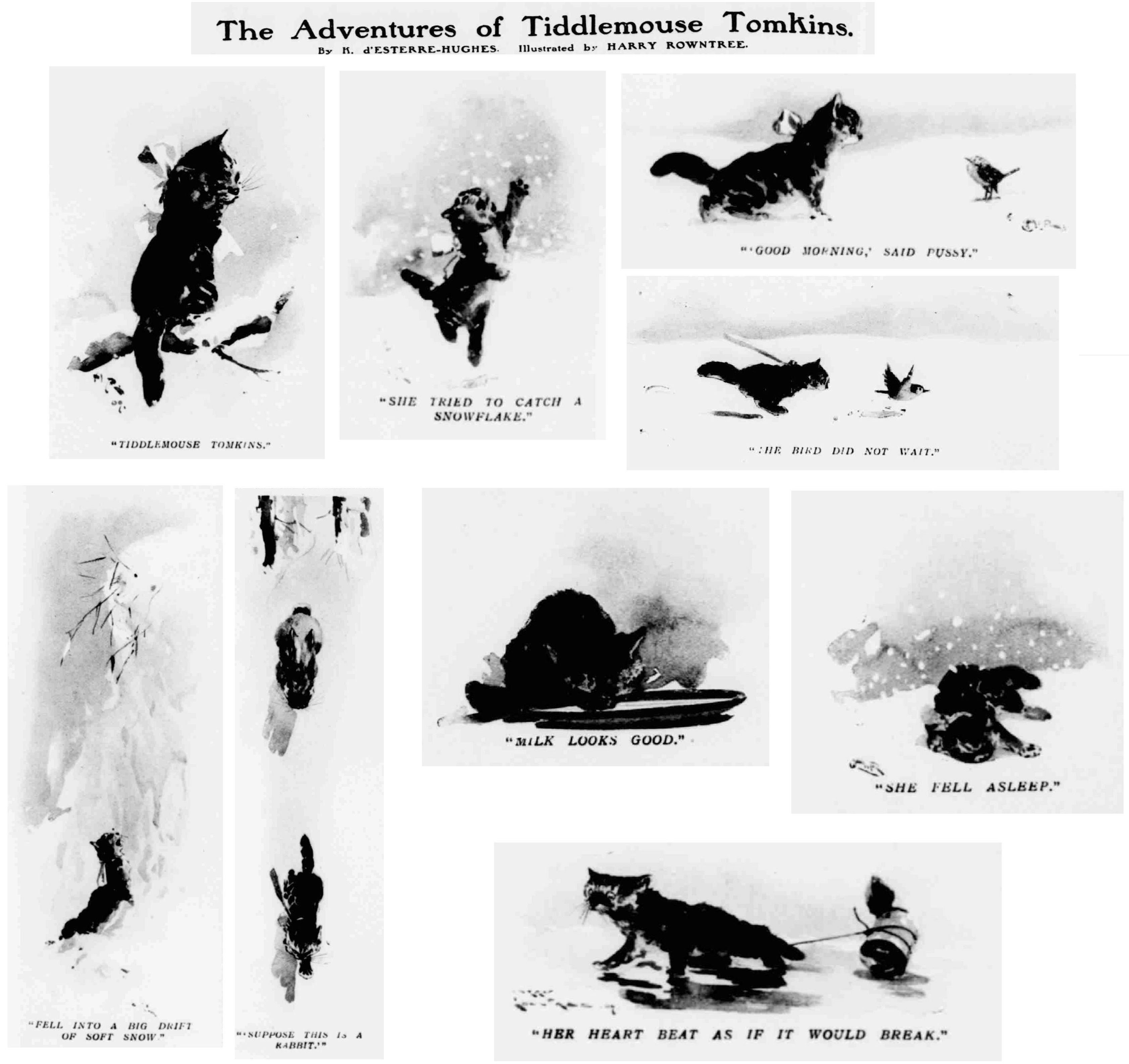

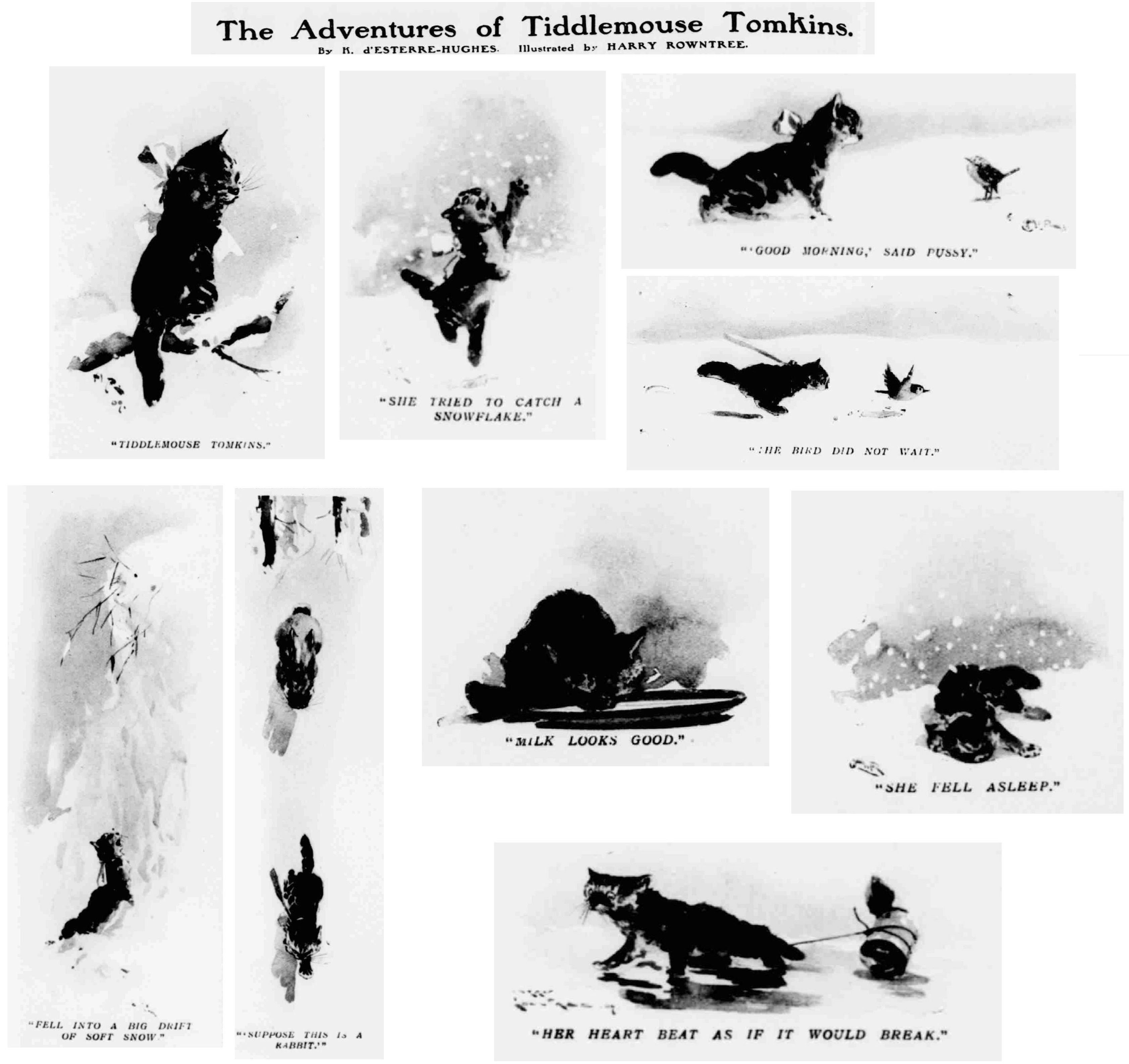

THE ADVENTURES OF TIDDLEMOUSE TOMKINS.

"I want to go out," said Tiddlemouse Tomkins, and she savagely scratched the glass of the long French window as if she would just loved to break it in pieces.

"Be quiet, Tiddledey," murmured Mother-Puss from her cosy corner by the fire. "You are the most troublesome child I've ever met in all my life. One moment you want to go out and the next you want to stay in. No one knows what you do want, and I'm sure you don't even know yourself. Besides," she added, sagely, glancing at the window as she spoke, "it's snowing."

