DO CATS HAVE EMOTIONS?

"Emotion" is the term we use for feelings, some of which are instinctive and some of which are learned from those around us as we conform to society's expectations and norms. Human emotions range from "primitive" feelings such as disgust, rage, fear and lust to "complex" emotions compassion and jealousy.

Recent studies, especially in fields such as neuropsychology, show that the more "primitive" or basic emotions have a physiological basis and may be caused by chemical stimuli (such as sexual attractant scents called pheromones) or visual stimuli. Basic emotions appear to cause chemical changes in the body in response to a stimulus.

This article looks at feline feelings. In places it compares or contrasts human and feline responses or makes references to other animals for illustrative purposes.

TWO POLARISED VIEWS

Do cats (and other higher animals) have feelings? Can they respond emotionally?

According to many pet owners, the answer is "yes". Cats display a range of feelings including pleasure, frustration and affection. Other feline behaviour is attributed to jealousy, frustration and even vengefulness. Owners base their answer on observation of feline behaviour, but without an understanding of what makes a cat tick, they risk crediting a cat with emotions it does not feel as well as recognising genuine feline emotions. Owners who veer too far into the "Did my ickle-wickle fluffy-wuffikins miss his mummy then?" approach may not understand (or not want to accept) that a cat's emotions evolved to suit very different situations to our own.

Cats and humans are built much the same way and share many of the senses - sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch - as well as having additional "senses" which are adaptations to our particular environments and lifestyles (e.g. the Flehmen taste-smell reaction in cats). Though humans have better vision, cats have better smell, taste and hearing. Like us, cats feel heat, cold, pain and other physical sensations. Physical stimuli may lead to physiological responses, some of which are termed emotions. If humans and cats have similar responses to, for example, the smell of enticing food, they may share certain emotions e.g. happiness at the prospect of a satisfying meal.

According to many scientists, however, the answer is "no". They argue that humans like to anthropomorphise (attribute human qualities to non-human animals) and regard pets as surrogate children. We interpret their instinctive behaviours according to our own wide range of emotions. We credit them with feelings they do not have. Some scientists deny that animals, including cats and dogs, are anything more than flesh-and-blood "machines" programmed for survival and reproduction. Others, such as pet behaviourists, credit animals with some degree of emotional response and a limited range of emotions (limited in comparison to humans, that is).

Many researchers' scepticism is fuelled by their professional aversion to anthropomorphism, but others have a more sinister motive. Those who deny animals any feelings at all may do so in order to justify animal experiments which others consider inhumane. This denial of animal emotions allows them to conduct experiments with little regard for their subjects' physical or mental wellbeing. The denial of animal emotions is their own hidden agenda rather than a conclusion based on study of behaviour.

Some religions teach that man is superior to animals and, by extension, animals do not have feeling. Some cultures do not recognise animals as thinking, feeling entities, for example the Chinese term for animal equates to "moving thing" and animals in food markets are treated as though they are no more than unfeeling, moving, vocalising vegetables. Politicians and those opposed to "animal rights" believe that according animals emotions would accord them rights (possibly rights equal to humans), changing the whole human/animal relationship and making pet-keeping, farming, hunting and experimentation unacceptable (many people already argue that hunting and experimentation are unacceptable on grounds of unnecessary cruelty). They argue that humans would be reduced to animal status with all that entails: culling, enforced sterilisation, selective breeding etc and pretty soon the word "Nazi" gets bandied about (ironically Hitler banned hunting).

Are either of these polarised views correct or do cats also share certain emotions, perhaps a limited subset of the emotions we feel? To find out, we must observe our own and our cats' responses to situations and analyse what an emotion is.

THE EMOTIONAL BRAIN

Charles Darwin concluded that animals do indeed have emotions. He went on to explore the extent of animal emotions and found there to be emotional and cognitive continuity between humans and animals i.e. there are not enormous gaps between animals, but rather a continuous range from unintelligent, unemotional "primitive" creatures through to highly emotional and intelligent humans. Where there were gaps, these were differences in degree rather than differences in the kinds of emotions. While Darwin accorded animals varying degrees of emotion, many scientists have avoided the issue of animal emotions by putting quote marks around words such as "nervous" or "fearful". This indicated that the animals acted as if they felt those emotions, but they did not actually have those emotions and the attribution of emotions was therefore anthropomorphic on the part of the scientific observer, hence the quote marks.

In order to understand emotions, scientists have studied how emotions are formed, and how they relate to the rest of the body and to the outside world. To do this, they have looked at how the brain works, often by looking at how the individual brain cells are linked together and how they interact and by looking at what happens when parts of the brain are deliberately or accidentally damaged. The brain contains neurons (nerve cells) which communicate across synapses. The communication takes the form of electrical impulses from one end of a nerve cell to another, and chemicals across synapses between the nerve cells. By measuring electrical impulses and levels of certain chemicals, and by interfering with these, researchers investigate how the brain works. Electrodes placed in certain locations in the brain to can be used to trigger specific emotions. Continual stimulation of part of the amygdala to induce terror eventually results in the animal's death.

These methods are invasive and stressful to the animal (which ends up terminally damaged in the course of experimentation or is killed when no longer required) - little wonder scientists thought animals could not feel happiness. Even after death, the animal's brain could be dissected or sliced and stained for microscopy to see whether certain emotions (such as prolonged terror) caused permanent changes in the brain. Other methods look at how the brain operates as a whole, viewing it in action rather than dissecting a dead brain. Brainwaves can be measured using electroencephalographs (EEG) and scalp electrodes; there are other techniques such as MRI scans (magnetic resonance imaging), CAT scans (computer-assisted tomography) and PET scans (positron-emission tomography). Some of these can be used when the person or animal is in its natural environment.

