LOST BREEDS - BRISTOL

Quite how the Bristol name got attached to a hybrid breed is unknown, because in April 1972 the developing breed was described in the now defunct American publication “Cats Magazine.” Possibly some wild blood was introduced between 1972 and the 1980s. Here is the description in full in the words of the breed’s originator.

DEVELOPING BREED – THE BRISTOL (by Patricia Elliott)

The origins of the new breed which we call the Bristol Cat are rooted in a nondescript, many-colored cat who was adopted by a United States Army captain and his family during a stay in Australia. The cat (whose name I do not know) was so much loved by this family that they decided to bring her back when they returned to the United States. What they did not know was that she was bred before they left Australia. Some six weeks after she arrived in America she gave birth to two kittens - a little female as nondescript as her mother and a fine black male who was kept by the family. The little female was wanted by no-one and was destined for the animal shelter. Since we place many cats and kittens in homes, she was brought to our Havenwood Cattery where she stayed for many months. No one seemed to want her.

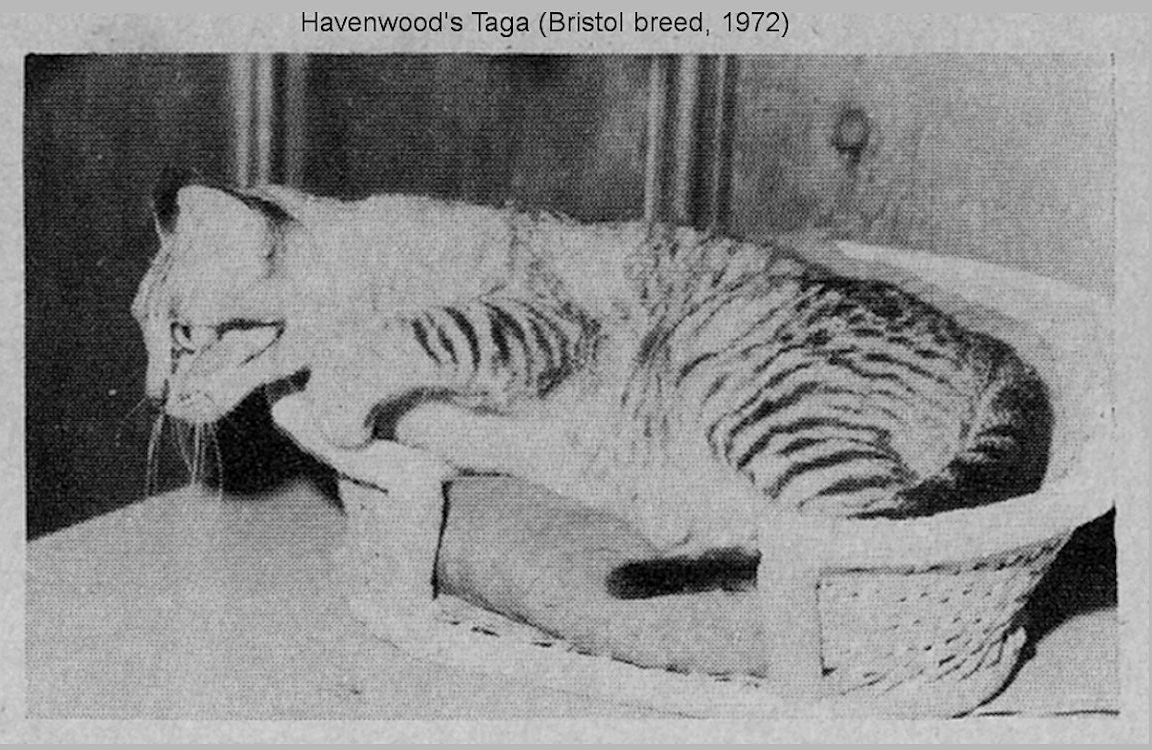

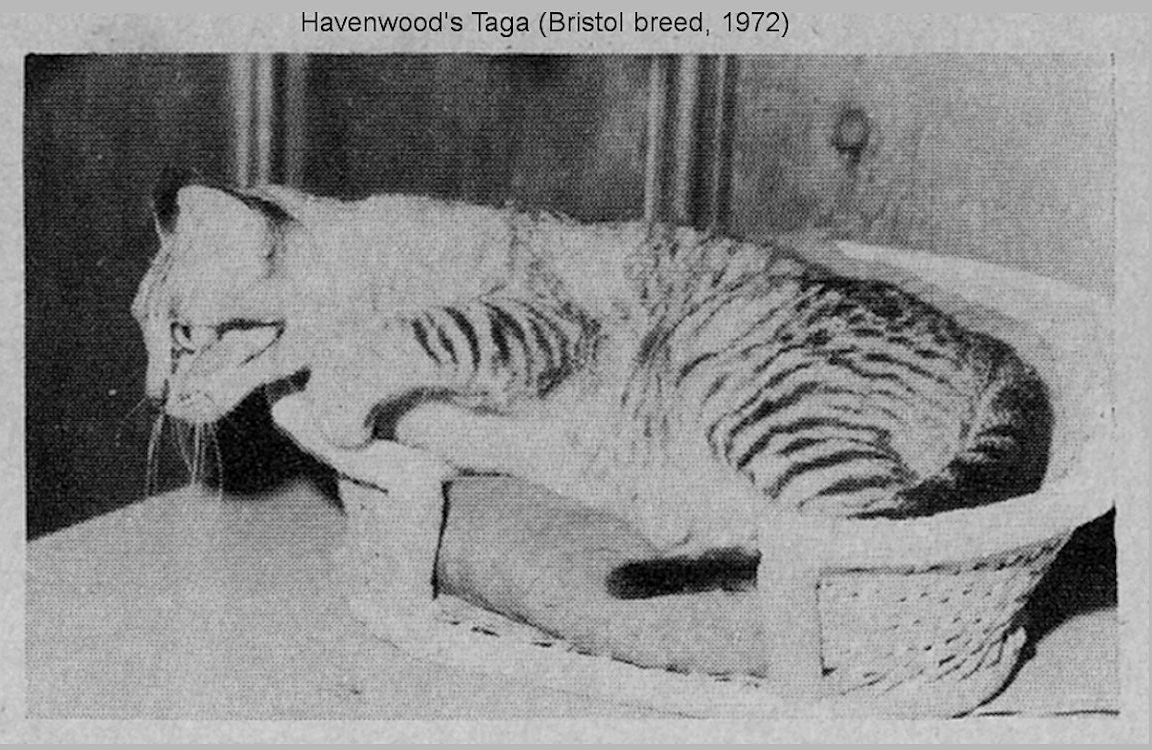

Merry Mary, as we came to call her, was sweet, lovable, remarkably intelligent and completely ugly. Her status as "unwanted” and her sunny disposition made us accept her as a "house cat’’ - a very special position around Havenwood. We found it easy to overlook her long lean oddly colored, striped and ticked body, her skinny, blunt-tipped tail, her unusually large wide-spaced ears when we looked into her clear, brilliant hazel eyes, and when she beguiled us with her winning manners and capacity to learn "play games. Later, when Merry Mary grew up and informed us she wanted to become a mother we mated her with a Burmese stud from the cattery, hoping in this manner to improve the physical appearance of her kittens and thus be able to find suitable homes for them. We intended to have her spayed after this one litter. However, the unusual-ness and beauty of many of the kittens from this litter caused us to subsequently breed her to another Burmese stud. It is out of these two breedings that the basic Bristol stock was derived. Since we have no idea of Merry Mary’s background, we cannot guess as to what breeds she owes her own characteristics.