"Snowing! What's that?" said Tiddlemouse; then she gave a frantic shriek and brought poor Mother-Puss with a rush to her daughter's side. "Look, look, Mumsie dear! Do look! Look at those dear, darling little white things. Oh, I do want to go and pay with them."

"Nonsense, child; how you frightened me That's snow; that's all it is." Mother-Puss indignantly walked away to a nice, comfortable looking cushion that was most invitingly placed in a dark corner of the sofa.

Now, the room was large, the sofa a long way from the window and Mother-Puss very sleepy, so it is no wonder that she did not hear Charlie Tomkins come into the dining-room and begin to talk to Tiddlemouse. Even if she had seen him she would not have worried, for never would she have imagined that he would let her only child get into mischief. Tiddlemouse saw that if her mother were not already asleep she soon would be, so she then and there made up her mind to have a real good time.

"Good morning, Charlic," she began, rubbing up against his legs in a friendly fashion.

"Ah, so it's Tiddlemouse! How are you to-day, Miss Tiddlemouse? I did not see you et breakfast-time - what was the matter, eh?"

Tiddlemouse knew just what Charlie was saying, though she could not answer in English, for her native language, and the only one she knew well enough to speak, was "Cat." But she did her best to make him understand by jumping up on to his knees and playing with his watch-chain, while she whispered, quite low, so that Mother-Puss could not possibly hear, that she had been locked up in the cellar all the morning because she had taken the cream, and that she had only managed to escape when cook had opened the door suddenly and forgotten to shut it at once.

"Oh, Tiddledey, Tiddledey," went on Charlie, just as if he had understood what she had been telling him. "So you were punished this morning. . . . Oh, Tiddledey, you were a naughty pussy cat! Are you sorry now? Yes, yes, you are, are you? Well, then, we'll say no more about it until next time; but there will never be a next time, will there, Tiddledey? You'll be a real good pussy cat after this, won't you?"

"Ah-um-ow," said Tiddlemouse, jumping down from Charlie's knees. She did not quite like all this talk about being too good, and thought that she had said "yes" often enough to satisfy even Charlie, for all the time he had been talking she had kept saying, "Yes, yes, yes, yes, y-e-s!"

"Meow-ow-ow," she went on, each "ow" being just a little louder than the last; yet not very, very loud, for she always remembered that Mother-Puss was in the room and might wake at any moment.

"You want the window open, do you? That is what you are talking so much about," said Charlie, good-naturedly, rising and following her to the window. "But it's snowing, pussy cat, and you don't want to wet your dear little tootsies, do you? Oh! you do?" as Tiddlemouse gave an emphatic "yes." "Well then, young lady, you can if you like. I want to read, and if you are going to sing, perhaps it would be better if you did go out for a bit." He opened the window, and out went Tiddledey.

The door was shut. For the first time in all her life she was outside the house alone. She turned, half intending to ask to be allowed in again, for it was cold after the warm dining-room. But there, as plain as life, and looking cross, Tiddledey thought, was Cook talking to Chariie. If he did open the window and she went in, Cook would surely catch her and shut her up in that horrid cellar again. So thought Miss Tiddlemouse, and she took a step away from the window towards the edge of the porch. I don't know. It's not so very bad," she murmured, looking back to see if Charlie would by any chance open the door a small bit so that she could creep in when Cook was not noticing. No, he was not even looking at the window now.

"I'll just play a little and then go back when she's gone," resolved Tiddledey, and she tried to catch a snowflake. But as soon as she touched one ever so gently it seemed to go quite flat. "Oh, you stupid things!" after several tries. "What do they call you, I wonder? 'Its very cold out here after all," she went on, "and there's not a bit of use trying to play with those white things; they are too soft. I'll just walk as far as that big tree and then come back."

Tiddlemouse knew what a tree was, as whenever Mother-Puss took her for a little walk she pointed out trees and shrubs and birds, and told her that trees were good to climb, birds to eat and shrubs to hide under. She did know something about the outside world, but not very much, for in the country where Tiddledey's home was there had been a very cold winter, and neither Mother-Puss nor Tiddledey had been able to go more than a few yards from the house for fear of being caught in a snow-storm.

