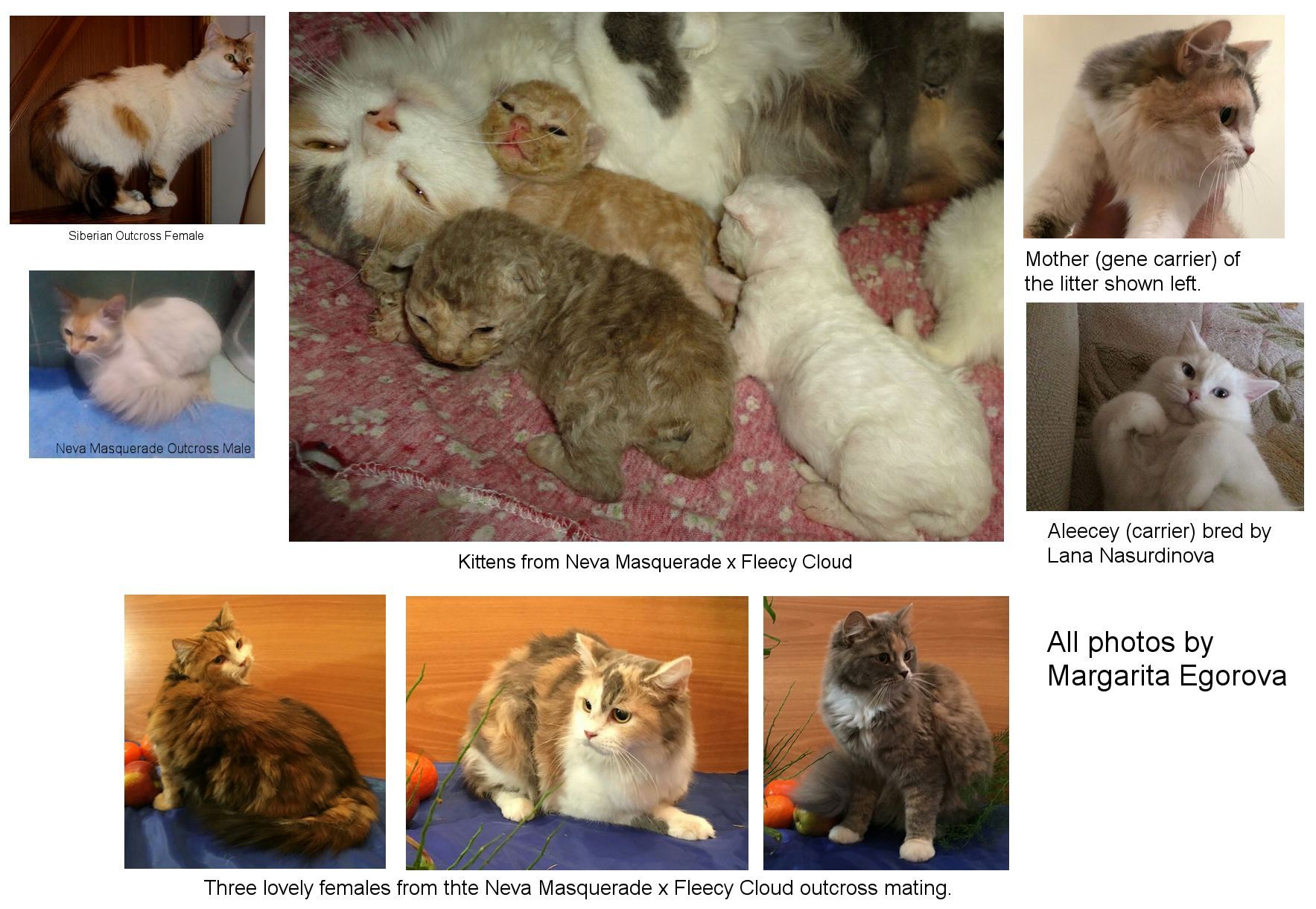

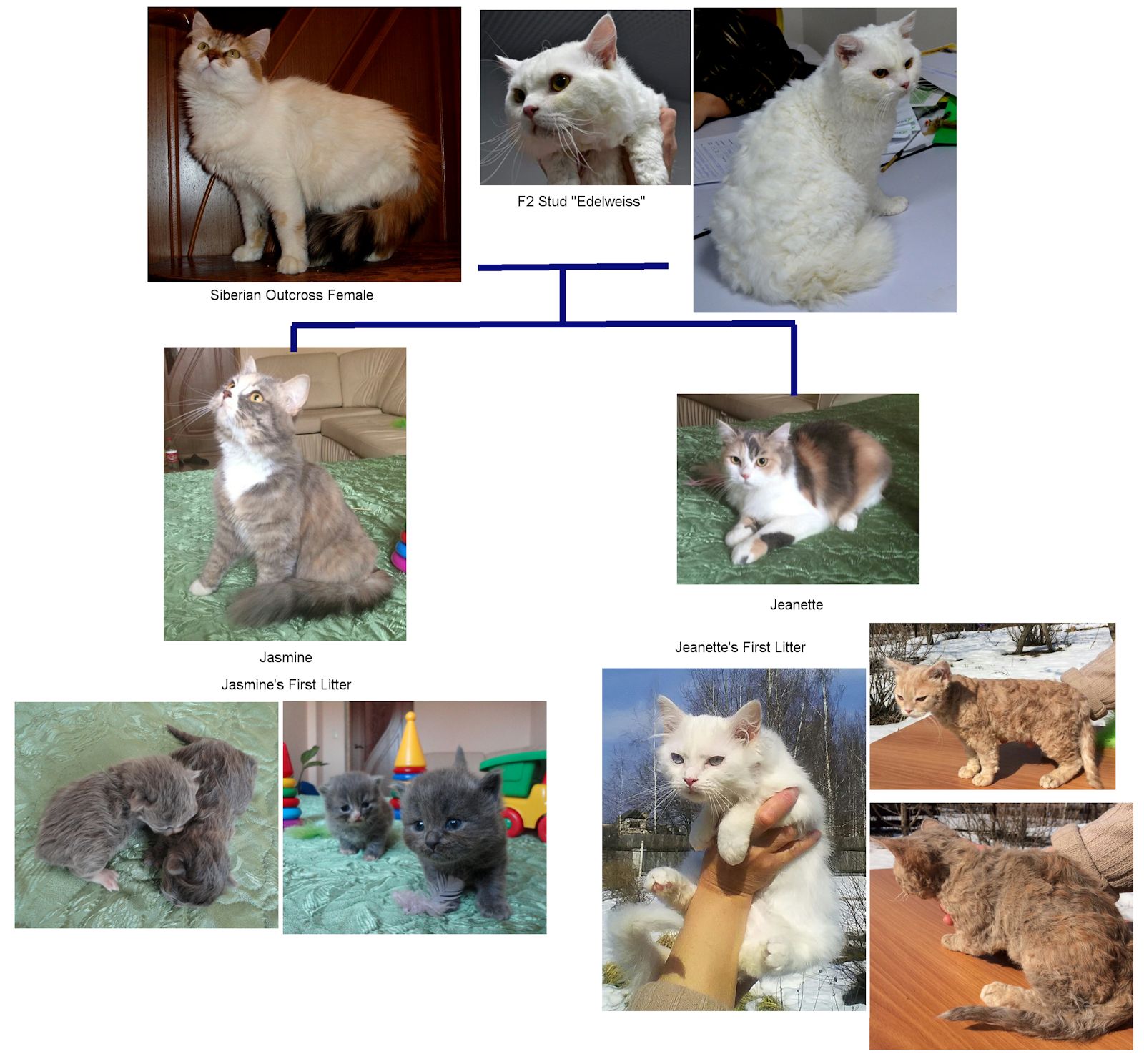

To expand the gene pool, improve the cats' type and ensure the breed was healthy, Fleecy Clouds were outcrossed to the Siberian and Neva Masquerade (the colourpoint form of the Siberian). This produced 3 lovely females, one of whom gave birth to an F3 litter containing some new colours. At present, because the cats are few in number, fold-eared curly-coated cats are still used in the breeding programme. In future this will be prohibited. The breed standard calls for straight ears and permits any colour coat and eyes. Both longhaired and short-haired varieties are allowed.

Two litters of kittens were born one after another to Jeanette and Jasmine, daughters of the Siberian outcross cat Anfisa. Anfisa has founded a new line of bicolour curly cats. Jeanette's first litter with Edelweiss produced 2 curly kittens - a creamy male and a lilac female, and a smooth-coated blue-eyed white variant. Jasmine's litter with Edelweiss produced 2 smooth-coated females, a blue and a blue-and-white bicolour. When deciding on breeding pairs, all the best qualities of both parents were carefully taken into account. Inbreeding was done with Edelweiss because in 2018 he was considered the best Fleecy Cloud and closest to the breed standard. He is father and grandfather to the kittens.

Fleecy Cloud kittens are born with very short hair and appear smaller than their smooth-haired littermates. Their hair lies in rows along the back and across the legs. Then the hair grows quickly and becomes chaotic curls giving them an amusing appearance. In adult cats, this chaotic fleece turns into large elastic waves. The ruff is less curled and thee are very small waves on the paws. In newborns, the kittens' whiskers and eyebrows are finely twisted, but with age they straighten and will be slightly curly. Although they look smaller, curly kittens are usually heavier than their smooth-haired brothers and sisters. Their muscles are dense and they have heavy boning. They keep these features into adulthood. Kittens born from Scottish cats carrying the curly gene x Fleecy Cloud mates have very robust hindquarters. The outcross to Siberian cats changed the appearance of the kittens born to Jeannette and Jasmine. They are more harmonious and proportional. Apart from this structural change, the inherent Fleecy Cloud breed characteristics remain unchanged.

The Fleecy Cloud curly gene is recessive and to get curly kittens both parents must carry the gene. When outcrossing Fleecy Clouds to ordinary cats, all kittens will be smooth-haired, but they are carriers of the curly gene and on their pedigrees they are FLEECY CLOUD Var" and are valuable for breeding. When one parent is curly and the other is a Variant some of the kittens are born curly, and some are born smooth-coated and are carriers of the gene (the other is straight. But all kittens with smooth hair will carry the gene (also FLEECY CLOUD Var"). When two Variants are bred together, the litter is a mix of curly kittens, smooth-caoted carriers and smooth-coated non-carriers. Breeders question how to distinguish the carriers from the non-carriers. They hope the carriers will have some distinguishing feature, but it is too early to say. For example the whiskers and eyebrows of Jasmine's kittens were straight, but their fur was wavy. When they grew up their hair straightened and became smooth, but nevertheless they showed early signs of curly hair appeared. This may be a marker indicating they carry the Fleecy Cloud gene

The cats were introduced in the class of unrecognized breeds at the WCF and FARUS show where judges and other experts showed great interest, giving their advice on working with a new breed and wishing the breeders every success. Conditions for the initial recognition of the breed came from Andreas M bius in person. To recognize the new breed in WCF it is necessary to get 4 generations of animals in which all 4 generations in the pedigree will be filled with the new breed with no outcrosses. That is sent to Germany with at least 2 photos of the best representatives of the breed, one face/front view and one in profile. The breeder(s) must also show at lest 30 cats with this 4 generations pedigree in the Russian FARUS system so they can be reviewed by judges.

