SAVING THE BURMESE - MOD DAENG’S LEGACY

This page is summarised from Nancy L. Reeves’ blog which will eventually disappear now that the author has died. Nancy was very instrumental in getting the outcrosses accepted. Supplementary information has been provided by Renee Weinberger (owner of Mod Daeng), Bonnie Brooks (Tonkinese breeder working with the new lines), and Nolan Betterley (who is working with native Thai cats in Thailand). I was asked to organise and preserve the information for posterity.

TERMINOLOGY

Nancy used the term Suphalak as a synonym for Burmese. This was a common mistake at the time. The Burmese is a sepia-pointed cat, though the Cat Fanciers Association call it “solid colour” Burmese. The Suphalak, as defined by Thai authorities, is a solid-coloured non-pointed cat. I have compromised by using the term “Suphalak/Thai Burmese” to preserve the author’s view and to correct the error. The closest Western analogue of the Suphalak is the Self Chocolate Asian Shorthair.

Because this article is internationally visible, I have had to use the term “American Burmese” for the benefit of those outside of North America where “Burmese” refers to the European Burmese. CFA refers to both sepia Burmese and sepia Tonkinese as “solid colour.” Most other registries define “solid colour” cats as non-pointed cats (i.e. non-sepia, non-mink, non-colourpoint). In the USA, the term “sable” is used for brown Burmese, while “champagne” is used for chocolate Burmese.

ADVENTURES IN THAILAND BY RENEE WEINBERGER AND J.D. BLYTHIN (EXCERPTS)

Dr. Leslie Lyons delivered a warning at the 2008 CFA Burmese breed council meeting about genetic diversity. She stated that the Burmese breed had the lowest diversity of all CFA breeds, and that we should look for solutions to this looming problem. One of her suggestions was to go to Thailand and import native bred cats. In February 2010, we made the journey halfway around the world to do just that.

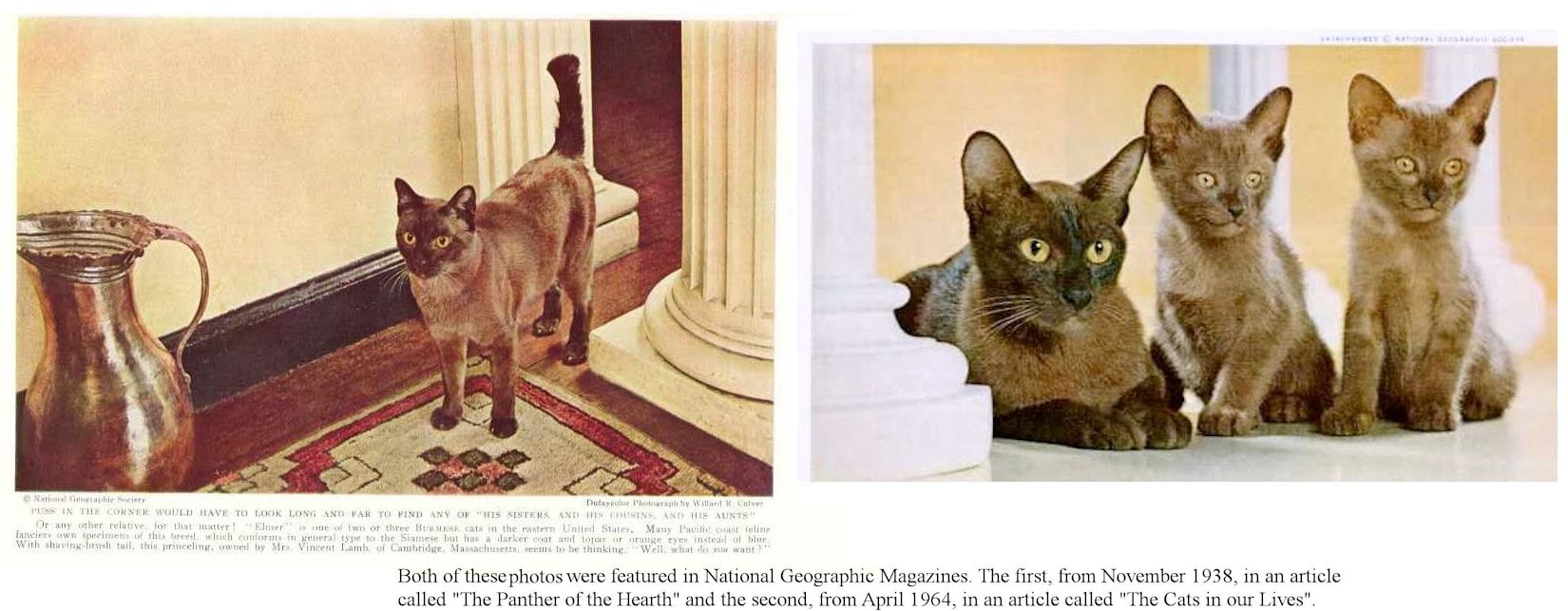

Before we got on the plane, we did a lot of legwork back home to line up contacts and plan our trip. We connected with Martin Clutterbuck, the authority on native Thailand cat breeds today. After a complicated interlibrary loan process, we received and read his book, Siamese Cats: Legends and Reality, many times! Martin's friend, Aree Yoobamrung, owner of Areerat Cattery, had a female kitten we might be interested in. Additionally we contacted Dr. Ed Rose, of Chiang Mai cattery, who had previously worked with western breeders of Korats, Siamese, Khao Manees, and European Burmese. Dr. Rose had an intact male he was willing to place with us. So, it looked like some great possibilities before we even left: an unrelated pair of Suphalaks! However, by December, we had learned that the male in Chiang Mai had passed away. Nevertheless, we packed along a second Sturdibag, optimistic we would find another native bred Thai Suphalak. Nancy Reeves offered to receive a cat shipped from Thailand and work to get it healthy for us. Unfortunately, we were not able to take her up on her offer, as we did not find any other eligible Suphalaks from Thailand other than that female kitten from Areerat cattery.

First a little background on the cats of Thailand. It is widely believed that the Burmese we know in the west came not from Burma originally, but rather came to Burma from Thailand. There are a series of ancient folding books in Thailand that were believed to have been originally written somewhere in the 14th-18th centuries. The books depict several ancient breeds of Thai cats: Thong Daeng, Ninlarat, Dork Lao, Maew Kaew, and other black and white cats.

The Suphalak is also known in Thailand as a Thong Daeng which in English means "copper" cat. This copper cat depicted in the manuscripts has become known to the west as the Burmese, although the Thais do not distinguish between sable solid and sable mink - both colors are "Suphalaks." (Siamese Cats: Legends and Reality, 2004). [2018: Suphalaks are non-pointed brown cats, but these were almost non-existent when Renee wrote this piece.] Cats have been imported and incorporated into the Burmese gene pool from Southeast Asia several times in the in the past. These cats were:

COPPER [THAI BURMESE] IMPORTS:

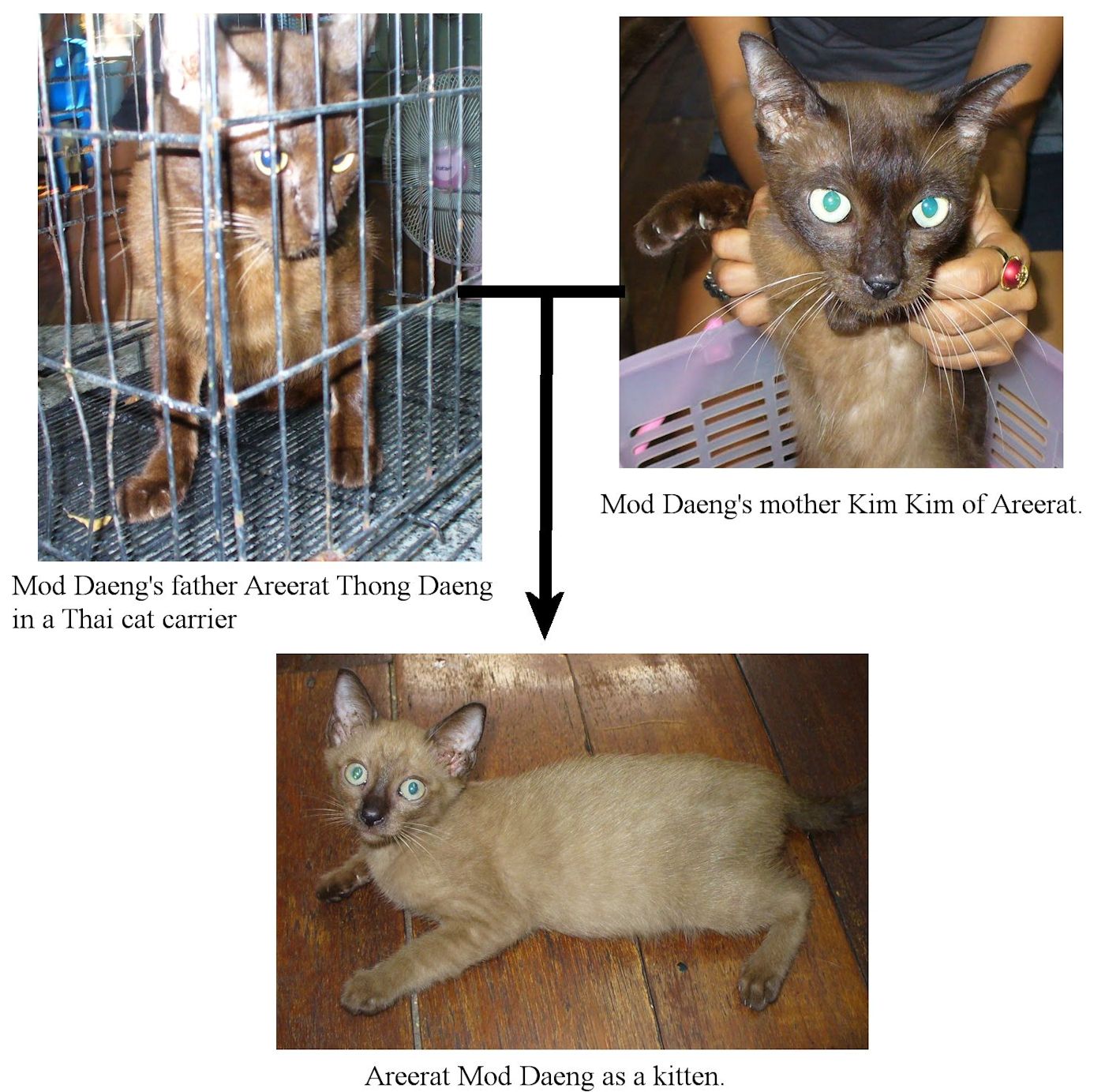

Wong Mau - Hybrid Female from Burma (likely a Sable Mink)

Tangyi of Forbidden City - Burmese Female from Burma

Ananda of Forbidden City - Burmese Female from Burma - did not reproduce!

Casa Gatos Biladi - Copper Male from Thailand

Chira Tan Tockseng - Hybrid Female from Singapore

Mahajaya Toffee of Bowbell - Copper Male from Thailand

Mahajaya Sai Thong of Pandit - Copper Female from Thailand

Mahajaya Nong Chai of Bowbell - Copper Male from Thailand

Lop Buri - Copper Male from Thailand

SIAMESE OUTCROSSES:

Minga of Yana - Seal Point Siamese Female

Ricki Tic - Seal Point Siamese Male

Resea Lee - Siamese Female

She Shan Mau - Siamese Female

Tai Mau - Siamese Male imported

Tai-Tai of Tang Wong - Siamese

Minkee of Chindwin - Seal Pt. Siamese Female

Mon Luan - Siamese Male

Chula Mia - Siamese Female

Bing Tse Ling of Ching Ming Tai - Seal Point Siamese Female

Before leaving for Thailand, we wanted to gather as much information as possible about how to find local breeders and how to safely and legally export cats from Thailand. We contacted Dr. Cristy Bird of Sarsenstone cattery in California, making her acquaintance through Nancy Reeves of Burma Pearl cattery. Nancy and Cristy had gotten to know each other through local TICA shows, and Cristy had edited Martin's book and written the last chapter! Dr. Bird was an invaluable contact, giving us all the nitty gritty information and a how-to guide on importing cats from Thailand, as she had done this task many times herself. It was from her that we knew where to go to get the export permits, how to get to the veterinarian's office, and a meeting with her good friend in Bangkok who literally helped lead us by the hand. She also prevented us from making some serious mistakes!

Our initial motivation to go the distance came from Erika Graf-Webster, who had originally invited Dr. Lyons to the breed council meeting. We stayed in contact with Erika after the meeting as she endorsed Dr. Lyons' suggestions and encouraged us to make the trip. She also helped with the initial legwork by contacting Dr. Rose and Martin Clutterbuck. Later we contacted the new breed council secretary, Art Graafmans, and presented our idea to him as well; he also fully endorsed Dr. Lyons' findings and supported our plans.

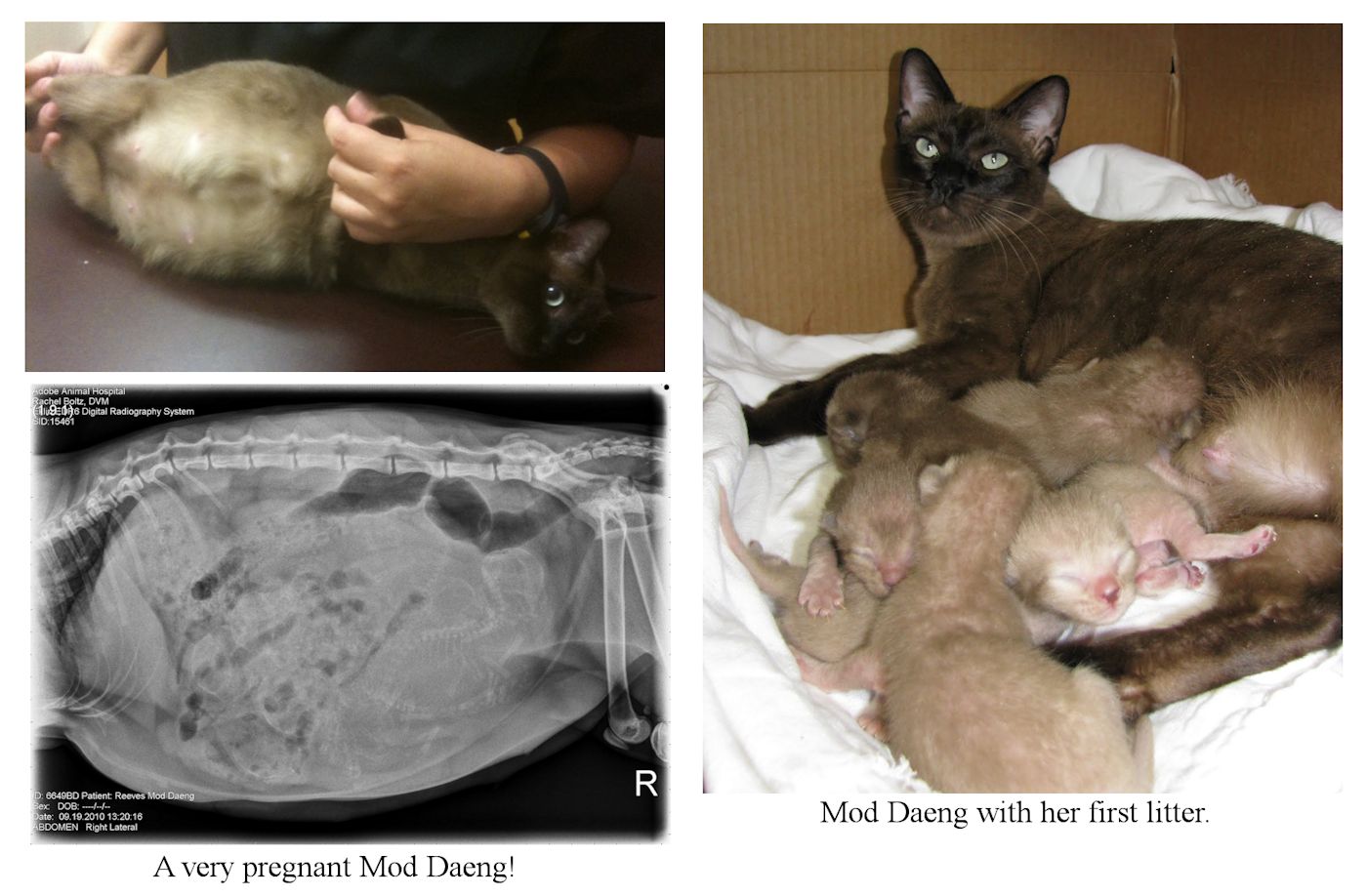

After a year and 8 months of discussing and thinking about such a trip, we made the voyage on February 9, 2010. In all, including the layover in Seoul and the lost time from crossing the Date Line, we arrived almost 48 hours after we left Chicago. On Saturday morning we met Martin [Clutterbuck] at our hotel. With Martin, we visited Areerat Cattery, which is also known as "The Siamese Cat Conservation Center." Mostly, Areerat cattery concentrates on Siamese cats, but they maintain a few representatives of the other Thai cat breeds mentioned in the text and the Khao Manee. There were two Suphalaks in the cattery, Thong Daeng, an eponymous male, and Kim Kim, a female. These were the parents of the kitten that we had been offered. Among the cats (mostly Siamese in color) roaming the house was this tiny little kitten named Mod Daeng. "Mod Daeng" literally translates as "Red Ant." It is also the name of a superhero in a local comic book for whom she is named. We also received as much pedigree information they had on her, which was only three generations on the sire's side and one on the dam's. While Mod Daeng was clearly a mink Suphalak with a long nose and some color faults (ghost stripes, but no lockets), her round head and eyes, straight tail, and impressive size for a girl of her age made her too promising to pass up. After we returned home, the Veterinary Genetics Laboratory at UC-Davis confirmed that Mod Daeng is sable, mink, and does not carry champagne or blue.