Psycho-pharmacologists use medication to study the changes in animal behaviour. The test subjects are injected with drugs and their behavioural and emotional changes are measured. Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is linked to both information processing and to emotion; chemicals that interfere with REM sleep lead to increased irritability and anger (and ultimately in death). Not all tests are conducted for the express purpose of researching animal behaviour/emotions - findings sometimes fall out of tests where animals are used to model the effect of drugs on humans.

Behaviour geneticists have selectively bred or genetically modified animals to find out which genes are associated with which emotions and whether how those genes (and their effects) are inherited and can be manipulated. As a result, there are laboratory strains of laid back mice and highly strung mice. The same can be seen in cats - from laid back Ragdolls and placid Persians, through to "hyper" Siamese. Geneticists have further investigated how emotions are affected when certain bodily characteristics are changed. It turns out that emotions involve the interaction of sensory organs, nervous system and other parts of the body.

In experimental psychology, there are 3 main schools of thought regarding emotions. The categorical approach assumes that certain emotions (fear, joy etc) arise from inside the brain and can be measured through biological changes. The social-constructivist approach focuses on how animals use emotions to communicate or relate to other animals. The componential approach considers emotions to be comprised of rewards and learning.

Studies, in fields as distant as ethology (study of behaviour) and neurobiology, support the argument in favour of animal emotions. Even the most sceptical scientists agree that many creatures experience fear. This is because fear is considered a simple instinctive feeling that requires no conscious thought. Hard-wired into the brain, fear is essential for escaping from predators and tackling other threats. Fear underlies the fight or flight response as can be seen when some young birds freeze at the sight of a hawk-shaped silhouette overhead, but not at the sight of a pigeon-shaped silhouette, even if they have never seen a real hawk. Fear also raises the heart-rate and blood-pressure.

Fear is hard-wired and requires no conscious thought, but the existence of more complex animal emotions that involve mental processing is harder to demonstrate. Because complex feelings are intangible and hard to study under laboratory conditions, many researchers regarded the field of studying emotions as unrewarding. Modern, media-friendly ("How the brain works!") disciplines of neuroscience and neuropsychology have changed this. Scientists also recognise the importance of field observations, as long s those observations are recorded carefully, impartially and there are enough observations.

One of the most obvious animal emotions is pleasure. It is evident when your cat snuggles up purring and when it plays. Although play is an important part of learning and honing life skills in youngsters, it is quite obviously also fun otherwise adult cats wouldn't bother playing. There is some evidence that playing, or at least the physical exertion aspect of play, releases "feel-good" hormones in the brain, giving a sense of wellbeing. When rats play, their brains release dopamine, a neurochemical associated with pleasure and excitement. When a rat anticipates a play session, dopamine is released, making it active, vocal and excited (the effect of this can be seen by dosing rats with dopamine-blockers). Happy rats also produce opiates, another feel-good neurochemical.

Grief has also been observed in many wild species following the death of a mate, parent, offspring or pack-mate. Feline grief at the death of a long-term human or feline companion can include severe mental disturbance. Grief varies according to the individuals and some cats show little grief while others can be deeply traumatised. This variability leads some scientists to insist that observation of grief in cats is anthropomorphism on the part of the owner. Such scientists forget, or ignore, that fact that humans are equally variable in how they express grief.

In humans, the hormone oxytocin, is associated with sexual activity and maternal bonding. Experiments with monogamous prairie voles shows it affects attachment among animals. Oxytocin injections trigger mate choosing behaviour in female prairie voles, while blocking oxytocin prevents those females from choosing a partner at all. Oxytocin causes prairie voles to "fall in love" (or more accurately, to "fall in lust").

Emotions are therefore accompanied by biochemical changes in the brain. Fear is accompanied by the production of brain chemicals that cause alertness and readiness to flee; pleasure triggers the release of "feel-good" brain chemicals. Long-term production of stress hormones can damage the hippocampus (the part of the brain central to learning and memory) and experiments show that stressed-out mothers have more problems producing healthy offspring. Other emotions are not so biologically clear-cut, for example "shame" and "embarrassment" are "social emotions" - the result of attaching emotional meanings to, respectively, unacceptable or inappropriate behaviours. While emotions such as fear and pleasure are common to humans and animals, researchers cannot agree on how great a role social emotions play in non-human animals.

The limbic system is the part of the brain associated with many emotions; experiments show it is active when an animal or person is frustrated while damage to that area produces aggressive-impulsive behaviour. In evolutionary terms, the limbic system is an ancient part of the brain and is not exclusive to humans: animals have emotions, but only humans rationalise those emotions and agonise over their feelings.

The amygdala, an almond-shaped structure in the centre of the brain, is closely linked to fear. Brain-imaging studies in humans show that the amygdala is activated when the person experiences fear. Stimulating a certain part of the amygdala with an electrode induces a state of intense fear. Animals, including ourselves, whose amygdalas are damaged do not show normal responses to danger and seem unable to be afraid when placed in dangerous situations. The amygdala is implicated in other emotions as well.

The question of whether animals have emotions is often confused with whether or not animals are conscious. Though cats have some self-awareness, they do not have consciousness in the same way as humans. Cats will play with their mirror reflections even though they know that there is no cat inside the mirror, however, cats do not recognise the mirror images as being themselves. Human language also confuses the issues of "emotion" and "consciousness"; often when we talk about how we feel it is unclear whether we are referring to our emotional state or to self-awareness.

IN THE LAB AND IN THE FIELD

Laboratory animals and animals in a wild (or domestic) environment behave differently. They have different surroundings. Their interaction with other animals and with humans are very different. Laboratory animals may have little opportunity for social contact with others or their responses may have been impaired through experimentation or genetics . Some animals are selectively bred for specific traits and they may not exhibit "typical" or representative behaviour.