KARELIAN BOBTAIL

The Karelian Bobtail originated as a natural breed in the Republic of Karelia in the North-West of Russia (from St. Petersburg to Petrozavodsk) in the Lake Ladoga region. Unlike the dominant bobtail trait of the Kurilian, the Karelian's bobtail is a recessive gene. This means the trait breeds true. As a natural breed, the Karelian Bobtail is robust and healthy. It occurs in both shorthair and longhair varieties and has a silky, glossy coat. It is a medium-sized cat with a pom-pom tail. These are elegant, svelte cats; the body is neither cobby nor elongated. Its hind legs are longer than the forelegs. Its distinctive feature is the tail which consists of one or more kinks and/or curves in any direction. The base of the tail is flexible, but the kinks may be either stiff or flexible. The visible length of tail (without fur) is 4 - 13 cm. The fur on the tail forms a pom-pom.

The aboriginal cats were noticed in the 1980s and recognised by the WCF almost simultaneously with other Russian breeds. The short tails were not the only distinguishing feature: they have a special voice and are immediately recognisable by their bird-like chirping. The voice is not included into the standard of course but that was how these feral cats attracted attention. They are in general smaller than the Kurilians and have a head closer to Norwegians in shape. However, interest for the breed was only local unlike the Kurilian and the breed almost died out after the local catteries stopped functioning. About two decades ago new aboriginal cats were found (which means that the feral population existed regardless of breeding) and taken into the breeding programme. There are now several catteries, not only in St.Petersburg, so breeders are hopeful that the breed has a bright future. The tail mutation is being researched.

Karelians are bred in all colours and patterns, with or without white. Colours that are not permitted (in either solids or patterns) are chocolate, cinnamon, lilac and fawn. Colourpoints (Siamese, Burmese or mink patterns) are not permitted.

KURILIAN BOBTAIL (CURILSK)

The Kurilian Bobtail originated on the Kuril Islands, claimed by both Russia and Japan, as well as Sakhalin Island and the Kamchatka peninsula of Russia (the 56 Kurilian volcanic islands extend 700 miles from the easternmost point of Russia to the tip of Japan's Hokkaido Island). It has existed in isolation for over 100 years. There are accounts of short-tailed cats being brought home from the islands by the members of the military or scientists in the middle of the 20th century, at a time when Russia had no cat clubs or breed registries. However, Their rodent-hunting skills made them popular pets. The breed is also called the Kuril Islands Bobtail, Kuril Bobtail and Curilsk Bobtail.

In the wild state, it is an excellent fisherman and hunter, and domestic Kurilians enjoy playing in water. People living in Kunashir report that bears will run away from Kurilian cats. Kurilian Bobtails are intelligent and independent, and though wild-looking and good hunters in their wild habitat, they are very sociable and gentle cats in the home. Foundation cats taken from the semi-feral state are said to be easily tamed. Their personality is often described as trusting and dog-like. They also tend to be non-vocal except for musical trills. In the wild, Kurilian Bobtails are sociable and often form family groups.

Short- or semi-long-haired, it is a medium to large cat with a semi-cobby body type and a short, fluffy tail. The back is slightly arched with hind legs longer than the front. It is a muscular cat and males can reach 15 pounds, while females tend to be between 8 and 11 pounds. In the feral state, they tend to be smaller. The most distinctive feature of the Kurilian is its "pom-pom" style kinked, short, fluffy tail. The tail contains between 2 and 10 vertebrae and has one or more kinks or curves in any direction. The visible length of the tail (without the fur) is between 3 and 8 cm.

Shorthair Kurilians have a short, dense coat. Semi-longhair Kurilians have long coats with a dense undercoat and noticeable ruff, frill, britches and ear-furnishings. They are found in solid, tabby and tortie (with or without white markings) in all colours except chocolate, cinnamon, fawn, lilac. The range of patterns includes silver/golden tabbies, shaded silver/golden and silver/golden smokes. Colourpoints are not permitted. The most common colours are red, grey (blue) and mackerel pattern. Some Kurilian Bobtails exhibit silver highlights to their fur.

Kurilian Bobtail litters usually contain only 2 or 3 kittens, which may be a result of early inbreeding on the islands, or a side-effect of the gene mutation. In the feral state they breed only once per year, in common with European wildcats. Kurilian males may spend as much time tending to the kittens as their mother does, perhaps a wild trait that ensured the kittens' survival.

The first Kurilian breeders were Lilia Ivanova (Kunashir) and Tatiana Botcharova (Renessence). These two breeders were competitors and did not co-operate with each other. Ivanova's small breeding stock resulted in severe inbreeding and an accompanying loss of vitality in her cattery. However, cats from her bloodlines became the foundation stock for many catteries in Russia today. Kunashir lines are longhaired only and weigh 4 - 5 kgs. The cats have wide heads which makes the body look small. The body is short, often with a curved back. Meanwhile Botcharova began with more breeding stock, all originating from the islands. Renessence lines were mostly shorthair and had a more flexible skeleton and longer body than the Kunashir cats. Renessence bloodlines concentrated on the van-pattern and on dilute colours.

Nowadays, more bloodlines have been created using more foundation cats and the Kurilian Bobtail is a popular breed in Russia. Kurilians are also bred in Germany and Canada, and a stud cat was exported to the USA. The Kurilian Bobtail was recognized by the WCF in 1995. Recognition by other registries has been hampered because there are few 5th generation pedigree Kurilian Bobtails. Cat fancy Kurilians are not outcrossed to other breeds as there are existing foundation cats on the Kuril Islands.

The first time the Kurilian Bobtail was exhibited in 1990, many believed it was a robust variety of Japanese Bobtail. However, it originated on the opposite side of Eurasia and is considered an aboriginal Russian breed resulting from a spontaneous mutation that was perpetuated due to geographical isolation. It may be the original source of the bobtailed trait in the Japanese Bobtail breed (which was developed in the USA) The Kurilian's bobbed tail is due to an incomplete dominant gene, while the similarly named Karelian's bobbed tail is a recessive gene. While the Kurilian shares physical characteristics with the Siberian cat, the Karelian has similarities with the Norwegian Forest Cat. The Kurilian Bobtail gained Championship status with TICA in 2012.

MEKONG BOBTAIL (Thai Bobtail, Thai Short-tailed, Thaibob)

This is a Russian breed with a Vietnamese name. The Mekong Bobtail is named after the Mekong River bordering Thailand. Colourpoint bobtails occur naturally in Thai (traditional style Siamese) non-pedigree cats in Russia and in the southeast of Asia, Iran, Iraq, China, Mongolia, Laos, Burma and Vietnam. In the late 19th century Nicholas II, Tsar of Russia received a number of Royal cats from the King of Siam Chulalongkorn, Rama V. Many of these had short, kinked tails. Along with later imports, including cats from Vietnam, these were the foundation cats for the Mekong Bobtail. It is not outcrossed with any other cats.

In many respects it differs from the Thai (which resembles the older style Siamese) and may not be outcrossed to the Thai. Unlike modern Siamese it is rectangular rather than tubular. It is medium sized, well-muscled, but elegant with a short curved tail. The head is a slightly rounded wedge like that of the old style of Siamese. The eyes must be blue. All colourpoints are permitted, but must not have any white spotting. The fur is short, glossy and close-lying, is thin but not silky. There is a noticeable undercoat.

The distinctive feature is the tail: it should be no longer than one quarter of the body length and should be flexible despite having one or more kinks or curves. Shorter tails are preferable, but should not be less than 3 cm long. Its tail is short with varying combinations of kinks or curves. It must have at least 3 vertebrae. Long-tailed cats are not eligible for exhibition.

Between 1997 and 2004, it was known as the Thai Bobtail. It was renamed Mekong Bobtail to avoid confusion with the already recognised Thai. By 2012 there were around 1,500 Mekong Bobtail cats registered with cat clubs in Poland, the Czech Republic, Russia, Belorussia, Latvia and Germany.

PETERBALD

The Peterbald is a descendent of the Donskoy and shares the dominant hairless mutation. Some Donskoy cats were mated to Oriental/Siamese in St. Petersburg and Moscow in 1993, resulting in an oriental-type hairless cat. The first Peterbalds were born in January of 1994. Their sire was a Donskoy with light bone structure, Afinogen Myth, and an Oriental Shorthair female named Radma von Jagerhov. The resulting four kittens were the founders of the breed. Afinogen Myth was also mated to Russian Blue females, some offspring being used in the Donskoy breeding program and others becoming foundation Peterbalds. At the time of this article, it may still be outcrossed to Oriental Shorthairs.

While the Donskoy is a solid, medium-size cat with a short wedge-shaped head, the Peterbald was developed in the Oriental style, with long, fine-boned legs, a long neck, and a long, muscular body. The ears are large and flared out from the wedge-shaped head with a blunted muzzle. Peterbalds may grow a fine coat of fur in the winter.

It is recognized in all colours. Because hairlessness in these breeds is a dominant trait, expression of the hairlessness trait can varies. Cats with one copy of the gene may have a different feel to their skin from cats with two copies of the gene. Variations include complete hairlessness on the body, resulting in a rubbery feel to the skin that resembles vinyl; a soft, velour coat of short hairs that feels like crushed velvet; and a curly, coarse, brush-like coat. TICA classify the different coats as: Rubber Bald/Ultra Bald (born bald), Flocked/Chamois, Velour (crushed velvet texture) and Brush (coarse and curly). Straight coated kittens also occur due to recessive genes carried in these breeds. The amount of hair may change with the seasons, becoming more dense in the cooler months.

In 1996, the breed was recognised by the Russian Selectional Feline Federation (SFF). TICA recognised it in 1997. The World Cat Federation (WCF) recognised the Peterbald in 2003. Hairless and brush-coated Peterbalds have championship status in TICA.

As with its parent breed, the Donskoy, there are some concerns that cats with 2 copies of the dominant hairlessness gene could suffer feline ectodermal dysplasia which can cause poor dentition and affect the ability to lactate (milk glands are modified sweat glands).