Martin explained that the Suphalak cats are waning currently in the local cat scene in Bangkok. Thai breeds wax and wane in popularity, and local breeders may have individuals from various breeds, depending on their situation, at any given time. Currently the Korat and the Siamese are the most popular Thai cat breeds, however the breed of cat for which they are best known worldwide is the Siamese. Another breed in Thailand is the Khao Manee, an all-white, sometimes odd-eyed shorthair cat. For a short while, there was a Khao Manee craze fueled by western breeders coming to Thailand looking for imports to start out a new breed in the western cat fancies. In fact, we learned from Martin, and later Ed, that a few western (mostly European) cat breeders had come to Thailand in recent years and exported Korats, Khao Manees, and Siamese. It was this group of western breeders, who were unequipped to deal with cultural differences and cat fancy differences, that soured many of the local breeders to dealing with westerners. And, in fact, many refuse to do so after bad experiences and poor treatment. Some of these cultural differences revolve around the fact that most western cat fanciers offer all sorts of guarantees on breeding cats. But, this is not common practice in Thailand among the cat fancy. Rather, we noticed that "caveat emptor" seemed to be the rallying cry of commercial sales throughout Thailand. Many times cats exported had diseases that proved fatal or never reproduced. Indeed, we were made fully aware that the cat we were purchasing was being sold "as is" with no guarantees or claims about her future health or fertility. This is the most important advice we have for anyone attempting to import cats from Thailand. Your actions and treatment of the people with which you deal will not only help or harm your ability to establish a working relationship; they will help or hinder others' ability to acquire outcross cats from Thailand as well. Please, learn about the culture before you go.

Later that day, we met up for lunch with Martin and Cristy's friend, who is heavily involved in the local rescue scene and is a journalist with one of Bangkok's English language newspapers, The Nation. We learned a lot about these cultural differences and some of the mistakes made in the past. We also learned that we should avoid seeking cats at the Chatuchak weekend market, where people can buy many types of animals including exotic and endangered species. Martin and Cristy's friend warned us that the animals are brought to the market by people who are far less than scrupulous and do not take care of their animals. We were told stories of westerners who had purchased Thai cats from the market, and discovered that they carried diseases like feline leukemia or FIV. Unfortunately, the western breeders felt that the local veterinarians should euthanize these animals, but in general Thai veterinarians do not perform euthanasia, as they do not agree with it on religious grounds. As a result, many unwanted cats are dumped on the local rescue groups, temples, and on the streets.

After lunch, Martin's friend accompanied Mod Daeng and us to Dr. Summalee's clinic, the same clinic where Roger Horenstein had vetted his exports in 1997. The clinic is at the foot of the Phrom Phong Sky Train station on Sukhumvit Road, one of Bangkok's main thoroughfares.Unfortunately, Dr. Summalee is not practicing much these days, and her partner runs the clinic. There, we had Mod Daeng tested for FIV and feline leukemia (both negative) and treated her with Revolution. She also received a rabies vaccination and a distemper, herpes, and calici vaccine. While these vaccinations are not legally required for cats entering the United States, rabies vax is required for exporting animals out of Thailand by the Thai government! The clinic also boarded Mod Daeng while we set out for Chiang Mai to visit with Dr. Rose.

We maintained our plans to visit Chiang Mai cattery in spite of the fact that the prospective male breeder had passed away. In the morning, we met Ed Rose, who drove us to his house and cattery. Ed and his wife Malee (who Ed says deserves much of the credit for his cats and success in general) have an impressive outdoor, enclosed cattery setup. Unfortunately, the Roses have retired from breeding and only had two elderly sable female Suphalaks remaining.

Upon our return to Bangkok, we contacted Martin and his friend again. As we had no further leads and were exhausted, we spend the remaining few days of our trip relaxing, shopping, and exploring Bangkok. We also recovered Mod Daeng from the vet clinic and clandestinely put her up at the swanky, five-star plus hotel (also much less expensive than an equivalent in Chicago) at which we were staying. Two days before our flight, Martin's friend connected us with a taxi driver who had experience driving cat exporters to the animal export office at the airport. As required by Thai law, we brought Mod Daeng and the paperwork provided by the vet to the export office. We filled out additional paperwork, and the government veterinarian examined Mod Daeng and issued the export license. While the license process is relatively simple, taking no more than an hour, the process is an unfortunate barrier to exporting cats. The Thai breeders generally will not obtain export licenses for purchasers. They expect the purchasers to do it themselves or to hire a shipping agent, which can be difficult and expensive.

Two days later we boarded our flight from Bangkok back to Seoul. After another long layover, although not as long as expected due to delays, we were on our way back to Chicago. Mod Daeng rode with us in the cabin, under the seat the entire way - no one even knew she was there. Upon arrival at O'Hare, two hours before we had left Seoul, Mod Daeng saw snow for the first time.

While we had a wonderful adventure in Thailand and have obtained a nice girl who will hopefully provide a positive benefit to the overall health of our chosen breed, we do not believe that imports from Thailand will, by themselves, solve our problems with genetic diversity. Even with all the generous help we received, we could easily have come home empty handed. Dr. Lyons also suggests that we would need to bring back at least one cat for several years in a row. If we want to create, improve and maintain working relationships with Thai breeders to create a constant stream of available cats, we will have to keep going back, and we will have to take turns absorbing the time and financial costs involved. This is not something that we, the authors, can do alone. We need to make a long-term commitment to the process or choose another source of outcross cats.

NANCY MEETS MOD DAENG

On Saturday, July 3rd 2010, Nancy Reeves first met a very special kitty - a little female who had travelled halfway across the globe from Bangkok, Thailand to Los Angeles. This special cat was Mod Daeng, Thai for "red (or copper) ant." According to Nancy, Mod Daeng was a Supalak, but Thai cat authorities point out that the Suphalak only occurs in solid chocolate with pink paw pads.

Suphalaks and natural Burmese were becoming increasingly rare in Southeast Asia at the time as breeders concentrated on Korats and Siamese, breeds popular in the west, and overlooked their native breeds. It was also difficult to establish long-distance relationships with breeders in Thailand who preferred to do business face to face. Obtaining a Thai cat from its native country and shipping it to the USA was a challenge. Thais are also wary of allowing their native cats to be exported overseas, bred to Western cats and made into a Western breed that claims a right to the original Thai variety name, and of their traditional breeds (identified in old manuscripts) being mis-identified by western fanciers.

Nancy was fortunate that Burmese breeders from the Midwest, Renee Weinberger and J. D. Blythin, travelled to Bangkok in February 2010 in search of Thai Burmese (which she called Suphalaks). Thanks to introductions through another breeder who has travelled many times to Thailand to bring Wichien Maats to the USA, Dr. Cristy Bird, and the author of the definitive history of Siamese cats ("Siamese Cats; Legends and Reality"), Dr. Martin Clutterbuck, Renee and J. D. acquired 8 month old Mod Daeng from the Areerat cattery in Bangkok and brought her to the USA. Mod Daeng stayed with Renee and J. D. during her quarantine period before moving in with Nancy.

Renee Weinberger notes in 2018, “At the time, when I went, I visited a breeder who was well-known in shows, etc, and that's what he called them. He has since quit. That was Khun Aree Yombamrung and his daughter Arreerat who was being translated for me by Martin Clutterbuck. Martin Clutterbuck's book defines Suphalak like Khun Aree did. The people that Nolan Betterly are working with, who he is translating for, are calling a different colour cat Suphalak.”

