|

|

|

|

Indian Cat (1903) |

Indian Cat (1902) |

LOST BREEDS - INDIAN CAT AND MALAY CAT

INDIAN CAT

|

|

|

|

Indian Cat (1903) |

Indian Cat (1902) |

"The Queen" (a weekly journal for upper class ladies) reported an Indian cat being exhibited at the Cat Club's Show in 1900 at St. Stephen's Hall, adjoining the Aquarium, Westminster:"the first prize winner of the opposite sex, Lady Beresford's Norematial, an Indian cat, is quite as good a specimen, inferiority of size taken into consideration."

Animal Life and the World of Nature (1902-1903) wrote: "Some of the varieties of the domestic cat of India of India are evidently derived from the smaller wild breeds of that country. From what variety is derived the peculiar cat whose photograph we give (lent us by Messrs. Harmsworth) it is hard to say. The colour of this cat above is a beautiful light chestnut red, fading through various shades of golden yellow to white underneath. On the sides he is beautifully pencilled, and faintly striped on the legs. The forehead is wrinkled like that of a Chow dog; head, long, shallow and pointed, legs very long and slender, the tail of great length and tapering like that of a pointer. The coat is extremely short; ears thin, large and mobile; eyes, piercing in expression, of clear amber colour. His calls are varied, and somewhat resemble the raucous voice of the Siamese cat. The most careless observer will at once note certain structural features in which this cat differs from the common cat. He has won many first prizes, and is the property of Mrs. H.C. Brooke, of Welling."

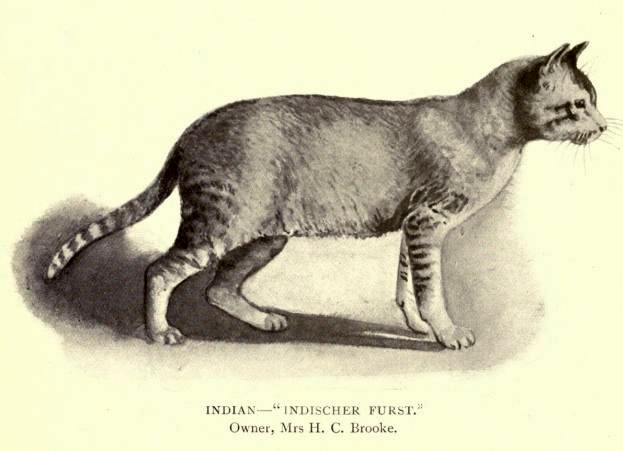

HC Brooke's own wife owned an "Indian cat" (named “Indischer Furst”) and in 1903, Brooke wrote, "Very curious and handsome is the Indian cat 'Indischer Fürst' exhibited by Mrs H C Brooke. His most striking peculiarities are the length and slenderness of his limbs, the extreme shortness of his coat, and his thin and tapering tail [...] His ears are small, but as a kitten they were of enormous size, and with his long and pointed head gave him a most weird experience. The voice of this cat is very variable, and far more resembles the raucous call of the Siamese than the voice of any European cat." This cat, and his sister, were apparently stolen from a hotel in Bombay by an English sailor. He was given to a shoemaker in Leytonstone and later sold to Mrs Brooke for a considerable sum plus part-exchange of a kitten with seven toes on each of its paws (these being lucky mascots for sailors). In retrospect it seems that the cat was probably an Oriental (of the older style), but in Brooke's times only the Siamese was known. The Siamese of that time being far less extreme than the modern variety; this painting in Frances Simpson's "Book of the Cat" (1903) indicates it to be similar to the Abyssinian in pattern, but sandy red in colour. It may have been assimilated into the Abyssinian breed along with another vanished shorthair of the time, the British Tick (a ticked tabby of British Short-hair conformation). The "sandy red" Indian Cat may well be the origin of the cinnamon gene since all cinnamon Abyssinians can ultimately be traced back to Brooke's cattery.