RUSSIAN BLUE (and RUSSIAN SHORTHAIR GROUP)

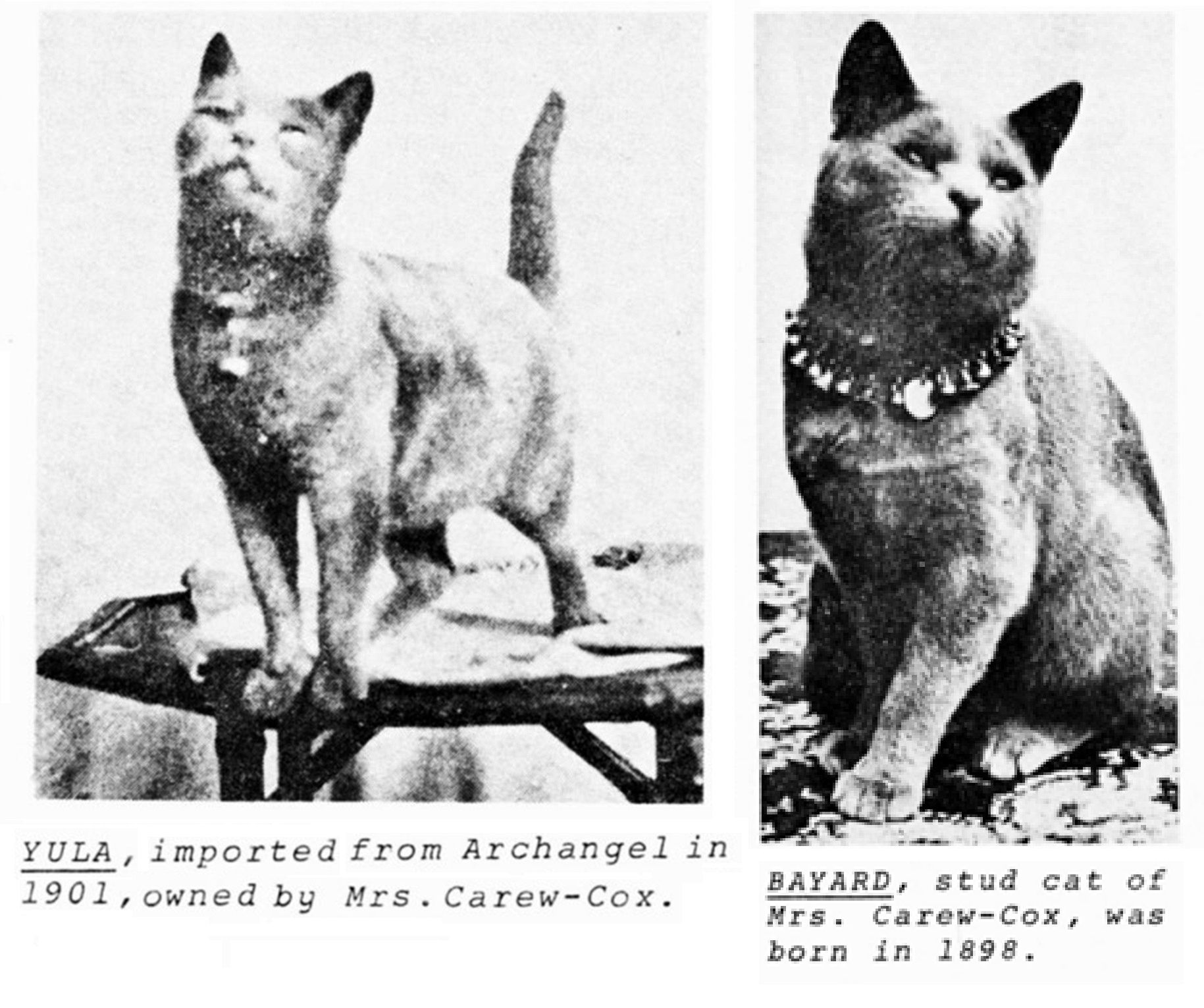

The Russian Blue was one of the early fancy breeds. It is believed that sailors brought blue-grey cats to England from Archangel in the 1860s, hence they were first exhibited in 1875 at the Crystal Palace as the Archangel Cat . Early cat fancy records show that foundation cats included imported solid blues, solid whites, lavender-blues, blue-and-whites, blue tabbies and solid blue "Siamese" (these last being the unrecognised Korat breed). These were bred to Black British Shorthairs in the hope of improving the fur colour and to Persians to improve the eye colour. Although claimed to be a naturally occurring breed and favoured pets of the Russian Tsars, the purebred Russian Blue (the exhibition breed) is a man-made breed developed in Britain using random-bred and pedigree cats. The Russian Blue was distinguished from British cats due to its more foreign appearance: larger ears and eyes, longer heads and legs and bright glossy fur. Up until 1912, they often competed in a general class for "Blue, With or Without White". The longer, leaner, leggier Russian Blue was judged against the British Blue standard, which it could not hope to meet. Dedicated Russian Blue breeders protested and in 1912 it was given its own class under the name "Foreign Blue".

One of the foremost early breeders was Mrs Constance Carew-Cox who had bred Russian Blues since 1890. While modern Russian Blues have green eyes, those of the late 19th Century were crossed with Persians to get the preferred deep orange eye colour. This ruined their conformation and resulted in longhaired "sports" in later generations. Imported Russian Blues were also very variable: some had long, lean pointed heads and large ears, while others had rounder heads, small ears and wide-set eyes. The coat was short, close, glossy and silvery but sometimes rather woolly due to the severity of their native climates and the colour varied from lavender-blue to darker shades. The best Russian Blues were considered to be those imported from Archangel. Some websites mention the blue tabbies (Canon Girdlestone's breed) owned by Mrs Carew-Cox, but they came from Norway, were in poor health and died without breeding.

Early Russian Blues were also confused with Korats. In 1896, a Blue Siamese was transferred from the Siamese class (on account of not being seal-pointed) into the "Russian or Any Other Blue Cat" class. Right from the start, Russian Whites and Russian Bicolours were imported. Registrations in 1898 and 1899 recorded an unnamed white Russian female imported by Mr Brooks; another white Russian registered as "Granny" and "Olga", a Russian Blue with a white spot. Carew-Cox imported a blue-and-white Russians called Kola. In the USA in 1900, Helen Winslow mentioned fine short-haired cats from Russia which were usually solid blue, though a cat fancier in Chicago owned a very handsome blue-and-white Russian. Ultimately the solid blues found favour and the other colours vanished in the western cat fancy until quite recently. When I've mentioned the early bicolour foundation cats, I've been attacked by American breeders who state those cats weren't Russian Blues, they were street cats! Dear breeders, your Russian Blue has its origin in those street cats, and those street cats weren't always solid blue!

During the Second World War, it was hard to maintain purebred lines in Britain. Numbers declined and it was impossible to transport cats over long distances to be mated. Some British breeders crossed their Russian Blues to the Siamese in order to preserve the conformation at the cost of introducing the recessive gene for colourpoints and the Siamese voice into the Russian Blue. Others crossed it to the British Blue to preserve the colour. The original conformation has since been restored through careful breeding, though some European lines still carry the gene for colourpoint. Except for their pattern, Russian Colourpoints are identical to the Russian Blue. Russian Blacks and Russian Whites appeared in the UK during the early 1960's when the registration policy allowed outcrosses to unregistered cats of unknown parentage to re-invigorate the breed. Scandinavian breeders crossed their Russian Blues to Siamese and to blue cats from Finland, preserving both the short coat and the green eyes. The breed had arrived in the USA in the early 1900s, but serious breeding did not begin until after the Second World War. American breeders used stock from Scandinavia and Britain and worked to eliminate any Siamese traits. As a result, the American Russian Blue is not identical to Russian Blues in Britain, Europe and Australasia.

In 1967, the following appeared in the CFA yearbook (USA) regarding the Russian Blue, and especially regarding its various origin stories: Is it logical to assume that all the blue short-hairs could have come from one common stock? That, swallowing our pride as "Russian Blue people" or as "Korat people" or as "British Blue people," all of these lovely cats are, in fact, from one and the same progenitor? I think it smacks of the real truth. But what difference does it make? Looking beyond the little trivialities, perhaps you'll find that really it makes no difference at all. I propose a moratorium on all origination stories of the Russian Blue. We, as dedicated advocates of this fascinating breed of cat, have far too much work to do on the current animals to concern ourselves with the cobwebs of the past. Breed the cats with the most distant out-crosses you can find. Repeat studs with un-related queens. See if you don't find that a true natural type will emerge and, more importantly, establish itself in your line. This is what we've done with ours. Certainly there will be those who disagree, and probably some violently, with us. But our breeding experiences suggest strongly to us that the recently accepted standard for the breed most closely approximates what this cat should be."

From the short-lived "Cats" bi-monthly magazine, the May/June 1971 issue had this letter about black and white cats of Russian type. "With reference to Mrs. Dagmar Thies' article in "Cats" last issue [May/June 1971] about a New Colour-type of Foreign Shorthair [EBONY. A New Colour-type of the Foreign Shorthair. by Dagmar Thies], I have been breeding a European Foreign type cat for 10 years now. Having been at school in Austria I grew to like the European type with dark green eyes and long bones and thick short fur. In England people have bred too much Longhaired Persian into their Shorthaired breeds and have lost the true green eye it is part yellowish green or orange now. Arctic Chumui was a Foreign White Cat not Siamese. She was found in the Pool of London by the R.S.P.C.A. and she was quite unlike any British Cat. She had long bones, large ears, slant eyes; beautiful thick soft lustrous shiny White fur and green eyes. When crossed with British tabbies she never threw a tabby kitten. She was a Self colour with no coat pattern. We crossed her with Russian Blues only, and I got jet black kittens and white kittens. The best Black Kitten at the National Arctic Hadese was a perfect specimen not a white hair anywhere shiny black with Russian Blue shape and green eyes. I have a Black Stud now Arctic Black Diamond (Almazzaria) in Russian. He is going to be shown this year. Last year he did very well so did his sister Arctic Ebony. Both had good reports from the judges at Kensington, Alexandra Palace, Midland, and National. Ebony is expecting kittens with my White Russian Kasuliapushchi he has had many cards and good reports. He is very Russian looking." - Frances MacLeod, 70 William Street, New Marston, Oxford.

Russian Whites and Russian Blacks were imported into the UK from the Netherlands in 1995. They came from a line originally developed by Frances McLeod in the 1960's as well as the Russian White line produced by the Joneses in Australia in the 1970's. Frances McLeod's cats came from a white female kitten (b. 1961), which came from a Russian boat. It was registered by the GCCF (UK) as Arctic Chumvi, an any other variety, foreign type. Because the 1960s Russian Blue gene pool was small, there were limited out-crossings to blue-point Siamese and domestic cats. Chumvi was bred to a Russian Blue stud and produced white, blue and black offspring. One of her white sons, Arctic Sumairki, was registered and was mated to a Russian Blue female who was registered by the GCCF in 1968 as a Russian White. McLeod bred and exhibited her Russian Blues, Whites and Blacks in the UK for many years before returning to Australia. Other breeders continued with her Russian White and Russian Black lines, and a black kitten, Arctic Lascatsya, (from a Russian Blue female and Russian White stud) founded the Lavengro line of Russian Blacks in 1984. In 1986 a pregnant Russian Black female, Jofran Emerald Eye, was exported to Belgium where she produced one blue and 2 black offspring. Some of Emerald's later kittens went Switzerland, Germany and the Netherlands to found Russian Black lines there.