Nolan Betterley agrees that it is important to document what the general thought was at that time. He adds that Khun Aree was not the only one using that terminology in 2010, hence this was the description that made it into Martin Clutterbuck's book. However, if Khun Aree saw one of the Suphalaks of today he would agree that his cats in 2010 was not 100% Suphalak, more like 80% Suphalak and still working toward the solid brown colour mentioned in the poems. In 2010 nobody had achieved that goal. Kamnan Preecha managed to breed solid-looking sable Burmese, by selectively breeding away from the sepia pattern until only a slightly darker mask remained, but by 2018 there were cats in breeding programmes that better matched the descriptions in the poems. Strangely, the Thai manuscripts do not describe the Burmese, so Thai breeders just call them Thai Burmese, which fits alongside the classification of American Burmese and European Burmese.

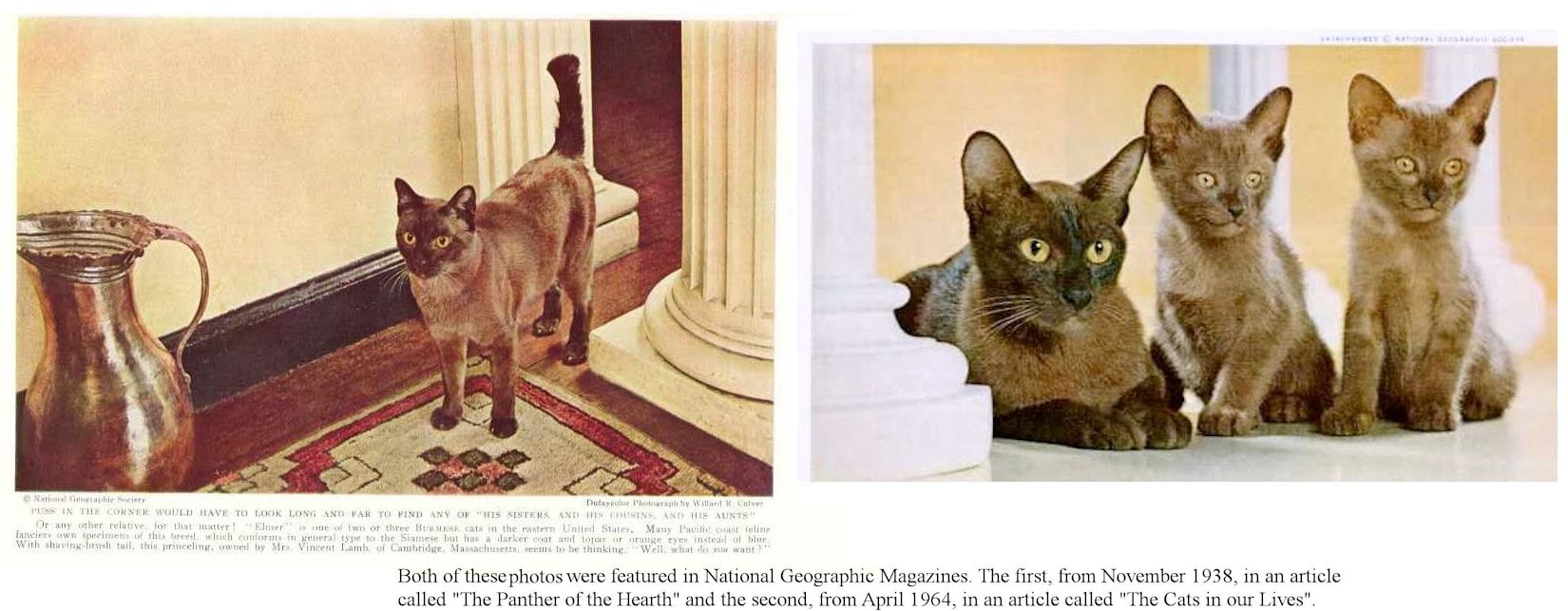

Mod Daeng went to the USA to improve the genetic diversity of the American Burmese cat. That breed became very inbred when fixing its conformation. Breeders in favour of reinvigorating the breed sought fresh blood from Thailand because all Burmese outside of Southeast Asia, are descended from a single female cat, Wong Mau, taken from Burma to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1930. Wong Mau’s owner, Dr. Joseph Thompson, believed she was a new breed of cat and worked with geneticist Billie Gerst, from Palo Alto, California, to develop the breed. Breeding records show that Wong Mau was actually a mink-pointed cat, now known as a Tonkinese. According to Nancy, Thai Suphalaks were bred for hundreds of years in both sepia (Burmese colour restriction) and mink (Tonkinese colour restriction). This is incorrect according the Thai authorities - the Suphalak is a non-pointed cat. DNA testing showed that Mod Daeng was also a mink.

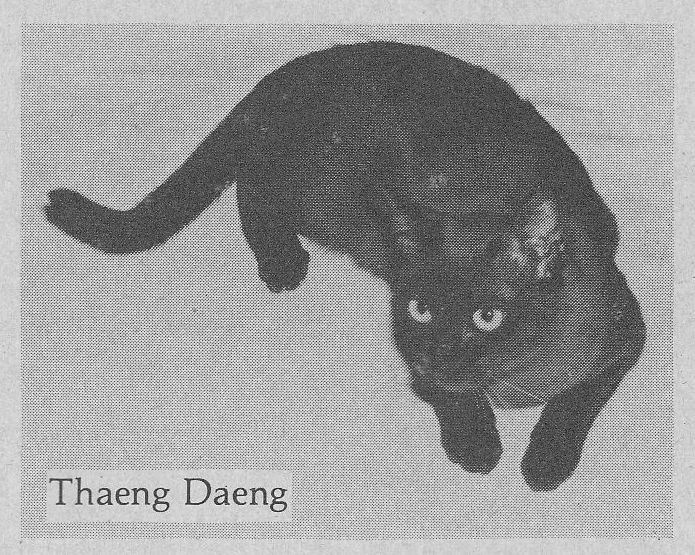

Two more imports were made into the USA in 1974 “Two rare native Thai Cats have been imported into the U.S. by Dr. Rosemonde S. Peltz and Mrs. Anne E. Bickman,; both of Atlanta/Georgia. The two kittens, Thaeng Daeng and Maha-jaya Chatopoh, were the result of four years of negotiations between Dr. Peltz and Mme. Ruen Rajniaitri of Bangkok. [...] Dr. Peltz, a member of the CFA board of directors, hopes the cats will be recognized by the association as Burmese, and subsequently provide another bloodline for the Burmese breed in the U.S. The two kittens will be on exhibition at the Atlanta Phoenix Cat Society's championship show on March 9 and 10, 1974. The show will be held at DeKalb College's gymnasium on Memorial Drive, east of 1-285 in Atlanta. (Pictured: Thaeng Daeng.)” (Copper Cats in Atlanta – Cat Magazine, March 1974