The tree was not far. When she got to it and was about to return home something round and furry like herself darted past the tree and down the walk. Away after this funny thing went Tiddledey, never stopping to think about going back. She ran and ran after this brown ball and was nearly out of breath, when suddenly it stopped, and turning to her said sweetly, "You are a nice little cat, and you are a good runner, too."

"Thank you," said Tiddlemouse, smiling. "You ran faster, though, for I could not catch vou."

This pleased the other cat, who became even more gracious. "What's your name? Mine's Browny, and I live at No. 4, Adam Street."

"My real name is Tiddlemouse, but I'm called Tiddledey for short, and I live where you met me."

"Oh, yes; in one of the Smith Street houses, I expect you mean, You are rather young to be out alone. Have you a mother?"

"Yes," said Tiddledey; "but I came out by myself to see what was going on. Mother always wants to sleep."

"You had better be careful then," remarked Browny, sitting down on the trunk of an old tree and smoothing out her whiskers. She was a fine, fat cat about three months older than Tiddledey.

""Why, pray?" came indignantly from Tiddlemouse. "Don't you think I'm old enough to take care of myself?"

"That's as may be," said Browny; "but I shouldn't think so. The rabbits in the woods might get you - they'd eat you fast enough. Hey-ho! but I must be going. It's my lunch-time. Ta-ta!" And without waiting for Tiddledey to answer she was off down a side path.

Tiddledey started after her and then suddenly thought, "But I don't live down there; I must go back." She turned and went, as she thought, towards home. Instead, however, she went in the opposite direction, and every step she took led her farther and farther from Mother-Puss. She was not in any special hurry to get home, so she played with twigs and chased one or two little robin red-breasts and had a fine time for about an hour. Then she began to feel hungry and wonder how much longer it would be before she could reach the dining-room. She sat down to rest for a minute, and a beautiful red bird came and sat down on the bank opposite.

"Good morning," said Pussy, quite friendly, and ready for a talk with anyone; "perhaps you could tell me where - " But the bird did not wait. He had heard the cat language before, so he quickly fluttered away, Tiddledey ran after him calling, "Please, please, do tell me where Smith is – that is, I think she called it Smith Street. Please – " But the faster she ran the more anxious the bird seemed to get away, and after flying for a little while in front of her he suddenly rose straight up into the sky, and Tiddledey could not imagine where he had gone.

"Oh, dear, what shall I do? I don't see a house anywhere - nothing but horrid trees. I am so hungry, too!"

Poor little Tiddledey shed a few salt tears, for her legs were tired with running about over the hard snow. There was snow everywhere, but in most places it was frozen hard, as very little fresh snow had fallen that day. When running about Tiddledey had felt warm, but now she began to feel tired and thought the snow cold and nasty. She was walking slowly, without looking or thinking where she was going, and all of a sudden fell into a big drift of soft snow. She screamed and struggled, but there was no one near to hear her, and it was only after a long time that she managed to pull herself out on to the firmer snow. A poor, bedraggled little puss she was then. All her nice shiny coat that Mother-Puss was so fond of washing was wet and dirty, and a piece of tin had left a long scratch on her little grey nose, which did not improve her looks.

"If only that pretty bird had waited one minute, or if Browny had not gone away in such a hurry, or if that horrid cook had not been talking to Charlie, or -" She could think of nothing more to say, and so sat still, crying softly to herself. Suddenly there was a crunching sort of noise as if someone were walking quickly over the snow. Tiddledey stopped crying to listen. She started up as if to run and meet whoever was coming, then remembering what Browny had said about rabbits, ran quickly behind a tree.

"Suppose this is a rabbit," she thought. "I don't know what a rabbit looks like, but it must be something dreadful if it eats little cats like me. Oh, suppose it gets me - whatever shall I do!" She shivered and shook, and felt that she was the most miserable cat that had ever lived; and then all at once she cried out with glad joy, for along the path came someone who looked like Charlie, and so could not possibly be a rabbit.

It was not Charlie, though it was a boy of about his age, who stopped and looked at her.

