The very early cats would have looked something like this modern day Fossa, a Madagascan mammal related to the Mongoose. This carnivore occupies a similar ecological niche to cats and preys on lemurs and rodents.

PREHISTORIC CATS AND PREHISTORIC CAT-LIKE CREATURES

Although we are familiar with cinema representations of sabre-toothed cats, only a handful of prehistoric big cats exceeded an average weights of 100 kilos and only four or five North American prehistoric big cats (not all are true cats) are in the 100+ kilos category. This means few were longer or taller at the shoulder than a modern leopard or jaguar. Many of the "bigger" prehistoric big cats were compact, muscular animals. Modern big cats are relatively long-legged and lithe in comparison.

Although they are often called "big cats" many of the prehistoric species were not true cats, but were cat-like mammals. South America and Australia were both island continents and lacked placental mammals. The "lions" and "tigers" of those continents were lion-like marsupials, more closely related to kangaroos, wombats and their like. They are known as "cat analogues" as they resembled cats and filled the same ecological niche as cats. Another line of prehistoric cats were the Paleofelids ("ancient cats") that developed in parallel with the true cats and from a common ancestor, but which have left no modern descendants. Finally there are the prehistoric true cats, extinct relatives of modern cats. Why would evolution create creatures very similar in form to cats? It's an example of convergent evolution - there are a limited number of solutions to environmental conditions hence animals that aren't closely related often independently evolve similar traits as they both adapt to similar environments and niches. The cat-like form has evolved at least three times: marsupial lions/tigers, Paleofelids and Neofelids. Sabre-toothed cat-like animals evolved separately four times in evolutionary history: Nimravids, Felids, Creodonts and the Thylacosmilids.

The taxonomy (classification) of both living and extinct species changes frequently. As more fossil evidence comes to light, species are reclassified. Some are given their own species or genus while others are absorbed into an existing species or genus and their original classification is scrapped.

|

Kingdom |

Animalia |

The animal kingdom |

|

Phylum |

Chordata |

Animals that have backbones |

|

Class |

Mammalia |

Animals that suckle their young |

|

Order |

Carnivora |

Animals that eat meat |

|

Superfamily |

Feliodea/Aeluroidea |

(Includes cats, hyenas, civets, mongooses) |

|

Family |

Felidae |

Modern cats |

|

Subfamily |

Acinonychinae |

Cheetah family |

|

Subfamily |

Felinae |

Small cats |

|

Subfamily |

Pantherinae |

Big cats (Tiger, Lion etc) |

|

Subfamily |

Machairodontinae |

Sabre-toothed cats (extinct) |

|

Epoch |

Years |

Notes |

|

Paleocene |

58 to 64 million years ago |

Began with extinction of dinosaurs. Emergence of early mammals. |

|

Eocene |

55.5 million to 38 million years ago |

Emergence of first modern mammals. Epoch ended with a major extinction event. |

|

Oligocene |

33.7 million to 23.8 million years ago |

A relatively quiet time for mammalian evolution, few new faunas appeared. |

|

Miocene |

5 million to 24 million years ago |

Recognisably modern mammals appeared. |

|

Pliocene |

5 million to 1.8-1.6 million years ago |

Modern mammals continue to diversify. |

|

Pleistocene |

1.8-1.6 million to 10,000 years ago |

Includes the ice ages. |

|

Holocene |

10,000 radiocarbon years ago to present day |

Recent era. Also called Alluvium epoch. |

|

Other Definitions |

|

|

Marsupials |

Pouched mammals such as kangaroos and wombats. |

|

Placentals |

Mammals that carry their young to full term in an internal womb. |

|

Eutherians |

Placental mammals. |

|

Taxon (plural: Taxa) |

A creature's taxonomic classification. |

Although there are references to animals being found in places far apart on the modern world map, the continents used to look very different. Some land masses that were once joined together have now split and drifted apart, others that were far apart have collided. Some land masses that are currently not joined to each other were joined by ancient land bridges when sea levels were much lower than they are today.

EVOLUTION OF MODERN CATS (SUMMARY)

Carnivorous mammals evolved from Miacids small pine marten-like insectivores that lived 60 million - 55 million years ago. The miacids split into two lines: Miacidae and Viverravidae. Miacidae gave rise to Arctoidea/Canoidea group (bears and dogs) while Viverravidae gave rise to Aeluroidea/Feloidea group (cats, hyenas, civets, mongooses) around 48 million years ago. The Viverravidae also gave rise to a group called Nimravidae. The Nimravids were cat-like creatures that evolved in parallel with true cats; they are not part of true cat lineage and have left no living descendants.

Please note that the lineages are revised regularly as more fossils, mostly incomplete, are found! In time, many tend to be combined with existing species. Below is the state of affairs in 2018.

The first true cat to arise from Viverravidae was Proailurus (first cat") around 25 million years ago. The best-known species was P lemanensis, found in France. Proailurus was a small weasel-like cat with relatively short legs and a long body. It had one more premolar on each side of its bottom jaw than do modern cats. About 20 million years ago, Proailurus gave rise to Pseudaelurus. Pseudaelurus were Miocene ancestors of cats. Various Pseuaelurids have been identified, for example Pseudaelurus lorteti (about the size of a large lynx) and Pseudaelurus validus (the size of a large lynx or small puma). Three other species of early cat were described as Pratifelis, Vishnufelis and Sivaelurus (S chinjienis).

The Pseudaelurus group split into three major lineages. The Pseudaelurus lineage gave rise to Machairodontinae (true sabre-tooths). The Hyperailurictis lineage gave rise to the Nimravidae. The Styriofelis lineage (previously called Schizailurus) led to the modern day Felidae group (true cats).

|

|

|

The very early cats would have looked something like this modern day Fossa, a Madagascan mammal related to the Mongoose. This carnivore occupies a similar ecological niche to cats and preys on lemurs and rodents. |

|

EARLY ANCESTORS OF THE CAT: PROAILURUS & PSEUDAELURUS |

|

|

Genus: Proailurus[Syn: Brachictis, Stenogale] Proailurus lemanensis ("Leman's Dawn Cat") |

Genus: Pseudaelurus[Syn: Ailuromachairodus, Sansanailurus, Schizailurus] |

|

Note: Taxonomists rarely agree over which species are separate and which are synonyms. For example, some members of Pseudaelurus have been classified as Metailurus (see the table for Machairodontinae). |

|

18 million years ago, Styriofelis (synonym Miopanthera) gave rise to the Felidae. The first of the modern Felids were the early cheetahs; now represented by Acinonyx (modern cheetah); true cheetahs are believed to have evolved around 7 million years ago. Some sources claim Miracinonyx (North American cheetahs) evolved only 4 million years ago from Acinonyx, but recent studies show Miracinonyx was probably ancestral to both cheetahs and puma and was intermediate in type between these two modern species.