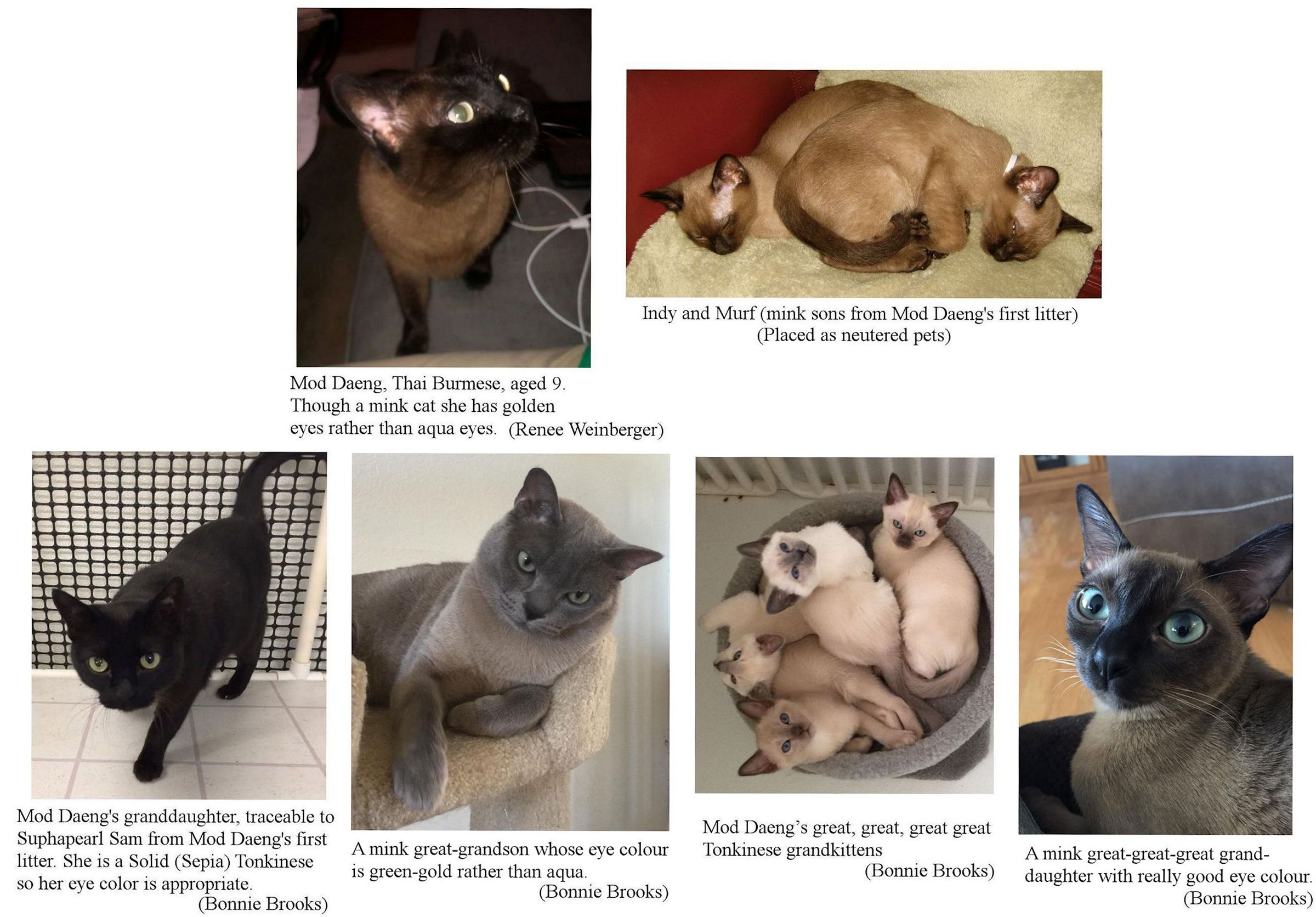

Art Graafmans, Cat Fanciers Association (CFA) Burmese Breed Council Secretary, took Mod Daeng to Southern California from the CFA Annual Meeting in Minnesota at the end of June. Nancy first met Mod Daeng at Art’s home. It wasn't hard to identify Mod Daeng when she first saw her, but she was surprised by several things, including her size for her age: though a few months short of a year old she was nearly eight pounds. This was good news because the American Burmese females had become petite due to a few decades of inbreeding. Decreas in size is a known result of inbreeding depression so Mod Daeng's size boded well for helping restore that to the American breed. Nancy had expected the long nose and narrow muzzle, but was particularly taken by her eyes. They were large and round, as Americans liked in the Burmese, but their pale colour was almost startling in the dark mask of her face. Their colour seemed to change slightly as she turned her head, sometimes appearing more greenish, other times gold. Because of her mink colouring, technically her eyes were aqua and, like hazel eyes in humans, Mod Daeng's eyes seemed to change colour with different angles and light.

Art and Nancy spent the afternoon talking about the United Burmese Cat Fanciers (UBCF) newsletter, which Nancy edited, after which Nancy and Mod Daeng travelled back to Northern California on a Southwest Airlines flight. Mod Daeng was quiet for most of the trip, though towards the end she got tired of being confined in the carrier and clawed a bit at the sides. Back home, Nancy put Mod Daeng in a freshly cleaned, large isolation cage while she adjusted to her new environment. She was known to be a healthy cat, as she had been through several tests and treatments before she even left Bangkok.

THE CASE FOR OUTCROSSING, PART 1

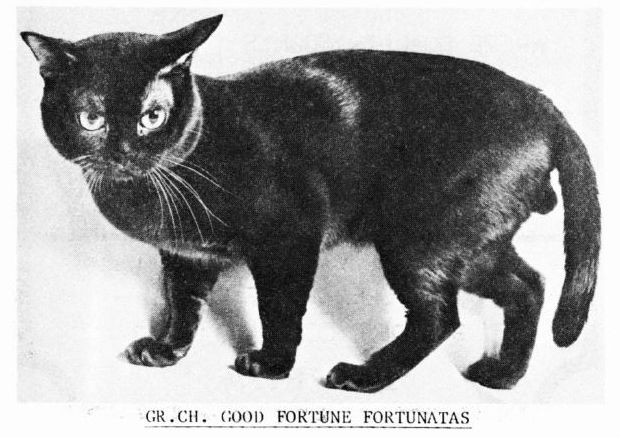

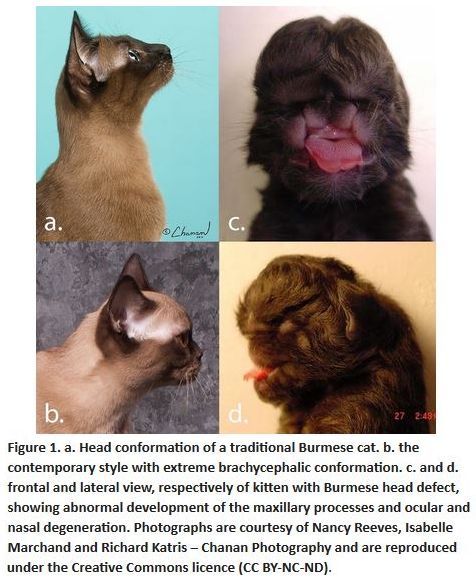

The American Burmese community had long been divided into “contemporary” (round-headed, cobby bodied type) and “traditional” (less extreme type) camps and into pro- and anti-outcrossing factions. The “anti camp” feared a loss of type, the “pro camp” feared a terminal loss of vigour. Dr. Leslie A. Lyons' 2008 study of the genetic diversity of cat breeds should have been a wake-up call to American Burmese breeders. Dr. Lyons made recommendations on how to restore diversity. She pointed out that modern cat breeds had been developed within a very short time, most in the last 100 years. The American Burmese was developed from only a few foundation cats and a further bottleneck occurred in developing the “contemporary” Burmese lines, all of which trace back to one cat, Good Fortune Fortunatas. The original mutation occurred in his ancestors, but he was responsible for it becoming widespread. Since then, there had been little outcrossing, except to save the breed from the lethal “Burmese Head Defect” (BHD, or simply HD). When Contemporary Burmese were bred together, a craniofacial defect appeared in 25% of offspring. It was inherited as an autosomal recessive, but carriers of the mutation are more brachycephalic than non-carriers and were positively selected for in the breed. Because carriers are visually identifiable, the trait is also described as co-dominant (or as dominant with additive effect). Affected kittens were generally born live, but had to be euthanized because the condition is incompatible with life. The heterozygous (gene carrier) cats became the standard phenotype of the breed and the predominant winners at cat shows.

The Burmese craniofacial defect, or median cleft syndrome, is scientifically known as Frontonasal Dysplasia (FND3) and is associated with a mutation of Aristaless-Like Homeobox 1 (ALX1). Studies demonstrated that it is a simple co-dominant trait i.e. it inherited recessively; carriers have a desirable (in breed-defining terms) modified head shape, but homozygotes are lethally affected. A mutated ALX1 gene is present in affected Contemporary Burmese and absent from unrelated cats with brachycephalic features.

Meanwhile Suphalaks and Thai Burmese had existed for centuries and had a wide genepool because in Thailand, there is a single conformation, and what Western breeders think of as "breeds" (Siamese, Korat etc) are just colour varieties of the native Thai cat. The different colours can be freely crossed and then given the name of their phenotype.