Emotions cannot exist in a vacuum - they are (in part) a response to external factors. Many laboratory animals show aberrant behaviour (e.g. self-mutilation, faeces-eating) due to their sterile environment. These are signs of stress and depression, but are often not termed as such for reasons mentioned earlier. It is recognised that animals suffer in these conditions, for example animals in some of the worst zoos show behavioural/emotional problems: repetitive pacing/rocking and psychological problems.

Animals respond to their environment. It is not possible to accurately assess the normal psychological responses of a creature which is treated as an unfeeling biological machine and kept in an unstimulating or highly abnormal environment. This is just as dangerous as anthropomorphising animals in a cutesy fashion. Animal rights/animal welfare campaigners are often accused of inappropriately attributing emotions to animals. To recognise animal emotions would cause problems for experimental laboratories who do not wish to make potentially expensive changes to the environment in which their disposable living "tools" are stored.

Animal experimentation scientists argue that animals are not fully capable of suffering because they cannot anticipate future events. While cats cannot anticipate irregular events or far future events in the way that we can, cats have an excellent sense of time and can anticipate regular and near future events such as the owner's return from work at a similar time each day. Ironically, the feline sense of time and ability to anticipate regular events (such as food being delivered) has been tested in laboratory experiments. Cats are equally capable of anticipating unpleasant regular events, such as daily experimental routines, and display fear or aggression when approached by the experimenter.

Even in the less invasive techniques, scientific methods do not like to have too many variables. Scientists prefer to measure one variable at a time. Unlike inanimate properties such as temperature or pressure which are individually controllable in laboratory conditions, emotions cannot be isolated. Environmental factors must be manipulated in order to produce an emotional change. Individuals may react in different ways to the same environmental change. This makes the study of emotions in laboratory conditions frustrating. Many scientists claim it is impossible to prove animals have emotions using standard scientific methods: repeatable observations that can be manipulated in controlled experiments. Hence they conclude that animal emotions must not exist. This is a drawback of scientific methods. Many humans do not display typical emotions in lab conditions due to the unnatural methods use and the invasive methods, yet no-one denies that humans have emotions.

To properly assess animal emotions, scientists and animal behaviourists must study animals in the field or in the home. The environment can be manipulated, but cannot be controlled absolutely. What is important is how the animal behaves in its own environment and how it interacts with its environment and with others. The observer must interpret the behaviour and decide whether the subject is fearful, apprehensive, angry etc. To ensure a consistent approach, the animal's behaviour may classified according to a shortlist of likely emotions or on a sliding scale for a particular attribute e.g. fearfulness or curiousness. Similar methods are used in assessing the behaviour of very young children.

A growing number of farmers, particularly those in the organic sector, are recognising the need for animals to express instinctive behaviours. Although some stress is unavoidable in farming, animals which suffer minimal stress may be more productive, have better immune systems, be less prone to disease and have a lower mortality (wastage) rate. This is even more apparent in zoos and wildlife parks where environmental enrichment and encouragement of natural behaviour has led to "happier" (less stressed) animals more likely to breed successfully in captivity.

Recognition that animals have emotions can be taken too far and is prone to misinterpretation. The human tendency to project human-style thoughts, motivations and desires into animals can result in pets being treated as small furry humans who ought to love us and show gratitude. While our cats probably do love us and feel gratitude (in the feline sense of love and gratitude) they may suffer the consequences of our unrealistic expectations because they don't show gratitude in a human sense or in sufficient quantities (based on the amount a human would show) - they display gratitude by being happy cats, not by fawning.

Pet cats have traits that humans find desirable: friendliness, playfulness, cuteness and dependence. These are retained juvenile (kittenhood) characteristics, since wild and feral adult cats are wary, independent and more solitary in nature. Despite selective breeding for physical traits and friendliness to humans, cats are behaviourally the same as their wild ancestors, but they have adapted their innate behaviours to suit a domestic situation.

Owners rely on feline behaviour and body language for clues about its emotional state. In this respect, dogs are considered to be more expressive than cats. Dogs evolved elaborate systems for social communication in a pack; the human household is a surrogate pack, therefore dogs communicate with owners as they would other dogs. Dogs transfer their dog-to-dog social behaviours into dog-to-human communication. Many dog owners misinterpret the submissive or juvenile behaviour of a lower-ranking dog (towards its higher ranking owner) as affection.

Cats are more solitary than dogs and have looser social structures (most often colonies centred around food sources). Like dogs they apply this to the household, but the feline social system is not based on pack hierarchies hence cats appear more aloof than dogs. Cats don't display the same range of submissive or appeasement behaviours because they don't live in hierarchical packs. Feline affection takes the form of rubbing, purring, head-butting, lap-sitting and interaction with the owner.

It's easy for humans to misunderstand feline behaviours and intentions. Urinating on the bed is often thought to be "anger", "spite" or "vengeance" to punish an owner who has gone away for a few days. The same is believed if a cat sprays the owner's suitcase when the owner returns from holiday. The suitcase carries lots of new smells, possibly smells of other animals, and the cat is simply over-spraying those smells with its own scent to reassert its ownership of suitcase. Some cats become nervous when the owner is away; urinating on the bed or the owner's favourite chair mixes the cat's scent with the owner's scents and is the cat's attempt to create a combined smell to deter possible intruders who might take advantage of the owner's absence (regardless of whether there is a cat flap or not). This is one reason the cat needs to meet a pet-sitter before the owner goes on holiday - otherwise it may regard the pet-sitter as a threat.

The predatory instinct is hard-wired into the feline brain (electrical stimulation of a particular brain region triggers pouncing behaviour). Pet cats sometimes take prey home, either as a food gift for its surrogate family (in this respect the cat is relating to owners in the way a mother relates to kittens) or because the house is its den and hence a place to eat in safety and at leisure.