The kittens from the original breedings have been bred back to both Chocolate- and Sealpoint Siamese to obtain the confirmation and color desired in the new breed. The line has now bred true for the past six generations. Bristol kittens are small replicas of the adult except that the deep chocolate color of the stripes and blotch are not achieved until the cat is about a year old. Eye color usually develops by about four months.

Perhaps the most enticing aspects of the Bristol are their pleasing disposition and truly remarkable intelligence. They are "people cats.” They exert themselves to please you and to gain your approval. Yet, they are not "lap” cats. Courageous and intelligent they gain your attention, your admiration and love. Their smooth chunky bodies and shining coats with lines and spots of deep chocolate on fawn remind one of a jungle cat, a domesticated jungle cat with a happy disposition!

No Bristols are yet available for purchase. However, many have been leased to selected families. More leasing will occur now that the breed is fairly well set and more kittens are available. Havenwood’s Diablo, Merry Mary’s grandson is the only Bristol who has been shown so far. He has consistently placed best or second best in AOV and Experimental Breed classes in California, Arizona and Nevada cat shows. This coming season several new Bristols will make their debut on the show scene.

Merry Mary is now a great-great-great-great grandmother. She has been spayed and spends most of her time supervising the training of her descendants. She is a “house cat.” The nursery is upstairs in the house. This is where she may usually be found, playing with the babies - licking them, teaching them tricks and games.

[Note: This sounds a little bit like the Australian Spotted Mist in its combination of Australian domestic cat and Burmese.]

Through correspondence, I found that a female Bristol called Pandora was exhibited at an ACFA show in Ventura in 1971/72; she was a spotted charcoal colour (which sounds similar to an Egyptian Mau colour).