C H Lane, in "Rabbits, Cats and Cavies" (London, 1903), wrote: "The Indian Cat. Some of the varieties of the domestic cat occasionally seen in India, are apparently derived from crosses with some of the smaller wild breeds found in that country. From which particular variety the Indian cat is derived, I have no positive information. The colour of the upper parts of the body is a pale chestnut red, passing through grades of yellowish shades to almost white on the under parts of the body. The forehead is puckered or wrinkled ; the head somewhat long, pointed and narrow in shape ; with legs long and fine in bone ; and the tail unusually long and tapering, and carried with a curve. The coat is thick, but quite short ; its ears are large but thin, with rather a forward carriage, very erect. The eyes are not particularly large, of rich amber colour, and very brilliant in expression. The colour on the sides is freely ticked or pencilled, but on the legs and thighs appear slightly-marked stripes, and on the tail are rings of the same colour. In tone of voice it is more like the Siamese than any other cat with which we are familiar, and it is found to vary in this respect at different times. Except in point of colour, it is more like what we know as the Abyssinian or Bunny Cat than any other variety seen at exhibitions in this country, but there is no reason to suppose it is a variety of the same animal, being thought to be a native product of India, and not found in any other country." In the same book, the Abyssinian is described thus: "The head should be fairly large, round, not very short, but full in face, with dark red nose, shortish, strong neck, deep chest and shoulders rather wide. The ears should be moderately small. The eyes round and full. The legs fairly long and well-boned, with small round feet. The body, rather compact and cobby, than long; well rounded at sides, not tucked-up looking and with strong hindquarters. The tail, thick at base." (Since that time, the Abyssinians, which were crossed with British ticked cats, has changed greatly in shape.)

In the Letters page of "Our Cats" 3rd October, 1903 we have the statement "Mrs Brooke informs us that she has now four Indian cats of the same breed as 'Indischer Furst', who created such a sensation when he came out at the [Crystal] Palace two years ago, and whose portrait (albeit justice not done to him) appears in Cassell's 'The Book of the Cat'. The new specimens are quite red all over, not having white throats and forepaws like the original, but have not such short coats as he has."

Brooke described this cat in Cat Gossip in 1927, “A remarkable Indian Cat: Only a small proportion of present-day exhibitors, we think, will remember the remarkable Indian Red Cat, who created such a sensation on his appearance in 1901. He gave rise to a lot of discussion, and is much of a mystery to the present day, when his skin is, I believe, in the possession of Mr. R. I. Pocock, the former Superintendent of the Zoological Gardens, who is, however, unable to account for him. As a kitten he was one of the most remarkable looking cats we have ever seen. When about four or five months old, his ears looked very large, and, with his very pointed face, gave him almost the appearance of a young fox. His legs were long and slender, his beautiful whip tail would have done credit to a Pointer dog; his coat was extraordinarily short, almost like that of a freshly clipped horse. His colour was a beautiful rich chestnut red, fading into paler tints on the belly, and legs and tail were slightly marked. His forehead was wrinkled like that of a Chow.

He was stolen from an hotel in Bombay, along with another kitten, which died en route. This one fell overboard once, and was rescued with difficulty; on another occasion he got into the coalhole on the boat, and was brought up as black as a crow. Arrived in London, he got on the roof of the house, and perambulated the roofs of the East End tenement wailing like a lost soul. He did a good bit of winning, and caused a great sensation. Like so many Oriental cats, he would walk perfectly in the street on a lead. These were the days of the ring classes,” and we remember his clearance of the ring on one occasion when another tom was rude to him. On one occasion a cat member of his type, but of different colour, was exhibited by the Hon. Mrs. McLaren Morrison; it was thought to be an Indian Desert Cat, which, however, is quite a different species, and not a domestic cat.