THE FOUR (OR SIX) BASIC BEHAVIOURS

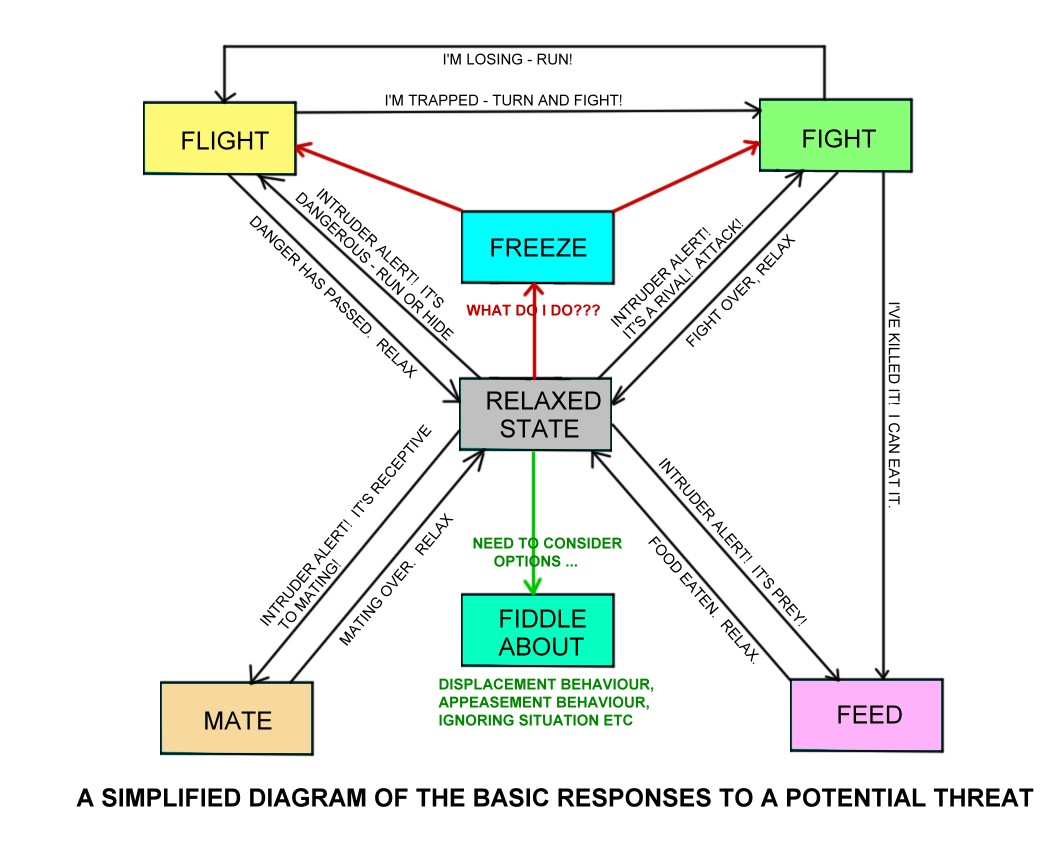

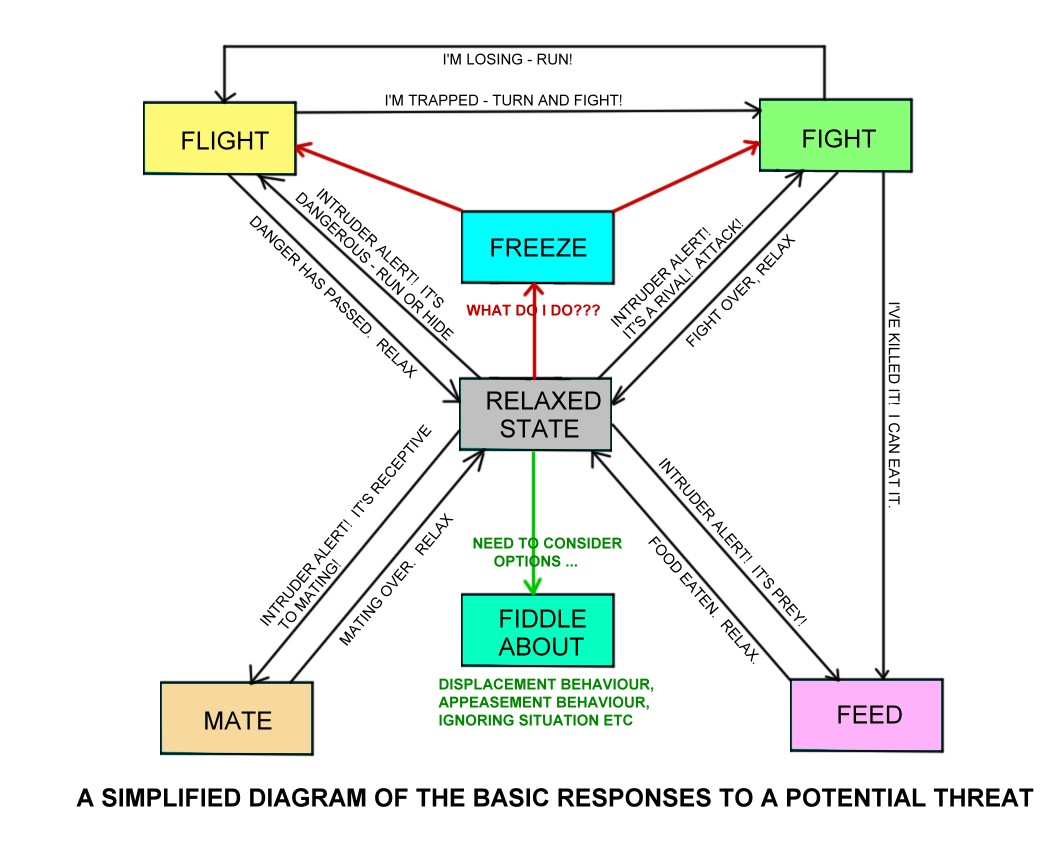

There is much argument as to whether animals experience emotions or are merely showing behavioural changes in response to their environment. Animal behaviourists recognise four basic behaviours which are found in most animals, though it can be argues that there are six basic behaviours. "The Four Fs" are the basic instinctive responses which aid survival.