Around 12 million years ago, genus Felis appeared and eventually gave rise to many of our small cats. Two of the first modern Felis species were Felis lunensis (Martelli's cat, extinct), and Felis manul (Manul or Pallas's Cat, living). Extinct Felis species are: F attica, F bituminosa, F daggetti, F issiodorensis (Issoire Lynx), F lunensis and F vorohuensis. The ancestor of modern Felis species was F attica. Genus Panthera ("biting cats" or "roaring cats") genera evolved around 3 million years ago; there are a number of extinct species discussed later in this article.

Genera Acinonyx, Felis and Panthera are all represented today and taxa of some modern species is regularly revised as more complete fossils of ancestral species are found, giving a clearer indication of who begat whom and when various lineages split.

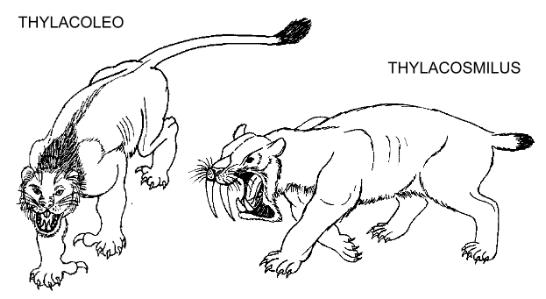

FAMILY THYLACOSMILIDAE: MARSUPIAL "SABRE-TOOTH TIGER"

The jaguar-sized Thylacosmilus ("pouched blade") was a large, predatory marsupial; part of a unique group of predators on the South American pampas; the borhyaenids. These appeared in the Miocene and ruled the South American forests and woodlands for some 30 million years, but have no known ancestor or descendant. Thylacosmilus was the most successful member of that family and was the ultimate mammalian predator of its day in Plio-Pleistocene South America, but when the continents of North America and South America joined, it lost out to the more highly developed and faster eutherian cats.

Two species are described: T atrox and T lentis. Thylacosmilus atrox looked like a sabre-toothed cat, but is more closely related to kangaroos. As far as we know, Thylacosmilus was the only marsupial to have developed the sabre-toothed weapon. Like Smilodon, the eutherian sabre-tooth tiger, it had adapted to hunting mega-fauna.

Thylacosmilus lacked incisor teeth, but had very long upper canine teeth that grew continually. These long stabbing teeth projected below the mouth-line. Strong neck and jaw muscles allowed the sabre-teeth to be driven downward with a tremendous killing force. Its huge stabbing teeth were about 15 cm (6 inches) long (longer than those of Smilodon) and may have been used to slash the soft throat of its prey. The jaws were capable of a gape that left the teeth clear to do their work. These sabres grew continually throughout Thylacosmilus's life, much like the incisors of modern rodents. Unlike Smilodon (see later), it had no scabbard-like tooth-guards on its lower jaw though its skull had a deep flange on its lower jaw, forming a protective sheath for when the sabre teeth were not being used.

Unlike modern cats, which tend to be sleek and long-legged, it appears to have been short-legged and heavily built, being about 1.2 metres (4 ft) long and weighing around 100 kilos. Its claws were not retractile. It probably preyed on large, slow-moving mammals and when the two continents joined, the highly specialised Thylacosmilus could not compete against the faster, sleeker eutherian big cats. South America has also had at least three species of cats whose body weights exceeded 300 kilos - about twice the weight of modern lions.

FAMILY THYLACOLEONIDAE: MARSUPIAL "LION"

The Thylacoleonidae were lion-like marsupials that inhabited Australia in Oligocene to Pleistocene times. They probably hunted across the Australian grasslands, although some may have been arboreal. They were vombatomorphian (wombat-like) marsupials, evolved from herbivore ancestors; their closest living relatives being koalas and wombats. The more primitive species had generalised crushing molar teeth (like modern omnivores) as well as carnassial blades. In more specialised species, the crushing molars were reduced or absent and the carnassials had become huge.

The Thylacoleonidae ranged from the size of a domestic cat to the size of a leopard and possibly even the size of a lion (1.7 metres/5 ft 6 in). So far, eight species of marsupial lion have been discovered and there may be at least two more. Those of genus Wakaleo were leopard-sized and designed for power rather than speed. W alcootaensis was slightly larger than W oldfieldi or W vanderleueri. These "marsupial leopards" may have ambushed prey from tree branches. Priscaleo was much smaller. P pitikantensis was about the size of a modern Australian possum. P roskellyae was about the size of a domestic cat, possibly up to ocelot-sized, and may have been arboreal.

|

FAMILY: THYLACOLEONIDAE (MARSUPIAL LIONS, MARSUPIAL LEOPARDS) |

||

|

Genus: PriscileoP. pitikantensis (Oligocene) |

Genus: WakaleoW. oldfieldi (Miocene) |

Genus: Thylacoleo [Thylacopardus]T hilli (Pliocene) |

The most famous member of this family is Thylacoleo carnifex, the "marsupial lion". This was Australia's equivalent to the South American marsupial Thylacosmilus atrox and to the eutherian Smilodon. Its enormous meat-shearing carnassial (cheek) teeth were the largest of any mammalian predator. It also had bolt-cutter incisors, and switch-blade-like claws on its semi-opposable thumbs. It was the most specialised mammalian carnivore ever known; entirely lacking grinding teeth. Because T carnifex lacked large canines, it was originally believed to be a herbivore, using its unusual front teeth and claws to break open nuts and fruit; its lack of grinding teeth suggest a diet of soft fruit such as melons! However, wear on the teeth indicates a meat-eating diet, and it probably preyed on giant kangaroos and wombats of the time. Compared to sabre-tigers, such as Smilodon, it had a short cat-like face and more elaborate carnassial teeth, giving it a powerful killing bite. Most modern cats have carnassials that can crunch smaller bones, but Thylacoleo's teeth lacked bone-crunching adaptations and were entirely adapted to shearing soft tissue. Projecting front incisors were modified into killing teeth, and looked rather like the canines in the placental carnivores; the actual canine teeth were insignificant.

T carnifex had a short body, closer in length to that of a leopard rather than a lion, but the bones of its legs show it was far more robust than a leopard. Estimates derived from size (partly based on skull size) and robustness suggest it weighed between 100 and 130 kilos, putting it in the same size range as modern tigers and lions. It was extremely robust and built for power rather than endurance, with tremendously powerful forelimbs. It probably ambushed prey as large as, or larger than, itself, using the thumb claws to hold the prey in a deadly embrace while employing its fang-like incisors.