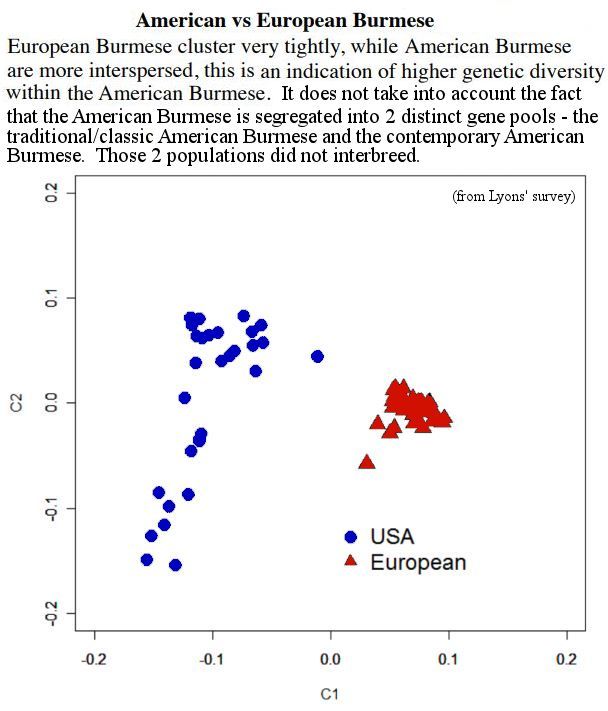

The inbreeding coefficient based on the observed vs expected number of homozygous genotypes in each sample are 0.38 for US Burmese, and 0.41 for European Burmese. On the chart, the European Burmese cluster very tightly, while American Burmese are more interspersed, this is an indication of higher genetic diversity within the American Burmese. However this didn’t reflect the fact that the “contemporary” and “traditional” (or “classic”) Burmese gene pools were isolated from each other in the USA (a situation that ended when a test for head defect carriers became a vailable)! The study identified cats from Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Brunei and the Philippines as good genetic candidates for outcrossing.

Geneticists have long known that species with low genetic diversity are at greater risk of infertility, poor immune system and other health issues. Cheetahs are an example of an extremely inbred species due to a genetic bottleneck approximately 10,000 years ago. DNA analysis shows that all cheetahs are descended from one female and her cubs. In cheetahs, ruthless natural selection has countered this, but cat breeders select for looks, not for “fitness to survive.” The inbreeding of the Burmese exacerbated known health issues including the Burmese craniofacial defect, GM2 gangliosidosis, FIP, Burmese hypokalaemia, Feline Orofacial Pain Syndrome (FOPS), diabetes, high triglycerides, endocardial fibroelastosis, midline closure defect, dermatosparaxis (cutaneous asthenia, stretchy skin), flat chested kitten syndrome (FCK), gingivitis/stomatitis, diabetes, and dilated cardiomyopathy.

Some breeders were more concerned about the reintroduction of the more foreign type and longer nose than the long-term genetic health of the breed. In TICA, some American Burmese breeders had already crossed their cats with the more genetically diverse European Burmese lines, and had reported larger litters and larger, more vigorous kittens as a result. Reducing the number of generations before non-CFA cats with European lines could be registered in CFA would also improve genetic diversity. There were already two Burmese-derived breeds recognized in CFA that would be logical outcrosses: Solid (i.e. Sepia-point) Tonkinese and Sable (solid black) Bombays. By way of comparison, the Korat population was even smaller than the American Burmese population, but Korat breeders imported fresh blood from Thailand every few years to maintain the health and genetic diversity of the breed. Nancy felt that Burmese breeders should learn from that lesson and follow suit. While no individual Burmese breeder would be compelled to outcross, denying outcrosses to the breed as a whole would result in continued deterioration of genetic diversity, health, and fertility.

THE FIRST OUTCROSS KITTENS

Mod Daeng had all the personality characteristics of the American Burmese. She was fearless with people and always ready for attention and fuss. Her purr was loud and readily offered, and she loved to roll on her back for a belly rub. She was softly talkative with humans and took a keen interest in what was going on around her. She particularly loved fish in her diet, rice and fish being part of the feline diet in Thailand. On the 22nd of July 2010 it was obvious that Mod Daeng was in heat. She was large enough and mature enough to breed so she was introduced to Nancy’s champagne (chocolate sepia) boy, Bear Country's Alan Parsons Project , and they mated within a few minutes of meeting. Testing had shown that Mod Daeng did not carry chocolate.

Less than a week before Mod Daeng was due to have her babies she went to the vet, Dr. Rachel Boltz at Adobe Animal Hospital in Los Altos, California for an x-ray. There were five, possibly six kittens visible – all large. The heavily pregnant Mod Daeng weighed nearly twelve pounds. Though not fully grown, she was considerably larger than Nancy’s other Burmese females, and was even larger than the stud male. Two days before her scheduled due date, Mod Daeng surprised Nancy by producing six vigorous babies early on Wednesday, September 22, 2010. She’d given birth without any problems and was an exemplary and protective mother. Unlike many American Burmese with large litters, Mod Daeng‘s kittens did not need supplemental feeding.

At a few weeks old, some of the kittens looked very much like American Burmese kittens while others had longer noses and profiles. All six thrived and Mod Daeng continued to be an attentive mother. Some were obviously mink, but seemed to have gold eyes rather than aqua eyes or the pale gold/aqua eyes of their mother. American Burmese cats are sometimes called "bricks wrapped in silk" and this description suited Mod Daeng's kittens, who were surprisingly heavy for their size. They were also very human-oriented. Nancy described the kittens’ personalities and looks.

Song was the biggest and a devoted shoulder-rider. Nueng seemed to have the best head, but not the best coat – it was a bit light and fluffy -- and he had a little tail fault on the tip of his tail. Sam and See were very much alike -- both had short, dark coats, but their muzzles were narrower and their ears bigger than Nueng. Har was a mink, but had the scratchy voice of the American Burmese. Hok was the smallest, but had a very big personality. Their father, Bear Country's Alan Parsons Project was a Champagne (Chocolate Sepia) male about three and a half years old with a sweet personality. Nancy called him "The King of Drop and Roll" because would drop and roll frequently and without warning and expose his belly for petting. Many of his kittens inherited his cuddly nature and the "Drop and Roll" trait . Would the outcross kittens also inherit this trait?/P>