Fight

Flight (or hide)

Feed (predation or foraging)

F*** (mate or reproduce)

Note: the crudity helps psychologists with the mnemonic; the polite version is fight, flight, feed, breed.

Fight-or-Flight is often preceded by the "Freeze" or "Startle reaction". In some situations, the threat goes away if the cat freezes e.g. the cat's camouflage will save it as sight-oriented predators are triggered by motion.

Then there is "Fiddle about" (so-called because researchers needed another "F"!). This encompasses appeasement behaviour, displacement behaviour, posturing or simply ignoring the situation. "Fiddle about" might happen because the cat has already learned that there is no need to run away or fight in a particular situation. Or it may occur because a more appropriate response is somehow being thwarted. Cats that don't particularly want to fight with each other (why risk debilitating injuring?) often posture until one or other of them backs down. That's fiddling about.

The hormone adrenaline is a key player in these reactions. On encountering someone or something, the most immediate instinct is "Do I run away from it or stay and fight it?". This is a self-preservation reaction. If neither of those reactions is triggered, the next instinct is "Do I eat it? Do I mate with it?". If none of the 4 Fs apply the animal may exhibit curiosity or simply ignores the stimulus as irrelevant.

These behaviours can be modified through learning or conditioning. Cats will often ignore one another to avoid conflict. A cat raised alongside a rabbit may no longer have a "feed" response to that particular rabbit or to all rabbits. Pavlov demonstrated conditioning (learning) in his famous experiments where dogs were taught to associate a sound with the presentation of food. After a while, the dogs reacted to the sound even when food was not presented.

In humans, and probably in cats, these responses have two parallel routes through the brain. The "quick and dirty" route gives an instinctive, almost instant reaction. The "thinking" route takes slightly longer and modifies the animal's reaction. Learning affects the thinking route. For example most animals will bolt (flight reaction) at a loud noise close by; gundogs and police horses are trained to stand their ground though they may still show instinctive startlement.

Four basic responses are sufficient for primitive animals. Humans, cats, dogs and other more advanced animals need more than four basic instincts if they are to cope with a rich and varied environment. A complex environment requires a greater complexity of response. Emotion contains both innate (hard-wired) and learned (acquired from experience) components. Over a period of time, a cat might modify the innate fight/flight response to an initially threatening situation; for example, instead of fleeing from the vacuum cleaner, it might simply remove itself to a vantage point on a book case.

The study of animal emotions generally defined in terms of an animal's adaptive and integrative functions (types of learning) rather than the physiology of emotions. This looks at how an animal's emotional states interact with its day-to-day functioning. Mental responses, in ourselves and in other animals, do not necessarily follow physiological reactions. For example, fearful rats have measurably higher levels of epinephrine levels; but injecting epinephrine into non-fearful rats does not make them fearful. Therefore there is a mental component involved and emotions are not induced by physiological changes alone.

THE SIX BASIC RESPONSES

What is the role of emotion in an animal's life? In the wild state, all behaviours and emotions improve the individual's chances of surviving and breeding, and therefore improve the chances of the whole species surviving. What we term "love" could be unromantically considered a type of attachment that bonds a breeding pair together (sometimes for the duration of the mating act, sometimes for a longer period), and bonds one or both parents to the offspring until the offspring can survive alone. "Love" therefore improves the survival prospects of the individuals (who look out for each other) and the species.

Animals must adapt to a changing environment - the rate at which they need to adapt might be several lifetimes (in which case adaptation is through genetic variation) or a single lifetime (in which case learning and intelligence are essential). Evolutionary psychology is used to measure emotions that have changed over time and can be used to measure emotions that will help animals to survive in the future. Cats, like us, come into the world pre-equipped with a number of emotions that help them adapt and survive.

In humans, there are 6 basic responses i.e. emotions which are rooted in our physiology (there were initially believed to be just 3 basic responses - fear, sorrow, joy - but recent research in humans has expanded the number to 6). These "primary emotions" involve lower brain stimulation and do not require cognition. They are hard-wired survival mechanisms for a very good reason - if we had to spend time learning these, we might well be killed before perfecting them as skills. These basic responses, or primary emotions, cause an instinctive response in our brains and bodies, not just in our minds. For example, when an object flies towards our faces we duck, even though we haven't identified the object.

These emotions are linked to particular brain areas in humans or to hormonal or chemical responses. They are survival responses to protect us from adverse conditions and to make us seek out favourable conditions. Most are linked to our perception of comfort and discomfort. It is likely that cats have equivalent physiological responses to the same, or similar, stimuli.

|

FEAR |

A self-preservation instinct. Fear leads to alertness, caution and possibly to flight. It prepares the body for flight or defence. Fear is the recognition of a potential danger rather than the instinctive (and possible energy wasting) flight from potential (rather than actual) danger. Fear allows the animal to assess how real or immediate the danger is and to take appropriate action (flight, freeze, hide, disregard etc). |

|

DISGUST |

In the human context, originally this prevented us from eating contaminated food or coming into contact with filth. In modern humans it is also applied to other stimuli (the thought of doing something, an image or a situation). It is an avoidance mechanism. In cats, whose livers are not good at dealing with toxins, the avoidance of stale food is probably caused by a similar mechanism. Cats rely on smell, taste and "disgust" to avoid tainted food. |

|

DESIRE (LUST) |

Associated with the basic mating urge without which we would not breed. Desire is associated with pheromones and body language; and causes chemical reactions in our own bodies when we experience it. It is associated with mate-seeking, assessment of a potential mate's suitability and courtship behaviour rather than just with copulation. |