T carnifex survived until around 50,000 years ago and may have come into conflict with early Aboriginal settlers entering Australia. Conflict and competition with humans, and with the introduced dingo, may have contributed to the extinction of this highly specialised carnivore. There are theories that relict populations of smaller marsupial lions survive in the form of the cryptozoological "Queensland Tiger". Like Thylacoleo, the Queensland Tiger is described as short-headed, sharp-clawed and superficially cat like. Eyewitnesses (and a single photograph) show it to have vertical striped on the forequarters. It has never been positively identified.

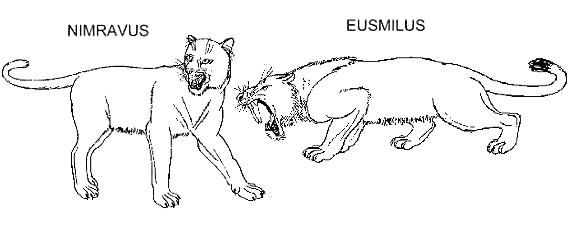

NIMRAVIDS: FALSE SABRE-TOOTH CATS

The Nimravidae were a separate family of cat-like animals that evolved parallel to the true cats (Felidae). The common ancestor of the Nimravidae and the Felidae was the Viverravidae (feline-like) group of miacids some 55 million years ago in the late Eocene. Proailurus, a descendent of the miacids, evolved into Pseudaelurus, which split into two main groups, one of which became the modern cats (Neofelids), and one became the Machairodonts (true sabre-toothed cats, a sub-family of the Felidae). Nimravids are also known as the Paleofelids (ancient cats), or False Sabre-toothed Cats (because they are cat-like, but not true cats). Another synonym was Archaelurus. They were the earliest cats to evolve and lived from the late Eocene (36 million years ago) to the late Miocene (5 million years ago), peaking around 28 million years ago. The subfamilies of nimravid and their genera are shown in the table below. Some are known from single or fragmented specimens and the taxonomy regularly changes as more fossils are discovered.

Nimravids had different skulls to true cats. The structure of their middle and inner ear was different and many Nimravids had a flange on the front of the lower jaw (also seen in some machairodonts [true sabre-tooths] and thylacosmilids [marsupial sabre-tooth]). The flange is a bony prominence that projects downwards and is as long as the canine teeth; the teeth fit into a groove. Barbourofelis – now considered a family in its own right and not a nimravid - had the most prominent flange, while Nimravus and Dinaelurus lacked a flange. The actual sabres were narrow, pointed canines whose length varied according to species.

Nimravids were very cat-like in appearance and had retractile claws. Many were muscular and low slung with heavy-set bodies on short legs. Like the modern lynx, some were short-tailed although many others were long-bodied and long-tailed. The skulls of genera Dinictis, Nimravus and Dinaelurus are especially cat-like. Their prominent upper canines were longer than those of modern cats, but shorter than those of the true sabre-toothed cats; their lower canines were proportionally longer. The most common species in the fossil record are those belonging to Dinictis, Eusmilus and Hoplophoneus.

Hoplophoneus lived during the late Oligocene (33 - 30.5 million years ago), some 20 million years before Smilodon. Some earlier authors erroneously place Hoplophoneus among the Felidae (true cats) as the ancestor of Smilodon and true sabre-tooths, but current fossil evidence makes this incorrect and indicates that Hoplophoneus and Smilodon are from different evolutionary lines. Some were the size of bobcats while others were jaguar-sized. Like many other Nimravids, Hoplophoneous had a bony flange into which its curved canines fit.

Nimravus has been found in France and parts of North America from the early Oligocene to early Miocene. Some were 1.2 metres (4 ft) long. With its sleek body, it may have resembled the modern caracal, although it had a longer back and more dog-like feet with partially retractile claws. It competed with other false sabre-tooths such as Eusmilus. A Nimravus skull, found in North America, had been pierced in the forehead region, the hole exactly matching the dimensions of Eusrnilus' sabre tooth; Nimravus survived as the wound showed signs of healing. It probably hunted birds and small mammals, ambushing them like modern cats, rather than chasing them down. Some specimens still have unclear classification, for example a species once identified as N catacopis is closer to true cats and is now classified as Machairodus aphanistus (previously Machairodus catacopis).

Dinictis was a small nimravid that lived on the plains of North America during the late Eocene and early Oligocene (40 million years ago). Dinictids had a sleek bodies, short legs, long tails, and walked plantigrade ("on the whole foot" modern cats walk digitigrade "on the toes"). Pogonodon was a cat-like sabre-tooth.

Eusmilus was a dirk-toothed cat found in France and parts of North America during the late Oligocene (30.5-28.5 million years ago). It was noted for its long, flattened sabres and very prominent mandibular flange. Most were leopard-sized and rather long-bodied and short-legged compared to modern leopards. Some reached 2.5 metres (8 ft) long. It was a typical false sabre-tooth with enlarged upper canines, but insignificant lower canines, while many of the other teeth had been lost to accommodate its sabres (Eusmilus had 26 teeth, compared to 44 teeth in other carnivores). The jaw hinge was modified to open to an angle of 90 degrees to allow the great sabre teeth to do their work. Its lower jaw had bony guards that lay along the length of the sabres, protecting them from damage when the mouth was closed. There is fossil evidence of conflict between Eusmilus and Nimravus.

|

FAMILY: NIMRAVIDAE (PALEOFELIDS; FALSE SABRE TOOTHED CATS) |

||

|

Subfamily Nimravinae |

Tribe Hoplophoneini(Formerly Subfamily Hoplophoninae) |

Subfamily Barbourofelinae |

|

Genus: Dinailurictis Genus: Dinictis Genus: Eofelis Genus: Nimravidus Genus: Pogonodon Genus: Quercylurus Genus: Archaelurus Genus: Aelurogale [Ailurictis, Ictidailurus, Nimraviscus]

Tribe: Nimravini Genus: Dinaelurus Genus: Nimravus [Nimravinus] |

Genus: EusmilisGenus: Hoplophoneus Genus:Nanosmilus |

Subfamily BarbourofelinaeThese are now considered a family in their own right and not a sub-family of the Nimravids. |

|

Note: The names prefixed with "?" are questionable. They may result from misidentification of incomplete fossils. |

||

BARBOUROFELIDS: FALSE SABRE TOOTHED CATS

Barbourofelidae was formerly considered a subfamily of Nimravidae, but is now thought to be taxonomically closer to the Felidae (true cats) than to the Nimravidae, Barbourofelids are now considered a distinct family, first appearing in Africa in the Early Miocene and later spreading to Europe and North America. Although they ranged from leopard-size to lion-size, their brains were closer in size to that of the modern bobcat, indicating that they were less intelligent than modern leopards or lions. Barbourofelids are commonly found in the fossil record and lived during the late Miocene (15 million - 6 million years ago), They had longer canines than the nimravids. They had very prominent flanges on the lower jaws and an unusually shaped skull. The distinctive sabre-teeth did not erupt until the cubs reached near adult size, meaning they were dependent on their mothers, or on a pride-like social structure, well into their second year.