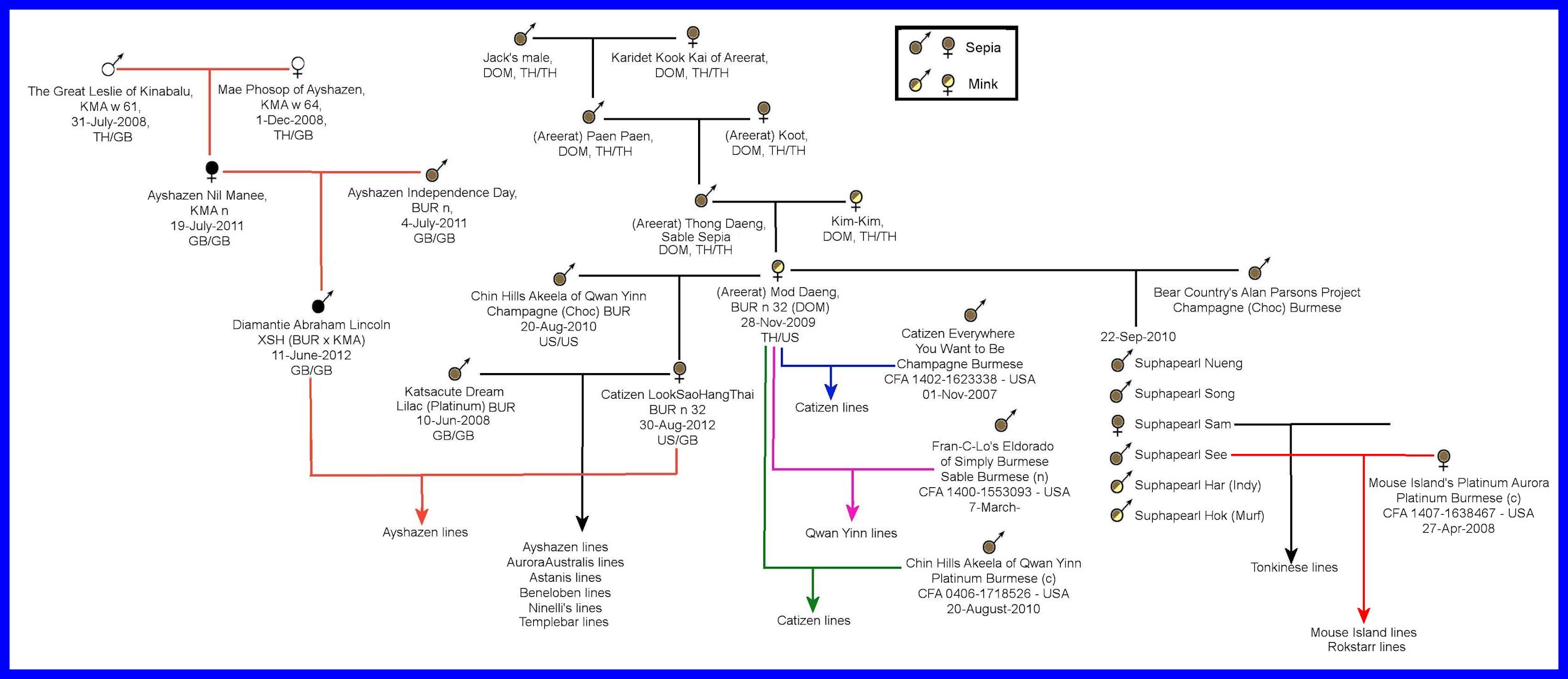

Just before Thanksgiving 2010, Mod Daeng, her six kittens, Bear Country's Alan Parsons Project, Gray Mark's Agate of Burma Pearl ("Aggie"), Lois True, and Nancy drove up to UC Davis where the kittens would have swabs taken for parentage, colour testing, and for research. The kittens would also be microchipped. Nancy had registered a new cattery name in TICA, and planned to do the same if/when Mod Daeng was registered in CFA, in order to identify cats bred from Thai import lines. Her American Burmese cattery name was “Burma Pearl” (CFA) and “Burmapearl” (TICA). At that time Mod Daeng was believed to be a Suphalak so the new cattery name was Suphapearl. The kittens’ registered names were: Suphapearl Nueng (nueng is number one, male, sepia), Suphapearl Song (song is number two, male, sepia), Suphapearl Sam (sam is number three, female, sepia), Suphapearl See (see is number four, male, sepia), Suphapearl Har (har is number five, male, mink), and Suphapearl Hok (hok is number six, male, mink).

Leslie Lyons discussed the American Burmese breed and the Head Defect with Nancy (with an audience of about half a dozen of Leslie’s students) and how to improve genetic diversity, something already happening with the Korat breed through outcrossing to Thai imports. They compared Mod Daeng's look to 21st century American Burmese like Alan Parsons Project or Gray Mark's Agate, and discussed the challenge of attaining that look in Mod Daeng's descendants without losing the greater genetic diversity. In due course, the DNA tests showed that Suphapearl Har and Suphapearl Hok were minks and the rest were Sepias. All carried brown, inherited from their father, but none of the kittens carry the dilute allele as neither parent carried this.

THE CASE FOR OUTCROSSING, PART 2

Nancy was a dedicated "traditional" Burmese cat fancier, breeder, exhibitor, and advocate of over 20 years’ standing, and a breeder for more than half of that time. On several occasions prospective clients (carefully screened before meeting the kittens) rejected her beautiful healthy kittens on sight because the kittens' noses were too short. Didn't she have any with longer noses, they asked? Those clients wanted the look of the Burmese they had known and loved for ten, twenty years and more; the look of the original cats. In the eighty years since Wong Mau had arrived in the USA, her descendants had spread all over the world, but their head shape had changed dramatically. In particular, the noses had become much shorter.

Arguably, no other fancy breed had experienced the rapid and dramatic change that occurred within the American Burmese breed, a change caused by a lethal genetic mutation. Some believe it was a spontaneous mutation in the breeds. Others feel it arose concurrently with the development of Exotics, when short-nosed Persians were bred to Burmese. Regardless of its origin, no one disputes the fact that a genetic mutation occurred in the late 1960s to early 1970s that profoundly affected the breed and literally changed the face of American Burmese cats. A magnificent-looking male named “Good Fortune Fortunatas” epitomized the new "contemporary" look. He had a broad rounded head, short nose, enormous gold eyes, stocky body, and a lustrous sable coat. He achieved great success in the show hall, and was in huge demand as a stud. His offspring quickly spread across the country and were equally success on the show circuit. His descendants were bred together, but around 25% of the “contemporary” Burmese kittens were deformed – born alive, but not viable outside of the womb. This was the “Burmese head Defect,” (BHD, or simply HD) a lethal "cranial facial mutation" that breeders are still trying to eliminate while retaining the contemporary look. Some breeders chose to continue breeding the carriers of this lethal defect, as they preferred the new look of the cats and the surviving kittens were successful on the show bench. Others either did not like the new look, or they liked it, but believed it was wrong to deliberately perpetuate a gene that produced deformed kittens with no chance of survival.

When Fortunatas and his progeny first appeared in the show hall, their conformation was well suited to the Burmese standard, hence they achieved high honours. When judges learned that the new phenotype carried the head defect, they could have made a stand against the continuation of a lethal gene in a breed, especially as it was linked to an easily identifiable phenotype. Unfortunately, they didn’t. They continued to award prizes to cats that carried the lethal gene. To this day, responsible breeders – those concerned with welfare and health, not just with prizes - are still trying to undo the damage. To produce competitive show cats, traditional breeders used selective breeding to produce cats with rounder heads and shorter noses that resemble the “contemporary” look, but without the lethal mutation. Only slight differences remain in the "looks" of traditional and contemporary cats, and they are increasingly subtle. When Nancy wrote about this there were no DNA tests for the Burmese Head Defect.

Since 2007, Nancy had registered and shown her cats in TICA as well as in CFA. In CFA in 2009-2010, five out of the six top cats (Kittens, Champions and Premiers for the Sable and Dilute Burmese Divisions) were contemporary cats, and four of those top cats were from a single contemporary cattery. By contrast, in TICA all three of the top Burmese (Kitten, Champion, and Alter) were from a single traditional cattery. For the remaining top 10 placements, contemporaries dominated in CFA, while traditional and European Burmese catteries and cats dominated in TICA. In general, TICA judges did not support the extreme Burmese look preferred in CFA, although TICA judges were not always aware which cats were contemporaries and which were traditionals – the signs are there, but are subtle.

While Good Fortune Fortunatas may not have been the originator of the mutation that created the contemporary Burmese, research shows that he was the genetic bottleneck. Every contemporary cattery can trace their cats back to Fortunatas. Whatever concurrent contemporary lines may have existed in the past, they were all been brought together through him. This is known because a member of UBCF spent several years analysing records, and using reverse pedigrees to identify the registered descendants of Fortunatas. When this research was completed in 2009, it had identified more than 5,000 Fortunatas descendants in the United States and more than 3,000 in Europe. The study showed Fortunatas descendants behind a few traditional Burmese lines as well. A study by Dr Chris Helps at Langford Veterinary Services showed the prevalence of the head defect mutation in European and UK Burmese to be around 1% (in the UK, the GCCF prohibited the use of American Burmese because of the lethal gene). In the absence of DNA testing, if the gene(s) producing the head defect were simple recessives, then it can be bred out through careful matings and pedigree management. If the lethal gene cannot be bred out, then the database of potential carriers is useful for those wishing to identify which cats they should test for the lethal gene and, if the test is positive, eliminate from their breeding programmes.

REGISTERING MOD DAENG

How would Mod Daeng and her offspring be registered? In Autumn 2010, active members of the CFA Burmese Breed Council had a ballot containing a proposal to register Mod Daeng. If approved by a majority of council members, it would be forwarded for confirmation by the CFA Board of Directors at their February 2011 meeting. Then her registration would be issued. There were precedents for this action. This same process was used for Thai imports for the Burmese breed in the 1940s, in 1974, and in 1997. Several of those imports, especially Mahajaya Toffee, were behind a significant percentage of the existing Burmese gene pool. Once Mod Daeng received a registration number, then her offspring would also be registered as long as the sire of the offspring and their descendants were CFA registered Burmese. Thai imports in the past were successfully integrated into the American Burmese -many American Burmese today still trace back to Mahajaya Toffee.

In TICA you can incorporate a cat without a known pedigree into a particular breed as long as three judges agree that the cat is suitable for use in that breeding programme. In July 2010, at the Mid Pacific Regional show in San Jose, Nancy Reeves, Dr. Cristi Bird and Kathryn Amann introduced Mod Daeng to a number of TICA judges and got the three signatures needed to register Mod Daeng as an F1 or "Foundation" Burmese. Her offspring would be registered as F2s, her grandchildren as F3s and could be exhibited, but not compete, at TICA shows to show how the breeding programme was progressing. At the F4 generation --Mod Daeng's great grandchildren - they will be allowed to compete in TICA shows.