The Bristol Cat Proposed Standard

Base color to be fawn with gray overtones fading to fawn on belly. Markings to be bittersweet chocolate on head, legs and tail, warmer chocolate color. All markings to be broken.

Medium massive body - overall impression to be that of a powerful cat - a domesticated jungle cat. Neck to be medium length and thick - again powerful. Chest broad and powerful. Head to be medium massive, but not to be short and cobby. Muzzle should be medium' length, with a firm jaw and chin. Chin and nose to meet in a straight line. Whiskers break desirable. Boning of the cat to be medium heavy.

Legs to be medium in length. Boning of legs to be in proportion to balance of body. Tail to be medium length and thickness. Tapering slightly from base to rounded tip.

Ears to be almost as broad at base as at tip. Tip is to be rounded and set slightly forward. Thumb print desirable.

Color of the eyes to be sea-green. Eyes to be forward in head, oval in shape with slight bias toward ears.

Stands in crouched position as in jungle cat about to strike.

One of my correspondents had a female Bristol, Pandora, for a few days in 1970/71 (relying on memory) to exhibit the cat at an ACFA show in Ventura, California, on behalf of the owner. She was larger than an ordinary domestic cat and charcoal with black spots. Pandora was the charcoal colour. The breeder was based in Simi Valley, California, and also had Burmese and Siamese.

Bristol "Hybrid" Breed

The hybrid Bristol breed was being developed in Texas during the 1980s using a small South American wild cat and domestic cats. As a breed, the rosetted Bristol predated the Bengal breed, but unlike the Bengal, it died out due to infertility problems. The wild parent was most likely the Margay, although the similar-looking Ocelot has also produced offspring when mated to a domestic cat. While the Bristol of the 1970s was a chocolate-marked domestic cat, breed books and articles of the 1980s describe the Bristol as a spotted cat or a hybrid. The existence of the breed was never very widely known; they were mentioned in passing in probably only one breed book (late 1980s) and the one person I spoke to who had seen a living Bristol cat described them as having black rosettes on an orange background.

Gene Ducote (Gogees) originally researched the “Bristol Bengals.” In the early history of Bengals, the gene pool comprised bloodlines derived from the 2 daughters of a single Leopard Cat. This meant numerous brother/sister matings were made in order to achieve the desired appearance, but at the risk of loss of health and stamina (inbreeding depression). Breeders were always looking out suitable outcrosses, but wanted to avoid the Egyptian Mau as it had many characteristics that were not desirable in Bengals.

Von Pilcher, an early and very reputable Bengal breeder, visited the residence to learn more about the cats. The cats in this cattery were not very fertile. The 10 cats there produced, on average, only 2 litters per year. The most interesting cat, from the Bengal perspective, was an elderly male called Cajun who was supposedly the sire of this colony of Bristol cats. Cajun had rosettes very similar to those of new world spotted cats (ocelot, margay etc) and a very white ground colour on his chest and belly, along with rounded ears, and a voice similar to that of an ocelot. His pattern, colour, head structure, and voice were very definitely non-domestic in origin. The other cats in the colony were less striking, but their behaviour resembled that of hybrid cats and some of them had the unusual smoky charcoal colour that was already known to occur in F1 and F2 Bengals, but which was not found in pure domestic cats (now known as “charcoal” pattern and believed due to an Asian Leopard cat variant of the agouti gene).

Although the documented history of the Bristol cats was unproven, Pilcher was certain they were hybrid cats of some kind. Cajun and the other cats had features known only to exist in three species of new world spotted cats: the ocelot, the margay (aka tree ocelot), and the oncilla (Tiger Cat). Dr. Solveig Pfleuger later saw the potential for use of the Bristols in the development of the Bengal breed, as they had many of the qualities sought after by breeds: large bones, rosetted coats, and the desirable head structure. Based on his appearance, Cajun was believed to be a hybrid with one of those species, margay being the most likely. Further inquiries unearthed photos of a wild cat believed to have been bred to domestics, to produce the Bristols. The photos showed an ocelot-looking cat, mating with a domestic shorthair cat.

In Autumn 1988, Von Pilcher photographed Cajun, who was then more than 13 years old. The breeders of the Bristol cats claimed that Cajun had absolutely no wild blood. He had allegedly sired a number of litters, and they claimed that all Bristol cats were directs descendants of Cajun. However, none of the other Bristol cats had rosettes or a pattern alignment like Cajun, and none looked so strikingly wild. This casts some doubt on Cajun’s claim to paternity. Cajun himself had a pleasant temperament, but the other Bristol cats seemed much less friendly (at least to Pilcher) and their temperaments were similar to known hybrid cats. This temperament difference makes me think that Cajun was an F1 Safari cat (Geoffroy’[s cat hybrid).