|

FAMILY: BARBOUROFELIDAE (PALEOFELIDS; FALSE SABRE TOOTHED CATS) |

|

| Genus: Afrosmilus Genus: Prosansanosmilus Genus: Sansanosmilus Genus: Syrtosmilus Genus: Barbourofelis Genus: Albanosmilus |

?Genus: Ginsburgsmilus

?Genus: Vampyrictis

?Genus: Vishnusmilus

Note: The names prefixed with "?" are questionable. They may result from misidentification of incomplete fossils. |

Albanosmilus lived during Middle and Upper Miocene in Europe, Asia, and North America and was bulkier and more muscular than modern big cats, probably resembling a bear-like lion. Prosansanosmilus and Sansanosmilus were very muscular, short legged and probably walked plantigrade (flat-footed). Modern cats have a digitigrade (on the toes) walk. Later barbourofelids appear to have had semi-plantigrade or semi-digitigrade stances.

MACHAIRODONTINAE: TRUE SABRE-TOOTH CATS

|

|

|

The Machairodontinae are true cats and their fossils have been found in North America, Europe, Asia and Africa. Although we tend to think of the sabre-toothed tiger, there were two varieties of sabre-toothed cats: dirk-toothed cats and scimitar-toothed cats. Dirk-toothed cats had two long, narrow upper canines, and were usually short-legged and stocky. Scimitar-toothed cats had upper canines that were shorter and broader, longer, thinner legs and were generally more lithe. The exception was a cat known as Xenosmilus, which has the short, broad canines of a scimitar-toothed cat, but has short legs.

Modern cats have conical canine teeth, but the machairodonts' (machairodont means "sabre tooth") canines were flattened from side to side (like a blade) as well as being elongated. To accommodate their large canines, they had fewer upper premolar teeth. Their incisor teeth were larger, angled differently and placed further forward than in modern cats. Other adaptations allowed them to open their jaws extremely wide and gave them strong neck muscles. Some species, such as Megantereon, had a bony flange that protruded downward from the front of their lower jaw.

Although the sabre-toothed cats have long dagger-like canines, these were probably too blunt and fragile to be used to stab prey. They were unlikely to have gone for the nape of the neck to sever the spine, like many modern cats. If they hit bone, they could shatter (leading to abscesses and possibly fatal bacterial infections). The current theory is that sabre-toothed cats went for the soft throat of their prey, using their powerful teeth to sever the arteries and windpipe.

|

FAMILY: FELIDAE, SUB-FAMILY: MACHAIRODONTINAE (SABRE-TOOTHED CATS) |

||

|

TRIBE METAILURINI |

TRIBE HOMOTHERIINI |

TRIBE SMILODONTINI |

|

Genus: Dinofelis [Therailurus]Genus: Metailurus Genus: Adelphailurus Genus: Stenailurus Genus: Yoshi

TRIBE MACHAIRODONTINI Genus: Hemimachairodus Genus: Miomachairodus Genus: Machairodus [Heterofelis] |

Genus: AmphimachairodusGenus: Homotherium [Dinobastis, Epimachairodus] Genus: Lokotunjailurus Genus: Nimravides Genus: Xenosmilus ?Genus: Afrosmilus ?Genus: Hemimachairodus. |

Genus: Megantereon Genus: Promegantereon Genus: Paramachairodus [includes Propontosmilus, Pontosmilus, Sivasmilus] Genus: Rhizosmilodon Genus: Smilodon [Ischyrosmilus; Smilodontopsis; Trucifelis]

UNKNOWN TRIBE Genus: Tchadailurus |

|

Note: The names prefixed with "?" are questionable. They may result from misidentification of incomplete fossils. |

||

METAILURINI TRIBE: SCIMITAR TOOTHED CATS

These were Eurasian scimitar-toothed cats that lived during the late Miocene to early Pleistocene.

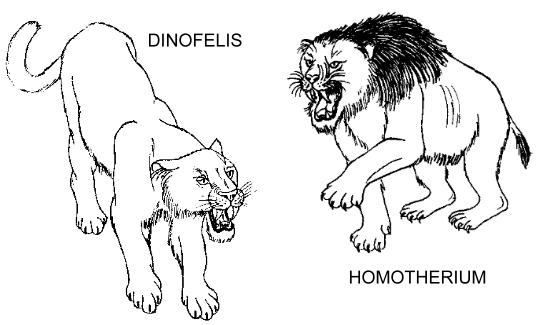

The best known genus is Dinofelis ("giant cat") which lived in Eurasia, Africa and North America around 5 million - 1.5 million years ago. In South Africa, Dinofelis has also been found at sites along with Australopithecines, so it was probably a predator of our own ancestors. Genus Dinofelis includes cats previously classified as Therailurus. It became extinct in Eurasia and North America during the Early Pleistocene, but survived in Africa until the Mid-Pleistocene. The largest known form was the Chinese D abeli. Its size and build are comparable to a large leopard or jaguar (1.2 metres/4 ft) with forelimbs more heavily built than hind-limbs. Like the modern jaguar, they may have been forest-dwellers. Dinofelis ("giant cat") had flattened canines considerably shorter than those of the sabre-tooths, scimitar-tooths or even dirk-tooth cats. The canines were longer than those of biting cats (those that kill prey with a single neck-bite) so it is debatable as to which subfamily of the Dinofelis belongs.

Metailurus lived 15 - 8 million years ago and were similar to Dinofelis in body type and shape. They were smaller than Dinofelis, being leopard sized, but had longer canine teeth, intermediate between modern cats and sabre-toothed cats. Like Dinofelis, Metailurus was stockily built with forelimbs more heavily built that its hind limbs. Its build suggests it hunted in forested areas and may have been more arboreal than Dinofelis.

The puma-sized Adelphailurus is known from a single type specimen from Kansas, USA. Unusually for a cat, Adelphailurus kansensis retained the upper second premolar, a trait it shared with Stenailurus. The members of genus Pontosmilus were formerly classified as Paramachairodus.

HOMOTHERIINI TRIBE: HYENA-LIKE SABRE-TOOTHS

This comprises the genera Machairodus, Homotherium and Xenosmilus. Classification is liable to be revised as more fossils are discovered and there are museum specimens assigned to 4 other genera.

Machairodus is a variable genus of large sabre-toothed cats ranging in size and structure from smaller varieties right up to lion-sized. They were found in Europe, Asia, Africa and North America from 15 - 2 million years ago. The taxonomy is debatable. They have large canine teeth, and its incisors, canines and carnassials has serrated edges. There were two basic types of Machairodus: the primitive type and the evolved type (possibly adaptations to different environments). The more primitive types included M aphanistus and resembled Smilodon. The more evolved type had serrated teeth and elongated forelimbs structurally similar to the hyena-like Homotherium; they may have been ancestral to Homotherium. The variable forms indicate a adaptations to different environments ranging from forest/woodland dwelling to plains hunting. The hyena-like species may have covered long distances while hunting or for opportunistic scavenging.