Could Mod Daeng's mink offspring be registered as Tonkinese? Mink is not a recognised Burmese colour. All Mod Daeng's sepia descendants were registered as Sable Sepia Burmese in TICA, and were allowable outcrosses for both Tonkinese and Bombay breeders should they wish. At the time CFA required eight generations of Burmese-to-Burmese breeding in order to accept a cat from another registry. Assuming a best case scenario of one generation each year, the soonest that would happen was 8 - 10 years’ time, meaning CFA registered Burmese would not benefit from Mod Daeng's fresh genes for at least a decade. Luckily CFA Burmese Breed Council approved registering Mod Daeng in CFA and also approved reducing the number of generations from eight to five when transferring Burmese from other registries. This also allowed breeders to use outcrosses to European Burmese.

Mod Daeng's four sable offspring, all male, would be registered – and competing - in CFA. The one with the best confirmation had a tiny tail fault, but the CFA Breed Council had previously voted to change the tail fault from “disqualify” to “penalize.” The sable boys would also be register in TICA, but as exhibition only because the American Burmese was defined as “Established Breed” and outcross descendants could not be shown for four generations. If TICA changed the Burmese to a “natural breed” in TICA future Thai imports could be registered immediately without the multi-generation registration requirement. After all, the Thai Burmese had existed for hundreds of years in their native Thailand.

THE CASE FOR OUTCROSSING, PART 3

In 2008, Dr. Leslie A. Lyons, then at the University of California, Davis, had published her landmark study analysing the genetic diversity of cat breeds. This showed that the cat fancy breeds with the lowest genetic diversity were the Burmese and Singapura. The study samples for Burmese were a combination of traditional and contemporary cats. Because of the cranial facial mutation that has divided the Burmese community, those two breeding populations are in actuality two distinct gene pools - the genetic diversity of the Burmese cat is even lower than Dr. Lyons' research showed. (In 2016, a study suggested the frequency of HD+ (heterozygous carriers) was 5.7% of the Burmese population (Lyons et al 2016)).

For years Burmese breeders had waited for a test to identify the gene(s) responsible. But if the genes involved were shown to be inextricably linked to the distinctive phenotype created by the cranial facial mutation gene, would all contemporary breeders be willing to give up the look they like, the show hall success they enjoy, and the long term investments they have made in their breeding lines? Would they be able to put welfare first? Not until 2014 would a genetic test become available for carriers of the Burmese head defect, so breeders needed to bring in genetic diversity from healthy imported cats that had never interbred with cat show Burmese. Once a test became available, contemporary cats could be screened and breeders began to ross the traditional/classic Burmese with the contemporary Burmese. Even the GCCF lifted their wholesale ban on using American lines.

CFA did not allow any outcrosses for Burmese, not even to cats that were genetically Burmese but were categorized in different "breed" divisions: European Burmese, Solid (i.e. sepia) Tonkinese, and Sable Bombays. In TICA, however, European Burmese, American Burmese and Sable Bombays could be bred together, hence Nancy joined TICA to be able to outcross to these. Many Burmese breeders wanted CFA to allow outcrossing to breeds that are genetically Burmese. Exactly where that discussion would lead was uncertain at the time but there logical options included reducing the number of generations before cats from other registries that have incorporated European or Sable Bombay lines could be brought into CFA, or planning and requesting a CFA outcross program that included Solid (sepia) Tonkinese and Sable Bombays. The other option was importation of fresh blood from Thailand, where the cats probably originated despite their name.

Contemporary breeders would probably be interested in Sable Bombays for outcrosses as most Bombays are contemporary in conformation. Traditional breeders would probably prefer Solid (sepia) Tonkinese because they are unlikely to be HD+. European Burmese in CFA were unlikely to be available as an outcross because their breeders had worked hard to create this as a unique breed in CFA. But outcrossing to European Burmese from other registries was feasible as long as the number of generations before they could be brought into CFA was reduced. Nancy did not identify the Asian Shorthair – a European Burmese relative – as a possible outcross as these were not found in the USA. The look of the American Burmese would change temporarily in the first outcross generations, but this had to be weighed against the breed’s long term health. Plus there were cat lovers who preferred the longer noses in their pets.

A very significant event for Burmese cats occurred in February 2010, when the CFA Board of Directors voted to combine the Sable and Dilute Burmese Divisions into one breed, following an affirmative vote for that combination by members of the CFA Burmese Breed Council. While this was long overdue and was ultimately the right decision, it was still shocking and upsetting to many traditional breeders. Traditional HD- (non-carrier) Burmese had made great strides towards the preferred conformation, and some of those cats had won high awards in CFA, but primarily in the Dilute Division. With the Sable and Dilute divisions combined, and in a world where contemporary HD+ sables tended to dominate, success for the head defect negative would be an uphill battle. While the CFA decision to combine the divisions seemed a disadvantage for the breeders of traditional HD- Burmese, it was an opportunity to educate the world - educate judges, fellow cat fanciers, and the general public - about their HD- cats and why it was so important to support traditional cats for the genetic health of the breed.

OTHER OUTCROSS PROGRAMMES

Prior to Mod Daeng, the US Burmese cattery, Carmelkats, had received two females from Thailand, from airline stewardesses no longer able to keep them because of being assigned to a new route and needing to move apartment. This meant Carmelkats would spend about 7 years working to introduce the diverse outcross genes to reach the number of generations of Burmese-to-Burmese breeding before they could show Burmese again.

An programme that began after Mod Daeng was at Ayshazen cattery in the UK which imported Thai Burmese to diversify the European Burmese gene pool. Known Thai Burmese imports contributing to European lines were Suay Valentian (tortie), Mook Dta of Ayshazen, Nam Dtan of Ayshazen, Amina of Ayshazen, Nyaung Shwe, Thong Thae, and Uhm Noi

MOD DAENG MOVES HOUSE

On Friday, February 4, 2011 Nancy bade farewell to Mod Daeng and delivered her to Art Graafmans, the CFA Burmese Breed Council secretary. Nancy had been a temporary home. Art delivered Mod Daeng to J.D. Blythin. The next morning, at the CFA Board of Director’s meeting, Mod Daeng was in attendance as the board discussed how to register her and her kittens. Art Graafmans submitted a report to the Burmese Breed Council. The proposal to reduce the number of generations required to bring a cat into CFA from another registry was passed unanimously. CFA now only requires 5 generations. However, the ballot proposal to register Mod Daeng as a sable Burmese was rejected and replaced with the following:

1. Mod Daeng may be registered in the CATS registry as a native Thai foundation Burmese.

2. Mod Daeng may be bred to CFA registered Burmese and the offspring may be registered as Burmese with the stipulation that they be genetically tested as cbcb (Burmese colour dilution).

3. The offspring which test cbcs (mink pattern) may be registered in the CATS registry as F2, F3, F4...foundation Burmese. They cats may be bred to CFA registered Burmese with the same stipulations as Mod Daeng.

This revised proposal was passed with only one dissenting vote. This would be the first time CFA used a genetic test as part of a registration requirement and they were applauded for requesting the test.

After the meeting, Mod Daeng went to her permanent home with J.D. Blythin and Renee Weinberger and almost immediately went into heat. Her second litter also totalled six babies, this time five girls and a boy, three being sables and three being minks.

Meanwhile, the TICA rules on imported Thai Burmese are as follows:

1. Three judges to certify cat is of Burmese type. Can be mink or sepia. Cat will then be registered as Burmese on the Foundation register.

2. Cats/kittens bred back to Burmese cannot be shown until 4th generation, but are registered as Burmese. Foundation cat 01T, then 02T, 03T then SBT championship status.

3. Only sepias can be shown after SBT.

Neta Cox became the owner of Suphapearl Sam and did all the work to get the generations to CFA registrable status. Unfortunately, Neta passed away in December 2017, but she dispersed Mod Daeng’s three great grandkittens to other Tonkinese breeders.

Two males from Mod Daeng’s first litter, Suphapearl Har and Suphapearl Hok, went to their forever home on December 23, 2010 and were renamed Indy and Murf. Their new owners were not fans of short-faced American Burmese had wanted the old-style American Burmese with the longer faces. Although they had wanted sables, the original Burmese colour, they fell in love with two mink kittens. Within five hours the kittens were asleep on their new owners’ laps and within a few nights they were on – or even in – their owners’ bed. They were described as 100% Burmese in every way. Their owners also had a 14 year old spayed calico female, Orangie, who became a second mother to the kittens, washing them and keeping them in line. When the kittens first met Orangie Indy went over to her and very respectfully did a drop and roll submissive approach (a trait inherited from his father), while Murf took one look and decided Orangie was his Mommy! The kittens also proved to be the most intelligent Burmese their owners had owned which raises the question “Has intelligence also suffered due to inbreeding?“