|

SADNESS |

A form of psychological discomfort experienced in non-ideal situations; it helps us to avoid non-ideal conditions. Humans have a wide range of sadness-emotions varying from grief, transient upsets and some forms of depression (a chemical disturbance in the brain) have symptoms like sadness. Cats exhibit depression in some situations and some cats have been reported as "inconsolable" when a close companion dies. Separation anxiety in cats and dogs may be partly due to the sadness mechanism. |

|

HAPPINESS |

A form of psychological comfort/satisfaction experience. It helps us seek ideal conditions or repeat beneficial behaviours (eating, sex); chemical reactions are involved - feelgood chemicals are released in the brain. In cats it is most often seen as "contentment" and is also evident in cats and kittens during play. Play is a self-fulfilling behaviour which produces "happiness" by release of feelgood chemicals. |

|

ANGER |

A reaction to a non-ideal situation when we intend to fight; chemical reactions occur in the body as part of the fight or flight response. It can also result in displacement activities such as self-mutilation. Cats which are handled against their will exhibit obvious anger. Most vets are familiar with sheer feline fury though it is hard to distinguish "anger" from the "fight" reaction. "fight" is relatively transient; anger (a bad mood) does not pass so quickly (a cross cat will stay angry even when the stimulus is removed). |

The feline sniff-and-sneer reaction is the Flehmen response to "taste-smell" something. A cat has an excellent sense of smell and can detect food which is stale or contains medication. Though the sneer looks like disgust (humans wrinkle their noses when disgusted), it is simply the way the cat's mouth is set to pass scent molecules over the Jacobsen's Organ. After flehming, the will take the appropriate response.

Cats show fear and lust in response to the appropriate sights, sounds and smells, but love requires a degree of abstraction which cats probably do not possess. Lust is the mating urge, love is the emotional baggage which surrounds and tempers that urge in most humans. Humans have a wider range of emotions and the emotions which we share with cats are more refined in the human species.

Physical and emotional pain have been studied in terms of an animal's body language, vocalisation, temperament, depression, locomotion, immobility, and clinical changes in cardiovascular, respiratory, nervous, and muscular systems. Awareness of these factors allows vets to administer pain relief to their patients appropriately. Veterinary procedures are ranked as having minor, moderate or severe effects on animals.

RAGE

The "rage" network is closely connected to centres in the prefrontal cortex that anticipate rewards. The rage and reward circuits turn out to be intimately linked. Experiments in cats have shown that stimulating a cat's reward circuits gives it a feeling of intense pleasure. When the stimulation is withdrawn, the cat bites. This is a response to unfulfilled expectation and is known as the "frustration-aggression hypothesis". This might also explain why some cats lash out when being pleasurably groomed. This is usually explained as an anxiety response, but it is possible that pleasurable sensations overflow into the rage circuits and the cat automatically lashes out.FRUSTRATION

Frustration is what happens when a basic emotion cannot be, or is not, fully expressed. It is generally viewed as an emotion in itself rather than a displacement of the initiating emotion.

The build-up of physiological effects demands some sort of outlet. In territorial animals and birds there may be displacement activities such as shrieking, stamping, tearing vegetation (humans may cry in frustration) etc. These give alternative outlets for pent up energy. Frustration is what we feel when we cannot fully express ourselves or when the situation makes full expression impossible, impractical or unsafe.

For a cat living in a human world there are many frustrations which it resolves as best it can. Many are resolved through modifying other behaviour through the learning or conditioning process. Cats are highly adaptable but they retain many wild instincts which need to be expressed e.g. hunting, territoriality.

Frustration is often associated with a state of agitation or high emotion. Feline frustration is obvious when a cat watching prey from behind a window chatters its teeth. The teeth chattering is a frustrated form of the neck bit the cat would have used to kill the prey. A cat which has lost a fight to another cat may lash out at its owner or may flee from a familiar person. The cat's body is still full of adrenaline and primed for fight or flight. Any approach from even a familiar person may trigger a fear or fight response. Similarly, it may attack other cats in the household. Female cats with a frustrated maternal instinct may abduct and protect another cat's kittens, other small animals or kitten-like inanimate objects such as slippers.

Cats are wild creatures at heart, designed and programmed for outdoor life. In modern indoor cats, an owner must provide a stimulating environment to reduce feline frustration. Playing provides an outlet for predatory behaviour and produces satisfaction in return.

OTHER BASIC EMOTIONS

Secondary emotions involve higher brain responses as they must be evaluated and the appropriate response determined. Secondary emotions are therefore more flexible. There are a number of other basic emotions which are recognised in humans and in cats. These produce physiological responses and are varying degrees of , or combinations of, the six basic emotions. These include (but are not limited to):

|

STRESS |

Stress results from continued unhappiness where there is no escape from the stimulus. It affects the immune system, reducing the immune response. Continued elevation of adrenaline adversely affects other organs. Different animals have different stress levels. Some cats are nervous and more easily stressed than others. |

|

DEPRESSION |

Also a form of continue unhappiness including unhappiness due to pain. The chemical effects in brain can lead to withdrawal to the point where the animal loses the will to live. Depression can override survival instincts. |

|

EUPHORIA |

It is hard to think of euphoria in cats unless you have witnessed the effect of catnip. Not all cats are susceptible to a catnip high, but those that are exhibit a sort of drugged euphoria due to its effect on the brain. |

ABSTRACT AND COMPLEX EMOTIONS

At present, the more abstract emotions are believed to be human only. However, what we define as altruism, relief etc, may be our rationalisation of a emotion or a mixture of one or more basic emotions.

When owners say their cats are jealous, they are trying to rationalise a feline emotion into human terms. Feline "jealousy" may be a response to any number of stimuli - the cat seeking to better its place in the household hierarchy or an opportunist or stronger cat competing for food or attention. The cat does not rationalise it in terms of "I am jealous of the other cat" or "I covet what the other cat has"; its feelings will be more along the line of "I am stronger or fitter than the other cat, I deserve to be dominant cat around here." Cats are not as strictly hierarchical as dogs, but where several cats live in a single household, they will establish a pecking order.