Homotherium (therium = "beast") is a group of unique hyena-like sabre-toothed cats that also ranged widely (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America) from 3 million - 0.5 million years ago. They were about 1.2 metres (4 ft) long with front limbs longer than the rear ones. Homotherium's incisors were very large and robust and they had serrated medium-length canine teeth. Homotherium is a scimitar-toothed cat i.e. it has shorter, flatter canines than other sabre-tooth cats and its canines curve backwards like scimitar blades. Homotherium would have had the sloping look of a hyena with slender legs and relatively long neck. Its anatomy suggest that it walked with the whole foot on the ground (plantigrade) like a bear. This hyena-like conformation may have allowed them to cover long distances when hunting. It is more likely to have walked semi-plantigrade, the back sloping slightly; an adaptation for greater strength.

Homotherium survived until the end of the last ice age about 14,000 years ago and probably preyed on mammoths, possibly hunting in family groups. In Texas, the bones of a family group of scimitar-tooths are preserved alongside young mammoths and their eventual extinction was probably linked to a decline in prey species. As an adaptation to ice age conditions, some species may have been white or pale grey (like modern arctic predators).

H serum, the North American scimitar cat ,was originally named Dinobastis serus. It was short-tailed and slender-limbed, with relatively long forelimbs and short, powerful hindlimbs. Its deepened chin meant that its upper canines did not protrude beyond the lower margin of the lower jaw. H serum's large nasal opening, like that of the cheetah, would have allowed quicker oxygen intake aiding in rapid running. Skulls show it had a large visual cortex, indicative of a daytime hunter. It was built for short bursts of speed, rather than long chases. The claws of its forelimbs were not retractile, allowing better traction at high speed. Its hind limbs were shorter than its forelimbs and had a bear-like heel and ankle. The long hind feet had non-retractile claws.

H latidens is depicted in paleolithic stone carvings from Isturitz, south-western France show a short-tailed big cat with a deeply set lower jaw. This matches the traits of the European Scimitar-tooth, H latidens. The carving suggests that the cats had spotted pelts and paler undersides. H ultimum, the Asian scimitar cat, occurred in China.

Homotherium ischyros (or Ischyrosmilus), had canines serrated like steak-knives, along their front and back edges. This made it easier to slice through the skin of thick-skinned prey. Megantereon lacked these serrations on its upper canines. Ischyrosmilus's exact taxonomy is unclear and it may be one of the Smilodontini.

Xenosmilus ("strange knife") lived in the Florida, USA region 1.7 - 1 million years ago and was a robust cat with short legs and very thick, stout canine teeth. It was lion-sized, very robust and somewhat bear-like Pleistocene felid (length 2 metres / 7 ft, weight 180-230 kg / 400-500 lbs). Like Homotherium, it had broad, knifelike, coarsely crenulated teeth and projecting long, curved, serrated incisors, but it had the short, stout-legged features of Smilodon. Originally palaeontologists thought they had mixed up the bones of 2 other species since dirk-tooth cats were bear-like with two long, narrow upper canine teeth and short legs, while scimitar-tooth cats were longer-legged with two shorter, broader upper canines. Xenosmilus had a mix of features: the short, broad coarsely crenulated teeth of a chasing cat, but the stocky legs of an ambush hunter. It probably stalked close to its prey and then sprinted from cover to catch it. The specimens were found with bones of peccaries (wild pigs), giving an indication of its main prey. It appears to have been a more specialised sabre-toothed cat than Smilodon and its size made it the most ferocious sabre-tooth in the world at the time. Smilodon may only have become a dominant predator after Xenosmilus vanished.

SMILODONTINI TRIBE: SABRE-TOOTHS AND DIRK-TOOTHS

|

|

|

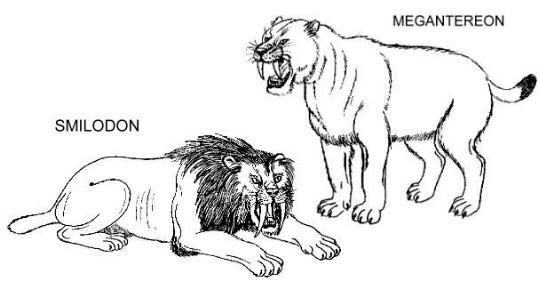

This contains the famous sabre-toothed "tiger", Smilodon ("blade tooth"), of the late Pleistocene age (1.5 million - 10,000 years ago). The three known species were widespread throughout the Americas. Smilodon was stocky, with short, powerful legs and a bobtail. Their canine teeth were the longest of all the true sabre-toothed cats, being about 18 cm long. The South America Smilodon populator was the largest species. The South American Smilodon neogaeus is probably a synonym for S populator. The more famous Smilodon fatalis was found across North and South America, having migrated there from North America during the Pleistocene. S fatalis is sometimes divided into two separate species: S californicus and S floridanus (these may have been sub-species or variant populations i.e. S fatalis californicus and S fatalis floridanus). They are usually compared to the modern lion based on body length (1.2 metres/4 ft) and conformation, but were more robustly and powerfully built. S fatalis and S populator were around 11/2 - 2 times heavier than the average lion (around 170 kilos). Smilodon gracilis was the smallest of the Smilodons and the earliest species (about 2.5 million years ago); it was found in the eastern United States and weighed around 80 kilos.

Smilodon's anatomy shows them to be were specialised hunters of big game; they probably ambushed their prey - their robust build is not designed for chasing it down. Most modern cats have carnassials that can crunch smaller bones, but Smilodon's teeth lacked bone-crunching adaptations and were entirely adapted to shearing soft tissue. The muscles of its shoulders and neck were arranged to produce a powerful downward lunge of its massive head. The jaw opened to an angle of over 120 degrees, to allow the huge upper canines to be driven into prey. The canines were oval in cross-section to retain strength, but also to ensure minimum resistance as they were sunk into the prey. They were also serrated along their rear edges, so they pierced flesh more easily. They probably preyed on large, slow-moving, thick-skinned herbivores, but also scavenged dead and dying animals. More than 2000 Smilodon skeletons have been recovered from the Pleistocene tar pits of La Brea (Los Angeles, USA) where they had been fatally lured by large animals trapped in the tar.

It seems likely that Smilodon lived in family groups, much like modern lions, and possibly hunted in groups. Some specimens showed signs of healed fractures, suggesting they ate food caught by family members. Their extinction seems to have coincided with open plains taking over from forest/woodland. Smilodon was not built for the chase and this reduction in cover would have made it harder to ambush prey.