In August 1974, Linda Kirsch, of the Russian Blue Association in the USA, wrote to geneticist Don Shaw via Cats Magazine saying Much controversy currently rages amongst our ranks, or should I say breed? A newcomer to the Russian Blue section of the Cat Fancy has reported the occurrence of a "White Russian" in her litter. She ask if it is a new form of hybrid. Many letters have come to me from long-time Russian breeders insisting they have never had a white Russian. Then too, I have received letters from people, owning Russians, who were told, Everyone gets Bluepoint Siamese in Russian Blue litters.' Who's to blame? Well the current trend is to pin it on the English lines of several generations past. Your comments on this subject are respected by cat fanciers at large. I would appreciate your thoughts on this timely topic [. . .] I feel that a professional opinion is essential to set the genetic facts clearly in the minds of our Breeders.

Shaw replied at length to her concerns (I have omitted some of the out-dated genetics notation). First to the English and the "Siamese'' problem. It is fairly certain that during' World War II the British did produce some rather interesting combinations in their cats. Under the circumstances we have no right to point a finger; they simply did what they felt many times to be necessary for the survival of their cats. However, this is not the only indication that Russian Blues were crossed with Siamese in the British Isles. Cats similar to what we now call Russian Blues were introduced into England at approximately the same time as the now famous pair of "Siamese" in the late 1800s. The original breeding pair of "Siamese" were reportedly Sealpoints. Bluepoints began to show-up in the area shortly thereafter. It has long been considered that they were the products of outcrosses to what we now call Russian Blues [note: many were early Korats]. The evidence is; to say the least, reasonable if not popular among us Siamese breeders. Since the Siamese Colorpoint system is the result of a recessive allele it can be carried for several generations without being detected unless close inbreeding is employed. If this is not enough, there are several indications that out crosses have occurred in this hemisphere over the years and there is some evidence that a similar situation might have occurred in Sweden. After all the cats are not all that particular about our breed classifications, and some of the breeders tend not to be too cautious - nor, in an organization as large as the Cat Fancy, can we expect everyone to be totally honest. There is this saving factor, however: most of the dedicated Russian Blue breeders tend toward rather close inbreeding to set type and consistently produce their show quality cats. With this type of inbreeding any recessives such as the cs (siamese, colorpoint allele) are very quickly discovered and can thus be eliminated if the breeder employes reasonable caution in the subsequent breeding program.

The "White Russian" problem is a very different can of worms. As far as our present data in cats goes we have no real evidence of any recessive white-coat color system other than possibly in the reported "albino" group. If this recessive system is indeed operating in Russian Blues it would never be expected to produce anything near green in eye color. At most the eyes would be expected to be a pasty pinkish blue, which could never be confused with green even by the most novice of the novice breeders. The two established whiting systems in cats are the dominant white and dominant white-spotting. In the case of the dominant white system there are no valid reports [. . .] of two non-white cats ever producing a kitten which was white due to this allele. At least one of the two parents has to be white. In the case of piebald white-spotting there are indications of variable expressivity and possibly incomplete penetrance. This lack of penetrance is extremely uncommon at most, and in order to get a solid white cat as a result of this system it would normally require that both parents be carrying the allele in an impenetrant [hidden] state and then have the resulting kitten be homozygous and for both alleles to be essentially totally penetrant. That really is asking a bit much, since penetrance tends to be reduced in the progeny of impenetrant phenotypic parents. Yes, it is remotely possible that there was a mutation to White in a Russian Blue, but we have discussed this rare event before don't bank on its being the answer.

By an odd set of circumstances, I saw a "White Russian" in a show only a few days ago. It was indeed white with the blue cap so frequently seen on White Persians, Domestics, Rex, etc. which is due to the dominant white allele [note: surely he meant white spotting]. Yes, it did have the broad flat forehead, low set eyes and reasonable bonnet ears I normally expect on Russian Blues. The body type might also have been considered reasonable for a Russian. There was one other small problem, it had a coat approximately an inch long, very silky like in the Turkish Angora. According to the catalog it was entered as a White Russian in the Shorthair division, I ask to transfer the cat to the Longhair division, but the owner objected, and since there were no other Shorthair New Breed and Color cats in the show, I did not press the point. Now since the Russian Blues are noted for their very short dense coats, this type of coat would not be expected, no matter how you rearranged the normal modifiers in the now existing Russian Blues I have seen in our show rooms over the past ten or fifteen years. Maybe in Europe Russian Blues are different, but according to the established breed standards in this western hemisphere, there is no reasonable way to obtain a cat with this coat type from two honestly registered Russian Blues, except by mutation. There is that bad word again. Now if you want to believe that two normal Russians according to our standards produced this cat, you certainly may do so but the mutational chances are like one in three million multiplied by one in three million. OK, it's possible, but an outcross is far more probable.

If we must, then why not call them "white Archangels?" Many years ago the late Milan Greer exhibited his "$5,000," or some such fabulous sum, "Russian Archangel." It too had this type of coat but was blue in color. Yes, many believe that our present day Russians are from the "Russian Archangel" and this may very well be the case; however, through the years the tat now registered in the stud books and shown in our shows no longer conforms to this coat type, but has been established as Russian Blue by name and has a very dense short cropped coat as one of its breed's identifying features. Besides if we are going to have a "White Russian" then I can only suggest that we be American about the whole thing and immediately produce a "Red Russian."

In Australia in the 1970s, Mavis and Dick Jones courted controversy when they started the Russian White. As a reader of National Cat in the pre-WWW 1990s, I was aware of these other colour Russians. Mavis Jones described her breeding programme in a letter to the Russian Blue Newsletter in 1977. The Jones' breeding programme took twelve years to produce Russian Whites of the correct conformation. They began by importing a white short-haired Siberian domestic cat owned by an official at the Thai Embassy in Australia. This was the only cat bred to the Russian Blue in Australia. Any Australian Russian Blue breeder outcrossing to Siamese would be permanently banned from breeding, so a compatible Russian cat had to be imported. This is no easy task because Australia has a long quarantine period. It then took the Royal Agricultural Society Cat Club (RASCC) of NSW (the cat control registry of the time) 2 years to grant permission to develop the Russian White as an experimental breed. During that time, the Joneses bred several litters from the Siberian white shorthair and one of their best Russian Blue males. Their own ruling body confirmed that the cats were Russian in conformation and permitted the cats to be exhibited. This opened the way for a formal experimental breeding programme under the auspices of RASCC of NSW. The strict rules meant every birth and death had to be reported. Every kitten that left the Joneses cattery had to be neutered, and no other cattery could participate in the breeding programme. Because the Russian Whites carried other colours, including blue, there was a huge fear of polluting the pure Russian Blue breed. Their two best white Russian females were bred to two unrelated Russian Blue males. For 4 generations, the best white female from each litter were bred to a total of seven Russian Blue males. Early litters also included silver-striped grey kittens (a colour found in shorthaired cats in Siberia), but the tabby trait disappeared after the 3rd generation. A black kitten from the 3rd generation was formally recognised by RASCC in 1977 and led to its own breeding line in Australia. The white cats were born with a small blue smudge on the top of the head, an indicator of good hearing. The fourth generation of Russian Whites achieved full recognition from the Royal Agricultural Society Cat Club of New South Wales in November 1975. By the 5th generation (1976) the cats were genetically identical to Russian Blues in all respects apart from fur colour. That meant the blue offspring of a Russian White crossed to a Russian Blue could be registered as Russian Blues.

Ingrid Nuyten imported an Australian Russian White male kitten, Yaralin Sjtsjoekin (b. 1993), a descendant of the Jones' breeding programme. He was bred to several Russian Blue queens, founding Russian White breed lines in Europe. He also carried blue. Sjtsjoekin was mated to a Russian Black female derived from chi from the UK Russian Black line. This appears to have been the only mating between a Russian White and a Russian Black, and the offspring included all three colours (the white cats carrying black or blue). This helped restore lost genes to the UK blood line. Blue-eyed or Odd-eyed Russian Whites can be registered with the GCCF, but not bred and can only be exhibited in pet classes. When a White Russian Shorthair stud from Australia was imported into the USA, it caused great controversy. Most American Russian Blue breeders proclaimed Russian Blues can only be blue! and any breeder working with other colours risked being boycotted. The battle-cry a Russian Blue can only be blue is nonsensical since a Russian Shorthair of any other colour is a Russian White, Russian Black etc, not a Russian Blue (and certainly not a white Russian Blue !). Underneath the coat colour, the structure of the cat is the same and it was a whim of the early cat fancy that only the blue colour was selected for perpetuation.

Because dominant white masks out other colours that are genetically present, the Russian White breed programme also gave rise to the Russian Black and to Black (Brown) Tabbies and Blue Tabbies. The Russian Shorthair group comprises cats of Russian Blue type but a wider variety of colours. Those with varying degrees of recognition are Blue, White and Black. Blue-pointed Russians and Lilacs have also occurred. Peach Russians (cream) and a blue-cream Russian Shorthair occurred in the USA in the 1990s (probably 1997). The Peach Russian and the Blue-Cream Russian came from Psykitt cattery when a Russian Blue female got pregnant by a domestic cat and produced cream and blue-cream offspring. Although one or two breeders became interested, the Peach Russian did not take off. The blue-tortie Russian was exhibited as a Russian Blue, but was not positively received. Some fanciers and registries dismiss all colours except for blue as indicative of mongrelisation even though the Russian Blue was originally developed using a variety of breeds. White and Black Russians are also bred in Britain and parts of Europe and have varying degrees of recognition (or lack thereof) in European registries. Perhaps Russian Creams will also be accepted in the future.

The Russian Shorthair is a long-legged, graceful, medium-size, muscular cat with a moderately foreign conformation. Its dense, plush "double coat" is tipped in silver. They have distinctive emerald-green eyes. Russian Shorthairs tend to be quiet-voiced, and can be shy and cautious with strangers, but are playful and affectionate with their owners. They are also intelligent and can learn to open doors and turning on water taps.

NEBELUNG, RUSSIAN SEMI-LONGHAIR

Although Russian semi-longhairs occur naturally in their home country, the Nebelung began as a semi-longhaired version of the Russian Blue, developed through outcrossing two American domestic cats to Russian Blues. Siegfried (b. 1984) and Brunhilde (b. 1985) both resembled Russian Blues, but with semi-longhair coats. Their owner, Cora Cobb enlisted the aid of TICA geneticist Solveig Pfleuger who advised her to define the new breed as semi-longhaired Russian Blue cats. Because the breed standard is identical to that of the Russian Blue, except for the semi-long coat, outside of the USA the breed was founded using long-haired kittens of Russian Blue parentage (in part reflecting different rules on registering/trading outcrosses to non-pedigree cats).