"Me-e-ow."

He was a kind-hearted boy, and could not resist the piteous "me-e-ow." He picked up Tiddlemouse and smoothed her wet fur.

"You poor mite," he began, "it's much too cold for you out here. You look miserable and hungry."

He talked in this soothing way, and soon Tiddledey cuddled down in his arms and began to feel more cheerful. She even ventured to purr a little now and then. The boy seemed glad to hear her answer, and kept talking to her all the time he was walking along. Presently they left the wood and came to a street, and a few minutes later Tiddledey was in a warm shop drinking out of a tin plate the most delicious miik she had ever tasted. As she finished the last drop she looked up to thank her new friend, and heard him say: "Well, then, I'll leave her i with you. I expect she wants a home, and when she grows up she can catch those mice you are always complaining about."

"Yes," said a woman standing near, who had given Tiddledey the milk, "we do want a cat, so leave her, Jo."

Without another word the boy, whose name was evidently Jo, walked out of the shop. Tiddledey rushed after him before the woman could catch her, and was in time to see Jo jump on a tramcar and, so it seemed to Tiddledey, fly round the corner.

"Jo, Jo, stop! " called Tiddledey, running after the tram. "Why does everybody run away from me?" she added, when she could no longer see the tram.

"At any rate, this is better than the place where the rabbits might be," thought Tiddledey, sitting down on a doorstep; "but even now, I don't see how I'm to get home." While she was thinking what she should do next, she fell asleep, for she was only a young cat and very tired with her long walk.

"Here's a stray cat; let's have a lark!" were the words she heard as she was roughly awakened. Someone was holding her by her neck in a most uncomfortable way. She kicked and kicked, but was helpless. She could see that there were two boys beside her, and one of them was tying a piece of string to something that was bright and shiny.

"Got her?" said one. "The tin's ready; hold her tight. Now then, let her go!"

Tiddlemouse, terribly frightened, found herself on her feet again and at once stated to run. Oh, the humiliation of it! Fastened to her dainty little tail was something that banged against her legs and cut them. She stopped to try and take it off, but a big stone hit her in the middle of the back, and another one at the same moment struck the tin with a fearful noise. Then she ran. The boys, shouting and throwing stones, were after her. Some of the stones did hit her, but more did the ugly tin thing that she could not shake off. There was nothing for it but to run, and this poor Tiddledey did as she never ran before. It was a dreadful time. Her heart beat as if it would break; her feet were sore; her eyes started from her head in terror. If she slowed up for even a tiny second a piece of brick or stone would hurry her on again.

Now she was in a long, quiet street with the boys shouting and yelling close behind. She came to a corner, and turned it without thinking, hoping, perhaps, that an open door would offer her a refuge. But this, too, was a quiet street, and at the only open door a Scotch terrier was taking his afternoon nap. The noise of the tin beating on the sidewalk, together with the shouts of the boys, woke him. He jumped up barking an alarm. One glance; he saw the cat, the tin, and the boys. That was enough; he joined the race. With the tin, the boys, and the dog close behind her Tiddledey dashed round another corner, and found herself in a street of shops with many people walking all about. In and out between them she went, too tired to think of keeping still and hiding from her tormentors. Suddenly she was pounced upon by what seemed to be a giant, but was really only a big man's hand, and lifted high above the dog, who had just caught up to her. The terrier received a kick for his trouble, and went howling back to the corner where the small urchins had stopped, for none of them was inclined to chase a cat down a crowded street.

"What cowards some boys are!" said the big man to a friend, as he cut the string to which the tin still hung.

"Yes,"" agreed the other. "They deserve a good whipping. What are you going to do with it? It's only a young kitten, and quite exhausted."

"Poor thing, it looks nearly frightened to death. Il take it in here and get it some milk and then let it go. It'll find its own way home again I" expect."

"Meow, meow, me-e-ow-ow, don't, don't leave me," begged Tiddledey, piteously. But the men did not understand.

"Yes, it has had a hard day's work from the look of its fur," presently said one of them as the big man opened the door of a dairy, "and that cry means milk, milk, milk, I expect!"