The breeders also said that Cajun was originally owned by a friend and had been born in either Great Britain or Australia, but they did not know his exact background and they were lucky to get one or two litters a year. If Cajun had come from either of those countries, a lot of documentation would have been required for a wildcat or wildcat hybrid. This would explain the claim of “absolutely no wild blood” - such a claim, however false, would have been necessary in order to export him from one country and into another as a domestic pet. Had he been listed as wither a wildcat or a hybrid, he would be subject to import and export permits.

While exhibiting Bengals at the 1988 TICA semi-annual meeting in Brownsville, Texas, Pilcher met a man from Matamoros, Mexico who had bred F1 Bengals in the 1970's. He claimed that he had loaned two F1 female Bengals to the person who now owned Cajun and who was breeding Bristol Cats. Apparently the Bristol breeder was already breeding exotic cats and/or hybrids.

In 1991, Solveig Pflueger, TICA's geneticist, heard of some cats housed at a private residence in Texas. These were registered with TICA as "Bristol Cats" - a breed believed to be extinct through infertility. This colony was, of course, Cajun and his ageing harem. Although described as the sire of the colony, the sterility of F1, F2 and (usually) F3 males, meant Cajun should not have been able to sire offspring at all. It's not clear whether Cajun was siring any offspring or whether his female relatives were being outcrossed, and to what. In addition, most of the Bristol females found were beyond breeding age.

Only two Bristol females were young enough to be used in breeding and these were placed in Bengal breeding programmes; one with Gogees (Gene Ducote) and the other (Sugarfoot) with Belltown (Karen Austin). The Gogees female never produced any offspring. The Belltown female (Sugarfoot) produced several Bengal/Bristol litters and one of her offspring was incorporated into the Gogees line. The Bengal cats carrying Bristol blood inherited a more robust type, small ears and good rosetting.

Many generations later – and with proper management - the cats derived from that Bristol/Bengal cross have no fertility problems, but did dramatically influence the Bengal breed as well as adding genetic diversity. Many breeders now have lines that contain Bristol blood. Others argue that there are no South American wild cat species able to reproduce with domestic cats. DNA tests may determine the identity of the Bristol's wild ancestor from genetic markers.

In the 1980s there was considerable interest in hybrids. The Safari had already been bred and the Bengal was about to take the cat fancy by storm. How far back interest went in Margay or ocelot hybrids isn't known, but in the Long Island Ocelot Club Newsletter (LIOC) of Sept 1962, Mr and Mrs Tom MacBean wrote "Incidentally, I know of a cross-breeding of a margay with a domestic cat which I think is rather interesting, This was accomplished accidentally by the arrival of a male margay on a farm belonging to my friend here in Puerto Vallarta (Mexico) who had several cats keeping down the rat population. The margay mated with one of the females: two of the kittens had all the margay markings and one looked, as my friend said, most peculiar. "

While the Bristol hybrid breed has been lost, some of the genes have been preserved in the Bengal breed. South American wildcat x domestic hybrids seem to have poor fertility, even among females, and this has also affected Oncilla hybrids and Geoffroy’s Cat hybrids (Safari) for reasons explained below.

So what do we know? To expert eyes, the Bristols were obvious hybrids even if any of them had been exported/imported with papers claiming them to have no wild blood. The breeders had previously owned F1 Bengals. Cajun had features found only in ocelots, margays and oncillas. It seems unlikely that he sired the other Bristol cat litters because F1-F3 hybrid males are sterile, though he may have been an extremely rare exception. Domestic cats have 38 chromosomes while ocelots, margays, oncillas and Geoffrey's cats have 36 chromosomes. F1 hybrids have 37 chromosomes. We know from the Safari cat (Geoffroy’s cat hybrid) that the females can be fertile, but the males are sterile F1 Safari females have produced F2 offspring when bred to domestic cats but no breeder has reported an F3 generation of Safari cats.

Pilcher was aware of Maria Falkena-Rohrle’s oncilla/domestic hybrid females bred in the Netherlands in 1966, but was unaware of any hybrids between domestic cats and either margays or ocelots. The Dutch oncilla hybrids apparently never reproduced, and I know of a single case of an ocelot/domestic hybridisation (female ocelot, Bengal male). Pilcher suggested that the Bristol might be the result of previous oncilla/domestic hybridizations (which I doubt) and that Cajun was not actually the sire of the Bristol cats.

Reason for loss: infertility and inbreeding