Longhaired Russian cats other than the Siberian exist naturally in their own country and in 1993/4, the first Nebelung in the Netherlands arrived from Russia. This was a purebred Russian Blue stud cat called "Timofeus" who turned out to be semi-longhaired. Even though he is not part of Nebelung pedigrees, his existence confirmed that the recessive longhair trait was already present among Russian Blues. Eastern European countries started recreating the Nebelung from Russian Blue type cats carrying a gene for longhair (Russian Blue type because the Eastern European cats were not registered as Russian Blues in a Western cat registry). In later years, it turned out that semi-longhaired Russian Blues (variants) were not uncommon in Russia and some joined Nebelung breeding programmes in other countries. In 1995 Cora Cobb imported a Moscow-bred Russian Nebelung born to Russians Blue. This cat, Winterday Georgin of Nebelheim, came from a Moscow cattery that had bred several prize-winning longhaired Russian Blues over the years.

The American and European Nebelungs' physical appearance mirrors the different appearances of American and English Russian Blues. In some European registries, it is treated as a long-haired Russian Blue, or Russian Semi-Longhair (just as the Russian Blue is a Blue Russian Shorthair). This allows long-haired variants of Russian Blue (shorthair) parentage to be registered as Nebelungs. The continued influx of Russian Blue blood keeps both breeds consistent in type. TICA recognises it as an entirely separate breed with Russian Blue as an allowable outcross. Under TICA rules, the outcross kittens are registered as Shorthair Nebelung variants carrying longhair; they are not used in Russian Blue breeding, only in Nebelung breeding (this allows TICA breeders to keep the longhair trait out of the Russian Blue gene pool). To date Nebelungs have not been bred to mirror the Russian Black and Russian White, although this option exists.

PIKA BUE (SHORTHAIR AND SEMI-LONGHAIR)

The Pika Blue is a colourpointed variant of the Russian Blue and Nebelung. The colourpoint variants arose naturally in Russian Blue and Nebelung litters in the 21st century as a result of emergency crossbreeding in the early 1940s. During, and immediately after, the Second World War, the Russian Blue was in danger of extinction in Western Europe. In order to save the bloodlines, cats were bred to blue-point Siamese with the intention of selectively breeding back to the Russian Blue standard later on (e.g. using imported cats that had never been crossed to Siamese) and eliminating the colourpoint gene. As a result of the outcrossing, the colourpoint gene lurked in some bloodlines until the present day. Because colourpoint is recessive, it remained hidden, but if two carriers were mated together it was possible to get blue-pointed, blue-eyed, Russian Blue kittens. This often led to the colourpoint-carrying parents being removed from the gene pool to prevent further spread of the colourpoint gene.

At Cattery Ladoga, in the Netherlands, a number of blue points were born: a colourpointed male from Russian Blue parents in 2013; two blue-point Nebelugs from the same Russian Blue female and a Nebelung male in 2014; a blue Nebelung male from a Russian blue female and Nebelung male in 2015; and a blue-point Russian from a Russian Blue female and Nebelung mle in 2016. In 2015, it was decided to breed and acknowledge the cats, under the name Pika Blue, and a search began for a suitable blue-point stud cat as none was available in the Netherlands. So much interest was generated that several catteries united together to breed the Pika Blue in a controlled manner.

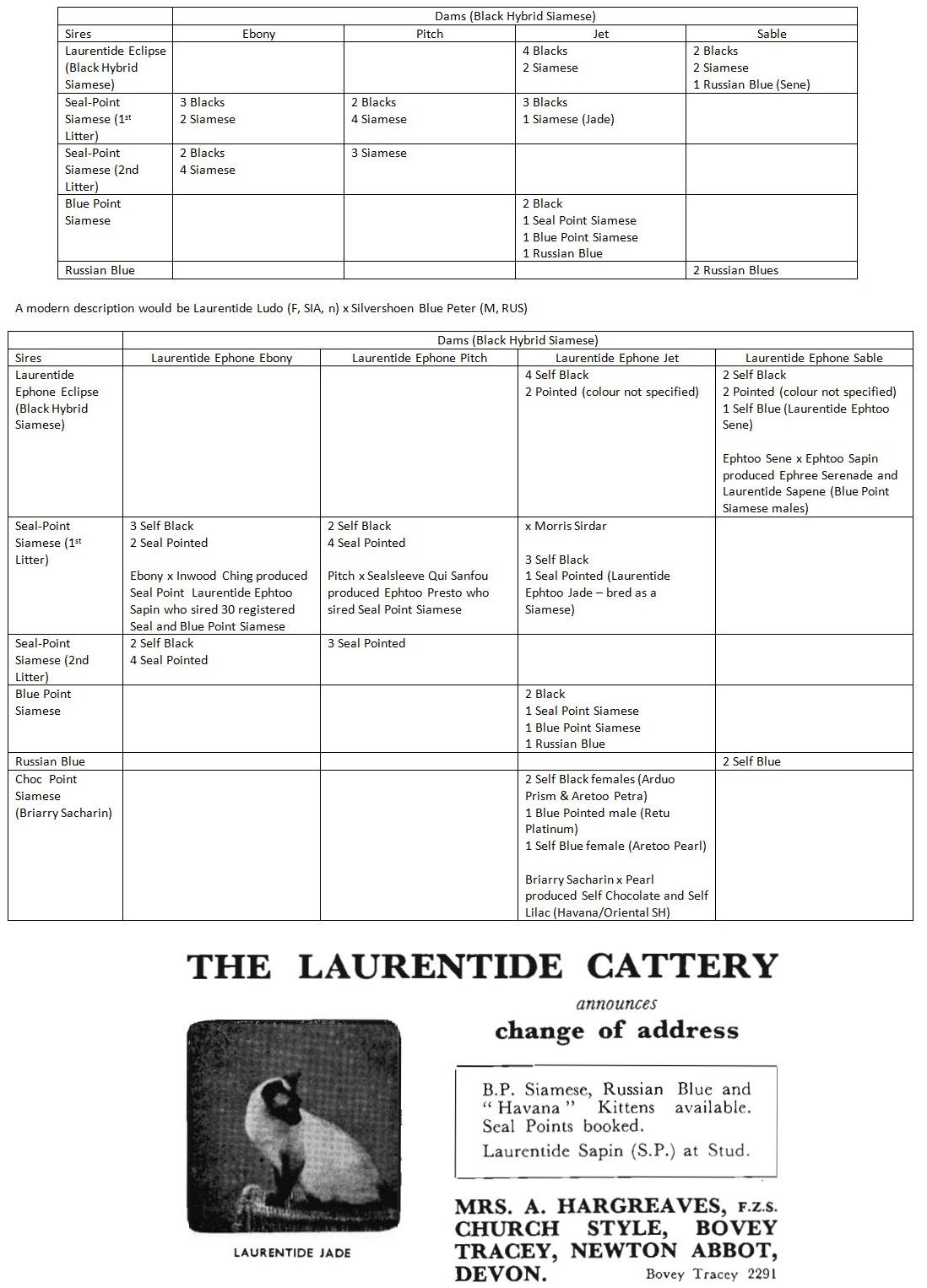

How did the colourpoint gene get into the Russian Blue gene pool? Perhaps the best documented crosses of Siamese and Russian Blues were those made by A. Hargreaves, F.Z.S and described in Our Cats magazine in October 1951 and June 1952. Early in 1948 Mrs Hargreaves decided to carry out some breeding experiments with Siamese cats, the principal object being to establish a more robust strain. There was a prevailing opinion among the public that Siamese kittens were not as strong as others, and many reportedly did not reach maturity. Hargreaves felt sure that hereditary factors, as well as environmental ones, were involved. Because hardiness may be established in animal breeding by using a good outcross, Hargreaves chose that method, carefully selecting an outcross pedigree stud with no undesirable factors such as white spotting.

No Black Shorthair stud was available at that time so the chosen stud was a Russian Blue, and she sent her Siamese queen, Laurentide Ludo, to be mated to Champion Silvershoen Blue Peter. Ludo produced 8 black Shorthair kittens, and Hargreaves let her rear 2 males and 4 females, all strong and healthy. These hybrid Siamese all carried the colourpoint gene from their dam, and the dilution (blue) gene from their sire. When mated back to Siamese the resultant litters on the average should contain half Black Self and half Siamese [i.e. half colourpoint]. When backcrossed to a Russian Blue they should produce Black Self and Blue Self.

The black hybrid male, Laurentide Eclipse, was mated in turn to two of his sisters, and three of those were also backcrossed to Siamese. The table shows the matings and the number and breed [what the 21st Century breeder would call colour] of the offspring. A few offspring were Siamese in colour but not in build. On the other hand, Hargreaves did not lose conformation, as proved by the photographs of Jade, and the fact that she won several awards. Meanwhile the Russian Blue, Sene, won two Firsts in Open Classes and Best in Show (ex Siamese) as a kitten. Later litters now from Siamese parents of Hargreaves' own breeding also looked promising.

Since starting the experiment no kittens were born with kinks in their tails. All the Siamese kittens sold in 1950 were followed up and were reported as hardy, and all but two as excellent pets. The normal voices of the first cross black females were much softer than Siamese, except when in oestrus and calling. The voices of their progeny varied considerably. Most were less talkative than ordinary Siamese, and one or two had a much softer timbre. Hargreaves continued to develop her Seal Pointed Siamese , Blue Pointed Siamese, and Russian Blue from the strains created, registering and exhibiting the progeny by phenotype, using breed names. In mitigation, post-war breeding stock was low and every cat that met the physical standard was important.

In an update 8 months later, she again wrote of the interest in breeding experiments among certain members of the Cat Fancy. Cross-breeding was undertaken with various aims in view: to produce new colour varieties, to increase stamina, to improve show quality, or merely to satisfy curiosity. This caused uneasiness in certain quarters. There was the fear that pedigree kittens of mixed breeding would be let loose on the market, and produce all sorts of unexpected progeny to the surprise and distress of the purchaser and the detriment of the Fancy. Hargreaves stated that those who experimented should have some knowledge of genetics and be able to predict the possible results of most crosses, and give a careful explanation with every kitten sold. Buyers of kittens for breeding should always study the pedigrees beforehand and demand further information whenever outcross breeds were shown.

Mrs Hargreaves stated, by way of an example, that all the kittens from a pure Russian Blue mated to a Blue Point Siamese would be Russian Blues [note: to the21st Century reader they will be Self/Solid Blue not Russian Blue ] . But those kittens would, if mated back to a Blue Pointed Siamese, also produce Blue Points as well as Russians. However, there were many factors which a pedigree did not record and which could not be deduced from the pedigree. There might be undesirable traits that could produce more havoc than a cat capable of having a litter containing three or four varieties.

At that point, several breeders were trying to improve the show quality of the Russian Blue cat by out-crossing to Blue Point and Seal Point Siamese. Hargreaves asked if the Russian Blue of the future might have undesirable Siamese qualities. Did breeders want Russian Blues wanted or "Blue Siamese"? What about Russian Blues with the raucous Siamese voice? The hereditary of voice was not known and voice and talkativeness were not recorded on pedigrees. Silent Siamese and raucous Russian Blues were undesirable. Hargreaves suggested the following be recorded for all Russian Blue kittens thus produced and that records be maintained by Russian Blue Cat Club alongside the pedigree TALKATIVENESS : (1) Voice seldom used. (2) Voice used moderately. (3) Very talkative. LOUDNESS : (1) Russian voice. (2) Moderately loud voice. (3) Siamese voice.