Megantereon was another genus of cats with impressive canine teeth, although they are not well-represented. About the size of a jaguar (1.2 metres/4 ft), they flourished in the Mediterranean and spread throughout Africa, Eurasia and North America around 3 million - 1 million years ago. The only complete skeleton was found in France. They had very large upper canines but relatively small lower ones. Though impressive, its teeth were more like daggers than sabres in size and shape, hence Megantereon and its immediate relatives are referred to as dirk-tooth (dagger-tooth) cats. They are also characterized by their prominent mandibular flange. Only a single species, Megantereon cultridens, is known from fossil records, although some Chinese specimens are known as M. nihowanensis. They are believed by most to be the direct ancestors of Smilodon and other later sabre-tooth cats.

Also in this group is Paramachairodus, although it is under much debate as to the placement of this genus. Many animals formerly placed in this genus were reassigned to Pontosmilus and placed within Metailurini. They are thought to have existed between 20 - 9 million years ago. The two species known are Paramachairodus ogygia (Spain) and Paramachairodus orientalis, plus the disputed P maximiliani.

ACINONYX AND MIRACINONYX: EARLY CHEETAHS

Modern Felids evolved around 18 million years ago. The first of these were the early cheetahs; now represented by Acinonyx (modern cheetah); true cheetahs are believed to have evolved around 7 million years ago. Some sources claim Miracinonyx (North American cheetahs) evolved only 4 million years ago from Acinonyx, but recent studies show ("miracle cheetah") was probably ancestral to both cheetahs and puma and was intermediate in type between these two modern species. Another cheetah was the Sivapanthera genus.

Cheetah-like cats arose around 18 million years ago. According to some studies, the ancestor of modern cheetahs originated in Africa during the Miocene and later migrated, giving rise to the now-extinct North American cheetahs. More recent studies suggest that a North American cheetah called Miracinonyx was the ancestor of both African cheetahs (modern Acinonyx) and American pumas (Puma concolor). Miracinonyx would have migrated across continents during the Ice Age. Miracinonyx inexpectatus [M studeri] existed in North America during the early Pleistocene (1 to 1.5 millions years ago) and may be even older. It had proportions intermediate between the modern cheetah and modern pumaAs a result, iIt is sometimes linked to the cryptozoological Onza (a gracile form of puma). Two species of cheetah inhabited late Pleistocene North America (100,000 years ago): Miracinonyx inexpectatus [M studeri] and Miracinonyx trumani.

Fossil evidence of early cheetahs is fragmentary, but Miracinonyx resembles modern cheetahs in having a short face, wide nasal passages and long body, but were less lanky. M inexpectatus and M trumani may be the reason North American evolved into such fast sprinters; North America has no living predator able to match the pronghorn's in speed. Unlike modern cheetahs, Miracinonyx inexpectatus had fully retractile claws and more robust conformation with shorter limbs than modern cheetahs. M inexpectatus would have been faster than the puma, but not as accomplished a sprinter as modern cheetahs; it was also better equipped for climbing.

The early true cheetah, Acinonyx pardinensis, appeared during the Pliocene and at 200 lbs were much larger than modern cheetahs. Known as Giant Cheetahs, they became widespread in China, southern Europe and India throughout the Ice Age, were lion-sized cheetah and probably as fast as modern cheetahs. Intermediate-sized cheetahs, Acinonyx intermedius, ranged from Africa as Far East as China during the mid-Pleistocene and became adapted to hunting on open grassland. These were larger than modern cheetahs. Acinonyx parchidinensis was the Pleistocene cheetah. The smaller modern cheetah, A jubatus, was once much more widespread, but became extinct in eastern Asia at the end of the Ice Age.

PANTHERA: BITING CATS

Biting cats are so-called because their relatively short, strong canines are adapted to dispatching prey by biting the bones and sinew of the neck and throttling it. Genus Panthera genera evolved around 3 million years ago and these have become the modern day big cats ("roaring cats" or "biting cats"). Prehistoric relatives of modern big cats lived between the Pleistocene to Recent times and ranged across South Africa, Asia, Europe and North America. Some, such as the "cave lion" were truly impressive creatures, reaching 3.5 metres (111/2 ft). The modern lion, Panthera leo, is now restricted to parts of Africa and to western India. There are extinct sub-species of the modern lion; until recent times there were sub-species in Arabia and Iran (the Barbary lion has been rediscovered and is being conserved).

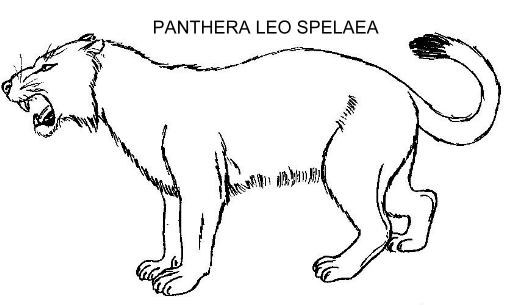

Primitive lions (P leo fossilis) dispersed in the Old World about 500,000 years ago. P youngi, from north-eastern China 350,000 years ago, had similarities to both P leo spelaea (European Cave Lion) and P leo atrox (North American Cave Lion) and may be a link between the Eurasian/American cave lions and Asian/African modern lions. Extinct Panthera species include: P atrox (P leo atrox) (American lion), P gombaszoegensis (European jaguar), P leo spelaea (European Cave Lion), P palaeosinensis (a primitive leopard), P pardoides (a primitive leopard), P schaubi (a short-faced leopard) and P toscana (Tuscany lion, Tuscany jaguar). Some of these classifications are being revised as more complete specimens are discovered. Panthera schaubi (syn Viretailurus schaubi), which resembles a short-faced leopard, is currently regarded as an Old World puma, Puma schaubi.

Panthera leo spelaea, the European Cave Lion (300,000 to 10,000 years ago), was probably the largest cat that ever lived, being around 25% larger than modern lions, and larger than modern Siberian tigers. It was probably comparable in size to modern liger hybrids. It ranged across most of Europe and is depicted in cave paintings. Cave paintings and remains show that it lived until historical times in south-eastern Europe and possibly as recently as 2000 years ago in the Balkans. Cave paintings from Germany show cave lions as having ruffs or manes and tufted tails. A wall engraving from France and an ivory figurine of a lion-pelt-wearing human from Russia indicate faintly striped pelts. European Cave Lions inhabited steppes and parkland regions in the north and semi-desert areas in the south of Eurasia. They were evidently not adapted to deep snow or to dense forests.