Is kitty really being bloody-minded or mean (in the American sense of mean-spirited, in Britain "mean" means "miserly"!). Is he really sulking or punishing you? If you have been absent, your cat may take a while to become reaccustomed to your presence - your return has altered the hierarchy again and he is not certain of its own position until the owner-cat (a sort of cat-kitten) bond is re-established. Is he punishing you? Very unlikely - that is a human interpretation of the cat's actions. Sulking? That may be as good a description as any - he may avoid interacting with you until the household has settled down into a pattern of behaviour again.

Look at it from the cat's viewpoint:

|

Trigger: |

Owner has returned. |

|

Fight or Flight Response |

|

|

Do I run away? |

No. Unless I am a very nervous cat or my owner has unusual scents about him or makes unusual sounds. |

|

Do I fight? |

No. |

|

Food or Mate Response |

|

|

Do I feed? |

No, my owner is not a food item. |

|

Do I mate with him/her? |

No. I have been neutered and in any case, s/he doesn't smell like a suitable mate for me. |

|

Learned responses |

|

|

My surrogate parent/surrogate littermate has returned |

I will greet enthusiastically with submissive actions (rolling on back) or play actions appropriate to my status as a kitten. |

|

I am curious |

I will investigate and greet him/her. Interpreted as "pleased to see me" by owner. |

|

S/He is no threat, is not food and is not a mate. |

No action is required so I shall do nothing. Interpreted as sulking/punishment by owner. |

AFFECTION

Cats show obvious pleasure in company of a familiar person, often a modified cat/kitten relationship. The presence of a companion/caregiver (surrogate parent) produces happiness (a basic emotion).. In the domestic setting, most cats adopt a kitten role, allowing us to groom them, play with them and provide food and warmth. By demonstrating their happiness (which we term "affection") they reinforce the cat-owner bond and ensure a continued supply of companionship and care.

Mother cats show affection towards their kittens. This is part of maternal care. Male cats have been known to show affection to their mates and towards their own kittens - this is similar to the behaviour of lions towards their own cubs (but not towards unrelated cubs).

There is little doubt that most pet cats enjoy the company of their humans and give affection in return. Those who deny that cats can be affectionate should analyse exactly what it is that makes humans affectionate. The underlying causes of affection are actually very similar!

This leads on to the question of "does my cat love me?". Modern westerners too often associate love with “romantic love,” (the “falling in and out of love” stuff) but that’s just one of many forms of love. The Ancient Greeks had separate words for familial-love, friendship-love/loyalty, romantic desire and the idealised love. Other socieities around the world also distinguish between different types of love. Then there’s maternal love and material love. A whole complex of feelings get bundled up into that single word "love". I think of love as an attachment where I would feel an emptiness or sense of loss if that individual went missing from my life. Love and affection are often confused in the western world. When your cats groom you, or choose to stay close to you, it is their way of showing displaying acceptance, companionship and yes, affection.

GRIEF

Grief is the result of abrupt or unexpected severing of attachment. Cats are aware that a familiar person/cat is absent and may search for that person/cat. It may change an established hierarchy as well as being the absence of a familiar companion. It might not be grief in the human term, but the sudden absence of something familiar is distressing to many cats. Mother cats whose kittens were taken away and destroyed often looked for their kittens for many days, all the while pacing and crying out. As well as the physical pain of engorged mammary glands, the cats displayed mental pain.

The absence of a familiar part of the environment causes sadness. The continued absence of that person or thing can lead to stress. In the context of a bereavement, this stress is termed grief. Humans often have elaborate or ritualised ways of dealing with their grief. Cats may become withdrawn or, at the other extreme, over-attached.

As with affection, humans must analyse exactly what causes and sustains human grief before arguing that animals do not feel a comparable emotion. Grief is a reaction to the sudden absence of something or someone which caused happiness/satisfaction. The major difference is that cats show grief for someone who has been a close companion while humans show grief for a distant relative or at the death of a public figure. Cats simply lack the abstraction (and the memory capacity) that allows humans to grieve for someone we have never met or who has been absent from our life for a prolonged period of time.

I have personal experience of a pair of cats whose owner had died. The cats refused to eat while in the shelter. To reduce stress, they were fostered in a household and the vet prescribed appetite stimulants. One cat recovered but remained withdrawn for a long period of time. The other continued to pine and became critically ill until it had to be euthanized (prolonged fasting results in hepatic lipidosis or fatty liver disease). Its behaviour was so severely affected that the foster carer considered force-feeding unsuitable; the cat had no interest in life. Post mortem showed no sign of disease except for that caused by failure to eat. There is one instance where a streetwise cat was believed to have committed suicide by deliberately walking in front of a truck a few days after the owner had died; however the cat's motives cannot be verified.

Humans have long been believed to be the only creatures that cry in sorrow or grief. There is some evidence that other animals form tears when in physical or emotional distress. Cats may express grief through nightmares (quite possibly a dream of the missing person has been replaced by wakefulness and the abrupt realisation that the person has gone). One of my cats, Sappho, had repeated nightmares after the traumatic death of the owner in the cat's presence. Sappho woke up whimpering and fearful from sleep and required physical reassurance from me. If this happened at night, she actually climbed into bed and hid as far down the bed as possible, crying out (initially at a rate of one vocalisation per second) until her fear and grief subsided.

COMPREHENSION OF DEATH (BEREAVEMENT)

Cat appear to comprehend a state of someone not being alive - body temperature changes, smell changes etc. Whether they make the link between a corpse and someone previously alive is not certain, but many cats stop looking for an absent companion after being shown the body of a deceased companion. Therefore cats probably have some comprehension that something dead cannot become alive again.