We mated him to an Abyssinian queen, and she had a couple of kittens exactly like him, except that they were not so fine in coat. Unhappily they only lived a very short time. Now comes the incident which has made us a believer in Telegony, or the influence of a previous sire. This Abyssinian cat, when we broke up our kennels and cattery in 1904, remained in London, the Indian going to Kent. Some eight months after-wards, the Abyssinian, having mated with some stray, produced, amongst a litter of blacks and tabbies, one beautiful red kitten the image of the former Indian lover. Such a kitten has never been since observed to our knowledge. How [can we] explain this but by Telegony. We are well aware that modern scientists do not recognise Telegony; at the same time the wiser ones preserve an open mind on the question, and we may well here quote Mrs. Veley's words of a few weeks back as regards another matter:- “I think, after fifty years spent in the study of biology, we should not be too cocksure that things cannot happen because they are rare and seem unlikely.” In any case, the extreme sensibility of the cat makes it appear to us to be one of the most probable animals to indulge in some such peculiar behaviour, if at all feasible. A beautiful miniature of this cat was painted by the celebrated miniature painter, our old friend, the late Mr. J. W. Bailey, or “Pa” Bailey, as he was affectionately known to dog show frequenters of thirty years ago. At Cruft's Show, in 1902, he passed the case containing this with a number of doggy miniatures around a circle of friends for inspection; carelessly it was allowed to reach the hands of a stranger, and about a hundred guineas’ worth of miniatures disappeared, and were never heard of again!"

Line-chasers think it possible that the Indian Cat contributed cinnamon to the Abyssinian gene pool, but according to Brooke, the only kittens sired by this cat (when with Brooke) died before breeding age. Those are his only recorded offspring bred by Brooke, but Ras Brouke . Brooke also mentions his Indian Cat’s habit of going onto the rooftops of his East End home. That means it may have contributed to the gene pool of the local stray population. Eight months after Brooke broke up his cattery, keeping the Abyssinian female with him in London, and sending the Indian Cat to Kent (presumably to his home in Welling), the Abyssinian female produced a red kitten in a litter sired by a stray cat. It is conceivable that the stray cat in question was a son of Brooke’s Indian Cat.

It's quite likely that one of Mrs H.C. Brooke's Indian Cats was bred to Abyssinian cats, perhaps after going to Kent, and introduced its colour genes into the Abyssinian gene pool. Later on, Brooke's "Imported African Wild Cat" was mated to Claude Alexander's Abyssinian "Red Rust" and produced a female called "Goldtick." Goldtick was mated to Brooke's red self shorthair "Ras Brouke" in the 1920s and produced "Tim the Harvester" (registered as ruddy, but also described as chocolate) who may have introduced sorrel and cinnamon into Abyssinian lines in Britain and to the USA. These wild cats, along with the British Tick, would have introduced an assortment of recessive genes for example non-agouti as demonstrated by the solid black Woodrooffe Nigra whose son Menelik became an influential sire. Maybe the Indian Cat isn’t completely lost after all – maybe its colour genes lurked in the gene pool until they were recognised as a colour variety of the Abyssinian breed.

MALAY CAT

In 1783, Willian Marsden, Fellow of the Royal Society and late Secretary to the President and Council of Fort Marlborough wrote in "The History of Sumatra" of the Malay Cat: "All their tails imperfect and knobbed at the end."

In 'The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication", Darwin wrote "throughout an immense area, namely, the Malayan Archipelago, Siam, Pequan, and Burmah, all the cats have truncated tails about half the proper length, often with a sort of knob at the end. [...] The Madagascar cat is said to have a twisted tail." (The latter comment may be due to the use of "Madagascar Cat" to mean the Ringtailed Lemur) Mivart had corroborated the statement regarding the Malay cat, of which he said the tail "is only half the ordinary length, and often contorted into a sort of knot, so that it cannot be straightened [...] Its contortion is due to deformity of the bones of the tail," and added that there was a tailless breed of cats in the Crimea.

Miss Lowndes, daughter of writer Mrs Belloc Lowndes, described a Malay kitten recently acquired, along with its mother, from the Straits Settlements. "It has a triple-kinked tail. It is, unfortunately, not of the spotted kind, but these seem to be very rare nowadays." More information was provided by the Director of the Raffles Museum and Library at Singapore "The tail which distinguishes these cats may be clubbed or kinked, very short or of medium length, and the animals themselves of many colours - plain, piebald, or patterned."