There were at least two ways of dealing with a Russian Blue cat possessing a Siamese voice if such a voice was considered undesirable. One was neutering, but if the cat was physically a credit to the breed, the raucousness might be eliminated by back-crossing to pure Russian, but to do that without losing the improvement in type might be difficult. Breeders who achieve some of their aims through cross-breeding experiments should not be blinded by success, but should be on a constant watch for undesirable traits, particularly when dealing with Siamese crosses.

SIBERIAN AND NEVA MASQUERADE

The Siberian cat is probably the most famous of the Russian breeds and is considered a naturally occurring breed. Its name hints at snowy landscapes pine forests. While the written history of the Siberian cat began in the 1980s, the Siberian cat has a much longer history in oral tradition. Longhaired cats have existed in Russia since at least 1000AD. Russian Longhairs or Russian Angoras were used in the 19th Century to develop the Persian breed. Those Russian Longhairs were mostly large, tabby cats with shorter and heavier boned legs than the Turkish Angora and a massive coat and ruff prototypes for the Siberian breed. Before the breed was established, if any asked what a Siberian cat was the answers would be large and fluffy and "not white," because everyone knew that fluffy white cats were Angoras! Folk beliefs about the Siberian cat were based on the idea of an animal that thrived in a harsh northern climate rather than on its actual origin. Siberian cat often simply meant a native semi-longhair cat that had lived in the Russian territory from time immemorial.

Cats probably arrived in Russian region on the early trade routes and no doubt included Angoras and Persians that may have interbred with wild steppe and forest cats. This is speculation because there is little documentary evidence of cats in Russia and only vague descriptions. The history of the Siberian breed began in the 1980s with the birth of the cat fancy in the Soviet Union. The first cat club and the first cat show - was in Riga [now in Latvia], followed by Moscow, then Leningrad. Dozens of cat lovers turned up with their pets. There were already illustrated books about cats, and hopeful owners tried to match their cats to the breeds depicted. From the homes and factories came cats that owners entered "Maine Coons", "Norwegians", and "Balinese." Shorthaired colourpoints were called Siamese by the owner. Of course none were those breeds, but some became the foundation for a native Russian breed and what better name for a breed than Siberian cat as this name was already rooted in oral tradition.

The modern Siberian breed developed, to some extent, after the Second World War from free-ranging cats from Leningrad (St Petersburg) and Moscow. The colourpointed variety (Neva Masquerade) appears to have originated during the 1960s through matings with colourpointed feral cats in the Neva River region in Leningrad. However, they were unknown outside of Russia until borders with Western Europe began to open up. Where did those colourpointed feral cats came from? Was it a natural spread of the colourpoint gene from Asia or had there been matings with pet Siamese cats belonging to wealthy or well-travelled families at the end of the 19th/start of the 20th century? Although the Neva Masquerade is not due to intentional crossing with colourpointed longhairs, a Himalayan breeder, Elizabeth Tyrell, became involved with Siberians and this has raised suspicions among some.

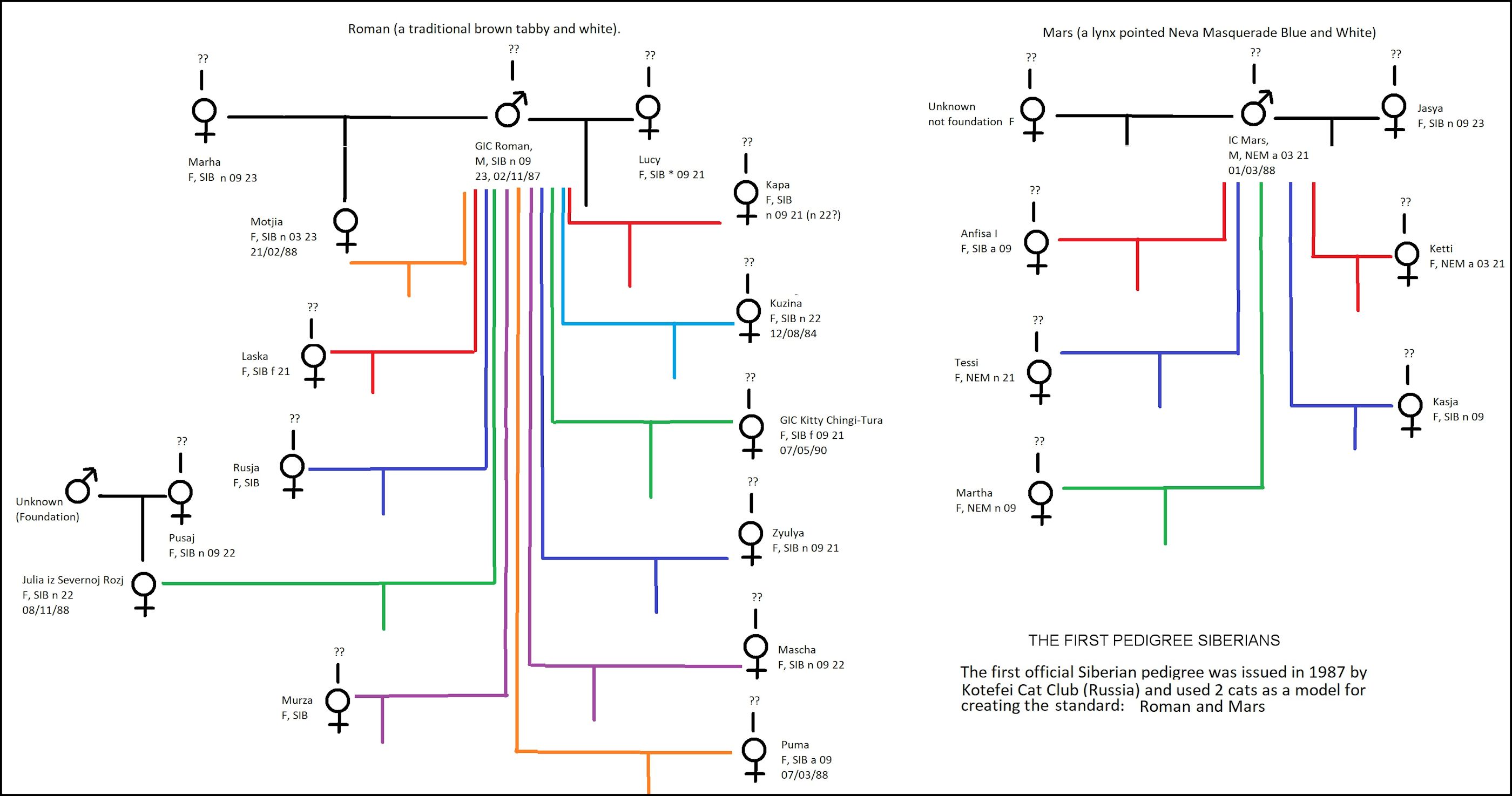

It had to be semi-longhair, but the local cat populations varied in conformation so cat fanciers had to decide what features to fix in their new breed, partly based on the prevailing type and partly based on making the Siberian cat distinct from the Maine Coon and Norwegian Forest Cat. The Siberian was recognised by the Kotofei Cat Club in Moscow in 1987. In 1990, after some refining, a breed standard was adopted by the Soviet Felinological Federation. In 1991 the first international standard was developed and the newly formed WCF was the first to recognise the Siberian and its colourpointed sister-breed, the Siberian colourpoint (Neva Masquerade).

At the May 1989 Moscow cat show, almost half of the 190 cats were listed as Persian. In the Unrecognised Long-hair and Semi-longhair section there were 12 Siberian cats, none with registered parents. Some of the cats shown simply as Domestic cats" would later be transferred to the Siberian category. At the Riga show in September 1989, 164 cats are listed, half of them Persian. One of the Balinese was later transferred to the Siberian category. Siberian and Neva Masquerade cats appeared in the section for Unrecognised Breeds. At the Moscow show in September that year the Siberian appeared as a breed group . . . and another Balinese was transferred to the Siberian section. In September 1989, a group of breeders from Leningrad and Moscow applied to register Siberian cats in the newly-created CFF. In August 1990 it was formally recognised in two varieties: Siberian and "Nevskaya Masquerade."

In the 1990s, despite plenty of breeding stock, its popularity waned. The Siberians exported earlier to East Germany and Czechoslovakia had been the non-pedigree versions that were lighter in type. The second wave of exports were the registered pedigree Siberians, but catteries outside of Russia tended to adopt their own standards. The revised 1991 WCF standard mysteriously added high cheekbones to the rounded form of the head, and the tail was changed from long to very long - making it more like a poor quality Maine Coon. Greater emphasis was placed on head-shape and broad low cheekbones (found in the Leningrad and St Petersburg populations) in the standard of the POF club in 1991. In 1994, at the ICEF seminar, head shape and medium tail length were included in the more detailed standards now used by the SFF and WCF. There became more emphasis on correct coat type. Siberians and Neva Masquerades arrived in the USA during the 1990s. Siberians were recognised by FIFe in 1997. In America, the standard was changed in order to maximise the number of differences from close breeds. Everything head eyes, body became rounded in the American Siberian with little emphasis on the broad, low cheekbones. In Europe there were widely differing types ranging from lightly built cats with long limbs, long tail, long muzzle, and high cheekbones and some standards stated without undercoat. Over time, the European versions have become closer to the Russian standard.

Its dense, triple coat is not shaggy. Its coat is more dense in the winter. Its body is shorter than either the Maine Coon or Norwegian Forest Cat. The protective seasonal coat and no extremes of conformation indicate a cat that evolved to survive in a harsh climate. Females may be considerably smaller than males. Although they may take 4-5 years to mature physically, Siberians reach sexual maturity relatively early. The females often bond closely to only a single mate who may take an interest in rearing the kittens. Almost all colours and patterns occur, including colourpointed varieties. Some registries recognise those colourpointed cats separately as Neva Masquerade ( masked cats from Neva ). In the fancy breed, brown and silver tabbies are the most popular colours. Brown tabby can have a golden appearance. The colours not accepted are chocolate, cinnamon, lilac, fawn and apricot. The Burmese pattern and mink patterns are also not permitted. Some western lines of golden Siberians may carry Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy due to inbreeding of limited foundation stock during the 1990s. In addition to its looks, the Siberian is popular because its saliva contains no Fel D 1 protein which is responsible for 85% of cat allergies. It is estimated that only about 10% of cat allergy sufferers are allergic to Siberian cats (because they are allergic to other proteins).