Panthera atrox (P leo atrox) was a North American lion whose range extended to northern South America (Peru). P atrox crossed to North America over the Bering Strait land bridge during the last ice age, about 35,000 to 20,000 years ago. Its remains have been found in Alaska and some specimens have been found in the La Brea tar pits, Los Angeles, USA. Relatively few P atrox fossils have been recovered from La Brea compared to fossils of other carnivores; this lion may have been intelligent enough to avoid the natural traps. It probably hunted deer, North American horses (which became extinct and were reintroduced by European settlers) and American bison. They were among the largest flesh-eating land animals that lived during the Ice Age. Compared to modern African lions, they attained enormous size (25% larger) and had relatively long, slender limbs.

Panthera schaubi, currently classified as Puma schaubi, was a short-faced leopard-like cat about the size of a small leopard or large lynx; it is believed to be an Old World puma. Fossil leopards have been found in France and Italy, but in small quantities suggesting they were not prevalent in Europe. Felis lacustris ("Lake Cat"), also appears to be a North American Pliocene puma.

Panthera gombaszoegensis (P onca gombaszoegensis), the European Jaguar, was present around 1.6 million years ago and was larger than early American jaguars, probably hunting larger prey. They ranged across Italy, England, Germany, Spain, and France. Although currently given its own classification, P toscana, the Tuscany Lion (aka Tuscany Jaguar), may turn out to be a synonym for P gombaszoegensis. A form similar to P gombaszoegensis has been found dating from early Pleistocene East Africa and had both lion- and tiger-like characters.

"Pleistocene Tigers" have been found in Alaska, North America and are dated at only 100,000 years ago. There is debate over whether these were tigers or lions since the two species are structurally similar, resulting in some authorities giving the American tigers a separate classification. Pleistocene jaguars (approx 1.5 million years ago) were found as far north as Washington state and Nebraska, USA. Similar in size to modern jaguars they probably had similar lifestyles and pursued similar prey. The modern jaguar's range is South America and Central America, although some individuals have been found as far north as Texas and Florida, USA.

Lynx were known to be present in North America and Eurasia in Pliocene or Pleistocene time. The common ancestor of modern lynx and bobcats was probably a North American lynx of 6.7 million years ago. The extinct Issoire Lynx (Lynx issiodorensis) of 4 million years ago was larger than modern lynx with shorter legs. Modern lynx are smaller, a trend that is true in other species such as cheetah, jaguar, leopard and lion where the prehistoric forms were giants compared to their modern descendents. Their larger size was either an adaptation to colder climes or to cope with larger prey species.

A Pliocene Lynx from Britain was described as Felis (Lynx) brevirostris in 1889. Bobcats are related the Lynx. Earliest records of Bobcats (Lynx rufus, Felis rufus) date back 3.2 to 1.8 million years ago. It is the descendant of an earlier and larger Pleistocene species Lynx issiodorensis. A predominant Pleistocene subspecies of Bobcat was Lynx rufus calcaratus (Irvingtonian Bobcat), which was slightly larger than modern Bobcats. Another Pleistocene subspecies was Lynx rufus koakudsi.

North American Pliocene small cats include: Felis lacustris ("Lake Cat"), once considered to be a lynx, but now believed to be a puma; F rexroadensis which could be either a lynx or a leopard; F protolyncis ("Early Lynx") and F longignathus, which both resemble Lynx.

GENUS FELIS: PURRING CATS

Genus Felis evolved around 12 million years ago. This genus Felis eventually gave rise to many of our small cats. They are known as "purring cats" because of the structure of their throat.

Two of the first modern Felis species were Felis lunensis (Martelli's cat, extinct), and Felis manul (Manul or Pallas's Cat). The ancestor of modern Felis species, including domestic cats, was F attica [syn F christoli].

Extinct Felis species are: F attica (primitive cat), F bituminosa, F daggetti, F issiodorensis, F lunensis and F vorohuensis (Pleistocene cat). The following debatable species may also be found in literature: F maniculus, F wenzensis, F antediluvia ("Cat from before the Biblical Flood"), F vireti, F (Sivafelis) obscura.

Fossils of a presumed prehistoric margay, Leopardus amnicola ("River Margay"), have been found in Arizona and Florida, USA.

WHAT DID THEY LOOK LIKE?

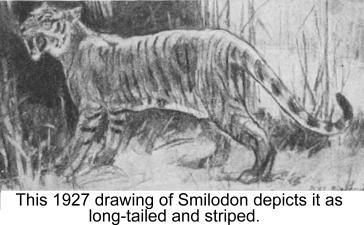

We have a fairly good idea of the size and shape of prehistoric cats and cat-like creatures, but what did they actually look like? Did prehistoric "lions" they have manes and tail tufts? Did the sabre-tooth "tiger" have stripes? Where they sleek or shaggy? Prehistoric cats and cat analogues were shaped by the same forces that shaped modern cats, allowing us to create an image of what they looked like.

Like modern cats, most were ambush hunters, lying in wait for prey or stalking it before making a final dash. This means they needed camouflage. Spots and swirls break up the outline of a predator in undergrowth, while plain sandy or tawny hues blend into drier or barer backgrounds. The cats that hunted on open plains were probably sandy brown or tawny like modern cougars and lions, possibly with faint dappled markings. Others were probably more greyish in colour, like modern northern lynxes. Forest and woodland forms would need leopard-like or jaguar-like markings to blend in with dappled shade, though some may have been black. Although we speak of sabre-tooth "tigers", they would not have been striped unless they lived in habitats similar to those of modern tigers e.g. woodland with twiggy undergrowth or tall reeds . Depending on their habitat, the smaller cats would most likely have been similar to modern Ocelots (swirled), European and African Wildcats (faint mackerel tabby markings) or Leopard cats (spotted).

Those prehistoric big cats that lived in permanently snowy and icy climes would have needed paler coats to blend in with snow or patchy snow. They may have had coats resembling modern snow leopards. Some may have been almost white. They would need longer, denser fur to protect them from the cold, compared to those in warmer climes who would have shorter, sleeker coats Like modern cats, prehistoric cats in temperate zones (with summer and winter periods) would have moulted and grown longer coats for winter and shorter coats for summer. Modern male lions have manes, partly for social display and partly to protect their neck region during fights with competing males. There is some evidence that Smilodon was also social and lived in family groups, so Smilodon males may also have had manes or well-developed ruffs.

Most illustrations and reconstructions of prehistoric cats and cat analogues base their colour schemes on modern cats of comparable sizes living in comparable habitats. The remarkable similarity of cats living in similar habitats in different continents (e.g. lion and puma, jaguar and leopard) makes it reasonable to assume that ancient cats in corresponding habitats also evolved similar markings.