The display of grief in cats is due to the absence of someone familiar. In humans it is, in part, due to the realisation that we will never see that person alive again i.e. to our understanding of the permanence of death.

PLEASURE

Pleasure appears to be an abstracted form of happiness/satisfaction which persists after the original stimulus has gone or which is felt in anticipation of an event.

In many contexts, pleasure is a synonym for happiness/satisfaction. Pleasure can also occur through memory and through anticipation.

SENSE OF HUMOR

This is a tricky topic. The "smile" on a cat's face is due to conformation of its muzzle. A cat "smiles" with its eyes and with its tail. Observant owners soon learn to distinguish a cat's "happy face" from its "sad face".

Cats do not tell jokes (certainly not that we know off) but they do engage in clownish behaviour. A cat can suspend its adult behaviour and revert to kitten behaviour .

Scientists used to believe that a cat playing with its own reflection in a mirror or with a TV image is unable to distinguish an image from reality. Many still think that way. Pet cats learn very early on that reflections and TV are "not real". This doesn't stop them making use of them as play objects. Batting a moving object is instinctive. Batting a picture on a TV is a safe outlet for hunting behaviour, but the cat doesn't expect to catch the object (unless it has never encountered the TV before).

Inexperienced cats and kittens expect to find the reflection cat behind the mirror. When the image puffs its tail and hisses (albeit silently) back at them, they may become startled. After a few unsuccessful checks behind the mirror (and the lack of any scent of the "other cat"), they accept the image as a plaything. Even experienced cats will occasionally search behind a mirror or TV in case the pretend prey has emerged from it. It doesn't really expect to find anything, but it is always worthwhile checking just in case!

Suspension of disbelief in this way is sometimes considered to be the feline sense of humour. It is an outlet for predatory behaviour and it results in happiness. Whether it is genuinely humour is debatable.

Some of the play tactics are interpreted as a sense of humour e.g. jumping out of hiding at the owner or onto a cat companion. This is play and is practice of the cat's ambush hunting technique rather than a practical joke. A cat which engages in clownish behaviour has learnt that its behaviour results in a reward from the owner - food, attention, physical contact etc. This reward leads to happiness/satisfaction for the cat, therefore the behaviour is repeated. If it is a sense of humour, it is one which has been conditioned (albeit unwittingly) into the cat.

EMBARRASSMENT

At first this seems like another tricky abstract emotion.

A cat which clumsily falls off a shelf and acts differently according to whether the owner is watching or whether the owner is believed to be out of sight is thought to be showing embarrassment.. Embarrassment in humans is associated with potential loss of face, loss of status or loss of respect (these are all related, but modified by culture and circumstances). The loss of status may be permanent or temporary.

A cat is not only a predator, it is also prey for larger animals. In addition it is programmed to fight other cats for its territory and for mates. If it shows any indication of weakness, it may be challenged by a younger or fitter rival and ousted from its territory. For this reason, many cats hide signs of illness, injury and pain.

A cat which has fallen off a shelf in plain sight will pretend the event has not happened i.e. that it has not shown any weakness. A human may make excuses for why a similar human mishap happened (the ledge was icy or slippery); this is simply a human way of saving face. Cats speak with their bodies and an "embarrassed" cat will most often sit down and wash nonchalantly - cat speak for "nothing has happened"!

JEALOUSY

"The cat will be jealous of the new baby and harm it!" "My cat is jealous of the kitten and keeps urinating on the bed!" "Tiddles sulked and moved next door."

Jealousy and sulking are human emotions. A cat is protective of its territory and defends it. Unless a newcomer is carefully introduced so that it is accepted as a "family member", a territorial fight/flight response is triggered. Few cats respond to a new arrival with enthusiasm. We must understand how a cat views the world about it and to understand how it is responding rather than interpreting feline reactions as human-like emotions.

When a newcomer arrives, the owner's attention is suddenly divided. The cat receives less attention. The newcomer may receive a disproportionate amount of attention. There are new smells and sounds and a bewildering change in routine and environment. Its relationship with the owner changes. Things become unfamiliar or stressful and the cat may become unhappy or depressed.

Urination on the bed (or elsewhere) is an attempt to scent mark territory in an attempt to repel an intruder. By mixing its scent with the owner's scent, the cat is saying "My clan own this territory". When a child gets scratched it is rarely an attack by the cat. Most often the child (who is unable to read cat body language) has made a "threatening" move (grabbing fur, pulling tail) and the cat has responded to the perceived threat. After one or two such encounters the cat usually gives the child a wide berth until the child learns to behave more considerately.

The owner's reaction confuses the cat. The child has molested it. The cat has swatted the child. The child cries. The parent consoles the child and chastises the cat. The child's behaviour is reinforced; the cat's behaviour is punished. In feline terms, the newcomer is ousting the cat from its territory. The "defeated" cat may remove itself from the situation; this is interpreted as sulking or the result of jealousy. Some parents are so over-protective that a curious cat which sniffs a baby is interpreted as a jealous cat about to attack.

With a little consideration for feline behaviour and emotions, introductions can be managed carefully to avoid these cat/human misunderstandings. Cats respond to the situation according to their more limited range of emotions; jealousy and vengefulness are human, not feline, emotions.

SO - DO THEY HAVE FEELINGS?

Cats and other animals have feelings. However their feelings must be interpreted in the context of their own physical needs and their own environment. They have a more limited range of feelings than humans and their reaction to environmental stimuli is different to humans, but they show many responses indicative of emotions.

Although I have used the term "programmed", to reduce cats to little more than pre-programmed machines with a finite set of available reactions would be wrong. Those who deny that cats, or other animals, are entirely lacking in feelings do this to justify their own treatment of animals rather than through any true understanding of those animals. Rather than attribute full human feelings to cats, it is better to understand how cats perceive the world and to adjust our behaviour to accommodate their physical and emotional needs as best we can.