TOYBOB (FORMERLY SKIF-THAI-DON AND SKIF-TOY-BOB)

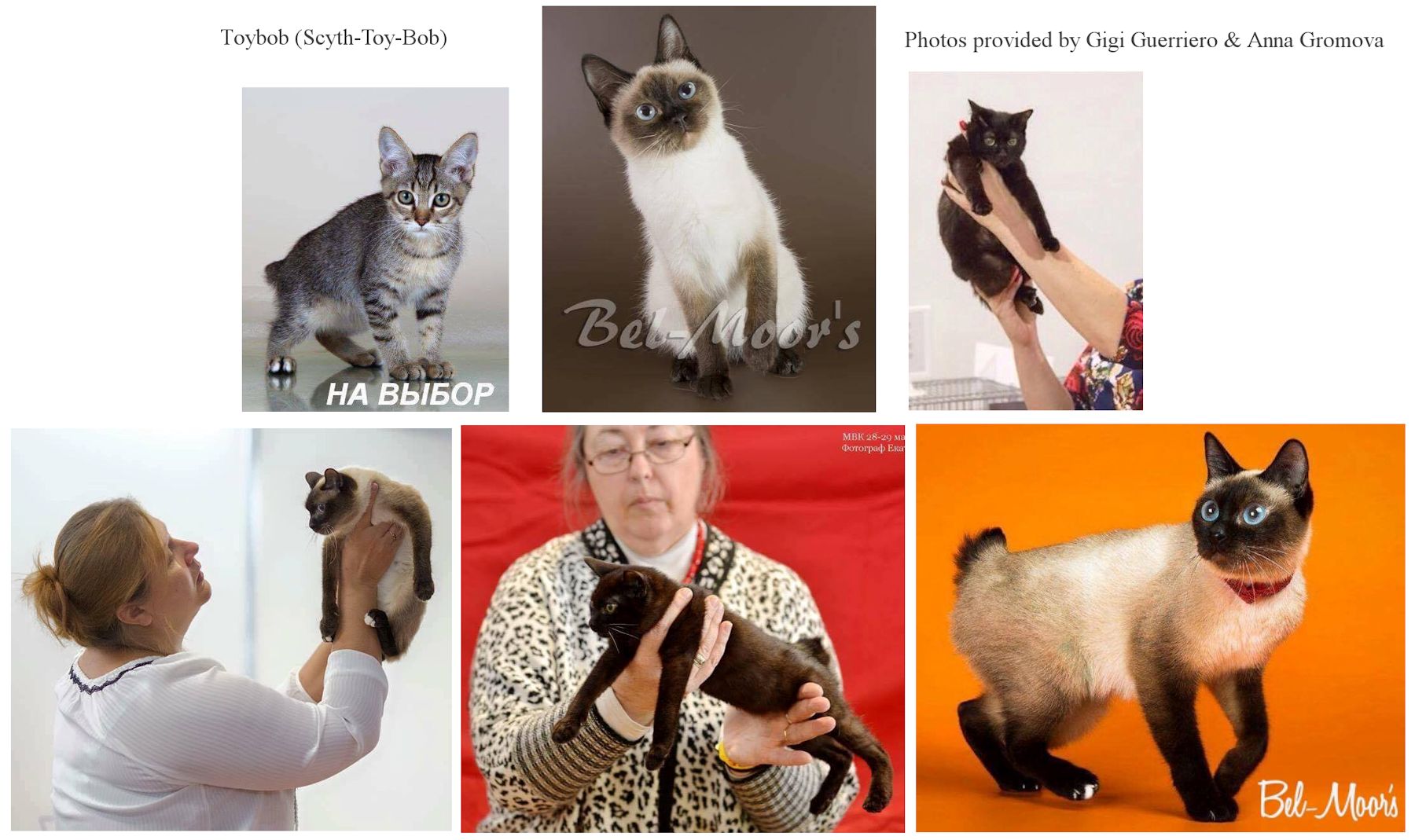

The Toybob cat is often referred to as one of the smallest of all cat breeds and is a small cat that should not grow any larger than the size of a 6-month-old kitten of a well-developed domestic cat. They have a compact body, well-developed musculature, a relatively deep wide chest, and a short tail that consists of several distorted vertebrae (visible length of 3-7 cm). Because its head and legs are in proportion to the body, it is considered a miniature cat and does not have the same dwarfism as the Munchkin cat. Regardless of their size, they are healthy animals with a rounded wedge-shaped head, low and round cheekbones, a short wide muzzle, and a slight curve to the bridge of the nose. They have a flat plane above the brows, a strong chin, and medium-sized ears set high up and straight. They have large, slightly upwards, slanted rounded eyes. When wide open, eyes can appear larger and rounder. The big-eyed expression is what gives the Toybob its sweet-faced look. There is both a Shorthair and Longhair variety, with Toybob Shorthair more common at this time as not all professional cat associations have yet approved the longhair variety.