"Meow-ow-ow; no, no, no," from Tiddledey, us a girl came behind a counter and placed a big saucer of milk in front of her. "I didn't mean miik; but it looks good!" Being very thirsty she did not stop to argue the question then. When she had had sufficient she looked up, but both the men had disappeared and only the girl was in the shop.

"Thank you," said Tiddledey, who had been taught to be polite. "You are a ducky little kitten with your black coat and white paws," said the girl, taking Tiddledey into her arms. "At least," she went on, "I'm sure you are when you are clean; now, this minute, you are too dirty to be pretty."

Tiddlemouse Tomkins forgot that all her journeyings had made her very untidy, and became quite cross when the girl told her that she was not a nice, clean cat, for Mother- Puss had always been most particular about washing Tiddledey's coat and showing her how to look like a little lady cat. Almost without thinking she put out her claws and scratched the girl's s hand.

"Oh, you horrid, nasty little wretch," exclaimed the girl, dropping Tiddledey quickly to the floor. "I don't wonder a bit e that boys tie tins to your tail - You deserve it - Out you go now!" As she spoke, she opened wide the door and pushed Tiddledey out of the shop with the toe of her boot.

"Ah me, I'm having a pleasant day," muttered Tiddledey, as she scampered into the next doorway. "What shall Ido next? Where can I go, I wonder, where the people will be nice to me? If that girl hadn't said that I was dirty - I'm not dirty, I know I'm not - if she hadn't said I was I wouldn't have hurt her. That milk was good - I wish I had some more!" and she began to lick her whiskers thoughtfully.

Just then, who should come along but Charlie.

"Mew, meow, meow-ow-ow, me-e-ow!" called Tiddledey, running up and rubbing herself against him in the wildest joy. "Dear old Charlie, is it really you? I've been lost; do take me home!"

"Why, goodness gracious, if it's not Tiddledey! Whoever would have expected to see you down here," said Charlie, picking up the little dirty ball of sticky, blacky black fur that called itself Tiddiemouse Tomkins, "You look as if you had been having a fight and got the worst of it, Miss Tiddledey! Have vou been out ever since morning? Naughty little puss; untidy little Tiddledey, I believe you've been shopping!" And Charlie began to laugh at the idea. Tiddledey noticed that he, too, called her dirty, but she did not say anything, nor even try to scratch him, for she just had had a lesson that she would not forget for quite half an hour. Besides, she was thinking that if Charlie called her dirty, Mother-Puss would be sure to have something to say about her appearance as well as about her having run away, and she did not know what she should say when Mother-Puss began asking questions! They would be much worse than Charlie's, for she would have to answer whether she wanted to or not, and with Charlie she need not say anything unless she felt like it.

"No, no, Charlie," she did find courage to say as he carried her quickly homewards, "I'm not naughty now; it's everybody else that is naughty - they've all been so unkind to me - "

"Poor little Tiddlemouse," interrupted Charlie, "and you've had nothing to eat all day. You must be hungry! Well, we'll soon be home now."

Tiddledey did not say anything when he mentioned that she had had nothing to eat all day, for she remembered the two kind people who had given her milk, and she remembered, too, how unkindly she had treated them, and she began to feel ashamed of the way she had been complaining about other people when, perhaps, she ought to have blamed herself. This did not worry her for long, and she had just begun to tell Charlie about the bad boys and the tin when he went up some steps and opened a door that led into a hall she knew so well; then another door, and there - there was Mother-Puss sitting by the window looking so sad and forlorn that the big tears came into Tiddledey's eyes and a funny lump grew all at once in her throat, for she knew that she was the cause of Mother-Puss's strange looks. With a short, sharp cry, Tiddledey jumped down and ran to her mother. who welcomed her as never a little kitten had been welcomed before.

"My darling, darling child! Where have you been? I have hunted teverywhere for you, and thought that you must be dead."

Such a lot of kissing and purring went on that Charlie had to go and get ready for dinner long before Mother-Puss could control her joy and listen in silence to the story of Tiddlemouse's many adventures in the big, strange outside world. So glad was she to have her only daughter once more that she never remembered to scold Miss Tiddledey for going out without permission or even for getting the beautiful black coat so nasty and dirty.