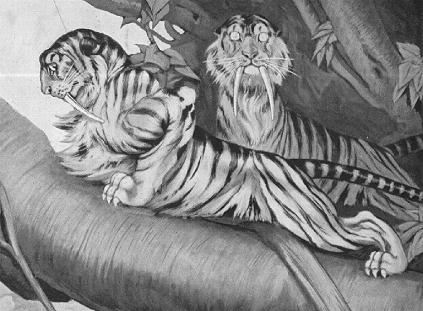

Older encyclopaedias show them as lions or tigers with long tails and over-sized teeth. The following image and texts are excerpts from "Wonders of Land and Sea" (?1913, edited by Graeme Williams). The text accompanying this depiction read "It is believed by some naturalists that the stripes of the sabre-toothed tiger ran horizontally along the body, while others maintain that they were as represented here." The image is a romanticised view of two Smilodons in the branches of a huge tree.

Before the Eocene was passing through the Oligocene into the Miocene, the carnivorous type had reached its most extravagant development, not merely in the ancestral Cat, but in the Sabre-toothed "Tigers.” (A better name for this group is Machairodont - sabretoothed - as they were not specially allied to tigers; the tiger is a true cat of very modern origin.) The Machairodonts were the extreme of mammalian ferocity - felines preserving some primitive features lost by modern eats, but adapted in teeth and jaws for slaying beyond any other mammal.

The mouth of the Sabre-toothed Tiger (which type did not reach its culmination, however, till the close of the Miocene), could open with a gape that must have measured a foot and a half in the biggest examples. And thus the twelve-inch long, flattened, sabre-like, serrated canines of the upper jaw could be plunged for all their length into the neck or body of some great herbivore, aided by the leverage exercised by the prolonged chin, with its massed incisors and stunted canines. The molar teeth, reduced to two on each side, served only to sever, not to masticate, parcels of flesh. These gobbets must have been swallowed whole; or possibly the extreme form of the Machairodont lived mainly by blood-sucking, after severing the great arteries with its teeth. The biggest and most awful of the Sabre-tooths (Smilodon neogeus) lived in South America, lingering on almost to the human period in that region; while in Europe and Asia its near allies of the same genus were certainly contemporaneous with man. Indeed, in England the Sabre-toothed “Tiger” was possibly still in existence 100,000 years ago, when Paleolithic man had begun to take possession of the caves.

The True Cats, as distinct from the Machairodonts, apparently originated in Europe, and did not reach America till quite late in geological history. The Machairodonts were also European in their birthplace, finding their way to North America at a later date. But although America at the present day has no feline larger than the Jaguar, it seems to have possessed - at any rate in north and northernmost America, as late as the Pleistocene - cats as large as the Lion and Tiger; in fact, in all probability, near relations of the Tiger. The Tiger would seem to be of Asiatic origin, and never to have reached Europe, but to have extended its range to Arctic Asia (where its bones testify to its existence at no very distant date, well within the Arctic circle, on the New Siberian islands), and perhaps across the former Bering Isthmus into Arctic and Temperate North America. The Lion, which like the Jaguar and Tiger sprang from a Leopard ancestor (from a stock chiefly rosetted and spotted, but also striped), is most at home - so to speak - in France. The most primitive and jaguar-like type of Lion hitherto discovered has been found in early Pliocene strata in Southern France, while the extremist development of the Lion type also came into existence in France - the Cave Lion, which extended its range over nearly all Germany, England, North Italy, Switzerland, and Austria. Its somewhat degenerate descendant, the modern Lion (differing only from its ancestor by its much smaller size) ranged far afield, into Spain, Africa, Western Asia, and India.

WHY ARE THERE NO SABRE-TOOTHS TODAY?

The various sabre-tooth cats and cat-analogues were adapted to hunting the mega-fauna that inhabited various continents until the end of the last ice age. Changes in climate and habitat (and possibly other factors such as human hunters and major viral illnesses) led to the extinction of the mega-fauna. When prey species goes extinct, specialised predators such as sabre-tooth cats also become extinct. Those that could adapt to hunting smaller, more agile prey (e.g. hoofed grazing animals) went on to become modern cats. The population levels of elephants, our largest land mammals, are probably too small to sustain a population of sabre-toothed predators. There is no need for modern big cats to evolve into sabre-tooth forms; it would expend energy on growing the huge teeth but gain no competitive edge over other predators.

The modern Clouded Leopard is the closest we have to a sabre-tooth cat. It has the longest canines proportional to body size of any of the modern cats - the length of the fangs in approximately three times greater than the width of the fang at the socket. The backs of the canine teeth are very sharp, like those of the prehistoric sabre-toothed cats. There is a large gap between the canines and premolars, enabling them to take large bits out of their prey. Given a few million years (if humans don't wipe it out) in which to evolve and the right selective pressures, Genus Neofelis could give rise to the next generation of sabre-tooths.

There are cryptozoological reports of sabre-tooth cats surviving to the modern day in remote areas. The Tigre de Montage (Mountain Tiger) of northern Chad is described as lion-sized, striped reddish and white, tailless (or bobtailed) and having huge projecting fangs. From a selection of images, the one chosen by a Zagaoua hunter was Machairodus, an African sabre-tooth officially extinct for the last million years. The region is remote, mountainous and not well-known in zoological terms. Similar tales have come from the mountainous regions of Ecuador, Columbia, and Paraguay in South America, a region that has harboured marsupial sabre-tooths and eutherian sabre-tooth cats. In 1975, a big cat with 12 inch fangs was apparently killed in Paraguay; it was officially identified as a mutant Jaguar and unofficially identified as a Smilodon (the carcass seems to have been lost, preventing further study). Without firm evidence, e.g. a fresh or living specimen, sabre-tooth cats remain officially extinct.

The photos below show a fossil smilodon skeleton displayed at the Natural History Museum, South Kensington, London. At its foot is a reconstruction.

|

|

|

|

|

CURRENT FELID CLASSIFICATION

There are 2 main schools of taxonomy - lumpers and splitters. In simplest terms, lumpers like to lump species together into fewer genera based on shared traits. Splitters like to split genera into multiple sub-genera or species (and species into sub-species) based on small differences. Until recently, classification was based on analysis of physical features to determine which species belonged where; with the pitfall of convergent evolution muddling the results. Recent DNA studies are giving a more precise picture of relatedness of species. As a result there are often several alternative taxonomies at genus, species and sub-species level! The following table is therefore a compromise.

|

GENUS |

SUB-GENUS |

EXAMPLE SPECIES |

|

Felis |

Felis |

European Wild Cat, Jungle Cat, Bay Cat |

|

Lynx |

Lynx |

European Lynx |

|

Neofelis |

|

Clouded Leopard |

|

Pardofelis |

|

Marbled Cat |

|

Acinonyx |

|

Cheetah |

|

Panthera |

Uncia |

Snow Leopard |

|

Unknown |

|

Onza |

FURTHER READING

|

MESSYBEAST : SMALL CAT HYBRIDS, BRITISH BIG CATS & PREHISTORY |