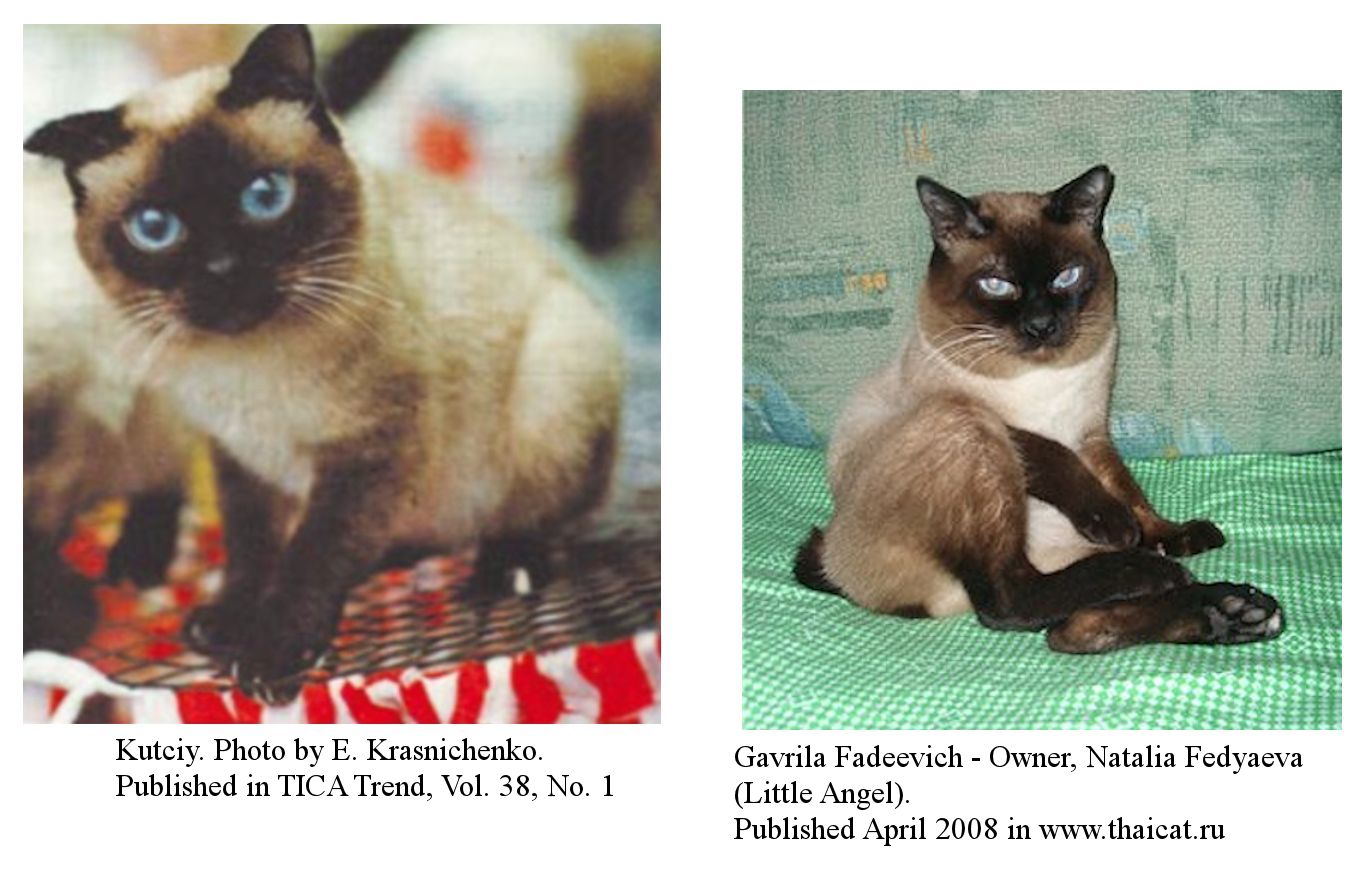

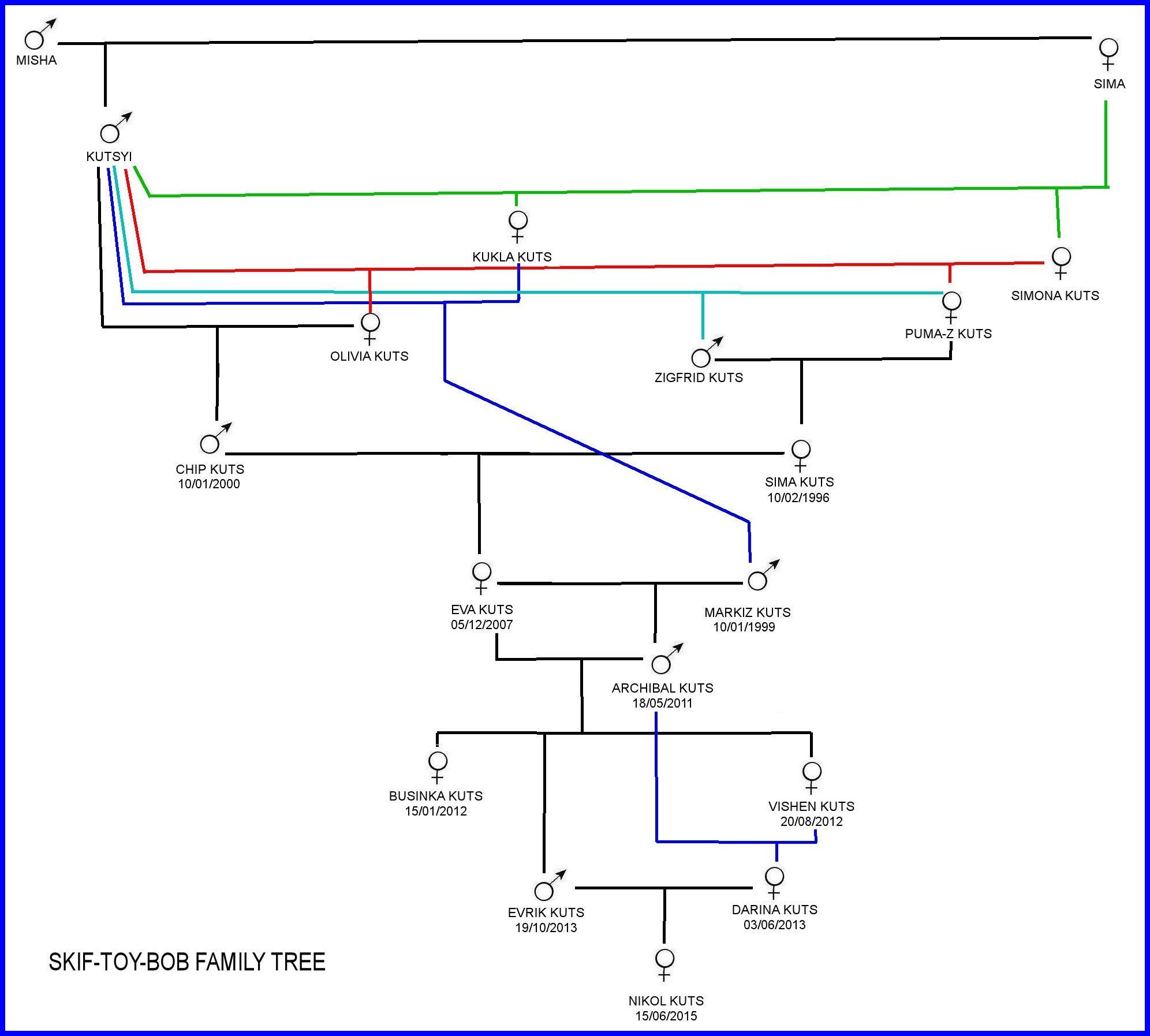

The Toybob cat was first documented in the Rostov Region of Russia in 1983 when Elena Krasnichenko adopted a stray seal-point Domestic cat. By her accounts, this cat looked very much like a Traditional Siamese cat, except for its shortened tail. Krasnichenko later bred this male to another stray brought home by her mother, a bobbed tailed seal-point female with an unusual curled kinked tail, and in 1988, the breeding of these two cats produced an unusually small bobbed tail kitten she named "Kutciy," which became the progenitor of the breed, first called Skif-Thai-Don. (also known in the longer form, Skif-Thai-Toy-Don). To this day, Krasnichenko breeds her Toybobs only in the seal-point color and pattern.

By the late 1990s, the Toybob were nearly extinct when a breeder from the Urals of Russia, Alexis Abramchuk of Si-Savat cattery (inactive), begun to broaden the breed's limited gene pool by adding Domestic cats. When Si-Savat discontinued their breeding program, Natalya Fedyaeva of Little Angel cattery (inactive), acquired from Abramchuk, a small male "Gavrila Fadeevich." Elsewhere, she acquired two Skif-Thai-Don females, one being Gavrila's sister and began her expansion of the breed. Fedyaeva had observed that cats of very similar phenotypes to the Toybob were spotted living locally around barns and streets in her region. Some of these native cats were also of small size with kinked tails or kinked bobbed tails but seen in colors and patterns other than seal-point. Fedyaeva, along with other local breeders, began to work on developing the Toybob cat's initially small genetic pool by adding those found domestic cats as well as other similarly phenotyped breeds. Fedyaeva began to refer to her cats as "Scyth-Toy-Bob" to differentiate them from the Skif-Thai-Don. In the 2000s, due to significant differences in breeding plans, the Toybob breed split into the two distinct breed groups from two different regions; the Rostov bred Skif-Thai-Don and the Ural bred Scyth-Toy-Bob. With each breed group promoting a slightly different standard within the cat clubs and shows. A separation that lasts until 2017 when both groups came to the consensus it would be best for the two groups to get together again and drop any form of prefixes from the breed's name, making it easier to unify the breed's standards across all associations worldwide.

The breed has been known under several different names and is a significant component of its history. It was in 1994 when the Toybob name was suggested by WCF judge and feline book (Mironova, O.S. Aboriginal Cats of Russia: From Attics and Backyard To World Recognition. Saint Petersburg. 2003. Print.) author Dr. Olga Mironova be given to all Toybob cats in development. In 2004, Toybobs were imported to the United States by an American Burmese breeder, Mila Denny of Sacredspirit cattery, and four years later, the cats entered Experimental status within The International Cat Association (TICA) under the general name, Toybob. In 2014, the majority of TICA registered Toybob breeders began to work in close cooperation, focusing on advancing the breed's recognition. A year later, led by an official breed club "International Toybob Cat Club" (ITCC) formed, with the dedication to promoting the breed worldwide, mentor new breeders, unify the Toybob standards and advance the breed across all Cat Fancy associations. In 2015, the Rostov-based breed group "officially" changed the name of their cats from Skif-Thai-Don within a couple of other small Russian Cat Fancier Associations to the hyphenated "Toy-Bob," causing some confusion. As aforementioned, in 2017, both groups came to the consensus it would be best for the two groups to unite. At the end of the decade, the breed gains Championship status outside of Russia within two North American associations and Europe's World Cat Federation (WCF) with further work underway in getting the breed to Championship status worldwide.

The Toybob cat's most distinctive feature is it's kinked bobbed tail, and just like other known kinked bobbed tail breeds, the tail does not affect its agility or health. At the time the breed was registered with TICA, little to no genetic research had been done on the breed to learn more about the unique genes behind the Toybob cat's small size and bobbed tail appearance. Leading to much speculation as to it having possible relations to other known bobtail breeds. In 2016, the ITCC decided to perform preliminary testing with the world-renowned geneticist and feline expert Dr. Leslie A. Lyons to find any connection to other bobbed tail breeds. It resulted in there being no Manx gene nor any relation to any other bobtail breed (e.g., Japanese Bobtail, Kurilian Bobtail), and the conclusion was we are dealing with an entire new bobtail mutation. Toybob overall health is rather robust due to the harsh environment from where the breed originated. Also, the continued use of native Russian Domestic cats in the breed development maintains excellent genetic diversity and good health. The breed has no known health or genetic problems and is known to be long-lived even well past 15 years. Although a diminutive cat, the Toybob might surprise some as it carries nice sturdy weight to it for its overall small body. Toybobs are bred in both shorthair and longhair (semi) varieties in a wide range of colors, although pointed colors are the most common.

Feline traits notwithstanding, the Toybob has all of the qualities one looks for in a companion cat. Toybobs thrive when they are with their people. The Toybob is intelligent, good-natured, affectionate, and social, making it easily get along with other friendly animals. Individuals who love the cat can't imagine life without one, and many can't imagine life without two or three.

UKRAINIAN LEVKOY

The Ukrainian Levkoy is a Ukrainian, not Russian, breed, but is included here because it was developed from the hairless Donskoy. It is currently only recognised by Ukrainian and Russian cat clubs.

It was first developed in 2000, when Elena Biriukova in the Ukraine crossed Donskoy females with Scottish Fold males. This results in a distinctive appearance combining folded ears and hairlessness. Oriental and Domestic cats were also used in breed development. It was recognized in 2005 in the Ukraine by ICFA RUI (Rolandus Union International), gaining championship status in 2010. It was recognised in Russia in 2010 by ICFA WCA, gaining championship status in 2011.

The Ukrainian Levkoy has a slender, medium-to-long, muscular body and long legs. The head is almost dog-like in shape. The ears are large and set high and wide apart. In ideal show specimens, 1/2 to 1/3 of each ear is roundly folded forward and down, without touching the head. Straight-eared Levkoys occur and are important in the breeding programme. Ukrainian Levkoys are sociable, friendly, playful, and intelligent.

Because the gene for folded ears is associated with skeletal problems, two fold-eared individuals must not be bred together. When breeding Levkoy-to-Levkoy, one of the parents must be straight-eared. As a young breed, it is also outcrossed the Donskoy, Scottish Fold, Peterbald and to household pets that have the correct conformation.

URAL REX

In 1988 a domestic cat from the suburb of Ekaterinburg produced a litter of 3 kittens. Two of the kittens had curly coats. This was the beginning of the modern Ural Rex breed. According to local people the variety existed as free roaming domestic cats since the 1940s, but were never selectively bred.

It is medium in size, with a muscular body and slender, medium-length legs. The head forms a short wedge, with prominent cheeks and a broad nose. The short curly hair is similar to the Cornish Rex, but test mating with Cornish Rexes and Bohemia Rexes resulted in straight haired kittens indicating the Ural Rex has an unrelated mutation. Ural Rexes occur in both shorthair and semi-longhair versions. The fur is fine, but very dense. The coat is very densely curled with double waves. Full development of the waves can take up to two years. Ural Rex kittens display open waves at around 3-4 months old.

The Ural Rex breed foundation male was Vasiliy, born in 1988. He was later mated with his mother, Mura, a black-and-white domestic cat. The first litter was born in 1994 and included a rexed black-and-white male called Bars, and a rexed black-and-white female called Murka. In 1997 a breeding program was set up in Moscow using two females Merlushka and Bonny, and a male Clyde (or Clide).

Kittens often have a greyish tinge to the coat. This later becomes a brownish tinge. Black tabby Ural Rexes have a striking golden background colour. Most colours are permitted, excepting chocolate, lilac, cinnamon and fawn. Solids, tabbies (classic, mackerel and spotted) and torties are permitted with or without white markings (ranging from white spots to van-pattern). Silver tabbies, shaded silvers, smokes and the corresponding golden series of colours are all permitted. All of the colours can also occur as colourpoints as the colourpointed pattern occurs naturally in parts of Russia.

The Ural is cautious and sensitive, but is calm and sociable with its family.

USSURI

The Ussuri was described as a rare natural breed originating from Russia's Amur River region. It was possibly descended from natural hybrids between domestic cats and Amur Leopard Cats (Prionailurus bengalensis euptilura the most northern subspecies of the Asian Leopard Cat). Semi-wild Ussuris then bred naturally with local domestic cats including European Shorthairs and Siberians. The claim of hybrid ancestry was based on the cat's appearance and on folklore.

This breed was described by O. Mirovaya in 1993 and came to the attention of the West when breed standards for several indigenous Russian breeds were translated into English soon after. Since that time, nothing more has been heard about it, and it is the only breed from that circulated document that has not made an appearance in the west. The Ussuri had a breed standard in Russia but was not recognised as a breed by any other major cat registries. I can find no authenticated photographs of this breed. It seems that work to refine and improve it, in particular to improve its temperament, were unsuccessful and it may have become extinct not long after being documented. All information about its appearance comes from the article distributed in English in the mid-1990s.

The Ussuri was described as muscular, but not massive in conformation. Its mature weight was around 12 pounds. It had medium-length muscular legs and firm, rounded paws. The neck was firm but not long. The ears often had lynx-like brushes. The tail had a rounded tip like the European wildcat - and this is a clue to its probable ancestry and its personality! The European Wildcat freely interbreeds with domestic cats, producing fully fertile offspring, and is a more plausible parent than the Leopard Cat, especially considering the breed's allegedly challenging temperament. The short coat of Ussuri cats was glossy and close-lying, with a thick undercoat.

It had a distinctive colour and modified tabby pattern: vertical solid or merged spots on the body with lines on the forehead and two or three bronzed lines on its cheeks and one or more solid or broken necklaces of bronzed tone on the neck and chest. There was a dark dorsal stripe. The flank pattern consisted of stripes, rings, or spots on golden-brown or golden-fawn background and bronzed buttons (belly spots) on the paler belly. It should have distinct lines on the legs, with the upper part being a bronzed colour and the lower part being the ground colour. The tail should be ringed and have a dark tip of ground colour.