The cat fancier and prolific author, H C Brooke, wrote a widely published paper called "The Malay Cat" in 1927. He wrote that the peculiar variety of domestic cat was very little known in Britain and was becoming scarcer in its native habitats, probably due to crossing with long-tailed cats. He noted the possibility that Manx cats were descended from it, citing the Spanish Rock (shipwreck) theory and the prevalence of spotted tabby Manx. Both the Malay cat and the Manx were companionable and "doggy" and a resident in Sumatra had reported to Brooke that it was quite common to see the natives going about their business followed by their cats. "About a quarter of a century ago [1880s] I saw in Holland three beautiful Malay cats, of a sort of drab colour, spotted all over with very clear cut dark brown spots, much resembling those found in some of the Palm Civets. At about the same period, too, some very similar specimens were at the Jardin d'Acclimatation in Paris. The tails of these cats, about three or four inches long, were tightly screwed, or at least the tail formed three complete revolutions. The 'screw' tail, as also the spotted type of colouration, appear to be becoming very rare."

A photograph of a young Malay cat was supplied to Brooke by Mr Boden Kloss, Director of the Raffles Museum in Singapore. Brooke noted that it resembled the Australian cat he had once owned, except that the Malay cat's tail was kinked upwards, while the Australia cat's triple-kinked tail was carried downwards. Mr Boden Kloss was familiar with this type of cat and wrote "A fair proportion of the cats of Singapore seen in native villages are short-tailed animals with a kinked tail. There would [be], I should say, three or four kinks. In colour they may be tabby, or boldly black and white. As a point of interest it may be noted that Felis planiceps [Flat-Headed Cat], one of the wild species of the peninsula, tends to resemble the domestic Malay cat in the matter of tail." Brooke commented that F planiceps was unlikely to be inter-fertile with domestic cats. He reported other sources as commenting that pure Malay cats (that had not been allowed to interbreed with ordinary cats) were said to have a "wild animal odour" most unlike the ordinary domestic cat.

R Shelford, former Curator of the Sarawak Museum wrote in his book "A Naturalist in Borneo" "It may be mentioned here that the domestic cat of the Malays is quite a distinct variety [...] it is a very small tabby with large ears and a body and hindlegs so long that it lacks all grace. The tail is either an absurd twisted knot or else very short and terminating in a knob; this knotting of the tail is caused by a natural dislocation of the vertebrae so that they join onto each other at all sorts of angles." Brooke added that the length of hindleg was a trait shared by the Manx.

Mr H O Forbes had exhibited a Malay cat to the Liverpool Biological Society and showed the cause of the knotting to be the development of wedge-shaped cartilages between the tail vertebrae. Forbes wrote "My remarks referred to the interest I had in exhibiting the creature's skin from the occurrence in the East of what I had noted as extremely common in the cats of Portugal when I lived there about 1876. The kink, I was told was then believed to have become hereditary, from a custom long practised by the Portuguese of pinching or breaking the tails of the new-born kittens, and it would be of special interest if it could be established that the kink in the Malayan cats' tails had been communicated to them through those imported by the early Portuguese into the East. If I can trust my memory the tail of this cat, though short and kinked had the full number of vertebrae, some of them reduced and wedge shaped." Brooke commented that no amount of tail-pinching would cause the trait to become hereditary and that the trait had been present in the Malay cat since at least 1783.

The general type of the Malay Cat reported in the Malaysian peninsula between 1881 and the 1930s, described by HC Brooke and others, and found throughout Malaysia is represented on today's show-bench by the Japanese Bobtail. The colour photo here is of a cat at Lake Chini, near Kuantan, Malaysia. Bobtailed cats in all colours, and with varying degrees of tail-kink, can be found throughout Malaysia and Singapore.

At the Dog and Cat Show at Devizes (reported in the Western Daily Press, 23rd July 1908 and the Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 25th July 1908) the exhibits were confined to a radius of six miles of Devizes and the cats were judged by the well-known Mr G. H. Billett. In short-haired cats, the first prize was withheld and second went to Mr Henry Martin for his Malay cat.

Cat Gossip 21 November 1928: The Toronto Cat Show Catalogue contained several classes strange to us: One for Malayan Blue (one entry, and that absent).

Cat Gossip 19 December 1928: We believe Miss Lowndes will show her Malay Cat at Croydon. It is a very very long time since one has been seen in England, and we suppose no more ever will be seen, thanks to Granny Government, to whose score we fear much slaughter of ship’s cats will soon be attributable.